1 Department of Pathology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92037-0695, USA

Abstract

Lung cancer remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality due to its capacity for silent metastasis and the significant challenges in achieving effective treatment. Currently, targeted therapies and chemotherapies are the primary options for advanced or inoperable lung cancer; however, their efficacy is often undermined by the cancer’s ability to develop resistance through both genetic and non-genetic mechanisms. This review explores recent advances in understanding metabolic reprogramming in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), focusing on its critical role in cancer progression. NSCLC cells exhibit heterogeneous activation of metabolic pathways influenced by their oncogenic mutations. Notably, their metabolic phenotypes evolve in response to environmental stressors and therapeutic pressures. Moreover, NSCLC cells engage in metabolic crosstalk with their microenvironment to enhance survival, leveraging distinct metabolic adaptations at both primary and metastatic sites. Despite extensive preclinical studies evaluating novel therapeutic strategies targeting these metabolic pathways, many have failed in clinical trials due to severe adverse effects. This is because the targeted pathways are crucial not only for cancer cells but also for normal cellular functions. Future research must prioritize approaches that selectively disrupt cancer-specific metabolic regulation to improve therapeutic outcomes.

Keywords

- lung cancer

- metabolic reprogramming

- stress tolerance

- drug resistance

- metastasis

Lung cancer remains one of the most prevalent and lethal forms of cancer, contributing to approximately 1.8 million deaths annually [1]. Its exceptionally high mortality rate is primarily due to silent metastasis and significant challenges in treatment, underscoring the urgent need to develop novel therapeutic strategies. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of lung cancer. Furthermore, patients with advanced NSCLC are typically treated with targeted therapies or chemotherapies [2] (Table 1); however, therapeutic resistance remains a universal challenge at advanced stages. Most research on resistance mechanisms has focused on identifying genetic alterations [3, 4, 5], revealing that many patients lack detectable mutations, or for those with treatable mutations, second and third-line therapeutics that target these mutations show limited efficacy. These findings suggest that solely targeting genetic alterations is insufficient to overcome therapy resistance. This review explores various dimensions of metabolic reprogramming in lung cancer, which may provide critical insights into how lung cancer cells acquire metastatic phenotypes and develop resistance to therapies. Metabolic reprogramming is driven by a combination of genetic and non-genetic factors, including oncogenic mutations, post-translational modifications, and interactions between tumors and their microenvironment, all of which fuel cancer progression. We highlight recent studies on NSCLC metabolism, emphasizing three critical areas of disease progression: stress-induced metabolic reprogramming, metabolic reprogramming-mediated drug resistance, and metabolic reprogramming in metastasis.

| Category | Therapeutics |

| EGFR | Osimertinib with or without chemotherapy, dacomitinib, gefitinib, erlotinib, or afatinib |

| EGFR (exon 20) | Amivantamab |

| ALK | Alectinib, lorlatinib, crizotinib, ceritinib, or brigatinib |

| BRAF (V600E) | Dabrafenib and trametinib |

| ROS1 rearrangements | Entrectinib or crizotinib |

| NTRK fusions | Larotrectinib or entrectinib |

| RET fusions | Selpercatinib or pralsetinib |

| No targetable mutations* | Combination chemotherapy with platinum (cisplatin or carboplatin) and paclitaxel, gemcitabine, docetaxel, vinorelbine, irinotecan, protein-bound paclitaxel, or pemetrexed |

| Combination chemotherapy with monoclonal antibodies (bevacizumab, cetuximab, or necitumumab) | |

| Neuroendocrine | Everolimus |

| Target | Therapeutics |

| PD-L1 | Pembrolizumab with or without chemotherapy |

| Cemiplimab-rwlc with or without chemotherapy | |

| Atezolizumab with or without chemotherapy | |

| Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab plus chemotherapy | |

| PD-1 plus CTLA-4 | Nivolumab (anti-PD-1) plus ipilimumab (CTLA-4) |

| CTLA-4 | Durvalumab plus tremelimumab plus chemotherapy |

*In the United States, Kirsten Rat Sarcoma (KRAS) mutation is still included in “no targetable mutations”, because its clinical trial for sotorasib (KRAS inhibitor) as the first-line therapy is ongoing. NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; NTRK, neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase; RET, rearranged during transfection; PD, programmed death; CTLA, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated; ROS, reactive oxygen species; BRAF, B-Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine kinase.

NSCLC cells display distinct metabolic features early in tumorigenesis, which differ significantly from those of normal lung epithelium. These baseline metabolic alterations are often driven by specific oncogenic mutations. One of the most common mutations in NSCLC is in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Mutant EGFR with its downstream pathways, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and Myc, enhances glycolysis by upregulating glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes, such as glucose transporters (GLUTs), pyruvate kinases (PKs) and hexokinases (HKs) [6, 7, 8]. Beyond glycolysis, EGFR mutations (e.g., 19del, L858R, and T790M) promote monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) synthesis by phosphorylating stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1), an enzyme that converts saturated fatty acids (SFAs) into MUFAs, which are essential for lipid metabolism [9]. Similarly, Kristen Rat Sarcoma (KRAS) mutations—another prevalent driver in NSCLC—elevate MUFA levels by upregulating fatty acid synthase (FASN), a key enzyme in fatty acid synthesis [10]. This metabolic adaptation is critical because MUFAs inhibit ferroptosis by counteracting polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA)-mediated lipid peroxidation. In the PUFA-rich lung microenvironment, both EGFR and KRAS mutations promote MUFA synthesis to evade ferroptosis. Additionally, mutant KRAS enhances glycosphingolipid production through the upregulation of UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase (UGCG), an enzyme that generates glucosylceramide, the precursor for all glycosphingolipids [11]. Glycosphingolipids stabilize phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) in the lipid bilayer, a critical factor for KRAS membrane anchoring and activation of downstream signaling pathways. KRAS-mutant NSCLC cells also demonstrate elevated expression of glutaminase (GLS), an enzyme that converts glutamine into glutamate [12], reflecting a greater dependency on glutamine metabolism compared to wild-type cells. An in vivo study has confirmed increased glutamine uptake by KRAS-mutant NSCLC tumors relative to KRAS wild-type tumors [13]. However, targeting GLS in patients (e.g., in clinical trial NCT02771626) has shown limited efficacy, likely due to resistance mechanisms that circumvent glutamine depletion (discussed in the Nutrient Stress section) and toxicity in normal cells, which also rely on glutamine for essential functions.

Interestingly, oncogenic mutations can influence distinct metabolic pathways in

different cancer types. In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), EGFR

forms a complex with a glutamine transporter Alanine, Serine, Cysteine

Transporter 2 (ASCT2), enhancing glutamine uptake and glutathione production

[14]. This adaptation strengthens the ability of HNSCC cells to counteract

reactive oxygen species (ROS). In glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), similar to

NSCLC, EGFR drives glycolysis through the upregulation of Myc transcription [15]

and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation [16]. However, EGFR also

enhances glutamate metabolism in GBM [17]. Via the MEK/extracellular

signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/E-like transcription factor 1 (ELK1) signaling

axis, EGFR activates the transcription of glutamate dehydrogenase 1 (GDH1), an

enzyme that converts glutamate to

These observations highlight that oncogenic mutations can drive distinct metabolic reprogramming across cancer types, likely influenced by factors such as tissue-specific microenvironments and cellular origins. This underscores the notion that genetic alterations alone do not dictate metabolic adaptations, but rather, their effects are shaped by the context in which they occur.

Metabolic reprogramming is a vital ability of tumors, enabling them to adapt to various environmental changes and stressors, such as nutrient stress, reactive oxygen species, and hypoxia. Thus, it is considered the metabolic flexibility of the cancer cells is what makes cancer cells stress tolerant [23, 24, 25]. Here, we summarize metabolic reprogramming-mediated stress tolerance in lung cancer.

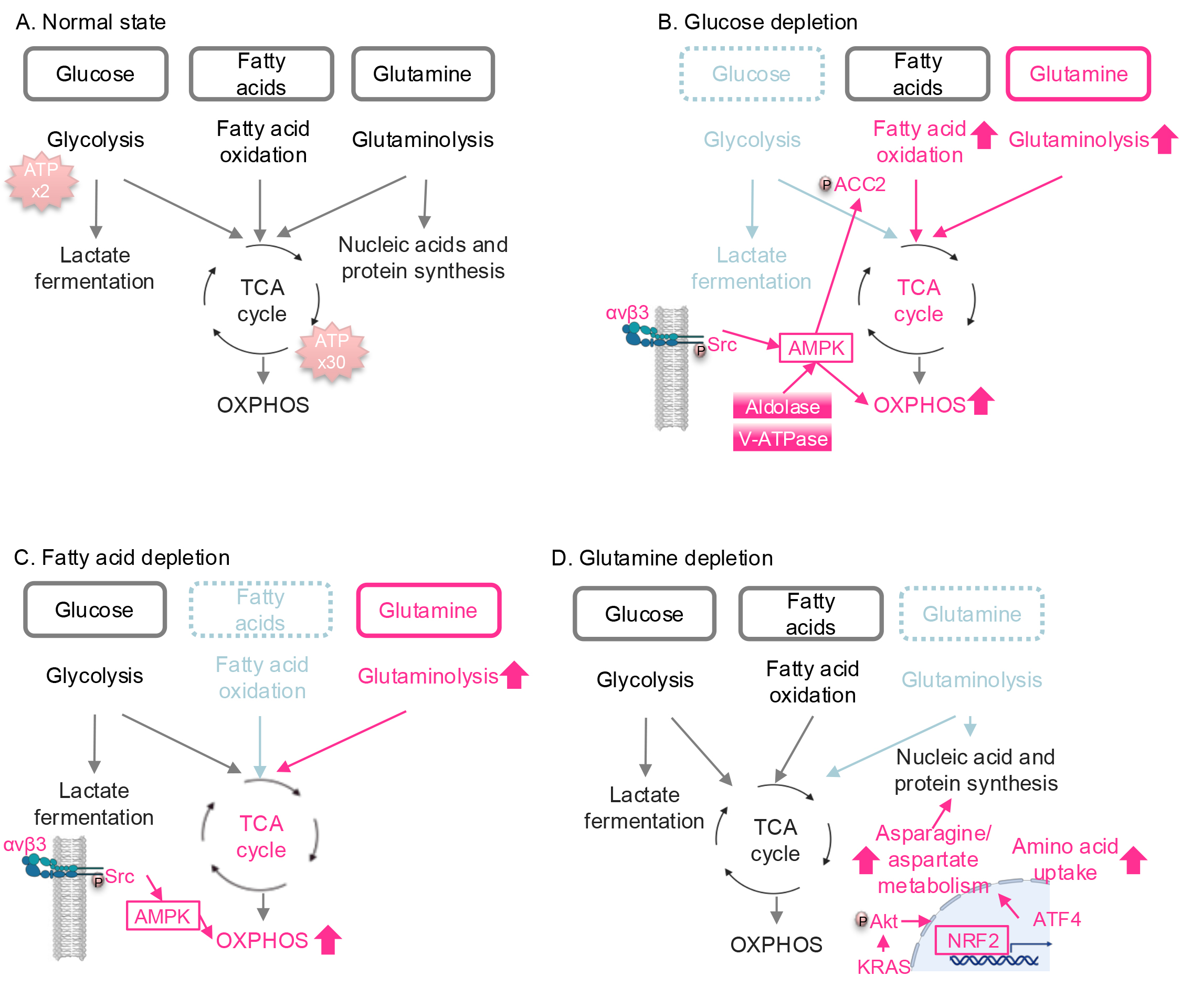

Cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production is primarily sustained through

two pathways (Fig. 1A): (1) the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS),

fueled by glycolysis, fatty acid metabolism, and glutamine/glutamate metabolism

(reviewed in [26]), and (2) glycolysis followed by lactate fermentation (reviewed

in [27]). While the TCA cycle and OXPHOS provide a higher ATP yield, they require

oxygen. Conversely, lactate fermentation is faster and oxygen-independent but

produces significantly less ATP per molecule of glucose. Solid tumors frequently

face energy production challenges due to nutrient deficiencies in poorly

vascularized or highly metabolically active regions. Many cancer cells

preferentially use glycolysis/lactate fermentation even under normoxic conditions

(Warburg effect) [28]. However, in the case of glucose or serum deprivation,

NSCLC cells phosphorylate adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase

(AMPK) to activate the TCA cycle and OXPHOS as a method of producing ATP instead

of glycolysis (Fig. 1B,C) [29, 30]. Mechanistically, glucose or serum depletion

activates AMPK via either integrin

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Nutrient stress-induced metabolic reprogramming in lung cancer.

(A) Major pathways involved in ATP production. Glucose, fatty acids, and

glutamine are the major carbon sources for energy production. (B) Metabolic

reprogramming under glucose depletion. When glucose is deprived, the TCA cycle

and OXPHOS are activated by integrin

In addition to serving as a major carbon source for the TCA cycle, glutamine is

essential for nucleotide synthesis, the production of various amino acids

required for protein synthesis (reviewed in [35]), and reactive oxygen species

(ROS) inhibition, as discussed in the next section. While NSCLC cells,

particularly those with KRAS mutations, rely heavily on glutamine

metabolism [12, 13], they activate adaptive mechanisms to resist glutamine

depletion. Under glutamine-deprived conditions, mutant KRAS enhances asparagine

and aspartate metabolism via the Akt/NRF2 axis (Fig. 1D) [22]. Activation of the

NRF2 transcription factor upregulates activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4),

which in turn increases the transcription of ASNS, leading to enhanced

asparagine synthesis. Additionally, ATF4 promotes the uptake of extracellular

amino acids, helping to replenish the amino acid pool reduced by glutamine

depletion. Furthermore, when glutaminase (GLS), an enzyme responsible for

converting glutamine into glutamate, is inhibited, NSCLC cells compensate by

upregulating glutamic pyruvic transaminase 2 (GPT2), an enzyme that catalyzes the

reversible transamination of alanine and

Nutrient stress affects not only cancer cells but also immune cells that are

forced to compete for nutrients with cancer cells in the microenvironment. When

tumor cells outcompete for glucose, glycolysis is inhibited in T cells, leading

to attenuation of interferon gamma (IFN

ROS are unstable and highly reactive derivatives of partially reduced oxygen. As secondary messengers, they play a critical role in cell signaling and are essential for various biological processes in both normal and cancer cells. However, elevated levels of ROS can lead to damage to cellular organelles, membranes, and nucleic acids, ultimately triggering apoptosis. To ensure cellular function and survival, cancer cells have developed mechanisms to regulate redox homeostasis.

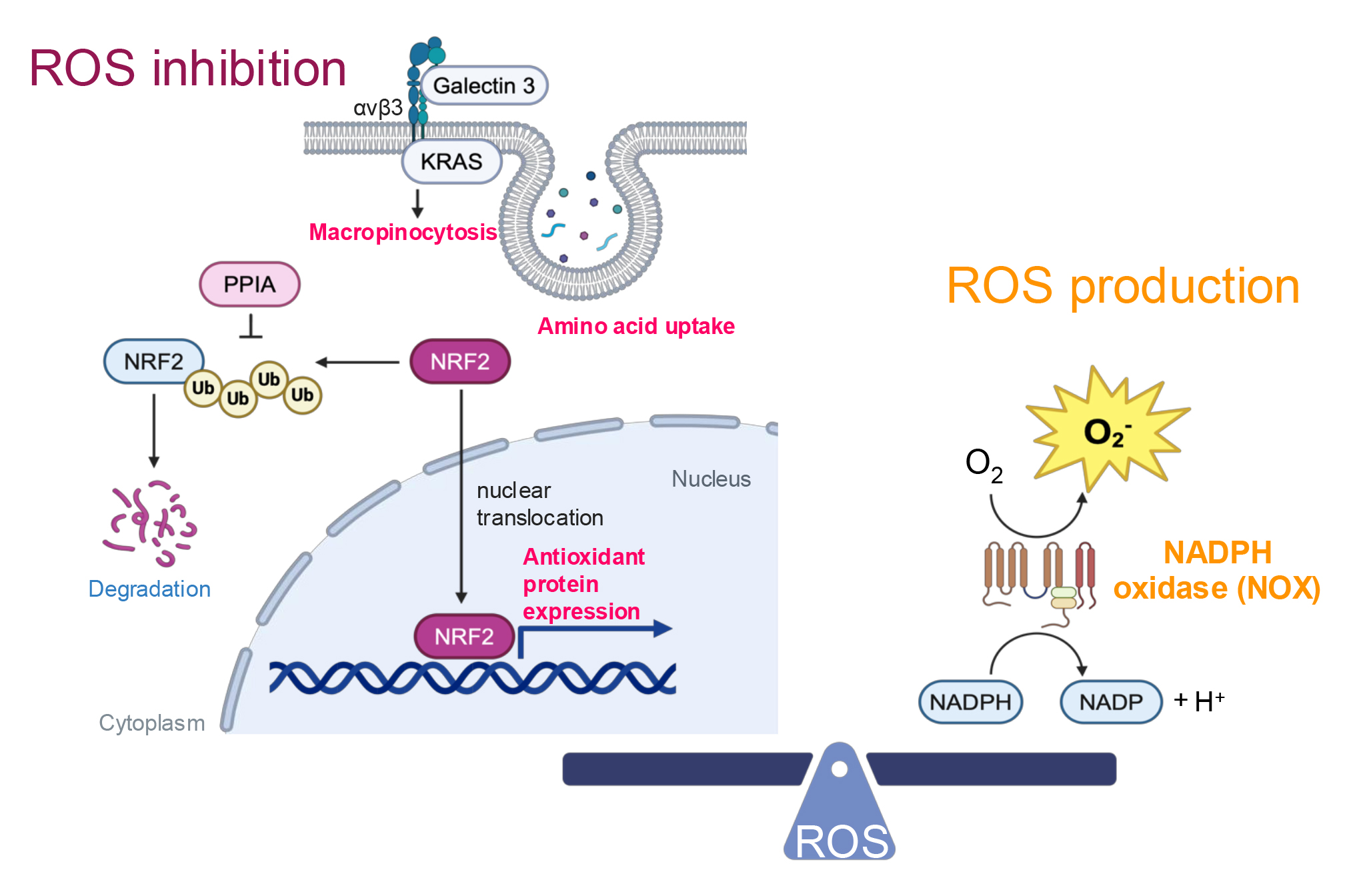

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) is a key transcription factor

that regulates enzymes critical for maintaining redox homeostasis. These include

heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and catalase, which reduce ROS using nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and the glutathione (GSH)/oxidized glutathione

(GSSG) system, as well as glutamate–cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC),

glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit (GCLM), and glutamine synthetase (GS),

which are essential for GSH/GSSG synthesis (reviewed in [39]). To combat

excessive ROS, NSCLC cells upregulate NRF2 (Fig. 2) [40, 41, 42]. Notably, elevated

NRF2 expression is associated with poor prognosis in lung cancer patients [41]

and has been shown to promote metastasis in NSCLC in vivo [43].

Consistent with these findings, NSCLC cells resistant to radiation therapy—a

source of excess ROS—exhibit increased nuclear NRF2 expression compared to

radiation-sensitive cells [40]. Targeting peptidylprolyl isomerase A (PPIA), a

protein that stabilizes NRF2, has been demonstrated to inhibit lung cancer growth

[42], highlighting a potential therapeutic strategy. In addition,

KRAS-mutant NSCLC cells employ macropinocytosis as a mechanism to

mitigate ROS by enhancing the uptake of amino acids necessary for ROS inhibition

[44, 45]. This process is driven by a complex formed on the cell surface between

KRAS, integrin

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Redox homeostasis. ROS inhibition is facilitated by integrin

On the other hand, excessive activation of NRF2 has been reported to induce reductive stress in lung cancer [46], highlighting the critical need for maintaining redox balance during lung cancer progression. To generate the necessary levels of ROS, NSCLC cells employ NADPH oxidase (NOX) (Fig. 2) [47]. NOX homologs produce superoxide, and the expression of NOX4 is positively correlated with NSCLC progression, including metastasis in patients [47]. Supporting this finding, additional research has demonstrated that NOX1 promotes the migration of NSCLC cells [48]. To maintain healthy ROS levels, NSCLC cells possess feedback mechanisms. Specifically, NOX4 enhances the PPP and glutaminolysis to produce NADPH and GSH/GSSG respectively [49], thereby facilitating ROS metabolism.

Hypoxia is a common stressor in cancer. Hypoxic lung cancer tissues may contain less than half the oxygen levels of their healthy counterpart [50]. Similarly to nutrient deprivation conditions, tumors that exceed a certain size without adequate vascular support can develop hypoxic regions. Tumors may also experience hypoxia in individuals with systemic hypoxic conditions [50].

Hypoxia in NSCLC cells leads to increased nuclear levels of hypoxia-inducible

factor-1

In NSCLC, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) contribute to the development of a

hypoxic environment [54]. Unlike bone marrow-derived macrophages, TAMs in lung

cancer exhibit high levels of phosphorylated AMPK and peroxisome proliferative

activated receptor, gamma, coactivator 1

Most patients with distant metastases or unresectable tumors are treated with therapeutic interventions (Table 1). Traditionally, chemotherapy has been the primary option; however, an increasing number of targeted therapies have been approved over the past few decades. Nevertheless, the emergence of therapeutic resistance remains an inevitable challenge. Research on resistance mechanisms has largely focused on identifying genetic alterations [4, 56, 57], but targeting these mutations and amplifications has only extended patient survival by a few months to years [58, 59]. This highlights that targeting genetic changes alone is insufficient to fully overcome therapy resistance. Notably, recent studies indicate that non-genetic factors, including metabolic reprogramming, play a significant role in drug resistance. Here, we summarize the metabolic reprogramming induced by major therapies used in the treatment of lung cancer.

Chemotherapies are drugs that inhibit mitosis or induce DNA damage to eliminate rapidly dividing cancer cells. Developed in the early 1940s, they introduced a novel approach to targeting cancer cell growth and proliferation. Despite advancements in targeted therapies, chemotherapy remains a cornerstone treatment for lung cancer types lacking druggable targets and for those that have developed resistance to targeted therapies [2].

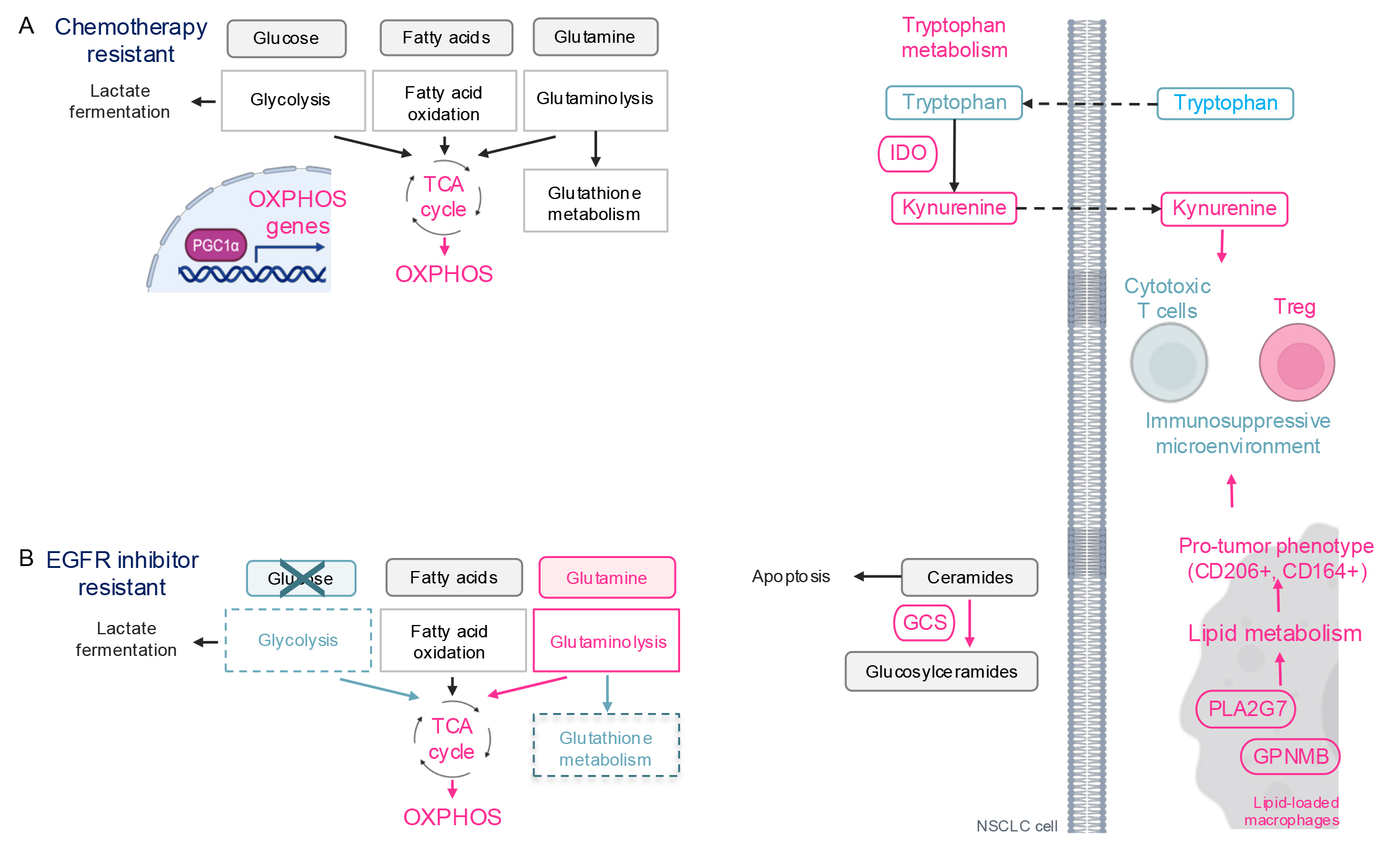

For advanced lung cancer patients without targetable gene alterations, including

those with KRAS mutations—where KRAS inhibitors are still under

investigation for first-line treatment—combination chemotherapy regimens

typically incorporate platinum-based agents, such as cisplatin. Studies

demonstrated upregulation of OXPHOS in cisplatin- and irinotecan-resistant

KRAS- and Neuroblastoma RAS (NRAS)-mutant NSCLC cells (Fig. 3A)

[60, 61]. Similarly, other researchers have reported increased oxygen consumption

and ATP production, indicative of OXPHOS activation, in cisplatin-resistant

Kras-mutant murine NSCLC cells [62]. Mechanistically, cisplatin

increases expression of PGC1

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Therapy-induced metabolic reprogramming in lung cancer. (A)

Schematic of metabolic reprogramming in chemotherapy resistant cells. OXPHOS is

activated via PGC1

Cisplatin has also been shown to alter the tumor microenvironment by reprogramming tryptophan (TRP) metabolism in lung cancer cells (Fig. 3A) [62]. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), an enzyme in the tryptophan pathway, catabolizes tryptophan, generating immunosuppressive metabolites such as kynurenine (KN) and quinolinate. In cisplatin-resistant Kras-mutant murine NSCLC cells, there is an increase in tryptophan uptake, upregulation of IDO, and elevated extracellular kynurenine levels compared to cisplatin-naïve cells. Kynurenine drives the differentiation of naïve T cells into regulatory T-cells (T-reg), promoting an immunosuppressive phenotype. Indeed, cisplatin-resistant allografts are enriched with CD4+ T-reg cells. Similarly, in NSCLC patients resistant to pemetrexed—another chemotherapeutic agent—serum tryptophan levels decrease and kynurenine levels increase, compared to patients sensitive to pemetrexed [65], suggesting that the serum tryptophan/kynurenine ratio could serve as a biomarker for chemotherapy response.

Currently, there are three generations of EGFR inhibitors approved for treating EGFR mutant NSCLC: The first-generation EGFR inhibitors against the L858R and Del 19 (e.g., gefitinib and erlotinib); the second-generation inhibitors against T790M and wild type EGFR (e.g., afatinib); the third-generation inhibitors selectively against mutant EGFR including T790M (e.g., osimertinib). Osimertinib, approved in 2015, is currently the preferred EGFR inhibitor due to its high efficacy especially the ability to penetrate the brain. Despite these developments, patients with advanced NSCLC inevitably develop resistance to EGFR inhibitors, making it critical to understand how cancer cells overcome EGFR inhibition.

Metabolic reprogramming in cells resistant to EGFR inhibitors in common involves the downregulation of glycolysis and the activation of OXPHOS (Fig. 3B) [66, 67, 68, 69, 70]. This phenomenon likely occurs because EGFR phosphorylates and activates a glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) [71, 72] and upregulates the expression of another glycolytic enzyme HK2 [6, 72], promoting aerobic glycolysis, a key energy source for cancer cells. Consequently, cells shift their energy production to OXPHOS to resist EGFR inhibition. Glucose uptake, a primary carbon source for the TCA cycle and OXPHOS, is reduced in cells resistant to gefitinib, erlotinib, and osimertinib [68, 73], while glutamine metabolism becomes upregulated [66, 67, 69]. This suggests that EGFR inhibitor-resistant cells switch their carbon source for OXPHOS from glucose to glutamine. Additionally, erlotinib-resistant cells show downregulation of the GSH/GSSG metabolism pathway, which is critical for redox homeostasis [74]. This may be due to the diversion of glutamine, a major carbon source for GSH/GSSG metabolism, to support the TCA cycle. Consequently, EGFR inhibitor-resistant cells are sensitive to OXPHOS inhibition [70] and glutaminase inhibitors, which target glutamine catabolism to glutamate, feeding into the TCA cycle [67, 75]. However, the clinical application of OXPHOS and glutaminase inhibitors as cancer therapies has been limited due to toxicity, as these metabolic pathways are vital for normal cell survival (discussed in detail in the section on Therapeutics Targeting Cancer Metabolism). Therefore, it is crucial to understand and target the unique regulation of OXPHOS and glutamine metabolism in cancer cells for effective therapy.

In addition to energy metabolism, sphingolipid metabolism is also altered in osimertinib-resistant cells. Recent research has identified glucosylceramide synthase (GCS) as a promising therapeutic target for overcoming osimertinib resistance (Fig. 3B) [76]. Ceramides promote apoptosis through activation of both the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways. To modulate apoptosis, ceramides are converted to glucosylceramides by GCS. The study demonstrated that osimertinib-resistant EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells exhibit elevated GCS levels. Treatment with 1-phenyl-2-decanoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol (PDMP), a ceramide analog GCS inhibitor, induced apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cells in vitro and suppressed osimertinib-resistant tumor growth in vivo. Similarly, GCS inhibition has been shown to overcome drug resistance in other cancer types [77, 78, 79].

EGFR inhibitors influence the metabolism not only of cancer cells but also of those in the tumor microenvironment. TAMs are among the most extensively studied immune cells in lung cancer. Recent findings reveal that EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells secrete surfactant and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factors (GM-CSF), promoting lipid metabolism and cholesterol efflux from tumor-associated alveolar macrophages [80]. The cholesterol obtained from these macrophages enhances EGFR phosphorylation in NSCLC cells. Similarly, in osimertinib-treated patients, a subset of TAMs exhibits a lipid-associated macrophage phenotype characterized by increased lipid metabolism through the upregulation of genes such as GPNMB and PLA2G7 [81]. These lipid-associated macrophages also express immunosuppressive markers, including CD206 and CD163, and are associated with elevated levels of T regulatory (Treg) cells, suggesting the establishment of an immunosuppressive microenvironment that may contribute to osimertinib resistance.

Interestingly, despite the differences in the initial oncogenic mutations in patients treated with chemotherapies (commonly targeting KRAS mutations) versus EGFR inhibitors (targeting EGFR mutations), NSCLC cells develop a similar metabolic alteration during resistance: a shift to TCA cycle/OXPHOS. These observations suggest that metabolic reprogramming can occur independently of the original oncogenic mutations, underscoring its potential as a universal therapeutic target in NSCLC.

Compared to chemotherapies and EGFR inhibitors, the metabolic reprogramming induced by other targeted therapies remains underexplored. Here, we provide a summary of the currently available research in this area (Table 2, Ref. [82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88]).

| Therapeutics | Targets | Metabolic reprogramming in resistant NSCLC | References |

| Alectinib | ALK | Weight gain. | [82] |

| Lorlatinib | Weight gain, hypercholesterolemia, hyper triglyceridemia. | [83] | |

| Crizotinib | ALK/ROS1 | Upregulation of glycolysis. | [84] |

| Vemurafenib | BRAF | Upregulation of PGE2 and TCA cycle. Downregulation of glycolysis and glutamine metabolism. | [85] |

| Dabrafenib/trametinib | BRAF/MEK | GPX4 dependency. | [86] |

| Trametinib | MEK | Upregulation of TCA cycle and OXPHOS. Downregulation of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. | [87, 88] |

| Selumetinib | [87] |

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4.

ICIs block checkpoint proteins, the immunosuppressive mechanism of cancer cells. Numbers of ICIs (e.g., nivolumab) have been approved for lung cancer therapy in the last decade. However, the efficacy of ICIs remains limited compared to other targeted therapies.

To improve efficacy of ICIs, various combination therapeutic approaches,

including the combination of ICIs and glutamine metabolism inhibition by a

glutaminase inhibitor, teleglenastat, have been tested. Preclinical studies

indicated enhancement of ICI efficacy by glutaminase inhibition [89, 90].

Consequently, the teleglenastat and ICI combination has been tested in a clinical

trial for multiple cancer types including lung cancer (NCT02771626). However, the

combination therapies have thus far proven unsuccessful. A recent study suggests

that this may be due to the role of glutamine in immune cells [91]. In the lung

cancer microenvironment, an ICI, nivolumab, activates CD8+ T cells via activation

of the glutamine pathway which enhances cytotoxic molecule secretion such as

IFN

Metastasis is a major cause of mortality in lung cancer, with 60–70% of patients presenting with metastasis at diagnosis [1]. Distant metastases drastically reduce patient survival, with 5-year survival rates dropping to 9% for metastatic NSCLC and 3% for metastatic small cell lung cancer (SCLC), compared to 65% and 30% for localized case (Table 3) [1]. Treatment options for metastatic NSCLC and SCLC include targeted therapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy, yet resistance remains a pervasive issue. Understanding how cancer cells escape the primary tumor, invade distant sites, and establish metastases is essential. Emerging evidence suggests that metabolic reprogramming plays a key role in helping cancer cells adapt to the harsh conditions of metastasis. Identifying and targeting these metabolic shifts could reveal new therapeutic approaches focused on metabolic adaptations in lung cancer metastasis.

| Metastasis | NSCLC | SCLC |

| Localized disease | 65% | 30% |

| Regional metastases | 37% | 18% |

| Distant metastases | 9% | 3% |

NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

The brain is a common site of metastasis in lung cancer, affecting approximately 20% of patients at diagnosis [93, 94]. Even stage 1 patients have a 6% risk of developing brain metastases during the course of treatment [95]. Prognosis is generally poor for those with brain metastases compared to other metastatic sites, with survival rates declining further in cases of multiple metastases [96, 97, 98].

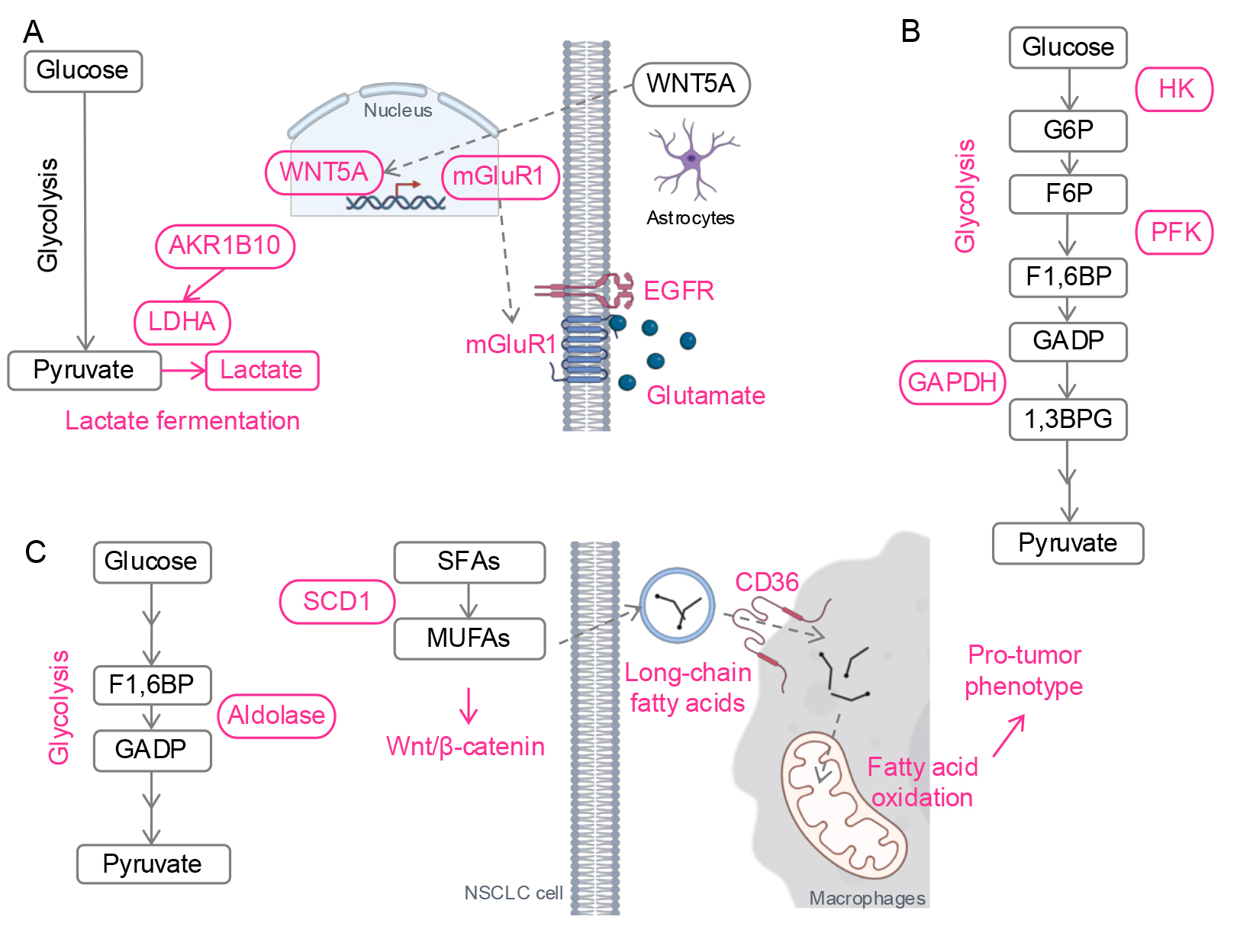

A recent single cell RNA-sequencing study of lung cancer patient tissues found increased expression of Warburg effect genes, including lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), and decreased lipid metabolism genes in brain metastases compared to primary lung tumors (Fig. 4A) [99]. This aligns with findings from an EGFR-mutant NSCLC preclinical model, which showed higher lactate and pyruvate levels in brain-metastatic PC9 cells than in parental PC9 cells [100]. Mechanistically, aldo-keto reductase family 1 B10 (AKR1B10), a reductase involved in a cyto-detoxification in the intestines, enhanced the Warburg effect by upregulating LDHA in brain-metastatic PC9 cells, leading to resistance against pemetrexed, a chemotherapy administered with osimertinib for advanced EGFR-mutant lung cancer.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Metabolic reprogramming in metastases. (A) Schematic of metabolic reprogramming in CNS metastasis. Lactate fermentation is activated by AKR1B10. Wnt5A from astrocytes promotes mGluR1 transcription. With the enriched glutamate in the brain microenvironment, mGluR1 stabilizes EGFR. (B) Schematic of metabolic reprogramming in lymph node metastasis. Glycolysis is enhanced by activation of glycolytic enzymes. (C) Schematic of metabolic reprogramming in liver metastasis. Glycolysis and lipid metabolism are upregulated. Fatty acids from NSCLC cells promote a pro-tumor phenotype of macrophages. Red, upregulated. CNS, central nervous system; HK, hexokinase; G6P, glucose 6-phosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; PFK, phosphofructokinase; F1,6BP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; GADP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; 1,3BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase A; AKR1B10, aldo-keto reductase 1B; mGluR1, metabotropic glutamate receptor 1; SFAs, saturated fatty acids; SCD1, stearoyl-CoA Desaturase-1; MUFAs, monounsaturated fatty acids; Wnt5A, wingless-type protein 5a. Created with Microsoft Powerpoint and BioRender (https://app.biorender.com/).

Lung cancer cells also exploit the brain’s unique microenvironment. Astrocyte-derived Wnt-5a induces metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1) expression in lung cancer cells, stabilizing EGFR through direct interaction with EGFR and glutamate, which is abundant in the brain (Fig. 4A) [101]. Inhibition of mGluR1 suppressed lung cancer growth in the brain in vivo. mGluR1 has also been implicated as a therapeutic target in other cancers, such as breast cancer and melanoma [102, 103]. A recent preclinical study proposed a novel therapy using 211At-AITM, a small-molecule alpha-emitting radiopharmaceutical, to target and eradicate mGluR1-positive tumors across multiple models [104].

Lipid-associated macrophages, a phenotype induced by osimertinib (referred in Metabolic Reprogramming-mediated Drug Resistance), have also been identified in CNS metastases. As noted earlier, lipid-associated or lipid-loaded macrophages play a significant role in promoting cancer progression [105, 106]. During metastasis, these macrophages not only enhance cancer cell migration [107], but also facilitate the rearrangement of the extracellular matrix at metastasis sites, thereby supporting the establishment and progression of metastatic tumors [108]. Although it is still not clear how exactly lipid-associated macrophages contribute to CNS metastasis of NSCLC, these findings suggest that lipid-associated macrophages may contribute to osimertinib-mediated CNS metastasis, one of the most challenging outcomes in osimertinib-resistant patients [81].

Similar to the CNS, upregulated glycolysis has been linked to lymph node metastasis in KRAS-driven NSCLC (Fig. 4B) [109]. In this in vivo study, antioxidants stabilized a transcription factor BTB domain and CNC homolog 1 (BACH1) by reducing free heme levels. BACH1 then promoted the transcription of glycolytic enzymes HK2 and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), driving glycolysis-mediated lymph node metastasis. Another study further supports this, showing elevated levels of the glycolytic enzyme phosphofructokinase (PFK) in patients with lymph node metastases compared to those without [110].

Similar to CNS and lymph node metastasis, upregulation of glycolysis has also been reported in liver metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma in vivo (Fig. 4C) [111]. In this study, transfer RNA-derived fragment (tRF) sequencing from patient tissues identified a tRF, tRF-Val-CAC-024, which binds to a glycolytic enzyme aldolase A (ALDOA). This interaction promotes the formation of ALDOA tetramers, enhancing enzyme activity and glycolysis. An inhibitor of tRF-Val-CAC-024 attenuated glycolysis and suppressed liver metastasis in vivo. Given that upregulation of glycolysis in other metastatic sites [99, 100, 109], targeting tRF-Val-CAC-024 may offer a therapeutic strategy to inhibit lung cancer metastasis across multiple sites.

Beyond glycolysis, the lipid metabolism enzyme SCD1 has been shown to be

essential for liver metastasis of NSCLC (Fig. 4C) [112]. SCD1 catalyzes the

conversion of saturated fatty acids into unsaturated fatty acids, driving

triglyceride synthesis. In this study, SCD1 promoted migration and metastasis of

EGFR-mutant NSCLC cells through activation of Wnt/

Lipid metabolism plays a pivotal role in shaping the phenotype of TAMs. Enhanced lipid metabolism drives the transition of macrophages toward a pro-tumor phenotype (reviewed in [115]). In liver metastasis, NSCLC cells secrete long-chain fatty acids, which are transferred to macrophages in the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 4C) [116]. This process is facilitated by CD36, fatty acid translocase expressed on macrophages, which promotes fatty acid uptake and metabolic reprogramming. The increased fatty acid uptake fuel fatty acid oxidation and induces a pro-tumor phenotype of the macrophages.

As summarized, glycolysis upregulation is linked to metastasis in lung cancer across multiple patients and in vivo studies [99, 111, 117]. This observation has led to the development of imaging technologies that exploit increased glucose uptake by metastases. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), a glucose analog, enters cells via glucose transporters and is phosphorylated by hexokinases into FDG-6-phosphate, which accumulates intracellularly. FDG-positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) imaging detects cancer by measuring FDG accumulation. While FDG-PET/CT offers little advantage over conventional imaging for detecting primary tumors, it is more sensitive for identifying metastases [118, 119, 120, 121]. Bone metastases initially infiltrate red marrow without affecting cortical bone, limiting the sensitivity of conventional bone scintigraphy, which relies on phosphate metabolism. In contrast, FDG-PET/CT directly images tumor cells, enabling earlier detection of bone metastasis during the marrow phase [121]. Early detection of adrenal gland metastases is crucial since resection of adrenal oligometastases can improve long-term disease-free survival in NSCLC patients [122]. However, distinguishing metastatic lesions from benign adrenal abnormalities on CT scans is challenging. FDG-PET/CT improves sensitivity and specificity, facilitating earlier detection and differentiation of benign and metastatic adrenal lesions [121]. Additionally, total lesion glycolysis measurement via FDG-PET/CT have proven effective in identifying metastatic lobar lymph nodes, even at the micrometastatic stage [118].

Given the importance of metabolic reprogramming in stress resistance and metastasis during cancer progression, numerous studies have sought to inhibit metastasis and overcome drug resistance by targeting cancer metabolism (Table 4). However, no drugs directly targeting metabolic pathways have been approved for cancer therapy, primarily due to the high ratio of adverse effects to efficacy. This limitation arises because many of the metabolic pathways exploited by cancer cells are also essential for the survival and function of normal cells. In this section, we summarize metabolism-targeting drugs that have been tested in clinical trials for NSCLC.

| Drug | Target | Clinical trials |

| IACS10759 | OXPHOS (mitochondrial electron transport chain complex l) | NCT02882321 |

| Telaglenastat | Glutamine metabolism (glutaminase) | NCT03428217 |

| IACS6274 | Glutamine metabolism (glutaminase) | NCT05039801 |

| 2-Deoxy-D-glucose | Glycolysis | NCT00096707 |

| Denifanstat | Fatty acid synthesis (fatty acid synthase) | NCT02223247, NCT03808558 |

| Epacadostat | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 | NCT03322540 |

Given that OXPHOS activation is a hallmark of NSCLC cells resistant to chemotherapies and EGFR inhibitors—two of the most commonly used treatment modalities—numerous OXPHOS inhibitors have been developed and tested in preclinical studies [123, 124, 125]. Among these, IACS10759, an inhibitor targeting mitochondrial electron transport chain complex l, was evaluated in a clinical trial for leukemia and solid tumors, including lung cancer (NCT02882321). In preclinical models of NSCLC, IACS10759 successfully overcame gefitinib resistance [126]. However, the clinical development was discontinued due to adverse effects, including neurotoxicity and elevated blood lactate levels [127]. This outcome also raised concerns about the development of other complex l inhibitors. The caution is understandable, as one of the most well-known complex l inhibitors, rotenone, was approved as a piscicide and an insecticide, and has been banned as an insecticide in multiple countries, including U.S., EU, UK, and Canada, due to its acute toxicity to mammals.

Glutaminase inhibitors have demonstrated promising anti-tumor activity in preclinical studies across various tumor models, including NSCLC [67, 128, 129]. Telaglenastat, a glutaminase-C inhibitor, underwent clinical evaluation in multiple trials. However, the CANTATA trial (NCT03428217) failed to show improved progression-free survival (PFS) [130], leading to the discontinuation of teleglenastat and the closure of its developing company. Despite this setback, the trial did not raise broader concerns about the viability of glutaminase inhibitors. A clinical trial for another GLS inhibitor, IACS6274 (a GLS1 inhibitor) is currently ongoing (NCT05039801).

2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) is a glucose analog that competitively inhibits glycolysis. Its 2-hydroxyl group replacement with hydrogen prevents further progression through the glycolysis pathway. Like other metabolic inhibitors, 2-DG has shown strong anti-tumor effect in preclinical studies across various cancer models, including NSCLC [131, 132, 133]. However, a phase1/2 trial (NCT00096707) revealed dose-limiting toxicities, such as glucopenia and QTc prolongation, allowing tolerability only at lower doses [134]. Since the trial’s publication in 2013, no follow-up clinical trials have been initiated.

Denifanstat (TVB-2640), an FASN inhibitor, has been evaluated in clinical trials for various cancers, including NSCLC. A phase 1 trial (NCT02223247) demonstrated promising anti-tumor effects in KRAS-mutant NSCLC, ovarian, and breast cancers with manageable side effects [135]. These findings align with preclinical data showing that KRAS mutations upregulate FASN in NSCLC, as discussed earlier [10]. Further clinical trials for denifanstat in multiple cancers, including KRAS-mutant NSCLC (NCT03808558), have been initiated.

As discussed in the Chemotherapy section, the microenvironment of chemo-resistant NSCLC is characterized by elevated KN and depleted TRP levels, suppressing cytotoxic T-cell activity. Consequently, a combination therapy with epacadostat (targeting IDO) plus pembrolizumab (PD-L1 inhibitor) has been tested in a phase 2 study. The objective was to normalize KN levels and sensitize NSCLC to ICIs (NCT03322540). However, the combination therapy failed to demonstrate improved therapeutic efficacy [136].

Metabolic reprogramming is a crucial adaptive mechanism that allows lung cancer cells to survive and become more aggressive under cellular stress. This process involves not only cancer cells but also the tumor microenvironment, which co-evolves during cancer progression. As health professionals and scientists, our understanding of cancer metabolic reprogramming has advanced significantly in recent years. Innovations in imaging technologies, such as FDG-PET/CT, highlight the potential to exploit metabolic traits for more precise detection of metastases, paving the way for earlier diagnoses and improved treatment strategies. Despite this progress, selectively targeting cancer metabolism without damaging normal cells remains a significant challenge. Future research must prioritize uncovering cancer-specific drivers of metabolic reprogramming to inform the development of more effective therapies. These may include combination strategies integrating targeted treatments with agents designed to reverse cancer-specific metabolic adaptations.

BPP, RAC, JPR and HIW made substantial contributions to conception and design of the manuscript, have been involved in drafting the manuscript and reviewing it critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

HIW was funded by NIH, grant number K01OD030513.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.