1 Laboratory of Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Democritus University of Thrace, 68100 Alexandroupolis, Greece

2 University College London Institute for Liver and Digestive Health and Sheila Sherlock Liver Unit, Royal Free Hospital and University College London, NW3 2QG London, UK

3 Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, John Radcliffe Hospital, OX3 9DU Oxford, UK

4 Division of Clinical and Molecular Hepatology, University Hospital of Messina, 98124 Messina, Italy

5 Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, 98124 Messina, Italy

6 Department of Transplant Surgery, North Bristol NHS Trust, Southmead Hospital, BS10 5NB Bristol, UK

7 Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, North Bristol NHS Trust, Southmead Hospital, BS10 5NB Bristol, UK

8 Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) Surgery, Bristol Royal Infirmary, University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust, BS2 8HW Bristol, UK

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and the tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) play critical roles in the pathogenesis of liver diseases, particularly in conditions such as fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer. This review highlights the diagnostic and prognostic potential of MMPs, emphasizing their involvement in metastasis, de-differentiation, and hepatic cell proliferation. Utilizing advanced reporter mouse models has proven instrumental in assessing intraglandular MMP activity and predicting metastatic risks, paving the way for targeted therapeutic interventions. Current research indicates that specific MMPs and TIMPs can serve as valuable biomarkers for liver function and disease progression, although a clear consensus on their clinical utility remains elusive. Ongoing studies explore MMP-targeted therapies with potential applications in liver disease management, particularly in reducing fibrosis and enhancing liver regeneration. Future directions in this field involve elucidating the roles of MMPs in ischemia and transplantation, with the aim of improving clinical outcomes. Emerging therapeutic strategies focus on achieving a balance between MMP activity and TIMP expression to optimize liver function, highlighting the need for organ-specific targeting. Overall, this comprehensive overview underscores the importance of MMPs and TIMPs in liver function and liver disease, as well as the necessity for further research to harness their potential in clinical practice.

Keywords

- extracellular matrix

- liver physiology

- pathogenesis

- tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases

- liver biomarkers

The liver, the body’s largest gland, performs critical functions for digestion, metabolism, detoxification, and homeostasis [1]. Recent advances have enhanced our understanding of its metabolic processes, particularly the role of hepatocytes, the liver’s primary functional cells [2, 3, 4, 5]. Linking liver structure to function in health and disease is essential, facilitated by studies in animal models and humans [6, 7].

Liver diseases related to alcohol abuse, obesity, infections, autoimmune disorders, or genetics are prevalent. Conditions such as hepatitis, cirrhosis, liver cancer, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD, formerly non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD]), often tied to obesity and insulin resistance, necessitate timely diagnosis and management [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16].

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), or matrixins [17], regulate liver function by maintaining extracellular matrix (ECM) balance and enabling regeneration post-injury, though excessive activity can cause damage [18]. Dysregulated MMPs are linked to chronic liver diseases, including viral, autoimmune, and metabolic conditions, often leading to fibrosis and cirrhosis [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. Their sequence and structural similarities present challenges in developing targeted therapies, but identifying specific MMP targets shows promise for antifibrotic treatments [19, 27].

This review highlights the crucial role of MMPs in liver function, disease, and therapy.

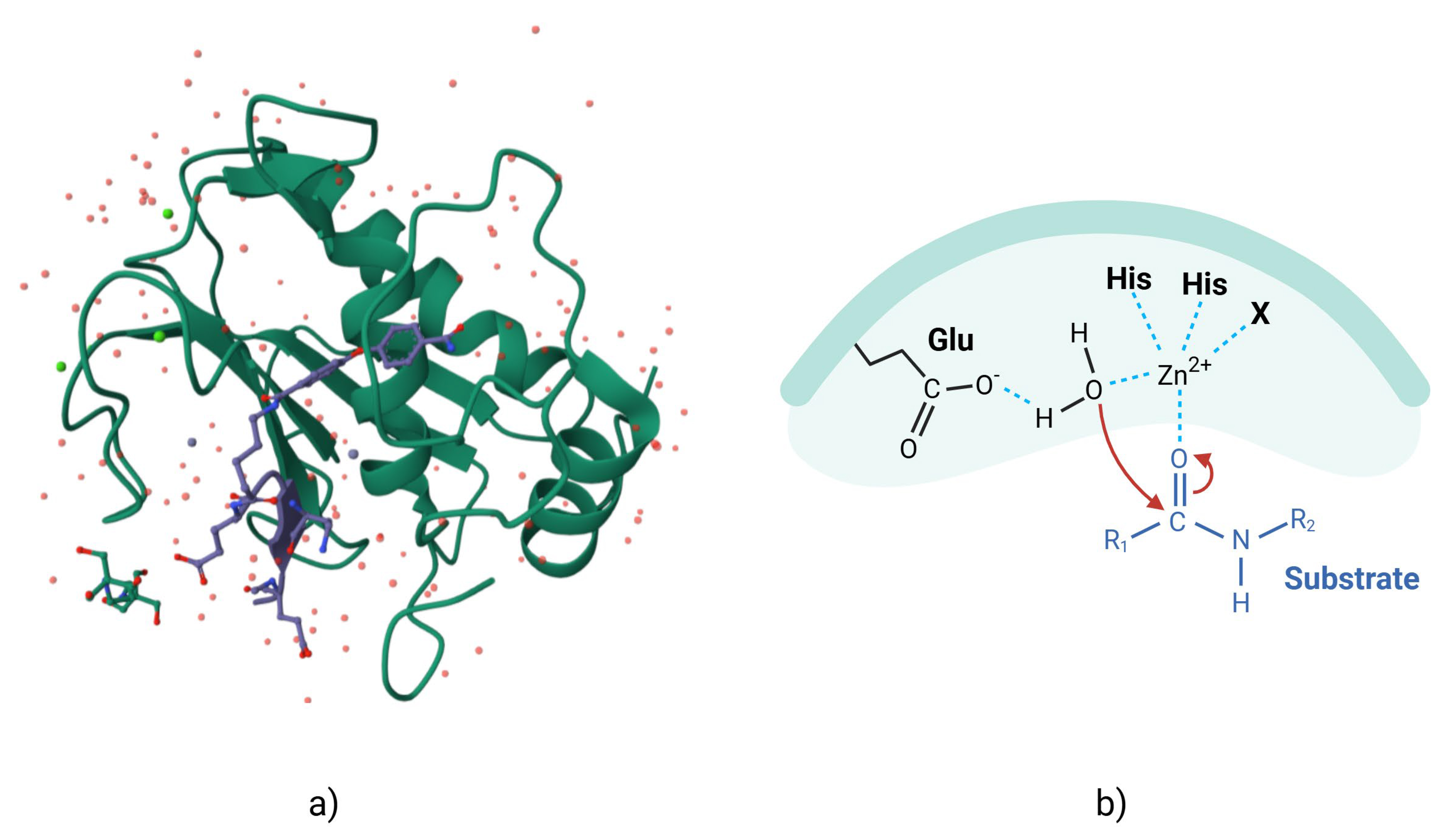

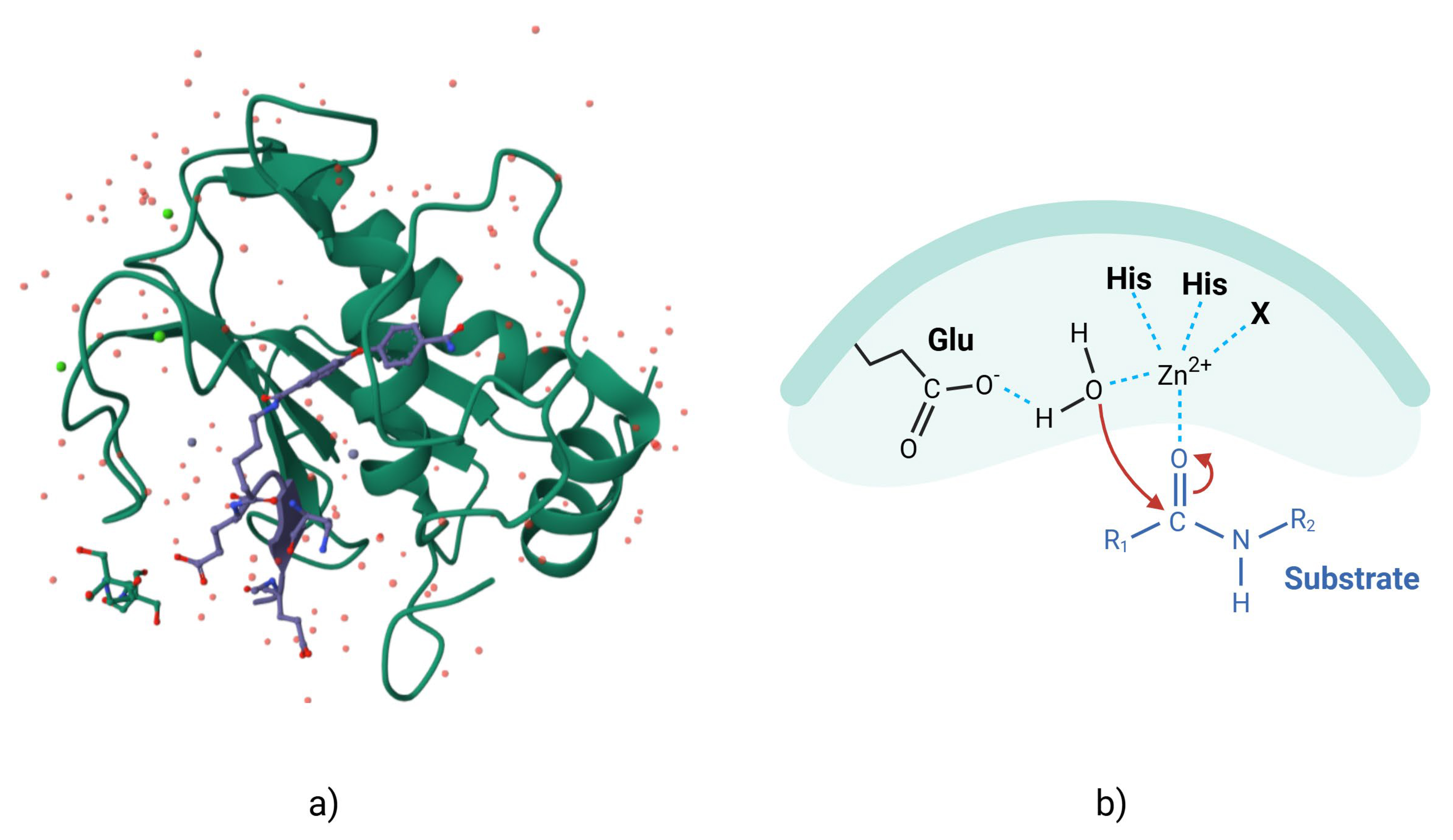

MMPs are zinc- and calcium-dependent enzymes that degrade components of the ECM. All MMPs have a similar organization, with a signal peptide, a propeptide domain, a catalytic domain, a hinge region, and a hemopexin domain [28]. The catalytic site has a conserved pattern of sequence similarity, reflecting the conservation of the MMP core structure, which contains three histidine residues that are critical for the enzyme mechanism (Fig. 1, Ref. [29]). Many MMPs have a furin cleavage site in the propeptide domain that allows activation of the zymogen, although other mechanisms are also present [30, 31, 32].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

MMP-2 with pro-domain. (a) Three-dimensional representation of surface of MMP-2 (as demonstrated in the Research Colaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB) [29], modified by Kompoura V using Biorender.com). (b) Two-dimensional structure of MMP-2, where “bait-region” are represented in blue. MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; Glu, Glutamic acid; His, Histidine.

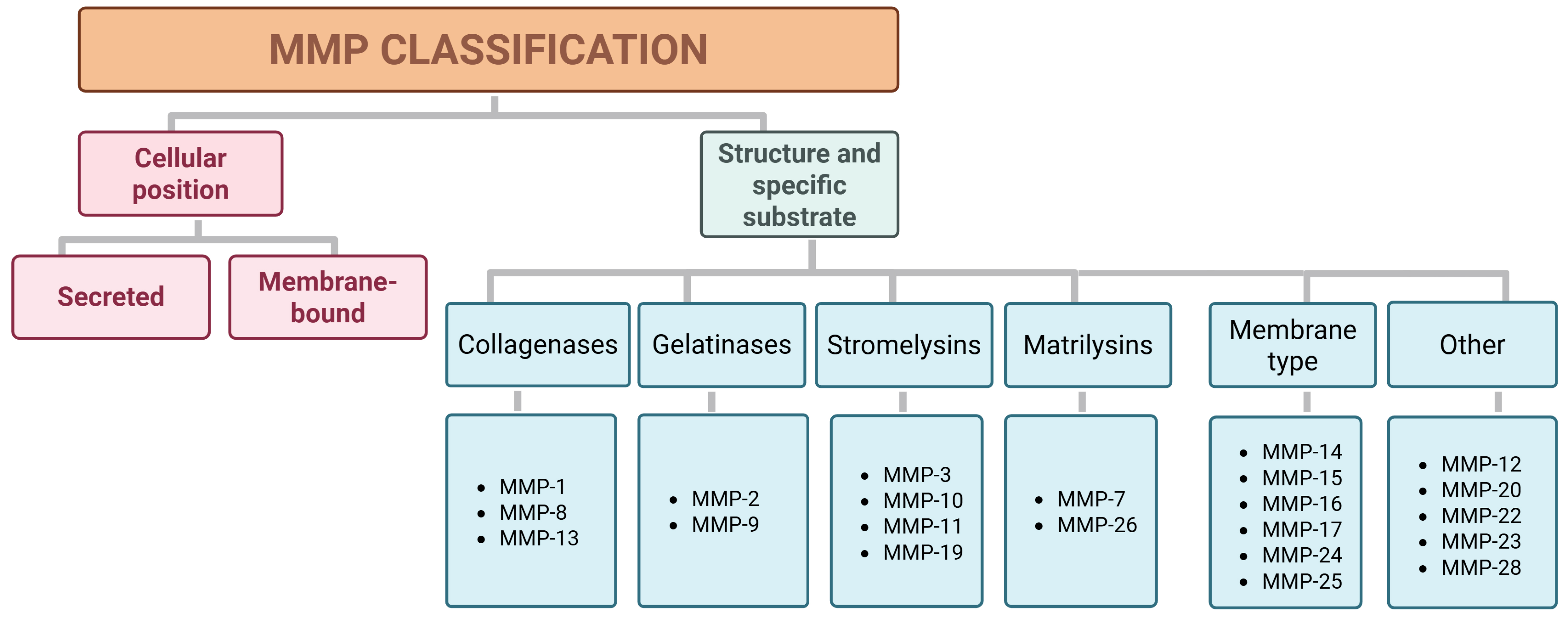

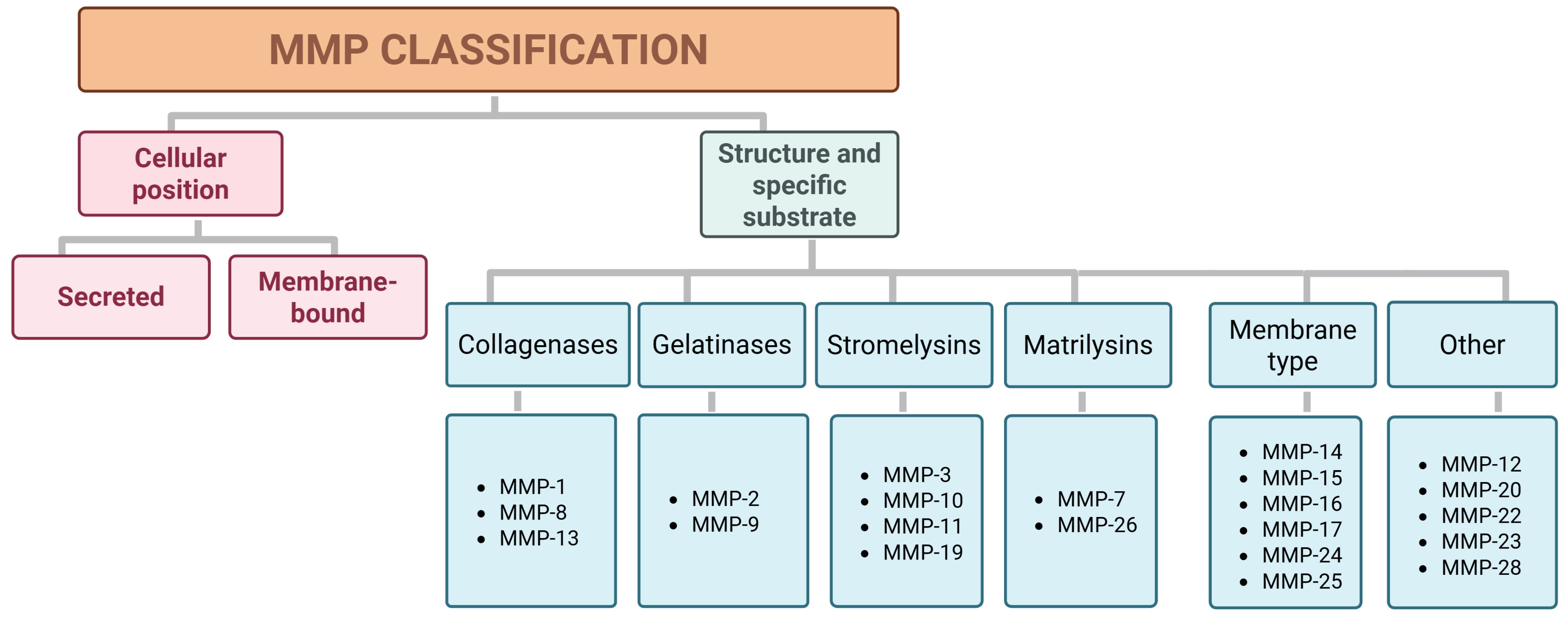

The family of MMPs consists of key regulators of the ECM that are endogenously inhibited by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) [33, 34]. It is one of the most extensively studied and well-characterized metalloproteinase families [34]. MMPs are classified into two categories based on their cellular location, i.e., secreted and membrane-bound, and into six groups according to their structure and specific substrate: collagenases, gelatinases, stromelysins, matrilysins, membrane-type metalloproteinases (MT-MMPs), and unclassified types (Fig. 2) [35, 36, 37].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Classification of MMPs found in humans according to their cellular position and specific substrate or structure. MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases.

MMPs degrade various ECM components, with evolutionary conservation in structure and function, but diverse substrate specificities influencing their roles in tissue homeostasis and disease [34, 38, 39, 40]. Collagenases and gelatinases such as MMP-2 and MMP-9, termed “neutrophil-specific” due to their expression in neutrophils, are critical in connective tissue remodeling [22, 41]. MT-MMPs, produced as inactive pro-enzymes, also act as receptors with protease activity [40]. The balance between MMP activity and ECM integrity is essential for homeostasis, and its disruptions lead to pathological conditions.

MMPs are capable of cleaving protein and non-protein substrates. In protein substrates, specific peptide sequences are recognized by the exosites on the enzyme surface, thereby determining its specificity.

MMP regulation occurs at transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and

post-translational levels. Gene expression is driven by factors such as the

signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), activator protein 1

(AP-1), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-

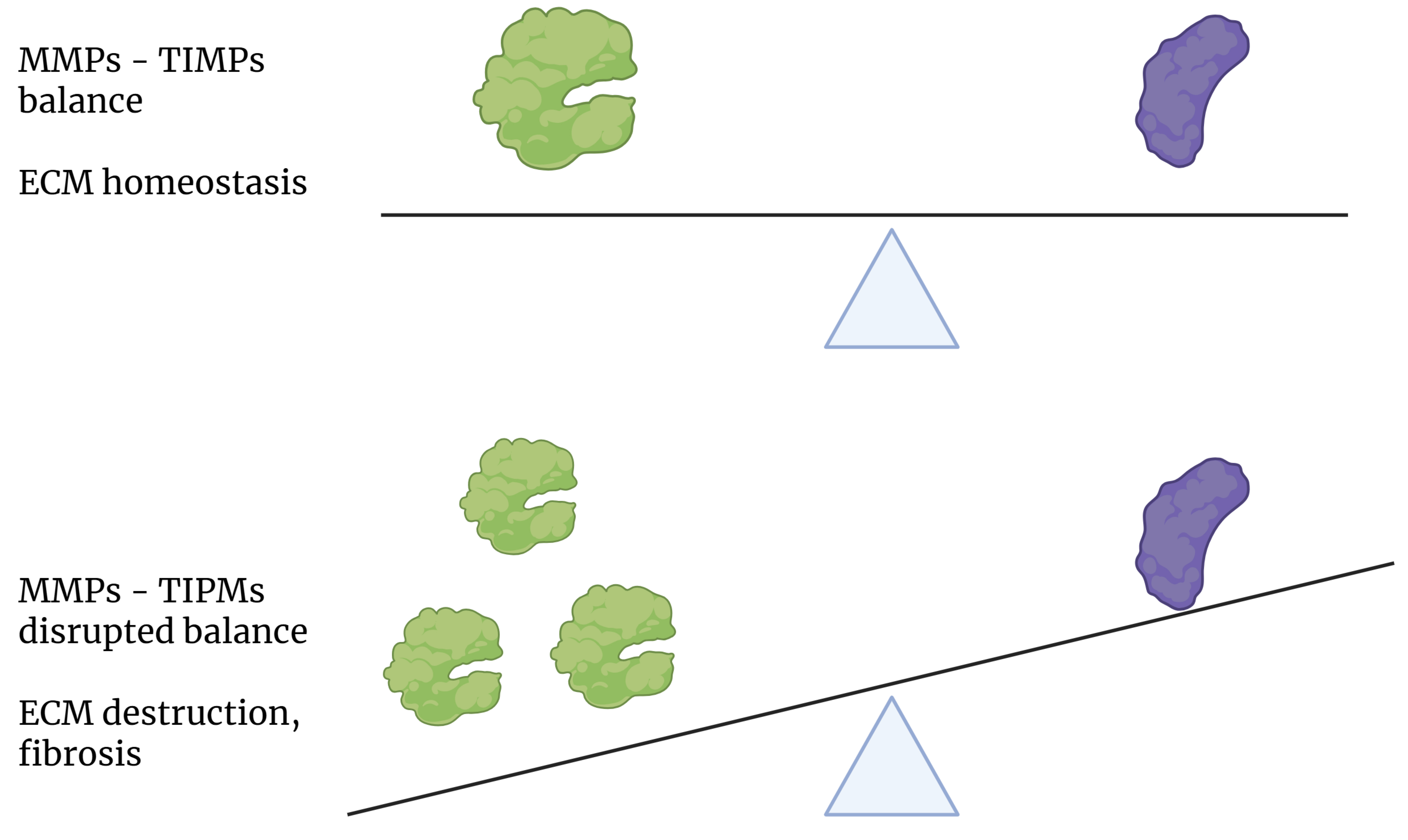

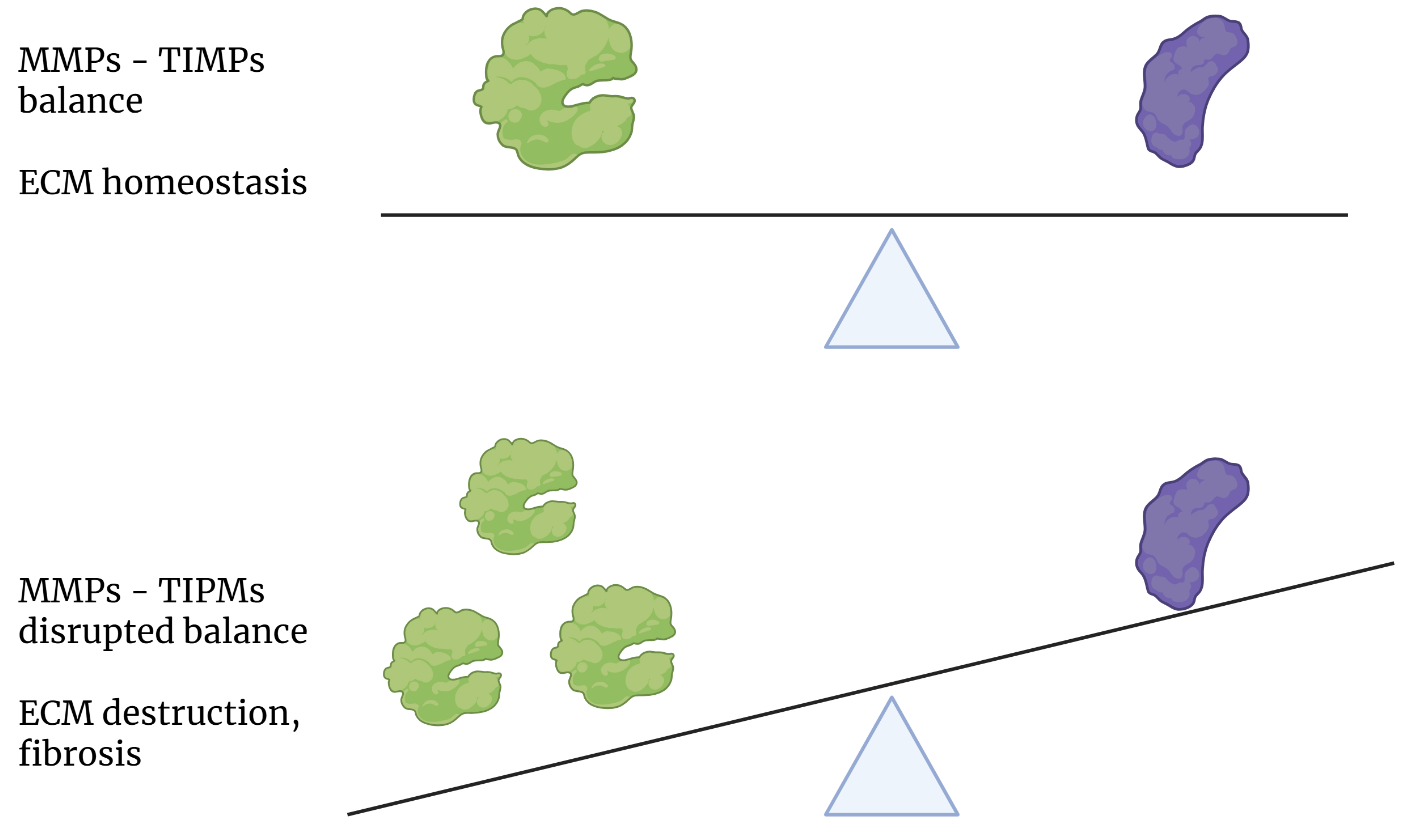

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the state of balance between MMP and TIMP expression on the homeostasis of the extracellular matrix. MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; TIMPs, tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases; ECM, extracellular matrix.

Activation involves the removal of an N-terminal propeptide, which is essential for balancing MMP and ECM activity [46, 47, 48]. Exogenous TIMPs have been used to link MMPs to tissue pathology and have aided the identification of elevated MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels in liver diseases such as fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [49, 50, 51, 52]. Although chemical inhibitors are widely used, more precise approaches, such as tissue-specific gene disruption models, enhance our understanding of the roles of MMPs [34, 50].

Tissue-specific inhibitors, guided by tissue-specific promoters, hold promise in reducing side effects. Recent mouse models with loxP-arrested MMP genes combined with Cre recombinase expression allow for precise functional studies of proteases [38, 53].

MMPs are crucial enzymes primarily responsible for degrading ECM proteins, glycoproteins, membrane receptors, cytokines, and growth factors. They are involved in key biological processes such as tissue repair and remodeling, cellular differentiation, embryogenesis, morphogenesis, cell migration, mobility, angiogenesis, proliferation, wound healing, and apoptosis. MMPs also play significant roles in reproductive events like ovulation and endometrial proliferation. However, when MMP activity is dysregulated, it can contribute to various pathological conditions, including tissue destruction, fibrosis, and weakening of the ECM [17, 37]. The main functions of MMPs are summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [7, 36, 50, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67]).

| Function of MMPs | Specific targets or processes |

| Degradation of extracellular matrix proteins and glycoproteins [36, 50, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59] | Extracellular matrix proteins |

| Degradation of membrane receptors [57, 60] | Membrane receptors |

| Degradation of cytokines [55, 57, 60] | Cytokines |

| Degradation of growth factors [55, 57, 60] | Growth factors |

| Biological processes involving MMPs | Associated activities or outcomes |

| Tissue repair and remodulation [50, 56, 57, 58, 60] | Remodeling and repair of damaged tissues |

| Cellular differentiation [50, 56] | Differentiation of cells into specific types |

| Embryogenesis [50, 56, 57, 60] | Development of embryos |

| Morphogenesis [56] | Development of tissue and organ structure |

| Cell mobility [61, 62] | Movement of cells |

| Angiogenesis [56, 57] | Formation of new blood vessels |

| Cell proliferation [56] | Increase in cell numbers |

| Cell migration [56] | Directed movement of cells |

| Wound healing [50, 56, 57, 60, 63] | Repair of tissue injuries |

| Apoptosis [56] | Programmed cell death |

| Reproductive events (ovulation, endometrial proliferation) [57, 60] | Ovulation |

| Pathological outcomes due to MMP Deregulation | Pathological group |

| Tissue destruction [7, 64, 65, 66, 67] | Excessive degradation of extracellular matrix |

| Fibrosis [7, 64, 65, 66, 67] | Excessive tissue build-up and scarring |

| Matrix weakening [7, 64, 65, 66, 67] | Weakening of structural support in tissues |

MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases.

The liver ECM is a complex and highly organized network of macromolecules that

provides structural support and regulates various cellular functions [68, 69]. In

a healthy liver, the ECM comprises less than 3% of the relative tissue area and

approximately 0.5% of the wet weight [69]. The primary ECM components in the

normal liver include collagen types I, III, IV, and V, fibronectin, laminin,

proteoglycans, and matricellular proteins. In healthy adults, there is a moderate

ECM turnover, with the constitutive expression of several MMPs, including MMP-1,

MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-8, MMP-11, and MMP-13 [70]. Specifically, MMP-1, MMP-8, and

MMP-13 have the ability to cleave interstitial collagens. MMP-1 plays a pivotal

role in the regression of liver fibrosis and has been extensively studied in

liver physiology [71]. The activity of MMP-8 is associated with ECM balancing

after cholestatic injury [72], while MMP-13 is closely correlated with

TGF-

Beyond their ECM-degrading capabilities, MMPs have other important biological

roles in the liver. For instance, MMP-2 is involved in the activation of

TGF-

Table 2 (Ref. [70, 71, 72, 73, 74]) summarizes the distinguished roles of MMPs in liver processes and ECM modulation.

| MMP | Role in the liver | Involvement in ECM | Associated liver process |

| MMP-1 [71] | Cleaves interstitial collagens | Degradation of interstitial collagen | Regression of liver fibrosis |

| MMP-2 [70] | Activates TGF- |

Degradation of basement membrane components | Fibrosis, liver homeostasis |

| MMP-3 [70] | Constitutively expressed in liver, involved in ECM turnover | General ECM turnover | ECM remodeling and turnover in healthy liver |

| MMP-8 [72] | Balances ECM after cholestatic injury, cleaves interstitial collagens | ECM remodeling after injury | Cholestatic injury response |

| MMP-13 [73, 74] | Activates TGF- |

ECM remodeling, TGF- |

Liver fibrosis, TGF- |

MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; ECM, extracellular matrix; TGF-

MMPs are vital for ECM remodeling in the liver, driving regeneration, repair,

fibrogenesis, and fibrosis resolution. They regulate ECM turnover and cellular

signaling, with MMP-1, MMP-8, and MMP-13 being pivotal in collagen degradation

and fibrosis regression. MMP-2 activates TGF-

Despite their importance, the interactions between MMPs and TIMPs, along with their precise roles in liver diseases, are not fully understood, requiring further research to unlock their therapeutic potential.

Despite acting primarily in the extracellular space, several members of this family of proteases are implicated in the pathogenesis of liver disease and regulated by hepatic protein systems [7, 77, 78].

In the liver, MMPs play critical roles in processes such as inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer, as in the case of HCC (Table 3, Ref. [37, 56, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93]) [19, 94, 95, 96]. Collagenase-related MMPs are particularly significant in liver fibrosis and wound healing.

| Liver disease | MMPs | Mechanism of action | Key findings |

| Viral hepatitis [84] | MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9 | Involved in ECM remodeling and fibrogenesis due to chronic inflammation from viral infection. | Elevated MMP levels correlate with liver inflammation and fibrosis in chronic viral hepatitis. |

| Alcohol-related liver disease [56, 79, 81, 82] | MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-8, MMP-13 | Chronic alcohol consumption leads to persistent liver inflammation and fibrosis via MMP dysregulation. | Increased MMP activity correlates with liver injury severity and contributes to the progression of liver fibrosis. Targeting MMPs may mitigate alcohol-induced damage. |

| Metabolic liver disease [80, 86] | MMP-2, MMP-9 | Implicated in the ECM remodeling associated with conditions like metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. | MMPs contribute to the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis in metabolic disorders by mediating ECM changes. |

| Ischemia-reperfusion liver injury [37, 83] | MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-14 | MMPs play a role in tissue remodeling and repair following ischemic injury in the liver. | MMP activity may be involved in the reparative processes after ischemic injury, potentially influencing fibrosis. |

| AIH [85, 87, 88] | MMP-2, MMP-9 | ECM remodeling and fibrosis progression due to immune-mediated liver injury. | Elevated MMP levels correlate with liver inflammation and injury in AIH. |

| Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis [89, 90] | MMP-2, MMP-9 | Implicated in liver inflammation and fibrosis in cholestatic disease. | MMPs contribute to ECM changes, leading to fibrosis and cholestasis. |

| Liver fibrosis/cirrhosis [80, 84] | MMP-2, MMP-9 | Regulation of ECM turnover and HSC activity during liver injury. | MMP-9 correlates with cirrhosis severity; their inhibition may reduce fibrosis progression. |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma [91] | MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9 | Degradation of ECM, promoting angiogenesis and metastasis. | Overexpression of MMPs correlates with poor prognosis and facilitates tumor growth and invasion. |

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma [92, 93] | MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-9 | Contributes to the invasive and metastatic behavior of cholangiocarcinoma. | MMPs involved in remodeling the tumor microenvironment, enhancing cancer progression. |

MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; ECM, extracellular matrix; AIH, autoimmune hepatitis.

Many liver diseases with an active inflammatory process, like viral hepatitis and alcohol-related hepatitis, show expression patterns of MMPs similar to those noted during liver regeneration and fibrosis. These observations underline that matrix proteolysis is a degradative process inextricably linked with inflammation; this warrants further investigation in pursuit of a deeper elucidation of the role of MMPs in the pathology of inflammatory liver diseases.

Increased expression of MMPs can contribute to the activation of

pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, such as the NF-

Notably, research has focused on exploring the function of intracellular MMPs, either favoring or hindering inflammation. For example, within macrophages, nuclear MMP-14 serves as a transcription factor, encouraging the expression of phosphoinositide-3 kinase-f subunit p110 and thereby regulating inflammation.

The absence of MMP-14 results in the depletion of the Mi2/nucleosome remodeling deacetylase complex, leading to increased macrophage pro-inflammatory signaling. It is noteworthy that MMP-14’s influence is not tied to its proteolytic function [98]. In chondrocytes, nuclear MMP-3 interacts with heterochromatin protein gamma, which leads to the activation of specific diseases. In reaction to ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI), MMP-2 becomes activated along with pro-inflammatory cytokines [99]. This, in turn, can stimulate the recruitment of immune cells in the liver, including macrophages and neutrophils, amplifying the inflammatory response [79, 100, 101].

Persistent tissue injury, present in the majority of chronic liver diseases, is caused by an imbalance in the turnover of ECM, leading to the build-up of collagen and the formation of fibrosis [80, 102]. Liver fibrogenesis and cirrhosis derive from the pathophysiological changes caused by liver damage. When the liver sustains an injury, activated liver cells, including hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), fibroblasts, and other cell populations, release small molecules, peptides, connective tissue proteins, and growth factors, which bind to ECM proteins and have fibrogenic activity, resulting in liver scarring and potentially progressing to cirrhosis [81, 103, 104, 105]. MMPs are responsible for the degradation of ECM proteins, and their dysregulation can contribute to their excessive deposition in the liver [79]. HSCs play a central role in orchestrating the liver’s response to different types of injury [79]. Through the use of qRT-PCR, zymography, and Western blot techniques, the release of MMP-9 from activated HSCs in both rats and humans has been detected [106, 107]. During liver injury, activated HSC increases the production of ECM components, such as collagen, while also inhibiting the activity of MMPs, leading to a net accumulation of scar tissue [82]. Several studies have extensively explored the significant alteration and modification of the main components that constitute the multifaceted ECM, which includes collagen, glycosaminoglycan, elastin, and fibronectin, in the context of liver fibrosis [78, 96, 108]. Although the initial response to injury varies depending on the etiology, the fibrotic response acquires common features at more advanced stages. These changes disrupt the normal liver architecture and have a negative impact on its function, potentially leading to liver failure and portal hypertension in the context of cirrhosis [19, 34, 78, 109].

The understanding of the impact of MMPs on cirrhosis has the potential to drive the development of new treatments for this condition. In the setting of hepatic fibrosis, MT-MMP, which are produced by various cell types such as HSC, play a key role in connective tissue metabolism, resulting in edema in the early stages and ultimately leading to a decrease in hepatocyte growth factor levels [83, 110, 111, 112]. In accordance with the critical role that MMPs play in liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, extensive research has been conducted on their potential diagnostic and therapeutic applications in this context [84, 106, 113, 114, 115]. MMPs can directly degrade collagen type IV and X, or regulate the release and/or activation of other MMPs. Among the various MMPs identified, MMP-9, primarily released by activated HSC, seems to be most strongly connected to liver injury and cirrhosis [84, 106, 113, 114, 115]. The effect of MMP-9 proteolytic activity on the ECM causes a reduction in the production of cross-linked collagen, leading to decreased tensile strength and less tissue scarring. The possibility of inhibiting MMP synthesis or activity with medications is an area of investment generating a lot of interest in the pursuit of alleviating liver fibrosis, scar formation, and subsequent liver dysfunction. Various approaches to achieving MMP inhibition are currently being explored [84, 85, 95, 116].

The confirmation of genetic variations in MMPs in chronic liver disease highlights the need for a deeper genetic characterization. Additionally, the studies of Irvine et al. [117] and Joseph [118] have led to an increased identification of patients with a pro-fibrotic phenotype.

Although MMPs show promise as biomarkers and therapeutic targets, most research in this field is preliminary. While animal studies have demonstrated promising results, translating these findings to clinical practice has proven to be difficult [119, 120, 121]. The specific links between MMP dysregulation, fibrosis progression, and liver damage are not fully elucidated. Ongoing research continues to shed light on the complex mechanisms underlying the involvement of MMPs in liver disease in pursuit of paving the way for the development of novel therapeutic strategies [19, 122]. Table 3 summarizes the involvement of various MMPs in liver diseases.

Viral hepatitis is a leading cause of acute or chronic liver inflammation and damage, affecting millions globally. To date, five main viruses have been identified: A, B, C, D, E, and G. These viruses have different patterns of spread, routes of transmission, natural histories, and clinical manifestations. While hepatitis A and E viruses are usually linked to acute hepatitis, hepatitis B, C, and D viruses can cause long-term infections that can lead to chronic liver disease, causing fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer [10, 123, 124, 125].

The clinical relevance of MMPs in chronic viral hepatitis has been investigated with both experimental and clinical observations in rodents and humans, which have shown the expression and activity of MMPs and demonstrated their pathogenetic roles in these diseases, including modification of the environment of infected hepatocytes facilitating the infiltration of inflammatory cells and, in particular, activation of HSC and progression of liver fibrosis [126, 127].

The roles of MMPs during hepatitis virus infection may vary depending on the virus’s pathogenic mechanism and the affected organs. In the classic model of concanavalin A-induced hepatitis, mice lacking MMP-9 showed impaired recruitment of CD4+ T cells and developed hepatitis with necrosis in the liver, while wild-type mice developed CD8+ T-cell-mediated hepatitis. In models of hepatitis virus infection, it was found that mice lacking MMP-9 were protected from inflammatory disease in other organs, such as the brain, suggesting that MMP-9 induction was essential for the development of inflammation and subsequent tissue damage [128, 129].

MMPs have been studied in animal infections and acute liver injury caused by a mouse hepatitis virus (MHV). MMP-3 and MMP-7 were detectable within 6 hours in the serum of the infected mice. Both MMPs peaked at 10 to 12 hours and returned to pre-treatment levels at 48 hours. This was associated with reparative regeneration, increased hepatocyte mitosis, and DNA synthesis [130].

There is compelling evidence that infection with the oncogenic (hepatotropic) polyomavirus M2-7 induces acute hepatitis with massive liver necrosis after 6–14 days of incubation [131]. Extensive enzymatic and histopathological studies [132, 133, 134] correlated with hepatic matrix remodeling have been conducted, including the determination of pro-MMP-2, pro-MMP-9, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), urokinase (uPA), and their inhibitors [135]. The immunoreactivity of MMP-2 and MMP-9 initially localized in hepatocytes resulted in their injury or apoptosis, followed by infiltration of macrophages and NK cells. In chronic hepatitis, S. and T. typhimurium infections caused a profibrogenic profile, activating HSC and increasing collagen fiber deposition, as well as significantly enhancing the MMP-2/TIMP-2 ratio. The induction of MMP-3 and MMP-9 was supported by the elevation of serum transaminases and hepatic necrosis due to drug and infection. Elevated levels of serum MMPs indicated either residual activity of these MMPs or ineffectiveness of their inhibitors, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), in the progression of liver disease [136, 137]. Pro-MMP-9 exhibited a direct correlation with hepatic parenchymal damage, as its levels significantly increased in the early stages and increased with the progression of liver damage, while MMP-2 had an indirect relationship, being associated with later liver cirrhosis [138].

Notably, MMP-9/TIMP-1 levels were significantly reduced in patients with hepatitis C following treatment with direct-acting antiviral, suggesting that this complex could be used as a biomarker of active fibrogenesis [84]. Another study assessing the production, activity, and regulation of MMPs in liver fibrosis stages in chronic hepatitis C revealed that the serum levels of MMP-2, -7, and -9 were higher in chronic hepatitis C patients than in healthy subjects, with MMP-7, in particular, distinguishing early and advanced stages of fibrosis [139].

To date, there has been no research conducted on the structure and composition of the matrix in tissues or cultures that have been infected with hepatitis viruses. Current research is limited by insufficient studies on the structural and compositional changes of the ECM in the context of hepatitis virus infections; such changes are key to understanding the relationship between matrix remodeling and disease progression. Existing animal models do not effectively replicate chronic hepatitis or sustain productive viral infections over time, hindering research into the long-term effects of MMPs on liver fibrosis. In vitro cell culture systems also face challenges in maintaining a differentiated phenotype and supporting productive hepatitis virus infections. These limitations impede a full understanding of MMP dynamics, their regulatory mechanisms, and their potential as therapeutic targets for chronic liver diseases caused by viral hepatitis. Potential future directions for research include understanding changes in the ECM during viral infection, enhancing animal models for viral hepatitis, investigating the interactions between MMPs and specific hepatitis viruses, and evaluating the impact of antiviral therapies on MMPs.

Excessive ethanol consumption can lead to alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), which is characterized by steatosis and inflammation and can progress toward fibrosis and cirrhosis. Disruptions in gut microbiota, increased intestinal permeability, and inflammatory immune response play a central role in the development of ALD. In 2020, alcohol consumption contributed to 1.38 million deaths, making ALD the sixth leading cause of premature death globally [140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145].

Ethanol metabolism increases reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, contributing to liver damage through oxidative stress and lipid metabolism disruptions and steatosis. ALD progression involves ECM remodeling and an imbalance in MMPs, including MMP-9 and collagenases (e.g., MMP-1, -8, -13). Despite known roles in fibrosis development, the precise regulation and activation of MMPs in ALD remain unclear [95, 146, 147]. A study examined the role of MMPs/TIMPs in liver remodeling in a rat model of ALD after 9 weeks of ethanol consumption [148]. Ethanol increased TIMP levels and decreased MMP levels, leading to the accumulation of ECM proteins and liver fibrosis. Inhibition of MMP activity with the broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor BB-94 resulted in more severe liver damage and inflammatory cell infiltration, suggesting a protective role of MMPs in ALD. MMP-2 was identified as a key mediator in protecting against chronic ALD-related liver injury [35, 84, 106, 149, 150, 151, 152].

Despite the significant knowledge of the disease’s underlying molecular mechanism, the therapeutic options targeting oxidative stress, gut-liver axis disruptions, and ECM remodeling are limited, highlighting the need for further research in this field [106, 151, 153, 154, 155].

The accumulation of MMP-9 in inflamed regions of steatotic livers and its induction through the ERK/MAP kinase pathway in rat HSCs has been observed, highlighting its role in modulating ECM turnover in chronic alcohol-related liver disease [107, 148]. Collagen accumulation in the liver was confirmed by the ingrowth of polymerized collagen fibers and an abundance of ES-myofibroblastic HSCs, and activated collagen-producing myofibroblasts (MFBs) in rats exposed to ethanol. An increased collagen turnover leading to the accumulation of desmoplastic and irregular collagen deposits in the periportal areas and in the sinusoids surrounding necrotic HSCs and Kupffer cells was also observed [148].

Sera of patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis exhibit an abundance of high

molecular weight gelatinolytic proteins, likely zymogenic MMPs, which is

associated with a reduction in trypsin-activatable MMPs [156]. It was found that

TNF-

Despite the findings on the potential role of pro-MMP-9 in fibrosis initiation, gaps remain in understanding its activation dynamics, regulatory mechanisms, and therapeutic potential. Additionally, abnormalities in collagen turnover, the roles of other MMPs, and the link between matrix proteolysis and inflammation in chronic inflammatory liver diseases require further investigation.

MASLD has become one of the most prevalent chronic liver diseases globally, largely due to rising obesity rates. The term has been recently updated from NAFLD to better reflect the disease’s association with metabolic dysfunction and avoid stigmatization. MASLD is defined by hepatic steatosis and at least one of the following cardiometabolic risk factors: overweight/obesity, type 2 diabetes or pre-diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, in the absence of other discernible causes [13]. Despite its association with metabolic syndrome and obesity, up to 25% of patients with MASLD have a normal body mass index (BMI). Patients with MASLD with or without increased BMI often do not show any symptoms or signs of liver disease.

MASLD is characterized by the accumulation of fat within hepatocytes, which leads to inflammation, fibrosis, and, potentially, the development of cirrhosis and liver cancer [160, 161, 162].

Emerging evidence suggests that MMPs may contribute to the pathogenesis of metabolic liver disease [19, 163]. In fact, increased expression and activity of MMPs have been observed in clinical studies of MASLD and metabolic-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) [160, 161, 162]. Although the pathogenesis of MASLD is not fully understood, the most recent literature hypothesizes the need for two “hits”, for the initiation and progression of the liver disease. The insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis caused by an excess of fatty acids and subsequent accumulation of lipid droplets in hepatocytes leads to a “first hit”, usually heightened by genetic variants. Next, a “second hit” is thought to occur due to oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, inflammation, and fibrosis, leading to pathological changes in hepatocytes [164, 165].

As in other chronic liver diseases, activated HSCs produce an excess of ECM

components, including type I and III collagen, proteoglycans, and elastin, as

well as TIMPs (TIMP-1 and -2). The TIMPs inhibit MMPs (MMP-2 and MMP-9), which

are involved in preventing liver fibrosis. MMP-2 can break down fibrous

collagens, while MMP-9 plays a role in reversing liver fibrosis, although its

exact mechanism is not fully understood [20]. The activation of TIMPs disrupts

the balance between metalloproteinases and inhibitors, leading to collagen

deposition and alteration of the ECM architecture. Increased pro-MMP-2 and active

MMP-2 indicate continuous matrix remodeling even in advanced liver fibrosis,

suggesting potential reversibility [148, 166, 167]. The deposition of ECM

proteins in the Disse space results in increased stiffness and density of the

ECM, leading to the formation of scar tissue. Patients with advanced

MASLD-associated fibrosis exhibit elevated levels of

While there is currently no concrete experimental proof supporting the involvement of MMPs or TIMPs in the development and advancement of hemochromatosis, it appears that MMPs (specifically MMP-2 and MMP-9) may have a role in the progression of Wilson’s disease. Wilson’s disease is a disorder characterized by excessive accumulation of copper in the body that affects multiple systems and can, therefore, lead to multiple clinical manifestations, including liver failure. It was observed that levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were higher in patients with Wilson’s disease compared to normal controls and were inversely correlated with Cp [171].

While the precise mechanisms by which MMPs contribute to the development and progression of metabolic liver diseases are not yet fully understood, the available evidence suggests that these enzymes play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of these conditions. Targeting MMPs and their associated signaling pathways may represent a promising therapeutic avenue for the management of metabolic liver diseases, potentially leading to improved clinical outcomes for affected patients.

Autoimmune and cholestatic liver diseases, including autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), are complex and multifaceted conditions characterized by immune-mediated injury to the liver [172, 173]. While inflammation and tissue damage are predominantly driven by cellular effectors of the immune response, including CD4+ and CD8+ subsets of lymphocytes, macrophages, and NK cells, the role of cytokines that regulate cellular immunity, cell signaling molecules, extracellular mediators, including MMPs, has been studied. As in other chronic liver diseases, MMPs have been implicated in both the inflammatory and fibrotic processes of these conditions and are likely to contribute to the progression of liver injury and the development of cirrhosis. For instance, the concentrations of MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-13, and MMP-14 were notably diminished in the livers of cholestatic rats, which resulted in a decreased degradation of type I collagen, indicating an abnormal turnover of this protein [174]. While MMPs appear to contribute to ECM remodeling and immune signaling in autoimmune and cholestatic liver pathology, studies in this specific subset of chronic liver disease are insufficient, and the precise mechanisms underlying their involvement in the pathogenesis and progression of these diseases remain inadequately understood.

Primary liver cancer, encompassing mainly HCC and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, is a significant global health concern, with rising incidence and mortality rates worldwide [175]. Understanding the underlying mechanisms and the role of key molecular players, such as MMPs, is crucial for the development of effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. MMPs have been heavily implicated in the progression and metastasis of various cancers, including hepatic carcinoma [175]. Chronic liver disease, including ALD, MASLD, chronic HBV, or HCV infection, usually precedes this type of cancer, with liver cirrhosis being the major risk factor. The progression of pathophysiological changes, tissue and inflammation response, as well as fibrogenesis, contribute directly to the initiation and progression of HCC. The altered ECM not only disrupts normal liver architecture, but also provides a permissive environment for the development of cellular dysplasia and cancer [175]. MMPs have been implicated in the progression of fibrosis to HCC, as they can promote angiogenesis, tumor growth, and metastasis [176] and are overexpressed in chronic liver diseases and HCC. In human HCC specimens, several MMPs, including MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, and MMP-9, have been reported to be up-regulated [177, 178]. Importantly, overexpression of these MMPs is generally associated with worse patient outcomes [92, 178]. Many of these MMPs activate growth factor precursors or shed membrane-anchored growth factors, altering growth factor concentrations in the liver environment to promote cell growth and survival [92, 178, 179]. The expression of MMPs is not limited to the tumor cells themselves, but also involves the complicit stromal cells within the TME, further highlighting the complex interplay between the different cellular components in driving cancer progression [180, 181].

The hallmarks of cancer metastasis, such as the breakdown of cellular junctions, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and invasion of the ECM, are all processes that are heavily influenced by the activity of MMPs. A study demonstrated that the dysregulation of MMP expression and activity is a common feature in primary liver cancers, contributing to the increased invasiveness and metastatic potential of these tumors [182]. For instance, MMP-9, also known as gelatinase B, has been strongly associated with aggressive and metastatic behavior in various cancers, including breast cancer and HCC [183]. Interestingly, MMPs can also indirectly contribute to metastatic processes by remodeling the ECM and releasing soluble factors that can help establish a favorable niche for metastatic colonization in distant organs [180, 181, 183]. Furthermore, the variation in the expression and activation of numerous proteins involved in the metastatic process, including epithelial–mesenchymal transition markers and cancer stem cell markers, may be the reason why therapies targeting specific proteins have not been as effective in treating metastatic HCC [184]. Collectively, MMPs are thought to contribute to various cancerogenetic mechanisms and thus have the potential to serve as therapeutic targets. However, unfortunately, the results of MMP inhibitors in clinical trials have not been promising to date [185, 186].

The multifaceted role of MMPs in HCC progression underscores the need for a deeper understanding of their interactions within the TME. While MMPs are implicated in ECM breakdown, angiogenesis, and metastasis, contributing to poor outcomes, their complex roles in altering the ECM and promoting metastasis remain incompletely understood.

Despite their potential as therapeutic targets, clinical trials with MMP inhibitors have had limited success, likely due to the heterogeneity of MMP expression and involvement in diverse metastatic pathways. The challenges in effectively targeting MMPs highlight the need for further research to elucidate their precise roles and refine treatment strategies in HCC.

Liver ischemia, a condition characterized by the impairment of blood flow to the liver, for example, during vascular occlusion time/induced ischemia in the context of liver resections, or as a consequence of severe hypotension, has been the subject of extensive research in the field of hepatology, liver surgery, liver transplantation, and liver trauma. A critical component of the pathophysiology underlying this condition is the dysregulation of MMPs [167]. It is not uncommon in resectional liver surgery to apply periods of temporary occlusion of the hepatoduodenal ligament/portal triad (which contains the portal vein, proper hepatic artery and bile duct), known as Pringle’s maneuver, usually of 10–20 minutes, to allow progression of the resection with reduced blood loss, followed by periods of withdrawal of the vascular occlusion, usually of 5–10 minutes, until the resection is completed. Such ischemia–reperfusion procedures generate ischemia, subsequent hypoxia, and the production of ROS [37]. When liver tissue is deprived of oxygen due to reduced blood flow, the production of macrophage-derived MMP-2 and MMP-9 is induced, leading to remodeling/degradation of the ECM [187]. Furthermore, MMP-14 seems to play a pathophysiological role in the development of ischemia–reperfusion liver injury, as the application of ischemia–reperfusion results in a significant increase of its expression in the liver parenchyma, as observed in an experimental rat model [37].

The relationship between MMPs and ischaemic liver injury is further complicated by the involvement of other signaling pathways. For instance, the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzyme has been shown to regulate the expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 [188]. It has been described that a polymorphism in the COX-2 gene may serve as an inherited protective factor against myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, potentially by modulating the activity of MMPs [188]. This may also suggest that the regulation of MMPs could play a role in the protective mechanisms against ischaemic liver injury.

The precise regulatory pathways, the interplay between MMPs and other signaling mechanisms in ischemia–reperfusion liver injury, and their therapeutic targets remain incompletely understood, highlighting the need for further research in this field.

In the context of liver disease, MMPs have emerged as promising biomarkers due to their involvement in the pathogenesis of various conditions. As already mentioned, the imbalance between MMPs and their inhibitors can lead to excessive ECM degradation, which is a hallmark of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis [189, 190].

Currently, the most common strategy to inhibit MMP is to generate TIMPs. MMPs

uniquely require a second zinc atom to function, and the specificity of the

activation of this zinc atom for MMPs is used to design molecules that will

inhibit the activity of a specific MMP subtype. TIMPs are generally considered to

be broad-spectrum inhibitors that interact with active and pro-MMP forms.

However, the activation of MMP-2 by MT1-MMP is thought to be relatively

insensitive to TIMP-2, which has become an attractive target for anti-MMP

therapy. Moreover, because the activation of latent TGF-

Several strategies, such as gene transfer of TIMPs by liver tissue, the systemic application of recombinant TIMP variants, or a direct block of MT1-MMP, have been tested successfully in delivering improved disease outcomes in models of hepatic fibrosis [19]. Several studies have also shown promising results suggesting that the natural inhibitors of TIMPs may be beneficial in liver injury and fibrosis [19, 70, 193]. However, as most TIMPs, such as TIMP-1, are induced in response to hepatic injury and are essential for the resolution of the disease, a suitable balance with their downregulation to promote liver regeneration would be desirable, where applicable [194, 195].

In recent years, there has been significant interest in the identification of MMPs as specific markers for liver function, damage, or rates of fibrosis progression in patients with liver disease. It has been reported that MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-12, and MMP-19 are indeed upregulated in hepatic fibrosis post-liver injury [19]. However, there is currently no single MMP formally approved as a biomarker for liver fibrosis. Indeed, systematic reviews have determined that only MMP-7, MMP-9, MMP-13, and TIMP-1 could aid in detecting significant fibrosis as well as determining the activity of liver fibrosis [19, 196].

Research suggests that MMPs hold great promise as biomarkers for a variety of liver diseases, particularly those involving fibrosis, cirrhosis, and cancer. Further research is needed to elucidate the specific roles of different MMPs in liver pathology and to establish their clinical utility as diagnostic and prognostic tools.

The observed connections of various MMPs with metastasis, de-differentiation, and proliferation in hepatic cells, as well as the role of TIMP-1 in regeneration and angiogenesis, suggest that their expressions could serve as valuable diagnostic and prognostic indicators. Highly specific reporter mouse models utilizing the albumin promoter for zonal hepatocytes, the cerulein-related serine protease inhibitor (CRSPI)-1 promoter for proliferative hepatocytes, and the Thy1.2 (CD90) promoter for oval cells are instrumental in assessing intraglandular MMP activity and predicting metastatic potential, thus aiding in the development of targeted therapeutic measures.

It is important to note that MMP-targeted therapeutics have advanced to clinical

trials for cancer treatment, and further progress may lead to treatments for more

challenging hepatological conditions [64, 197]. By integrating precise product

function into the complex metabolic, inflammatory, and cancerous pathways of

these conditions, there is substantial potential for improved co-therapy without

the need for excessively negative or inhibitory effects, similar to current

practice in cirrhosis therapy with selective

Understanding MMPs and TIMP-1, alongside the utilization of targeted reporter mouse models, could revolutionize early detection, prognosis, and the development of tailored therapeutic interventions in the field of hepatology. This promising approach holds the potential to enhance patient outcomes and transform the management of hepatic diseases [64].

Remarkably, utilizing ROC analysis revealed that optimal significance for diagnostic benefit was seen for elevated levels of three markers in the AST to platelet ratio index (APRI), fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) and enhanced liver fibrosis test (ELF) panels, which are largely specific for downregulation of hyaluronic acid (HA)-binding protein (glyceronephosate O-acyltransferase (GNPAT)), only mildly correlated with MMP-7 [200, 201, 202]. Similar data were published in different age and sex (pending) groups. Certainly, the clear disadvantage of relying on individual cytokine measurements is that the popular term “the more, the better” often comes to mind, due to strong correlations with key effector monocyte-derived cytokines. To that end, accurate, detailed reviews of significant MMPs and the proteins encoded by their collocating genes may inform biomarker development in liver fibrosis for more accurate diagnosis and treatment options [202].

Although MMPs and TIMPs play critical roles in multiple physiological and pathological processes, showing promise as diagnostic and prognostic markers in hepatic diseases, challenges persist in their clinical application therapeutic targeting of individual MMPs may lead to off-target side effects limiting their therapeutic utility. Diagnostic tools, such as APRI, FIB-4, and ELF panels, are useful but overly reliant on individual cytokine measurements, which may yield inaccurate results. Research to study the complete regeneration of MMPs would be of benefit in developing new therapeutic approaches to treat liver diseases.

A deeper understanding of specific MMP roles, their associated genes, and their involvement in liver fibrosis is required to improve biomarkers and therapies. Optimizing MMP inhibitors to minimize adverse effects while maximizing efficacy remains a key challenge, highlighting the need for continued research to enhance clinical outcomes.

The widely differing incidences of different types of cancer in human populations mean that the backgrounds, genetic vulnerabilities, and lifestyle factors of patients who are diagnosed with different diseases vastly vary from one another. Therefore, it is no surprise that the most effective strategies for the exploitation of MMPs for therapeutic advantage are often governed or influenced by those same factors. Indeed, entire tumors, their cells, or metastases that may all benefit from manipulation of MMPs are extremely diverse, yet the different extracellular matrices that are targets for MMPs are equally specialized, and a patient’s MMP activity levels and susceptibility to unwanted effects are also specific to their background and the stage of disease that they suffer from.

As it is now recognized that MMPs have an increasingly common role in liver disease and metastatic spread from liver cancer, interest in the potential of targeting these proteases to benefit patients is growing. This area of research is likely to continue to expand. The brief information provided here in relation to this topic is a glimpse of current strategies and emerging new targets.

As already highlighted, with the current understanding of the various roles played by MMPs in liver fibrosis, there are potential therapeutic approaches that could be explored. One such approach would involve intervening in the enzyme activity to counteract the harmful effects of MMPs. However, there are limited ongoing investigations in animal models or clinical trials focused on the role of MMPs in liver fibrosis. Therapeutic targets for stopping or reversing fibrosis could include MMPs or their regulation. The potential benefits of an MMP inhibitor would only be realized in the presence of ongoing activation of HSC and the synthesis of ECM. It has been observed that protection from the effects of MMP inhibitors is more likely in patients with slow rather than rapidly progressing fibrosis [203]. As the use of MMP inhibitors is recommended only in the early stages of fibrosis without clinical target organ damage, this may mitigate the typical consequences of MMP inhibitor treatment failure. A deeper understanding of the complex interplay between MMPs and TIMPs is essential for the development of improved MMP-targeted therapies for hepatic diseases [19]. Furthermore, the importance of multiple types of MMPs during different phases of liver ischemia and reperfusion needs to be examined critically, and the underlying cellular substrates investigated. This knowledge will help identify new therapies that both reduce IRI and also promote liver regeneration to accelerate the recovery process [197, 204].

An understanding of the roles of MMPs in liver functions after liver transplantation or injury remains relatively poor. What is known to date is that elevated levels of MMP-8 and MMP-9 have been found in biopsies of fibrotic liver grafts following living donor-related liver transplantation. Improved translation of MMP biology to adult liver transplantation may be obtained by a better understanding of how warm and subsequent cold ischemia affect the expression of both MMPs and TIMPs, and whether differences exist between subpopulations of cells within the liver. Such differences might include differences between hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, or endothelial cells, as well as differences in separate zones of oxygen exchange (e.g., periportal or central portal tracts). This information may allow targeted treatment of different cell types or liver zones with drugs to reduce IRI. Such drugs might enable not only improved transplant outcomes but also allow the utilization of livers that may appear marginal, thus potentially increasing the pool of livers available for transplantation. The development of small molecules, natural products, or other targets that might inhibit several types of MMPs at different time points after liver transplantation could enhance the recovery from liver IRI and liver regeneration [66, 69, 195, 197, 204]. Finally, would it be possible that the MMP distribution changes request so that instead of using a small molecule or natural melanin to block the action of various agents, direct transplantation of a cell/tissue engineering product that contains intact MMPs expression (e.g., liver spheroids, microtubule, or bioprinted liver) might be a more precise therapeutic option providing in situ a functional structure for the restoration of liver integrity?

The complexity of MMP–TIMP interactions presents a significant challenge in therapeutic strategies for liver diseases. MMPs and their inhibitors, TIMPs, are involved in a delicate balance that regulates ECM turnover, with dysregulation contributing to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Despite advances, selective targeting remains difficult due to the overlapping functions of MMPs and TIMPs in various tissues and disease stages. Future research should focus on identifying specific MMPs and TIMPs that play key roles in liver pathogenesis and developing targeted therapies, such as small molecule inhibitors or gene therapy approaches, to enhance precision in treatment.

MMPs play a pivotal role in regulating the functions of primary liver cells and are integral to both physiological processes and the pathogenesis of liver diseases. Their dynamic involvement in ECM remodeling and cellular signaling underscores their significance in maintaining liver architecture and function. Given the profound impact of MMPs on liver health, further studies are essential to elucidate in detail their specific roles in various liver disease models and to translate this knowledge into clinical applications.

To harness the therapeutic potential of MMPs, a more organ-specific approach to MMP inhibition is necessary. This involves optimizing the interactions between MMPs and TIMPs to achieve desired therapeutic outcomes. By strategically targeting MMP activity, we can enhance tissue stability and protect against excessive ECM degradation, which is often observed in liver diseases.

The complexity of TIMP–MMP interactions further emphasizes the need for tailored therapies that can selectively modulate MMP activity. While several selective TIMPs have entered clinical trials in recent years, achieving a therapeutic balance that maximizes liver protection while minimizing adverse effects in other organs remains a significant challenge.

Ultimately, advancing our understanding of MMPs in the context of liver disease is crucial for the development of targeted therapies that improve liver function and patient outcomes. By focusing on the multifaceted roles of MMPs, we can pave the way for innovative strategies that not only mitigate liver injury but also promote recovery and regeneration in affected patients.

GM and VK drafted the original manuscript, did the main literature search, the analysis and interpretation of data; VK created the artwork; GM created the Tables and made critical revisions; FS and VKM did further literature search and made critical revisions; VKM conceptualized, designed and supervised the study. All authors prepared the final draft and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.