1 Department of Stress, Development and Signaling in Plants, Group of Antioxidants, Free Radicals and Nitric Oxide in Biotechnology, Food and Agriculture, Estación Experimental del Zaidín (Spanish National Research Council, CSIC), 18008 Granada, Spain

Abstract

Plant hydrogen sulfide (H2S) metabolism has garnered noteworthy attention due to its role in regulating many plant processes. The primary mechanism by which H2S exerts its signaling functions is through its reversible interaction with thiol groups on cysteine residues in proteins and peptides. This thiol-based oxidative post-translational modification (oxiPTM) is known as persulfidation. Transcription factors (TFs) are key proteins that control gene expression by interacting with distinguishing DNA sequences and other regulatory proteins. Their function is essential to almost all aspects of cellular biology, including development, differentiation, and responses to environmental biotic and abiotic cues. The persulfidation of TFs has emerged as an additional regulatory mechanism, linking H2S signaling with gene regulation. Although the available information on the crosstalk between the regulatory mechanisms of H2S metabolism and TF activity remains limited, existing data suggest that this connection influences not only H2S metabolism itself but also other metabolic pathways involved in various physiological and stress responses. This review provides an updated overview of an emerging research area, focusing on the mutual regulation between specific TFs and H2S metabolism, particularly in response to adverse environmental conditions.

Keywords

- hydrogen sulfide

- oxiPTM

- persulfidation

- transcription factors

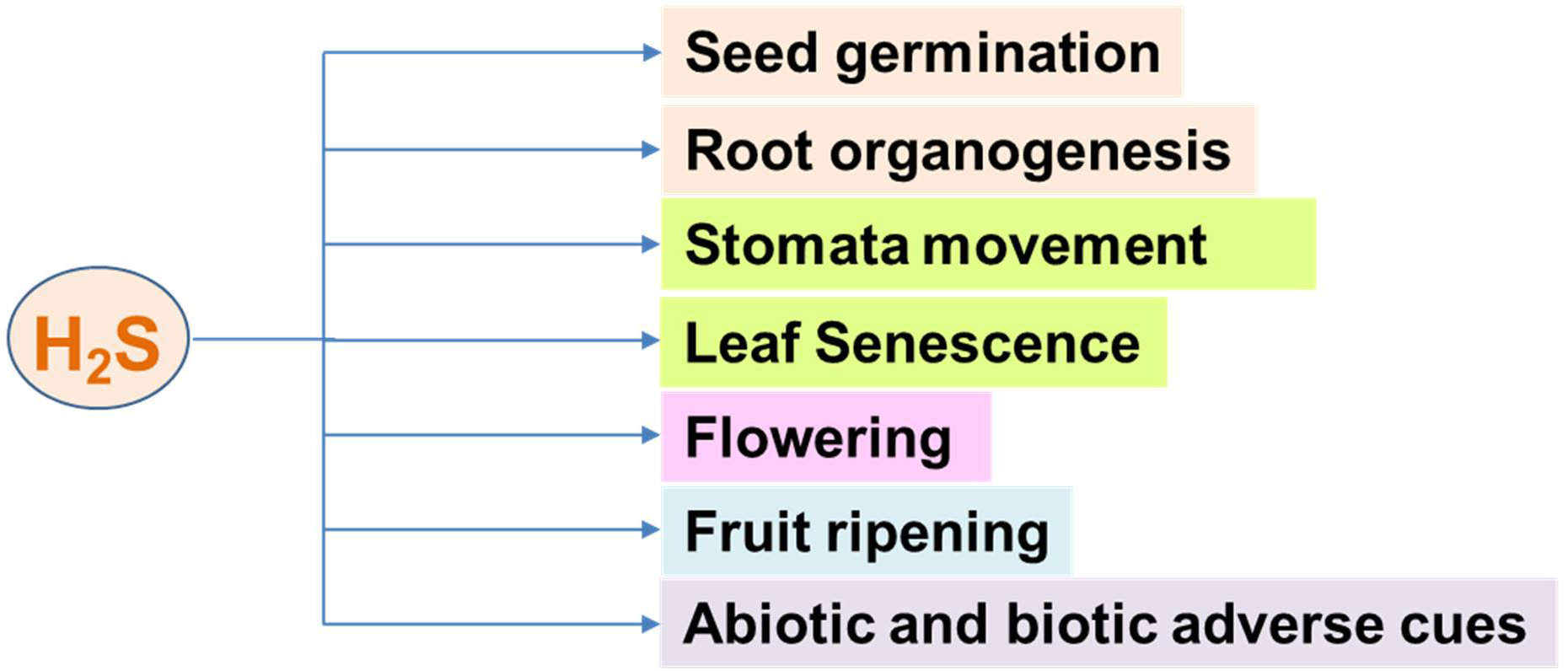

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) was initially regarded as a toxic gas, primarily due to its characteristic odor of rotten eggs and its well-documented harmful effects at high concentrations [1]. It was considered dangerous to all living organisms, capable of inhibiting cellular respiration and causing severe toxicity [2]. However, this perception began to shift drastically with the discovery that H2S is endogenously produced in various tissues, particularly within the nervous system, where it plays a vital signaling role [3, 4]. Although interest in H2S as a signaling molecule developed later, it is now recognized that H2S exerts regulatory functions in a wide range of plant processes, influencing physiological functions from seed germination to flowering and fruit ripening [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10], as well as mechanisms of response to both biotic [11, 12] and abiotic stress conditions [13, 14], including drought [15], extreme temperatures [16, 17, 18], heavy metals [19, 20], light conditions, carbon deprivation [21], and phosphate starvation [22], among others [23]. Fig. 1 summarizes some of the key plant processes in which H2S is directly or indirectly involved.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Main functions of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in higher plants.

H2S is a weak acid that, in an aqueous solution at physiological pH, primarily exists in the form of hydrogen sulfide (HS–). H2S exerts its regulatory function by interacting with the thiol group (-SH) of cysteine (Cys) residues in proteins, converting them into a persulfide group (-SSH). This post-translational modification (PTM) is known as persulfidation [24]. This interaction is not direct, as the persulfidation mechanism requires prior oxidation of the thiol group, such as disulfide formation (RSSR´) or S-sulfenylation (RSOH) [25]. Currently, the potential targets of persulfidation have been identified using proteomic approaches. For example, in Arabidopsis leaves, up to 3417 persulfidated proteins have been identified [26], though this number can vary under unfavorable conditions [21, 27]. In comparison, 891 persulfidated proteins were found in sweet pepper fruits [9]. However, the number of specific studies aimed at deciphering the effects of persulfidation on the function of target proteins remains limited, and among these, the number of transcription factors (TFs) susceptible to persulfidation is even smaller.

The activity and stability of some TFs can be modulated by various PTMs such as phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, S-sulfenylation, S-nitrosation, and also persulfidation [28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. These modifications can affect a transcription factor’s ability to bind DNA, interact with other proteins, or even lead to its degradation. The aim of this review is to provide an updated overview of the interrelationship between H2S metabolism and the regulation of TFs, as some may be targets of persulfidation. This, in turn, regulates gene expression involved in numerous metabolic pathways related to physiological processes, including responses to environmental stresses.

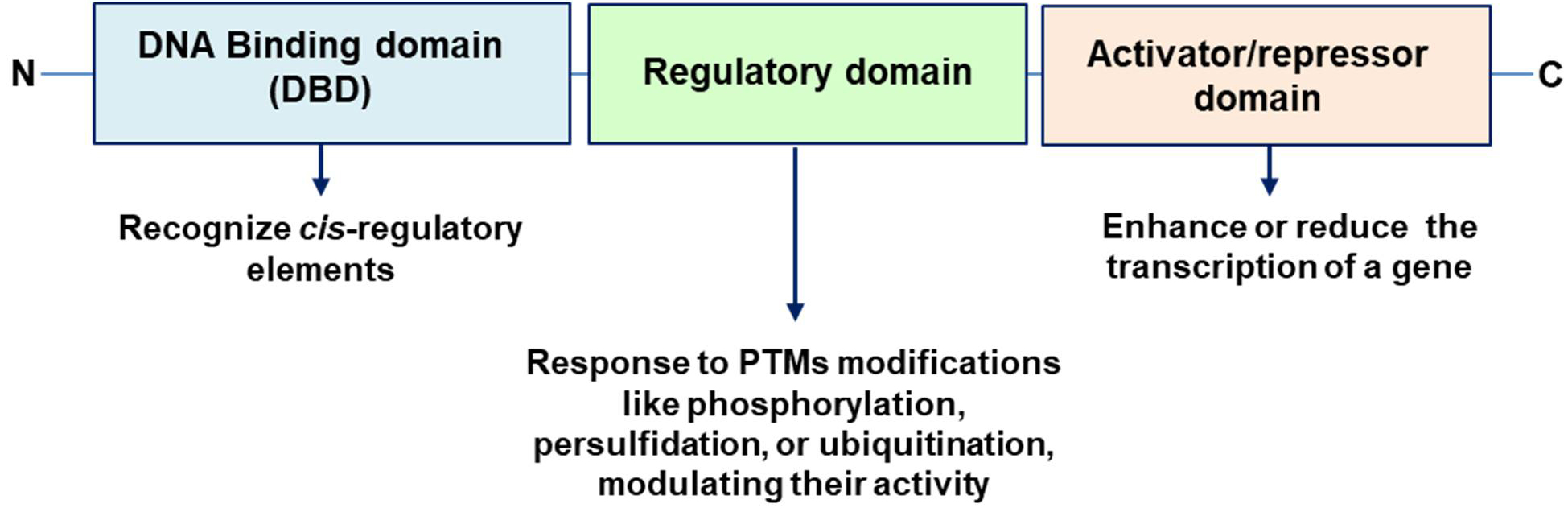

TFs are proteins that can either promote or inhibit the transcription of target genes, thereby controlling the production of mRNA and ultimately influencing protein synthesis and cellular function. TFs have three many key characteristics: (i) DNA Binding domain (DBD) that allow to the TF to bind to specific DNA sequences, known as cis-regulatory elements. These sequences are often found in the promoter regions of genes, and they bind to short DNA sequences ranging from 5 to 25 base pairs. (ii) Regulatory Domains, TFs typically possess regulatory domains that can interact with other proteins, including other TFs, coactivators, or corepressors, to modulate the transcription process. It is susceptible to being targeted by several PTMs. (iii) Activation and repression function, TFs can act as activators, which enhance the transcription of a gene, or as repressors, which reduce gene expression [35, 36] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Main key characteristics of TFs: DNA Binding domain (DBD), Regulatory Domains and Activator/repressor domain. C, C-terminus; N, N-terminus; PTMs, post-translational modifications.

Plants have hundreds of TFs, for example, Arabidopsis contains around 2300 TFs which corresponds to about 8.3% of its total number of genes [37]. Plant TFs have been categorized into approximately 58 families [38, 39], playing essential roles in growth and developmental processes [40], as well as in mechanisms responding to abiotic and biotic stresses [39, 41]. In this last case, six main families of TFs are the most studied including AP2/ERF (APETALA2/Ethylene Response Factor), WRKY, bHLH (basic helix-loop-helix), basic leucine zipper (bZIP), MYB, and NAC (NAM, ATAF1/2, and CUC2) [42, 43, 44, 45].

However, only few TFs have been described to interact with H2S directly or indirectly. Thus, Arabidopsis treated with an exogenous H2S donor showed increased expression of several TFs, including bHLH, NAC, and MYB, which mediated the expression of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes such as ascorbate peroxidase (APX), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, glutathione reductase (GR), and monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDAR), thereby enhancing drought tolerance [46]. This finding is consistent with previous studies in other plant species. For example, in maize (Zea mays) under drought stress, the TF ZmMYB-CC10 was found to bind to the promoter region of ZmAPX4, resulting in increased APX expression and activity [47]. Similarly, the overexpression of the MYB123 gene in the tree Betula platyphylla enhances the activities of SOD and peroxidase (POD) enzymes, reducing the content of ROS under drought-stress conditions [48]. Therefore, it could be hypothesized that in these cases of drought stress where these TFs promote the antioxidant system, it could be mediated by H2S, since, in other cases; the exogenous application of H2S also promotes the increase of enzymatic antioxidant systems.

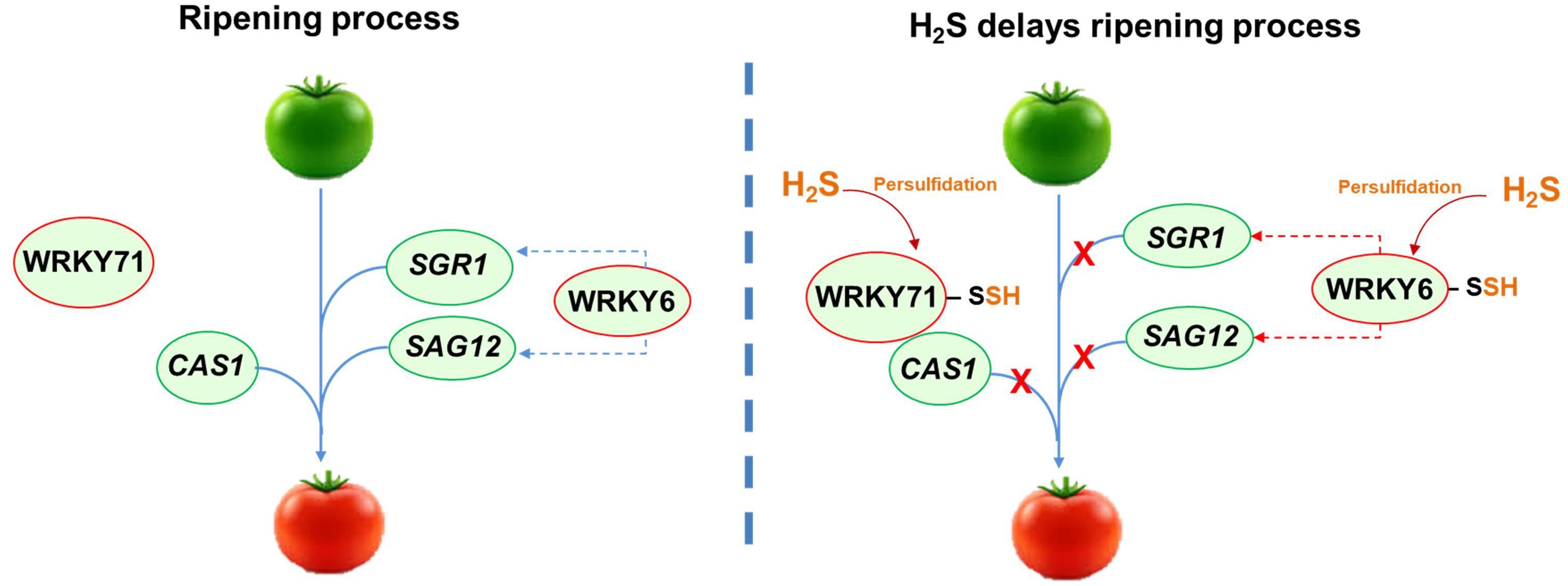

This family of TFs is characterized by the highly conserved WRKY amino acid sequence at the N-terminus. The WRKY domain is approximately 60 residues long and contains an atypical zinc-finger motif at the C-terminus, which can be either Cx₄₋₅Cx₂₂₋₂₃HxH or Cx₇Cx₂₃HxC [49]. Additionally, most WRKY TFs bind to the W-box promoter element, which has the consensus sequence TTGACC/T. A correlation between various WRKY TFs and H2S metabolism has been observed. In Arabidopsis, under cadmium stress, the overexpression of the gene encoding the H2S-generating enzyme D-cysteine desulfhydrase (DCD) is mediated by WRKY13. WRKY13 binds to the promoter of the DCD gene, leading to increased DCD expression, which helps reduce oxidative stress caused by cadmium exposure [50] (Fig. 3). In pepper seedlings treated with exogenous application of a H2S donor, it was found that the mitogen‑activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade was triggered, leading to the upregulation of WRKY22 and PTI6 (pathogenesis-related gene transcriptional activator 6). Additionally, H2S induces defense genes and activates ethylene and gibberellin synthesis receptors, including ERF1 (ethylene-responsive transcription factor 1), GID2 (GIBBERELLIN-INSENSITIVE DWARF 2), and DELLA (the protein name refers to five conserved amino acids: aspartic acid, glutamic acid, leucine, leucine, and alanine, found in their N-terminal domain), enhancing the resistance of pepper seedlings to low-temperature chilling injury [51]. On the other hand, in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruits, it has been identified that after H2S treatment, several WRKY TFs (WRKY71 and WRKY6) underwent persulfidation, delaying fruit ripening by different mechanisms. In tomatoes, WRKY71 functions as a repressor of ripening, and its activity can be regulated by various processes involving H2S. Specifically, the persulfidation of WRKY71 enhances its ability to bind to the CYANOALANINE SYNTHASE1 (CAS1) gene, which promotes ripening. This increased binding inhibits the expression of CAS1, thereby delaying the ripening process (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the persulfidation of E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase 3 (BRG3) decreases the degradation of WRKY71, allowing it to maintain its role as a repressor of ripening [52]. On the other hand, the TF WRKY6 positively modulates ripening by activating the transcription of the genes STAYGREEN 1 (SGR1) and Senescence-Associated Gene 12 (SAG12). Persulfidation of WRKY6 at Cys396 causes a suppression of the expression of SGR1 and SAG12, which causes a delay in tomato fruit ripening (Fig. 3). Additionally, the phosphorylation of WRKY6 at the Ser33 by the mitogen-activated protein kinases 4 (MAPK4), which normally promotes ripening, is inhibited by the persulfidated form of WRKY6 [53]. As a result, high levels of H2S contribute to a delay in the ripening of tomato fruit by combining several mechanisms where TFs have multiple levels of regulation by persulfidation, ubiquitination, and phosphorylation.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Model illustrating the role of H2S in delaying tomato fruit ripening through the persulfidation of transcription factors WRKY71 and WRKY6. This modification prevents the expression of genes such as CAS1 (CYANOALANINE SYNTHASE1), SGR1 (STAYGREEN 1), and SAG12 (Senescence-Associated Gene 12), which are key regulators of the ripening process. Dashed blue line indicates positive regulation while dashed red line indicates negative regulation.

NAC TF is an abbreviation for three genes: NAM (no apical meristem), ATAF (Arabidopsis transcription activation factor), and CUC (cup-shaped cotyledon). These TFs form one of the largest transcription factor families in plants, with around 117 members in Arabidopsis, 151 in rice (Oryza sativa) [54], and 152 in soybean (Glycine max) [55]. NAC TFs play important roles in plant development [56] and defense responses [57, 58, 59]. In this case, information on the relationship between H2S and NAC TFs is also very limited. In apple (Malus domestica cv. Red Fuji) fruit treated with an exogenous H2S donor, there is an increase in the expression of NAC1, which enhances the antioxidant activity of fresh-cut apples [60]. On the other hand, in rice seedlings, NACL35 (NAC35-like) mediates an increase in H2S production by upregulating DCD1, which promotes greater salt-stress tolerance [61].

The first documented MYB TF was identified as the “v-MYB” oncogene in avian myeloblastosis virus. The structure of MYB proteins includes a conserved N-terminal DNA-binding domain (the MYB domain), a transcription activation domain, and a variable C-terminal regulatory domain [62, 63]. In higher plants, MYB TFs play key roles in growth, development, and stress responses [64, 65, 66, 67].

Anthocyanins are important pigments responsible for red, purple, and blue colors in plants, and their biosynthesis is critical for fruit coloration. Persulfidation of the MYB10 TF has been specifically identified at the Cys194 and Cys128 residues, which plays a critical role in inhibiting anthocyanin biosynthesis in the skin of pear fruits [68]. The persulfidation of MYB10, therefore, not only affects pigment accumulation but also impacts the aesthetic and commercial quality of pear fruits. This demonstrates how H2S signaling can influence secondary metabolite production and the phenotypic traits of fruits. Exogenous H2S has been also shown to have a different effect on other MYB TFs. For instance, H2S stimulates the MYB128 TF, which plays a protective role in preventing premature senescence of nodules during the symbiotic interaction between soybean (Glycine max) and Sinorhizobium fredii [69]. This interaction is vital for nitrogen fixation, a process that enhances the availability of nitrogen to the plant, promoting growth and productivity, especially in nitrogen-poor soils. By preventing the early senescence of nodules, H2S indirectly supports the longevity and efficiency of the symbiosis, which is critical for optimal soybean yield.

These contrasting roles of H2S, whether inhibiting pigment production in pear fruits through MYB10 persulfidation or enhancing nodule longevity in soybean through MYB128 activation, highlight the multifaceted nature of H2S signaling.

This family of TFs also regulates a wide range of plant processes including growth and development and in the mechanism of response to stresses such a cold, drought, and salt, as well as in iron homeostasis [70, 71, 72]. The bHLH proteins bind to either E-box (CANNTG) or G-box (CACGTG) motifs in the target promoter and interact with various other factors to constitute a complex regulatory network [72, 73]. Although information on bHLH and its interaction with H2S is limited, a few examples do demonstrate the connection. In cucumber, persulfidation of bHLH TFs (His-Csa5G156220 and His-Csa5G157230) increases the expression of cucurbitacin C synthetase improving the resistance of plants to abiotic stresses and biotic stresses [74]. On the other hand, peach fruits treated with an H2S donor showed increased expression of bHLH3, which in turn upregulated the expression of sucrose synthase (SS-s) and sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS), while downregulating vacuolar invertase (VIN) and neutral invertase (NI). This led to sucrose accumulation and enhanced cold resistance in cold-stored fruit [75]. In tomato plants under salinity stress, the bHLH92 TF triggered an increase in LCD1 (L-cysteine desulfhydrase 1) expression, leading to a concomitant rise in H2S content. This TF also upregulates other genes, including CALCINEURIN B-LIKE PROTEIN 10 (CBL10) and VQ16, which are involved in the salinity response. Additionally, the VQ16 gene encodes a protein containing the conserved VQ motif (FxxhVQxhTG), which interacts with bHLH92 to enhance its transcriptional activity [76].

ABI TFs are essential players in the regulation of plant responses to abscisic acid (ABA), a key hormone that significantly influences abiotic stress tolerance and critical developmental processes. These include vital functions such as seed dormancy, germination, and stomatal closure, highlighting the importance of ABI TFs in enhancing plant resilience and adaptability [77, 78, 79]. These TFs were first identified in mutants that displayed insensitivity to ABA, leading to the “ABA-insensitive” (ABI) designation. Key members of this group include ABI3, ABI4, and ABI5.

ABI3 primarily regulates seed maturation and dormancy. Mutations in ABI3 result in premature seed germination and reduced sensitivity to ABA. ABI4 is involved in seed germination and early seedling development. It regulates responses to ABA, sugar signaling, and various environmental stresses. ABI4 is a member of the AP2/ERF (APETALA2/Ethylene Response Factor) family and interacts with abscisic acid-responsive element (ABRE)-binding factors (ABFs), transcription factors that regulate the expression of genes involved in drought, osmotic stress tolerance, and salinity by binding to ABRE cis-elements in their promoter regions [79, 80]. ABI4 regulates gene expression by either activating or repressing it, binding to specific DNA sequences in promoters through its AP2 domain. In Arabidopsis seeds, the combined action of ABI4 and DES1-produced H2S has inhibitory effects on seed germination. ABI4 can activate DES1 transcription by binding to its promoter, and persulfidation at Cys250 of ABI4 prevents its degradation [81].

ABI5 functions primarily during seed germination and early growth stages. It belongs to the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family of transcription factors and promotes the expression of ABA-responsive genes, playing a critical role in regulating seed dormancy and germination, especially under stress conditions [82, 83, 84]. ABI TFs interact with key components of the ABA signaling pathway, including pyrabactin resistance1/PYR1-like/regulatory components of ABA receptor (PYR/PYL/RCAR), protein phosphatase 2Cs (PP2Cs), and SNF1-related protein kinases (SnRK2s), to fine-tune plant responses to environmental challenges such as water deficit and osmotic stress. ABI5 is known to undergo several PTMs, including phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, ubiquitination, and sumoylation [28]. More recently, H2S has been identified as a modulator of ABI5 activity. In Arabidopsis, it is known that high temperatures inhibit seed germination through a complex mechanism. Under high-temperature conditions, several factors come into play. Thus, high temperatures accelerate the translocation of the E3 ligase CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS 1 (COP1) from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, leading to the nuclear accumulation of ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 (HY5). HY5 then activates the expression of ABI5, thereby suppressing seed germination. However, H2S signaling has been shown to reverse this high-temperature effect because H2S increases COP1 levels in the nucleus, promoting the degradation of HY5, which leads to reduced ABI5 expression and enhanced thermotolerance during seed germination [84].

Table 1 (Ref. [10, 50, 51, 52, 53, 60, 61, 68, 69, 74, 75, 81, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93]) summarizes additional examples of the relationships between H2S and various TFs that interact either directly or indirectly with H2S metabolism, as well as plant TFs that are regulated through persulfidation.

| Plant species/organs | TF | Persulfidated Cys | H2S metabolism | Ref. |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | WRKY13 | UN | Cadmium (Cd) exposure induces the DCD expression, which enhances the production of H2S, thereby improving Cd tolerance in plants. | [50] |

| Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) seedling | WRKY22 | UN | Exposure to H2S triggers the upregulation of WRKY22 and PTI6, induces defense genes, and activates ethylene and gibberellin synthesis receptors (ERF1, GID2, and DELLA), thereby collectively increasing the resistance of pepper seedlings to low-temperature chilling injury. | [51] |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruits | WRKY71 | UN | WRKY71 is upregulated in H2S-treated tomatoes via transcriptome profiling and delete fruit ripening. | [52] |

| Tomato (S. lycopersicum) fruit | WRKY6 | Cys396 | Persulfidation delates tomato fruit ripening whereas phosphorylation promotes fruit ripening. | [53] |

| Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaf | WRKY70b | UN | Exogenous H2S treatment downregulated WRKY70b, influencing leaf senescence by promoting ROS accumulation and disrupting H2S biosynthesis. | [85] |

| Apple (Malus domestica cv. Red Fuji) | NAC 1 | UN | H2S treatment enhances the expression of NAC TF which triggers the antioxidant activity in fresh-cut apples. | [60] |

| Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Seedling | NACL35 | UN | NAC TF triggers H2S production by upregulation of DCD1 and provides salt-stress tolerance in rice seedlings. | [61] |

| Pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai) fruit | MYB10 | Cys194 Cys218 | The persulfidation of MYB10 provokes the inhibition of anthocyanin production in red-skinned pears. | [68] |

| Soybean (Glycine max)-Sinorhizobium fredii symbiotic interaction | MYB128 | UN | H2S plays an important role in maintaining efficient symbiosis and preventing premature senescence of soybean nodules. | [69] |

| Carrot (Daucus carota) | MYB62 | UN | Heterologous expression of carrot MYB62 promotes the biosynthesis of ABA and H2S, which suppress the formation of H2O2 and superoxide anion, while also stimulating stomatal closure. | [86] |

| Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L) | bHLH | UN | Persulfidation of bHLH transcription factors (His-Csa5G156220 and His-Csa5G157230) increases the expression of cucurbitacin C synthetase improving the resistance of plants to abiotic stresses and biotic stresses. | [74] |

| Peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch) fruit | bHLH3 | H2S induces bHLH3, which regulates sugar metabolism-related genes involved in mediating cold tolerance during storage. | [75] | |

| Apple (Malus domestica) | AP2/ERFs, and bHLHs | UN | In calcium-deficient peels, the production of H2S is reduced. Additionally, CML 5 shows a positive correlation with the expression of ERF2/17, bHLH2, and genes related to H2S production. | [87] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | ABI5 | UN | H2S countered the high-temperature effect by increasing COP1 in the nucleus. This led to enhanced degradation of HY5 and a reduction in ABI5 expression, thereby improving thermotolerance during seed germination. | [88] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana seed | ABI4 | Cys250 | ABI4 activates DES1 transcription by binding to its promoter, and Cys250 from ABI4 is critical for its binding. Both ABI4 and DES1-produced H2S have inhibitory effects on seed germination. Persulfidation of Cys250 of ABI4 inhibits its degradation. | [10, 81] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | TGA3 | UN | Under chromium (Cr6+) stress, the Ca2+ /calmodulin2-binding TF TGA3 increases LCD expression and endogenous H2S content | [89] |

| Kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor 4 (ERF4) and ERF113. | UN | H2S inhibits the expression of ethylene receptor 2 (ETR2), ERF003, ERF5, and ERF016, whereas increases the expression of ethylene-responsive transcription factor 4 (ERF4) and ERF113. | [90] |

| Tomato (S.lycopersicum) | ERF.D3 | Cys115 Cys118 | H2S delays dark-induced senescence in tomato leaves and fruit ripening through the persulfidation of ERF.D3 | [91] |

| Grapevine (Vitis vinifera) leaves | DREB2A | UN | The DREB2A TF is induced by H2S and improved resistance to cold stress | [92] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | U2AF65a | UN | Exogenous H2S promotes flowering. | [93] |

ABA, abscisic acid; ABI4, ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 4; AP2/ERFs, APETALA2/Ethylene Response Factors; bHLH, basic helix-loop-helix; CML, calmodulin-like protein; COP1, CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS 1; DCD, D-cysteine desulfhydrase; DELLA, the protein name refers to five conserved amino acids: aspartic acid, glutamic acid, leucine, leucine, and alanine, found in their N-terminal domain; DES1, L-cysteine desulfhydrase 1; DREB, Dehydration responsive element-binding; ERF4, ethylene-responsive transcription factor 4; GID2, GIBBERELLIN-INSENSITIVE DWARF 2; HY5, ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5; LCD, L-cysteine desulfhydrase; NAC, (NAM, ATAF, and CUC) transcription factors; PTI6, pathogenesis-related gene transcriptional activator 6; TGA3, TGACG-binding (TGA) transcription factor 3; UN, unidentified Cys.

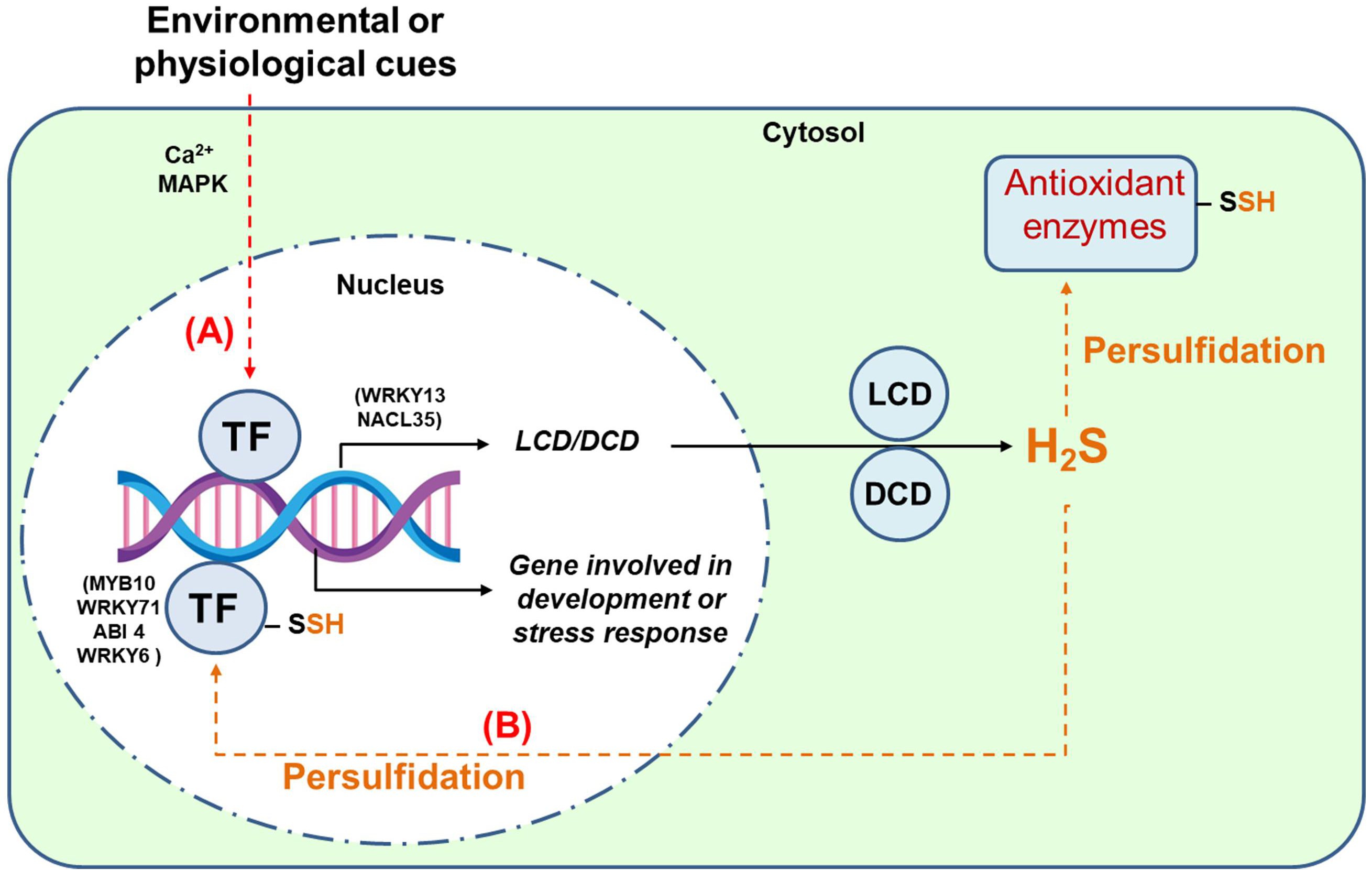

Fig. 4 provides a conceptual framework connecting TFs with the H2S signaling pathway, showcasing their intricate roles in plant cellular responses to environmental stimuli. Environmental cues, such as abiotic stressors (e.g., drought, salinity, and temperature extremes) or biotic factors (e.g., pathogen attack), trigger signaling cascades that often involve secondary messengers like calcium ions (Ca2⁺) and MAPK pathways. These cascades lead to the activation of specific TFs, which regulate gene expression by binding to promoter regions of target genes. Among these target genes are those encoding key enzymes like L-cysteine desulfhydrase (LCD) and D-cysteine desulfhydrase (DCD), which catalyze the production of H2S. Once synthesized, H2S can involve in thiol-based oxidative PTMs such as persulfidation, which alters the function of target proteins, including antioxidant enzymes. This modification can fine-tune reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, balancing their signaling roles and toxicity to mitigate oxidative stress. An intriguing aspect of this model is the reciprocal regulation between TFs and H2S signaling. Certain TFs susceptible to persulfidation (as outlined in Table 1) may undergo conformational changes affecting their DNA-binding or transactivation capabilities. This dual-layer interaction underscores a feedback loop where TFs regulate H2S production and, in turn, are influenced by H2S-mediated modifications. Through these dynamics, TFs can orchestrate the expression of genes involved in diverse metabolic pathways, affecting processes like secondary metabolism, growth regulation, and defense responses. Thus, this model highlights the multi-dimensional role of H2S in plant signaling networks, bridging transcriptional regulation and biochemical pathways.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Working model of the interrelationship between transcription factors (TFs) and the H2S signaling mechanism. Route (A), Environmental cues can, through Ca2+ and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades, stimulate TFs that, in turn, can induce the expression of genes that code for enzymes that generate H2S such as L-cysteine desulfhydrase (LCD) and D-cysteine desulfhydrase (DCD). This H2S may well persulfidate antioxidant enzymes and regulate the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Route (B), TFs susceptible to being persulfidated, i.e., ABI 4. MYB10, WRKY6, or WRKY71, can stimulate or inhibit genes involved in different metabolic pathways and the enzymes they encode, affecting different metabolic pathways.

Transcription factors (TFs) are key regulatory proteins involved in controlling plant developmental processes and responses to stress [94]. While TFs are known to be modulated by various post-translational modifications (PTMs) [29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 95], knowledge remains limited on how many among the hundreds of TFs in higher plants regulate H2S metabolism or serve as targets of persulfidation. Given H2S’s role as a significant signaling molecule, understanding its interactions with TFs is crucial for developing strategies to enhance crop resilience and improve agricultural productivity. Depending on the specific TF and plant context, H2S can either suppress or promote certain physiological responses. This highlights the importance of further research into H2S-mediated persulfidation and its potential implications for metabolic regulation, stress tolerance, and crop improvement. As this field is relatively new, ongoing studies aim to elucidate the full spectrum of TFs affected by persulfidation and their downstream impacts on gene expression.

The FJC was responsible for the conception of ideas presented, writing, and the entire preparation of this manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

FJC research is supported by a European Regional Development Fund co-financed grants from the Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2023-145153NB-C21 and CPP2021-008703), Spain.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.