1 Department of Pharmaceutics and Pharmaceutical Technology, L M College of Pharmacy, 380009 Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India

2 Department of Pharmacology, L M College of Pharmacy, 380008 Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India

3 Now with Department of Pharmacology, Anand Pharmacy College, 388001 Anand, Gujarat, India

4 School of Pharmacy, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, 200030 Shanghai, China

5 Laboratory of Drug Development and Technologies, Faculty of Pharmacy of the University of Coimbra, University of Coimbra, 3000-272 Coimbra, Portugal

6 REQUIMTE/LAQV, Group of Pharmaceutical Technology, Faculty of Pharmacy of the University of Coimbra, University of Coimbra, 3000-272 Coimbra, Portugal

7 Pharmacy Section, L M College of Pharmacy, 380009 Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India

8 School of Health and Biomedical Sciences, RMIT University, Bundoora, VIC 3083, Australia

9 School of Pharmacy, Queen’s University Belfast, BT9 7BL Belfast, UK

Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak has many unexpected implications, but the scientific community remains optimistic about overcoming these obstacles. Adenoviruses (Ad) are considered the most suitable vectors for transferring specific antigens to mammalian cells since they can induce both innate and adaptive immune responses. Ad-based coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). vaccines were granted emergency use authorization in the COVID-19 pandemic. Many features of the Ad vector render it an appealing vaccine carrier for contagious diseases, including high titer, ease of processing, high effectiveness, low immunogenicity in clinical trials, and consistency in pharmaceutical packaging and shipment processes. Ad-based vaccines are generally effective and have few side effects since Ad induces minor infections in humans, and genetic modifications can block viral replication. These single-dose vaccines are effective not only in young individuals but also in adults. Clinical trials of these single-dose vaccines are commendable and have shown excellent safety and efficacy profiles. This review provides a summary of the development of single-dose vaccines against SARS-CoV-2.

Keywords

- single-shot/dose vaccine

- SARS-CoV-2

- adenovirus

- COVID-19

- Janssen vaccine

- Sputnik Light vaccine

- convidicea

- Ad26.COV2.S

- Ad26

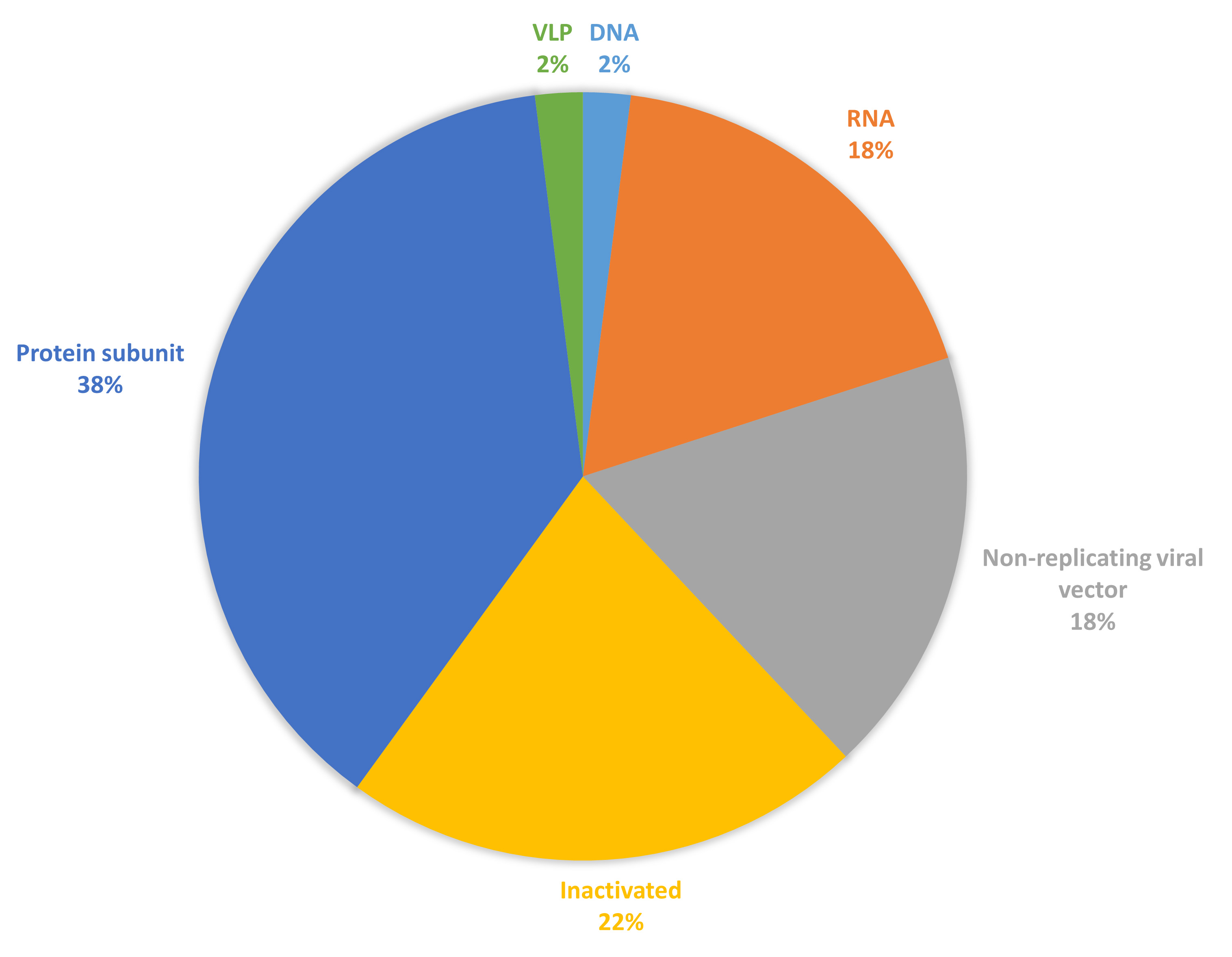

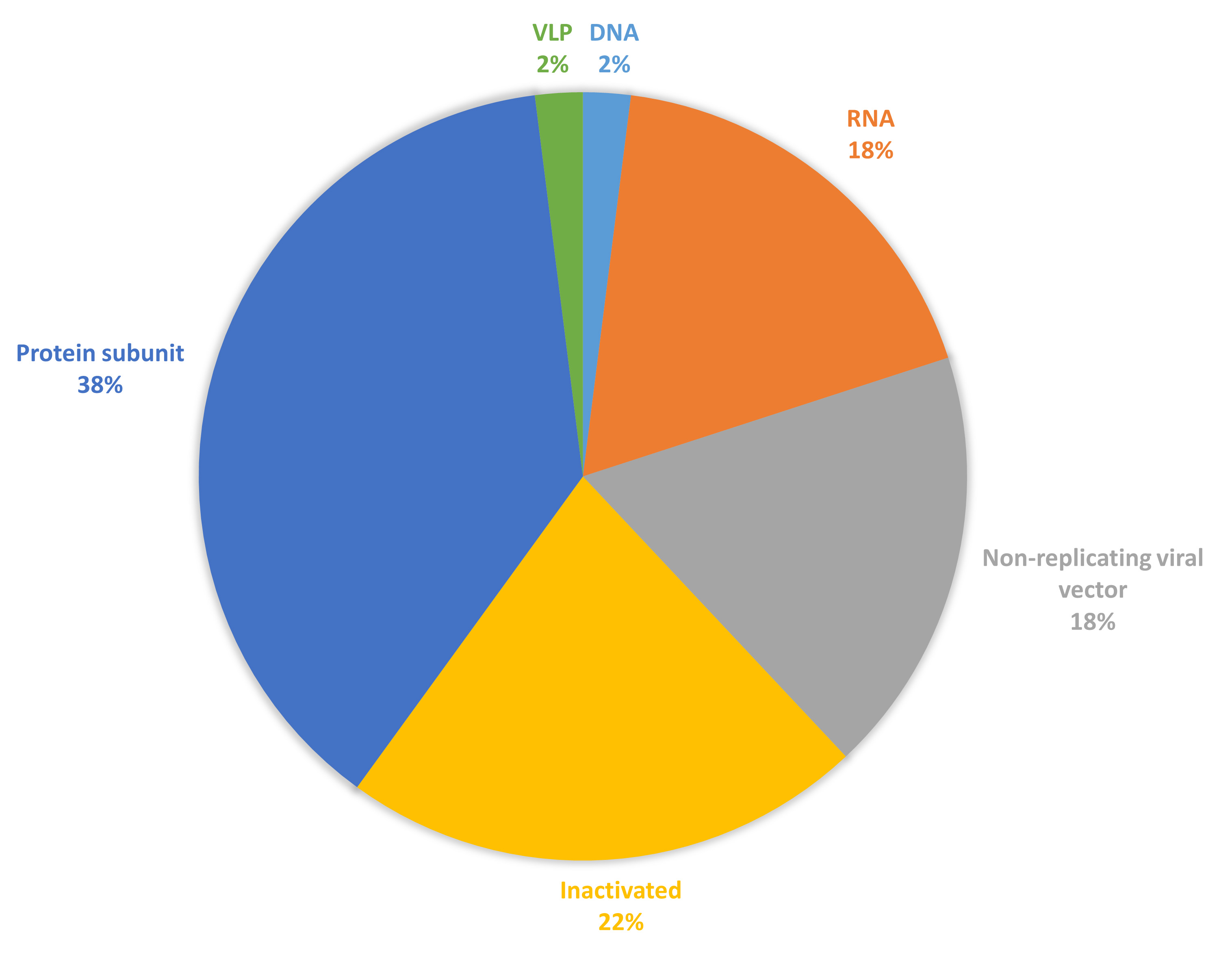

Since the release of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) gene sequence, several safe and efficacious vaccine candidates against SARS-CoV-2 have been developed [1]. On 12 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared SARS-CoV-2 a pandemic [2, 3]. All traditional diagnostic methods and treatments are ineffective and are limited by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [4]. This scarcity of management even incorporated fraudulent products, which were eventually recognized by the WHO and other authorities [5, 6]. Vaccination is a key element in the management of SARS-CoV-2 infection because of rapid development. This initiative saved the world [7]. The vaccine candidates aim to elicit strong immune responses to provide effective protection against COVID-19, targeting both antibody and T-cell responses. By December 2022, over 250 new vaccine candidates for SARS-CoV-2 were in diverse phases of development, encompassing both preclinical studies and clinical trials [8]. By December 2024, 50 vaccines had received approval in 201 countries and 12 were granted Emergency Use Listing by WHO, showcasing a range of platforms, including protein subunits, nucleic acids (such as mRNA and DNA), live attenuated viruses, and viral vector-based vaccines [8]. Each of these formulations employs different mechanisms to stimulate the immune system, providing various options for vaccination strategies [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. The proportion of these different vaccine types is shown in Fig. 1 (Ref. [15]), reflecting the diverse strategies used in vaccine development. Understanding the distribution and characteristics of these formulations is crucial for assessing their efficacy, safety, and public health impact against COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Vaccine candidates for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are under clinical development (data collected from [15]). Figure created using excel (Abbreviation: DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; RNA, ribonucleic acid; VLP, virus like particle).

Adenovirus (Ad)-based vector vaccines hold great promise for effectively preventing or reducing the effects of COVID-19 (Fig. 1), offering the advantage of a single dose. These vaccines use a modified Ad to deliver genetic material encoding a specific viral antigen, stimulating both antibody and T-cell responses. However, the constantly evolving nature of the virus poses challenges to their efficacy, necessitating ongoing adaptation and research to maintain their effectiveness. The rise of mutant strains of SARS-CoV-2, such as alpha, beta, gamma, delta, delta plus, and omicron strains, has spread across many parts of the world [16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. Recombinant strains such as XD, XF, XE, and others currently exist in the population with XEC, the latest reassortment variant. For the current scenario, multiple doses (even booster doses) are required to produce appropriate immunity. In addition to their use in COVID-19 vaccines, Ad vectors have been used as delivery vehicles for various vaccines, including those for influenza, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and Ebola. However, further clinical research is needed to fully evaluate and understand the potential of Ad vectors and uncover their advantages [21].

One dose of Janssen (JNJ-78436735 or Ad26.COV2.S) or CanSino vaccine (individually) stimulates neutralizing antibodies, protecting individuals from SARS-CoV-2-related diseases such as pneumonia and mortality. There are several Ad vector-based vaccines available. The vaccine candidate from Janssen (Ad26.COV2.S) (Netherlands and USA) is a rAd26 vector-based vaccine, whereas the Chinese CanSino Biologic vaccine is an rAd5 vector-based vaccine. Gamaleya vaccination (rAd26) is followed by booster vaccination with the Ad5 serotype with a similar transgene. These vaccines offer numerous benefits as human vaccines, including the ability to be produced in high titers within the cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) guidelines, effectiveness, and induction of a positive immunological response in people [22]. They are linear, double-stranded DNA viruses that are nonenveloped and have a transgene packing capacity of up to 8 kb owing to the deletion of the E1 and E3 genes. There is no reason to achieve a “one-size-fits-all” effective antiviral immune response. Ad promotes robust innate immune responses in host species [23, 24, 25, 26]; this response includes both humoral and cellular immunity.

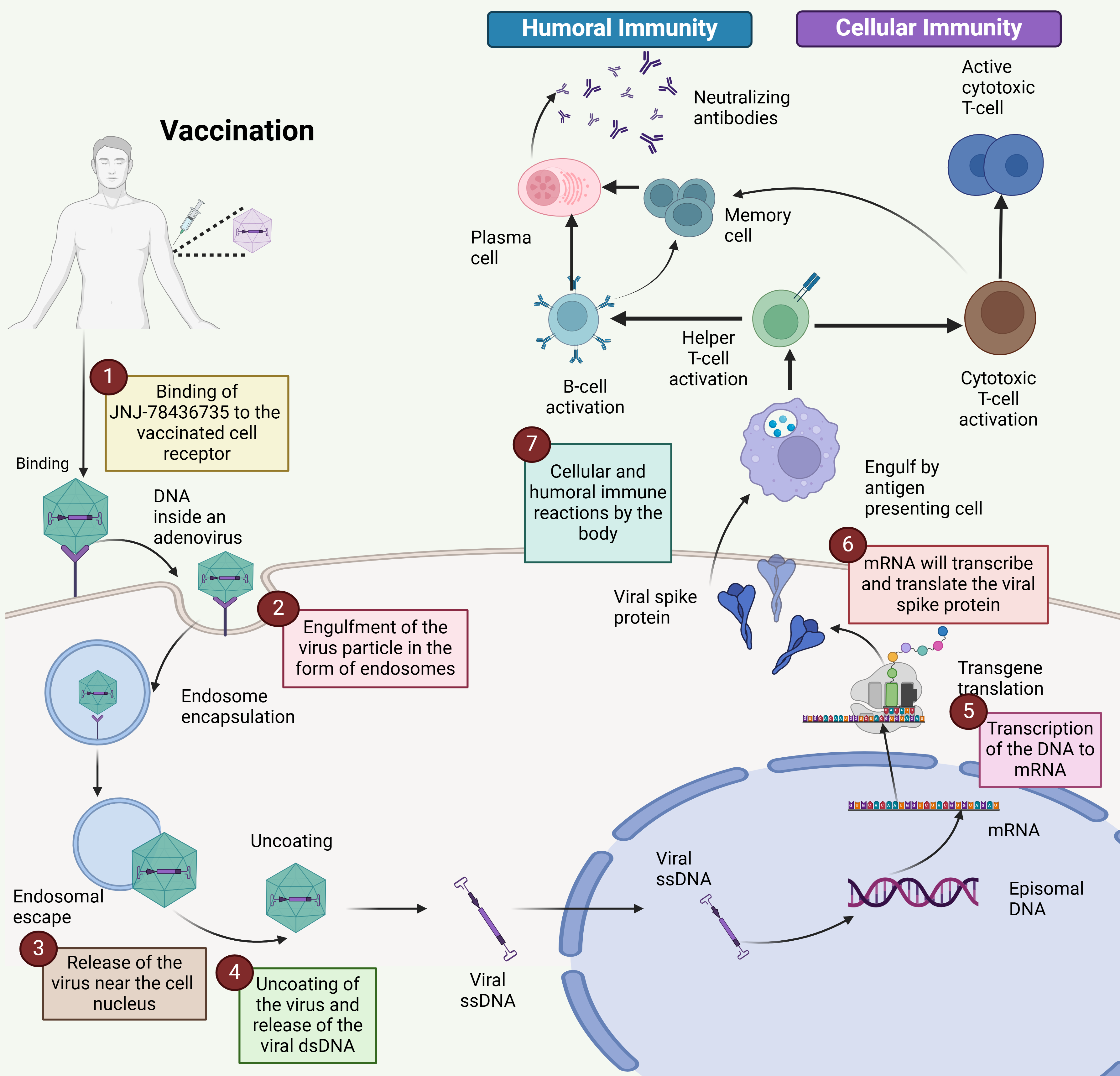

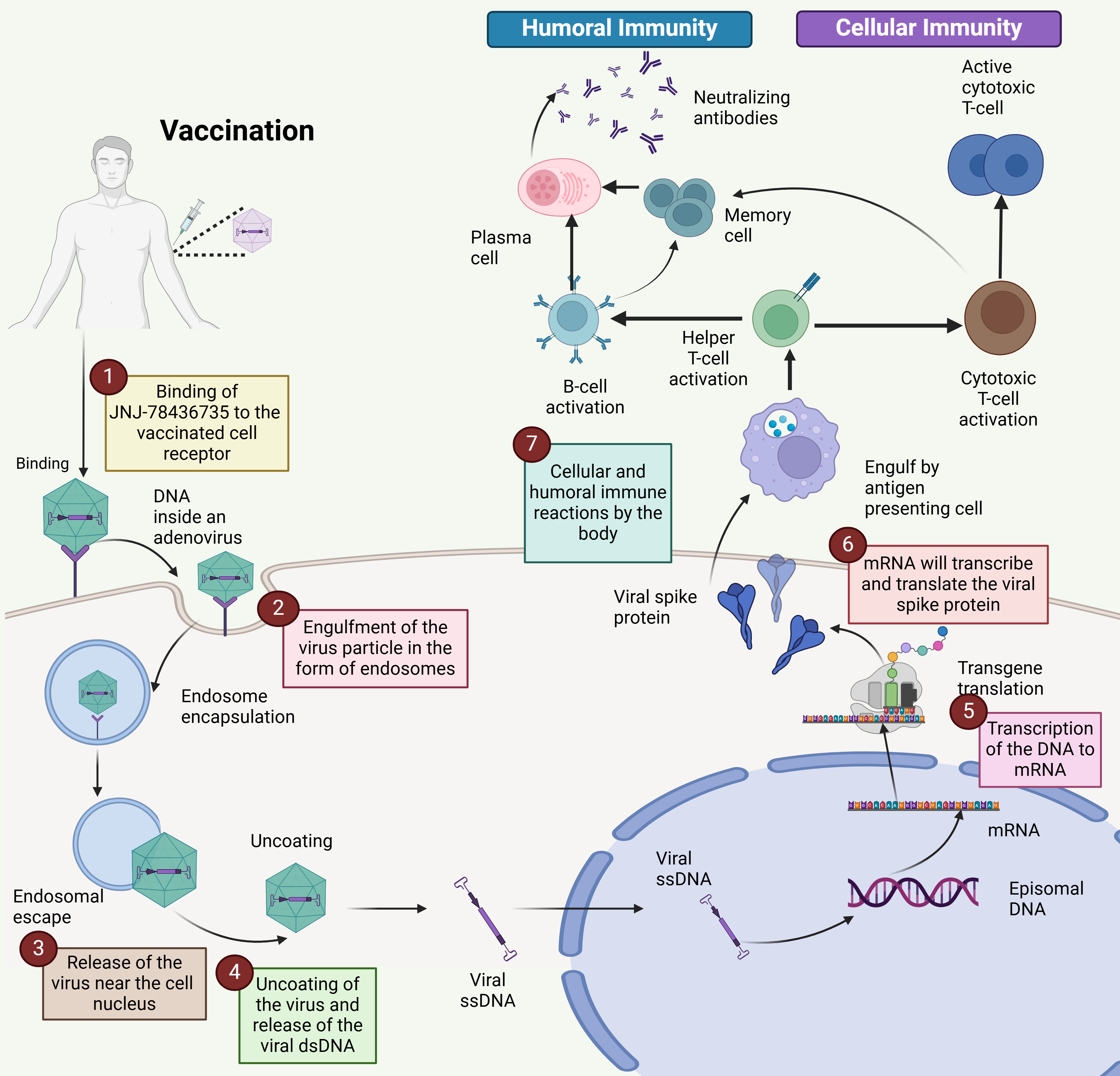

The viral genome comprises six genes encoding different proteins upon transcription (denoted as E1 to E4; L1–L5). Early transcription components are essential for viral DNA replication and immune evasion, whereas late transcription units are involved in viral assembly [27]. They lack the E1 transcription unit (first-generation vectors), which makes them replication incompetent and increases the vector capacity close to 5 kb in size. Many first-generation vectors lack E3, which increases the vector capacity up to 7.5 kb [28, 29]. The deletion of several transcription units has several benefits, including lower Ad-associated immunity and vector capability enhancement. Postvaccination, the Ad vector-based single-dose vaccine enters the cell by attaching to the integrin entry receptors present on the cell surface via endocytosis; the virus particle is captured by the cell membrane and transported inside the cell with a circular coating consisting of special channels. The Ad usually incorporates different pathways that are different for both entry and exit [30]. Virus particles are taken up by antigen-presenting cells, such as macrophages and dendritic cells. Once inside the cell, the virus uncoats, releasing its double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genome into the nucleus. Here, the viral genes are transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA then exits the nucleus and is translated into spike proteins by ribosomes in the cytoplasm. These spike proteins are processed within the cell, and fragments are presented on the cell surface by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules (Fig. 2). These findings suggest that antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells circulate in the blood, leading to their activation. Additionally, some spike proteins are released outside the cell, where they are recognized and taken up by B lymphocytes, triggering their activation. Antigen-presenting cells can also internalize spike proteins and process and present small antigenic fragments on their surface in complex with MHC class II molecules, further engaging in the immune response [31].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Mechanism of the single-dose vaccine for COVID-19. The mechanism of action of the single-dose COVID-19 vaccine Ad26.COV2.S involves several key steps: (1) Binding: The vaccine binds to receptors on the surface of the vaccinated cell. (2) Endocytosis: The vaccine particle is engulfed by the cell, where it forms an endosome. (3) Viral release: A vaccine releases its contents near the cell’s nucleus. (4) Uncoated: The viral particle is uncoated, releasing its double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). (5) Transcription: Viral DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA). (6) Protein synthesis: mRNA is translated into the viral spike protein. (7) Immune response: This spike protein triggers both cellular and humoral immune responses, facilitating an adaptive immune response against the virus. The Ad vector-based single-dose vaccine initiates a sequence of cellular processes that lead to the production of the viral spike protein and the activation of the body’s adaptive immune system (Created with Biorender.com).

COVID-19 vaccines use different mechanisms to induce immune responses against SARS-CoV-2. mRNA vaccines, such as COMIRNATY (Pfizer) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna), introduce mRNAs that encode the spike protein, causing cells to produce the protein, which then triggers an immune response. Protein subunit vaccines, such as Nuvaxovid (Novavax), directly deliver preformed spike proteins to stimulate antibody production without the use of genetic material. DNA vaccines, such as ZyCoV-D, deliver DNA encoding the spike protein, which is transcribed into mRNA within cells, ultimately leading to protein production and immune activation. Ad-based vaccines employ a viral vector to deliver the spike protein-encoding gene into cells, where the protein is produced, stimulating the immune system (Fig. 2).

Ad is a vector of choice for vaccine development. They hold great promise in fighting respiratory viral diseases for which there are no suitable vaccines or for which the traditional vaccination technique is unsuccessful [32]. As these vaccines induce innate and adaptive immune responses, Ad are excellent vectors for the delivery of target antigens to mammalian hosts. This vaccine platform also favors intranasal vaccination because of its ability to elicit localized secretory IgA-based responses [27]. Table 1 (Ref. [8, 15, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48]) summarizes information related to nine approved Ad-based vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 [32, 49].

| Vaccine | WHO approved | Clinical trials | Commercialization | Country of origin | Route | Reference |

| Convidicea (Ad5-nCoV) | Yes | 14 trials in 6 nations | 10 nations | China | Intramuscular | [33, 34, 35, 36] |

| iNCOVACC (BBV154) | No | 4 trials in 1 nation | 1 nation | India | Intranasal | [37] |

| CanSinoBio | No | 5 trials in 4 nations | 2 nations | China | Intramuscular | [15] |

| Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca formulation) | Yes | 6 trials in 1 country | 49 nations | India and UK | Intramuscular | [36, 38, 39] |

| Vaxzevria | Yes | 73 trials in 34 nations | 149 nations | Sweden | Intramuscular | [8, 40] |

| Gam-COVID-Vac | No | 2 trials in 0 country | 1 nation | Russia | Intramuscular | [41] |

| Sputnik V | No | 25 trials in 8 nations | 74 nations | Russia | Intramuscular | [36, 42, 43, 44] |

| Sputnik light | No | 7 trials in 3 nations | 26 nations | Russia | Intramuscular | [33, 36, 45] |

| Jcovden (JNJ-78436735, Janssen COVID-19 or Ad26.COV2.S) | Yes | 26 trials in 25 nations | 113 nations | The Netherlands | Intramuscular | [43, 46, 47, 48] |

WHO, World Health Organization.

Recombinant Ad vectors have excellent safety records [50]. Ad are generally preferred as vectors for vaccine delivery because of their strong immunogenicity, eliciting robust antibody, and CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses [51]. The incorporation of a gene cassette of interest into the Ad backbone produces recombinant Ad vaccines. Technological advances in Ad vector design, viral manufacturing for propagation, localized immunity, and systemic immune response should speed up Ad vector vaccine engineering against respiratory viral infections for which practical vaccination approaches are not available [52]. In addition, an emerging pandemic scenario will involve enhanced immunogenicity at lower doses and the capability to lyophilize or stabilize vaccines. This will support dose conservation, improve cost-effectiveness, and enhance preparedness for pandemics. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are expressed to stimulate the innate immune response. When PAMPs interact with the virus recognition receptors on host cells [53, 54], they trigger the production of proinflammatory cytokines and the activation of antigen-presenting cells [55, 56]; SARS-CoV-2 can interact with several different host receptors. Further, Ad-based vaccines, such as Sputnik V and Janssen (Ad26.COV2.S) COVID-19 vaccine, offer several advantages, including high thermostability, ease of production at high titers, and flexibility in administration (systemic or mucosal) [42, 57]. Sputnik V, produced using the HEK293 cell line, combines two Ad vectors (Ad26 and Ad5) with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Its purification involves tangential flow filtration and chromatography to ensure quality and safety [42]. Ad26.COV2.S vaccine uses an rAd26 vector encoding the spike protein and variants, with the MN908947 isolate stabilized in a prefusion conformation [48]. The Ad26 vector is modified to prevent replication by deleting the E1 gene, which requires a special cell line (derived from fetal retinal tissue) for production [58, 59, 60]. These vaccines induce neutralizing antibodies and a Th1-biased immune response, and their manufacturing process is scalable and industry-friendly [61, 62]. Standard storage is cold (2–8 °C) for up to 3 months or frozen (–20 °C) for up to 24 months—though multiple freeze-thaw cycles should be avoided [48].

Infection with SARS-CoV-2 typically progresses to moderate infectious disease in

animal models such as hamsters and nonhuman primates. Preclinical COVID-19

vaccine studies in nonhuman primates have demonstrated reduced viral replication

in the respiratory tract following vaccination [33, 63]. In one preclinical study

of Ad26.COV2.S, 52 rhesus macaques were immunized with adenovirus type 26 (Ad26)

vectors encoding different variants of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Each monkey

received 1

In phase 1 and phase 2 trials of the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine, a total of 1045

participants were administered intramuscular injections of the vaccine at two

dosage levels, high and low, on day 1 and day 57 (NCT04436276) [69]. Preliminary

findings indicated that even a single dose of Ad26.COV2.S could elicit a strong

immune response and the vaccine was generally well tolerated [46, 70]. Adverse

event monitoring was conducted 7 days and 28 days after vaccination to ensure the

safety profile of the vaccine. The secondary objective of this study was to

assess both the humoral and the cellular immune responses generated by the

vaccine [46]. At a dosage of 5

Phase 2 trials for Ad26.COV2.S and other Ad-based vaccines further evaluated the

adaptive immune response postvaccination, particularly focusing on neutralizing

antibodies and the broader immune response across different dosage levels. For

Ad26.COV2.S, these trials involved participants aged 18–56 years who received

intramuscular injections at three dosage levels (NCT04535453) [74]. The trials

also evaluated the efficacy and reactogenicity of Ad26.COV2.S when it was

administered as either a single-dose or two-dose regimen in adolescents aged

12–17 years. Additionally, the study tested compressed (28-day) and extended

(84-day) two-dose schedules in adults aged 18–65 years and older [46, 74]. The

flexibility of dosing schedules is particularly important for optimizing vaccine

distribution in different populations and scenarios. In a related phase 2 study

of the Ad5-nCoV vaccine, two concentrations of viral particles (1

When comparing the Ad26.COV2.S, Sputnik Light, and Ad5-nCoV vaccines, several key features stand out. Ad-based vaccines, including Ad26.COV2.S and Sputnik Light, use viral vectors to deliver the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, eliciting both antibody and T-cell immune responses. The data from early-phase trials for Ad26.COV2.S show that even a single dose can generate a significant immune response, making it a practical option for large-scale immunization, especially in regions where logistics may limit the feasibility of multidose schedules. Similarly, Sputnik Light’s ability to induce binding antibodies in 100% of participants and neutralizing antibodies in more than 80% of participants shows its efficacy as a single-dose option, which has proven effective in reducing hospitalizations and preventing severe illness [71, 72]. In comparison, the Ad5-nCoV vaccine also demonstrated robust immunogenicity, with high percentages of participants developing cellular and humoral immunity within 28 days of vaccination, regardless of the dosage level [75]. While both Ad26.COV2.S and Ad5-nCoV provide promising data on single-dose regimens, Ad26.COV2.S flexibility in dosage schedules, compressed or extended, adds an additional advantage for tailoring immunization strategies across different populations.

Based on the results of phase 1 and phase 2 human clinical trials, the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine candidate was chosen for further study in the phase 3 ENSEMBLES clinical trial [76]. This trial was planned to assess the potency, safety, bioavailability, and tolerability of a single-dose vaccine. A total of 44,325 participants were randomly assigned, with 43,783 receiving either Ad26.COV2.S or a placebo. In addition to chills, redness of the skin, pain, or other minor flu-like symptoms, none of the participants experienced any significant side effects. The vaccine’s efficacy was reported to be 66.9% at 14 days postvaccination, during which it declined to 66.1% at 28 days. The effectiveness of Sputnik Light was 79.4% according to a review of data from the 28th day following immunization as part of the mass vaccination program from December 5, 2020, to April 15, 2021; approximately 7000 individuals took part in international clinical trials for Sputnik Light [69, 77]. According to the interim review results from CanSino’s phase 3 clinical trial, it has an average effectiveness of 65.2% for preventing symptomatic cases after 28 days of a single dose and 68.8% for COVID-19-positive cases [78, 79]. The preliminary results from phase 3 clinical trials, which were conducted with over 4000 participants across Pakistan, Mexico, Russia, Chile, and Argentina, revealed the significant efficacy of the single-dose vaccine. Specifically, it shows 90.07% efficacy in preventing severe disease 28 days after vaccination and 95.47% efficacy 14 days postvaccination [78, 79]. The calculation of vaccine efficacy includes direct (vaccine-induced) and indirect (population-related) defenses. It differs from vaccine efficacy, which assesses how well a vaccine does when it is administered to patients outside clinical trials [80]. Different variants are prevalent globally, causing another wave of the pandemic that requires quick medical attention [81, 82, 83, 84].

COVID-19 vaccines are designed to generate immune responses that neutralize SARS-CoV-2 and prevent the virus from binding to host receptors. In addition to stimulating humoral immunity, these vaccines also activate cellular immune responses to eliminate infected cells and restrict viral replication [85, 86]. A key focus is the development of neutralizing antibodies targeting the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, which are crucial for effective protection [87]. Ad-based vaccines, such as Ad5 and Ad26.COV2.S, have demonstrated significant efficacy. For example, Ad5 vaccines showed 62.5%, 67.8%, and 100% efficacy against symptomatic COVID-19, pneumonia, and critical COVID-19, respectively, when compared to the Delta variant [88]. The Ad26.COV2.S vaccine showed 73.1% efficacy after a single dose, further supporting the feasibility of single-dose vaccines [68, 69]. These vaccines generate both humoral and cellular immune responses, typically with a Th1 immune profile, which is associated with strong protection [46]. A limitation of Ad-based vaccines is that after the first dose, the immune system generates antibodies against the Ad vector, which can reduce the effectiveness of subsequent doses using the same vector serotype [89, 90]. However, vaccines like Ad26 have been shown to induce long-lasting immunity, making them suitable for pandemic use when repeated doses may not be feasible. These vaccines stimulate spike-specific IgG and IgA responses, further enhancing immune protection [64]. The efficacy of Ad vector-based vaccines also varies depending on the type of vector used. For example, single-cycle Ad vectors produce much higher levels of spike protein compared to replication-defective Ad vectors. In a preclinical study with Syrian hamsters, single-cycle Ad vectors produced 100 times more spike protein and provided protection for more than 10 months, with antibody levels continuing to rise at 14 weeks postvaccination [91]. This suggests that single-cycle Ad vector-based vaccines could offer long-term immunity with just one dose, reducing the need for boosters. mRNA vaccines, such as Pfizer-BioNTech’s BNT162b2, have also shown strong efficacy. A study comparing the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine and the mRNA-based BNT162b2 found no significant difference in hospitalization or mortality rates among patients receiving either vaccine, although the study focused on dialysis patients, which may limit the broader generalization of the results [92]. Both vaccine platforms are effective, though mRNA vaccines generally require multiple doses and have more complex storage requirements compared to Ad vector-based vaccines. Single-dose vaccines offer several advantages, including cost-effectiveness, ease of distribution, and reduced logistical complexity, especially in emergency situations. By minimizing the need for multiple doses, they simplify vaccination campaigns and increase compliance. Ongoing research is focused on improving the durability, immune response, and coverage against variants of concern, making single-dose vaccines a promising strategy for global pandemic preparedness.

All these vaccines have the potential to cause adverse effects [93, 94, 95, 96]. Unexpected issues may arise, and they may be life-threatening or mild/moderate. Side effects are widespread in clinical trials within 7 days of vaccination, but they are mainly mild to moderate [93]. The common side effects include swelling, pain, and redness at the injection site, and the systemic side effects include chills, muscle pain, nausea, etc. Another major side effect was fever, which resolved within 12 hours [94]. Following the introduction of Ad26.COV2.S vaccine in the US, six women developed a rare blood-clotting illness; nevertheless, mass immunizations with the Sputnik vaccine revealed no occurrences of clots or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. The clots that are tentatively linked to Ad26.COV2.S vaccinations have distinct traits: they appear in uncommon bodily regions and are connected to lower platelet levels, which are cell fragments that aid in blood clotting. Further research revealed further indicators of the unique adverse effects in people known as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). Among the 579,301 total vaccinated individuals with COVID-19, 57 were confirmed to have HIT, of which fifty-four cases and three cases were after Ad26.COV2.S and mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, respectively [97, 98]. Thrombosis is a very rare occurrence, similar to how allergic responses to polyethylene glycol in certain vaccinations are modest and extremely infrequent [99]. However, the likelihood of developing HIT-like clotting conditions is extremely low, with just 86 potential instances reported in Europe out of 25 million people vaccinated [100]. After receiving the Sputnik Light vaccine, no serious adverse effects were reported. A million Ad5-nCoV vaccines (CanSino Biologics’ COVID-19 vaccine) have been administered, and no significant side effects from blood clots have been reported. Men receiving Ad-5-based vaccination have an increased risk of contracting HIV-1 because the vaccine boosts CCR5-positive CD4+ T cells, according to a recent publication [101]. Recently, AstraZeneca initiated the global withdrawal of its COVID-19 vaccine, Vaxzevria, which was attributed to an abundance of updated vaccines available since the onset of the pandemic. Concurrently, the company has opted to retract the vaccine’s marketing authorizations within Europe. The main reason behind this is the low efficacy against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants and the presence of other superior vaccines on the market. Previously, the Anglo-Swedish pharmaceutical company acknowledged in legal documents that the vaccine could lead to adverse effects such as blood clots and decreased blood platelet counts.

COVID-19 vaccine research and clinical trials are progressing at an exponential pace. mRNA and Ad vector-based vaccines will be critical in fighting this global catastrophe. Nonreplicating Ad vectors are considered promising carriers for vaccines against infectious diseases due to several advantages: they can be produced in high yields, are compatible with cGMP manufacturing processes, have a favorable safety profile, demonstrate efficacy in clinical trials, and are relatively easy to ship and store. Once inside, the host cells express this protein, triggering a cascade of immune responses [102].

Ad-based vaccine delivery platforms are also well suited for the development of nasal vaccines, and several research teams are exploring these options as part of their booster dose strategies. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has led to many unforeseen consequences, yet the scientific community remains optimistic about addressing these challenges. Increased routine immunization will shed light on several critical aspects of SARS-CoV-2 immunity. As larger populations are vaccinated, including those with suboptimal immunity, the durability of immunity generated by various vaccine approaches and the nuances of the immune responses elicited will become clearer. Throughout the COVID-19 crisis, rational decision-making, urgency in vaccination efforts, and rigorous management practices may have emerged. It is essential to promote discussions among professionals in the field, and further research is necessary to improve vaccine safety and significantly reduce thrombotic events in individuals [99]. The maintenance of immune responses may be a notable feature of Ad vector-based vaccines, with some evidence suggesting that these vaccines play a role in initiating prolonged immune responses and providing long-term protection [103]. While this ability to induce lasting immunity is not exclusive to Ad-based vaccines, it is an important consideration when evaluating their potential for sustained protection. Long-term safety and efficacy data will help determine the optimal dosage regimen for Ad vector-based vaccines. However, further research is needed to optimize the dosing strategies for all vaccine platforms, including Ad-based vaccines, to ensure the most effective single-dose regimens with proven efficacy.

In conclusion, Ad26.COV2.S, Sputnik Light, and Ad5-nCoV demonstrate that Ad-based vaccines can induce strong immune responses with a favorable safety profile, positioning them as crucial tools in the fight against COVID-19 worldwide. Their ability to induce both humoral and cellular immunity, combined with flexible dosing schedules and easy storage requirements, makes them highly suitable for large-scale immunization efforts worldwide.

When comparing Ad-based vaccines such as Ad26, Sputnik Light, and Ad5-nCoV to protein-based vaccines, key differences become apparent. Ad-based vaccines use viral vectors to deliver the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein or its genetic blueprint, eliciting a robust immune response involving both antibodies and T cells. In contrast, protein-based vaccines such as Novavax deliver the spike protein directly, often necessitating adjuvants to increase their immunogenicity. While protein-based vaccines elicit strong antibody responses, they generally induce weaker cell-mediated immune responses than Ad-based vaccines. Other vaccine platforms, such as mRNA vaccines (e.g., Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna), introduce genetic instructions for the spike protein into cells, where the protein is synthesized and triggers an immune response. These vaccines are highly effective at generating neutralizing antibodies and T-cell responses, although they require stringent cold-chain storage conditions, which can present logistical challenges in certain regions. In contrast, Ad-based vaccines are more stable and can be stored at standard refrigeration temperatures, offering advantages for large-scale distribution, especially in areas with limited cold-chain infrastructure. Each vaccine type, whether Ad-based, protein-based, or mRNA, has distinct advantages and limitations. Ad-based vaccines elicit broad immune responses and offer greater stability; however, preexisting immunity to the Ad vector in some individuals may reduce efficacy. Protein-based vaccines are generally more stable and easier to distribute but may require additional components, such as adjuvants, to enhance their immune response. mRNA vaccines, while providing strong protection, face challenges due to their storage requirements. To address this, next-generation thermostable lipid nanoparticle-mRNA vaccines, which maintain room-temperature stability and induce robust neutralizing antibody responses, are currently being tested in human clinical trials, showing complete protection in animal models [104]. The choice of vaccine platform depends on the specific goals of immunization campaigns, distribution logistics, and the need for both antibody and cellular immunity in various populations.

One of the significant advantages of Ad-based vaccines is their relatively easy storage and transport, requiring only standard refrigeration, unlike mRNA vaccines such as Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, which require ultracold storage. Additionally, while protein-based vaccines such as Novavax elicit strong antibody responses, they may require adjuvants and multiple doses to achieve the same level of immunity as Ad-based vaccines. This highlights the utility of Ad-based vaccines, particularly for regions with limited access to healthcare infrastructure or where rapid distribution is necessary. Ad-based vaccines hold significant promise for rapid development and deployment in response to emerging infectious diseases. The ability of these vaccines to elicit strong immune responses and their potential for easy modification makes them advantageous over traditional protein-based vaccines, which often require longer production times and may induce weaker responses. Additionally, Ad-based vectors can accommodate larger genetic inserts, allowing for the inclusion of multiple antigens. As global vaccination efforts expand, Ad-based platforms could increase vaccine accessibility and effectiveness, particularly in low-resource settings. Their versatility positions them as key players in the future of vaccine development, complementing existing technologies.

VPC contributed to the conceptualization, original draft preparation, review, and editing of the manuscript. PCB contributed to the literature survey, original draft preparation, review and editing, and creation of figures. LV contributed to the validation of literature, supervision, visualization, and creation of figures. VA contributed to validation, original draft preparation, review and editing, and supervision. HZ, FR, AAM, and ACP contributed to the literature survey, original draft preparation, and editing of the manuscript with revisions. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript, have read and approved the final version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Not applicable.

All authors would like to thank their respective Institutions for their support.

This research received no external funding.

Given her role as the Editorial Board member, Vasso Apostolopoulos had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Giuseppe Murdaca.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.