1 Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Genetics, University of North Texas Health Science Center, Fort Worth, TX 76107, USA

2 Department of Medicine, Section of Hematology and Oncology, Tulane University School of Medicine, Tulane Cancer Center, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA

3 Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine, University of North Texas Health Science Center, Fort Worth, TX 76107, USA

4 Tulane Cancer Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA

Abstract

Adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) have been extensively investigated for regeneration and tissue engineering applications owing to their inherent regenerative ability. However, the effects of various species and depot-specific extraction sites on ASC differentiation and renewal capacity have yet to be explored thoroughly, limiting the clinical use of ASCs. Despite promising clinical results, ASCs are also associated with poor disease outcomes, specifically in the context of breast cancer and obesity. Only when ASC-driven obesity and breast cancer are understood separately will the connection between the two diseases and the ASC-associated effects therein be fully established. Therefore, this review aimed to assess the behavioral differences of ASCs from various large mammalian species and human-derived anatomical niches. This review analyzes ASC migration, the role of ASCs in breast cancer progression and immune modulation, and breast cancer-driven ASC dysfunction to further the understanding of ASCs for future clinical applications.

Keywords

- stem cell

- adipose tissue

- breast cancer

- obesity

- inflammation

- metastasis

Adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) are multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) located throughout adipose, a tissue type found in various anatomical depots [1]. Due to their ability to differentiate into any cell of mesodermal origin, ASCs represent ideal candidates for tissue regeneration and therapeutics [2]. ASCs are mobilized to sites of disease or injury via chemokines and cytokines, which can play a role in their regenerative abilities [3]. ASCs from various depots and species [4] differ greatly concerning their function, even in healthy individuals. Therefore, determining differences in site-specific ASCs is crucial to developing ASC applications in the clinical setting.

Breast cancer is one of the most frequently diagnosed malignancies in the world, with mortalities expected to surpass one million annually by 2040 [5]. ASCs have been shown to promote breast cancer by regulating cell migration and proliferation [6]. As a main component of breast tissue, adipose is an integral part of the breast tumor microenvironment (TME). ASCs are a component of adipose, thus key mediators of breast cancer progression [7]. The risk of developing breast cancer is increased by elevated body mass index (BMI) during obesity [8]. ASC biology is significantly altered in obese conditions, causing dysregulation to biological protein expression, and ultimately allowing breast cancer progression by mediating processes like migration, which can lead to metastasis [9]. Therefore, obesity often has been correlated with worse prognoses and poorer outcomes [7, 10]. As such, research has focused on investigating the biological determinants of differences between ASCs from obese and lean patients in the context of disease.

This review evaluates ASCs from various mammalian species and human anatomical adipose depots to describe differences in ASC characterization and differentiation capacity of these cells. This review will additionally discuss the consequences of ASC mobilization for the progression of breast cancer and obesity. To address this, we will assess the current understanding of the role of ASCs in obesity and breast cancer separately and in combination. Then, the review will assess how ASCs are currently being studied for use in therapies, and the challenges therein. A better understanding of the role of ASCs in disease pathogenesis will enable novel therapeutics to follow.

For therapeutic purposes, ASCs are typically isolated from human adipose tissue. However, they can be obtained from the adipose of other mammals, offering a wealth of potential for the preclinical study of ASCs [11]. Here we will review ASC heterogeneity among large mammalian species such as cattle, pigs, and dogs. It has been noted that large mammals more closely reflect human physiology than rodents, despite the increased ethical concerns of using these more intelligent animals in research [12]. If ASCs from large mammals prove useful, they could significantly advance our understanding and treatment of diseases, offering new hope for patients and researchers alike.

Most ASCs sourced from mammalian species are evaluated using the same criteria for characterization and differentiation capacity as those derived from humans. Most published studies have utilized ASCs from large, land mammals. Interestingly, fat extraction sites are inconsistent between species and even among research of the same species (Table 1, Ref. [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24]). In two independent studies of ovine-derived ASCs, cells were extracted from the embryonic tail fat [13] or omental fat tissues [14]. Despite the difference in depot site, both cell types undergo adipogenesis and osteogenesis [13, 14]. The embryo fat-derived, and omental fat-derived ASCs were capable of myogenesis [13] and chondrogenesis [14], respectively, indicating differences in differentiation capacity. Neither study induced chondrogenesis and myogenesis, but the ASCs likely become chondrocytes and myocytes, despite the extraction site. However, more research needs to be done to confirm this assumption.

| Species | Depot | Positive Markers | Negative Markers | Differentiation Potential | References | |||

| Adipocyte | Osteoblast | Chondrocyte | Myocyte | |||||

| Ovine | Embryonic Tail | - | - | - | [13] | |||

| Omental | CD73, CD90 | CD34, CD45 | - | [14] | ||||

| Bovine | Abdominal | CD44, CD73 | CD34, CD45 | - | - | [16] | ||

| Tailhead | CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD166 | CD34, CD45 | - | - | [15] | |||

| Porcine | Abdominal | CD29, CD44, CD90, CD105 | CD31, CD45, CD14 | - | - | [17, 18] | ||

| Dorsal | CD29, CD44, CD90, CD105, MHC I | CD14, CD31, CD45, CD4a, MHC II | - | x | [18, 19, 20] | |||

| Canine | Infrapatellar | CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105 | CD45, MHC II | - | [21] | |||

| Perirenal | CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105 | CD45, MHC II | - | [21] | ||||

| Inguinal | CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105 | CD45, MHC II | - | [21] | ||||

| Omental | CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105 | CD45, MHC II | - | [21] | ||||

| Abdominal | CD44, CD90 | CD34 | - | [22] | ||||

| Non-human primate | Abdominal | CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105 | CD11b, CD19, CD34, CD45 | - | [23, 24] | |||

| Mesenteric | CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105 | CD11b, CD19, CD34, CD45 | - | [24] | ||||

x, no differentiation;

In bovine research, extraction sites are not standardized. However, adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation potential is maintained in ASCs from both the tailhead region [15] and the abdomen [16]. Notably, cell surface marker expression is more heavily contested. Ishida et al. [4] included CD26, CD54, and CD146 as surface markers for detecting ASCs, but other bovine-derived ASCs were not evaluated using the same standards [15, 16], complicating comparison among studies. While positive and negative surface markers varied, CD44 and CD73 positivity remained required for ASC identification in both studies [15, 16]. Since previous literature is inconsistent regarding positive and negative selection markers, the resulting studies reviewed herein are also inconsistent regarding selectivity markers. This phenomenon eludes to the need for protocol standardization in ASC research.

Similarly to ASCs extracted from ovine and bovine models, porcine models are also inconsistent regarding fat depot extraction sites. However, the criteria for ASC detection were consistent, with CD29, CD44, CD90, and CD105 as positive markers, and CD14, CD31, and CD45 as negative markers [17, 18, 19, 20]. Abdominal and dorsal fat-derived ASCs could undergo adipogenesis and osteogenesis [17, 18, 19]. Dorsal fat-derived ASCs can differentiate into chondrocytes [18, 19, 20], but not myocytes [18], despite expressing muscle-specific genes in the presence of fully differentiated myotubes [18]. Moreover, differentiation capacity and resulting transcriptomic profiles are heavily reliant upon the breed of the porcine model [25], indicating a need for uniformity across studies.

Consistent with other non-human mammalian ASCs, canine-derived ASCs can undergo adipogenesis [21, 22, 26], osteogenesis [21, 22, 26], and chondrogenesis [22, 26]. However, Rashid et al. [21] demonstrated that the extraction site of ASCs affects differentiation capacity. While ASCs from the canine infrapatellar fat pad, perirenal, inguinal, and omental regions can differentiate into osteocytes and adipocytes as evidenced by alizarin red and Oil Red O staining, respectively, omental fat-derived ASCs showed significantly increased Oil Red O staining compared to undifferentiated controls than ASCs from other depots. However, omental-derived ASCs are larger than infrapatellar fat pad-derived ASCs, so they may be able to form larger lipid droplets, become larger adipocytes, and therefore retain more Oil Red O stain [21]. Also, this difference may be due to the proximity of omental fat to the abdominal region compared to the other derivation sites. Similarly, omental-derived ASCs showed more significant alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity in cells undergoing osteogenesis compared to other depot-derived ASCs. However, although ALP activity was significantly elevated in all differentiated cells compared to the undifferentiated controls [21]. Interestingly, the proliferation of ASCs from the infrapatellar fat pad of canines was higher than that of cells from other sites [21].

Non-human primate-derived ASCs can undergo adipogenic [23, 24, 27, 28, 29], osteogenic [23, 24, 28, 29], and chondrogenic [23, 24, 28] differentiation, regardless of isolation from abdominal [23] or mesenteric [24] depot sites. Further, another study showed the differentiation of ASCs into neural cells [29]. The span of in vitro ASC differentiation experiments is seven to 21 days; however, differentiation times differed amongst lineages between studies, making comparison across experiments difficult. Non-human primate adipogenesis studies were carried out for seven [24] or 21 [23] days, while chondrogenesis and osteogenesis studies were consistently 21 days [23, 24]. Although these discrepancies in differentiation times are interesting, the International Federation for Adipose Therapeutics and Science (IFATS) does not recommend a specific time frame for differentiation of ASCs [30], leaving interpretation up to the investigators.

All mammalian-derived ASCs reviewed were capable of adipogenesis and osteogenesis, and all cells induced to undergo chondrogenesis could do so. However, in a study by Milner et al. [18], porcine ASCs were incapable of myogenesis. In this study, porcine ASCs were differentiated using a medium that caused murine myoblasts to differentiate into myotubes [18]. Therefore, based on the intrinsic differences that may be present between species, it is probable that the myogenesis-inducing medium will also vary from species to species. Thus, more studies need to be performed to confirm the ability of porcine-derived ASCs to undergo myogenesis. Otherwise, ASC protocols, including differences in depot sites and positive and negative selection markers, vary among species, leading to conflicting results. The discrepancies in surface marker expression may be due to expression differences amongst various species, leading researchers to identify other positive and negative markers [31]. A standardized approach to ASC research is needed to harness the translational potential of mammal-derived ASCs fully.

While large mammal-derived ASCs are crucial for better understanding the role of ASCs in preclinical models, human-derived ASCs are the most critical consideration for future therapeutic applications. However, adipose from different anatomical locations exhibits unique biological and physiological properties, indicating the need to review the behaviors of ASCs from various human depots. For example, fat accumulation in an android or truncal distribution is associated with obesity-related cardiometabolic diseases, whereas gynoid peripheral fat in the gluteal and femoral regions is metabolically protective [32]. Subcutaneous white adipose tissue (WAT) is the body’s predominant adipose that stores and releases energy through lipids. Compared to visceral adipose, subcutaneous adipose comprises a more significant percentage of ASCs [33]. Mounting interest in ASCs has emerged due to their utility in cell-assisted lipotransfer and bone regeneration and their role in tumor-promoting interactions with cancer cells, especially in the breast. Here, we discuss human adipose progenitor cells which demonstrate heterogeneity in function depending on the subcutaneous anatomical depot from which they are derived (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. ASCs from various human-derived depots. Adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) from the buccal fat pad, breast, flank, abdominal, gluteal, and thigh depots have varying differentiation capacities. These cells differ in proliferative abilities and gene and protein expression of various markers. Created with BioRender.com.

Human ASCs have been isolated from subcutaneous depots, including the abdomen, gluteal region, breast, arm, thigh, flank, back, and buccal fat pads, and cultured in vitro. The anatomical niche ASCs are derived from can dictate lineage differentiation potential into adipocytes, osteocytes, or chondrocytes. In comparison to ASCs isolated from the abdomen (abASCs), breast-derived ASCs (brASCs), preferentially differentiate from the osteogenic lineage, suggesting that brASCs could be more suitable for bone regeneration applications. On the other hand, abASCs are preferred to brASCs for adipocyte generation in cell-assisted fat grafting for breast reconstruction. These findings significantly impact the selection of ASCs for specific regenerative medicine applications [34].

For cell-assisted fat grafting, ASCs with the highest adipogenic potential are desired to supplement fat growth in the engrafted areas [34]. Therefore, determining differentiation capacity differences among ASC depots is crucial to selecting the most effective ASC type. Among flank-, arm-, abdomen-, and thigh-derived ASCs, thigh-derived ASCs (thASCs) exhibited the highest adipogenic potential out of the four depots [35]. Similarly, a study comparing thASCs and abASCs from age-, BMI-, and passage-matched tissues showed that thASCs expressed significantly higher gene and protein expression of mature adipocyte markers than abASCs after one week of adipogenic differentiation [36], confirming the results of the previous study. Thus, thigh adipose could be superior to abdominal adipose for fat grafting. However, ASCs were not obtained from all depots in all patients, which may limit the conclusions drawn from the depot-specific differences in this study [35]. Conversely, flank ASCs (flaASCs) exhibited the lowest gene expression of mature adipocyte markers adipocyte protein 2 (AP2) and lipoprotein lipase (LPL) after one week of in vitro adipogenic differentiation compared to the abdominal-derived ASC controls [35]. When comparing abASCs and gluteal ASCs (gluASCs), gluASCs exhibited enhanced adipogenesis compared to abASCs, as evidenced by Sudan staining. However, mature adipocyte gene marker fatty acid binding protein 4, also known as AP2, was not significantly different between the depots after 28 days of adipogenic differentiation [37]. Gluteal adipose is anatomically close to the thigh, which may explain its functional similarities and enhanced adipogenesis compared to abASCs, which are closer to visceral organs.

Due to their osteogenic differentiation potential, ASCs represent promising tools in bone regeneration procedures correcting periodontal defects and facial reconstruction. ASCs with the highest osteogenic differentiation capacity are ideal for such applications. The buccal fat pad, a small fat pocket in the cheek, yields ASCs (bfpASCs) with enhanced osteogenic differentiation compared to abASCs, as demonstrated by the increased gene expression of ALP and collagen I after two weeks of in vitro osteogenic differentiation. BfpASCs and abASCs had similar abilities to adhere to periodontal engraftment resorbable materials. BfpASCs displayed enhanced osteogenic stimulation in response to amelogenin, a porcine enamel derivative used for periodontal defect corrections, as bfpASCs exhibited upregulation of ALP and collagen I compared to abASCs. The difference in response of bfpASCs to amelogenin is potentially due to the buccal fat pad niche location, which is closer to dental enamel, and abdominal fat is located distal to dental enamel [38]. However, bfpASCs and abASCs displayed similar adipogenic differentiation potential, growth kinetics, and proliferation in response to human sera, suggesting that the utility of bfpASCs is most relevant in bone regeneration, especially in periodontal and facial reconstruction [38]. However, Broccaioli et al. [38] did not delve into the detailed mechanisms behind the different behaviors exhibited by abASCs and bfpASCs.

Furthermore, in a comparison of flank-, arm-, abdomen-, and thigh-derived ASCs, flaASCs and thASCs had the highest osteogenic potential evidenced by alizarin red and ALP staining, as well as gene expression of mature osteoblast markers. Gene expression of bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) was highest in flaASCs and thASCs, suggesting that the bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs), which stimulate osteogenesis, could be responsible for the increased differentiation in these depots [35]. Compared to abASCs, gluASCs have higher osteogenic potential after 28 days of osteogenic differentiation. GluASCs showed significant upregulation of ALP, but no depot difference was seen in other gene markers of mature osteoblasts [37]. The differences in differentiation capacity could be due to niche-specific differences in levels of osteogenic precursors present in adipose to alterations in signaling pathways like the BMP pathway.

In mouse models, ASCs have enhanced survival compared to adipocytes under hypoxic conditions. This suggests supplementing ASCs in fat grafting procedures through cell-assisted lipotransfer may prevent hypoxia and necrosis in the newly grafted fat. Enhanced survival may result from ASCs being needed to initiate tissue repair post-damage [39]. ThASCs exhibit higher angiogenic potential than abASCs, making them a potentially preferred candidate for cell-assisted fat grafting over abASCs [36]. After three weeks of in vitro induced endothelial differentiation, thASCs expressed significantly higher angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway gene and protein markers, as well as endothelial cell marker CD31. When endothelially differentiated thASCs and abASCs were seeded on Matrigel, thASCs exhibited significantly greater tube formation, with extensive tubes and junctions, evidenced by phase-contrast microscopy [36]. It is postulated that the thigh adipose microenvironment is primed by exercise compared to the abdominal adipose environment, and the biomechanical fluid shear stress from exercise induces differentiation to the endothelial lineage [40]. In shear stress conditions, murine progenitor C3H/101/2 cells express greater levels of von Willebrand Factor (vWF), a protein expressed in endothelial cells. Similarly to the previous study, shear stress also induces tube formation on Matrigel. Shear stress induces upregulation of VEGF and VEGFR-1 mRNA expression, indicating a potential mechanism by which these cells differentiate into endothelial cells during mechanical stress [40]. These observations may contribute to thASC predisposition to angiogenesis over abASCs.

When considering the safety and efficacy of cell-assisted fat grafting, it is necessary to consider ASC growth kinetics and self-renewal. BrASCs exhibit a higher self-renewal capacity, as evidenced by significantly increased colony-forming units, suggesting that brASCs may retain an undifferentiated state and thus have enhanced stem cell populations [34]. The growth kinetics of brASCs differ from abASCs, indicating that priming from the original anatomical niche can dictate the long-term growth kinetics of ASCs. BrASC doubling time was progressively faster with each passage, while abASCs had a stable doubling time [34]. Furthermore, in comparing abdomen-, arm-, flank-, and thigh-derived ASCs, flaASCs exhibited the highest proliferation capacity by BrdU incorporation [35]. Further investigation revealed 2–4-fold higher fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) gene expression in flaASCs compared to abASCs, identifying the FGF2 pathway as a potential mechanism by which flaASC proliferation is increased [35]. Meanwhile, in two studies, abASCs exhibited proliferation profiles similar to that of gluASCs [37] and bfpASCs [38]. Additionally, in a study comparing ASCs from the upper abdomen, lower abdomen, flanks, dorsum (dorsal upper back), and thighs, the colony formation capacity (reflecting self-renewal capacity) and doubling times did not differ between depots [41]. These findings underscore a unique cellular growth profile of brASCs compared to ASCs from other adipose depots. Thigh, flank, and arm-derived ASCs had comparable proliferation capacities, but flaASCs were highly proliferative [35]. Therefore, the results of these studies indicate that adipose tissue depot sites can influence the proliferation of ASCs, indicating the importance of a thorough assessment of proliferative abilities before selecting a depot site for ASC extraction for clinical use.

Investigating the effects of ASCs on surrounding cells via secretion of cytokines, growth factors, or exosomes is important for predicting long-term activity in engrafted sites and understanding how ASCs interact with nearby tumors. The effects of abASC and thASC secretomes were evaluated by applying ASC-conditioned media to human fibroblasts. The protein secretome of ASCs from these two depots increased VEGF protein expression compared to the control; however, there was no significant difference in VEGF protein expression between thASCs and abASCs [41]. VEGF is a mediator of wound healing and has been shown to play a role in migration, proliferation, and angiogenesis. No significant difference was found between the migration of fibroblasts treated with media from either abASCs or thASCs, despite both ASC depot secretomes increasing fibroblast migration compared to the control [41]. Therefore, VEGF signaling must play a role in both abASC and thASC migration. This data highlights similarities in thigh and abdominal ASC secretomes and their impact on surrounding fibroblasts, suggesting that both abASCs and thASCs could be equally effective in promoting wound healing and angiogenesis, which could have implications for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

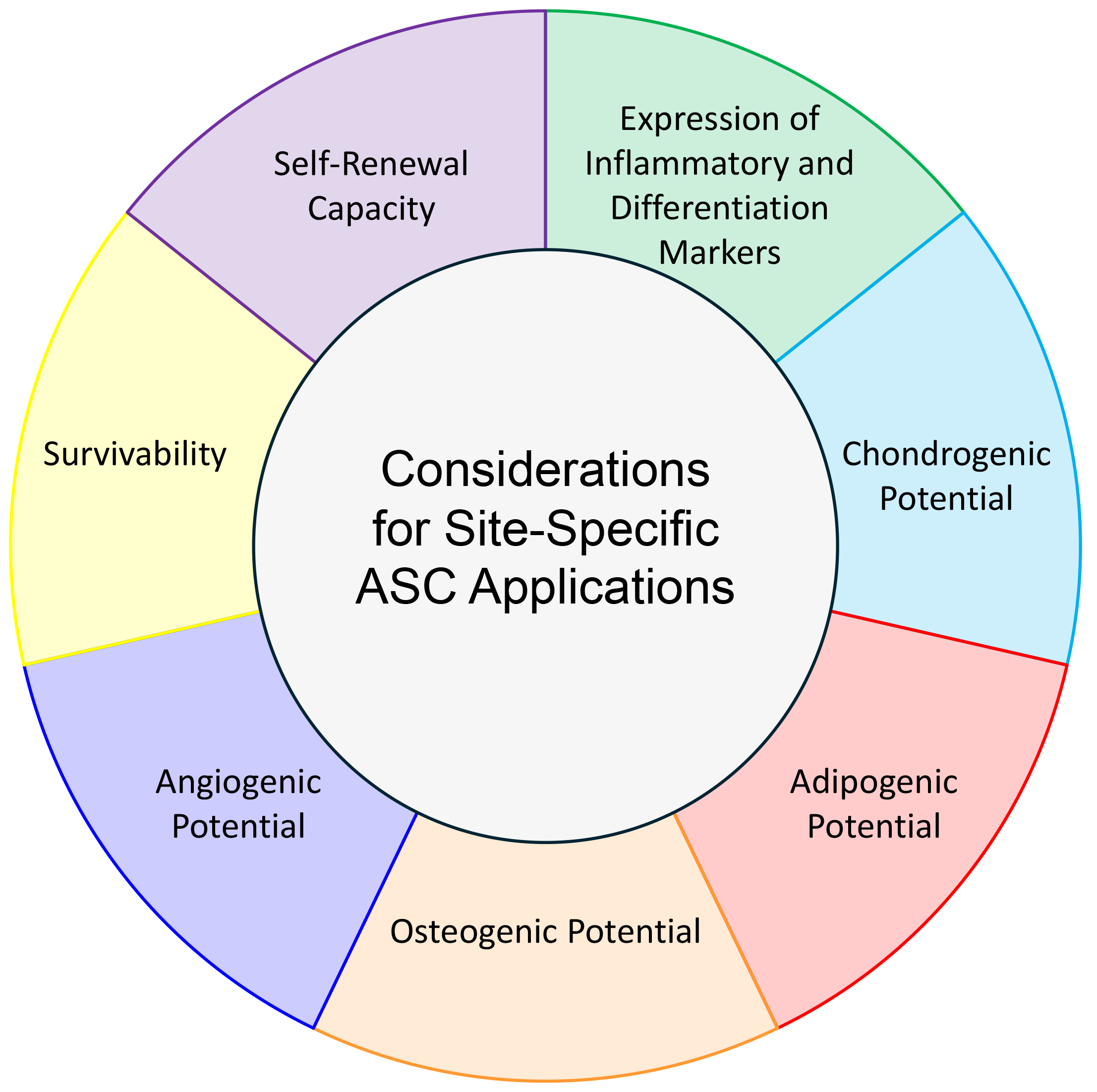

ASCs from different human anatomical niches display various expression profiles, differentiation potentials, and proliferative abilities. To curate the desired effect for therapies, the ASC-derivation site must be considered (Fig. 2). Although the mechanisms behind differentiation, angiogenesis, and proliferation of ASCs are well-characterized [42], there is a lack of detailed discussion of underlying mechanism in several of the articles herein. When these differences between ASCs from each depot are thoroughly characterized, there will be new applications for using stem cells in regenerative medicine.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Considerations for Site-Specific ASC Applications. Differentiation potential, gene expression profile, self-renewal, and survivability must be noted when choosing depot-derivation site of ASCs for a particular clinical application.

Chemokines and cytokines for tissue repair and disease drive mobilization of ASCs. For example, one study revealed that C-C chemokine receptor type 7 (CCR7) drives ASC migration. In ASCs transduced with a CCR7-containing lentivirus, migration to secondary lymph organs increased, and rats could maintain transplants for a longer period, reflecting a positive outcome of ASC migration [43]. This migration is crucial to ASCs’ role in tissue repair, allowing them to reach damaged areas and initiate the repair process. However, C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 1 (CXCL1), a chemokine, drives the migration of obASCs to prostate cancer via C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CXCR1), thereby promoting poorer prostate cancer outcomes that are associated with obesity. In this model, signaling via CXCR1 promotes alpha-smooth muscle actin (

In another paper studying migration of both lean and obese ASCs, monocyte chemoattractant protein -1 (MCP-1) and interleukin 8 (IL-8) induced migration of mouse-derived ASCs from both lean (lnASCs) and obese (obASCs) donors through a Boyden chamber. Interestingly, High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) caused significant migration of obASCs, and stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) caused lnASC migration [46]. However, these results were not exactly paralleled in human studies. In lnASCs from human donors, SDF-1, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-

Age impacts the migration and angiogenic potential of ASCs significantly as well. In ASCs from older patients, migration patterns were diminished compared to ASCs from younger patients [47]. In a study looking at tube formation of ASCs on Matrigel, there was a significant difference in the number of tube branch points between early (less than 20) and late (greater than 20) passage human-derived ASCs that were not stimulated to form tubes, indicating the potential of age to impact angiogenic potential in these cells as well [46].

Lastly, ASC-driven angiogenesis and neovascularization can promote tumor growth, especially in TME priming, potentially making it easier for tumors to receive nutrients from non-neoplastic cells. Hypoxic conditions have been shown to promote ASC regenerative capabilities, thereby inducing angiogenesis [48]. In a study by Kalinina et al. [49], abdominal ASCs from ten female patients were cultured in both hypoxic and normoxic conditions to analyze proteins that may play a role in regeneration. Over 600 proteins were secreted by the ASCs from both groups, of which 100 played pivotal roles in tissue regeneration, wound healing, and vessel formation [49]. In murine ASCs with experimentally upregulated VEGF expression, there was an increase in blood vessel formation in implants compared to control groups. More specifically, there was a significantly greater number of SMA-positive blood vessels present as well. The VEGF-overexpressed ASCs showed upregulation of angiopoietin-1, indicating a potential mechanistic process by which VEGF contributes to angiogenesis in ASCs [50]. Similarly, in a separate experiment in immunodeficient mice, injection with murine preadipocytes showed the formation of vessel plexuses with adipocyte maturation, suggesting interplay between vascular growth factors secreted by adipocytes as well as surrounding endothelial cells, leading to new vessel growth [51]. The potential of ASCs to communicate with cancer cells through growth factors and cytokines, allowing them to migrate to damaged areas, is an intriguing aspect of their role in tumor pathogenesis [6].

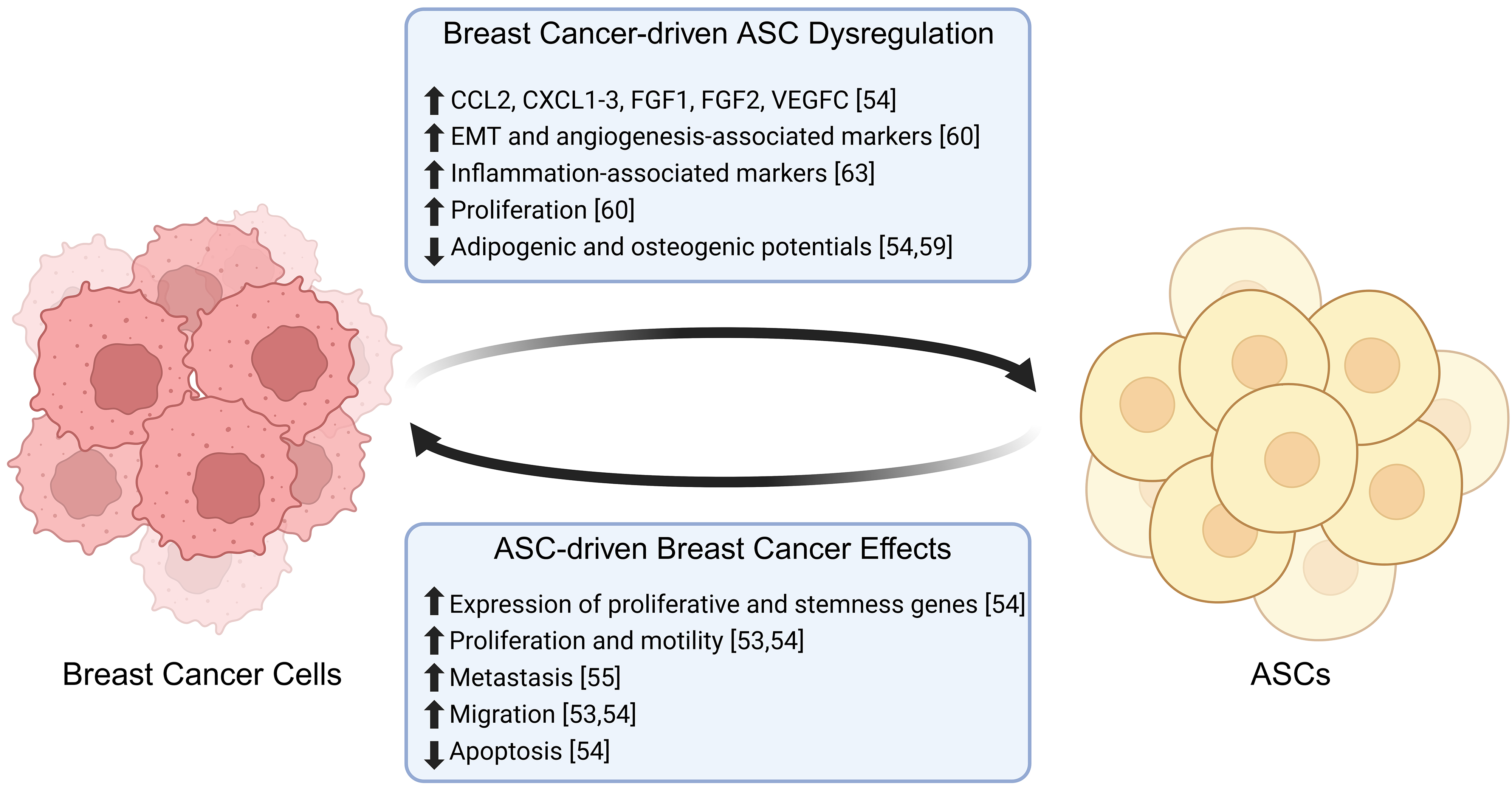

Breast tumors are surrounded by a microenvironment rich in adipose immune cells, stromal cells, and extracellular matrix (ECM), comprising the TME. For breast cancer cells to initiate invasion, they must remodel the TME in favor of invasion and metastasis [52]. Invasion is an early step in the metastatic cascade and is mediated by reciprocal crosstalk between breast cancer cells and the surrounding tissue. ASCs are a core component of the breast TME and participate in this feedback loop through paracrine signaling and direct cell-cell contact with breast cancer cells [53, 54] (Fig. 3). In xenograft models utilizing human breast cancer cell lines in coculture with bone marrow-derived MSCs, rapid secretion of CCL5 by MSCs in the primary tumor promotes metastatic phenotypes. This effect was strong enough that metastatic cells isolated from mouse lungs reinjected in vivo showed no significant difference in tumor volume from reinjected non-metastatic, primary tumor cells that were originally cocultured with CCL5-secreting MSCs [55]. Similarly, brASCs can activate breast cancer cells through the secretion of cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8 [53]. Treatment of human ductal carcinoma cells with IL-6 or IL-8 promotes cell invasion in three-dimensional collagen matrices, and breast cancer cells exposed to conditioned media from normal brASCs have enhanced cell proliferation and motility [53, 54]. Another study observed coculture of ASCs with estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 (MCF-7) breast cancer cells, which resulted in protein upregulation of glutathione S-transferase P1 (GSTP1) and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) in breast cancer cells [9], both of which are upregulated during drug resistance in ER+ cancer cells [56]. Inhibition of CDKN2A resulted in the downregulation of vimentin (VIM) [57], a mesenchymal marker [58], and upregulation of e-cadherin (CDH1) [57], an epithelial marker [58]. These changes suggest that upregulation of CDKN2A in breast cancer may lead to increased epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of breast cancer cells, a crucial step preceding metastasis [57].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Breast cancer and ASC interactions. Adipose-derived stem cells promote the proliferation, migration and metastasis of breast cancer cells, while decreasing the levels of apoptosis. In turn, breast cancer cells promote the proliferation and expression of inflammation-associated markers in ASCs, while decreasing their differentiation potential (🡅 = increased, 🡇 = decreased). Created with BioRender.com.

BrASCs adjacent to the tumor are distinct from those isolated from mammary adipose distal to the tumor, with adjacent brASCs expressing increased expression of pro-tumorigenic cytokines such as C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), CXCL1-3, fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1), FGF2, and vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGFC) [54]. Interestingly, exposure of brASCs to breast cancer-secreted factors and direct contact with breast cancer cells reduces brASC adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation capacities, favoring a dedifferentiated and cancer-associated fibroblast-like (CAF) phenotype [54, 59]. Tumor-adjacent brASCs are more proliferative than those isolated from healthy donors, with increased expression of genes involved in EMT, angiogenesis and matrix remodeling [60]. Breast cancer cells are remodeled by brASCs in the TME, altering drug responses and proliferation. The diameters of spheroids generated from BT474 and MDA-MB-361 cells increase when directly cocultured with brASCs [54]. This effect is enhanced in spheroids cocultured with tumor-adjacent brASCs compared to those with distal brASCs. Direct contact of breast cancer cells with brASCs increases breast cancer cell expression of stem cell factor (SCF), C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5), VEGFA, oncostatin M (OSM), macrophage inhibitory factor (MIF), and osteoprotegerin (OPG), genes associated with cell stemness and proliferation [54]. Interestingly, coculture spheroids treated with drugs tamoxifen and docetaxel acquire therapeutic resistance [54]. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy diminishes the increased proliferation seen in tumor-adjacent brASCs compared to proliferation levels seen in healthy individuals; however, adipogenic differentiation remains lower in brASCs from breast cancer patients compared to healthy donors despite chemotherapy [61]. These studies suggest that breast cancer cells directly affect the ASC transcriptome, which in turn allows brASCs to promote breast cancer cell resistance, proliferation, and pro-EMT expression profiles. All these factors combined may result in breast cancer progression.

Recently, breast cancer cells were observed to engulf brASCs, forming hybrid brASC-cancer cells that promote chemoresistance and metastasis. Hybrid cells, distinguished by the expression of fibroblast activating protein (FAP), are formed preferentially from brASCs secreting CCL2 and cancer cells highly expressing Wnt family member 5A (WNT5A) and IL-6 [62]. The hybrid cell type formed is polyploid and senescent, shown by increased expression of

ASCs, with their potential to alter the immune system, emerge as significant players in the complex landscape of breast cancer progression. ASCs exposed to triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) conditioned media promoted an inflammatory TME through the production of MCP-1 (or CCL2), IL-6, and IL-8. However, ASC-conditioned media did not affect the differentiation of ASCs [63].

The differentiation of ASCs can potentially contribute to immune environment alterations during breast cancer. Early differentiation of ASCs into osteocytes is associated with increases in gene expression of interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, interleukin-12 (IL-12), Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1), interferon-

ASCs can impact breast cancer-associated macrophages as well. Out of a panel of gene markers involved in breast cancer progression, IL1B expression was significantly higher in abASCs compared to brASCs [65]. When ASCs were directly cocultured with macrophages, both brASC and abASC macrophage cocultures increased gene expression of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGFC), serpin family E member 1 (SERPINE1), FGF2, IL1B and IL6 compared to macrophages in monoculture [65]. However, there was no difference in gene expression between the two depots in coculture with macrophages [65]. Aside from higher gene expression of IL1B, these assays demonstrate functional similarity in gene expression and impact on surrounding cells in the breast cancer tumor microenvironment between abASCs and brASCs. suggesting that both abASCs and brASCs could effectively promote angiogenesis and tumor progression, which could have implications for cancer research and potential therapeutic interventions.

Finally, ASCs may alter the immune response by affecting T-cell migration and differentiation. ASCs derived from obese mice show significant upregulation of CCL5 and migration of T cells into adipose tissue compared to ASCs from lean mice, which may contribute to increases in adipose inflammation. Interestingly, this study highlights an intrinsic difference in gene expression between obese-primed and non-obese ASCs in a murine model [66]. Adipose inflammation drives increase in levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF), both of which are known to contribute to the development of breast cancer directly [67]. In direct co-culture with ASCs, CD4+ T cell differentiation is driven toward a T-regulatory phenotype [68], indicating a potentially immune suppressive environment. Similarly, during limb transplant, ASCs coupled with treatment with cyclosporin A, an immune suppressor, resulted in significantly longer transplant survival times compared to limb transplant in the presence of cyclosporin A alone [68]. Therefore, ASC-driven immune suppression is another means of immune modulation that may have further implications in breast cancer, especially in obese patients.

Obesity is the unhealthy distribution of adipose tissue over the human body [69], and is clinically defined by a BMI greater than 30. As an endocrine organ, adipose tissue plays a central role in energy and lipid homeostasis, and its dysregulation during obesity can lead to low-grade chronic inflammation and metabolic alterations. Such dysregulation can lead to metabolic diseases including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic liver disease, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, stroke, and multiple cancer types [70]. Obesity impacts the adipo-niche, including ASCs [71]. During obesity, ASCs release proinflammatory cytokines like TNF and IL-6, adipokines like leptin (LEP) and adiponectin (ADIPOQ), as well as free fatty acids, while generally remodeling the ECM in the adipose tissue microenvironment [72]. These processes impact extracellular signaling pathways like TNF-

Changes to the adipose tissue during obesity alter ASC functional plasticity as well [71, 73]. In a pig model of obesity, ASCs between lean and obese pigs showed no difference in proliferation [73]. However, obASCs showed diminished telomerase activity and significantly increased

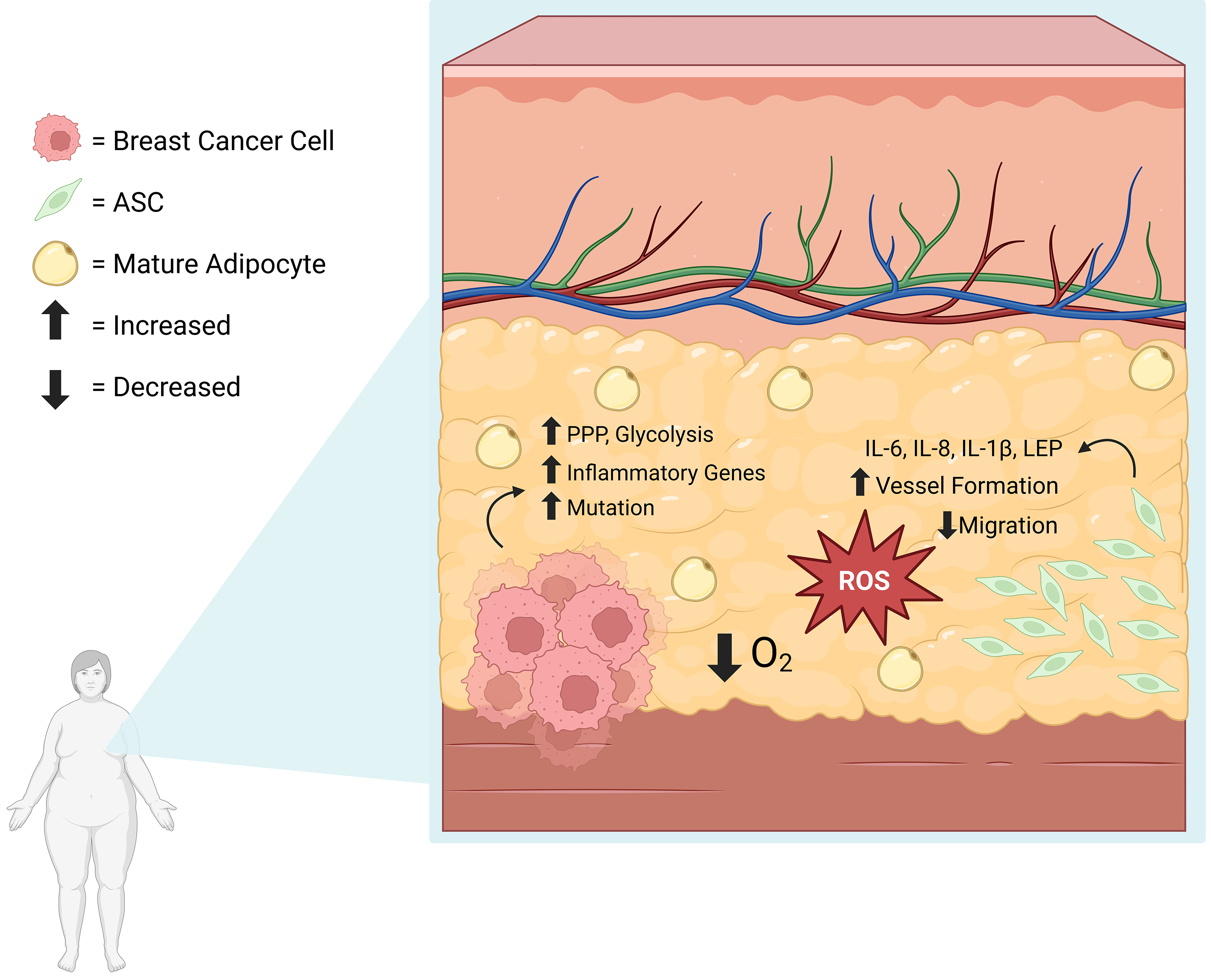

While both obesity and breast cancer independently influence the biology and physiology of ASCs, together they have the potential to act synergistically, leading to more aggressive cancer and a poorer prognosis. This occurs via the interplay between the obASCs and the breast cancer cells. In an obese state, adipose tissue hypertrophy and hyperplasia increase the distance between the vasculature and the ASCs, resulting in a hypoxic environment [54]. The lack of oxygen alters ASCs, leading to the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors including IL-6, IL-1

It has been suggested that hypoxic environments, like during obesity, lead to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [78]. During oxidative stress, breast cancer cells upregulate antioxidant-inducing pathways, like the Pentose Phosphate Pathway, as a means of eliminating reactive oxygen species. Breast cancer cells are known to upregulate glycolytic pathways as well, which are associated with worser outcomes [79]. An article assessing the correlation between ROS and 6245 breast cancer patient outcomes showed upregulation of glycolytic pathways, inflammation, and cancer-related genes. These patients had more significant heterogeneity amongst the cancer cell populations and increased mutation rates [80]. Interestingly, ASCs are also affected by hypoxic environments, which leads to secretion of proinflammatory cytokines [54]. Proinflammatory cytokines, paired with antioxidant protection, may promote cancer cell survival and mutation [81]. Interestingly, ASCs experiencing greater oxidative stress, such as those in visceral adipose compared to subcutaneous, are associated with lower proliferation, migration, and adipogenic potential, and have a higher senescent population [82]. However, when oxidative stress is inhibited, this inherent ASC dysfunction is corrected [82]. Similarly, in experimentally induced oxidative stress, ASCs upregulated stress-related proteins and increased secretions of IL-8 [83], which has been associated with inflammation in the TME [63]. Therefore, obesity-associated oxidative stress causes dysregulation in ASCs, which in turn, likely affects breast cancer prognoses (Fig. 4, Ref. [54, 80, 82, 83]). While there appears to be a connection between ASCs, breast cancer, and obesity-induced hypoxia, more studies need to be performed to determine the exact connection between them before this pathway can be targeted in therapies.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Obesity-induced Hypoxia and Resulting ROS Accumulation Leads to ASC Dysregulation and Breast Cancer Advancement. The hypoxic, obese environment leads to ROS accumulation. During ROS-related stress, breast cancer cells upregulate glycolysis, the Pentose Phosphate Pathway, and have higher mutation rates [80]. During oxidative stress, ASCs secrete proinflammatory cytokines [54, 83] and are associated with decreased migratory capacities [82]. ROS, reactive oxygen species. Created with BioRender.com.

Research has shed light on the potential implications of LEP signaling in the context of obesity and ER+ breast cancer in postmenopausal women. ObASCs express elevated LEP levels, activating aromatase to stimulate estrogen production [76, 77]. The increased estrogen levels then provide a positive feedback loop that promotes LEP expression in obASCs and contributes to the progression of postmenopausal breast cancer [9, 54, 76, 77]. Moreover, LEP, along with IL-6, can induce Notch signaling, which collectively contributes to proliferation, bone metastasis, and radiotherapy resistance in ER+ breast cancer [76]. These findings open new avenues for targeting LEP signaling as a potential therapeutic intervention.

Several studies have focused on the relationship between obesity and ER+ breast cancer; however, obesity has also been connected to the metastasis of TNBC through LEP-mediated pathways [84]. Previously, abASCs from obese patients (ob-abASCs) co-cultured with TNBC cell lines were shown to promote EMT by downregulating epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) in tumors and enhancing expression of mesenchymal markers and transcription factors, including SERPINE1 and snail family transcriptional repressor 2 (SNAI2), and Twist-related protein 1 (TWIST1), respectively [77]. Additionally, LEP from ob-abASCs was shown to contribute to a significant increase in phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in TNBC cells, a pathway that promotes tumor progression and metastasis [77]. Furthermore, ob-abASCs increased circulating cancer stem cells (CSCs) and enhanced lung metastases in vivo in a TNBC patient-derived xenograft (PDX) mouse model [77], indicating the role of obASCs in TNBC progression. Overall, these studies highlight several important signaling mechanisms including LEP, MAPKs, and EMT pathways that could contribute to breast cancer interactions with ASCs in the obese state.

Obesity alters the cytokine profile of ASCs and contributes to the progression and metastasis of breast cancer through LEP-mediated pathways. However, in the presence of cancer, ASCs further alter their secretory profiles and reduce their differentiation capacities [54]. Ritter et al. [54] (2023) showed that in the presence of TNBC cells, tumor-adjacent ln- and ob-brASCs secrete higher levels of cytokines and chemokines involved with migration and invasion. Surprisingly, after indirectly coculturing brASCs with triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, the cytokine profile of the distal ln- and ob-brASCs were altered more than the tumor-adjacent ln- and ob-brASCs. This finding emphasizes the influence of breast cancer-secreted factors on both tumor-adjacent and distal components of the TME [54]. Despite this difference between tumor-adjacent and distal brASCs, it is essential to note that all subgroups of brASCs exhibited moderate increases in CXCL1 and C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 5 (CXCL5) which are involved in breast cancer metastasis. Furthermore, ob-brASCs displayed increased secretion of IL-6 which activates the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK/STAT3), extracellular signal-related kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), and STAT3/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-

Perturbations in the endocrine functions of ASCs are the focus of several previous studies, but recent work has also shown evidence of alterations to the TME [84]. ASC differentiation is necessary to maintain tissue homeostasis and cell turnover, but ASCs display a more actively proliferating phenotype outside of differentiation [54]. In addition to obesity, the TME has also been shown to affect the differentiation capacity of ASCs. More specifically, brASCs from lean patients showed greater differentiation potential into adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes compared to the obASCs, but the tumor-adjacent lean (ln-) and ob-brASCs were less capable of adipogenesis compared to their tumor-distal counterparts [54]. Interestingly, PPAR-

Obesity alone enriches myofibroblasts in the breast adipose tissue [84]. However, the TME has also been shown to increase the ability of brASCs to differentiate into CAFs. When activated, CAFs can secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [85] and remodel the ECM [84], making it easier for cancer cell migration and invasion. When exposed to breast cancer cells, ob-abASCs have been shown to express higher levels of CAF markers [85]. Furthermore, primary brASCs from the TME exhibit significantly enhanced expression of CAF protein markers, including

Interestingly, while direct contact with breast cancer cells can cause ASCs to dedifferentiate into CAF-like phenotypes, direct cell-cell contact with newly formed myCAFs has been shown to promote migration and invasion through either type 1 or type 2 invasion. Type 1 invasion is a contractility-based mechanism by which myCAFs exert physical forces on the ECM or cancer cells [84]. Type 2 invasion is a chemical mechanism in which MMPs, secreted by these dedifferentiated ASCs, create degradative pores in the ECM [84]. Although both ln- and obASCs can form degradation pores in collagen, obASCs have been shown to favor type 1 invasion and are more invasive than lnASCs which tend to prefer type 2 invasion [84]. Moreover, not only are myCAFs able to enhance invasion of the TNBC cells, but they were also shown to promote invasion of the pre-malignant MCF10AT1 cell line [84], demonstrating that direct contact with the breast tumor promotes de-differentiation of brASCs into CAFs. In addition, it can also transform pre-malignant cells in the TME into malignant cells [84], ultimately resulting in a worse prognosis and poor outcomes for breast cancer patients.

In conclusion, ASCs from obese patients behave differently than ASCs from lean patients. ObASCs are more likely to differentiate into myCAFs, which in turn enhance migration of cancerous and pre-cancerous cells, furthering the notion that obASCs prime the TME for cancer progression. To effectively treat obese patients suffering from breast cancer, the mechanisms driving obASC-breast cancer interaction must be well-established. Only then will therapeutics be able to interrupt the interplay between the two cell types and prevent obASC-associated breast cancer progression.

With compelling evidence supporting the immunomodulatory effects of ASCs on cancer microenvironments, ASC vectors have garnered more attention as a potential solution for slowing cancer progression and recurrence. Malekshah et al. [86] used an ASC-vectored gene therapy to encourage tumor cells to die. ASCs expressing an enzyme capable of converting the inactive irinotecan to its active form (SN-38) were injected into mice. At the ovarian cancer site, cells activated the pro-drug, resulting in cancer cell death [86]. The vector platform improved prognosis in approximately 80% of human ovarian cancer xenograft mice cohorts. Growth suppression was achieved even in metastatic disease with associated ascites and cancer spheroid leakage into the abdominal cavity, which has historically challenged therapeutic approaches with resistance to traditional chemotherapeutic agents. This vector platform effectively reduced side effects typically associated with conventional chemotherapeutics, which are only effective at doses that cause significant weight loss and organ damage [86]. Another study aimed to integrate ASCs into a broader approach to cancer therapy. Researchers from University College London used MSC extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs) to deliver TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligands (TRAIL) in several cancer cell types, including lung, pleural, renal and breast. Notably, this therapeutic platform partially induced apoptosis in TRAIL-resistant cancer lines, providing a potential therapeutic option for patients with refractory disease [87]. Interestingly, this study provides a baseline for nontraditional ASC-vectored therapies for cancer treatment, which would be an unprecedented use of these cells in the clinic.

More recently, ASC vectored therapies have been applied to metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes mellitus, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, high cholesterol, and triglyceride disorders. Wang et al. [88] suggest that harvesting ASCs from diabetic donors may offer a new avenue to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus. While diabetic ASCs had poorer proliferative ability and reduced release of HGF compared to non-diabetic controls, they provided other therapeutic benefits in the study. When processed and introduced into mice with type 2 diabetes mellitus, diabetic ASCs improved insulin sensitivity and pancreatic beta cell mass. Utilizing stem cells in this way provides an alternative therapy to classical medication management with metformin, GLP-1 agonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors [88].

Furthermore, ASC therapeutics have been generated in the context of obesity. Researchers compared brown adipose tissue (BAT)-derived and WAT-derived ASCs and their immunomodulating activity on diet-induced, obese mice. Mice were injected weekly for three weeks with either type of therapy. Compared to the saline-injected control, both inducible brown and white ASC therapies improved weight and glucose control and promoted adipose tissue browning. Mice treated by the inducible brown ASC therapy demonstrated superior inflammatory control, evidenced by diminished mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-

While ASC vector therapy research has grown substantially with many studies boasting promising results, translation into clinical practice has been challenging. The safety of these therapies has been questionable without the availability of compelling evidence in clinical trials that these cell therapies provide patients with a favorable risk-to-benefit ratio. In a different approach using the properties of ASCs as therapeutics, a Japanese clinical trial measured the ability of ASCs to improve prognosis in liver cirrhosis patients. Autologous subcutaneous ASCs were infused into the liver circulation, and patients were followed closely over six months to one year. No serious adverse events were reported upon subsequent follow-ups at 1-month, 6-month, and 1-year intervals. Liver function tests improved or remained stagnant at 6 months post-therapy. Interestingly, this ASC therapy caused an increase in HGF and IL-6 with subsequent liver regeneration. These findings highlight the potential of ASC-based liver regeneration as an alternative to total liver transplant. However, the trial sample size was small, which limits the generalizability of the results [90].

Other clinical trials have shown conflicting results regarding the effect of ASCs on various disease states. ASC injection showed great promise in a phase III clinical trial monitoring the effect of ASCs on the osteoarthritic knee. In patients injected with ASCs, there were significant improvements to daily life and osteoarthritis-related pain compared to the control group. Minimal adverse effects were reported, and less than three percent of patients receiving ASC treatment reported any pain and swelling post-injection [91]. In contrast, in a separate clinical trial, ASCs had no significant effect on function in patients suffering from a shoulder tendon tear compared to a control group [92]. Interestingly, in another study, ASC-derived exosomes were administered to Alzheimer’s Disease patients intranasally twice weekly for twelve weeks. At a moderate dose, impairment levels were lower than in the higher and lower exosome dose groups following final administration. There was no difference in tau protein accumulation amongst groups, but the moderate dose group displayed lower rates of hippocampal shrinkage, although not significant [93]. In a separate phase I clinical trial, ASCs were assessed for their effect on spinal cord injuries. Patients displayed minor adverse effects after injection of ASCs into the subarachnoid space, but no serious events. Patients showed slight improvements to impairment a year after treatment; however, this must be investigated in subsequent clinical trials to confirm effectiveness [94]. Overall, ASCs show potential as therapeutics in contexts outside of obesity, cancer, and related diseases, including but not limited to osteoarthritis, muscle repair, and even neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s Disease. However, the beforementioned clinical trials highlight the importance of continuation of studies surrounding ASCs to confirm the specific applications that will maximize ASC therapeutic potential in patients, as they seem to have different effects in various anatomical environments and disease states.

ASCs boast benefits compared to their bone marrow-derived counterparts (BMSCs). The ratio of ASCs in adipose is greater than BMSCs in bone marrow, resulting in greater stem cell yield from adipose tissue than from the bone marrow. Another advantage of ASCs over BMSCs is the ease of extraction from patients, as bone marrow extraction is more invasive than adipose tissue extraction [95]. Despite these advantages and others, as well as the promising clinical outcomes of ASCs thus far, there are some challenges to ASC use as therapeutics. As evidenced by the impact both obesity and the presence of cancer has on the behavior of ASCs, they are directly influenced by their environment. To reflect this phenomenon, Paino et al. [96] (2017) cultured ASCs in the presence and absence of breast cancer cells and bone cancer cells. The ASCs cultured in the presence of cancer cells were able to differentiate into adipocytes as well as form tubes on Matrigel. However, the ASCs cultured in the absence of cancer cells were not able to undergo adipogenesis or angiogenesis [96]. Therefore, because ASCs may act differently depending on the presence of hypoxia [54, 82], cancer [54], or another stressor, it may be challenging to fully understand how ASCs will behave in separate individuals. Another consideration is regarding tumorigenicity. Based on a recent study monitoring MSC engulfment by breast cancer cells, the resulting hybrid cells were more senescent, which ultimately promoted a more metastatic phenotype [62]. Taken together with the conflicting results of recent clinical trials surrounding ASCs, the challenges imposed by ASC clinical use initiates hesitation amongst physicians and patients alike. Therefore, much research needs to be done before ASCs are regularly used as a treatment for a range of diseases.

In conclusion, ASCs, with their regenerative potential, are a field of great therapeutic interest. As this field expands, the importance of appropriate ASC selection becomes increasingly evident. Researchers are exploring other mammalian species and human depots to derive these cells for preclinical studies and therapeutics, respectively. However, to fully harness the potential of ASCs, studies must be coordinated to ensure consistency and scientific rigor in corroboration of results. Similarly, ASCs can be obtained from fat depots throughout the human body, increasing the potential for their therapeutic use. ThASCs and gluASCs both have greater adipogenic potentials compared to abASCs, but abASCs show greater adipogenesis compared to brASCs. Interestingly, both brASCs and bfpASCs have greater osteogenic potentials compared to abASCs, highlighting the biological differences between ASCs depending on their origin sites. Due to altered behaviors and differentiation potentials across ASCs from various depot extraction sites, much more research needs to be done to confirm that ASCs from a specific depot are being utilized for the most productive treatment.

There is evidence of the role of ASCs in contributing to poorer outcomes in patients, particularly in the context of breast cancer. This phenomenon is circular, with breast cancer cells leading to ASC dysregulation, and ASCs contributing to breast cancer progression. Similarly, excess fat accumulation also affects ASC function, thereby altering the risk of breast cancer development and progression. ASCs from lean patients have different differentiation potentials and gene expression profiles as those from obese patients. Similarly, signaling pathways are affected differently in lean and obese patients, underscoring the importance of follow-up research to identify targets in obese patients. Obesity-induced hypoxia alters ASCs, and hypoxia also affects breast cancer cells, but the connection between the two is relatively understudied in the literature. This connection needs to be made prior to targeting the oxidative stress pathways to interrupt ASC-breast cancer crosstalk in the context of obesity. In the future, it will be interesting to monitor the use of 3D ASC-breast cancer coculture studies in vitro as a simpler means of understanding this relationship. In vivo studies assessing the role of ASCs in breast cancer and the role of breast cancer in ASC dysregulation, not only in rodent models, but also in large mammal models will prove crucial as well. In future studies, it will be increasingly important to understand how the use of GLP-1 inhibitors like semiglutide will affect the ASC-breast cancer relationship. This review aimed to summarize the current understanding of the interplay between breast cancer and obesity mediated by ASCs. While ASCs are being used as therapeutic vectors for the treatment of disease, and many recent clinical trials have proven promising, there are some evident challenges therein. Suppose ASCs can be used for targeted therapies or be targeted themselves when dysregulated. In that case, there may be a greater use for ASCs that has yet to be uncovered, specifically in the context of obesity and breast cancer.

BAB conceived and executed the idea for this manuscript and finalized it. CRM wrote several sections of the manuscript, coordinated with others, and designed figures. MLH designed Table 1. CRM, TRF, NMC, MLH, KS, DRR, JFW, OMM, VTH, ECM, MEB, and BAB substantially contributed to the conception and drafting of the review. CRM, VTH, ECM, MEB, and BAB critically reviewed the work. All authors contributed to the final editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We acknowledge BioRender.com for figure creation.

This work was partially funded by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (Award # RP210046).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.