1 Immunology and General Pathology Laboratory, Department of Biotechnology and Life Sciences, University of Insubria, 21100 Varese, Italy

The dynamic and multifaceted role of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) within the tumor microenvironment (TME) has garnered substantial attention in recent years, owing to their profound influence on tumor progression, immune modulation, and therapeutic response [1]. In their review, “The Role of Innate Priming in Modifying Tumor-associated Macrophage Phenotype”, Topham et al. [2] delve into the complexities of TAM plasticity and the mechanisms driving their phenotypic polarization. TAMs, which originate from recruited monocytes or resident macrophages, are inherently shaped by the immunological, metabolic, and epigenetic landscapes of the TME. Depending on local cues, TAMs can adopt either pro-tumorigenic or anti-tumorigenic phenotypes, thus playing a pivotal role in determining the trajectory of cancer development and treatment outcomes [2, 3, 4].

One of the more intriguing aspects of TAM biology explored in this review is the concept of innate priming, a process in which macrophages undergo metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming upon initial exposure to primary stimulants. This priming endows them with altered responses to subsequent stimuli, often resulting in either amplified (innate training) or attenuated (innate tolerance) inflammatory responses. By influencing TAM phenotypes before their integration into the TME, innate priming offers a novel avenue to manipulate their functional outcomes, potentially enhancing their tumoricidal capacity or mitigating their tumor-promoting effects [2].

While the reviewed article provides a robust overview of innate priming mechanisms, including epigenetic modulation, metabolic shifts, and their relevance to TAM phenotypes, significant gaps remain in the translation of these insights into clinical practice. For example, although exogenous compounds like the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine and

This commentary builds on the original review mentioned, aiming to contextualize their findings within the broader landscape of cancer immunotherapy and precision medicine. By critically evaluating the methodological approaches and theoretical assumptions underpinning innate priming research, this paper seeks to illuminate key opportunities and challenges in leveraging TAM plasticity for therapeutic benefit [2].

Topham et al. [2] provide a compelling foundation for understanding how innate priming, that is, the functional enhancement of innate immune cells via prior stimulation, can reshape TAM activity through both metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming. Their review highlights exogenous agents such as BCG and

However, innate priming encompasses more than responses to microbial products. Endogenous stimuli, particularly oxLDL, represent an underexplored yet potentially significant axis in TAM programming. Depending on the context, oxLDL can promote pro-tumorigenic macrophage phenotypes via the upregulation of interleukin 10 (IL-10) and tumor growth factor-beta (TGF-

Moreover, systemic metabolic conditions, such as obesity and metabolic syndrome, further complicate this landscape. Chronic low-grade inflammation associated with obesity leads to the accumulation of metabolites, including leptin, free fatty acids, and butyrate, that can alter macrophage polarization and immune metabolism [9, 10, 11]. Leptin, for example, has been shown to enhance pro-inflammatory signaling via the JAK-STAT pathway, while butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid, can exert both anti-inflammatory and immunostimulatory effects depending on concentration and context. Yet, the specific effects of these metabolites on TAM priming in diverse tumor types remain poorly understood.

Collectively, these findings call for a broader conceptualization of innate priming, one that includes both exogenous immunomodulators and endogenous metabolic cues. Future research should aim to dissect the molecular circuits by which these stimuli modulate TAM function across cancer contexts. A more nuanced understanding of how metabolic health and environmental exposures shape the priming landscape could yield novel therapeutic targets for enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapies like BCG.

Metabolites associated with obesity, including leptin and butyrate, are known to influence macrophage polarization; however, their specific role in priming tumor-associated macrophages across different cancer types remains unclear [9, 10, 11].

The BCG vaccine, initially developed for tuberculosis, has long been recognized for its immunomodulatory properties, particularly in cancer therapy. Its ability to induce “trained immunity” through epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming of innate immune cells, such as monocytes and macrophages, has positioned it as the standard treatment for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) [12, 13, 14].

However, the effectiveness of BCG therapy is deeply intertwined with the complexity of the TME, where a dynamic interplay between immune activation and suppression dictates therapeutic outcomes. While BCG initiates a robust immune response, the contradictory roles of various immune cell populations within the TME can either enhance or limit its efficacy, creating a highly unpredictable treatment landscape [15, 16].

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), for example, are known for their potent immunosuppressive functions, inhibiting T cell responses and dampening inflammation. While BCG has been shown to counteract some of the suppressive effects of MDSCs by inducing trained immunity, there are contradictory findings suggesting that, under certain conditions, BCG may inadvertently promote MDSC expansion, thereby weakening its anti-tumor potential [17, 18].

Recent research in re-engineered BCG strains, such as those overexpressing cyclic di-AMP, has demonstrated a more pronounced ability to override MDSC-mediated immunosuppression by promoting a stronger inflammatory response, suggesting that BCG’s impact on MDSCs may be highly context-dependent [19].

Similarly, TAMs further complicate the response to BCG therapy. Macrophages are highly plastic and can shift between pro-inflammatory and immunosuppressive states depending on the cytokine milieu within the TME [3, 4, 20].

BCG has been shown to promote the polarization of macrophages toward a more inflammatory, tumoricidal phenotype, yet this effect is not always sustained. In some cases, persistent immunosuppressive macrophages in the TME may counteract BCG’s beneficial effects, creating an environment where trained immunity fails to establish a durable anti-tumor response [21].

A study on modified BCG strains found that an engineered BCG strain expressing high levels of cyclic di-AMP significantly shifted macrophage populations toward a more inflammatory phenotype, suggesting that targeted modifications to BCG could enhance its consistency in overcoming the immunosuppressive tendencies of the TME [19].

The contradictory effects of BCG are further evident in its interactions with regulatory T cells (Tregs). Other studies have suggested that BCG therapy leads to a reduction in Treg-mediated suppression, while others highlight cases where Treg expansion correlates with poor treatment outcomes [22, 23].

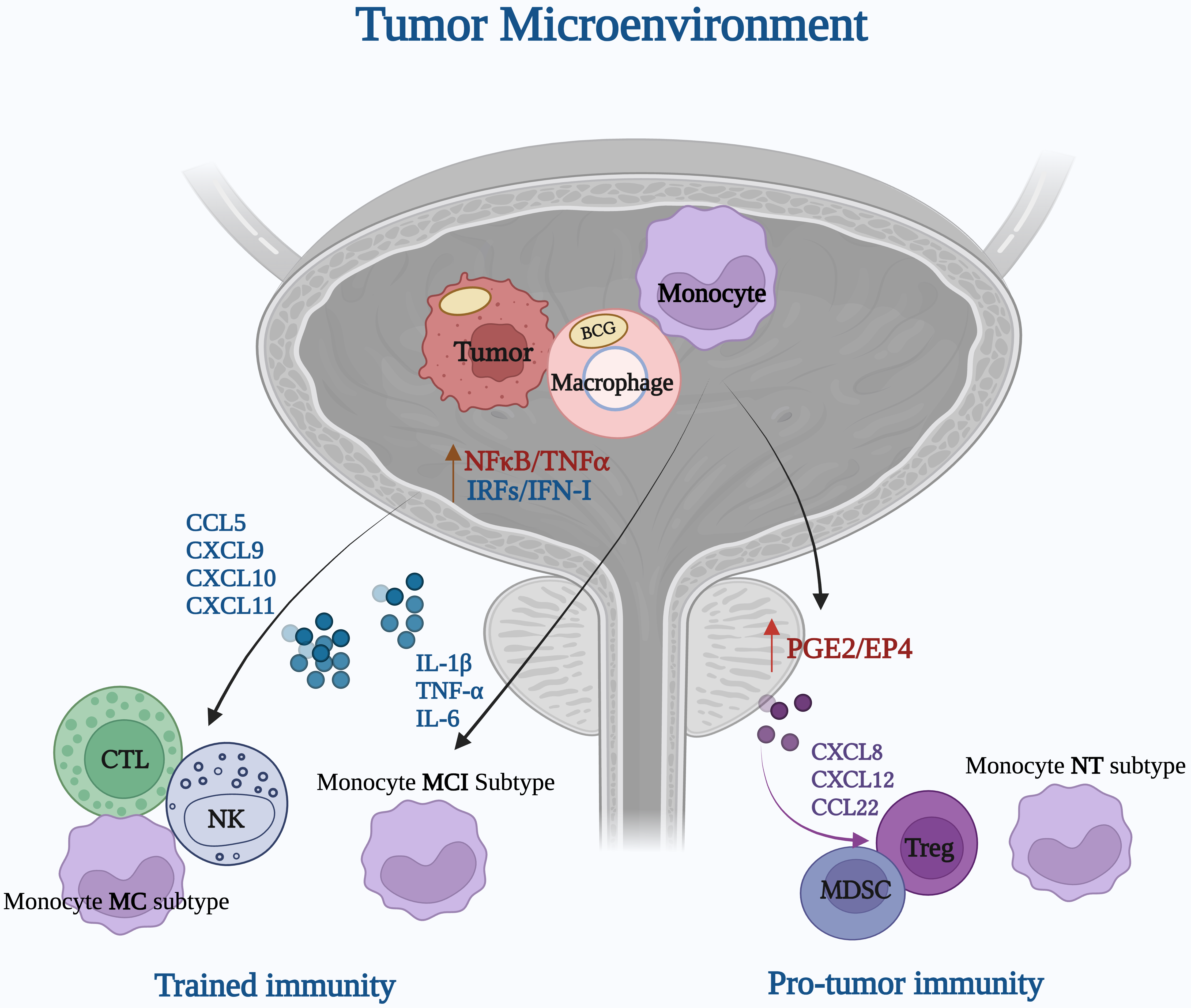

Moreover, recent findings from Zhang B et al. [24] provide critical insights into how BCG-induced trained immunity is shaped by the heterogeneity of monocyte subpopulations, adding another layer of complexity to its therapeutic effects in bladder cancer. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) revealed that monocytes do not uniformly respond to trained immunity stimuli but instead differentiate into distinct subpopulations, each with varying inflammatory and immunosuppressive potential. Specifically, the study identified three major monocyte-derived subsets: MCI (monocytes with cytokine-induced inflammation), MC (monocytes with chemokine-driven signaling), and NT (non-trained, immunosuppressive-like cells). The MCI subset, characterized by high expression of IL-1

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)-driven activation of the bladder cancer TME: immune cell dynamics in trained immunity and pro-tumor immunity (Figure created with BioRender.com). The mechanisms are explained in more detail in BCG Vaccine and the Complexity of the Tumor Microenvironment section. CCL, Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand; CXCL, Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand; IL-1β, Interleukin-1 beta; IL-6, Interleukin-6.

Definitely, the effectiveness of BCG therapy is shaped by the complex and often contradictory interactions within the TME [14, 16].

While trained immunity offers a compelling mechanism for sustained anti-tumor responses, the presence of immunosuppressive elements such as MDSCs, TAMs, and Tregs can create significant barriers to success.

A key strength of the review lies in its discussion of innate priming’s potential for clinical applications, such as enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapies [2].

For instance, the ability of innate priming to potentiate immune checkpoint inhibitors, particularly PD-1/PD-L1 blockers, opens exciting avenues for therapeutic intervention. Studies have shown that primed TAMs can exhibit enhanced anti-tumor immunity, potentially improving outcomes for patients with cancers that are resistant to standard therapies. However, translating these findings into clinical practice is fraught with challenges [25, 26].

First, the heterogeneity of the TME poses a significant barrier [15].

TAM phenotypes are highly plastic, and their responses to priming stimuli are context-dependent [20].

For example, while BCG-induced priming has shown promise in bladder cancer, its efficacy in solid tumors with a highly immunosuppressive TME, such as pancreatic or ovarian cancer, remains unclear [13, 15].

Second, the long-term consequences of priming on systemic inflammation need to be carefully evaluated. Heightened immune responses may inadvertently exacerbate inflammatory pathologies or autoimmune conditions, as highlighted by the duality of innate training versus tolerance [27].

Moreover, existing preclinical models are insufficient to capture the complexities of innate priming in vivo. Most studies rely on 2D cultures or murine models, which fail to replicate the intricate interactions within human TMEs [28]. Advanced models, such as organoids or humanized mouse models, could provide more physiologically relevant insights. These models would also allow for the evaluation of combination therapies that integrate innate priming agents with conventional treatments like chemotherapy or radiation [28].

Several early-phase clinical trials are exploring innate-priming strategies to reprogram TAMs. TLR agonists such as imiquimod and resiquimod have shown activity in skin and lymphoma settings (e.g., NCT01421017, NCT01676831), while IMO‑2125 (a TLR9 agonist) is advancing in PD‑1 refractory melanoma with encouraging survival data. CD40 agonistic antibodies (e.g., CP‑870,893; NCT02225002) seek to induce M1 polarization, and CSF‑1R inhibitors like emactuzumab have demonstrated significant TAM depletion and tumor responses in tenosynovial giant cell tumors. In parallel, approaches targeting monocyte recruitment, such as MLN1202 and PF‑04136309 (CCR2 axis), are in advanced solid tumor trials (e.g., NCT01015560, NCT02732938). Additionally, the novel CAR-macrophage therapy CT-0508 is entering phase I for HER2+ tumors (NCT04660929). These studies underscore the translational potential of innate priming in reshaping the tumor microenvironment.

One of the most intriguing aspects of innate priming is its potential to influence immune responses beyond the TME. The review by Topham et al. [2] briefly touches on systemic factors, but this area deserves more emphasis. For example, circulating monocytes primed by dietary metabolites or environmental stimuli may arrive at the tumor site with altered phenotypes, thereby shaping TAM functionality even before encountering the local TME. This raises important questions about the systemic regulation of innate immunity and its implications for cancer progression [8, 29].

Furthermore, innate priming could have implications for comorbidities commonly observed in cancer patients, such as chronic inflammation or cardiovascular disease. For instance, the interaction between primed macrophages and atherosclerotic plaques could exacerbate cardiovascular complications, highlighting the need for a holistic approach to evaluating the risks and benefits of innate priming therapies [30]. A hypothetical scenario could involve a patient with HER2+ breast cancer and pre-existing atherosclerosis, where systemic activation of macrophages through a priming agent not only enhances anti-tumor immunity but also accelerates vascular inflammation, increasing the risk of myocardial infarction. This underscores the importance of considering patient-specific inflammatory profiles when designing innate immune interventions.

To fully harness the potential of innate priming in cancer therapy, several critical gaps in knowledge must be addressed. First, identifying reliable biomarkers of primed TAMs is essential for patient stratification and monitoring therapeutic responses. These biomarkers could include epigenetic signatures, metabolic profiles, or surface markers unique to primed macrophages. Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and single-cell analysis offer promising avenues for identifying TAM subpopulations with greater precision and scalability. Second, a deeper understanding of the temporal dynamics of priming is needed. How long do primed phenotypes persist? Can priming effects be selectively reversed to mitigate adverse outcomes? Addressing these questions will require longitudinal studies and the development of advanced imaging techniques to track macrophage behavior in real-time. Additionally, ethical concerns must be considered in the development of macrophage reprogramming strategies, particularly those involving irreversible modifications or systemic immune alterations. Transparent guidelines and thorough preclinical evaluation will be crucial to ensure patient safety and public trust.

Finally, exploring the synergy between innate priming and emerging therapies, such as CAR-T cells or oncolytic viruses, could unlock new therapeutic possibilities. By reprogramming the immune landscape to favor anti-tumorigenic responses, innate priming could act as a powerful adjunct to these cutting-edge treatments.

The review by Topham et al. [2] provides an insightful foundation for understanding the role of innate priming in TAM plasticity and its implications for cancer therapy. Their discussion highlights the potential of innate priming to modulate the TME by shifting TAM phenotypes toward more tumoricidal states. However, as explored throughout this commentary, the impact of innate priming is highly context-dependent, influenced by the dynamic and often contradictory interactions within the TME. The interplay between trained immunity, immunosuppressive forces such as MDSCs and Tregs, and the metabolic and epigenetic conditioning of macrophages presents both opportunities and challenges for therapeutic applications.

One of the most promising aspects of innate priming is its potential to enhance current immunotherapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors and BCG-based treatments. Studies on modified BCG strains, such as those overexpressing cyclic di-AMP, illustrate how engineered priming strategies can enhance inflammatory responses while mitigating immunosuppressive resistance. Nevertheless, the heterogeneity of the TME remains a significant barrier, as TAM responses to priming stimuli vary across cancer types and patient populations.

Ultimately, while innate priming represents a powerful mechanism for reprogramming the immune landscape, translating these insights into effective clinical interventions requires a multidimensional approach. By integrating immunological, metabolic, and systemic perspectives, future research can refine innate priming strategies to maximize their therapeutic potential and improve patient outcomes. If fully understood and harnessed, innate priming mechanisms could reshape clinical practice. Targeted TAM priming agents may become adjuncts in checkpoint blockade protocols, particularly in tumors refractory to T-cell-based therapies. This could offer a viable strategy for patients who currently have limited responses to existing immunotherapies.

LM, SB, ADS conceptualized the study. SB, ADS wrote the original draft. SB, ADS, LM edited the manuscript. SB, ADS handled visualization. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We appreciate the insightful feedback from the peer reviewers, which greatly improved the quality of our work.

This research was funded by University of Insubria, MOR24FAR2024 to LM.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.