1 Department of Cardiology, Chongqing University Central Hospital (Chongqing Emergency Medical Center), Chongqing University, 400014 Chongqing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) remain the leading cause of global mortality, highlighting the urgent need for the identification of novel biomarkers and the development of therapeutic approaches to improve patient outcomes. Despite great progress in CVD diagnosis, treatment, and predicting risk, current methods fall short of effectively reducing its prevalence. Recently, bone morphogenetic protein 10 (BMP10), a cardiac-specific growth factor with a role in cardiac development and vascular homeostasis, has emerged as a potential biomarker and therapeutic target in CVD. While studies have demonstrated BMP10’s diagnostic potential in atrial fibrillation (AF), its precise role across the broader CVD landscape remains poorly understood. We review the current knowledge of BMP10’s involvement across a spectrum of cardiovascular conditions, including AF, heart failure, myocardial infarction, pulmonary arterial hypertension, dilated cardiomyopathy, and diabetic cardiomyopathy. This analysis provides an in-depth examination of the mechanisms through which BMP10 may influence CVD progression and highlights its potential utility as a diagnostic and therapeutic target.

Keywords

- BMP10

- cardiovascular disease

- biomarker

- vascular homeostasis

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), which encompasses a spectrum of conditions affecting the heart and vascular system such as stroke, congenital heart disease, arrhythmias, atherosclerosis, coronary heart disease, and heart failure (HF), is the preeminent cause of mortality and disability worldwide [1, 2, 3]. These diseases drastically reduce patients’ quality of life and impose considerable health and economic burden on healthcare systems globally [4]. During various pathological conditions, cardiomyocytes secrete various bioactive substances, including N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and A-type natriuretic peptide (ANP), which are critical biomarkers for diagnosing, evaluating treatment efficacy, and predicting prognosis in CVD. These natriuretic peptides, particularly NT-proBNP, are recommended for use in both acute and chronic heart failure due to their role in assessing cardiac dysfunction and guiding treatment decisions. Furthermore, recombinant human B-type natriuretic peptide (rhBNP) has shown therapeutic potential, especially in acute HF, by enhancing natriuresis, vasodilation, and reducing cardiac preload and afterload [5].

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), the largest subgroup within the transforming growth factor (TGF)-

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The role of BMPs in various organs and development timeline of BMP10. This figure was drawn using Figdraw, (https://www.figdraw.com/). (a) BMPs’ functions in different organs. The BMPs primarily present in the heart, brain, kidneys, and bones, as well as the primary regulatory processes in which they are mainly involved. (b) Development timeline of BMP10. Abbreviations: BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; MI, myocardial infarction; AVMs, arteriovenous malformations; DA, ductus arteriosus; HF, heart failure; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; AF, atrial fibrillation; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; DC, diabetic cardiomyopathy; pPH, pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension; SMC, smooth muscle cell; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; BMPR II, BMP receptor type II; ActR IIA, activin receptor type IIA; ALK1, activin receptor-like kinase 1.

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the current understanding of BMP10 in CVD. It explores BMP10’s role in cardiovascular development, its association with different CVDs, underlying pathogenic mechanisms, diagnostic potential as a biomarker, and as a target for various therapies. By systematically reviewing the relevant literature (Fig. 1b), this review aims to offer new insights into the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of CVD (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. BMP10 in CVD: from biomarker discovery to therapeutic strategies. This figure was drawn using Figdraw, (https://www.figdraw.com/). BMP10 is a heart-specific factor that plays a pivotal role in cardiac development, vascular homeostasis, and the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases. This review aims to provide an overview of the signaling pathways and functions of BMP10, elucidate their roles in the molecular mechanisms associated with cardiovascular diseases, and discuss therapeutic strategies for cardiovascular disease for BMP10 and associated potential opportunities and challenges. BMP10, bone morphogenetic protein 10; CVD, Cardiovascular disease; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; Smad, Sma and Mad-related proteins.

BMPs, which mainly act as homodimers, function in a similar manner to other members of the TGF-

BMP10 interacts with a variety of type I receptors, exhibiting different affinities that are crucial for its cellular role. BMP10 is known for its high affinity interaction with ALK1, a receptor primarily expressed in vascular endothelial cells and is a key modulator of pathological angiogenesis [24, 25, 26, 27]. This process is crucial for both normal vascular development and tumorigenesis [28]. Mutations in ALK1 are linked to hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), characterized by recurrent epistaxis, mucocutaneous telangiectases, and visceral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), which can lead to severe complications such as PAH or HF [29]. As an essential ligand for ALK1 in the postembryonic vasculature [30], BMP10 suppress endothelial cell proliferation and stabilizes arteriolar caliber by binding to ALK1 [31], ensuring vascular structure and function, while preventing tumorigenesis [32]. Mazerbourg et al. [33] suggest that BMP10 also interacts with ALK3 and ALK6, with exogenous overexpression of these receptors enhancing BMP10 signaling and activating the bone morphogenetic protein response element (BRE) promoter. However, Yamawaki et al. [34] used surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to demonstrate that BMP10 binds to ALK6 but not ALK3. They also found that osteolytic lesions in mice with breast cancer metastases were reduced following exogenous ALK6 signaling via a soluble chimeric protein (ALK6-Fc), whereas ALK3-Fc administration promoted gastric adenomas in mice [34]. These results suggest a potential tumorigenic role of ALK3, while the BMP10-ALK6 interaction suggests a protective role of BMP10 for skeletal health. In summary, BMP10 interacts with type I receptors, including ALK1, ALK3 and ALK6, with different affinities, thereby modulating its influence on important biological processes such as angiogenesis, skeletal integrity and oncogenesis. However, a study found no significant differences in BMP10 binding to type II receptors, indicating its functional specificity is likely mediated through type I receptors [25].

BMP10 mediates the Smad-dependent canonical signaling pathway by interacting with type I and type II receptors on the cell membrane. This interaction activates the type I receptor, which phosphorylates the carboxyl terminus of Smad1/5/8, initiating their activation. The receptor-activated Smads (R-Smads) then form a complex with the co-Smad, Smad4, and translocate into the nucleus to promote the expression of target genes. This group of genes includes ID1-3, BMPR2 and Notch target genes such as Jagged1, Dll4, Hey1, Hey2 and Hes1 [26, 35, 36]. In this process, Smad6 and Smad7 function as inhibitors of signal transduction. Smad7 can modulate this signaling by inhibiting the activation of R-Smads, thereby attenuating the signaling cascade [37]. Smad6 inhibits BMP signaling by inhibiting BMPR1A and BMPR1B activity or by competing with Smad4 for binding with phosphorylated R-Smads [38, 39]. Both play crucial roles in cardiovascular development through this inhibitory mechanism. However, BMP7 exerts its effects by broadly inhibiting TGF-

BMP10 also modulates non-classical signal pathways. Upon binding to the receptor, BMP10 facilitates the phosphorylation of serine/threonine residues on the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), a connecting protein that transduces BMP receptor signaling to TGF-

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. BMP10-mediated signaling pathway. This figure was drawn using Figdraw, (https://www.figdraw.com/). BMP10 binds to a pair of BMP type I receptors and a pair of BMP type II receptors on the cell membrane to form a complex, which transmits signals through the classical Smad-mediated signaling pathway or the non-classical signaling pathways mediated by XIAP and STAT3, thereby activating downstream target genes and participating in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, and apoptosis. BMP10 is also regulated by Gs

The cardiovascular system is the inaugural functional organ system during embryogenesis, comprising the heart, which facilitates blood circulation, and blood vessels that transport blood to and from the body’s tissues [46]. Heart formation starts with the aggregation of progenitor cells into a cardiac tube. This tube undergoes elongation, looping, segmentation, and maturation, eventually forming a four-chambered heart [47]. Vascular development and growth rely on two key processes involving endothelial cells: vasculogenesis and angiogenesis [48]. Vasculogenesis forms new blood vessels from endothelial progenitors or angioblasts in the mesoderm, while angiogenesis creates new vessels from pre-existing ones [49]. Physiological angiogenesis is essential for fetal development, the reproductive cycle, and tissue repair [50]. Conversely, pathological angiogenesis is linked to diseases like diabetic retinopathy, atherosclerosis, cerebral ischemia, and cardiovascular disease [51]. BMP10, a polypeptide, influences cardiac development through autocrine or paracrine mechanisms. BMP10 is involved in progenitor cell differentiation and is crucial for ventricular wall formation and maturation by promoting the expression of the T-box transcription factor (TBX) 20 [52, 53]. Additionally, BMP10 contributes to vascular homeostasis by influencing angiogenesis and vascular remodeling.

In 1999, the BMP10 gene was first cloned from murine sources, revealing its crucial role in embryonic heart development. BMP10 expression is predominantly localized to the trabecular region of the embryonic heart, which consists of the intricate meshwork structures that arise from the proliferation and invagination of cardiomyocytes into the cardiac lumen [54, 55, 56]. Initially formed as a loose network, these structures undergo morphological transformations during heart maturation, culminating in the fusion and consolidation into a more robust myocardial layer. This process, termed myocardial densification, is crucial for enhancing the heart’s contractile force and pumping efficiency [57]. BMP10 expression in the trabeculae of the ventricular chambers and the globular region is detectable from early embryonic development (E9.0) and increases as the heart matures. By embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5), BMP10 expression expands to the cell in the atrial wall, peaking in the trabecular region of the ventricle by E14.5 [54]. However, as the organism matures, BMP10 expression within the ventricle decreases, with its presence in adulthood being confined predominantly to the right atrium [58] (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. The role of BMP10 in cardiac development. This figure was drawn using Figdraw, (https://www.figdraw.com/). (a) BMP10 expression dynamics in cardiac development. Starting from embryonic day E9.0, BMP10 (yellow dot) is expressed in the trabecular region of the ventricles and cardiac cushions, and by E12.5, its expression extends to the atria. At E14.5, the expression of BMP10 in the ventricular trabeculae reaches its peak; however, as the individual matures, the expression of BMP10 in the ventricles decreases, ultimately being detectable only in the right atrium in adulthood. (b) BMP10 Regulation in heart development. During cardiac development, a multitude of factors, including Myocardin, BRG1, Notch, FKBP12, Numb/Numblike, IRX3, and IRX5, collectively interact to coordinately regulate the expression of BMP10, thereby ensuring the normal formation and function of the heart. Abbreviations: E, embryonic day; SRF, serum response factor; circNCX1, circular RNA derived from the sodium/calcium exchanger 1 gene; FBW7, F-box/WD repeat-containing protein 7; BRG1, brahma homolog 1; FKBP12, FK506-binding protein 12; IRX, iroquois homeobox; TBX5, T-box transcription factor 5.

BMP10 plays a critical role in regulating the development of myocardial trabeculae. BMP10 deletion leads to the upregulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p57kip2, disrupting cardiac cell cycle exit and reducing the expression of cardiogenic transcription factors natural killer (NK)2 homeobox 5 (NKX2.5) and myocyte enhancer factor 2c (MEF2C) [58]. This cascade of events results in reduced cardiomyocyte proliferation. Conversely, BMP10 overexpression leads to excessive myocardial trabeculae formation, which may promote myocardial non-compaction [59]. These observations emphasize the essential role of balanced BMP10 expression for proper cardiac morphogenesis. Additionally, BMP10 promotes the differentiation of cardiovascular progenitor cells derived from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) into endocardial cells [60]. These endocardial cells play a key role in inducing myocardial trabeculae formation. BMP10 secreted by cardiomyocytes helps endocardial cells maintain their phenotype by activating NKX2.5. neuregulin 1 (NRG1) activation in endocardial cells triggers signaling pathways that stimulate myocardium and promote trabeculae formation. This discovery underscores the indispensable role of BMP10 in the complicated process of myocardial trabeculae formation.

During cardiac morphogenesis, BMP10 expression is regulated by various factors through direct or indirect mechanisms, synergistically controlling cardiac development. Myocardin transactivates the BMP10 gene by forming a serum response factor–myocardin complex with a non-consensus CArG element in the BMP10 promoter, promoting cardiomyocyte proliferation and ventricular maturation [61]. In contrast, a circular RNA derived from the sodium/calcium exchanger 1 gene (circNCX1) mediates the negative regulation of Brahma homolog 1 (BRG1) by acting as a bridge between the F-box/WD repeat-containing protein 7 (FBW7) and BRG1, thereby promoting ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of BRG1 [62]. This cascade subsequently decreases BMP10 expression, leading to cell cycle arrest and attenuation of cardiomyocyte proliferation. Additionally, the Notch signaling pathway indirectly influences BMP10 expression, promoting ventricular cardiomyocyte proliferation and trabeculae formation [63]. Negative regulatory factors such as FK506-binding protein 12 (FKBP12) [58] and Numb/Numblike [64] curb the overexpression of BMP10 and thus protect the integrity of myocardial compaction. BMP10 overexpression in the heart can cause compromised cardiac growth and defects in cardiomyocyte postnatal hypertrophic growth [65]. In addition, formation of the embryonic cardiac septum requires direct transcriptional repression of BMP10 by Iroquois homeobox (IRX) 3 and IRX5 in the endocardium [66]. The individual or synergistic action of IRX3 and IRX5 can prevent TBX5 from activating the BMP10 promoter, thereby repressing BMP10 expression (Fig. 4b).

Angiogenesis, the development of new blood vessels from existing capillaries to form a mature vascular network, is a complex and tightly regulated process [67]. This intricate process begins with the breakdown of the basement membrane, followed by the activation, proliferation and migration of endothelial cells, which ultimately leads to the formation of new vascular channels [68]. Physiologically, angiogenesis is primarily activated during crucial developmental stages such as embryogenesis, tissue repair, the menstrual cycle, muscle development and the rejuvenation of the endothelial lining of organs, ensuring the vital supply of blood and nutrients [69]. In contrast, dysregulated angiogenesis contributes to neoplastic diseases and retinopathies [70], while insufficient angiogenesis may result in coronary heart disease [71]. In adult vasculature, endothelial cells are generally in a state of quiescence. However, pathological stimuli can disrupt this balance, triggering reactivation of these cells and initiating a cascade of pathological angiogenesis. In such cases, the modulation of static factors is crucial to curb abnormal vascular growth.

BMP10 has been hypothesized to be a circulatory quiescence factor involved in angiogenesis [31]. BMP10 is biosynthesized as a proprotein and undergoes furin-mediated cleavage during secretion, resulting in the mature, bioactive BMP10 that enters the bloodstream [72]. Circulating BMP10 binds to the endothelial cell ALK1 to induce phosphorylation of Smad1/5/9, which limits endothelial cell counts and stabilizes the caliber of nascent arteries [31]. ALK1 is an important regulator of normal blood vessel development as well as pathological tumor angiogenesis. Mutations in ALK1 cause AVMs [25]. AVMs, direct arterial-to-venous connections bypassing the capillary network, lead to oxygen deprivation and hemorrhage [73]. BMP10 shares significant amino acid sequence homology with BMP9, another BMP family member. The two proteins act as high-affinity ligands for ALK1, binding to it and triggering the Smad signaling cascade, which inhibits endothelial cell proliferation and migration, thereby preventing the development of AVMs [25, 74]. Additionally, they can bind directly to endoglin with high affinity, thereby playing a role in angiogenesis. ALK1-mediated BMP10 and BMP9 signaling inhibits AVM formation in HHT and the retinal vasculature of neonatal mice [36, 75]. A recent study has revealed that BMP10 can form a biologically active heterodimer with BMP9 through disulfide bonding, which acts on endothelial cells via ALK1 and accounts for most of the biological BMP activity present in plasma [76].

In circulation, BMP10 exists in a form where the precursor domain is bound to the mature ligand and remains active on endothelial cells [77]. A study has revealed that the BMP10 deficiency can precipitate the emergence of AVMs in the developing retina of mice, the postnatal brain, and the skin following injury in adults [24]. Furthermore, BMP10 mutants have been shown to elicit AVMs within the skin and liver vasculature of zebrafish, culminating in a systemic decrease in vascular resistance and a state of volume overload [30]. These findings underscore the capacity of BMP10 to operate autonomously from BMP9 in the regulation of the arteriovenous network.

In addition, BMP9 and BMP10 participate in the occlusion of the ductus arteriosus (DA). It is widely accepted that DA closure occurs in two stages: functional closure, followed by anatomic closure [78]. Functional closure, occurring within hours after birth, results from DA constriction, while anatomical closure is primarily driven by vascular remodeling [79]. During anatomic closure, BMP9 and BMP10 induce endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT), promoting the vascular remodeling essential for the shift from fetal to neonatal circulation [80].

BMP10’s role in cardiovascular development is well-established, but its specific functions and mechanisms in CVDs remain unclear. As a key regulatory molecule, BMP10 shows altered expression in various CVDs (Table 1, Ref. [17, 18, 45, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88]). Beyond its developmental role, BMP10 significantly influences the pathophysiology of conditions such as atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction, dilated cardiomyopathy, and diabetic cardiomyopathy, and contributes to CVD treatment (Table 2, Ref. [44, 45, 88, 89, 90]). Unraveling the precise mechanisms by which BMP10 operates in these diseases is essential for identifying novel therapeutic targets, potentially leading to more targeted and effective intervention strategies in cardiovascular medicine (Fig. 5).

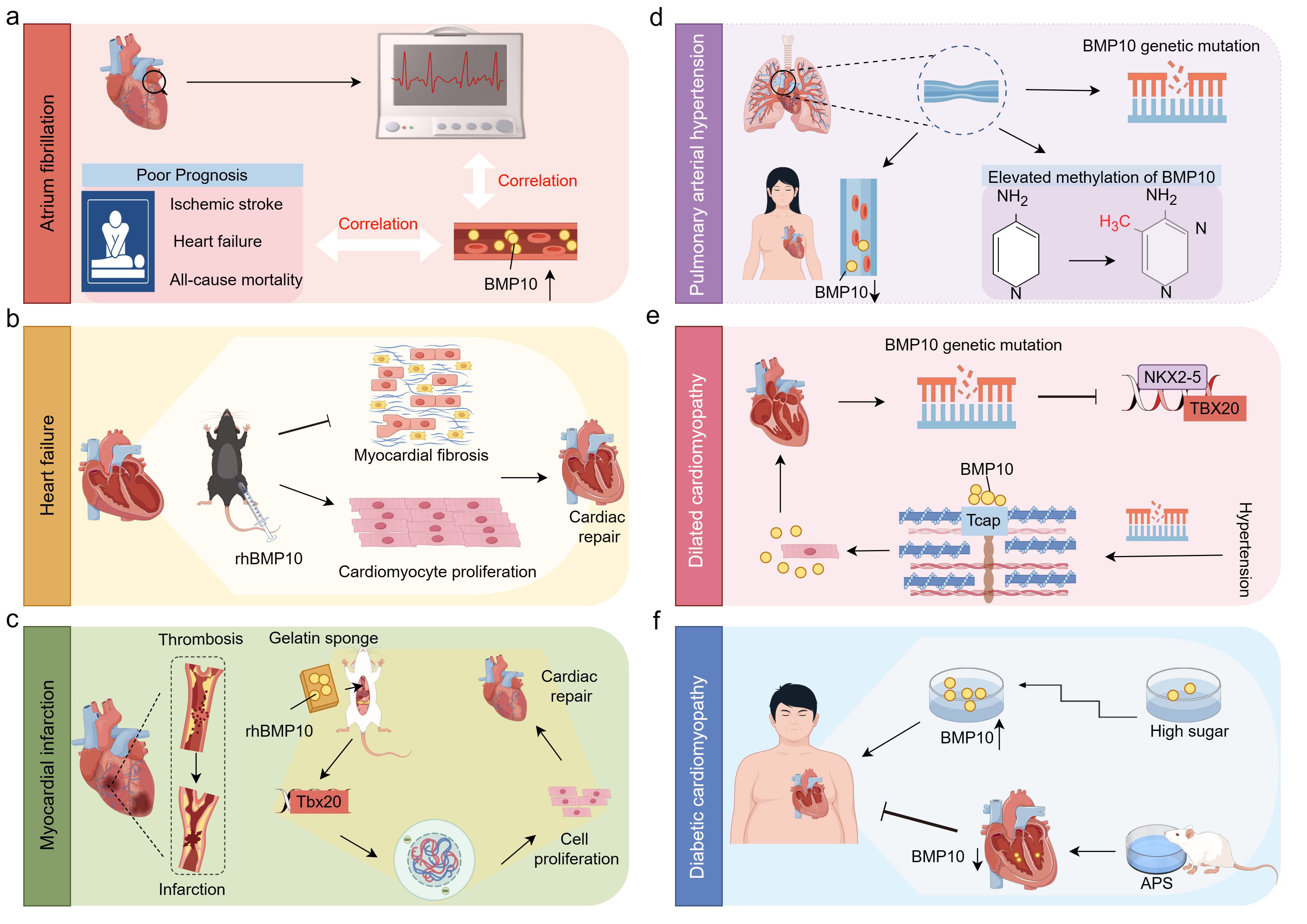

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. The role of BMP10 in CVDs. This figure was drawn using Figdraw, (https://www.figdraw.com/). (a) AF. The plasma levels of BMP10 are positively correlated with atrial fibrillation and its adverse outcomes, including ischemic stroke, heart failure, and all-cause mortality. (b) HF. In a mouse model of heart failure, intraperitoneal administration of rhBMP10 promotes cardiac repair by enhancing cardiomyocyte proliferation and alleviating cardiac fibrosis. (c) MI. MI is characterized by thrombosis and subsequent vascular occlusion. In a MI animal model, the implantation of gelatin sponges enriched with rhBMP10 can induce cardiomyocyte re-entry into the cell cycle, thereby promoting their proliferation and facilitating cardiac repair. (d) PAH. In patients with PAH, an increase in BMP10 gene mutations and promoter hypermethylation has been observed, along with a reduction in BMP10 expression specifically in female PAH patients. (e) DCM. Patients with DCM exhibit BMP10 gene mutations that result in the loss of its ability to activate NKX2-5 and TBX20. Furthermore, in hypertensive DCM patients, BMP10 mutations lead to a reduction in the binding of BMP10 to Tcap, which results in enhanced extracellular secretion of BMP10 and exacerbates the progression of DCM. (f) DC. In DC, high glucose promotes the expression of BMP10 in a concentration-dependent manner, while APS has been shown to alleviate diabetic cardiomyopathy by suppressing BMP10 expression. Abbreviations: BMP10, bone morphogenetic protein 10; CVDs, cardiovascular diseases; rhBMP10, recombinant human BMP10; MI, myocardial infarction; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; NKX2-5, NK2 homeobox 5; TBX20, T-box transcription factor 20; Tcap, titin-cap; APS, astragalus polysaccharide; DC, diabetic cardiomyopathy.

| Disease | Changes in BMP10 | Sample/Species | Test Method | Refs |

| AF | Blood/Human | ECLIA | [81, 82, 83, 84] | |

| Ischemic stroke | Plasma/Human | ECLIA | [18, 85] | |

| HF | Cardiac tissue/Mice | Western blot | [45] | |

| PAH | Plasma/Female | ELISA | [86] | |

| pPH | Blood/Human | ECLIA | [87] | |

| Hypertension | LV cardiac tissue/Rats | qRT-PCR | [17] | |

| DC | Cardiac tissue/Rats | Western blot/qRT-PCR | [88] |

Abbreviations: BMP10, bone morphogenetic protein 10; CVDs, cardiovascular disease; AF, atrium fibrillation; ECLIA, electrochemiluminescence immunoassay; LAA, left atrial appendage; RAA, right atrial appendage; OAC, oral anticoagulants; HF, heart failure; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; pPH, pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension; PVR, pre-capillary component; pBMP10, pro-bone morphogenetic protein 10; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; LV, left ventricular; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; DC, diabetic cardiomyopathy.

| Disease | Model | Primary conclusion | Treatment | Refs |

| HF | ISO-induced HF in Mice | BMP10 preserves cardiac function through its dual activation of Smad-mediated and STAT3-mediated pathways | Intraperitoneal injection of rhBMP10 | [44] |

| HF | DOX-induced HF in mice | BMP10 exerts a protective effect in DOX-induced cardiac injury through its dependence on STAT3 activation | Tail vein injection of AAV9 carrying BMP10 | [45] |

| HF | TAC-induced HF in Mice | Gs | Intraperitoneal injection of rhBMP10 | [90] |

| MI | MI in rat induced by LVD ligation | BMP10 stimulated cardiomyocyte proliferation and repaired cardiac function after heart injury | rhBMP10-gelatin sponge heart implantation | [89] |

| DC | STZ-induced DC rats | APS can alleviate cardiac hypertrophy and protect against DC by inhibiting activation of the BMP10 pathway | Oral APS solution | [88] |

Abbreviations: ISO, isoproterenol; Smad, Sma and Mad-related proteins; STAT3, Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3; rhBMP10, recombinant human BMP10; DOX, doxorubicin; AAV9, adeno-associated virus serotype 9; TAC, transverse aortic constriction; Gs

AF, the most prevalent sustained cardiac arrhythmia, currently affects an estimated 50 million individuals globally in 2020, and this number is expected to rise as the population ages. The incidence of AF is expected to more than double in the next four decades [91]. AF is associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), including heart failure, severe stroke, and myocardial infarction [92, 93]. Circulating BMP10 has been shown in several studies to have an important role in the diagnosis and prognostic assessment of AF. A cross-sectional observational study quantified 12 biomarkers associated with AF in a cohort of 1485 patients with cardiovascular diseases [81]. The findings indicated that BMP10 was instrumental in identifying patients with prevalent AF [81]. Plasma BMP10 levels were also correlated with the risk of postoperative AF. Pre-procedure plasma BMP10 levels in patients undergoing initial catheter ablation for AF were found to be strong predictors of AF recurrence or absence within 12 months post-procedure [82]. After cardiac surgery, elevated BMP10 levels were linked to a history of persistent AF, a higher chance of late AF within 90 days post-surgery, and the presence of subendomyocardial fibrosis in the left atrium [83]. Since subendomyocardial fibrosis is a primary determinant of AF conduction abnormalities, these associations underscore the high sensitivity and specificity of BMP10 in identifying AF [94].

The mortality rate in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) is 3.5 times higher than that in non-AF patients, and this increase is directly associated with the heightened risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in individuals with more severe forms of AF [95, 96]. A prospective Swiss AF cohort study identified BMP10 as a predictor of all-cause mortality and MACE in AF patients, providing prognostic insights for both low- and high-risk groups stratified by NT-proBNP levels [97]. Further investigation in the ACTIVE A and AVERROES trials revealed that BMP10 levels were independently correlated with the risk of ischemic stroke in AF patients, irrespective of their oral anticoagulation therapy status [18]. In the ARISTOTLE trial, plasma samples from AF patients randomized to receive apixaban or warfarin for two months were analyzed for BMP10 levels. Elevated BMP10 levels were significantly associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, heart failure, and all-cause mortality [85]. Consequently, the inclusion of BMP10 levels, measured after two months, along with established risk factors and baseline BMP10 values, could improve the risk assessment for ischemic stroke, heart failure, and all-cause mortality, enhancing risk stratification in AF patients. In addition, the EAST-AFNET 4 biomolecule study has demonstrated a strong correlation between low BMP10 levels and the likelihood of atrial fibrillation patients returning to sinus rhythm [98]. These findings suggest that BMP10 could become a promising biomarker for diagnosing, prognosticating, and assessing treatment efficacy in AF and its associated comorbidities.

While numerous studies emphasize the potential of BMP10 as a biomarker for AF, no research has yet explicitly clarified a mechanism that connects elevated circulating BMP10 levels with an increased susceptibility to AF. However, it is hypothesized that elevated levels of circulating BMP may correlate with reduced levels of PITX2 in AF patients. PITX2, a transcription factor expressed in the left atrial myocardium, is associated with an increased predisposition to AF [99, 100]. BMP10, an atrial-specific secreted protein, is downregulated by PITX2. Therefore, elevated plasma BMP10 levels may serve as a surrogate marker of PITX2 activity, potentially predicting AF recurrence [84]. In Pitx2 mutant mice, BMP10 within cardiomyocytes has been shown to transmit pathogenic signals to endocardial and endothelial cells, facilitating cell adhesion and platelet activation, as well as contributing to inflammatory responses [101]. Thus, BMP10 may emerge as a novel biomarker with significant potential for diagnosing AF and predicting its associated comorbidities.

Myocardial damage, one of the most severe consequences of cardiovascular disease, significantly contributes to elevated cardiovascular mortality [102]. Typically caused by acute events such as a myocardial infarction, this damage triggers inflammation and fibrosis, resulting in structural and functional changes in the heart. These changes compromise the heart’s contractile ability, reducing its capacity to pump blood and eventually leading to heart failure [103, 104]. The pathological process of cardiac remodeling, characterized by the replacement of necrotic cardiomyocytes with fibroblasts, is a key factor in the development of HF following an MI [105]. Consequently, strategies to enhance cardiomyocyte proliferation and activation have emerged as a modern approach for treating MI and HF.

Historically, myocardial injury in mammals was thought to be irreversible due to the limited regenerative capacity of mature cardiomyocytes [106]. However, accumulating evidence suggests that even terminally differentiated mammalian cardiomyocytes possess proliferative capabilities [107]. BMP10, a growth factor critical during embryonic heart development, has been identified as a potent stimulator of cardiomyocyte proliferation in the adult murine heart. Intramyocardial administration of recombinant human BMP10 (rhBMP10) upregulates TBX20 expression, promoting DNA synthesis and cytoplasmic division in rat cardiomyocytes, and inducing them to re-enter the cell cycle and undergo mitosis [89]. The implantation of gelatin sponges enriched with BMP10 in rat hearts has been demonstrated to reduce the size of the infarcted myocardium [89]. Furthermore, this BMP10-based therapy has exhibited favorable outcomes in a mouse model of isoprenaline-induced myocardial injury, with intraperitoneal administration of rhBMP10 reducing apoptosis, enhancing cardiomyocyte survival, and inhibiting cardiac fibrosis through the dual activation of Smad-mediated classical signaling and STAT3-mediated non-classical signaling pathways. These effects ultimately preserve the contractile function of the damaged heart [44]. Exogenous BMP10 overexpression also mitigates adriamycin-induced cardiac injury by activating the STAT3 signaling pathway [45].

BMP10 stimulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and restores impaired cardiac function in Gs

The emergence of metabolic reprogramming as a strategy to promote cardiomyocyte regeneration and reverse myocardial injury has attracted significant attention [108]. Mammalian cardiomyocytes demonstrate extraordinary regenerative capacity during the fetal stage, but this potential rapidly declines within the first week postpartum [109]. This decline in proliferative capacity is correlated with a metabolic shift from anaerobic glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation [110]. In contrast, adult zebrafish have a remarkable cardiac regenerative capacity, far exceeding that of mammals. Metabolic analysis of cardiomyocytes at injury sites in adult zebrafish reveals a reliance on glycolysis for energy production, with the inhibition of glycolysis adversely affecting the division of cardiomyocytes [111]. This metabolic reprogramming is mediated by NRG1/ErbB2 signaling, wherein NRG1 binds to ErbB2 receptor proteins on cardiomyocytes, inducing the metabolic shift [111, 112].

Significant interactions between BMP10 and NRG1 signaling have been observed during embryonic development [60]. BMP10 enhances NRG1 secretion from endocardial cells, and NRG1 binding to ErbB2 on cardiomyocytes promotes myocardial trabeculae formation. Similar BMP10 and NRG1 signaling crosstalk was observed in adult PITX2 mutant mice [101], where cardiomyocytes release BMP10 signaling molecules to activate endocardial cells. In response, these cells release NRG1, which then feedbacks to the cardiomyocytes. Additionally, BMP10 expression was upregulated during lactate-induced cardiomyocyte proliferation [113]. Overexpression of LDHA, which drives lactate production in adult mouse hearts, promotes cardiac regeneration by inducing metabolic reprogramming of cardiomyocytes [114]. Hence, BMP10’s capacity to stimulate cardiac proliferation has the potential to be a therapeutic target for the treatment of cardiac injury.

PAH is a life-threatening condition characterized by a persistent elevation in pulmonary vascular resistance, potentially culminating in right ventricular failure and mortality [115]. Recent studies highlight the important role of BMP10 in the etiology of PAH, emphasizing its potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target. In PAH, truncating mutations and predicted loss-of-function variants in BMP10 have been identified [116, 117, 118], suggesting it as a novel PAH-associated gene. Circulating BMP10 levels were significantly lower in GDF2 mutants, another gene associated with PAH. Analysis of proBMP10 levels in 120 control samples and 260 PAH patients, including hereditary and idiopathic forms, revealed no correlation with patient age [86]. Notably, proBMP10 levels in female PAH patients were substantially lower than in the control group, supporting the potential of BMP10 as a biomarker for PAH. Of the 11 biomarkers evaluated in a large prospective cross-sectional study of 127 patients with pulmonary hypertension, BMP10 was the only one to correlate with elevated PVR without association with pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP) [87]. This correlation highlights the non-invasive diagnostic value of BMP10 for pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension. NT-proBNP, which is recognized by international guidelines as the sole biomarker for pulmonary hypertension [119], correlated positively with both PVR and PAWP. This suggests that BMP10, in combination with NT-proBNP, could serve as a complementary stratification tool for patients with pulmonary hypertension.

BMP10 is implicated in the pathogenesis of PAH through multiple pathways. The increased pulmonary arterial pressures in PAH patients are mainly due to elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), driven by sustained vasoconstriction and abnormal pulmonary vascular remodeling [120]. Pulmonary vascular remodeling encompasses changes in the three layers of the vessel wall (intima, media, and adventitia), and is associated with dysfunction of pulmonary arterial endothelial cells (PAECs), abnormal proliferation of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), and accumulation of fibroblasts [121, 122]. Among these factors, the abnormal proliferation of PASMCs is central to the pathogenesis of abnormal pulmonary vascular remodeling. This proliferation arises from the phenotypic transition of PASMC from a contractile or quiescent state to a proliferative or synthetic state, ultimately leading to the narrowing and occlusion of small pulmonary arteries [123, 124]. BMP10 inhibits the PAH pathogenesis via endothelial-smooth muscle cell interactions. A study has demonstrated that BMP10 induces the expression of transcription factor GATA6 via the ALK1/BMPR2/ENG/ERK1/2 signaling pathway [125]. GATA6, a member of the GATA family of zinc-finger transcription factors, is downregulated in the pulmonary vasculature of PAH patients, and its deficiency is associated with the development of PAH [126]. GATA6 plays a crucial role in pulmonary vascular cell communication, and endothelial GATA6 deficiency results in GATA6 loss in PASMC [125]. Furthermore, research suggests that GATA6 alleviates PAH by reducing oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in the pulmonary vasculature [125]. Another study indicates that BMP9 and BMP10 inhibit the release of CCL2 from PAECs [127]. CCL2 stimulates PASMC migration and proliferation, thus promoting pulmonary vascular remodeling [128]. Notably, BMP10 can also directly affect VSMCs, modulating their phenotype and promoting the transition from a synthetic to a contractile state, which is essential for maintaining vascular tone and function [37]. Moreover, methylation analysis in PAH patients showed higher BMP10 methylation levels compared to controls, indicating a potential epigenetic regulatory role for BMP10 [129].

BMP10 is implicated in the etiology and progression of PAH via a spectrum of mechanisms, encompassing genetic alterations, epigenetic modifications, the modulation of oxidative stress, and the suppression of pulmonary vascular remodeling. These multifaceted roles position BMP10 as a promising candidate for therapeutic interventions in PAH.

DCM is the presence of left ventricular or biventricular dilatation or systolic dysfunction in the absence of an abnormal loading condition (e.g., primary valve disease) or severe coronary artery disease sufficient to cause ventricular remodeling [130]. DCM is one of the most prevalent causes of heart failure and the need for heart transplantation [131]. DCM is predominantly linked to genetic factors, with most cases showing a genetic predisposition [132, 133]. Gu et al. [134] identified a novel BMP10 variant, NM_014482.3:c.166C

Nakano et al. [17] explored the relationship between BMP10 and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. They observed that BMP10 expression was upregulated in hypertension-induced cardiac hypertrophy. BMP10 interacts with titin-cap (Tcap), a Z-disk protein of cardiomyocytes, thereby affecting its intracellular localization and secretion. Notably, the Thr326Ile variant of BMP10, which is associated with hypertensive dilated cardiomyopathy, diminishes BMP10 binding to Tcap. This reduced binding increases BMP10 secretion, amplifying the hypertrophic effect on cardiomyocytes. These findings suggest that genetically compromised BMP10 may predispose individuals to DCM. Therefore, BMP10 has emerged as a novel gene associated with DCM in humans, underscoring its significance in prenatal prevention, prognostic risk assessment, and potentially personalized treatment for DCM.

DC, a pathophysiological condition precipitated by diabetes mellitus (DM), is characterized by HF without significant coronary artery disease, hypertension, or valvular heart disease [139]. Cardiac hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction are key clinical features in individuals with DC [140]. A cardiac transcriptome analysis of 12-week-old male diabetic Akita dogs revealed that BMP10 was one of the most significantly upregulated transcripts among 137 differentially expressed genes [141]. Furthermore, in H9C2 cardiomyocyte cultured under high-glucose conditions, BMP10 expression exhibited a dose-dependent increase with elevated glucose levels [142]. These findings indicate that a high-glucose milieu may enhance BMP10 expression, potentially exacerbating diabetes-induced cardiomyopathy.

Mice deficient in BMP10 are known to succumb during embryonic development, exhibiting reduced trabeculogenesis, ventricular hypoplasia, and a thinning of the ventricular wall [58]. In contrast, myocardial overexpression of BMP10 causes ventricular wall thickening and constriction in the subaortic region in mice four weeks after birth [65]. This evidence supports BMP10’s role in ventricular hypertrophy, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target for DC and offering a novel perspective for its treatment. In a study by Sun et al. [88], astragalus polysaccharide (APS), the principal active component extracted from astragalus, demonstrated the potential to inhibit BMP10 and its downstream signaling pathways. APS, known for its anti-hypertrophic effects, reduces high glucose-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by decreasing BMP10 expression and its downstream proteins, thereby improving cardiac function. Developing BMP10-targeted therapeutics presents new avenues for managing DC.

BMP10 is a pleiotropic cell signaling molecule essential for cardiovascular development, homeostasis, and pathogenesis, and is a key modulator of cardiovascular function. The expression levels of BMP10 are significantly altered in the onset and progression of CVD, with dysregulation closely associated with cardiac dysfunction. Altered BMP10 expression in the pathogenesis of AF offers a potential biomarker for clinical risk stratification and prognostic assessment. Mutations in the BMP10 gene have been established to increase susceptibility to PAH and DCM, further corroborating the potential of BMP10 as a novel therapeutic target for these conditions. Moreover, the therapeutic potential of BMP10 in HF and MI is increasingly evident, with BMP10 modulating the proliferation and apoptosis signaling pathways, providing new treatment strategies for cardiac repair and regeneration. These findings enrich our understanding of BMP10 and offer renewed hope for its clinical application in treating CVD.

Despite significant advancements in BMP10 research for CVD, several challenges must be addressed before BMP10 can become an effective biomarker and therapeutic target for clinical application. In humans, BMP10 levels are influenced by physiological factors such as lower body mass index, advanced age, gender, and renal dysfunction [18], requiring standardized methods to improve the reliability of BMP10 measurements. Although BMP10 has been identified as a biomarker for AF occurrence, complications, and prognosis in many large-scale studies, its clinical translation remains challenging. Furthermore, integrating BMP10 levels with established biomarkers, such as NT-pro-BNP, to enhance diagnostic accuracy is an area that requires further exploration. Data from large prospective and retrospective studies are needed for the detection and assessment of BMP10 levels to be included in clinical guidelines.

Currently, therapeutic strategies targeting BMP10 are in the exploratory phase. Additional research into its regulatory mechanisms and the development of standardized measurement methods are crucial steps for its clinical adoption. Although studies have implanted gelatin sponges containing rhBMP10 in animal hearts to treat MI [105], clinical application requires addressing the compatibility between rhBMP10 and the gelatin sponge, BMP10’s release rate, and the appropriate pharmacological dosage. Prior to this therapeutic application, a comprehensive assessment of the safety and efficacy of rhBMP10 must be conducted, including its toxic side effects, potential risks, and therapeutic benefits. The complexity of the cardiovascular system demands a deeper understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of BMP10 in various CVDs, and validation of its safety and efficacy in clinical trials. Given that BMP10 may exert different biological functions in the heart and other organs [19, 42, 143], developing targeted therapies for specific disease stages, while minimizing adverse effects on other physiological processes, will be crucial for the specific clinical application of BMP10. Additionally, exploring how current guideline recommended therapies, such as sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNI), modulate BMP10 levels and influence its biological effects is an emerging area for further research. The complexity of BMP10 signaling suggests we must consider its multiple roles in disease progression, including its effects on electrical signal conduction, oxidative stress, fibrotic processes, and myocardial metabolism.

In summary, the investigation and application of BMP10 in cardiovascular diseases hold vast promise, yet they are significant challenges that need to be addressed. Future research will focus on several key areas: (1) the comprehensive elucidation of BMP10’s regulatory mechanisms in CVDs, including upstream and downstream signaling interactions; (2) establishing standards for assessing BMP10 expression and its changes during disease progression; (3) exploring BMP10’s specific roles in different cardiovascular diseases to advance precision medicine; (4) conducting multicenter, large-scale clinical studies to validate BMP10’s value as a biomarker and its potential for targeted therapy.

Current evidence underscores the pivotal role of BMP10 as a key regulator in cardiac development, vascular homeostasis, and cardiac repair following injury. Additionally, BMP10 holds significant value in the diagnosis and prediction of adverse outcomes in AF. Its clinical application proves beneficial not only for the treatment of CVDs but also for improving the quality of life of patients. However, research on the functional regulation of BMP10 in CVDs remains incomplete. While BMP10 is acknowledged as a promising biomarker for predicting poor prognosis in AF, the regulatory mechanisms governing BMP10 in this condition are still not fully understood. Similarly, although variants of BMP10 have been identified in patients with DCM, the exact regulatory roles of BMP10 in DCM remain unclear. Furthermore, the therapeutic effects of BMP10 recombinant protein in various CVD models require further rigorous experimentation and the development of more refined treatment strategies, particularly through the use of advanced ligand delivery tools. Moving forward, future research should focus on uncovering the underlying mechanisms of BMP10 in CVDs and advancing treatment methods, with the ultimate goal of translating these findings into clinical practice to improve the prognosis of patients with CVD.

This review first comprehensively elucidates the BMP10 signalling pathways, the role of BMP10 in cardiovascular development, and the mechanisms that may influence the progression of CVD. It particularly emphasizes the potential as CVD diagnostic and therapeutic target, offering significant prospects for the development of effective and specific biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

QYJ,CFL,YYJ,ZMY,GX,YQZ,FY,JX and CWL contributed to the study conception and design. CWL and JX selected the review topic. CWL, CFL and FY provided guidance, supervised the project, critically revised the manuscript and contributed insights. QYJ drafted the article. QYJ and YYJ organised the data and prepared the Figs. ZMY and GX provided the theoretical framework and context. YQZ was responsible for checking the literature citations and formatting the references in the review. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the 2023 key Disciplines On Public Health Construction in Chongqing, National Science Foundation of China (81900381); the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing Municipality (CSTB2023NSCQMSX0348); the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (KJQN202300114); and the Chongqing Health Commission Medical Research Project (2024WSJK108).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.