1 Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Eye & ENT Hospital, Fudan University, 200031 Shanghai, China

2 Department of Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 200011 Shanghai, China

3 Eye Institute and Department of Ophthalmology, Eye & ENT Hospital, Fudan University, 200031 Shanghai, China

4 NHC Key laboratory of Myopia and Related Eye Diseases; Key Laboratory of Myopia and Related Eye Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, 200031 Shanghai, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Quercetin, a naturally occurring flavonoid, possesses anti-inflammatory properties and has emerged as a potential modulator of tissue repair. Impaired wound healing and pathological scarring are often driven by excessive inflammation and dysregulated myofibroblast differentiation. Current therapeutic approaches, however, frequently fall short in simultaneously addressing these intertwined challenges. This study investigates whether quercetin can provide a bifunctional therapeutic advantage by promoting early wound closure through inflammation resolution and suppressing scar formation via the inhibition of myofibroblast differentiation.

A murine excisional wound model was employed to evaluate quercetin’s effects in vivo. Mice (C57BL/6, n = 8/group) received daily topical applications of 1% quercetin. Wound closure kinetics were meticulously quantified using planimetry. To assess molecular and cellular changes, protein levels (CASPASE-1, interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)) and collagen III/I ratios were determined through multiplex qPCR, RNA sequencing, western blot analysis, and histomorphometry. For in vitro investigations, human dermal BJ fibroblasts were treated with transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) (10 ng/mL) ± quercetin (5–50 μM) to assess myofibroblast differentiation markers (α-SMA, collagen I) via immunofluorescence, western blot, and qPCR.

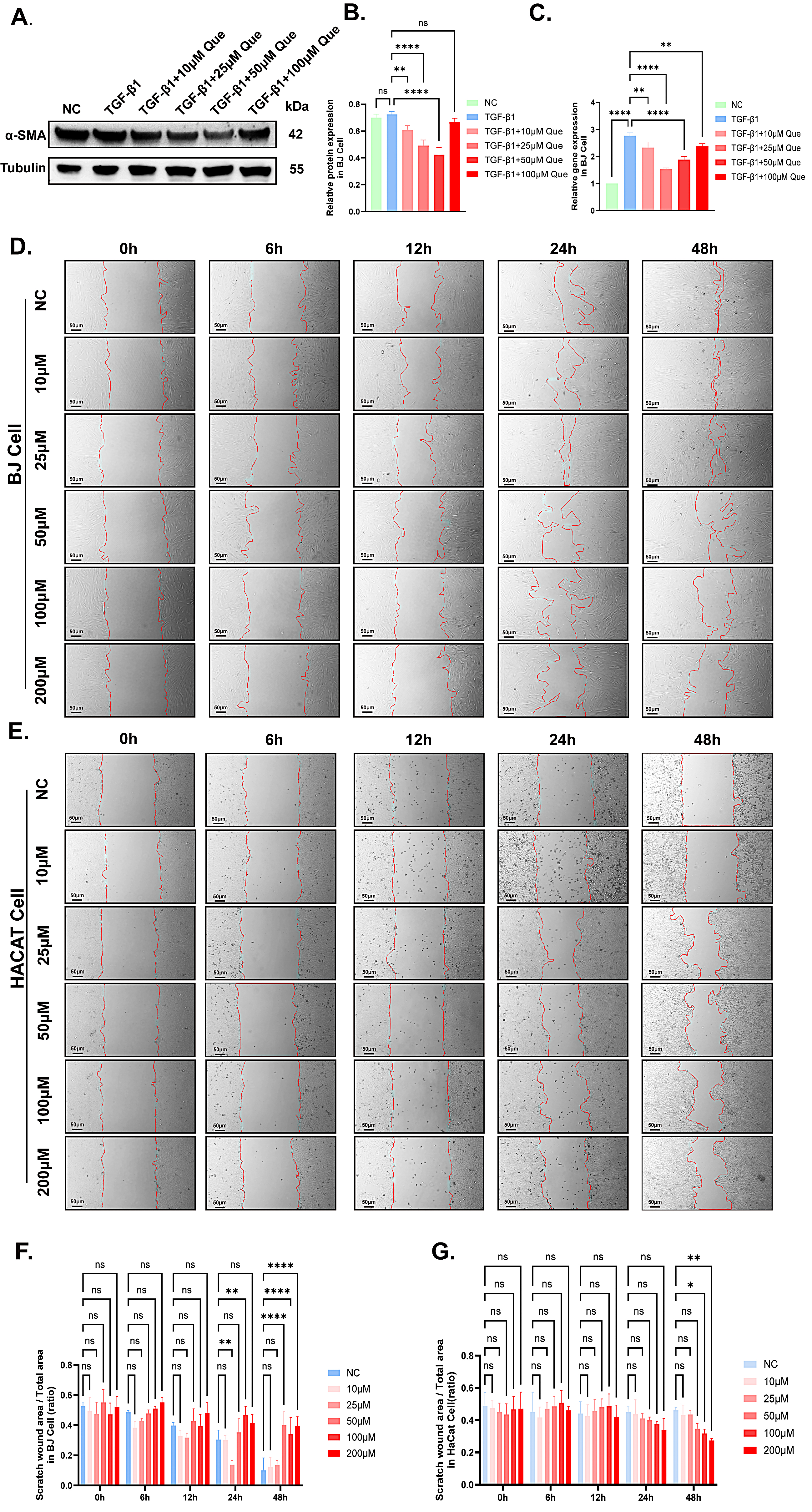

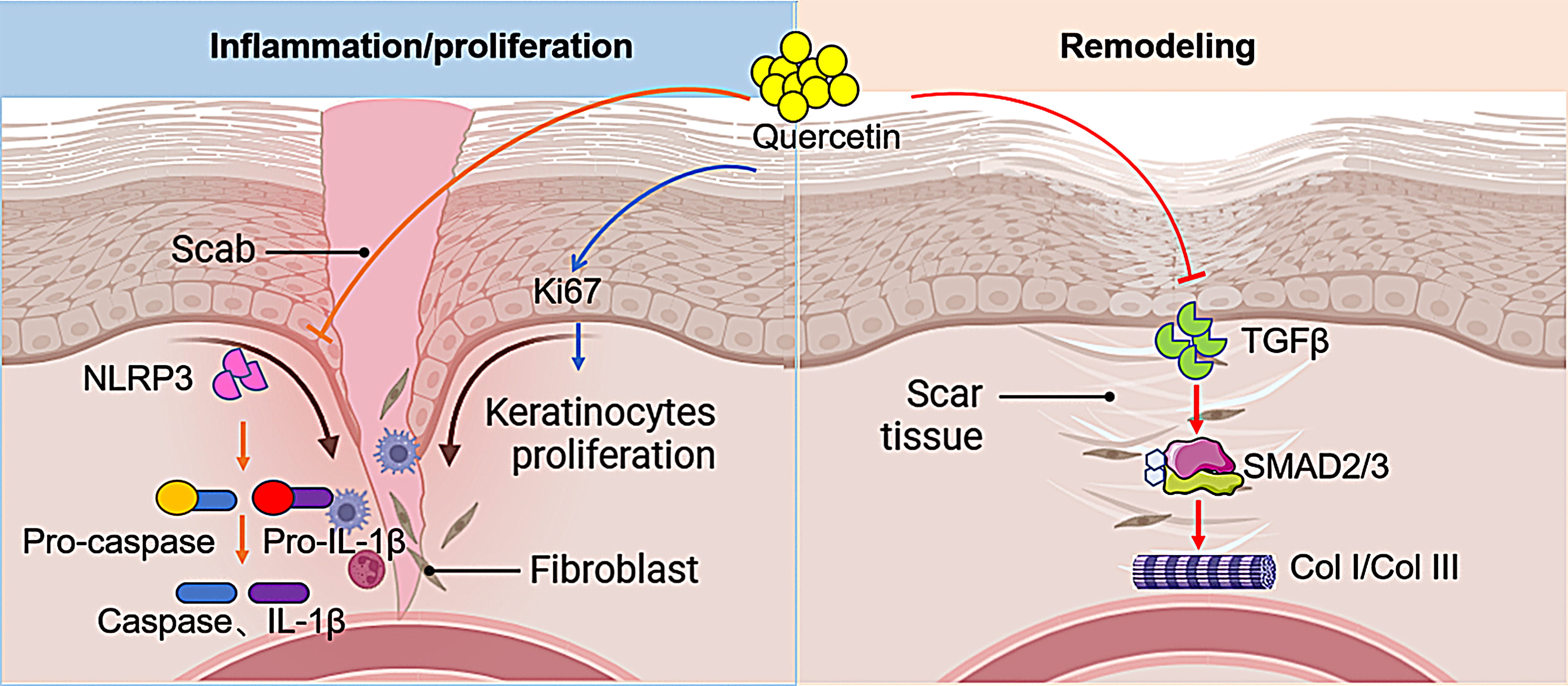

Quercetin significantly accelerated wound closure in vivo. The acceleration was accompanied by a reduction in the expression of IL-1β and CASPASE-1. RNA sequencing data revealed that quercetin’s anti-inflammatory effects in early wound healing involve the modulation of inflammasome complexes, including NLRP3, as well as inflammasome-mediated signaling pathways. Furthermore, treated wounds exhibited increased collagen III/I ratios relative to control groups (p < 0.05), indicative of a more regenerative matrix remodeling process. In vitro, experiments demonstrated that quercetin suppressed TGF-β1-induced myofibroblast differentiation, evidenced by decreased α-SMA expression (p < 0.05) and reduced collagen I synthesis. Notably, quercetin exhibited cell type-specific effects: while suppressing BJ fibroblast migration (scratch assay), it enhanced keratinocyte proliferation. This unique duality prevents aberrant myofibroblast recruitment without compromising essential epithelial coverage—a critical balance for minimizing scar formation.

Quercetin exhibits a compelling dual therapeutic role in wound healing: resolving inflammation to expedite early wound healing and inhibiting TGF-β-driven myofibroblast differentiation to attenuate scarring. By harmonizing these actions, quercetin addresses both phases of repair, positioning it as a promising candidate for scar-free wound therapy. Further efforts should focus on optimizing its bioavailability to enhance clinical translation.

Keywords

- quercetin

- wound healing

- cicatrix

- myofibroblasts

- transforming growth factor beta

- anti-inflammatory agents

Cutaneous wound repair involves tightly regulated phases—hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [1]. Initiated immediately upon injury, hemostasis occurs through vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation to form a clot, controlling bleeding and establishing a provisional matrix [2]. This matrix serves as a scaffold for subsequent cell migration while releasing growth factors (e.g., platelet-derived growth factor, PDGF) to initiate the inflammatory response [3]. In the early stages of inflammation (24–48 hours), neutrophils migrate to the wound, clearing pathogens and necrotic tissue [4]. In the later stages (2 to several days), macrophages release cytokines (such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-

Disruptions to this delicate balance, such as prolonged inflammation or persistent myofibroblast activation, often lead to impaired healing [10] and pathological scarring [11]. Current therapies, like corticosteroids [12] or TGF-

Quercetin, a natural flavonoid compound widely present in the plant kingdom, with a chemical structure of 3,3′, 4′, 5,7-pentahydroxyflavone. It has significant antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immune regulatory functions [15]. Historically, quercetin rich herbs, such as mulberry leaves [16] and locust flowers, have been used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat inflammatory conditions and promote tissue repair, noted for their ability to “clear heat and detoxify, promote muscle growth, and reduce ulcers”. Modern pharmacological research further confirms that quercetin inhibits inflammatory responses by regulating multiple signaling pathways such as NF-

In addition to its strong potential to promote healing, quercetin also possesses properties that prevent fibrosis. Emerging evidence suggests quercetin can modulate TGF-

All procedures were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University (Shanghai, China, Ethics number: 2020096) and followed the protocol from the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978). Male BALB/c mice (8–10 weeks, 22–25 g, purchased from Huachuang Xinnuo Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were housed under standard conditions (12-h light/dark cycle, 22 °C, 50% humidity) with free access to food and water.

Anesthesia: Mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection (i.p.). A combination of ketamine hydrochloride and xylazine hydrochloride was used as the anesthetic agent. The anesthetic dosage was precisely set at ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg, CAS 1867-66-9, Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, Burlington, MA, USA) and xylazine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg, CAS 23076-35-9, Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Prior to injection, the calculated doses of ketamine and xylazine were mixed thoroughly under sterile conditions.

Following injection, mice were placed on warm, clean bedding and monitored closely until the desired anesthetic depth was achieved. Assessment of Anesthetic Depth: Adequate surgical anesthesia (loss of consciousness and nociception) was confirmed by the absence of a pedal withdrawal reflex (elicited by gentle toe pinch) and observation of stable, regular respiratory patterns. Surgical procedures commenced only upon confirmation of sufficient anesthesia.

Preoperative Preparation: Once an appropriate anesthetic plane was confirmed, mice were positioned in ventral recumbency on a sterile surgical platform. The dorsal fur over the intended surgical site (typically the interscapular or lumbar region) was carefully removed using electric clippers or depilatory cream, creating a sufficiently large hair-free area extending well beyond the planned wound margins. The shaved area was aseptically prepared by scrubbing with sterile gauze or cotton swabs saturated with 70% (v/v) ethanol solution, covering an area significantly larger than the surgical field. The skin was allowed to air dry completely.

Wound Creation: Under strict aseptic technique (utilizing sterile gloves and instruments), an autoclavable or disposable sterile skin biopsy punch was employed. Applied perpendicularly with steady pressure to the prepared dorsal skin, the punch was used to create a wound penetrating the full thickness of the skin (epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue). A single, circular full-thickness excisional wound with a precise diameter of 8 mm was generated. The excised skin disc was carefully removed from the punch, ensuring clean, well-defined wound edges without residual flaps or excessive crush injury. Minor bleeding, if present, was controlled by applying gentle pressure with sterile cotton-tipped applicators or gauze, avoiding undue trauma to the wound margins [27].

Postoperative Care: Immediately following wound creation, provision of postoperative analgesia was implemented. This consisted of either subcutaneous infiltration of a long-acting local anesthetic (e.g., 0.25% bupivacaine) around the wound perimeter or systemic administration of an analgesic agent (e.g., buprenorphine or butorphanol), as required by the approved protocol (This step is critical for animal welfare and an ethical requirement). Mice were transferred to individual, pre-warmed (~37 °C) recovery cages placed on a heating pad or under a warming lamp. Animals were monitored continuously until full recovery from anesthesia (evidenced by spontaneous movement and return of righting reflex). Postoperative monitoring included assessment of behavior, activity, wound condition, and overall health status for a minimum of 24–48 hours. Analgesia was administered according to the predetermined schedule.

To prevent wound contraction and mimic human healing, silicone rings (8 mm inner diameter) were fixed around the wounds using surgical glue (Vetbond, Cat no. 1469SB, 3M Company, Maplewood, MI, USA) and sutures (6-0 nylon, Vicryl, Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA). Customized silicone rings (Shanghai Yeyu biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were fixed with surgical glue and sutures to standardize wound healing.

Control group: Topical application of 100 µL PBS dropwise to the wound of each mouse daily.

Quercetin group: Topical application of 1% quercetin (w/w, Cat no. HY-18085, Purity 99.80%, MedChemExpress LLC, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) applied daily.

Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 (TGF-

Wound areas were photographed on days 0, 2, 6, 12, and 28 using a digital camera. Planimetry analysis (Image J software, version 1.54, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) quantified wound areas. Two authors who were blinded to the group assignment conducted the independently measurement and the average was acquired.

On days 2 (inflammation phase), 5 (proliferative phase) and 28 (remodeling phase), mice were euthanized (CO2 overdose). Wound tissues (including 2 mm surrounding skin) were excised, bisected, and either fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (histology) or snap-frozen (molecular analysis).

Harvested wound tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Cat no. P0099-3L, Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) for 24 h at 4 °C, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (70–100%), cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Then, paraffin blocks were cut into 5 µm-thick sections using a rotary microtome (Leica RM2235, Leica Camera AG, Wetzlar, Hesse, Germany). The Sections were deparaffinized in xylene (2

Staining Protocol: The procedure for deparaffinization and hydration were performed as described for as Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining. The sections were stained with Weigert’s iron hematoxylin (Cat no. HT1079, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) for 10 min. Then, the sections were rinsed in acid ethanol (1% HCl) for 5 sec and blued in ammonia water, then were immersed in Biebrich scarlet/acid fuchsin solution (Cat no. HT151, MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) for 5 min to stain cytoplasm. Subsequently, the samples were treated with 1% phosphomolybdic acid (Cat. no. S0094, Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 10 min to remove excess dye and stained with 2% aniline blue (Cat no. B8563, MilliporeSigma) for 5 min to highlight collagen fibers. Finally, the sections were washed in 1% acetic acid for 2 min, while the dehydration and mounting were performed as described in the protocol. All of the images were captured by a microscope (Axio, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) and analyzed by two authors who were blinded to the group assignment.

For IHC, deparaffinized sections were incubated in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95 °C for 20 min using a microwave. Treatment with 3% hydrogen peroxide subsequently occurred for 10 min to quench endogenous peroxidase, followed by 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Cat no. ST2249, Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) in PBS for 30 min to block nonspecific binding. Sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-Ki-67 antibody (1:200 dilution, Cat no. ab15580, Abcam Limited, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK) diluted in PBS containing 1% BSA. Sections were then washed with PBS (3

In Immunofluorescence (IF), the sections were incubated with primary antibody with caspase-1 (1:1000, cat no. GB15383-100, Servicebio Inc, Wuhan, Hubei, China), Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1

The total protein from cells were lysed with pre-cooled radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA, Cat no. P0013B, Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China) buffer, containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Cat no. P9599, F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland). Then, 30 µg of total protein was separated by SDS-PAGE (Cat no. LK301, Shanghai Epizyme Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (MilliporeSigma, MA, USA). After blocking with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h, membranes were respectively incubated with primary antibodies against Alpha-Smooth Muscle Actin (

Mouse skin tissues were homogenized in TRIzol (Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan) using a Bead beater (Biospec), whereas cells were directly resuspended in TRIzol (Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan). Total RNAs were isolated and reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using the Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers were synthetized as in Table 1 (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). RT–qPCR was performed in triplicate using SYBR green master mix (Roche, F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland) on a Step One Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystem, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples with a low yield of RNA were predetermined and excluded. Results were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and the comparative

| Primers | Sequence(5′ to 3′) | Melting Temperature (TM) | Length |

| IL-6-human-F | GGTACATCCTCGACGGCATCT | 59.4 | 21 |

| IL-6-human-R | GTGCCTCTTTGCTGCTTTCAC | 57.5 | 21 |

| IL-8-human-R | TCTCTTGGCAGCCTTCCT | 56.2 | 18 |

| IL-8-human-R | ACTGAACCTGACCGTACATGTCTTTATGCACTGACATCT | 65.0 | 39 |

| IL-1B-human-F | TACGAATCTCCGACCACCACTACAG | 60.1 | 25 |

| IL-1B-human-R | TGGAGGTGGAGAGCTTTCAGTTCATATG | 60.0 | 28 |

| ACTA2-human-F | ACTGAGCGTGGCTATTCCTCCGTT | 62.9 | 24 |

| ACTA2-human-R | GCAGTGGCCATCTCATTTTCA | 55.8 | 21 |

| GAPDH-human-F | CTGAGTACGTCGTGGAGTC | 55.0 | 19 |

| GAPDH-human-R | ACTGAACCTGACCGTACACAGAGATGATGACCCTTTG | 65.9 | 38 |

Total RNA was extracted from mice at 2rd day post-wound, and ribosomal RNA (rRNA), constituting

Stringent quality control was applied: RNA integrity and DNA contamination were assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis; RNA purity (OD260/280, OD260/230) was measured using a NanoPhotometer spectrophotometer (Implen GmbH, Munich, Germany); RNA concentration was precisely quantified using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA); and RNA integrity was accurately determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) using high-density flow cells. This system delivers high throughput (yielding up to 6 Tb and 20 billion reads per run), enabling sensitive detection of coding and diverse non-coding RNAs, even in challenging samples. The platform facilitates multiplexed sequencing of up to 400 transcriptomes per run.

The BJ (Cat no. GNHu49) and HaCat (Cat no. SCSP-5091) cells were kindly provided by Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences (National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures, Shanghai, China). BJ cells were treated with TGF-

The BJ or HaCat cells were seeded in a 96-well plate and treated with quercetin at different concentration for 24 h. The CCK-8 reagent was added to each well and incubated according to manufacturer instructions (cat no. C0037, Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China), and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured to quantify cell viability.

Confluent BJ fibroblasts and HacCaT were scratched separately with a 200 µL pipette tip, washed, and treated with quercetin (0–200 µM) or vehicle. Migration was imaged at 0, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h (phase-contrast microscope). Gap closure was quantified using Image J.

Data are presented as Mean

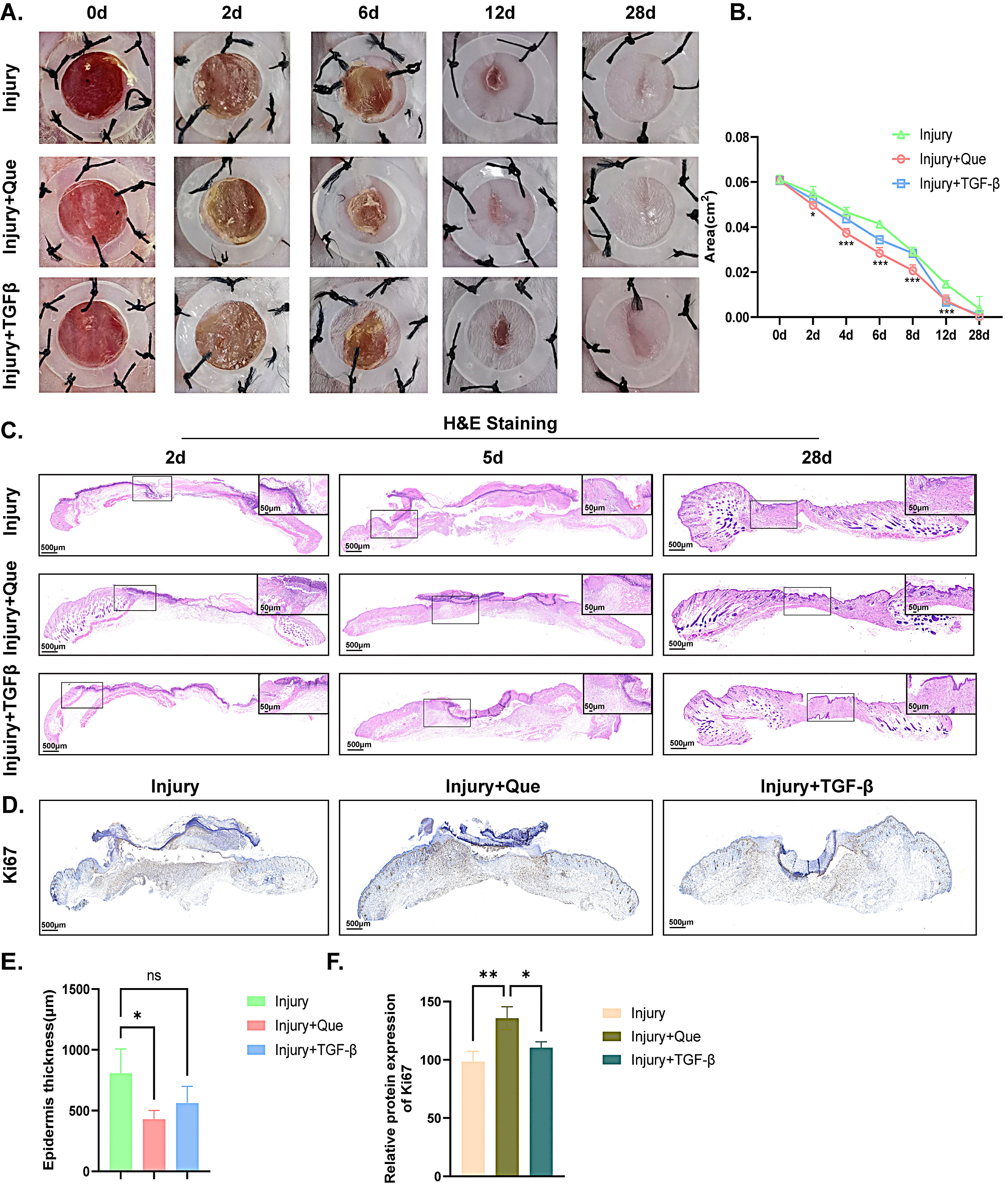

Topical application of 1% quercetin significantly enhanced wound healing in the murine excisional model, and topical application of 1% TGF-

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Quercetin accelerates early wound closure in Mice. (A,B) Photographs of the gross appearance of wound healing in mice and the statistical analysis. (C) HE staining of wound on the 2nd, 5th and 28th day among the three groups. (D) IHC staining of Ki-67 on the 6th day among the three groups. (E) Statistical analysis of epidermis thickness of wound in mice according to HE staining. (F) Quantitative analysis of Ki-67 expression in wound among the three groups. Scale bar = 500 µm or 50 µm. * p

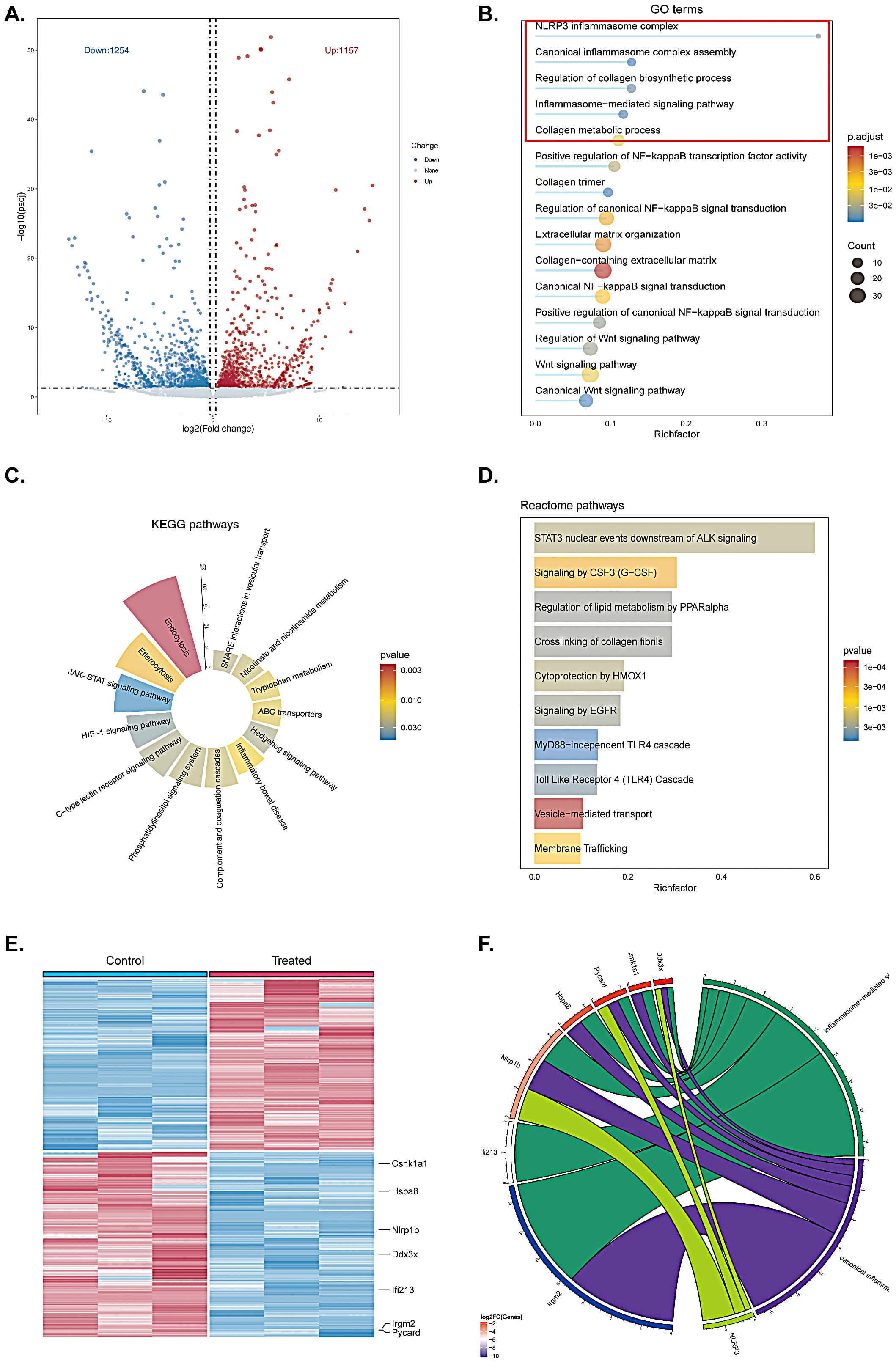

To further elucidate potential targets and signaling pathways involved in quercetin-mediated wound healing, wound tissue was harvested from the vehicle control group and 1% quercetin treated group on the 2nd day, and analyzed with RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). According to previous study, day 2 (approximately 48 hours) post-wounding is a well-suited time point for analyzing the inflammatory response during wound healing, as it captures peak neutrophil and early macrophage activity, along with cytokine and growth factor expression [31]. Considering that the strong anti-inflammatory capability of quercetin, we hypothesized that the promotion of skin healing by quercetin may be related to its anti-inflammatory properties. As shown in Fig. 2A, a total of 21,991 differentially expressed genes were screened out, of which 1157 genes were upregulated and 1254 genes were downregulated, as evidenced by the volcano plot. Furthermore, the enrichment analysis results from Go term, KEGG pathways and Reactome pathways indicated that the differentially expressed genes primarily affected the inflammatory response, such as NLRP3 inflammasome complex, inflammasome-mediated signaling pathway and so on (Fig. 2B–D). Heating map and chord diagram suggested that the inflammation-related genes of NLRP1B, DDX3X, LFI213, IRGM2 and PYCARD were significantly down-regulated in quercetin treated group when compared with the vehicle control group, as depicted in Fig. 2E,F. Taken together, the application of quercetin may regulate the inflammatory response during wound healing.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Quercetin regulates the inflammatory response during early wound closure in mice. (A) Volcano plot illustrating the differentially expressed genes between the vehicle control group and the quercetin treated group. (B–D) Enrichment analyses of GO term, KEGG pathways, and Reactome pathways comparing the two groups. Inflammatory response related pathways are highlighted with red boxes in the GO terms. (E,F) Heat map and chord diagram depicting the inner relationships among differentially expressed genes. n = 3 in each animal group.

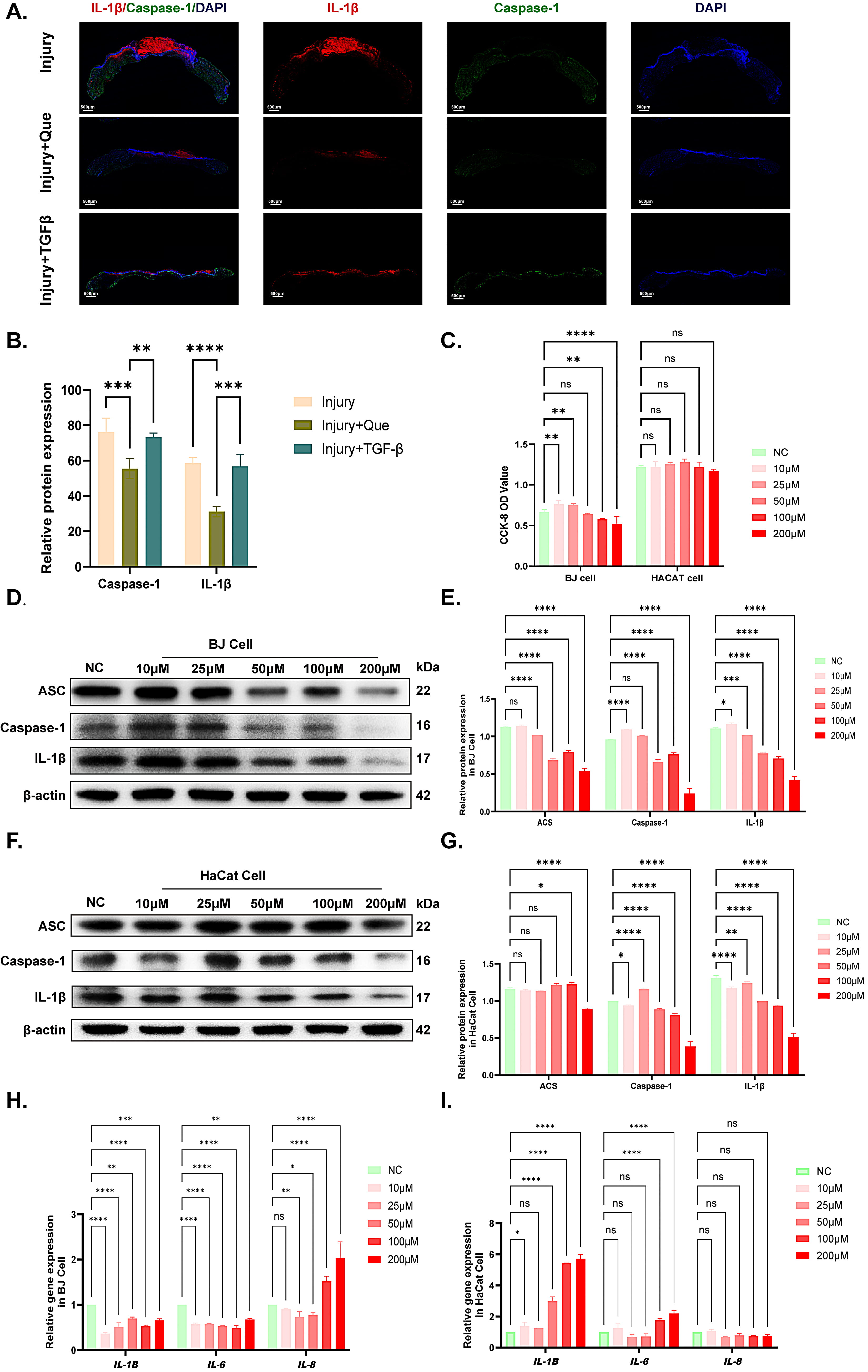

Based on the transcriptomic data, we further validated that quercetin treatment markedly attenuated inflammation during the early phase of wound repair. The results of immunofluorescence in mice revealed significant reduction in IL-1

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in quercetin-treated wound healing. (A,B) IF staining and quantitative analyses of CASPASE-1 and IL-1

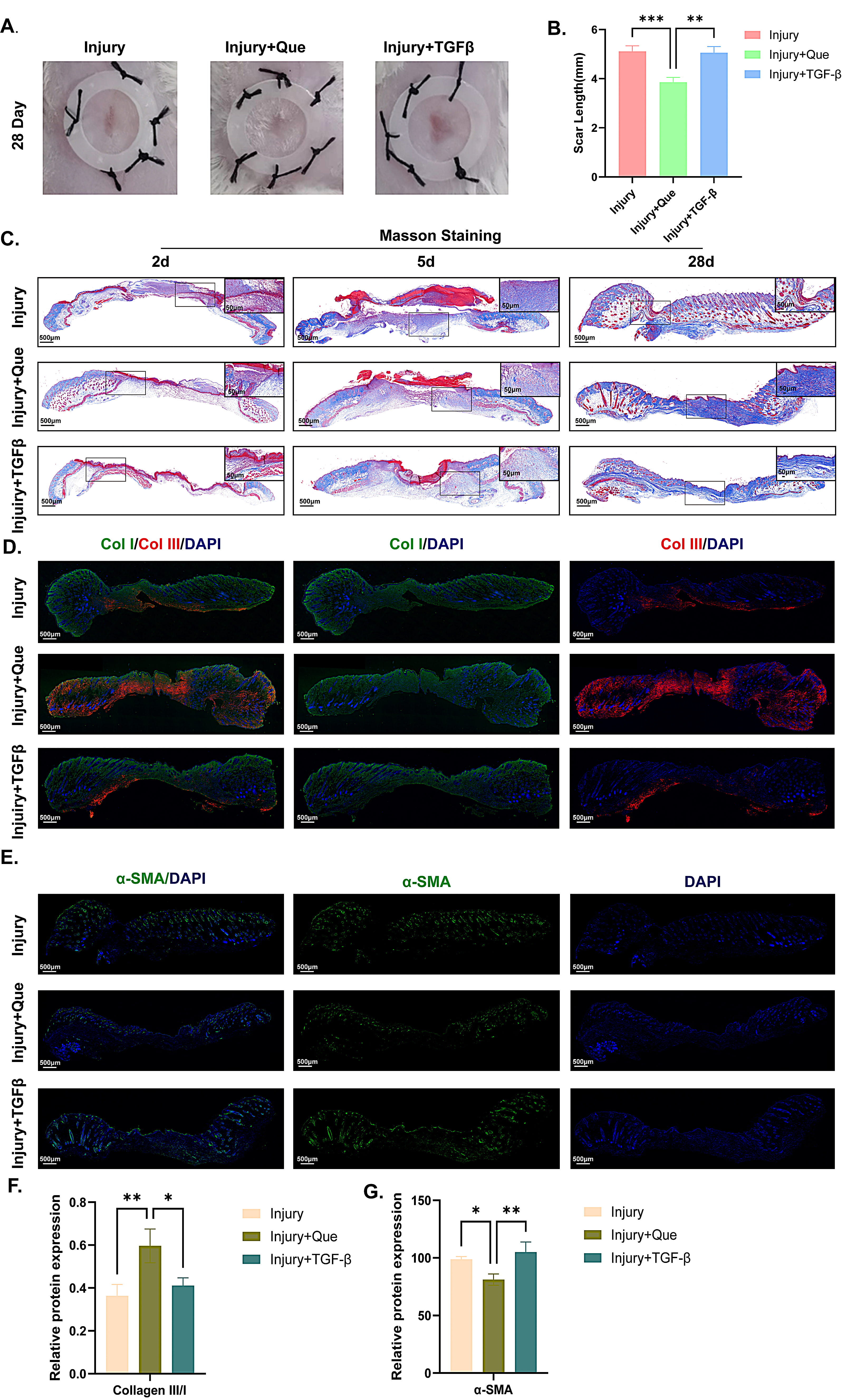

According to the wound healing image on day 28 (Fig. 4A), the positive drug TGF-

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Quercetin modulated collagen deposition and improved scar quality. (A,B) Photographs of scar length and statistical analysis among three groups. (C) Masson staining of wound quality on the 28th day among three groups. (D,E) IF staining of Collagen I/III and

To further investigate the differentiation effect of quercetin on fibroblasts into myofibroblasts, the BJ cells were treated with quercetin only and quercetin with TGF-

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Quercetin inhibited TGF-

Quercetin’s early anti-inflammatory, which involves inhibiting NF-

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Schematic diagram of quercetin in promoting early wound healing and attenuating scar formation (created by BioRender.com).

The accelerated wound closure observed in quercetin-treated mice aligns with its potent anti-inflammatory properties. By suppressing IL-1

The marked increase in the collagen III/I ratio (1.8 vs. 0.9 in controls) in quercetin-treated scars vividly highlights its ability to guide steer collagen synthesis toward a more regenerative phenotype. Type III collagen, characterized by its finer fibrillar structure, is a hallmark of fetal wound healing—a process known for scarless repair [38, 39]. In stark contrast, excessive type I collagen deposition, as seen observed in the TGF-

The seemingly paradoxical observation that quercetin inhibits BJ fibroblast migration (scratch assay) while simultaneously promoting keratinocyte proliferation (Ki-67+ cells) underscores its cell type-specific activity. The suppression of fibroblast migration may prevent excessive myofibroblast recruitment and ECM contraction. Meanwhile, enhanced keratinocyte activity ensures rapid epithelial coverage—a balance critical for scarless healing. Similar cell-selective effects have been reported for compounds like asiaticoside, which promotes keratinocyte migration but inhibits fibroblast proliferation [42]. This inherent duality positions quercetin as a tunable agent capable of addressing distinct phases of repair.

Although our study provides robust preclinical evidence, several limitations warrant consideration. In terms of bioavailability, the efficacy of topical quercetin may be constrained by its poor skin penetration. Further research should explore nanocarriers, like lipid-based nanoparticles, to enhance delivery, similar to strategies used for curcumin in burn wounds [43].

In terms of outcomes, our scar quality assessments were limited to day 28; extended studies are needed to evaluate late remodeling (including assessments of tensile strength at 6 months). Mechanistically, future investigations could involve performing RNA sequencing on skin tissue samples from both quercetin treated and control groups on the 28th day to screen for key factors regulating fibroblast differentiation via the TGF-

Quercetin emerges as a bifunctional agent that harmonizes inflammation resolution, epithelial proliferation, and anti-fibrotic signaling to achieve scar-minimized wound repair. By temporally modulating TGF-

TGF-

All data supporting the findings of the present study are available within the paper or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The study was designed by DW, MYJ and JZ were involved in its execution. DW and MYJ handled data collection and analysis. DW and JZ contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This research was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University (Ethical approval numbers: 2020096). The care and protection of experimental animals were in accordance with the protocols of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978).

We thank LetPub for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171020, 81900817).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.