1 Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Brain Disorders & Institute of Basic and Translational Medicine, Xi’an Medical University, 710021 Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

2 Engineering Research Center of Brain Diseases Drug Development, Universities of Shaanxi Province, Xi’an Medical University, 710021 Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

3 Center for Blockchain & Healthcare Service, Xi’an Medical University, 710021 Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease which significantly and negatively affects families and society. Aerobic exercise serves as a non-pharmacological strategy, potentially safeguarding against cognitive decline and lowering the risk of AD. However, how aerobic exercise ameliorates AD remains unknown. This study investigated the effects of two types of aerobic exercise, including aerobic interval training (AIT) and aerobic continuous training (ACT), on cognitive and exploratory function, brain histopathology, and hepatic amyloid beta (Aβ) clearance in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 double transgenic (APP/PS1) transgenic mice.

Twenty-four six-month-old male APP/PS1 transgenic mice (body weight: 20–22 g) were used to establish the AD model. APP/PS1 transgenic mice were randomly assigned to one of the three groups: rest (AD group, n = 8), aerobic interval training (AIT group, n = 8), and aerobic continuous training (ACT group, n = 8). The exploration ability and anxiety of AD mice were measured using the open-field test. Learning and memory of AD mice were detected using the novel object recognition test, Y-maze test, and Morris water maze test. Neuronal damage was analyzed using hematoxylin and eosin staining and Nissl staining. Aβ deposition in the brain was detected using a thioflavin-S fluorescence assay and immunofluorescence. The mechanisms underlying hepatic Aβ clearance were investigated using an immunofluorescence assay and western blotting. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, and p < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

The results revealed that both AIT and ACT improved the recognition memory and exploration ability of mice after 8 weeks of intervention. Additionally, both forms of aerobic exercise significantly mitigated neuronal damage and Aβ deposition in the brain and improved the hepatic clearance of Aβ.

Our findings indicated that AIT and ACT can improve cognitive deficits in APP/PS1 mice, potentially by increasing the hepatic phagocytic capacity of Aβ. Hepatic clearance of Aβ may serve as a supplementary mechanism by which aerobic exercise can improve AD.

Keywords

- Alzheimer’s disease

- aerobic exercise

- Aβ clearance

- hepatic phagocytosis

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, characterized

clinically by memory loss, cognitive dysfunction, language impairment, and other

neuropsychiatric symptoms [1, 2, 3, 4]. Epidemiologic studies have revealed that the

prevalence and mortality rate of AD are increasing rapidly, which imposes medical

and financial burdens on societies worldwide [5]. The buildup and clustering of

amyloid beta (A

Accumulating evidence has shown the preventive and healing benefits of physical

exercise [10, 11]. Based on epidemiological studies, regular physical exercise can

improve cognitive function in individuals with AD [12, 13]. Additionally,

participation in aerobic exercise can enhance cognitive abilities among elderly

individuals with cognitive impairment and dementia, and animal studies have

suggested it may decrease A

Recent studies have demonstrated that A

Hence, this study aimed to investigate the effect of various types of aerobic

exercise on cognitive and exploratory functions, brain histopathology, and

hepatic clearance of A

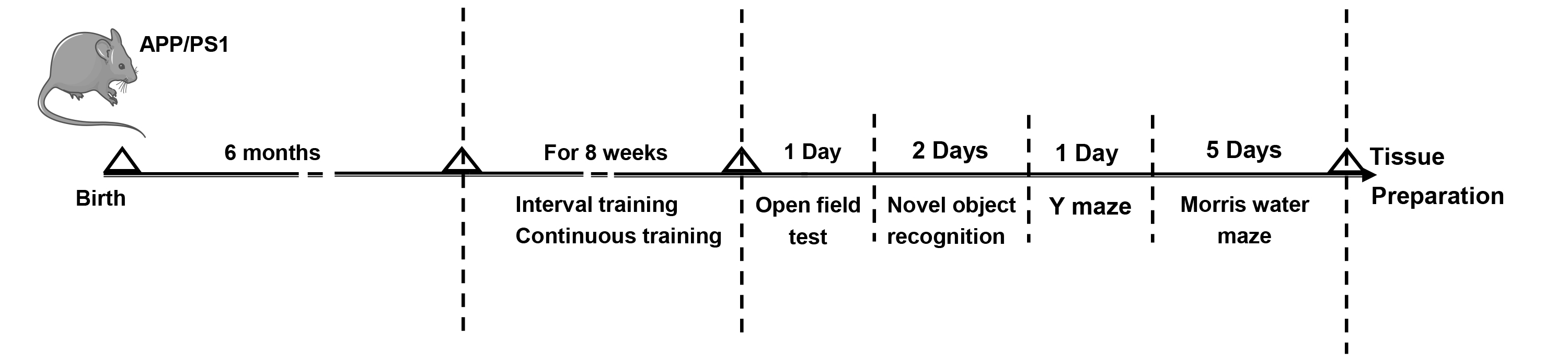

Six-month-old male amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 double transgenic (APP/PS1) transgenic mice (n = 24) were obtained from Beijing Huafukang Biotechnology Co.Ltd (Beijing HFK Bio-Technology, Beijing, China). All mice were housed at the Experimental Animal Center of Xi’an Medical University, and kept under uniform conditions: 22–25 °C, 50%–60% humidity, and a 12-hour light/dark cycle. They had unlimited access to both food and water. Mice were randomly assigned to three groups: rest (AD group, n = 8), aerobic interval training (AIT group, n = 8), and aerobic continuous training (ACT group, n = 8). The animal study was conducted following the guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health regarding the care and use of laboratory animals to minimize both the number of animals and their discomfort. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xi’an Medical University (XYLS2021225). The experimental design is illustrated in Fig. 1. The whole process took 125 days, of which exercise training and behavioral study encompassed 65 days, while tissue preparation, tissue section staining, immunofluorescence, and western blotting took 60 days.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The experimental workflow of animal treatments. APP/PS1, amyloid precursor protein/presenilin-1 double transgenic.

Exercise training was conducted as described previously, with a slightly modified protocol [24, 25].

The ACT training program consisted of an initial week of adaptive training for mice, involving daily 30-minute treadmill sessions at a speed of 8–12 meters per minute. After a one-week adjustment period, the mice underwent consistent training once daily, five days per week for 8 weeks. Each training session lasted approximately 60 minutes at a pace of 13 meters per minute (60%–70% VO2, max).

The AIT training program is described below: The mice exercised at 8–12 meters/min for 30 minutes per day in the first week of training. The mice first underwent running at a speed of 13 meters/min (60%–70% VO2, max) for 5 minutes as a motor preparatory activity after a week. Then, the mice started running at 20 meters/min (85%–90% VO2, max) for 2 minutes, with subsequent increases in speed by 10 meters/min (85%–90% VO2, max) for 4 minutes. The above motor states were alternated for 60 minutes. The mice underwent interval training once daily, five days per week for 8 weeks.

Following the exercise training, all mice underwent behavioral assessments.

The open field apparatus includes a plexiglas box (50 cm

The experimental period was separated into 2 phases: exploration and test phase. Specific operations were as follows. Mice acclimated to the testing environment for 2 hours before the behavioral assessment. In the exploration session, two identical objects were placed in the box for mice to explore for five minutes. In the testing session, one object was replaced with a new object with a distinct shape and color. Following 24 hours of exploration, mice explored the two objects again for 5 minutes. A video-tracking system EthoVision XT 15.0 (Noldus Information Technology BV, Wageningen, Gelderland, the Netherlands) recorded and analyzed the duration of mice’s exploration of familiar and novel objects, calculating the recognition index as the ratio of the time spent on the novel object to the total exploration time.

Mice explored a Y-shaped maze for 10 minutes. Data were analyzed using

EthovisionXT-15 video-tracking software by Noldus. The accuracy of spontaneous

alternation was measured by recording the number of correct consecutive entries

into each arm. Spontaneous alternation percentage = the number of successful

spontaneous alternations/(total arm entries – 2)

The MWM test included four days of learning and memory training trials followed by exploration trials on the fifth day. In the course of the training session, mice were placed in the water from various quadrants while oriented toward the wall of the pool, and the duration taken to find the platform was meticulously recorded. Then the mice were added to the water to explore the target platform for a minute after the platform was removed on the fifth day. The video tracking software SMART 3.0 (Shenzhen RWD Life Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) was employed to measure the latency to target, time in target quadrant, and the platform crossings.

Following 8 weeks of exercise training and behavioral assessments, all mice were sacrificed. Each set of three mice underwent deep anesthesia before intracardiac perfusion of physiological saline and a 4% paraformaldehyde solution. In our study, mice were deeply anesthetized with 5% isofluorane (R510-22-10, Shenzhen RWD Life Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). The dosage was carefully calibrated to 5% to ensure effective anesthesia. We used an anesthesia machine air pump (R510-29, Shenzhen RWD Life Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) to administer the isofluorane. The air pump was set to deliver a steady flow of gas, which was adjusted based on the physiological responses of the mice to maintain the appropriate anesthetic depth. Brain and liver tissues were preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde for one week, followed by paraffin embedding. The resulting paraffin sections were analyzed utilizing hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, Nissl staining, Thioflavin-S fluorescence assay, and immunohistochemical staining. Subsequently, the leftover liver tissues from each group of mice were quickly snap-frozen and subsequently preserved at –80 °C for Western blotting.

HE staining was conducted following the instructions of the manufacturer, utilizing the HE staining kit (G1076, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, Hubei, China). Briefly, after deparaffinization and hydration of the paraffin sections, they were kept in a pretreatment solution for 1 minute. Subsequently, the sections underwent staining with hematoxylin for 5 minutes, followed by exposure to eosin for 15 seconds. Following dehydration and sealing, the sections were observed using a Nikon ECLIPSE microscope (E100, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and images were captured using a Nikon DS-U3 image acquisition system 1.00 (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The degree of hippocampal neuronal damage in each group of mice was assessed using the scoring criteria established by Shi et al. [26] and Pulsinelli and Brierley [27].

Utilizing Nissl staining, the Nissl bodies in neurons were detected to determine neuronal survival. The Nissl Staining Solution (G1036, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, Hubei, China) was used for Nissl staining. After the deparaffinization and hydration of paraffin sections, Nissl solution was introduced for a 5-minute duration, mildly differentiated with 0.1% glacial acetic acid (10000218, Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The process was concluded by washing with tap water. Following transparency and sealing, the sections underwent Nikon ECLIPSE microscope (E100, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and Nikon DS-U3 image acquisition system 1.00 (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Cells whose nucleus and nucleolus could be clearly observed for analysis were selected.

Thioflavin S has been extensively employed to identify the presence and localization of amyloid plaques [28]. Brain sections embedded in paraffin, each measuring 4 µm in thickness, underwent treatment with a 0.3% thioflavin-S solution (S19293, Shanghai Ye Yuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at ambient temperature for 8 minutes. After cleaning with 80% ethanol (100092183, Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and rinsing with deionized water, the slides were exposed to DAPI staining solution (G1012, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, Hubei, China) for 10 minutes in the dark. To finish, anti-fluorescence quenching sealing tablets (G1401, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, Hubei, China) were used to seal the slides. Images were acquired using a 3DHISTECH digital scanner (Pannoramic MIDI, 3DHISTECH Ltd., Budapest, Hungary). Amyloid deposition in the mouse brain was assessed by identifying thioflavin-S-positive regions.

The deposition of A

The liver tissues from each group of mice were lysed and homogenized using a cryogenic grinder (Wuhan Servicebio Technology, Wuhan, China) at 4 °C. Tissue proteins were extracted by centrifuging at 12,000 g and 4 °C for 10 minutes using an Eppendorf centrifuge (5804R, Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). The concentration of proteins was subsequently quantified utilizing a BCA protein assay kit (P0010, Beyotime Biotechnology, Nantong, Jiangsu, China). The expression of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP-1) and Cathepsin-D was measured via Western blotting, considering glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the internal control. Protein samples were separated using Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked using 5% skim milk (GC310001, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, Hubei, China) at ambient temperature for two hours, followed by an overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C. The membranes were then incubated for 1 hour with a HRP-goat anti-rabbit recombinant secondary antibody (H+L) (RGAR001, Proteintech Group, Inc., Rosemont, IL, USA, 1:5000 dilution). The main antibodies employed in this study were rabbit polyclonal anti-LRP1 antibody (26106-1-AP, Proteintech Group, Inc., Rosemont, IL, USA), rabbit polyclonal anti-Cathepsin D antibody (21327-1-AP, Proteintech Group, Inc., Rosemont, IL, USA), and rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (10494-1-AP, Proteintech Group, Inc., Rosemont, IL, USA), at a dilution of 1:1000. Image J was employed to measure band densities. Protein expression levels were measured by comparing the density of each protein to that of GAPDH, showing variations in the expression of the target proteins.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and are

presented as mean

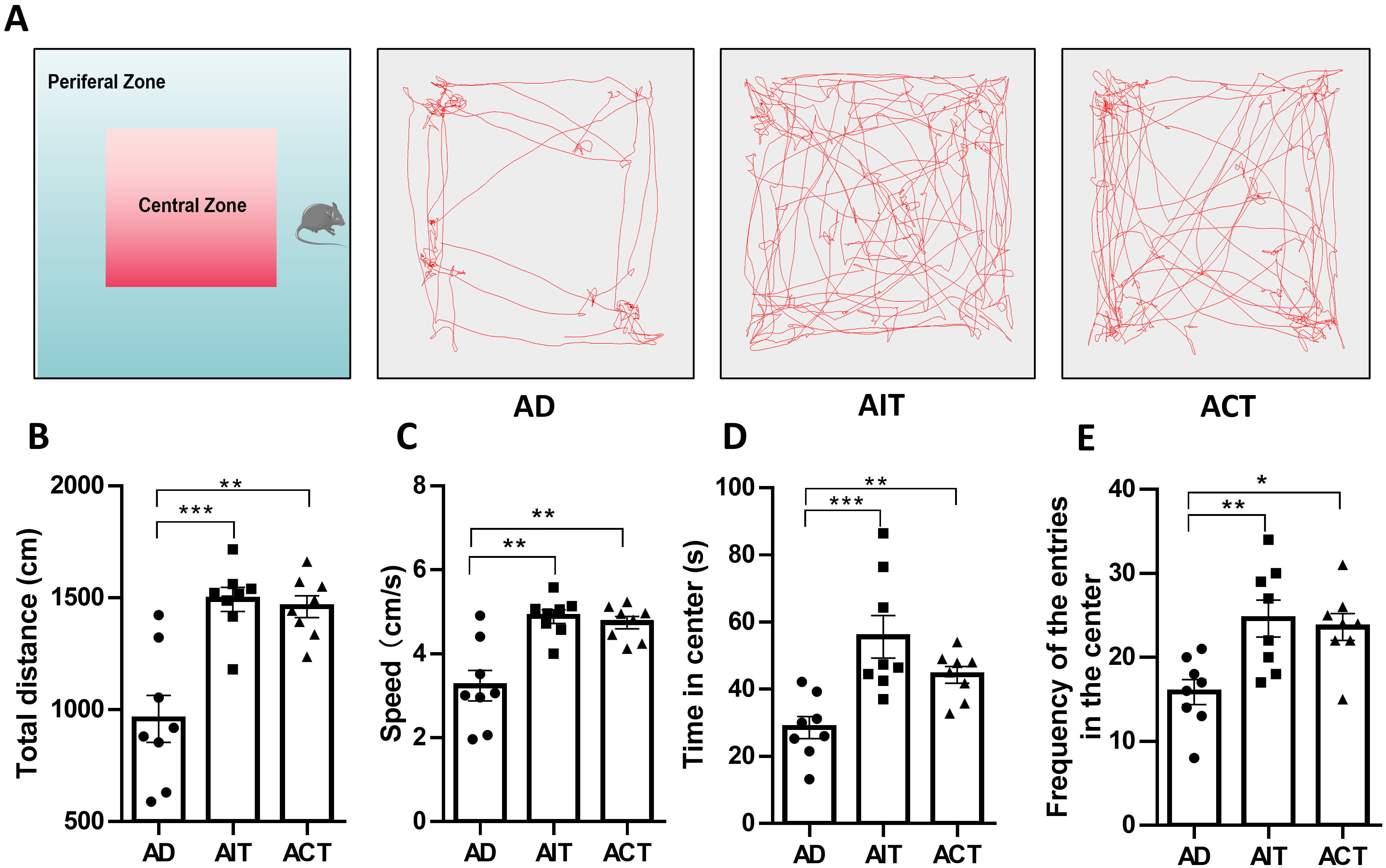

The open-field experiment assessed mice spontaneous locomotor activity, anxiety levels, and exploratory activity [29]. Fig. 2A illustrates the open-field activity trajectories for each group of mice. Compared to the AD group, the AIT and ACT groups exhibited a significant increase in both moving distance (Fig. 2B) and mean moving speed (Fig. 2C). Mice in the AIT and ACT groups spent significantly more time in the central zone (Fig. 2D) and crossed the central area (Fig. 2E) more frequently than those in the AD group. The results showed that both AIT and ACT exercise increased the spontaneous activity and exploration abilities of AD mice and decreased their anxiety levels.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Effects of AIT and ACT on exploratory behavior and anxiety in

APP/PS1 mice. (A) Representative images of the movement track of mice, (B) total

distance, (C) speed, (D) time in the center, (E) frequency of the entries in the

center. Data are presented as mean

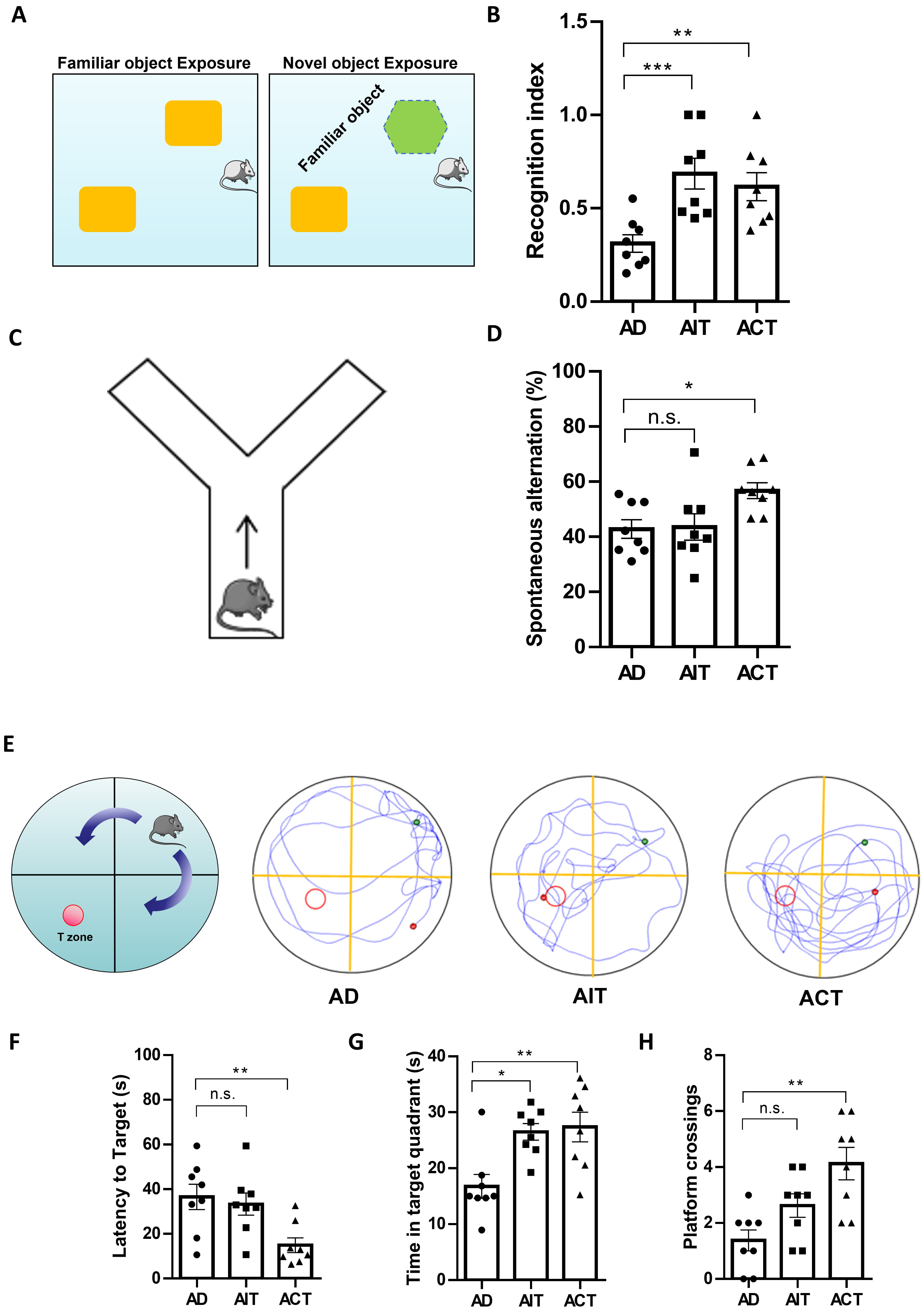

We conducted NOR tests to evaluate mice object recognition memory by measuring exploration time of novel and familiar objects [30] (Fig. 3A). These findings indicated that both AIT and ACT significantly enhanced the capacity of mice to distinguish new from familiar objects, measured by the recognition index (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Effects of AIT and ACT on cognitive impairments in APP/PS1

mice. (A) Schematic diagram of the novel object recognition (NOR) test, (B)

recognition index, (C) schematic diagram of the Y maze test, (D) spontaneous

alternation, (E) representative images of the movement track of mice, (F) latency

to target, (G) time in target quadrant, (H) platform crossings. *p

Subsequently, we assessed spatial learning and memory in mice using the Y-maze spontaneous alternation test [31] (Fig. 3C). The Y-maze test indicated a significantly higher spontaneous alternation rate in the ACT group compared to the AD group (Fig. 3D).

The MWM test evaluates the learning and memory in mice [32]. During the MWM experiment, we analyzed the time and trajectory of mice in each group as they searched for a concealed platform. The results revealed that compared to the AD group, mice in the AIT and ACT groups exhibited more organized swimming patterns, with the ACT group exhibiting decreased escape latency (Fig. 3E,F). After removing the platform, mice were given 60 seconds to navigate the maze. These findings indicated that mice in the AIT and ACT groups spent more time in the target quadrant than the AD group, with the ACT group showing a higher frequency of platform crossings (Fig. 3G,H). Overall, these findings indicated that aerobic exercise, whether through AIT or ACT, can improve learning and memory functions in APP/PS1 mice.

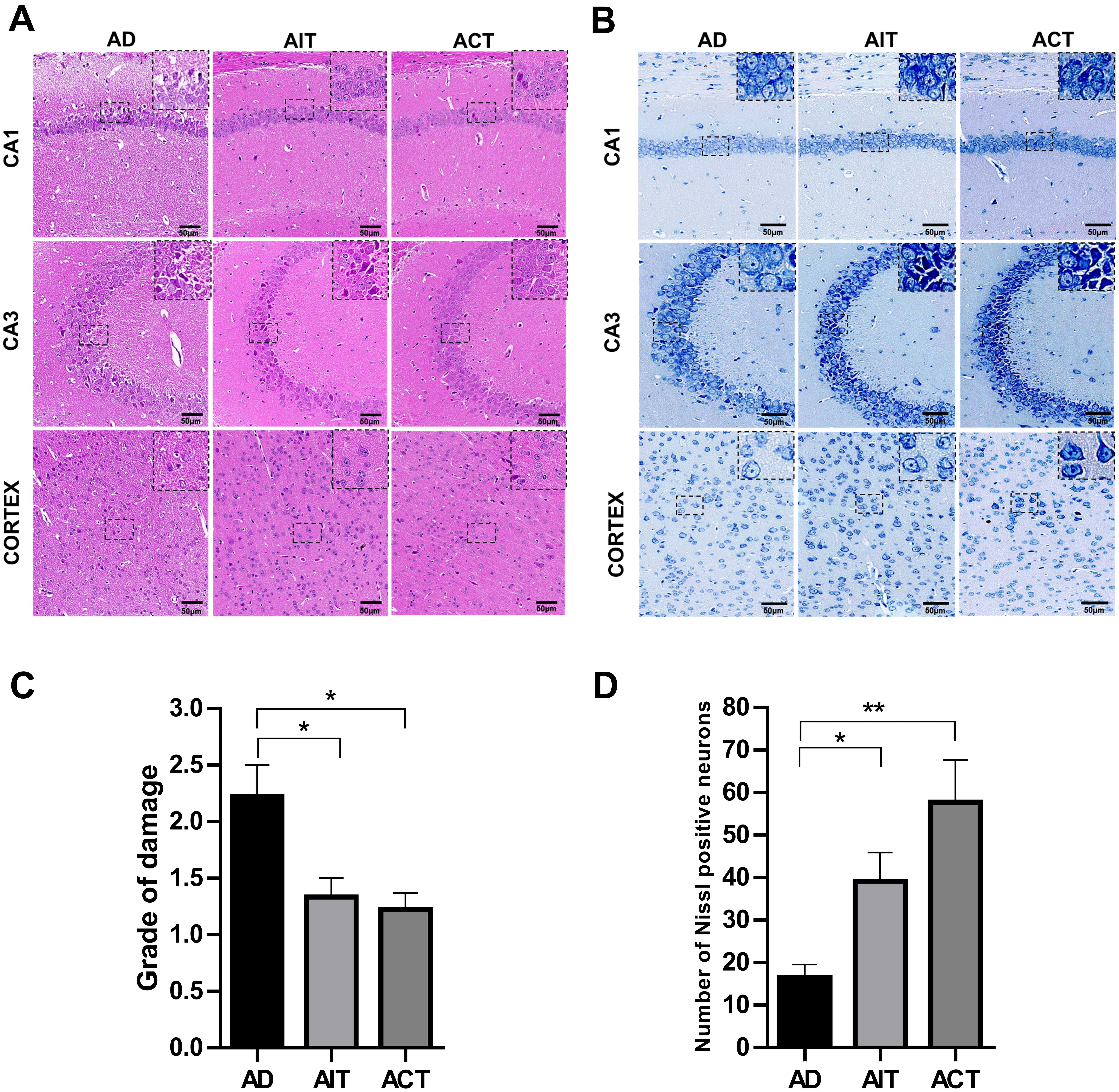

We studied pathological alterations in the brain with HE and Nissl staining to assess AIT and ACT effects on neuronal injury. Representative images of HE staining in the AD group (Fig. 4A) showed disordered neuronal arrangement, increased intercellular space, cellular vacuolization, nuclear pyknosis, and disappearance of the nucleolus, suggesting neuronal injuries in the hippocampus and brain cortex. Conversely, mice undergoing AIT and ACT showed a marked improvement in pathological alterations in the hippocampus and cortex, with a significantly lower score of neuronal damage. The results showed neatly organized neuronal cells with pale red cytoplasm, blue nucleus and clear nucleolus (Fig. 4A,C). Nissl staining showed significantly more Nissl-positive neurons in the hippocampus and cortex of the AIT and ACT groups than in the AD group (Fig. 4B,D). These findings demonstrated that both AIT and ACT protected against neuronal damage in APP/PS1 mice.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Effects of AIT and ACT on the histopathological changes of

APP/PS1 mice. (A) Representative HE images of different regions in the brain.

(B) Representative images of Nissl-stained brain sections. Scale bars: 50

µm. (C) Statistical analysis of the grade of neuronal damage of HE

staining. (D) Statistical analysis of Nissl positive cells. Representative images

were captured from 3 mice per group. All data are expressed as mean

We subsequently measured A

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Effects of AIT and ACT on A

Hepatocytes, the primary cells of the liver, are essential for the hepatic

clearance of A

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Effects of AIT and ACT on A

The expression of A

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

The effects of AIT and ACT on A

Engaging in suitable physical exercise has been shown to effectively prevent and

delay neurodegenerative diseases like AD [35, 36]. Although there is no agreement

on the most effective exercise program for enhancing cognitive function in

individuals with AD, aerobic exercise is widely regarded as an important

adjunctive treatment. Nevertheless, the exact mechanism by which aerobic exercise

confers a protective effect in AD remains unclear. Most studies have focused on

changes in brain cells and pathological markers, like A

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Schematic diagram showing the protective effect of

aerobic exercise on APP/PS1 transgenic mice and its underlying mechanism.

Aerobic exercise improved learning and memory, enhanced exploration ability, and

ameliorated the anxiety of APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Additionally, aerobic

exercise decreased neuronal damage and A

A primary clinical characteristic of patients with AD is the progressive

deterioration of cognitive abilities, a phenomenon also observed in mouse models

of APP/PS1 [40, 41]. These mice also show A

Behavioral dysfunction in AD has been linked to the structural and functional

deficits observed in particular brain regions. Neuronal loss in various brain

regions significantly contributes to the development of AD [49]. The hippocampus

and cortex are particularly susceptible to A

AD has traditionally been viewed as a brain-specific condition. However, the

study has shown that nearly 50% of the A

In summary, our study demonstrated that both AIT and ACT over an eight-week

period can ameliorate spatial and cognitive memory impairment, reduce spontaneous

activity and anxiety-like behaviors, mitigate neuronal injury, and diminish the

synthesis and accumulation of A

Taken together, our findings demonstrated that aerobic exercise improved

learning and memory, enhanced exploration ability, and reduced the anxiety of

APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Moreover, aerobic exercise reduces neuronal damage and

A

The paper is listed as “Aerobic Exercise Ameliorate Alzheimer’s Disease-Like Pathology by Regulating Hepatic Phagocytosis of A

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; AIT, aerobic interval training; ACT, aerobic continuous training; A

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to Further research is needed, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

QW: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Writing—original draft. FH: Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Software, Visualization. XG: Conceptualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing—review & editing. SW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. NJ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing—review & editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xi’an Medical University (approval number: XYLS2021225).

The authors would like to express their gratitude to EditSprings (https://www.editsprings.cn) for the expert linguistic services provided and thank Figdraw as the Fig. 8 in this article was created using Figdraw.

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82201599 and 81971330), Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (2021JM-505), Innovation Capacity Support Program-Science and Technology Resources Open and Sharing Platform of Shaanxi (2024CX-GXPT-08), Scientific Research Project of Xi’an Medical University (2023QN04).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL36597.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.