1 Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering at School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, 200011 Shanghai, China

2 Institute of Developmental Biology and Molecular Medicine, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, 200438 Shanghai, China

3 Department of Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA

4 Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, 200025 Shanghai, China

5 Metabolism and Integrative Biology and Children’s Hospital and Institutes of Biomedical Sciences, Fudan University, 200438 Shanghai, China

Abstract

Heart regeneration requires renewal of lost cardiomyocytes. However, the mammalian heart loses its proliferative capacity soon after birth, and the molecular signaling underlying the loss of cardiac proliferation postnatally is not fully understood.

This study aimed to investigate the role of Catenin alpha 3 (Ctnna3), coding for alpha T catenin (αT-catenin) protein in regulating cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration during the neonatal period.

Here we report that ablation of Ctnna3 and highly expressed in hearts, accelerated heart regeneration following heart apex resection in neonatal mice.

Our results show that Ctnna3 deficiency enhances cardiomyocyte proliferation in hearts from postnatal day 7 (P7) mice by upregulating Yes-associated protein (Yap) expression.

Our study demonstrates that Ctnna3 deficiency is sufficient to promote heart regeneration and cardiomyocyte proliferation in neonatal mice and indicates that functional interference of α-catenins might help to stimulate myocardial regeneration after injury.

Keywords

- Ctnna3

- α-catenins

- cardiomyocyte proliferation

- heart regeneration

- Yap

Heart failure, caused by the loss of cardiomyocytes during injury and disease, is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in humans [1]. The adult mammalian heart has a limited ability to regenerate cardiomyocytes, which is insufficient to restore contractile function after injury. In contrast, the neonatal mammalian heart possesses a remarkable capacity for cardiac regeneration, but this ability is lost by the age of 7 days, coinciding with the onset of cardiomyocyte proliferative arrest [2, 3, 4]. Various experimental strategies have been investigated to restore functional myocardium for repairing the injured heart. These are: (a) cell therapy using embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) and cardiac progenitor cells [5]; (b) reprogramming of nonmyocytes, e.g., cardiac fibroblasts, to a cardiac cell fate (cardiomyocytes) using cardiogenic genes and small molecules; (c) re-activation of cardiomyocyte mitosis in the adult heart [6, 7, 8, 9]. Genetic fate-mapping experiments in the neonatal mice [4] and adult zebrafish [10, 11] indicate that the regenerated cardiomyocytes mainly arise from reactivation of preexisting cardiomyocytes, rather than from undifferentiated stem or progenitor cells. Thus, identifying the genes and thoroughly understanding the mechanisms underlying that regulate cardiomyocyte proliferation and regeneration could provide critical insights for developing new therapeutic strategies for heart failure.

Here we present experimental evidence indicating that deficiency of Ctnna3 is sufficient to promote heart regeneration following heart apex resection in neonatal mice. Our study revealed that cardiomyocyte proliferation increased in neonatal Ctnna3 deficient mice, probably due to the up-regulation of Yes-associated protein (Yap) expression. These results suggest that

The Ctnna3-/- mice (a kind gift from Dr. Radice’s lab at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA) have been characterized previously [19]. Ctnna3-/- (C57/129) mice were crossed to wildtype (WT) Friend Virus B-type (FVB) mice to generate Ctnna3+/- mice. These mice were maintained and raised on a C57/129/FVB genetic background in a specific pathogen-free facility. In this study, we analyzed: (1) apex resection experiments at 7 days post-resection (dpr) (WT, n = 5; Ctnna3-/-, n = 5) and 14 dpr (WT, n = 3; Ctnna3-/-, n = 3); (2) proliferation at (postnatal day 1) P1/P3/P7/P14: WT (n = 5), Ctnna3-/- (n = 5) per time point; (3) cardiomyocyte cultures (WT, n = 9; Ctnna3-/-, n = 12); and (4) cardiac

Neonatal mice (

Cardiomyocytes from neonatal mice were isolated as previously described [20]. Briefly, hearts from neonatal mice at P1 were disassociated with collagenase II (1 mg/mL, #C6885, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The disassociated cells were plated in a 10 cm plate for 2 hours with DMEM/F12 medium (#11330032, Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and the supernatant was collected and cells were re-plated on laminin-coated glass coverslips in 12-well plates at 3

Neonatal mouse apical resection of hearts from P1 pups was performed as described previously [22]. Neonatal mice for apex resection surgeries, pups were anesthetized by hypothermia (3–5 min on ice) and maintained on a cooling plate during the procedure. Postoperative pups were revived on a 37 °C warming pad for 10 min before dam reunion.

Tissue processing, frozen sections and immunofluorescent microscopic analysis were performed as previously described [23]. Briefly, for frozen sections, mouse hearts were dissected out, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (#P6148, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (#10010023, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) overnight, dehydrated with 30% sucrose (#S7903, MilliporeSigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 4 °C for 3 days and then embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) (#4583, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA). Sections were collected at 10 µm.

For histological analysis, mouse hearts were paraffinized and were sectioned at 4 µm followed by hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) staining or Masson’s trichrome (MT) staining (#G1340, Solarbio, Beijing, China) as previously described [24]. For quantification of cardiac fibrosis, images of the MT stained sections were captured with Leica Aperio VERSA microscope (Model Aperio VERSA 8, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and the area of fibrosis in heart apex was determined using Visiopharm software (version 2018.4, Visiopharm, Horsholm, Denmark).

For immunofluorescent analysis, the sections were stained with antibodies against the following proteins: sarcomeric

Standard Western blot protocol was followed. Protein extracts were prepared with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer and then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The antibodies against the following proteins were used in our study:

Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-tests in GraphPad Prism (v9.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are presented as mean

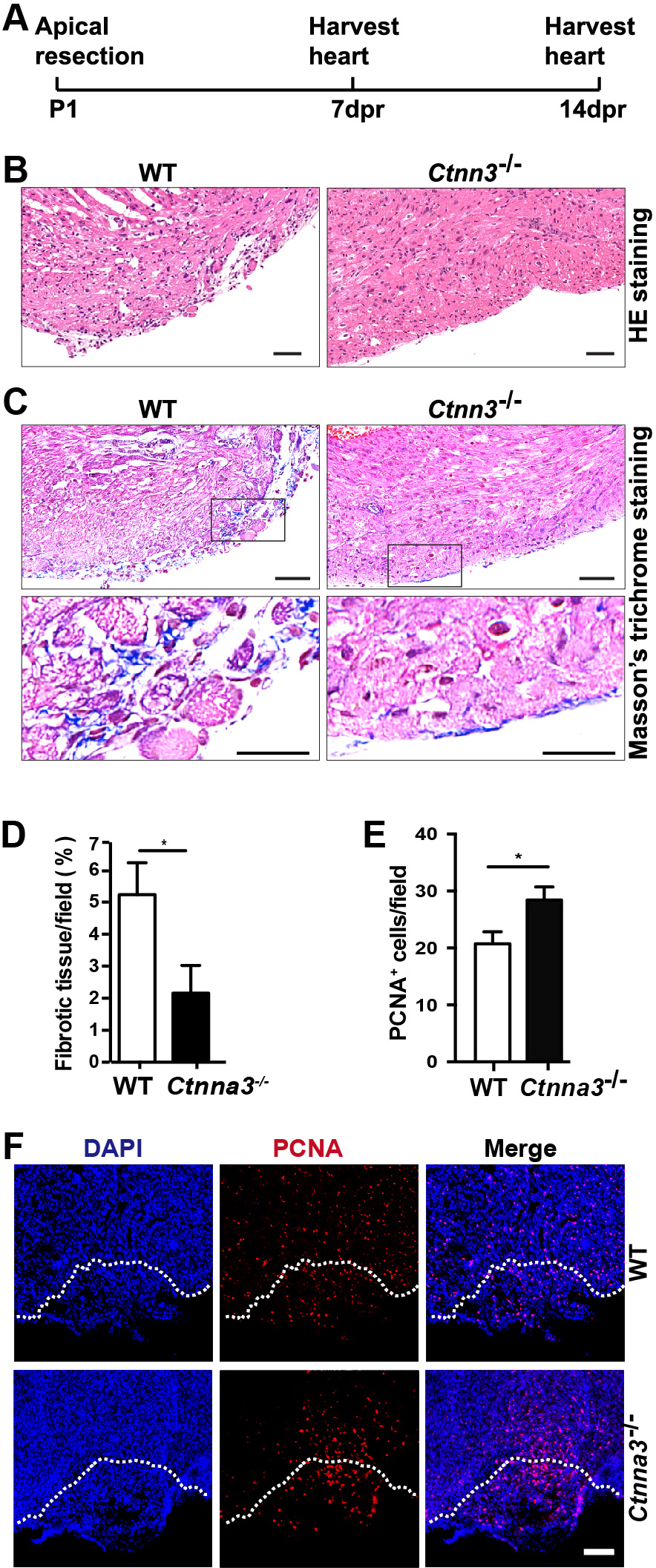

Although the mammalian adult heart is generally considered nonregenerative, neonatal mouse hearts have a genuine capacity to regenerate following apex resection [1, 4]. To evaluate whether Ctnna3 affects heart regeneration, we performed surgical apical resection of hearts (5%~10% of the ventricular myocardium) of WT and Ctnna3-/- neonatal mice at P1 and harvested hearts at 7 and 14 dpr (Fig. 1A) for histological analysis and immunofluorescence staining with antibody against PCNA, separately. To systematically evaluate regeneration dynamics, we analyzed proliferation markers at 7 dpr when cardiomyocyte proliferation peaks [22], and fibrosis at 14 dpr when scar resolution indicates complete regeneration [4] (Fig. 1B–F). This staggered analysis captures both the active proliferative phase (PCNA/PH3/EdU) and ultimate regenerative outcome (fibrosis reduction), providing complementary evidence of enhanced repair in Ctnna3-/- mice. The results revealed that, as reported by Porrello et al. [25], the resection plane was characterized by progressive regeneration of the apex with some restoration of the resected myocardium within 14 days (Fig. 1B). The MT staining showed that the accumulation of fibrotic tissue (blue staining in Fig. 1C) in hearts from Ctnna3-/- mice at 14 dpr dramatically decreased compared with WT mice (Fig. 1C,D). The number of PCNA-positive cells in the border zone of regenerated hearts of Ctnna3-/- neonatal mice at 7 dpr was significantly higher than the counterpart in hearts of WT neonatal mice (Fig. 1E,F). As heart regeneration is thought to occur primarily through cardiomyocyte proliferation [10, 11], our results suggest that loss of Ctnna3 may enhance heart regeneration by promoting cardiomyocyte proliferation in neonatal mice.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Ctnna3 deficiency promotes heart regeneration in neonatal mice after heart apical resection. (A) The scheme of the open thoracotomy experiment. (B,C) Representative images of paraffin heart sections from WT and Ctnna3-/- mice at 14 dpr stained with HE (B) or MT (C). Scale bar = 50 µm. Low panels in (C) are enlarged views of the cropped regions in up panels in (C). (D,E) Statistics analysis of the area of fibrotic tissue per field in C (WT, n = 3; Ctnna3-/-, n = 3) and PCNA-positive cells per field at apex in (F) (WT, n = 5; Ctnna3-/- , n = 5). (F) Representative fluorescent images of frozen sections of mouse hearts at 7 dpr stained with anti-PCNA. White dash lines mark the resection boundaries. Scale bar = 50 µm. Values in D and E represent the means

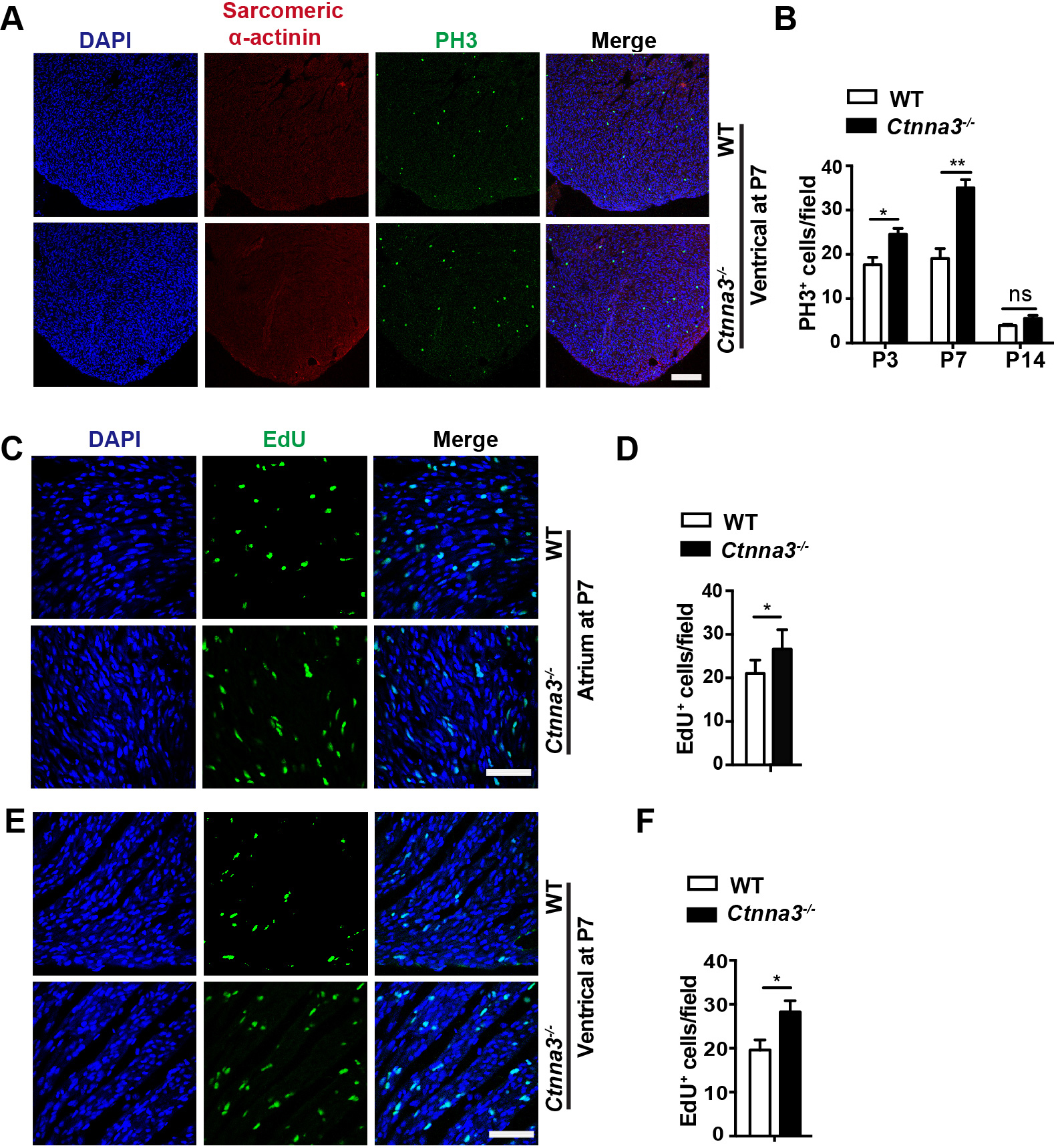

Since cardiomyocytes in neonatal mouse heart retain active proliferation before P7 [3], we tested whether Ctnna3 deficiency promoted cardiomyocyte proliferation in neonatal mice. The ventricles of WT and Ctnna3-/- mice at P1, P3, P7 were sectioned and stained separately with antibodies against PH3 (a marker of mitosis) [26], and Sarcomeric

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Enhanced cell proliferation in hearts of Ctnna3-/- neonatal mice. (A) Representative florescent images of mouse heart sections from P7 WT and Ctnna3-/- mice co-stained with anti-PH3 (for prophase mitotic cells) and anti-Sacrometric-

To further verify the enhanced cell proliferation in Ctnna3-/- neonatal mice, the proliferating cells in Ctnna3-/- and WT neonatal mice at P7 were in vivo EdU-pulse labeled and detected by EdU staining (see Materials and Methods). The results showed that the number of EdU-positive cells was significantly increased in ventricles and atriums of Ctnna3-/- neonatal mice compared to those in control littermates (Fig. 2C–F). These results demonstrate that Ctnna3 deficiency promotes cell proliferation in neonatal mouse hearts.

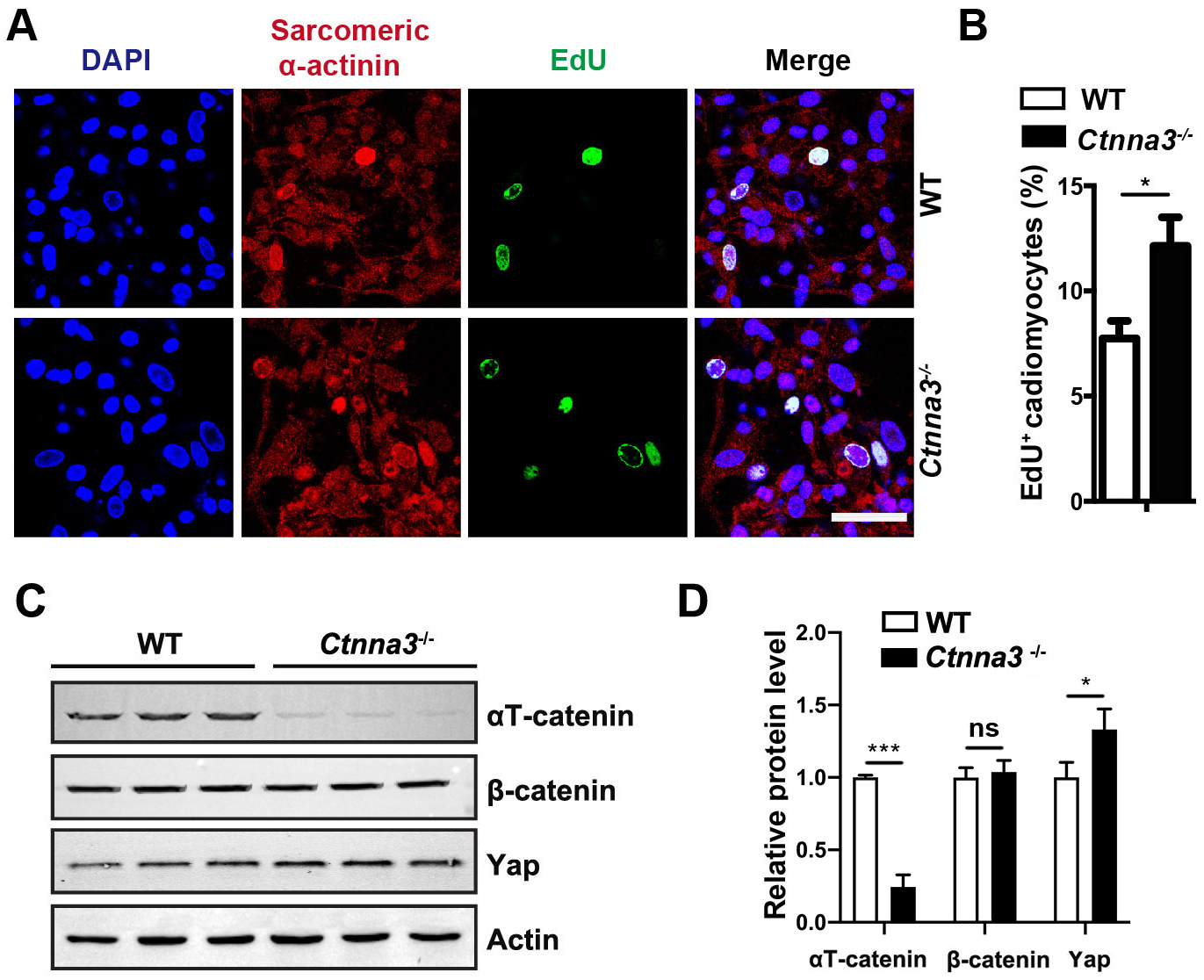

Since heart is mainly composed of cardiomyocytes, in addition to several other types of cells, such as cardiac fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells [28], we hypothesized that Ctnna3 deficiency promoted the proliferation of cardiomyocytes. To test this hypothesis, primary cardiomyocytes were isolated from P5 WT and Ctnna3-/- mouse hearts and pulse-labelled with EdU in vitro followed by immunostaining with antibody against sarcomeric

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Ctnna3 deficiency promotes proliferation of primary cardiomyocytes and up regulates Yap expression. (A) Representative fluorescent images of cultured primary mouse cardiomyocytes from neonatal WT and Ctnna3-/- mice. The cultured cells were pulse-labeled with EdU for 24 hours followed by fluorescent staining. Scale bar = 100 µm. (B) Statistics analysis of EdU-positive cardiomyocytes per field in (A). (WT, n = 9; Ctnna3-/-, n = 12). (C,D) Western blot analysis (C) and quantification (D) of

The Hippo pathway is a key regulatory signaling pathway for heart development and organ size [29]. Thus, we inspected whether loss of Ctnna3 only had any effect on Yap expression in the neonatal heart. Our study revealed that the protein level of Yap significantly increased in hearts from P7 Ctnna3-/- mice compared to that in control mouse hearts (Fig. 3C,D). This result suggests that Ctnna3 deficiency may promote neonatal cardiomyocyte proliferation by enhancing Yap expression.

In this study, we investigated the role of Ctnna3 deficiency in enhancing cardiac regeneration and cardiomyocyte proliferation in neonatal mice. Our findings suggest that the absence of Ctnna3 plays a significant role in promoting cardiac repair processes, potentially through the modulation of key signaling pathways.

Our results indicate a significant upregulation of Yap protein levels in Ctnna3-deficient hearts, implicating the Hippo pathway as a key regulatory mechanism [29]. The Hippo pathway is crucial for heart development and organ size control, and the observed increase in Yap suggests that Ctnna3 may normally act to suppress Yap expression or activity [30, 31, 32, 33]. This upregulation of Yap in the absence of Ctnna3 may enhance cardiomyocyte proliferation by activating growth-promoting signals, which are critical during neonatal heart regeneration.

Several limitations should be considered. Firstly, this study utilized neonatal mouse models, which may not fully replicate the complexity of human cardiac biology and regeneration [34, 35]. The inherently higher regenerative capacity of neonatal mice may amplify the effects observed in Ctnna3-deficient models and future work should include transcriptomic analyses but emphasize that our combinatorial approach (histology + biochemistry) is established in regeneration studies, long-term effects and external factors (genetics, environment) were not studied [35, 36, 37].

Despite these limitations, our findings open promising avenues for future research and potential therapeutic applications. Future studies should aim to develop gene therapy or pharmacological approaches to modulate Ctnna3 activity [38]. Personalized medicine approaches, tailoring interventions based on genetic backgrounds and specific cardiac conditions, could complement these efforts [39]. Integration with existing cardiac therapies, such as stem cell treatments or biomaterials, may provide synergistic benefits, enhancing overall cardiac repair efficacy [40, 41].

In conclusion, we demonstrate that Ctnna3 deficiency alone enhances neonatal heart regeneration through Yap-mediated cardiomyocyte proliferation. These findings identify

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

SZ and WD performed experiments and wrote the manuscript; JL provided Ctnna3-/- mice and expert guidance in the experimental design of transgenic mouse studies; WT and HW designed the study and revised the manuscript; ZC analyzed data and edited the discussion. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Institute of Developmental Biology and Molecular Medicine, Fudan University (Approval No. 201902065S), in accordance with NIH guidelines. We confirm the authenticity of this statement.

We are grateful to Xiaoqing Li for taking care of mice, we also acknowledge the technical assistance of Peng Xiangwen.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2016YFC1000500) and Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (Grant No. 201409001500).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.