1 Center for Immunology and Cellular Biotechnology, Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University, 236016 Kaliningrad, Russia

2 Department of Organization and Management in the Sphere of Circulation of Medicines, Institute of Postgraduate Education, I.M. Sechenov Federal State Autonomous Educational University of Higher Education-First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, 119991 Moscow, Russia

3 Laboratory of Cellular and Microfluidic Technologies, Siberian State Medical University, 634050 Tomsk, Russia

Abstract

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a widespread multi-component pathological condition characterized by meta-inflammation and cellular dysfunction. MetS and other metabolic diseases (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome (CKMS)) stem from the disorder of energy metabolism and changes in the structure and function of specialized organelles such as lipid droplets, endoplasmic reticula, mitochondria, and nuclei. The discovery of lipid droplets within the nucleus and the investigation of their functions across various cell types in both health and disease provide a foundation for discussing their role in the development and progression of metabolic syndrome. This review examines studies on lipid droplets in the nucleus, focusing on pathways of formation, structure, and function. The importance of (nuclear) lipid droplets in liver and brain is emphasized in the context of inflammation associated with obesity, MetS, and liver disease. This suggests that these structures are promising targets for the development of effective drugs against diseases associated with dysregulation of energy metabolism.

Keywords

- metabolic syndrome

- obesity

- nuclear lipid droplets

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- hypothalamic inflammation

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a widespread pathological condition encompassing obesity, insulin resistance (IR), dyslipidemia, triglyceridemia, and similar disorders. In MetS, morphological and functional changes occur at the organ and tissue level (adipose tissue, bone marrow, liver), at the cellular level (adipocytes, neurons, hepatocytes, monocytes, stellate cells, macrophages, lymphocytes) and at the subcellular level (nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mitochondria), leading to meta-inflammation, and the development of cardiovascular diseases, liver cirrhosis, cancer, and other serious conditions [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. The significance of this connection prompted a 2020 proposal to define diagnostic criteria and rename non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a chronic liver condition, as metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) to emphasize its relationship with MetS [8]. In addition, MAFLD is closely associated with obesity and the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD), the latter characterized by a gradual loss of normal kidney function due to excessive accumulation of lipid droplets (LDs) and oxidative damage [9]. The combination of the above pathologies constitutes cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome (CKMS), a systemic multiorgan disease resulting from adipose tissue dysfunction and leading to arterial, cardiac and renal damage [10].

The study of the molecular structure of intracellular organelles, their interactions, and the proteins involved in maintaining cell homeostasis and responding to changes in energy balance is a critical medical and biological endeavor. It enables the identification of potentially effective targets for controlling and preventing serious diseases [6]. A close relationship between the development of metabolic disorders (obesity, MetS, MAFLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), CKD, CKMS) and oncological diseases of various origins has been frequently highlighted in the literature [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. On the one hand, the incidence of clear cell renal cell carcinoma increases in obese individuals. On the other, the course of clear cell renal cell carcinoma in obese patients has a more favorable prognosis than in patients with a normal body mass index (BMI) [18]. This pathological interdependence is based on a disorder of adipose tissue function/distribution [1] associated with genetic/epigenetic factors and low-grade chronic inflammation that affects nearly all tissues and organs [19].

Moreover, epigenetic and genetic mechanisms are of paramount importance for the regulation of metabolism/neuronal activation in the nuclei and structures of the brain regulating appetite phases, taste preferences, and food intake the pituitary, the hypothalamus, and the pons [19]. A high-calorie diet initially activates adaptive mechanisms that alter cellular metabolism, hormone production, and inflammatory mediator synthesis. These changes drive target cell and organ responses, ultimately establishing a persistent inflammatory state against the background of altered homeostasis of the body. In obesity, epigenetic changes in proteins and transcription factors lead to reprogramming of cellular homeostasis, resulting in disruption of cells and tissues in the periphery [19].

Furthermore, morphofunctional changes and an inflammatory response are observed in obesity in the key area of the brain responsible for homeostasis and glucose metabolism the hypothalamus [20, 21]. Metabolic regulators in the hypothalamus include the agouti-related protein (AgRP) and the proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the arcuate nucleus (ARC), both altering neuronal activity [22]. Disruption of the regulatory mechanism increases food intake and energy expenditure due to chronic inflammation in the hypothalamus [23]. This inflammation is characterized by the activation of resident microglia, macrophage infiltration [24], and impaired pericyte function [25] in the context of obesity and high-fat diet (HFD) intake [26, 27].

Metabolic and nutrient distribution pathways in the neurons of the mediobasal hypothalamus (MBH) play a critical role in the development of metabolic disorders caused by changes in the levels of hormones, such as leptin, insulin, ghrelin, and glucose. Malonyl-CoA levels are also tightly regulated by glucose via the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway in MBH [28]. Glucose-mediated AMPK inhibition reduces the oxidation of fatty acid (FA) and increases the esterification of FA to triacylglycerol (TAG) in hypothalamic neurons and astrocytes [29]. It also leads to the activation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and the formation of malonyl-CoA, which is derived from glucose. Malonyl-CoA reduces mitochondrial acyl-CoA oxidation by inhibiting carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 (CPT-1). While malonyl-CoA is a substrate for the synthesis of fatty acids by fatty acid synthases, glycerol-3-phosphate obtained from glycolysis provides the basis for TAG formation. Thus, glucose metabolism reduces the oxidation of fatty acids and promotes the storage of glucose-derived carbon in the form of lipids [22].

Mechanistically, hypertrophy/hyperplasia of fat cells in patients with obesity leads to tissue hypoxia of parenchymatous organs, which impairs the oxidation of fatty acids in the mitochondria of target cells with their subsequent accumulation, coupled with the development of fatty degeneration, further hypertrophy of adipose tissue, and damage to organs and systems, including the liver, cardiovascular system, brain, and kidneys. Impaired cell function is often accompanied by mitochondrial dysfunction, high reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, lipid raft dysfunction, ER damage, nuclear membrane damage, lipid droplet formation, and, finally, the inability of the cell to compensate for lipotoxicity and maintain viability under stress by secreting alarmins and triggering apoptosis [6]. MetS, obesity, MASLD, and CKMS are associated with changes in lipid homeostasis in cells against the background of LDs formation. They regulate both cellular energy reserves and physiological processes by controlling signaling, autophagy, and posttranslational modifications in health and disease [30, 31, 32]. Recently discovered LDs within the nucleus under stress conditions highlight their direct role in regulating gene expression [33]. A detailed understanding of the functional potential of LDs in different locations in the development of metabolic diseases and in health will help identify targets (proteins, components of signaling pathways) whose manipulation could reduce the risk of complications and break the “vicious cycles” by blocking the key link in the pathogenesis of MetS and obesity.

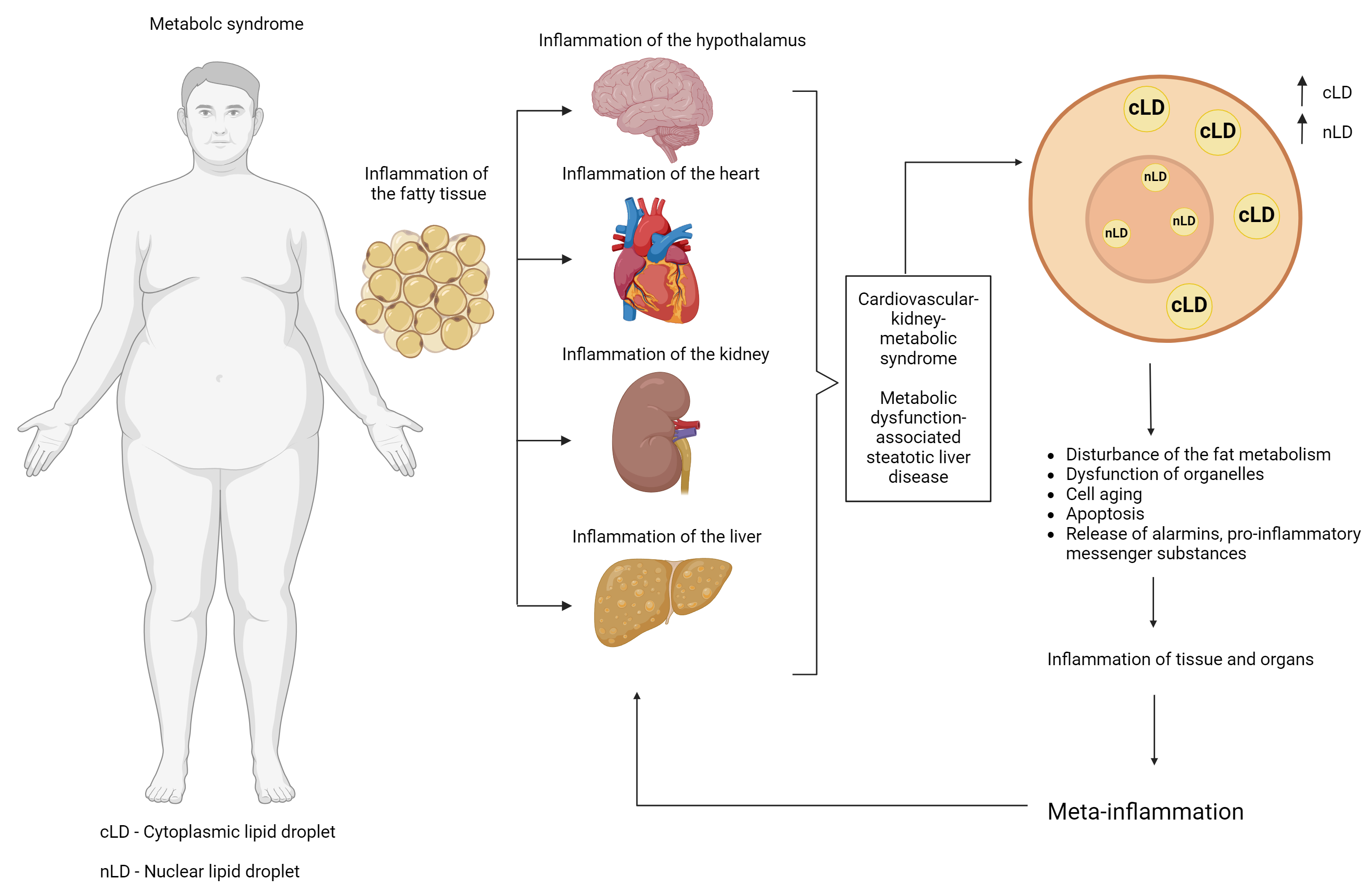

The aim of this review is to consider the structural and functional potential of LDs of different localizations with emphasis on nuclear LDs, as well as to describe of the possible role of LDs in metabolic diseases, such as MetS, obesity, and MASLD, from the perspective of molecular mechanisms responsible for the regulation of cellular energy metabolism under conditions of excessive nutrient intake and impaired utilization (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Possible linking role of lipid droplets in the progression of metabolic syndrome (and its components) and the development of pathological metainflammation. Created with Biorender.com.

LDs, also called liposomes and oil bodies (adiposomes), are unique organelles ranging from 1 to 100 µm in size and specialized in the storage (buffering) of intracellular lipids in the cytoplasm (cytoplasmic lipid droplets (cLDs)). LDs consist of a phosphatide monolayer membrane (phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylinositol) with outward-facing polar groups and acyl chains interacting with a hydrophobic core consisting of neutral lipids (triglyceride (TG), sterol/cholesterol ester) and non-polar lipids (diacylglycerol, cholesterol, monoacylglycerol) [34].

The heterogeneity of LDs in terms of size and composition has been repeatedly observed across various cell types. The largest LDs were associated with white adipocytes up to 100 µm; in brown adipocytes, the diameter of LDs measured 10 µm in adipocyte cells and 1–4 µm in non-adipocyte cells. These differences may also be attributed to the ability of LDs to retain hydrophobic antibiotic molecules, thereby regulating the viral life cycle [35].

Under normal conditions, LDs are located in the cytoplasm; however, certain cells contain unique structures localized in the nucleus, known as nuclear LDs (nLDs), which suggest novel functional roles for LDs in cell biology [33]. nLDs are found in hepatocytes, differentiated adipocytes, fibroblasts (though rarely), intestinal epithelial cells (Caco2), osteosarcoma cells (U2OS), human and rat hepatocarcinoma cells, cell lines (HepG2, McA-RH777, Huh7), yeast, and Caenorhabditis elegans cells [36, 37, 38].

According to the classical model, the ER is the site of formation (nucleation), growth, and budding of nLDs. At the same time, ER proteins are able to regulate the budding of LDs into the cytoplasm or to induce their translocation into the nucleus.

In the ER, neutral lipids are synthesized by the enzymes acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT)1/DGAT2, while sterol esters are synthesized by the enzymes acyl-CoA:cholesterol O-acyltransferase (ACAT)1/ACAT2 [35, 39].

TAG synthesis. De novo synthesis of TAG and LDs in the ER [40, 41, 42, 43] is catalyzed by four sequential enzymes: glycerol phosphate acyltransferase (GPAT), acyl glycerol phosphate acyltransferase (AGPAT), phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase (PAP), and acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) [44]. The final step of TAG synthesis is catalyzed by DGAT enzymes that covalently bind fatty acyl-CoAs (FA-CoAs) to diacylglycerols (DAGs). In mammals, the two enzymes DGAT1 (ER) and DGAT2 (ER, LDs) compensate each other in TAG storage [45, 46, 47]. In the ER, DGAT1 regulates the detoxification of excess lipids [46, 48].

Synthesis of steryl esters (SE). Enzymes for the biosynthesis of SE, which are localized in the ER and LDs [39], regulate the TAG:SE ratio depending on growth conditions and cell type [49]. The formation of the lipid core of LDs in the ER follows fundamental principles of physical chemistry [50, 51, 52]. Neutral lipids (TAG, SE) are formed by esterification of activated fatty acids to diacylglycerol/sterol (cholesterol) by ER enzymes. Sterol esters are formed by acyl-CoA:cholesterol O-acyltransferases (ACAT1, ACAT2). At low concentrations, neutral lipids are scattered between the leaflets of the ER bilayer, while at TAG concentrations of 5–10 mol% [53], they fuse into an oil lens through a delamination process, thus minimizing the interfacial tension/energy cost associated with deleterious effects between the two immiscible phases (neutral lipids and phospholipid bilayers) [54]. Subsequently, a portion of the newly formed LDs (initial LDs (iLDs)) recruits ADP-ribosylation factor 1 (Arf1)/coat protein complex I (COP-I) enzymes and proteins across the ER-LDs membrane bridges to facilitate local TG synthesis, forming larger expanding (luminal) LDs (eLDs) [41, 55, 56]. The phospholipid composition of the ER membrane plays a crucial role in LD budding, as it influences the surface tension of the membranes [57, 58]. The tension is important to maintain the round shape of LDs, while the phospholipid composition influences the efficiency of budding due to geometric effects [50].

The surface tension facing the ER lumen is higher than that facing the cytoplasmic membrane [55], and budding of LDs tends to occur when the tension is lower [56]. However, changes in the local composition of ER phospholipids play a pivotal role in this process [56, 57].

Lipids with inverted shape (predominantly hydrophilic head) phosphatidylinositol (PI) and lysophospholipids generate a positive curvature that facilitates the formation/detachment of LDs towards the cytosol [40, 58, 59]. Cone-shaped lipids (predominantly lipolytic structures), such as diacylglycerol (DAG) and phosphatidylethanolamine, induce negative curvature that promotes incorporation of LDs into the ER membrane bilayer [58, 60] and prevents budding by stabilizing the association between the ER and LDs [40, 50, 61].

The manner in which ER architecture influences lipid membrane composition and LD formation remains unexplored. The ER consists of flat membrane sheets and curved tubes supported by curvature-supporting and stabilizing proteins reticulons and atlastins [62]. However, ER-associated proteins (class I proteins), such as fat storage-inducing transmembrane protein (FITM), seipin, lipid droplet assembly factor 1 (LDAF1), and dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1), are also involved in LD biogenesis.

SEIPIN. Seipin coordinates LD biogenesis by forming a complex with an oligomeric toroidal structure, which traps neutral lipids (TAG, DAG) in the ER bilayer and promotes LD nucleation [63, 64, 65].

FITM. These conserved transmembrane proteins of the ER bind TG and DAG, promote lipid accumulation (in the case of FITM), and play a role in LD formation [66]. The diphosphatase activity of FITM supports LD formation and nucleation and protects against cellular stress [67]; FITM is required to stimulate the formation of LDs from the ER.

FITM2 is the only fatty acyl-CoA diphosphatase in the ER lumen. Binding of phosphoanhydride upon cleavage of acyl-CoA is thought to be linked to conformational changes that drive active pumping of neutral lipids across the membrane, reducing DAG content near the LD budding site at the ER [67]. FITM2 has been found to be involved in the metabolism and distribution of non-layer lipids, affecting LD biogenesis along with the curvature and surface tension of the ER monolayer [68]. Moreover, FITM2 has been shown to localize to sites where LDs form and promote LD appearance by reducing DAG levels [67]. It also binds to the cytoskeletal protein Septin 7, which ensures normal LD biogenesis, and to proteins that form ER tubules (reticulon-4 (Rtn4), receptor expression enhancing protein 5 (REEP5)) [69]. FITM2 and Septin 7 interact during differentiation of adipocytes at LD nucleation sites [69].

In addition, depletion of ER-associated proteins SCS3/YFT2 delays the formation of LDs and their retention in the ER [67].

Thus, the functional capacity of FITM2 is mediated by TG biogenesis and the redistribution of TG into LDs, which influences the surface tension of LDs and determines the direction of budding/movement of LDs, toward the cytoplasm or ER.

LDAF1 (TMEM159). The seipin-binding protein LDAF1 (TMEM159)/promethin is an interaction partner of seipin. Together, LDAF1 and seipin form an oligomeric complex (600 kDa) that is decimated by TG. LDAF1 recruits seipin and marks the sites of LD formation and regulates LD biogenesis through the accumulation and distribution of TG in LDs [70]. During LD maturation, LDAF1 dissociates from seipin and migrates to the surface of LDs [71].

In the absence of LDAF1, LDs can only be formed in the ER at high TG concentrations [71].

DRP1. The dynamin protein DRP1 is involved in the division of mitochondrial membranes [72], with DRP1 oligomers localized in the ER. DRP1 has been found to form peripheral ER tubules that establish contact with mitochondria [73]. In adipocytes,

DRP1 deficiency in adipose tissue is associated with retention of LDs in the ER lumen and processes such as ER stress, abnormal autophagy, morphological changes of cLDs, and mitochondrial dysfunction. This deficiency causes impaired energy expenditure throughout the body, as observed in Adipo-Drp flx/flx mice [72]. In addition, dominant-negative mutations of DRP1 pathologically alter the structure of the ER membrane and impair the dissociation of LDs from the ER [72].

The nucleus is separated from the cytoplasm by a two-layered phospholipid nuclear membrane consisting of the outer (ONM) and the inner nuclear membrane (INM). The luminal space between the membranes merges into the ER lumen. The invaginations of the nuclear membrane into the lumen of the nucleoplasm form the nucleoplasmic reticulum (NR) of two types. An extension of the INM, type-I NR can interact with the nucleoplasm, while type-II NR consists of invaginations of both the inner and outer nuclear membranes [74].

Nuclear lipids, which are actively involved in cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis, are important structural and functional components of the nucleus. Lipids make up 16% of the nuclear content, followed by the most important components proteins and nucleic acids [75].

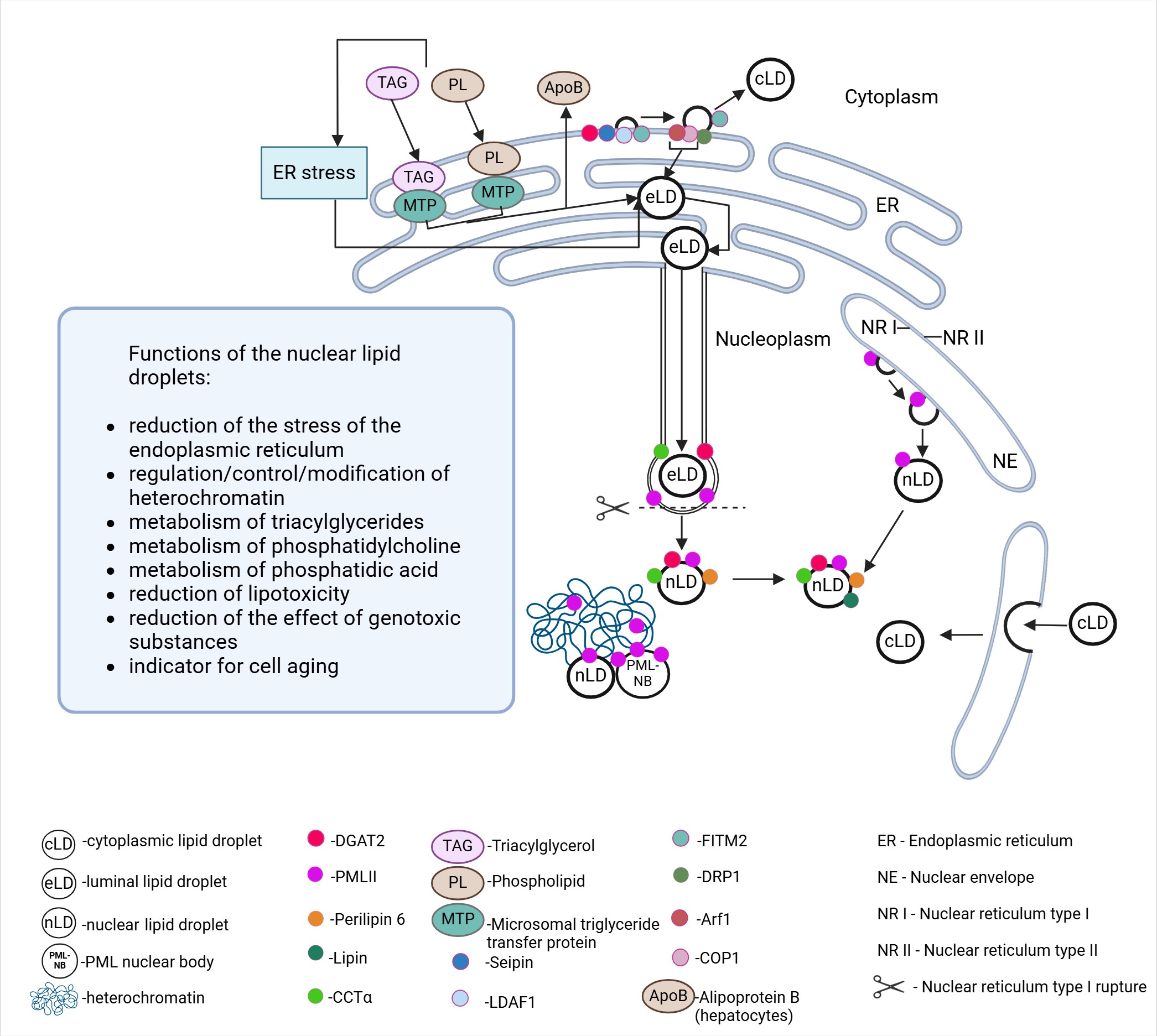

The activity of excess FA promotes the formation of nLDs, which consist of a neutral lipid core and lipid biosynthesis enzymes. Similar to cLDs, surface tension and the composition of lipids with either negative or positive intrinsic curvature play a critical role in the biogenesis of nLDs [59]. The classical site for the synthesis of LDs is the ER, which is directly connected to the nuclear envelope. Another important factor is the INM, which has its own lipid metabolism facilitated by proteins and enzymes that regulate the transfer of DAG and TG [76]. In general, the process of nLD formation from the ER is controversial and challenging to define in terms of its molecular components. A variety of pathways for the formation of nLDs have been described in the literature to date: (1) from lipoprotein precursors in the ER lumen (hepatocytes, lipoprotein-producing cells) with subsequent translocation to the nucleus and (2) with subsequent translocation to the INM [33]. Both mechanisms of nLD formation may occur in the same cell and are likely interconnected. cLDs have also been described as capable of entering the nucleus [36]. Moreover, it has been hypothesized that a specific timing governs the budding of maturing LDs (eLDs) into the cytoplasm or their movement toward the nucleoplasm along type-I NR, leading to the subsequent formation of nLDs [77]. All these mechanisms are directly related to proteins and enzymes localized in the ER, INM, and LDs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Formation of intra-/extranuclear nuclear lipid droplets and their functional potential within the nucleus. Created with Biorender.com.

Although the functional capacity of nLDs is not well understood, experimental modeling has uncovered some of their key properties. They may serve as platforms for activating CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase

The earliest identified mechanism of nLD biogenesis involves the migration of mature eLDs (expanding LDs) into the nucleoplasm. Although this nLD formation mechanism follows the classical pathway of LD development by budding into the cytoplasm, at a certain stage and under the influence of inducing conditions, it starts to work towards the nucleus.

In the ER of hepatocytes (and hepatoma cells), TAG-enriched apolipoprotein B100 (apoB)-containing very low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs) accumulate and migrate via COPII transport vesicles toward the cis Golgi to be subsequently secreted into the blood. In the ER lumen, microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) facilitates the delivery of TAG and phospholipids to apoB to form VLDL precursors and eLDs. ER stress and TAG overproduction induce the translocation of a portion of eLDs from the ER to the INM extension (type-I NR) via colocalized enzymes of TG synthesis (DGAT2) and phosphatidylcholine (CCT

Another mechanism for the formation of nLDs (yeast, U2OS) involves the promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML) [37] and INM enzymes (GPAT3,4; AGPAT1, lipin-1, DGAT1,2) [81, 82]. nLDs formed de novo on the INM contain TAG, DAG, and phosphatidic acid (PA) [81] (Fig. 2).

In yeast, nLDs detach from the INM [76], while their lipid monolayer remains adjacent to the INM [76]. Localized on the INM, seipin is, in turn, necessary for the correct formation of the membrane bridge connecting the INM and nLDs. Phosphatidic acid is converted either to diacylglycerol by phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase 1 (Pah1) for triacylglycerol synthesis or to cytidine diphosphate diacylglycerol by phosphatidate cytidyltransferase (Cds1) for phospholipid synthesis. Pah1 and Cds1 are present in the INM, and the inhibition of Cds1 promotes nLDs biogenesis. The presence of additional genes involved in lipid synthesis, such as diacylglycerol acyltransferase gene (Dga1) and Lro1, in the INM remains unidentified [50, 76].

A close association between nLDs and PML protein has been demonstrated in eukaryotic cells. A probable interaction of nLDs with PML-containing nuclear bodies (PML-NB) has also been described, as nLDs carrying the PMLI isoform are characterized by a radial bristle-like structure, a feature typical of PML-NB [37]. The highest colocalization with nLDs of all PML protein isoforms (I-VII) has been found for the PML-II isoform. This is likely due to the specific structure of PML-II, which includes a unique C-terminal domain containing two motifs: one for binding to the nuclear periphery and another for extranuclear localization. The first motif mediates the distribution of the PML-II protein along the nucleoplasmic surface of the INM with the formation of PML-II plaques/patches (in U2OS cells, cells from the liver). These regions are characterized by the absence of LBR, SUN1 (an integral INM protein) [83] and INM transmembrane proteins associated with lamin A/B. The binding of nLDs to chromatin via membrane-associated PML-II (as in PML-NB) has been implicated, particularly in cells with PML-II plaques/spots [37]. PML-II has been found to play a key role in the formation of 50% of nLDs in Huh7 cells [37]. Silencing of the PML gene in U2OS cells has been accompanied by a decrease in the number of nLDs [81], as well as in Huh7 cells, confirming the role of PML-II in binding nLDs to membranes [37] (Fig. 2).

nLDs in hepatocytes are associated with PML NB, which is involved in the regulation of gene transcription [37]. In contrast to perilipin-2 (PLIN2), in mammals, PLIN5 is located in the nucleus and functions as part of a transcriptional regulatory complex that controls mitochondrial gene programs [84]. Although no association of PLIN5 with nLDs is known [50], nLDs have been identified with dyes specific for perilipin-3 (PLIN3) and Rab18 [37]. LDL synthesis in hepatocytes has been found to involve MTP, which is localized in the ER. MTP assists in the transfer of ceramides and sphingomyelin to apoB-containing lipoproteins and participates in the biosynthesis of cholesterol ester and cluster of differentiation 1d (CD1d) [85]. MTP induces the formation of apoB-containing primary particles and ApoB-deficient eLDs in the ER, leading to the production of mature LDL [85, 86, 87]. ER stress increases MTP activity [88], induces the accumulation of apoB-deficient LDs, and generates more nLDs, which serve as LDL precursors in the ER lumen. eLDs growing in type I NRs are translocated to the nucleoplasm as the NR membrane ruptures in the presence of localized lamin deficiency and the membrane becomes mechanically unstable. It is assumed that MTP-dependent lipid transfer into eLDs leads to their growth and the destruction of the type-I NR membrane. In addition, the lack of lamins could be related to the presence of the PML-II protein [37, 89].

Thus, apoB-deficient eLDs give rise to nLDs [90], which, in turn, recruit CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase

Although nLDs are associated with many metabolic disorders, the exact role of nLDs in pathogenesis and pathophysiologic processes remains unclear [93]. In particular, nLDs have been identified in hepatocytes associated with steatosis and chronic hepatitis A1-F1. An analysis of 583 hepatocytes revealed 402 cells with isolated cLDs and 64 cells with LDs localized in the nucleus. Of these cells, 60 exhibited deformed nuclei due to the presence of large cLDs or as a result of the cLDs being partially enclosed by the nuclear membrane within the nucleus, while 4 cells contained true nLDs [95]. However, further research into nLDs is of great interest as there are multiple pathways for nLD formation, and nLDs are likely to have different functions depending on conditions of formation, cell types and degree of cellular stress. A more detailed study of the biology and functioning of nLDs will enhance our understanding of their potential for combating severe metabolic disorders.

MASLD denotes a spectrum of histological changes in the liver closely linked to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and obesity, sharing similar pathophysiological features with hepatic steatosis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), fibrosis, cirrhosis and MASLD-related hepatocellular carcinoma (MASLD-HCC) [96, 97]. MASLD is characterized by inflammation, intestinal dysbiosis, and metabolic dysregulation [98, 99]. Research indicates a link between MASLD and the development of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease [100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105], contributing to the concept of CKMS. CKMS is characterized by increased concentrations of phospholipid derivatives (ceramides, sphingosine), oxidized LDL, and lipoproteins (a, b), which are detrimental to renal and cardiac function [106]. All pathological changes in the organs in MASLD and CKMS, related to organelle dysfunction, are also linked to impaired cellular metabolism, oxidative stress, and impaired function and structure of organelles against the background of excessive LD accumulation [107].

3.1.1.1 Lipid Droplets and Genetic Factors

Genetic factors play an important role in the pathogenesis of MASLD and CKMS [8, 96, 108].

Genetic alterations include single nucleotide polymorphisms in the following genes: patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3), transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2), membrane-associated O-acyltransferase domain containing 7 (MBOAT7), glucokinase regulatory protein (GCKR), and hydroxysteroid 17-beta-dehydrogenase 13 (HSD17B13) [96].

PNPLA3. The PNPLA3 gene encodes a multifunctional enzyme involved in liver lipid regulation through its triglyceride lipase and acylglycerol O-acyltransferase activities on the surface of LDs [109]. The strongest risk factor for MASLD is a non-synonymous variant (rs738409 [G]) in the pNPLA3 gene, which is strongly associated with high liver fat, inflammation, and MASLD-HCC [110]. This mutation codes for a replacement of isoleucine by methionine at position 148 (PNPLA3-I148M) [97]. It has been suggested that PNPLA3-I148M impairs TAG hydrolysis on cLDs, causing steatosis [111, 112]. Expression of PNPLA3-I148M in stellate liver cells has been found to lead to mitochondrial dysfunction due to the accumulation of free cholesterol (impaired Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR

TM6SF2. Predominantly expressed in the liver and small intestine, the TM6SF2 gene codes for proteins involved in lipid metabolism through TAG secretion in the liver [123]. The variant rs5842926 (C

MBOAT7. The MBOAT7 gene encodes an integral membrane protein that serves as a lysophosphatidylinositol acyltransferase for the transfer of polyunsaturated acyl-CoA to lysophosphatidylinositol and other lysophospholipids in the Lands cycle. The variant rs641738 (C

GCKR. The GCKR gene encodes a glucokinase regulatory protein that inhibits glucokinase expressed in the liver and pancreatic islet

MLXIPL. The single nucleotide polymorphism rs3812316 has been linked to

ZPR1. rs964184 polymorphism of the ZPR1 gene is associated with lipid and metabolic disorders, including cardiovascular disease, liver disease, and T2DM, serving as a potential biomarker for MASLD in GWA studies [133].

HSD17B13. HSD17B13 encodes LDs enzymes required for the degradation of LDs in the liver [136]. The rs72613567 (T

It is necessary, however, to take into account the genetic background and chromosomal alterations affecting individual predisposition to the development of liver metabolic diseases. For example, the aforementioned PNPLA3-I148M variant on chromosome 22 causes an increased risk of MASLD and occurs predominantly in women [140, 141, 142]. Conversely, the RNA-binding motif gene on the Y chromosome and the testicular-specific protein Y coordinator (RBMY), which regulates the activity of androgen receptors, contribute to the development of HCC in men [143]. Women have a higher methylation profile in the X chromosome compared to men, which leads to a change in gene expression in the liver and lowers cholesterol and TG levels in accordance with the metabolic activity regulating the development of hepatopathologies [144].

Thus, there are undeniable sex differences that determine the frequency and differential risk of developing metabolic diseases in men and women.

3.1.1.2 Lipid Droplets and Hormones

Sexual dimorphism plays a crucial role in the development of MASLD and CKMS, as estrogens and androgens affect the risk of liver and metabolic diseases [140]. Estrogens regulate functions related to sexual differentiation, reproduction, bone health, and control of the main nucleus of energy metabolism, with effects influenced by sex, age, and diet [145]. In addition, estrogens operate by facilitating insulin secretion and controlling the availability of glucose. They also modulate energy distribution by favoring the use of lipids as the main energy substrate when their availability exceeds that of carbohydrates. Moreover, estrogens activate antioxidant mechanisms, controlling the energy metabolism of the whole body [145].

Estrogen has a tissue-specific effect. For instance, adipose differentiation-related protein (ADRP), a major component of LDs closely associated with the onset of lipid accumulation, has been downregulated in ovariectomized and 17

In perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with decreased estrogen production and an indirect decrease in insulin sensitivity [149], a redistribution of body fat and the development of metabolic disorders, including MASLD and CKMS [8], have been observed. Additionally, elevated testosterone levels in women have been shown to increase their risk of developing MASLD [150], while, in men, the same pathology is associated with low testosterone levels [151, 152].

The accumulation of LDs is a hallmark of CKD [152]. In the kidneys, lipids are deposited in the paranephric space, renal sinus and renal parenchyma. Excessive accumulation of fatty acids in the paranephric space is associated with CKD and may contribute to renal dysfunction, whose mechanism has not yet been deciphered [153, 154]. Excess perirenal adipose tissue can compress the renal vasculature and renal parenchyma, which increases renal interstitial hydrostatic pressure and renin release, while lowering the glomerular filtration rate [154, 155]. In addition, fat accumulation in the renal sinus adjacent to the renal vasculature can trigger the production of mediators, such as adipokines, proinflammatory cytokines, nitric oxide (NO), and ROS [156]. The accumulation of LDs and the dysfunction of the renal sinus contribute to renal inflammation. Notably, meta-inflammation, associated with obesity, plays a direct role, starting from visceral adipose tissue (secretion of leptin, interleukin (IL)6/10, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), c-reactive protein (CRP)) [157] and leading to fibrosis, hypertension, and the progression of CKD. It has been found that the kidney can be damaged by dyslipidemia, contributing to lipid accumulation and an imbalance between fatty acid supply and utilization [158]. In addition, LDs act as intracellular mechanical stressors that trigger inflammation and fibrosis in the renal parenchyma [159]. Thus, progressive renal dysfunction is associated with the deposition of fat and LD in the renal cortex and medulla (parenchyma), which leads to the development of glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, and proteinuria [152]. The epithelium of the renal tubules is the site of lipid deposition in HFD, characterized by the presence of giant vacuoles of lysosomal/autophagosomal origin, containing oxidized lipoproteins and multilayered bodies. These bodies have a lipid profile that differs from that of cytoplasmic LDs [160]. Excessive deposition of LDs in podocytes leads to lipotoxicity, abnormal glucose/lipid metabolism, and cell death [161, 162]. This process is associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, ER stress, actin cytoskeleton reorganization, and IR [163]. FAs cause LDs to accumulate lipids by direct uptake or by stimulating the biosynthesis of other FAs. Oxidative stress has been found to induce the formation of oxidized lipoproteins and changes in the TG profile in renal LDs, similar to that in hepatocytes in steatohepatitis. Changes in lipid metabolism lead to a decrease in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in the kidneys, which have a protective effect on the cytoplasmic matrix of cells. Excess PE results in a decreased PC/phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) ratio, while promoting the localization of PLIN on the surface of LDs, furthering the accumulation of lipids, and stimulating the growth of LDs [9]. It has been demonstrated that a high concentration of urea toxin as a result of impaired urea excretion can exacerbate adipose tissue inflammation and increase intestinal permeability, contributing to systemic and renal dysfunction. Moreover, PPAR

Dysfunction in the storage and turnover of endogenous TG in LDs cardiomyocytes is linked to impaired transcriptional regulation of metabolic gene expression in heart failure. This dysfunction also results in reduced mitochondrial energy production, which is necessary to sustain cells and meet the energy demands of the contractile apparatus [166, 167]. In addition, LDs can prevent lipid lipotoxicity by sequestering toxic lipid species: cholesterol, ceramides, and DAG [168]. The accumulation of cholesterol esters (CE) in LDs of macrophages (foam cells) in arteries precedes the development of atherosclerosis.

Although PLIN5 has been reported to accumulate nLDs in cardiomyocytes from starved mice, the ability of PLIN5 to regulate gene expression in the heart remains unclear [168]. Reduced PLIN5 expression in the heart correlates with impaired cardiac function [169, 170]. pLIN5 gene knockout in mice has been shown to result in the absence of LDs in the heart muscle and the development of cardiomyopathy [171]. Overexpression of PLIN5 in the heart is associated with cardiac steatosis and cardiac hypertrophy [172].

Intracellular accumulation of toxic lipid metabolites leads to cellular abnormalities that promote cardiac remodeling and cardiac dysfunction. Moreover, FA from the bloodstream, along with LD, supply the heart with nutrients and support its functions. Excessive supply of FA to the heart is associated with a decrease in left ventricular function [173], LA accumulation, and the development of cardiac steatosis. The accumulation of LA in cardiac myocytes has been linked to obesity-related heart failure, T2DM, and hyperlipidemia [168, 174]. Other consequences include the activation of PPAR

The brain is able to detect circulating nutrients, hormones, and adipokines released by metabolically active tissues, such as the liver and adipose tissue, and initiates appropriate metabolic and behavioral responses to achieve metabolic homeostasis. The neuroendocrine regulation of energy balance takes place in various metabolically sensitive neuronal subpopulations of the hypothalamus. Altered lipid supply to the brain during HFD blunts the function of hypothalamic neurons and impairs their response to food signals, intragastric nutrients, neuropeptides, and adipokines [177]. Hypothalamic microglia control lipid metabolism and are involved in the development of IR [178]. Glia-like tanycytes lining the 3rd ventricle of the hypothalamus are known to serve as an interface between circulating metabolites (in blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)) and energy-sensing hypothalamic neurons [179, 180, 181]. In response to an increase in circulating FAs, tanycytes secrete mediators that modulate neuronal activity and peripheral energy balance. In addition, tanycytes and astrocytes in the hypothalamus exhibit distinct mechanisms for perceiving lipids [182, 183]. Astrocytes are a major source of brain lipoproteins that transport lipids to neurons and other glial cells, contributing to systemic energy balance [184]. They regulate the function of microglia and macrophages in the brain via horizontal lipoprotein flow [185]. In the context of elevated FA and saturated FA, lipid cross-talk between astrocytes, microglia and tanycytes promotes hypothalamic inflammation hypothalamic reactive gliosis [186, 187]. Lipoprotein lipase has been shown to play an important role in the regulation of central energy homeostasis by astrocytes. Moreover, it is downregulated in the hypothalamus by palmitic acid and TGs, leading to decreased LDs, excessive weight gain, and glucose intolerance in mice [188, 189]. Microglia are also able to remove unwanted lipids in the brain and promote lipid recycling through cholesterol efflux [190]. A model has been proposed describing horizontal lipid flow from microglia to oligodendrocytes, the primary myelinating cells in the brain, which utilize glia-derived lipids to myelinate axons and regulate neuronal function [191]. Oligodendrocytes in the hypothalamus are regulated by diet, leading to changes in food intake and weight gain [192].

HFD-induced malnutrition is associated with the development of triglyceridemia, which, in turn, is associated with obesity, T2DM, and aging, leading to neuroinflammation, cognitive impairment, and neurodegeneration [192, 193]. Chronic activation of microglia and the overproduction of inflammatory mediators lead to the expression of costimulatory molecules, neuronal dysfunction and apoptosis, loss of dendritic complexity, reduced number of synapses, and decreased synaptic plasticity key components of neuroinflammation [194, 195]. Autophagy has been shown to play an important role in the normal function of brain cells. Impairment of autophagy leads to an accumulation of glial lipids in the form of LDs, a feature characteristic of aging. Hypothalamic lipotoxicity is inextricably linked to inflammation and reactive gliosis, contributing to leptin resistance, insulin resistance, and obesity [196, 197]. Specifically, aged mice have shown an increase in the number and density of brain cells containing lipids in certain brain regions, leading to neurodegeneration [198]. In cases of mitochondrial dysfunction, a distinct population of senescent glial cells has been identified as promoting lipid deposition in non-senescent glial cells (observed in Drosophila). Similar effects have been observed in senescent human fibroblast cultures [199], with the accumulation of senescent glial cells contributing to the development of age-related diseases [200]. Moreover, inflammatory signaling has been shown to induce the accumulation of LDs in an activator protein 1 (AP1)/Jun2-dependent manner [201]. An inextricable link has been established between oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and the accumulation of lipids during aging in brain neurons [202, 203]. Notably, lipids can play a protective role against oxidative stress, which has been observed in AP+ glia that secrete lipids that are taken up and accumulated by AP– glia [201]. Senescent glial cells also accumulate lipids in the subventricular zone, including regions around the lateral ventricles, third ventricle, fourth ventricle, and periventricular gray matter [204].

The combination of LD protein/lipid composition and lipid flux through the LD storage pool is considered the best indicator of cell function, as it regulates signaling and lipid storage capacity to prevent lipotoxicity at high lipid concentrations [201]. The ARC of the hypothalamus contains populations of neurons involved in insulin resistance, while 3V tanycytes control systemic energy metabolism [205, 206, 207]. In low lipoprotein receptor-deficient (Ldlr–/–) mice fed an HFD, heterogeneous deposition of LDs has been observed along the 3V ependymal layer at three rostral-caudal levels (suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN); periventricular nucleus, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH); arcuate nucleus, ARC) and three ventricular regions (superior, middle, and inferior) [208]. Most astrocytes and

In astrocytoma cells, FA-binding protein 7 (FABP7) and oleic acids can accelerate the formation of LDs-PML-NB nuclear complexes and increase the expression of genes related to tumor proliferation [149]. Overexpression of FABP7 in the U87 astrocytoma cell line results in a higher accumulation of LDs and greater expression of antioxidant enzymes [150]. In addition, FABP7 has been shown to play a protective role against toxic oxygen species (ROS) in astrocytes through the formation of LDs. Specifically, in primary astrocytes from FABP7 knockout mice, ROS induction has led to a significant reduction in LDs accumulation, accompanied by increased ROS toxicity, impaired thioredoxin (TRX) signaling, activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK), and increased expression of cleaved caspase 3, ultimately leading to astrocyte apoptosis [150].

Obesity and MetS have a detrimental effect on liver health and contribute to the development of simple steatosis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [218].

An examination of 583 hepatocytes from a liver biopsy of a patient with moderate steatosis infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (chronic hepatitis grade A1-F1) revealed 402 cells with isolated cLDs and 64 cells with LDs localized within the nucleus. Sixty of these cells had deformed nuclei due to the presence of large cLDs or the presence of cLDs within the nucleus that were partially surrounded by the nuclear membrane, while 4 cells contained true nLDs [95]. The presence of cLDs within the nucleus may be explained by the perinuclear location of the ER, which is an extension of the nuclear envelope that facilitates their uptake by nuclear envelope invagination [95].

True nLDs, which are specific subdomains within the nucleus that store nuclear lipids, may regulate lipid homeostasis in the nucleus through their interaction with heterochromatin [95].

As mentioned above, nLDs, which are present in approximately 1% of cells, can directly regulate nuclear lipid metabolism, signaling, and interaction with FA-ligated transcription factors, such as PPAR, HNF4

nLDs have been detected in HepG2 cells and in nuclei of hepatocytes isolated from rat liver. These nLDs consisted of 37% lipids and 63% proteins, with 19% TAG (oleic, linoleic and palmitic acids), 39% cholesterol esters, 27% C, and 15% polar lipids. In contrast, cLDs contained 91% TAG. The study has demonstrated that nLDs are an intranuclear domain that contains neutral lipids and is involved in lipid homeostasis in the nucleus [75]. They had a random intranuclear distribution in the size of several small droplets [75]. A study of liver biopsies from 80 patients with hepatopathologies of different etiologies has also shown the presence of several types of nLDs in hepatocytes [74]. nLDs were detected in 69% of the liver samples, while cLDs localized in the nucleus were observed in 32%. MASH was associated with the highest percentage of nLDs in the hepatocytes and the absence of cLDs in the nuclei. There was a correlation between the expansion of the ER lumen, which forms against the background of ER stress, and the frequency of nLD formation in the hepatocytes. According to the results of the study, ER stress associated with liver enlargement was linked to the formation of nLDs in 5–10% of hepatocytes. cLDs in the nucleoplasm have been frequently identified in hepatocytes from patients with low plasma cholesterol levels, with their formation correlating inversely with the secretion of very VLDL [74].

Thus, there are two types of nLDs in hepatocytes that are associated with different liver diseases, such as MASH, drug-induced liver intoxication, and chronic autoimmune hepatitis. In hepatocytes, lipids stored in cLDs can be released by lipolysis and recycled in the ER lumen to generate VLDL precursors [220, 221]. Suppression of VLDL secretion by ER stress leads to the accumulation of LDs precursors in the ER and their transfer (eLDs) to the nucleus via type-I NR invagination, followed by conversion of eLDs to nLDs after exiting the INM [37, 78].

Lipin, a member of the PA phosphatase family, is associated with unregulated PA accumulation in the INM, leading to the binding of lipin-1b to the nuclear envelope (NE) and the formation of nLDs in U2OS cells [82]. A recent study in animals (McArdle’s RH7777 rat liver cell lines, McA cells) with FITM2 protein deficiency (Fitm2 gene deletion) (in mice) has shown that, under high-calorie diet conditions, plasma TG levels decrease while TG accumulates in the ER, leading to impaired ER morphology and ER stress [222]. These changes may also be associated with increased formation of nLDs in hepatocytes and enhanced expression of the PML protein, which was not investigated in the work presented [222].

In liver cells, nuclear lipids are located in nuclear membranes and in the nuclear matrix free of nuclear membranes. Although, in this case, polar nuclear lipids (glycerophospholipids) are mainly located in nuclear membranes, 10% of the lipids are associated with chromatin [75]. The Kennedy pathway mediates the synthesis of glycerophospholipids with the formation of PC through the catalytic reaction of the enzyme CCT

Studies in hepatocytes and U2OS cells have shown that nLDs contain enzymes that regulate TAG synthesis, including DGAT1/DGAT2, AGPAT2, GPAT3/GPAT4, and acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain 3 (ACSL3) [37, 78].

cLDs in the nucleus of hepatocytes, which are sequestered in type-II NR and separated from the ER, can restrict the transfer of lipids between organelles, leading to a decrease in lipoprotein synthesis in the liver in patients with low plasma sterol levels [74]. Presumably, sterols are sequestered to a high degree in cell membranes (in the nucleus), which leads to the deposition of the ONM and INM in hepatocytes. In the case of severe steatosis (20%), in hepatocytes with an abundance of cLDs, cholesterol accumulates in the form of cholesterol esters in cLDs, inhibiting the formation of cLDs that are scavenged by type-II NR [74]. This hypothesis has been supported by the study conducted by Liu et al. (2023) [230] on freshwater fish (Gobiocypris rarus) from China exposed to cadmium. The study has established a link between liver injury and the accumulation of cLDs, cLDs in the nucleus, and the appearance of nLDs, all against the background of abnormal increase in rough ER lamellae (RER), hepatocyte necrosis, a rise in serum levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides and lipids. However, there was no alteration in the transcription of the PPAR

Thus, NE lipid imbalance caused by overload of cells with lipotoxic FAs may induce the formation of nLDs as a mechanism to reduce the deleterious effects of FAs, and minimize the risk of losing NE homeostasis [33]. In addition, this mechanism of nLD formation may be triggered in response to genotoxic drug-induced impairment of DNA replication, contributing to the slowing/silencing of replication fork activity [77, 230].

It has been found that long-term chronic liver injury caused by MASLD can lead to the proliferation of certain hepatocytes in an attempt to maintain liver homeostasis [231].

MetS is a multi-component pathological condition leading to the dysfunction of cells, organs, and body systems. It is associated with the development of more severe pathologies affecting the organs and systems of the body, such as MASLD and CKMS. The discovery of new, unique nuclear structures specific to certain cell types and involved in lipid metabolism, known as nLDs, has drawn the attention of scientists to their organization, formation, and biogenesis in cells. However, the available data on both normal and pathological conditions is insufficient to fully explain the existence of nLDs or determine their exact role in cells. At the same time, experimental research on nLDs has advanced sufficiently to allow for discussions on the critical role of these organelles in diseases linked to energy imbalance, aging, and the lipotoxic effects of excess fatty acids. These factors contribute to the development of obesity, liver and vascular diseases, kidney pathologies, brain inflammation, and other components of MetS, MASLD, and CKMS. The close association of LDs with the nucleus may indicate different roles of nLDs in hepatocytes and brain cells, including their involvement in the metabolism of phosphatidic acid [76, 82], phosphatidylcholine [37, 81, 82, 229], triglycerides, as well as their response to genotoxic drugs [77, 230], interaction and regulation of heterochromatin [75], induction of cellular senescence, and provision of readily available FAs for the nuclear membrane [75]. This confirms that the formation of LDs within the nucleus is compensatory and antitoxic; it helps maintain the functional capacity of the nuclear membrane, reduce ER stress [222], and preserve the integrity of the cell under conditions of metabolic disturbances, contributing to the development and progression of metabolic diseases. A deeper and more detailed study of intranuclear structures, along with a better understanding of the functioning of nLDs, will enable the identification of specific, pathogenetically-based targets for combating metabolic disorders.

FA, fatty acids; MetS, metabolic syndrome; IR, insulin resistance; HFD, high-fat/high-calorie diet; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; TG, triglyceride; TAG, triacylglycerol; DAG, diacylglycerol; LD, lipid droplet; eLD, luminal lipid droplet; cLD, cytoplasmic lipid droplet; nLD, nuclear lipid droplet; AgRP, agouti-related protein neurons; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; ARC, arcuate nucleus; PVH, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; MBH, mediobasal nucleus; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus; ACC, Acetyl-CoA carboxylase; CPT-1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1; GPAT, glycerol phosphate acyltransferase; AGPAT, acyl glycerol phosphate acyltransferase; PA, phosphatidic acid; PAP, phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase; DGAT, acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase; SE, steryl ester; PKA, protein kinase A; ONM, outer nuclear membrane; INM, inner nuclear membrane; NR, nucleoplasmic reticulum; CCT

Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work NT, KY, MV, OK, AK, VM; Writing the paper NT; Editing and reviewing the original article LL, IKo, IKh; study concept or design NT, LL, IKo, IKh; project administrator, LL. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

All drawings were created by a team of authors using the Biorender program.

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project no. 23-15-00061).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.