1 Hubei Selenium and Human Health Institute, The Central Hospital of Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, 445000 Enshi, Hubei, China

2 Hubei key Laboratory of Hospital Chinese Medicine Preparation and New Drug Commercialization, The Central Hospital of Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, 445000 Enshi, Hubei, China

3 Hubei Provincial Key Lab of Selenium Resources and Bioapplications, 445000 Enshi, Hubei, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

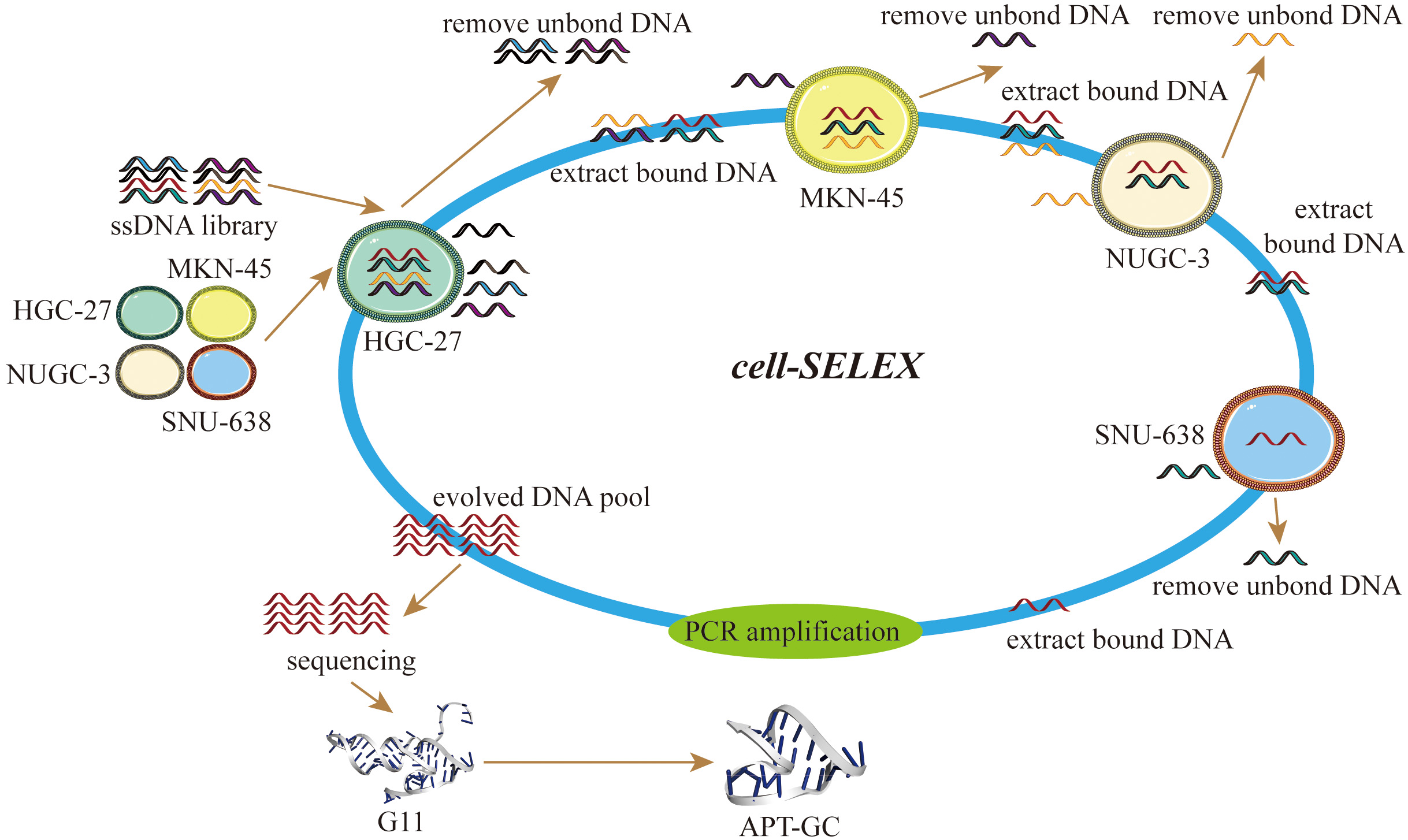

The study aims to investigate the potential of aptamers as diagnostic and targeted therapeutic tools for gastric cancer (GC) and other cancer types through the cell-systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (cell-SELEX) process. GC is associated with high global incidence rates and a substantial lack of effective targeted therapies. Aptamers have emerged as a promising innovation for both the diagnosis and targeted treatment of various cancers.

Cell-SELEX process was employed to screen for aptamers specific to GC cells, utilizing the GC cell lines HGC-27, MKN-45, SNU-638, and NUGC-3 as target cells. Aptamer affinity, specificity, and biological properties were evaluated through flow cytometry, and mass spectrometry was utilized to identify potential target proteins.

Aptamer-gastric cancer (APT-GC) is efficiently internalized by GC cell lines (HGC-27, MKN-45, SNU-638, NUGC-3) through receptor-mediated endocytosis at concentrations up to 300 nM, with intracellular stability for at least 2 hours and stability in serum for up to 6 hours. Furthermore, APT-GC is internalized by various cancer cell types, suggesting its potential for broad application in pan-cancer diagnosis and treatment.

APT-GC exhibits high affinity for GC cells and can also be internalized by diverse cancer cell types, positioning it as a versatile diagnostic and therapeutic agent for a wide range of cancers.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- aptamer

- gastric cancer

- target

Gastric cancer (GC) represents a significant global health challenge, ranking as the fourth most prevalent cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality [1, 2, 3]. In 2020, China reported approximately 480,000 new GC cases, making it the third most common cancer in the country and accounting for 44% of global cases. With a 5-year survival rate of merely 35.1%, GC remains the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in China, contributing to 50% of worldwide GC fatalities. Key factors such as Helicobacter pylori infection, activation of oncogenic pathways, and epigenetic alterations primarily drive its development and progression [4, 5, 6]. Advances in genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and single-cell sequencing have enabled the identification of numerous genes, proteins, metabolites, and other molecules associated with GC metastasis and invasion, which hold potential as biomarkers for the disease. However, the clinical utility of these markers in GC diagnosis and treatment remains limited [5, 7, 8, 9]. Currently, the main treatment strategy for GC involves a combination of surgical resection and chemotherapy. Among targeted therapies, Trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), was the first approved agent for this malignancy [10]. Despite this, the progress in GC treatment has remained stagnant for nearly a decade, underscoring the ongoing need for the development of novel pharmacological agents and drug delivery systems for targeted therapy in GC [11].

In recent years, small molecule nucleic acids have rapidly advanced as therapeutic agents and drug-targeting delivery carriers. Among these, aptamers have emerged as an innovative strategy for the diagnosis and targeted treatment of cancer and other diseases. Initially discovered by Tuerk and Gold in 1990 [12], aptamers are single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules selected from a specific oligonucleotide library via the systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) process [13]. These molecules are distinguished by their high specificity and strong affinity for target binding [14]. Compared to monoclonal antibodies, aptamers offer several advantages, including lower molecular weight, shorter production cycles, reduced costs, enhanced stability, ease of modification, and minimal immunogenicity. These attributes make them suitable for diverse applications, such as cell imaging, disease detection and diagnosis, targeted drug delivery, and therapeutic interventions [15, 16]. Since their discovery approximately three decades ago, aptamers have gained widespread recognition and application in medical fields related to disease diagnosis, therapy, and drug delivery. Currently, the only aptamer approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical use is Pegaptanib (Macugen) [17], indicated for age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Additionally, several other aptamers, including AS1411 [18] and E10030 [19], are undergoing clinical evaluation, reflecting the significant potential of aptamers in disease diagnosis and therapy, thereby justifying continued research efforts [20]. A comprehensive analysis of GC aptamers, as outlined in Table 1 (Ref. [21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45]), indicates that current aptamers lack the capability to comprehensively target all GC cell subtypes. Therefore, the development of aptamers capable of recognizing multiple GC cell types is anticipated to provide a novel diagnostic and therapeutic tool for GC.

| Name | Target site | Cell | First Author | Year of publication | Sequence | Ref |

| Apt-CP/Mn-PBA DSNB | CD63* | SGC-7901 | Mengying Fu | 2024 | - | [21] |

| EP16 | PD-L1* | unknown | Jian-Gang Sun | 2024 | - | [22] |

| HApt | HER2 | unknown | Wenjuan Ma | 2023 | - | [23] |

| Vimentin aptamer | Vimentin | GES-1 | Lingling Cheng | 2023 | TAGACCCAGCTGGTCCGGAAAATAAGATGTCACGGATCCTC | [24] |

| EpCAM and PTK7 aptamer | EpCAM/PTK7* | circulating tumor cell | Yifan Zuo | 2024 | - | [25] |

| PC+Au+MCH+RNA aptamer | CA72-4* | unknown | Saw-Lin Oo | 2021 | CGGGGGUGCGAAGGGGGGCAGAGGUUUGACGCGAGA | [26] |

| AS1411 | nucleolin | MKN-45 | Wen Chen | 2020 | GGTGGTGGTGGTTGTGGTGGTGGTGGAAAAA | [27] |

| AGS | Yajie Zhang | 2020 | [28] | |||

| SGC-7901 | Weiwei Zhang | 2023 | [29] | |||

| MKN-45 | Mahsa Ramezanpour | 2019 | [30] | |||

| MKN-45 | Puyan Daei | 2018 | [31] | |||

| MKN-45 | Sahar Taghavi | 2017 | [32] | |||

| aptamer-S4F | unknown | SGC-7901 | Chuan-Gang Liu | 2020 | - | [33] |

| MUC1 aptamer | gastric cancer exosome | unknown | Rongrong Huang | 2020 | TACTGCATGCACACCACTTCAACTA | [34] |

| SGC-7901 | 2019 | - | [35] | |||

| PDGC21-T | unknown | BGC-823 | Wanming Li | 2019 | - | [36] |

| Seq-3; Seq-6; Seq-19; Seq-54 | unknown | Gastric cancer serum | Yue Zheng | 2019 | - | [37] |

| CEA A01/A02; | CEA*; | AGS | Qing Pan | 2018 | CEA A01: GGGUCGUGUCGGAUCCAGGCACGACGCAUAGCCUUGGGAGCGAGGAAAGCUUCUAAGGUAACGAU; | [38] |

| A02: GGGUCGUGUCGGAUCCAACGGCAUGACCUAACCUGGAGGCGCAUCAAAGCUUCUAAGGUAACGAU; | ||||||

| CA50 A01/A02; | CA50*; | CA50 A01: GGGUCGUGUCGGAUCCGUGAGUUUUUCGCGGCGAAGACAAGGCUCGAAGCUUCUAAGGUAACGAU; | ||||

| A02: GGGUCGUGUCGGAUCCAGCUCGAAAGUGGGCUGGCGAUGUGUCCCGAAGCUUCUAAGGUAACGAU; | ||||||

| CA72-4 A01/A02 | CA72-4 | CA72-4 A01: GGGUCGUGUCGGAUCCUGCGAAGGGGGGCAGAGGUUUGACGCGAGAAAGCUUCUAAGGUAACGAU; | ||||

| A02: GGGUCGUGUCGGAUCCCCCAAAAAGGAUUGGGGCGUCUGCAUGACCAAGCUUCUAAGGUAACGAU | ||||||

| Ep1 | EpCAM | KATO III | Walhan Alshaer | 2018 | - | [39] |

| FMNS | unknown | SGC-7901 | Fei Ding | 2015 | GATCTCTCTCTGCCCTAAGTCCGCACCCGTGCTTCCCTGT | [40] |

| cy-apt 20 | unknown | AGS | Hong-Yong Cao | 2014 | CGACCCGGCACAAACCCAGAACCATATACACGATCATTAGTCTCCTGGGCCG | [41] |

| AGC03 | unknown | HGC-27 | Xiaojiao Zhang | 2014 | - | [42] |

| SYL3C | EpCAM | Kato III | Yanling Song | 2013 | CACTACAGAGGTTGCGTCTGTCCCACGTTGTCATGGGGGGTTGGCCTG-(PEG) 3-biotin | [43] |

| 2-2(t) | HER2 | N87 | Georg Mahlknecht | 2013 | - | [44] |

| EpDT3 | EpCAM | Kato III | Sarah Shigdar | 2011 | GCGACUGGUUACCCGGUCG | [45] |

Note: Apt-CP/Mn-PBA DSNBs, CD63 aptamer-labeled copper peroxide/manganese-containing Prussian blue analogues double-shelled nanoboxes; * CD63, cluster of differentiation 63; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; EpCAM/PTK7, a single epithelial cell adhesion molecule/protein tyrosine kinase 7; CA72-4, cancer antigen 72-4; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA50, cancer antigen 50.

To address this, four GC cell lines (HGC-27, MKN-45, SUN-638, NUGC-3) were selected as target cells for screening, resulting in the identification of an aptamer named Aptamer-gastric cancer (APT-GC). This aptamer demonstrates high affinity for cell surface receptors, efficient cellular internalization, and robust stability both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, APT-GC exhibits high affinity for various cancer cell types, positioning it as a promising candidate for drug delivery applications in GC.

The GC cell lines HGC-27 (CTCC-002-0006), MKN-45 (CTCC-ZHYC-0503), SUN-638 (CTCC-007-0403), and NUGC-3 (CTCC-007-0391) were obtained from Meisen Chinese Tissue Culture Collections (CTCC, Meisen Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China), while BxPC-3, MC-38, IHH4, PANC-1, HepG2, TPC-1, BAF3, HL-60, and NALM-6 were generously provided by Professor Jiangfeng Wu of China Three Gorges University. TC-1 and U14 were kindly gifted by Dr. Chuying Huang of Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture Central Hospital, and SUP-B15 was donated by Professor Zhenglan Huang of Chongqing Medical University. All cell lines were validated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma. Cells were cultured according to the respective manuals, using the specified culture medium, serum, and 1% streptomycin/penicillin (P/S), and maintained in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2.

The random ssDNA library, along with the corresponding upstream and downstream primers, was synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Lot No: 1937702901, Shanghai, China) Co., Ltd. The library consists of 18 constant primer binding sites at both ends and 45 random nucleotides in the center, represented as ATCCAGAGTGACGCAGCA(45N)TGGACACGGTGGCTTAGT. The forward primer sequence is 5′-ATCCAGAGTGACGCAGCA-3′, and the reverse primer sequence is 5′-biotin-ACTAAGCCACCGTGTCCA-3′. Following the synthesis report, DEPC-treated water was added, and the mixture was vortexed to dissolve the library and primers into a 100 µM storage solution, which was stored at –20 °C.

Cell-SELEX was performed following a previously reported protocol [46]. The DNA library was denatured at 95 °C for 5 minutes and then annealed in an ice bath for 10 minutes. HGC-27, NUGC-3, SNU-638, and MKN-45 cells were used as target cells for screening. Prior to selection, the cells were washed with a buffer containing 4.5 g/L glucose and 5 mM MgCl2 in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS). The DNA library was then incubated with the cells in a binding buffer containing 0.1 g/L tRNA and 1 g/L bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37 °C for 30–60 minutes. With each screening round, the incubation time for positive cells was progressively shortened, and the number of positive cells decreased. Following cell lysis, the supernatant was used as a PCR template. The next-generation library was generated through PCR amplification, product recovery, double-strand alkali cleavage, and single-strand desalination. The screening process was repeated iteratively and monitored using real-time quantitative PCR. After 12 rounds of selection, the final single-stranded DNA library was subjected to high-throughput sequencing analysis.

The secondary structure of the sequence was modeled using the bioinformatics tool Mfold (http://www.unafold.org/DNA_form.php), and its tertiary structure was predicted using RNA Composer (https://rnacomposer.cs.put.poznan.pl/). Truncation of the non-coding region was performed without altering the aptamer’s stem-loop structure to yield the shortest optimized sequence.

When cells reached 60%–80% confluence, they were washed with PBS. FAM-labeled aptamers with different sequences were then added, and cells were incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour. After incubation, the binding of aptamers to cells was observed directly using a fluorescence microscope (SOPTOP IRX60, Sunny Optical Technology, Zhejiang, China), or cells were washed three times with PBS, digested with trypsin, and the digestion reaction stopped with serum-containing culture medium. Cells were subsequently collected into a 1.5 mL EP tube, centrifuged at 150 g, washed again with PBS, and resuspended in PBS for flow cytometry analysis.

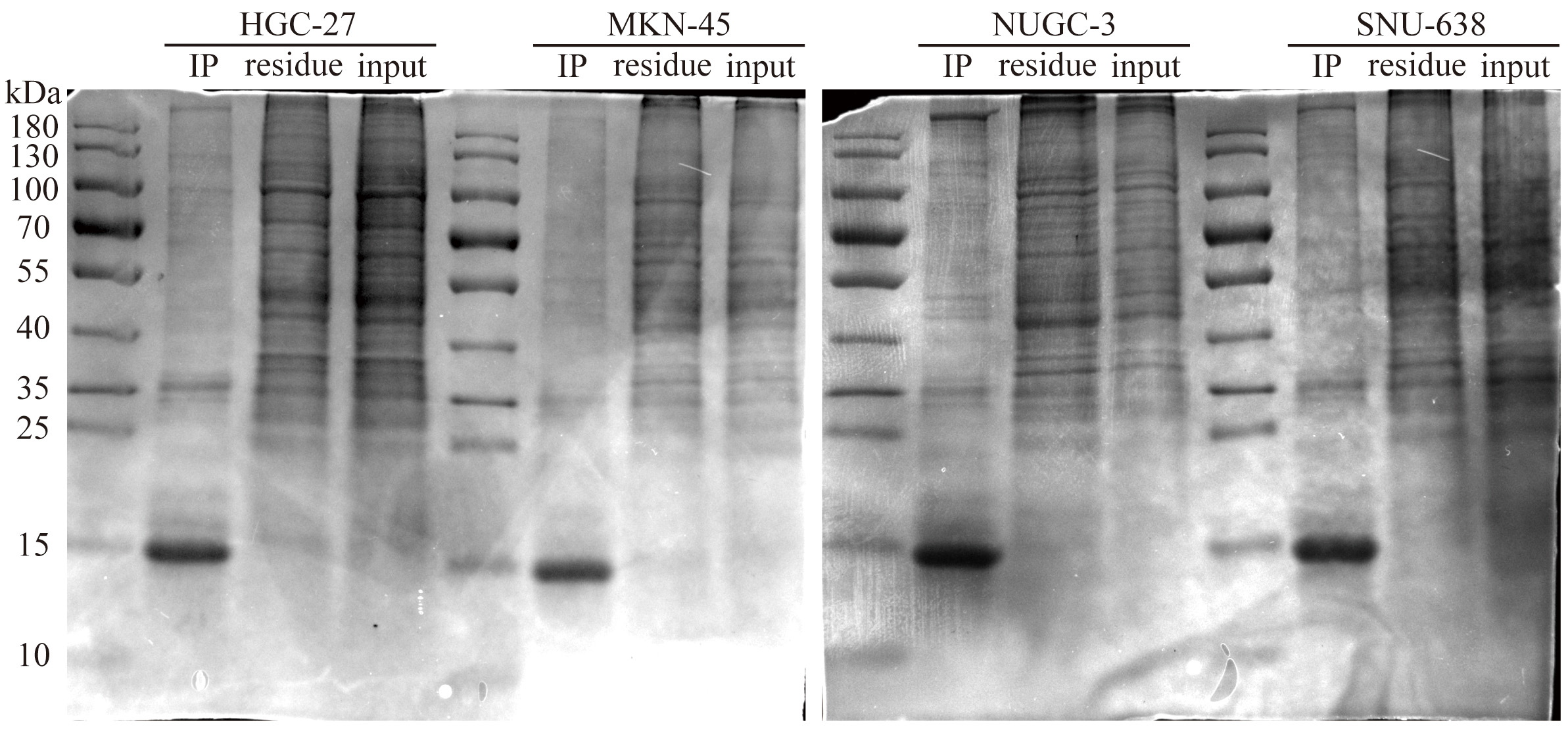

Lysates were extracted from four GC cell lines (HGC-27, NUGC-3, SNU-638, MKN-45) to obtain protein solutions. These protein solutions were incubated overnight at low temperatures with the aptamer APT-GC to form immune complexes, followed by incubation with magnetic beads. After washing to remove unbound substances, the immune complexes were eluted using electrophoresis loading buffer, and the protein bands were analyzed using PAGE. Mass spectrometry analysis was subsequently performed to identify potential target proteins.

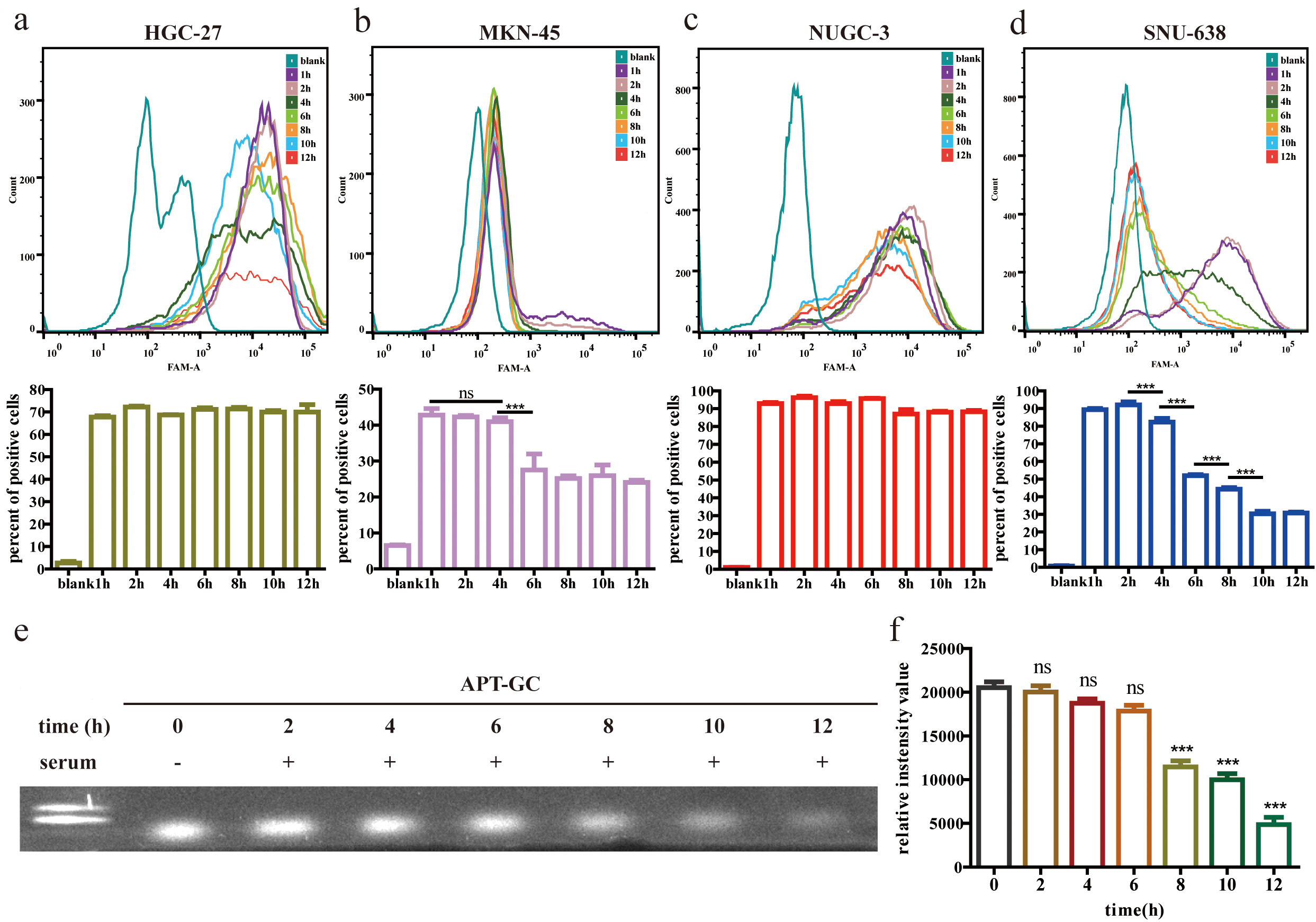

For the assessment of cellular stability, APT-GC was incubated with HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638 cells for 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours. After incubation, cells were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the number of positive cells and the fluorescence intensity. For serum stability testing, normal peripheral blood serum (from 8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice) was mixed with APT-GC at a concentration of 10 µM in equal volumes and incubated at 37 °C. After incubation at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours, the samples were subjected to 10% native-PAGE at 100 V for 2 hours. The gel images were then examined to assess the position and diffusion of the bands.

Data are presented as mean

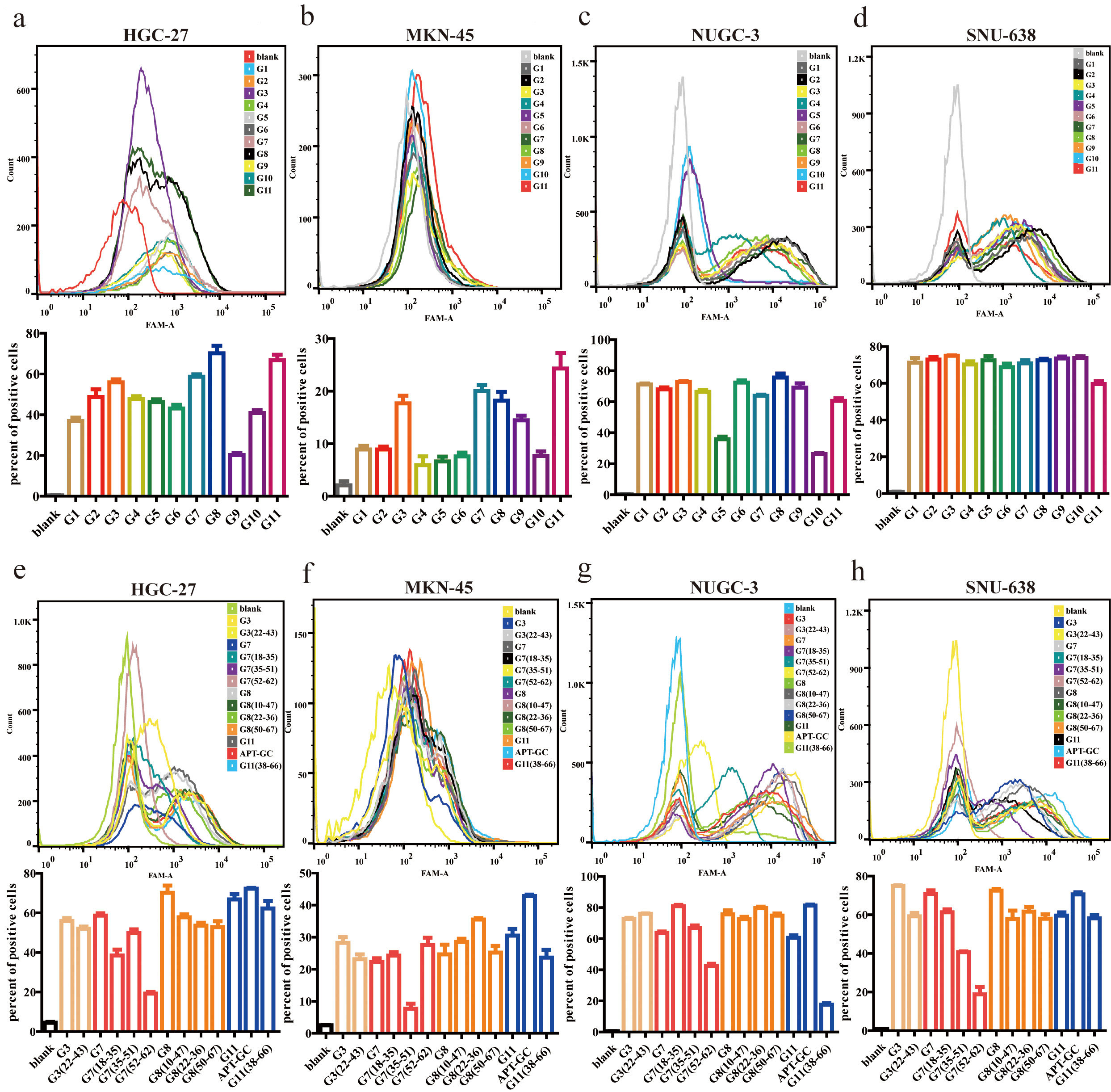

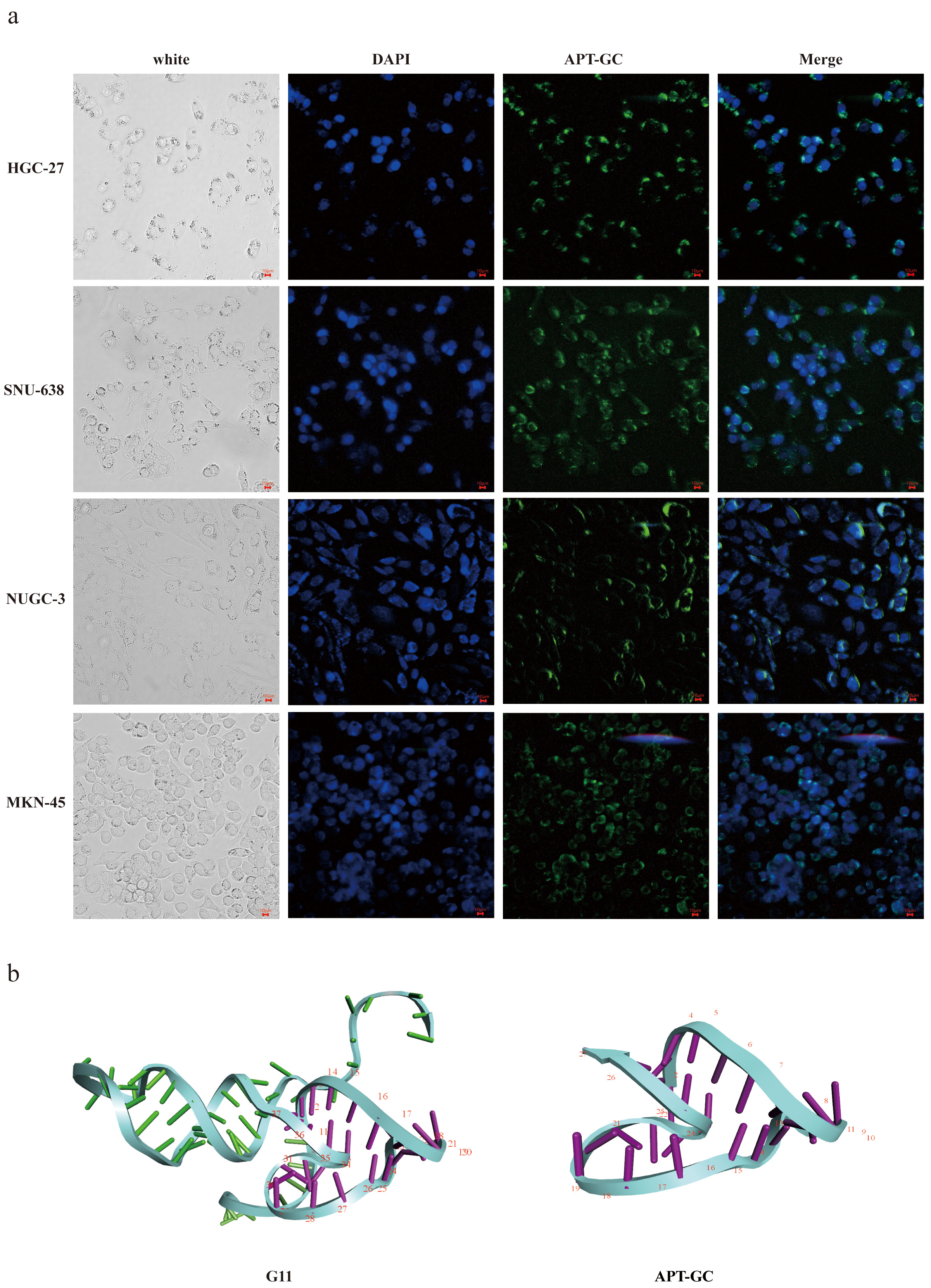

Aptamers with higher affinity for cells demonstrate stronger fluorescence intensity at equivalent concentrations or achieve peak fluorescence intensity at lower concentrations. After 12 rounds of selection, high-throughput sequencing was performed, and through the analysis of sequencing read homology and abundance, 11 sequences were identified. These sequences were incubated with HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638 cells at 300 nM for 1 hour at 37 °C, and their binding affinity was measured using flow cytometry. The results revealed that G3, G7, G8, and G11 exhibited high affinity for all four cell lines, with the proportion of positive cells in three of the four cell lines exceeding 50%, as shown in Fig. 1a–d. Following secondary and tertiary structure analysis via bioinformatics tools, G3, G7, G8, and G11 were truncated and optimized. Flow cytometry results indicated that the truncated sequence of G11, designated as APT-GC, displayed the highest affinity, as shown in Fig. 1e–h. Fluorescence microscopy images of APT-GC in Fig. 2a, indicate its internalization in four GC cell lines. The tertiary structures of G11 and APT-GC are shown in Fig. 2b, highlighting that the tertiary structure remained unaltered after truncation.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Binding affinity of G1-G11 and truncated sequences to HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638. (a–d) Flow cytometry was used to assess the affinity of G1-G11 to HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638, respectively. (e–h) Flow cytometry was used to assess the affinity of the truncated sequences of G3, G7, G8, and G11 to HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638, respectively. Data are presented as mean

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Fluorescence results and tertiary structure of APT-GC with HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3 and SNU-638. (a) Fluorescence intensity of APT-GC with HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638 was measured respectively using microscopic fluorescence imaging technology. (b) Tertiary structures of G11 and APT-GC. Scale bar = 10 μm.

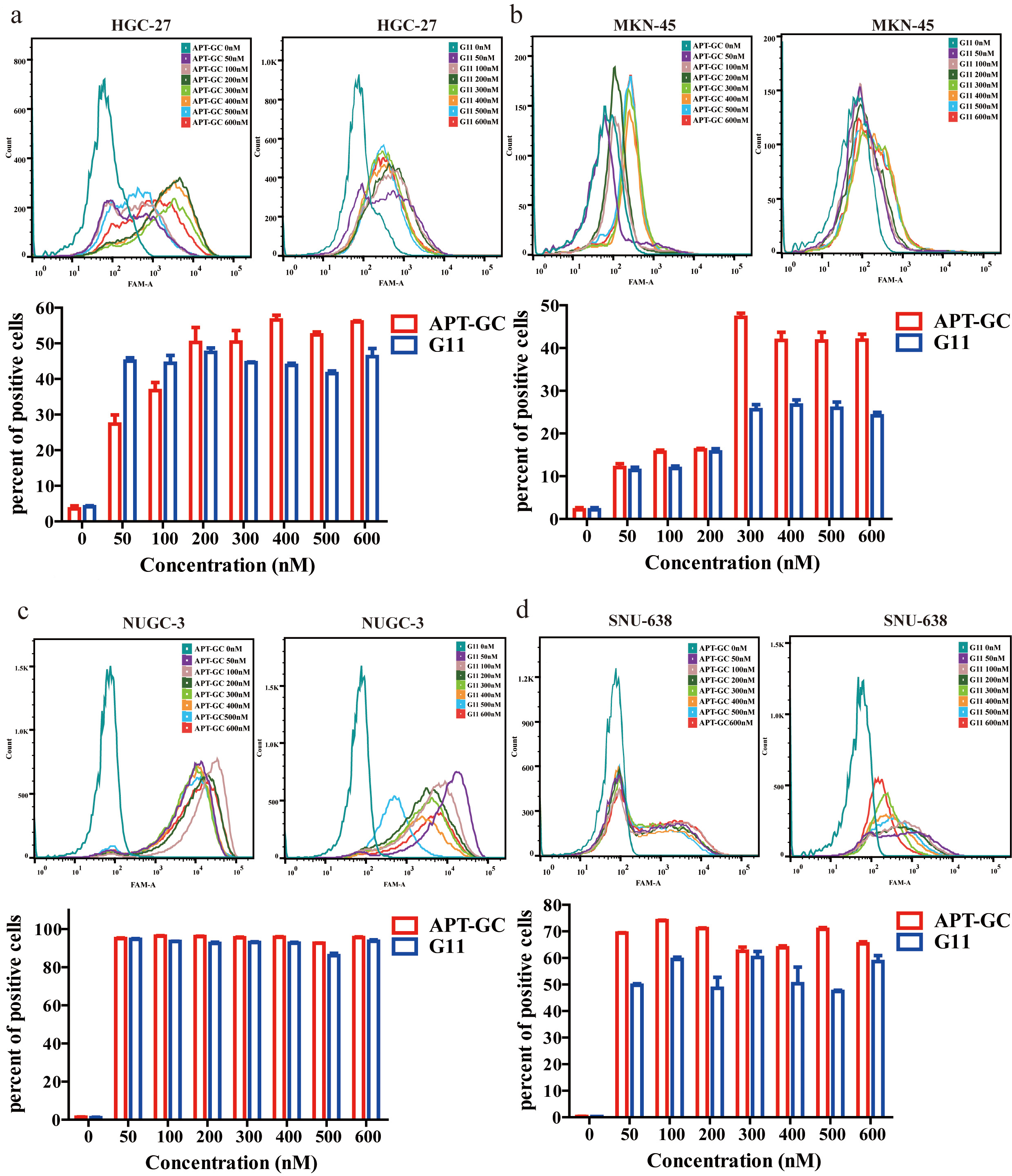

Flow cytometry was used to evaluate fluorescence intensity in HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638 after exposure to APT-GC at concentrations ranging from 0 nM to 600 nM, in 50 nM increments. The maximum fluorescence intensity was observed at 200 nM for HGC-27, 300 nM for MKN-45, 50 nM for NUGC-3, and 50 nM for SNU-638. These results suggest that APT-GC achieves maximum binding saturation at concentrations up to 300 nM. The data are shown in Fig. 3a–d.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Concentration gradient detection of APT-GC in GC cells. (a–d) APT-GC at concentrations of 0, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, and 600 nM was incubated with HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638 at 37 °C for 1 hour. Flow cytometry was then used to measure fluorescence intensity. Data are presented as mean

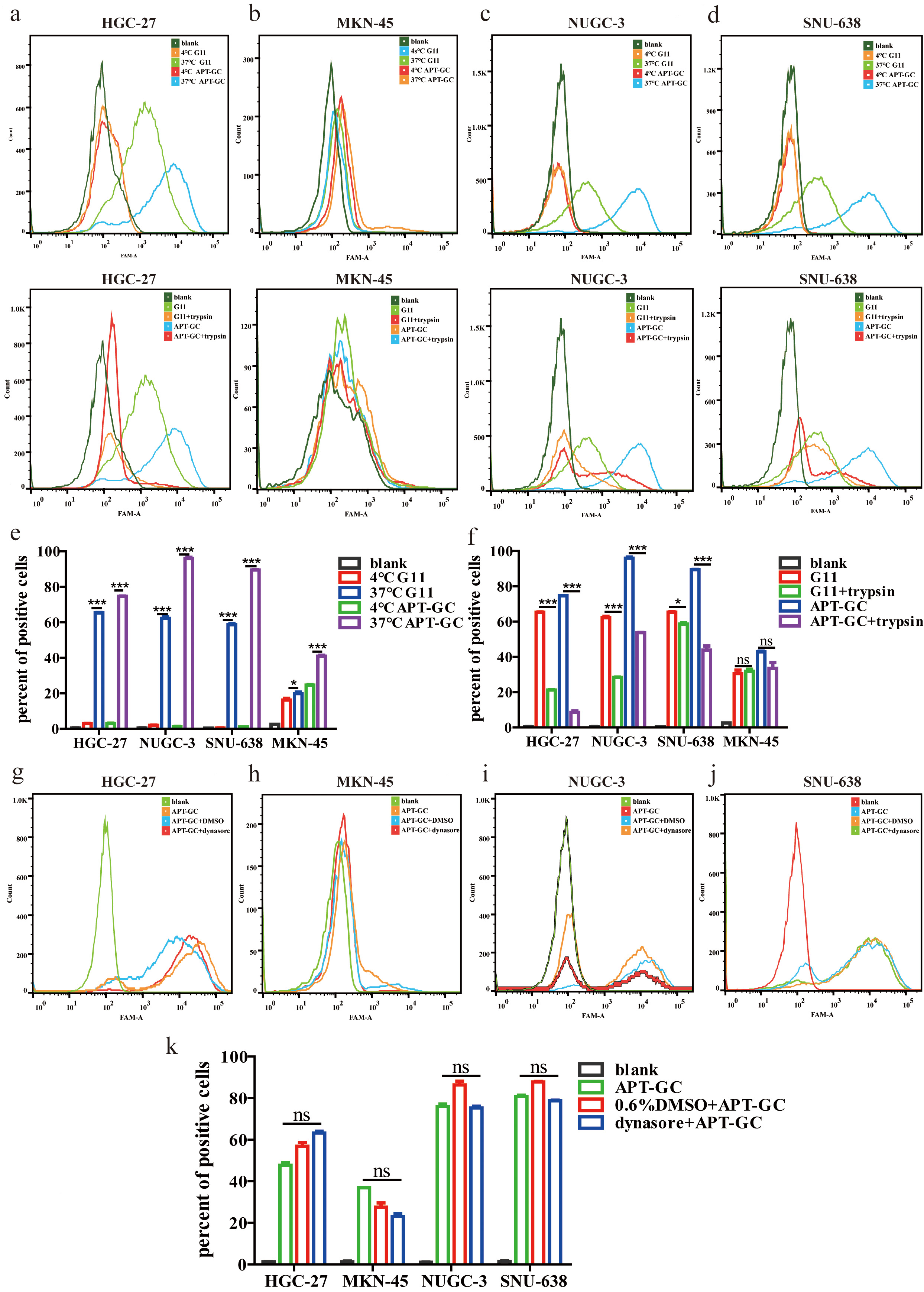

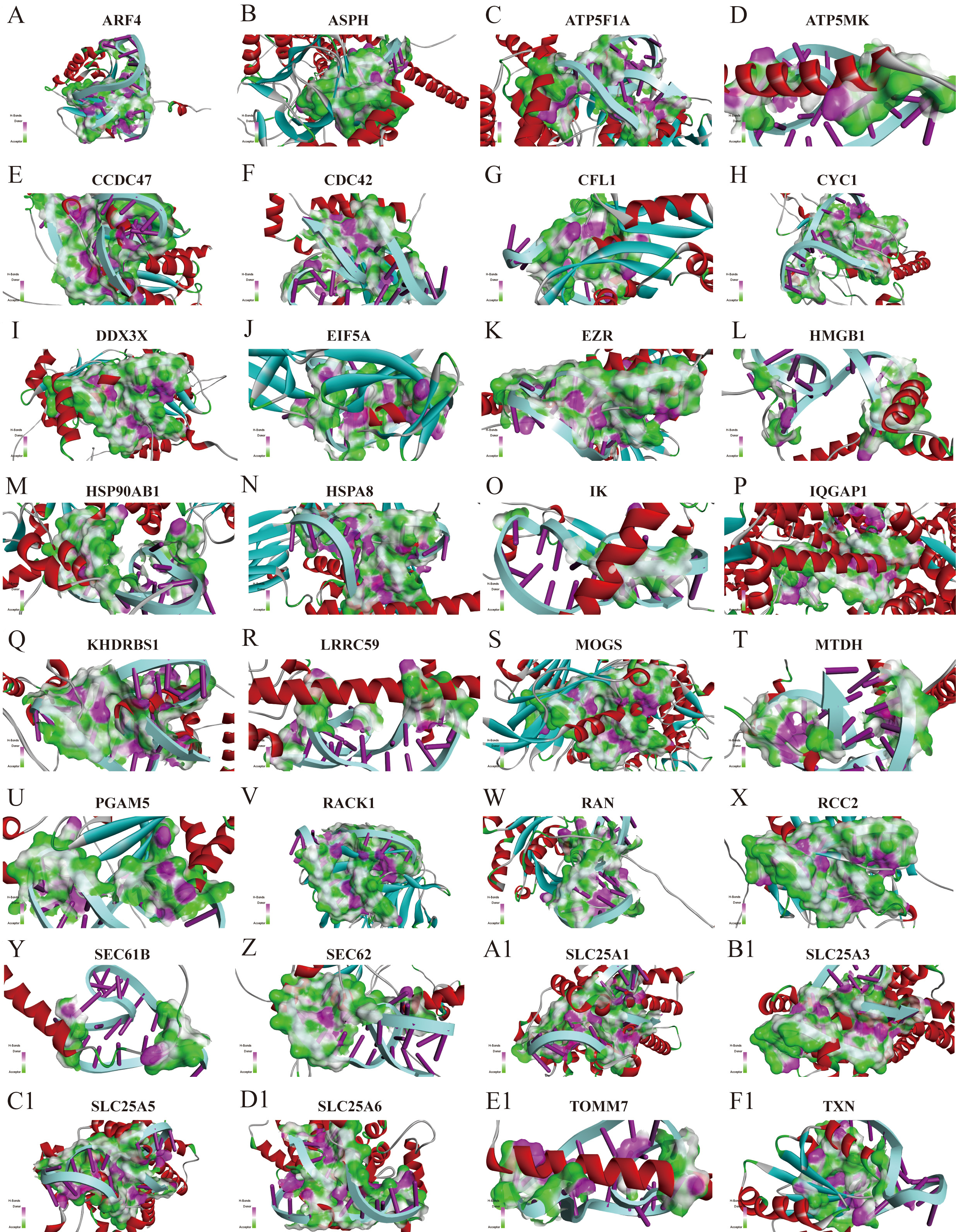

Aptamers enter cells primarily via receptor-mediated endocytosis and micropinocytosis [47]. Our observations indicate that APT-GC internalizes into four GC cell lines, likely through a common receptor or macropinocytosis. To investigate this further, the impact of temperature on the internalization process was assessed. APT-GC was incubated with cells at both 37 °C and 4 °C, followed by flow cytometry analysis. The results, presented in Fig. 4a–d, demonstrate that low temperatures inhibit APT-GC internalization, suggesting its uptake occurs via receptor-mediated endocytosis/macropinocytosis or a combination of both. Additionally, pre-treatment with trypsin at 37 °C for 5 minutes, prior to APT-GC incubation and subsequent flow cytometry analysis, resulted in a decreased positivity rate for HGC-27, NUGC-3, and SNU-638 cells, while MKN-45 showed no significant change. These findings imply that receptor-mediated endocytosis plays a role in APT-GC internalization in HGC-27, NUGC-3, and SNU-638 cells, as shown in Fig. 4a–f. Treatment with the dynamin inhibitor dynasore (10 µM, 1-hour pre-treatment) to block macropinocytosis had no effect on APT-GC internalization, indicating that receptor-mediated endocytosis is the dominant pathway for APT-GC uptake, as depicted in Fig. 4g–k. Co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP) assays with the four GC cell lines revealed membrane protein interactions, with results presented in Fig. 5. Mass spectrometry analysis identified key membrane proteins, and structural docking simulations of APT-GC with the most abundant membrane protein are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Temperature, trypsin, and dynasore effects on APT-GC internalization in GC cells. (a–f) APT-GC was incubated with HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638 at 4 °C and 37 °C for 1 hour, followed by trypsin treatment. After incubation, flow cytometry detected fluorescence intensity. (g–k) APT-GC pre-treatment with dynasore, followed by incubation with the four GC cell lines, and flow cytometry analysis. Data are presented as mean

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Co-immunoprecipitation gel electrophoresis of APT-GC in HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Structural docking simulation of APT-GC with the most abundant membrane protein. (A-F1) Simulation diagram of the structural docking of APT-GC with membrane proteins ARF4, ASPH, ATP5F1A, ATP5MK, CCDC47, CDC42, CFL1, CYC1, DDX3X, EIF5A, EZR, HMGB1, HSP90AB1, HSPA8, IK, IQGAP1, KHDRBS1, LRRC59, MOGS, MTDH, PGAM5, RACK1, RAN, RCC2, SEC61B, SEC62, SLC25A1, SLC25A3, SLC25A5, SLC25A6, TOMM7, TXN. ARF4, ADP-ribosylation factor 4; ASPH, Aspartate beta-hydroxylase; ATP5F1A, ATP synthase F1 subunit alpha; ATP5MK, ATP synthase subunit epsilon, mitochondrial; CCDC47, Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 47; CDC42, Cell division cycle 42; CFL1, Cofilin-1; CYC1, Cytochrome c-1; DDX3X, DEAD/H-box helicase 3 X-linked; EIF5A, Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A; EZR, Ezrin; HMGB1, High mobility group box 1; HSP90AB1, Heat shock protein HSP 90-beta; HSPA8, Heat shock 70kDa protein 8; IK, Inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells, kinase; IQGAP1, IQ motif-containing GTPase activating protein 1; KHDRBS1, KH domain-containing, RNA-binding, signal transduction-associated protein 1; LRRC59, Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 59; MOGS, Mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase; MTDH, Metadherin; PGAM5, Phosphoglycerate mutase 5; RACK1, Receptor for activated C kinase 1; RAN, member RAS oncogene family; RCC2, Regulator of chromosome condensation 2; SEC61B, Sec61 beta subunit; SEC62, Sec62 homolog (S. cerevisiae); SLC25A1, Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier; adenine nucleotide translocator), member 1; SLC25A3, Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier; phosphate carrier), member 3; SLC25A5, Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier; ADP/ATP translocase), member 5; SLC25A6, Solute carrier family 25 (mitochondrial carrier; ADP/ATP translocase), member 6; TOMM7, Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 7 homolog (yeast); TXN, Thioredoxin.

Aptamers used for diagnostic and therapeutic applications must maintain adequate stability after being introduced into the bloodstream and cells to ensure reliable diagnostic performance. Cellular stability assessments, shown in Fig. 7a–d, demonstrate that APT-GC remains stable for over 12 hours in HGC-27 and NUGC-3 cells, 4 hours in MKN-45 cells, and 2 hours in SNU-638 cells. Serum stability tests, presented in Fig. 7e,f, indicate that APT-GC retains stability for up to 6 hours, as confirmed by native-PAGE gel imaging and subsequent statistical analysis.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Stability analysis of APT-GC in GC cells and serum. (a–d) APT-GC was incubated with HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638 cell lines for 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours. Flow cytometry was used to measure fluorescence intensity at each time point (n = 3). (e) Electrophoresis lanes from left to right: 100 bp DNA ladder, APT-GC incubated with serum for 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours. (f) Statistical analysis of serum stability. Statistical comparisons were performed separately between each time point (2 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, 10 h, 12 h) and the baseline (0 h). ns p

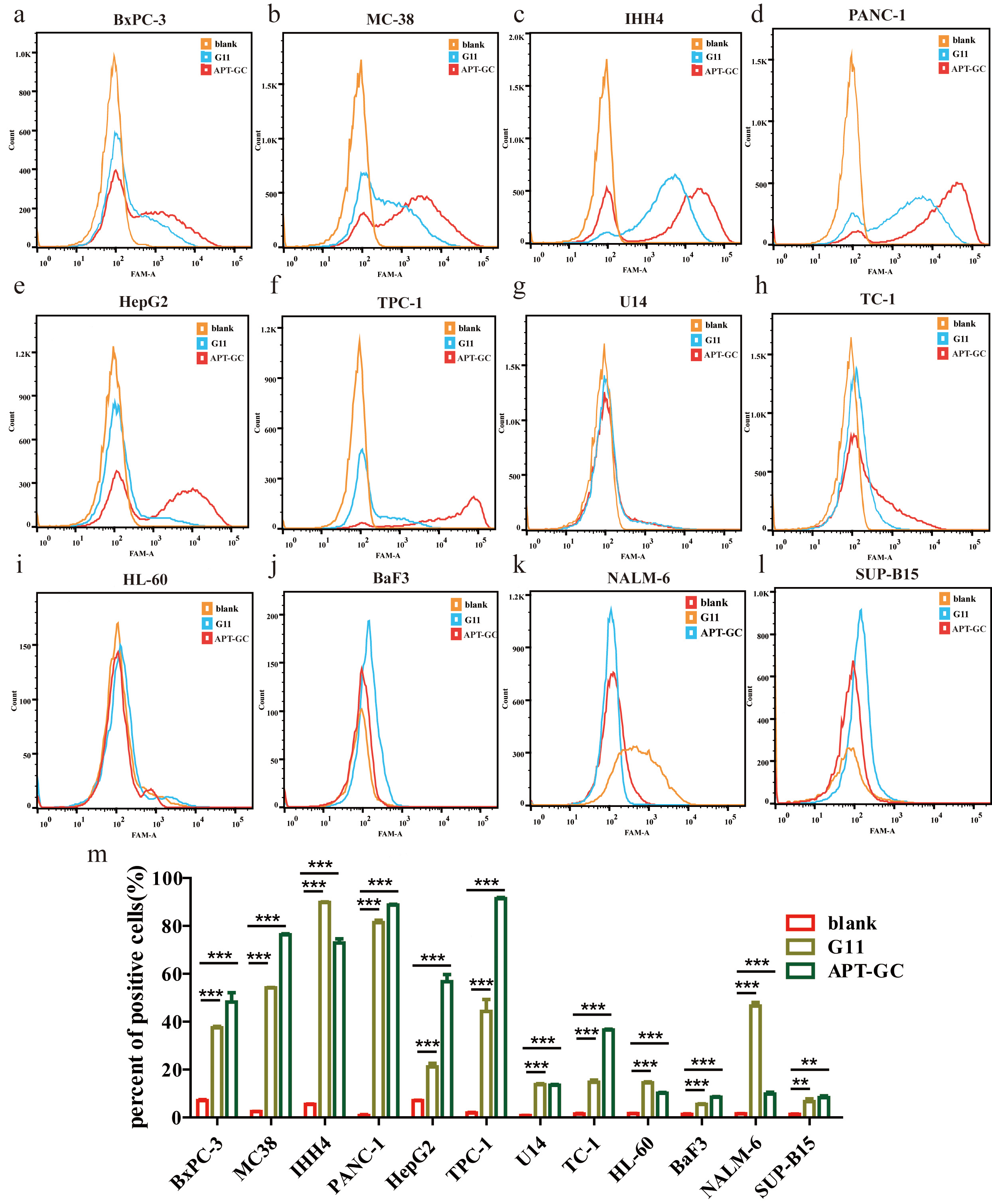

In addition to evaluating the cellular uptake and characteristics of APT-GC in GC cell lines, its potential for internalization was explored across a broader range of tumor cell lines. APT-GC was incubated with BxPC-3, MC38, IHH-4, PANC-1, HepG2, TPC-1, U14, TC-1, HL-60, BaF3, NALM-6, SUP-B15 at a final concentration of 300 nM for 1 hour at 37 °C. Flow cytometry analysis, as shown in Fig. 8a–m, revealed that APT-GC was internalized by all tested tumor cell lines, demonstrating its pan-cancer activity and suggesting its potential as an auxiliary diagnostic tool for various cancers.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Internalization of APT-GC in various cancer cell lines. (a–l) APT-GC was incubated with BxPC-3, MC38, IHH-4, TPC-1, PANC-1, HepG2, U14, TC-1, HL-60, BaF3, NALM-6, SUP-B15 for 1 hour, and fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry for each cell line. (m) Statistical analysis comparing fluorescence intensity between the APT-GC treated and control groups across various cancer cell lines. **p

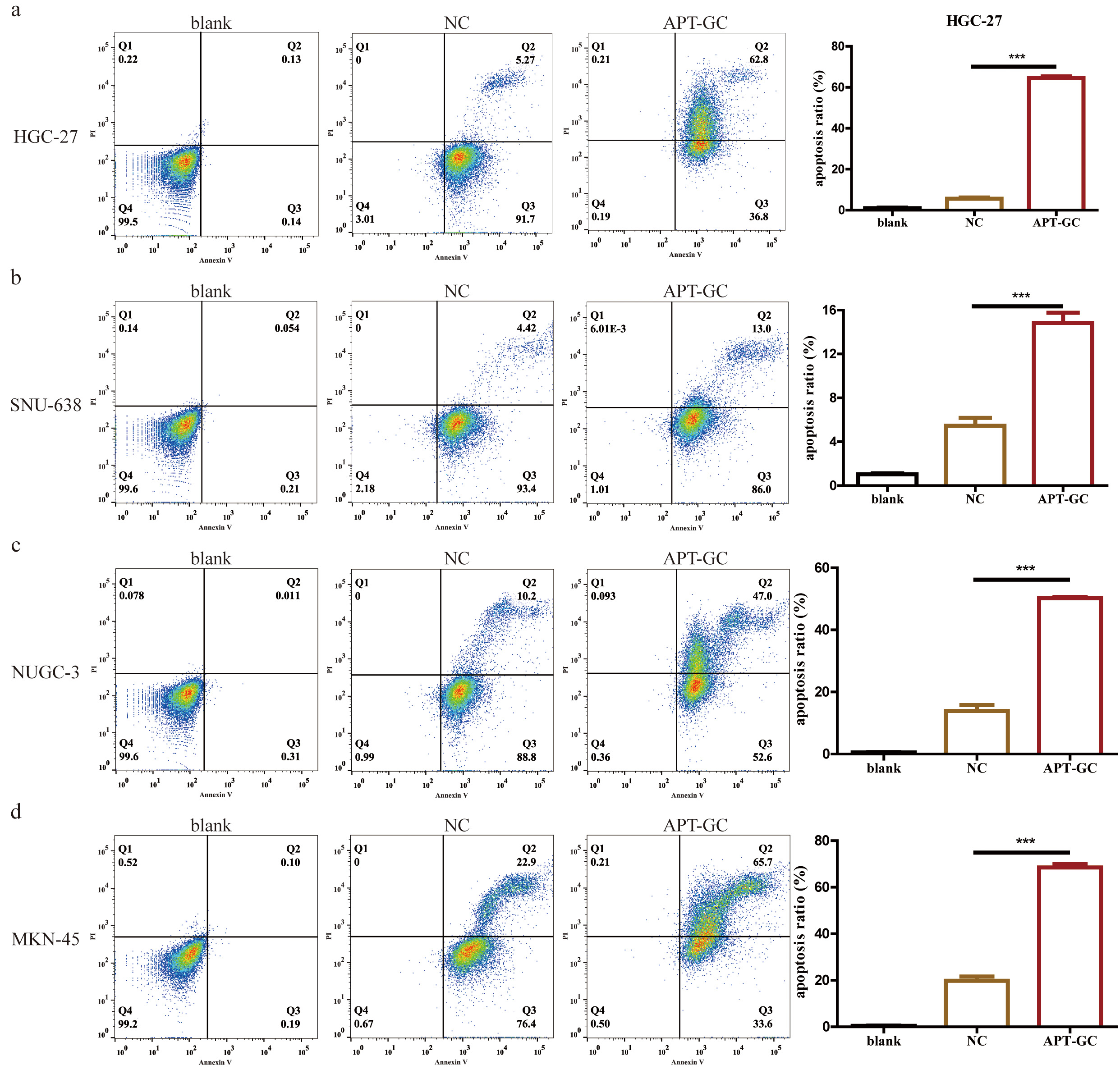

APT-GC was incubated with HGC-27, SNU-638, NUCG-3, and MKN-45 gastric cancer cells for 24 hours, and cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry, as shown in Fig. 9a–d. The results showed that the proportion of cells in the APT-GC treatment group was significantly higher than that in the negative control group, markedly increasing the apoptosis rate of gastric cancer cells.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9. The effect of APT-GC on apoptosis in different gastric cancer cell lines. (a–d) After co-incubation of APT-GC with HGC-27, SNU-638, NUGC-3, and MKN-45 for 24 hours, the apoptosis rate was detected by flow cytometry. ***p

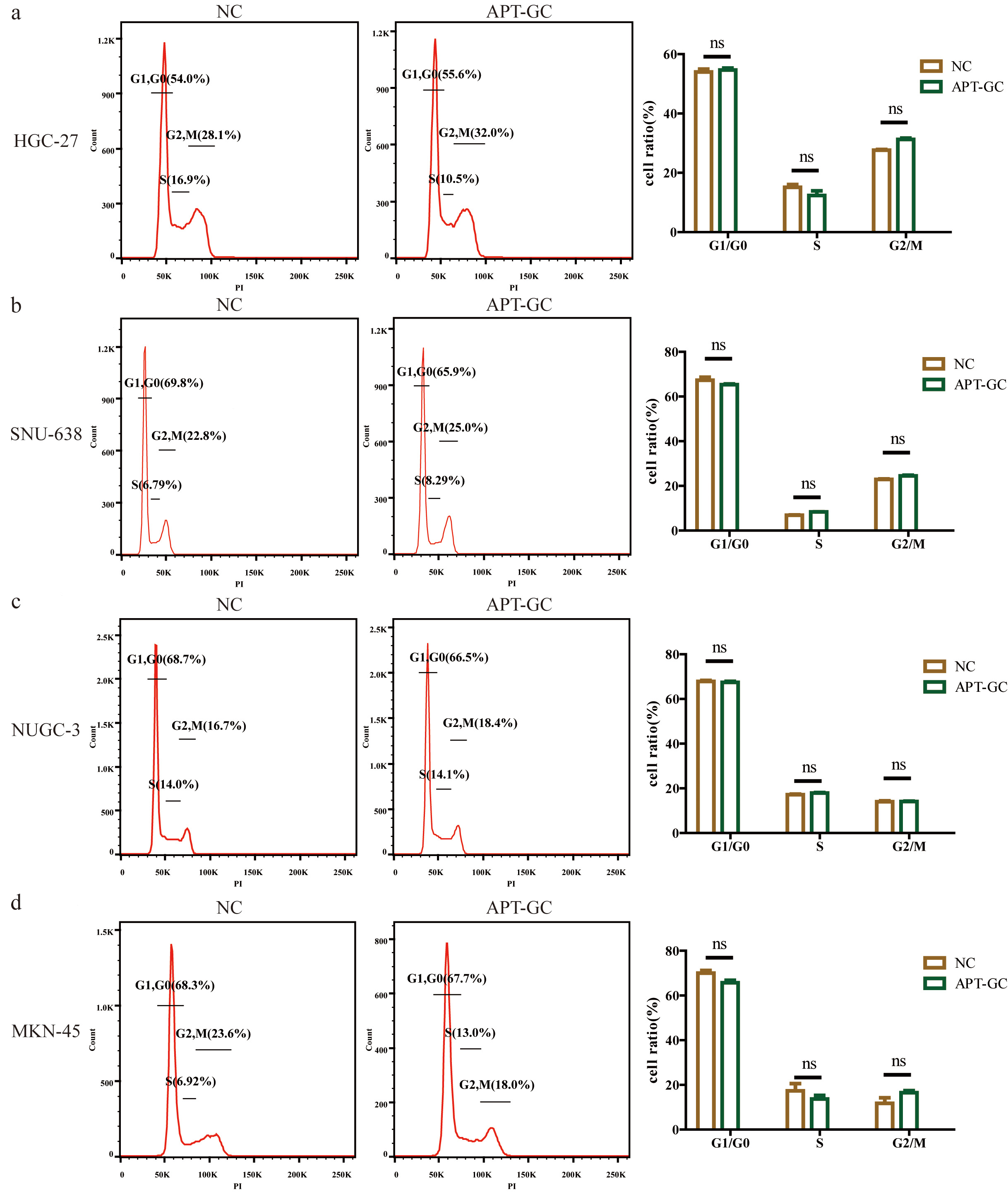

Flow cytometry was used to analyze the cell cycle distribution of HGC-27, SNU-638, NUCG-3, and MKN-45 cell lines under normal culture conditions (NC) and under APT-GC treatment conditions, as shown in Fig. 10a–d. The results indicated that compared to the NC group, there was no significant difference in the cell cycle distribution of the four gastric cancer cell lines after APT-GC treatment.

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10. The effect of APT-GC on the cell cycle of different gastric cancer cell lines. (a–d) Flow cytometry was used to analyze the cell cycle distribution of the HGC-27, SNU-638, NUGC-3, and MKN-45 cell lines under normal culture conditions (NC) and after treatment with APT-GC for 24 hours. ns p

Nucleic acid aptamers, a promising targeted therapeutic approach, offer numerous advantages, prompting efforts to identify specific aptamers for gastric cancer. Using high-throughput screening, Sun et al. [22] identified EP16, a small molecule inhibitor that effectively suppresses exosomal PD-L1 expression and enhances PD-1 targeted therapy efficacy. By combining surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) with aptamers, Cheng et al. [24] developed a novel sensor capable of detecting vimentin alterations during the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer, with a detection threshold as low as 4.92 pg/mL. In this study, a straightforward yet highly efficient, reproducible, and widely applicable live cell-SELEX screening method was developed using HGC-27, MKN-45, SNU-638, and NUGC-3 gastric cancer cells as target screening cells. This approach helps to identify aptamers capable of recognizing different subtypes of gastric cancer cells. After 12 rounds of screening and sequence truncation optimization, APT-GC, a DNA aptamer with the highest affinity, was identified, showing over 50% binding affinity in HGC-27, SNU-638, and NUGC-3 cells, but a lower affinity in MKN-45 cells. Despite APT-GC’s strong affinity, its binding efficiency can be further optimized by refining the live cell screening process. Enhancing the design of the DNA library, screening protocols, and experimental settings can improve efficiency. For example, the configuration of fixed regions in the DNA library plays a pivotal role. Short fixed regions can lead to nucleotide bias and hinder tertiary structure formation, while excessively long regions may limit the applicability of the aptamers post-screening [48]. Conventional SELEX methods typically require over 15 rounds to identify high-affinity, high-specificity sequences. However, the most enriched sequences are not always the most effective, and low-occurrence sequences might be overlooked, leading to aptamers with either low binding affinity or high affinity but low specificity [49]. This is largely due to the structural flexibility of DNA or RNA, which reduces screening efficiency, as well as the loss of specific sequences [50], biases during the PCR process [51], and the parasitic amplification of non-specific sequences [52]. The entire screening process is influenced by various factors, including library size, buffer composition, ionic strength, pH, binding temperature, time, and the target’s characteristics such as charge, hydrophilicity, and whether binding sites are exposed. Additionally, the cell condition and target protein expression level are critical. Factors such as natural aging, environmental stress, genetic mutations, and suboptimal culture conditions can negatively affect cell conditions and, consequently, screening efficiency [49]. Expression levels of target proteins can vary significantly among different cell types, posing a challenge to the universal applicability of nucleic acid aptamers obtained through live cell screening in patient samples with the same disease. This limitation primarily stems from cellular heterogeneity [53] ar ring structure, protecting it from nuclease degradation and enhancing both thermal stability and binding affinity. Additionally, continuous cell passaging may reduce the expression levels of target proteins, leading to decreased specificity of aptamers over time [49].

In this study, the unmodified APT-GC demonstrated a stability duration exceeding 12 hours in HGC-27 and NUGC-3 cells, while stability was reduced to 4 hours in MKN-45 cells and 2 hours in SNU-638 cells. In serum, the stability was limited to 6 hours, highlighting a marked disparity. Such a short half-life may constrain its therapeutic efficacy in vivo, indicating the need for chemical modifications to enhance stability.

Current strategies for improving aptamer stability involve modifications to the sugar ring, phosphodiester backbone, nucleotide bases, and the 3′ and 5′ ends. Modifications at the 2′ position of the sugar ring include 2′-NH2, 2′-F, 2′-O-CH3, and locked nucleic acid (LNA). Among these, the 2′-F modification reduces aptamer backbone flexibility, thereby improving serum stability compared to the 2′-NH2 modification [49]. LNA modification stabilizes the sugar ring structure, protecting it from nuclease degradation and enhancing both thermal stability and binding affinity [54]. Phosphodiester backbone modifications, such as replacing the phosphodiester bond with a phosphorothioate (PS) bond, enhance plasma protein binding and reduce metabolic clearance [49]. Additionally, the 5′ end can be modified by adding polyethylene glycol (PEG) or cholesterol to prolong circulation time. Since exonuclease activity is significantly higher at the 3′ end, capping with an inverted deoxythymidine nucleotide (inverted dT) is commonly employed to improve aptamer stability [49].

During the experiment, low temperatures suppressed the cellular uptake of APT-GC, while the use of the macropinocytosis inhibitor Dynasore did not affect uptake efficiency. These findings suggest that APT-GC primarily enters cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis. This endocytic pathway can be categorized into clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) and caveolae-mediated endocytosis (CvME). In CME, substances bound to the cell surface are internalized via clathrin-coated vesicles. This process begins with the binding of nucleic acid aptamers to receptor regions, triggering the formation of clathrin-coated pits. Subsequently, membrane bending and invagination occur, followed by dynamin-catalyzed membrane fission, resulting in the release and fusion of clathrin-coated vesicles [55]. Similar to CME, CvME is initiated by the binding of ligands to cargo receptors, leading to dynamin-mediated fission of plasma membrane invaginations, which results in the formation of cytoplasmic caveolar vesicles. Regrettably, our study identified only potential APT-GC targets via mass spectrometry, and the exact membrane proteins remain unknown. To verify this, we plan to conduct the following in subsequent research: On the one hand, lysosomal pathway verification: LysoTracker will be used to label lysosomes in live cells. Confocal microscopy and live-cell imaging will then be used to colocalize them with fluorescently labeled APT-GC, checking whether APT-GC enters cells through phagocytosis. On the other hand, receptor-mediated verification: Cell membrane proteins with binding activity will be extracted and incubated with APT-GC for coprecipitation. An endocytosis-defective aptamer will be used as a negative control. Precipitated proteins will be analyzed via mass spectrometry. The target protein will be knocked down using siRNA to observe its effect on the fluorescence ratio.

Nucleic acid aptamers offer significant advantages in targeted cancer therapy, and one promising direction for future research involves the development and optimization of multi-targeted drug delivery systems. Aptamers can be conjugated with chemotherapeutic drugs to form aptamer-drug conjugates (AptDCs), allowing for precise and targeted drug delivery. For example, an aptamer-drug conjugate (HApt-tFNA@Dxd), which combines an anti-HER2 aptamer (HApt), tetrahedral framework nucleic acid (tFNA), and deruxtecan (Dxd), has shown superior structural stability, enhanced targeting capability, and increased tumor tissue accumulation in gastric cancer, compared to free Dxd and tFNA@Dxd [23]. Additionally, nucleic acid aptamers can be integrated with various nanomaterials, such as lipid nanoparticles, exosomes, metal nanoparticles, or polymer nanoparticles, to form aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials (AFNs). For instance, Zuo et al. [56] designed a dual-labeled fluorescent immunomagnetic nanoprobe (BP–Fe3O4–AuNR/Apt) by loading magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles and gold nanorods (AuNRs) onto black phosphorus (BP) nanosheets. These were conjugated with Cy3-labeled epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) and Texas Red-labeled PTK7 aptamers, enabling rapid and high-precision identification of gastric cancer cells [56]. Similarly, Fu et al. [21] utilized CD63 copper peroxide/manganese-containing Prussian blue analogues double-shelled nanoboxes (CP/Mn-PBA DSNBs) in combination with cDNA-labeled magnetic beads (cDNA-MB) to detect exosomes derived from gastric cancer cells (SGC-7901) and differentiate serum samples from patients with gastric cancer and healthy individuals.

The ability of APT-GC to be internalized by various cancer cell types indicates its pan-cancer potential. However, this also highlights a limitation regarding its specificity. Several factors may account for this issue. Firstly, the absence of the negative screening process may have compromised APT-GC’s ability to differentiate between cancerous and normal cells. Secondly, the live cell screening technique employed is an in vitro method that does not accurately replicate the complex physiological environment within the human body. Despite the promising role of nucleic acid aptamers in targeted cancer therapy, challenges such as off-target effects, immunogenicity, and potential toxic side effects persist. Off-target effects occur when non-target DNA sequences are inadvertently cleaved or modified during site-specific editing, potentially resulting in gene mutations or functional alterations that compromise research outcomes or therapeutic efficacy. These unintended modifications may also pose safety risks. To minimize non-specific binding and enhance the therapeutic index, future research should focus on several strategic approaches. Firstly, the dosage of nucleic acid aptamers should be meticulously controlled to prevent off-target activity. Secondly, the development of targeted delivery systems is essential to reduce non-specific distribution. Additionally, employing in vivo screening in live animals and whole-genome sequencing during the therapeutic process will facilitate monitoring and help mitigate potential off-target effects. Although there are significant obstacles to the clinical application of nucleic acid aptamers as therapeutic agents or delivery tools, their potential remains promising, especially with continued advancements in precision targeting and safety profiling.

APT-GC predominantly undergoes receptor-mediated endocytosis when taken up by GC cell lines HGC-27, MKN-45, NUGC-3, and SNU-638, with uptake saturation occurring at 300 nM. Intracellular stability is maintained for 2 hours, while serum stability persists for 6 hours. Its internalization by various cancer cells underscores its potential as a pan-cancer diagnostic and therapeutic agent.

GC, Gastric cancer; Cell-SELEX, cell-systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; FDA, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; AMD, age-related macular degeneration; GES1, human gastric mucosal epithelial cells; CO-IP, Co-Immunoprecipitation; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; CLDN18.2, claudin 18.2; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; SERS, Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; NCL-Apt, nucleolin-specific aptamer; DPBS, Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline; BSA, bovine serum albumin; LNA, locked nucleic acid; PEG, polyethylene glycol; CME, clathrin-mediated endocytosis; CvME, caveolae-mediated endocytosis; PTK7, protein tyrosine kinase 7.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

YT and GH designed the research study. XX, YT and YFX performed the research. YX, CZ, GS and BQ analyzed the data. YT, ZW, JL, JX and XY provided suggestions for the conception and design of the manuscript and also offered help and advice on the CO-IP and flow cytometry experiments. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The procedures in the manuscript were reviewed in advance by the Laboratory Animal Management Committee of The Central Hospital of Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture (No: 202406011) and also met the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Thanks to Prof. Jiangfeng Wu, Prof. Zhenglan Huang and Prof. Chuying Huang for their cell donations for this experiment. We thank Bullet Edits Limited for the linguistic editing and proofreading of the manuscript.

This research was funded by Hubei Province health and family planning scientific research project (WJ2023M179). Joint supported by Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation and Enshi Government of China (2024AFD084, 2023AFD063).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors used ChatGPT only to improve the language of the Discussion section, with an emphasis on improving clarity and correcting grammar. The scientific content was written entirely independently by the authors, without the use of AI tools. We hope that this clarification will resolve any issues with the use of AI in our submitted manuscript. The authors take all responsibility for the accuracy, integrity, and scientific rigor of the contents.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.