1 Department of Neurosurgery, Chiayi Christian Hospital, 60002 Chiayi, Taiwan

2 Department of Neurosurgery, Tainan Municipal Hospital (Managed by Show Chwan Medical Care Corporation), 70173 Tainan, Taiwan

3 Department of Cell Biology and Anatomy, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, 70101 Tainan, Taiwan

4 Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, 70101 Tainan, Taiwan

5 Department of Neurosurgery, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, 70403 Tainan, Taiwan

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Mitochondria are essential for cellular energy production and cell survival. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been implicated in various neurological disorders, prompting the development of novel therapeutic approaches targeting these organelles. Among these, mitochondrial transplantation (MT), which replaces dysfunctional mitochondria with healthy counterparts from donor tissues, has emerged as a promising strategy. While skeletal muscle is a rich source of mitochondria, the optimal muscle tissue for MT remains unidentified, and the potential functional differences among mitochondria from various muscle types are not fully understood. This study investigates the quantity, size, respiratory function, energy production, and anti-inflammatory effects of mitochondria isolated from red skeletal muscle (RSM), mixed skeletal muscle (MSM), and white skeletal muscle (WSM).

Mitochondria were extracted from the soleus muscle (RSM), pectoralis major and rectus abdominis (MSM), and biceps brachii and gastrocnemius (WSM) of healthy 8-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats. Nanoparticle tracking analysis was employed to determine mitochondrial quantity and size. The activities of mitochondrial complexes I, II, and IV and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) content were assessed. The protective effects of mitochondria (100 μg/mL) from each muscle type against lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 5 μg/mL)-induced cell death and mitochondrial membrane potential disruption were evaluated in PC-12 neuronal cells.

RSM-derived mitochondria exhibited a smaller average size and significantly higher mitochondrial content compared to those from MSM (mean size: p = 0.0056, vs. pectoralis major; p = 0.0056, vs. rectus abdominis; count of mitochondria: p < 0.0001, vs. pectoralis major; p < 0.0001, vs. rectus abdominis) and WSM (mean size: p = 0.0006, vs. biceps brachii; p < 0.0001, vs. gastrocnemius; count of mitochondria: p < 0.0001, vs. biceps brachii; p < 0.0001, vs. gastrocnemius). Additionally, RSM mitochondria demonstrated the highest activity of mitochondrial complex I among the three muscle types (p = 0.0001, vs. pectoralis major; p = 0.0095, vs. rectus abdominis; p < 0.0001, vs. biceps brachii; p < 0.0001, vs. gastrocnemius). WSM-derived mitochondria showed relatively lower complex II activity (p = 0.0006, biceps brachii vs. soleus; p = 0.0218, biceps brachii vs. rectus abdominis), while complex IV activity and ATP content were comparable across all groups. Supplementation with mitochondria isolated from RSM and WSM, but not MSM, effectively mitigated LPS-induced cell death (mitochondria isolated from soleus: p = 0.0031; biceps brachii: p = 0.0046; gastrocnemius: p = 0.0169) and preserved mitochondrial membrane potential (mitochondria isolated from soleus: p = 0.0204; biceps brachii: p = 0.0086; gastrocnemius: p = 0.0001) in PC-12 cells.

RSM emerges as the optimal source for mitochondrial extraction, demonstrating superior respiratory activity and significant protective effects against LPS-induced cell death and mitochondrial dysfunction. These findings provide critical insights into optimizing MT outcomes through the strategic selection of mitochondrial sources.

Keywords

- adenosine triphosphate

- lipopolysaccharide

- mitochondrial membrane potential

- mitochondrial dysfunction

- skeletal muscle

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a significant challenge observed across a spectrum of conditions, including neurodegenerative diseases [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10], sarcopenia, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [11], diabetes [12], obesity [13], cancers [14, 15, 16, 17], Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy [18, 19], and cardiovascular diseases [20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. Mitochondria are essential organelles responsible for generating energy, regulating cellular metabolism, and maintaining cellular homeostasis. They play a crucial role in determining cell survival by controlling pathways related to energy production, apoptosis, and the cellular stress response [29]. When mitochondrial function is compromised, it disrupts cellular metabolism, leading to an accumulation of oxidative stress, which can further impair mitochondrial function. This, in turn, affects the ability of mitochondria in producing adenosine triphosphate (ATP), regulating calcium levels, and managing cellular damage [30]. Mitochondrial dysfunction is also linked to the failure of mitophagy, a selective process by which damaged mitochondria are degraded. When mitophagy is impaired, dysfunctional mitochondria accumulate, worsening cellular stress and triggering cell death pathways. Given that mitochondria are crucial in regulating apoptosis, the buildup of damaged mitochondria can overwhelm the cell’s defenses, leading to irreversible damage and cell death [31, 32].

As a result, restoring mitochondrial function has emerged as a pivotal area of research focus, employing pharmacological interventions [33], mitochondrial replacement [34], gene [35], and stem cell therapies [36]. Among these, mitochondrial transplantation (MT), involving the direct transplantation of healthy mitochondria into affected sites to replace or rescue dysfunctional ones, stands out as a notable strategy. This technique has attracted considerable attention from researchers owing to its capacity to rapidly augment mitochondrial function [37]. MT has shown promising results in rectifying and augmenting cellular bioenergetics, structural integrity, and functional capacity, thereby mitigating oxidative stress and inflammation [38, 39, 40, 41]. Furthermore, it has the potential to impede cancer cell migration and enhance sensitivity to chemotherapy [16]. Consequently, MT represents a promising avenue for therapeutic interventions, particularly in diseases associated with mitochondrial dysfunction [18].

Based on a literature review, the potential donor sources for MT include a range of tissues, such as neural cells, mesenchymal stem cells, fibroblasts, adipocytes, cardiomyocytes, and skeletal muscle cells (Supplementary Table 1) [7, 8, 9, 10, 16, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79]. A previous study reported that mitochondria derived from organs with a high energy demand, such as the heart, lung, or muscle, exhibit more robust respiratory profiles than those sourced from low-energy-demand organs, such as the spleen or kidney [80]. In particular, muscle-derived mitochondria retain the highest intact membrane potential, compared to those sourced from the brain, brown adipose tissue, or white adipose tissue, as assessed using the JC-1 assay [81].

The skeletal muscle, which is rich in mitochondria and possesses a higher concentration than the myocardium [28], holds substantial promise as a source of mitochondria for MT because of its widespread distribution throughout the body [82] and remarkable regenerative capacity [83]. For example, mitochondria derived from the pectoralis major muscle have been shown to improve motor function in rats following ischemic stroke [84], whereas those from the gastrocnemius muscle enhance lung mechanics and mitigate lung tissue injury in mice subjected to ischemia-reperfusion damage [43]. Furthermore, the transplantation of mitochondria isolated from various muscle sources has been shown to exert therapeutic benefits in several diseases (Table 1) [9, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 38, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 84]. Nevertheless, the optimal skeletal muscle tissue to achieve the highest MT efficacy has not yet been clearly characterized.

| Author, year | Animal | Disease model | Source of mitochondria | Dose | Main outcomes | Refs |

| Shi et al., 2017 | C57BL/6 mice | Parkinson’s diseases | Multiple tissues, including brain, liver, kidney, muscle, and heart tissues of mice | 0.5 mg/mL | Increasing the activity of electron transport chain, decreasing reactive oxygen species level, and preventing cell apoptosis and necrosis | [9] |

| Zhao et al., 2021 | C57BL/6 mice | Traumatic brain injury | Allogeneic liver, and autogenic muscle | 1.2–1.4 × 106 particles | Reducing neuronal apoptosis, attenuating anxiety, and improving spatial memory | [42] |

| Zhang et al., 2019 | SD rats | Cerebral ischemic injury | Pectoralis major muscle (WSM) | 5 × 106 particles | Improving motor functions and reducing infarct volume and apoptosis | [84] |

| Hsu et al., 2022 | SD rats | Pulmonary hypertension | Soleus muscle (RSM) | 100 µg | Restoring the contractile phenotype and vasoreactivity of the pulmonary artery, and reducing the afterload and right ventricular remodeling | [44] |

| Yan et al., 2020 | C57BL/6 mice | Sepsis-associated brain dysfunction | Pectoralis major muscle (WSM) | 4 × 106/5 µL | Decreasing cognitive impairments and improving microglial polarization from the M1 phenotype to the M2 phenotype | [45] |

| Fang et al., 2021 | SD rats | Spinal cord ischemia | Soleus muscle (RSM) | 100 µg | Reducing neuroapoptosis and improving locomotor function | [46] |

| Gollihue et al., 2018 | SD rats | Spinal cord injury | Soleus muscle (RSM) | 100 µg | Rapidly increasing mitochondrial bioenergetics for injured spinal cord | [38] |

| Shin et al., 2019 | Yorkshire pigs | Ischemia heart | Pectoralis major muscle (WSM) | 1 × 109 particles | Enhancing myocardial function and reducing the infarct size | [47] |

| Emani et al., 2017 | Human | Ischemia heart | Rectus abdominis muscle (WSM) | 1 × 107 |

Improving ventricular function | [48] |

| Guariento et al., 2021 | ECMO patients | Ischemia heart | Rectus abdominis muscle (WSM) | 2 × 1010 particles | Cardiovascular events were lower in the MT group | [49] |

| Guariento et al., 2020 | Yorkshire pigs | Ischemia heart | Pectoralis major muscle (WSM) | 5 × 109 particles | Preserving myocardial function and oxygen consumption | [22] |

| Weixler et al., 2021 | Yorkshire piglets | Right heart failure | Gastrocnemius muscle and soleus muscle | 10 × 106/mL | Inducing prolonged physiologic adaptation of the pressure-loaded right ventricular and preservation of contractility by reducing apoptotic cardiomyocyte loss | [25] |

| Alemany et al., 2024 | Yorkshire pigs | Hearts donated after circulatory death | Skeletal muscle (MSM) | 5 × 109 particles | Enhancing the preservation of myocardial function and viability and mitigating damage secondary to extended warm ischemia time | [23] |

| Doulamis et al., 2020 | Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF fa/fa) rats | Type 2 diabetes heart | Pectoralis major muscle (WSM) | 2 × 105 |

Increasing ATP content levels and decreasing myocardial infarction area | [21] |

| Blitzer et al., 2020 | Yorkshire pigs | Focal ischemia | Pectoralis major muscle (WSM) | 1 × 109 particles | Reducing myocardial infarct size and enhancing regional and global myocardial function | [50] |

| Moskowitzova et al., 2019 | C57BL/6 mice | Focal ischemia | Gastrocnemius muscle (MSM) | 1 × 108 particles | Enhancing graft function and decreasing graft tissue injury | [24] |

| Orfany et al., 2020 | C57BL/6 mice | Focal ischemia | Muscle (MSM) | 1 × 106–1 × 109 particles | Decreasing infarct size and apoptosis and improving hindlimb function | [51] |

| Moskowitzova et al., 2020 | C57BL6 mice | Focal ischemia | Gastrocnemius muscle (MSM) | 1 × 108, or 3 × 108 particles | Improving lung mechanics and decreasing lung tissue injury | [43] |

| Pang et al., 2022 | SD rats | Acute lung injury | Soleus muscle (RSM) | 100 µg | Protecting the integrity of endothelial lining of the alveolar-capillary barrier and improving gas exchange during the acute stages | [52] |

| Rossi et al., 2023 | Yorkshire pigs | Acute kidney injury | Psoas muscle (WSM) | 0.5 mL | Reducing damage level | [53] |

| Doulamis et al., 2020 | Yorkshire pigs | Acute kidney injury | Sternocleidomastoid muscle (RSM) | 1 × 109 particles | Reducing serum creatinine and enhancing glomerular filtration rate | [54] |

| Jabbari et al., 2020 | Wistar rats | Acute kidney injury | Pectoralis major muscle (WSM) | 7.5 × 106 particles | Preventing damages to renal cells/tissues and enhancing regenerative potential of renal cells | [55] |

| Lee et al., 2021 | SD rats | Tendinopathy | Skeletal muscle (MSM)L6 cells | 10 and 50 µg | Reducing inflammatory and fission | [56] |

| Hwang et al., 2021 | SD rats | Sepsis | Skeletal muscle (MSM)L6 cells | 50 µg | Improving survival and bacterial clearance and exerting an immunomodulatory effect | [57] |

SD rats, Sprague-Dawley rats; RSM, red skeletal muscle; MSM, mixed skeletal muscle; WSM, white skeletal muscle; MT, mitochondrial transplantation; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Skeletal muscles are highly conserved tissues essential for locomotion and posture, forming an interconnected network with the skeletal system to facilitate movement. In vertebrates, skeletal muscles are generally categorized into red skeletal muscle (RSM) and white skeletal muscle (WSM), with an intermediate type known as mixed skeletal muscle (MSM) [85]. Red fibers (slow-twitch, oxidative fibers) are characterized by their small diameter, high myoglobin content, and dense capillary supply. They also contain numerous large mitochondria located beneath the sarcolemma and between the myofibrils, along with lipid droplets in the sarcoplasm [86]. These features enable red fibers to sustain prolonged contractions and resist fatigue due to their reliance on oxidative phosphorylation, making them predominant in postural muscles such as the soleus and deep back muscles [87]. In contrast, white fibers (fast-twitch, glycolytic fibers) are larger in diameter, contain fewer mitochondria and lipid droplets, and primarily depend on anaerobic metabolism [86]. These properties make them well-suited for rapid and powerful contractions, as seen in muscles like the gastrocnemius [86]. MSM exhibit a combination of oxidative and glycolytic metabolic properties. Given the distinct bioenergetic profiles of these muscle types [82], their mitochondrial function may vary significantly. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation into the structural and functional characteristics of mitochondria from RSM, MSM, and WSM is essential for identifying the optimal source for MT and advancing its clinical application.

To bridge this knowledge gap, we categorized skeletal muscles into RSM (soleus), MSM (pectoralis major and rectus abdominis), and WSM (biceps brachii and gastrocnemius) based on previous reports [88, 89, 90] and isolated purified mitochondria from these muscle types in rats. We quantified the mitochondrial size and number, and assessed mitochondrial respiratory chain activity and ATP production. Building on our previous findings that transplanted mitochondria can suppress inflammagen-induced inflammation in primary dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons [3], we further evaluated the effects of mitochondria from these muscle types on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced cell death and mitochondrial membrane potential imbalance in PC-12 neuronal cells. These findings provide essential insights that will help researchers to address knowledge gaps in the field of MT research and support the advancement of its therapeutic applications.

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC approval number: 113033) of National Cheng Kung University in Tainan, Taiwan. Eight-week-old male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (n = 40, weight: 250–300 g, procured from BioLASCO Nangang District, Taipei, Taiwan) were used as mitochondrial donors in the experiments. The rats were housed separately in ventilated cages, with ad libitum access to food and water, and maintained under controlled environmental conditions at approximately 24 °C with humidity ranging from 45% to 65%. The rats were exposed to 11-h light and 13-h dark cycles, with lights on at 7 AM. All experimental procedures were conducted during the light phase.

Functional mitochondria were extracted from the RSM (soleus muscle), MSM (pectoralis major

and rectus abdominis), and WSM (biceps brachii and gastrocnemius) of healthy

donor rats. In brief, donor rats were placed in a prone position and deeply

anesthetized using 4–5% isoflurane (Panion & BF Biotech Inc., Taipei, Taiwan)

administered via inhalation at a flow rate of 1 L/min. Incisions were made at the

targeted sites, and the superficial connective tissues were carefully removed to

expose the designated muscles. The muscle specimens of interest were dissected,

and the donor rats were euthanized by inhalation of an overdose of isoflurane

(~10%). Muscle samples with the same wet weight were excised,

fragmented into small pieces, and homogenized in mitochondrial isolation solution

provided in mitochondria isolation kit (Cat. # 89801; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Waltham, MA, USA) using a glass tissue grinder (Cat. # CLS-5007-02, Chemglass

Inc, Vineland, NJ, USA). The resultant homogenates were centrifuged at 700

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) was applied to determine the size

distribution of the mitochondria isolated from the various skeletal muscle types.

Mitochondrial samples were diluted with 0.1 µm-filtered PBS (particle count

The activities of complexes I, II, and IV within the isolated mitochondria (100 µg per sample, directly measured using a microbalance) were assessed using commercial assay kits (complex I: Cat. #: 700930; complex II: Cat. #: 700940; complex IV: Cat. #: 700990, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance readings were recorded at 340 nm for the complex I assay, 600 nm for the complex II assay, and 550 nm for the complex IV assay. The obtained values were normalized to those from the vehicle control group (mitochondria isolation buffer).

The ATP content in the isolated mitochondria (100 µg per sample, directly measured using a microbalance) was determined using a commercial assay kit (Cat. #: ab83355, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance readings were recorded at 570 nm.

Rattus PC-12 cells (Cat#: CRL-1721, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA; RRID: CVCL_0481),

validated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and confirmed to be

mycoplasma-free, were used in this study. The PC-12 cells were cultured in RPMI

1640 medium (Cat#: A1049101, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (Cat#: TMS-013-BKR, Merck-Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA;

Lot#: VP2002200, endotoxin

Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Cat#: ALX-850-039, Enzo Life Sciences, Long Island, NY, USA). PC-12 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells per well and subjected to the designated treatments. Subsequently, 10 µL of Cell Counting Kit-8 reagent was added to each well containing 90 µL of culture medium. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour, after which the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Model: SpectraMax iD5, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Cell viability was determined as a percentage of the untreated vehicle control group and reported accordingly.

A commercial JC-1 assay kit (Cat#: 10009172, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was used to assess the mitochondrial membrane potential in PC-12 cells. Following the LPS and mitochondria treatments, JC-1 staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 24 hours after the initiation of allogenic mitochondrial treatment, the culture medium was removed and replaced with fresh medium containing 1% JC-1 stock solution. After incubating at 37 °C for 30 minutes, the cultures were washed with the provided JC-1 buffer and prepared for further analysis. Fluorescence intensities were measured using a fluorescence plate reader (Model: SpectraMax iD5, Molecular Devices) at Ex/Em: 535/595 nm (red) and Ex/Em: 485/535 nm (green). The red-to-green fluorescence intensity ratio was calculated and presented. For imaging, PC-12 cells were seeded in 8-well chamber slides, treated, and stained with JC-1 under identical conditions. Fluorescent images were captured using a fluorescence microscope system (Model: Axiovert 5 digital, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a digital camera.

Numerical data are presented as the mean

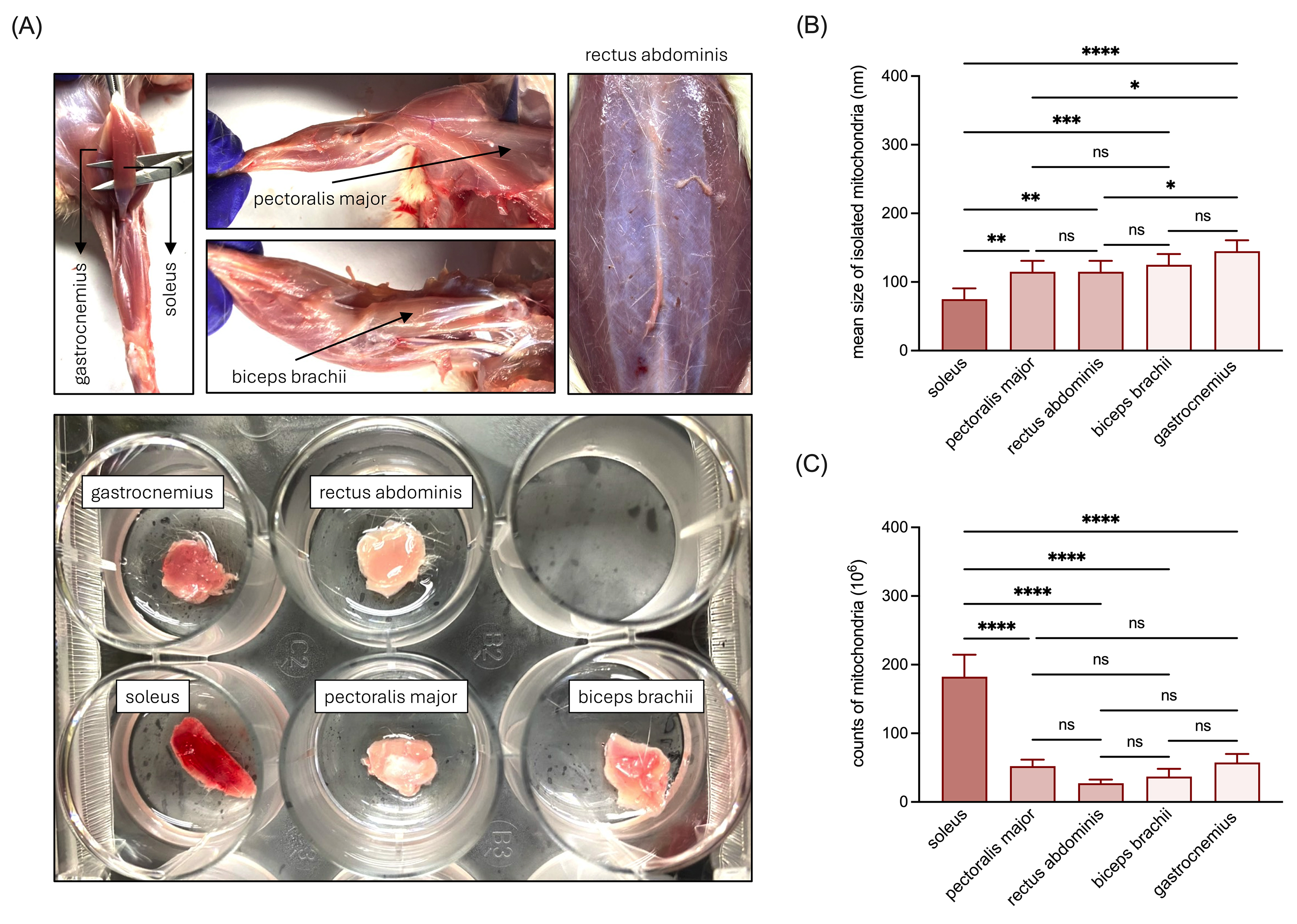

We collected various muscle types from rats, including samples of the RSM (soleus), MSM (pectoralis major and rectus abdominis), and WSM (biceps brachii and gastrocnemius) (Fig. 1A), from which mitochondria were isolated. NTA analysis revealed that the average mitochondrial size decreased in the order of WSM, MSM, and RSM, with soleus-derived mitochondria exhibiting the smallest size (Fig. 1B). Additionally, RSM exhibited a significantly higher mitochondrial abundance compared to WSM and MSM (Fig. 1C), while the numbers of mitochondria isolated from WSM and MSM were comparable (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of the size and abundance of mitochondria

isolated from RSM, MSM, and WSM. (A) Representative images of the collected RSM

(soleus), MSM (pectoralis major and rectus abdominis), and WSM (biceps brachii

and gastrocnemius) tissues. (B) Quantitative analysis of the mean size of

isolated mitochondria. (C) Quantitative analysis of the quantity of isolated

mitochondria. Data are presented as mean

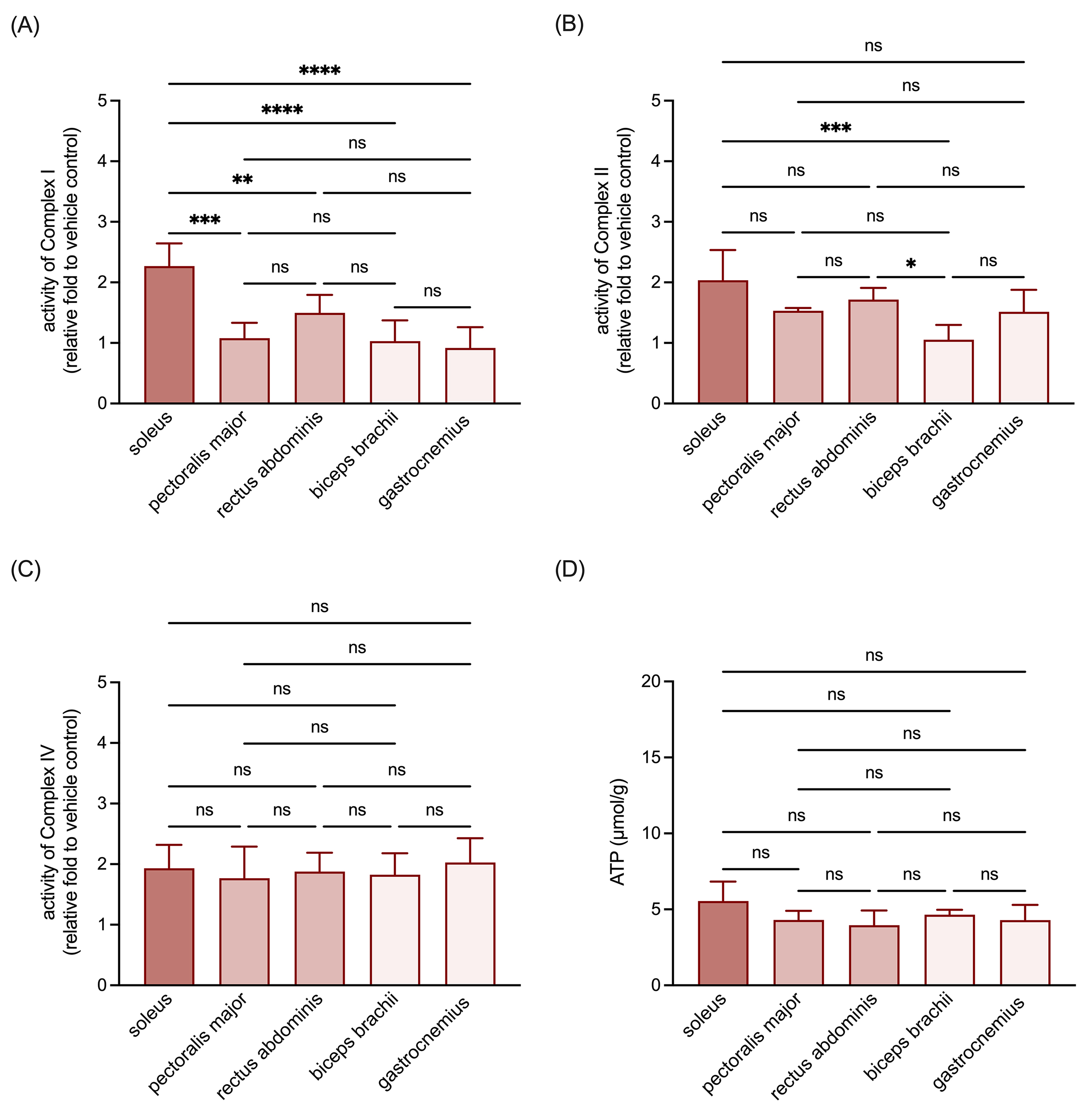

Given the pivotal role of the oxidative phosphorylation complexes in mitochondrial functionality and cellular energy metabolism, we examined how the muscle origin influences the activity of complexes I, II, and IV within isolated mitochondria. These analyses revealed that the activity of complex I in mitochondria isolated from RSM was higher than that observed in the mitochondria isolated from MSM and WSM (Fig. 2A). Regarding complex II activity, a relative decrease was noted in mitochondria isolated from biceps brachii, one of the selected WSM (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the activity of complex IV (Fig. 2C) and the ATP content (Fig. 2D) of mitochondria from all selected muscle tissues were similar. These findings collectively suggest that mitochondria isolated from RSM exhibit superior respiratory chain activity.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of respiratory chain complex activities and ATP

content in the mitochondria isolated from RSM, MSM, and WSM. (A) Quantitative

results of activity of complex I in the isolated mitochondria. (B) Quantitative

results of activity of complex II in the isolated mitochondria. (C) Quantitative

results of activity of complex IV in the isolated mitochondria. (D) Quantitative

results of ATP content in the isolated mitochondria. Data are expressed as

mean

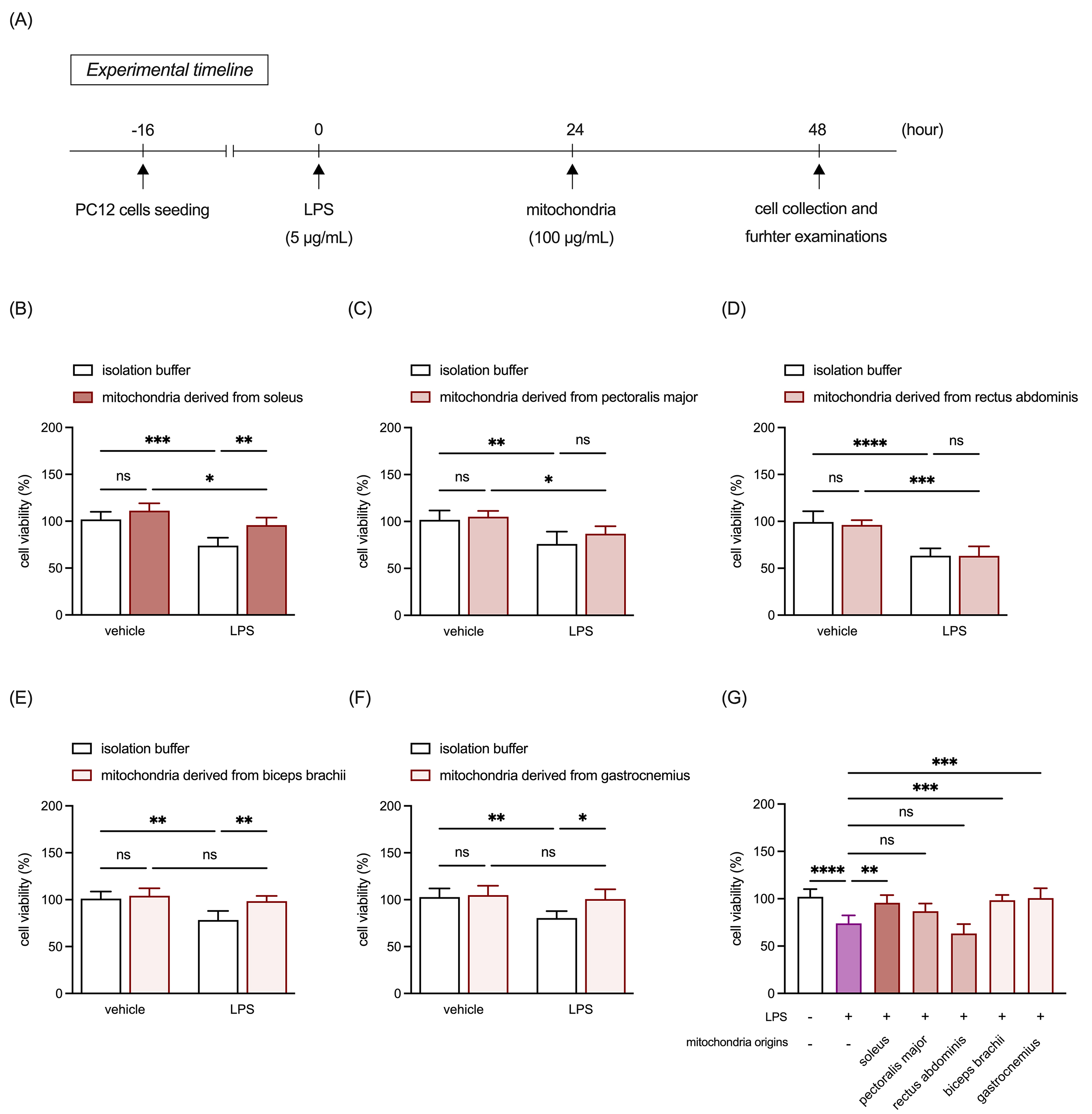

Based on our previous findings that transplanted mitochondria can mitigate inflammagen-induced inflammation in primary DRG neurons [3], we subsequently examined the protective effects of mitochondria from different muscle types against LPS-induced cell death and mitochondrial membrane potential disruption in PC-12 neuronal cells. Sixteen hours after seeding, cultures were treated with 5 µg/mL LPS, or an equivalent volume of vehicle control for 24 hours. Subsequently, 100 µg/mL allogeneic mitochondria or an equivalent volume of mitochondria isolation buffer was added to the cultures and incubated for another 24 hours. After incubation, the cultures underwent further analyses (Fig. 3A). The results revealed that LPS treatment significantly increased PC-12 cell death across all assays (Fig. 3B–G). Post-treatment with mitochondria derived from RSM (Fig. 3B,G) and WSM (Fig. 3E–G), but not MSM (Fig. 3C,D,G), effectively mitigated LPS-induced damage.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of protective effects of mitochondria isolated from

RSM, MSM, and WSM on LPS-induced cell death in neuronal cells. (A) Schematic of

the experimental timeline. (B) Quantitative analysis of cell viability in PC-12

cultures treated with LPS and mitochondria isolated from the soleus. (C)

Quantitative analysis of cell viability in PC-12 cultures treated with LPS and

mitochondria isolated from the pectoralis major. (D) Quantitative analysis of

cell viability in PC-12 cultures treated with LPS and mitochondria isolated from

the rectus abdominis. (E) Quantitative analysis of cell viability in PC-12

cultures treated with LPS and mitochondria isolated from the biceps brachii. (F)

Quantitative analysis of cell viability in PC-12 cultures treated with LPS and

mitochondria isolated from the gastrocnemius. (G) Comparison of the effects of

mitochondria derived from all selected muscle tissues on LPS-induced cell death

in PC-12 cultures. Data are expressed as

mean

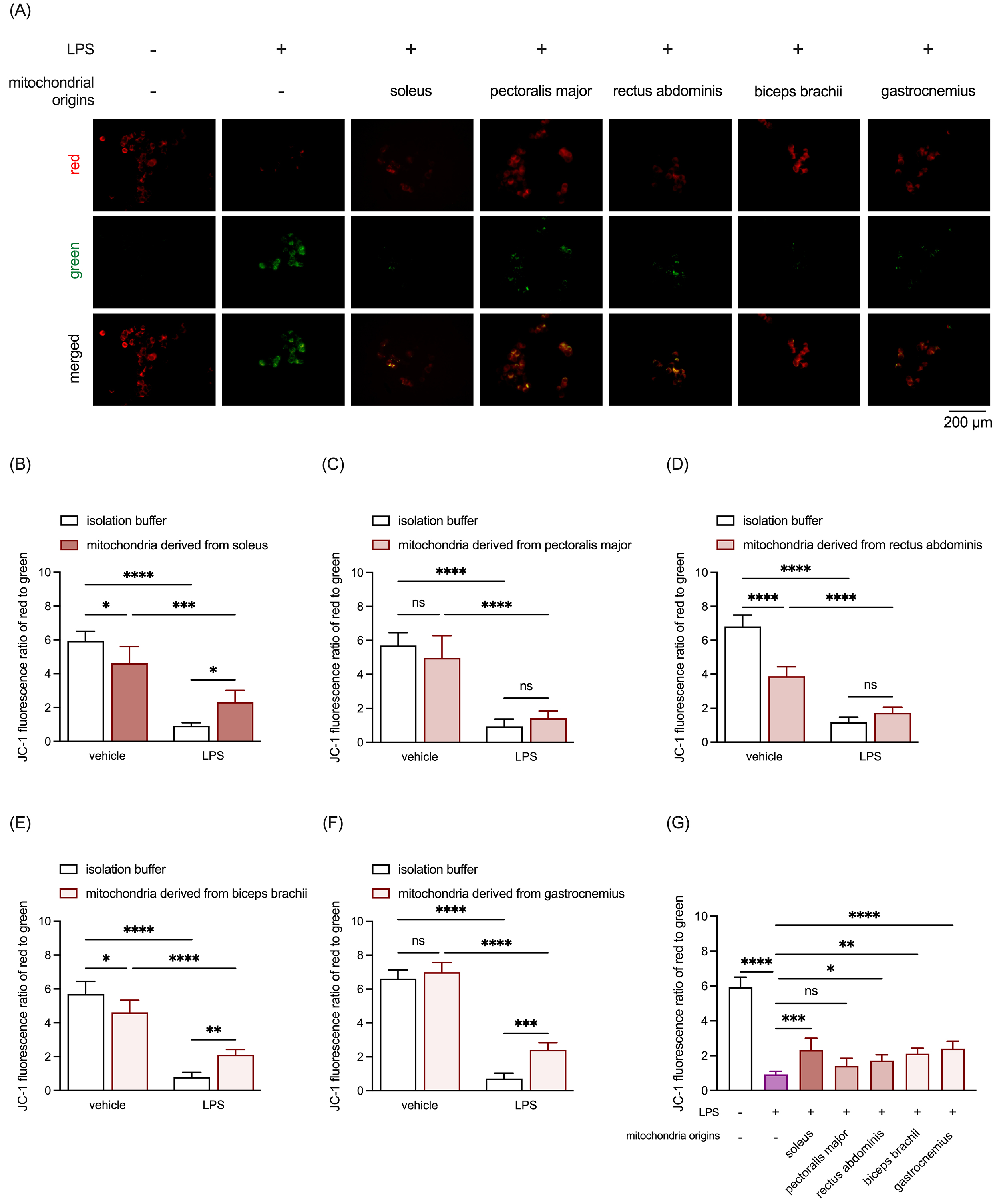

JC-1 staining was employed to evaluate mitochondrial membrane potential. LPS markedly reduced the JC-1 fluorescence red-to-green ratio, a key indicator of mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 4). Similar to the cell viability assay results, treatment with mitochondria derived from the RSM (Fig. 4A,B,G) and WSM (Fig. 4A,E–G), but not the MSM (Fig. 4A,C,D), restored mitochondrial membrane potential disrupted by LPS. Unexpectedly, supplementation with allogeneic mitochondria from the soleus (Fig. 4B), rectus abdominis (Fig. 4D), and biceps brachii (Fig. 4E) resulted in a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in LPS-untreated PC-12 cultures. These findings highlight the differential neuroinflammation-protective capacities of mitochondria from distinct muscle types, with RSM and WSM mitochondria effectively mitigating LPS-induced cell death and preserving mitochondrial membrane potential in PC-12 cells. Moreover, the results underscore the dual effects of allogeneic mitochondria supplementation, which may vary depending on the inflammatory state of neuronal cells.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of protective effects of mitochondria isolated from

RSM, MSM, and WSM on LPS-induced mitochondrial membrane potential loss in

neuronal cells. (A) Representative JC-1 staining images. Scale bar: 200

µm. (B) Quantitative analysis of JC-1 staining results in PC-12 cultures

treated with LPS and mitochondria isolated from the soleus. (C) Quantitative

analysis of JC-1 staining results in PC-12 cultures treated with LPS and

mitochondria isolated from the pectoralis major. (D) Quantitative analysis of

JC-1 staining results in PC-12 cultures treated with LPS and mitochondria

isolated from the rectus abdominis. (E) Quantitative analysis of JC-1 staining

results in PC-12 cultures treated with LPS and mitochondria isolated from the

biceps brachii. (F) Quantitative analysis of JC-1 staining results in PC-12

cultures treated with LPS and mitochondria isolated from the gastrocnemius. (G)

Comparison of the effects of mitochondria derived from all selected muscle

tissues on LPS-induced mitochondrial membrane potential loss in PC-12 cultures.

Data are expressed as mean

The present study aimed to determine the optimal skeletal muscle source for mitochondrial isolation in MT. Our findings demonstrated that mitochondria isolated from the RSM were smaller on average compared to those from the WSM and MSM. Furthermore, the RSM contained a significantly higher abundance of mitochondria than the MSM and WSM. Functionally, RSM-derived mitochondria exhibited the highest mitochondrial complex I activity among the three muscle types, whereas mitochondria from the biceps brachii (a selected WSM) showed relatively reduced complex II activity. In contrast, the complex IV activity and ATP content were comparable across all selected muscle tissues. When assessing the potential of allogeneic mitochondria isolated from different muscle types for counteracting neuroinflammation, we observed that mitochondria from the RSM and WSM, but not the MSM, effectively mitigated LPS-induced cell death and preserved mitochondrial membrane potential in PC-12 neuronal cells. Collectively, these results indicate that RSM is the optimal source for mitochondrial isolation when efficiency is evaluated based on the mitochondrial yield from muscles of equivalent weight, independent of wound location. These findings offer valuable insights and establish a foundation for improving mitochondrial therapy by identifying an ideal mitochondrial source to maximize therapeutic outcomes.

Mitochondrial characteristics significantly affect the essential cellular processes. In this study, we found that RSM contained a notably higher proportion of smaller mitochondria and a greater overall mitochondrial count than WSM and MSM. Notably, mitochondrial size was identified as a factor that influences mitochondrial membrane potential [91]. Indeed, it has been reported that an increase in mitochondrial mass or enhanced mitochondrial membrane potential corresponds to a higher rate of transcription and translation per unit volume [92, 93]. Miettinen and Björklund [94] previously proposed that mitochondrial functionality peaks in intermediate-sized cells within a population. Interestingly, the distribution of mitochondria varies among different cellular structures. For example, in neurons, axonal mitochondria tend to be smaller and less abundant, whereas dendritic mitochondria are larger and more densely concentrated [95]. Furthermore, various diseases require different mitochondrial doses. Notably, we advocate offering mitochondria of diverse sizes to meet specific needs, ensuring an optimal selection for mitochondrial applications.

Prior research has indicated that 75% of the variation in cellular translation rates is attributable to mitochondrial activity [94]. While a previous study compared the protein composition of extracted mitochondria from the RSM and WSM, it did not evaluate their quantity or detailed respiratory functions [96]. Within the respiratory chain, complex I serves as the primary entry point, and deficiencies in its function can result in significant bioenergetic deficits and mitochondrial instability. The findings of this study revealed that RSM exhibited significantly higher complex I activity compared to WSM and MSM. Elevated levels of the complex I substrate NADH, likely due to complex I dysfunction, have been associated with the resistance of certain cancer cells to apoptosis [17]. In the mitochondria associated with ischemic heart disease, complex I activity decreases by 25% [27], and treatments, such as continuous MT administration for seven days, are required for toxin-induced liver injury [75]. Regarding complex II activity, the WSM showed a relatively lower activity than the RSM and MSM. Previous research indicates that a high-fat, high-sucrose diet reduces cardiac mitochondrial ATP synthesis and complex II activity [13]. Similarly, Rochester et al. [97] demonstrated reduced activity of succinate dehydrogenase, a component of complex II in the electron transport chain, in the skeletal muscles of individuals with chronic spinal cord injury. Conversely, our results revealed no significant differences in complex IV activity across the different muscle types. Complex IV, the final component of the electron transport chain, is directly involved in electron flow. Decreased complex IV activity has been reported in patients with Alzheimer’s disease [6]. Interestingly, reducing complex IV activity in the absence of surfeit locus protein 1, a key assembly protein, has been shown to significantly increase lifespan in mouse models [98]. One of the primary aims of MT is to enhance or restore ATP production in recipient cells, thereby improving energy supply [28]. Protein synthesis and cellular growth rely heavily on mitochondrial ATP generation [93]. Notably, our findings indicated that ATP levels were consistent across the different muscle sources.

Our previous studies have demonstrated that MT exhibits promising therapeutic potential in mitigating neuroinflammation. Among rats with traumatic spinal cord injury, the intraparenchymal administration of 100 µg of allogenic mitochondria significantly reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the injured spinal cord [2]. Furthermore, intra-DRG administration of 100 µg of allogenic mitochondria suppressed glial reactivity and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the spinal cords of rats subjected to spinal nerve ligation [3]. In vitro, mitochondrial supplementation effectively reversed capsaicin-induced inflammation, and restored mitochondrial membrane potential in primary DRG neurons [3]. Building on this, we investigated the differences in the anti-inflammatory properties of mitochondria derived from various muscle tissues. Our findings revealed that mitochondria isolated from the RSM and WSM effectively alleviated LPS-induced cell death, and restored mitochondrial membrane potential in PC-12 cultures, indicating their robust protective effects under inflammatory conditions. However, these protective effects were absent in cultures treated with mitochondria from MSM, highlighting tissue-specific differences in mitochondrial functionality and therapeutic potential. Interestingly, despite comparable respiratory chain complex activity and ATP levels between mitochondria from MSM and WSM, only WSM-derived mitochondria conferred protection against LPS-induced damage. This suggested that their beneficial effects may be mediated by mechanisms beyond mitochondrial respiratory function. Recent studies indicate that mitochondria can release extracellular vesicles, known as mitovesicles, which carry mitochondrial components involved in inflammation-related processes [99, 100, 101]. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the unique protective effects of WSM-derived mitochondria against LPS-induced damage beyond their role in oxidative phosphorylation. Collectively, these results suggest that the RSM and WSM are promising donor tissues for anti-inflammatory applications, potentially due to their unique mitochondrial profiles. Moreover, notably, our study also revealed a dual effect of allogenic mitochondrial supplementation. While RSM- and WSM-derived mitochondria demonstrated clear benefits in LPS-treated cultures, supplementation with mitochondria from the soleus, rectus abdominis, and biceps brachii muscles unexpectedly caused a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in LPS-untreated PC-12 cultures. This paradoxical finding indicates that the impact of allogenic mitochondria may vary depending on the baseline inflammatory state of recipient cells. Such variability underscores the complexity of mitochondrial transplantation as a therapeutic approach, as the benefits of supplementation may not be universal and could differ based on the cellular or tissue environment. Overall, these findings highlight several critical considerations for future clinical applications of MT. First, selecting the appropriate donor tissue may be essential to maximizing therapeutic efficacy. Second, understanding the recipient cell state—particularly whether inflammatory processes are present—will be pivotal in predicting the outcome of mitochondrial supplementation. Finally, further research is required to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these tissue-specific and inflammation-dependent effects, as this knowledge could inform strategies to optimize MT protocols for various clinical scenarios.

While this study characterized the functional properties of mitochondria isolated from different muscle sources, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although our preliminary results indicated that the protein content of isolated mitochondria was comparable across different sources (data not shown), we cannot rule out the possibility that variations in mitochondrial complex activities may be due to differences in their expression levels. Second, based on prior findings that transplanted allogenic mitochondria can mitigate inflammation in animals with traumatic neural injuries, this study focused on comparing the effects of mitochondria from different skeletal muscle types on LPS-induced changes in PC-12 neuronal cells. Since LPS-induced inflammatory responses in vivo are primarily mediated by immune-associated glial cells, such as microglia and astrocytes, we specifically examined LPS effects on cell viability and mitochondrial membrane potential in a neuron-only culture system. However, we recognize the need for further investigations into how mitochondria from different skeletal muscle types influence LPS-induced inflammatory responses in animal models. Lastly, we did not examine the structural differences between mitochondria from different sources. Notably, the folds of the mitochondrial inner membrane, known as cristae, house the electron transfer chain complexes responsible for establishing the proton motive force necessary for ATP production. ATP synthase flux is diffusion-limited and influenced by cristae shape and size, with lamellar cristae exhibiting 30–80% higher ATP output than tubular cristae. Future research is needed to explore the internal mitochondrial factors underlying these structural and functional differences among various sources. These limitations should be taken into consideration when interpreting our findings.

This study highlights the critical influence of mitochondrial source on the efficacy of MT in addressing cellular dysfunction and inflammation. Among the different muscle types examined, RSM emerges as the most promising donor tissue, characterized by its smaller mitochondrial size, higher mitochondrial content, and superior complex I activity. These features likely contribute to its more significant protective effects against LPS-induced cell death and mitochondrial membrane potential disruption in PC-12 neuronal cells. While mitochondria from the WSM also demonstrated protective properties, those from the MSM did not exhibit comparable benefits, underscoring the functional variability of mitochondria based on their tissue of origin. Our findings provide a foundation for optimizing MT strategies by identifying the most effective mitochondrial sources, with RSM offering distinct advantages for therapeutic applications. Future research should further explore the mechanisms driving these tissue-specific differences and assess their implications in preclinical and clinical models of neurological disorders.

ATP, adenosine triphosphate; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MSM, mixed skeletal muscle; MT, mitochondrial transplantation; NTA, nanoparticle tracking analysis; RSM, red skeletal muscle; WSM, white skeletal muscle.

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in the present manuscript. Additional data can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

JSL supervised and coordinated the project. DWH and HJH conceived the project and experiments. JSL, DWH, HJH, PWC, CEW, HFC designed and performed the experiments. PWC, CEW, CCH, PHL, MTW, HFC analyzed and interpreted the data. DWH, HJH, PWC, CEW and JSL wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of National Cheng Kung University in Tainan, Taiwan (IACUC approval number: 113033). All surgical interventions, perioperative care, and treatments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institute of Animal Use and Care Committee at National Cheng Kung University.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance and instruction provided by Dr. Sheng-Feng Tsai of the Department of Cell Biology and Anatomy, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan.

This work was supported by Tainan Municipal Hospital (Managed by Show Chwan Medical Care Corporation) RD-113010 and Chiayi Christian Hospital R113-032.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL37367.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.