1 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Division of Neuroscience and Clinical Pharmacology, University of Cagliari, 09142 Cagliari, Italy

2 Department of Neuroscience, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC 20057, USA

3 ExplorePharma s.r.l., Parco Scientifico e Tecnologico della Sardegna, Località Piscinamanna, 09010 Cagliari, Italy

Abstract

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), a bioactive lipid molecule, has been identified as a critical regulator of several cellular processes in the central nervous system, with significant impacts on neuronal function, synaptic plasticity, and neuroinflammatory responses. While Alzheimer’s disease, Multiple Sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease have garnered considerable attention due to their incidence and socioeconomic significance, many additional neurological illnesses remain unclear in terms of underlying pathophysiology and prospective treatment targets. This review synthesizes evidence linking LPA’s function in neurological diseases such as traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, cerebellar ataxia, cerebral ischemia, seizures, Huntington’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, autism, migraine, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated complications Despite recent advances, the specific mechanisms underlying LPA’s actions in various neurological disorders remain unknown, and further research is needed to understand the distinct roles of LPA across multiple disease conditions, as well as to investigate the therapeutic potential of targeting LPA receptors in these pathologies. The purpose of this review is to highlight the multiple functions of LPA in the aforementioned neurological diseases, which frequently share the same poor prognosis due to a scarcity of truly effective therapies, while also evaluating the role of LPA, its receptors, and signaling as promising actors for the development of alternative therapeutic strategies to those proposed today.

Keywords

- neurological diseases

- lysophosphatidic acid

- traumatic brain injury

- spinal cord injury

- cerebral ischemia

- seizures

- Huntington’s disease

- autism

- amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- HIV

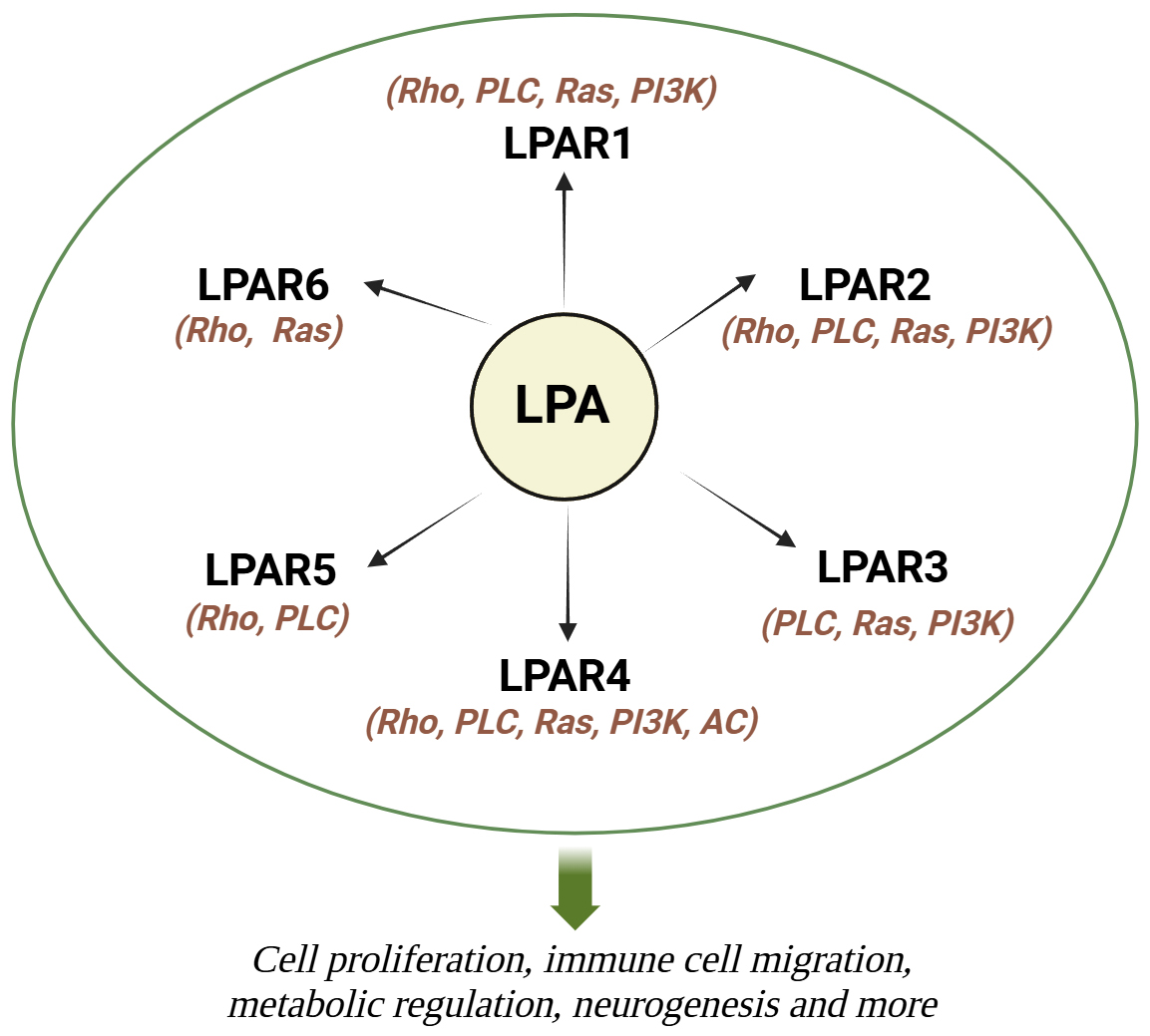

Neurological diseases encompass a broad spectrum of disorders affecting the central and peripheral nervous systems, leading to significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), neurological disorders are estimated to affect over a billion individuals globally, with an increasing burden due to aging populations and environmental conditions [1]. Various factors, including genetic predisposition, pollution, radiation exposure, antioxidants, and dietary habits, contribute to the rising incidence of neurological pathologies across different age groups [2, 3, 4]. The role of diet and lipid metabolism in neurological health has garnered increasing attention in recent years. Lipids, essential components of cell membranes and signaling molecules, play crucial roles in maintaining neuronal structure and function [5]. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism has been implicated in various neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), multiple sclerosis (MS), epilepsy, and many more [6, 7, 8]. Of particular interest is lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), a bioactive lipid with diverse physiological functions in the nervous system. LPA exerts its effects through interaction with specific G protein-coupled receptors, including LPA receptors 1–6 [9, 10]. Specifically, lysophosphatidic acid receptor (LPAR)1 is key in neuropathic pain, alveolar development, intestinal epithelial cell proliferation, bone mineralization, and vascular remodeling [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. LPAR2 plays protective roles in intestinal health, stroke recovery, and immune cell migration while regulating exploratory behaviors post-fasting [17, 18, 19, 20]. LPAR3 contributes to reproduction and neuropathic pain [21, 22], and LPAR4 and LPAR6 are critical for vascular development and metabolic regulation [23, 24, 25]. LPAR5 is involved in T-cell inhibition and gut homeostasis and LPAR6 influences oligodendrocyte development [26, 27, 28]. These findings highlight LPA’s extensive impact on physiological and pathological processes, with potential therapeutic implications. For instance, LPA’s promotion of cortical neuronal progenitor commitment through LPAR1 during cortical neurogenesis highlights its critical developmental functions [29]. Additionally, LPA influences cytoskeletal dynamics and neurite retraction, which is essential for neuronal morphology and motility [30, 31]. Beyond neurons, LPA modulates astrocyte proliferation, cytokine expression, and neuroinflammation, facilitating neuron-astrocyte crosstalk and impacting processes like axonal growth and differentiation [32]. Similarly, microglia respond to LPA through receptor-mediated calcium signaling, chemokinesis, and morphological changes, underscoring its broader influence in central nervous system (CNS) cell interactions [31] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Summary of cellular and molecular mechanisms of LPA. LPA works by activating 6 transmembrane G-coupled protein receptors (LPAR1-6), which in turn trigger many signaling pathways by activating various G proteins.LPA, lysophosphatidic acid; LPAR, lysophosphatidic acid receptor; Rho, Rho-kinase; PLC, phospholipase C; Ras, Ras kinase; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; AC, adenylyl cyclase. Created with Biorender.com.

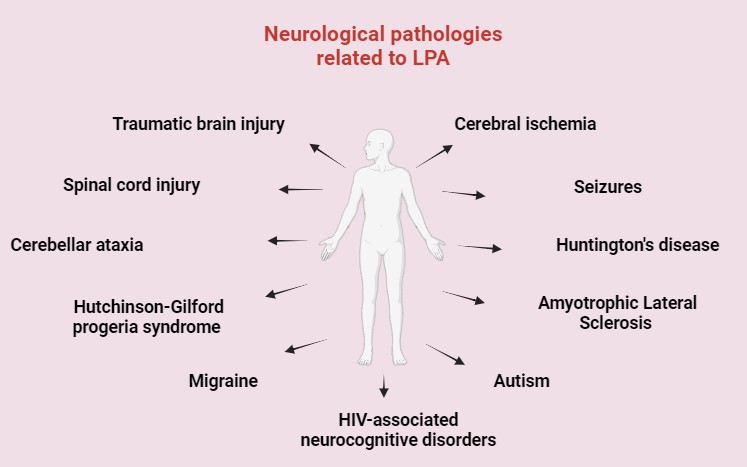

Merging evidence suggests that dysregulation of LPA signaling contributes to the pathogenesis of neurological diseases by modulating neuroinflammatory responses, neuronal survival, and synaptic plasticity [8, 33, 34, 35]. This review intends to illustrate the implication of LPA in the pathogenesis of various neurological diseases, such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), spinal cord injury (SCI), cerebellar ataxia (CA), cerebral ischemia, seizures, Huntington’s disease (HD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), autism spectrum disorders (ASD), migraine and in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated neurocognitive disorders, which frequently share the same poor prognosis and a lack of effective treatment options, while additionally assessing the role of LPA, its receptors, and signaling as potential actors for the establishment of alternative therapeutic strategies to those proposed today (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. General overview of LPA-related neurological disorders. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus. Created with Biorender.com.

TBI is a major public health problem worldwide, with millions of cases recorded each year. It is frequently caused by a variety of circumstances, such as falls, car accidents, sports injuries, violence, and many more, where the collision to the head causes a variety of deficits, depending on the location and degree of the lesion. TBIs are classified according to their severity as mild, moderate, or severe. Children, teenagers, and the elderly are more prone to TBIs [36]. It was estimated that roughly 2.87 million TBI-related emergencies occurred in 2012 each year in the United States [33, 36]. The probability of survival after TBI ranges according to the extent of the patient’s age, the damage, and the timing of medical care. While moderate TBIs have an improved outcome, severe TBIs increase the chance of death and long-term impairment. Based on recent data, around 69,000 TBI-related fatalities occurred in the United States in 2021 [37].

LPA has recently been discovered as a possible mediator of subsequent brain damage after TBI. Elevated levels of LPA in the brain were identified following TBI, contributing to neuronal injury, neuroinflammation, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption [38]. LPA signaling has also been linked to the control of synaptic plasticity and neurodegeneration, indicating its potential relevance in the rehabilitation phase post-TBI [39]. It was shown that LPA levels raised considerably in cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) from TBI individuals and mice exposed to control cortical impact (CCI) injuries. These high levels promoted secondary injury processes such as neural inflammation and cell death determining BBB disruption that all participated in aggravating the damage produced by the initial trauma [38]. Moreover, brain tissue samples showed reduced levels of markers of inflammation and cytokines, with consequent lower neuroinflammatory response, and tissue damage following TBI [38].

LPAs were also investigated as biomarkers for blast-induced traumatic brain injury (bTBI). Samples of CSF were obtained from rats exposed to single or repeated blasts and analyzed for various LPA species using mass spectrometry, revealing significantly higher levels of LPAs in the CSF. LPA levels in the CSF, but not the plasma, were shown to be correlated with the extent of injury and neurological impairments in rats, related to greater damage and poor clinical outcomes, indicating that LPAs might be useful as predictive indicators in bTBI. Longitudinal studies demonstrated variable differences in LPA levels after bTBI. The highest LPA levels were detected immediately after injury, followed by a slow fall during the next few days to weeks. This time course showed that in CSF the LPA levels might represent the acute and subacute stages of bTBI pathophysiology, and LPA levels might be good indicators of the severity of the injury [40] (Table 1, Ref. [38, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53]).

| Disorder | LPA system alterations | References |

| Traumatic brain injury | [38] | |

| [40] | ||

| [41] | ||

| Spinal cord injury | [42, 44] | |

| [43] | ||

| Cerebral ischemia | [45] | |

| [46] | ||

| Seizures | [52] | |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | [47, 48] | |

| Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome | [50, 51] | |

| Autism | [49] | |

| HIV | [53] |

CSF, cerebral spinal fluid; CCI, control cortical impact; TBI, traumatic brain injury; bTBI, blast-induced traumatic brain injury; SCI, spinal cord injury; tMCAO, transient middle cerebral artery occlusion.

Other studies examined the changes in LPA distribution following TBI utilizing matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) methods in brain samples of rats with TBI. MALDI mapping indicated substantial alterations in the spatial distribution of LPAs in the brain after TBI. Specifically, at 3 hours after damage, increased intracellular LPA expression was related to neuronal degeneration; hence, alterations in LPA signaling after TBI outside of hemorrhagic zones may also contribute to neuronal death. MALDI examination of the thalamus revealed a considerable rise in the distribution of the intracellular precursor of LPA, phosphatidic acid (PA) 18:0/18:1, one hour after damage. This was followed by an increase in neuronal degeneration 3 hours following the damage. The current investigation found that bioactive LPA isoforms 18:1 and 20:1 were more efficiently metabolized in damaged cortical gray matter, but saturated species levels remained constant. The increased expression of unsaturated LPA is most likely due to blood coagulation near the damaged epicenter. The corpus callosum analysis revealed that, while there were no general white matter differences in LPA levels, there was a positive connection between LPA 20:1 and axonal injury sites, indicating that LPA may be an indication of damage to axonal cells post-TBI. These findings support LPA as an initial signaling component responsible for contributing to the pathophysiology of TBI, not just in hemorrhagic areas, but throughout the brain, particularly in white matter areas [41] (Table 1).

Several studies have investigated numerous tactics for modulating LPA transmission in TBI, such as the use of pharmaceutical agents that target LPA receptors and enzymes that participate in LPA synthesis and metabolism [38, 54, 55]. These investigations have demonstrated encouraging results in reducing neuroinflammation, maintaining neuronal integrity, and enhancing performance in animal models of TBI [38]. The use of anti-LPA antibodies has shown tremendous efficiency towards TBI-related damage. In fact, inhibiting LPA with the murine anti-LPA mAb, B3, improved brain function in CCI mice providing the first indication that therapeutic anti-LPA antibodies could be effective in treating TBI-associated secondary damage [38]. Indeed, the animals treated with anti-LPA antibodies increased their cognitive performance compared to the control-treated mice and behavioral assessments suggested greater recovery. In addition, anti-LPA antibody therapy maintained the health of neurons and decreased neuronal damage in the interested areas. This shows that anti-LPA antibodies protect neurons from injury and death. Immunohistochemical investigations revealed that mice treated with anti-LPA antibodies had higher levels of indicators linked with neurodegeneration and synaptic plasticity. This shows that anti-LPA antibodies may play a role in aiding healing and rehabilitation after TBI. These experimental results provide strong proof for anti-LPA antibodies’ beneficial effects for enhancing endpoints after a traumatic brain injury. Anti-LPA antibodies, which target LPA signaling pathways, offer a potential method to reduce secondary damage mechanisms while promoting neural protection and recovery in TBI [38]. The effectiveness of these antibodies was further investigated in relieving post-TBI neuropathic pain using Sprague-Dawley rats that had undergone controlled cortical impact damage to generate TBI. Upon damage induction, animals were monitored for the onset of neuropathic pain responses such as mechanical allodynia and temperature hyperalgesia. Rats were then given either anti-LPA antibodies or a control therapy. Animals treated with anti-LPA antibodies demonstrated a substantial decrease in neuropathic pain behaviors when compared to control animals, with mechanical allodynia alleviated in the treated group and thermal withdrawal latencies significantly prolonged [54]. Another study revealed that the treatment with the anti-LPA antibody B3/Lpathomab successfully reduced the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-

SCI is a severe medical disorder caused by trauma or damage to the spinal cord, resulting in variable degrees of mainly motor and sensory impairment. The spinal cord, a critical component of the CNS, acts as a route for neural impulses throughout the brain and every part of the body, allowing movement, sensation, and coordination. When the spinal cord is injured, changes in these neuronal pathways can result in severe and sometimes permanent deficits in motor function, sensation, and physiological functions below the level of damage.

In the last few years, LPA has emerged as an important component in the pathogenesis of spinal SCI. Elevated levels of LPA after SCI correspond with the severity of the damage, indicating its participation in pathological processes. The major player involved seems to be the LPAR1 which has a variety of negative consequences in SCI [42] (Table 1). LPAR1 activation exacerbates neuroinflammation by increasing the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [56]. Furthermore, LPAR1 activation has been linked to neuronal death and inhibits axonal regeneration, limiting functional recovery after SCI [57]. It was discovered that LPA levels rise following a SCI, and this rise is related to the severity of the lesion. The LPAR1 is hypothesized to trigger a range of physiological reactions, including not only the stated inflammation, but also promotes glial scar formation, neuronal death, and slows axonal regeneration, all of which are critical in SCI, limiting functional recovery (Table 1). LPAR1 activation is implicated in promoting neuronal apoptosis [58] and inhibiting axonal regeneration [59] crucial processes for functional recovery following SCI.

Besides LPAR1, LPAR2 was also shown to contribute to myelin loss and secondary damage following SCI. A study conducted in mice revealed that the expression and activation of LPAR2 is increased following contusion damage, at least partially via microglia. Furthermore, the demyelinated lesion caused by an intraspinal injection of LPA into the undamaged spinal cord was decreased in the absence of LPAR2. Mice missing LPAR2 had enhanced motor abilities and myelin sparing following SCI. In vitro cell culture experiments showed that LPAR2 activation of microglia resulted in oligodendrocyte cell death and the cytotoxic effects of the microglial LPA-LPAR2 axis were caused by purine release by microglia and receptor activation P2X7 affects oligodendrocytes. This work sheds fresh light on the involvement of LPAR2 in SCI [43] (Table 1).

As previously highlighted, studies have shifted towards focusing on the critical role of LPAR1 and LPAR2 in SCI pathology. Inhibiting these receptors holds promise in reducing inflammation, neuronal loss, and promoting functional recovery, paving the way for targeted therapies to enhance SCI outcomes. Experimental findings showed that inhibiting LPAR1 might ameliorate the negative consequences of SCI, providing a possible treatment path. Understanding the processes that underpin LPAR1 activation and its downstream consequences gives important insights for creating targeted therapies to improve outcomes for people with SCI [44]. The discovery of LPAR1 as a major mediator in SCI pathophysiology opens up possibilities for targeted treatment therapies and the use of LPAR1 antagonist receptors showed promising results as a therapy option for SCI’s consequences, including inflammation, neuronal loss, and delayed regeneration [43]. Further evidence of the involvement of LPAR2 in the consequences of SCI was given by a study in which UCM-14216, a new LPAR2 antagonist, administered to mice with SCI, successfully reduced the severity of the damage and improved the recovery of the functions. This study confirms the LPAR2 therapeutic potential of drugs targeting LPA receptors for improving spinal cord injury-induced pathology and increasing recovery [60].

CA is a neurological condition characterized by a loss of coordination, uneven walking, and difficulty with speech and eye movements caused by an injury to the cerebellum, the brain’s motor control center [61].

New studies show a relationship between CA and LPA signaling [62, 63]. Lipidomic studies revealed that alterations in genes regulating lipogenesis and lipolysis may alter lipid composition such as phospholipids, sphingolipids, and cholesterol levels, and contribute to the onset of hereditary CA and other ataxic disorders through the dysregulation of mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, and neuronal survival. Understanding the role of lipid dysregulation in disease etiology may provide new treatment strategies for these devastating neurodegenerative illnesses [62]. Recently, researchers investigated the link between a homozygous mutation in the DDHD2 gene, which is involved in the production of a phospholipase, and the development of late-onset spastic ataxia. This mutation was shown to be correlated with a significant decrease in the activity of phospholipase A1 and, consequently, of LPA production, suggesting that a main mutation involved in the onset of CA is directly linked to LPA signaling and metabolism [63].

Cerebral ischemia is a prominent cause of death and morbidity globally, frequently resulting in devastating neurological impairments, and is distinguished by insufficient blood flow to the brain [64]. The most prevalent kind of cerebral ischemia is ischemic stroke, which accounts for roughly 80% of all strokes worldwide, with considerable differences in incidence and prevalence across demographic and geographic locations. It happens when a cerebral artery gets clogged, triggering a series of events that include energy failure, excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, inflammation, and, eventually, neuronal cell death [65, 66, 67]. The study of cerebral ischemia has benefited from a variety of experimental models, such as transient or permanent occlusion of cerebral blood vessels in animal models, in vitro ischemia-reperfusion models, and advances in neuroimaging techniques for assessing cerebral perfusion and metabolism in humans. In addition, accumulating data shows that cerebral ischemia is more than just a localized phenomenon; it also involves extensive changes in neuronal connections and network dynamics, which contribute to cognitive impairment and other long-term effects [68].

LPAR1 might be an important target for cerebral ischemia, due to its ability to evoke microglial activation. In a recent study, researchers used a mouse model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) to evaluate the contribution of LPAR1 to ischemic damage. LPAR1 was shown to be implicated in brain infarction and neurological deficits, as well as neuroinflammation and microglial activation [69]. Other LPA receptors were also investigated in cerebral ischemia. To unravel the involvement of LPAR5 in the pathogenesis of cerebral ischemia, LPAR5 expression was characterized in the brains of mice exposed to tMCAO to model cerebral ischemia. Immunohistochemical research showed that LPAR5 expression was upregulated in the ischemic area, particularly in microglia, which was correlated with increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-

Modulating the LPA system, particularly through antagonizing its receptors, has emerged as a promising strategy for reducing cerebral ischemic damage by regulating key factors in ischemia such as neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis. The antagonization of LPAR1 both through treatment with AM095, an LPAR1 antagonist, and a specific LPAR1 shRNA lentivirus, led to reduced neurological deficits and brain infarction, as well as microglial activation and production of proinflammatory cytokines, NF-

HD is a progressive neurodegenerative ailment marked by physical impairment, cognitive decline, and mental symptoms. It is triggered by a genetic mutation in the huntingtin (HTT) gene, which produces a mutant huntingtin protein (mHTT) [73]. Deposition of mHTT in neurons causes neuronal malfunction, atrophy, and eventually cell death, particularly in areas of the brain important in motor control and cognition. HD usually appears in mid-adulthood, with symptoms deteriorating over time and resulting in substantial impairment and untimely mortality.

Recent research has found differences in LPA levels and LPA receptor expression in the brains of HD patients and animal models of illness [74]. LPA signaling has also been demonstrated to affect the pathophysiology of HD by regulating neuroinflammation, excitotoxicity, and synaptic function. Targeting the LPA signaling system might be a promising therapeutic method for reducing neuronal damage and cognitive impairment in HD [57]. So far, few very recent publications focused on LPA involvement in HD. The knock-in Q140/Q140 rodent model, which mimics essential aspects of HD, was used for lipid extraction with liquid chromatography combined with simultaneous mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to measure glycerophospholipid constituents. Glycerophospholipid profiles differed significantly between HD and wild-type mouse brains. PA and LPA were shown to be dysregulated in the brains of HD mice when compared with controls [74]. Since PA is a precursor of LPA, the reduction of PA synthesis that is observed in these animals could underlie the increase seen in LPA species, therefore indicating that lipid signaling, metabolism, and cellular homeostasis disruptions could be linked with Huntington’s disease pathology [74]. The function of sphingolipids was also evaluated in the etiology of HD and how they affect cellular reactions to hypoxic stress, examining how dysregulated sphingolipid metabolism causes neuronal dysfunction and vulnerability in HD. It was shown that some sphingolipid species, such sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a bioactive lipid similar to LPA, and ceramide, had abnormal regulation in HD and altered cellular reactions after hypoxic stress. Irregular sphingolipid signaling pathways lead to oxidative stress, inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, worsening neurons’ sensitivity to hypoxic insults in HD [75].

The function of gintonin in neurological dysfunction and striatal cytotoxicity through the modulation of LPA signaling was examined in an HD mice model produced by 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NPA). The pretreatment with gintonin of animals treated with 3-NPA, an irreversible inhibitor of complex II in the mitochondria, to model HD ameliorated the outcome by blocking mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, and microglia activation due to the activation of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)-Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathways and up-regulation of LPA in the striatum. The beneficial effects of gintonin were annulled by antagonizing LPAR1-3 using Ki16425, corroborating the importance of the LPA system for brain functioning. It was additionally looked into the beneficial effect of gintonin (GT) in STHdh cells, an in vitro model of HD, and an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector-infected mouse model of HD, with the positive effect of gintonin demonstrated by the inhibition of formation of mutant HTT aggregates and reduced cell death. Probably, gintonin could be evaluated as a novel future therapeutic agent for HD by activating Keap1-Nrf2 signaling through the LPA signaling pathway [76].

ALS, sometimes known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a degenerative neurological disease marked by a slow decline and destruction of motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord. This deadly ailment causes gradual muscular weakening, paralysis, and, eventually, respiratory failure, usually ending in death within a few years after the symptoms start. Because of its devastating effect and complicated genesis, ALS has sparked widespread interest in both the medical and scientific sectors. While the exact origin of ALS remains unknown, recent research reveals a complex interaction of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle variables. Approximately 5–10% of ALS cases are inherited, with the remainder being sporadic, showing a complicated genetic contribution along with environmental effects [77]. The prevalence of ALS differs widely, with greater rates recorded in some areas. Typically, ALS affects 1 to 2 persons per hundred thousand globally each year, with modest variances among individuals [78]. While ALS can develop at any age, it primarily affects persons between the ages of 40 to 70, with the typical age of manifestation at 55 years [79]. The cause of ALS is an intricate connection of numerous molecular processes, comprising excitability, oxidative stress, dysfunction in the mitochondria, decreased axonal transport, and neuroinflammation [80]. These mechanisms lead to the gradual degradation of motor neurons, which leads to the loss of muscular function seen in ALS patients. Recent discoveries in neurobiology have emphasized the probable significance of LPA in ALS etiology. Altered LPA signaling has been linked to neuroinflammatory reactions, axonal decay, and neuronal death, indicating its possible role in ALS pathophysiology [81].

LPA binding to LPAR1 regulates a variety of cellular functions associated with ALS pathogenesis. The therapeutic potential of targeting LPA receptor LPAR1 signaling was investigated using superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1)-G93A transgenic mice, a well-established ALS animal model. SOD1-G93A transgenic mice received therapy with the LPAR1 antagonist AM095 at early disease phases, and the progression of the disease was evaluated as delayed disease development in SOD1-G93A mice compared to controls, revealing preserved motor neurons and reduced glial inflammation, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress, indicating attenuated disease pathology. These findings imply that LPA-mediated pathways play a role in ALS pathogenesis and give a basis for additional research into LPA receptor antagonists as possible ALS therapeutics [47] (Table 1). On the other hand, gintonin was proven to be effective in ameliorating the symptoms, preventing motor dysfunction, and increasing survival in SOD1-G93A mice, suggesting that the role of LPA-LPAR1/3 signaling in ALS needs to be further investigated [82]. Using the same transgenic animal paradigm deficient in LPAR2, the influence of LPAR2 on ALS evolution was evaluated, as LPAR2 mRNA levels were found to be elevated in post-mortem spinal cord samples from ALS patients [48]. LPAR2 gene deletion enhanced microglial activation but did not cause demyelination or degeneration of motor axons, protecting against muscular atrophy. The deletion of the LPAR2 decreased macrophage infiltration into the skeletal muscle in transgenic mice, connecting LPAR2 signaling to muscle inflammation and atrophy in ALS demonstrating for the first time that LPAR2 might contribute to ALS, and that its genetic deletion has protective effects. More research into the underlying mechanisms of LPAR2-mediated neuroprotection is needed [48] (Table 1).

ASD is a diverse collection of neurodevelopmental conditions distinguished by impaired social communication, repetitive behaviors, and limited interests. With an estimated frequency of 1 in 54 children in the United States [83], ASD places a considerable burden on affected people and society. ASD’s etiology is complicated, with intricate relationships involving predisposition to the disorder, variables in the environment, and abnormal neurodevelopmental mechanisms. Numerous susceptibility genes and chromosomal anomalies have been linked to ASD, including changes in synaptic function, neural connection, and neurotransmitter signaling [84]. Furthermore, prenatal and postnatal variables such as maternal illness, exposure to environmental chemicals, and maternal metabolic abnormalities increase the chance of ASD [85].

Emerging data points to a possible relationship between LPA imbalance and ASD pathogenesis. Children with ASD exhibit altered levels of LPA, indicating that LPA may have a role in modifying synaptic function, neuronal connection, and neuroinflammatory processes involved in ASD etiology [86]. A case-control study was conducted to explore immunological abnormalities during mid-gestation in women of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The focus was on the potential relationship to LPA signaling, which gave insight into the immunological changes associated with ASD and their possible link to LPA dysregulation. The study evaluated maternal levels of cytokines in mid-gestation across women who had kids with ASD and typical controls. The investigation discovered that mothers of children with ASD had substantially higher levels of interferon (IFN)-

High-throughput mass spectrometry and chromatography technologies found unique metabolic characteristics in people with ASD in comparison to controls, as evidenced by changes in numerous metabolite types such as amino acids, lipids, and organic acids. The researchers used bioinformatics and statistical modeling to discover particular metabolites with variable abundance in ASD samples [49] (Table 1). In particular, changes of LPA 18:2 levels were detected in blood samples from children with ASD, which was considered as a predictor of the disease [85]. Altered LPA signaling may affect neuronal growth, synaptic activity, and neuroinflammatory responses, all of which have been linked to ASD etiology. Furthermore, altered LPA metabolism could lead to neurological abnormalities, interpersonal challenges, and intellectual disabilities seen in ASD phenotypes. Additional study is needed to assess the safety and effectiveness of LPA-targeted future treatments in clinical trials for ASD patients.

HGPS is a rare genetic condition that results in accelerated aging caused by mutations in the LMNA gene, which encodes the lamin A protein. Patients with HGPS show signs of premature aging, such as vascular dysfunction, hair loss, and skin abnormalities, and oxidative stress is thought to play a role in disease progression [88]. Based on the oxidative stress and aging theory, as well as how the increase in LPA signaling can protect against cell damage induced by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [88], investigating the LPA system and its implication in the premature aging process of HGPS could provide valuable pathological and therapeutic insights into premature cellular senescence.

At the end of the 90’s, the involvement of LPAR3 in reducing oxidative stress and cellular senescence in HGPS was investigated. Using HGPS-specific cellular models, scientists show that LPAR3 activation reduces oxidative stress and aging characteristics. LPAR3 activation increases antioxidant mechanisms of defense, improves mitochondrial activity, and suppresses DNA damage and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in HGPS cells [50] (Table 1). Moreover, the same authors confirmed the ability of LPAR3 signaling to reduce oxidative stress through the complex regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis [51] (Table 1). The findings imply that targeting LPAR3 signaling pathways might be a promising treatment method for reducing cellular senescence and premature aging in HGPS. Activation of LPAR3 shows promise for combating oxidative stress and preserving cellular function in HGPS and perhaps other age-related diseases (Table 1).

Seizures are a sign of aberrant synchronous neuronal activity in the brain, which causes a variety of clinical symptoms and behaviors [89]. It is a prevalent neurological condition that affects people of all ages, with a global prevalence of around 1% [90, 91]. Seizures can occur as single episodes or as part of a recurring pattern known as epilepsy, which affects approximately 70 million individuals worldwide [92]. Understanding the processes that cause epileptic seizures is critical for accurate diagnosis, efficient treatment, and better quality of life for people affected. Disruptions in ion channels, neurotransmitter systems, and neural networks all play important roles in seizure production and propagation [93]. Genetic investigations have found various mutations in ion channels, neurotransmitter receptors, and synaptic proteins related to epilepsy syndromes, underscoring the disorder’s genetic variability [94]. Environmental factors such as head trauma, stroke, brain infections, and developmental anomalies can all raise the risk of seizures by interfering with normal brain function and circuits. Advanced neuroimaging methods give useful information on the anatomical and functional abnormalities that cause epileptic seizures, assisting in the localization of epileptogenic lesions and directing surgical procedures where necessary [95]. Pharmacological treatments, nutritional therapy, neuromodulation methods, and surgical procedures are all used to manage seizures and epilepsy, and they are adapted to the needs of each patient [96]. Despite optimum medical treatment, a considerable minority of patients continue to suffer uncontrolled seizures, emphasizing the need for alternative therapeutic options and continuous research efforts.

The LPAR1 expression in the hippocampus after seizure induction was studied. Immunohistochemical research demonstrates that LPAR1 is upregulated particularly in reactive neural stem cells (NSCs) in the hippocampus neurogenic niche. This suggests that LPAR1 may be involved in the identification of seizure-induced activation of NSCs. Knockout mice missing LPAR1 in NSCs were treated to induce seizure and the loss of LPAR1 caused altered differentiation dynamics and proliferation of NSCs, emphasizing its regulatory function in NSCs behavior. Modulation of LPAR1 activity modifies seizure susceptibility and severity, implying that LPAR1-mediated control of NSCs plays a role in the pathophysiology of epileptic seizures determining the function of LPAR1 in identifying and modulating the organization of seizure-induced reactive NSCs in the hippocampus. LPAR1 appears as a significant molecular indicator and modulator of NSC behavior in the context of seizures, providing prospective avenues for therapy for controlling epileptogenesis and boosting neurogenesis in epileptic circumstances [52] (Table 1). In addition, when investigating epilepsy, a study has found that the genetic deletion of the Plasticity Related Gene-1 (PRG-1), a membrane protein related to lipid phosphate phosphatases, can lead to epileptic seizures [97]. This outcome was directly linked to LPA. PRG-1 can interact with LPA by controlling its levels at the synaptic level by nonenzymatic mechanisms. LPAR2 knockout animal model further confirmed that LPA-LPAR2 interaction is implicated in hyperexcitability while PRG-1 acts to counteract it [97]. This emphasizes that LPA-LPAR2 interaction is involved in the regulation of excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus, implying that the disruption of this pathway can result in hyperexcitability and seizures.

On the other hand, gintonin’s regulatory effect on LPA signaling and its potential to mitigate excitotoxicity-induced neuronal damage and inflammation were investigated by using a mouse model of kainic acid-induced seizures. Gintonin was delivered to mice by intraperitoneal methods, followed by behavioral evaluations, histological investigations, and biochemical assays to determine its impact on seizure outcomes and neuronal survival. The results show that gintonin pretreatment significantly lowers seizure frequency, duration, and severity in kainic acid-treated rats in comparison with untreated controls. Gintonin treatment reduces neuronal cell death and preserves hippocampus structure, indicating neuroprotective properties against excitotoxicity-induced neuronal damage. As gintonin is a specific ligand for LPA receptors, the work sheds light on the role of LPA receptors in mediating its neuroprotective properties. Experimental inhibition of LPA receptors reduces the therapeutic effects of gintonin, emphasizing the relevance of the stimulation of LPA receptors 1 and 3 in regulating its neuroprotective properties. Gintonin suppresses the activity of microglial cells, reduces inflammatory mediators, and cytokine production, and inhibits NF-

Migraine is one of the most common neurological diseases globally, impacting millions of people and causing significant impairment. It is a complicated neurological illness defined by recurring headaches that are frequently accompanied by photophobia nausea, and disorientation [99].

Despite the lack of direct evidence connecting LPA signaling with migraine, several evidence links LPA abnormalities with neuropathic and chronic pain. Indeed, LPA was shown to be involved in the initiation and maintenance of neuropathic pain and also fibromyalgia through demyelination of the dorsal root mediated by LPAR1, an increase in inflammatory mechanisms regulated by LPAR3, and an increase in central LPA production through an overactivation of glial cells [11]. An interesting study revealed that LPA levels in the CSF of patients diagnosed with neuropathic pain were correlated with the intensity and duration of pain. LPA 18:1 and 20:4 in particular were shown to be the most correlated with the symptoms [100].

Moreover, it is important to consider the antagonism of LPAR1/3 as a potential therapeutic approach to treat pain. Indeed, LPAR1/3 antagonists were shown to be effective against chronic pain caused by a variety of occurrences, such as chemotherapy, nerve and spinal cord injury, diabetes, cerebral ischemia, and fibromyalgia caused by cold or several other stressors [101]. Considering the nature of migraine, which is characterized among other symptoms by severe episodes of pain, it could be speculated that LPA signaling might be involved in the onset or worsening of the symptoms. Moreover, migraine is also correlated with neuroinflammation and vascular abnormalities [102, 103], all factors that are known to be regulated by LPA signaling. However, more specific research is needed to provide clear evidence of the involvement of LPA in migraine and develop effective treatments for this strongly debilitating disorder.

HIV is part of the Retroviridae family. It targets CD4+ T cells, leading to a gradual suppression of the immune system, and consequently resulting in immunodeficiency that eventually leads to death due to the increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections [104]. Recent research has highlighted the involvement of LPA in the pathophysiology of HIV, particularly concerning infection and HIV-associated complications.

LPA can significantly influence the survival and function of CD4+ T cells. It has been reported that LPA signaling can lead to apoptosis, or programmed cell death, of CD4+ T cells, contributing to the depletion of these crucial immune cells during HIV infection. This loss of CD4+ T cells is a key factor in the progression of HIV to AIDS [105]. A study by Le Hingrat and colleagues [105] investigated the effects of sustained CD4+ T-cell depletion in the context of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in African green monkeys (AGMs). AGMs are natural hosts for SIV and typically do not progress to AIDS, even with high viral loads [106]. The study found that despite significant depletion of both circulating and mucosal CD4+ T cells, these monkeys did not progress to AIDS, offering valuable insights into the mechanisms of immune resilience. In addition to LPA’s role in immune cell depletion, the HIV-1 trans-activator of transcription (Tat) protein has been recognized for contributing to HIV-induced white matter damage. The viral Tat protein was shown to reduce the lysophospholipase D activity of ATX, leading to decreased LPA synthesis. This reduction in LPA impairs the growth of oligodendrocyte precursor cells and is associated with reduced oligodendrocyte differentiation, which may negatively impact myelination processes. Such disruptions could contribute to the neurological defects observed in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) [106, 107]. Furthermore, before the initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), HIV-infected individuals were found to have higher levels of LPA compared to healthy controls. During the first year of cART, LPA levels remained unchanged even as viral load decreased, and immune function improved. This suggests that while cART is effective in controlling viral replication, it may not fully normalize lipid metabolism, particularly in terms of LPA production and regulation. Consequently, LPA has been proposed as a potential marker of persistent metabolic abnormalities in HIV patients [53] (Table 1). Gaining knowledge about LPA’s function in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration opens up new avenues for research into the mechanisms behind HAND and points to possible treatment options. One intriguing tactic to lessen neuroinflammation and stave off cognitive loss in HIV-positive persons may be to target LPA signaling pathways with therapeutic approaches including the use of LPA receptor antagonists or inhibitors of LPA synthesis to modulate the inflammatory response and preserve neuronal function.

The therapeutic potential of targeting LPA signaling in neurological disorders offers a promising avenue for innovative treatments, yet significant challenges remain to ensure clinical success. Anti-LPA antibodies and receptor antagonists have shown efficacy in preclinical models of TBI, ALS, and seizures by reducing neuroinflammation, promoting neuronal survival, and enhancing recovery outcomes [38, 47, 69, 108]. However, translating these findings into human therapies is complicated by potential off-target effects, as LPA is critical to physiological processes such as vascular integrity and immune regulation, raising concerns about systemic side effects [56]. The heterogeneity of LPA’s roles across disorders further necessitates tailored therapeutic approaches, given its distinct contributions to the pathophysiology of conditions such as cerebral ischemia, migraines, and spinal cord injury [42, 65, 102]. Additionally, pharmacokinetic challenges, such as ensuring effective BBB penetration and avoiding systemic degradation, must be addressed [38, 72]. Compensatory mechanisms in lipid signaling networks may also reduce the long-term efficacy of LPA-targeted interventions, highlighting the need for robust monitoring and biomarker development during clinical trials [81]. Despite these obstacles, advancements in understanding LPA signaling pathways and innovative delivery mechanisms provide a foundation for developing safer and more effective therapies. Addressing these risks and refining disease-specific strategies could transform LPA signaling modulation into a viable therapeutic avenue for diverse neurological conditions [9, 48].

Writing—original draft preparation, SD; Supervision, SD, and VA; Review, editing and substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, SD, VA, MCO, PO. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

All authors declare no conflicts of interest. Although Maria C. Olianas and Pierluigi Onali are employees of ExplorePharma s.r.l., they did not receive sponsorship from ExplorePharma s.r.l., and the judgments in data interpretation and writing were not influenced by this relationship. Given her role as the Guest Editor, Simona Dedoni had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Hongquan Wang.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.