1 Department of Cell Technologies, Institute of Future Biophysics, 141701 Dolgoprudny, Russia

2 School of Biological and Medical Physics, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, 141700 Dolgoprudny, Russia

3 Institute of Cell Biophysics of Russian Academy of Sciences, 142290 Pushchino, Russia

Abstract

The chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model is gaining increasing attention from cancer researchers worldwide. Its affordability, short experimental duration, robustness, and ease of tumor xenograft visualization make it a valuable tool in cancer research. This review explores recent advancements and potential applications of the avian CAM model, including the following: (1) studying tumor growth and metastasis, (2) investigating mechanisms of tumor chemoresistance, (3) optimizing drug delivery methods, (4) improving bioimaging techniques, (5) evaluating immuno-oncology drug efficacy, (6) examining tumor-extracellular matrix interactions, (7) analyzing tumor angiogenesis, and (8) exploring the roles of microRNAs in cancer. Additionally, we compare the in ovo CAM model with other in vivo animal models and in vitro cell culture systems. Positioned between in vitro and in vivo models in terms of cost-effectiveness and accuracy in cancer recapitulation, the CAM model enhances both preclinical and translational research. Its expanding use in cancer studies and therapy development is expected to continue growing.

Keywords

- chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM)

- in ovo

- cancer metastasis

- drug development

- radiotherapy

- chemotherapy

- miRNA

- tumor-microenvironment interactions

- immuno-oncology

- immune-vascular dynamics

The earliest experiments on chicken embryos date back to the 1750s when German scientist Beguelin observed successive developmental changes in the germinal disk by creating a window in the eggshell [1, 2]. By the 1890s, Mathias Marie Duval published the first comprehensive morphological atlas of chicken embryo development [1]. In the early 20th century, studies on chickens infected with the sarcoma virus led to the discovery of viral carcinogenesis [1], prompting researchers to investigate the feasibility of chicks as an animal model for human tumor studies. By the latter half of the 20th century, chicken embryos were increasingly used in cancer research [3, 4, 5]. More recently, the chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model has gained attention as a cost-effective in ovo model for studying various aspects of tumorigenesis and metastasis (Fig. 1).

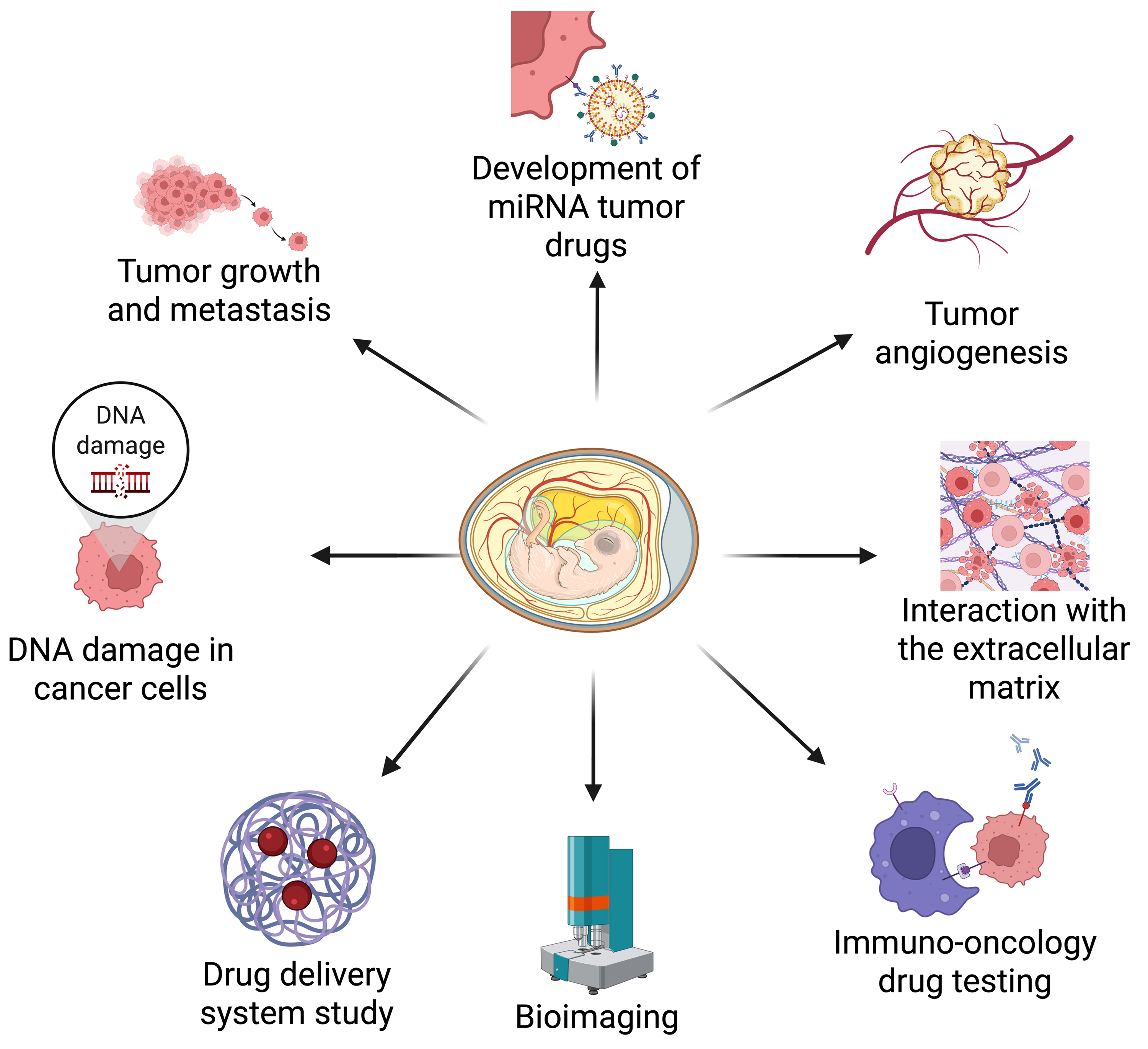

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) oncogenesis model is widely used to investigate various aspects of tumorigenesis, metastasis, and drug delivery. These applications include the following: (1) tumor growth and metastasis, (2) genomic DNA damage in cancer cells, (3) drug delivery optimization, (4) bioimaging advancements, (5) immune-oncology drug testing, (6) tumor-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions, (7) tumor angiogenesis, and (8) the role of microRNAs in cancer. Created with BioRender.com.

Table 1 (Ref. [1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]) presents a compelling timeline that juxtaposes historical advancements with recent breakthroughs in CAM research.

| Time period | Research advancement | Key findings/applications |

| 1750s | Early embryonic observation | German scientist Beguelin [1, 2] introduced a technique to cultivate chick embryos by opening a window in the eggshell, enabling sequential observation of developmental changes in the germinal disk. |

| 1890s | Morphological atlas publication | Mathias Marie Duval [1] published the first comprehensive morphological atlas of chick embryo development, enhancing the understanding of avian embryology. |

| First half of the 20th century | Discovery of Rous sarcoma virus | Peyton Rous [6] identified a transmissible agent causing sarcoma in chickens, establishing a foundational model for studying viral oncogenesis. |

| Tumor transplantation studies | James B. Murphy [7] demonstrated that foreign tissues could survive in the CAM, facilitating tumor transplantation research. | |

| Viral cultivation techniques | Alice Miles Woodruff and Ernest Goodpasture [8] developed a method using chicken eggs to propagate viruses, advancing virology research. | |

| Standardization of developmental stages | Viktor Hamburger and Howard Hamilton [9] developed the Hamburger-Hamilton stages, a standard framework for chick embryo development still in use today. | |

| Second half of the 20th century | Angiogenesis research | The CAM model was emerging as a promising platform for investigating tumor angiogenesis [10]. |

| Metastasis studies | Researchers used the CAM model to study how tumors metastasize, providing important insights into cancer progression [11]. | |

| 21st century | Drug testing and nanotechnology | The CAM model serves as a valuable platform for evaluating anticancer drugs and nanomaterials because of its vascular characteristics and ease of observation [12, 13, 14, 15]. |

| Immuno-oncology applications | Researchers employed the CAM model to assess immune responses and the efficacy of immunotherapeutic agents against tumors [16, 17, 18]. | |

| Precision medicine and patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) | The CAM model has been refined to facilitate swift testing of individual tumor responses, significantly enhancing personalized cancer treatment strategies [19, 20]. |

The development of anticancer drugs is a complex process that involves preclinical trials requiring a large number of mice for pharmacological analysis [21]. Ethical considerations play a crucial role in these experiments, which must adhere to the 3R principles (Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement) [22]. The CAM model aligns with these principles, offering an ethically favorable alternative to traditional mammalian models. In many countries, chicken embryos are not classified as live animals before embryonic day 17 (E17), allowing CAM experiments conducted before this stage to be exempt from ethical oversight, such as Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) review. This exemption streamlines procedures while minimizing animal suffering [23, 24]. For experiments extending beyond E17 or involving invasive procedures, the use of anesthetics (e.g., isoflurane) and adherence to humane endpoints—such as limiting tumor burden or preventing excessive bleeding—are essential to meet refinement standards [25]. Regulatory acceptance of the CAM model varies globally. The European Union Directive 2010/63/EU provides specific protections for embryonic models, while in the United States, experiments conducted before hatching may not be subject to animal welfare regulations [26, 27]. These regulatory considerations enhance the model’s credibility and support its broader adoption within the scientific community.

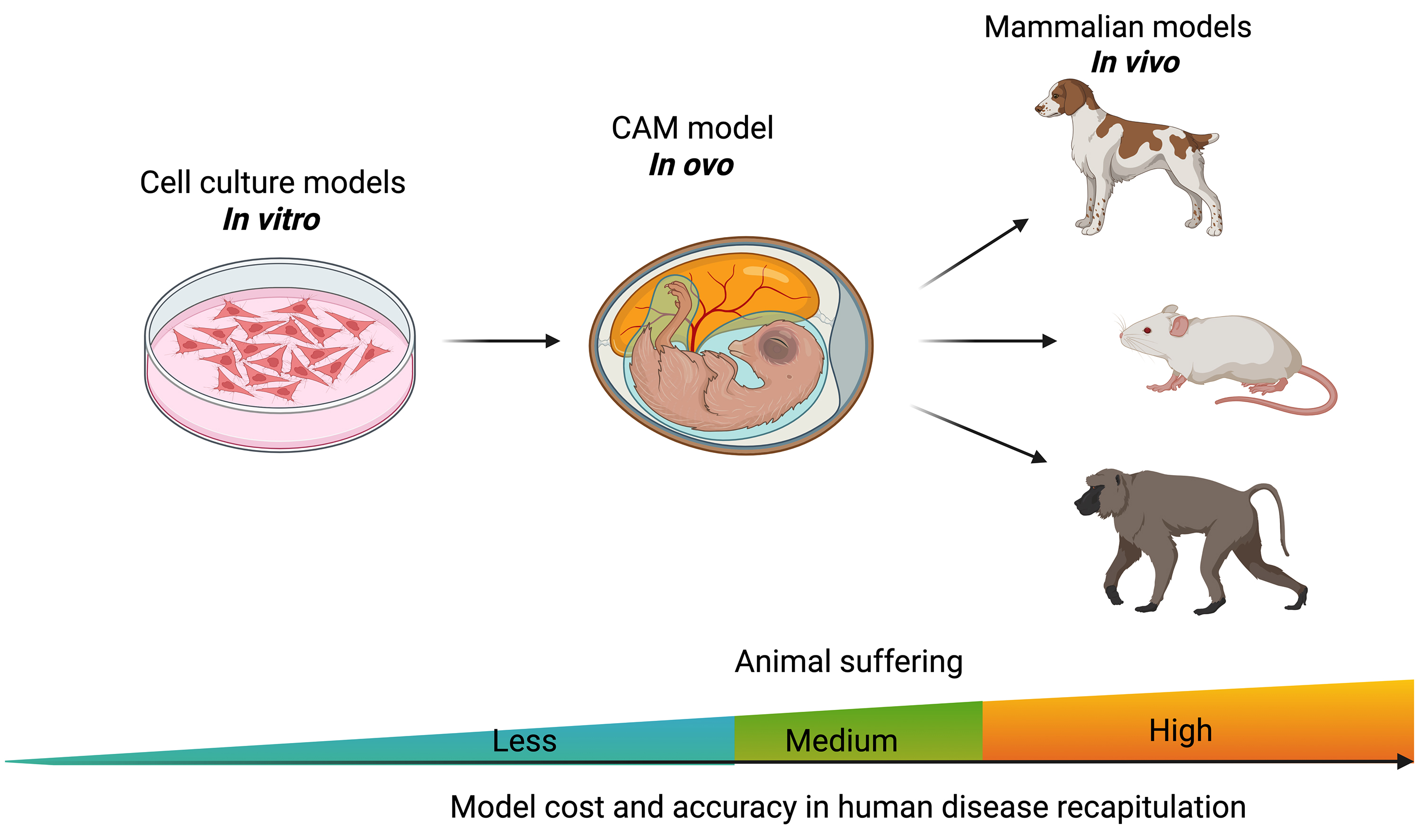

The CAM model serves as an intermediate system between in vitro and in vivo models, offering distinct advantages over both (Fig. 2). Compared to in vitro models, the CAM provides a physiologically relevant microenvironment, including vascularization and dynamic tissue interactions, enhancing its translational potential [23]. While mouse and rat models remain the gold standard in cancer research due to their ability to replicate complex tumor-host interactions, growing evidence supports the CAM model as a viable alternative or complement to traditional animal systems [28]. Recent study demonstrates that enhanced permeability and retention (EPR)-dependent macromolecules exhibit intra-tumoral accumulation and retention kinetics in CAM xenografts that closely resemble those in mouse models [29]. Additionally, Pinto et al. [30] successfully adapted the limiting dilution assay (LDA) from mouse models to develop the CAM-LDA system, validating its robustness for assessing breast cancer stem cell tumorigenicity. Rousset et al. [31] further demonstrated that CAM models could effectively replace mouse-derived circulating tumor cells, advancing applications in personalized medicine. This unique balance makes the CAM model an ethically favorable and scientifically robust platform for preclinical cancer research.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The chicken embryo CAM model is placed between in vitro cell culture and in vivo animal models. Created with BioRender.com.

This review decisively highlights the emerging utility of the CAM model in anti-tumor microRNA (miRNA) research, tumor-matrix interactions, and immuno-oncology drug screening, distinguishing it from previous reviews that provided a more generalized perspective of the model’s applications. Traditional models have notable limitations: in vitro assays lack physiological complexity, while conventional animal models often present challenges in efficiency and cost. The CAM model addresses these issues with its intrinsic vascular network, enabling rapid, cost-effective, and physiologically relevant assessments of miRNA-mediated regulation, tumor-stroma interactions, and immune-vascular dynamics. Furthermore, we discuss recent technological advancements that enhance the model’s translational relevance and precision, solidifying its role as a critical bridge between simplified in vitro systems and traditional in vivo models.

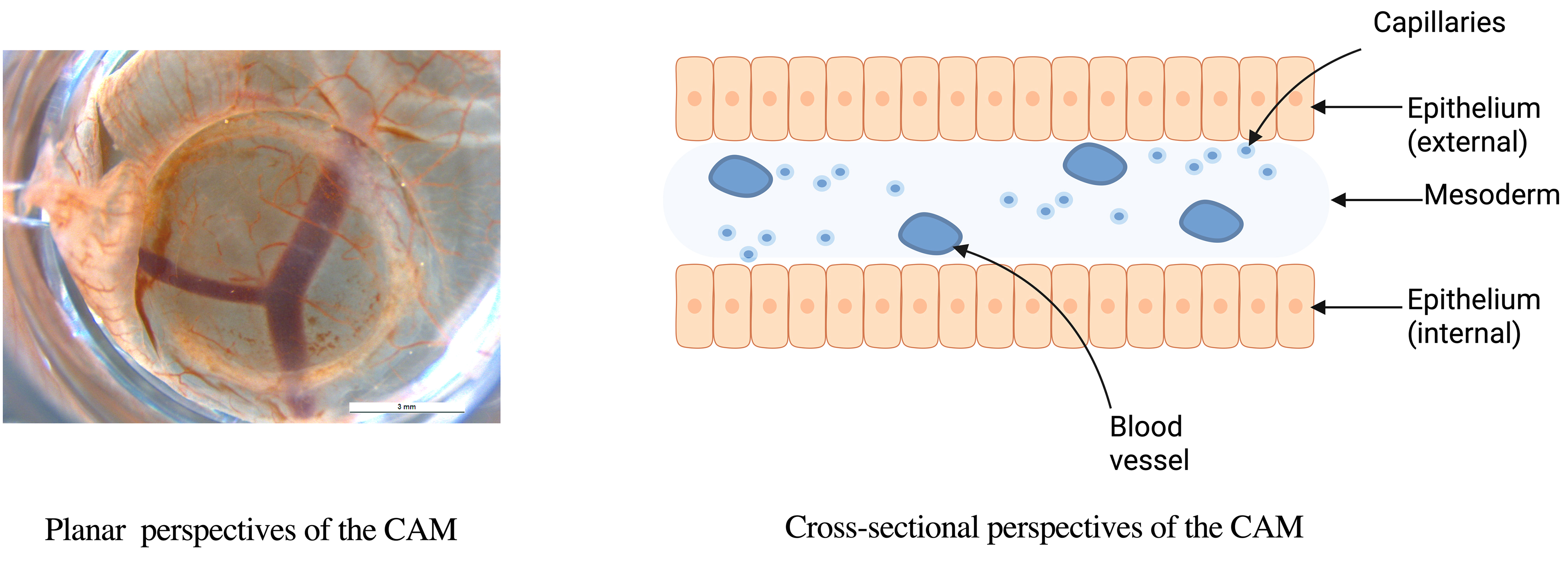

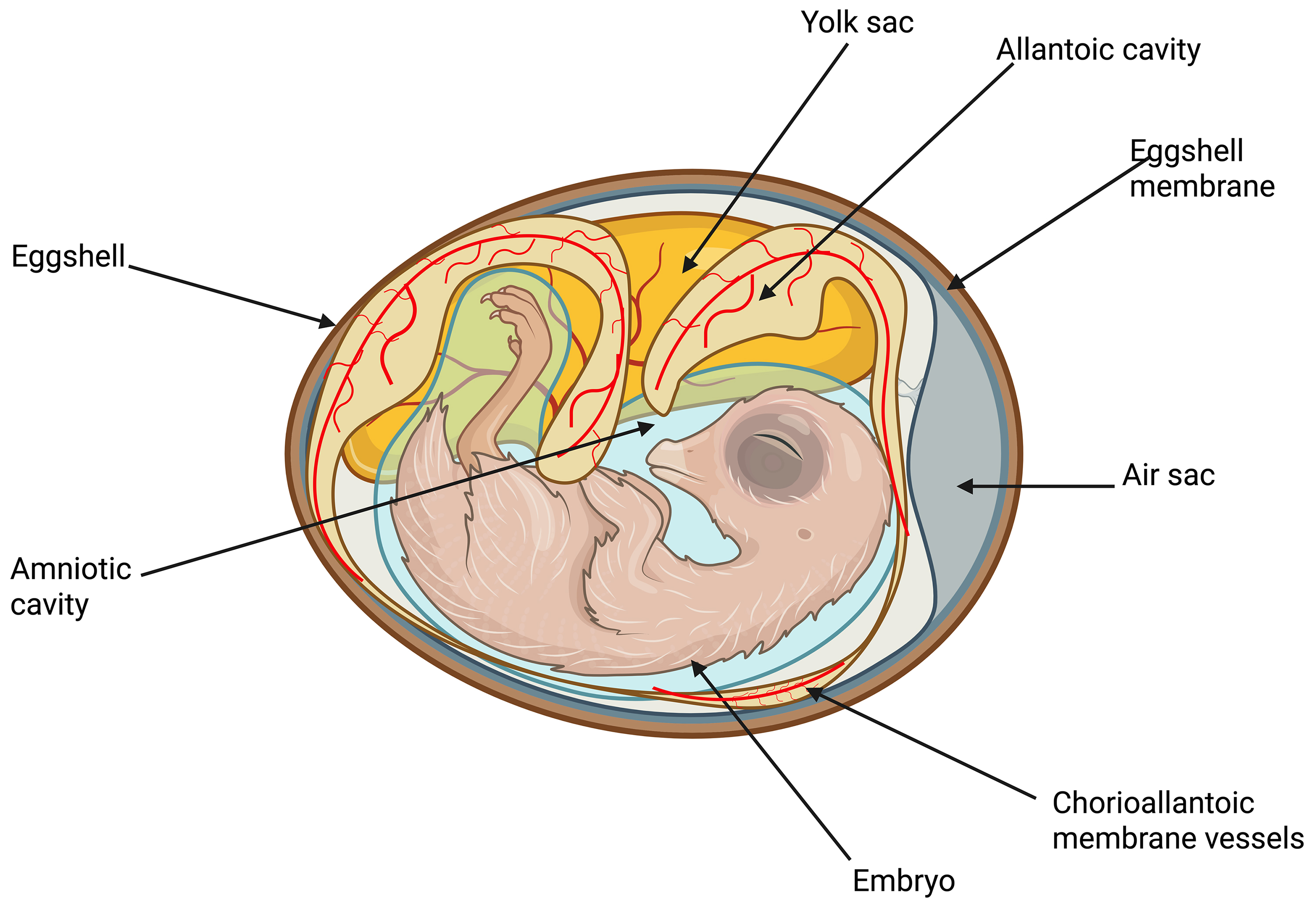

Histologically, the CAM consists of three layers: an external epithelial layer of ectodermal origin, an intermediate stromal layer, and an internal epithelial layer of endodermal origin (Fig. 3) [32]. CAM development occurs between embryonic day 5 (E5) and E21. From E5 to E12, the chorion and allantois fuse, and the CAM expands to cover the entire egg surface. Between E13 and E18, the CAM undergoes rapid growth, differentiation, and expansion, with chorionic capillaries occupying the superficial layer and the number of allantoic layers increasing to four. Proliferation and differentiation peak at E18, followed by gradual degradation from E18 to E21 [33]. CAM angiogenesis occurs in three stages [34], with structural maturation during the third stage (E13–E14) [35]. Since rapidly proliferating tumors favor intussusceptive angiogenesis for nutrient acquisition [34], the optimal time for tumor transplantation is after E8, when this process begins.

On days E4–E5, the CAM attaches to the surface of the eggshell removing calcium and thus accessing oxygen through the porous eggshell [32]. The general structure of the chicken embryo is shown in (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Schematic diagram of the intra-egg of the pre-developing chicken embryo. Created with BioRender.com.

The lymphatics of the CAM develop at E6–E9 and grow by blind-ended sprouting [36]. The CAM lymphatic vascular endothelial cells express vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 and 3 (VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3) molecules, which resemble the mammalian lymphatic system [32, 37]. Studies [38, 39] have demonstrated a strong link between lymphatic vessels and cancer metastasis. The structural and functional similarities between the avian CAM and mammalian lymphatics further support the CAM’s suitability as an in vivo oncogenesis model [40].

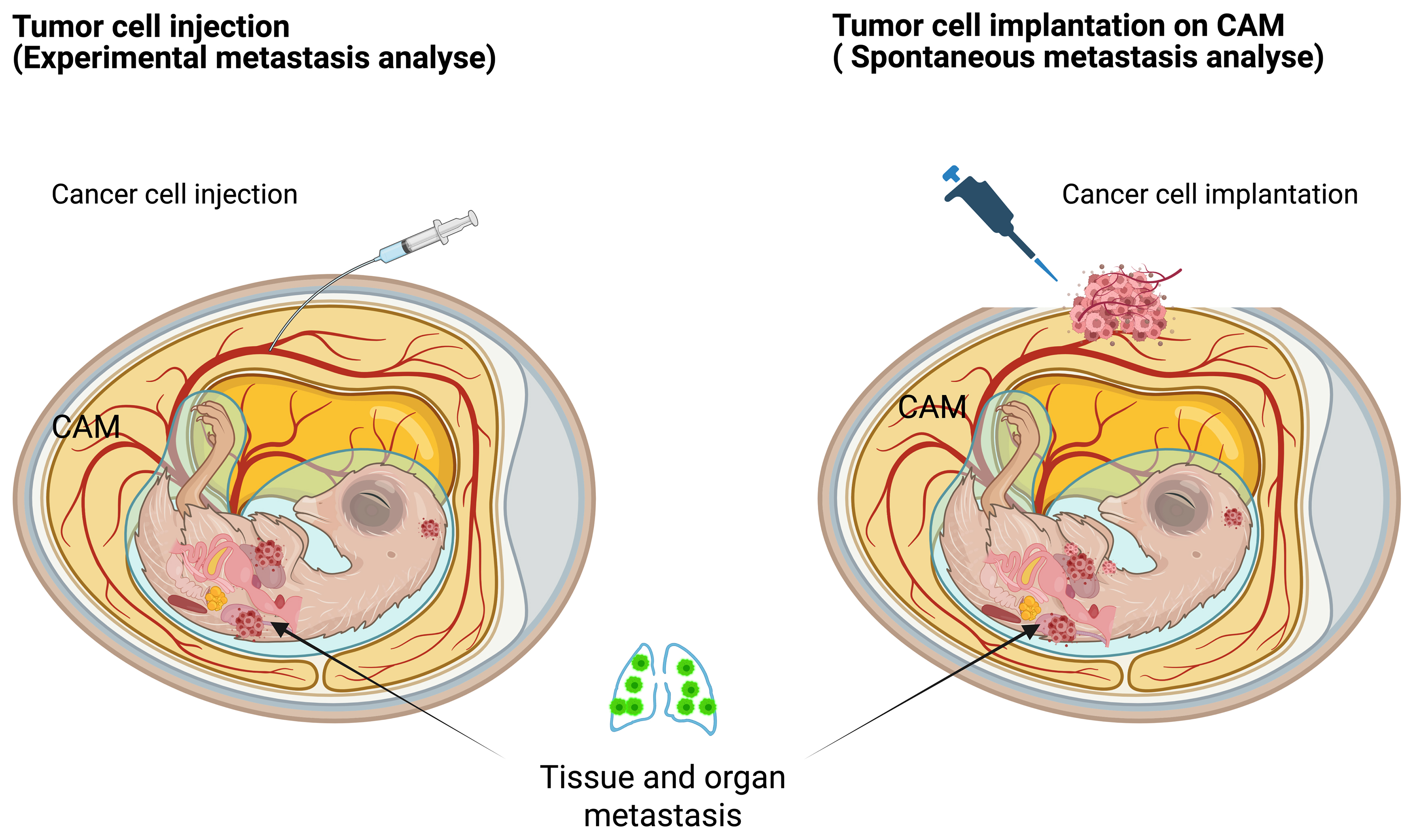

The progression of cancer-related health deterioration often begins with metastasis. The complexity of this process, which involves multiple tissues and organs and occurs deep within the body, makes continuous observation challenging in traditional animal models. The in ovo model provides a robust experimental system that mimics all stages of the metastatic cascade, facilitated by the continuous circulatory connection between the extraembryonic membranes and the avian embryo, allowing for easy manipulation. While existing 3D in vitro models fail to accurately replicate the intricate structure of blood vessels—particularly capillaries and post-capillary venules, which are key sites of cancer invasion—rodent models also present limitations due to the rarity of metastasizing tumors. The CAM’s rich vascularization offers an optimal platform for studying both experimental and spontaneous metastasis (Fig. 5), enabling comprehensive investigations of the metastatic process [41]. Notably, the chicken CAM model has been applied to study cancer cell motility and invasion in vivo, in multiple studies [42, 43, 44, 45, 46].

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Tumor metastasis models in chicken embryos. Left—the experimental metastasis model; Right—the spontaneous metastasis model. Created with BioRender.com.

Cancer cell invasion, extravasation, and metastatic colonization have been investigated in ovo using a combination of detailed morphological assessments, selective outgrowth of metastasized cells in controlled environments, and advanced imaging techniques for detecting microscopic tumor nodules [14]. Additionally, several biomarkers, including human urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) activity [1, 43] and those linked to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [47], have been analyzed in the in ovo model using methods such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), tissue staining, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A significant limitation of conventional mouse models for studying experimental metastasis is that most injected tumor cells die in the microcirculation before they can successfully extravasate. In the innovative chicken CAM metastasis model, extensive research has demonstrated that an impressive 80% of tumor cells, when injected into the allantoic vein, successfully survive the initial phase and manage to extravasate within a timeframe of just 1 to 3 days [48]. The ability of these cells to not only survive but also navigate toward these vessels is a crucial aspect of understanding cancer metastasis. This model serves as a vital tool in cancer research, providing insights into the dynamics of tumor behavior in relation to vascular structures.

A recently reported intravital microscopy platform enables high-resolution time-lapse imaging of human tumor growth, cell migration, and extravasation in ovo, allowing for longitudinal monitoring and quantitative analysis of tumor cell metastatic capacity following CAM implantation [14, 49]. In this approach, chicken blood vessel cells were labeled with fluorescent Lens culinaris agglutinin, and blood flow was visualized using a fluorescent dye. Fluorescently labeled cancer cells were then injected into the vitelline vein to track tumor cell movement and examine the role of invadopodia in metastasis over a 24-hour period [49]. Additionally, the study has investigated spontaneous metastasis following tumor cell grafting onto the CAM by injecting labeled cells that can be traced in organs, blood, and the amnion in both in ovo and ex ovo models [50, 51].

Detecting metastatic colonization in different organs is challenging due to the low number of tumor cells and the limited timeframe of experimental studies, which often prevents the formation of macroscopic nodules. However, the human genome’s unique enrichment in Alu sequences, occurring at a frequency of 5%, enables the sensitive detection and quantification of metastasized human tumor cells using Alu PCR assays [52, 53]. These powerful assays can identify and quantify as few as 50 cells [54].

Last, but not least, a standardized method for evaluating the ability of human cancer cells to degrade the basement membrane—specifically their delamination capacity—is crucial for assessing metastatic aggressiveness. The so-called “CAM-Delam” assay has demonstrated, through a variety of human cancer cell lines, that the capacity for delamination can be classified into four distinct categories [55]. This classification not only quantifies metastatic aggressiveness but also highlights the assay’s vital role in measuring delamination potential. Moreover, it aids in uncovering the molecular mechanisms that govern delamination, invasion, micro-metastasis formation, and the modulation of the tumor microenvironment. This approach has the potential to greatly enhance both the preclinical and clinical analysis of tumor biopsies, as well as facilitate the validation of compounds that could boost survival rates in metastatic cancer [55].

Deregulated angiogenesis, now recognized as a fundamental hallmark of cancer, plays a critical role in tumor progression by enabling malignancies to develop their own blood supply [56]. The highly vascularized CAM, which functions as the gas exchange organ in birds, is an ideal model for angiogenesis research. Traditionally, pharmacological evaluations of pro- and anti-angiogenic compounds have been conducted in ovo, with growing interest in applying this approach to preclinical oncology. Following tumor inoculation, the tumor xenografts begin to manifest and become clearly visible within just 2 to 3 days. During this time, they establish a robust vascular network, primarily derived from the chick CAM, which rapidly penetrates deep into the tumor tissue. This efficient blood supply not only supports the tumor’s growth but also facilitates the delivery of essential nutrients and oxygen. As a result, the developing tumor can quickly adapt and proliferate, leading to observable increases in size and mass [15].

This model can be applied to the evaluation of any factor influencing angiogenesis as well as to probing connections between angiogenesis and other processes or conditions such as cancer. Vascular growth inhibition as a mechanism of cooper chelators’ anticancer effects was also demonstrated in the chicken CAM model [57]. In the other study [58], different cancer cell grafts in the CAM were subjected to functional gas challenge, which is the exposure of cancer cell grafts to various combinations of atmosphere gases. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was used to evaluate functional gas challenge effects on cancer cell grafts. Different responses were observed for different cancer cells depending on the formed graft size and its vascular density [58].

The growing number of angiogenesis studies on the CAM model has provoked the development and refinement of corresponding methods. Numerous qualitative and quantitative methodologies have been extensively documented to assess in ovo angiogenic response. The CAM assay was optimized for quantitative measurement of changes in vessel density, endothelial proliferation, and protein expression after the application of anti-angiogenic agents [59]. Recently, an artificial intelligence method of the CAM cancer model angiogenesis quantification was developed. This method aims to provide technical support for therapeutic options targeting cancer angiogenesis [60].

Recent breakthroughs in imaging technologies, alongside enhancements in contrast and imaging agents, now enable the precise visualization of vascular perfusion and the selective labeling of vascular structures at microscopic scales. Histological and immunohistochemical analyses serve as the benchmark for reference standards. These analyses routinely utilize hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, along with staining for vascular and endothelial markers, including CD31 and von Willebrand factor (vWF) [61, 62]. Chicken endothelium can be specifically stained by Sambuco negro agglutinin (SNA) [63]. Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) combined with polymer injection has proven effective for assessing three-dimensional vascular remodeling in ovo [64].

Vascular dynamics have been monitored longitudinally using digital photos captured in controlled lighting and examined with image analysis software [65]. Intravital vascular architecture and fluid dynamics can be monitored by viral nanoparticles carrying reporter genes [66]. As a label-free alternative, the Doppler mode measurements of vascular structure can be used to expand pre-described ultrasonography used for the assessment of tumor growth suppression by anti-Chloride Intracellular Channel Protein 1 (CLIC1) [67]. However, because of tissue clutter, this method is mostly restricted to monitoring big vessels. The small size of tumors and the radiopaque eggshell, which restricts monitoring to a top-down perspective, present challenges for conventional imaging methods. High-frequency ultrasensitive ultrasound microvessel (UMI) imaging has enabled a more detailed characterization of slow-flow vessels within the microvasculature, as demonstrated in a renal cell carcinoma model following the administration of two Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved anti-angiogenic drugs [21]. Ultrasonography is cost-effective and widely accessible, making it a valuable tool for in ovo tumor imaging. Combined with the affordability and simplicity of CAM assays, this approach allows for high-throughput, quantitative imaging while facilitating longitudinal monitoring of tumor progression. Consequently, the CAM assay serves as a viable alternative to mouse xenograft models, improving reproducibility in in vivo tumor testing. One significant drawback is that data interpretation may be impacted by the inability to differentiate tumor-related neoangiogenesis from innate embryonic neovascularization or increased vascular density brought on by the rearrangement of preexisting arteries [68]. Angiogenic investigations must be timed carefully to prevent confounding variables. Hence, angiogenic investigations in the CAM model are commonly conducted between E10/11 and E14/15 since the endothelium mitotic index and the overall complexity of the CAM diminish around E11 [48, 69].

Overall, the CAM model’s suitability for cancer angiogenesis research supports its rapid development and broad application in the field.

The CAM model, with its collagen I-rich ECM, provides an excellent platform for mimicking the in vivo conditions of aggressive tumors [70]. One of the key characteristics of many aggressive cancer types, such as breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and osteosarcoma, is their dense collagen I-rich extracellular matrix [71, 72, 73, 74]. This matrix not only supports the structural integrity of the tumor but also plays an active role in promoting cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. By using the CAM model, researchers can replicate this specific ECM environment and observe how cancer cells interact with the collagen-rich matrix, offering a highly relevant in vivo-like setting for tumor studies. In aggressive cancers, collagen crosslinking and increased ECM stiffness are critical factors that enhance cellular adhesion, elevate invasive potential, and activate mechano-transduction pathways, all of which contribute to tumor growth and metastasis [75]. The CAM is highly vascularized and readily promotes angiogenesis when tumor cells are grafted onto its surface, creating a realistic model for studying how cancer cells influence and are influenced by the surrounding vascular network. This process is closely tied to the ECM, as ECM components, such as collagen, interact with angiogenic factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to promote new vessel formation [76]. The CAM’s ability to mirror both the ECM and the angiogenic environment allows a comprehensive analysis of tumor-ECM-vasculature interactions.

Currently, the most commonly used animal models for preclinical immuno-oncology research can be broadly categorized into two types: (1) xenograft models, where human cancer cell lines are transplanted into immunodeficient mice; and (2) syngeneic models, where mouse-derived cancer cell lines are transplanted into immunocompetent mice. Humanized mice are one of the more suitable models for pre-clinical immunotherapy studies. While these models have advanced immuno-oncology research to some extent, they exhibit significant limitations [77].

In this context, the CAM model emerges as an ideal choice. During the early stages of embryonic development (E0–E12), the immune-deficient state of the embryo enables stable xenograft transplantation of human tumor cell lines, resulting in reliable tumor formation. As the immune system matures in the mid-to-late stages of embryonic development (E12–E18), the CAM model becomes a valuable platform for studying the efficacy of various immunotherapeutic agents. Building on the various humanization models used in mice, two recent extensive studies [78, 79] propose the dual engraftment of human immune and tumor cells in fertilized chicken embryos. This approach offers a xenogeneic system to explore immunotherapies in a more thorough yet cost-effective semi-in vivo model. The brief experimental duration presents a significant limitation, as it constrains our capacity to perform long-term evaluations of cancer immunity in ovo. Consequently, the dual role of the immune system in the context of immunoediting remains unexplored. Although avian and mammalian lymphoid organs are different, there are some functional similarities between chicken and mammalian immune systems. Thus, CAM model experiments can be used as a transition between cell culture and complex mammalian model experiments [51]. Different functional immune cells such as T cells, B cells, and Natural Killer (NK) cells can be detected at later stages of avian embryonic development [48, 80, 81]. Importantly, immune checkpoints similar to that in human immuno-oncology therapy, including Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 (PD-1), Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1), Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte–Associated Protein 4 (CTLA-4), and Lymphocyte-Activation Gene 3 (LAG-3), were identified in chickens [80], suggesting the suitability of the CAM model for immune-oncology studies. Applicability of the CAM model for immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) studies was directly demonstrated in a recent study, where the efficacy of the FDA-approved ICI drug Pembrolizumab was successfully verified on the CAM model [16]. These studies point to the great potential of the chicken embryonic tumor model for promising immune-oncology studies including cancer immune drug testing.

Non-invasive assessment of tumor biodistribution is very useful for cancer studies and the development of new anti-cancer drugs. Several recent studies have revealed the feasibility of intra-oval imaging in the CAM model [82, 83]. Some research groups have optimized MRI compounds for intra-oval imaging, and they suggest that using isoflurane to chill the embryo can reduce artifacts and improve resolution [84, 85, 86]. Other studies have reported the use of chicken embryos in positron emission tomography imaging [87, 88, 89, 90, 91]. In a study of a CAM tumor model for colorectal cancer, researchers evaluated a new radiotracer, Ga-Pentixafor, for preclinical trials by performing simultaneous positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance (µPET/MR) scans [92]. Recently, the PET imaging capabilities of radiolabeled peptides, specifically the 68Ga-labeled human epithelial growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) affibody, 68Ga-MZHER, have been effectively validated for tracking tumor-targeting potential and pharmacokinetic profiles in chicken CAM tumor models of human breast cancer [93]. Furthermore, 18F-labelled prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) ligand, [18F]F-siPSMA-14, PET/MRI was successfully used to image PSMA-positive and negative tumors both in ovo (CAM model) and in vivo [94].

Nevertheless, significant challenges persist in this field, such as the variability in tumor growth rates, the complexities of cannulating the CAM vessels for dynamic imaging, and the necessity to cool the egg to immobilize the embryo. This cooling process adversely affects the delivery, internalization, and metabolism of radiotracers. Recently, a simple method for vessel cannulation and the use of liquid narcotics for chick immobilization enabled direct comparison studies showing that the chick CAM may reduce the reliance on subcutaneous tumor-bearing mice. The non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tumor uptake patterns of 18F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (18F-FDG) were similar in both in ovo and in vivo studies. However, the radioactivity levels associated with tumors cultivated on the CAM were notably higher throughout the 60-minute imaging duration. Additionally, (4S)-4-(3-18F-fluoropropyl)-L-glutamate (18F-FSPG) proved to be an early biomarker for assessing treatment response to external beam radiotherapy and targeted inhibition in ovo [95]. Therefore, CAM models could serve as an excellent platform for assessing the effectiveness of pharmacological compounds, particularly radiopharmaceuticals [96]. Further development of bioimaging techniques can be anticipated for the CAM model, given the increasing interest in this model from researchers.

A key focus in the study of tumor chemoresistance is the creation of cost-effective and user-friendly realistic three-dimensional (3D) in vitro and in vivo models tailored to individual patient tumors [97]. The CAM (in ovo) model presents a compelling alternative to traditional in vivo models for tumor engraftment. It presents a compelling alternative to conventional 3D spheroids [98], organoids [99], and costly patient-derived xenograft (PDX) or the cell line-derived xenograft (CDX) mouse models [100]. In ovo experiments can be executed within a concise timeframe of just 18 days. Additionally, this low-cost approach allows for straightforward retrieval of the tumors formed, enhancing the feasibility of research endeavors [46].

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are fundamental to the processes of cancer initiation, progression, and the unfortunate relapse of the disease following treatment. These unique cells possess the ability to self-renew and differentiate, contributing to the heterogeneity found within tumors. Their resilience and adaptability often complicate treatment efforts, making them a significant focus in cancer research and therapy development. The molecular mechanisms underlying the radio- and chemo-resistance of CSCs are largely due to their improved ability to repair DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) [101, 102]. Understanding the mechanisms by which CSCs operate is crucial for improving cancer treatment outcomes and preventing recurrences.

The CAM model was evaluated alongside the immunodeficient mice model to assess the tumorigenic potential of CSCs derived from patients. The CAM model has proven to be a suitable alternative for this assay, standing alongside the immunodeficient mice model, which is regarded as the gold standard in cancer stem cell research. In fact, xenograft tumors developed significantly faster and exhibited enhanced stability and reproducibility in naturally immunodeficient chicken embryos compared to engineered immunocompromised mice [30]. Two recent studies have consistently demonstrated the successful application of the CAM model to assess the tumorigenic potential of circulating cancer cells in patients with breast, prostate, and lung cancers [31, 103]. The dependable and consistent development of PDX tumors highlights the CAM model’s effectiveness for drug evaluation studies. In fact, the CAM model, utilizing ovarian cancer PDXs, has proven successful in assessing the efficacy, toxicity, biodistribution, and delivery of doxorubicin-loaded nanovesicles [13]. Consequently, the CAM model is equally effective as the immunodeficient mice model for PDX studies, particularly in evaluating chemoresistance.

The CAM model has proven effective in evaluating the aggressiveness and tumorigenic potential of chemoresistant retinoblastoma (RB) cell lines. Etoposide-resistant RB cells demonstrate more aggressive behavior in the CAM model compared to their original tumor counterparts, potentially increasing the risk of local relapse. In contrast, cisplatin-resistant RB cells exhibit a markedly reduced tumorigenic potential [104].

Chemotherapy stands as a primary strategy in cancer treatment. Nevertheless, the majority of chemotherapeutic agents lack specificity and necessitate high dosages to attain the desired therapeutic effect. As a result, this not only escalates treatment costs but also aggravates adverse side effects [105, 106]. Cancer-targeting drug delivery systems are developed to overcome these limitations. Animal research is essential for the development of effective drug-delivery systems.

The United States FDA has granted official approval for the CAM model, recognizing it as a highly effective alternative to conventional animal models for the evaluation of oncology drugs [107]. This model assesses drug activity, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics, while also evaluating toxicity and side effects at various developmental stages of the late embryo [12, 108]. This sheds light on the growing popularity of the model among scientists.

Nanocarriers for drug delivery are defined as particles with diameters ranging from 1 to 1000 nm, encompassing various forms such as nanoparticles, nanoemulsions, carbon-based nanomaterials, and nanofiber composites [109, 110]. The CAM model was applied to assess drug delivery with nanocarriers in multiple studies. Efficacy, toxicity, biodistribution, and delivery of doxorubicin-loaded nanovesicles were successfully evaluated in the CAM model with ovarian cancer PDX [13]. Numerous studies have employed the CAM model to investigate the anti-angiogenic effects of various nanomaterials, frequently incorporating active ingredients within these materials. Anti-angiogenetic effects of imiquimod-loaded nanoparticles [111], nanoemulsions with resveratrol [112], graphite, multi-walled carbon nanotubes, fullerenes [113], and paclitaxel-loaded poly(d,l-lactide)/polyethylene glycol (PLA/PEG) micro/nanofibers [114] were reported after testing on the CAM model. A recent study investigated the tumor uptake of modified viral nanoparticles using high-resolution in vivo imaging techniques within the CAM model featuring human tumor xenografts. This study made significant advancements by enhancing the CAM model, enabling continuous, high-resolution visualization of nanoparticle distribution within the tumor and its surrounding blood vessels [115].

Recent advancements include studies on hybrid nanostructures that combine chemotherapy with photothermal therapy. For example, polydopamine nanoparticles have been shown to synergize chemotherapy and photothermal therapy for liver cancer treatment, demonstrating efficacy in both CAM and in vitro models [116]. Similarly, hybrid nano-architectures loaded with metal complexes have been explored for the co-chemotherapy of head and neck carcinomas, emphasizing the versatility of CAM assays for evaluating complex nanomaterial-based therapies [117]. Furthermore, CAM modeling has been employed to explore platinum-based drugs and their impact on tumor metabolism, revealing insights into their antitumor and antimetastatic activity as well as their influence on amino acid metabolism [118].

Alongside nanocarriers, hydrogels play a crucial role in the delivery of anti-cancer medications. The antitumor and anti-angiogenic effects of bevacizumab-loaded alginate hydrogel were effectively demonstrated using the CAM model featuring tumor grafts [119].

In summary, the CAM model serves as an exceptional tool for studying chemotherapy delivery, a fact corroborated by numerous publications from various independent research teams.

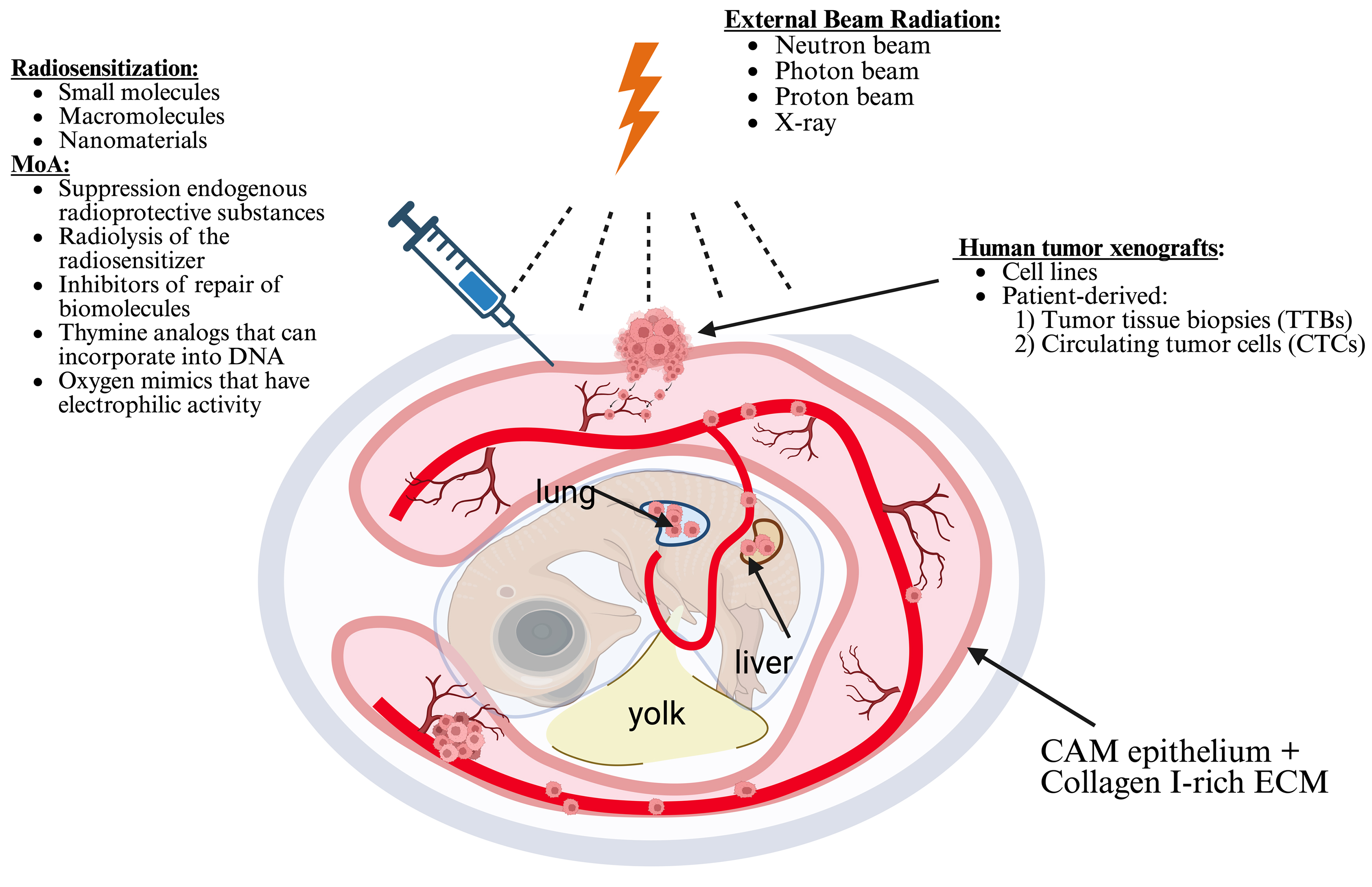

The CAM model is an exceptional animal model that creates an optimal external environment for tumor growth. As a result, it provides a valuable platform for assessing tumor responses to ionizing radiation and variations in tumor vascularity (Fig. 6, Ref. [68]) [120]. Conversely, the tumor CAM model presents a cost-effective and more practical alternative for radiation oncology research when compared to the pricier mouse models. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the IACUC have determined that chick embryos do not possess the capacity to perceive pain before the 14th day of gestation [121, 122], which allows their use without ethical concerns. These benefits render CAM models a highly appealing choice in cancer research, particularly for evaluating the efficacy of cancer radio- and chemotherapy, conducting drug screenings, and deepening our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying tumor growth and metastasis.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Schematic diagram of radiotherapy and chemoradiotherapy in a tumor chicken embryonic model. Drawn based on [68]. Created with BioRender.com.

The efficacy of radiosensitizers in cancer cells can also be investigated using the CAM model. For instance, the effectiveness of etanidazole has been successfully assessed on the EMT6 mouse breast cancer cell line and the Colon26 mouse colorectal cancer cell line utilizing chicken embryos [123]. The combination of etanidazole and 8 Gy X-ray irradiation results in a significant 35% reduction in the growth of solid tumors in the CAM model, highlighting the radiosensitizing effects of etanidazole [124]. It has also been shown that implanting C6 glioma cells into a CAM model subjected to X-ray radiation leads to a significantly higher rate of neoangiogenesis in tumors compared to unirradiated controls. This observation appears to be closely linked to the tumors’ resilience against radiation therapy [125].

A recent study reveals that various radiation modes inflict varying levels of damage on CAM capillaries. Specifically, a radiation dose of 20 Gy leads to the collapse of the capillary network when the CAM is subjected to a continuous radiation pattern. In contrast, the alterations caused by the microbeam radiation mode, even at a higher dose of 200 Gy, remain reversible. This finding underscores the promising potential of microbeam radiation as an innovative treatment approach for antitumor angiogenesis [126]. The research conducted by Kardamakis and colleagues [125] reveals that combining paclitaxel with ionizing radiation significantly inhibits neoangiogenesis in the CAM model. This finding opens up exciting new avenues for enhancing tumor radiotherapy.

Recent research suggests that the CAM model serves as an effective tool for the preclinical evaluation of chemo-radiotherapy using small molecule signal transduction inhibitors. The combination of radiotherapy with sunitinib, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor that targets multiple angiogenesis-related receptors, faces clinical challenges due to infrequent but severe side effects and inconsistent clinical benefits. To enhance the therapeutic potential of this combination treatment approach, various scheduling regimens and dose modifications for both sunitinib and radiotherapy were explored within the CAM model. Sunitinib, which was administered over four days at a dosage of 32.5 mg/kg per day, significantly enhanced the inhibitory impact of ionizing radiation (4 Gy) on angiogenesis while also effectively suppressing tumor growth. When radiation therapy was administered prior to sunitinib, it nearly eradicated tumor growth. In contrast, administering radiation therapy concurrently was less effective, and applying it after sunitinib yielded no further impact on tumor progression. Additionally, with optimal scheduling, it was possible to reduce the sunitinib dosage by 50% while still achieving similar antitumor effects. The CAM model conclusively shows that optimal treatment regimens allow for reduced doses of angiogenesis inhibitors, potentially minimizing the side effects associated with combination therapy in clinical practice [64].

The chick embryo presents a promising alternative model for assessing acute drug toxicity, offering an efficient preliminary screening option before conducting comprehensive toxicological studies in rodents during the development of anticancer drugs [12]. The in ovo carcinogenicity assay (IOCA) has emerged as an efficient and cost-effective non-animal approach for testing carcinogenicity and conducting experimental investigations into the mechanisms of carcinogenesis [127]. Chemically induced alterations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) could serve as a significant marker for assessing the carcinogenic potential of various substances, as the mitochondrial genome tends to exhibit greater sensitivity to DNA-damaging effects than nuclear DNA. CAM treatment with diethylnitrosamine caused a dose-dependent transition in mtDNA conformation, shifting from a supercoiled to a relaxed state. This change suggests a potential induction of single-strand breaks [128, 129]. Understanding the mechanisms behind mitochondrial impairment could provide valuable insights into potential therapeutic targets for age-associated conditions and cancers.

Briest et al. [128] effectively demonstrated the therapeutic potential of DNA damage modifiers used alongside radiation therapy for well-differentiated gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in a CAM model. Che and colleagues [129] developed a groundbreaking biodegradable ultra-small nanostructure (NAs-cisPt) encapsulated in a silica shell, which contains a cisplatin prodrug, serving as a sensitizer for radiotherapy in a CAM model. Their findings revealed that the integration of NAs-cisPt with radiotherapy significantly amplified DNA damage and promoted apoptosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cell lines, ultimately leading to a reduction in tumor growth rate [130]. Daniluk et al. [131] demonstrated that employing graphene as a carrier for melittin (M), a potent and toxic component of bee venom, significantly improved the targeting of cancer cells in a CAM model of breast cancer cell lines. This approach not only amplifies DNA damage in cancer cells but also elevates the levels of proteins linked to the suppression of tumor progression [132].

Polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated platinum nanoparticles (PtNPs) emerge as highly promising alternatives to cisplatin (CDDP), demonstrating remarkable efficacy in inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis in the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer xenograft using the CAM model. This study highlights the CAM assay as an essential model, showcasing the ability of PtNPs to inhibit angiogenesis, reduce amino acid levels, and disrupt different sets of enzymes of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle [118].

In conclusion, the CAM model serves as an effective model for assessing reoxygenation, DNA damage repair, cell cycle redistribution, cellular radiosensitivity, and cellular repopulation—five biological concepts that are crucial for accurately predicting the responses of both tumor and normal tissues to radiotherapy and chemoradiotherapy. A recent systematic review has identified the CAM assay as a groundbreaking technique that offers a straightforward and efficient method for inducing tumors, evaluating treatment efficacy, conducting metastasis research, performing patient biopsy grafts, and advancing personalized medicine [133].

MicroRNAs are small non-coding RNA molecules with a size range of 18–25 nucleotides [130]. These molecules regulate the expression of multiple protein-encoding genes at the post-transcriptional level through repression of translation with consequent mRNA destabilization. MicroRNAs are involved in every biological process and deregulation of their expression also contributes to oncogenesis [132, 134, 135]. Research on microRNAs’ roles in carcinogenesis has been very intensive for the last two decades [136]. The CAM model is a very convenient in vivo tool for this research. Research publications, where the CAM model is applied to study functions of microRNAs in cancer, have begun to emerge. For example, the anti-angiogenesis effects of miR-1 overexpression were demonstrated on the CAM model with xenografts of prostate cancer cells [137]. Similarly, anti-angiogenic and anti-metastatic effects of miR-101 overexpression in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells were detected in the CAM model with xenografts of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells [138]. The CAM model was also applied to confirm a reduction in angiogenetic properties of ovarian cancer cells upon miR-21 activity inhibition. Particularly, a reduction in pro-angiogenic effects of conditioned medium from ovarian cancer cells upon miR-21 inhibition was detected in the CAM model of angiogenesis [139]. These studies clearly demonstrate the usefulness of the avian CAM model to decipher mechanisms, which involve microRNAs in carcinogenesis.

Multiple studies [140, 141] have linked deregulation in the expression of microRNAs in cancer to cancer chemoresistance. One such study identified an association between the upregulation of miR-153 expression and colorectal cancer aggressiveness. Further functional assays demonstrated that miR-153-mediated down-regulation of Forkhead box O3a (FOXO3a) expression increased the invasiveness of colorectal cancer cells as well as their resistance to oxaliplatin and cisplatin [142]. It is also published that alterations in let-7i, miR-16, and miR-21 levels significantly sensitize cancer cells to several anticancer drugs. In addition, a list of about thirty different microRNAs, which are associated with cancer chemosensitivity, is reported in the same study [143].

Mechanisms behind microRNA effects on cancer cell chemoresistance were discovered for some microRNAs. For example, inhibition of miR-106a in the ovarian cancer OVCAR3 cell line upregulates the programmed cell death protein 4 (PDCD4) gene expression, which sensitizes this cell line to the cisplatin treatment [144]. It is also demonstrated that miR-451 upregulation in doxorubicin-resistant Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 (MCF-7) breast cancer cells restores the doxorubicin sensitivity of these cells. Doxorubicin sensitivity in breast cancer cells is restored through expression upregulation of a miR-451 target—the Multiple drug resistance 1 (MDR1) gene encoding the P-glycoprotein [145], which belongs to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family of drug transporter proteins [146]. As we already discussed in Section 3.6, many chemotherapeutic agents kill tumor cells by inducing DNA damage, which leads to apoptosis in these cells. Noteworthily, elevated expression of the high mobility group A2 (HMGA2) protein triggers a genotoxic response to DNA double-strand breaks in cells. High expression of HMGA2 in tumor cells increases the doxorubicin sensitivity of these cells [147]. Consistently, miRNA-98 expression upregulation reduces the expression of HMGA2, which is a miR-98 target, and sensitizes carcinoma cells to doxorubicin treatment [148].

miRNA-338-3p appears to play a dual role in cancer chemotherapy, functioning either as a tumor promoter or as a tumor suppressor. Experimental evidence highlights its anti-tumor properties, suggesting that enhancing the expression of miRNA-338-3p is crucial for effective cancer treatment. Consequently, elevating the expression of miRNA-338-3p is crucial for developing effective cancer treatments. Although the recent CAM assay-based study did not directly test the hypothesis that the overexpression of MicroRNA-338-3p is linked to increased sensitivity to radiotherapy and chemotherapy [149], the findings highlight the role of miR-338-3p in promoting angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting MACC1,

A groundbreaking pharmacological study has showcased a novel bioluminescent CAM model that enhances the speed of in vivo screening for therapeutic agents while also allowing for the examination of potential epigenetic factors influencing chemosensitivity [151]. Notably, this pioneering research presents the first evidence that primary cancer cells engrafted in the CAM can be effectively treated with both standard chemotherapy and targeted agents. This study focused on a model characterized by the overexpression of c-Met due to copy number gain, a condition found in approximately 45% of patients with PDAC [152]. The combination of the c-Met/anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor crizotinib and gemcitabine resulted in a remarkable decrease in the growth of PDAC CAM tumors. Furthermore, the investigation into miRNA modulation confirmed two synergistic mechanisms: the downregulation of miR-21 and the upregulation of miR-155. The expression of miR-21 has been linked to gemcitabine resistance, resulting in a decrease in apoptosis induction [153]. Consequently, the blockade of c-Met by crizotinib, which has been shown to downregulate miR-21 in NSCLC models [154, 155], may enhance the cytotoxic effects of gemcitabine. Conversely, the increase in miR-155 levels may be attributed to a feedback mechanism triggered by the inhibition of c-Met, which is crucial for the interactions between tumors and fibroblasts. Recent research indicates that PDAC cells may stimulate nearby normal fibroblasts through the release of microvesicles rich in miR-155 [156]. These discoveries established the groundwork for a research pipeline that facilitates the effective cultivation of tumors derived from pre-treatment biopsies on the CAM. This streamlined workflow is designed to maximize productivity while minimizing the need for extensive resources and facilities. This approach has the potential to provide insights into specific tumor characteristics within just 2 to 3 weeks. It can pave the way for personalized cancer treatments and testing drug sensitivity in individual patients, while also offering a deeper understanding of the miR-mediated mechanisms behind the effects of the therapies being tested. In perspective, it could significantly accelerate in vivo screening processes for anticancer drugs, ultimately reducing both development time and costs for innovative compounds.

Overall, the effects of microRNAs on cancer chemoresistance and the mechanisms underlying these effects attract significant interest from cancer researchers. We expect the CAM model, which is ideally suited for studying both microRNA and chemoresistance, to become a standard in vivo model for this type of research.

The CAM model has gained significant traction in assessing anti-cancer therapies, due to its remarkable capability to replicate in vivo tumor growth and drug responses. In ovarian cancer research, Chitcholtan et al. (2024) [157] demonstrated the inhibitory effects of resveratrol on tumor growth using a CAM model implanted with ovarian cancer cells. Their findings not only validated the therapeutic potential of resveratrol but also showcased the CAM model’s capability to provide rapid and cost-effective insights into drug efficacy in a dynamic tumor microenvironment [157]. Similarly, Wang et al. (2024) [158] applied the CAM model to study Cluster of Differentiation 19 (CD19)-targeting Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cells (CAR-T cells) for lymphoma treatment. Their innovative approach demonstrated the CAM model’s utility in immunotherapy research, highlighting its ability to assess both therapeutic efficacy and tolerability in a preclinical setting [158]. These studies underscore the CAM model’s growing influence as a reliable tool in preclinical drug screening, facilitating the transition from in vitro studies to clinical trials.

A significant advancement lies in the integration of the CAM assay with innovative platforms like the IKOSA platform (https://www.kolaido.com/our-offerings/ikosa-ai/), designed for quantifying vasculature. This platform harnesses artificial intelligence, enabling a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of antiangiogenic strategies, especially in the area of cancer research [159]. This method not only amplifies the assay’s effectiveness but also plays a crucial role in minimizing animal usage in research by delivering more accurate data from ex ovo models. A significant advancement is to develop a culture method that harnesses the advantages of both in ovo and ex ovo techniques. Recently, Huang et al. [160] introduced an innovative cubic artificial shell that effectively overcomes the limitations of existing methods. The shell, constructed from polycarbonate and PDMS, features intricately designed microchannels on its surface that guide CAM blood vessels to grow precisely along the intended pathways dictated by these channels. The embryo developed a form reminiscent of that found within a natural shell, which significantly enhanced its survival rate to an impressive 80% after 14 days of incubation. In contrast to the ovo method, this approach features a fully transparent structure that allows for a broader view of the CAM, akin to the ex ovo method. This innovative approach holds great promise for tissue engineering by facilitating the delivery of drugs, degradation products, or even the testing of hydrogels. It allows for a thorough evaluation of their impact on angiogenesis through strategically placed openings in the external layer of the artificial shell.

Limitations of the CAM model should be taken into account along with its advantages, when the model is considered for a particular research study. These limitations can be divided into two groups: technical and fundamental. The technical limitations include the following: (1) vulnerability of the fertilized egg and its sensitivity to environmental factors such as temperature and humidity; (2) susceptibility of the chicken embryo to bacterial infection; (3) density and quick development of the CAM vascular network, which complicates studies of pro-angiogenetic factors and effects; (4) limited repertoire of available reagents such as primers, cytokines, and antibodies, which are suitable for CAM and chicken embryo studies [32, 161, 162]. The obvious fact that chickens stand evolutionary farther from humans than mice is one of the most important fundamental limitations of the CAM model. Profound differences in embryo versus adult physiologies should be regarded as the other fundamental limitation of this model. In addition, the CAM model permits only short-term experiments and cannot be applied to study long-term processes such as cancer recurrence and therapy resistance development. The limited duration of the experimental timeline imposes constraints on our ability to conduct a thorough long-term evaluation of cancer immunity in the chick embryo in ovo model. This limitation particularly hinders our understanding of the nuanced dual role that the immune system plays in the process of immunoediting. Consequently, without extended observation periods, we cannot fully assess how immune responses evolve over time in the presence of tumors. However, research conducted on animal models has demonstrated that tumor growth during the first seven days following engraftment is a strong indicator of overall survival and the effectiveness of treatment [163]. Furthermore, the short experimental time frame prevents the CAM model from experiencing substantial genetic evolution, ensuring that the harvested CAM tumor remains remarkably similar to the original tumor. In-depth studies are essential to define and assess appropriate protocols for investigating cancer immunity in ovo. Critical aspects that require clarification include the optimal timing for immune cell grafting, the most effective administration routes, the co-administration of cytokines and growth factors, and the variations depending on cell lineage. One potential solution that merits consideration involves the use of additional irradiation aimed at targeting and destroying the developing avian immune system. This approach could help prevent the maturation of the immune response in birds, ultimately extending the timeframe of immuno-oncology research. However, it is important to evaluate thoroughly this method to understand its implications and effectiveness in practical applications. An additional limitation is that while the designated compound can be detected in situ in tumor tissues and in the circulation of chickens following topical application, this does not accurately represent the systemic turnover and modification of the drug. Conversely, due to the isolated nature of the CAM, the half-life of various molecules, including small peptides, is significantly extended compared to mammalian models. This extended half-life enables the effective study of compounds that are available in limited quantities.

Despite these challenges, the CAM model remains a highly versatile and cost-effective system, particularly for preliminary investigations of cancer biology, angiogenesis, and drug screening. Its accessibility and rapid experimental timelines make it an attractive alternative to more complex in vivo models, especially during proof-of-mechanism testing or for high-throughput screening. Beyond improving the accuracy of angiogenesis assessments, advanced imaging technologies could be employed to enhance the visualization and dynamic monitoring of tumor cell metastasis patterns in vivo, and the development of reagents and tools specific to chicken embryos could expand the scope of molecular studies. Additionally, integrating the CAM model with organoids or mammalian models offers the added benefit of accelerating research processes by bridging the gap between in vitro and in vivo mouse experiments. This integration not only provides a seamless transition but also allows for the early validation of hypotheses, reducing reliance on more resource-intensive mammalian models during the initial experimental stages. Such an approach leverages the complementary strengths of each model, facilitating a more efficient and comprehensive exploration of complex biological phenomena, including post-treatment tumor recurrence, drug resistance, and distant metastasis. The CAM model of human-derived tumor cells allows transcriptomic analysis by human and chicken gene expression to determine the genetic profile of the host stroma and tumor [48]. Since neither genetic background nor gender of the chicken embryo model is standardized in any way, this model is expected to be more robust and closer to the natural genetic heterogeneity of the human cancer patient population. We can assume that this should contribute to the reproducibility of preclinical data obtained on the chicken embryo in clinical trials, although such an assumption requires rigorous verification.

In summary, while the CAM model has inherent limitations, its unique advantages justify continued exploration and refinement. Future advancements in methodologies and cross-species validation could further enhance the applicability and reliability of this model, solidifying its role as a valuable tool in preclinical and translational research.

The CAM tumor xenograft-bearing model is an inexpressive in vivo model suitable for both basic cancer research and the development of cancer therapies. Cancer research directions, which can be pursued with the chicken CAM model, are numerous and discussed in this review. The low costs of this in vivo model permit large experimental and control groups, which creates high statistical power of CAM model experiments. The short experimental time allows quick repeats of the CAM experiments, which further enhances the robustness of generated experimental data. The lack of nociception in the early chicken embryo drastically simplifies compliance with the ethical 3R regulations. A relative disadvantage of the CAM is the absence of direct comparisons between mouse models and CAM models for specific applications, which complicates the validation and adoption of these models in research and development processes. In addition, researchers adhering to traditional approaches perceive enhanced heterogeneity and reduced standardization of the CAM as a disadvantage. Together, these issues significantly impede the progress and effectiveness of CAM implementations in various scientific fields. In this context, our current review wholeheartedly endorses the invaluable proposal to establish a dedicated organization for CAM researchers and regulators within a CAM society [164]. This initiative aims to effectively tackle the challenges identified in CAM research. The discussed advantages of the CAM model over the other in vivo models suggest that applications of the in ovo model will become more prominent in cancer research. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis conducted in a recent proteomic study revealed significant enrichment in terms related to endocytosis, focal adhesion, and gap junctions [165]. These findings underscore the critical structure-function relationships among the constituents of CAM proteins, suggesting their potential to broaden biomedical applications of CAM models [166, 167]. The recent comprehensive review suggests that the integration of various models can be a highly advantageous strategy to enhance both basic and translational research efforts [168]. The discussed advantages of the chick and ostrich CAM models compared to other in vivo models indicate that the in ovo model is poised for increased utilization across various research fields, including cancer studies, biomaterials evaluation, tissue engineering, drug delivery and toxicity assessment, dental biology, and regenerative medicine. The avian embryo model is anticipated to significantly enhance the validity of in vivo research data by complementing existing studies.

Drawing from this review, we suggest categorizing the innovative technological applications of CAM models into three key areas.

(1) Molecular and genetic research. This category encompasses studies that leverage the CAM model to investigate molecular and genetic mechanisms underlying cancer development and progression. The CAM platform allows rapid genetic manipulation and high-throughput screening, providing distinct advantages over traditional animal models. Notably, recent advancements have expanded the CAM’s application in exploring miRNA-mediated tumor regulation, gene silencing, and oncogene/tumor suppressor gene functions. Researchers have used the CAM model to quickly validate miRNA targets in vivo, confirming their impact on tumor growth, spread, and resistance to chemotherapy. The CAM is an ideal model for molecular oncology research due to its easy genetic manipulation and short experimental timeframe, providing a unique, efficient, and cost-effective alternative to mammalian systems.

(2) Tumor-microenvironment interaction studies. The CAM model effectively mimics important features of the tumor microenvironment, such as blood vessels, ECM components, and interactions between stromal and tumor cells, which are often poorly represented in traditional in vitro models like two-dimensional cell cultures or even three-dimensional matrices (e.g., organoids and spheroids). Conventional in vitro systems do not replicate the complexity of natural ECM structures and cellular interactions, and mouse models are costly and slow. CAM models provide a vascularized and accessible microenvironment, allowing for quick observation of tumor-stroma interactions, ECM remodeling, angiogenesis, and tumor cell invasion. These attributes improve studies on the interaction between tumor cells, stromal cells, and ECM, leading to a better understanding of metastasis and chemoresistance.

(3) Immuno-oncology and therapeutic screening studies. Effective immunotherapy research requires a healthy and functional blood system to transport immune cells, nutrients, and treatments to tumors. Standard in vitro assays do not capture vascular complexity well, and traditional mouse models, while more relevant to physiology, can be costly, ethically problematic, and time-consuming. The CAM model circumvents these limitations by inherently possessing a robust, functional vascular system accessible for intravascular administration of therapeutic agents, including immunotherapeutic drugs and engineered immune cells (e.g., CAR-T cells). Recent studies highlight the CAM’s potential for evaluating immunotherapy efficacy, immune cell infiltration, and real-time therapeutic responses [51, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81]. The CAM offers a fast and cost-effective way to screen immuno-oncology drugs, helping to connect lab studies with clinical applications.

Despite the advantages of CAM models, such as rapid results, cost efficiency, and strong statistical power, challenges related to experimental variation and lack of standardization have restricted their use. International collaboration is needed to create uniform CAM methodologies and regulations. This will help overcome current challenges ensuring consistency in cancer research and clinical studies. The CAM model has significant potential to advance oncology through its integration with precision medicine, such as PDX and novel imaging technologies. Recent proteomic study [165] has linked the CAM to key cancer pathways like endocytosis, focal adhesion, and gap junction signaling, highlighting its importance in understanding cancer biology and treatment responses. Integrating CAM-based platforms with cutting-edge technologies is crucial for enhancing the impact and translational value of future preclinical and clinical research.

YW—Conceptualization, Reference Collection and Analysis, Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Writing—Review & Editing. WX—Software, Visualization, The acquisition of literature, Writing—Review & Editing. MP—Design of the work, Writing—Review & Editing DNA—damaging therapeutics in cancer section. DVK—The acquisition of literature, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition, Writing—Review & Editing. SL—Conceptualization, Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The micrograph presented in this study on Fig. 3 was obtained from chick embryos at day 9 of gestation. According to the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and IACUC, chick embryos do not develop the capacity to perceive pain before day 14 of gestation; therefore, the use of embryos at this stage does not require ethical approval.

We express our gratitude for the invaluable editing suggestions provided by all the peer reviewers and Dr. Vadim Maximov.

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 23-14-00220).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.