1 The First Clinical Medical College of Guangdong Medical University, 524000 Zhanjiang, Guangdong, China

2 Department of Endocrinology, The First People’s Hospital of Foshan, 528000 Foshan, Guangdong, China

Abstract

As the global population ages, the risks associated with primary sarcopenia, including falls, fractures, functional decline, and frailty, are becoming increasingly apparent, all of which significantly impair the quality of life in older adults. Emerging evidence suggests that the gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in maintaining muscle physiology. Specific gut bacteria promote intramuscular protein synthesis through the production of certain amino acids (e.g., leucine, tryptophan), short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and hydrogen sulfide. Notably, Escherichia coli expressing the enzyme nicotinamidase (PncA) has been shown to enhance nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) synthesis, potentially improving mitochondrial function in muscle tissue. Furthermore, secondary bile acids and lactate influence the levels of fibroblast growth factor 15/19 and unacylated ghrelin in circulation by binding to receptors that are highly expressed in gut endocrine cells, thereby affecting muscle physiology. This review examines the characteristic composition of the gut microbiota in patients with sarcopenia, its role in primary sarcopenia, and potential therapeutic targets.

Keywords

- sarcopenia

- gut microbiota

- SCFAs

- bile acids

- NAD+

- ghrelin

- LPS

Sarcopenia affects 10% to 16% of the elderly population worldwide [1]. As the global population ages, age-related diseases, particularly sarcopenia, have garnered significant attention. Sarcopenia not only increases the risk of falls and fractures in older adults but also contributes to multi-organ dysfunction, imposing a substantial burden on patients, families, and society. In 1989, Irwin H. Rosenberg [2] first introduced the concept of sarcopenia, highlighting its characteristics of age-related muscle loss and reduced physical function. In 2016, sarcopenia was officially listed as a diagnosis in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) [3]. In 2024, the Global Leadership Initiative on Sarcopenia (GLIS) defined sarcopenia as a systemic skeletal muscle disease with potential reversibility, characterized by the combined decline in muscle mass and strength, with prevalence increasing with age [4]. The primary parameters for diagnosing and assessing sarcopenia are muscle strength, muscle mass, and physical function, with diagnostic cut-off values varying across regions and ethnicities. In Asia, the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia 2 (AWGS2) criteria, proposed in 2019, are widely recognized as the authoritative diagnostic standard for sarcopenia [5], with specific cut-off values detailed in Table 1 (Ref. [5, 6]).

| Classification | Detection method | Muscle mass | Muscle strength | Physical performance |

| EWGSOP2 [6] | DXA | ASM/height2 (kg/m2): Men | Grip strength (kg): Men | Gait speed (m/s): |

| AWGS2 [5] | BIA | ASM/height2 (kg/m2): Men | Grip strength (kg): Men | Gait speed (m/s): |

| DXA | ASM/height2 (kg/m2): Men |

ASM, appendicular skeletal muscle mass; EWGSOP, European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People; AWGS, Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; SPPB, short physical performance battery.

Sarcopenia can be classified as “primary” or “secondary” based on its etiology, with secondary sarcopenia associated with other diseases, whereas aging is considered the sole cause of primary sarcopenia [7]. The pathogenesis of sarcopenia is multifaceted. To initiate movement, the brain generates motor intent, and neural impulses are transmitted through motor neurons to the neuromuscular junction, triggering muscle contraction via the excitation-contraction coupling system [8], with skeletal muscle playing the primary role in movement. Skeletal muscle consists of muscle fibers, which contain mitochondria that are responsible for energy production. Muscle fibers are surrounded by a dense capillary network that provides oxygen and nutrients, while the extracellular matrix (ECM) tightly encases the fibers, housing satellite cells that repair muscle damage [9]. Muscle fiber contraction requires energy, and based on energy production pathways, fibers are classified as type I and type II. Type I fibers derive energy from lipid oxidation, and are resistant to fatigue, while type II fibers rely on glycolysis, and are more prone to fatigue, but generate higher force more rapidly [8]. As a plastic organ, skeletal muscle undergoes age-related changes, including protein homeostasis imbalance, fiber-type shifting from type I to type II, reduced vascular supply, chronic low-grade systemic inflammation, and ECM fibrosis, all of which contribute to the development of sarcopenia [10]. A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis identified several risk factors for primary sarcopenia, including lack of physical activity, malnutrition, smoking, insufficient or excessive sleep, diabetes, osteoporosis, and obesity [1]. Currently, treatment for primary sarcopenia primarily focuses on exercise and nutritional support; however, significant unmet needs remain, prompting further exploration of potential therapeutic targets.

The gut microbiota, often referred to as the “central metabolic organ”, weighs approximately 1.5–2.0 kg and contains approximately 100 trillion cells, ten times more than the human body’s own cells [11]. A healthy gut microbiota produces a variety of bioactive metabolites that enter the bloodstream via the enterohepatic circulation, exerting beneficial effects on the host. Furthermore, a healthy gut microbiota ferments indigestible polysaccharides to produce compounds such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which help suppress local intestinal inflammation and enhance gut barrier function [12]. Maintaining a balanced gut microbiota is essential for overall health. Recent studies have highlighted a close association between dysbiosis and several high-risk factors for sarcopenia. For instance, smoking has been linked to a reduction in Bifidobacteria levels and SCFA production [13], and human gut microbiota diversity is negatively correlated with sedentary behavior [14]. The gut microbiota also influences energy metabolism by regulating appetite and affecting the development and function of adipose tissue, which is closely related to obesity [15]. Moreover, gut microbiota has been identified as a potential target for addressing sleep disorders [16, 17], suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target for sarcopenia. Indeed, numerous studies have demonstrated that various gut metabolites are closely linked to the onset and progression of sarcopenia [18, 19],

The treatment of primary sarcopenia still has significant gaps, and further exploration of potential therapeutic targets for this condition is needed. In recent years, the role of gut microbiota metabolites in the body has garnered increasing attention. While the relationship between gut microbiota and sarcopenia has been explored previously, we note that metabolites closely associated with gut microbiota—such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), nonacylated growth hormone-releasing peptide, hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and Streptococcal quorum sensing peptide competence stimulating peptide 7 (CSP-7)—have not been widely discussed, despite their importance. This review will adopt a structured search strategy, aiming to describe and analyze current research to provide deeper insights into this emerging topic.

(1) Explore the characteristic intestinal flora profile of patients with primary sarcopenia.

(2) Explore the potential association between gut microbiota and the pathogenesis of sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity.

(3) Explore practical strategies based on microbial therapies.

The PubMed database (date last accessed 25 December 2024) was selected. The following keywords were used in the search strategy: (microbiota* OR microbiome* OR gut) AND (sarcopen*). Reference lists of related reviews were searched for additional studies.

(1) Clinical original studies (Last 5 years; Patients were included according to recognized diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia).

(2) Preclinical studies (Last 1 years).

(3) Study on gut microbiota and its effects on sarcopenia.

(4) Study reporting muscle mass and function indicators.

(1) Review articles.

(2) Conference and abstract publications.

(3) Study not involving the gut microbiota or sarcopenia.

(4) Athletes and patients/animal models with other diseases rather than age-related sarcopenia.

(5) Lack of baseline characteristics data.

(6) Non-English article.

Screened titles and abstracts of articles obtained through the search strategy followed by full text for eligible criteria independently.

The following data were extracted from pre-clinical studies: doi, published year, animal model, intervention, endpoints, muscle samples, sample type and detection, muscle measurement method, physical performance method, muscle mass comparison, physical performance comparison, gut microbiota, relationship: muscle/functions and gut microbiota, key findings. For clinical studies, the extracted data were: doi, published year, subject, study group, age (year), study type, follow-up duration, sample type and detection, muscle measurement method, physical performance method, diagnostic criteria, muscle mass comparison, physical performance comparison, gut microbiota, function of the fecal microbiota, relationship: muscle/functions and gut microbiota, key findings.

A total of 413 studies were retrieved through electronic database searches. We initially excluded review articles, conference and abstract publications, and editorials by adjusting the search format. A total 214 studies were identified for title and abstract screening. Among these studies, 112 full texts were reviewed, and 24 studies (seven pre-clinical trials and seventeen clinical trials) satisfied all inclusion and exclusion criteria. It should be known that although we reviewed the last 5 years of pre-clinical studies according to the search strategy, we only selected reports from the last 1 year to list in the table. Supporting information, Supplementary Table 1 shows the summary of clinical studies, and Supplementary Table 2 shows the pre-clinical studies.

There were seventeen clinical studies of which fifteen were observational studies [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34] and two were interventional studies [35, 36]. All studies used recognized diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia, of which nine studies [21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 34, 36] used AWGS2 (2019) criteria, two studies [30, 31] used AWGS (2014) criteria, two studies [33, 35] used EWGSOP2 (2018) criteria. Two studies [20, 29] used EWGSOP (2010) criteria, one study [32] used Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) criteria, and one study [23] used International Working Group on Sarcopenia (IWGS) criteria. Please refer to Supplementary Table 1.

Roseburia and Eubacterium were significantly positively correlated with appendicular skeletal muscle mass index (ASMI) (p

There were seven interventional animal studies [39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45]. A total of six studies were mice using Dexamethasone (DEX)-induced sarcopenia mouse model in two [44, 45], BALB/c in one [41], C57BL/6J in two [42, 43], and SAMP8 in one [40]. The seven pre-clinical studies examined the effects of dietary, probiotics, prebiotics, short-chain fatty acids, and intestinal immune status on models of sarcopenia and its metabolic complications, and highlighted the potential role of intestinal flora. Please refer to Supplementary Table 1.

Mo et al. [39] investigated whether a high-fat diet (HFD) causes sarcopenic obesity (SO) in natural aging animal models and specific microbial metabolites that are involved in linking HFD and SO. The results show that HFD caused decreases in muscle mass, strength, function, and fiber cross-sectional area and increase in muscle fatty infiltration in natural aging rats, which also contributed to gut dysbiosis, mainly characterized by increases in deleterious bacteria (such as Parabacteroides, Akkermansia, Intestinimonas, and Butyricimonas) and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) [39]. Particularly, supplementation with Akkermansia or Butyricimonas effectively mitigated sarcopenic obesity by restoring gut dysbiosis to homeostasis and decreasing systemic inflammation [46, 47]. Further study indicated that TMAO promotes the development of HFD-induced SO via the reactive oxygen species (ROS)-protein kinase B (Akt)/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway [39]. Liu et al. [40] investigated whether the use of SCFAs as a supplement can be a therapeutic strategy for sarcopenia. The results show that increased muscle mass, myofiber cross-sectional area, grip strength, twitch, and tetanic force were found in SCFAs-treated mice compared with control SAMP8 mice, and in vitro studies indicated that SCFAs inhibited Forkhead box O3a (FoxO3a)/Atrogin1 and activated mTOR pathways to improve myotube growth [40]. Ma et al. [41] investigated the crosstalk between the intestinal microbiota and the host’s immunity and metabolism. The results show that the gut microbiota population structures altered with the subtherapeutic level of antibacterial agents facilitated growth phenotype in both piglets and infant mice, notably, increased colonization of Prevotella copri was observed in the intestinal microbiota, which shifted the immune balance from a CD4+ T cell-dominated population toward a T helper 2 cell (Th2) phenotype, accompanied by a significant elevation of interleukin-13 (IL-13) levels in the portal vein, which was found to display a strong positive correlation with hepatic insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) levels. Subsequent investigations showed that gut-derived IL-13 stimulated the production of hepatic IGF-1 by activating the interleukin-13 receptor (IL-13R)/Janus Kinase 2 (Jak2)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (Stat6) pathway in vitro. The IGF-1 levels were increased in the muscles, leading to an upregulation of and resulting in the increased genes associated with related to myofibrillar synthesis and differentiation, which ultimately improved the growth phenotype [41]. Zhang et al. [42] investigated the impact of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Probio-M8 (Probio-M8) on old mice and sarcopenia patients. The results show that Probio-M8 significantly improved muscle function in aged mice and enhanced physical performance in sarcopenia patients. It reduced pathogenic gut species (such as Romboutsia ilealis (human) and Intestinibacter bartlettii (human)) and increased beneficial metabolites such as indole-3-lactic acid, acetoacetic acid, and creatine [42]. Kim et al. [43] investigated the beneficial effects of L. paragasseri SBT2055 on obesity along with obese sarcopenia and gut microbiome changes. The results show that SBT2055 reduces adiposity in obese mice and enhances muscle mass and function in the context of sarcopenic obesity [43]. The anti-obesity efficacy of SBT2055 was due to increased lipid excretion into feces by reducing the mRNA levels of fatty acid binding protein 1 (Fabp1), fatty acid binding protein 2 (Fabp2), fatty acid transport protein 4 (Fatp4), cluster of differentiation 36 (Cd36), and apolipoprotein 48 (ApoB48) in the small intestine [43]. Two studies examine the effect of probiotics on skeletal muscle atrophy in dexamethasone-induced C2C12 cells and a mouse animal model [44, 45]. The results show that supplementation with Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus IDCC3201 resulted in significant enhancements in body composition, particularly in lean mass, muscle strength, and myofibril size. IDCC3201 increased the production of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and improved the Allobaculum genus within the gut microbiota of muscle atrophy-induced groups [44]. Another study showed that KL-Biome (Postbiotic Formulation of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum KM2) significantly downregulated the expression of genes (Atrogin-1 and muscle-specific RING finger protein 1 (MuRF-1)) associated with skeletal muscle degradation but increased the anabolic phosphorylation of FoxO3a, Akt, and mTOR in C2C12 cells. Furthermore, it significantly increased the relative abundances of the genera Subdoligranulum, Alistipes, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, which are substantially involved in short-chain fatty acid production [45].

To summarize, five of the studies involved the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway [39, 40, 43, 44, 45], and one study highlighted the modification of gut immunity states as a central strategy for increasing anabolism of the host, which has significant implications for addressing sarcopenia [41].

In 2022, a study explored the metabolism and community composition of gut contents and mucus in mice. It was found that compared to germ-free mice, specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice had an average concentration of 24 metabolites in the colon that was at least four times higher. This study also provided evidence of the microbial origin of 11 metabolites in the small intestine [48]. Many of these microbial-derived metabolites, such as nicotinamide, spermidine [49], deoxycholate [18], short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [50], histidine [51], and Indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) [52], have previously been linked to sarcopenia. Therefore, we will discuss the role of the gut microbiome and its metabolites in the development of sarcopenia, focusing on three aspects: protein homeostasis, systemic chronic low-grade inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, while exploring potential therapeutic targets within these pathways.

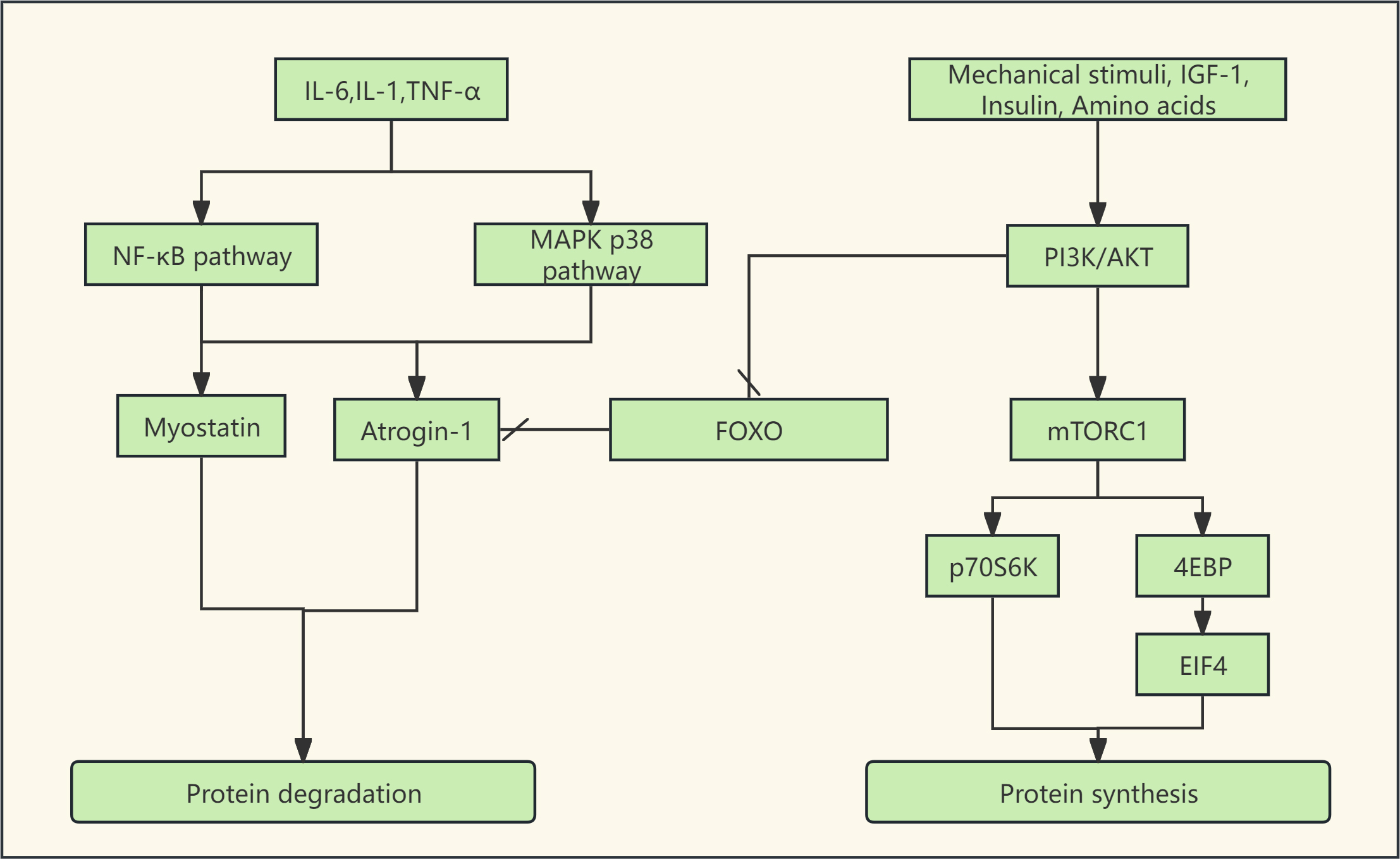

Protein homeostasis refers to the delicate balance between protein synthesis and degradation, which is closely linked to muscle fiber size [53]. A decline in protein homeostasis is a hallmark of aging [54]. The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) in mammals is a key regulator of muscle protein synthesis and metabolism. As shown in Fig. 1, in skeletal muscle, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway mediates protein synthesis and can be activated by mechanical stimuli, insulin-like growth factors, insulin, amino acids, and other factors [55, 56]. This pathway promotes muscle protein synthesis and hypertrophy through the following mechanisms [53]: (1) Activation of mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of p70S6 kinase, which promotes protein synthesis [57]. (2) Activation of mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein (4EBP), leading to its dissociation from eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), initiating translation and increasing protein synthesis [58]. (3) PI3K/Akt activation also prevents protein degradation in skeletal muscle by phosphorylating and thereby inactivating O-type fork head box (FOXO) transcription, which downregulates the expression of MuRF-1 and Atrogin-1, inhibiting protein degradation [53]. These processes are depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The Akt/mTOR-centered protein synthesis pathway and the main protein degradation pathways. (1) Factors such as mechanical stimuli, insulin-like growth factors, insulin, and amino acids can activate the PI3K/Akt pathway. This pathway can promote protein synthesis by activating mTORC1 and inhibit protein degradation by phosphorylating FOXO. (2) Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1, and TNF-

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-

Systemic chronic low-grade inflammation is a key feature of sarcopenia [62], characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory markers such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-13, IL-18, C-reactive protein (CRP), Interferon (IFN)

With aging, mitochondrial function progressively declines [67]. A quantitative proteomics analysis of skeletal muscle from 58 healthy individuals aged 20 to 87 revealed a marked reduction in proteins related to energy metabolism, including those involved in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, mitochondrial respiration, and glycolysis, as aging progresses [65]. This decline in mitochondrial function during aging disrupts protein homeostasis and leads to muscle atrophy.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is a critical coenzyme in cells, playing a vital role in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and oxidative phosphorylation, both of which are essential for maintaining mitochondrial function. Low NAD+ levels have been identified as a significant marker in patients with sarcopenia [68, 69]. In humans, NAD+ synthesis primarily occurs through two pathways: the salvage pathway and the de novo synthesis pathway: (1) Salvage Pathway: This pathway regenerates NAD+ from its breakdown product, nicotinamide (NAM). (2) De Novo Synthesis Pathway: Nicotinic acid (NA) synthesizes NAD+ through the Preiss-Handler pathway, while tryptophan is converted to nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) via the kynurenine pathway, which eventually integrates into the Preiss-Handler pathway for NAD+ synthesis [70].

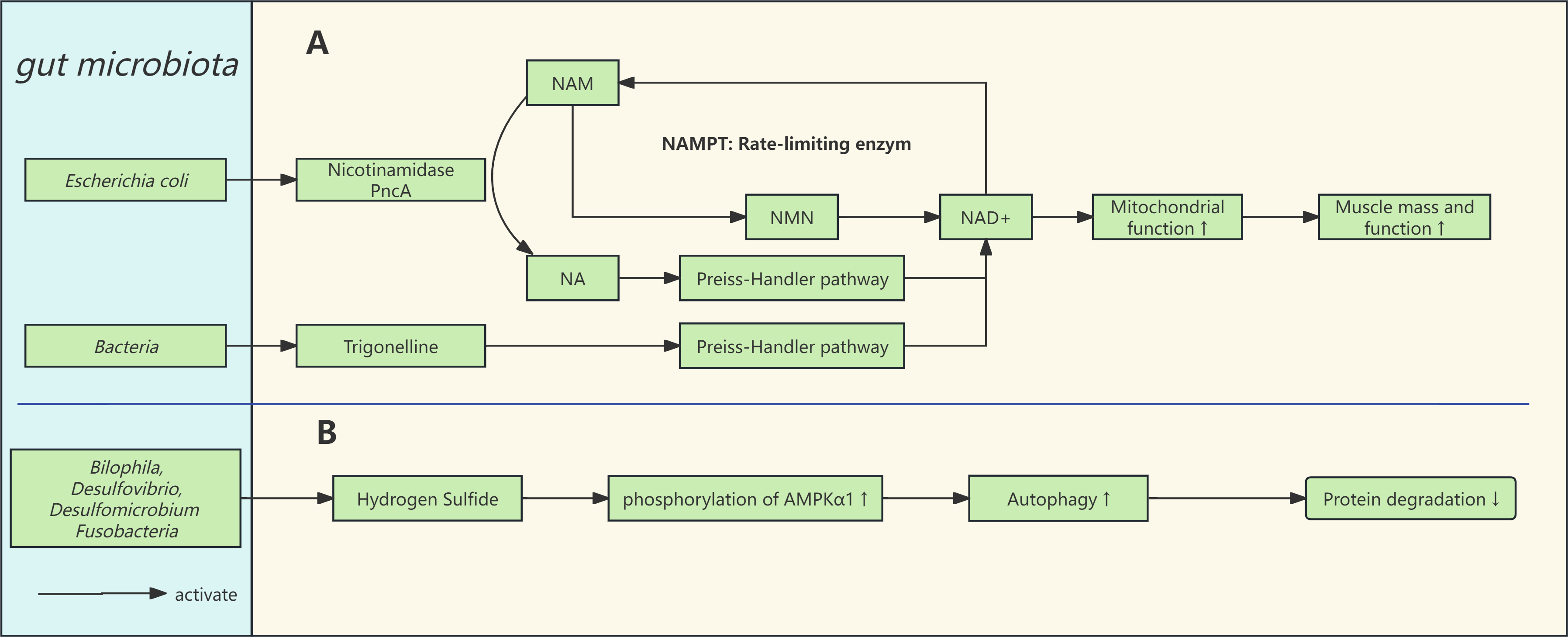

Among these, the NAD+ salvage pathway via NAM is the primary route in humans, forming a delicate cycle between NAD+ consumption and regeneration. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), the rate-limiting enzyme, converts NAM to NMN. As individuals age, the expression of NAMPT decreases, resulting in reduced NAD+ synthesis. The gut microbiome is closely associated with NAD+ homeostasis [71]. As illustrated in Fig. 2A, gut bacteria expressing nicotinamidase (PncA), such as Escherichia coli, can bypass the limitation of NAMPT, converting NAM into NA, which then generates NAD+ through the de novo synthesis pathway, thereby stabilizing NAD+ levels [71]. In one study [71], NAD+ precursors were administered to both microbiota-rich normal mice and antibiotic-treated mice via gavage. It was found that in normal mice, isotopically labeled NAM was rapidly converted to NA, whereas this conversion was significantly diminished or absent in antibiotic-treated mice. Further investigation revealed that E. coli expressing nicotinamidase PncA could protect CRC119 cells from NAMPT inhibitors, reversing the decline in NAD+ levels. Notably, deletion of the PncA gene in E. coli completely eliminated this protective effect. Additionally, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) confirmed that E. coli stably converts NAM to NA in culture [71]. Other research similarly found that NAM is rapidly deaminated to NA by the microbiota, a process closely associated with the abundance of gut microorganisms [72].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Gut microbiota and the pathways associated with mitochondria and autophagy. (A) The NAD+ salvage pathway is the primary source of NAD+ in the body and is limited by the enzyme NAMPT. Gut microbiota can convert NAM to NA through nicotinamidase (PncA), bypassing the NAMPT restriction to promote NAD+ homeostasis in the body. (B) Hydrogen sulfide and lipopolysaccharides are involved in skeletal muscle metabolism. Abbreviations: NA, nicotinic acid (Niacin); NAM, nicotinamide; NMN, nicotinamide mononucleotide; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NAMPT, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase; AMPK

Furthermore, the gut microbiome can produce NAD+ precursors such as trigonelline and NA [48, 73, 74]. One study found that supplementing with fenugreek alkaloids improved NAD+ levels in Caenorhabditis elegans, mice, and primary myotubes (derived from both healthy individuals and those with sarcopenia) (Fig. 2A). It also enhanced mitochondrial respiration and biosynthesis, while reducing age-related muscle loss [74]. Another study investigated the clinical application of NAD+ precursors with 20 pairs of identical twins. Over five months, they gradually increased nicotinamide riboside (NR, an NAD+ precursor) supplementation from 250 mg/day to 1000 mg/day to examine its impact on mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolic health. Results indicated that NR supplementation enhanced mitochondrial presence in type I muscle fibers by approximately 14%, expanded mitochondrial coverage within muscle fibers, and significantly increased mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) by around 30%. These effects were linked to the upregulation of genes such as SIRT1, ERR

While the gut microbiome has demonstrated potential in maintaining NAD+ homeostasis and mitigating sarcopenia in animal models, particularly through bacterial strains expressing nicotinamidase PncA, these findings should be interpreted with caution. The direct applicability of these results to human health remains to be validated through clinical trials.

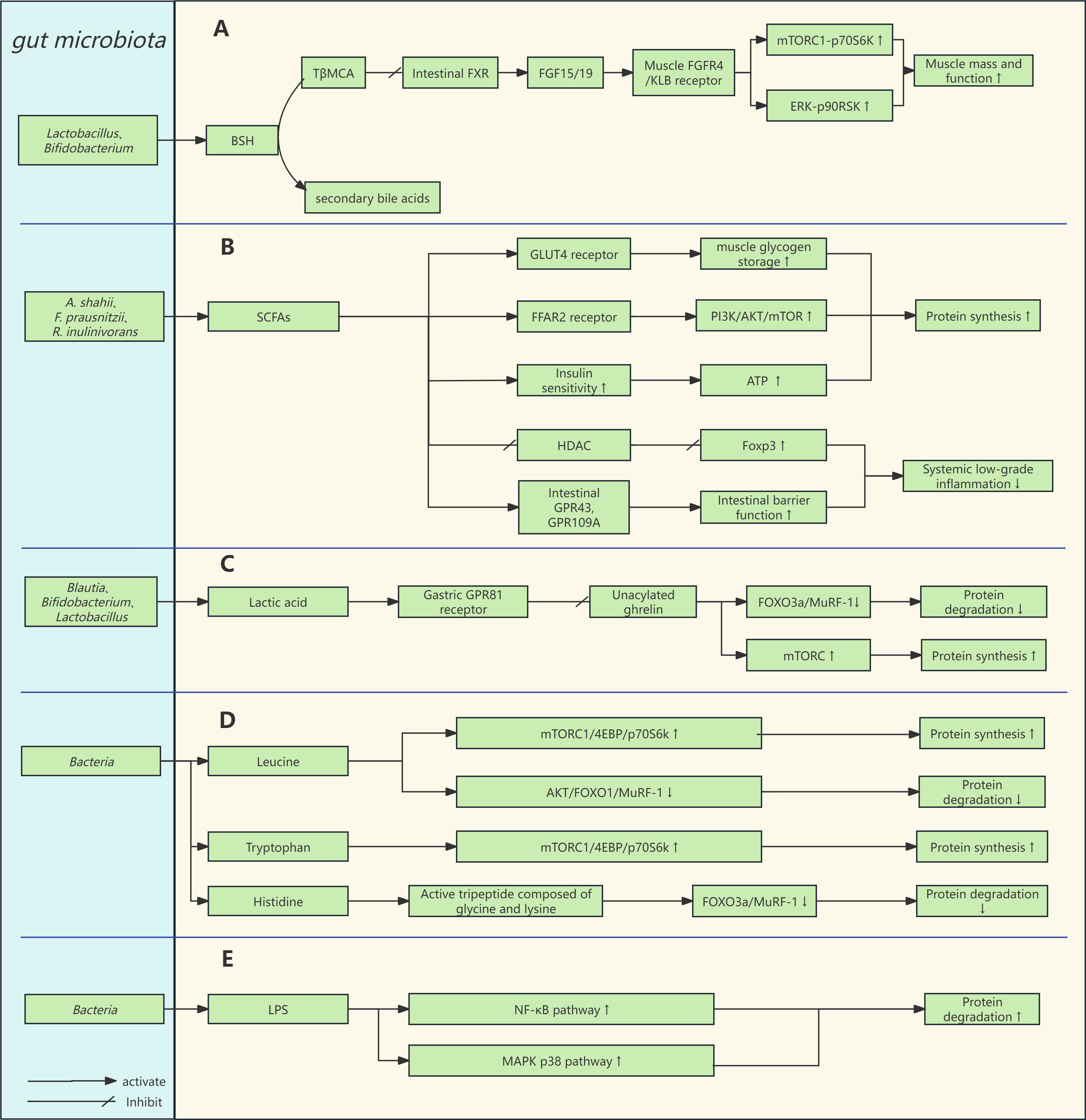

Research suggests that the gut microbiota can influence the Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) by modulating the bile acid pool, which subsequently affects muscle protein homeostasis through the fibroblast growth factor (FGF)15/19/fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)4/klotho beta (KLB)/mTORC1 signaling pathway, playing a role in the onset and progression of sarcopenia [18, 76]. The bile acid pool comprises primary and secondary bile acids, which regulate bile acid circulation and various host metabolic processes via FXR activation [18]. FGF15/19 (the mouse and human homologs of FGF15 and FGF19, respectively) are induced by FXR [77] and influence skeletal muscle protein synthesis [76]. Different bile acids exert varying agonist effects on FXR, in the following order: chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA)

Qiu et al. [76] found that antibiotic-treated mice exhibited a characteristic bile acid profile dominated by the accumulation of the FXR antagonist T

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Gut microbiota and signaling pathways for muscle protein synthesis and degradation. (A) Gut microbiota can indirectly regulate circulating FGF15/19 levels by influencing bile acid metabolism, thereby participating in skeletal muscle metabolism. (B,D,E) SCFAs, amino acids, and lipopolysaccharides are involved in skeletal muscle metabolism. (C) Intestinal lactate affects the level of circulating unacylated ghrelin by binding to receptors on intestinal endocrine cells, thus influencing muscle protein metabolism. Abbreviations: T

Clinical study has demonstrated that the FGF19 signaling pathway is downregulated in elderly men (

Indigestible substrates in the gut, such as dietary fiber, are fermented by gut bacteria (e.g., A. shahii, F. prausnitzii, R. inulinivorans) to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, propionate, butyrate, and pentanoate. Approximately 95% of SCFAs are rapidly absorbed in the colon, where they act through the FFAR3 (G protein-coupled receptor (GPR)41) and FFAR2 (GPR43) receptors, which are closely associated with the development of sarcopenia [50, 81, 82].

As illustrated in Fig. 3B, Tang et al. [19] found that butyrate upregulates the PI3K/Akt/mTOR1 signaling pathway via the FFAR2 receptor, providing protection against muscle atrophy. The study established FFAR2-overexpressing C2C12 myoblasts and an FFAR2 gene silencing group as a control. It was found that FFAR2 overexpression significantly upregulated the expression of p-PI3K, p-Akt, and p-mTOR, whereas no such effects were observed in the FFAR2 gene silencing group. Moreover, the researchers observed that butyrate alleviated atrophy in C2C12 myoblasts induced by high glucose and lipopolysaccharides (LPS), but no such protective effects were noted in the FFAR2 gene silencing group [19].

Additionally, Luo et al. [83] discovered that pentanoate significantly upregulated the expression of FFAR2, myogenic differentiation 1 (MyoD) and myogenin. Pentanoate also promoted the transition of oxidative muscle fibers (Type I) to glycolytic muscle fibers (Type II) by activating the Akt/mTOR1 pathway, thereby benefiting sarcopenia [83]. Propionate has been linked to enhanced exercise performance. Scheiman et al. [84] observed that lactate produced during exercise enters the gut, where it is metabolized by Veillonella in the colon to propionate. Propionate then enters the bloodstream and serves as an energy source for other metabolic organs, improving exercise performance in mice [84].

In clinical study, SCFA intake has been negatively correlated with muscle strength loss over a 7.8-year follow-up period among 823 elderly individuals aged 60–87 [85]. Lv et al. [47] found that in healthy postmenopausal women, F. prausnitzii was positively correlated with butyrate synthesis and skeletal muscle mass index. Mendelian randomization analysis suggested a causal relationship between SCFAs and appendicular lean mass [47]. Moreover, supplementing sarcopenic mice with puerarin increased the abundance of SCFA-producing Peptococcaceae and Clostridiales in the gut, and a linear relationship was observed between total SCFAs and skeletal muscle strength [86].

As illustrated in Fig. 3B, study has shown that SCFAs improve glycogen storage capacity by increasing the expression of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) in skeletal muscle, thereby enhancing glucose uptake and glycogen resynthesis. SCFAs also increase the capacity of skeletal muscle to obtain energy by promoting lipid uptake and oxidation, enhancing glucose uptake, and increasing glycogen synthesis rates [81].

SCFAs regulate systemic inflammation through the following pathways: (1) Activation of GPR43 and GPR109A receptors in intestinal epithelial cells enhances gut barrier function and prevents the translocation of LPS into the bloodstream (Fig. 3B). LPS in circulation can bind to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on immune cells, upregulating the NF-

SCFAs are closely linked to insulin sensitivity. A meta-analysis has shown that SCFA intervention groups had significantly lower fasting insulin levels compared to placebo groups. Moreover, fasting insulin and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) values significantly improved from baseline in SCFA intervention groups [90]. Insulin regulates muscle function by modulating glucose metabolism. When insulin acts on muscle cells, it recruits GLUT4 transporters to the cell surface, facilitating glucose transport into the muscle. Phosphate, a key component of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), enters the cell via sodium-phosphate cotransporters and participates in ATP synthesis. Insulin plays a crucial role in phosphate transport [91]. Reduced insulin sensitivity in muscle fibers decreases intramuscular phosphate, activating adenosine monophosphate deaminase 1 (AMPD1) and accelerating phosphate depletion. This depletion further reduces AMPD1 inhibition, leading to adenosine monophosphate (AMP) conversion to inosine monophosphate (IMP), thus accelerating phosphate skeleton depletion and creating a vicious cycle [92]. SCFAs may help prevent sarcopenia by enhancing insulin sensitivity and promoting ATP synthesis in muscles.

Human skeletal muscle expresses significant quantities of enzymes responsible for hydrogen sulfide (H2S) production, including cystathionine

The gut hosts a large population of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), including Bilophila, Desulfovibrio, Desulfomicrobium, and Fusobacteria, which metabolize organic sulfur compounds from food (e.g., cysteine or taurine from red meat) to produce endogenous H2S [96]. A study analyzing the metagenomes of 195 centenarians revealed that the gut microbiota of these long-lived individuals exhibited enhanced sulfide transformation capabilities, such as the conversion of methionine to homocysteine and the reduction of sulfate and taurine to sulfides [97]. This suggests that the gut microbiota may serve as a potential therapeutic target. However, H2S in the gut can be a double-edged sword, carrying potential risks. Research has shown that at certain concentrations, H2S can promote energy metabolism, proliferation, and migration of colorectal cancer cells [98]. The effects of H2S are complex, and further studies are necessary to elucidate its mechanisms and provide more precise guidance for interventions targeting sarcopenia.

Ghrelin is a peptide hormone primarily produced by enteroendocrine cells in the stomach [99]. It exists in two forms: acylated ghrelin (AG) and unacylated ghrelin (UnAG, also known as des-acyl ghrelin) [100]. AG binds to the GHSR1a receptor in the pituitary gland, stimulating growth hormone secretion, promoting appetite, and influencing metabolism, which is why it is commonly referred to as the “hunger hormone”. In contrast, UnAG is the predominant form of ghrelin in circulation (90%–95%) [101]. While UnAG does not act on the pituitary gland as AG does, recent studies have highlighted its beneficial effects in combating sarcopenia. Kim et al. [101] divided four-month-old and eighteen-month-old mice into control and UnAG treatment groups, and after 10 months, analyzed their skeletal muscle strength, mass, mitochondrial respiration capacity, protein synthesis, and downstream pathways. The results confirmed that UnAG directly alleviated sarcopenia in mice, independent of food intake or body weight. Specifically, UnAG improves mitochondrial respiration and protects against NMJ disruption in aged mice, upregulating mTOR expression and downregulating MuRF-1 expression, thereby influencing protein synthesis and degradation [101]. Other studies have also observed UnAG’s beneficial effects on muscle, including the improvement of mitochondrial dysfunction, redox balance, and targeting mitochondrial apoptosis within neurons [102, 103, 104]. Ranjit et al. [105] found UnAG’s downstream effects in skeletal muscle, discovering increased phosphorylation of FoxO3a at Ser253, which leads to downregulation of the FoxO3a-MuRF-1 pathway and inhibition of protein degradation. However, these findings do not fully explain UnAG’s enhancement of muscle strength, and Ranjit et al. [105] speculated that calcium release and sensitivity might play a key role, as these are essential for excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle.

Changes in the gut microbiota can influence the levels of ghrelin in the bloodstream [106]. Bo et al. [107] found a positive correlation between Ruminococcus and serum UnAG levels, suggesting that ghrelin may serve as a critical hormone transmitting essential signals along the gut-muscle axis. Martín-Núñez et al. [108] discovered that after Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy, circulating total ghrelin levels (including both AG and UnAG) were significantly reduced. They speculated that this reduction was due to the high expression of the lactate-specific receptor GPR81 on ghrelin-producing cells in the stomach. Lactate binds to this receptor and dose-dependently inhibits ghrelin secretion [109]. Long-term antibiotic treatment can disrupt the balance between lactate producers (e.g., Blautia) and consumers (e.g., Megasphaera, Lachnospiraceae, and Prevotella) in the gut, leading to changes in circulating ghrelin levels [108].

Clinical studies also support the influence of the gut microbiota on ghrelin. Sempach et al. [110] studied the effects of probiotics on circulating ghrelin levels in 43 patients with depression (19 received probiotics, and the rest were in the placebo group). After four weeks of intervention, blood tests showed a significant increase in ghrelin levels in the probiotic group compared to baseline [110]. Similarly, Wu et al. [111] found that supplementation with Lacticaseibacillus paracasei PS23 increased circulating ghrelin levels compared to the control group.

Therefore, as illustrated in Fig. 3C, gut microbiome metabolites may influence serum UnAG levels by binding to receptors on ghrelin-producing cells, thereby contributing to the prevention of sarcopenia through mechanisms such as upregulating mTOR expression and downregulating MuRF-1 expression. For instance, tryptophan can stimulate the secretion of ghrelin via the GPR142 receptor, while long-chain fatty acids can inhibit ghrelin secretion through the GPR120 receptor [109]. While these receptors show promise as therapeutic targets for sarcopenia in animal models, it is crucial to validate these findings through further clinical studies.

Research has shown that the gut microbiota can synthesize amino acids de novo, including branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) [112], tryptophan [113], and histidine [48]. These amino acids play a positive role in skeletal muscle health and contribute to the prevention of sarcopenia. Studies have identified Prevotella copri and Bacteroides vulgatus as strong producers of BCAAs [114]. Leucine, a key branched-chain amino acid, can relieve the inhibitory effect of Sestrin2 on Gap Activity Towards Rags 2 (GATOR2) by competitively binding to Sestrin2. GATOR2, a complex of unknown function, acts as a positive regulator of mTORC1 [115]. Consequently, leucine promotes protein synthesis through the mTORC1/4EBP/p70S6K signaling pathway. Furthermore, leucine activates the Akt pathway to phosphorylate FOXO1, preventing its translocation to the nucleus, which lowers nuclear FOXO1 levels, downregulates MuRF-1 expression, and inhibits muscle atrophy [58], the mechanism of action of leucine can be referred to in Fig. 3D. Clinical study has demonstrated that increasing leucine intake can enhance myofibrillar protein synthesis in elderly women [116]. Additionally, supplementation with tryptophan has been shown to increase skeletal muscle mass in mice on a low-protein diet by raising IGF-1 levels in muscle tissue and upregulating the mTOR1/p70S6K pathway, thus promoting protein synthesis [117] (Fig. 3D). Therefore, amino acids derived from the gut microbiota can influence protein synthesis and degradation through the mTORC1 axis.

Histidine, an essential amino acid, has recently been shown to have a microbial origin [48]. It is a crucial component of the bioactive tripeptide Glycyl-L-Histidyl-L-Lysine (GHK), particularly in its copper-bound form, GHK-Cu. Studies have demonstrated that GHK-Cu can alleviate C2C12 myotube skeletal muscle dysfunction induced by cigarette smoke extract (CSE) and protect mice from CSE-induced muscle dysfunction. The underlying mechanisms include: (1) GHK-Cu activates SIRT1 deacetylase activity, which downregulates the FOXO3a/MuRF-1/Atrogin-1 pathway (Fig. 3D), thereby reducing protein degradation; (2) SIRT1 modulates Nrf2 through deacetylation, enhancing the production of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzymes to reduce ROS generation; (3) SIRT1 also increases the expression of PGC-1

Research has indicated that alterations in gut barrier function may play a pivotal role in regulating both intestinal and extraintestinal inflammation [19, 118, 119]. When the gut barrier is compromised, harmful microbial metabolites such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) can translocate into the bloodstream. As illustrated in Fig. 3E, these metabolites activate the NF-

Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, representative heterolactic bacteria, produce lactate through the fermentation of indigestible carbohydrates. Once produced in the gut, lactate can enter the systemic circulation and serve as an energy source for skeletal muscle. It can also be metabolized by bacteria such as Anaerostipes caccae and Eubacterium hallii to generate acetyl-CoA and butyrate. Butyrate provides energy to colonic cells and enhances gut barrier function [81]. The significant role of butyrate in preventing sarcopenia has been discussed earlier.

Clostridium sporogenes, a beneficial gut bacterium, metabolizes tryptophan to produce the anti-inflammatory metabolite indole-3-propionic acid (IPA). IPA promotes the proliferation of C2C12 muscle cells through activation of the myogenic regulatory factor (MRF) signaling pathway and alleviates myotube inflammation via the IPA/miR-26a-2-3p/IL-1

Recent research has linked trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) to increased intestinal permeability, systemic inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, all of which are associated with the progression of sarcopenia [48, 123, 124]. TMAO intervention studies indicated that TMAO promotes the development of HFD-induced SO via the ROS-Akt/mTOR pathway [39].

Recent research has demonstrated that CSP-7 selectively stimulates the production of IL-6 in muscle cells, has the capability to enter the human systemic circulation, and induces a muscle-wasting phenotype in a preclinical mouse model [125]. Sundin et al. [126] identified substantial numbers of Streptococcus mitis on the jejunal mucosa. The effects of CSP-7 quorum sensing peptide, produced by streptococci strains, on skeletal muscle creates new diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities.

Different from simple obesity, sarcopenic obesity refers to a pathological condition characterized by decreased skeletal muscle mass and function accompanied by excessive fat accumulation [127]. A meta-analysis of 50 studies showed a prevalence of sarcopenic obesity of 11% among individuals aged

Both muscle and adipose tissue have endocrine functions and maintain the homeostasis of muscle and adipose tissue by secreting myokines and adipokines. Excessive free fatty acids can stimulate adipose tissue or infiltrate macrophages within it to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-

In 2022, a study explored the potential of propolis to improve sarcopenic obesity by altering gut microbiota. Using db/db mice to simulate sarcopenic obesity and db/m mice as controls, the study fed them a normal diet or propolis at different concentrations for 8 weeks and collected blood, feces, epididymal fat, and muscle tissue for analysis. The researchers observed significant improvements in muscle weight, grip strength, and epididymal fat weight in the db/db + 2% propolis group compared to the db/db group. Ruminococcaceae and Acetivibrio significantly increased in the db/m group and db/db + 2% propolis group. This study affirmed the positive impact of altered gut microbiota on sarcopenic obesity [133]. Another study found that transplantation of fecal matter from the Milk group can improve sarcopenia obesity in db/db mice [46]. Moreover. Lactobacillus paragasseri SBT2055 (LG2055) treatment has also been reported to reduce free fatty acids (FFA) in mice models of sarcopenia [43]

Several preclinical studies have reported positive effects of probiotic formulations in models of sarcopenia: Bifidobacterium bifidum and Lactobacillus paracasei can alleviate aging-dependent sarcopenia and cognitive impairment by regulating gut microbiota-mediated Akt, NF-

Several studies have reported the potential role of dietary fiber in preventing sarcopenia. The study by Montiel-Rojas et al. [137] showed a beneficial impact of dietary fiber intake on skeletal muscle mass in older adults. Fielding and Lustgarten [138] investigated the impact of a high-soluble-fiber diet (HSFD) on the gut-muscle axis. The results show that female (but not male) HSFD-fed mice had significant increases in SCFAs, the quadriceps/body weight (BW) ratio, and treadmill work performance (distance run

Studies have found that germ-free mice exhibit reduced skeletal muscle mass, while fecal transplantation (using feces from wild-type mice) can increase the muscle mass of germ-free mice [140]. In contrast, another study conducted fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from human donors into antibiotic-treated recipient mice to investigate the causal relationship between sarcopenia and the gut microbiome. The results revealed that mice receiving microbiota from sarcopenic individuals exhibited lower muscle mass and strength compared to those receiving microbiota from non-sarcopenic donors [123].

Yerrakalva et al. [141] found that individuals with higher baseline physical activity (light physical activity (LPA) and moderate-to-vigorous activity (MVPA)) and lower sedentary time levels (total time and prolonged sedentary bout time) had higher subsequent muscle mass indices (relative appendicular lean muscle mass (ALM) and BMI-scaled ALM, but not height-scaled ALM) an average of 5.5 years later. Baldanzi et al. [142] investigated the associations of accelerometer-based sedentary (SED), moderate-intensity (MPA), and vigorous-intensity (VPA) physical activity with the gut microbiota. The results show that MPA and VPA were associated with a higher abundance of the butyrate-producers Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia spp. [142]. Moreover, MPA was associated with a higher capacity for acetate synthesis, and SED with lower carbohydrate degradation capacity [142]. The positive effects of short-chain fatty acids on sarcopenia have been described previously. Therefore, physical activity can prevent sarcopenia by influencing the composition of the intestinal flora, which in turn affects the metabolic functions of the body.

The combined multimodal approach of dietary intervention and physical activity also shows significant therapeutic potential. Alway et al. [143] investigated whether the combination of resveratrol and exercise is more effective in reducing or reversing sarcopenia in humans compared to exercise alone. The study collected muscle samples from the participants to precisely assess muscle changes. The results showed that resveratrol treatment combined with exercise significantly enhances hypertrophy of type I and IIA fiber sizes compared to exercise alone, and leads to an increase in total muscle nuclei (satellite cells and myonuclei) [143]. Wang et al. [144] demonstrate that resveratrol supplementation alleviates high-fat diet (HFD)-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis, enhancing the abundance of anti-obesity bacterial strains such as Akkermansia, Bacteroides, and Blautia. Liao et al. [145] investigated the effectiveness of oligopeptide nutritional supplementation combined with exercise intervention in older individuals with sarcopenia in the community. The study enrolled 219 sarcopenic patients aged 65 and above, who were randomly assigned to four groups: a control group, a nutrition group, an exercise group, and a combined group. After 16 weeks of intervention, it was found that the weight and grip strength of the older people receiving exercise intervention increased, while the weight, grip strength, and gait speed of the subjects receiving nutritional intervention increased. However, neither exercise nor nutrition intervention alone could maintain the fat-free mass of older people. Only the subjects in the combined group maintained the muscle mass and fat-free mass of each segment after the intervention [145]. A systematic review found that combined exercise and nutrition intervention significantly enhanced lower extremity muscle strength in older adults with sarcopenia in Asia, compared to exercise alone [146]. Nutritional supplementation, including polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), vitamin D, and protein, provided additional benefits to physical exercise in increasing appendicular skeletal mass and lower limb muscle mass over 12 weeks [147]. Multimodal interventions seem to be the best strategy for preventing primary sarcopenia.

While lifestyle factors, disease status, and nutritional conditions significantly influence muscle mass, the distinct gut microbiome profiles observed in patients with primary sarcopenia suggest a compelling possibility: the gut microbiota may serve as a potential target for improving primary sarcopenia. For example, Prevotella copri has been observed to decrease in sarcopenic populations across multiple studies [24, 31, 148], suggesting that supplementation with Prevotella copri could be a promising therapeutic approach for sarcopenia. Additionally, the gut microbiota possesses several “processing” capabilities that the host organism lacks. For instance, Escherichia coli expressing the nicotinamidase enzyme PncA can help maintain NAD+ homeostasis, which is crucial for supporting mitochondrial function [71]. Similarly, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which express bile salt hydrolase (BSH) enzymes, can alter the intestinal bile acid environment, influencing circulating FGF15/19 and subsequently affecting protein synthesis [76]. The gut microbiota’s ability to express specific enzymes warrants further investigation as a potential avenue for therapeutic intervention. Furthermore, recent studies have highlighted the beneficial effects of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and unacylated ghrelin on skeletal muscle [53, 101]. The gut harbors sulfate-reducing bacteria that produce endogenous H2S, as well as ligands for receptors on ghrelin-producing cells. These findings suggest that these microbial products could also serve as therapeutic targets for sarcopenia. And the CSP-7 quorum-sensing peptide may become a biomarker for the early diagnosis of sarcopenia [125]. However, we must acknowledge the limitations of such preclinical studies, as their applicability to human populations remains uncertain and requires further validation through clinical research. Together, we provide novel perspectives on the gut-muscle axis for the prevention of sarcopenia.

LC, XX, JC, WC, and HT contributed to the conception and design of the work, including the development of literature search strategies, criteria, and the analytical framework for evidence synthesis. YC, LC, and LY devised the overall structure of the review. LC drafted the initial manuscript and designed comparative tables to integrate findings from selected studies. XX and JC performed systematic data extraction from included literature, validated the consistency of tabulated results, and resolved discrepancies through consensus discussions. WC and HT revised the manuscript for intellectual coherence, enhanced the analytical rigor of tables, and ensured alignment with the predefined research objectives. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript.

Clinical Medicine Research Pilot Project of the First People’s Hospital of Foshan (No. FSYYY202401002).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL36204.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.