1 Department of Pediatrics, Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, FL 33136, USA

2 Department of Internal Medicine, Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, FL 33136, USA

3 University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33136, USA

4 Division of Allergy and Immunology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33136, USA

§Current affiliation: Department of Allergy and Immunology, MemorialHealthcare System, Hollywood, FL 33021, USA

Abstract

Inborn errors of immunity (IEIs) are a group of more than 485 disorders that impair immune development and function with variable reported incidence, severity, and clinical phenotypes. A subset of IEIs blend increased susceptibility to infection, autoimmunity, and malignancy and are known collectively as primary immune regulatory disorders (PIRDs). Programmed cell death, or apoptosis, is crucial for maintaining the balance of lymphocytes. Genetic-level identification of several human inherited diseases with impaired apoptosis has been achieved, such as autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS), caspase-8 deficiency state (CEDS), X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome (XLP), and Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway disorders. The consequences of this disease are manifested by abnormal lymphocyte accumulation, resulting in clinical features such as lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and an increased risk of lymphoma. Additionally, these disorders are often associated with autoimmune disease, particularly involving blood cells. Understanding the molecular pathogenesis of these conditions has provided critical insights into the signaling pathways that regulate apoptosis and lymphocyte activation, shedding light on mechanisms of immune dysregulation. This review focuses on the intersection between apoptosis, autoimmunity, and lymphoproliferation, discussing how dysregulation contributes to the development of these immune disorders. These conditions are characterized by excessive lymphocyte accumulation, autoimmunity, and/or immunodeficiency. Understanding their molecular pathogenesis has offered new insights into the signaling mechanisms that regulate apoptosis and lymphocyte activation.

Keywords

- primary immune deficiency (PID)

- apoptosis

- autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS)

- X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP)

- inborn errors of immunity (IEI)

The equilibrium of normal immune cell activity relies on a dynamic interplay between cell proliferation and cell death [1]. The genetic programs governing cell death are remarkably conserved and play a crucial role in the proper development of immune and non-immune organ systems, particularly in the maturation of both T cells and B cells [2].

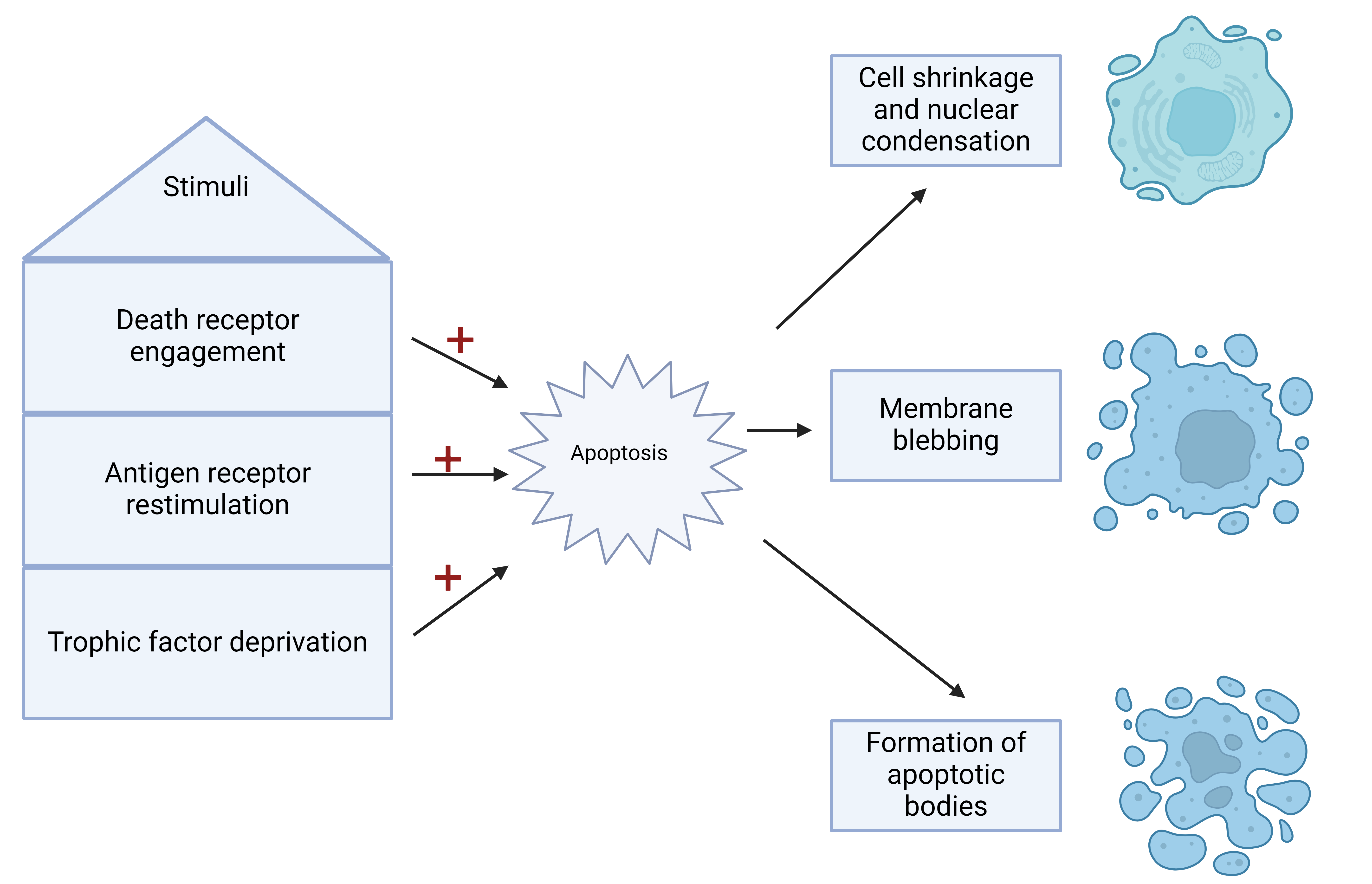

Apoptosis, a type of programmed cell death, is an orchestrated and self-contained process wherein cells dismantle themselves without inducing inflammation [3]. Morphologically, apoptosis is characterized by shrinkage, rounding, vacuolar and vesicular formation, nuclear condensation with fragmentation, membrane blebbing, and breakdown into apoptotic bodies containing nuclear fragments and intact organelles [3, 4] (Fig. 1). This physiological mechanism is essential in lymphocytes [5], where various stimuli, such as death receptor engagement, antigen receptor restimulation (known as “activation-induced cell death” or AICD), or the deprivation of trophic factors like IL-2, prompt cells to undergo self-destruction [6, 7].

Defects in apoptosis within IEI require thorough clinical evaluation and genetic testing, as they often present with non-specific symptoms such as lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and autoimmune cytopenia [8]. Genetic testing plays a crucial role in identifying specific mutations, providing a definitive diagnosis for these conditions. Additionally, flow cytometry can detect elevated levels of double-negative T cells (DNTs), a hallmark feature of autoimmune [9] lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS), one of the prototype diseases influenced by defective apoptosis, though also a non-specific marker for immune dysregulation.

This review will explore IEI impacted by both direct and indirect apoptosis defects. The review will highlight key prototype diseases, including ALPS and X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome (XLP), and other conditions where apoptosis dysregulation significantly contributes to immune dysfunction. Disorders involving the JAK/STAT signaling pathway serve as examples of IEI where apoptosis is indirectly affected, leading to widespread immune dysregulation and this review will focus on these disorders which compose the majority of the IEIs associated with apoptosis defects.

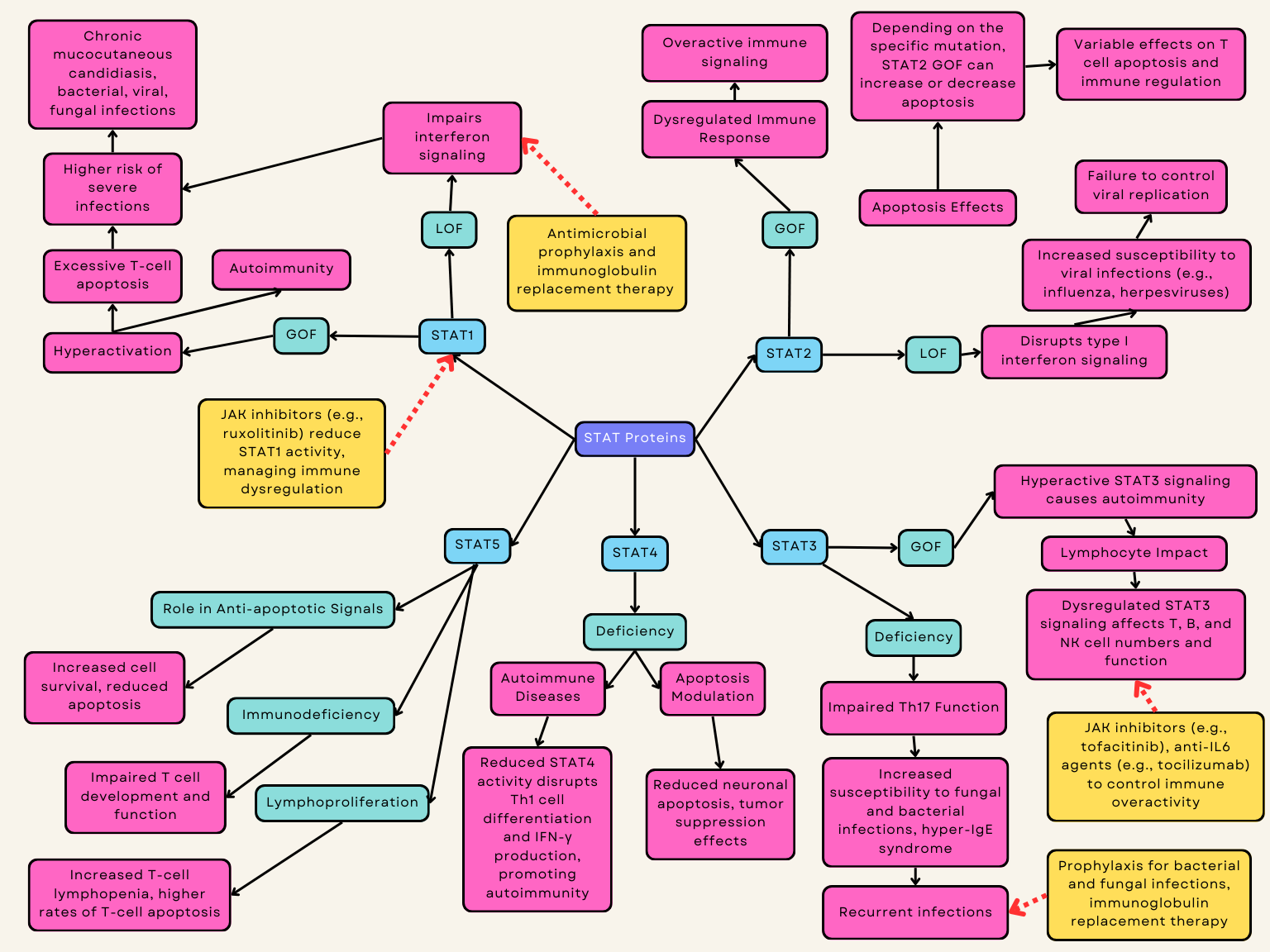

Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome (ALPS) is a genetic disorder characterized by defective apoptosis of lymphocytes, leading to lymphoproliferation and autoimmune manifestations (Fig. 2). Currently, ALPS is diagnosed based upon fulfillment of two criteria: elevated CD3+CD4-CD8- double-negative T cells (

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Inborn errors of immunity directly impacted by apoptosis. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease. Created with Biorender.com.

FAS, also known as CD95 or tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6 (TNFRSF6), is a cell surface receptor that triggers apoptosis through binding to its ligand. Deficiency of FASL is one of the most reported variants associated with ALPS, second only to mutations in the FAS gene itself. Variants in the FAS gene impair apoptotic transduction signaling and ultimately result in the pathologic accumulation of lymphocytes seen in ALPS (Table 1, Ref. [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61]). FAS genetic variants involved in ALPS are largely of germline origin, but somatic mutations are also disease-causing but underdiagnosed due to the challenge of diagnostic sequencing as well as the potential overlap with comorbid autoimmune disorders [62, 63, 64].

| Disease | Pathophysiology | Treatment |

| Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome (ALPS) | Mutations in FAS and FAS ligand FASL, as well as Caspase-10 gene, can impair apoptotic transduction signaling and result in characteristic lymphocytic accumulation in the lymph nodes, spleen, and/or liver. | Manage autoimmune manifestations and prevent complications of symptoms via immunosuppressive drugs and/or corticosteroids. |

| HPCT is considered a curative treatment but reserved for selected patients [55]. | ||

| ALPS Mimicker: Caspase-8 Deficiency | Loss of caspase-8 results in immunodeficiency similar to ALPS; caspase-8 cleaves and deactivates a suppressor of cytokine production, NEDD4-binding protein 1 (N4BP1). | Management similar to ALPS. No curative treatment except for HSCT [14]. |

| RAS-associated Lymphoproliferative Disease (RALD) | Mutations in the RAS gene can interfere with immune receptor signaling, integral to regulating cell division and growth [15]. | Corticosteroids are commonly used to control inflammation and manage autoimmune symptoms. Inhibitors targeting the RAS/MAPK pathway, like trametinib, are being explored for their potential to directly address the underlying genetic mutations [16, 17]. Biologic agents such as rituximab [18] and sirolimus may be utilized to deplete B cells and reduce lymphoproliferation [13]. HSCT may be considered for patients with severe or refractory disease, aiming for a potential cure [16, 18]. |

| X-linked Lymphoproliferative Syndrome (XLP) | Two monogenetic etiologies for XLP: SH2DIA deficiency (XLP1) and BIRC4 deficiency (XLP2). | Evidence suggests that along with immunosuppressive agents, rituximab can be of life-saving benefit for patients with XLP caused by Epstein-Barr virus [58]. Curative treatments include bone marrow or umbilical cord blood transplantation [59]. |

| XLP1: SLAM - SAP LOF. | ||

| XLP2: Loss of function of XIAP, expressed widely in immune cells as an inhibitor of apoptosis due to its ubiquitin ligase activity and its ability to bind and deactivate several caspases. | ||

| STAT1 Disease | STAT1 GOF syndrome: T lymphocyte apoptosis is increased, and T lymphopenia may determine higher risk of severe infections [20]. | STAT1: Antimicrobial prophylaxis. Patients with significant autoimmunity can also benefit from a JAK inhibitor [21, 22]. |

| STAT1 LOF: Impairs type I and II interferon pathways, leading to compromised immune responses and failure to control infections [23, 24, 25]. | ||

| STAT2 Disease | STAT2 GOF: Abnormal activation of the STAT2 protein, leading to dysregulated immune responses and apoptosis especially in T cells [27, 49]. Can either increase or decrease apoptosis depending on the specific molecular pathways affected [45]. | STAT2: Similarly to STAT1, prophylaxis with IVIG and antiviral agents. |

| STAT2 LOF: Can result in impaired antiviral responses, leading to increased vulnerability to viral infections [60] and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis [26, 28, 61]. | ||

| STAT3 Disease | STAT3 GOF: Somatic variants are associated with T or NK cell lymphoma, particularly T cell large granular lymphocyte leukemia. Conversely, the germline STAT3 GOF disease has infection susceptibility and decreased T, B, and NK cells [29, 30]. | STAT3: Treatment includes prophylaxis for bacterial and fungal infections, replacement immunoglobulin, monitoring for aneurysms/pulmonary disease [37, 38]. Patients often achieve positive outcomes on JAK inhibitors and anti-IL6 agents [31]. Anti-IL6 agents are particularly advantageous for patients with advanced pulmonary disease [32, 33]. HSCT has also been described in this disease [34, 35]. |

| STAT3 LOF: Responsible for the majority of cases of autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome [36]. | ||

| STAT4 Disease | STAT4 deficiency is linked to several autoimmune diseases, primarily SLE and RA [39]. Genetic variations in the STAT4 gene increase susceptibility to these conditions by promoting the production of autoantibodies and inflammatory processes characteristic of autoimmune disease [40]. | STAT4: Specific management depends on the systemic presentation of other autoimmune diseases. |

| STAT5 Disease | STAT5B GOF: observed in cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma, often with marked eosinophilia [42]. Recently, a distinct phenotype linked to STAT5B N642H variant has emerged affecting multiple hematopoietic cell types [43, 44] and it can be presented by severe hypereosinophilia, urticaria, dermatitis, and diarrhea [43]. | STAT5B GOF: Treatment with JAK inhibitors has shown promising results in reported cases, indicating potential efficacy against this newly recognized nonclonal STAT5B GOF disorder with atopic features [13]. |

| STAT5b deficiency: dysregulating the transcription of genes that inhibit cell death, such as those in the Bcl-2 family and caspases [41]. | Evidence suggests benefit in lung or bone marrow transplants depending on complications [45]. | |

| STAT6 Disease | STAT6 GOF can lead to dysregulation of apoptosis, particularly in immune cells. STAT6 is crucial for mediating IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, which are involved in the differentiation of Th2 cells and the regulation of immune responses [46, 47]. | Dupilumab (a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-4R |

| JAK1 Disease | JAK1 GOF: promote a disease characterized by hypereosinophilia syndrome, atopy, autoimmune thyroiditis, and further multiorgan involvement. | JAK inhibitors have been used as effective therapy for this condition [48, 49]. |

| JAK1 deficiency impairs IFN-Ɣ-induced phagosome acidification and apoptosis in THP-1 myeloid cells resulting in susceptibility to mycobacterial infection [50]. | ||

| JAK2 Disease | JAK2 V617F GOF: activation of JAK2 signaling which results in hematopoietic cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis [51, 52]. | JAK inhibitors have been used as effective therapy for this condition [48, 49]. |

| JAK3 Disease | Germline JAK3 GOF: described in one family presenting with NK cell lymphoproliferation, vasculitis, CVID, autoimmunity, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy [53]. | Treatment for JAK3 LOF SCID is HCST [51]. |

| JAK3 LOF: autosomal recessive T−B+NK− SCID due to impaired signaling through the common gamma chain ( | ||

| Other regulators of the JAK/STAT pathway: Tyk2 LOF disease | TYK2 is a member of the Janus kinase family (JAK1, 2, 3, and TYK2), is crucial for signaling through group 1 and 2 cytokine receptors, including IL-10, IL-12, IL-23, and IFN- | Treatment for Tyk2 LOF disease includes managing infections (antibiotic and antiviral prophylaxis), enhancing immune function through immunoglobulin replacement therapy, and ensuring up-to-date vaccinations [19]. HSCT might be considered in some cases. |

| SOCS1 haploinsufficiency | Germline variants in SOCS1 disrupt immune tolerance, resulting in impaired negative T-cell selection, defective lymphocyte apoptosis, loss of B cell tolerance, abnormal Treg function, uncontrolled T cell activation, and enhanced immune effector functions [54, 55]. | A case report shows a 42-year-old patient with SOCS1 responded well to tocilizumab treatment [13]. |

| USP18 related disorder | USP18 downregulates type I interferon signaling by blocking JAK1 access to the type I interferon receptor [56, 57]. | Treatment with ruxolitinib on a patient with USP18 variants led to prompt and sustained recovery [56]. |

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; Th2, T helper 2; IL-4R

While variations in FAS and FASL genes are well-understood as mediators of apoptosis deficiency in ALPS, the role of the caspase-10 gene is currently debated. Caspase-10 deficiency is frequently categorized as an ALPS-like syndrome, especially APLS-FAS due to its resemblance [65]; a defect in CASP10 may interfere with the appropriate apoptosis of immune cells, leading to abnormal immune activation and a buildup of autoreactive cells [66, 67]. Mutations in the CASP10 gene result in interruptions in the apoptosis pathway, influencing immune cell homeostasis and leading to immune dysregulation, which manifests as recurrent infections, autoimmune manifestations, and lymphoproliferative disorders [68].

Homologous to caspase-8, caspase-10 is thought to interact with transduction signaling downstream of FAS and FASL where variants of both can shape the resulting ALPS phenotype. The clinical observations in ALPS patients examined by Martínez-Feito et al. [67] indicate that the disease mechanism is driven by a “two-hit hypothesis” for activation. A recent study by Consonni et al. [68] found that mutation of caspase-10 did not impair FAS-mediated apoptosis nor ALPS clinical presentation in human studies, further emphasizing the need to consider multiple and potentially concurrent genetic variants along the FAS-mediated pathways to cause clinical disease [67, 68].

Clinically, patients can present hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy (often during childhood), skin manifestations such as urticaria, frequent infections and pancytopenia [69, 70].

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is considered a curative treatment but reserved for selected patients [71] (Table 2, Ref. [19, 20, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 31, 36, 40, 42, 43, 45, 47, 48, 49, 53, 58, 70, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104]).

| Disease | Manifestations | Comparison with other diseases |

| Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome (ALPS) and ALPS Mimickers | Both diseases can manifest with hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy (often during childhood); however skin manifestations such as urticaria, frequent infections and pancytopenia [70] seen in ALPS. | CASP-8 variants in humans have been correlated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and multi-organ lymphocytic infiltration with granulomas [72, 73]. |

| Autoimmune cytopenias: hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia, and are at an increased risk of developing lymphoma [98] mostly seen in ALPS mimickers. | ||

| RAS-associated Lymphoproliferative Disease (RALD) | Fever, fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats. On physical examination, they may show signs of enlarged lymph nodes, spleen, and liver [74, 75]. | Lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly can overlap with ALPS and ALPS Mimickers. |

| X-linked Lymphoproliferative Syndrome (XLP) | Susceptibility to EBV, fever, cytopenias, and hepatosplenomegaly but involvement of other organs is frequently observed [76, 77, 78]. | HLH is the most common and lethal presentation [76, 77, 78]. |

| SH2DIA deficiency (XLP1) | EBV-induced lymphoproliferative disorders, progressive hypogammaglobulinemia or dysgammaglobulinemia, and malignant lymphoma [79, 80, 81]. | Some patients can develop colitis and psoriasis, in addition to vasculitic lesions in organs such as the brain and lung [79, 81] and mimic other diseases. |

| BIRC4 deficiency (XLP2) | Similar manifestations of XLP1 and inflammatory bowel disease [78, 79], atypical inflammatory syndrome following viral infections such as COVID-19 [82]. | Viral infections can trigger a range of inflammatory syndromes in individuals with inborn errors of immunity similar to XLP2 [82]. |

| STAT1 Disease | STAT1 GOF can present with invasive fungal infections such as chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in addition to bacterial and viral infections, autoimmunity, and malignancy [84]. | STAT1 GOF can be a common variable immune deficiency (CVID) mimicker [20]. |

| STAT1 LOF disease can lead to compromised immune responses and failure to control infections [23, 24, 25] resembling STAT1 GOF. | ||

| STAT2 Disease | STAT2 GOF works in conjunction with STAT1 in the IFN signaling pathway [85, 86], leading to poor antiviral responses [87]. | STAT2 LOF can result in impaired antiviral responses, similar to STAT2 GOF [58] and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis [26, 28, 88]. |

| STAT3 Disease | STAT3 GOF exhibits autoimmune cytopenias and enteropathy [31]. | STAT3 mutations can resemble several diseases, particularly those involving immune dysregulation. The most notable condition is Hyper-IgE Syndrome (HIES), also known as Job’s Syndrome, which is caused by autosomal dominant mutations in the STAT3 gene. Patients with STAT3 mutations can present with recurrent skin and lung infections, eczema, elevated levels of IgE, and skeletal abnormalities [36]. |

| STAT3 LOF are responsible for the majority of cases of autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome, prompting elevated serum IgE levels, eosinophilia, recurrent cutaneous and sinopulmonary infections, eczema, and skeletal abnormalities [36]. The most common pathogens in STAT3 deficiency include Staphylococcus aureus, H. influenza, and Candida though patients are also susceptible to Pseudomonas, Aspergillus, Pseudomonas, Mycobacterium, and Varicella reactivation [36]. | ||

| STAT4 Disease | STAT4 GOF variants in the are linked to DPM, a severe systemic inflammatory condition. This disorder is characterized by poor wound healing, extensive fibrosis, cytopenias, hypogammaglobulinemia, and a high mortality rate primarily due to the development of squamous-cell carcinoma [91]. | STAT4 variants have also been associated with other autoimmune diseases such as SSc and primary Sjögren’s syndrome [89]. |

| STAT4 LOF is linked to several autoimmune diseases, primarily SLE and RA [40, 90]. | ||

| STAT5 Disease | STAT5B GOF N642H variant is associated with certain cancers, like leukemia and lymphoma, often accompanied by marked eosinophilia [42]. This variant also presents as a benign condition affecting various hematopoietic cell types, with early-onset symptoms including severe hypereosinophilia, urticaria, dermatitis, and diarrhea [43]. | STAT5b deficiency in contrats can lead to a new and potentially life-threatening primary immunodeficiency, frequently presenting as chronic lung disease or as an immunodeficiency syndrome marked by T cell deficiency, autoimmunity, recurrent and severe infections, and lymphoproliferation [45]. |

| STAT6 Disease | STAT6 GOF can lead to increased susceptibility to allergic diseases and other immune-related disorders [47]. | Similar to the characteristics of HIES, short stature, skeletal problems like pathological fractures, and widespread hypermobility were also observed. One patient had a notable history of B cell lymphoma, aligning with prior reports that have associated activating somatic mutations in STAT6 [99] |

| JAK Diseases | JAK1 GOF variants manifest as hypereosinophilia syndrome, atopy, autoimmune thyroiditis, and further multiorgan involvement [48, 49, 92, 93, 94]. | JAK disorders can mimic several conditions, including RA, SLE and psoriasis. They can also present similarly to myeloproliferative neoplasms like essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis [100]. Additionally, lymphoproliferative disorders, including various types of lymphomas and leukemias, may overlap in presentation. Vasculitis may also be mimicked, given the inflammatory processes involved in both JAK disorders and vasculitis [101]. |

| JAK2 GOF V617F variant can mirror MPNs, such as polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis [102]. | ||

| JAK3 GOF mutations have been reported to cause vasculitis, CVID, autoimmunity, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy [53]. | ||

| JAK3 LOF genetic variants result in SCID [95]. | This overlap in clinical presentations highlights the importance of accurate differential diagnosis in managing these conditions. | |

| Other regulators of the JAK/STAT pathway | Tyk2 LOF variant lead to individuals may exhibit susceptibility to mycobacterial and viral infections, excluding hyper-IgE syndrome, with reported sensitivity to mycobacteria, the BCG vaccine, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and other intra-macrophagic microbes [19, 83]. | SOCS1 haploinsufficiency can mimic several conditions, including SLE and rheumatoid arthritis, due to the dysregulation of immune responses [103, 104]. It may also present with features similar to HIES, characterized by elevated IgE levels and increased susceptibility to infections. CVID is another condition that can overlap with SOCS1 deficiency, as both are associated with immune deficiencies and a heightened risk of infections [104]. |

| SOCS1 haploinsufficiency may predispose to early-onset autoimmune diseases [96]. | ||

| USP18 related disorder. | USP18 related disorder presents with perinatal-onset intracranial hemorrhage, calcifications, brain malformations, liver dysfunction, septic-shock-like episodes, and thrombocytopenia [97]. | Features of USP18 variants mimic congenital intrauterine infections characteristic of TORCH but without detectable infection, leading to a diagnosis of pseudo-TORCH [97]. |

| The clinical overlap among these conditions complicates diagnosis, highlighting the need for careful evaluation and genetic testing to confirm. |

EBV, epstein-barr virus; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; COVID-19, corona virus disease 2019 caused by SARS-CoV-2; DPM, deep pansclerotic morphea; HIES, hyper-immunoglobulin E syndromes.

Caspase-8 is a key enzyme involved in initiating apoptosis. Deficiency of caspase-8 results in impaired apoptosis and can lead to lymphoproliferative disorders and immunodeficiency.

The apoptosis extrinsic pathway is initiated by caspase-8, a protein encoded by the CASP8 gene. This type of cellular demise is initiated through the interaction between death ligands and their corresponding death receptors located on the cell surface. Notably, caspase-8 assumes a dual role as it not only initiates apoptosis but also serves as an inhibitor of Receptor interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK3)/Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-Like pseudokinase (MLKL) dependent necroptosis [72, 105, 106] (Fig. 2).

In mice, the loss of caspase-8 leads to embryonic lethality through the induction of necroptosis and pyroptosis. This occurs due to uncontrolled RIPK3 activation and phosphorylation of the plasma membrane, which injures necroptotic effector MLKL [6, 106]. In humans, genetic variants in CASP-8 can result in an immunodeficiency, similar to ALPS [72]. This can be attributed to the process by which CASP-8 cleaves and deactivates a suppressor of cytokine production, NEDD4-binding protein 1 (N4BP1).

Clinical manifestations of CASP8 variants include chronic lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly [70] (Table 2). Patients may also experience autoimmune cytopenias, such as hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia, and are at an increased risk of developing lymphoma [69, 107]. Additionally, some patients may present with neurodevelopmental delays. Additionally, CASP-8 variants in humans have been correlated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and multi-organ lymphocytic infiltration with granulomas [72, 73].

Curative treatment options for CASP8 variants, particularly in the context of disorders like ALPS associated with CASP8 variants, are limited but evolving. The primary goal is to manage symptoms and prevent complications and HSCT is considered the most definitive treatment [14, 69, 105] (Fig. 2).

RAS-associated lymphoproliferative disease (RALD) is an uncommon condition marked by the excessive growth of lymphocytes. RALD is linked to mutations in the RAS gene, which is integral to regulating cell division and growth [15] (Fig. 2). Patients typically exhibit symptoms such as fever, fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats. On physical examination, they may show signs of enlarged lymph nodes, spleen, and liver [74, 75] (Table 2).

Bryostatin-1 and related diacylglycerol (DAG) analogues activate RasGRPs in lymphocytes, which in turn activate Ras and mimic certain aspects of immune receptor signaling [108]. When B cells are stimulated with DAG analogues, it triggers the protein kinase C/RasGRP-Ras-Raf-Mek-Erk pathway and leads to the phosphorylation of the proapoptotic protein Bim. Apoptosis in this context can be inhibited by either reducing Bim levels or increasing Bcl-2 expression. This process is also associated with the formation of Bak-Bax complexes and enhanced mitochondrial membrane permeability [75, 108].

Medications such as corticosteroids are commonly used to control inflammation and manage autoimmune symptoms. Inhibitors targeting the RAS/MAPK pathway, like MEK inhibitors (e.g., trametinib), are being explored for their potential to directly address the underlying genetic variants [16, 17]. Biologic agents such as rituximab (an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) [18] and sirolimus (mTOR inhibitors), may be utilized to deplete B cells and reduce lymphoproliferation in RALD [13] (Table 1). HSCT may be considered for patients with severe or refractory disease, aiming for a potential cure [16, 18].

X-linked lymphoproliferative (XLP) disease stands as a rare hereditary immune deficiency. It typically manifests in young boys as extreme susceptibility to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection causing a severe form of infectious mononucleosis, often leading to mortality. The disease presents as lymphoproliferative disorders, hypogammaglobulinemia, and features of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). HLH is the most common and lethal presentation. Features include fever, cytopenias, and hepatosplenomegaly but involvement of other organs is frequently observed (Table 2). The only cure for XLP is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) [76, 77, 109]. There are two monogenetic etiologies for XLP: SH2DIA deficiency (XLP1) and BIRC4 deficiency (XLP2) (Table 1). Both diseases can be diagnosed by genetic sequencing and confirmed by protein expression flow cytometry studies of the proteins expressed by SH2DIA and BIRC4. Furthermore, patients with XLP classically have significant immune dysregulation with very elevated IL-18 levels [109, 110].

The majority of XLP cases originate from pathogenic variants in the SH2D1A gene, resulting in XLP1. This gene codes for the Signaling Lymphocytic Activation Molecule (SLAM)-associated protein (SAP), leading to SAP loss of function which is located on the X chromosome. SH2D1A is expressed in T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and NKT cells. Individuals deficient in SAP often exhibit impairment in immune cell function, EBV-induced lymphoproliferative disorders, progressive hypogammaglobulinemia or dysgammaglobulinemia, and malignant lymphoma [78, 79, 111]. Patients with XLP1 can also have autoimmunity, most commonly colitis and psoriasis, in addition to vasculitic lesions in organs such as the brain and lung [79, 80]. Some patients with XLP1 can do clinically well due to somatic versions of SH2DIA [81].

Another cause of XLP arises from pathogenic variants in the BIRC4 gene, leading to XLP2, which is also located on the X chromosome. This disease is caused by the loss of function of X-linked inhibitors of apoptosis (XIAP). XIAP is expressed widely in immune cells such as T cells, B cells, NK cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages, as well as in nonimmune cells. A study has shown that XIAP acts as an inhibitor of apoptosis due to its ubiquitin ligase activity and its ability to bind and deactivate several caspases [112]. Patients lacking XIAP typically present with EBV-triggered lymphoproliferative disorders, transient hypogammaglobulinemia during HLH episodes, splenomegaly, and inflammatory bowel disease [78, 79] (Fig. 2).

There is a reported case of a patient with XLP2, caused by a deficiency in the XIAP, who developed an atypical inflammatory syndrome following a recent COVID-19 infection, Epstein-Barr viremia, and low chimerism [82]. This case underscores how viral infections can trigger a range of inflammatory syndromes in individuals with inborn errors of immunity (Table 2).

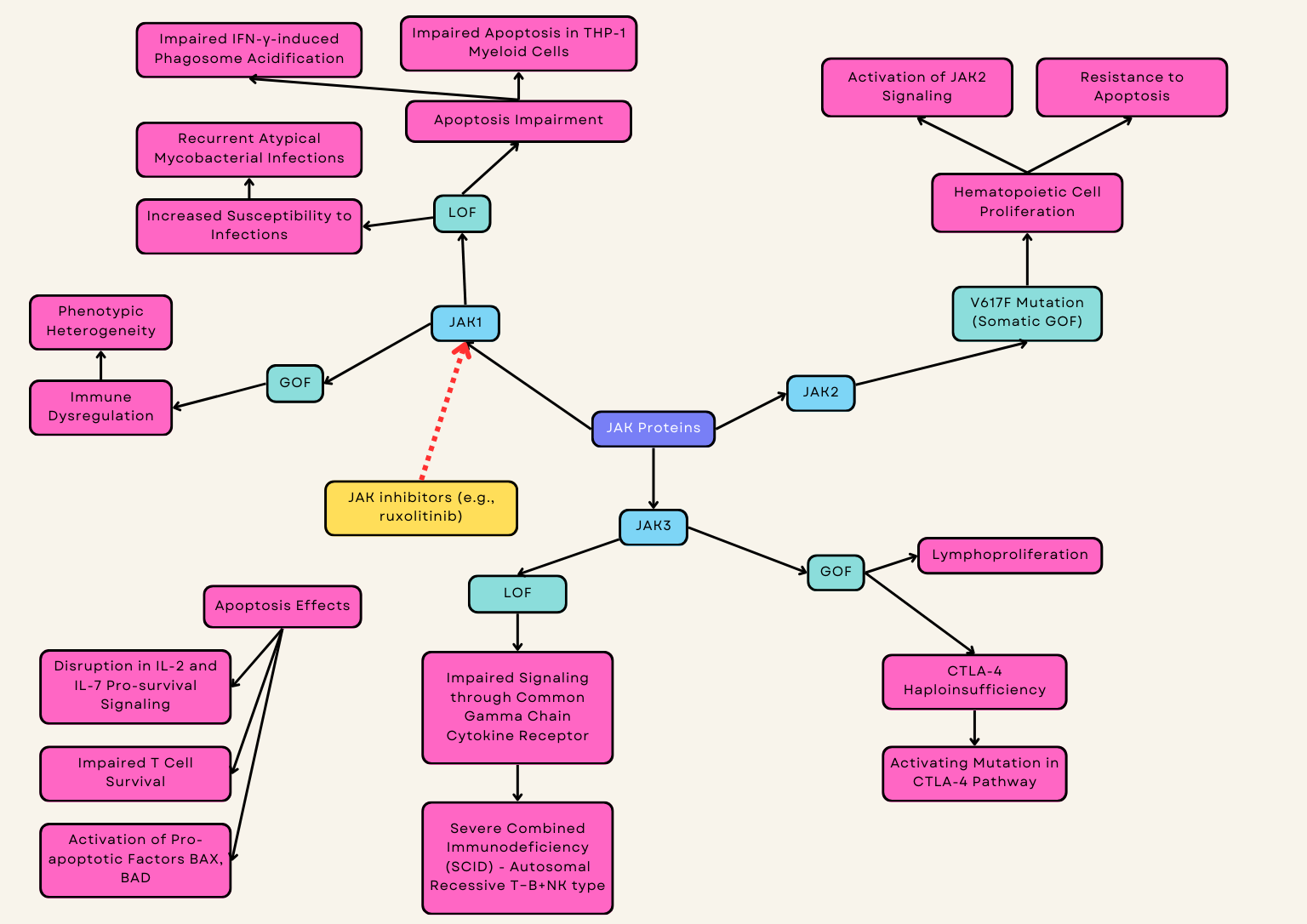

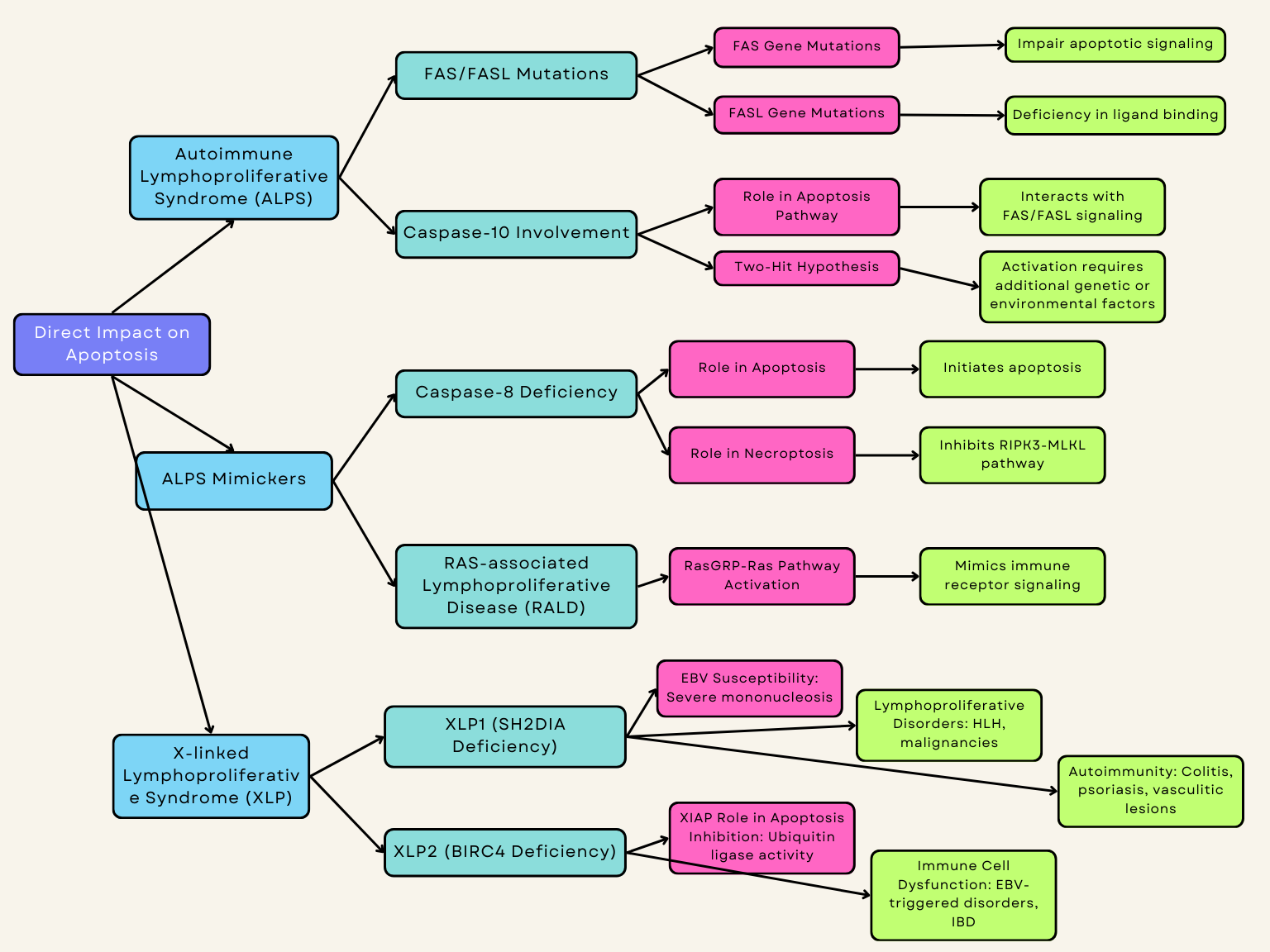

The JAK/STAT signaling pathway is present in most immune cells and is crucial for immune function and regulation of apoptosis [113]. Genetic variants in the proteins involved in this pathway - Janus tyrosine kinases (JAKs), signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs), and their regulator proteins - have been implicated in disease and inborn errors of immunity [109]. The treatment for STAT loss-of-function (LOF) disorders is variable but for STAT gain-of-function (GOF) disorders, JAK inhibitors are the mainstay initial treatments (Fig. 3).

Tyrosine Kinase 2 (Tyk2) LOF Disease

TYK2, a member of the Janus kinase family (JAK1, 2, 3, and TYK2), is crucial for signaling through group 1 and 2 cytokine receptors, including IL-10, IL-12, IL-23, and IFN-

The treatment for Tyk2 LOF disease includes managing infections with antibiotic and antiviral prophylaxis, enhancing immune function through immunoglobulin replacement therapy, and ensuring up-to-date vaccinations [83]. HSCT may be considered in severe cases where other treatments are ineffective (Table 1).

3.1.2.1 STAT1

STAT1 GOF syndrome accounts for most cases of chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis but is characterized by a broader clinical phenotype that may include bacterial, viral, or invasive fungal infections, autoimmunity, autoinflammatory manifestations, vascular complications, and malignancy [84] (Table 1). In STAT1-GOF patients, T lymphocyte apoptosis is increased, and T lymphopenia may determine higher risk of severe infections [20]. STAT1 GOF can be a common variable immune deficiency (CVID) mimicker present with hypogammaglobulinemia but patients will also commonly have T cell deficits (Table 2). Immune dysregulation is also common in STAT1 GOF disease with significant autoimmunity and abnormal interferon gamma signature. Management involves antimicrobial prophylaxis, often to bacterial, viral, and fungal infections, and patients with significant autoimmunity can also benefit from a JAK inhibitor which more specifically targets the dysregulated JAK/STAT pathway in this disease [21, 22]. On a biochemical level, patients with STAT1 variants not confirmed to be pathogenic can have their disease pathology confirmed by IL-6 and IL-27 induced STAT1 phosphorylation studies [114, 115]. In vitro studies suggest a JAK inhibitor can reverse T cell apoptosis in STAT1 GOF disease [20, 116, 117, 118].

STAT1 is essential for the signaling pathways activated by type I and type II interferons (Interferon (IFN)-

Due to the increased risk of infections, antibiotic prophylaxis is often considered for individuals with STAT1 variants. The goal is to prevent bacterial infections, particularly those that individuals with STAT1 variants are more prone to, such as respiratory infections, skin infections, and systemic infections [26]. Patients with significant autoimmunity can also benefit from a JAK inhibitor [21, 22] (Table 1).

3.1.2.2 STAT2

STAT2 GOF causes abnormal activation of the STAT2 protein, leading to dysregulated immune responses. This dysregulation primarily affects apoptosis, especially in T cells [27, 121] (Table 1). Depending on the genetic variant, STAT2 GOF can either increase or decrease apoptosis depending on the specific molecular pathways affected by the mutation [121].

STAT2 works in conjunction with STAT1 in the IFN signaling pathway, particularly type I IFNs (IFN-

Treatment for STAT2 is similar to that for STAT1 variants and includes antibiotic prophylaxis, immunoglobulin therapy, and antiviral agents [26] (Table 1).

3.1.2.3 STAT3

STAT3 GOF disease has been described both in germline and somatic variants in STAT3. Somatic variants are associated with T or NK cell lymphoma, particularly T cell large granular lymphocyte leukemia. Conversely, the germline STAT3 GOF disease has infection susceptibility and decreased T, B, and NK cells [29, 30]. This disease is also hallmarked by autoimmunity, most classically autoimmune cytopenias and enteropathy. Patients with STAT3 GOF often achieve positive outcomes on JAK inhibitors and anti-IL6 agents [31]. Anti-IL6 agents are particularly advantageous for patients with advanced pulmonary disease [32, 33]. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant has also been described as an option for curative treatment in this disease with variable success [34, 35]. Similarly, ZNF341 deficiency could potentially disrupt immune regulatory pathways, resulting in immune dysregulation that manifests similarly to STAT3 GOF [122]. Blockade of the IL-6 pathway using tocilizumab (an anti-IL-6R monoclonal antibody) in patients with a STAT3 GOF disease resulted in clinical improvement [13, 123] (Table 1).

STAT3 LOF disease has been shown to significantly suppress cell proliferation and tumor growth, and induce apoptosis [124]. Dominant negative mutations in STAT3 are responsible for the majority of cases of autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome, leading to impaired Th17 cell function, elevated serum IgE levels, eosinophilia, recurrent cutaneous and sinopulmonary infections, eczema, and skeletal abnormalities [36] (Table 2).

The most common pathogens in STAT3 deficiency include Staphylococcus aureus, H. influenza, and Candida though patients are also susceptible to Pseudomonas, Aspergillus, Pseudomonas, Mycobacterium, and Varicella reactivation [36]. Functional immunological testing often reveals the absence of Th17 cells. Treatment includes prophylaxis for bacterial and fungal infections, replacement immunoglobulin, monitoring for aneurysms, and close monitoring of pulmonary disease to prevent the development of pneumatoceles [37, 38].

3.1.2.4 STAT4

STAT4 has been shown to modulate apoptosis by acting as a tumor suppressor and by targeting KISS1 to reduce neuronal apoptosis [89, 90]. STAT4 enhances Th1 cell differentiation, cytotoxicity, and IFN

GOF variants in STAT4 cause disabling pansclerotic morphea (DPM), a systemic inflammatory disorder characterized by poor wound healing, fibrosis, cytopenias, hypogammaglobulinemia, and a high mortality rate due to squamous-cell carcinoma [91]. The JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib has been shown to attenuate the dermatologic and inflammatory phenotypes both in vitro and in affected family members [91].

STAT4 LOF is linked to several autoimmune diseases (Fig. 3), primarily systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [39]. Genetic variations in the STAT4 gene increase susceptibility to these conditions by promoting the production of autoantibodies and inflammatory processes characteristic of autoimmune disease [40, 91]. STAT4 variants have also been associated with other autoimmune diseases such as systemic sclerosis (SSc) and primary Sjögren’s syndrome, although the role of STAT4 in these diseases is less well-defined compared to SLE and RA [125] (Table 2).

Treatment varies, as specific management depends on the systemic presentation of associated autoimmune diseases (Table 1).

3.1.2.5 STAT5

STAT5 exclusively promotes anti-apoptotic, pro-survival signals by regulating the transcription of genes that inhibit cell death, such as those in the Bcl-2 family and caspases [41]. While T-cell lymphopenia is suggested to be related to higher rates of T-cell apoptosis which has previously been demonstrated in STAT5b deficient mice [126, 127] (Table 1).

STAT5B GOF, notably N642H, is observed in cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma, often with marked eosinophilia [42]. Recently, a distinct phenotype linked to STAT5B N642H variant has emerged: a benign condition affecting multiple hematopoietic cell types [43, 44]. This early-onset disorder presents with severe hypereosinophilia, urticaria, dermatitis, and diarrhea [43] (Fig. 3). Treatment with JAK inhibitors has shown promising results in reported cases, indicating potential efficacy against this newly recognized nonclonal STAT5B GOF disorder with atopic features [13] (Table 1).

Patients with STAT5b deficiency may develop a novel and potentially fatal primary immunodeficiency, often manifesting as chronic pulmonary disease [45] or as an immunodeficiency syndrome characterized by T cell deficiency, autoimmunity, recurrent and severe infections, and lymphoproliferation (Table 2).

3.1.2.6 STAT6

STAT6 GOF can lead to dysregulation of apoptosis, particularly in immune cells. STAT6 is crucial for mediating IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, which are involved in the differentiation of Th2 cells and the regulation of immune responses [46, 47]. GOF mutations can result in overactive STAT6 signaling, potentially causing excessive survival of certain immune cells, impaired apoptosis, and contributing to immune dysregulation. This dysregulation can manifest in various ways, including increased susceptibility to allergic diseases and other immune-related disorders [47].

Case reports indicate that dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-4R

3.1.3.1 JAK1

JAK1 GOF disease is rare and recently described with few case reports describing an immune dysregulation disease with considerable phenotypic heterogeneity [128]. GOF variants in JAK1 promote a disease characterized by hypereosinophilia syndrome, atopy, autoimmune thyroiditis, and further multiorgan involvement [48, 49, 92, 93, 94] (Fig. 4). JAK inhibitors have been used as an effective therapy for this condition [48, 49] (Table 1).

To date, there has been one known case of human JAK1 deficiency associated with two germline homozygous missense mutations which were characterized by recurrent atypical mycobacterial infections, various immunodeficiency symptoms, multiorgan dysfunction, and high-grade metastatic bladder carcinoma [129] (Table 1). JAK1 deficiency impairs IFN-Ɣ-induced phagosome acidification and apoptosis in THP-1 myeloid cells resulting in susceptibility to mycobacterial infection [50].

3.1.3.2 JAK2

JAK2 V617F variant is a somatic GOF mutation that results in activation of JAK2 signaling and its downstream role on hematopoietic growth factor receptors which results in hematopoietic cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis [51, 52]. It is associated with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), such as polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis [102].

3.1.3.3 JAK3

Germline JAK3 GOF has been described in one family presenting with NK cell lymphoproliferation, vasculitis, CVID, autoimmunity, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy [53]. Interestingly, a heterozygous JAK3 GOF variant has also been described as an activating mutation in cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) haploinsufficiency [130] (Table 1).

JAK3 LOF genetic variants result in autosomal recessive T-B+NK- severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) due to impaired signaling through the common gamma chain (

SOCS1, an intracellular protein, downregulates cytokine signaling by inhibiting the JAK-STAT pathway [134]. SOCS1 haploinsufficiency leads to a dominantly inherited predisposition to early-onset autoimmune diseases due to cytokine hypersensitivity in immune cells [96]. Germline mutations in SOCS1 disrupt immune tolerance, resulting in impaired negative T-cell selection, defective lymphocyte apoptosis, loss of B cell tolerance, abnormal Treg function, uncontrolled T cell activation, and enhanced immune effector functions [54, 55]. This dysregulation explains the variable clinical phenotype associated with SOCS1 deficiency [54]. A case report shows a 42-year-old patient with SOCS1 responded well to tocilizumab treatment [13] (Table 1).

USP18 deficiency is a severe type I interferonopathy. USP18 downregulates type I interferon signaling by blocking JAK1 access to the type I interferon receptor [56, 57]. Clinically, it presents with perinatal-onset intracranial hemorrhage, calcifications, brain malformations, liver dysfunction, septic-shock-like episodes, and thrombocytopenia (Table 2). These features mimic congenital intrauterine infections characteristic of TORCH but without detectable infection, leading to a diagnosis of pseudo-TORCH [97] (Table 1).

Treatment with ruxolitinib led to prompt and sustained recovery in a neonate with a homozygous mutation at a crucial splice site on USP18 [56] (Table 1).

TNFSF12 genes encodes TWEAK (TNF-related weak inducer of apoptosis), a cytokine that belongs to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) ligand family [135]. Disorderinvolves the cytokine TWEAK, which signals through its receptor, FN14. TWEAK plays a role in inducing apoptosis and promoting cell proliferation and angiogenesis [136, 137, 138].

Dysregulation of TNF-related weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) and its signaling pathways has been implicated in several autoimmune and inflammatory disorders, such as SLE and RA, often presenting with symptoms like lymphadenopathy, autoimmune cytopenias, andorganomegaly [136, 137]. Its involvement in chronic inflammation and tissue damage makes it a key player in immune dysregulation [135, 136]. Only a few studies have investigated TWEAK’s role in human infectious diseases. Research shows that TWEAK expression increases in early stages of mycobacterial infections, promoting autophagy and the maturation of mycobacterial autophagosomes [136, 137, 138, 139]. Additionally, another study found elevated serum levels of TWEAK in patients with SARS-CoV-2 compared to healthy individuals [140, 141], suggesting its involvement in immune response during viral infections. In terms of treatment options, therapeutic strategies targeting the TWEAK-Fn14 (its receptor) signaling pathway are being investigated for autoimmune diseases and cancer [141, 142].

This article presents a thorough examination of inborn errors of immunity influenced directly or indirectly by apoptosis [102]—a process crucial for programmed cell death. The count of IEIs is rapidly increasing, and previously recognized immunodeficiencies are revealing atypical manifestations over time [13, 143]. ALPS serves as the paradigmatic example. Through the exploration of IEIs such as FAS deficiency, FASL deficiency, and ALPS caspase 10, this manuscript sheds light on the intricate interplay between genetic variants impacting apoptotic pathways and their consequential immune dysregulation. Additionally, ALPS mimickers, such as caspase 8 deficiency, emphasizes the diverse genetic spectrum contributing to conditions with similar clinical characteristics. Moreover, the examination of SH2DIA deficiency (XLP1) and BIRC4 deficiency (XLP2) broadens the understanding of disorders sharing ALPS-like phenotypes [12, 63]. Lastly, the elucidation of JAK/STAT proteins, particularly STAT1, as regulators of both apoptosis and immune function [144], underscores the complexity of molecular mechanisms involved in ALPS pathogenesis. This review highlights the critical role of JAK/STAT pathways in the diverse spectrum of diseases associated with IEI. By exploring the interplay between these pathways and apoptosis, the discussion provides valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms driving ALPS and related disorders. This comprehensive understanding not only deepens our knowledge of these conditions but also paves the way for improved diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

AICD, Activation-induced cell death; ALPS, Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome; CASP8, Caspase-8; CEDS, Caspase-8 deficiency state; CVID, Common Variable Immunodeficiency; DNTs, Double-negative T cells; DPM, Disabling pansclerotic morphea; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; FASL, FAS Ligand; GOF, Gain-of-function; HLH, Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; IEI, Inborn errors of immunity; IFN, Interferon; JAK, Janus Kinase; LOF, Loss-of-function; NK, Natural Killer; PID, Primary immune deficiency; RA, Rheumatoid Arthritis; RALD, RAS-associated lymphoproliferative disease; SH2DIA, SH2 Domain-containing 1A; SCID, Severe combined immunodeficiency; SLAM, Signaling Lymphocytic Activation Molecule; SLE, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; SOCS1, Silencing suppressor of cytokine signaling-1; SSc, Systemic sclerosis; STAT, Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription; USP18, Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 18; XIAP, X-linked inhibitors of apoptosis; XLP, X-linked lymphoproliferative disease.

NM: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. MG: Conceptualization, Resources, Validation, Writing—review & editing, Supervision. AXdA, IHK, MW and TS: Investigation, Writing—original draft. IHK: Table. TS: figures as well. GIK: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the final version. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.