1 Department of Clinical Medicine, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Capital Medical University, 100069 Beijing, China

2 Department of Physiology and Pathophysiology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Capital Medical University, 100069 Beijing, China

3 Experimental Center for Morphological Research Platform, Capital Medical University, 100069 Beijing, China

4 Department of Clinical Laboratory, Aerospace Center Hospital, 100049 Beijing, China

Abstract

This review explores the structure of polyamines, including putrescine, spermidine, and spermine, and their crucial roles in immune cell functions. Polyamines are active compounds derived from ornithine that regulate signaling pathways by interacting with nucleic acids and proteins. Polyamines are essential for normal growth and development in immune cells, participating in cell signaling and neurotransmitter regulation and playing a critical role in immune responses. Notably, high concentrations of polyamines play a significant role in tumor cells and autoreactive B and T cells in autoimmune diseases. This impact should not be overlooked. Elevated levels of polyamines are associated with enhanced immune cell activity in tumor cells and autoimmune diseases. Furthermore, the connection between polyamines and normal immune cell functions, as well as their roles in autoimmune and antitumor immune cell functions, is significant. The role of polyamines in the normal function of activated T cells is well-established, and they are particularly important in antitumor immunity by modulating immune cell functions in the tumor microenvironment (TME). By synthesizing the latest research advancements, this review provides valuable insights into the roles of polyamines in immune regulation and outlines directions for future research.

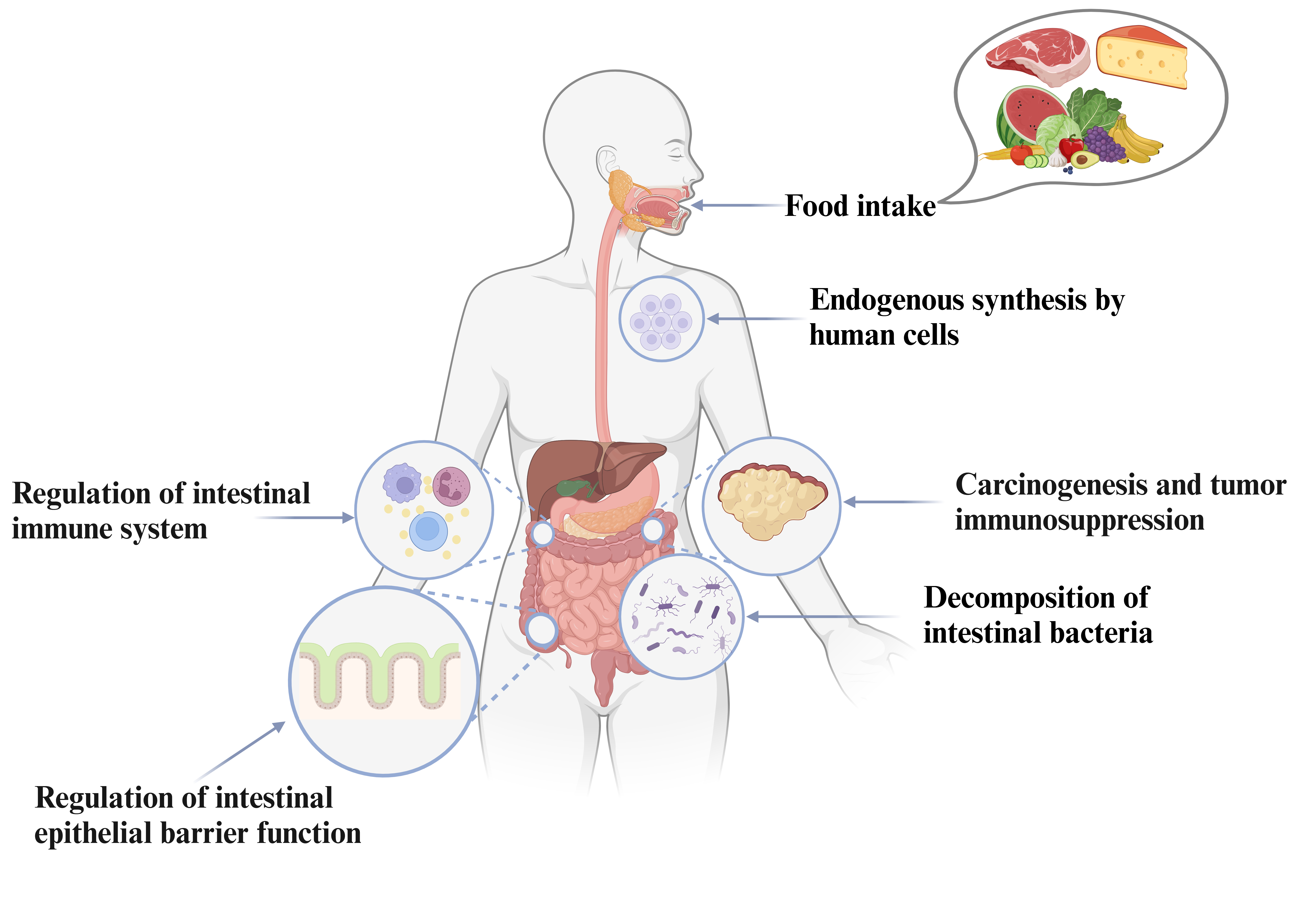

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- polyamines

- biological immunity

- intestinal epithelium

- dysfunction

- gut health

Polyamines, which include putrescine, cadaverine, spermidine, and spermine, are vital biomolecules characterized by their multiple amino groups. At physiological pH, these compounds gain several positive charges because their amino groups are protonated, allowing them to stabilize negatively charged substances like lipid membranes and nucleic acids [1]. As a result, polyamines are widely distributed throughout the human body and play crucial roles in various biological processes [2]. Extensive research has highlighted their cellular and molecular functions, particularly in regulating intestinal barrier function. Polyamines influence the expression and stability of tight junction and adherens junction proteins, like occludin, zonula occludens-1, and E-cadherin, which are essential for maintaining the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier. Additionally, they are involved in regulating intestinal immunity and inflammation. This review aims to provide a comprehensive discussion on the roles and pathways of polyamines within the intestinal epithelium, the intestinal immune system, and cancer, while also briefly addressing the potential clinical applications of polyamines in cancer treatment.

Difference of biological properties between biogenic amines and polyamines.

Polyamines and biogenic amines (BAs) are distinct chemical molecules that play important roles in physiological functions. BAs are nitrogenous compounds that arise from the decarboxylation of free amino acids or the amination of carbonyl-containing organic compounds, as metabolized by various microorganisms [3]. They are involved in numerous physiological processes and are associated with the disorders such as cancer and immunological, neurological, and digestive disorders [4]. In contrast, polyamines are chemical molecules with more than two amino groups that must have for development, survival, and the maintenance of physiological homeostasis. They are particularly abundant in the brain and involved in numerous aspects of human health and diseases. Polyamines contribute to biological activities, such as DNA replication and transcription, RNA translation and frameshift, as well as protein synthesis. According to the composition, BAs are categorized into three categories and the functions summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]).

| Source | Characteristics | Function | Refs | ||

| Monoamines | Dopamine | Brain, kidneys, adrenal glands | Neurotransmitter | Reward-motivated behavior, motor, mood, emotion | [5] |

| Noradrenaline | Locus coeruleus, sympathetic nervous system, adrenal medulla | Neurotransmitter/hormone | Body’s “fight or flight” response, regulating blood pressure, and maintaining alertness and focus | [5] | |

| Adrenaline | Adrenal glands and neurons in the medulla oblongata | Hormone/neurotransmitter | Increases heart rate, dilates airways, and mobilizes energy stores | [5] | |

| Histamine (Imidazoleamines) | Mast cells and basophils, gut Bacteria | Hormone/neurotransmitter | Pro-inflammatory signal | [6] | |

| Serotonin (Indolamines) | Brain’s raphe nuclei and the intestinal enterochromaffin cells | Neurotransmitter | Regulates mood, appetite, sleep, and other physiological processes | [7] | |

| Diamine | Putrescine | Decarboxylation of ornithine and arginine | Strong, foul odor | Cytotoxicity, cell necrosis rather than apoptosis; Regulates the processes of many neurological disorders | [8, 9] |

| Cadaverine | Decarboxylation of lysine | Strong, foul odor | Strong cytotoxicity, cell necrosis rather than apoptosis | [8] | |

| Polyamines | Agmatine | Naturally in the body from the amino acid arginine, certain fermented foods | Neurotransmitter/neuromodulator | Influences receptors associated with pain perception via adrenergic, imidazoline I1, and glutamatergic NMDA receptor, and provides neuroprotection | [10, 11] |

| Spermine | All eukaryotic cells from the amino acid ornithine | A free radical scavenger | Regulates cell proliferation, stress responses, neurological disorders, and provides neuroprotection, anti-aging properties | [9, 12, 13] | |

| Spermidine | Synthesized from putrescine by the enzyme spermidine synthase (SPDS) | Organic compound containing multiple amine groups | Regulates crucial biological processes; a precursor to other polyamines; Increases antioxidative capacity, phenoloxidase activity and pro-longs lifespan; regulates the processes of some neurological disorders and provides neuroprotection | [9, 14, 15] |

BAs, biogenic amines.

Polyamines are organic compounds characterized by the presence of more than two amino groups [16], and they perform critical roles in various biological processes, including cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation. This overview will summarize the categorization and biosynthesis of polyamines.

Polyamines are categorized into two categories: natural and synthetic. Natural polyamines, such as putrescine, spermidine, and spermine are found in high concentrations in the mammalian brain and are biologically and biosynthetically linked to the diamines cadaverine and putrescine. Synthetic polyamines contain molecules such as ethyleneamines, which are commonly employed as chemical intermediates.

Among these, putrescine (a diamine), spermidine (a triamine), and spermine (a tetraamine) are the most common polyamines, with the latter two sometimes called ‘higher’ polyamines [17]. In 1678, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek discovered the occurrence of crystals in human semen. This finding marked an important milestone in scientific history. In 1888, A. Landenburg and J. Abel named these crystals “spermine”, and it wasn’t until 1926 that their correct chemical structure was identified [16]. This discovery was a noteworthy contribution to the research of polyamines, with their chemical structures depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Chemical structure of polyamines. Putrescine can be converted to spermidine by the addition of a propylamine group, which is catalyzed by spermidine synthase. Similarly, spermidine can be converted to spermine by the addition of a propylamine, which is catalyzed by spermine synthase.

Polyamines are synthesized through a complex pathways and enzymes, the main sources of polyamines are cellular synthesis and microbial synthesis in the gut. These compounds can arise from both endogenous and exogenous sources. Exogenous polyamines are derived from the uptake and absorption of active ingredients in food by the intestinal microflora, while endogenous polyamines are generated through de novo synthesis and mutual transformation within cells [18].

Mammalian cells produce three primary polyamines: putrescine, spermidine, and spermine. These polyamines are synthesized by combining the amino acids L-methionine and L-ornithine. L-methionine is converted into S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), which acts as a methyl donor in the polyamine synthesis process. L-ornithine, a precursor for polyamines, is produced from arginine through the action of arginase and is also generated from the urea cycle. In this cycle, glutamine can be transformed into carbamoyl phosphate, which eventually leads to the formation of L-ornithine. Additionally, proline and glutamic acid can be converted into L-ornithine via

Putrescine can be converted into various polyamines by several enzymatic processes. Spermidine is generated by spermidine synthase (SRM), which is then further transformed into spermine by spermine synthase (SMS) [20]. Both SMS and SRM are aminopropyl-transferases which facilitate the formation of spermidine or spermine by attaching propylamine to the amino groups of putrescine [21, 22]. Additionally, S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (AMD) plays a crucial role in producing decarboxylated SAM (dcSAM), which forms the propylamine group necessary for these transformations [23]. AMD, like ODC, is involved in the rate-limiting phases of polyamine synthesis [19]. Furthermore, since methionine is the precursor of SAM, it can limit the production of spermine and spermidine [21]. On the other hand, polyamine catabolism can also revert polyamines back to putrescine. These biochemical transformations are essential for various of biological processes and are vital for the growth and development of organisms.

Spermine oxidase (SMOX) can directly convert spermine to spermidine [20]. Alternatively, the spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase (SSAT) functions as a propylamine acetyltransferase, capable of mono-and di-acetylate spermine. The acetylated polyamines can take two different pathways. One example is a substrate transported by the putative diamine exporter (DAX), which aids its elimination through urine. Furthermore, flavin-dependent polyamine oxidase (PAO) converts acetylated spermine and spermidine into putrescine [20, 23]. Fig. 2 depicts the chemical reaction process.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. An overview of polyamine metabolism in mammalian cells. ODC1, Ornithine decarboxylase 1; OAT, ornithine acetyltransferase; OAZ1-3, ornithine decarboxylase antizyme; AZIN, antizyme inhibitor; SRM, spermidine synthase; SMS, spermine synthase; AMD, S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; dcSAM, decarboxylated SAM; SMOX, spermine oxidase; SSAT, spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase; PAO, polyamine oxidase. Created using BioRender.com.

L-lysine is unique among polyamines as it is a precursor to cadaverine. However, the gene responsible for lysine decarboxylase (CadA), which catalyzes this enzyme in mammals, has not yet to be identified. Several investigations demonstrate that cadaverine is produced from L-lysine via ODC1, despite further evidence is needed to corroborate this theory [12, 20]. Agmatine, on the other hand, is synthesized by arginine decarboxylase, which has been cloned and determined to share 48% similarity with ornithine decarboxylase [10]. Additionally, the high polyamine content in exfoliated intestinal cells suggests that these cells could be a significant source of luminal polyamines [18].

Studies show that polyamine levels decline in multiple tissues and in circulation, which is correlated to the pathophysiology of aging-related disorders like cancer [12, 24]. Furthermore, both lab studies (in vitro) and animal studies (in vivo) have demonstrated that polyamine supplementation can be beneficial for aging-related conditions since polyamine influence DNA methylation patterns. Therefore, regulating polyamine metabolism is essential for maintaining appropriate levels and preventing diseases development.

Polyamines accumulate in the gut via secretions from the stomach and pancreas, as well as from the breakdown products of enterocytes and gut bacteria. Also, exogenous polyamines primarily come from dietary sources, particularly meat, cheese, fruit, certain vegetables, and milk [18]. Table 2 (Ref. [16, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]) depicts the polyamine-rich food and their respective polyamine concentrations based on food detection studies [16, 25], further research is necessary to fully comprehend their bioavailability and absorption. Polyamines have been demonstrated to improve osteogenic differentiation and may offer health benefits.

| Polyamines | Bioavailability | Food categories | Contents (mg/kg) | Refs |

| Putrescine | A cation substitute, osmolyte, and transport protein; Regulation of intestinal immune function and gene expression; Stimulation of protein synthesis | Fermented vegetables | 264.0 | [25, 26, 27, 28, 29] |

| Fish sauce | 98.1–99.3 | |||

| Fermented sausages | 84.2–84.6 | |||

| Cheese | 25.4–65.0 | |||

| Fermented fish | 13.4–17.0 | |||

| Cadaverine | As a building block for polyamides; Involved in cell survival; | Fish sauce | 180.0–182.0 | [25, 30, 31] |

| As a tumor suppressor | Cheese | 25.4–65.0 | ||

| Fermented sausages | 37.4–38.0 | |||

| Fermented fish meat | 14.0–17.3 | |||

| Fermented vegetables | 26.0–35.4 | |||

| Spermine | Free radical scavenging and stabilization of nucleic acids | Wheat germ | 146.1 | [16, 32] |

| Soybeans | 69.0 | |||

| Spermidine | Extend lifespan and improve healthspan; Cardiovascular protection, Neuroprotection | Wheat germ | 354.0 | [16, 33, 34] |

| Soybeans | 207.0 |

Polyamines may exhibit significant toxicity, causing harmful effects on proteins, DNA, and various cellular components. Here are the key highlights from the research regarding polyamine toxicity.

While cadaverine and putrescine are less potent than histamine and tyramine, evidence indicates that high levels of these compounds in foods can lead to serious cardiovascular issues, including hypotension, increased cardiac output, and bradycardia [8, 25]. Additionally, cadaverine and putrescine can increase toxicity indirectly by intensifying the effects of other biogenic amines like histamine [8, 35]. This occurs through competitive inhibition, where consuming putrescine or cadaverine may interfere with detoxifying enzymes like diamine oxidase and histamine N-methyltransferase, which are crucial for breaking down histamine [8], hence preventing histamine metabolism [25], and lowers the excretion of metabolites in urine [36]. Another research revealed that cadaverine can amplify histamine effects, particularly when combined with substances broken down by histaminase [37]. Research shows that diamine oxidase (DAO) works most effectively on histamine compared to other amino acids [38]. Additionally, polyamines like putrescine and spermidine produced by gut microbes, strengthen intestinal barrier by promoting the expression of the cell-cell adhesion protein E-cadherin in a calcium-dependent manner [25]. A reduction in cellular polyamines leads to lower E-cadherin expression and higher cells permeability, but this effect can be reversed with spermidine supplementation [39].

Putrescine and cadaverine are cytotoxic at levels typically found in foods because they react with nitrite to produce nitrosamines, which are known to be carcinogenic, mutagenic, and teratogenic [8, 40, 41]. Thus, it is crucial to consider how foods high in putrescine and cadaverine are processed, such as frying or toasting. While raw foods may not contain nitrosamines, heating stimulates the formation of nitrosamines from putrescine and cadaverine [42]. Elevated levels of putrescine have been associated with the promotion of CT-26 colon tumor cells growth, as demonstrated by real-time cell analysis (RTCA) [43]. This suggests that a high intake of dietary putrescine is associated with an increased risk of developing colorectal adenocarcinoma [8]. This may be because putrescine and cadaverine create low molecular weight “organic cations” at physiological pH, allowing them to interact with anionic phospholipids and damage cell membranes [8, 44]. The cytotoxicity of these diamines may justify the establishment of legal limits for their presence in food products.

Furthermore, putrescine and cadaverine are harmful compounds that disrupt neurotransmission by acting as false neurotransmitters. The gut-brain axis underscores the bidirectional communication between gut microbes and the brain, which can influence cognitive functions and behavior. However, further research is needed to clarify the underlying mechanisms involved [45]. Hepatic encephalopathy is a complicated brain disorder resulting from liver failure, characterized by cognitive deficits, altered consciousness, and various neurological symptoms [46]. Research indicates that this condition may involve the disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the accumulation of toxic substances in the brain suffering from hepatic encephalopathy [47, 48]. Additionally, putrescine may raise the permeability of the blood-brain barrier, potentially leading to cerebral oedema. It is also noteworthy that putrescine can be converted to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by oxidative deamination. Furthermore, polyamines like putrescine may accentuate glutamate activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, leading to elevated Ca2+ and neurotoxicity [48]. Conversely, another investigation revealed that putrescine is crucial for liver regeneration, as it reversing the inhibition of liver regeneration by

It is crucial to highlight that the concentrations of putrescine and cadaverine in most foods are normally below permissible limits and do not pose substantial health hazards. However, excessive or prolonged exposure to certain diamines could result in harmful health effects. Therefore, further research is necessary to better understand the potential health implications of consuming putrescine and cadaverine.

Spermine and spermidine are polyamines found in various tissues, playing crucial in cell metabolism. Most research on their toxicity has primarily focused on experimental animal models, specifically examining renal tubular necrosis caused by reactive and unstable amino aldehydes within the organism [51]. Spermidine has been found to be approximately one-twentieth times less toxic as spermine. The evidence indicated that spermidine has minimal nephrotoxicity, as indicated by a slight increase in kidney mass without any observable kidney damage or histological changes from the treatment [52].

Both spermine and spermidine, alongside putrescine and cadaverine, can form nitrosamines that may contribute to carcinogenesis [53]. Additionally, they exhibit the cytotoxic properties like other polyamines, as seen in dose-dependent cytotoxicity tests conducted in vitro. Notably, spermidine has been found to be more harmful than spermine. The effects may stem from toxic byproducts produced during the oxidative metabolism of these polyamines. However, it is crucial to understand that the toxic levels of spermidine and spermine are higher than the maximum concentrations usually found in the human body. This research suggests that while consuming foods rich in polyamines is not a risk for healthy individuals, low levels of these compounds may still be linked to concerns over cancer and chronic kidney failure [53].

Low intake of spermine and spermidine in infants and suckling mice may increase sensitivity to dietary allergens [54, 55]. Conversely, consuming too much of these polyamines may cause food allergies by affecting the gut barrier [56]. Excessive spermidine increases harmful O2– radicals production in Escherichia coli, particularly in the

Spermine and spermidine are crucial for many biological processes. However, excessive amounts of them can be cytotoxic and lead to various diseases. Therefore, enhancing the intake of spermidine-rich foods like wheat germ, soybeans, and mushrooms could be a practical way to keep these polyamines at healthy levels. Nevertheless, further research is essential to thoroughly elucidate the health effects of consuming spermine and spermidine.

Polyamines have been found to alter gut immune responses. We looked at previous studies to describe the role of polyamines in intestinal immunity and to share our viewpoints.

Polyamines are commonly found in the gastrointestinal (GI) system and may have a substantial impact on intestinal immunity. The GI mucosa layer is lined with epithelial cells that serve as a protective barrier, preventing harmful substances from entering the intestinal lumen [58]. Research also indicates that polyamines within cells are essential in maintaining intestinal epithelial integrity [59].

The integrity of the intestinal mucosal epithelium in mammals relies on a careful balance of cell proliferation, growth arrest, and apoptosis [58]. Research indicates that cells involved in growth and division rapidly increase their levels of cellular polyamines, including humidine, spermidine, and spermine. Additionally, consuming polyamines may inhibit the activity of ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), which can limit the proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) and compromise epithelial integrity [22, 60, 61, 62]. The findings suggest that a deficiency in polyamines might result in hypoplasia of the intestine and colon mucosa, highlighting that polyamines are crucial intracavitary growth factors necessary for the formation and development of the gut mucosa.

Polyamines preserve intestinal epithelium integrity by regulating gene expression. Treatment with difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) significantly lowered polyamine levels and reduced cell proliferation [62]. It also inhibited c-jun and c-myc expression after 4 days and blocked c-fos expression when dbs was given post-serum deprivation. In DFMO-treated cells, spermidine enhanced the transcription of c-jun and c-myc [63]. These findings suggest polyamines enhance growth-promoting gene transcription [22]. Additionally, polyamine-induced c-myc can suppress p21Cip1 transcription, facilitating G1-to-S-phase transition and promoting normal mucosal growth [64].

Multiple studies have revealed that polyamines stimulate intestinal epithelial development by enhancing growth-promoting genes and suppressing growth-inhibiting genes post-transcriptionally [22, 63, 65]. Elevated levels of polyamines negatively affect p53 and nuclear phosphoprotein (NPM), leading to increased IEC proliferation. In contrast, polyamines consumption raises human antigen R (HuR) levels, stabilizing p53 and NPM mRNAs, resulting in higher protein levels and reduced IEC proliferation [65]. Furthermore, the deletion of polyamine lowers mousedouble minute 2 (Mdm2) expression in IEC-6 cells, slowing p53 degradation and enhancing p53 stability, which may increase p21cip transcription, preventing G1-to-S-phase transition and reducing mucosal expansion [66, 67]. Finally, N-myc down-regulated gene 1 (NDRG1) mediates p53 induction following polyamine depletion and is crucial for negatively regulating IEC proliferation, but not apoptosis [68].

Polyamines inhibit the production of JunD, which is crucial for activating protein 1 (AP-1). Deleting polyamines can boost JunD/AP-1 activity. This enhancement boosts p21 gene expression and reduce cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) transcription, thereby limiting cell cycle progression [69, 70]. Additionally, polyamine depletion in IECs can activate the TGF-

Additionally, polyamines stimulate CDK4 translation in the intestinal epithelium via CUG-binding protein 1 (CUGBP1) and miRNA-222 (miR-222) [73], while also negatively regulating their expression in normal IECs. Polyamine depletion induced by DFMO raises the levels of CUGBP1 and miR-222, enhancing their translation and transcription [74]. Following depletion, CUGBP1 correlates with CDK4 mRNA, inhibiting its translation. Meanwhile, miR-222 suppresses CDK4 mRNA by binding to its 3′ UTR [74]. Together, miR-222 and CUGBP1 regulate CDK4 translation and IEC proliferation, as summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Pattern of polyamine signaling pathways affect proliferation of intestinal mucosal. (A) Polyamines inhibit the TGF-

Mucosal bleeding from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), as well as mucosal injury or erosion due to Helicobacter pylori infection, can cause intestinal mucosal damage [75]. At least two strategies can be used to restore the integrity of injured epithelial surfaces. The first strategy is a short-term treatment aimed at repairing the superficial mucosa. This process involves the migration of adjacent epithelial cells to the site of injury, which is facilitated by the rearrangement of the cytoskeleton, formation of membrane protrusions, focal adhesion of the advancing cell front to the extracellular matrix, and the detachment of adhesion sites at the trailing edge of the migrating cells. The second strategy involves replacing injured cells through cell division, a process that is significantly slower and usually begins about 12 hours after the injury [61, 75]. It is worth noting that polyamines play a crucial role in these processes.

Polyamines are essential for intestinal mucosa repair after stress [76], with dietary putrescine improving both villi and mucosal thickness [77]. Additionally, the synthesis of putrescine during healing is linked to the synthesis of epithelial DNA, RNA, and protein [78]. DFMO and spermine injections may accelerate mucosal healing in fasting rats, though the exact mechanism remains unclear [79]. Evidence indicates that the migration of IECs stimulated by polyamines during recovery is primarily mediated by cytoplasmic free Ca2+, which is crucial for regulating recovery after injury. Additionally, polyamines may influence Kv gene expression [80, 81, 82, 83]. Moreover, the Ras homolog gene family member A (RhoA), cell division control protein 42 (Cdc42), and Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) are vital for polyamine-dependent IEC migration post-damage. Increased [Ca2+]cyt level enhance this process via Cdc42 [81]. Polyamines improve Ca2+ influx, leading to increased myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation and promoting myosin fiber production for recovery [84]. Previous research has also indicated that Rac1/PLC

Research has demonstrated that altering STIM1 to STIM2 ratio influences intestinal recovery through TRPC1-mediated Ca2+ signaling, with translocation of STIM1 aiding IEC migration post-injury [85]. Additionally, ODC overexpression raises polyamines, and lowers STIM2 levels. STIM2 inhibits STIM1’s plasma membrane translocation, reducing its TRPC1 binding [88]. These findings imply that polyamines enhance the production and interaction of

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Multipath diagram of polyamine pathways aiding intestinal mucosal repair by stimulating regeneration through Ca2+ involvement. (A) Polyamines may enhance Kv gene expression directly or indirectly, causing membrane hyperpolarization and increased [Ca2+]cyt. (B) Polyamines affect intestinal recovery through TRPC1 Ca2+ signaling by altering STIM1/STIM2 ratios. (C) Polyamines activate Rac1/PLC

The integrity of the intestinal barrier depends on specific protein complexes that facilitate various types of intercellular connections, which include tight junctions, adherens junctions, and desmosomes (refer to Fig. 5) [58, 90]. Tight junctions (TJs) are formed by the collaboration of multiple transmembrane and cytoplasmic proteins, such as claudin, occludin, tricellulin, cingulin, zonula occludens (ZOs), and the junction adhesion molecule (JAM). These proteins cooperate to form intricate structures associated with the cytoskeleton [91]. Adherens junctions (AJs) arise from the interactions of E‑cadherin,

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Electron micrographs (A) and patterns (B) of intestinal epithelial cell junctions. ZOs, Zonula occludens; JAM, junction adhesion molecule. Scale bar: 1.0 µm. Created using BioRender.com.

Numerous investigations have implied that polyamines play a critical role in the expression of E-cadherin within IECs. The application of DFMO, which reduces polyamine levels, significantly diminished both the mRNA expression and protein levels of E-cadherin. In DFMO-treated cells, a notable decrease in the protein levels of

Similarly, depleting polyamines results in a reduction of occludin protein levels without effect on mRNA expression. Alterations in intracellular [Ca2+]cyt did not affect occludin levels [94]. The reduction of polyamines decreases levels checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2), which lowers HuR phosphorylation and its binding affinity to occludin mRNA, ultimately restricting occludin translation [73, 95], hence modulating occludin translation and modulating epithelial barrier function [74, 96]. Furthermore, polyamines are expected to facilitate the interaction between SPRY4-IT1 and TJ mRNAs by modulating HuR phosphorylation and binding strength, which in turn improves the stability and expression of claudin-1, claudin-3, JAM-1, and occluding mRNAs [73, 97]. Also, polyamines may strengthen the interaction between HuR and lncRNA H19, affecting miR-675 processing and intestinal barrier function by promoting E-cadherin and ZO-1 expression [73, 98]. When polyamines are depleted, JunD levels can rise, which inhibits the production of ZO-1 [99]. They also influence other tight junctions like claudin-2, claudin-3, and ZO-2, though mechanisms are still covered [73]. Fig. 6 provides a summary of the regulatory effects of polyamines on tight and adherens junctions via HuR phosphorylation.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Polyamines regulate TJs and AJs by controlling HuR phosphorylation through Chk2. (a) Increased HuR association with lncRNA H19 prevents miR-675 processing, raising ZO-1 and E-cadherin expression. (b) HuR enhances SPRY4-IT1’s association with TJ mRNA, boosting claudin1, claudin-3, JAM-1, and occludin expression. (c) HuR binding to occludin mRNA enhances its translation, while HuR and CUGBP1 compete for binding. Polyamines inhibit CUGBP1. Chk2, Checkpoint kinase 2; CUGBP1, CUG-binding protein 1; HuR, human antigen R; ZO, Zonula occluden; miR-675, miRNA-675; JAM, junction adhesion molecule. Created using BioRender.com.

The intestinal barrier system consists of three layers that maintain a balanced environment in the gut and safeguard it against harmful external factors. The initial barrier consists of the mucus layer, an intricate structure of mucins and antibacterial proteins that covers the gastrointestinal epithelium and effectively prevents germs from reaching the epithelial cells. The second barrier consists of intestinal epithelial cells, which form a physical barrier against harmful bacteria and their components. Additionally, the third barrier is formed by immune cells spread throughout the intestinal epithelium and lamina propria, which are crucial for maintaining intestinal immune responses [100, 101].

Substantial evidence indicates that polyamines are pivotal in the differentiation and maturation of the gut immune system [27, 102, 103]. Polyamines may regulate the development of intestinal immune cells, resulting in more mature intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) and laminae propria lymphocytes (LPLs) [75, 77]. Additionally, polyamines exhibit anti-inflammatory properties by inhibiting pro-inflammatory factors and modulating signal pathways involved in cellular inflammatory [73, 76]. With advancements in evaluation methodologies and analytical techniques advance, researchers are increasingly focusing on the regulatory role of polyamines in the immune system. The following sections will detail the polyamines’ effects on immunity, particularly in gut and tumor immune system.

Polyamines in T cells are extensively studied for their regulatory roles and functions in determining T cell fate. Recently, their regulation has gained more attention.

4.2.1.1 The Impact of Polyamines on T Cell Homeostasis and Their Role in Gut

T cells are known to play a critical role in neonatal biosynthesis and the mechanisms that maintain polyamine homeostasis [104]. The polyamine pool is meticulously regulated through both biosynthesis and salvage pathways, which are essential for T cell proliferation and functions. In vitro study has indicated that arginine is the main carbon donor for polyamine production in T cells, while glutamine functions as a secondary carbon contributor. Consequently, enhancing the polyamine pool may alleviate the dependency of T cells on these pathways [104], which indicate that T cells can rapidly replenish polyamines through enhanced extracellular uptake when biosynthesis is blocked, with salvage and de novo pathways compensating for each other, highlighting their role in metabolic plasticity for polyamine homeostasis, crucial for robust immune responses. Blocking polyamine synthesis and salvage depletes the pool, inhibiting T cell proliferation and inflammation, suggesting targeted polyamine metabolism may be beneficial for treating inflammatory and autoimmune diseases [104].

4.2.1.2 Polyamines Modulating CD8+ T Cells Activity

CD8+ T cells, crucial for tumor regression and immune response, participate in immune-checkpoint inhibitor therapy and adoptive cell treatment [105]. Polyamines serve as a critical metabolic checkpoint in the development of CD8+ tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells [106]. Activation of the antigen-specific T cell receptor (TCR) in CD8+ T cells increases in both the expression and enzymes activity of polyamine biosynthesis, such as ODC, SRM, and SMS, most polyamines are synthesized from glutamine [106, 107]. It was demonstrated that DFMO treatment alters the metabolic pathways of CD8+ T cells shifting their reliance toward oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), a characteristic phenotype of CD8+ TRM cells. This metabolic adaptation is essential for the tissue residency and anti-tumor reactivity [106]. Additionally, polyamines and their oxidation derivatives have been reported to reduce IL-2 production [108, 109], which in turn reduce CD8+ effector cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity as well as attenuates the destruction of tumor-associated blood vessels [110].

CD69 functions as a critical cell surface marker essential for the differentiation of memory T helper (Th) cells and plays a key role in directing their migration to the bone marrow (BM) [111]. The polyamine-hypusine axis has been shown to suppress CD69 expression as well as interferon gamma (IFN-

Furthermore, spermine from necrotic tumor cells reduces cholesterol in CD8+ T cells, hindering activation and aiding tumor growth [112]. On the other hand, spermidine affects cholesterol transcription and may improve CD8+ T cell activity and anti-tumor immunity through fatty acid oxidation [113].

4.2.1.3 Polyamines Guiding T Cell Differentiation

The investigation revealed that spermidine alters the polarization of T helper cell 17 (Th17) to Forkhead- 639 BoxP3+ (Foxp3+) Tregs in vitro and enhances Foxp3+ T cell development via autophagy, reducing mammalian target of Rapamycin (mTOR) signaling on the first day of differentiation. This suggests a pre-autophagy activation signal [114]. The balance between Th17/regulatory T cells (Treg) is linked to gut microbiota and metabolites [115]. Spermidine reduces IL-17A levels but increases Foxp3+ cells, whereas putrescine does not have any effect. Spermidine adjusts the Th17/Treg balance through phenotypic transfer, which in turn reduces intestinal inflammation [114]. Polyamines are known to influence T cell differentiation and are linked to key signaling molecules like mTOR or Myc that control polyamine homeostasis [116], which indicates that polyamines likely influence the metabolic reprogramming and differentiation of immune cells.

Polyamine metabolism plays a crucial role in directing the polarization of CD4+ helper T cells towards different functional targets. Polyamine metabolism is a central determinant of helper T cell lineage fidelity. The regulation of polyamines is important because spermidine is a precursor in the synthesis of the amino acid hypusine [117]. Th cell specialization is regulated by T cell subset-specific transcription factors that coordinate genetic programs for surface molecules and cytokines, influencing cell interactions. Deleting CD4 in ODCs of mice disrupts polyamine synthesis, resulting in abnormal Th-lineage transcription factors and cytokines expression in vivo [118]. Deficiency in ornithine decarboxylase, a crucial enzyme for polyamine synthesis, results in a severe failure of CD4+ T cells to adopt correct subset specification, as evidenced by ectopic expression of multiple cytokines and lineage-defining transcription factors across T helper cell subsets. Polyamines control T helper cell differentiation by providing substrates for deoxyhypusine synthase, which synthesizes the amino acid hypusine. Mice deficient in hypusine develop severe intestinal inflammatory disease, highlighting the importance of polyamine metabolism in maintaining the epigenome to focus T helper cell subset fidelity [117]. Lower levels of spermidine may lead to a reduction in eukaryotic initiation factor 5A (eIF5A), which is synthesized in a two-step process that modifies lysine residues. The initial reaction, mediated by deoxyhypusine synthase (DHPS), facilitates the conversion of spermidine into eIF5a-deoxyhypusine. This is subsequently followed by the action of deoxyhypusine hydroxylase (DOHH), which generates mature hypusine eIF5A. Insufficient activity of ODC, DHS, or DOHH can result in dysregulation of T cells and the development of colitis [117, 118]. The polyamine/hypusine axis guides TH lineage commitment by maintaining chromatin structure of T cell. Depletion of this axis causes epigenetic changes linked to tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle abnormalities. However, eIF5A’s role in sustaining the TCA cycle in T cells remains unclear [117, 118, 119].

CX3CR1highLy6C− macrophages (M

Spermidine has been shown to prevent and reverse colon inflammation linked to M

Experimental findings demonstrated that spermidine treatment effectively reduced M1M

Several studies shed insights into the potential mechanism through which spermidine causes M

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. A model shows spermidine signaling M

Polyamines indeed promote the polarization M

Polyamines are crucial positively charged molecules that play key roles in cell growth, nucleic acid regulation, protein synthesis, and processes like proliferation and apoptosis. They stabilize DNA and RNA, modulate gene expression, and respond to cellular stress, making them essential for both health and disease. Their metabolism of polyamines is tightly regulated, however, when this regulation is disrupted, it is associated with diseases such as cancer, where increased polyamine levels promote rapid cell division and contribute to the TME. This suggests that targeting polyamine metabolism may enhance cancer therapy. Additionally, polyamines are crucial for autophagy and stress resistance, helping cells maintain homeostasis. In the nervous system, they modulate neurotransmitter release and neuronal excitability and play a role in immune regulation. Polyamines are vital for cellular health and significantly influence disease progression, offering potential opportunities for clinical applications. Among them, the specific effect of polyamines on tumor immune microenvironment need attention to provide new targets for tumor treatment.

The above discussion on polyamines in immune cells establishes a foundation for understanding their role in tumor immunosuppression. A recent study shows polyamines link to tumor immunosuppression, causing “cold” tumors unresponsive to immune checkpoint blockade [133]. Previous research suggests that putrescine limits the secretion of TNF-

Putrescine and spermidine inhibit M1M

While the effect of polyamines in promoting macrophage differentiation is an asset, the role in dendritic cells (DCs) is equally compelling. High levels of polyamines in cancer cells suppress the immune function on DCs [139]. Specifically, spermidine produced by DCs activates Src kinase, which in turn phosphorylates indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1), resulting in IDO1-dependent immunosuppression in DCs [141]. IDO1 is vital for cancer immunosuppression as it initiates initiating the kynurenine pathway, and its overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in various cancer [142]. Furthermore, another study identified a positive feedback loop linking IDO1 and polyamine metabolism [143]. Spermidine enhances the IDO1 synthesis, leading to the production of kynurenine that activates the aromatics receptor (AhR), which subsequently activates ODC1, SPDS, and SMOX. This process enhances spermine synthesis and establish a positive feedback loop of immunosuppression [143]. Furthermore, adding humidity in the DC setting reduced their capacity to recognize foreign antigens, making them less immunogenic [144], which might imply that putrescine may potentially create an immunosuppressive environment by influencing DCs [145], highlighting the need to understand how putrescine affects BMDCs differentiation and contributes to tumor immunosuppression by reducing lymphocyte proliferation, neutrophil migration, and NK cell activity [139].

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are immune cells that reside in the TME. Primarily these cells mainly consist of CD8+ T cells, CD4+ Th cells, and Tregs, which are recruited to combat tumors [139, 146].

Polyamines influence the development and function of CD8+ T cell, which plays a role in tumor immunosuppression by inhibiting chemokines like C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL-1), macrophage inflammatory protein-3 alpha (MIP-3

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Highlights of the role of polyamines in innate and adaptive immune responses. (A) Polyamines are critical for T cell differentiation and as a major determinant of helper T cell lineage balance. (B) Polyamines regulate CD8+ T cell development and function, contributing to tumor immunosuppression. (C) Polyamines promote Treg differentiation and regulate Th17/Treg balance, preventing intestinal inflammation. (D) Polyamines impart immunosuppressive characteristics to DCs. eIF5A, Eukaryotic initiation factor 5A; DHPS, deoxyhypusine synthase; DOHH, deoxyhypusine hydroxylase; DCs, dendritic cells; IDO1, indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase 1; Foxp3+, Forkhead- 639 BoxP3+. Created using BioRender.com.

Due to their significant increase in tumor cells and their role in aiding cancer cells evade the immune response, polyamines represent a potential target for anti-tumor therapy. Elevated polyamine levels in cancer are linked to oncogenes like MYC, JUN, FOS, KRAS, and BRAF, with ODC and AMD1 as MYC’s targets [133]. Polyamines are known to impact the stability and translation of MEK-1 mRNA, which is involved in signaling pathways that regulate both cell survival and proliferation [150]. Additionally, polyamine metabolism is a viable therapeutic target due to its role in oncogenes and tumor immunosuppression, focusing on enzyme inhibitors and polyamine analogs [151]. Researchers have found that polyamine biosynthesis inhibitors and analogs hold great potential in cancer studies, particularly in how they affect tumor growth, cause apoptosis, and contribute to cancer progression.

4.2.5.1 Inhibitors of Polyamine Biosynthetic Enzymes

Methylglyoxal bis(guanylhydrazone) (MGBG)

Methylglyoxal bis(guanylhydrazone) (MGBG) was first proposed as an anticancer medication in the 1960s due to its clinical effectiveness against leukemia and lymphoma [152]. MGBG is a competitive inhibitor of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. It reduces the level of spermine and spermidine [153, 154], indicating its potential as a therapeutic target. However, its use in cancer therapy is restricted due to significant mitochondrial damage, gastrointestinal toxicity, and lethal hypoglycemia [152, 155]. Despite these limitations, CGP 48664, an inhibitor derived from the MGBG, presents a promising anticancer candidate for preclinical testing [156].

Difluoromethylornithine (DFMO)

Although inhibitors for polyamine enzymes exist, DFMO is currently the most effective ODC inhibitor [133]. Once DFMO attaches to the ODC, forming an active intermediate that irreversibly inactivates it [151], causing a cytostatic effect and reducing polyamine synthesis in eukaryotic cells [157]. Extensive clinical trial research and animal studies have shown that DFMO is effective as both a single agent and in combination with other chemotherapy agents for various cancers, including glioma, skin, colon, prostate, lung cancers, and neuroblastoma [158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164] and is deemed safe with minimal side effects [165]. Its role in promoting apoptosis, especially in colon cancer cells, is critical as it significantly enhances the effectiveness of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors [165].

A recent study indicates that combining DFMO with cancer therapy increases polyamine transport when polyamines are depleted, which limits its use as a monotherapy [139]. Consequently, a more effective PBT has been developed by combining DFMO with a novel trimer polyamine transport inhibitor (PTI) [166]. The most extensively investigated PTIs are AMXT 1501 and Trimer44NMe [133]. Experiments showed PBT significantly reduced polyamine levels and tumor development compared to DFMO or PTI alone [166]. Furthermore, Hayes et al. [136] discovered that efficacy of PBT relies on T-cell immune competence, limiting immunosuppressive M2M

Hydroxylamine-containing Inhibitors

Hydroxylamine-containing inhibitors of polyamine biosynthesis, including APA (an irreversible inhibitor of ODC) and AMA (an active, site-directed irreversible inhibitor of SAMDC), have been evaluated for their effects on human colon cancer cells [169]. These compounds effectively inhibit cell proliferation and reduce intracellular polyamines. They also enhance the cytostatic effects of traditional drugs like 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) potentially serving as successful alternatives to the conventional polyamine-synthesizing enzyme inhibitors.

APA depleted ODC activity more rapidly than DFMO, and growth inhibition could not be reversed by exogenous putrescine. Unlike the conventionally used MGBG, both APA and AMA showed non-toxic effects within a concentration range that was sufficient to impair enzyme activities and inhibit growth [169]. Therefore, hydroxylamine-containing ODC and SAMDC inhibitors may serve as valuable alternatives to traditional inhibitors. However, further experiments are needed to confirm their effectiveness in the clinical treatment of various cancers.

4.2.5.2 Advances in Polyamine Analogs

Blocking polyamine synthase ODC and AMD improves polyamine transport. Polyamine analogs prevent uptake, replace natural polyamines, down-regulate ODC via antizyme, which reduces intracellular polyamines [170]. They also activate catabolic enzymes, producing ROS that induces cytotoxicity and apoptosis in tumor cells while potentially altering DNA structure and apoptotic pathways [171]. Plus, a recent study indicates polyamine analogs inhibit MAO and exhibit antiproliferative effects in LN-229 glioma cells [172]. Several common polyamine analogs are included in the Table 3 (Ref. [170, 171, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186, 187, 188]). As these findings indicate that polyamines impact cancer immunotherapy by affecting tumor immunosuppression and CD8+ T cell function. Their dysregulation is common in malignancies, highlighting their potential as a therapeutic target; however, further research is necessary. Polyamine biosynthesis inhibitors and analogs are summarized in Table 4 (Ref. [151, 189, 190, 191]).

| Compound | Structure | Mechanisms | Studied tumor types | Refs |

| DENSpm (BENSpm; BE-3-3-3) |  | Down-regulation of ODC and AMD; H2O2 production by inducing SSAT; induction of autophagy; induction of apoptosis | Pheochromocytoma, melanoma, glioblastoma, breast cancer, prostate, carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, colon cancer | [170, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179] |

| DEHSpm (BEHSpm; BE-4-4-4) |  | Down-regulation of ODC and AMD; up-regulation of SSAT | Solid tumors, brain tumors U-87Mg and SF-126, non-small cell lung cancer, prostate cancer, leukemia, melanoma cell line MALME-3 | [171, 180] |

| CPENSpm |  | Up-regulation of SSAT, strong cytotoxicity | Breast cancer, lung tumor | [170, 171, 181, 182] |

| CGC-11047 (PG-11047) |  | Induction of SMO and SSAT, down-regulation of ODC, cytotoxicity, affects gene and signaling pathways | Advanced solid tumors, small cell and non-small cell lung cancer, colon cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer | [170, 183, 184, 185, 186, 187] |

| SL11144 |  | Down-regulation of ODC, induction of apoptosis, inhibitor of lysine-specific demethylase 1 | Breast cancer | [188] |

| Category | Inhibitor/Analogue | Mechanisms | Applications | Refs |

| Polyamine biosynthesis inhibitors | DFMO | Inhibits ODC, leading to accumulation of pro-apoptotic proteins p53 and MDM2. | Used in clinical trials, often in combination with other drugs to enhance antiproliferative effects. | [189] |

| MGBG | Inhibits SSAT, preventing compensatory reactions that limit the effectiveness of single enzyme inhibitors. | Tested in various cancer models and clinical trials, promise in inhibiting tumor growth. | [189] | |

| AdoMetDC Inhibitors (e.g., SAM486A) | Inhibits S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (AdoMetDC), leading to accumulation of pro-apoptotic proteins. | Used in experimental animal models and clinical trials to target cancer cells. | [190] | |

| Polyamine analogues | Verlindamycin | Decreases polyamine levels and induces antizyme production, leading to downregulation of the PI3K-mTOR pathway. | Shows antitumor effects by modulating polyamine metabolism. | [151] |

| PG11047 | A conformationally restricted polyamine analogue that lowers cellular endogenous polyamine levels and competitively inhibits natural polyamines. | Demonstrates anticancer activity in cells and animal models of multiple cancer types. | [191] | |

| Bisaryl-Polyamine Analogues | Designed to inhibit the penetration and replication of pathogens such as Trypanosoma cruzi within mammalian host cells. | Used in the treatment of parasitic infections and show promise in inhibiting cancer cell growth. | [191] | |

| Polyamine Phosphinate and Phosphonamidate Analogues | Transition-state inhibitors of SSAT, mimicking the transition state of the enzyme-substrate complex. | Synthesized and tested for their antineoplastic properties, showing potential in cancer therapy. | [151] |

Despite extensive studies on the human body’s benefits, polyamine research is growing and needs further exploration into their functions and metabolism. Since different polyamines affect health outcomes, research should prioritize human practices rather than relying on animal trials. Additionally, understanding how metabolic links are disrupted is crucial for understanding interactions between wellness and disease. Recognizing these research limitations will help address polyamines’ potential positive effects in the gut.

Polyamines rebuild gut epithelium, maintain mucosal homeostasis, and protect against stress, primarily sourced from gut microbiota, with their metabolism vital for gut health. Research highlights their health benefits, especially in intestinal maturation and epithelial cell maintenance. However, these compounds are also linked to various diseases, indicating further studies on their effects, dosages, and administration are needed. Additionally, polyamines are essential for the differentiation and function of immune cells, including T cells, M

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9. Schematic summary of the polyamine function. Polyamines are widely distributed in the body, influencing immune cell differentiation and intestinal protection, while also being potential cancer targets. However, they can be toxic and teratogenic in excess, act as pseudoneurotransmitters in hepatic encephalopathy, and promote tumor immunosuppression by affecting the TME. Created using BioRender.com.

[Ca2+]cyt, cytoplasmic free Ca2+; AdoDATAD, S-adenosyl-1,12-diamino-3-thio-9-azadodecane; AdoDATO, S-adenosyl-3-thio-1,8-diamino-3-octane; AhR, aromatics receptor; AMD, S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; AP-1, activating protein 1; AZIN, antizyme inhibitor; AZs, antizymes; BAs, biogenic amines; BBB, blood-brain barrier; BM, bone marrow; CadA, lysine decarboxylase; CCL2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; CCL3, C-C motif chemokine ligand 3; CD8+ T cells, cytotoxic T cells expressing cell-surface CD8; Cdc42, cell division control protein 42; CDK4, cyclin-depen-dent kinase 4; CUGBP1, CUG-binding protein 1; CXCL-1, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1; DAO, diamine oxidase; DAX, diamine exporter; DC, dendritic cells; dcSAM, decarboxylated SAM; DFMO, difluoromethylornithine; DHPS, deoxyhypusine synthase; DOHH, deoxyhypusine hydroxylase; EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; eIF5A, eukaryotic initiation factor 5A; FAO, fatty acid oxidation; Foxp3, ForkheadBoxP3; GABA,

XY, HG, JX wrote the draft. SX, XHL, YL, LP, WS, HW, XL polished the figures. XY, SX, XHL, XL analyzed the data. XY, WS, YL, LP, HW drew the graph and expanded the literature. HG and JX analyzed all the data and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The sharper figures utilized in this review were created using BioRender.com. We extend our gratitude to all peer reviewers for their valuable insights and constructive suggestions, which significantly enhanced the quality of this manuscript.

This work was funded by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No.7242211), and National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant (No.82174056).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.