1 Department of Pharmacology & Toxicology, College of Pharmacy, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, 11942 Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, College of Pharmacy, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, 11942 Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the effects of selected phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors (PDE-4 inhibitors)—roflumilast, ibudilast, and crisaborole—on the activity of blood coagulation factor XII (FXII). In the intrinsic coagulation pathway, FXII is known to initiate the kallikrein–kinin system (KKS), causing an increase in the system expression, which ultimately leads to inflammation and coagulation states. Additionally, the activation of KKS downstream effectors leads to inflammation. Inflammation signaling was found to be initiated when the bradykinin (BK) protein binds to its B2 receptor because of the FXII-dependent pathway activation. BK abnormalities can cause a critical condition, hereditary angioedema (HAE), which is characterized by recurring serious swelling. While it is considered unnecessary for hemostasis, FXII is an important enzyme for pathogenic thrombosis. Because of this special characteristic, FXII is a desirable therapeutic target. Our hypothesis is to identify the inhibitory effects of roflumilast, ibudilast, and crisaborole on the activated FXII and to reveal their beneficial impacts in the reduction of the pathogenesis of FXII-related conditions, HAE, and thrombosis. In a current study, we presented the inhibitory effect of tested drugs on the main target activated factor XII (FXIIa) as well as two other plasma protease enzymes included in the target pathway, plasma kallikrein and FXIa.

To achieve our aim, in vitro chromogenic enzymatic assays were utilized to assess the inhibitory effects of these drugs by monitoring the amount of para-nitroaniline (pNA) chromophore released from the substrate of FXIIa, FXIa, or plasma kallikrein.

Our study findings exhibited that among assessed PDE-4 inhibitor drugs, roflumilast at micromolar concentrations significantly inhibited FXIIa in a dose-dependent manner. The FXIIa was clearly suppressed by roflumilast, but not the other related KKS members, plasma kallikrein, or the activated factor XI. On the other hand, ibudilast and crisaborole showed no inhibitory effects on the activities of all enzymes.

Overall, roflumilast could be used as a lead compound for developing a novel multifunctional therapeutic drug used for the prevention of HAE or thrombotic disorders.

Keywords

- blood coagulation

- factor XIIa

- PDE-4 inhibitors

- roflumilast

- in vitro

- in silico

The multifunctional coagulation factor XII (aka Hageman factor, FXII) is the plasma proenzyme that gives rise to the serine protease FXIIa under enzymatic activation. FXII is synthesized and released by the liver [1, 2]. FXII is the product of a single 12kb gene (F12) that is composed of 13 introns and 14 exons and mapped on the human chromosome 5 [3]. The FXII zymogen is made up of a disulfide bond that connects a heavy chain (353 residues) and a light chain (243 residues). FXII is made up of several structural domains. Starting from the N-terminus, the domains are as follows: a leader peptide, a fibronectin type II, an epidermal growth factor-like (EGF-like) domain, a proline-rich region, and the catalytic domain [4]. FXII can give rise to two different molecular fragments, including alpha FXIIa (

Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors (PDE-4 inhibitors) have anti-inflammatory and vasodilator pharmacological activities, suggesting beneficial effects in the management of stroke and cardiovascular diseases [11]. According to a meta-analysis study, clinical use of PDE4 inhibitor, roflumilast, showed a significant reduction in the cardiovascular events appearing in patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [12]. Additionally, roflumilast decreases the ability of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocytes to conduct their prothrombotic functions [13]. It is reported that using ibudilast in combination with triflusal increases the inhibitory effects on platelet aggregation as well as blood coagulation [14]. In the preclinical study, the anticoagulant efficacy of FXIIa and FXIa inhibitors was promising compared to commonly used anticoagulants. In addition, FXIIa and FXIa inhibitors exhibited less bleeding risk than available anticoagulants [15]. It is also indicated that FXII and plasma prekallikrein reciprocally activate each other in the pathway of liberating bradykinin. Recently, the need to develop an anticoagulant with minimal bleeding side effects inspired researchers in the field to focus on FXIIa and FXIa inhibitors as next-generation anticoagulants [16].

We hypothesized that PDE-4 inhibitors roflumilast, ibudilast, and crisaborole would show an inhibitory effect on the activity of the human blood-activated coagulation factor XII and could result in a potential positive impact on the FXIIa-driven coagulation in thromboembolic disorders and COPD-associated chronic inflammation. To address this hypothesis, we determined the inhibitory effects of these drugs on the activity of FXIIa and the FXIIa specificity of any active drug over FXIa and kallikrein, other components of the coagulation system, and the kallikrein–kinin system (KKS). In addition, we also utilized in silico studies, including molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies, to show the FXII/active drug intermolecular interactions and to understand the binding flexibility of the docked drug ligand in the active site of the catalytic domain of FXII.

Human

This experiment’s objective was to ascertain whether roflumilast, ibudilast, and/or crisaborole have any influence on FXIIa. In combination with 0.5 mM S2302, 9 nM of activated FXII was utilized. The enzyme FXIIa and the substrate S2302 controls were utilized as baseline comparisons for the variable that was being investigated. The FXIIa control sample solely included FXIIa, a HEPES buffer with a pH of 7.1, and S2302. The components of the S2302 negative control were the HEPES buffer and the appropriate substrate. Experimental concentrations of drugs used in the study were 1, 3, 10, 30, 300, and 1000 µM. After the addition of the HEPES bicarbonate buffer with a pH of 7.1, the total volume of each mixture was 330 µL. The substrate was the final component to be added, and it was conducted in a timely and effective manner. After that, we pipetted the fluid in and out of each tube to thoroughly combine it. An assay plate had measurements of 100 mL taken from the sample, and those measurements were put into triplicate wells. At a temperature of 37 degrees Celsius, the plate was then incubated for 1 h. The rate of FXIIa inhibition by drugs was determined by measuring the change in absorbance at an optical density reading of 405 nm [17]. Data were collected in triplicate from 3 to 4 separate experiments.

A chromogenic assay was used in the presence of FXIa and kallikrein to assess the action of roflumilast, which is a new molecular inhibitor of the plasma FXIIa enzyme. We also assessed the effects of other PDE4 inhibitors, ibudilast, and crisaborole on the same enzymes for comparison. When not in use, enzymes and peptides were stored on ice to ensure a suitable condition during the assay. Activation may occur earlier than necessary if they are allowed to reach room temperature. In addition, sterile pipette tips were used for all assays to avoid any contamination. The chromogenic substrate S-2302, which is known to be selective for kallikrein, was incubated with 2 nM kallikrein in these assays. S-2302 (0.5 mM) is hydrolyzed by kallikrein. A peptide bond that once connected arginine and para-nitroaniline (pNA) is broken during this process. The formation of pNA is responsible for the yellowing of the mixture color. A darker solution implies that kallikrein is hydrolyzing a greater portion of the substrate (S2302) than is previously thought. FXIa was evaluated in the same manner, with 0.5 mM S2366 being used for the analysis. A total volume of 330 µL was used to incubate plasma proteins with their corresponding enzyme in either the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of roflumilast, ibudilast, and crisaborole. In every experiment, the settings for the incubation were kept at the same level: 37 degrees Celsius for one hour. At an optical density of 405 nm, the shift in absorbance was determined by monitoring the synthesis of free para-nitroaniline using a BioTek ELx800 Absorbance Microplate Reader (Marshall Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA) [17].

The X-ray 3D structure of human coagulation factor XII protease domain 2.40 Å resolution was retrieved from a protein data bank (PDB) (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/4XE4; accession number PDB ID: 4XE4). The protein’s structure was cleaned, and co-crystaled water molecules were removed using saved in PDB format using the Discovery Studio program (Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA, San Diego, CA, USA) [18].

Autodock Tools v1.5.6 (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) was utilized to convert the structures of receptors and ligands into autodock pdbqt files, which contain the atomic charges and atom type definitions. The grid box was centered to ensure full coverage of the amino acid residues involved in the topology of the active site [19]. The 3D structure of roflumilast (PubChem CID: 449193) was downloaded from PubChem (available online https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Autodock vina v1.1.2 (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to run the molecular docking, and the resulting multiple conformations of docked ligand in the deglycosylated catalytic domain of factor XII (PDB: 4XE4) were ranked based on the binding energy score [20]. The analysis of ligand conformations was visualized in PyMol v2.5 (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, USA) and Discovery Studio Visualizer [21].

The MD simulations for ligand complexes were run using the Groningen machine for chemical simulations (GROMACS) package v2018.1 [Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Stockholm, Sweden] as previously reported [22, 23]. The complex of roflumilast with the deglycosylated catalytic domain of factor XII was simulated by applying the OPLS-AA all-atom force field in the presence of the TIP3P water model. The topological parameters for roflumilast were generated by the SwissParam web service (https://old.swissparam.ch/ (Accessed on 11 January 2025)). The complex was solvated in a cubic box with a spacing of 1 nm from the complex. The system was neutralized with 150 mM of NaCl salt as counter ions. To reduce the energy of the simulated system, the steepest descent algorithm technique (SDAT) was applied. A maximum step size of 0.01 nm was used for the 1000 kJ/mol/nm simulated tolerance. The bond length constraints were adjusted using the Linear Constraint Solver technique (LINCS). The particle mesh Ewald (PME) method was considered for electrostatic calculations. NVT (where number of particles (N), system volume (V) and temperature (T) are constant) and NPT (where number of particles (N), system pressure (P) and temperature (T) are constant) canonical ensembles were applied for 100 ps equilibration. MD simulation was completed for 100 ns, and results were analyzed by the GROMACS 2018.1 package toolkit.

Data were collected in triplicate from three to four separate experiments. At least three times in duplicate or triplicate, experiments were carried out. GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used to evaluate the mean

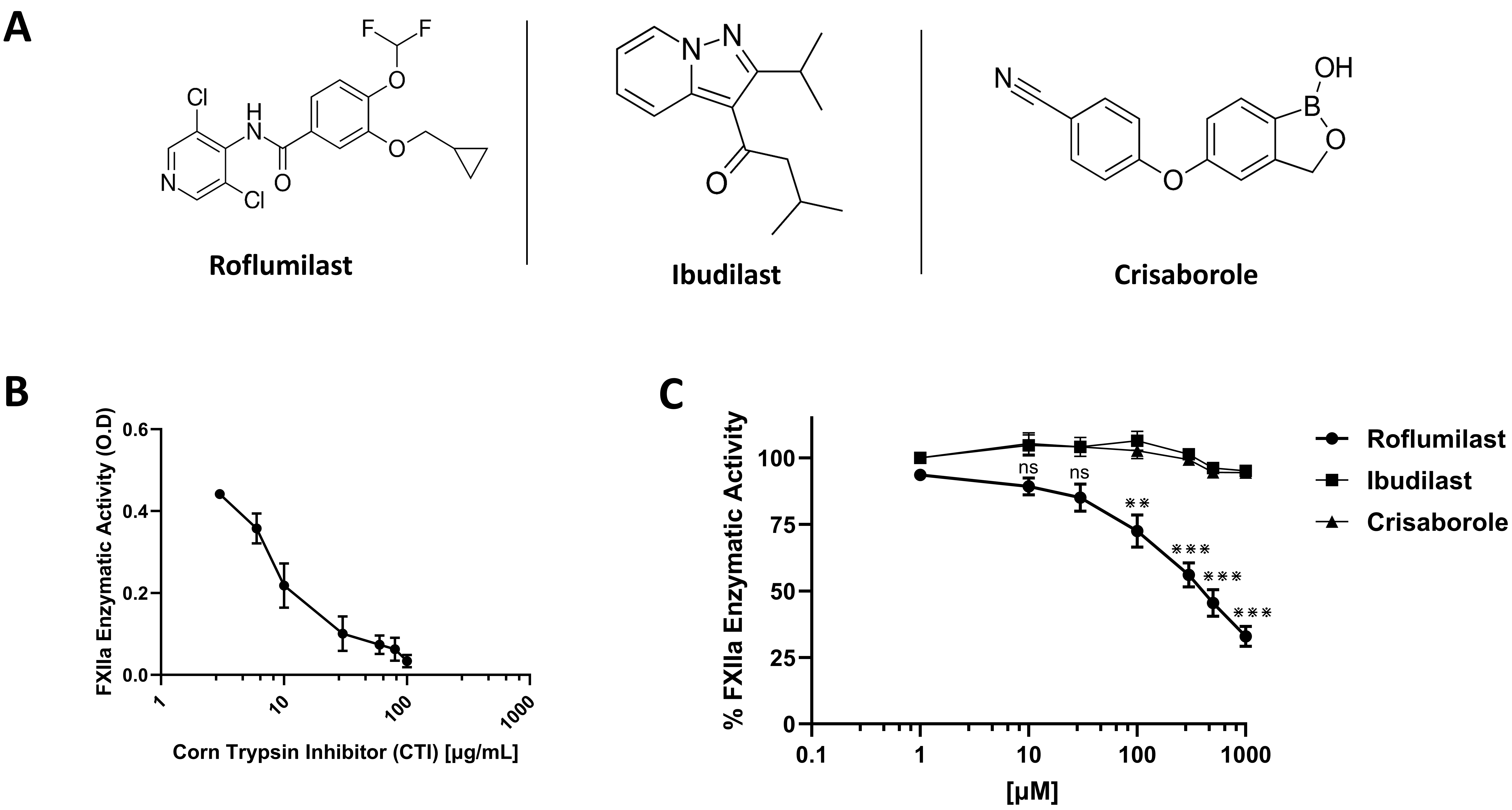

Chemical structures of PDE-4 inhibitors roflumilast, ibudilast, and crisaborole were shown in Fig. 1A. To assess their effects on FXIIa, four independent chromogenic assays were performed in triplicate with a concentration range (1 µM–1000 µM). FXIIa inhibitor, corn trypsin inhibitor, was used as reference inhibitor (Fig. 1B). The ability of FXIIa to hydrolyze S2302 was found to be influenced only by roflumilast. Results exhibited that roflumilast significantly inhibited the activity of FXIIa enzyme in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). At the concentrations of 500 and 1000 µM, FXIIa enzyme was able to hydrolyze 44.77% and 33.27% of the S2302 substrate, respectively, in comparison to the controlled S2302 condition with no protease enzyme included. As may be observed in Fig. 1C, these data demonstrated significant inhibitory effects on FXIIa. The statistical analysis indicated that the IC50 for the roflumilast inhibitory effects on FXIIa is 471.96 µM. At the highest used concentration (1000 µM), roflumilast was able to block FXIIa activity by 65% compared to the control group. The efficacy of inhibitory roflumilast at 100% activity was evaluated using the value of the control for the FXIIa protease enzyme as a baseline comparison.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Effects on human blood coagulation activated factor XII (FXII) (FXIIa). (A) Chemical structures of roflumilast, ibudilast, and crisaborole. (B) Effect of CTI on FXIIa activity. FXIIa incubated in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of CTI (1–100 µg/mL). (C) Effects of roflumilast, ibudilast, and crisaborole on FXIIa activity. Varying concentrations (1–1000 µM) of drugs were incubated with S2302 (0.5 mM). FXIIa activity was measured by monitoring the rate of S2302 hydrolysis. For all panels, results are represented as % mean

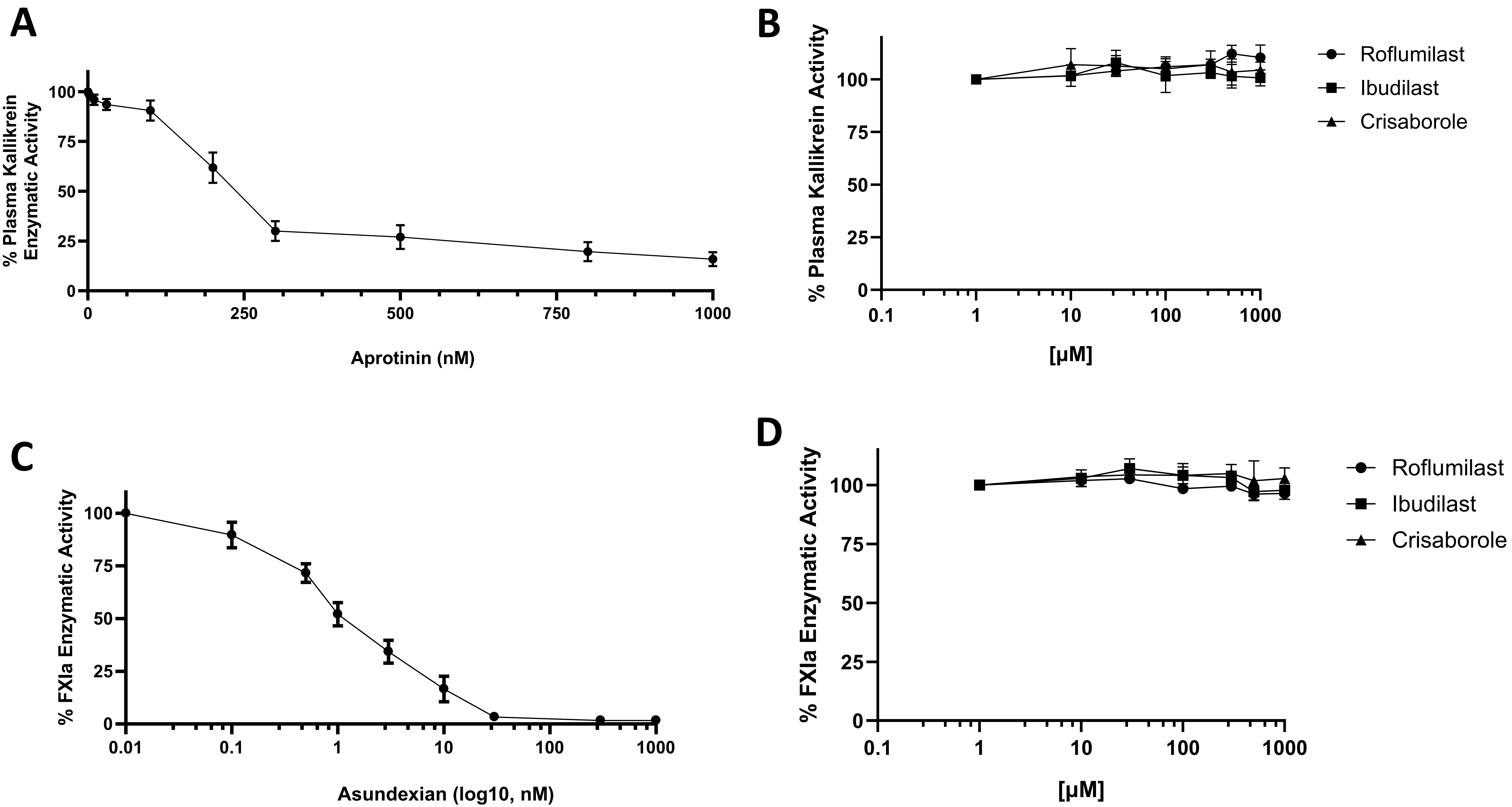

Thereafter, the specificity of roflumilast for FXIIa was examined by employing two additional proteases derived from the KKS: kallikrein, and FXIa. It has been reported that aprotinin was able to inhibit plasma kallikrein activities dose-dependently. Thus, aprotinin can be used as reference inhibitor for plasma kallikrein enzyme and to make sure both enzyme essays are working properly during our studies (Fig. 2A). Three independent assays for the activity of plasma kallikrein showed that roflumilast has no inhibitory effects on plasma kallikrein enzyme (Fig. 2B). The well-known FXIa inhibitor, asundexian was used as a reference inhibitor for FXIa enzyme (Fig. 2C). Three independent assays for the activity of FXIa showed that roflumilast has no inhibitory effects on FXIa enzyme (Fig. 2D). The plasma kallikrein and FXIa enzymes were not inhibited by other PDE4 inhibitors (Fig. 2B,D). Taken together, roflumilast was able to inhibit FXIIa activity and showed specificity for FXIIa over the other proteases from the KKS.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Effects on human plasma kallikrein and human blood coagulation activated FXI (FXIa). (A) Effect of aprotinin inhibitor on plasma kallikrein activity. Plasma kallikrein incubated in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of aprotinin inhibitor (1–1000 nM). (B) Effects of roflumilast, ibudilast, and crisaborole on plasma kallikrein activity. Varying concentrations of drugs (1–1000 µM) were incubated with S2302 (0.5 mM). Plasma kallikrein activity was measured by monitoring the rate of S2302 hydrolysis. (C) Effect of asundexian inhibitor on FXIa activity. FXIa incubated in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of aprotinin inhibitor (1–1000 nM). (D) Effects of roflumilast, ibudilast, and crisaborole on FXIa activity. Varying concentrations of drugs (1–1000 µM) were incubated with S2366 (0.5 mM). FXIa activity was measured by monitoring the rate of S2366 hydrolysis. For all panels, results are represented as % mean

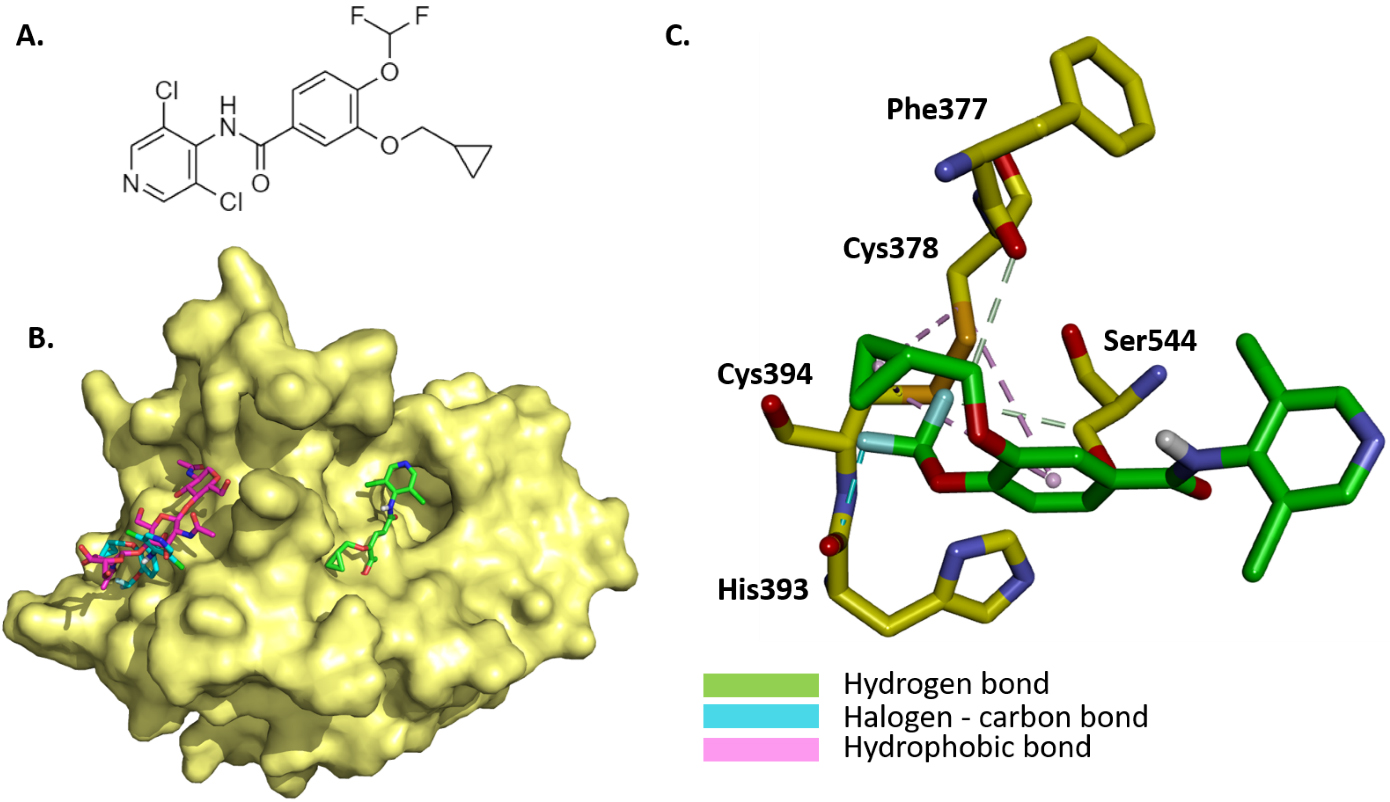

The binding mode and molecular interaction between roflumilast (Fig. 3A) and coagulation factor XII protease domain crystal structure (PDB: 4XE4) were explored using the Autodock Vina program. The active catalytic domain of factor XII is composed of two possible binding sites, namely, the active site, which contains the protease catalytic triad, as well as the glycosylated site of the catalytic protease domain. Here, the docking was performed at both sites (Fig. 3B). As the glycosylated site appears as a surface-exposed site, the binding of roflumilast to the active site was stronger (–7.26 kcal/mol) than the binding to the glycosylated site (–4.836 kcal/mol). The interaction mechanism between roflumilast and nearby residues within the active site was determined. The cyclopropane and benzene rings interact with Cys378 and Cys394 through PI Alkyl hydrophobic bonds. The fluoride atom is involved in halogen–carbon bonds with His393. The methoxy group and the second fluoride group interact with Phe377 and Ser544 through carbon–hydrogen bonds (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Illustration of the binding mode and interaction mechanism of roflumilast with coagulation factor XII protease domain crystal structure. (A) 2D structure of roflumilast. (B) Binding mode of roflumilast to active site and glycosylated site within the catalytic domain of factor XII (yellow, PDB: 4XE4), roflumilast (green) binding to active site of catalytic domain of factor XII, and roflumilast (magenta) binding to glycosylated site and superposed with triacetyl-beta-chitotriose in the glycosylated site. (C) Molecular interactions between docked roflumilast (green) and interacting residues within the active site of the catalytic domain of factor XII.

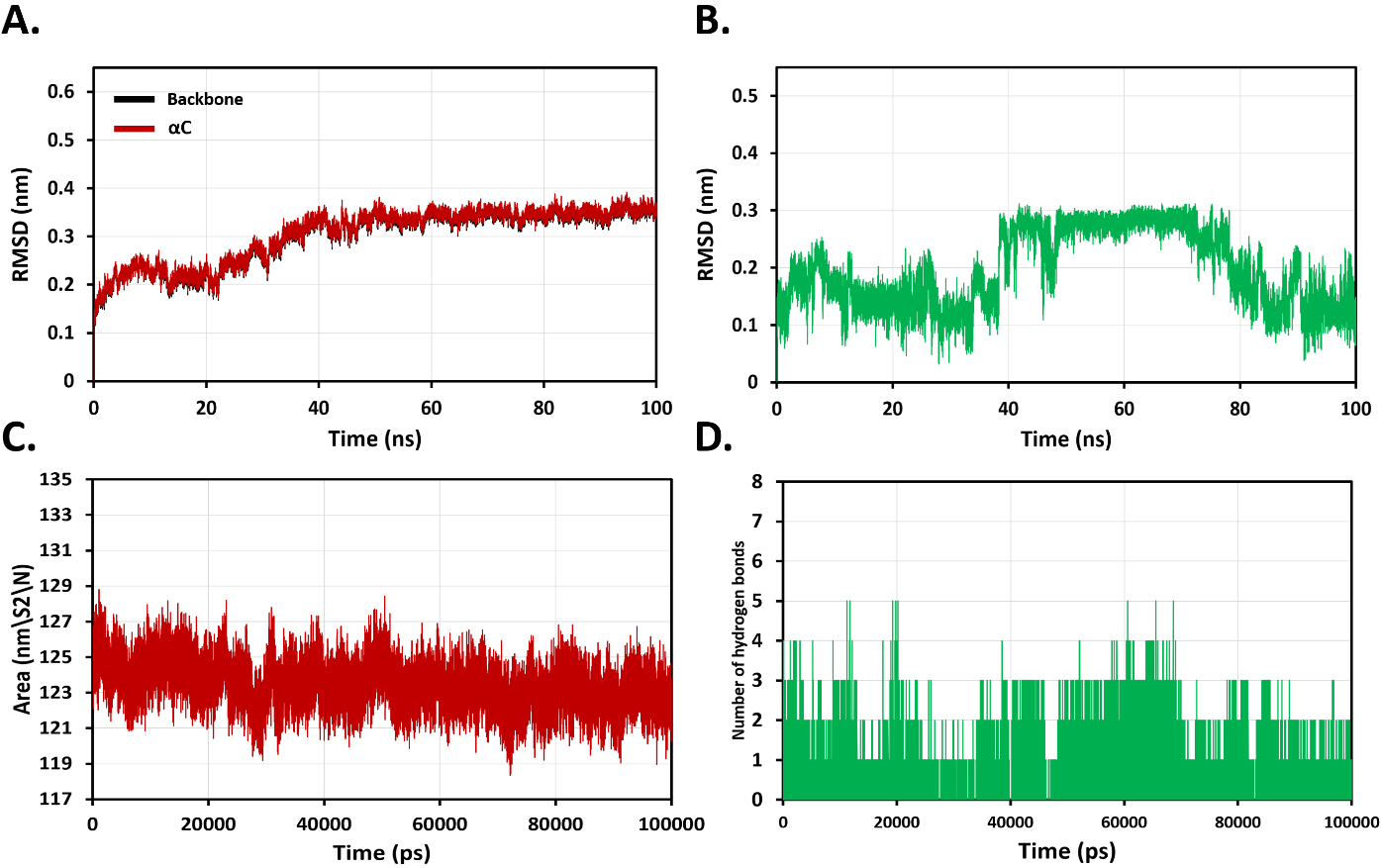

Next, 100-nanosecond (ns) molecular dynamics simulations were carried out to understand the binding flexibility of docked roflumilast in the active site of the catalytic domain of factor XII. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) profiles of backbone and

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Analysis of molecular dynamics (MD) simulation plots for evaluation of overall stability of binding roflumilast with coagulation factor XII protease domain at 100 ns. (A) Root mean square deviation (RMSD) profiles of backbone and

Thrombotic diseases have a significant impact on world health, as they are the main cause of death and disability. The improper regulation of hemostasis, a key system that maintains perfusion and prevents blood loss due to vascular injury, is the primary cause of many diseases. The primary molecular result of hemostasis activation is the creation of thrombin, an enzyme capable of catalyzing the conversion of fibrinogen, a soluble protein, into fibrin, an insoluble protein, which serves as the clot’s basis. FXIIa is an active serine protease enzyme that contributes to pathophysiological thromboembolism. Recently, FXIIa has gained great attention as a promising target for the discovery and development of new anticoagulants with a lower risk of bleeding. Moreover, it has been previously reported that the pharmacological inhibition of the FXII/FXIIa approach would interfere with thromboembolic conditions and FXII-associated inflammatory diseases in animal models [15, 16].

Since 2011, the FDA has authorized roflumilast as an anti-inflammatory medication for a variety of respiratory diseases, most notably COPD and asthma. Currently, roflumilast has been indicated to have various pharmacological actions, including not only anti-inflammatory but also anti-thrombosis, anti-fibrotic, and reduction in inflammatory sepsis [24, 25, 26, 27]. For detecting its anticoagulant activity, roflumilast was tested in an amidolytic assay against the FXIIa enzyme. Corn trypsin inhibitor (CTI), a well-characterized potent small-protein inhibitor of FXIIa, was used in this study as the reference inhibitor. Roflumilast’s IUPAC name is 3-(Cyclopropylmethoxy)-N-(3,5-dichloropyridin-4-yl)-4-(difluoromethoxy) benzamide with molecular formula C17H14Cl2F2N2O3 and molar mass of 403.207 g/mol.

FXIa, FXIIa, and plasma kallikrein, components of the coagulation contact system, seem to play a role in thrombosis while having a minor function in hemostasis. FXIa and plasma kallikrein share several similarities and interactions within the coagulation and contact activation systems: Both FXIa and plasma kallikrein are serine proteases that are essential in the initial stages of blood clotting [28]. In terms of their physiological roles, both FXIa and PK contribute to coagulation and inflammation. Additionally, FXI and prekallikrein circulate in the plasma as a complex with high-molecular-weight kininogen (HK) in which HK anchors prekallikrein and factor XI to surfaces, thereby facilitating their conversion into the active forms: plasma kallikrein and FXIa. In general, FXIa and PK share genetic, structural, and functional similarities due to their common evolutionary origin and their roles in the contact activation system [29, 30]. In KKS, FXII and plasma prekallikrein are reported to reciprocally activate one another to form their active forms: FXIIa and plasma kallikrein. In the original coagulation pathway, FXI is a major FXIIa substrate, and FXIIa catalyzes FXIa generation. Furthermore, both FXIa and plasma kallikrein are activated by FXIIa, also referred to as the Hageman factor. FXIIa triggers the intrinsic coagulation pathway and inflammatory responses through the kallikrein–kinin system [31]. The activation of FXII leads to the generation of FXIa and plasma kallikrein, which in turn promotes further activation of FXII, creating a positive feedback loop [29, 31]. For all the above-mentioned interactions and similarities, we targeted to test roflumilast for FXIIa specificity using other proteases from the coagulation system and KKS: FXIa and Kallikrein. Our findings reveal that roflumilast specifically binds to FXIIa and thereby inhibits its proteolytic activity.

The oral PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast binds to the FXIIa active site, as demonstrated by MD simulations of FXIIa-ligand complexes. MD simulations revealed that bonding with roflumilast results in more structural aberrations for FXIIa, indicating that roflumilast is not stable. The analytical theory behind MD simulation is validated by the fact that the results of the inhibition of activated factor XII assay and MD simulation were identical. To confirm roflumilast’s inhibitory potential against FXIIa, more in vivo experimental validations are needed. Neutrophils and platelets have been recognized as key elements in the onset and progression of thrombus formation. Both animal models and human illnesses have shown that neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) play a critical role in the pathophysiology of thrombosis. NETs were found to be released from active neutrophils in a process known as NETosis, which can be mediated by platelet and PMNL recruitment into the endothelial wall. Then, NETs could enhance platelet adhesion, activation, and aggregation, triggering thrombosis by activating coagulation cascades [32, 33]. Therefore, the risk of thrombosis in COPD and other inflammatory illnesses may be reduced by blocking neutrophils’ prothrombotic role and preventing roflumilast from producing NETs. Furthermore, it has been discovered that RNO, an active metabolite of roflumilast, affects NETs by inhibiting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (SFK–PI3K) pathway in polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs). Moreover, RNO may also inhibit the molecular pathways that regulate PMN–platelet adhesion [13].

FXIIa inhibitors target the intrinsic coagulation pathway, which may offer a unique approach to managing thrombotic risks associated with COPD. These inhibitors could potentially address the heightened coagulation state often observed in COPD patients without significantly increasing bleeding risks. By selectively targeting FXIIa, these inhibitors might provide anticoagulant effects while preserving essential hemostatic functions. This approach could be particularly beneficial for COPD patients who are at increased risk of both thrombotic events and bleeding complications [34]. Additionally, FXIIa’s role in inflammation suggests that its inhibition might offer dual benefits in COPD, potentially addressing both coagulation and inflammatory aspects of the disease [35]. Therefore, while FXIIa inhibitors are not directly mentioned in the context of COPD treatment, their potential anti-inflammatory properties could align with the current research direction in COPD therapeutics. However, further investigations and extensive clinical trials are necessary to determine their specific effects on COPD pathophysiology and to establish the efficacy, safety, and optimal dosing of FXIIa inhibitors in COPD patients before considering their integration into treatment protocols.

Roflumilast, a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, is primarily known for its anti-inflammatory properties in treating COPD. While its direct anticoagulant effects were not well-established before, the drug’s ability to reduce inflammation could indirectly benefit coagulation processes in COPD patients [36]. Chronic inflammation in COPD is associated with increased thrombotic risk. Bradykinin, a peptide involved in the kallikrein–kinin system, plays a notable role in the pathophysiology of COPD by promoting inflammation, bronchoconstriction, and increased vascular permeability. Elevated levels of bradykinin in the lungs can exacerbate airway inflammation and contribute to symptoms such as chronic cough and mucus hypersecretion. Additionally, bradykinin may sensitize airway sensory nerves, leading to heightened cough reflex sensitivity, a common feature in COPD patients. Given that Bradykinin is a known mediator of inflammation, it may contribute to the inflammatory cascade in COPD [37]. Furthermore, approximately half of the bradykinin present in plasma is dependent on the FXII pathway [38]. Accordingly, targeting FXIIa activity with roflumilast could help reduce inflammation-related symptoms and thrombotic risk associated with chronic inflammation in COPD. Interestingly, our findings show that roflumilast, the only approved PDE4 inhibitor for COPD, has demonstrated anticoagulant activity by inhibiting the enzymatic activities of coagulation FXIIa. Although roflumilast is not a potent FXIIa inhibitor, this finding suggests that in addition to its approved anti-inflammatory role in treating COPD, it might possess a mild anticoagulant property and reduce bradykinin levels released by the FXII-dependent pathway that could ultimately result in reducing the occurrence of exacerbations in patients with COPD.

In conclusion, targeting FXIIa could be a promising mechanism of anticoagulation without causing bleeding or affecting the normal hemostatic capacity. In this work, we utilized an in vitro amidolytic assay, in silico molecular docking, and simulation investigations to explore the possible inhibitory effect of roflumilast against the FXIIa enzyme. The findings of this study can be viewed considering certain limitations. The major limitations are the lack of ex vivo and in vivo anticoagulant efficacy studies. The results of these methods would strengthen our interesting results of the only approved PDE4 inhibitor for COPD, roflumilast, on FXIIa-driven pathways. Future work investigations using the above-mentioned techniques could help pave the way for discovering more mechanisms of the roflumilast-related beneficial effects in the management of COPD.

In the present study, we were able, for the first time, to present data showing a significant anticoagulant activity of the selective oral PDE4 inhibitor, roflumilast, via its in vitro inhibition of FXIIa activity. Therefore, we suggest that roflumilast might have beneficial effects in FXIIa-driven coagulation in thromboembolic disorders and inflammation. This study shows that roflumilast offers promising opportunities for therapeutic significance in health conditions associated with over-activation of the KKS and coagulation pathway. As the degree of activation of the KKS and coagulation increases during exacerbation of COPD. Future investigations are necessary to better understand the impact of FXIIa inhibition by roflumilast, including downregulation of bradykinin (BK) formation, the effects on fibrin formation, and the in vivo tail bleeding assays in animal models. These investigations will reveal other mechanisms by which roflumilast is effective in reducing exacerbation in patients with COPD.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

HAM designed the research study. HAM, MAA, and MNA performed the research. HAM, MAA, and MNA analyzed the data. HAM, MAA, and MNA wrote the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not Applicable.

Not Applicable.

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number (IF-PSAU-2021/03/18887).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.