1 Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Genoa, 16132 Genoa, Italy

2 Interventional Pulmonary Unit, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, 16132 Genoa, Italy

3 First Clinic of Internal Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Genoa, 16132 Genoa, Italy

4 Italian Cardiovascular Network, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, 16132 Genoa, Italy

5 Cardiac Thoracic and Vascular Department, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino,16132 Genoa, Italy

6 Department of Internal Medicine, University of Genoa, 16132 Genoa, Italy

7 Molecular Pathology Unit, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, 16132 Genoa, Italy

Abstract

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) constitutes a valuable diagnostic approach for the differential diagnosis of various pulmonary fibrotic diseases. BAL fluids from patients with interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) can also be utilized for research purposes, offering cell populations suitable for functional and phenotypical studies. In this study, we demonstrate the feasibility of isolating a discrete number of fibroblasts/myofibroblasts in vitro from the BAL fluid from ILD patients, a procedure typically performed during the early stages of disease when high-resolution computed tomography does not yield a definitive diagnosis.

We obtained BAL samples from a total of 43 patients. Fibroblasts were successfully derived in vitro from 20 patients, with larger quantities of cells from 11 patients. Whenever possible, the cells were cultured and expanded until passage 12–15. Fibroblasts could be expanded to passage 36 in only one case. The expression of typical fibrotic markers, such as type I collagen, α-smooth muscle actin, and fibronectin-extra domain A or B (FN-EDA/-EDB), was therefore compared in fibroblasts obtained from ILD-patients with fibroblasts derived from non-diseased controls by quantitative RT-PCR, immunofluorescence, and cytofluorographic analysis. The rate of proliferation, migration, and response to the anti-fibrotic drug pirfenidone was further determined in 2D and in 3D models of in vitro cultures.

A specific morphological heterogeneity among fibroblasts/myofibroblasts derived from patients with fibrotic or non-fibrotic ILD was observed, such as enlarged and flattened shaped cells vs spindle-shaped cells. Moreover, a higher expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), type I collagen (collagen I), and fibronectin was demonstrated in ILD fibroblasts than in control fibroblasts. The anti-fibrotic drug pirfenidone was effective in inhibiting the growth and migration of ILD-fibroblasts both in 2D and 3D in vitro models.

Collectively, the present study suggests that BAL-derived fibroblasts from ILD patients may serve as a useful in vitro model for studying and assaying pulmonary fibrosis. This approach has the potential to improve our understanding of ILD pathogenesis and overcome ethical and availability concerns associated with biopsy-derived tissues.

Keywords

- interstitial lung diseases

- bronchoalveolar lavage

- fibroblasts

- in vitro testing

- pirfenidone

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a large and heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by damage to the lung parenchyma due to the combination of inflammation and fibrosis. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is regarded as the prototype of fibrosing ILD. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, which progressively displays fibrotic invasion and loss of lung function, has a poor prognosis, with a median survival of three years from diagnosis [1]. Not all ILD are associated with progressive fibrosis; those that develop this phenotype however display a clinical course similar to IPF [2]. Up to a third of ILD are estimated to develop advanced fibrosis [3]. Progressive fibrosis interstitial lung disease (PF-ILD) is not a clinical entity but describes a group of ILD with similar clinical behavior: this phenotype may occur in patients displaying different etiologies, and it is more frequently seen in hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic sclerosis (SS), idiopathic non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), and unclassifiable ILD, whereas it seems to be uncommon in others such as lymphoid interstitial pneumonia or organizing pneumonia [3, 4, 5]. A clear comprehension of the patho-biological mechanisms occurring in the different ILD appears therefore a challenge for correct diagnosis and treatment. Optimization of ILD diagnosis, other than requiring a multidisciplinary approach involving pulmonologists, radiologists, and pathologists, may include bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) examination in clinical guidelines, further encouraging standardization of BAL procedures. Moreover, the cellular analysis of BAL is of great importance for diagnosing inflammatory and infectious processes occurring at the alveolar level, providing additional insights into the underlying pathogenic mechanisms [6].

In IPF, fibroblasts/myofibroblasts and epithelial cells (alveolar cells of type I–II) have emerged as the major players. Myofibroblasts accumulate in IPF lungs forming typical zones of collagen deposition called “fibroblastic foci” that, as the predominant sites of excess matrix production, can be thought of as the leading edge of active fibrosis [7, 8]. These changes in the extracellular matrix (ECM) composition contribute to IPF progression leading to distortion of lung architecture and homeostasis. The multiple origins of the fibroblasts are however still a matter of debate, being possibly due to the proliferating resident fibroblasts, to epithelial-mesenchymal-transition of epithelial, endothelial, or mesothelial cells, or to circulating blood mesenchymal precursors migrating into the lung [9, 10, 11]. We have addressed here the possibility of deriving and expanding in vitro fibroblasts from the BAL of ILD patients. Although BAL-derived fibroblasts growing in vitro for a long time are not easy to obtain, this procedure can be of useful for research studies, further overcoming ethical concerns linked to the utilization of biopsy-derived tissues. In addition, while cells derived from lung biopsies are generally obtained from patients with late stage of disease, in this way it is also possible to obtain fibroblasts even from patients with early disease. Comparative analyses of fibroblasts derived from different ILD disorders may further shed new light on the pathogenesis as well as on molecular mechanisms underlying progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Here we further show how the possibility of managing discrete quantities of primary ILD-fibroblasts could be of interest to develop various models of 3D-cultures to better assess features of these cells in a more physiological system, and either to exploit pre-clinical testing of in-use, or novel, therapeutic agents. Multi-omics studies comparing fibroblasts/myofibroblasts from various ILD will be of further help to clarify the pathobiology of pulmonary fibrosis progression.

The present study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa, Italy (protocol code ILDFIBRO020, n. of Register CER Liguria: 523/2020 DB id 10931) and conducted according to the current national and international guidelines; within the study, biological samples were anonymized prior to processing. For patients the diagnosis was based on international criteria [12, 13]. After multidisciplinary discussion of the Interstitiopathy Lung Disease (ILD) group of the case, and after signing an informed consent form, explicitly authorizing the use of biological samples and any derivative thereof for research purposes, the patient underwent a transbronchial cryobiopsy with bronchoalveolar collection for diagnostic purposes [14]. Aliquots of BAL fluid unused for diagnostic purposes (15–25 mL) were therefore processed for additional research procedures. The clinical features of the patients employed in this study are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1,2. The total lung capacity (TLC), forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1), and diffusing capacity (DLCO) were measured according to international guidelines [12, 13].

Primary derived bronchial fibroblasts were derived from fresh ILD-

bronchoalveolar lavage, 15 mL which is the small fraction normally left unused

for routine diagnostic analyses. Cells of the BAL fluids were first pelleted by

centrifugation. While supernatant was recovered and frozen for different types of

investigations, cells were resuspended in 6 mL of complete medium (RPMI-1640 +

10% fetal calf serum (FCS); Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA), seeded in a 24 well

plate and cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Fibroblast growth factor 2

(FGF2; 3 ng/mL; Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) was added 1 day

after. The medium was changed once a week with the addition of FGF2. In some

cases, after 2–3 weeks, a good number of spindle-shaped cells attached to the

bottom of the well could be observed. These cells were therefore cultured until

confluence, detached by the use of 1

The MRC5 cell line (from Interlab Cell Line Collection “ICLC” IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa, Italy), fibroblasts isolated from the lung tissue derived from a white male, 14-week-old embryo, was cultured in flasks in complete medium (RPMI+FCS10%) (Euroclone S.p.A). Cells reaching confluence were detached by trypsin 1X (Euroclone S.p.A), split or either frozen. Primary fibroblasts were further derived from the BAL of a patients with no evidence of pulmonary fibrosis while skin fibroblasts derived from a healthy subject were used as a further control.

We also utilized the A549 cell line (obtained from ICLC, IRCCS Ospedale

Policlinico San Martino, Genoa, Italy) that, although derived from lung

adenocarcinoma, is experimentally utilized as representative of alveolar basal

epithelial cells [15]. We also used the human umbilical vein endothelial cell

line HECV (from ICLC, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genoa, Italy). Both

these cell lines were cultured as monolayer in flasks in RPMI+FCS 10%, detached

when they reached 70% confluency by 1

Briefly, cells were washed in a PBS solution (Euroclone S.p.A.), trypsinized and

collected by centrifugation (400

Morphological features of live cultured cells were examined under an inverted

Olympus CKX-41 microscope (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan); images were acquired

using a Nikon Digital Sight DS-5Mc equipped with the NIS-Elements F2.20 software

(Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Expanded fibroblasts were also analyzed for the

expression of CD105, CD90, CD73, CD45, Vimentin, type I Collagen,

To determine the expression of F-actin fibers by immunofluorescence, fibroblasts

were cultured in eight-well chamber slides (Nunc International, Rochester, NY,

USA) in a total volume of 300 µL of culture medium and then treated

with transforming growth factor-

Fibroblasts were cultured in 24 well plates, washed with PBS 1

Available aliquots of cells, BAL-patients originated, were expanded in complete

medium (RPMI + FCS10%), detached with Trypsin 1

Fibroblasts of different patients were also used to perform wound scratch tests;

cells were seeded in 24-well plates to a density of 104 cells/mL, let adhere

and proliferate to semi-confluency in complete/treatment medium. A sterile 200

µL-micropipette tip was then used to generate a scratch onto the full

length of the cell layer, along the diameter of each well. Cells were then washed

in PBS and treatments started by the addition of TGF-

Using ultra-low attachment 96 well U bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Maybachstr 2, 72636 Frickenhausen, Germany) we further established 3D in vitro cultures of ILD-fibroblasts (Spheroids) or of ILD-fibroblasts together with epithelial/endothelial cells (Organoids). Spheroids and Organoids were then tested with Pirfenidone (D.B.A. Italia). To this aim 4000 ILD-fibroblasts or A549 or HECV (Spheroids) or either 2000 ILD-fibroblasts + 3000 A549 or HECV cells (Organoids), were re-suspended in 50 µL of complete medium (RPMI+FCS 10%), seeded in each well and then cultured in the incubator at 5% CO2 and 37 °C for 48 h. After 48 h, 50 µL of complete medium with/without Pirfenidone were added. Pirfenidone was used at a concentration of 300 µg/mL in the final volume of 100 µL of culture medium for each well. After additional 72 h the images of each Spheroids or Organoids, treated or untreated with Pirfenidone, were acquired using a Nikon Digital Sight DS-5Mc as detailed above. Subsequently the size of untreated or treated spheroids or organoids was determined by measuring their visible area by means of the available tools of the free software Image J version 1.53.

Analysis of invasion by spheroids in a 3D model was performed based on the procedures described by Dsouza KG and co-authors [16] with some modifications. Spheroids were preliminarily prepared as above described and cultured for 48 h in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C. After 48 h pre-cooled collagen (PureCol EZgel; Advanced Biomatrix; Carlsbad, CA, USA) was first diluted with RPMI-1640 at a concentration of 1 mg/mL and gently mixed avoiding the formation of air bubbles. A volume of 50 µL/well of this solution was added to cover the layer of flat-bottom 96 well plates, subsequently incubated at 5% CO2 and 37 °C for 2 h. This layer prevents contact of spheroids with the plastic of the well. Growth medium was partially removed from previously formed spheroid and each spheroid was picked up and pipetted in a small drop of collagen 1 (100 µL), previously dispensed on the bottom of a petri dish, with/without half of the needed Pirfenidone concentration. This procedure was applied to allow a better inclusion of the spheroid in the matrix. After 15 min, each spheroid was moved onto each collagen-coated 96 flat-bottom wells. Following 30 min-incubation 50 µL of complete medium with/without half concentration of Pirfenidone were added. Final concentration of Pirfenidone was therefore 300 µg/mL. Plates were then incubated at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator and evaluation of the invasion area was determined at different time points (24, 36, 48, 72, 132 h). The area dimensions were calculated by subtracting the inner core-spheroid area (ICA) from the total area covered by invading cells (outer cell borders, OCB) and the spheroid itself, obtaining the derived growth area (OCB-ICA). The calculated (OCB-ICA)/OCB ratio was then used to express the percentage of the area occupied by growing cells.

Whenever indicated, Student-t test and the Bonferroni’s correction were

applied to evaluate the statistical significance; *: 0.01

Clinical details of the patients employed in the present study are reported in Supplementary Tables 1,2. For research purposes, we received the bronchoalveolar lavage of 43 ILD patients that were out of treatment. These patients were subjected to bronchoscopy and/or to criobiopsy for diagnostic purposes. Based on clinical, histological and cytofluorographic analyses the patients were then diagnosed as IPF (N = 23), fHP (N = 3), CTD-ILD (N = 5), IPAF (N = 4), NSIP (N = 3), Sarcoidosis (N = 3) and IgG-related disease (IgG4-RD, N = 2) (see Supplementary Tables 1,2).

Fibroblasts were derived from the BAL fluids of ILD patients. In a number of

cases the cells could be expanded only for a short time, while in a few cases we

could grow the cells for a longer time and for numerous passages (usually 10–12

or 36 in a unique case). Briefly, cells of the BAL fluid were first pelleted by

centrifugation and then seeded in a 24-well plate in complete culture medium,

adding a sub-optimal concentration of FGF2 the next day. In some cases, after

8–10 days, a few fibroblasts started to grow and to form colonies: fibroblasts

reaching confluence were then detached and in part processed for RNA studies.

When possible, the remaining cells were re-seeded and expanded in 24 or 6-well

plates. Through this procedure we could derive a small number of cells from 20

ILD BAL fluids, out of 43 received (46%). Among these 20 samples we could

further derive a larger quantity of cells from 11 patients (25%; 3 IPF, 2 fHP, 1

Sarcoidosis, 3 IPAF, 1 CTD-ILD and 1 NSIP) (Supplementary Table 1).

Morphological features of fibroblasts derived from some ILD patients, as compared

to the control cell line MRC5, are shown in Fig. 1A. Fibroblasts derived from one

IPF patient, as well as those from two fibrotic HP patients, appear flattened and

enlarged with a polygonal aspect, as compared with fibroblasts derived from

patients with NSIP, IPAF, CTD-ILD, or either the control cell line MRC5, that are

more spindle shaped. These observations highlight that fibroblasts derived from

different ILD patients may show a certain heterogeneity, possibly related to

higher levels of fibrosis observed in IPF or in fHP, than in the others (see

Supplementary Table 1). This evidence could further support the

suggestion that these fibroblasts might be truly representative of the ongoing

fibrotic process. Fig. 1B,C further display the expression of

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Differences in morphological features or level-senescence among

fibroblasts derived from various ILD patients (fibrotic vs non-fibrotic)

or in comparison with the control cell line MRC5. (A) Morphological

representation of fibroblasts derived from different ILD patients versus fibroblasts derived from a healthy lung-fibroblast cell line. Red arrows

indicate cells with enlarged and flattened shapes, typical of myofibroblast

differentiation. (B) a higher number of cells positive for

From the RNA of fibroblasts derived from 19 patients, we further examined, by

quantitative RT-PCR, the expression of specific markers, such as

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Quantitative RT-PCR determination and cytofluorographic analysis

of typical markers of fibroblast/myofibroblast differentiation in cells derived

from ILD patients versus controls. (A) mRNA expression of alpha-SMA, collagen

type-I, fibronectin and FGF2 receptor was higher in fibroblasts from ILD patients

than in fibroblasts from controls (CTR). (B) Mean Fluorescence Intensity (Mfi) of

Cytofluorographic analyses of fibroblasts derived from representative ILD

patients have further shown that typical markers of mesenchymal/fibroblast cells

were expressed in all the derived fibroblasts such as CD105, CD90 and CD73

(Supplementary Fig. 1). These fibroblasts were also positive for

vimentin but negative for CD45 (data not shown), thus confirming that they are of

mesenchymal and not of hematopoietic origin, such as fibrocytes. We further

observed that ILD-fibroblasts display a higher expression of

We next evaluated proliferative response of ILD-fibroblasts to FGF, TGF

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of the proliferative response to FGF2 or to

TGF

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Determination of dose-dependency effect of Pirfenidone.

(A) Evaluation of the growth of fibroblasts derived from 3 different

ILD patients treated with increasing doses of Pirfenidone (150, 300 and 400

µg/mL). Histograms represent the mean

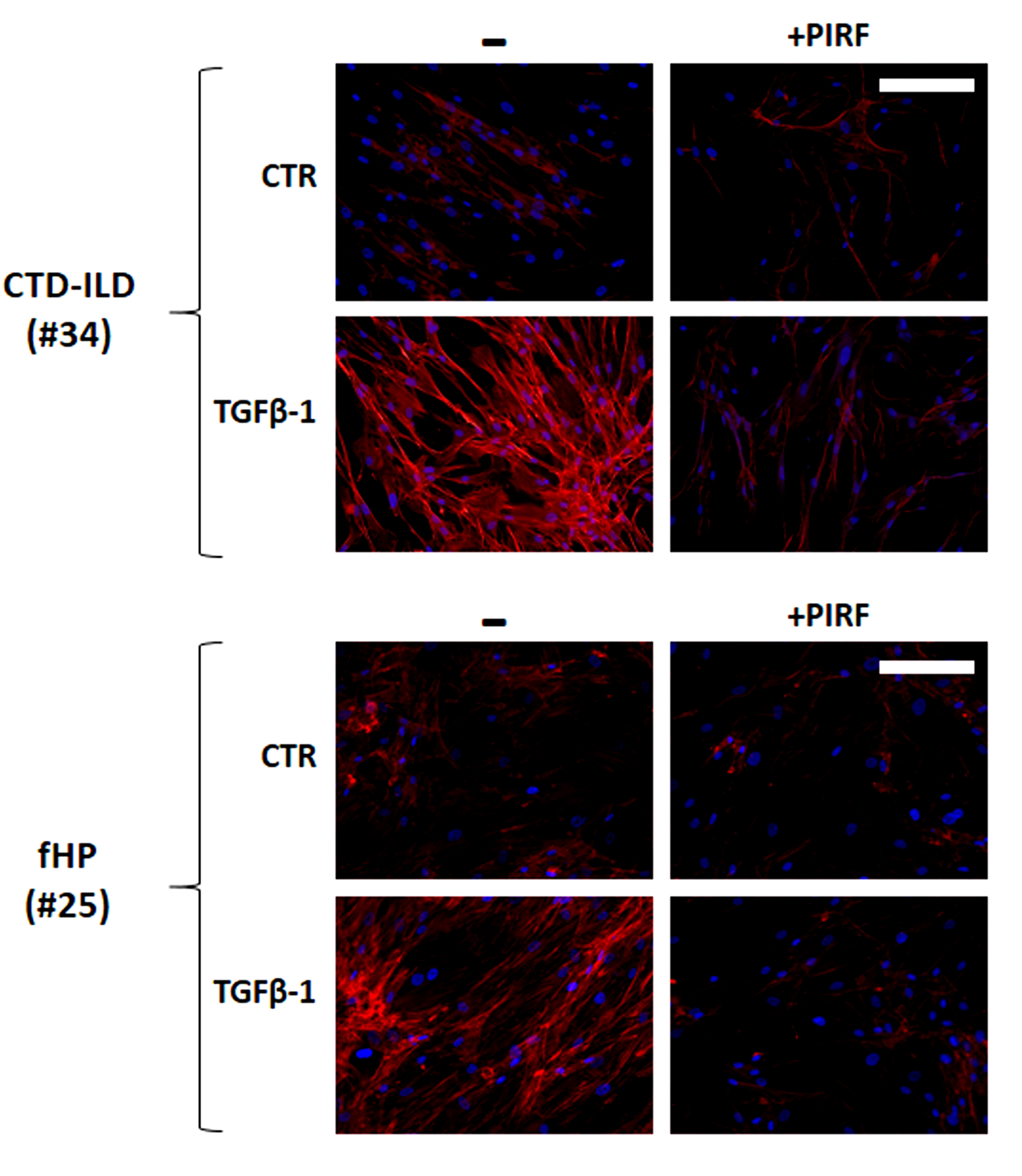

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of F-actin expression in fibroblasts derived from two

Pirfenidone-treated or -untreated ILD patients. Pirfenidone consistently reduced

the expression of F-actin fiber fluorescence in fibroblasts derived from two ILD

patients with/without TGF

The effect of pirfenidone on migration of ILD-fibroblasts was further evaluated

by the use of a wound scratch assay [18] thus measuring fibroblasts polarizing

and migrating in the wound space, with and without Pirfenidone treatment. Fig. 6A

shows the migration of fibroblasts from one representative case of 5 tested

following the stimulation with TGF

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Determination of the migratory capacity of ILD-fibroblasts in a

2D system through a wound scratch test assay. (A) The migratory capacity of

ILD-fibroblasts induced by TGF

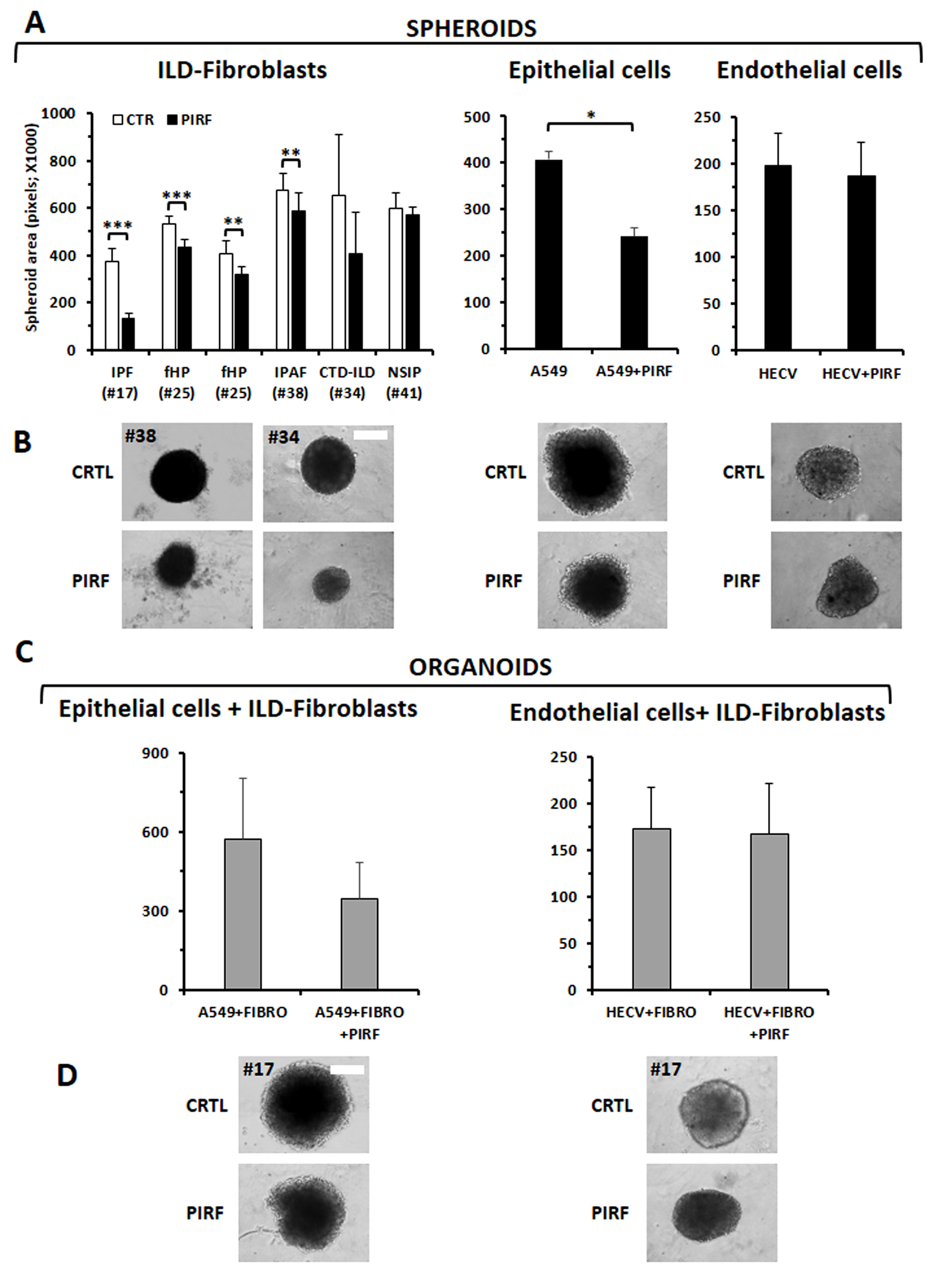

We next assessed the cytotoxic response to Pirfenidone of ILD-fibroblasts in 3D cultures. We took advantage of ultra-low attachment 96 U-bottom well plates to establish spheroids (only ILD-fibroblasts) or organoids (epithelial or endothelial cells + ILD-fibroblasts) and to further determine the activity of Pirfenidone. Fig. 7A,B shows that the formation of spheroids of ILD-fibroblasts was inhibited after Pirfenidone treatment (300 µg/mL) for 72 h with the exception of fibroblasts derived from one NSIP case (#41). A range of inhibition of 32% was detected among the responsive cases, with a more evident inhibition value for fibroblasts derived from the IPF case #17 (65%). Pirfenidone was also active in spheroids established with the epithelial adenocarcinoma A549 cells (41% of inhibition) but not with the endothelial cell line HECV (Fig. 7A,B). We then determined Pirfenidone cytotoxicity in a model of organoids composed of fibroblasts and A549 or HECV cells together: Pirfenidone inhibited the growth of A549+fibroblasts organoids (mean of 3 different added fibroblasts tested: 40% of inhibition), while a very weak effect was detectable for organoids formed by the endothelial HECV cells plus ILD-fibroblasts (Fig. 7C,D). It can be of further interest to note that the response behavior of the cells cultured in 2D was similar to cells cultured in 3D models (Supplementary Fig. 2). Ineffectiveness of the pirfenidone treatment on fibroblasts from the NSIP patient #41 was also confirmed, although a weak anti-proliferative effect (23%) was detectable when Pirfenidone was added at the concentration of 450 µg/mL and fibroblasts were tested in the 2 model, as described before.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Evaluation of the Pirfenidone activity on ILD-fibroblasts, or

epithelial (A549) or endothelial (HECV) cells, in a 3D model of in vitro

growth. (A) Spheroids composed of fibroblasts derived from different ILD

patients, or A549 or HECV cell lines, were tested with Pirfenidone (300

µg/mL): pirfenidone significantly inhibited proliferation of

ILD-fibroblasts with the exception of the NSIP case. The epithelial cell line

A549 resulted inhibited but not the endothelial cell line HECV. (B) Images depict

representative spheroids for each sample type. The white bar corresponds to 25

µm. (C) Organoids composed by A549 or HECV cells and ILD-fibroblasts were

treated with pirfenidone (300 µg/mL): the drug resulted effective as a

trend, although without statistical significance, for A549 cells+ILD-fibroblasts

(3 cases assessed) but not for HECV cells+ILD-fibroblasts (2 cases assessed).

Histograms values are the mean

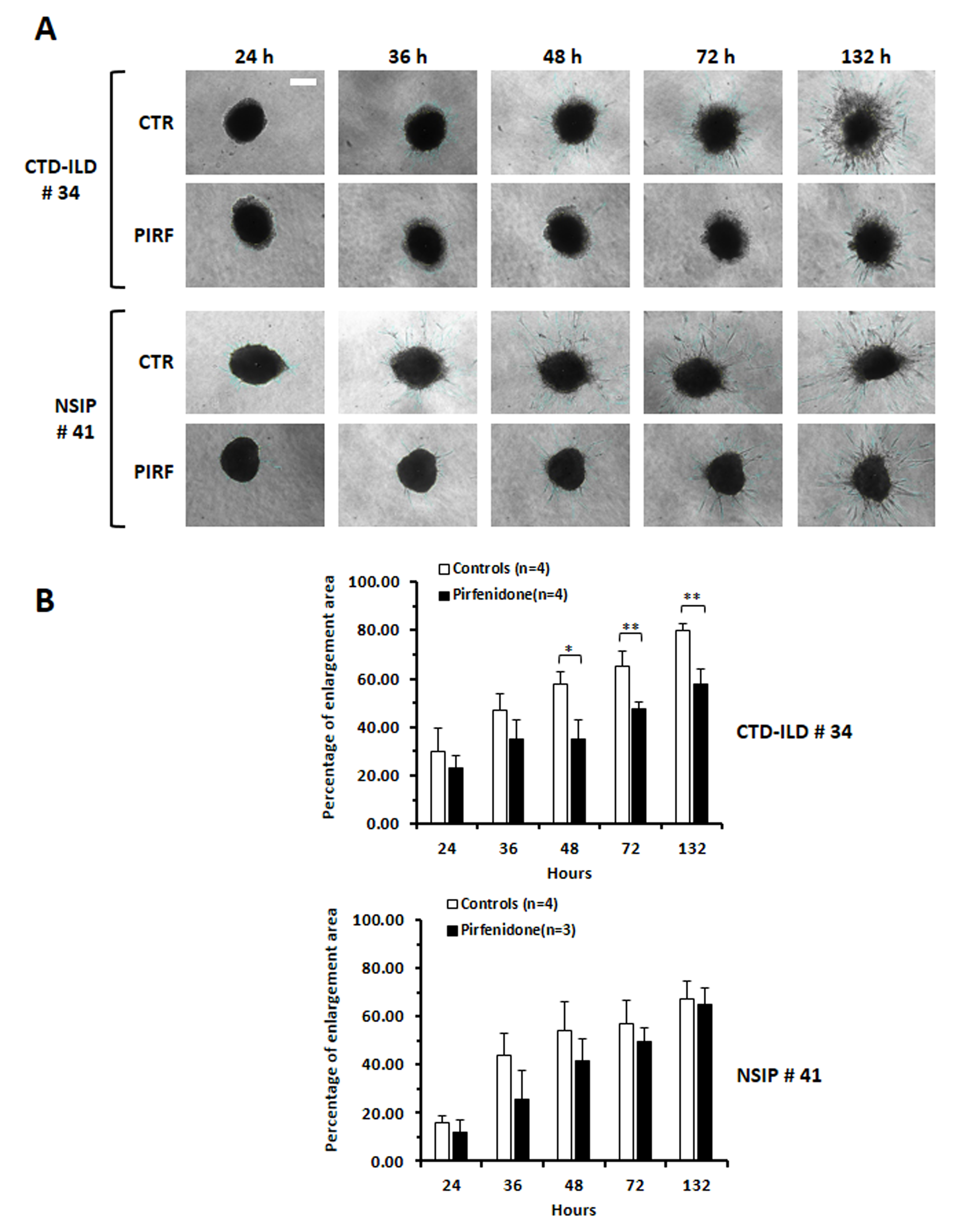

Spheroids derived as above described were further tested for cell invasiveness. We evaluated the migratory mobility of the cells by determining the enlargement of the area of fibroblast migration with time and treatment as a percentage of the total occupied area (Fig. 8; see also Supplementary Fig. 3). Cell spreading, well evident already from 36–48 h, was significantly reduced by Pirfenidone treatment, as depicted in Fig. 8A,B, particularly in fibroblasts derived from the one CTD-ILD case tested (#34).

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Evaluation of the efficacy of Pirfenidone treatment on

invasiveness of ILD-fibroblasts grown in 3D. (A) The invasiveness of

ILD-fibroblasts composing the spheroids resulted inhibited following pirfenidone

treatment (300 ug/mL) at different time points (24, 36, 48, 72 and 132 h). Images

are representative of fibroblasts from two ILD patients. The white bar

corresponds to 25 µm. (B) Histograms depict the mean

Different to surgical lung biopsy BAL is a minimally invasive procedure. In clinical practice its application represents a valuable tool to refine the differential diagnosis of ILD, through the determination of the immune cell counts [19]. Since BAL provides direct access to the alveolar and bronchial epithelium, as well as to the surrounding microenvironment, studies on its composition, both in terms of soluble factors or either cells, might shed new light on the multiple pathogenetic processes taking place in progressive pulmonary fibrosis. The culture and expansion of cells involved in pulmonary fibrosis can be therefore useful to exploit novel in vitro models to better define the complex interactions among different lung cell subtypes and even for personalized medicine to assess responses to specific therapies [20]. We have described here the possibility of deriving fibroblasts/myofibroblasts from the BAL of various ILD patients. Although it is clear that the cells recovery from tissue biopsy is certainly easier and more productive than from BAL fluids, we would like to highlight that the culture-protocol that we have described appears quite feasible. Apart from potential handling contaminations, which could be reduced by the concomitant addition of a proper antibiotic mix to the lavage fluid samples, the procedures are simple, cost-effective and devoid of any ethical concerns.

Looking at morphological and immunophenotypic features of fibroblasts derived

from ILD-patients, versus normal controls, we could observe that those derived

from ILD-patients showed typical characteristics of differentiation toward

myofibroblasts, such as higher collagen I or

The expression of the FGF2 receptor was also higher in fibroblasts derived from

ILD patients than in those from normal controls, and we could also demonstrate a

slight proliferation to FGF2. Indeed, in our protocol we used to add a

sub-optimal concentration of FGF2 to the cultures to better expand fibroblasts.

However, conflicting results have been reported about the role of FGF2 in driving

fibroblasts to myofibroblasts differentiation, as well as in the progression of

the fibrotic process [22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. Apparently FGF2 induces fibroblast

dedifferentiation, with subsequent reduction of collagen and ECM production, but,

at the same time, stimulates their proliferation. We have, however, previously

demonstrated that, after FGF2 treatment, the observed down-modulation of collagen

I and

Currently two antifibrotic drugs, Nintedanib and Pirfenidone are approved for

the treatment of IPF. While the use of Nintedanib has recently been approved also

for non-IPF fibrotic ILD, the efficacy of Pirfenidone in these patients is still

debated and needs to be fully established [28]. Nintedanib is a receptor tyrosine

kinase inhibitor of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-, vascular

endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)- and fibroblast growth factor receptor

(FGFR), that critically regulate myofibroblast transformation and collagen

production under fibrotic conditions [29]. The direct targets of Pirfenidone are

still unknown, however it has been previously demonstrated that its anti-fibrotic

property depends on the inhibition of production of various pro-fibrotic

cytokines and growth factors, such as TGF-

By assessing the activity of Pirfenidone on proliferation and migration of fibroblasts/myofibroblasts derived from different ILD-patients we detected a discrete inhibition for those from IPF patients as well as for those from non-IPF ILD, except for one case diagnosed as NSIP, not presenting pulmonary fibrosis (#41). The effectiveness of Pirfenidone was dose-dependent, and resulted particularly evident at the dose of 300–450 µg/mL, in line with previous studies [31]. NSIP-derived fibroblasts (patient #41), still unresponsive at the dose of 300 µg/mL, started to show a response, albeit weak (23%), when treated with 450 µg/mL of Pirfenidone. The observation that these fibroblasts appear more resistant to Pirfenidone treatment might reflect differences in their phenotype. Potential discriminative features among fibroblasts derived from IPF and NSIP patients have been addressed in a few previous studies. Miki H. and co-authors [32] reported a greater contractility of fibroblasts derived from lung biopsy of IPF/UIP than NSIP patients: this feature appeared in relation with a higher Fibronectin (FN-EDA) content. Barbara Orzechowska and collaborators [33], further exploring the impact of substrate elasticity on the properties of cell lines derived from IPF, NSIP or a healthy subject, demonstrated that fibroblasts derived from the two disorders can be discriminated on the basis of their physical and chemical properties. Gene expression profiling of explanted lung from patients with IPF or NSIP further highlighted that in the latter the genes enriched were related to immune reactions, such as T cell response or leukocytes recruitment to the lung, while in IPF they were related to senescence, myofibroblasts differentiation and collagen deposition [34]. Of note, the BAL of patient #41 was characterized by a very high percentage of lymphocytes and a low number of monocytes/macrophages, different to most of the other cases (Supplementary Table 1), further suggesting a possible link to autoimmune reaction.

We have further demonstrated that Pirfenidone reduced the expression of F-actin stress fiber in fibroblasts derived from various ILD [2]. The multiple effects of Pirfenidone were clearly evident on cells cultured as monolayers, but also on spheroids or organoids, which possibly better mimick the lung tissue 3D in vitro. Since the same trends and effects were displayed among the exact same types of ILD both in the monolayers and in the spheroid/organoid cultures (Supplementary Fig. 2), these close mirroring results, between 2D- and 3D-culture systems, may suggest that those micromass cultures, requiring a much lower number of cells, could easily substitute larger, longer and possibly more demanding traditional monolayer-based approaches. Although the number of samples that we have tested here is too low, thus deserving to be better explored, these data may suggest the potential translational nature of these models, especially the more physiological 3D one, for preclinical and personalized drug screening.

A limiting point of the present study might however be the missing proof that ILD-derived fibroblasts really represent those involved in the fibrotic process. Although we cannot state that the BAL derived fibroblasts are directly representative of the ones expanded during fibrosis, or either located within the fibroblastic foci, it might be conceivable to assume that a larger number of fibroblasts may be present in BAL from patients with progressive fibrosis. Therefore, it appears mandatory to characterize ILD-derived fibroblasts, after their expansion, for the expression of typical myofibrotic markers. In addition, in support of a putative correspondence between fibroblasts infiltrating the lung parenchima and those derived from the BAL fluid, was the evidence that a trisomy 10, exhibited as a peculiar feature by fibroblasts (SCI13D) obtained from an fHP patients (#25), was also found in fibroblasts infiltrating the lung tissue of the cryobioptic specimen, as we previously described [2]. Only a limited number of studies have to date compared fibroblasts isolated from BAL fluids with those derived from tissue, probably due to the difficulty of obtaining BAL and bioptic-tissue from the same patients. In the future further studies might bridge this gap: more sophisticated techniques, matching the two sample sources and coupled to omics-analysis, could clarify the respective origin, intrinsic nature and derivation of those fibroblasts. It is, however, also true that a certain heterogeneity may be present among fibroblasts involved in fibrosis, possibly related to their mesenchymal origin and their plasticity [35].

We are aware that, although representative of the composite family of ILD disease, data samples described here remain limited and need to be implemented to provide sufficient ground for possible discrimination among the different ILD subtypes. Moreover, our 3D organotypic co-culture system represents just an early step in lung modeling, reflecting more cell-to-cell interaction rather than fully mimicking tissue structure, suggesting however that it is nonetheless worth of future exploration and deeper understanding.

Collectively the data described here, as well as those previously reported from other Authors [36, 37], have demonstrated that recovering ILD-BAL fluids represents a valuable and useful tool not only for diagnostic purposes but also for a variety of research investigations. As summarized in our experimental scheme described in Fig. 9, ILD-BAL, other than providing a potential source of cells, such as fibroblasts/myofibroblasts, fibrocytes or even epithelial cells, it may also reveal cytokines/growth factors potentially involved in the fibrotic process. Clarification of the role played by exosomes present within the BAL, with their cargo, has recently further emerged as a novel manner to study the intimate cross-talk among different cell subpopulations of the lung, as well as to identify biomarkers potentially discriminating different ILD [38]. In addition, since IPF patients show a susceptibility developing lung cancer, these studies might also reveal their relationships. To this regard it has been for example reported that exosomes released by IPF-senescent fibroblasts influence tumor progression by activating the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway [39]. Based on the overall data described above, we therefore suggest that the use of a small volume of BAL and its biobanking, as a source of cells and soluble factors from a large number of ILD-patients, can be taken into great consideration to develop in vitro models of pulmonary fibrosis, trying to reveal novel insights in the pathogenetic process.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Representation of the utility of bronchoalveolar lavage in research. Summary of the different passages used to derive fibroblasts from the bronchoalveolar lavage of ILD-patients and to characterize them phenotypically and functionally. The present figure was created using freely available cartoons and personal unpublished data using Microsoft Power Point software.

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conceptualization, writing and editing: DdT, PG; Clinical assessment: EB, MG, FC and FM; Lab experiments: DdT, PG, MB, PA; Supervisioning: DdT, MG, EB, FM, FC. All authors have read and agreed with the final version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responbility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript.

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki; all procedures were also performed according to the standard Good Clinical Practices, following the national current rules and regulations, and the study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genova, Italy (protocol code ILDFIBRO020, n. of Register CER Liguria: 523/2020 DB id 10931). Within the study, all biological samples were anonymized prior to processing. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Not applicable.

5X1000 2022 C809A (E.B.); Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente 2022-2024).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL38726.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.