1 College of Veterinary Medicine, Shanxi Agricultural University, 030801 Jinzhong, Shanxi, China

Abstract

In mammals, skeletal muscle typically constitutes approximately 55% of body weight. The thermogenesis of skeletal muscle increases with increased cold stress, and skeletal muscle maintains the animal’s body temperature through the heat generated by shivering. However, less attention has been paid to investigating the impact of cold stress on the fiber type makeup of skeletal muscle, especially the gastrocnemius. Consequently, this research explored how cold stress regulates muscle development and fiber type composition.

A cold stress model was established by subjecting mice to a 4 °C environment for 4 hours daily. This model was combined with an in vitro siRNA-mediated knockdown model for joint validation. The impact of cold stress on skeletal muscle development and myofiber type transformation was assessed using experimental techniques, including immunofluorescence and western blotting.

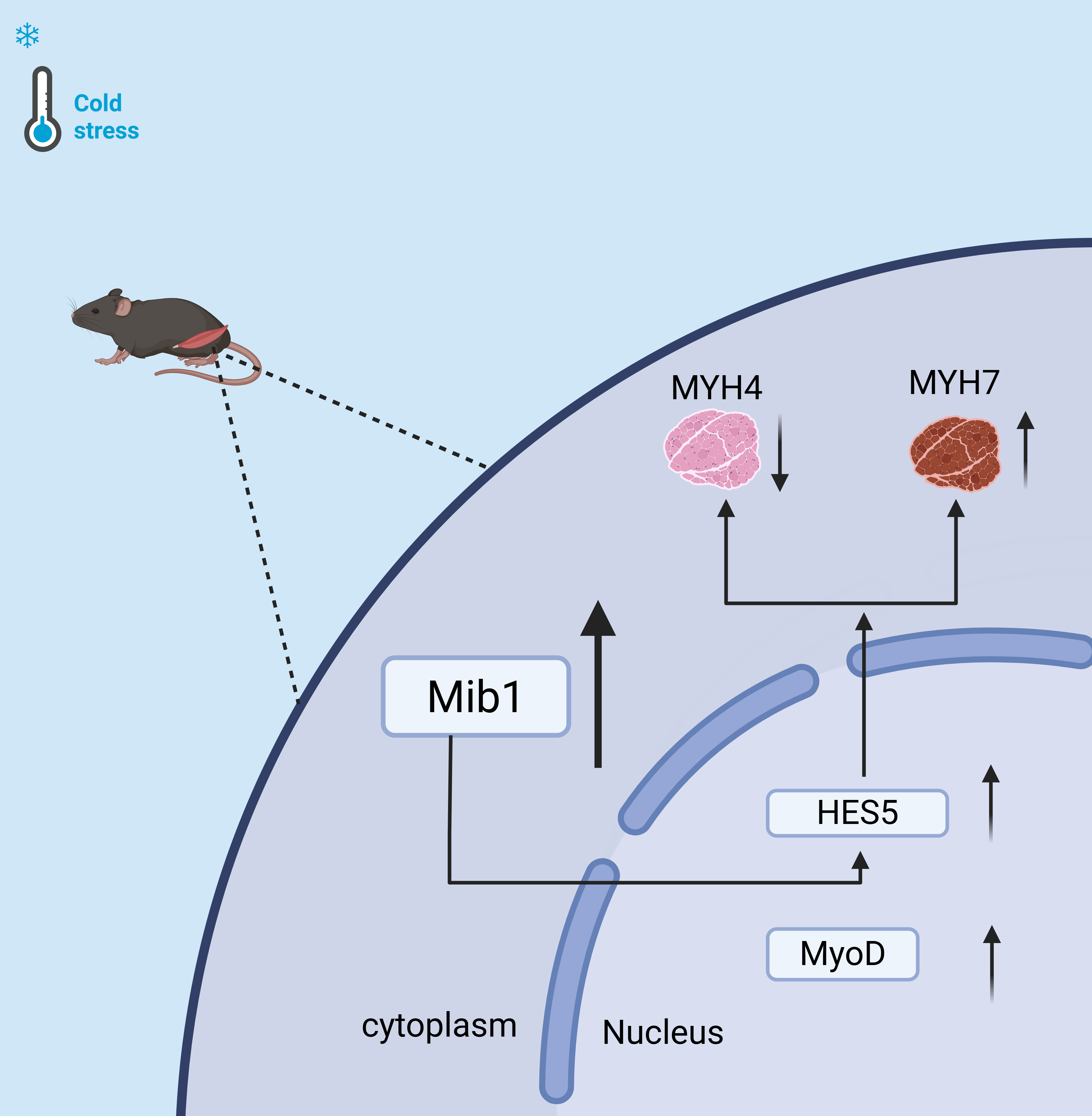

Following cold stress, the expression level of Myosin Heavy Chain 7 (MYH7) in the mouse gastrocnemius increased, while Myosin Heavy Chain 4 (MYH4) expression decreased. Concurrently, elevated expressions of Mindbomb-1 (Mib1) and the myogenic differentiation (MyoD) were observed. Subsequent knockdown of Mib1 in C2C12 cells resulted in increased MYH4 expression and decreased MYH7 expression.

Cold stress induces skeletal muscle fibers to shift from fast-twitch to slow-twitch through the Mib1/Notch signaling pathway.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- cold stress

- Mib1 gene

- Notch signaling pathway

- skeletal muscle

- muscle development

- muscle fiber types

Skeletal muscle is the largest and most important constitutive tissue in biological motor systems, playing a crucial role in body movement and homeostasis regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. There are large differences in metabolic characteristics and physicochemical properties among different types of muscle fibers [1]. Muscle fibers are mainly divided into two types. Type I muscle fibers, characterized by a reddish hue, are packed with mitochondria, making them ideal for sustained, endurance activities. In contrast, Type II fibers, which appear whiter, rely primarily on anaerobic glycolysis to generate energy, making them better suited for quick, intense bursts of activity [2]. Fiber type composition varies substantially across mammalian skeletal muscles, typically containing multiple types. A prime example is the Soleus muscle, characterized by a predominance of type I oxidative fibers, whereas the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle displays a high abundance of type II glycolytic fibers [3]. The proportion of muscle fiber types can be variable, and muscles can adapt to different pathophysiological changes by changing the proportion of their fiber types. Obesity tends to convert type I fibers into type Ⅱ fibers [4], and endurance exercise training increases the proportion of type I oxidative fibers [5]. Although muscle fiber type conversion is important, the molecular mechanism of the regulatory process of muscle fiber conversion remains poorly understood.

The Notch pathway plays an important role in vascular and muscular differentiation during embryogenesis [6]. The transcriptional suppression of the myogenic determinant (MyoD) by activated Notch signaling underlies its inhibition of C2C12 and 10T/2 myoblast differentiation [7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. Mindbomb-1 (Mib1) is a key E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in the regulation of Notch signaling [12, 13]. The Notch signaling pathway, a highly conserved mechanism crucial for myogenesis, facilitates intercellular communication through specific ligand-receptor interactions. Activation of Notch signaling exerts inhibitory effects on muscle satellite cell proliferation and can induce dedifferentiation of myocytes, thereby contributing to the maintenance of satellite cell quiescence [14, 15]. Mib1 can promote the endocytosis of Notch ligands [16]. A study has found that with increasing age, loss of Mib1 in myofibers leads to muscle atrophy, histological feature abnormality, and muscle function impairment [17]. Notch signaling activation is suppressed in mammalian cells following Mib1 repression [18]. However, there are relatively few studies on the relationship between Mib1/Notch and myofiber type transformation.

Chronic cold exposure oxygen positron emission tomography (PET) combined with indirect calorimetry shows that skeletal muscle accounts for 40%–70% of total oxygen consumption under mild cold stress (1.13–1.20 times the resting metabolic rate) [19, 20]. The effect of skeletal muscle on body thermogenesis will further increase with increased cold stress, but there is no precise method to directly quantify this effect. The increased energy expenditure caused by the compensable cold exposure is proportional to the body heat loss caused by the environment, which is mainly driven and completed by shivering heat production [21, 22]. Cold stress enhanced glycogen synthesis in the soleus, extensor digitorum longus, and supraspinatus muscles, but elevated glycogen content exclusively in the soleus muscle. Following cold stress, upregulation of Protein kinase B (AKT), Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3

Our research assessed consequences of cold stress on muscle development and the composition of fiber types. By examining an in vitro siRNA-mediated knockdown model and an in vivo cold exposure model in mice, this study was aimed to reveal the impacts of cold stress on skeletal muscle development and fiber type transformation, as well as the related molecular mechanisms. Our findings will provide a theoretical basis for developing therapeutic strategies targeting muscle atrophy and metabolic diseases.

This study used the male mice of C57BL/6J aged 8 weeks at the stage of body maturity with the weight of 22

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 1.25% tribromoethanol at a dose of 0.2 mL per 10 g of body weight. Anesthesia was considered successful when the mice became unresponsive to stimuli. Subsequently, the mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation.

The maximum muscle force of mice was measured for six times by a grip strength meter (SA415, SansBio, Jiangsu, China), and the mean maximum muscle strength was adopted for subsequent analysis. As previously described, the initial running speed was 12 meters per minute (m/min), lasting for 40 min, and then running speed was progressively raised at the increment rate of 1 m/10 min for subsequent 30 min. Finally, the speed was further raised at increment rate of 1 m/5 min until physical exhaustion. Physical exhaustion was operationally defined as the point at which the mice stopped running on the electric grid for 10 consecutive seconds, followed by the determination of one round of exercise [24].

Gastrocnemius samples were collected from mice and fixed in a specialized muscle-specific paraffin fixative for 24 hours. Subsequently, the fixed muscles were sectioned at a thickness of 7 µm using a microtome (CM1850, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Following deparaffinization and rehydration, sample sections were subjected to immunofluorescence staining and blocking with 5% goat serum. Primary antibodies applied to sample sections included mouse anti-MYH1 (67299-1-Ig, Proteintech, Wuhan, China, 1:400), rabbit anti-MYH4 (20140-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China, 1:400), rabbit anti-MYH7 (22280-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China, 1:400), and rabbit anti-Mib1 (11893-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China, 1:200). Sample sections were then incubated with species-appropriate secondary antibodies including goat anti-mouse IgG (Alexa Fluor conjugate, A32723, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA, 1:1000) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (Alexa Fluor conjugate, A-11012, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1:1000). Nuclei were re-stained with DAPI (C1002, 091223240402, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China, 1:1000). Immunofluorescence images were captured using an ECLIPSE Ts2R microscope (Nikon, Shanghai, China). The positive staining area was quantified using ImageJ software (V1.51, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Total RNA was extracted from cells and tissues using RNAiso Plus (9108, TAKARA, Kyoto, Japan) following the manufacturers’ instructions. cDNA was synthesized with the HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (R323-01, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). RT-PCR was performed with the MonAmp SYBR Green qPCR Mix (Monad, Suzhou, China) on QuantStudio™ 5 System (Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fisher Scientific), and gene expression was calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method. The primer list is as follows Table 1.

| Name | Primer sequence |

| Myh1-F | GCGAATCGAGGCTCAGAACAA |

| Myh1-R | GTAGTTCCGCCTTCGGTCTTG |

| Myh4-F | CCTGGAACAGACAGAGAGGAGCAGGAGAG |

| Myh4-R | GTGAGTTCCTTCACTCTGCGCTCGTGC |

| Myh7-F | ACAAGCTGCAGCTGAAGGTG |

| Myh7-R | TCATTCAGGCCCTTGGCAC |

| Mib1-F | AGTTGGCCGAGTACAACAGAT |

| Mib1-R | TGTTCCACAGACTTCCACCTT |

| Mrf4-F | AGAGGGCTCTCCTTTGTATCC |

| Mrf4-R | CTGCTTTCCGACGATCTGTGG |

| Myf5-F | AAGGCTCCTGTATCCCCTCAC |

| Myf5-R | TGACCTTCTTCAGGCGTCTAC |

| MyoD-F | CCACTCCGGGACATAGACTTG |

| MyoD-R | AAAAGCGCAGGTCTGGTGAG |

| MyoG-F | GAGACATCCCCCTATTTCTACCA |

| MyoG-R | GCTCAGTCCGCTCATAGCC |

| Jag2-F | CAATGACACCACTCCAGATGAG |

| Jag2-R | GGCCAAAGAAGTCGTTGCG |

| Heyl-F | CAGCCCTTCGCAGATGCAA |

| Heyl-R | CCAATCGTCGCAATTCAGAAAG |

| Hes5-F | AGTCCCAAGGAGAAAAACCGA |

| Hes5-R | GCTGTGTTTCAGGTAGCTGAC |

| 36B4-F | ACTGAGATTCGGGATATGCTGT |

| 36B4-R | CCCACCTTGTCTCCAGTCTTTA |

Myh1, Myosin Heavy Chain 1; Myh4, Myosin Heavy Chain 4; Myh7, Myosin Heavy Chain 7; Mib1, Mindbomb-1; Mrf4, Muscle Specific Regulatory Factor 4; Myf5, Myogenci Factor 5; MyoD, Myogenic Differentiation; MyoG, Myogenin; Jag2, Jagged Canonical Notch Ligand 2; Heyl, Hes Related Family BHLH Transcription Factor With TRPW Motf Like; Hes5, Hes Family BHLH Transcription 5; 36B4, 36B4 acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 gene.

The protein fractions were extracted from C2C12 cells and muscle tissues with RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Servicebio, Wuhan, China). Protein samples (25 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris buffer saline with Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h at 37 ℃, and then incubated with the relevant primary antibody overnight at 4 ℃. After washing five times with TBST, the membranes were incubated with either anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked secondary antibody (1:25,000 dilution, Proteintech, SA00001-1, SA00001-2). The protein bands were visualized using a chemiluminescence reagent (Abbkine, Wuhan, China). Band quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ software. The primary antibodies included MYH1 (67299-1-AP, Proteintech, 1:3000), MYH4 (20140-1-AP, Proteintech, 1:2000), MYH7 (22280-1-AP, Proteintech, 1:2000), MyoD (TA7733, Abmart, Shanghai, China, 1:500), MyoG (sc-12732, SantaCruz, Dallas, TX, USA, 1:500), MyoD (AB203383, abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1:500), MyoG (AB1835, abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 1:1000), MIB1 (11893-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China, 1:1000), HES5 (A16237, Abclonal, Wuhan, China, 1:500), and GAPDH (10494-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China, 1:25,000).

The C2C12 (Chinese Academy of Sciences) was cultured in high glucose DMEM (Gibco, New York, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) at 37 ℃ in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. When cells reached 90% confluency, culture medium was replaced with DMEM containing 2% horse serum to induce the differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes for 5–6 days. The siRNA sequence of Mib1 was purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China) and transfected into C2C12 myotubes using lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions. The cell lines used in this study were authenticated by STR profiling and tested for mycoplasma contamination.

ELISA was conducted following the manufacturers’ instructions using the kits including Mouse

All data were presented as mean

For determine the effect of cold stress on the body function in mice, we raised male C57BL/6J mice in a 4 ℃ environment for one month, and monitored mouse body temperature before and after cold stress. We found that cold stress reduced body temperature (Fig. 1A), but increased food intake per mouse (Fig. 1B,C). To assess cold stress-induced alterations in muscle contraction, murine exercise capacity was analyzed. Endurance exercise experiment showed that after 30-day low-temperature exposure, mice’s running time was extended, compared with the control (Fig. 1D). In addition, we found that cold stress increased muscle grip strength in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1E). Our data point to a preferential improvement in endurance performance over explosive performance following cold stress. Simultaneously, we detected the content of lactate in mouse plasma and found that the content of lactic acid in mice increased after cold stress (Fig. 1F). Additionally, our findings revealed that cold stress treatment increased the ratio of tibialis anterior (TA)/body weight (Fig. 1G). Interestingly, we also found that cold stress increased the proportion of small muscle fiber (800–1000 µm2 and 1200–1400 µm2), but decreased the proportion of large muscle fiber (

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Effect of cold stress on body function in mice. Male C57BL/6J mouse were raised in a 4 ℃ environment for one month. (A) Body temperature before and after cold stress. (B) Food intake. (C) Cumulative food intake. (D) Endurance exercise experiment. Time and distance to exhaustion status were measured. (E) Muscle grip strength. (F) The content of Lactic acid in plasma. (G) Ratio of muscle masses/body weights. (H) HE staining of gastrocnemius muscle and frequency line graph of fiber cross-section. Scale bar = 100 µm. Data were expressed as mean

Cold stress modulated myosin heavy chain isoform expression in mixed gastrocnemius, upregulating the slow Myh7 and downregulating the fast Myh4 (Fig. 2A). Myh1 is associated with skeletal muscle contraction and is involved in the transformation between glycolytic fast-twitch muscle and oxidative slow-twitch muscle; it was not differentially expressed before and after cold stress (Fig. 2A). Western blot and immunofluorescence assays revealed that cold stress increased Myh7 protein expression and slow-twitch fiber proportion, but decreased Myh4 protein expression and fast-twitch fiber percentage (Fig. 2B–D). Collectively, the data demonstrate that cold stress drives a conversion of skeletal muscle fiber types from fast to slow.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Cold stress induces skeletal muscle fiber-type transformation in vivo. Male C57BL/6J mouse were raised in a 4 ℃ environment for one month. (A) The mRNA expression of Myh1, Myh4, and Myh7 in the gastrocnemius. (B) Immunoblots and quantification of Myh1, Myh4, and Myh7 in the gastrocnemius. (C) Immunofluorescent co-staining and quantification of Myh1 (green) and Myh7 (red) in gastrocnemius. Scale bar = 100 µm. (D) Immunofluorescent staining and quantification of Myh4 (red) in gastrocnemius. Scale bar = 100 µm. Data were expressed as mean

Based on the hypothesis that Mib1 influences muscle cell development and differentiation, we examined how cold stress affects muscle proliferation and development. RT-PCR results showed that cold stress upregulated the expression of Mib1 gene (Fig. 3A), which was supported by western blot (Fig. 3B) and immunofluorescence assay (Fig. 3C). The above results showed that cold stress increased Mib1 protein expression.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Cold stimulation increases Mib1 expression and cell proliferation in skeletal muscle. Male C57BL/6J mice were raised at 4 ℃ environment for one month. (A) The mRNA expression of Mib1 in the gastrocnemius. (B) Immunoblots and quantification of MIB1 in gastrocnemius. (C) Quantification of MIB1 and its immunofluorescent staining (red) in gastrocnemius. Scale bar = 50 µm. (D) The mRNA expression of MRF4, myf5, MyoD, and Myogenin in the gastrocnemius. (E) Immunoblots and quantification of MYOD and MYOG in gastrocnemius. Data were expressed as mean

In addition, we examined the expression of muscle development-related genes in the cold stress group, including MYF5, MRF4, MyoD, and MyoG. We found that cold stress up-regulated the expression of MYF5, MRF4, and MyoD in the gastrocnemius, but down-regulated MyoG expression (Fig. 3D). Western blot assay demonstrated that cold stress up-regulated MyoD protein expression, but down-regulated myogenin (MyoG) protein expression (Fig. 3E). This indicates that cold stress may enhance cell proliferation through the upregulation of Mib1, while concurrently exerting an inhibitory effect on cell differentiation.

We found that cold stress upregulated Notch ligands Jagged 2 (Jag 2) and Notch signal downstream factor Hes Family BHLH Transcription 5 (HES5) in gastrocnemius (Fig. 4A). Western blot demonstrated that cold stress increased HES5 protein expression (Fig. 4B). In addition, we detected the amount of

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Cold stimulation activated the Mib1/Notch signaling pathway. (A) The mRNA expression of JAG2, HEYL, and HES5 in the gastrocnemius. (B) Immunoblots and quantification of HES5 in the gastrocnemius. (C) The content of

In vitro studies using C2C12 myotubes were conducted to explore Mib1’s involvement in regulating skeletal muscle fiber phenotypes. We constructed three Mib1-siRNAs, and quantitatively analyzed their knockdown effect. We found that NO.3254 exhibited the most obvious effect (Fig. 5A), and thus we selected this siRNA (NO.3254) for subsequent experiments (Fig. 5B,C). In C2C12 myotubes, siRNA-mediated Mib1 knockdown down-regulated the expression of MyoD and Myh7, but up-regulated the expression of MyoG and Myh4 (Fig. 5D), which was further supported by western blot assay results that siRNA-mediated knockdown of Mib1 increased MyoG, Myh4 protein expression, but decreased MyoD, Myh7, and HES5 protein expression (Fig. 5E). The above results indicated that silencing of Mib1 expression suppressed the Notch signaling pathway, thus affecting muscle development and the composition of muscle fiber types.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Mib1/Notch signaling pathway mediates cold stimulation-induced fiber-type transformation. (A,B) The expression of Mib1 mRNA in C2C12 cells following transfection with either a negative control (si-NC) or siMIB1. (C) The expression of Mib1 protein in C2C12 cells following transfection with either a si-NC or siMIB1. (D) The mRNA expression levels of MyoD, MyoG, Myh1, Myh4, and Myh7 were analyzed in C2C12 cells following transfection with either si-NC or siMib1. (E) The protein expression levels of MyoD, MyoG, Myh1, Myh4, Myh7 and HES5 were analyzed in C2C12 cells following transfection with either si-NC or siMib1. Data were expressed as mean

Skeletal muscle accounts for 40–70% of animal organism mass, and it is a key determinant of whole-body energy metabolism. The growing evidence indicates the importance of skeletal muscle for thermogenesis. Cold stress exhibits a potential to be an adjunctive therapeutic strategy to consume excess energy, and improve metabolic status in patients with metabolic syndrome. Skeletal muscle fiber types are distinguished by myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoforms [25], metabolic enzyme activity [26] and contractile properties [27]. Studies have shown that skin cold stress increases muscle activity [28, 29]. Cold stress can cause involuntary shivering and contraction of skeletal muscle, based on which, we speculated that cold stress might affect the composition of skeletal muscle, especially gastrocnemius muscle fibers.

Our results corroborate existing literature, revealing that cold stress improves endurance, attenuates skeletal muscle fatigue, enhances grip force, and prolongs exercise time. Notably, cold exposure led to an increase in small fiber proportion and a concomitant decrease in large fiber proportion. This shift in muscle fiber size distribution implies a potential influence of cold stress on skeletal muscle contractile function. This change is most likely to be related to changes in muscle fiber type composition. In addition, we also found that cold stress up-regulated slow-twitch fiber-associated genes, but down-regulated fast-twitch fiber-associated genes expression in mixed gastrocnemius. We observed for the first time that exposure to cold stress resulted in a transformation of skeletal muscle fiber types, specifically a shift from fast-twitch to slow-twitch fibers, implying a potential mechanism governed by temperature. Studies have shown that intermittent cold exposure induced a type I to type IIa transition in soleus muscle with no effect on EDL muscle [30], cold exposure led to a significant elevation of slow MyHC1 content in the soleus muscle, a predominantly slow-fiber type [31]. How the muscle fiber type changes in the cold environment needs further research.

Many E3 ubiquitin ligases have been reported to play critical roles in muscle [32]. However, the roles of some E3 ubiquitin ligases in maintaining functions of skeletal muscle remains largely unclear. In our study, we found that the cold stress upregulated Mib1 expression. In addition, our observation that cold stress altered gastrocnemius muscle development and muscle fiber cross-sectional area suggests that it could also influence muscle fiber type composition.

Skeletal muscle fiber-type remodeling involves multiple key signaling pathways, including calcium [33], AMPK [34], and Notch [35] pathways. Cell differentiation in developing muscle critically depends on the Notch signaling pathway. Mindbomb-1 (Mib1) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase, and Mib1 participates in the activation of the Notch signaling pathway. Besides blastocyst morphogenesis and the generation of ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm germ layers [36], Notch signaling pathway is virtually involved in the formation of all tissues investigated, it also acts as a major regulator of stem cell functions. Notch pathway is a highly conserved transmembrane receptor responsible for mediating cell-cell communication [33], and this pathway also plays a key role in cell differentiation and in various stages of muscle development and regeneration including myogenesis [35, 37, 38, 39]. Physiological stimuli such as exercise, injurious muscle contractions, and hypertrophy have been reported to increase Notch signals in young muscle [40, 41, 42]. Whether cold environment or cold stress increases Notch signals remains largely unknown. In this study, we examined Mib1, an essential factor in the Notch signaling pathway, and its downstream factor HES5. We found that cold stress upregulated Mib1 and HES5, suggesting that cold stress could activate Notch signaling to regulate muscle development and myofiber-type transformation by upregulating Mib1.

To further confirm these results, we examined Mib1’s involvement in skeletal muscle fiber type changes using C2C12 myotubes as an in vitro model. Mib1-specific siRNA sequence was constructed and transfected into C2C12 myotubes. siRNA targeting of Mib1 reduced MyoD and Myh7 levels, while elevating Myog and Myh4 expression. Meanwhile, Mib1 knockdown led to a reduction in HES5 expression, and this positive correlation between them was consistent with our in vivo observations that cold stress induced the simultaneous increase in Mib1 and HES5 expressions in skeletal muscle. Collectively, these results demonstrated that low temperature-induced myofiber type transformation might be primarily mediated by the Notch signaling pathway and its downstream transcription factor HES5.

MIB1 and the Notch signaling pathway play key roles in skeletal muscle development. With advancing age, MIB1 becomes indispensable for maintaining glycolytic muscle fibers [17]. Our findings similarly indicate that Mib1 is crucial for preserving skeletal muscle fiber-type composition, particularly during transitions. Moreover, the reduction in MYOD expression following MIB1 knockdown underscores MIB1’s significance in skeletal muscle development. Presence of MIB1 is crucial for skeletal muscle development. As reported in the literature, expression of MIB1 in adolescent muscle fibers activates Notch signal transduction in cycling satellite cells, enabling their transition into adult quiescent satellite cells [43]. MIB1-deficient muscle fibers fail to activate Notch signaling, resulting in cell cycle arrest [37]. Notch signaling plays a crucial role in regulating satellite cells by suppressing their ability to multiply and preserving their dormant state. As a result, the Notch pathway has become a promising therapeutic target for various muscle-related disorders. Following MIB1 knockdown, expression of HES5 decreased, and the latter is a downstream effector of the Notch signaling pathway. Skeletal muscle development critically depends on the MIB1/Notch signaling pathway, as shown by these results.

There are several limitations in this study. Firstly, the relatively small sample size may not fully reflect physiological changes under cold stress, and thus our results need to be validated with larger-sized samples in future experiments. Secondly, the cold stress protocol employed a fixed duration (4 hours daily at 4 °C) without a time-gradient design. This lack of time gradient might result in the instability of some of the observed results. Finally, our analysis of the Notch signaling pathway relied solely on western blot detection of HES5, and thus a more comprehensive analysis is needed in the future studies.

In conclusion, this study revealed that cold stress induced a Mib1-mediated transformation from fast-twitch to slow-twitch fiber types in skeletal muscle. This result indicates the great potential of cold stress as an environmental therapeutic strategy in practical husbandry production, particularly in the production of specialized livestock. The present work also lays a foundation for the development of novel biotechnological applications derived from cold stress therapies.

Cold stress promoted skeletal muscle development, accompanied by increased MyoD expression. Concurrently, cold stress elevated the expression of Mib1, HES5, and Myh7, but declined Myh4 expression. Subsequently, our in vitro experiments validated the positive role of Mib1 in skeletal myofiber type transformation. Knockdown of Mib1 resulted in increased Myh4 expression and decreased expression of both Myh7 and HES5. In summary, our data demonstrate that cold stress promotes the transformation of muscle fibers from fast-twitch to slow-twitch types via Mib1/Notch signaling pathway. Our findings provide theoretical basis and practical references for enhancing muscle health, improving meat quality, and fighting against various metabolism and muscle diseases.

The data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

HDW and YY conceived and designed the study. MXZ, XJW, TTF and TZ executed the experiment and analyzed the tissue samples. JHQ, ZQC, YQS, and JYL analyzed the cell samples. HDW and YY received fundings to support research. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All animal protocols in this study were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanxi Agricultural University. Approval No. SXAU-EAW-2021M.GT.0903. The experiments are conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study tiled with ARRIVE guidelines.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32102634), the Graduate Innovation Project of Shanxi Province (No. 2022Y327), Shanxi Province Excellent Doctoral Work Award-Scientific Research Project (No. SXBYKY2021043, No. SXBYKY2022039), Start-up Fund for doctoral research, Shanxi Agricultural University (No. 2021BQ08, No. 2021BQ69).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.