1 Department of Pharmacy and Engineering Research Center of Tropical Medicine Innovation and Transformation, The First Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University, 570102 Haikou, Hainan, China

2 Department of Pharmacology, Hainan Medical University, 571199 Haikou, Hainan, China

3 College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Hainan Medical University, 571199 Haikou, Hainan, China

4 Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University, 570102 Haikou, Hainan, China

5 Department of Internal Medicine, Sanya Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 572000 Sanya, Hainan, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Brain endothelial cells (BECs) are situated at the interface between the bloodstream and the brain, serving a crucial function in the development and maturation of the brain, particularly in upholding the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Consequently, any modifications or gradual breakdown of the endothelium can significantly disrupt brain homeostasis. Ischemic stroke (IS), characterized by the progressive compromise of the BBB and increased BECs mortality, stands as a prominent global cause of mortality and disability. This review will utilize recent research to explore mechanisms underlying death.

Keywords

- ischemic stroke

- brain endothelial cells death

- neuroprotective drugs

According to research, the frequency and occurrence of strokes rose with time, and they were associated with high rates of death and disability, endangering people’s lives and health [1]. Of these, cerebral ischemic stroke (IS) accounts for around 70% of all stroke occurrences, making up the vast majority [2]. Insufficient blood flow and cerebral vascular congestion are characteristics of IS, which results in a lack of oxygen and nutrients reaching brain tissue. This, in turn, causes a number of pathophysiological alterations or injuries, including the death of brain cells, which ultimately causes neurological dysfunction [3].

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a specialized microvascular system that functions as an essential interface between the brain and blood, safeguarding the integrity and homeostasis of the central nervous system (CNS) [4]. They are mainly composed of brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs), astrocytes, pericytes and basement membrane. Endothelial cells constitute the capillary wall and are the main barrier of the BBB [5]. The endfeet of astrocytes are surrounded by brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs), whose secreted matrix proteins form the basement membrane. Additionally, pericytes are intricately embedded within the basement membrane that encompasses both the glial cells and the BMECs [6]. Investigating the mechanisms that maintain the integrity of the BBB is critical to our understanding of the regulation of exchange between the CNS and the periphery under both healthy and diseased states. Among them, brain endothelial cells have a role in maintaining the integrity and functionality of the BBB as well as promoting the formation of neuronal axon. They are also engaged in the regulation of vascular relaxation ability, blood cell transit, platelet adhesion, and neovascularization [7]. They form a barrier that highly limits the passage of solutes between nerve tissue and circulating blood vessels [8].

Nearly a quarter of stroke survivors had another stroke after 5 years, almost doubling after 10 years. Recurrent strokes are associated with a significantly high mortality rate; approximately 50% of individuals who survive their initial stroke pass away within five years, while around 75% do so within ten years [9]. Long-term all-cause mortality was mainly due to diseases other than stroke. Both recurrent stroke and long-term mortality are influenced by several modifiable risk factors [10]. Certain clinical trials have indicated that the annual risk of myocardial infarction or vascular mortality following an ischemic stroke varies between 1.8% and 4.6%. In a recent study, cardiovascular deaths accounted for 5 to 39% of late deaths during 10 years of follow-up [11].

As the primary effector cells involved in the angiogenic response, endothelial cells (ECs) surrounding the infarcted brain area commence proliferation as early as 12 to 24 hours following the onset of ischemic stroke [12]. Additionally, upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the peri-infarct region has been observed as early as three hours post-ischemic injury, indicating that angiogenesis can initiate within hours after the stroke occurs [13]. In the context of ischemic stroke, the migration of ECs from their stationary locations is facilitated by the loosening of intercellular connections among the ECs, coupled with a reduction in support from adjacent cells such as pericytes and smooth muscle cells. This dynamic ultimately results in vascular instability [14]. Following the onset of ischemic stroke, reactive astrocytes play a crucial role in reorganizing the extracellular matrix (ECM), leading to the formation of ECM bundles that migrating endothelial cells utilize to establish new capillary structures [15]. Once the pathway for sprouting is established, VEGF binds to its receptors on vascular endothelial cells, thereby triggering a direct angiogenic response that fosters both proliferation and migration of the ECs [16].

Decades of preclinical research have underscore the potential advantages of neuroprotection in experimental stroke models. A study indicates that a wide array of therapeutic agents has undergone testing in clinical trials or is presently under evaluation in preclinical investigations to assess their effectiveness in acute IS [17]. In recent years, drugs and compounds for the protection of brain endothelial cells have also been developed rapidly.

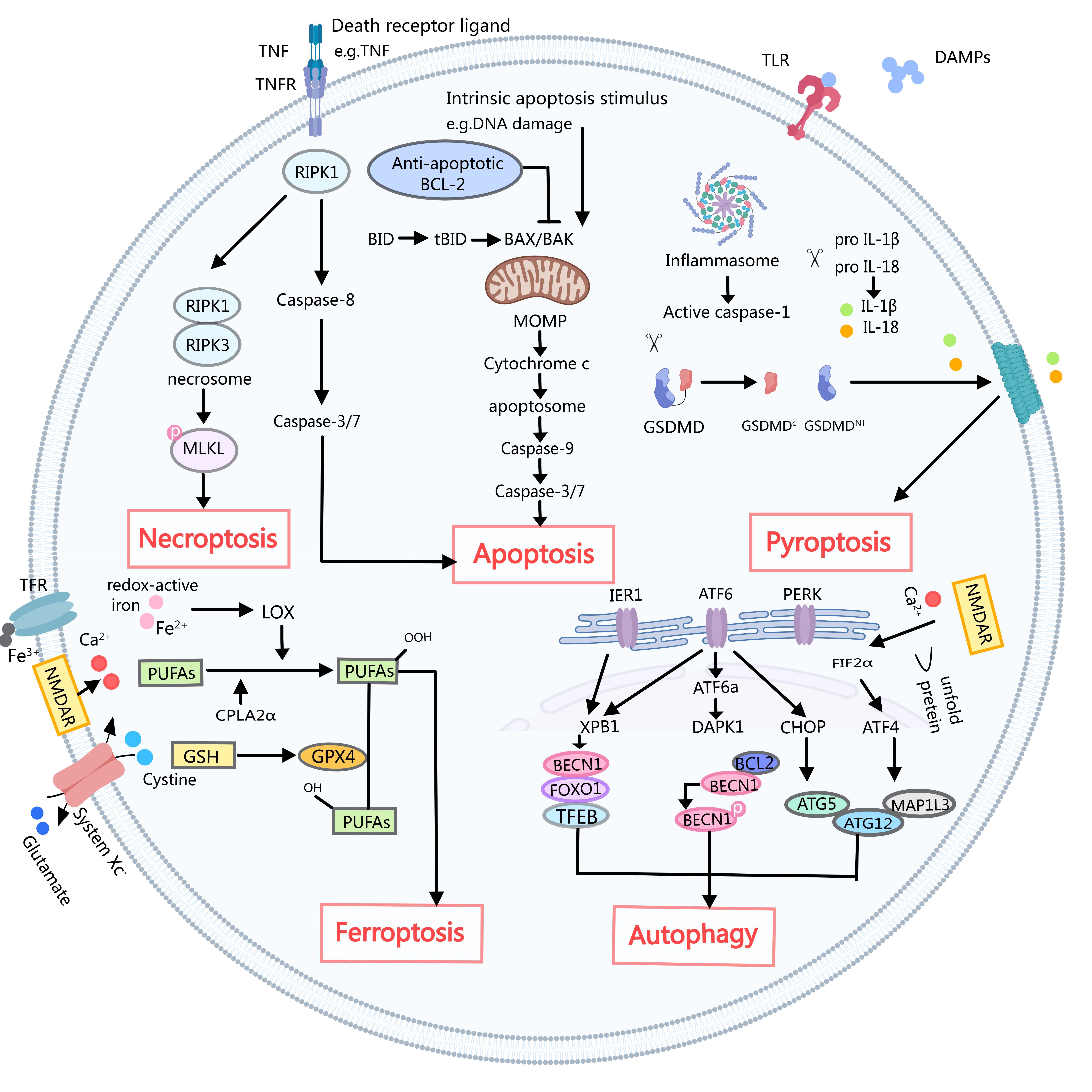

This review will reflect the importance of brain endothelial cells (BECs) death mechanisms in IS by introducing current information on different types of brain endothelial cell death mechanisms and mediators involved in regulating these responses, and discuss the application prospects of neuroprotective drugs, to offer dependable therapeutic strategies for the future treatment of IS (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. A simple schematic of several death mechanisms in ischemic stroke. Necroptosis: Death ligands such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) with its cognate receptor (TNFR) cause pleiotropic signaling, including inflammation and cell survival, cell apoptosis, and necrotizing apoptosis by key signaling molecules, receptor interaction protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) of serine/threonine decision. After inhibition of caspase-8, RIPK1 activates receptor interaction protein kinase 1 (RIPK3), leading to the formation of necrosomes. The necrosomes then phosphorylate and activate mixed lineage kinase-like (MLKL), leading to rapid membrane permeabilization and necroptosis. Apoptosis: The activation of caspase-8 triggers the subsequent activation of caspase-3 and caspase-7, ultimately resulting in cell death through the extrinsic apoptotic pathway. In contrast, the intrinsic apoptotic pathway is initiated by disturbances within the internal cellular environment, such as DNA damage, which leads to the permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane (MOMP). MOMP is regulated by interactions between pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family proteins. Promoting apoptosis protein the Bcl-2-associated X protein (BAX) and related the BCL-2 cognate antagonist killer protein (BAK) formed in the mitochondrial outer membrane aperture, resulted in the release of cytochrome c and the formation of apoptotic body apoptotic protease activating factor-1 (APAF-1). Apoptotic bodies activate caspase-9 and subsequently caspase-3 and caspase-7, leading to apoptosis. Caspase-8 through interaction will promote apoptosis BH3 domain death (BID) cut to activate BAX and BAK truncated BID (tBID), crosstalk between inner and external mediated apoptosis pathway. Pyroptosis: Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from dying cells play a crucial role in activating pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs). This leads to the activation of the classical inflammasome that activates caspase-1. Cracking gasdermin D (GSDMD) activated caspase-1, from GSDMD C inhibition of fragments of release GSDMD NT into a hole. GSDMD NT formed holes in membrane air and coke. Active caspase 1 also proinflammatory cytokines can be interleukin 1 beta (IL-1 beta) and IL-18 GSDMD hole to release the mature form of cracking. Ferroptosis: Typically, glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) utilizes glutathione (GSH) to catalyze the conversion of lipid hydroperoxides into corresponding alcohols. However, elevated levels of extracellular glutamate can inhibit the function of System Xc, consequently disrupting the cysteine-GSH-GPX4 axis. In addition, Ca2+ overload triggers the activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2

Compared to endothelial cells generated from peripheral organ arteries, BECs have distinct morphological and functional characteristics [7]. BECs are polarized cells distinguished by their intricate tight junctions, which primarily consist of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), claudin, and occludin, along with membrane solute carriers and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) efflux transporters. These highly specialized cells form the blood-brain barrier (BBB), playing a crucial role in regulating the selective and active transport of potentially harmful substances from the bloodstream into the brain [18]. In addition, BECs have a great number of mitochondria and a smaller number of pinopoditic vesicles, thereby limiting endocytosis and transcellular action [19, 20]. These characteristics enable BECs to collaborate with astrocytes, pericytes, and perivascular microglia to create the BBB in addition to enabling them to quickly supply oxygen, glucose, and other nutrients to fulfill the high metabolic demands of the brain.

Trauma, infections, oxidative stress, DNA-damaging chemicals, and the deposition of amyloid-

To date, studies have described a variety of regulatory-cell-death mechanisms [26, 27, 28]. These include apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and autophagy-dependent cell death. These cell-death mechanisms provide a basis for further characterizing endothelial cell death in nervous system diseases, bringing hope for the treatment of these diseases [29] and to provide new therapeutic targets for the treatment of IS by studying the potential mechanism of BEC death. In this section, we will introduce the latest research on the mechanism of endothelial cell death, and classify, supplement and summarize the previous research.

Of the different Endothelial-cells-death mechanisms identified in IS, apoptosis is the most extensively studied. Two distinct processes can cause apoptosis: The death receptor pathway, commonly referred to as the extrinsic pathway, operates in conjunction with the endogenous pathway, also known as the mitochondrial pathway or the B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) regulated pathway, which is classified as the intrinsic pathway [30, 31]. The intrinsic pathway is regulated by pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 protein family [32]. Activation of the extrinsic pathway occurs via members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily through the binding of their respective ligands [33]. Both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways ultimately converge on a final common pathway, which emphasizes the activation of the caspase protease family. This activation culminates in the hallmark features of apoptosis, including DNA fragmentation, chromatin condensation, and membrane blistering [34]. Additionally, the extrinsic pathway can induce intrinsic mitochondrial apoptosis by activating caspase-8, which subsequently generates truncated BID (tBID) [31]. Various regulatory proteins—including tumor protein 53 (p53), nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-

ASK1-K716R point mutation was found to inhibit apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) activity, as well as the activation of pro-apoptotic Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) pathway and pro-inflammatory p38 pathway in the brain. Further studies confirmed that ASK1-K716R inhibited downstream endothelial cell c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) activation, endothelial cell apoptosis and tight junction (TJ) protein loss, and protected the integrity of the blood-brain barrier. It can also reduce neuronal damage and white matter structure/function damage, reduce the inflammatory response in the brain, and finally improve the long-term sensory motor and memory dysfunction after traumatic brain injury (TBI) in mice [35].

Additionally, research has indicated that exosomes derived from endothelial cells have the capability to directly shield nerve cells against cerebral ischemic injury. They achieve this protective effect by fostering cell growth, enhancing migration and invasion, as well as inhibiting apoptosis [36]. Endothelial-cell-derived exosomes modification has the potential to be developed as a new therapeutic strategy to treat neuronal damage during cerebral ischemic injury.

Several case-control and epidemiological studies have shown that stroke risk is associated with clinical periodontitis [37, 38]. Gingipains of Porphyromonas gingivalis have been found in brain tissue [39]. Live Porphyromonas gingivalis and its virulence factors are powerful initiators of inflammation in the brain, directly affecting memory and lesion development [40]. Research has indicated that viable but non-heat-killed Porphyromonas gingivalis can induce apoptosis and contribute to cell death in brain endothelial cells. The infection by Porphyromonas gingivalis activates the reactive oxygen species (ROS)/NF-

Apoptosis is the most common mechanism of cell death. The above studies show that cerebral endothelial cell apoptosis plays a very important role in IS, but many mechanisms still need to be further explored.

Necroptosis represents a specific type of regulated necrosis that is initiated by death receptors [42]. This particular form of necrosis plays a crucial role in the body’s defense against infections caused by pathogens and is morphologically distinguished by the phenomenon of cell swelling, which is subsequently accompanied by the disruption of the plasma membrane [43]. Necrosis is triggered by the activation of other cellular receptors, such as Fas and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), which induce the production of interferon-

The key step underlying TNF-

In IS, Chen et al. [51] found for the first time that necroptosis of brain endothelial cells induced by TNF-

The above studies suggest an important role of CEs necroptosis in the development of IS. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms of endothelial necroptosis in IS may help us to better understand the pathogenesis of the disease and provide new therapeutic approaches.

A proinflammatory type of cell death is called pyroptosis [41]. Pyroptotic cell death shares morphological characteristics with both necrosis and apoptosis. The morphological alterations include nuclear condensation and DNA fragmentation akin to apoptosis, cellular swelling, hole creation, necrosis-like cell membrane rupture, and proinflammatory intracellular content release [55].

Pyroptosis is a molecular signature of gasdermin-mediated cell death [56]. Normally, two caspase-dependent mechanisms activate the gasdermin [57]. The inflammasome in the traditional caspase-1 pathway identifies substances linked with danger and pathogens that are released by dying cells, along with certain proinflammatory cytokines.

Gasdermin D (GSDMD) is cleaved by activated caspase 1, which leads to the oligomerization of the GSDMD-N domain in the cells. This finally forms pores and releases cell contents, including high mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) and IL-1

The various cell types that undergo pyroptotic cell death in the brain have not been extensively studied. However, studies have shown that BBB cells, especially BECs, are damaged and release proinflammatory cytokines after stroke [61]. In the early stage of stroke, brain endothelial pyroptosis may be induced mainly by IL-1 and reactive oxygen species (ROS) released from microglia, so the result is carbon skeleton rearrangement and loss of ligand protein function in brain endothelial cells, ultimately leading to initial BBB damage [62]. Several mitochondria are seen in BECs. As a result, a significant amount of ROS is generated following pyroptosis as a result of mitochondrial malfunction, which might harm other BBB-forming cells and compromise the integrity of the BBB [63].

MCC950, an inhibitor of the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, has been shown to specifically block the activation of NOD-like receptor protein 1 (NLRP1) and the secretion of IL18b, IL3, and GSDMD by preventing the oligomerization of apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a card (Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein) induced by NLRP3 [64]. In recent years, pyroptosis mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome has been recognized as a potential contributor to the death of brain endothelial cells (BECs). Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) can initiate pyroptosis in endothelial cells through the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-the receptor of advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE)-NLRP3 pathway, thereby exacerbating brain injury [65]. Emerging research indicates that the activation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor

A recent study has shown that gram-negative bacterial infection or lipopolysaccharide stimulation activates the caspase-4/22-GSDMD signaling pathway in brain endothelial cells, leading to inflammatory destruction of the blood-brain barrier [67]. This finding not only provides a new perspective to understand the mechanism of BBB disruption in the inflammatory state caused by pyroptosis, but also provides a potential therapeutic approach for central nervous system diseases associated with BBB loss.

Although our understanding of the effects of pyroptosis in BECs during IS is increasing, the exact mechanism of how pyroptosis senses different stimulus information is still largely unknown and remains a direction for future exploration.

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent, planned cell death that is brought on by the build-up of lipid peroxides, increased ROS generation, and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) inactivation [68]. Ferroptosis apparently has a role in a number of neurological conditions, including Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and stroke [69, 70]. Moreover, IS has been shown to improve with ferroptosis inhibitor therapy [71].

Ferroptosis plays a key role in neuronal cell death. However, any studies targeting other cell types have not been performed. Following a hemorrhagic stroke, disorders in iron metabolism and the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are observed in endothelial cells, microglia, and astrocytes [72], but studies targeting other cell types have not been performed. Endothelial ferroptosis is a potential pathogenic mechanism of stroke.

Findings that show that hypoxia-induced ferroptosis in BECs and the inhibitory effect of ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) on ferroptosis, alleviated hypoxia-induced BBB disruption, open the possibility of new potential targets for the treatment of central nervous system (CNS) diseases associated with BBB breakdown [73]. A recent study has shown that the middle cerebral artery occlusion middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model in zebrafish leads to ferroptosis of BECs, accompanied by lipid peroxidation, increased iron concentration, and decreased expression of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) and GPX4, indicating that ferroptosis of endothelial cells is a potential pathogenic mechanism for IS [74].

Ferroportin 1 (FPN1) is the sole identified iron export protein located in brain endothelial cells, serving as a crucial molecule that facilitates the transfer of iron from the bloodstream into the brain [75]. Specific knockdown of FPN1 in ECs was found to produce differential effects in the acute and recovery phases of IS. In the acute phase of IS, the knockout of FPN1 in endothelial cells results in a decrease in brain iron accumulation, which subsequently alleviates oxidative stress and the inflammatory response. This reduction in oxidative and inflammatory processes leads to a decrease in ferroptosis and apoptosis, ultimately resulting in a reduction of cerebral infarct volume and an improvement in neurological function. Conversely, the knockout of FPN1 in recovering brain endothelial cells significantly hinders the restoration of neurological function following IS. This impairment occurs due to increased brain iron accumulation, promotion of gliosis, and suppression of neural stem cell migration and differentiation. Iron restriction plays a neuroprotective role in the acute phase of IS and an inhibition of the recovery phase [41].

The heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) pathway apparently may be overexpressed, which may lessen ferroptosis [76]. According to other research, ferroptosis is significantly aided by HO-1 overexpression, which contributes to the rise in the labile iron pool [77, 78]. HO-1 and transferrin receptor protein 1 (TFR1) are thought to have a role in cellular adaptation processes, iron homeostasis, and oxidative stress in the brain [79]. It is possible to ameliorate cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting HO-1 [80]. Its function in acute damage may be influenced by HO-1 expression level. According to these findings, ischemia/reperfusion and hyperglycaemia (HG) cause increased HO-1 production in endothelium, which leads to ferroptosis and the progression of BBB damage both in vitro and in vivo. However, purinergic receptor P2X7 (P2RX7) blockade can reverse this process. These findings shown that P2RX7 blocking has a significant role in ferroptosis pathways and can control SLC7A11/GPX4 via inhibiting the extracellular-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and p53 pathway [81].

Cerebral ischemia can cause ferroptosis, which exacerbates the damage caused by cerebral ischemia. By inhibiting ferroptosis, this ischemia harm is lessened. Iron overload and the regulatory mechanisms of GPX4 and 12/15 lipoxygenases (LOX) upstream remain to be further investigated, as do the regulatory processes involved in brain ferroptosis.

Autophagy is a self-eating process that occurs in a variety of cells, including neurons, glia cells, and brain microvessel cells (BMVECs), and it is involved in maintaining cellular homeostasis and proper cellular functions [82, 83]. After cerebral ischemia, endothelial autophagy activation restores and preserves BBB integrity, which reduces brain edema and prevents stroke [84, 85].

A recent study has shown that oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/R)-mediated upregulation of circ-forkhead box O3 (FOXO3) in cerebral endothelial cells promotes autophagy. Knockdown of circ-FOXO3 can inhibit autophagy and enhance the permeability of endothelial cells. Circ-FOXO3 plays a protective role against OGD/R-induced endothelial cell injury in an autophagy-dependent manner [86].

Furthermore, occludin degradation is mediated by ischemia-induced autophagy, and BBB dysfunction is lessened and occludin degradation is restored by 3-methyladenine (3-MA)-induced autophagy inhibition [87]. Additionally, in BECs exposed to OGD, autophagic lysosomal activation degrades claudin-5 [88], and in mice lacking the p50 gene, autophagic activation was linked to BBB damage [89], indicating a potential role for autophagy in ischemia neuronal and vascular injury.

In contrast to these findings, recent reports have highlighted the protective role of body BECs in autophagy and their involvement in BBB dysfunction during I/R injury [90]. In their investigation, they found that whereas pretreatment with 3-MA inhibited autophagy and increased I/R-induced BBB damage, activation of the autophagic process with the autophagy induce rapamycin and lithium carbonate dramatically reversed BBB disruption following I/R injury. In their investigation, the scientists came to the conclusion that autophagy prevented cells from producing reactive oxygen species and restored lower levels of ZO-1, despite the fact that no particular biological targets of activated autophagy were found.

Thus, autophagy after cerebral ischemia increases cerebral endothelial permeability, and this permeability can be reduced by the inhibition of autophagy. These findings enhance our comprehensive understanding of the role that autophagy plays in the dysfunction of the BBB following ischemic events.

In addition to the aforementioned types, programmed cell death encompasses parthanatos, entotic cell death, alkalosis-induced cell death, oxygen ptosis, autophagy-dependent cell death, reticulocyte death, and lysosome-dependent cell death.

Parthanatos is a kind of planned cell death that requires polymerase 1 (PARP-1) (ADP-ribosome) [91, 92]. Poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) accumulates as a result of PARP-1 overactivation following after substantial DNA damage [93]. Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) is released when PAR is translocated from the nucleus to the mitochondria. AIF forms a complex with macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) within the cytoplasm after its release from the mitochondria. The translocation of the AIF/MIF complex into the nucleus leads to chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation, ultimately culminating in cell death [94, 95]. Neurodegenerative illnesses and other conditions associated with DNA damage may be affected by the interplay between this type of dependent cell death and other types of dependent cell death, such as necroptosis.

Autophagy-dependent cell death is a kind of programmed cell death driven by the molecular mechanism of autophagy [96]. Researches believe that ferroptosis is an autophagy-dependent cell death through a complex feedback loop, this provides new ideas for the study of autophagy-dependent cell death in endothelial cells [97].

Lysosome-dependent cell death (LCD), is a form of regulatory cell death mediated by iron translocation caused by lysosomal components or lysosomal membrane permeabilization in order to amplify or initiate cell death during apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis [98]. However, the research on lysosome-dependent cell death in BECs still needs to be expanded.

In conclusion, there are various forms of endothelial cell death after stroke, but the research investigation shows that apoptosis is the main form of endothelial cell death after stroke [99], and the research progress on alleviating endothelial cell apoptosis should be further strengthened.

Research has uncovered a previously unrecognized function of myeloid-derived MIF (macrophage migration inhibitory factor) in facilitating apoptosis and necrosis in cerebrovascular endothelial cells (ECs) through the activation of RIPK1 (receptor interacting protein kinase 1). In a clinically relevant model of postischemic syndrome (PIS), it was demonstrated that surgical trauma-induced aseptic inflammation can enhance MIF expression. Moreover, MIF has been shown to serve as a potent trigger for the death of cerebrovascular ECs and the disruption of the BBB following ischemic brain injury. By integrating both genetic and pharmacological evidence, it is suggested that targeting the release of myeloid MIF or inhibiting RIPK1 activation may confer protective effects on cerebrovascular ECs and the BBB in the context of ischemic brain injury [53].

In addition, Microglia are macrophages in the brain, which are considered to be the sentinel of neuroinflammatory response caused by different brain injuries [100]. Therefore, the regulatory effect of microglia in central nervous system diseases has received extensive attention. Microglia is one of the important components of the neurovascular unit, which plays a coordinated role with other cell types. Acute or subacute cerebral ischemic injury, which is common in the brain, will destroy the cerebral microvasculature and lead to subsequent inflammatory response, accompanied by aggravated neuronal damage and activation of microglia [101].

Microglial activation can be detected at different stages of the pathological process of stroke. Liang et al. [102] verified that chemokine ligand receptor CX3CL1-CX3CR1 signaling is involved in basal intercellular communication for microglial chemotaxis and activation [103]. This study reveals that there exist various categories of cell signaling cascades between neurons, microglia and brain microvascular cells. The mechanism of bidirectional regulation of microglia in neurovascular coupling is an important molecular event that needs to be clarified urgently, which will provide key ideas for clinical treatment. In addition, pericytes act as vascular smooth muscle in brain capillaries. Some pericytes respond to vasoactive signals generated by the brain by contracting, thereby affecting capillary diameter [104].

Pericytes are essential in establishing and maintaining vascular structure and BBB function. Pericyte depletion has been found in both acute and chronic CNS diseases, with rapid apoptosis following IS and traumatic brain injury (TBI). This study has reported the behavior of pericyte series changes at different stages of ischemic stroke [105]. In the acute phase of stroke, pericytes shrink to clog capillaries and cause no-return of blood. Interestingly, however, pericytes subsequently have proinflammatory and immunomodulatory effects, stabilizing the BBB and protecting the brain parenchyma by protecting endothelial cells on the lateral side of the lumen and releasing neurotrophin. In addition, pericytes have neuroprotective activity and promote angiogenesis and neuronal growth during the post-stroke recovery phase. It is evident that pericytes play multiple intervening roles in the complex process of ischemia-reperfusion injury and repair in response to the dynamic changes of endothelial cells and neurons.

Although there are still few therapeutic options for stroke, recanalization therapy involving medication and mechanical thrombolysis have shown some beneficial effects in people recover from IS. Therapeutic medicines for neuroprotection in acute IS are still needed in order to avoid brain damage before and after recanalization, to extend the therapeutic window for intervention, and to improve functional outcome.

The existing literature clearly indicates that numerous therapeutic agents have undergone testing in clinical trials or are actively being assessed in preclinical studies to determine their efficacy in acute ischemic stroke (IS) [106, 107, 108]. However, despite these extensive endeavors, the identification of clinically effective neuroprotective agents continues to be a challenging pursuit. However, these studies lay the foundation for future treatment of IS with neuroprotective BECs. In recent years, several compounds targeting the inhibition of BEC-death signals have been used in IS experiments.

Dichloroacetic acid (DCA) is a small molecule that has been employed as a therapeutic agent for various genetic mitochondrial disorders [98]. Research has demonstrated that DCA may mitigate the detrimental effects of cerebral ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) by decreasing infarct volume, improving neurological scores, and reducing brain water content. Furthermore, DCA treatment has been found to diminish the impact of OGD on mitochondrial metabolism, BBB permeability, and oxidative stress in human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMEC) [109].

Medioresinol, a natural product [110], is a novel PGC-1

Ergothioneine is a naturally occurring antioxidant. Research has demonstrated that ergothioneine can cross the blood-brain barrier and function as a cytoprotective and antioxidant agent, making it a viable treatment option for neurodegenerative diseases in which oxidative stress is frequently the driving force behind disease progression [111]. A study has also shown that ergothioneine can attenuate the apoptosis of brain endothelial cells caused by the accumulation of 7-ketocholesterol, and can treat neurovascular diseases by reducing the damage to brain endothelial cells [112].

Cardamonin is a chalcone with neuroprotective activity [113]. Previous research has indicated that cardamonin has a protective effect against apoptosis induced by adriamycin or lipopolysaccharide in cardiac cells [114]. More significantly, it has been observed to reduce oxidative-stress-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells [115]. Recent research has additionally demonstrated that cardamonin can reduce OGD/R-induced increased cerebral endothelial-cell permeability, apoptosis, and brain damage in mice with MCAO by activating the HIF-1

A significant traditional Chinese medicinal herb is Scutellaria baicalensis [117]. One of the primary bioactive ingredients in Scutellaria baicalensis extract is baicalin. Reported pharmaceutical qualities of baicalin include anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, anti-diabetic, anti-cancer, cardioprotective, liver-protective, and neuroprotective effects [118]. The BBB can be shielded from a lipopolysaccharide challenge by baicalin administration. Inhibition of the generation of ROS by the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) antioxidant pathway, and BBB endothelial cell inflammatory response, can influence this process [119]. These results suggest that baicalin has a strong protective effect against brain damage caused by lipopolysaccharide, which offers a therapeutic treatment alternative.

Panax notoginseng saponins (PNS) have gained widespread application in the treatment of ischemic stroke (IS) and cardiovascular diseases within China [120]. PNS seems to possess a multitude of pharmacological actions, including anti-thromboembolism, anti-inflammation, anti-apoptosis, hemostasis, cerebral vasodilatation, anticoagulation, anti-hyperglycemia, and anti-hyperlipidemia effects [121]. According to an earlier study, PNS can reduce the degradation of ZO-1 and claudin-5 tight-junction proteins by antioxidant activation of Nrf2 antioxidant signaling through the PI3K/Akt pathway and prevent OGD/R-induced BBB integrity degradation in vitro [122].

Protocatechuic aldehyde (PCA) is a hydrophilic phenolic compound that is extracted from the dried roots of the traditional Chinese herb, sage [123]. Numerous investigations have verified that PCA reduces the inflammatory damage to endothelial cells, preserving endothelial cell function [124]. Recent research has demonstrated that PCA reverses brain endothelial cell pyroptosis via lncRNA Xist, which strongly enhances the protective effect of PCA on IS [67].

Caffeic acid, as a natural bioactive phenolic acid, has been tested for its potential antioxidant properties [125]. Vegetables, fruits, and coffee are high in caffeic acid. According to earlier research, caffeic acid helped rat brain damage during cerebral I/R [126]. According to recent research, in the brain of the MCAO rat, caffeic acid suppresses oxidative stress-mediated neuronal death, regulates ferroptosis, upregulates glutathione production through the Nrf2 signaling pathway, and downregulates transferrin receptor protein 1 (TFR1) and acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 (ACSL4). Caffeic acid has been proposed as a possible treatment to lessen brain damage after cerebral ischemia [127].

PBT434 methanesulfonate is a potent and orally active

3-MA is a mature autophagy inhibitor. A study has shown that 3-MA helps to enhance the cell viability of brain endothelial cells by inhibiting autophagy, and reduces the level of occludin and the cell hyperpermeability induced by glucose and oxygen deprivation [130]. In addition, 3-MA administration significantly reduced the I/C values increased by Evans blue in an in vivo study [131].

Icariin (icariside II - ICS II) Icariin, also known as icariside II (ICS II), is one of the primary active components derived from Epimedium, a Traditional Chinese Medicine widely employed in the treatment of various clinical conditions such as dementia, erectile dysfunction, and cardiovascular diseases [132]. ICS II is recognized for its antioxidant properties and demonstrated neuroprotective effects [133]. According to recent research, ICS II both inactivates glycogen synthase kinase-3

| Drugs or compounds | Mechanism of action | Effects | Type of research |

| DCA | Inhibition of PDK2 activates PDH, thereby activating Nrf2 and reducing oxidative stress. | Apoptosis [109] | preclinical |

| PNS | Increased Akt phosphorylation, nuclear Nrf2 activity, and downstream antioxidant enzyme HO-1 expression. | Apoptosis [122] | preclinical |

| Ergothioneine | Significantly reduced the proinflammatory genes IL-1 | Apoptosis [111] | preclinical |

| Baicalin | It increased the expression of Nrf2, HO-1, and NQO1, reduced the generation of ROS and MDA, and encouraged the creation of SOD. | Apoptosis [119] | preclinical |

| Cardamonin | MACO-induced brain damage and OGD/R-induced HBMEC damage are avoided when the HIF-1 | Apoptosis [116] | preclinical |

| PCA | Decreased the expression of NIMA-associated kinase 7, GSDMD, Caspase-1, IL-1 | Pyroptosis [124] | preclinical |

| Medioresinol | Pyroptosis, mtROS, and the expression of associated proteins (NLRP3, ASC, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1 | Pyroptosis [66] | preclinical |

| Caffeic acid | To withstand ferroptosis, TFR1 and ACSL4 were downregulated, and glutathione synthesis was increased via the Nrf2 signaling pathway. | Ferroptosis [127] | preclinical |

| PBT434 | Increased in the abundance of the transcripts for TfR and ceruloplasmin | Ferroptosis [129] | preclinical |

| 3-MA | Inhibition of autophagy reversed occludin degradation and attenuated BBB dysfunction | Autophagy. [131] | preclinical |

| Cariside II | To reduce damage caused by cerebral I/R by disrupting the PKG/GSK-3 | Autophagy [134] | preclinical |

Abbreviations: DCA, dichloroacetic acid; PNS, panax notoginseng saponins; ET, ergothionein; PCA, protocatechuic aldehyde; MDN, medioresinol; 3-MA, 3-Methyladenine; PDK2, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 2; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; TNF

IS is a prevalent and often fatal disease globally, yet the precise pathogenic mechanism remains elusive despite advancements in experimental and clinical research. Endothelial cell dysfunction, a key element of the blood-brain barrier, is intricately linked to the development of IS. Although some headway has been made in identifying specific targets for endothelial cell death through experimental studies, the efficacy of therapeutic drugs in treating ischemic stroke remains uncertain due to variations between experimental models and actual clinical cases. Numerous challenges persist in the development of novel and precise models, as well as more efficient treatment modalities. Nevertheless, opportunities for advancement in disease research remain abundant, particularly in the investigation of endothelial-cell-death mechanisms which may inform the development of synergistic therapies involving other neural cells. Consequently, elucidating the mechanisms underlying endothelial cell death serves as a crucial step in the advancement of therapeutic strategies for IS.

HRY and HH jointly designed and conceived the article and made revisions to the important intellectual content of the paper. QWM and QBL collected the references, made the figures and tables, made the final revisions to the version to be published and agreed to take responsibility for all aspects of the research work to ensure that any issues related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the paper are properly investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance and instruction from Dr Qingyun Guo of the Hainan Medical University for Hongru Yi.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 82460709], and High-level Talent Project of Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation [No. 823RC582]. Hainan Provincial Tropical Drug Innovation and Transformation Engineering Research Center Hospital Matching Fund.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.