1 Group of Cross-Linking Enzymes, Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, 117997 Moscow, Russia

2 Laboratory of Tick-Borne Encephalitis and Other Viral Encephalitides, Chumakov Federal Scientific Center for Research and Development of Immune-and-Biological Products, 108819 Moscow, Russia

3 Vavilov Institute of General Genetics, 119991 Moscow, Russia

4 Department of Biomedical Sciences, School of Medicine, Nazarbayev University, 01000 Astana, Kazakhstan

Abstract

Lysine tyrosylquinone (LTQ), the cofactor formed through copper-assisted tyrosine oxidation and subsequent intramolecular cross-linking, is inherent in all members of the lysyl oxidase family. Lysyl oxidases are unique among amine oxidases in that they maintain the LTQ coenzyme in a relatively surface-exposed position, making it accessible for the oxidative deamination of lysine side chains in various proteins, especially in the extracellular matrix. This process facilitates the formation of intramolecular cross-links, which are vital for the normal development of skin, bones, aorta, and other tissues. Unfortunately, in accordance with the antagonistic pleiotropy theory of aging, the enzyme activity that is essential in youth may become non-optimal throughout the lifespan. One consequence of excessive lysyl oxidase and its ectopic activity in the nucleus is the promotion of stiffness in solid tumors and increased survival of metastasizing cells. Therefore, LTQ-dependent oxidative deamination, especially at the stage of LTQ formation, is a promising druggable target for future combination therapies aimed at treating the most lethal cancers.

Keywords

- amine oxidase

- cancer

- copper

- desmoplasia

- extracellular matrix

- lysine tyrosylquinone (LTQ)

- lysyl oxidase

- metastasis

- nuclear transport

- zinc

Cofactors of amine oxidases like flavine adenine dinucleotide (FAD), topaquinone (TPQ), and lysine tyrosylquinone (LTQ) were reviewed extensively in [1], our focus here is on LTQ, the tyrosine-derived cofactor essential for lysyl oxidase activity, due to its significant role in solid tumor growth and metastasis. Lysyl oxidases comprise a family of copper-dependent amine oxidases that catalyze the oxidation of primary amines to aldehydes (oxidative deamination). Since the discovery of lysyl oxidase enzymatic activity in the aorta [2], extensive research has been conducted, and several excellent reviews [3, 4] have explored different aspects of this remarkable enzyme. In this work, we aim to present a broader perspective, with a focus on cancer-related insights and areas of uncertainty that may inspire the development of novel hypotheses.

Lysyl oxidases are highly conserved proteins, particularly in their catalytic domains, and exhibit broad substrate specificity, primarily targeting lysine residues in proteins with an isoelectric point greater than 8. Given that their structural features do not significantly influence substrate selection, we hypothesize that the specificity of lysyl oxidase substrates might be regulated by interactions with other proteins.

Mutations in key tyrosine and lysine residues, or in the copper-binding site, result in a complete loss of enzyme function. This fact may guide the creation of new drugs for combination therapies targeting the most lethal solid cancers with intensive desmoplasia, such as pancreatic cancer. We seek to demonstrate the great potential of LTQ in amine oxidases (lysyl oxidases) for pharmacological applications in oncology.

In the human genome, there are genes encoding various amine oxidases with distinct yet overlapping substrate specificities. Remarkably, lysyl oxidases (LOXs) stand apart from other amine oxidases, as they accept lysine as a substrate, either in its free amino acid form or as a side chain in proteins and peptides.

In terms of cofactor usage, several FAD-dependent amine oxidases include monoamine oxidase (FAD-dependent: monoamine oxidase (MAO, MAO-B), spermine oxidase (SMO/SMOX), acetylpolyamine oxidase (PAOX, APAO), pipicolate oxidase (PSO/PIPOX), protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PPOX), renalase (RNLS), lysine-specific demethylase (LSD1/AOF2, LSD2/AOF1), L-amino acid oxidase (LAAO/IL4I1), D-amino acid oxidase (DAAO/DAO), D-aspartate oxidase (DDO). There are also copper-dependent TPQ-containing amine oxidases, including: amine oxidase copper containing 1 (AOC1) (DAO, ABP1, histaminase), AOC2 (retina-specific), AOC3 (semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase (SSAO), vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1)), AOC4 (pseudogene in humans). Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC) and other cytosine and adenine deaminases belong to distinct types. Cu-dependent TPQ-containing AOCs have been excellently reviewed in [5], it should be emphasized that AOCs are the most similar to LOXs in terms of biochemical properties, however, they are not homologous in terms of amino acid sequence.

Pyrroloquinoline quinone (PPQ) was initially assumed to be the cofactor for LOX [6]. Later, however, Wang et al. [7] surprisingly identified a new quinone cofactor in lysyl oxidase, formed by cross-linking between a modified tyrosine (Y349) and the

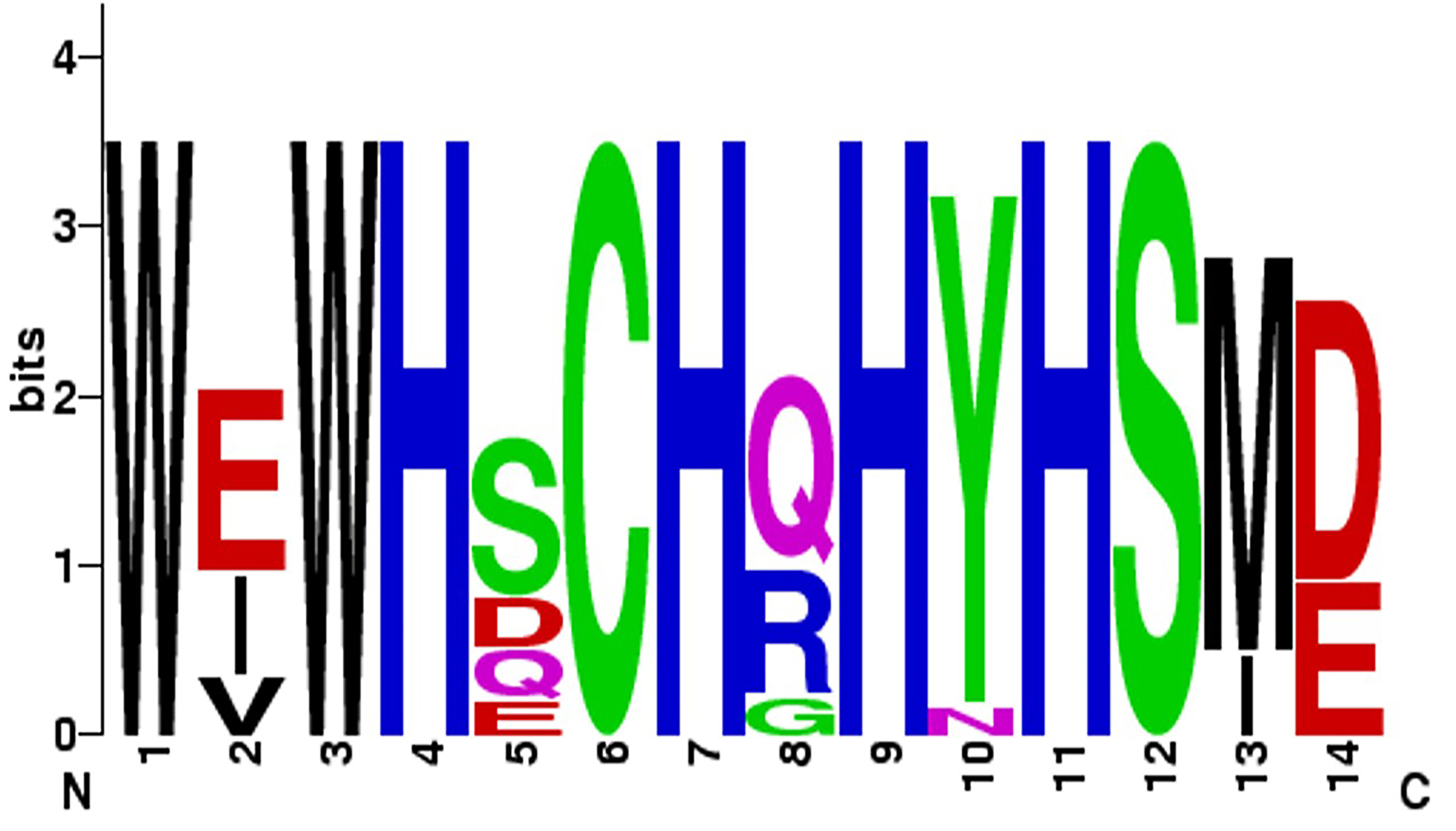

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Lysine tyrosylquinone (LTQ) cofactor in lysyl oxidases. (A) structure of LTQ; (B) amino acid sequence context for LTQ formation. Multiple alignment of the high homology region of catalytic domains of human lysyl oxidase isoforms with pediculus as an outgroup. Turquoise—histidine residues of the copper binding site; yellow—cysteine residues; red—lysine and tyrosine residues that form the LTQ cofactor.

LOXs readily oxidize various low-molecular-weight primary amines (such as histamine, cadaverine etc., indeed many various primary amines are good substrates [12]), as well as the

RCH2NH2 + H2O + O2

(1) LOXox + RCH2NH2

(2) LOXred(-NH2) + O2 + H2O

During the reaction of LTQ with lysine, a Schiff base is formed, which then undergoes rate-limiting deprotonation to form aldimine. Its hydrolysis leads to the formation of an aldehyde, allysine in case of lysine. Then molecular oxygen, copper and water regenerate LTQ. From a stereochemical perspective, enzyme reoxidation is the rate-limiting step of the two half-reactions catalyzed by this ping-pong enzyme. The alcohol derived from the reduction of the aldehyde product of the lysyl oxidase-catalyzed oxidation of deuterated tyramine showed that the pro-S, but not the pro-R, alpha-deuteron was selectively abstracted at the rate-limiting stage of the catalytic cycle. Additionally, lysyl oxidase catalyzes the exchange of protons at the C-2 position. This stereospecificity and proton exchange profile distinctly differentiate lysyl oxidase from all other mammalian copper-dependent amine oxidases analyzed to date, with the exception of AOC3 [13].

The allysines then spontaneously react with other lysine or hydroxylysine residues to form covalent bonds and thus cross-linked polypeptide products: peptidyl-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Initiation of cross-link formation upon oxidative deamination of lysine residues in proteins.

Five distinct lysyl oxidases have been identified in mammals (LOX and lysyl oxidase-like protein (LOXL) 1–4), all sharing a highly conserved catalytic C-terminal domain but exhibiting significant variation in the amino acid composition of their remaining domains. While most animal genomes contain from one to five LOXs genes, homologous genes are not found in plants and are exceedingly rare in fungi. Remarkably, the vast majority of prokaryotic genomes also lack LOXs genes, however, true prokaryotic homologs of lysyl oxidase can be found in a scattered pattern, reflecting the evolutionary history of this enzyme, and suggesting that the LOXs genes have undergone repeated horizontal transfers. Indeed, lysyl oxidase is commonly found in actinomycetes, occasionally in other Eubacteria, and very rarely in Archaea. In Prokaryota, lysyl oxidases were unknown before bioinformatic predictions [14] by searches with the use of hyperconserved residues around lysine and tyrosine, which are immediately involved in the formation of LTQ. The first experimental validation was achieved with a lysyl oxidase from a halophilic archaeon; notably, this activity was not detected in extracts from the haloarchaeon cells but was observed only after expression and purification in E. coli [15]. Thus, it is feasible that LOXs genes persist in evolution as cryptic genes, not producing significant amounts of catalytically active proteins, but ready to be activated in cases of atypical metabolic requirements, e.g., deamination of a peculiar primary amine as the sole nitrogen source. This aspect is of greatest interest not only from a phylogenetic point of view, but also for possible biotechnological applications, since distantly related enzymes may have interestingly divergent properties.

While lysyl oxidases are absent in most bacteria, leading to the assumption that they are not important for infection, their potential significance may be uncovered in future studies. Indeed, there are parallels with other oxidative enzymes that are rare among microorganisms; for example, lipoxygenases (arachidonate lipoxygenases (ALOXs), sometimes confusingly referred to as LOXs in some enzyme nomenclatures) are found only in a few bacterial taxa and, among pathogenic bacteria, in specific strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [16].

What is the true origin of animal lysyl oxidases? Were they acquired from bacteria by early animals at the dawn of their evolution, as has often occurred with other genes? Or, conversely, may it be possible that an animal LOX gene could have escaped into the microbial world? The latter scenario is less likely due to the presence of intron-exon structures in animal genes, yet it offers a simpler explanation for the evolutionary pattern of domain composition across animals and bacteria. Only the fact of repeated “jumps” between groups of prokaryotes is obvious. Also, the question remains as to what drove the emergence of multiple isoforms of lysyl oxidases in vertebrates. Based on the analysis of the evolution of collagen domains, it has been hypothesized that LOXs enzymes may have originated in an ancestral lineage predating the emergence of Metazoa [17].

The most likely oxidation target sites in protein substrates appear to be the lysine-glycine-proline (KGP) sequences in fibrillar collagen among invertebrates. In contrast, vertebrates display a greater diversity in oxidation sites (including KAH, KAG, KST, and KSG sequences), suggesting a more varied substrate specificity for their LOX enzymes. The LOXs enzymes in invertebrates, particularly those with scavenger receptor cysteine-rich (SRCR) domains, first emerged in sponges [17]. In these organisms, fibrillar collagen plays a key role in forming the collagen-rich mesohyl that functions as an endoskeleton supporting the sponge’s tubular shape. The broader range of potential oxidation sites in vertebrate fibrillar collagen has likely driven the diversification of vertebrate LOXs isoforms. This diversification lends support to the idea that specific isoforms of LOXs enzymes are better suited to distinct protein substrates of the extracellular matrix (ECM). It is also plausible that a horizontal gene transfer event occurred in the ancestors of chordates, introducing a prokaryotic lysyl oxidase with a different domain structure—specifically, possessing an autoinhibitory propeptide instead of SRCR domains. From the perspective of lysyl oxidase evolution, these variations are associated with the emergence of new lysyl oxidase architectures that lack SRCR domains (Figs. 3,4) but contain propeptides and proline-rich regions. These structural changes likely contributed to the expansion and diversification of collagen types in vertebrates [17].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Domain composition of human lysyl oxidases. SP, signal peptide; SRCR, scavenger receptor cysteine-rich; Cu, Cu2+ binding site; LOX, lysyl oxidase; LOPP, lysyl oxidase propeptide; CRL, cytokine-receptor like; LOX and LOXL1 are proteolytically processed by bone morphogenetic protein 1 (BMP-1).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Protein alignment scheme of human lysyl oxidases. An insect lysyl oxidase (Pediculus) serves as an outgroup. Highlighted disagreements to consensus: blue—RKH residues, red—DE residues. Identity graph: mean pairwise identity over all pairs in the column: green—100%, green-brown—30–100%, red—below 30%. Created with Geneious version 2023.2 by Biomatters (GraphPad Software, LLC (d.b.a. Geneious), 225 Franklin Street. Fl. 26, Boston, MA 02110, USA).

The catalytic activity of the apoenzyme can be experimentally boosted with Cu2+, in contrast to Zn2+, Co2+, Fe2+, Hg2+, Mg2+, or Cd2+. The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrum of bound Cu indicated that it is coordinated by three nitrogen atoms, presumably from histidine residues. Cu2+ has been proposed to be essential not only for the catalytic activity but also for maintaining the structural integrity of the protein [18]. In another experiment, in the active LOX enzyme the removal of copper did not fully inhibit lysyl oxidase activity, which can be readily explained by pre-formation of LTQ [19]. Thus there remains a controversy about the role of copper in the fully formed enzyme with LTQ, however, the majority of data stands for its important role in the catalysis. An expression system was developed that provides sufficient amounts of recombinant lysyl oxidase for detailed characterization of Drosophila lysyl oxidase, which is secreted upon baculovirus-mediated protein expression in an inactive form without LTQ and bound copper. This model demonstrated that LTQ formation is a spontaneous process that occurs in the presence of oxygen and requires copper in the active site. Under in vitro conditions, the formation of a functionally active LTQ form was observed in the recombinant protein when Cu2+ was present. Activation of LOX through the LTQ formation requires dialysis in the presence of copper and oxygen [20]. Indeed, long ago it has been suggested that H292, H294, H296, are the copper ligands (Fig. 5). Importantly, H303 was suggested to be a general base in the catalytic mechanism [21].

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Conservation of the copper-binding site in human lysyl oxidases.

Crystallization of the LOX isoform has not been reported, and only relatively recently LOXL2 has been successfully crystallized and resolved at 2.4 Å (Fig. 6) in an inactive form with bound zinc instead of copper [22]. This protein, hLOXL2 was expressed in mammalian cells (HEK293F) with the secretion into the medium. It contained a single point mutation (N455Q) and after proteolysis yielded a 318–774 fragment consisting of the third and fourth SRCR domains and an intact catalytic domain. All 22 cysteine residues are involved in disulfide bonds. The group A SRCR domain is characterized by one

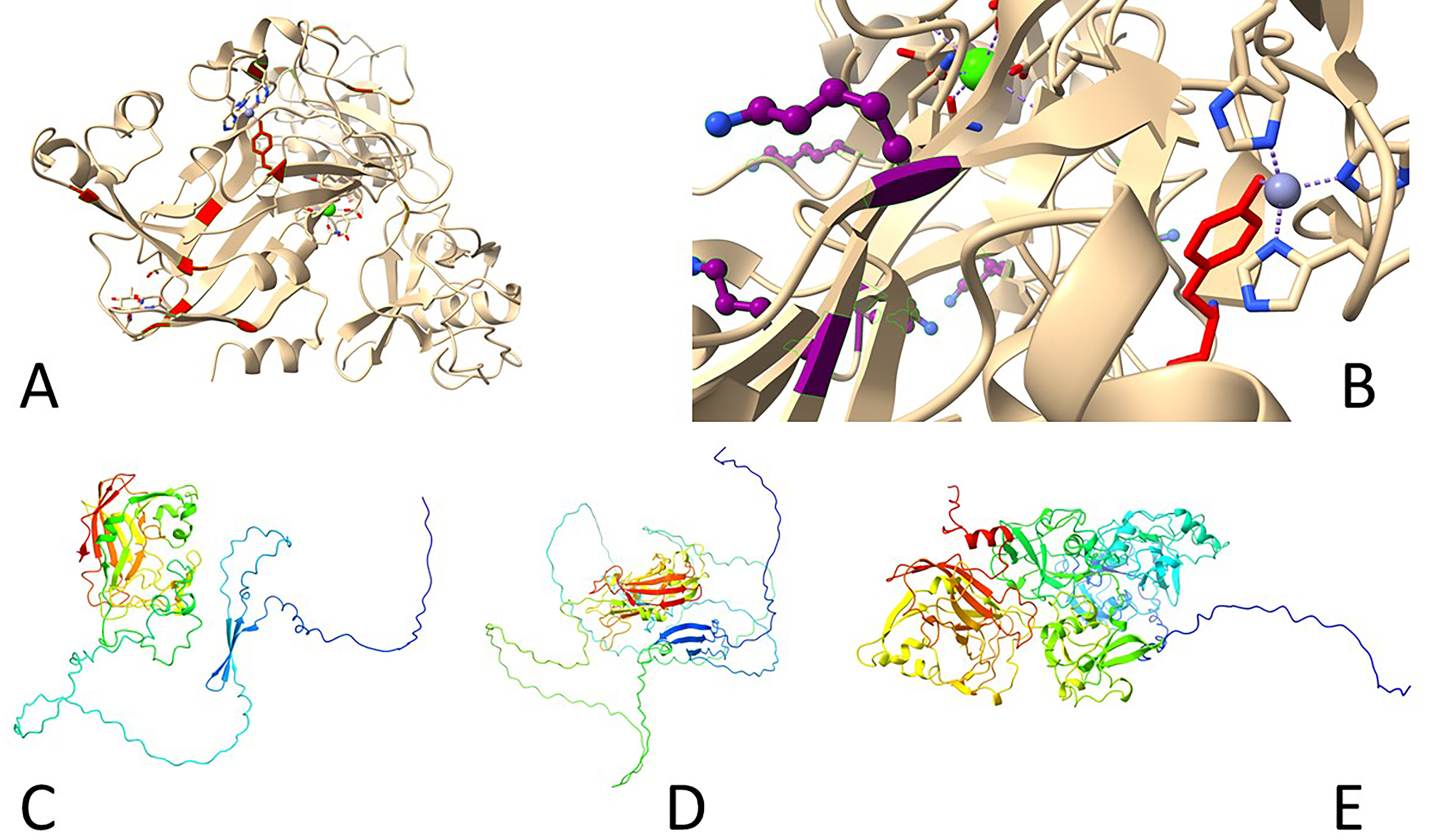

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Three-dimensional structures of human lysyl oxidases. (A,B) Reported inactive Zn-bound precursor of human LOXL2 (5ze3). (A) Tyrosine residues shown in red, including Y689 side chain. (B) Lysine residues shown in purple, note K653 turned away from Y689, which interacts with a Zn atom coordinated by three histidine residues (H626, H628, H630). (C–E) Predicted structures by AlphaFold 2 ((C) LOX, (D) LOXL1, (E) LOXL2). Note long N-terminal disordered portions.

Since LOXs catalyze the deamination of lysine side chains in protein substrates, unlike other amine oxidases, this requires accessibility of LTQ to bulky molecules without any steric hindrance. Indeed, the side chain of the LTQ precursor Y689 is exposed on the protein surface, with the copper-binding motif also open to the solvent [22]. Quantum mechanics and molecular mechanics evaluations of the LOXL2 reaction mechanism suggest that the biosynthesis of the cofactor LTQ is highly exothermic, with an energy release of about 284 kJ/mol [23]. However, it is unclear whether the copper ion acts as a redox catalyst in the final aldehyde formation step. The other interesting remaining question is whether Zn2+-substituted LOXL2 may serve as a precursor of active lysyl oxidase upon exchange of zinc for copper [22] or whether such inactive enzyme has a yet unknown function [23]. Notably, when probed with an inhibitory antibody, AB0023, surprising results were observed. Structural studies reveal that LOXL2, this particular isoform at least, is an elongated molecule, but AB0023 binds to a non-catalytic cysteine-rich domain (SRCR2, domain 4) of LOXL2, away from the catalytic site. This suggests that AB0023 acts as an allosteric inhibitor, blocking LOXL2 activity in a non-competitive manner, independent of substrate concentration [24].

When recombinant LOXL2 reacts with 2-hydrazinopyridine (2HP), it forms a product with the absorbance peak around 531 nm, allowing differentiation between LOXL2 and the copper amine oxidases (CAOs), particularly regarding their quinone cofactors, LTQ and TPQ, respectively. In mature LOXL2, the LTQ cofactor is thus expected to be located approximately 2.9 Å from the Cu2+ active site, with both the LTQ and Cu2+ binding sites exposed to the solvent. The roles of some other key residues were successfully demonstrated: the LTQ formation dropped from 93% in the wild-type enzyme to 36% in the H303I mutant, and was completely blocked in the H303D and H303E mutants. Additionally, the catalytic activity of these mutants was undetectable when compared to the wild-type enzyme. Further studies on the LTQ-cofactor formation using model compounds has demonstrated that the specific 1,4-cross-linking of tyrosine with the

The incorporation of copper into lysyl oxidase occurs during the proenzyme stage, as confirmed both in vitro using a cell-free transcription/translation system and in vivo with human skin fibroblast cultures. Neither blocking glycosylation with tunicamycin nor inhibiting proenzyme processing using a specific procollagen-C-peptidase inhibitor affected the secretion of copper-containing lysyl oxidase. However, cycloheximide-mediated inhibition of protein synthesis led to reduced levels of the copper-containing enzyme in fibroblast culture media. Additionally, disruption of the Golgi complex by brefeldin A not only blocked proenzyme secretion but also reduced intracellular levels of copper-containing lysyl oxidase. These findings indicate that copper incorporation into the lysyl oxidase proenzyme occurs as it passes through the Golgi complex. Efficient delivery of copper to the Golgi complex relies on the coordinated action of intracellular copper transport components, particularly the copper-transporting ATPase Cu-ATPase 7A (encoded by the ATP7A gene). This ATPase is especially active in tissues with high synthesis of ECM proteins and in mesenchymal cells. The production of active lysyl oxidase is closely linked to the function of Cu-ATPase 7A. Inhibition of this ATPase by methavanadate resulted in reduced quinone-dependent redox activity of lysyl oxidase (this interesting observation is, however, of unclear significance because of the non-specific action of methavanadate on other ATP-dependent enzymes). A similar reduction in enzymatic activity has been observed in Menkes syndrome, which is characterized by mutations in the ATP7A gene. Furthermore, the interaction with fibulin-4 facilitates the proper transport of copper ions from the copper transporter ATP7A to LOXs within the trans-Golgi network (TGN), a crucial step for efficient LTQ formation [28]. Additionally, in breast cancer patients, high ATP7A expression is significantly associated with decreased survival rates [29], underscoring the critical role of optimal copper transport in eukaryotic cells.

Irreversible inhibition occurs in a time- and temperature-dependent manner when the enzyme is incubated with

The entire amino acid sequence of prolysyl oxidase (proLOX) can be divided into two functional regions (Fig. 3): The N-terminal region, known as the propeptide domain (lysyl oxidase propeptide (LOPP)), and the C-terminal region, referred to as the catalytic domain. The catalytic domain represents the mature, proteolytically activated form of lysyl oxidase (mature lysyl oxidase (mLOX)). Notably, the catalytic domain is highly conserved in all lysyl oxidase family members across different species. For example, the homology with mouse mLOX is 98% for rat (Rattus norvegicus), 98% for human (Homo sapiens), 96% for cow (Bos taurus), 94% for chicken (Gallus gallus), and 87% for fish (Danio rerio). Within the catalytic domain, the most conserved elements include the copper-binding site (WXWHXCHXHXHYH (Fig. 5), where X is any amino acid), 10 cysteine residues, the lysine and tyrosine residues involved in cofactor formation, and a sequence similar to ligand-binding domains of cytokine and growth factor receptors.

In contrast, the N-terminal domain varies greatly in both amino acid composition and length across all lysyl oxidase family members. A notable feature of LOPP is its high content of polar amino acids (Arg, Gln, Ser, Glu) and absence of cysteine residues, suggesting that LOPP may have a disordered structure (Fig. 6C). Sequence analysis and experimental data indicate the presence of three N-glycosylation sites and a single O-glycosylation site in the propeptide, which likely accounts for its electrophoretic mobility. Additionally, sequence analysis of the LOX propeptide suggests the presence of a nuclear localization signal.

The N-terminal propeptide domains of LOXL2–4 exhibit structures distinct from the propeptide regions of LOX and LOXL1, containing four repeats of the SRCR domain (Figs. 3,4). Domains of SRCR type, approximately 100 amino acids long, containing 6 to 8 cysteine residues, are present in many secreted proteins associated with the plasma membrane, such as lymphocyte glycoproteins CD5 and CD6. LOXL2, LOXL3, and LOXL4 share a similar molecular organization to LOXL2. The LOXL3 gene, which spans 22 kb and contains 14 exons, encodes a protein with 753 amino acid residues. The N-terminal part of LOXL3 shares 55% homology with LOXL2 and contains four conserved SRCR repeats. A distinct feature of LOXL3 is the presence of a bivalent nuclear localization signal (K293KQQQQQSKSKPQGEARVRLKG311), not found in other isoforms. LOXL4, the most recently identified lysyl oxidase isoform with a polypeptide chain length of 756 amino acids, also contains four SRCR repeats. Its gene is located on chromosome 10 and shares similar structural characteristics with LOXL2 and LOXL3. The presence of an N-terminal signal peptide suggests that LOXL4 functions as a secretory protein.

Thus, the mammalian lysyl oxidase family consists of five isoforms, which can be categorized into two groups based on the structure of their N-terminal propeptide regions: one group contains isoforms with SRCR domains, while the second group consists of those without SRCR domains (Fig. 3). Analysis of the intron-exon structure of lysyl oxidase genes suggests that they are evolutionarily related. However, a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of lysyl oxidase protein sequences across various multicellular animal species is required for a clearer understanding of their evolutionary development. For comparison with evolutionary distant homologs, insect lysyl oxidases should be mentioned. Based on their N-terminal domains, Drosophila lysyl oxidases fall into the group of SRCR-domain-containing lysyl oxidases, although they possess a different number of SRCR domains compared to mammals (two in DmLOXL2 and one in DmLOXL1). These Drosophila lysyl oxidases are functional in their SRCR form and likely do not undergo proteolytic maturation [31].

Knockout of lysyl oxidase isoforms results in numerous developmental defects that are closely linked to ECM deformation. For example, murine LOX is essential for cardiovascular development, as LOX knockout mice exhibit zero survival rates due to aortic aneurysms and cardiovascular dysfunction in the perinatal period. In the lungs of E18.5 LOX(-/-) embryos, developmental abnormalities were observed, characterized by sparse and defective collagen fibers [32]. Exposure of zebrafish Danio embryos to BAPN or copper deficiency induces notochord deformities, highlighting the critical and evolutionary ancient role of lysyl oxidases in development [33]. Furthermore, overexpression of both LOX and bone morphogenetic protein 1 (BMP-1) simultaneously, but not individually, leads to a significant increase in collagen deposition in vitro [34].

When considering the overall expression profile of lysyl oxidases across organs and tissues, it is challenging to pinpoint the dominant influence of specific isoforms on organ development and function. This is because, with rare exceptions, each lysyl oxidase family member is expressed at low levels in nearly all organs and tissues. Since all isoforms are active toward various types of collagen (with varying degrees of specificity) and elastin, this distribution allows for a complementary and, to some extent, compensatory cross-linking activity among lysyl oxidases. However, detailed study focusing on the localization, expression regulation, and effects of enzyme deficiency indicate that each isoform exhibits unique functional roles in specific tissues, influencing the formation and function of organs. It is plausible that all lysyl oxidase isoforms work together as a coordinated system to support the formation and maintenance of the structural integrity of organs and tissues during growth and development, this may be illustrated by a dynamic regulation of lysyl oxidase isoforms in the developing rat aorta [35].

LOX is ubiquitously expressed but relatively low in the brain; highest levels are found in adipose tissue, various fibroblast cells, and the endothelium. LOX lysyl oxidase was the first among mammalian lysyl oxidases to be identified, so it is the most characterized and most studied to date. The importance of LOX in the aorta has been clearly demonstrated, for example, severe aneurysms have been reported in newborn LOX knockout mice [36]. Even more important was the demonstration that, in humans, hereditary thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections may be caused by a single missense mutation, giving M298R mutant of the LOX protein, and this have been successfully confirmed in mice [37].

LOXL1: ubiquitously expressed, with relatively low levels in the brain; highest expression is observed in the heart and placenta, particularly in endothelial and trophoblast cells. LOXL1 knockout mice developed pelvic organ prolapse, as well as deformities in the lungs, skin and blood vessels [38].

LOXL2: ubiquitously expressed but low in the brain; it is highly expressed in endothelial and smooth muscle cells, as well as in oocyte germ cells, and in chondrocytes. LOXL2 knockout gave cardiac defects and high newborn lethality [39].

LOXL3: Expressed throughout the body but at relatively low levels; its highest expression is in the placenta and bone marrow, particularly in Hofbauer cells. LOXL3 knockout mice had numerous deformities in cartilages [40], and lungs [41].

LOXL4: Ubiquitously expressed, with low levels in the brain and blood cells; it shows the highest expression in respiratory ciliated cells.

These expression patterns and correlations suggest that while lysyl oxidases are ubiquitously distributed across tissues, their specific roles and impact on disease states vary by isoform and tissue type, although some of their functions may overlap [42].

Regarding protein and peptide substrates, it is evident that the sequences in the immediate vicinity of the lysine residues of the substrate have a significant impact on lysyl oxidase (LOX) activity [43], and LOX is particularly sensitive to negatively charged amino acid residues near lysine [43]. For example, the presence of Glu residues at the N-terminus relative to lysine significantly enhances LOX catalytic activity compared to peptides where Glu is located C-terminally to lysine. This effect is not observed with Gln or Asp [44]. LOX efficiently oxidizes basic globular proteins (isoelectric point

LOX was first identified during studies on osteolathyrism, a pathological condition characterized by abnormalities in blood vessels (e.g., aortic aneurysms), skin, and bone formation. This condition was observed in experimental animals consuming large amounts of Lathyrus odoratus seeds, which led to the term “osteolathyrism” (distinct from “neurolathyrism”, caused by Lathyrus sativus). Subsequent research [46] identified BAPN as the active compound in these seeds responsible for osteolathyrism. BAPN inhibits the enzymatic formation of cross-links in ECM proteins like collagen and elastin, and the enzyme responsible for this cross-linking was later identified as lysyl oxidase.

Fibrosis, an abnormal wound-healing process, heavily relies on ECM protein cross-linking, a process strongly promoted by lysyl oxidases. This is especially evident in the lungs, where LOXL4 plays a key role [47]. In the liver, LOXL2 appears to be a more important isoform [48], indicating that different lysyl oxidase isoforms may have specific roles in ECM repair, though their exact functions remain somewhat ambiguous. The role of lysyl oxidases in wound healing is quite complex, for example, its activity may contribute to excessive joint calcification after trauma as shown in meniscectomized mice [49]. Also, lysyl oxidases can be employed to improve mechanic properties of artificial tissues [50].

Interestingly, LOX deficiency in mice has been shown to reduce atherosclerotic calcification and the burden of age-related vascular stiffness [51], delaying the onset of systolic hypertension [52]. Also, LOX promotes aortic stiffness in chronic kidney disease [53]. These findings illustrate a striking example of antagonistic pleiotropy. While lysyl oxidases are essential for proper development, their excessive activity over the lifespan can be detrimental—and in fact some experiments showed a decrease in lysyl oxidase expression with aging [54]. However, this theory is not entirely straightforward, as evidenced by interesting findings such as hearing loss in aging mice promoted in the absence of intact LOXL3 [55].

For LOX in vitro, it has been demonstrated that a 47 kDa precursor is initially formed, which then undergoes removal of the signal peptide and N-glycosylation at the propeptide domain (LOPP), resulting in a 50 kDa precursor, termed proLOX. Upon secretion into the extracellular space, proLOX is converted into a 32 kDa non-glycosylated, catalytically active protein known as the mLOX. This conversion is achieved through site-specific proteolysis. The proteolytic cleavage of the proenzyme occurs at the Gly168/Asp169 site (in the human LOX sequence), which is conserved across the amino acid sequences of LOX from various vertebrates [17, 56]. The primary protease involved in the maturation of lysyl oxidase is procollagen-proteinase-C, which is also responsible for removing the C-terminal propeptides of procollagens I-III, playing a crucial role in the formation of mature collagen fibers in the ECM. There are two splice variants of the BMP-1 gene that produce procollagen-proteinase-C: bone morphogenetic protein 1 (BMP-1) and mammalian Tolloid (mTLD). Among these, BMP-1 is approximately 20 times more efficient in processing prolysyl oxidase (proLOX). Additionally, two other proteases—mTLL-1 and mTLL-2 (mammalian Tolloid-like proteins)—also exhibit procollagen-C protease activity and contribute to the post-translational maturation of lysyl oxidase [19]. BMP-1 plays a crucial role in the cleavage of LOX and LOXL1, but not LOXL2 [57].

Differences in the isoforms suggest that not all lysyl oxidases are dependent on proteolytic processing in terms of LTQ formation, and only LOX and LOXL1 are further activated by the removal of their LOPPs [58]. LOXL2 undergoes extracellular processing by serine proteases, resulting in a 65 kDa protein that lacks the first two SRCR domains. A site-specific mutant resistant to this proteolysis is unable to cross-link insoluble collagen IV in the ECM, unlike the fully processed form of LOXL2 [59]. Moreover, cleavage of the two N-terminal domains may induce a conformational change, bringing the SRCR domain 3 closer to the catalytic site. While this change is not directly associated with enzyme activation, it may modulate substrate binding [60]. Further, studies involving incubation with recombinant forms of these convertases have demonstrated that paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme 4 (PACE4) is the primary protease acting on extracellular LOXL2 [61, 62]. In the case of collagen cross-linking, the cleavage of LOXL2 increases the degree of cross-linking by approximately twofold at concentrations

Significant efforts have been made to optimize protein partner search methods, such as utilizing the yeast two-hybrid system. This approach led to the identification of placental lactogen (PL), typically expressed only in placental syncytiotrophoblast but occasionally amplified in breast cancer. Although PL is neither a substrate nor an inhibitor of LOX, the co-expression of LOX and PL significantly increased cell proliferation [63]. In a yeast two-hybrid system, Fogelgren et al. [64] identified an interaction between LOX and fibronectin using a placenta cDNA library. Fibronectin is a high molecular weight glycoprotein that is synthesized and secreted into the intercellular space by many cell types. It functions as a dimer composed of two similar subunits, 220 and 250 kDa, linked by disulfide bridges at their C-termini [64]. Fibronectin exists in two conformational states: soluble (plasma fibronectin (pFN)) and insoluble (cellular fibronectin (cFN)). LOX specifically interacts with the insoluble cFN form, while fibronectin can bind both mLOX and proLOX forms. Fibronectin is not a substrate for lysyl oxidase, neither it inhibits LOX activity. Interestingly, embryonic fibroblasts from fibronectin-knockout mice exhibit reduced conversion of proLOX to its active form. The role of the cFN/LOX interaction in the formation of the ECM structure remains unclear. It is possible that fibronectin binding to the active LOX promotes specific cross-linking of ECM proteins. Additionally, fibronectin’s ability to stimulate proLOX maturation suggests that its presence is crucial for LOX processing in vivo. This may explain discrepancies observed between LOX mRNA levels and its enzymatic activity, such as the delayed peak of LOX activity following tissue injury, occurring 8–10 days after the initial rapid accumulation of LOX mRNA. LOX activation could require sufficient accumulation of cFN/proLOX complexes, making the proteolytic processing site of proLOX more accessible to BMP-1 protease. Moreover, fibronectin may facilitate the proper assembly of the LOX/BMP-1/procollagen complex and consequently the cross-linked structure of the collagens in ECM.

Interactions between different lysyl oxidase isoforms and fibulin-5 and fibulin-4 are similarly critical for forming the elastin matrix. Fibulin-5 and fibulin-4 are homologous proteins of the “short” fibulin class II, characterized by six tandem calcium-binding epidermal growth factor (EGF) domains (cbEGF domains) and a globular C-terminal fibulin module. Fibulin-5 possesses a conserved RGD motif (Arg-Gly-Asp), which allows it to bind cell surface integrins—a feature not present in fibulin-4. In yeast two-hybrid screening, fibulin-5 C-terminal domain was found to interact with the N-terminal sequence of LOXL1. Further studies confirmed fibulin-5 ability to bind other lysyl oxidase isoforms, particularly LOXL2 and LOXL4, with weaker interactions noted for LOX and LOXL3 [65, 66]. The detection of the LOXL1 propeptide domain in the skin of fibulin-5 knockout mice, unlike in wild-type mice, implies that fibulin-5 is involved in LOXL1 activation [65]. Fibulin-4 strongly interacts with proLOX through its N-terminal domain and the propeptide domain of proLOX, which is vital for the binding of lysyl oxidase to tropoelastin molecules. Notably, proLOX is unable to bind to tropoelastin immobilized on a solid surface in the absence of fibulin-4, which itself has a binding affinity for tropoelastin. This suggests that fibulin-4 directs lysyl oxidase to elastin fibers by tethering proLOX to tropoelastin [38]. Also, fibulin-4 may be required for Cu2+ transport from the copper transporter ATP7A to LOX in the trans-Golgi network (TGN), which is a necessary step for LTQ formation [66].

Surface plasmon resonance and bio-layer interferometry binding assays, combined with bioinformatic analysis of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks from databases, have demonstrated that the interactomes of lysyl oxidase isoforms are complex and exhibit minimal overlap, sharing only a single partner: epidermal growth factor-like protein 7. The lysyl oxidase family interactome is notably enriched with ECM components (matrisome) and plays a significant role in ECM organization. This includes involvement in collagen fibril and elastic fiber formation, collagen degradation, and functional processes such as “cellular response to heat stress”, “signal transduction”, and “organ development”, including “blood vessel development”. Interestingly, in tumor cells, the lysyl oxidase family appears to have an expanded network of confirmed partners compared to normal cells, suggesting a rearrangement of the lysyl oxidase family interactome in cancer. This rearrangement is characterized by a shift from preferential activity within the ECM to interactions with various intracellular proteins [67].

The role of additional interacting partners is also significant. For example, it has been observed that periostin enhances the activity of BMP-1 on LOX, facilitating a triple interaction that promotes the proteolytic activation of lysyl oxidase [68].

The role of the nuclear pool of lysyl oxidases is intriguing. Initially detected in the nuclei of smooth muscle cells [69], the mature LOX, after secretion and proteolytic processing, can re-enter cells and accumulate within the nuclei. This nuclear localization appears to be specific and independent of the protein’s catalytic activity [70]. LOX has been found to co-localize with mitotic spindles from metaphase to telophase. Further purification of mitotic spindles from synchronized cells revealed that LOX does not associate with microtubules in the presence of nocodazole, a polymerization inhibitor, whereas paclitaxel, a polymer stabilizer, enhanced LOX staining, indicating that LOX specifically binds to stabilized microtubules. Furthermore, knockdown of LOX promoted cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase with decreased levels of p-H3(Ser10), cyclin B1, CDK1, and Aurora B, and increased sensitivity to cytostatic treatments [71]. Overexpression of LOX variants in HEK cells demonstrated subnuclear localization, with LOX-v2 specifically colocalizing with promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies (PML-NBs) [72].

To elucidate the role of LOX in the nucleus, two main questions must be addressed: how does the “classical” secreted protein enter the cell, and how is LOX transported into the nucleus? An analysis of the amino acid sequence of human ppLOX using the WoLF PSORT program identified a potential nuclear localization signal (PQRRRRDP, residues 66–72) within the propeptide domain (LOPP) [69]. Notably, no such nuclear localization signals were detected in the amino acid sequence of the mature enzyme. This suggests that nuclear transport of LOX may be mediated by the nuclear localization signal within the propeptide domain of the proenzyme form. Supporting this hypothesis is the detection of proLOX, LOPP, and mature LOX within the nuclei of differentiating osteoblast cultures. However, it remains unclear whether proLOX is transported directly to the nucleus without being secreted or if the secreted protein is reabsorbed by the cell. Kagan et al. [73] demonstrated that histone H1 serves as a substrate for lysyl oxidase in vitro. Analyzing the amino acid sequences of tropoelastin and histone H1, Giampuzzi et al. [74] identified at least three homologous regions containing the sequence AKAAAKAAAKAAAKA (or parts thereof, termed the AKA region). Since this sequence in tropoelastin is specifically recognized and modified by lysyl oxidase, its presence in histone H1 suggests that H1 may be an intranuclear substrate for LOX [75]. In protein interaction studies, lysyl oxidase was shown to bind the unphosphorylated form of histone H1 in vitro. Competition assays revealed that the presence of the AKA peptide significantly decreased the binding of H1 to LOX. Furthermore, both the catalytic and N-terminal regions of LOX appeared to contribute to the interaction with histone H1. In addition to histone H1, lysyl oxidase was capable of binding histone H2, another lysine-rich histone containing an AKA-like region. Recent finding [76] have demonstrated that overexpression of LOX enhances glucocorticoid-dependent activation of the Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus (MMTV) promoter and stimulates its activation even in the absence of hormonal influence on cells. The key regulator of the MMTV promoter is histone H1, whose phosphorylation decreases its positive charge, thereby weakening its interaction with DNA in the promoter region. This change makes the promoter more accessible to the transcription factor NF-1. The deaminating activity of lysyl oxidase similarly “relaxes” the H1/DNA complex, promoting MMTV promoter activation independently of histone H1 phosphorylation. The role of LOX in promoter activation via direct interaction with H1 was further confirmed by an increased presence of cross-linked desmosine and isodesmosine histone peptide products and the detection of a 66 kDa dimer band responsive to histone H1 antibodies [76]. The LOXL2 isoform is notably upregulated in the nuclei of lung fibroblasts and myofibroblasts following lung injury, particularly after exposure to transforming growth factor-

Concerning the problem of nuclear localization of lysyl oxidase, intranuclear proteins such as MDC1, p66

Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that LOXL4 is predominantly localized in the cytoplasm of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells but is also present in the nucleus [79]. Additionally, in more aggressive oral squamous cell carcinomas, LOXL1 exhibits a shift in subcellular localization, changing from diffuse cytoplasmic staining to heterogeneous perinuclear staining [80]. Interestingly, in the context of canine tumors, the situation appears to be reversed, with cytoplasmic lysyl oxidase exhibiting greater pathological significance than nuclear LOX [81].

Interestingly, recent evidence indicates that LOXL3, in certain experimental conditions, may also be transported to the mitochondria [82].

Early observations favored a tumor suppressor role for lysyl oxidases, for example, a decreased lysyl oxidase activity in cultured cancer cells was described attributing this to insufficient synthesis of the enzyme rather than impaired secretion into the cellular medium, since low activity was also found in urea extracts from cells. But this observation proved to be premature [83] as well as the discovery of its role as an enhancer of invasiveness and an inhibitory effect of BAPN in breast cancer cell lines have been published in 2002 [84]. Since then, most studies demonstrated strong pro-cancer pro-metastatic role of enzymatically active lysyl oxidases, and an excellent review on this topic may be recommended [85] for in depth reading. Particularly clearly this has been confirmed in LOXL2 overexpressing and LOXL2 knockout mice, where chemical carcinogenesis yielded opposing effects [39].

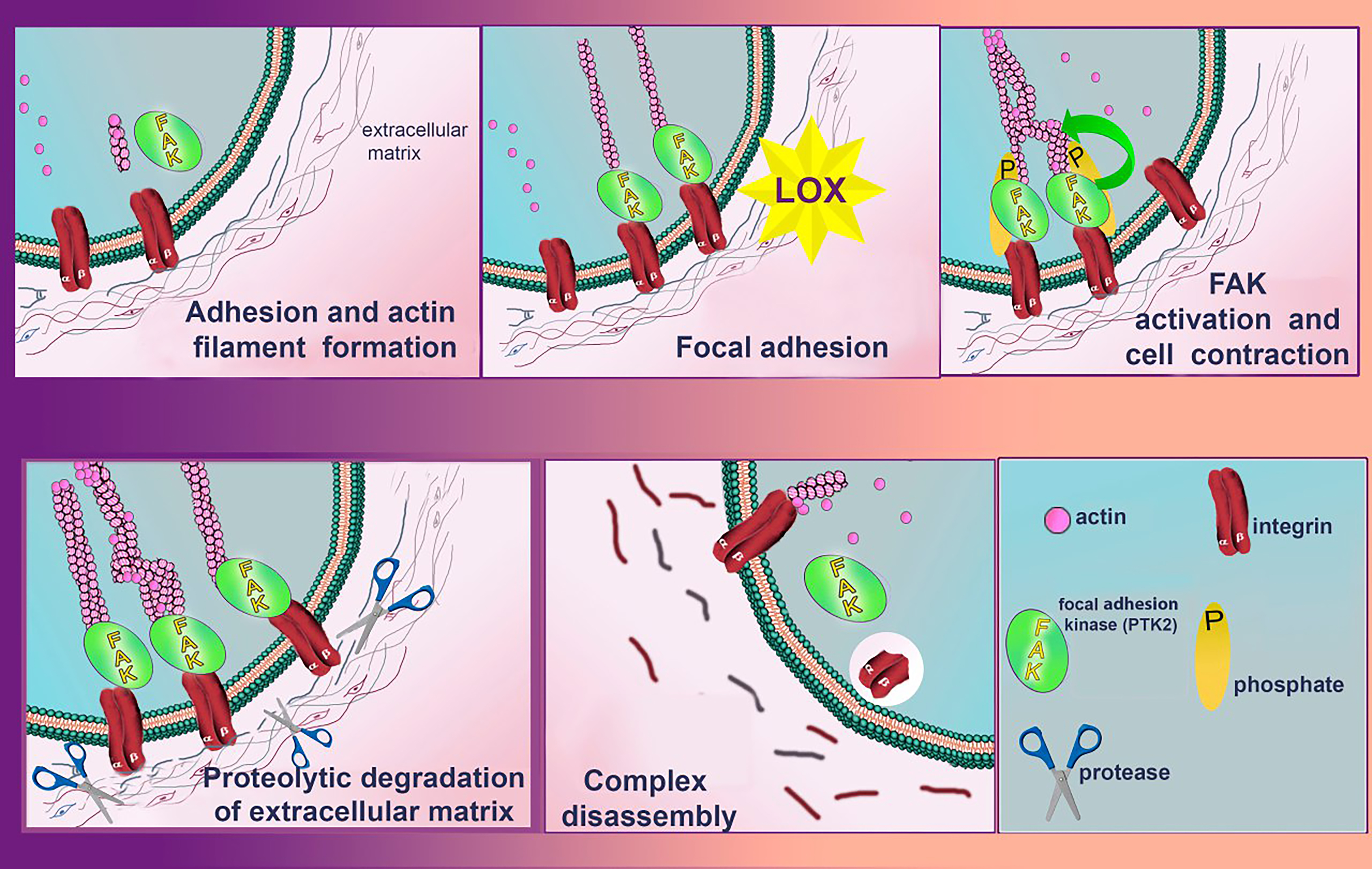

The predominant paradigm of the role of lysyl oxidases in cancer progression is shown in Fig. 7, but it should be emphasized that antagonistic mutually exclusive effects of lysyl oxidases are well noted [86]. For example, antibodies against LOXL2 in syngeneic orthotropic mouse models of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) reduce tissue stiffness and result in decreased overall survival [87]. Indeed, liver metastases of PDAC, a major cause of mortality, have higher tumor cellularity and less rigid stroma in comparison with primary tumors. Therefore, the ideas of reducing stromal rigidity should be treated with caution [87]. These ambiguities may be satisfactorily resolved by the recently published results on genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) of PDAC. There, the absence of LOXL2 has little effect on the development and growth of the primary tumor, but significantly reduces metastasis and increases overall survival – this is associated with non-cell autonomous factors, primarily ECM remodeling. In contrast, LOXL2 overexpression promoted the growth of primary and metastatic tumors and decreased overall survival, which may be related to enhanced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and stemness. In these model tumors, oncostatin M (OSM) secreted by tumor macrophages is the inducer of LOXL2 expression [88].

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Role of LOXs in controlling cell migration activity via focal adhesion kinase (FAK)/Src signaling pathway. LOXs enzymatic activity increases the stiffness of the extracellular matrix (ECM), which leads to clustering of integrins. The clustered integrins affect FAK phosphorylation and trigger a subsequent signaling cascade that eventually leads to the formation of lamellopodium and phyllopodium actin fibers and stimulates cell migration. In parallel, the LOXs-catalyzed oxidation reaction releases hydrogen peroxide, also stimulating the activation of the FAK/Src signaling pathway. During proteolytic degradation of the ECM, FAK signaling complex and actin filaments of filopodia and lamellopodia dissociate. Created with Adobe Photoshop.

While lysyl oxidase activity is known to correlate with metastatic tumor progression, there are also cases where increased expression of LOX can limit the oncogenic effects of the HRAS oncogene. Moreover, overexpression of the LOX propeptide domain (LOPP) acts antagonistically to mature LOX (mLOX). Thus, it appears that mLOX and LOPP have opposing roles, acting to balance each other’s activities and regulate normal cellular behavior. In the context of cancer, the imbalance between these two components may contribute to tumor progression [89, 90]. An example of this dynamic is the impact of LOX and LOPP on the FAK/Src signaling cascade, which is crucial for controlling cell migration (Fig. 7). While mLOX promotes the activity of this pathway, LOPP inhibits it, suggesting a balancing mechanism in non-invasive cells where LOPP’s regulatory effect either dominates or counteracts that of mLOX. However, in tumors, elevated fibronectin expression enhances proenzyme processing, leading to increased clustering of integrins and activation of the FAK/Src pathway. This likely shifts the equilibrium toward mLOX activity, promoting increased cancer cell invasiveness.

LOX activity acts as a negative regulator of trophoblastic cell invasion, in stark contrast to its role in cancer cells. Therefore, at early stages, LOX may play a protective role [91]. It is also noteworthy that lysyl oxidase-mediated oxidation is not limited to the ECM; it also targets cell surface proteins, which can significantly regulate cell motility [92]. Additionally, LOPP was found to suppress Her-2/neu tumor formation in a xenotransplantation model using nude mice. It achieved this by inhibiting the activation of Akt and nuclear factor-

At least in some experimental settings, the roles of lysyl oxidases in the communication between cancer cells and associated fibroblasts (CAFs) have been deciphered quite precisely. LOX produced by tumor-associated macrophages in the liver promotes the formation and growth of the metastatic niche where tumor cells secrete TGF-

Numerous bioinformatic analyses have demonstrated correlations between increased expression of lysyl oxidase isoforms and decreased patient survival. For instance, a recent study highlights this relationship with LOXL1 in colorectal cancer [75]. Another study demonstrated that elevated expression of LOXL4 is associated with reduced survival of patients with squamous cell carcinomas, even after surgical intervention [96]. Similarly, LOXL2 has been identified as an indicator of poor prognosis in early-stage human squamous cell carcinomas [97]. Also, in head and neck carcinoma (HNC) compared to normal squamous epithelium, LOXL4 transcript overexpression has been observed in 74% (46 of 62) of invasive HNC tumors and 90% of primary and metastatic HNC cell lines. Furthermore, a correlation has been identified between LOXL4 expression and local metastasis to lymph nodes compared to primary tumor types [39, 96].

Yet, there are reports that at least in certain tumors like larynx cancer some isoforms may be tumor suppressive, i.e., its increase in expression improves survival [98]. Interestingly, elevated expression levels of MAO, AOC, and LOX have been observed in certain tumors [99]. This suggests that if similar enzymatic actions from these different amine oxidases—which lack amino acid sequence homology and utilize distinct coenzymes—contribute to cancer aggressiveness through their overlapping enzymatic activities on low-molecular-weight substrates, then targeting a single component (such as lysyl oxidase with a small molecule inhibitor or LOXL2 with a monoclonal antibody) may have limited efficacy in practical cancer therapies.

It should be noted that, although increased expression of individual lysyl oxidase isoforms often correlates with poorer survival outcomes, only a combined family score—along with histochemical findings on the structure of collagen networks in the tumor stroma (e.g., picrosirius red staining)—shows unequivocally strong correlations. This is particularly evident in PDAC, which is notorious for its desmoplasia. These findings underscore the importance of inclusion lysyl oxidase inhibition in therapeutic strategies for such cancers [76].

In melanoma, LOXL3 promotes tumor growth in vivo and cooperates with oncogenic BRAF. Silencing LOXL3 impairs cell proliferation and induces apoptosis across various melanoma cell lines. Remarkably, an unexpected role of LOXL3 in maintaining genome stability and influencing melanoma progression has been identified. Depletion of LOXL3 leads to the accumulation of DNA double-strand breaks and abnormal mitosis. Furthermore, LOXL3 has been found to bind proteins involved in genome integrity, specifically BRCA2 and MSH2 [100].

In glioblastoma, the upregulation of LOXL1 is strongly associated with tumor invasion, likely facilitated by an EMT-like pathway and accompanied by the infiltration of immune cells [101].

Regarding the role of lysyl oxidases in metastasis, their involvement in EMT should be highlighted. A key factor in EMT induction is ZEB1, which can enhance LOXL2 transcription by directly binding to its promoter. Notably, elevated expression of both ZEB1 and LOXL2 is strongly associated with lymph node metastasis [102]. One of the most intriguing questions today concerns the mechanisms by which lysyl oxidase mediates the repression of the E-cadherin gene (CDH1), a process crucial for mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET), a key step in metastatic tumor progression. It is well-established that both LOX and LOXL2 are necessary and sufficient for hypoxia-induced repression of CDH1, and that this repression is dependent on the enzymatic activity of these proteins. It is hypothesized that lysyl oxidases may directly participate in the transcriptional regulation of CDH1 in complexes with various gene repression factors. This hypothesis is supported by experiments utilizing CDH1 promoter reporter luciferase constructs [89, 103]. For instance, a shortened version of the CDH1 promoter, which lacks E-box regulatory elements (DNA sequences to which the main known repressors of this gene bind), fails to exhibit the same degree of repression. Potential transcriptional agents involved in this regulation include ZEB2, ZEB1, Snail, Twist, and TCF3—all of which are also regulated by hypoxia through hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1) activity. Interestingly, it is believed that LOX and LOXL2 repress CDH1 through independent mechanisms. LOX-mediated repression of E-cadherin may not directly alter the promoter state but rather operates indirectly by increasing the expression of the repressor factor Twist. This upregulation of Twist is facilitated by the catalytic activity of LOX under hypoxic conditions. However, this does not preclude the possibility that LOX may also have a direct role in CDH1 repression. Yeast two-hybrid screening of partners of Snail protein, one of the main repression factors of the cadherin-E gene, showed that representatives of the lysyl oxidase isoforms can be potential partners of Snail [89]. It was confirmed by immunoprecipitation that full-length Snail through its N-terminal repressor domain SNAG is able to bind to the catalytic domain of LOXL2 and LOXL3. The interaction between LOXL2 and Snail had a more pronounced effect on the expression level of cadherin-E than LOXL2 and Snail alone. The existing hypothesis explaining how the Snail protein and LOXL2 interaction is involved in CDH1 gene repression is based on the assumption that LOXL2 performs oxidative deamination of lysine residues K98 and K137 in the Snail molecule, thereby promoting the formation of intramolecular cross-linking. The cross-linked Snail molecule changes its conformation, due to which glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK3

While numerous hypotheses suggested that secreted lysyl oxidases play critical roles in the formation of the pre-metastatic niche and in promoting distant metastasis, providing definitive proof has been challenging. Nonetheless, there is compelling evidence indicating that LOX secreted by normal tissues may facilitate the acquisition of more aggressive phenotypes by tumor cells. For example, adipose tissue, which expresses high levels of LOX, can secrete the enzyme in certain experimental conditions, thereby promoting EMT of breast cancer cells [104]. In breast cancer, this supports the hypothesis that adipose tissue plays a critical role in the survival of BRCA-mutated breast cancer cells at specific stages of carcinogenesis [90]. However, the mechanisms regulating the response of breast cancer cells to lysyl oxidases are quite complex. Notably, in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), LOXL4 mediates an increase in annexin A2 levels on the cell surface through its cross-linking and multimerization [105]. This process also encapsulates a stable annexin A2-S100A11 complex, which functions as a plasminogen receptor, with the resulting plasmin promoting cell invasion [106]. Additionally, LOXL4 induces matrix metalloprotease 9 (MMP9) expression through the activation of nuclear factor-

At least in TNBC, the most widely recognized molecular mechanism underlying chemotherapy resistance involves hypoxia-induced LOX expression. This leads to two primary effects: increased collagen cross-linking and fibronectin assembly, resulting in reduced drug penetration; and elevated integrin subunit alpha 5 (ITGA5) and fibronectin 1 (FN1) expression, which together enhance FAK/Src signaling, reduce apoptosis, and contribute to chemoresistance. Additionally, hypoxia-induced repression of miR-142-3p has been implicated in these complex regulatory pathways [109]. However, whether LOX inhibition can effectively modulate FAK or Src signaling to overcome chemoresistance remains an open question. In human chondrosarcoma cells, LOX promotes cell migration, likely in coordination with nerve growth factor, suggesting a cooperative interaction between the two factors [110].

Combinations of chemotherapy and LOXL3 activity can be unfavorable in some experiments. A multistep regulatory mechanism has been proposed: chemotherapy-activated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling promotes the interaction between LOXL3 and TOM20, resulting in the sequestration of LOXL3 in the mitochondria. Within the mitochondria, LOXL3 is phosphorylated at S704 by the metabolic enzyme adenylate kinase 2. The phosphorylated LOXL3-S704 stabilizes dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH), preventing its ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation. The resulting accumulation of DHODH suppresses chemotherapy-induced mitochondrial ferroptosis [82].

It has long been known that bleomycin induces upregulation of lysyl oxidase (LOX) in fibroblasts [111]. In cultured human fetal lung fibroblasts, this upregulation is also significant, suggesting that blocking lysyl oxidase activity during bleomycin treatment could be a reasonable approach [112].

Non-cell-autonomous regulatory factors have been underestimated in the past, but their study has now become a priority. A key consideration is that secreted lysyl oxidase can be expressed by various cell types, including T cells. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for managing side effects; for instance, chemotherapy with paclitaxel has been shown to induce rapid ECM remodeling and increase LOX activity. This effect appears to be mediated by CD8+ T cells expressing LOX. Therefore, targeting and inhibiting such lysyl oxidase activity could be particularly beneficial [113].

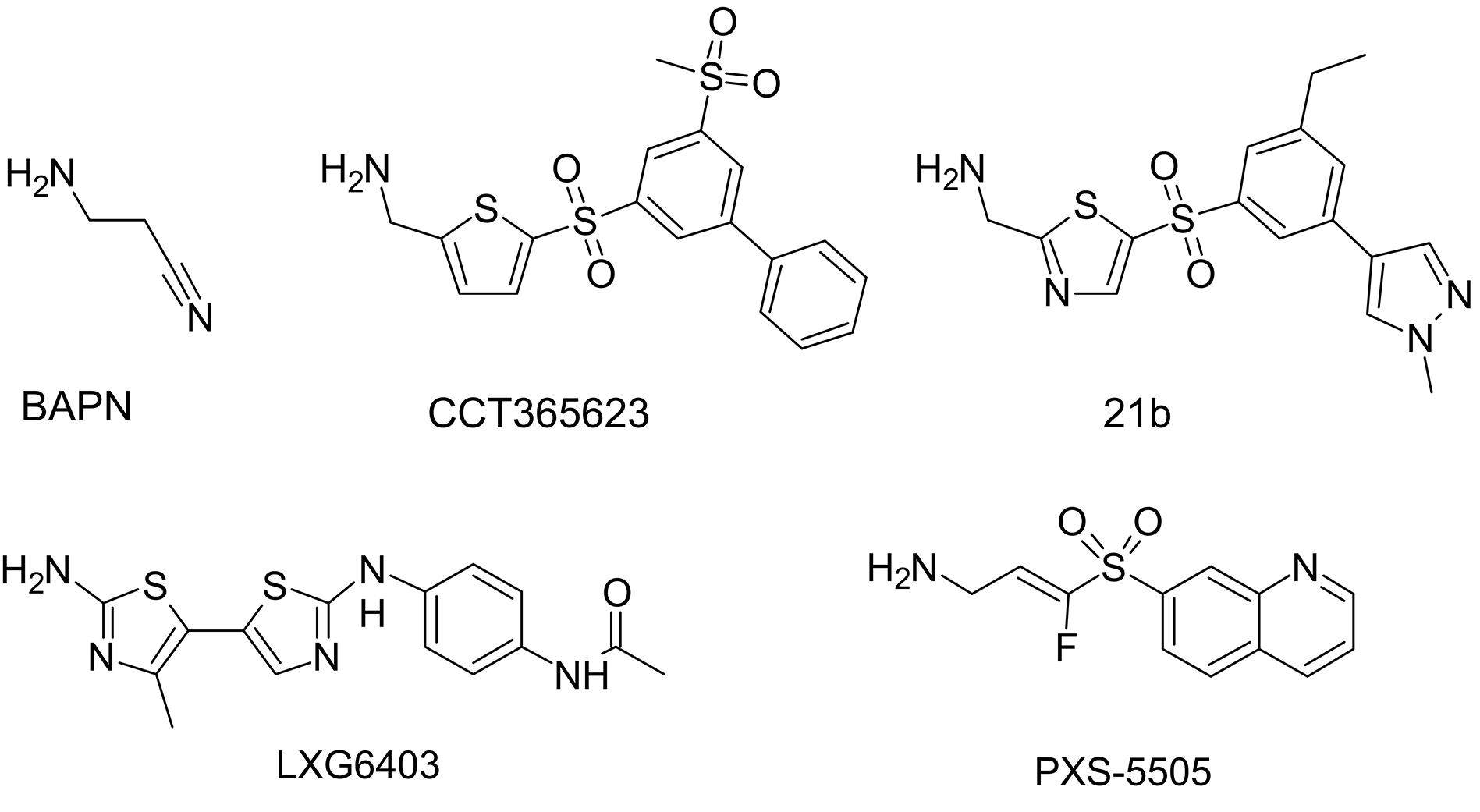

Significant interest and active participation of several pharmaceutical companies positively impacted the search for new inhibitors using high-throughput screening in conjunction with structure-function studies and yielded novel lysyl oxidase inhibitors (Fig. 8, Ref. [76, 114, 115, 116]) with submicromolar half-maximal inhibitory concentrations [117], including the highly selective oral bioavailable LOX inhibitor CCT365623 [114]. CCT365623 was found to inhibit the growth of primary and metastatic tumor cells by a molecular mechanism that involves disrupting the retention of EGFR on the cell surface [118]. Aminomethylenethiazoles (AMTz) are also of significant interest. The presence of a thiazole core enhances LOXL2 inhibition through irreversible binding, this achievement yielded dual LOX/LOXL2 inhibitors as well as selective LOXL2 inhibitors [115]. Moreover, more recent thiazole derivatives have shown even greater efficacy [116]. Recently, several exciting examples of experimental evaluation of lysyl oxidase inhibitors have been published. For instance, in mouse models of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, increased expression of all five lysyl oxidase isoforms was observed. Pan-lysyl oxidase inhibition was found to reduce tumor stiffness, which, by decreasing tumor compression, is believed to enhance the penetration of chemotherapeutic drugs. Additionally, this inhibition led to an increased release of damage-associated molecular patterns, activation of T-cell response, delayed tumor growth, and improved survival when combined with chemotherapy [119]. Among newly developed, highly selective, and potent pan-lysyl oxidase inhibitors stands PXS-5505. This compound has demonstrated the ability to reduce chemotherapy-induced pancreatic tumor desmoplasia and rigidity, decrease cancer cell invasion and metastasis, improve tumor perfusion, and enhance the overall efficacy of chemotherapy [76].

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. Structural formulae of notable lysyl oxidase inhibitors.

The prospects for a lysyl oxidase inhibitory intervention as a monotherapy in humans appear limited. In contrast, there are strong incentives and promising opportunities for discovering synergies with other drugs. For instance, in myelodysplastic neoplasms (MN), combining hypomethylating agents like 5-azacytidine (5-aza-CR) with the pan-lysyl oxidase inhibitor PXS-5505 has proven effective in restoring erythroid differentiation in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) of MN patients. This combination was effective in 20 out of 31 cases (65%) compared to 9 out of 31 cases (29%) treated with 5-aza-CR alone, particularly in cases of anemic MN [120]. Thus, the rationale for combining different therapeutic approaches is well-supported; to give one more example, silencing LOXL2 in pancreatic cancer cells has been shown to increase their sensitivity to gemcitabine [121].

However, in hepatocellular carcinoma, it has been reported that LOXL4 associated with p53 in the nucleus via the C-terminal basic domain of p53. 5-aza-CR, a genotoxic drug, induces LOXL4 upregulation, and this may even reactivate inactive p53, promoting cancer cell death [122]. Furthermore, the nude mouse xenograft model showed that the 5-aza-CR-dependent LOXL4-p53 axis reduces tumor growth with a positive correlation between LOXL4 expression and overall survival [122]. Thus, specifically concerning LOXL4, its action may be anti-cancer in certain contexts. Interestingly, there is a multi-layer complex interaction between LOXL4, p53, and its targets. For example, one of the transcriptional targets of p53, the orphan nuclear receptor NR4a [123], was shown to regulate the level of LOXL4 in pancreatic cells [124]. Therefore, any combination of lysyl oxidase inhibitors with other anti-cancer therapies should be critically evaluated and tested so that the sum of these effects would be beneficial to the patients.

Our opinion is that the main prospect is open for drugs that do not inhibit the activity of lysyl oxidase isoforms per se, but block the formation of LTQ in newly synthesized lysyl oxidase protein molecules. Therefore, any drug that reduces the rate of LTQ formation in specific lysyl oxidase isoforms could potentially convert these enzymes into beneficial agents for cancer treatment [105]. LOXL4, in particular, promotes breast cancer progression through its enzymatic activity targeting annexin A2 on the cell surface, but, rather interestingly, LOXL4 without the LTQ cofactor exhibits antimetastatic properties. Therefore, the best drug should not only inhibit lysyl oxidase activity but rather reduce the rate of LTQ formation in specific isoforms. Recall again that inhibition of ATP7A suppresses LOX activity in the 4T1 breast carcinoma cell line, which led to suppression of LOX-dependent metastasis mechanisms, including phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase and recruitment of myeloid cells to the lungs, in an orthotopic mouse model of breast cancer and Lewis lung carcinoma in mice [29]. Of course, the idea of blocking ATP7A together with lysyl oxidase for the therapy of malignant neoplasms does not look too promising [25].

A strategy of mildly inhibiting lysyl oxidases, not by targeting the enzymes directly but by modifying the substrates to be cross-linked, such as ECM proteins has been proposed [125]. Newly synthesized ECM chains, which undergo maturation and stiffening, could be rendered more resistant to oxidative deamination through dietary supplementation with modified lysine. For example, 6,6-dideuterated lysine would be sufficient to enhance resistance to lysyl oxidases associated with cancer cells [125]. It is also noteworthy that lysine deuterated with heavy hydrogen isotopes exhibits no toxicity, primarily because only small amounts of deuterium are incorporated. Experimental evidence indicates that the use of deuterated lysine in reactions with lysyl oxidase does not completely inhibit the enzyme, allowing metabolic processes to continue at some level [125]. Thus, this form of lysine may be valuable in situations where complete inhibition of lysyl oxidase is undesirable. Of course, any applications in humans would face serious obstacles in terms of the cost of such a diet with the dideuterated lysine, since these in vivo isotope effects are expected to become visible only at high substitution ratios, as was the case with another dideuterated lysine in a living animal [126].

It is plausible that potential inhibitors of LTQ formation could be discovered in plants, as they are rich in flavones that can interfere with oxidation processes. There is a rationale for this hypothesis, as some plants may utilize these compounds to inhibit the lysyl oxidases of insect pests. Notably, the first broad-spectrum lysyl oxidase inhibitor, BAPN, was originally discovered in a plant. Therefore, several additional lines of research on novel ways to inhibit excess lysyl oxidase should be pursued.

Despite certain challenges, including the retraction of papers from highly influential journals, the concept of targeting LTQ-containing lysyl oxidase for anti-cancer therapy remains highly promising. Recent advancements suggest that lysyl oxidase inhibitors are likely to play a key role in combination therapy regimens against highly lethal malignancies, such as PDAC. However, carefully designed clinical trials are crucial to avoid both false-positive and false-negative results. A promising future direction for lysyl oxidase inhibitors in cancer therapy may lie in substances that specifically inhibit LTQ formation during lysyl oxidase maturation.

5-aza-CR, 5-azacytidine; AOC, amine oxidase copper containing; BAPN,

TVK prepared figures. TVK, NBP and NAB designed the paper. TVK, NBP wrote the paper. NAB wrote p53 section. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Authors are grateful to I.A. Okkelman for her inspirational influence during early stages of the work.

This work was supported by Russian Science Foundation 22-14-00234 (to TVK).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.