1 Departamento de Imunologia, Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas, Universidade de São Paulo, 05508-000 São Paulo, Brazil

2 Instituto de Investigação em Imunologia, Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia (INCT-iii), 05403-900 São Paulo, Brazil

Abstract

Memory T cells are essential for effective and durable immune responses, as they provide long-term immunological surveillance and rapid reactivity upon re-exposure to a given pathogen or cancer cell. In solid tumors, the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) often hinders immune activation, making enhancing memory T cell formation and persistence a key goal in cancer immunotherapy. Novel strategies are exploring ways to support these memory T cells, including using Listeria monocytogenes as a cancer vaccine vector. Notably, L. monocytogenes has unique properties that make it an ideal candidate for this purpose: it is highly effective at activating T cells, promoting the differentiation and survival of memory T cells, and modulating the TME to favor immune cell function. Thus, by leveraging the ability of L. monocytogenes to induce a strong, sustained T-cell response, researchers aim to develop vaccines that provide lasting immunity against tumors, reduce recurrence rates, and improve patient survival outcomes. This mini-review highlights the potential of memory T cell-focused cancer immunotherapy and the promising role of L. monocytogenes in advancing these efforts.

Keywords

- memory T cells

- Listeria monocytogenes

- cancer vaccines

- CD8+ T lymphocytes

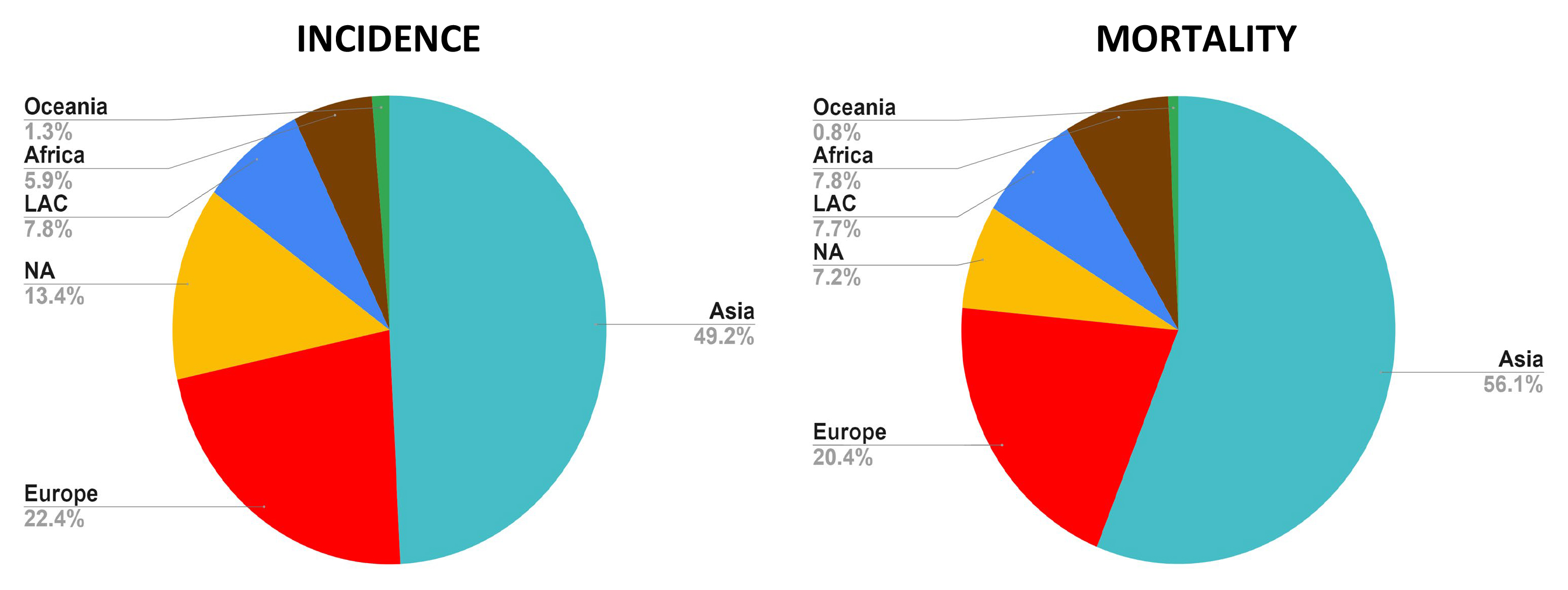

Cancer remains a significant unresolved global health challenge, affecting millions, and with projected annual cases expected to rise to 26 million by 2030 [1] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Incidence and mortality rates of cancer in all continents. The Asian continent contributes with the highest percentage of incidence and mortality rates, whereas Oceania displays the lowest frequencies. Asia and Africa are the continents with a proportionally increased mortality rate compared to their respective incidence frequency. These data reflect both men and women (Global Cancer Observatory, accessed November 30, 2024). LAC, Latin America and the Caribbean; NA, North America (created with Microsoft Excel).

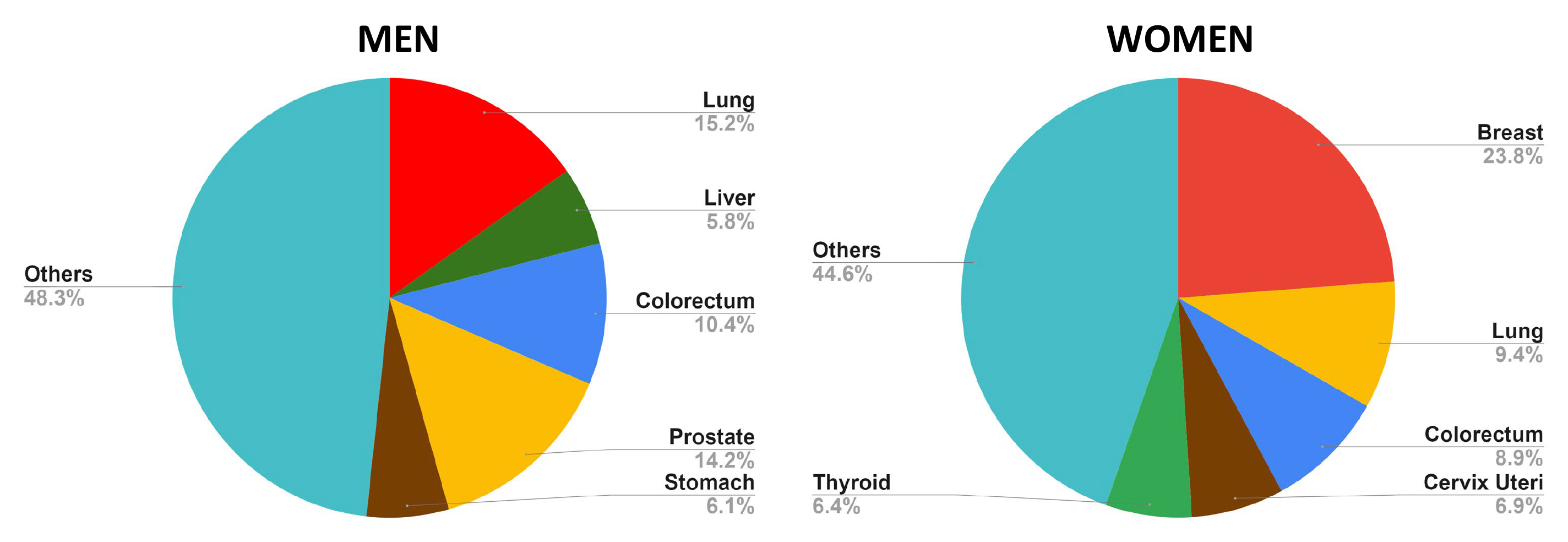

Rather than being a single entity, cancer encompasses over 100 different types, each with distinct molecular, genetic, and histological features [2]. This variability is underscored by the diverse etiological factors contributing to carcinogenesis, including environmental exposures (such as pollutants and radiation), genetic mutations, and lifestyle choices (such as diet, stress, and physical activity) [3, 4]. The most frequent cancer types in men and women across the globe include lung, liver, cervix uteri, breast, colorectum, prostate, and stomach cancers (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Top 5 most frequent cancers in men and women, highlighting the prevalence of each type within the respective populations. In men, the most commonly diagnosed cancers include lung, prostate, colorectal, stomach, and liver. For women, the top five cancers are breast, lung, colorectal, uterine, and thyroid cancer. The data underscores the variations in cancer incidence between genders, reflecting differences in risk factors, screening practices, and biological susceptibility (Global Cancer Observatory, accessed October 25, 2024) (created with Microsoft Excel).

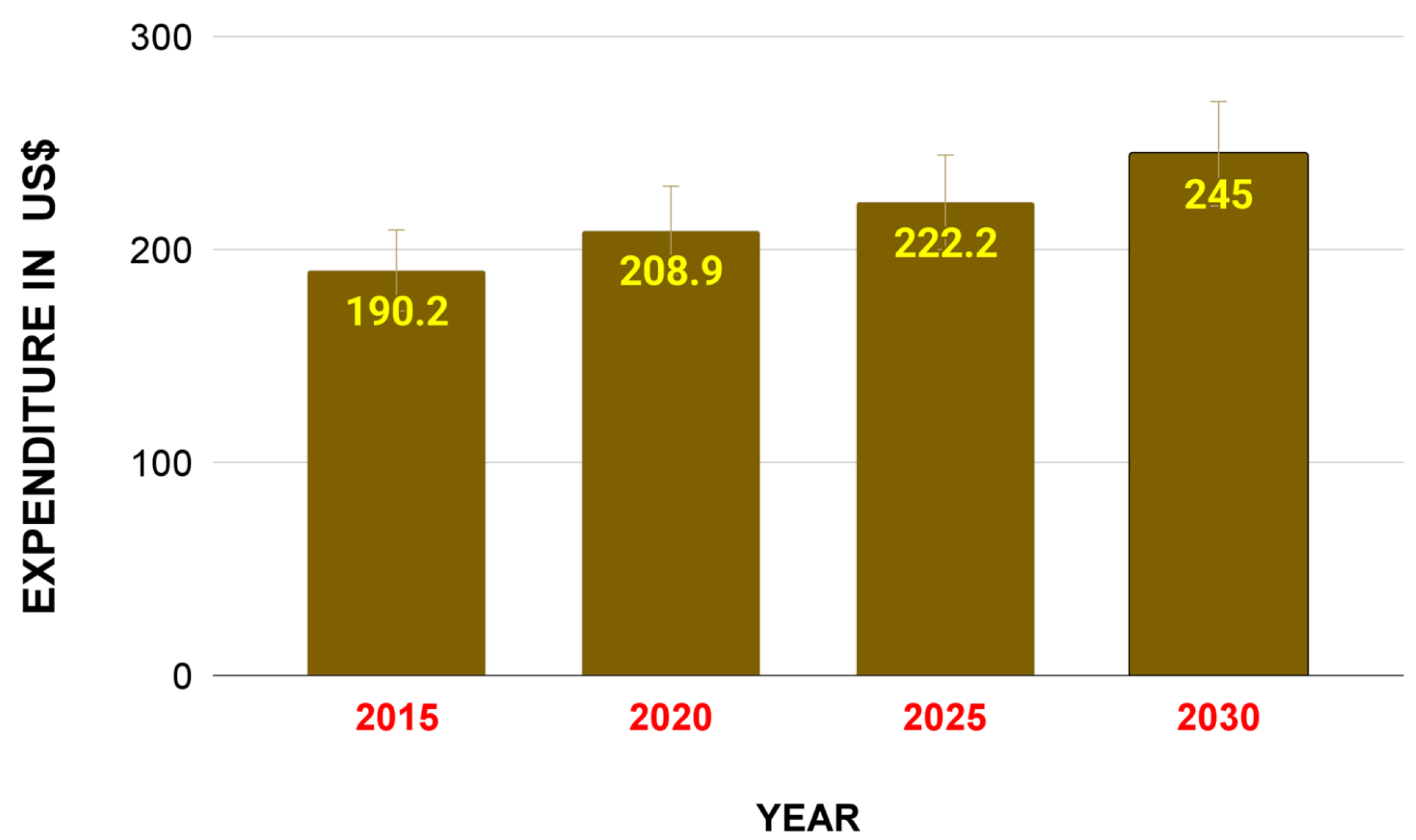

These malignancies account for a substantial proportion of the cancer burden, impacting both healthcare systems and the economy (Fig. 3). Importantly, recent advances in genomics and personalized medicine have further highlighted the necessity of stratifying cancer not just by its type or anatomical location but also by its unique molecular signature and the patient’s individual characteristics, enabling more targeted and effective therapeutic approaches [5, 6]. Still, the enormous complexity of this global health problem complicates both basic and translational research. Despite the complexities involved, advancements in cancer management and treatment have significantly progressed in recent years, contributing to a gradual increase in patient survival rates [7]. These advancements are primarily driven by breakthroughs in early detection, targeted therapies, and, notably, immunotherapies—innovative treatments designed to harness the body’s immune system to recognize and eliminate cancer cells more effectively.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Impact of cancer burden on the US economy. This graph illustrates national cancer expenditures in the United States of America in 2015 and 2020 and forecasts through 2030. A substantial increase in US cancer spending has a major impact on the economy, with this cost of cancer care being associated with the growth and aging of the population (obtained from the cancer trends progress report https://progressreport.cancer.gov/, created with Microsoft Excel).

The origins of cancer immunotherapy can be traced back to 1891, when William Coley, often regarded as the “Father of Cancer Immunotherapy”, pioneered efforts to harness the immune system to treat cancer. Coley observed that administering what became known as “Coley’s Toxins”, a mixture of heat-inactivated bacteria primarily consisting of Streptococcus pyogenes and Serratia marcescens, could trigger tumor regression in certain patients [8]. This marked an early attempt to leverage the immune response as a therapeutic tool against cancer.

Interestingly, Science magazine recognized cancer immunotherapy as the “Science of the Year” in 2013. A few years later, in 2018, James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries of immune checkpoint inhibition. Their work demonstrated how inhibitory proteins (Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) [9, 10]—Allison; and Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) [11, 12]—Honjo) on immune cells can be blocked to enhance the immune response against cancer cells, leading to the development of checkpoint inhibitors like Ipilimumab (Yervoy), pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo).

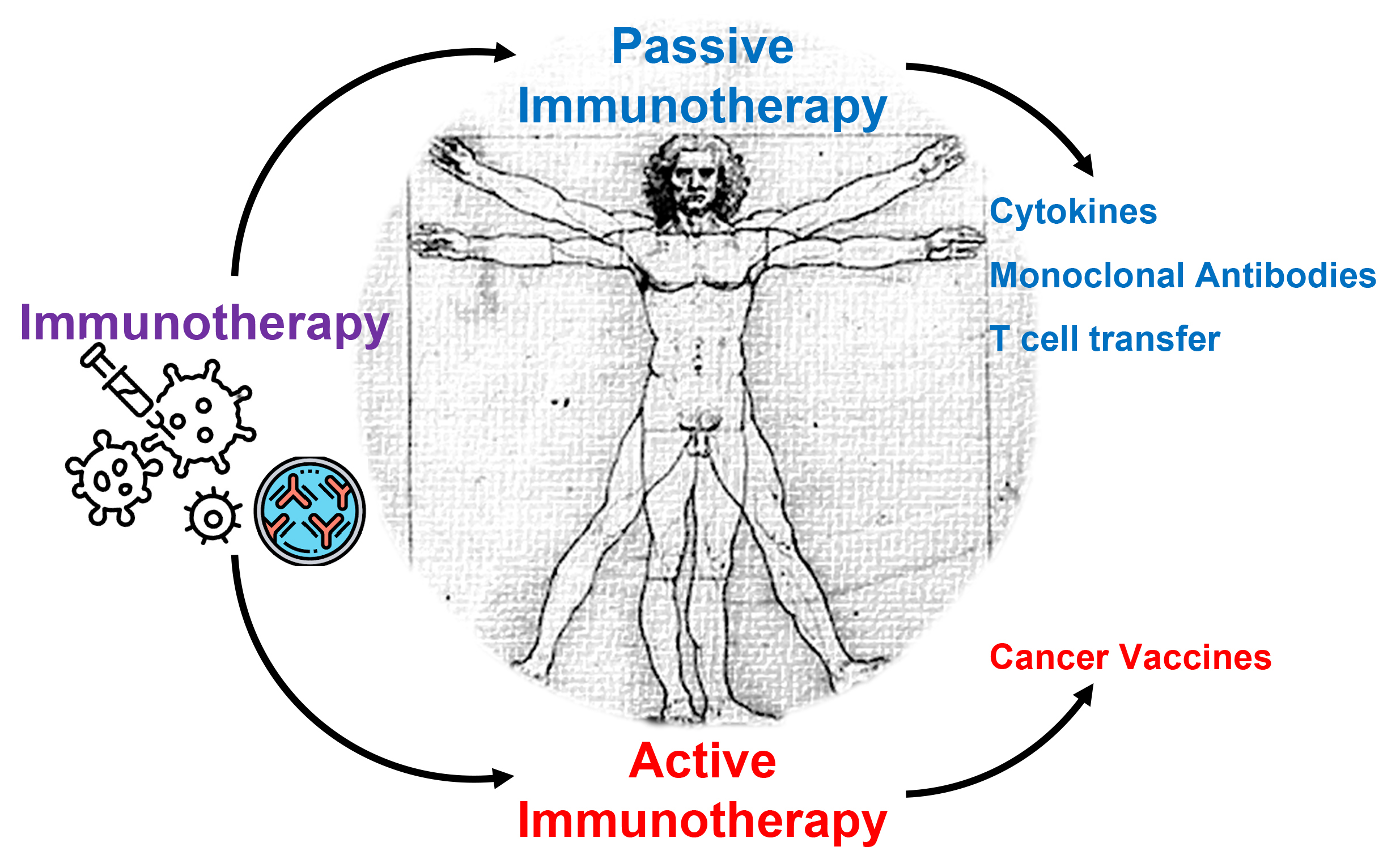

Today, cancer immunotherapies represent a groundbreaking approach to cancer treatment, leveraging the body’s immune system to identify and eliminate cancer cells [13]. Traditionally, treatments such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy focused on directly targeting tumors, often at the cost of considerable adverse effects [14]. On the other hand, immunotherapeutic approaches seek to potentiate the host immune response to recognize and eliminate malignant cells, either through passive or active mechanisms. This strategy encompasses diverse modalities, including cytokine therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, adoptive cell transfer, and cancer vaccines, each targeting distinct aspects of immune modulation to overcome the immune-evasive properties of tumors (Fig. 4) [15, 16].

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Different types of cancer immunotherapies. Active and passive immunotherapies are two different approaches used to stimulate or enhance the patient’s immune responses. Active immunotherapy involves stimulating the body’s immune system to generate a protective response against a specific target, whereas passive immunotherapy involves administering antibodies, cytokines, or immune components directly to a patient to provide immediate but temporary protection (created by GPAM, using Microsoft PowerPoint software).

Unlike traditional vaccines devised against foreign antigens expressed by pathogens, most anti-cancer vaccines are designed to stimulate the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells that exhibit self-antigens. These antigens, often unique to tumor cells, serve as markers that enable the immune system to distinguish between healthy and malignant cells [17, 18, 19].

There are two major types of cancer vaccines: preventive/prophylactic and therapeutic [20]. Prophylactic vaccines, such as the Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) vaccine, aim to avert the onset of cancer by inoculating individuals against virus-induced malignancies [21]. On the other hand, therapeutic vaccines are exploited to treat existing cancers by enhancing the immune response against tumor cells [22]. Recent advances in genetic engineering and personalized medicine have facilitated the development of individualized cancer vaccines tailored to the specific antigenic profile of a patient’s tumor. These innovations hold significant promise for improving the efficacy and specificity of cancer treatment, potentially leading to more durable responses and reduced toxicity compared to conventional therapies [23].

Despite the promising potential of cancer vaccines, several challenges remain in the design and delivery of effective vaccination strategies. One major hurdle is the identification of suitable delivery vectors that can effectively transport the vaccine components to target immune cells without causing adverse reactions [18]. Current delivery systems, such as live vectors, liposomes, and nanoparticles, each come with their own set of limitations, including stability, immunogenicity, and efficiency of antigen presentation [24, 25, 26]. Additionally, these vectors must overcome physiological barriers within the body, such as rapid clearance by the immune system and poor tissue penetration, which can significantly hinder their effectiveness. Furthermore, achieving the optimal balance between eliciting a robust, long-lasting immune response while minimizing off-target effects poses another challenge [27]. The proper activation of memory T and B cells is particularly important to achieve an enduring immune response against cancer cells.

Immunological memory is the cornerstone of vaccination. Optimizing the generation of memory T cells has led to advanced vaccine designs aimed at tailoring T cell responses to enhance overall efficacy [28]. Memory T cells are a specialized subset of T lymphocytes that play a crucial role in long-term protection against pathogens and cancer, forming an essential component of the adaptive immune response that can recognize and eliminate infected or tumor cells upon re-exposure [29]. Following an initial encounter with pathogens or tumor-associated antigens, T cells differentiate into memory cells, which persist in the body for years or even decades [30, 31]. Memory T cells are broadly categorized into central memory T cells (TCM), which reside in lymphoid tissues, and effector memory T cells (TEM), which circulate through peripheral tissues. TCM has a high proliferative capacity and can generate effector cells when reactivated, while TEM can quickly respond at the site of infection or tumor recurrence [32, 33, 34]. This division of labor within memory T cell subsets enables an efficient and coordinated immune response, playing a crucial role in long-term immunological protection by mounting a faster and more robust attack if the same cancer cells reappear.

Strategies that enhance the formation and persistence of memory T cells, such as combination therapies targeting immune checkpoints or using adjuvants, are being actively explored in clinical settings [35]. By focusing on the role of memory T cells, researchers aim to develop more effective cancer immunotherapies that provide enduring protection against tumor recurrence and improve overall survival rates for cancer patients.

The role of memory T cells becomes especially pertinent in the context of solid tumors, where the tumor microenvironment (TME) often exhibits immunosuppressive properties that hinder effective immune responses [36]. Solid tumors frequently manipulate the TME to evade immune surveillance, posing a significant challenge for long-term cancer control. Thus, interventions that not only initiate an immune response but also foster the generation and maintenance of memory T cells are vital to prevent tumor recurrence.

Current therapeutic strategies are exploring various methods to enhance the persistence and functionality of memory T cells. Combination therapies that target immune checkpoints, such as PD-1/Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and CTLA-4, as described above, have shown potential in reactivating exhausted T cells and promoting a memory phenotype in the tumor milieu [33]. Additionally, the use of immunologic adjuvants has been investigated for their ability to boost the initial activation of T cells, thus facilitating the establishment of durable memory populations [37]. These approaches aim to create a more favorable TME that supports memory T cell survival and function, enhancing long-term immune surveillance and reducing the likelihood of cancer relapse. Interestingly, recombinant Listeria monocytogenes represents an ideal candidate for cancer vaccines due to its ability to enhance T cell activation, promote memory T cell persistence, and modulate the tumor microenvironment, collectively supporting durable immune surveillance and reducing the risk of cancer recurrence.

Listeria monocytogenes (LM) has emerged as an innovative model for developing cancer vaccines due to its unique ability to elicit strong immune responses [38, 39, 40, 41]. As a facultative intracellular bacterium, LM has evolved mechanisms to survive and replicate within host cells, effectively stimulating both innate and adaptive immunity [42]. This characteristic makes it an attractive vector for cancer vaccine development, as it can deliver tumor-associated antigens directly to antigen-presenting cells, thereby enhancing the priming of CD8+ T cells [43]. Indeed, attenuated strains of L. monocytogenes designed to express tumor-associated antigens have been described over the years. For instance, Shahabi et al. (2008) [44] and Hannan et al. (2012) [45] demonstrated that an engineered LM strain expressing the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) showed enhanced antitumor immunity in preclinical models of prostate cancer. The results indicated that not only did the modified LM elicit a robust CD8+ T-cell response, but it also stimulated antitumor activity by generating a systemic immune response that was effective against established tumors. Other studies have engineered LM strains to express a variety of antigens, such as ovalbumin [39], mesothelin [46], mage-b [47, 48], tetanus toxoid [49], and HPV E7 [50], among others.

The use of L. monocytogenes in cancer vaccination strategies has shown considerable promise in preclinical models [51, 52, 53], demonstrating robust anti-tumor immunity and significant tumor regression [50, 54, 55, 56]. LM’s unique ability to activate the immune system through multiple pathways not only targets tumor cells directly but also promotes the formation of memory T cells, thereby contributing to durable immunity and reducing the risk of cancer recurrence [43]. Current research into genetically engineered LM strains focuses on improving the safety and effectiveness of these vaccines, with the goal of developing novel therapeutic options in cancer immunotherapy [46, 50].

Additionally, several Phase 1, Phase 2 and Phase 3 clinical trials have investigated the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of LM-based vaccines (Table 1). Preliminary data indicate enhanced immune activation and promising clinical responses in treating difficult-to-manage tumors, including malignant pleural mesothelioma [57], metastatic pancreatic cancer [58], advanced cervical cancer [59], Hodgkin lymphoma [37], and prostate cancer [60]. These studies highlight the potential of LM-based vaccines to redefine immunotherapeutic approaches for treating refractory cancers.

| NCT number | LM-base vaccine | Combined therapy | Tumor type(s) | Target antigens | Bacterial features | Trial phase | Serious adverse events (SAEs) | Overall survival (OS) | Progression-free survival (PFS) | Conclusions |

| NCT01417000 | CRS-207 | GVAX pancreas vaccine (with cyclophosphamide) alone and in combination with CRS-207 | Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma | _ | _ | Phase 2 | Cy/GVAX + CRS-207: | Cy/GVAX + CRS-207: | _ | Treatment (Cy/GVAX + CRS-207) was well-tolerated and demonstrated efficacy given that the OS was improved compared to the control therapy. |

| 29/64 (45.31%) | 6.28 (4.47 to 9.40) months | |||||||||

| Cy/GVAX: | ||||||||||

| 10/29 (34.48%) | Cy/GVAX: | |||||||||

| 4.07 (3.32 to 5.42) months | ||||||||||

| NCT02004262 | CRS-207 | CRS-207 Alone and in combination with GVAX Pancreas Vaccine (with cyclophosphamide) and | Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma | _ | _ | Phase 2 | Cy/GVAX + CRS-207: | Cy/GVAX + CRS-207: | Cy/GVAX + CRS-207: | Treatment (Cy/GVAX + CRS-207) was well-tolerated but did not demonstrate efficacy given that the difference in OS between the treated and control groups was not significant. |

| 44/94 (46.81%) | 3.8 (2.9 to 5.3) months | 2.3 months | ||||||||

| CRS-207: | CRS-207: | |||||||||

| 32/87 (36.78%) | CRS-207: | 2.1 months | ||||||||

| Chemotherapy: | 5.4 (4.2 to 6.9) months | Chemotherapy: | ||||||||

| Chemotherapy Alone | 15/54 (27.78%) | 2.1 months | ||||||||

| Chemotherapy: | ||||||||||

| 4.6 (4.2 to 5.8) months | ||||||||||

| NCT01266460 | ADXS11-001 | N/A | Persistent or Recurrent Squamous or Non-Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Cervix | HPV 16 E7 | Live-attenuated strain encoding HPV 16 E7 antigens | Phase 2 | ADXS11-001: | ADXS11-001: | ADXS11-001: | Treatment (ADXS11-001) was well-tolerated and demonstrated efficacy given the OS. |

| 27/50 (54.00%) | 6.1 (4.3 to 12.1) months | 2.8 (2.6 to 3.0) months | ||||||||

| NCT01967758 | ADU-623 | N/A | Treated and Recurrent WHO Grade III/IV Astrocytomas | EGFRvIII and NY-ESO-1 | Live-attenuated strain encoding EGFRvIII and NY-ESO-1 antigens to induce proliferation of memory and effector T cells | Phase 1 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT01675765 | CRS-207 | CRS-207 followed by chemotherapy (pemetrexed and cisplatin) and in combination with cyclophosphamide followed by chemotherapy | Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma | Mesothelin | Live-attenuated strain engineered to elicit an immune response against the tumor-associated antigen mesothelin | Phase 1 | CRS-207 + Chemotherapy: | CRS-207 + Chemotherapy: | CRS-207 + Chemotherapy: | Treatment (CRS-207 + Chemotherapy) was well-tolerated and demonstrated efficacy given the OS. |

| 15/38 (39.47%) | 14.7 (11.2 to 21.9) months | 7.5 (7.0 to 9.9) months | ||||||||

| CRS-207/Cy + Chemotherapy: | ||||||||||

| 11/22 (50.00%) | ||||||||||

| NCT02002182 | ADXS11-001 | Vaccine administration was followed by Robot-Assisted Resection | HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma | _ | Live-attenuated strain | Phase 2 | ADXS11-001: | _ | _ | _ |

| 5/9 (55.56%) | ||||||||||

| Standard of care therapy: | ||||||||||

| 1/6 (16.67%) | ||||||||||

| NCT00327652 | CRS-100 | N/A | Carcinoma and Liver Metastases | _ | Live-attenuated strain with limited cell-to-cell spread and invasion of liver cells | Phase 1 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT02625857 | JNJ-64041809 | N/A | Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer | _ | Live-attenuated Double-Deleted strain | Phase 1 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT02164461 | ADXS11-001 | Prophylactic premedication (antihistamines, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiemetics, histamine H2-receptor antagonists, and IV hydration) | HPV-Positive Cervical Cancer | _ | _ | Phase 1 | ADXS11-001 1 × 109 CFU: | _ | ADXS11-001 1 × 109 CFU: | _ |

| 1/1 (100.00%) | 124.0 (NA to NA) days | |||||||||

| ADXS11-001 5 × 109 CFU: | ||||||||||

| ADXS11-001 5 × 109 CFU: | ||||||||||

| 2/6 (33.33%) | ||||||||||

| ADXS11-001 1 × 1010 CFU: | 85.0 (80.0 to 99.0) days | |||||||||

| 1/5 (20.00%) | ADXS11-001 1 × 1010 CFU: | |||||||||

| 176.5 (78.0 to 528.0) days | ||||||||||

| NCT03847519 | ADXS-503 | Alone and in Combination with Pembrolizumab | Metastatic Squamous or Non-Squamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Multiple squamous and non-squamous NSCLC antigens | Live-attenuated and genetically modified strain to elicit T cell responses against shared tumor antigens commonly found in patients with squamous and non-squamous NSCLC | Phase 1/2 | Safety Phase Part A-ADXS-503: | _ | _ | Treatment (ADXS-503 + Pembrolizumab) was well-tolerated and demonstrated efficacy given that it induces antigen-specific T-cell responses and elicits durable control of the disease. |

| 3/7 (42.86%) | ||||||||||

| Safety Phase Part B-ADXS-503 + Pembrolizumab: | ||||||||||

| 2/14 (14.29%) | ||||||||||

| Efficacy Phase Part C-ADXS-503 + Pembrolizumab: | ||||||||||

| 3/3 (100.00%) | ||||||||||

| NCT02325557 | ADXS31-142 | Alone and in combination with Pembrolizumab | Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer | _ | _ | Phase | Part A-ADXS31-142 1 × 109 CFU: | Part A-ADXS31-142 1 × 109 CFU: | Part A-ADXS31-142 1 × 109 CFU: | Treatment (ADXS31-142 + Pembrolizumab) was well-tolerated and it was observed an OS benefit in combination-treated patients that were previously treated with docetaxel. |

| 1/2 | ||||||||||

| 4/10 (40.00%) | 7.8 (1.3 to NA) months | 2.2 (0.8 to NA) months | ||||||||

| Part A-ADXS31-142 5 × 109 CFU: | ||||||||||

| Part A-ADXS31-142 5 × 109 CFU: | Part A-ADXS31-142 5 × 109 CFU: | |||||||||

| 1/1 (100.00%) | ||||||||||

| Part A-ADXS31-142 1 × 1010 CFU: | 18.5 (NA to NA) months | NA (NA to NA) months | ||||||||

| 1/2 (50.00%) | Part A-ADXS31-142 1 × 1010 CFU: | Part A-ADXS31-142 1 × 1010 CFU: | ||||||||

| Part B -ADXS31-142 + Pembrolizumab: | ||||||||||

| 7.8 (NA to NA) months | NA (NA to NA) months | |||||||||

| 22/37 (59.46%) | Part B -ADXS31-142 + Pembrolizumab: | Part B -ADXS31-142 + Pembrolizumab: | ||||||||

| 9 CFU: | 5.3 (2.1 to 7.9) months | |||||||||

| 33.7 (15.4 to NA) months | ||||||||||

| NCT03006302 | CRS-207 | Epacadostat/Pembrolizumab/Cyclophosphamide/GVAX Pancreas Vaccine | Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | _ | _ | Phase 2 | Part 1-Dose Level 1: | _ | _ | _ |

| 3/6 (50.00%) | ||||||||||

| Part 1-Dose Level 2: | ||||||||||

| 3/4 (75.00%) | ||||||||||

| Part 1X-Dose Level 2: | ||||||||||

| 1/3 (33.33%) | ||||||||||

| Part 1X-Dose Level 3: | ||||||||||

| 2/7 (28.57%) | ||||||||||

| Part 2-Dose Expansion: | ||||||||||

| 7/20 (35.00%) | ||||||||||

| NCT03190265 | CRS-207 | CRS-207, Nivolumab, and Ipilimumab Alone and in Combination with GVAX Pancreas Vaccine (with cyclophosphamide) | Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma | _ | _ | Phase 2 | Arm A-CY, Nivolumab, Ipilimumab, Pancreas GVAX, CRS-207: | _ | _ | _ |

| 24/30 (80.00%) | ||||||||||

| Arm B-Nivolumab, Ipilimumab, CRS-207: | ||||||||||

| 21/27 (77.78%) | ||||||||||

| NCT02243371 | CRS-207 | CRS-207 and GVAX pancreas vaccine (with cyclophosphamide) Alone and in combination with Nivolumab | Previously Treated Metastatic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma | _ | _ | Phase 2 | Arm A-CY/GVAX/CRS-207/Nivolumab: | Arm A-CY/GVAX/CRS-207/Nivolumab: | Arm A-CY/GVAX/CRS-207/Nivolumab: | Treatments (Arm A and Arm B) have different effects on the peripheral repertoire, and indicate potential for TCR repertoire profiling. |

| 5/51 (9.80%) | 5.88 (4.73 to 8.64) months | 2.23 (2.14 to 2.33) months | ||||||||

| Arm B-CY/GVAX/CRS-207: | ||||||||||

| Arm B-CY/GVAX/CRS-207: | Arm B-CY/GVAX/CRS-207: | |||||||||

| 1/42 (2.38%) | ||||||||||

| 6.11 (3.52 to 7.00) months | 2.17 (2.00 to 2.30) months | |||||||||

| NCT02399813 | ADXS11-001 | N/A | Persistent/Recurrent, Loco-Regional or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anorectal Canal | _ | _ | Phase 2 | ADXS11-001: | _ | ADXS11-001: | _ |

| 15/36 (41.67%) | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.1) months | |||||||||

| NCT02386501 | ADXS31-164 | N/A | HER2-Expressing Solid Tumors | _ | _ | Phase 1/2 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT01598792 | ADXS11-001 | N/A | HPV-16 positive Oropharyngeal Carcinoma | Human Papilloma Virus Genotype 16 Target Antigens | Genetically modified strain | Phase 1 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT03189030 | pLADD | N/A | Metastatic Colorectal Cancer | Patient-specific antigens | Live-attenuated Double-deleted strain encoding patient-specific antigens | Phase 1 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT02592967 | JNJ-64041757 | N/A | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | _ | Live-attenuated Double-Deleted strain | Phase 1 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT00585845 | CRS-207 | N/A | Advanced Solid Tumors Who Have Failed or Who Are Not Candidates for Standard Treatment | Mesothelin | Live-attenuated and genetically modified strain to release the antigen Mesothelin | Phase 1 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT02575807 | CRS-207 | Alone and in Combination with Epacadostat and/or Pembrolizumab | Platinum-Resistant Ovarian, Fallopian, or Peritoneal Cancer | _ | _ | Phase 1/2 | Phase 1-CRS-207: | Phase 1-CRS-207: | Phase 1-CRS-207: | _ |

| 2/8 (25.00%) | 49.07 (4.71 to 69.29) weeks | 8.43 (3.00 to 9.71) weeks | ||||||||

| Phase 1-CRS-207/IDO 100 mg: | ||||||||||

| Phase 1-CRS-207/IDO 100 mg: | Phase 1-CRS-207/IDO 100 mg: | |||||||||

| 1/4 (25.00%) | ||||||||||

| Phase 1-CRS-207/IDO 300 mg: | 30.00 (18.71 to 88.71) weeks | 4.71 (3.29 to 17.14) weeks | ||||||||

| 9/16 (56.25%) | Phase 1-CRS-207/IDO 300 mg: | Phase 1-CRS-207/IDO 300 mg: | ||||||||

| Phase 2-CRS-207/Pembro/IDO: | ||||||||||

| 27.00 (18.14 to 51.29) weeks | 8.43 (4.29 to 36.00) weeks | |||||||||

| 1/1 (100.00%) | ||||||||||

| Phase 2-CRS-207/Pembro: | Phase 2-CRS-207/Pembro/IDO: | |||||||||

| 1/3 (33.33%) | 9.29 weeks | |||||||||

| Phase 2-CRS-207/Pembro: | ||||||||||

| 18.43 (10.43 to 18.57) weeks | ||||||||||

| NCT03371381 | JNJ-64041757 | Nivolumab Alone and in Combination with JNJ-64041757 | Advanced Adenocarcinoma of the Lung | _ | _ | Phase 1/2 | JNJ-64041757 + Nivolumab: | _ | _ | Treatment (JNJ-64041757+ Nivolumab) was well-tolerated but the study was terminated given the risk-benefit profile. |

| 5/12 (41.67%) | ||||||||||

| NCT03265080 | ADXS-NEO | Alone and in Combination with Pembrolizumab | Advanced or Metastatic Solid Tumors | Patient-specific tumor antigens | Vaccine that expresses patient-specific tumor antigens and that activates tumor-killing T cells | Phase 1 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT03175172 | CRS-207 | Pembrolizumab | Previously-Treated Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma | _ | _ | Phase 2 | CRS-207 + Pembrolizumab: | CRS-207 + Pembrolizumab: | CRS-207 + Pembrolizumab: | The study was terminated given that it did not demonstrate efficacy. |

| 4/10 (40.00%) | 12.57 (8.14 to 18.14) weeks | 6 (3.43 to 7.14) weeks | ||||||||

| NCT03122548 | CRS-207 | Pembrolizumab | Recurrent or Metastatic Gastric, Gastroesophageal Junction, or Esophageal Adenocarcinomas | _ | _ | Phase 2 | CRS-207 + Pembrolizumab: | CRS-207 + Pembrolizumab: | CRS-207 + Pembrolizumab: | _ |

| 4/5 (80.00%) | 11.57 (4.00 to 14.43) weeks | 5.43 (0.14 to 6.00) weeks | ||||||||

| NCT02853604 | ADXS11-001 | N/A | Locally advanced cervical cancer at higher risk for recurrence | _ | _ | Phase 3 | ADXS11-001: | _ | _ | _ |

| 10/72 (13.89%) | ||||||||||

| Placebo: | ||||||||||

| 3/37 (8.11%) | ||||||||||

| NCT02291055 | ADXS11-001 | ADXS11-001 or MEDI4736 alone and in combination | Advanced or Metastatic Cervical or HPV + Head & Neck Cancer | _ | _ | Phase 1/2 | Part A Escalation (Cervical)-1 × 109 CFU ADXS11-001/3 mg/kg MEDI4736: | Part A (Cervical)-1 × 109 CFU ADXS11-001/3 mg/kg MEDI4736: | Part A (Cervical)-1 × 109 CFU ADXS11-001/3 mg/kg MEDI4736: | _ |

| NA (2.8 to NA) months | 3.7 (1.8 to 22.1) months | |||||||||

| 2/5 (40.00%) | ||||||||||

| Part A Escalation (Cervical and Head and Neck)-1 × 109 CFU ADXS11-001/10 mg/kg MEDI4736: | Part A + Part B (Cervical)-1 × 109 CFU ADXS11-001/10 mg/kg MEDI4736: | Part A + Part B (Cervical)-1 × 109 CFU ADXS11-001/10 mg/kg MEDI4736: | ||||||||

| 9.3 (6.0 to NA) months | 2.1 (1.7 to 3.8) months | |||||||||

| 3/5 (60.00%) | ||||||||||

| Part A Expansion (Head and Neck)-1 × 109 CFU ADXS11-001/10 mg/kg MEDI4736: | Part B Expansion (Cervical)-10 mg/kg MEDI4736: | Part B Expansion (Cervical): 10 mg/kg MEDI4736: | ||||||||

| 9.2 (6.9 to NA) months | 5.0 (1.8 to 6.9) months | |||||||||

| 4/11 (36.36%) | Part A Escalation and Expansion (Head and Neck)-1 × 109 CFU ADXS11-001/10 mg/kg MEDI4736: | Part A Escalation and Expansion (Head and Neck)-1 × 109 CFU ADXS11-001/10 mg/kg MEDI4736: | ||||||||

| Part B Expansion (Cervical)-10 mg/kg MEDI4736: | ||||||||||

| 13/27 (48.15%) | ||||||||||

| Part B Expansion (Cervical)-1 × 109 CFU ADXS11-001/10 mg/kg MEDI4736: | ||||||||||

| 4.8 (3.6 to NA) months | 3.5 (1.6 to 5.3) months | |||||||||

| 15/27 (55.56%) | ||||||||||

| NCT01116245 | ADXS11-001 | N/A | Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Grade | E7 substance | Live-attenuated and genetically modified strain to cause an immune reaction against the E7 substance | Phase 2 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT01671488 | ADXS11-001 | ADXS11-001 in combination with 5FU, mitomycin, and IMRT | Anal Cancer | _ | _ | Phase 1/2 | ADXS11-001 + 5FU + Mitomycin + IMRT: | _ | _ | Treatment (ADXS11-001 + 5FU + Mitomycin + IMRT) was well-tolerated and it was observed an PFS benefit in patients with locally advanced disease. |

| 10/10 (100.00%) | ||||||||||

| NCT01116245 | ADXS11-001 | N/A | Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Grade | E7 substance | Live-attenuated and genetically modified strain to cause an immune reaction against the E7 substance | Phase 2 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT02531854 | ADXS11-001 | Pemetrexed Alone and in Combination with ADXS11-001 | HPV-Positive Non-Squamous, Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma | tLLO–HPV-E7 | Live-attenuated and genetically modified strain to secrete an antigen-adjuvant fusion protein tLLO–HPV-E7 | Phase 2 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

| NCT02906605 | JNJ-64041809 | Apalutamide Alone and in Combination with JNJ-64041809 | Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer | _ | _ | Phase 2 | _ | _ | _ | _ |

CRS, Cancer Response Stimulator; LM, Listeria monocytogenes; 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; NCT, national clinical trial; HPV, Human Papilloma Virus; EGFRvIII, epidermal growth factor receptor variant III; NSCLC, Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma; tLLO–HPV-E7, truncated fragment of the listeriolysin O fused to the full-length E7 peptide of HPV-16; CFU, Colony Forming Units; Cy, cyclophosphamide; GVAX, GM-CSF–secreting allogeneic pancreatic tumor cells; IDO, indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase; NA, not available.

LM is well known for its ability to activate robust innate immune responses, which play a critical role in shaping adaptive immunity [61, 62] and enhancing overall anti-tumor effects [53, 63]. Upon infection, LM is recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) [64, 65] on innate immune cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells [66]. These PRRs, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors, detect components of the bacterium, such as its cell wall and intracellular proteins [67, 68]. Activation of these receptors leads to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which serve to recruit and activate additional immune cells, including natural killer (NK) cells and CD8+ T cells [69, 70]. This initial inflammatory response is crucial to create a conducive environment for subsequent adaptive immune responses, amplifying the overall immune reaction against tumors [71, 72].

The strategy of utilizing LM to stimulate the innate immune system is particularly advantageous in cancer therapy, as it helps to bridge the gap between innate and adaptive immunity. For example, the activation of innate lymphoid cells and macrophages by LM enhances the cross-presentation of tumor antigens, thereby priming T cells for a more effective attack on cancer cells [61]. Furthermore, LM infection can promote the maturation of dendritic cells, which are essential for initiating T-cell responses [32, 73]. This dual action not only bolsters immediate immune defenses but also fosters the development of long-lived memory T cells capable of maintaining immune surveillance against potential tumor recurrence [73].

The process of induction of memory T cells by LM is a pivotal aspect of its role as an effective model for cancer vaccines. Following the initiation of innate immune responses, LM’s ability to replicate within host cells allows it to deliver tumor-associated antigens to dendritic cells, which are essential for the activation and differentiation of naïve T cells. This process begins with the cross-presentation of antigens, where dendritic cells process intracellular antigens from LM and present them on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules to CD8+ T cells [42]. As CD8+ T cells are primed, they undergo clonal expansion and differentiation into cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), which actively seek out and eliminate tumor cells exhibiting the same antigen [54, 56, 74, 75]. Moreover, CD4+ T helper cells are also activated, assisting in the overall T cell response and enhancing the cytotoxic capabilities of CD8+ T cells through the release of supportive cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-

Notably, the robust adaptive immune response induced by LM not only targets existing tumors but also leads to the formation of memory T cells. Notably, the depletion of CD8+ T cells negatively impacts tumor protection, demonstrating that tumor immunity is largely mediated by CD8+ memory T cells [76]. Up to 10% of the activated CD8+ T cells formed the memory population, enhancing stable protection by swiftly activating their effector abilities [43]. These memory T cells persist long after the initial immune response, equipped with the ability to rapidly mount a response upon re-encountering the same antigen [77]. The memory T cells could exhibit time-dependent alterations and persist as a heterogeneous population, such as stem, central, effector, and resident memory T cells [76]. These cells exhibit reduced susceptibility to apoptosis and demonstrate more efficient activation compared to naïve T cells within the tumor microenvironment of tumor-bearing mice and cancer patients [39, 61]. This feature is particularly advantageous in the context of cancer treatment, as it establishes an enduring immunological memory that can effectively surveil against tumor recurrence. The durable nature of the memory T cell population generated through LM-based vaccines provides hope for long-term protection, potentially translating into improved survival rates and reduced relapse in cancer patients [78]. As research advances in optimizing LM as a tumor immunotherapy platform, the focus on inducing both immediate and lasting adaptive immune responses will be key to enhancing the efficacy of cancer vaccines.

The recent studies discussed here have offered new insights into the potential and pitfalls of L. monocytogenes-based vaccines in oncology. One attractive aspect that has been explored is the combination of LM-based vaccines with other immunotherapeutic strategies. A recent study examined the efficacy of an LM-based vaccine in conjunction with checkpoint inhibitors using a mouse model of melanoma. The results demonstrated that this combination therapy resulted in heightened immune activation and significant tumor regression compared to either treatment alone [79]. These findings suggest that LM-based vaccines could enhance the effectiveness of currently available immunotherapies, offering new avenues for cancer treatment. In fact, several Phase I and II clinical trials using the combination of LM-based vaccines and checkpoint inhibitors such as Pembrolizumab, Nivolumab, and Ipilimumab are underway (Table 1).

The randomized trial NCT01417000 investigated the effectiveness of the GVAX pancreas vaccine combined with cyclophosphamide and the CRS-207 live-attenuated vaccine for treating metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The results were encouraging, showing that this combination therapy was well-tolerated and led to an overall survival (OS) of 6.28 months, which was notably better than the control therapy’s OS of 4.07 months [80]. Another trial demonstrating the efficacy of the CRS-207 vaccine was the non-randomized study NCT01675765, which focused on malignant pleural mesothelioma. In this trial, the vaccine was designed to stimulate an immune response against the mesothelin antigen and was administered alongside chemotherapy (pemetrexed and cisplatin). Patients experienced a promising OS of 14.7 months and a progression-free survival (PFS) of 7.5 months [57, 81]. The LM-based vaccine ADXS11-001 has also shown success in clinical trials, such as NCT01266460, where it was engineered to express HPV 16 E7 antigens. This trial targeted patients with persistent or recurrent squamous or non-squamous cervical cancer and reported an OS of 6.1 months and a PFS of 2.8 months, with the treatment being well-tolerated [82, 83]. Additionally, the NCT01671488 trial evaluated ADXS11-001 in combination with 5-fluorouracil (5FU), mitomycin, and intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for anal cancer. Results indicated that the treatment was well-tolerated and led to improvements in PFS for patients with advanced disease [84, 85]. Other trials include the non-randomized studies NCT03847519 and NCT02325557. In the NCT03847519 trial, the LM-based vaccine ADXS-503 was developed to trigger T cell responses against antigens commonly found in squamous and non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. This treatment was well-tolerated and showed potential for durable disease control. Meanwhile, the NCT02325557 trial assessed the ADXS31-142 vaccine in combination with Pembrolizumab for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, revealing an OS benefit in patients who had previously received docetaxel, with the treatment also being well-tolerated [60, 86, 87, 88]. Across all these clinical trials, a variety of adverse events were reported, ranging from mild to severe. However, the overall consensus was that the treatments were well-tolerated, considering their risk-benefit profiles.

In a related direction, Morrow and Sauer (2021) [89] observed that IFNAR-/- mice developed a stronger LM-specific memory CD8+ T cell response that remarkably protected these mice from LM rechallenge, suggesting that inhibition of type-I interferon signaling by immunotherapeutic approaches during LM-based vaccination may result in enhanced prophylactic vaccine efficacy to pathogen-related cancers. Along with this observation is the fact that the magnitude and duration of the immune response elicited by LM-based vectors depend critically on the host genetic background, including genes related to the control of inflammatory cell death [39]. We have shown that caspase-1/11 and gasdermin-D (GSDMD) individual deficiencies positively impact the generation of long-lasting effector/memory CD8+ T cells, possibly due to the extended permanence of live, replicating bacteria in these mice [56]. Indeed, killed or inactivated vaccines generally do not induce optimal protective immunity [42, 90]. Notwithstanding, it is important to note that not all immunodeficiency that lengthen the period of live vector activation of the adaptive immune response will result in improved protection, since a particular deficiency might be detrimental to the host by itself. It means that immunocompromised patients are more likely to suffer from complications due to uncontrolled growth of the vaccine vector than to benefit from the duration of vector activation of their immune system. In any case, these recent observations underscore the importance of considering the interplay between vector-based vaccines and the patient/host genetic (and epigenetic) landscape and emphasize the need for further investigation on the development of customized approaches to improve the effectiveness of vaccination protocols, particularly in mild and severe immunodeficient patients.

Another aspect that has been considered is the potential antigenic competition between antigens intrinsic to LM and the ectopic vaccination antigen. In fact, Flickinger Jr. and collaborators, using LM expressing the colorectal tumor antigen Guanylate cyclase 2C (GUCY2C) (LM-GUCY2C), demonstrated that the immune response to immunodominant epitopes derived from LM proteins negatively impacts the projected response to the target GUCY2C peptides [91]. Immunodominant epitopes from vector constructs can overshadow the expected efficacy of the vaccine by limiting the immune response to the target peptides by several mechanisms: (a) competition for T cell activation (immunodominant epitopes are recognized more effectively by T cells. Also, the frequency of previously activated T cells is increased compared to the frequency of target antigen-specific T cells in a naïve T cell population); (b) bias on antigen presentation (immunodominant epitopes can lead to a bias in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I or class II peptide loading); (c) activation of regulatory circuits (strong activation of preceding T cell responses can lead to regulatory T cell activation, which may dampen the overall immune response to additional epitopes found in the target antigen). In this regard, it is important to consider that patients who have been in contact previously with LM may not optimally respond to the LM-based vaccines due to antigenic competition. Finally, efforts should be concentrated to engineer vaccine constructs to minimize the impact of immunodominance in live vector-based platforms.

Finally, although LM-based vaccines induce efficient and specific T-cell-mediated immune responses in the host, the potential pathogenic side effects related to this live vector limit its practical application. Therefore, different strategies to develop attenuated LM strains are in place at the moment. Interestingly enough, Listeria ivanovii (LI), a related bacterium with weaker immunogenicity compared to LM, shares several of the positive characteristics that make LM a good vaccine candidate, including cell-to-cell transfer, intracellular proliferation, and activation of dendritic cells. Liam and collaborators have recently modified LI, replacing the ivanolysin O gene (ilo) with the listeriolysin O (LLO) gene (hly) from LM [92]. These authors found that the recombinant LI strain still remained highly attenuated but exhibited improved invasive and proliferative activities on antigen-presenting cells that enriched their immunogenicity [92]. These data provided additional evidence that the invasive and proliferative capacity of the live vaccine vector is directly related to its immunogenicity and suggest that LI may also be considered as a potential vaccine vector.

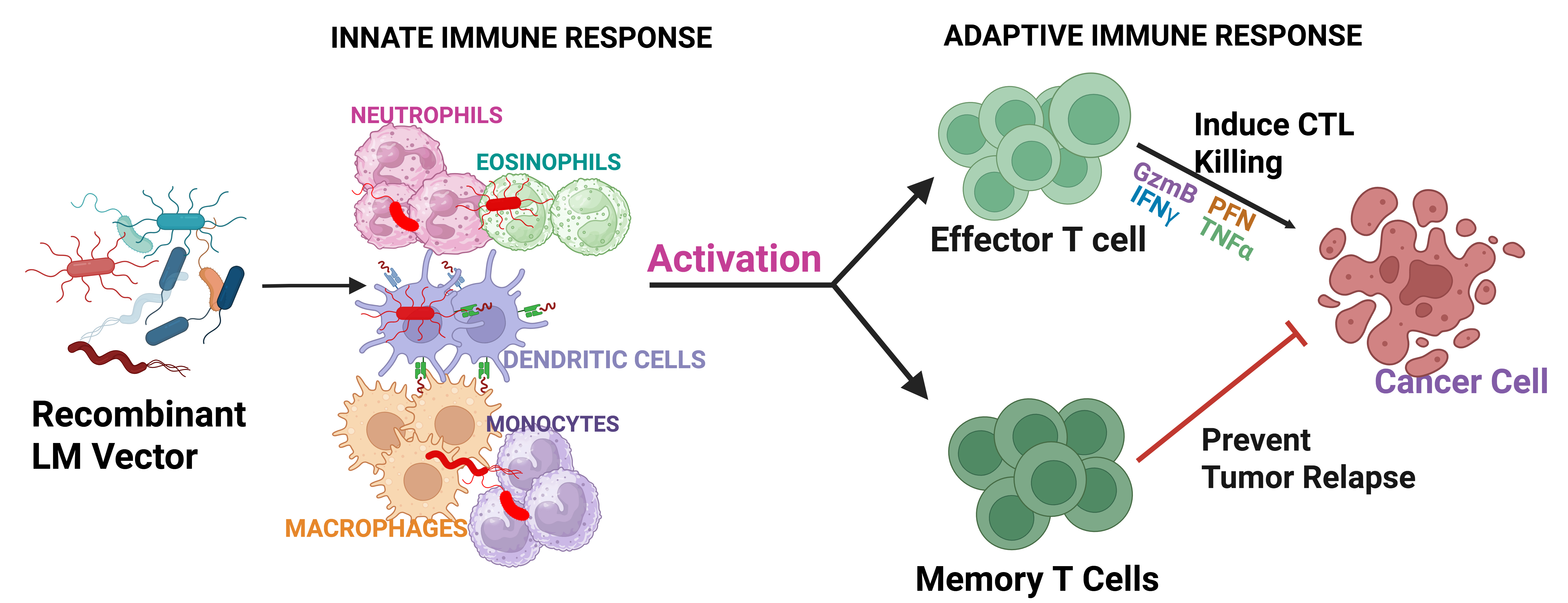

Listeria monocytogenes is a highly effective model for cancer vaccine development, primarily due to its capacity to activate innate and adaptive immune responses. By bridging these two arms of the immune system, LM-based vaccines not only target immediate tumor cells but also foster the formation of memory T cells, offering long-term protection against cancer recurrence (Fig. 5). Extended antigen presentation and systemic inflammation triggered by LM infection seem to enhance the development of memory T cells specific to the encoded antigens, fostering long-lasting immunity against target tumor cells. However, it is important to note that excessive immune reactions to LM can undermine the effectiveness of LM-based vaccines. The overstimulation of inflammatory pathways associated with LM infection may induce immunosuppression, thereby diminishing the overall therapeutic efficacy of the vaccine. Ongoing research continues to investigate the relationship between host genetic/immunological status and LM intrinsic characteristics as a means to improve the LM-based tumor immunotherapy platform. As research continues to explore the nuances of LM’s interaction with the immune system, it holds great promise for designing more effective cancer vaccines that harness these innate and adaptive responses for durable anti-tumor immunity.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Schematic of recombinant LM-based vaccine interaction with the immune system. The innate immune system recognizes and interacts with the recombinant Listeria monocytogenes (LM) as a defense mechanism against the pathogen. In this context, innate immune cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells initiate adaptive immune response by virtue of antigen presentation to T cells. Antigen-specific T lymphocytes proliferate and differentiate into effector T cells, inducing cytotoxic killing of the cancer cells. In addition, part of this repertoire became long-lasting memory T cells, which will be distributed throughout the body and responsible for preventing tumor reoccurrence (created with Biorender.com). CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte.

Conceptualization, ASO, MLL, MCR and GPA-M; writing—original draft preparation, ASO, MLL, MCR and GPA-M; writing—review and editing, ASO and GPA-M; project administration, GPA-M; funding acquisition, GPA-M. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to thank Tania Alves da Costa for her excellent administrative and technical support.

We are greatly indebted to Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP - Proc. No. 2018/25395-1; 2021/12143-7; 2021/13486-5; 2023/02577-5), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq - Proc. No. 308927/2019-2; 311122/2023-0; INCTiii 46543412014-2), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Ensino Superior (CAPES - Proc. No. 88887.919861/2023-00) for their ongoing support of the work carried out in our laboratory.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.