1 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Jichi Medical University, 330-8503 Saitama, Saitama, Japan

2 Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, International University of Health and Welfare, 329-2763 Nasushiobara, Tochigi, Japan

3 Department of Cellular and Organ Pathology, Graduate School of Medicine, Akita University, 010-8543 Akita, Akita, Japan

§Present address: Department of Diagnostic Pathology, Edogawa Hospital, 133-0052 Tokyo, Japan

Abstract

Akt (v-akt murine thymoma virus oncogene homologue) is a well-known serine-threonine kinase that functions as a central node in various important signal cascades involved in cellular maintenance. Akt has also been implicated in oncogenic malignancies as evidenced by protein overexpression, activation and somatic aberration of components in the phosphoinositide-3 kinase-Akt pathway. As such, Akt is a potential target in cancer therapy. Akt is frequently activated in human cancer tissues not only due to aberrant upstream signaling, but also by genetic mutations in AKT itself. This leads to the aberrant activation of pathways downstream of Akt that regulate cell-cycle progression and metabolism as well as activation of transcription factors that promote oncogenesis. In this review, we summarize previous research on Akt, including the molecular mechanisms underlying Akt signal transduction, as well as its physiologic roles and the pathologic consequences when dysregulated. We also discuss the roles of dysregulated protein overexpression/activation, increases in gene copy number, single nucleotide polymorphisms and the network of non-coding RNAs that regulate this pathway, with a particular focus on lung carcinomas. Finally, we discuss strategies that might lead to more effective targeting of Akt for clinical cancer therapy.

Keywords

- Akt

- non-coding RNA

- lung carcinoma

- targeting therapy

The mammalian cell contains more than 600 kinases, each of which is estimated to phosphorylate 20 substrates on average [1]. The phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway orchestrates a number of downstream signaling pathways critical for both physiological and pathological processes, and as such are potential targets for cancer therapies [2, 3]. Akt is a critical node mediating the actions of diverse signals within the cell [2, 3]. Recently, a chemical phosphor-proteomics study identified 276 sites in 185 proteins that are potential sites of Akt phosphorylation [4].

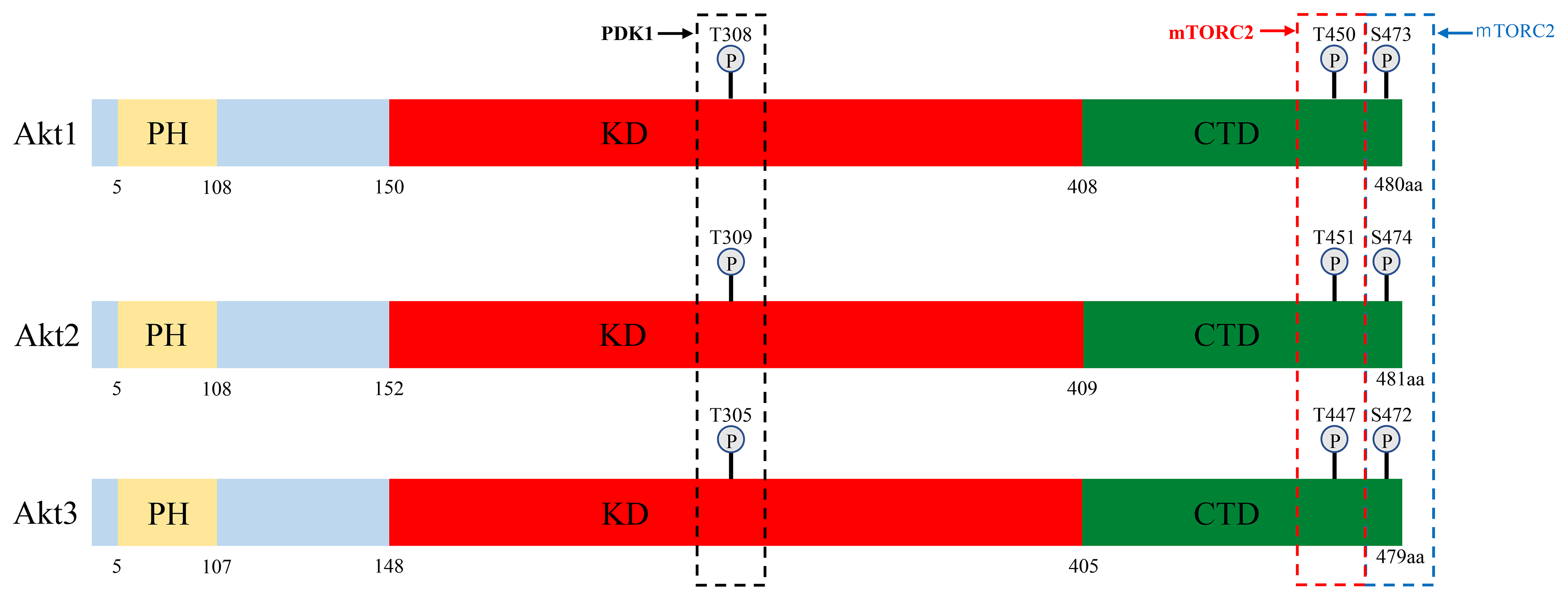

Akt, also called protein kinase B (PKB), belongs to the AGC (AMP/GMP kinases and protein kinase C) family of kinases and was originally identified as the cellular homologue of the murine thymoma oncogene v-Akt. Three 56-kDa mammalian isoforms have been cloned: Akt1 (PKB

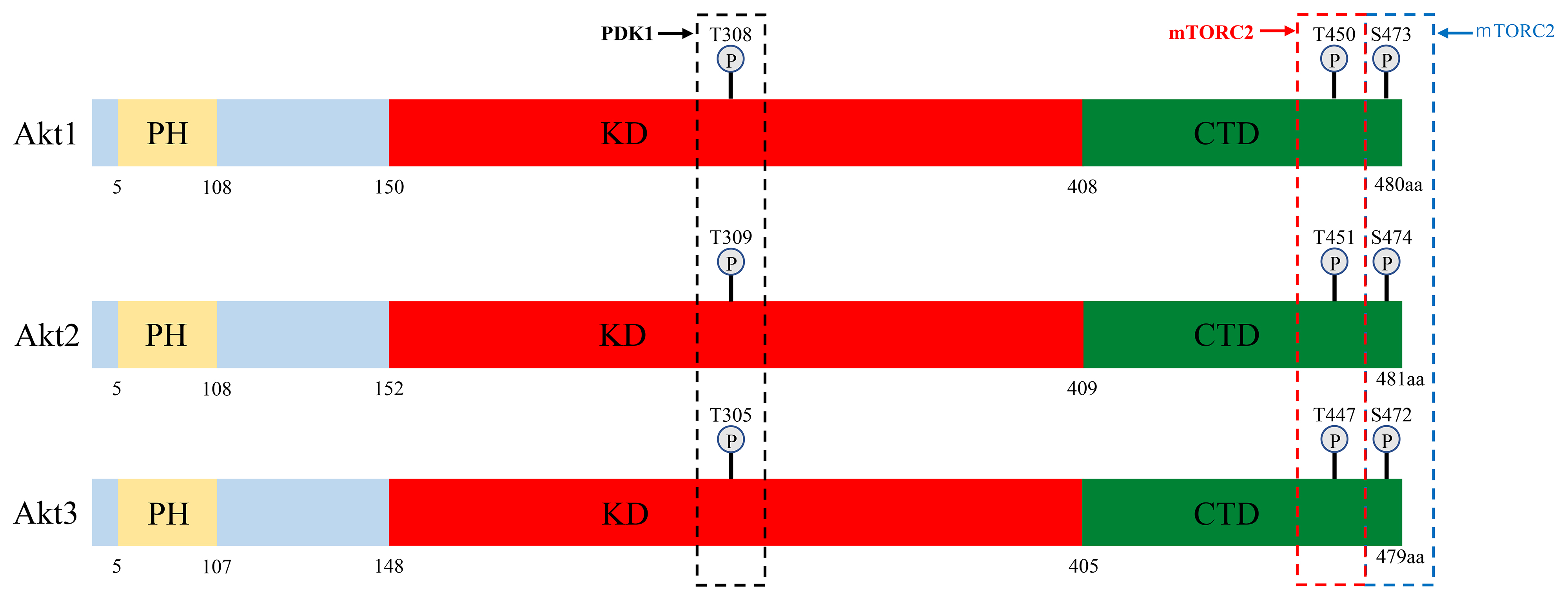

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the three Akt isoform structures. Akt protein has 3 domains: a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, kinase domain (KD) and C-terminal domain (CTD). The three conserved phosphorylation sites in Akt1, Akt2 and Akt3, and the kinases that phosphorylate these residues are shown. Akt, v-akt murine thymoma virus oncogene homologue; PDK1, 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1; PH, pleckstrin homology; KD, kinase domain; CTD, C-terminal domain; mTORC2, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2.

Akt1 is expressed ubiquitously at high levels and Akt2 and Akt3 are also more or less ubiquitously expressed, while Akt2 is expressed predominantly in insulin-responsive tissues such as fat, skeletal muscle and the liver [8]. Akt3 is expressed in the brain, the embryonic heart, the testis and the kidney [9].

All three isoforms function in critical cellular processes and appear to function redundantly, as no isoform-specific functions have been identified for most of the substrates [2]. However, the Akts have been reported to play different or even opposing roles in a variety of cancers [10, 11], which may have consequences for targeted therapies. For example, Akt1 and Akt3 are more deeply involved than Akt2 in cell proliferation, and Akt1 and Akt2 are more involved than Akt3 in the regulation of the cancer cell metabolism [11]. These functional segregations appear to arise partially from differences in tissue- and subcellular localization, thus determining the proteins each isoform can interact with [12]. Indeed, in our immunohistochemical analysis of lung carcinomas, levels of phosphorylated-Akt (p-Akt) in the nucleus were found to be dependent on Akt1 expression, while p-Akt activity in the cytoplasm was dependent on Akt2 expression [13]. Membrane localization of Akt1 and Akt2 is a general prerequisite for kinase activation, and Akt2 accumulates in the cytoplasm during mitosis, but localizes in the nucleus during muscle cell differentiation [14]. Moreover, in various types of human cancers, Akt1 and Akt2 appear to act in a reciprocal manner in cell cycle progression, migration and invasion [12]. For example, Akt1 promotes carcinogenesis in breast cancer and inhibits cell migration and invasion, whereas Akt2 inhibits carcinogenesis and promotes migration and invasion [15].

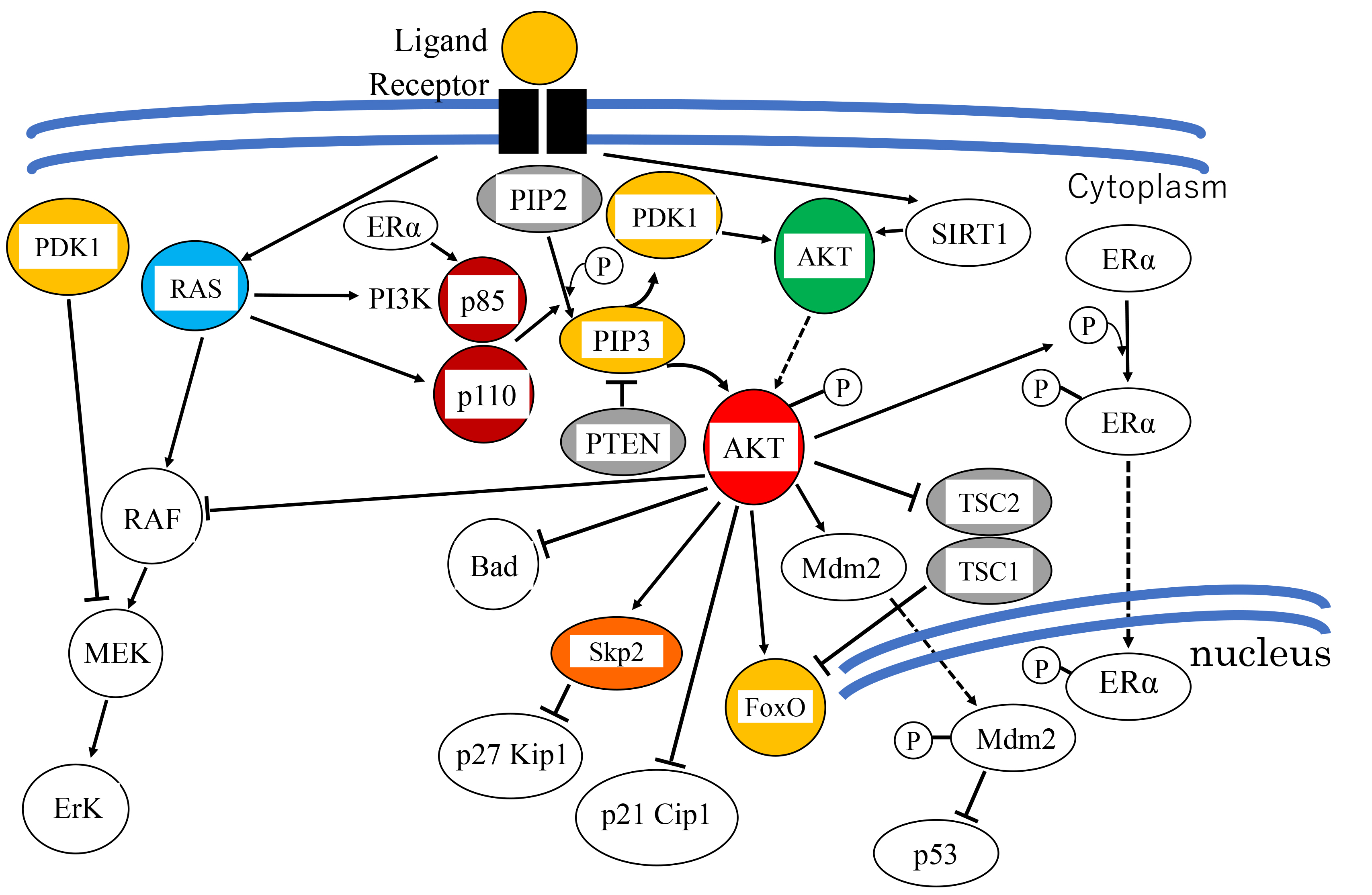

The mechanism of Akt activation has been well studied. In response to extracellular stimuli, receptor- or non-receptor tyrosine kinases activate PI3K, which in turn phosphorylates the second messenger phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bis-phosphate (PIP2), converting it into phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3). PIP3 then binds to Akt and 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1) and facilitates their re-localization to the membrane [2]. Co-localization of Akt with PDK1 results in the partial activation of Akt through phosphorylation at Thr308 (T308) (Figs. 1,2) [2]. Akt is then fully activated after additional phosphorylation at Ser473 (S473) by the putative kinase PDK2, which includes mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) and other kinases [2].

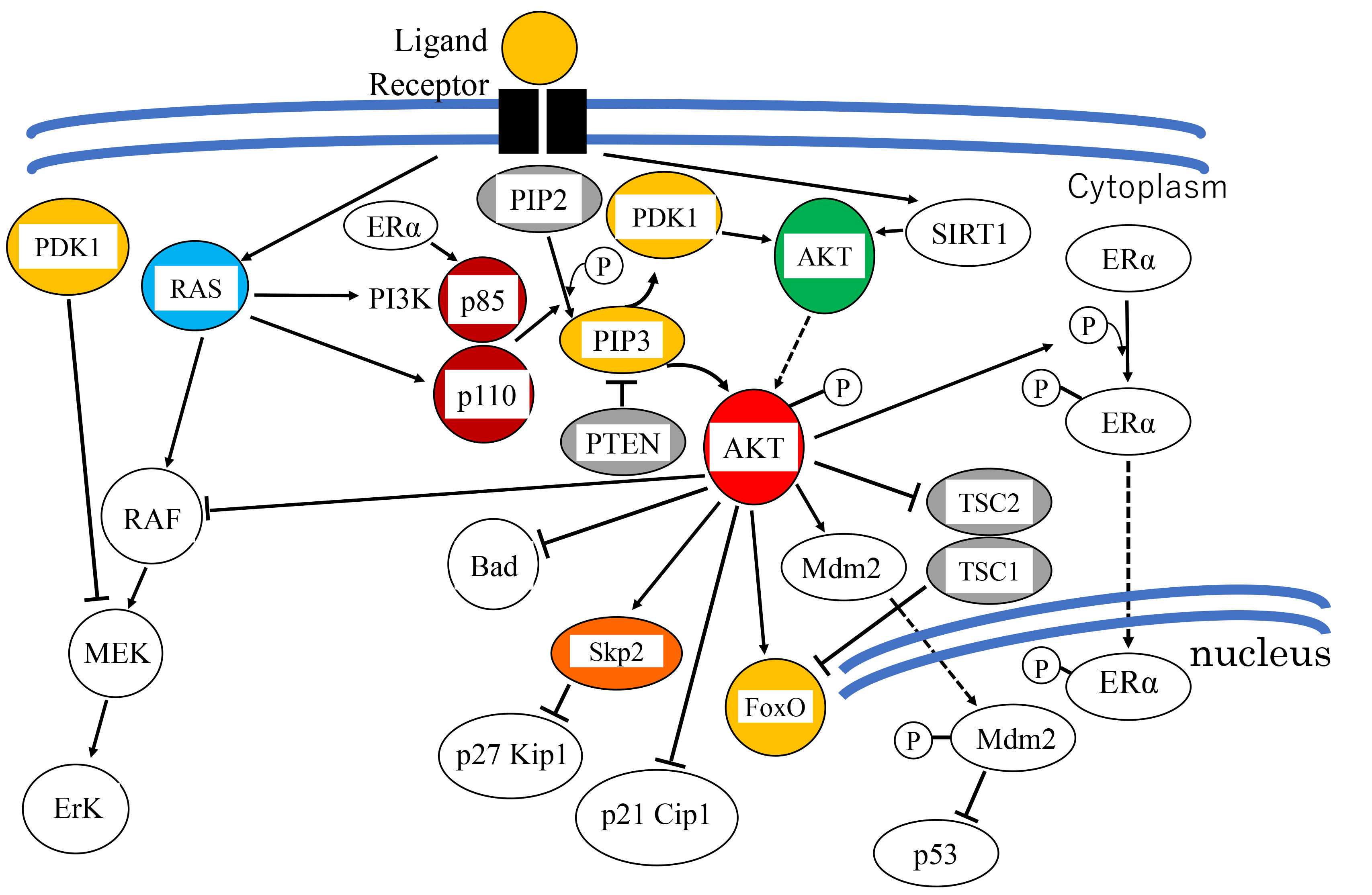

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Overview of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Receptor tyrosine kinase activated by growth factor transduces signals to PI3K. Activated PI3K phosphorylates PIP2 and converts it to PIP3, which recruits PDK1 and Akt to the cell membrane, and activates PDK1. Activated PDK1 subsequently phosphorylates Akt at Thr-308. Akt is fully activated by additional phosphorylation at Ser-473. In parallel, ER

Phosphorylation of Akt1, Akt2 and Akt3 by PDK1 and PDK2 at residues T308/S473, T309/S474 and T305/S472, respectively, is generally required for full activation. Phosphorylation of T308 alone leads to a ~400-fold increase in kinase activity, whereas phosphorylation at S473 provides additional activation of the kinase and regulates substrate selectivity in Akt1 [16]. Therefore, phosphorylation of Akt1 at T308 and S473 is widely used as an Akt activation marker in cancers [17]. A number of lipid phosphatases counter this activation by converting PIP3 back into PIP2. These include phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) and Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol-5-phosphatase (SHIP) [2] (Fig. 2). Moreover, dephosphorylation at T308 and consequent inactivation of Akt1 are catalyzed by protein phosphatase 2 (PP2A) and at S473 by PH domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP) [17, 18, 19].

Hence, the activity of Akt is determined by the balance among these various regulators.

After full activation, Akt translocates to specific subcellular compartments and activates various downstream substrates [20]. These various phosphorylation reactions have a range of effects on cellular functions. These include modulation of cell-cycle progression and anti-apoptotic activity, affecting cell proliferation and survival, as well as effects on metabolism, transcription factor activity and the invasiveness and metastasis of cancer cells [21]. Accordingly, the pathological role of Akt in cancer is also based on elevated Akt activity.

Activated Akt phosphorylates and inhibits the activity of the cell cycle inhibitors p27KIP1 [22] and p21CIP1 [23] at the transcriptional and the post-translational levels. First, Akt inhibits their translocation into the nucleus, preventing them from binding to cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) complexes [24]. For example, phosphorylation of p27 at Thr157 causes the relocation of p27 to the cytoplasm, thereby enabling the cyclin/CDK complex to escape inhibition by p27 and allow cell cycle progression. Subsequently, p27 becomes subject to ubiquitin-mediated degradation in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2) [22]. Second, Akt enhances the degradation of p27 through upregulation of S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (Skp2) mRNA levels. Skp2 is a ubiquitin ligase of the SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box) complex that tags p27 for degradation [25].

For p21, Akt degrades p53, a transcriptional activator of p21, through phosphorylation and activation of Mdm2 [26] (described later). In this manner, p21 is transcriptionally suppressed indirectly by Akt. Finally, Akt phosphorylates p21 at two different residues: Thr145 and Ser146. Phosphorylation at Thr145 results in the cytoplasmic localization of p21, thus promoting the cell cycle transition, whereas the phosphorylation at Ser146 enhances the stability of the protein and promotes binding with the cyclin/CDK complex and cell survival [25, 27].

Akt also induces estrogen-independent estrogen receptor (ER) transcriptional activity through phosphorylation of ER

Akt suppresses extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activity by direct binding with RAF, leading to its inactivation by phosphorylation at the regulatory residue Ser259 (Fig. 2) [31].

Other important targets for Akt include Bcl-2-associated death promoter (BAD) (a pro-apoptotic Bcl2 family member), caspase-9, Forkhead box-containing protein O1/3a/4 (FoxO1/3a/4) and Mdm2 [25, 32].

Phosphorylation of Bad at Ser136 inhibits apoptosis by preventing its binding to and inhibition of the anti-apoptotic molecule, Bcl-xL, and further prevents the alteration of mitochondrial membrane potential and cytochrome c release [24, 25]. Activated downstream of the Bcl-2 family is a cascade of caspase-family enzymes, initiated by caspase-9 [33]. Caspase-9 is activated by proteolytic cleavage of its pro-caspase form, which induces cytochrome c release. Akt phosphorylates caspase-9 at Ser196, leading to a conformational change that suppresses its proteolytic activity [24]. Therefore, Akt activation prevents both apoptotic processes.

The PI3K/Akt pathway also acts on other substrates during the G1/S phase transition. Akt regulates the level of cyclin D1 and Myc proteins by inhibiting their proteosomal degradation [25].

Moreover, Akt phosphorylates and inactivates the activity or promotes the degradation of FoxO1, 3a and 4, members of the forkhead family of transcription factors [32]. Akt phosphorylation of one of them, FoxO3a promotes its association with 14–3-3 proteins. This leads to the retention of FoxO3a in the cytoplasm, which abrogates its transcriptional activity as well as the expression of downstream genes that promote apoptosis, including Fas ligand [24].

Mdm2 is activated by Akt phosphorylation at Ser166 and Ser186. This leads to Mdm2 translocation from the cytoplasm into the nucleus where it interacts with p53, suppressing its transcriptional activity and promoting its degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [24].

Sirtuins, which are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent deacetylases, and adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribosyltransferases [34], play a role in a variety of cellular processes, such as angiogenesis, apoptosis, autophagy. This family of proteins function as silencers of gene expression by histone deacetylation and control ribosomal DNA recombination and repair, thereby promoting chromosomal stability and aging. Sirtuins also function in stress resistance, as well as energy efficiency during low-calorie situations and thus mediate the beneficial effects of dietary restriction on longevity [26]. Seven sirtuin isoforms have been identified (sirtuin (SIRT)1 to SIRT7), which vary in their tissue specificity, subcellular localization, and activity. Recent study has shown that SIRT1, SIRT3 and SIRT6 play an essential role in the regulation of Akt activation [35]. While SIRT1 deacetylates Akt to promote PIP3 binding and activation, SIRT3 controls reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated Akt activation and SIRT6 represses Akt at the transcriptional level. SIRT1 plays a role in DNA repair, metabolic processes and responses to cellular stress. However, in cancer, the role of SIRT1 is complex, on one hand promoting tumorigenesis by suppression of apoptosis, enhancing cell survival and promoting DNA repair, while on the other hand functioning as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting oncogenic signal pathways and inducing cellular senescence [34].

Glycogen synthase kinase 3

RBL2/p130 is a member of the retinoblastoma protein (RB) family that consists of RB1/p105, RBL1/p107, and RBL2/p130. The non-phosphorylated form of RBL2/p130 promotes apoptosis, but when physically bound and phosphorylated by Akt1, cell viability is enhanced and apoptosis is suppressed [37]. Indeed, in lung cancer cells, Akt phosphorylates RBL2/p130 at Ser941 and suppresses RBL2/p130 stability [38].

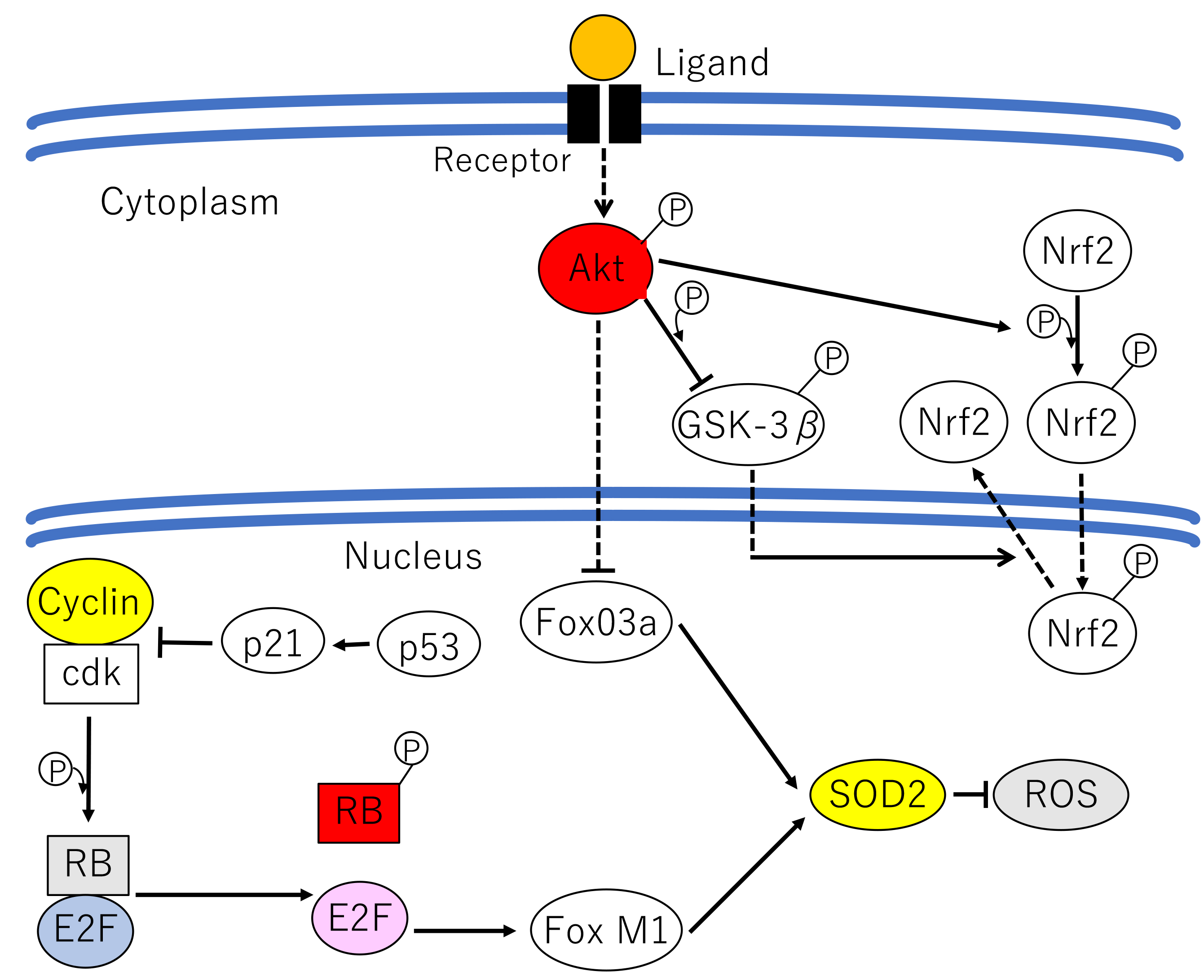

Akt is further involved in cell fate, such as reversible cell-cycle arrest (quiescence) or irreversible cell-cycle arrest (senescence), which is determined by a balance among proliferative signals. This involvement depends in part, on the transcriptional regulation of superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) [39, 40] (Fig. 3). SOD2 is responsible for detoxifying ROS, and is positively regulated at the transcriptional level by FoxO3a and FoxM1, downstream effectors of Akt and Rb, respectively [40, 41]. FoxO3a is phosphorylated by Akt, causing it to be sequestered in the cytoplasm and degraded by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway [42]. FoxM1 expression is suppressed by Rb which sequesters E2F, a transcription factor required for FoxM1 expression. Inactivation of these two FoxO factors results in the downregulation of SOD2 expression, leading to an increase in intracellular ROS [40]. Higher levels of ROS induce the DNA damage response which leads to cellular senescence. Thus, the redundant regulation of FoxO3a and FoxM1 by Akt and Rb, respectively, prevents the DNA damage response.

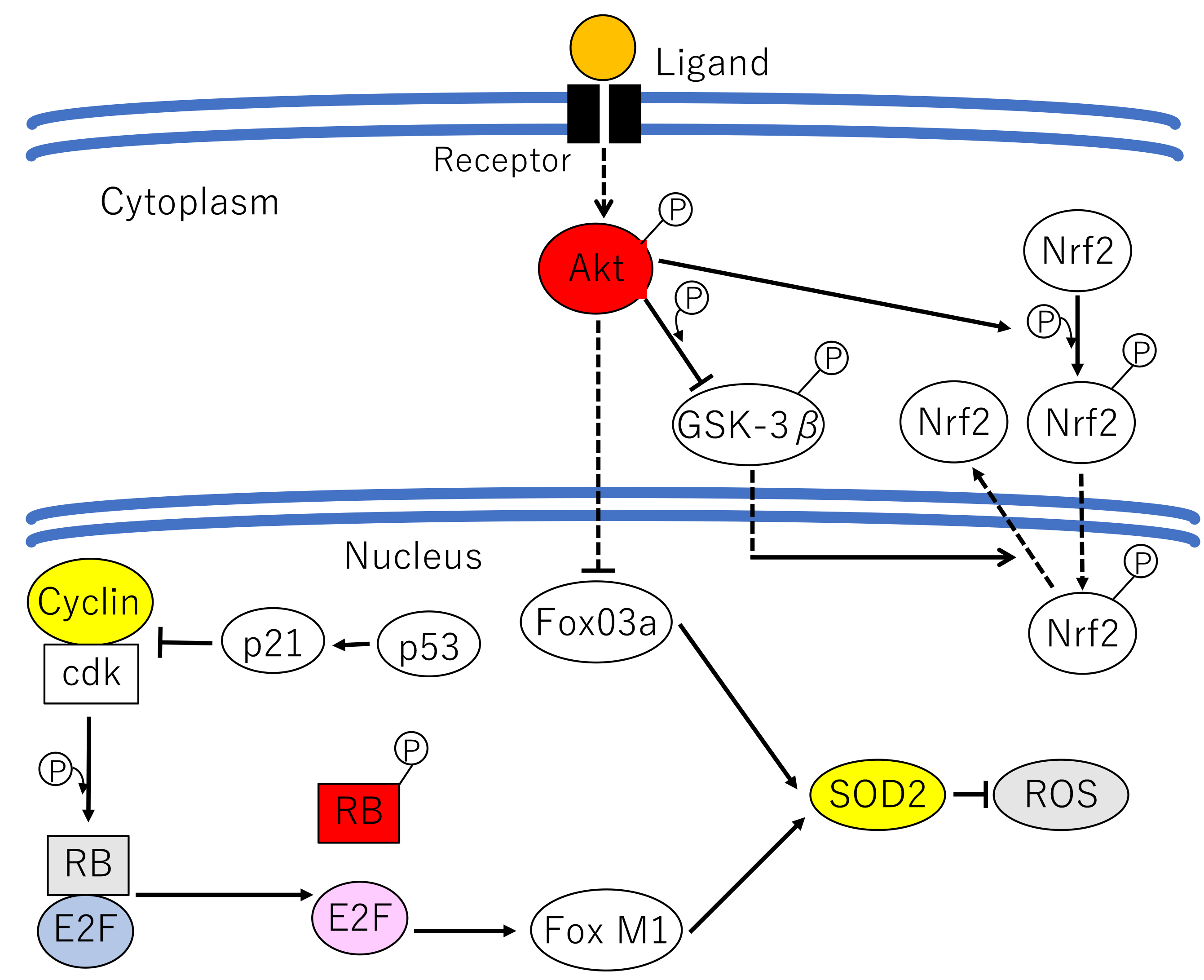

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. The mechanism determining cell proliferation, quiescence and senescence. In proliferating cells, Forkhead box M1 (FoxM1) is transcriptionally upregulated by the transcription factor E2F, which is released from retinoblastoma protein (RB). FoxM1 in turn transcriptionally upregulates superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) expression, which inhibits reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. In quiescent cells, the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21CIP1 is induced by 53, E2F is sequestered by active RB, and FoxM1 is not expressed. When Akt is inactive and FoxO3a is expressed, SOD2 expression is induced and ROS production is inhibited. Another pathway mediating an anti-senescence signal, including phosphorylation by Akt, involves translocation of nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) to the nucleus, which induces the expression of detoxification enzymes. Glycogen synthase kinase 3

Senescence is also regulated by p53. However, p53 exerts both pro-oxidant (aging/senescence) and antioxidant (anti-aging/anti-senescence) functions depending on the cell type and the extent of stimuli, depending on the differential regulation of p53 target genes (Fig. 3) [43]. Under high oxidative stress conditions or irreparable DNA damage, high and persistent levels of ROS activates p53. Activated p53 induces the expression of several pro-oxidant genes (PIG3, proline oxidase), and downregulates several antioxidant genes (e.g., PGM, NQO1), resulting in elevated intracellular ROS levels and cell death or senescence [44]. Furthermore, SOD2, a scavenger of oxygen radicals, is transcriptionally repressed by p53 [45]. On the other hand, mild stress conditions induce lower levels of p53 that induce the expression of several genes involved in cell-cycle arrest (e.g., p21CIP1), DNA repair, and the anti-oxidative response, thereby allowing cell survival. Representative antioxidant proteins promoted by p53 and lower ROS levels include the sestrins. These are a family of p53-inducible proteins required for the regeneration of peroxiredoxins, which are peroxidases and the reductants of peroxides, and thus suppress ROS levels. This response provides an antioxidant defense protecting cells from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced damage [43]. Glutathione peroxidase and the aldehyde dehydrogenase 4 family (ALDH4) also play a role in this response [44]. These are some of the ways by which p53 functions as antioxidant, lowering ROS levels and oxidative stress-induced DNA damage [43].

Another effect of p53 on aging/senescence is mediated partially by autophagy which stimulates the transcription of the DNA-damage regulated autophagy modulator 1 (DRAM1). Autophagy enhances cell survival, and suppression of autophagy leads to the accumulation of damaged molecules that induce ROS production, resulting in lower survival [26]. Through the modulation of ROS level, p53 contributes to both longevity and aging/senescence (Fig. 3) [43]. This p53 is, at least partially, regulated by Akt through Mdm2 (Chapter 1.3.1).

The Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1- (Keap1-) nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), is closely associated with aging/senescence and controls the transcription of multiple antioxidant enzymes. The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway is modulated by a complex regulatory network, including Akt [46]. Anti-senescence signals facilitate the release of Nrf2 from Keap1, allowing its translocation to the nucleus where it induces expression of various antioxidant and detoxification enzymes [47]. GSK3

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death, with more than 1.8 million deaths estimated globally [48]. Non-small cell carcinoma (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 80% of all lung cancers [49], and its treatment has improved dramatically by the availability of biomarkers and our understanding of driver genes, allowing patient stratification and the application of precision medicine [50].

Molecular targeted therapies for lung cancer began in 2001 with an inhibitor against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Since that time, the two decades have seen the remarkable development of therapies directed against a variety of other “druggable” molecular targets [50]. Today, these therapies include inhibitors of EGFR, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), rearranged during transfection (RET), v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (BRAF), v-ros UR2 sarcoma virus oncogene homolog 1 (ROS1), Neurotrophic Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (NTRK), MET proto-oncogene (MET), and KRAS, which are employed as first line therapies for molecularly defined populations [50]. Unfortunately, however, only 25% of patients benefit from these therapies and chemoresistance develops almost inevitably [51]. Furthermore, for the remainder of cancers that do not have identified oncogenic drivers, treatment options are limited to conventional chemotherapy. The introduction of immunotherapy-based treatments in the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) by PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors has been notable since, unlike adenocarcinoma (AC), treatment options for SCC have been otherwise limited. Pembrolizumab has shown a higher objective response rate and a longer duration of response than conventional chemotherapy [52]. However, even this therapeutic modality gradually encounters resistance, indicating the further need for novel targeted agents. Accordingly, there remains a focus on the more classical target Akt for the treatment of lung cancer of various histological types [13, 53].

Aberrant activation of the Akt pathway in many cancers is due to AKT1, AKT2 or AKT3 gene amplification, as seen in gastric, prostatic, lung, ovarian and breast carcinomas as well as melanoma [54, 55, 56]. There are also examples of Akt pathway activation that do not involve gene amplification [57].

Akt1 mRNA has been observed to be overexpressed in 16% of all malignancies and in 13.7% of lung carcinoma [58]. Akt2 mRNA was overexpressed in 14.4% of malignancies and in 36.8% of lung carcinomas [59]. Generally, activation of Akt1 and Akt2 is more frequent in cancers of high grade and in advanced stage and is associated with metastasis, radioresistance and worse prognosis, including in lung carcinomas [57, 60].

Akt3 mRNA was overexpressed in 5.3% of all malignancies and in 5.6% of lung carcinomas (Table 1, Ref. [54, 55, 56, 58, 59, 61, 62, 63, 64]) [61]. Selective activation of Akt3 is well known in melanomas and is observed in up to 60% with increased expression during cancer progression and metastasis [65].

| mRNA overexpression | References | ||

| Akt1 | 16% in all malignancies, 13.7% in lung cancer | [58] | |

| Akt2 | 14.4% in all malignancies, 36.8% in lung cancer | [59] | |

| Akt3 | 5.3% in all malignancies, 5.6% in lung cancer | [61] | |

| Gene amplification | |||

| AKT1 | 0.9% in all malignancies, 1.8% in lung cancer | [54] | |

| AKT2 | 1.7% in all malignancies, 2.8–3.5% in lung cancer | [55] | |

| AKT3 | 2.7% in all malignancies, 3.4–3.8% in lung cancer | [56] | |

| Mutation (point mutation and insertion/deletion) | |||

| AKT1 | 0.9–1.6% in all malignancies, 0.6–0.8% in lung cancer | [62] | |

| AKT2 | 0.6% in all malignancies, 0.8–1.1% in lung cancer | [63] | |

| AKT3 | 0.8–0.9% in all malignancies, 1.1–1.2% in lung cancer | [64] | |

In the literature, there are many reports of AKT copy number increases in cancer, and thus, the AKTs are generally considered to be oncogenes. AKT1 gene amplification has been found in sporadic cases in 0.9% of all malignancies and in 1.8% of lung cancer [54] (Table 1). Amplification of AKT2 has been more frequently observed than AKT1 in 1.7% of all malignancies and, and is observed in lung cancer (2.8–3.5%) [55]. In lung carcinomas, our previous study by fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis (FISH) revealed amplification of AKT1 and/or AKT2 in approximately 7% of the cases [53]. Amplification of AKT3 was reported in 2.7% of all malignancies and in 3.4–3.8% of lung carcinomas [56]. In our study of lung carcinoma, we did not find cases of AKT3 gene increases by gene amplification, but we did find increases by polysomy in 40% of the cases [13].

The substitution of the glutamic acid at residue 17 to lysine (E17K) point mutation in AKT1 is a somatic, activating mutation that contributes to growth factor-independent membrane translocation of Akt and higher phosphorylation levels. This mutation has been observed in lung, breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, esophageal and colorectal carcinomas as well as melanoma or meningioma (Table 1) [62]. However, it occurs at a low frequency (1% across all solid tumors) [62], comprising 2 of 36 cases (0.56%) of SCC and zero among 53 cases of AC in lung carcinoma [66, 67]. Cancers harboring AKT1-E17K are peculiar in that they are resistant to allosteric Akt inhibitors, but sensitive to ATP-competitive inhibitors [2].

Insertion/deletion mutations (indels) that activate AKT1/2 have been found in breast, prostate and renal carcinomas, for example T65_I75dup and P68_C77dup [67]. The presence of AKT1 P68_C77dup in breast carcinoma MCF10A cells causes a higher level of Akt1 phosphorylation (T308/S473) and increased phosphorylation of downstream effectors compared with the E17K. However, this type of mutation has not been reported in lung carcinoma [67].

Overall, AKT1 point and indel mutations have been found in 0.9–1.6% of all malignancies, and in 0.6–0.8% of lung carcinomas [62]. Mutations in AKT2 have been found in 0.6% of malignancies, and in 0.8–1.1% of lung carcinoma [63]. Mutations in AKT3 have been described in 0.8–0.9% of all malignancies, and 1.1–1.2% of lung carcinomas (Table 1) [64].

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the AKTs have been associated with differences in cell survival and haplotypic variations of the AKT1 gene have been associated with resistance to apoptosis and DNA damage [68]. Therefore, particular SNPs are considered to be involved in carcinogenesis and determine a predisposition to and/or to be a prognostic indicator of lung carcinoma [69].

We obtained novel SNP data from whole-blood DNA in a Japanese population cohort to reveal the associations among AKT1 SNPs, cancer predisposition and smoking behaviors [69]. In that study, AKT1 data from the whole-genome genotyping of 999 samples were extracted and analyzed for approximately 300,000 SNP markers. We found that the T/T variant of a previously undescribed locus, rs2498794 SNP, located in the fifth intron region of AKT1, was significantly associated with longer smoking duration. Furthermore, among those cases with longer smoking duration, this SNP showed significant association with increased incidence of all cancers [69]. Conversely, however, among those cases having a shorter smoking duration, this T/T variant was related to a lower susceptibility to cancer.

Next, we evaluated the dysregulation of Akt, gene increases and examined the correlations among protein overexpression, activation and AKT copy number in lung carcinoma. Results were as follows.

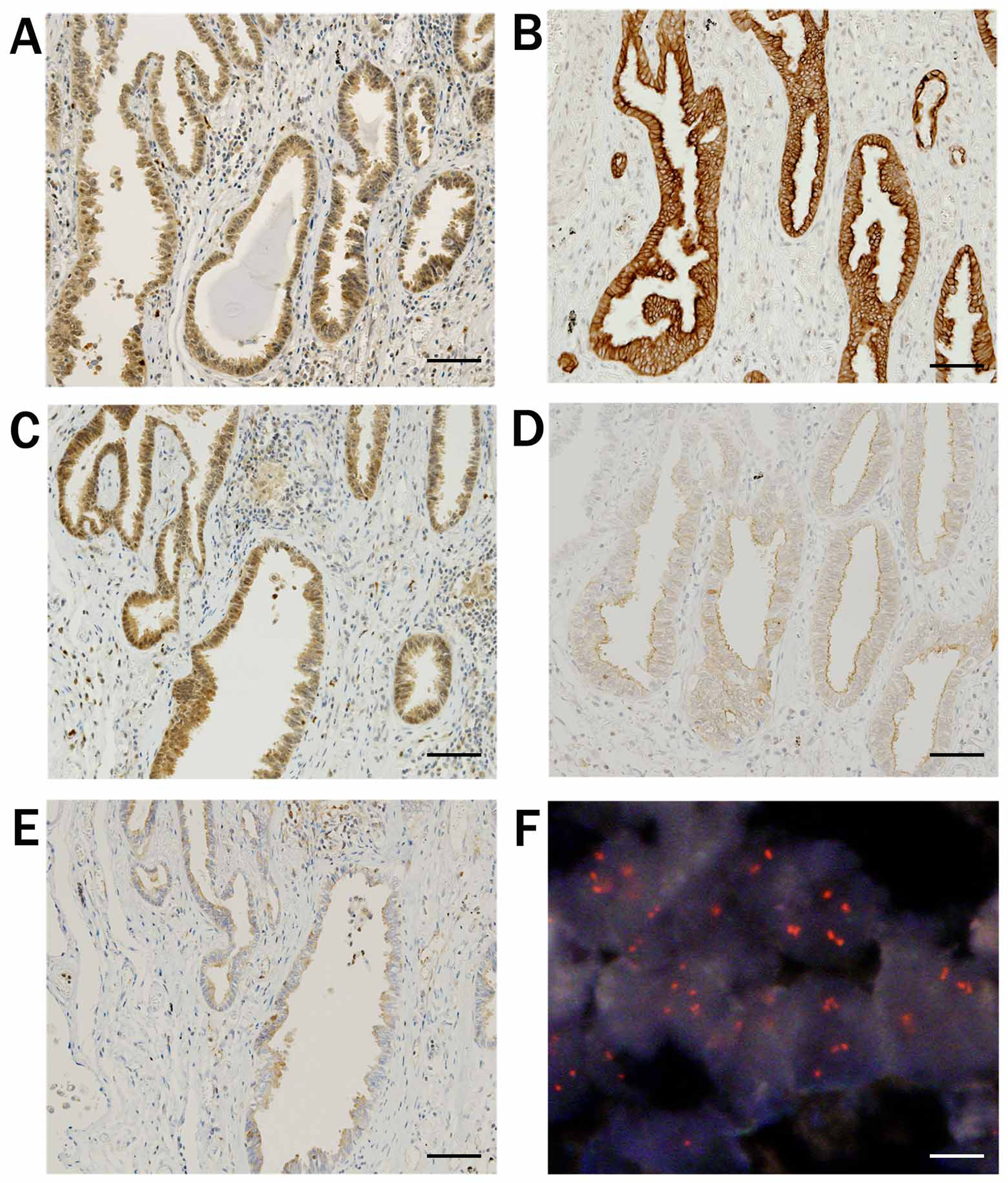

We examined the expression/activation of total Akt protein and its isoforms using antibodies against Akt1, Akt2 and Akt3, as well as pan-Akt (T-Akt) and p-Akt in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue (FFPE) from lung carcinomas.

Our overall results revealed overexpression of T-Akt in 61.1% and activation (positive for p-Akt staining) in 42.6% of total cases (Table 2, Ref. [13]). Among T-Akt-positive tumors, 62% exhibited positive p-Akt expression (Akt activation), whereas none of the T-Akt-negative tumors were positive for p-Akt. Thus, T-Akt overexpression is a prerequisite for activation. Akt1, Akt2 and Akt3 isoforms were positive in 47.2%, 40.7% and 23.1% of the cases, respectively. Except for large cell carcinoma (LCC), which comprised few cases overall, expression of T-Akt, Akt2 and Akt3 were frequently observed in small cell carcinoma (SmCC), but those of p-Akt and Akt1 were more frequently observed in SCC. These overall results are presented in Fig. 4 (Ref. [13]) and Table 2 [13, 53].

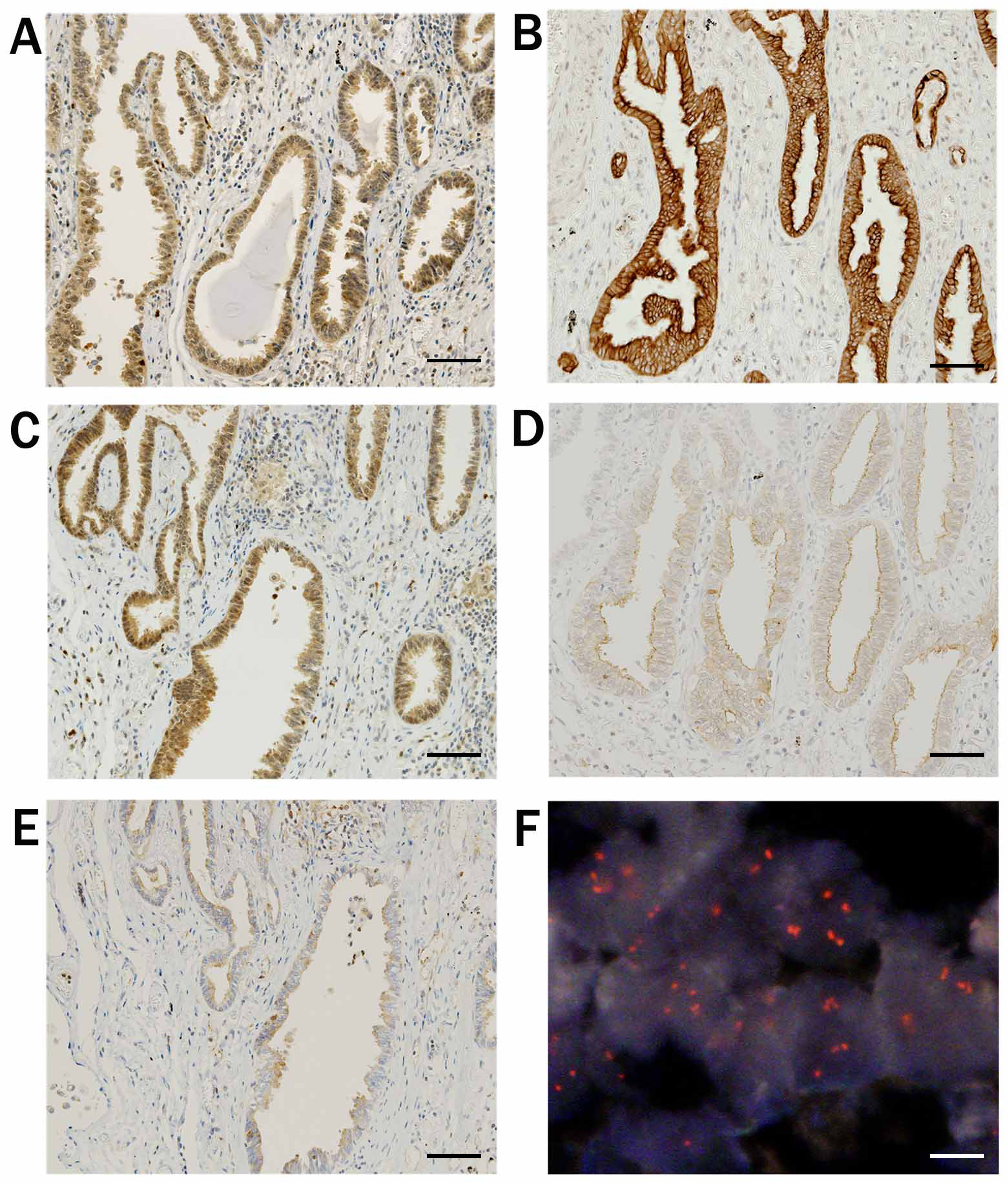

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Results of immunohistochemical staining and FISH analysis. A case of adenocarcinoma. (A) Staining for total-Akt exhibited nuclear/cytoplasmic positivity. (B) Staining for phosphorylated-Akt, and (C) for Akt1 exhibited nuclear/cytoplasmic positivity. (D) Staining for Akt2 and (E) for Akt3 exhibited cytoplasmic positivity. (F) FISH revealed amplification of AKT1. Black scale bar indicates 100 µm and white scale bar indicates 10 µm. Reproduced and modified from “Diverse involvement of isoforms and gene aberrations of Akt in human lung carcinomas” by Dobashi et al. [13], Cancer Science. 2015; 106: 772–781. Copyright John Wiley & Sons Limited with permission and modified.

| IHC | Histology (cases) | ||||||

| AC | SCC | LCC | NSCLC | SmCC | Total | ||

| (48) | (37) | (5) | (90) | (18) | (108) | ||

| Positive cases (%) | |||||||

| T-Akt | 25 (52) | 24 (65) | 4 (80) | 53 (59) | 13 (72) | 66 (61) | |

| p-Akt | 17 (35) | 18 (49) | 3 (60) | 38 (42) | 8 (44) | 46 (43) | |

| Akt1 | 22 (46) | 18 (49) | 4 (80) | 44 (49) | 7 (39) | 51 (47) | |

| Akt2 | 16 (33) | 16 (43) | 2 (40) | 34 (38) | 10 (56) | 44 (41) | |

| Akt3 | 9 (19) | 7 (19) | 2 (40) | 18 (20) | 7 (39) | 25 (23) | |

| FISH | Histology (cases) | ||||||

| AC | SCC | LCC | NSCLC | SmCC | Total | ||

| (43) | (33) | (5) | (81) | (14) | (95) | ||

| Positive cases (%) | |||||||

| AKT1 | A | 1 (2.3) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (20.0) | 3 (3.7) | 1 (7.1) | 4 (4.2) |

| H | 2 (4.7) | 4 (12.1) | 1 (20.0) | 7 (8.6) | 1 (7.1) | 8 (8.4) | |

| L | 8 (18.6) | 6 (18.2) | 2 (40.0) | 16 (19.8) | 2 (14.3) | 18 (18.9) | |

| AKT2 | A | 1 (2.3) | 1 (3.0) | 0 | 2 (2.5) | 1 (7.1) | 3 (3.2) |

| H | 2 (4.7) | 5 (15.2) | 1 (20.0) | 8 (9.9) | 3 (21.4) | 11 (11.6) | |

| L | 4 (9.3) | 6 (18.2) | 1 (20.0) | 11 (13.6) | 3 (21.4) | 14 (14.7) | |

| AKT3 | A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| H | 3 (7.0) | 3 (9.1) | 1 (20.0) | 7 (8.6) | 3 (21.4) | 10 (10.5) | |

| L | 9 (20.9) | 11 (33.3) | 2 (40.0) | 22 (27.2) | 6 (42.9) | 28 (29.5) | |

Numbers represent those of the cases for each category. Abbreviations. FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis; IHC, Immunohistochemistry; AC, adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; LCC, large cell carcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell carcinoma; SmCC, small cell carcinoma; T-Akt, total-Akt; p-Akt, phosphorylated-Akt; AKT1, AKT2, AKT3, numerical status of genes; A, amplification; H, high-level polysomy; L, low-level polysomy. Reproduced from “Diverse involvement of isoforms and gene aberrations of Akt in human lung carcinomas” by Dobashi et al. [13], Cancer Science. 2015; 106: 772–781. Copyright John Wiley & Sons Limited with permission, and modified.

Although the expression of T-Akt, p-Akt, Akt1 and Akt2 isoforms was observed both in the cytoplasm and the nucleus, Akt3 expression was observed almost exclusively in the cytoplasm.

Clinicopathologically, a statistically significant correlation between Akt activation and lymph node metastasis was detected (p = 0.033).

Although smoking is widely known to be an etiologic factor for lung carcinomas [70], and frequent Akt expression and activation was observed in smokers, we could not confirm a statistically significant association.

The status of AKT1, AKT2, AKT3 gene number were quantitatively evaluated by FISH analysis and classified into 4 categories: [53]. Our overall results are presented in Fig. 4 and Table 2 and described as follows.

We observed amplification of AKT1 in 4.2% and of AKT2 in 3.2% of total cases. Increases in AKT1 or AKT2 gene number by polysomy (i.e., increase of chromosomes 14 or 19) were observed in 27.4% and 26.3% of the cases, respectively. Thus, amplification of the AKT genes was not frequent, whereas polysomy was rather frequent. We did not observe co-amplification of AKT1 and AKT2, but all of the cases exhibiting amplification of AKT1 or AKT2 also had polysomy of other chromosome(s) (Table 2) [13, 53].

AKT1 and/or AKT2 gene increases by amplification or high-level polysomy were found in 22.1% of the total cases, and this subset was characterized by the overexpression/activation of Akt. Therefore, carcinomas of this subset are likely to be driven by Akt and would be good candidates for Akt-targeted therapies.

Increases in AKT3 were observed in 40.0% of the total cases by polysomy of chromosome 1, and not by gene amplification [13].

With regards to histological type, AKT2 or AKT3 gene gains by amplification or high level polysomy were more frequent in SmCC, whereas AKT1 gene gains was more frequent in SCC and LCC. Additionally, AKT2 gene gains were more frequently observed in smokers, whereas AKT1 gains were more prevalent in non-smokers [53].

By combining IHC and FISH results, we obtained several novel insights as follows.

First, all carcinomas harboring amplification or high level polysomy of AKT1 and/or AKT2 showed overexpression of T-Akt and the respective isoform, as well as Akt activation. However, AKT3 gene increases were not always accompanied by overexpression of Akt3 protein. Thus, increased AKT3 gene may not be fully transcribed or translated and may be nonpathogenic [13].

Second, increases in AKT1 and AKT2 gene number were mutually correlated (p

Third, p-Akt staining, in particular, nuclear accumulation, was found in up to 83% of EGFR-mutated carcinomas [71]. Since Akt is known to translocate to the nucleus when stimulated and phosphorylated [72], Akt may be constitutively activated downstream of mutated EGFR. Although responsiveness to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) gefitinib has been reported to be predicted by Akt activation [73], nuclear localization was not correlated with AKTs gene status, clinicopathologic factor or overall survival in our study [53].

The literature details numerous examples of Akt protein dysregulation and AKT gene aberration, but there is no clear consensus as to their clinicopathological significance. In our studies, we have reported the following.

First, expression of p-Akt (p-Ser473) and Akt2 as measured by IHC was correlated with lymph node metastasis (p = 0.037 and 0.048, respectively) [13, 53]. Since an increase in AKT2 gene number was correlated with Akt2 and p-Akt expression, this increase may be involved, even indirectly, with nodal metastasis [13]. This result is consistent with previous studies reporting that AKT2-transfected cells were more metastatic due to enhanced cell motility [15, 57].

Second, an increase in AKT1 gene number by amplification or high level polysomy was correlated with larger tumor size (pT, p = 0.0430), suggesting the involvement of these aberrations in advanced stage [13]. Increases in AKT2 gene number showed a similar trend, but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0590).

Reports looking at the association of p-Akt1 (p-Thr308) with patient prognosis gave mixed results, with some reports indicating poorer prognosis [74] and others reporting better prognosis [73, 75]. Data of 10,010 NSCLC patients in TCGA showed that an increase in AKT2 gene number was associated with poorer prognosis with statistically significant differences seen for disease-specific, and overall survival (p = 0.0299,

Therefore, numerical alterations in AKT gene numbers could be indicators for clinical behavior and better inform the application of coordinated molecular targeted therapies against lung carcinomas.

More than 98% of the human genome is non-coding for proteins, with the remaining 2% encoding approximately 21,000 distinct proteins [79]. Non-coding, regulatory RNAs (ncRNAs) can be classified into long ncRNAs (lncRNAs) of

Numerous miRNAs have been described that are involved in Akt-mediated pathways [17, 83]. To investigate the potential involvement of miRs in the AKT pathway, we employed by microarray analysis to look for miRs that might act at or downstream of increased AKT1 and AKT2 gene number in lung carcinomas. This analysis revealed 28 miRs which were up-regulated in both the AKT1+ (cases showing only AKT1 gene copy number increase [CNI]) and AKT2+ (cases showing only AKT2 CNI) groups, including all miR-200 family members (miR-141, miR-200a/b/c, and miR-429), which are known to negatively regulate cancer metastasis and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [92].

When expression of miR-200a/b/c was analyzed by qRT-PCR in the AKT1+ and AKT2+ groups, no significant differences were found when viewed as a whole. However, when subdivided into AC and early stage carcinomas (pathological stage [pStage] I/II), the expression of miR-200a was significantly higher in the AKT2+ group compared with the AKT1+ group (p = 0.0334 and p = 0.0239, respectively). Thus, AKT2 may enhance or AKT1 may suppress miR-200a expression in a histological- or stage-specific manner [93].

In general, the miR-200 family is thought to be partially suppressed by Akt2, thereby E-cadherin expression is suppressed, and EMT, invasion, and metastasis are promoted [94]. Also, the miR-200 family is often suppressed in cancers of more aggressive subtype or more advanced stage [95]. Consistently, our previous study showed that overexpression of Akt2 was positively correlated with lymph node metastasis [13]. Therefore, suppression of miR-200a by enhanced Akt2 does not seem to occur in AC and in carcinomas of pStage I/II [93]. Although the mechanism of this miR-200a regulation in defined subsets remains to be elucidated, a possible switch mechanism was suggested previously in the model of metastasis. The idea is that miR-200 is downregulated at the initial stages of oncogenesis leading to the acquisition of a more invasive phenotype, but is upregulated at a later stage, which re-epithelializes metastatic cells and leads to tumor nodule formation at the site of metastasis [96]. Therefore, miR-200a upregulation by AKT2 may occur in a transient and stage-specific manner during tumor nodule formation. Alternatively, upregulation of miR-200a by AKT2 may function as a negative feedback mechanism to restrain the invasive capability of cells induced by AKT2. Supporting this hypothesis, 28 miRs that were upregulated in both the AKT1+ and AKT2+ groups included miR-7 and miR-375, each of which is reported to suppress the PI3K/Akt pathway. Thus, the high expression of these miRs could serve as a safeguard mechanism against hyperactivation caused by increased AKT gene number [97, 98].

We next looked for potential targets of miR-200a in these cancer subsets by IHC, focusing on its known target proteins; Zinc finger E-box binding protein 1 (ZEB1), beta-catenin [99], Erythropoietin producing hepatoma receptor-A2 (EphA2) [100], PTEN [101], and yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) [102]. E-cadherin was also analyzed since its expression is directly inhibited by ZEB1 [103]. ZEB1 has been known to be negatively regulated by miR-200a, but on the other hand, it also negatively regulates E-cadherin. As expected, ZEB1 was inversely (

| All cases | AC | p-stage I/II | SCC | non-AC | p-stage III | |

| E-cadherin | 0.345* | 0.344 | 0.331 | 0.425 | 0.310 | 0.382 |

| p = 0.0332 | p = 0.0691 | p = 0.0749 | p = 0.1237 | p = 0.0758 | p = 0.0955 | |

| b-catenin | 0.297 | 0.277 | 0.303 | 0.337 | 0.310 | 0.307 |

| p = 0.5496 | p = 0.2686 | p = 0.1551 | p = 0.3398 | p = 0.7561 | p = 0.8502 | |

| EphA2 | –0.386 | –0.496* | –0.547* | –0.242 | –0.290 | –0.333 |

| p = 0.1201 | p = 0.0470 | p = 0.0196 | p = 0.1062 | p = 0.1742 | p = 0.0914 | |

| ZEB1 | –0.417* | –0.405 | –0.257 | –0.329* | –0.510* | –0.606* |

| p = 0.0372 | p = 0.0667 | p = 0.0677 | p = 0.0125 | p = 0.0193 | p = 0.0233 | |

| PTEN | –0.288 | –0.271 | –0.201 | –0.502 | –0.388 | –0.497 |

| p = 0.1762 | p = 0.0776 | p = 0.2586 | p = 0.1556 | p = 0.2752 | p = 0.0628 | |

| YAP1 | 0.046 | 0.106 | 0.064 | 0.167 | 0.148 | 0.070 |

| p = 0.7758 | p = 0.6711 | p = 0.7632 | p = 0.6374 | p = 0.4970 | p = 0.7944 |

Immunohistochemical scores of respective proteins and miR-200a expression level were compared by Spearman’s rank correlation test. r,

EphA2 has been reported to be overexpressed and correlated with aggressive behavior and poor prognosis in NSCLC [105]. miR-200a has been shown to suppress EphA2 by direct interaction with its mRNA 3′-untranslated region (UTR) [100]. Therefore, it is not surprising that increased AKT2 upregulates miR-200a, which in turn suppresses EphA2 in AC and early stages of carcinomas as a safeguard mechanism to counter the proliferative, invasive and subsequent metastatic capability elicited by EphA2 [106].

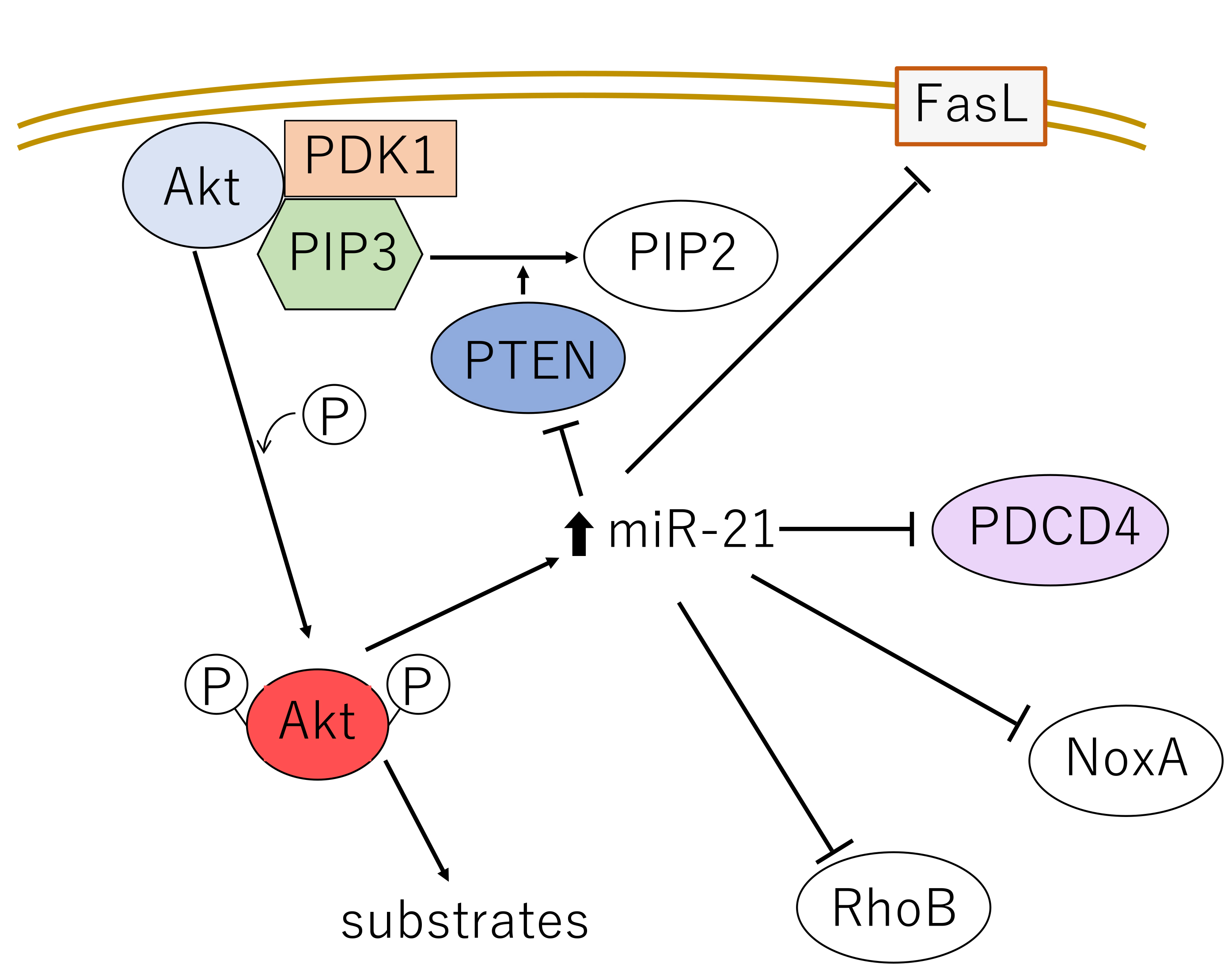

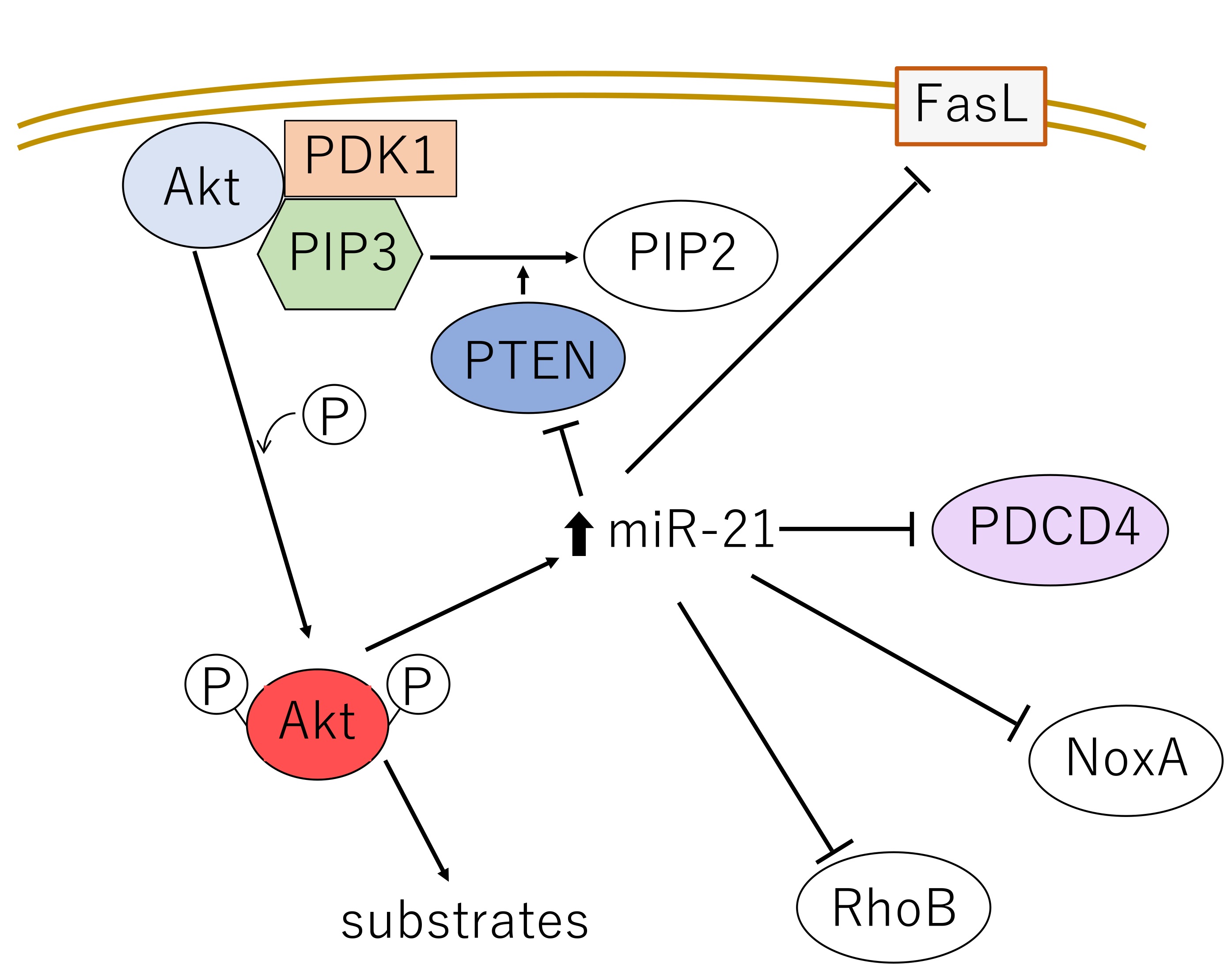

It is widely known that many kinds of cancers overexpress miR-21, including those of the lungs [107, 108]. The effect of miR-21 on oncogenesis is mediated by multiple pathways and has been intensively studied. It has been shown that miR-21 suppresses radiosensitivity and apoptosis via inhibition of programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) [82, 109] and also induces autophagy as a pro-survival mechanism [107] (Fig. 5). In addition, miR-21 inhibits expression of the pro-apoptotic factor Nuclear orphan X-linked apoptosis protein (NOXA), whose function has been correlated with cell death in gastric carcinoma [110]. Simultaneously, miR-21 reduces expression of the tumor suppressor Ras homolog member B (RhoB), thereby promoting proliferation and invasiveness of colon carcinoma cells [111]. Based on these results, miR-21 has been explored as a target of anti-cancer agents such as curcumin and curcumol [107].

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. The major signaling pathways mediating growth stimuli from the cell surface through Akt and miR-21. FasL, Fas ligand; PDCD4, programmed cell death 4; NoxA, NADPH oxidase activator protein A; RhoB, Ras homolog member B.

miR-21 positively regulates Akt in an indirect manner by suppressing PTEN expression and thereby promotes proliferation, metastasis and resistance against chemoradiotherapy in NSCLC [112]. PTEN normally dephosphorylates PIP3, which is required for the recruitment of the Akt-activating kinase PDK1 (Fig. 5) [82]. At the same time, miR-21 is upregulated by Akt, and therefore they function in a mutual, positive feedback loop. This functional interaction between Akt and miR-21 can modulate oncogenesis via multiple pathways.

Akt induces the rapid upregulation of miR-21, which targets and inhibits Fas ligand (FasL), PTEN, programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4), NADPH oxidase activator protein A (NoxA) and RhoB. These signaling events coordinate to protect mitochondrial damage.

Akt is positively regulated by numerous miRNAs in an indirect manner, and negatively regulated both directly and indirectly. To date, examples of miRs directly regulating Akt in a positive manner have not been found. Most regulation of Akt by miRs, whether positive or negative, applies to all three Akts. However, there also exists direct and isoform-specific regulation of the Akts. For example, miR-409 and miR-374b specifically target Akt1, miR-103a-3p and miR-124-3p target Akt2, let-7a targets both Akt2 and 3, and miR-181a-5p and miR-489 target Akt3 [83]. Representative miRs among these are as follows, categorized by their mode of function (Table 4, Ref. [17, 82, 83, 84, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130]).

| Mode of effect | microRNA | Target | Biological function | Cancer | References |

| Positive indirect | miR-21 | downregulates PTEN through 3′-UTR | enhances proliferation, invasion, suppress apoptosis | various cancers | [82, 83, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112] |

| miR-221/222 | downregulates PTEN through 3′-UTR | promote cancer stem-like cell property | NSCLC, HCC, glioma, gastric cancer | [113] | |

| miR-200c-3p | downregulates PTEN through 3′-UTR | enhances progression | NSCLC cells | [114] | |

| miR-19b | downregulates protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), which dephosphorylates Akt | promotes cell proliferation | NSCLC cells | [115] | |

| miR-103a-3p | suppresses PTEN and enhances predominantly Akt2 | enhances proliferation | NSCLC cells | [83] | |

| Negative direct | miR-409-3p | destabilizes Akt1 post transcriptionally | suppresses proliferation | breast, cervical cancer, lung AC cells | [128] |

| miRNA-374b | destabilizes Akt1 posttranscriptionally | suppresses proliferation | colorectal cancer cells, NSCLC | [17, 118, 119] | |

| miR-124-3p | downregulates Akt2 through 3′-UTR | sensitizes to chemotherapy | HCC, NSCLC and xenograft | [120] | |

| let-7a | transcriptionally downregulates Akt2, Akt3 | inhibits proliferation | lung cancer cells, cancer stem cell | [17, 121, 122] | |

| miR-181a-5p | transcriptionally downregulates Akt3 | causes senescence, inhibits the viability, proliferation | uterine leiomyoma cells, uveal melanoma cells, NSCLC | [123, 125] | |

| miR-489 | transcriptionally downregulates Akt3 | promotes apoptosis, suppresses cell growth and EMT | ovarian cancer cells | [124] | |

| Negative indirect | miR-365 | transcriptionally downregulates PI3K regulatory subunit 3 (PIK3R3), and inhibits Akt phosphorylation | inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion | glioma cells NSCLC | [129] |

| miR-17-5p | upregulates PTEN through RRM2 | inhibits proliferation | Lung AC cells | [127] | |

| miR-383-5p | transcriptionally downregulates TRIM27 (ubiquitin ligase of PTEN) and upregulates PTEN | inhibits proliferation | ovarian cancer tissue and cells NSCLC cells | [116, 130] | |

| let-7a | downregulates IGF1 receptor and inhibits PI3K/Akt activity | inhibits proliferation | CRC and prostatic cancer cells | [122] | |

| Dual functions | miR-26a-5p | (1) transcriptionally downregulates PTEN | enhances proliferation | NSCLC, glioma, T-cell leukemia cells | [117] |

| (2) inactivation of Wnt/b-catenin | suppresses proliferation | breast cancer cells, HCC cells | [83] | ||

| miR-181 | enhances PTEN function | inhibits cell proliferation | NSCLC | [125] | |

| miR-181a | downregulates PTEN | promotes cell proliferation, chemoresistance | T-cell lymphoma, Colorectal cancer, NSCLC cells | [84, 126] |

Abbreviations. PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10; 3′-UTR, 3′-untranslated region; AC, adenocarcinoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung carcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; RRM2, ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit M2; CRC, colorectal cancer; TRIM27, tripartite motif 27; IGF1, insulin-like growth factor 1.

3.2.2.1 Positive Indirect Regulators

This group of miRs mostly activate Akt by suppressing PTEN. miR-221/222, miR-200c-3p (the mature form of miR-200c) and miR-19b transcriptionally downregulate its expression, thereby indirectly activating Akt in NSCLC cells [113, 114, 115, 116].

Although miR-26a-5p causes the downregulation of PTEN, leading to Akt activation, it plays dual roles in tumorigenesis. It serves as an oncogene in NSCLC [117], but functions as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells through inhibition of the Wnt/b-catenin pathway [83].

3.2.2.2 Negative Direct Regulators

miR-374b destabilizes and negatively regulates Akt1-mRNA expression post-transcriptionally in colorectal cancer (CRC) cells [17, 118] and was confirmed to be an independent favorable prognostic factor in NSCLC [119].

miR-124-3p destabilizes Akt2 and inhibits tumor growth in vivo in a NSCLC xenograft model [120].

The 3′-UTR of Akt2 mRNA has one let-7a binding site, and the Akt3 mRNA has three binding sites, suggesting possible suppression of Akt2/3 by let-7a [17]. In addition, during some types of EMT, increased levels of let-7a causes suppression of Akt1 phosphorylation at S473 and T308 [17]. Clinically, lower levels of let-7a correlated with poor prognosis in NSCLC [121]. let-7a also functions as a negative regulator of Akt in an indirect manner and targets the insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) receptor and thereby indirectly inhibits the PI3K/Akt pathway [122].

miR-181a-5p and miR-489 induce suppression of Akt3 [123, 124]. In NSCLC, miR-181a-5p expression levels in tissue and plasma were found to be significantly lower, which correlated with lower progression-free survival (PFS) rate [125]. However, the miR-181 family has been reported to have a dual function depending on the cell type or tissues. On one hand, miR-181 enhances PTEN activity and inhibits cell proliferation, and is significantly downregulated in NSCLC [126]. On the other hand, miR-181a promotes cell proliferation and chemoresistance by suppression of PTEN levels in T-cell lymphoma, CRC cells [84, 131] and NSCLC [132]. miRNA-181c is peculiar in that it represses PDK1, which phosphorylates and activates Akt3 more than Akt1 or Akt2 in metastatic brain tumor [133], but also downregulates the expression of PTEN in breast carcinoma [134]. Therefore, miRNA-181c regulates Akt in dual and opposite manners [84].

3.2.2.3 Negative Indirect Regulators

miR-17-5p upregulates PTEN and inhibits phosphorylation of Akt through ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit M2 (RRM2), suppresses proliferation of NSCLC cells [135] and sensitizes A549 cells to gemistabin [127].

miR-409-3p directly, and also indirectly inhibits Akt through the posttranscriptional downregulation of c-Met and subsequent Akt phosphorylation in lung AC cells [128, 135].

miR-365 expression levels were significantly lower in serum from NSCLC patients, and far lower in patients having cancer with higher pT and pN factors, and had a lower overall survival (OS) rate [129, 136].

miR-383-5p downregulates tripartite motif 27 (TRIM27), which is a really interesting new gene (RING)-type E3 ubiquitin ligase that ubiquitinates PTEN, and therefore indirectly inactivates all three Akts [116]. miR-383-5p was described to be significantly lower in NSCLC tissues from patients of advanced stages [130].

lncRNAs (detailed in Chapter 3.1) can interact with DNA, RNA or proteins, and play a role in their regulation [137]. lncRNAs can function as “sponges” to adsorb miRNAs, serve as competitor “decoys” or play additional roles in transcription, post-transcription, translation and epigenetic regulation [137, 138].

lncRNAs are generally classified as either oncogenic or tumor suppressive, but some lncRNAs can be both, depending on the particular cancer (Table 5, Ref. [139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185]) [138]. Such examples include the lncRNA H19, and Xist (X-inactive specific transcript) [138, 139, 140, 141, 142].

| lncRNA | Direct action | Consequence | References | ||

| Upregulates all Akts | |||||

| LINK-A | directly interacts with the Akt pleckstrin homology domain and PIP3 | facilitates Akt-PIP3 interaction | [143] | ||

| UCA1 | (1) interacts with EZH2 which recruits H3K27me3 to the promoter of PTEN | inhibits PTEN expression and activates Akt | [144] | ||

| (2) sponges miR-138-5p, which inhibits protein kinase 2 (PTK2) activity | released PTK2 activates Akt | [145] | |||

| (3) sponges miR-613 which otherwise inhibits anexelekto (Axl), an enhancer of PI3K phosphorylation | released Axl phosphorylates PIK3 and indirectly activates Akt | [146] | |||

| LINC00152 | sponges miR-613 which otherwise inhibits anexelekto (Axl), an enhancer of PI3K phosphorylation | released Axl activates PIK3 and Akt | [148, 149] | ||

| AFAP1-AS1 | recruits EZH2 which inhibits PTEN expression | indirectly activates Akt by suppression of PTEN | [147] | ||

| MALAT1 (metastasis associated in lung adenocarcinoma transcript-1) | enhances the expression of p85 of PI3K, in part by targeting miR-503 | enhanced PIK3 activates Akt | [150, 151, 152] | ||

| HOTAIR | (1) sponges miR-126a, which suppresses expression of PIK3R2, a subunit of PI3K | enhanced PI3K expression activates Akt | [155] | ||

| (2) sponges miR-326, an inhibitor of FGF1 expression | higher FGF1 expression upregulates Akt | [156] | |||

| (3) sponges miR-20b-5p, which suppresses expression of ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit M2 (RRM2) | enhanced RRM2 expression results in increased phosphorylation and activation of Akt | [157] | |||

| (4) sponges miR-34a, a suppressor of Axl expression | enhanced Axl expression promotes PIK3 activity leading to Akt upregulation | [158] | |||

| FOXD2-AS1 | sponges miR-195, a suppressor of FGF expression | enhanced FGF expression activates the Akts | [162] | ||

| Xist | sponges miRNA-139-5p, a suppressor of PDK1 | higher PDK1 amounts promotes phosphorylation and activation of Akt | [141] | ||

| BC087858 | activates PI3K/AKT pathway in non-T790M mutation | activates PI3K/AKT pathway in T790M-negative patients and induces resistance to EGFR-TKIs | [180] | ||

| MIR31HG | sponges miR-193a-3p, a suppressor of PIK3R3 | enhanced PIK3R3 activates Akt and leads to gefitinib resistance in NSCLC cells | [181] | ||

| PCAT-1 | binds directly to FKBP51, displacing PHLPP from IKK complex | downregulation of IKK complex results in higher Akt phosphorylation and activation. Causes gefitinib resistance in NSCLC | [183] | ||

| H19 | (1) mature form of H19, miR-675, degrades RUNX1 (Runt Related Transcription Factor 1), a negative regulator of PIK3CD (delta catalytic subunit of PI3K) | release of PIK3CD allows PI3K to phosphorylate and activate Akt | [139, 184] | ||

| (2) sponges miR-194-5p, a suppressor of Akt2 expression | results in higher expression and activation of Akt2 | [140, 185] | |||

| LINC00963 | competitively binds to miR-655, an inhibitor of the transcriptional activator TRIM24 | higher TRIM24 expression transcriptionally activates PI3K, upregulating Akt | [153, 154] | ||

| Isoform-specific | |||||

| Akt1 | |||||

| FOXD2-AS1 | sponges miR-185, a suppressor of Akt1 expression | results in higher amounts of activated Akt | [161, 163] | ||

| SOX2-OT (SOX2 overlapping transcript) | sponges miR-942-5p, a suppressor of Akt1 expression. | Akt expression and phosphorylation is enhanced | [164] | ||

| Akt2 | |||||

| MALAT1 | sponges miR-625-5p, a suppressor of Akt2 expression | results in higher Akt2 expression | [165, 166, 167, 168] | ||

| H19 | sponges miR-194-5p, a suppressor of Akt2 expression | results in higher Akt2 expression | [185] | ||

| Akt3 | |||||

| FEZF1-AS1 | sponges miR-610, a suppressor of Akt3 expression | higher Akt3 activity is observed in myeloma, NSCLC | [169, 170] | ||

| Downregulate | |||||

| Pan-Akt | |||||

| MEG3 | sponges miR-183, an enhancer of BRI3 expression, a positive regulator of Akt phosphorylation | reduced BRI3 expression results in lower Akt phosphorylation | [159, 160] | ||

| Xist | upregulates PHLPP1 by sequestering HDAC3 from the PHLPP1 promoter | Akt activity is reduced by enhanced PHLPP1 phosphatase activity | [142] | ||

| Xist | sponges miRNA-181a, a suppressor of PTEN expression. | higher PTEN expression suppresses Akt activation | [171] | ||

| GAS5 | (1) sponges miR-222, a suppressor of PTEN expression | enhanced PTEN activity suppresses Akt | [172, 182] | ||

| (2) sponges miR-103, a suppressor of PTEN expression | enhanced PTEN activity suppresses Akt | [174] | |||

| (3) sponges miRNA-106a-5p, a downregulator of PTEN in gastric cancer cells | enhanced PTEN activity suppresses Akt | [173] | |||

| (4) competitively sponges miR-21 in cervical carcinoma cells | suppression of miR-21 results in reduced Akt activity | [176] | |||

| (5) competitively sponges miR-222, a suppressor of protein phosphatase 2A subunit B (PPP2R2A) expression | Akt activity is reduced by enhanced PPP2R2A phosphatase activity | [175] | |||

| FER1L4 | (1) sponges miR-18a-5p, a suppressor of PTEN | enhanced PTEN activity suppresses Akt | [177] | ||

| (2) sponges miR-106a-5p, a suppressor of PTEN | enhanced PTEN activity suppresses Akt | [178] | |||

| WT1-AS | sponging miR-494-3p, a suppressor of PTEN expression | enhanced PTEN activity suppresses Akt | [179] | ||

| H19 | confers erlotinib sensitivity by downregulation of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) | suppressed PKM2 leads to dephosphorylation of Akt in EGFR-mutated NSCLC | [184] | ||

Abbreviations. lncRNAs, long ncRNAs; LINK-A, long intergenic non-coding RNA for kinase activation; UCA1, urothelial cancer associated 1; AFAP1, actin filament associated protein 1; AS1, antisense RNA1; HOTAIR, HOX transcript antisense intergenic RNA; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; PHLPP, PH domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase; TRIM24, Tripartite motif-containing 24; Xist, X-inactive specific transcript; GAS5, growth arrest-specific 5; FER1L4, Fer-1 Like Family Member 4; WT1-AS, WT1 Antisense RNA; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate; EZH2, enhancer of zeste 2; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10; PI3K, phosphoinositide-3 kinase; PIK3R2, phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 2; PDK1, 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1; NSCLC, non-small cell lung carcinoma; HDAC, histone deacetylase; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; IKK, I kappa B kinase; FEZF1, FEZ family zinc finger 1; FKBP51, FK506 binding protein 51; MIR31HG, host gene of miR-31; PCAT-1, Prostate Cancer Associated Transcript 1; FOXD2, Forkhead box protein D2; BRI3, Brain Protein I3; HDAC3, Histone deacetylase 3; FGF1, fibroblast growth factor 1; MEG3, maternally expressed gene 3.

Many lncRNAs have been found to participate in the Akt pathway and modulate the expression or activation of Akt either positively or negatively. These effects may be via the direct targeting of downstream effectors, or indirectly through miRNAs [138, 186]. Representative oncogenic lncRNAs that directly target and promote the activity of effectors in the Akt pathway are described below and in Table 5. These include LINK-A (long intergenic non-coding RNA for kinase activation) [143], UCA1 (urothelial cancer associated 1) [144] and AFAP1-AS1 (actin filament associated protein 1 antisense RNA1) [187]. LINK-A directly interacts with the PH domain of Akt and PIP3, facilitating Akt-PIP3 interaction, and thereby activates Akt [143]. Clinically, LINK-A plasma levels were found to be significantly higher in patients having metastatic NSCLC versus those without metastasis [188]. Moreover, patients with high plasma LINK-A had shorter PFS [188]. UCA1 [144] and AFAP1-AS1 [187] interact with EZH2 (enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2 subunit), which recruits H3K27me3 to the promoter of PTEN and inhibits PTEN expression [189]. However, UCA1 also indirectly activates Akt activity by targeting miR-138-5p and miR-613, which inhibit protein kinase 2 (PTK2) activity or anexelekto (Axl), an enhancer of PI3K tyrosine phosphorylation, respectively [145, 146, 190].

AFAP1-AS1 has been found to promote cisplatin resistance in NSCLC through the PI3K/Akt pathway in A549 cells [147].

LINC00152 acts similarly by sponging miR-613 [148]. LINC00152 promotes the growth, invasion, and migration of lung AC cells and is associated with poor patient prognosis [149]. Consistently, LINC00152 knockdown inhibits those effects by suppression of the EGFR/PI3K/Akt pathway [149].

Some lncRNAs exert their effects indirectly via miRs, effectively functioning as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) in various types of cancers [138]. Metastasis associated in lung adenocarcinoma transcript-1 (MALAT1) sponges miR-503 which normally suppresses expression of the PI3K subunit p85 [150, 151]. As its name suggests, MALAT1 promotes cellular proliferation, the EMT, and angiogenesis in lung cancer, and facilitates tumor growth, invasion and metastasis. Therefore, overexpression may predict aggressive behavior of the tumor and poor prognosis of the patient [152].

LINC00963 indirectly activates PI3K/Akt by targeting miR-655, which inhibits TRIM2, a transcriptional activator of PI3K [153]. It is upregulated in NSCLC, and its overexpression was associated with a higher TNM stage [154]. The HOX transcript antisense intergenic RNA (lncRNA HOTAIR) promotes the expression of phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 2 (PIK3R2), a subunit of PI3K, through sponging of miR-126 [155]. In addition, HOTAIR sponges miR-326, which targets fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1), thus releasing FGF1 to activate Akt [156], and thus, HOTAIR activates three Akt isoforms, promotes cell-cycle transition and cell proliferation, and inhibits apoptosis [157, 158]. In vitro, HOTAIR regulates apoptosis and the cell cycle and is involved in cisplatin resistance of human lung AC cells [191]. In lung cancer, HOTAIR expression was significantly higher in tumor tissues, and was correlated with higher pN, pStage and poor prognosis [191, 192].

Conversely, various tumor suppressor lncRNAs have also been described. One representative example is maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3), which sponges miR-183. This leads to suppression of the miR-183 target Brain Protein I3 (BRI3) expression, a positive regulator of Akt phosphorylation [159]. In a meta-analysis of NSCLC, lower expression was associated with worse prognosis in OS and MEG3 was an independent prognostic factor for PFS [160]. Growth arrest-specific 5 (GAS5) has been reported to inhibit the phosphorylation of Akt through several miR-dependent pathways [138], which will be explained later. Downregulation of GAS5 expression in NSCLC tissue and plasma, and elevation after surgery was reported. Moreover, lower GAS5 was associated with poor prognosis of NSCLC patients [193].

In-silico analyses have suggested that a number of lncRNAs might target Akt in an isoform-specific manner [194].

Forkhead box protein D2 (FOXD2)-AS1 sponges miR-185 and thereby specifically upregulates Akt1 [161], but also targets miR-195 as a ceRNA and thereby releases FGF, which activates all three Akt isoforms [162]. FOXD2-AS1 was found to confer cisplatin resistance in NSCLC cells as well as in a tumor xenograft model [163].

SOX2 overlapping transcript (SOX2-OT) upregulates and activates Akt1/2, MALAT1 and H19 activate pan-Akt, but predominantly Akt2, FEZ family zinc finger 1 (FEZF1)-AS1 activates Akt3.

SOX2-OT promotes the upregulation and phosphorylation of Akt1 by sponging miR-942-5p and induces breast cancer cell metastasis [164, 195]. Moreover, SOX2-OT also contributes to gastric cancer progression via sponging miR-194-5p to release active Akt2 [196]. Exosomal SOX2-OT was significantly upregulated and thus, diagnostic and also significantly correlated with the TNM stage in SCC of the lung [197].

MALAT1 has been reported to be oncogenic in broad range of cancers [165, 166, 167]. Mechanistically, MALAT1 not only targets p85 through miR-503 as mentioned, but also sponges miR-625-5p, which otherwise downregulates Akt2 [168].

FEZF1-AS1 targets miR-610, and releases Akt3 in myeloma cells [169]. Plasma FEZF1-AS1 levels were described to be a significant diagnostic biomarker of NSCLC and higher level of plasma FEZF1-AS1 was associated with advanced TN-stage of NSCLC [170].

As these examples of lncRNAs demonstrate, a single lncRNA may regulate multiple targets, and can even exert opposing effects to both activate and inactivate Akt through different signaling pathways.

The lncRNA Xist sponges miRNA-181a, a positive regulator of PTEN, resulting in suppressed PTEN expression and activation of Akt in NSCLC, CRC and acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) as described in Section 3.2.2 [84, 171]. In this manner, Xist indirectly activates Akt and enhances cell proliferation. Moreover, Xist sponges miR-139-5p, a negative regulator of PDK1, and this promotes cell-cycle progression at the G1 to S phase transition, protects cells from apoptosis and contributes to HCC cell growth [141]. Indeed, Xist was found to have higher expression in HCC tissues and cell lines [141]. At the same time, however, Xist can inhibit Akt activation and reduce cell viability in breast cancer cells by sequestering histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3). This removes HDAC3 from the promotor of PH domain and leucine-rich repeat phosphatase 1 (PHLPP1), a phosphatase responsible for Akt dephosphorylation. This derepresses PHLPP1 expression, resulting in increased Akt dephosphorylation [142].

GAS5 negatively regulates the Akt pathway through the action of several miRs. First, GAS5 functions as a ceRNA for miR-222 [172] and miR-106a-5p [173] in gastric cancer and for miR-103 in arthritis model [174]. These miRs are negative regulators of PTEN [175]. GAS5 also exerts its suppressive function by sponging miR-21, which normally enhances Akt as mentioned in Chapter 3.2.1 [176].

Fer-1 Like Family Member 4 (FER1L4) targets miR-18a-5p and miR-106a-5p, which have been shown to be negative regulators of PTEN in lung and gastric cancer cells, respectively. Therefore, FER1L4 derepresses PTEN expression, resulting in the induction of apoptosis [177, 178].

WT1 Antisense RNA (WT1-AS) promotes PTEN expression and inhibits activation of Akt by sponging miR-494-3p, which downregulates PTEN in glioma cells [179].

From clinical studies of cancer therapeutics, it has been found that NSCLC cells that have acquired resistance against gefitinib tend to have increased activation of the Akt pathway (Chapter 2.4.3). These studies detected overexpression of lncRNA BC087858 [180], host gene of miR-31 (MIR31HG) [181], UCA1 [198] and/or reduced expression of GAS5 [182]. A causal relationship has been confirmed in some of these cases. Genetic knockdown of BC087858 in NSCLC with a non-T790M mutation restored gefitinib sensitivity and inhibited PI3K/Akt activation [138]. MIR31HG was found to increase resistance to gefitinib in NSCLC cells in part by sponging miR-193a-3p, which suppresses PIK3R3, a regulatory subunit of PI3K, thereby upregulating the EGFR/PI3K/Akt pathway [181].

The functional involvement of other lncRNAs in lung cancers have also been described. lncRNA Prostate Cancer Associated Transcript 1 (PCAT-1) was found to be highly expressed in EGFR TKI-resistant NSCLC, and acts to enhance phosphorylation of Akt and thereby confer gefitinib resistance [199]. This is due to the direct binding of PCAT1 to FK506 binding protein 51 (FKBP51), which releases PHLPP from the active PHLPP/FKBP51 complex. Since PHLPP dephosphorylates PI3K/Akt only in the form of complex with FKBP51, PCAT1 inhibits phosphatase activity of PHLPP and leads to activation of Akt as a result [183].

LncRNAs H19 confers erlotinib sensitivity through downregulation of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) and dephosphorylation of Akt in lung carcinomas carrying a mutated EGFR [184]. However, H19 is peculiar in that it could also function as an oncogenic lncRNA via different downstream effectors. Exon 1 of H19 also encodes miR-675, which targets Runt Related Transcription Factor 1 (RUNX1), a negative transcriptional regulator of catalytic subunit delta of PI3K (PIK3CD). As a result, expression of H19 activates all three Akt isoforms in gastric cancer cells [139]. In addition, H19 sponges miR-194-5p, a suppressor of Akt2, and thus upregulates Akt2 in gallbladder cancer cells [185].

To date there are reports of approximately 953 aberrant lncRNAs expressed in AC and 1014 in SCC of the lung [200].

Since clinical trials, unfortunately, have shown that most current Akt inhibitors provide little benefit to most cancer patients [138] (Chapter 4). A better understanding of the roles of lncRNAs in regulating the Akt pathway may inform the development of superior, novel treatments.

Another subclass of lncRNAs is the circular RNAs (circRNAs). These are looped, single-stranded, covalently closed RNAs that exert their physiological functions by interacting with other ncRNAs or proteins [80, 186]. Similar to other lncRNAs, circRNAs can serve as miRNA sponges via multiple binding sites [80], as protein decoys [201], as components of the translation machinery [202] and can even encode short peptides [80].

circRNAs function essentially as ceRNAs, binding to miRs and suppressing their inhibitory effects. circRNAs that modulate Akt are involved in the regulation of apoptosis, autophagy, ER stress, senescence, migration and carcinogenesis. Although many human circRNAs have been reported to modulate all three Akt isoforms, there are also circRNAs that specifically target Akt1, Akt2, or Akt3 [186]. Representative circRNAs that influence Akt, including those found in lung carcinomas, are described below and summarized in Table 6 (Ref. [203, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217]).

| circRNA | Direct action | Consequence | References | ||

| Upregulates Akt | |||||

| on Pan-Akt | circRNA | sponges miR-1299, a suppressor of EGFR expression | upregulates PI3K/AKT and promotes drug resistance in lung AC | [203] | |

| CDR1as (ciRS-7) | |||||

| circ_0004015 | sponges miR-1183, a suppressor of PDK1 expression | enhanced PDK1 activates Akt | [204] | ||

| circ_0106705 | sponges miR-1183, a suppressor of PDK1 expression | enhanced PDK1 activates Akt | [205] | ||

| (circ-ACACA) | |||||

| circ_RHOBTB3 | sponges miR-600, a suppressor of methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) expression | METTL3 modifies and promotes PI3K expression, activating Akt | [206, 207] | ||

| on AKT1 | circ-AMOTL1 | directly binds Akt1 and PDK1 and enhances nuclear translocation | PDK1/Akt pathway is activated | [208] | |

| on AKT3 | circPARD3 | sponges miR-145-5p, a suppressor of Akt3 expression | Akt3 is upregulated | [209] | |

| circ_0043278 | sponges miR-520f a suppressor of Akt3 expression | Akt3 is upregulated | [210] | ||

| Downregulate Akt | |||||

| on Pan-Akt | circ-PLCD1 | sponges miR-375 and miR-1179, suppressors of PTEN expression | enhanced PTEN downregulates Akt | [212] | |

| Dual functions on Akt | circ_AKT3 | peptide product binds to p-PDK1, reducing Akt-thr308 phosphorylation | lower PDK1 activity reduces Akt activation | [213] | |

| (circ_0112784) | |||||

| crc_AKT3 | (1) sponges miR-198, a suppressor of PIK3R1 expression | enhanced PIK3R1 activates Akt | [214] | ||

| (circ_0000199) | |||||

| (2) sponges miR-206/613, suppressors of Akt pathway | Akt3 is upregulated | [215] | |||

| circ_AKT3 | (1) targets miR-296-3p, a suppressor of E-cadherin | inhibits metastasis | [216] | ||

| (circ_0017252) | |||||

| (2) sponges miR-296-3p, a suppressor of Akt3 expression | Akt3 is upregulated | [216, 217] | |||

| circ_WHSC1 | sponges miR-296-3p, a suppressor of Akt3 expression | Akt3 is upregulated | [211] | ||

Abbreviations. circRNA, circular RNA; CDR1as, cerebellar degeneration-related protein 1 antisense RNA; AC, adenocarcinoma; PDK1, 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1; RHOBTB3, Rho-related BTB domain-containing protein 3; AMOTL1, Angiomotin-like protein 1; PARD3, Partitioning defective 3; METTLE3, Methyltransferase like 3; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10; PLCD1, 1-Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase delta-1; PIK3R1, phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 1; WHSC1, Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome candidate-1.

circRNA cerebellar degeneration-related protein 1 antisense RNA (CDR1as/ciRS-7) is a pan-Akt activator that promotes resistance to pemetrexed and cisplatin (CDDP) by activation of the EGFR/PI3K pathway. This is due in part to sponging miR-1299, an inhibitor of EGFR in lung AC [203, 218].

circ_0004015 contributes to cancer progression and gefitinib resistance in NSCLC by sponging miR-1183, a negative regulator of PDK1 and prevents apoptosis and confers drug resistance [204, 219, 220].

circ_0106705 (circ_ACACA) also adsorbs miR-1183 and is therefore assumed to activate PDK1 and upregulates proliferation, migration and glycolysis of NSCLC cells [205].

circ_Rho-related BTB domain-containing protein 3 (RHOBTB3) sponges miR-600, which degrades METTL3, a translational activator of EGFR, and thus, activates pan-Akt [206]. circ_RHOBTB3 showed higher expression in lung AC tissue in the meta-analysis [207].

circ_Angiomotin-like protein 1 (AMOTL1) is an isoform-specific enhancer that directly binds to PDK1 and Akt1 proteins, resulting in higher Akt1 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation [208].

circ_Partitioning defective 3 (PARD3) [209, 221], circ_0043278 [210] and circ_Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome candidate-1 (WHSC1) [211] sponges miR-145-5p, miR-520f and miR-296-3p, respectively, leading to higher phosphorylation of Akt3 and lung cancer progression.

circ_1-Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase delta-1 (PLCD1), a tumor suppressor circRNA, is transcriptionally activated by p53 and acts as a ceRNA to sponge miR-375 and miR-1179, thereby upregulating PTEN and inhibiting NSCLC cell proliferation, invasion and apoptosis. Consistently, circ_PLCD1 is suppressed in NSCLC tissues and cell lines. Moreover, low circ-PLCD1 expression in NSCLC patients was associated with larger tumor size, higher clinical stage and shorter survival [212].

Some circ_RNAs can have multiple functions. circ_AKT3 consists of several RNAs generated from the AKT3 gene, including circ_0112784, circ_0000199, circ_0017250 and circ_0017252. One of those, circ_0112784, encodes a 174-amino-acid novel protein that directly competes with phosphorylated PDK1, reducing Akt-T308 phosphorylation and inhibiting the tumorigenicity of glioblastoma cells [213]. However, circ_0000199 sponges miR-198, which negatively regulates PIK3R1, a regulatory subunit of PI3K (p85

These results suggest strategies by which targeting of non-coding RNAs could be used soon as part of a cancer treatment regime.

Despite remarkable progress in the genetic analysis in cancer, the development of novel pharmacological therapies has not progressed as expected. The accumulated results described in Chapters 2 and 3 demonstrate the potential of Akt as a target of cancer therapy. Akt is one of the most critical nodes in both oncogenesis and resistance to chemotherapy: Akt inhibitors generally impede cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis in cultured cells [217] and cisplatin resistance in lung cancer cells is linked to AKT1 amplification [222]. Furthermore, the sensitivity of NSCLC cells to TKI of EGFR has been shown to correlate with Akt inhibition, presumably because Akt mediates the signal transmitted from mutated EGFR [223, 224]. Therefore, Akt inhibitors not only can target cancer cells harboring aberrant AKT genes, but can also sensitize cells to other cytotoxic agents. For lung cancers without a driver gene, the use of Akt inhibitors would be a viable therapeutic modality, especially as a large fraction of cancers exhibit activation of Akt [13, 53]. A number of Akt inhibitors have been developed that function by competitive inhibition of the catalytic (kinase) domain, ATP binding, or as allosteric inhibitors [225, 226].

Although Akt inhibitors have shown promise in vitro and in vivo models, only a limited number of compounds have advanced to clinical trials and none of these has been approved for practical use [138, 225].

MK-2206 is an orally active, allosteric Akt inhibitor that has been shown to be equally effective against Akt1 and Akt2, but less so against Akt3, in colon, lung and breast cancer cells [227, 228]. Although MK2206 has shown anti-tumor effects to some extent in preclinical trials for breast cancer, it has not progressed further in clinical trials due to its limited efficacy and dose-limiting toxicity observed in phase 2 trials [30, 229].

Currently, a number of promising Akt inhibitors have been tested in phase III trials. However, as most Akt inhibitors show limited efficacy as monotherapies, these are predominantly tested in combination with Capivasertib or Ipatasertib which are the most studied ATP-competitive inhibitors of Akt [30, 230].

Capivasertib (AZD5363) is an oral and the ATP-competitive inhibitor of pan-Akts whose effect was confirmed in vitro and in breast carcinoma xenografts in vivo [231, 232, 233]. It was shown to be effective in extending PFS when used in combination with fulvestrant (estrogen receptor antagonist) and/or palbociclib (CDK4/6 inhibitor) in a subset of metastatic/recurrent, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients in phase III study by AstraZeneca (CAPItello-291 test) and by National Cancer Institute Hospital in Japan (https://jrct.mhlw.go.jp/en-latest-detail/jRCT2031220034) [232, 234]. Although capivasertib has not been used in the clinic, several lines of evidence from trials suggest its utility for lung cancer. In both first- (phase III, FLAURA trial) and second-line trials (phase III, AURA3 trial), resistance to osimertinib, a TKI for NSCLC harboring EGFR mutation, has been found to be associated with activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway [223, 224]. For these defined groups, capivasertib overcame this resistance. Similarly, NSCLC having mutations in the EGFR and aberrations in PIK3CA/AKT were found to be resistant to osimertinib, but were re-sensitized by dual treatment with osimertinib and capivasertib in both cell lines and a mouse xenograft model [224].

Not only in NSCLC, but also in SmCC, activation of PI3K/Akt pathway by somatic mutations or gene amplification promotes malignant transformation and confers chemoresistance [235, 236]. Capivasertib at a clinically robust dose was effective against a panel of SmCC cell lines regardless of genetic profile. In addition, capivasertib at a non-toxic dose was effective in suppressing SmCC growth and in combination with cisplatin achieves nearly complete growth inhibition in a mouse xenograft model [217]. These results provide a rationale for further clinical trials of capivasertib in combined regimen for SmCC.

The combined use of the pan-CDK inhibitor roscovitine, and the Akt inhibitor VIII (AKTiVIII), which is the allosteric dual inhibitor of Akt1 and Akt2, was reported to be synergistically effective in lung cancer cells [38].

The development of acquired resistance can occur by many mechanisms. First, the Rat sarcoma virus (RAS)-MAPK and PI3K-Akt pathways can inhibit each other, i.e., inhibition of one pathway enhances signaling by the other. Thus, inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway upregulates Erk1/2 activation. Indeed, it was noted that inhibition of Akt with capivasertib upregulates Erk phosphorylation in NSCLC cells [31]. A second mechanism is downregulation of PTEN by a PI3K/Akt inhibitor. Other mechanisms include the induction of RTKs including IGFR-1, EGFR, HER2, and HER3 [237], and acquired amplification of related genes, such as AKT3 observed with MK-2206 treatment for breast cancer. The most frequent adverse event for grade 3 or higher observed with capivasertib–fulvestrant cancers was an incidence of rash (12.1%) [30, 234].

Ipatasertib (GDC-0068) is a highly selective and novel oral Akt inhibitor that functions in an ATP-competitive manner and which exhibited significant antitumor activity in breast cancer cells in vitro [238]. Clinically, it improves prognosis in a subset of patients with locally advanced breast carcinoma when used in combination with paclitaxel or fulvestrant/palbociclib [2, 239]. Unlike previously reported ATP-competitive inhibitors, it appears to have fewer off-target effects on other AGC kinase family members [238]. ACK1 (Activated CDC42-associated kinase 1) is a tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates and activates Akt. Combined inhibition of ACK1 by dasatinib or sunitinib and the Akt inhibitor MK-2206 or Ipatasertib showed therapeutic promise against NSCLC cells having mutated KRAS [240]. Moreover, a multi-institutional phase 2 trial using Ipatasertib together with docetaxel has been proposed for NSCLC (P2.10A.05 Ipat-Lung) [241].