1 Laboratory of Stem Cell Biology, Bogomoletz Institute of Physiology, 01601 Kiev, Ukraine

Abstract

The mechanisms underlying the effects of pharmacological mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channel (mKATP) channel openers on the functional effects of the mKATP channels opening remain disputable. Earlier we have shown that the mKATP channel activation by diazoxide (DZ) occurred at submicromolar concentrations and did not require a MgATP in liver mitochondria. This work aimed to evaluate a requirement of a MgATP for the mKATP channel opening by DZ and its blocking by glibenclamide (Glb) and 5-hydroxy decanoate (5-HD) in rat brain mitochondria and to find the effects of the mKATP channels opening on mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP).

The mKATP and the mPTP channels activity was assessed by the light scattering; polarography was applied to quantify K+ transport; Ca2+ transport and ROS production were monitored with fluorescent probes, chlortetracycline, and dichlorofluorescein, respectively; one-way ANOVA was used for reliability testing.

ATP-sensitive K+ transport in native mitochondria was fully activated by DZ at <0.5 μM and blocked by Glb and 5-HD in the absence of a MgATP, however, Mg2+ was indispensable for the blockage of the mKATP channel by ATP. DZ increased Ca2+ uptake, but ROS production was regulated differently: suppressed in mitochondria respiring on glutamate, but activated on succinate. However, in the presence of rotenone, ROS production was suppressed by DZ, which indicated the involvement of reverse electron transport (RET) in the modulation of ROS production. In all cases, the mKATP channel blockers reversed the effects of DZ. The impact of DZ on the mPTP opening strongly correlated with its effects on ROS production. DZ inhibited the mPTP activity on glutamate but elevated on succinate, which was strongly suppressed by rotenone. In the presence of rotenone, the mPTP was strongly inhibited by DZ, which indicated the involvement of ROS and RET in the mechanism of mPTP regulation by DZ.

Brain mKATP channel exhibited high sensitivity to DZ on the low sub-micromolar scale; its regulation by DZ and Glb did not require a MgATPase activity; the impact of DZ on the mPTP activity was critically dependent on the regulation of ROS production by ATP-sensitive K+ transport.

Keywords

- mitochondria

- brain

- mKATP channel

- diazoxide

- glibenclamide

- ROS

- mPTP

A primary role of the mitochondrial KATP channel (mKATP channel) in the mechanisms of neuro- and cardioprotection under several pathophysiological processes accompanied by ischemia, hypoxia, oxidative/nitrosative stress, and metabolic disorders has been shown for three decades of extensive research. Neuro- and cardioprotective effects of the mKATP channel openers, and their anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory actions were shown in different models of ischemia/reperfusion [1, 2], cardiovascular disorders [3, 4, 5], and neurodegenerative diseases [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. The salvatory role of the mKATP channel in the prevention of apoptotic and necrotic cell death has been explained by cytoprotective signaling triggered by the complex impact of ATP-sensitive K+ transport on mitochondrial dynamics [8, 9] and mitochondrial functions. According to contemporary knowledge, the modulation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [1, 3], nitric oxide (NO) production [1, 4, 11], and suppression of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) [1, 11], a mitochondrial megachannel involved in triggering cell death pathways and the development of several pathophysiological conditions, were the background mechanisms of cytoprotection afforded by the mKATP channels opening.

Generally, ATP-sensitive K+ transport is a modulator of the whole complex of mitochondrial functions: oxygen consumption, potassium cycle [12, 13], ATP synthesis [14, 15], Ca2+ transport [16, 17], NO [1, 4, 11, 18] and ROS production [1, 3, 4, 11, 18, 19, 20]. This implies the importance of the pharmacological regulation of the mKATP channel and ATP-sensitive K+ transport in mitochondria for treating diseases and pathophysiological conditions. However, the mechanisms of pharmacological regulation of the mKATP channels and their functional effects remain disputable. Thus, the direct impact of the mKATP channel openers on mitochondrial ROS production reported in the literature was highly controversial: both the increase [1, 11, 19] and the reduction [3, 18, 20] of ROS release by ATP-sensitive K+ transport were reported. There was no consensus too regarding the impact of the mKATP channel opening on mitochondrial Ca2+ transport [16, 17]. The mPTP is a generally recognized target of the mKATP channel opening by pharmacological openers [1, 11], but the mechanisms underlying their direct effects on the mPTP activity remain poorly understood.

One of the key issues in the mechanisms of pharmacological regulation of the

mKATP channels is their sensitivity to pharmacological openers (diazoxide,

pinacidil, nicorandil, etc.) and blockers (glibenclamide, 5-hydroxy decanoate)

and the requirement of a Mg2+ and ATP (MgATP) for the regulation of

bioenergetic and functional effects of ATP-sensitive K+ transport.

Generally, it was assumed that the opening of the mKATP channels required the

presence of MgATP. In several studies, the mKATP channel blocking by

glibenclamide and 5-hydroxy decanoate (5-HD) occurred after the initial blocking

by a MgATP and a consequent opening by micromolar concentrations of diazoxide and

other openers [21, 22, 23]. Meanwhile, reports appeared in the literature on the

functional effects of pharmacological opening and blocking the mKATP channel in

the absence of a MgATP [24, 25]. However, there remained an uncertainty regarding

the selectivity of these effects because of numerous off-target actions of these

drugs [26, 27, 28], especially at high micromolar concentrations, which inhibit SDH

(DZ), complex I (pinacidil), F0F1 ATP synthase (DZ, glibenclamide),

interfere with

Earlier we have shown that native mKATP channel activity was involved in the regulation of Ca2+ transport and ROS production in brain mitochondria [29, 30]. Also, we have found that in the absence of an MgATP the KATP channel of rat liver mitochondria could be fully activated by sub-micromolar concentrations of this drug, which allowed for avoiding many of its known off-target effects [31]. So, it was interesting to study the functional effects of the mKATP channels opening by sub-micromolar concentrations of DZ. This work aimed to examine a requirement of a MgATP for the mKATP channel opening by diazoxide (DZ) and its blocking by glibenclamide and 5-hydroxy decanoate (5-HD) in rat brain mitochondria and to find the effects of the mKATP opening on mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, ROS production, and the mPTP activity.

The work has been carried out following Council of Europe Convention on Bioethics (1997) approved by the Ethics Commission on Animal Experiments of A.A. Bogomoletz Institute of Physiology, NAS of Ukraine (protocol N1/23 of 11.01.2023). Adult Wistar-Kyoto female rats with 180–200 g mean body weight were used. Each experiment was repeated 4–6 times, two animals were used in each experimental setting. The rats were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of 200 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/mL). After the complete lack of reflexes was ascertained, the head was removed by scissors. The brain was washed by cold 0.9% KCl solution (4 °C), minced, and homogenized in 1:5 volume of the isolation medium: 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, 4 °C (pH 7.2). BSA was added at 1 mg/mL. Mitochondria were isolated by centrifugation at 1000 g for 7 min (4 °C). After the pellet was discarded, the supernatant was centrifuged again at 12,000 g for 15 min (4 °C). The final pellet was resuspended in a small volume of isolation medium without EDTA and stored on ice. The protein content was determined by the Lowry method.

Oxygen consumption was studied polarographically in 1 cm3 closed thermostated cell at 26 °C with the platinum electrode at constant stirring in standard incubation medium: 120 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM sodium glutamate, 1 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), oligomycin (1 µg/mg protein). Polarograph LP7 (Czech Republic) equipped with a platinum electrode and the chart recorder was used. Depending on the conditions, MgCl2 (1 mM), ATP (0.3 mM), glibenclamide (5 µM), and 5-HD (100 µM), were added. Diazoxide was added to the standard incubation medium at the concentrations required. In the presence of Mg2+ EDTA was replaced by EGTA. Mitochondria were added at 1.5–2.0 mg/mL protein.

Potassium transport was studied based on the light scattering of mitochondrial suspension. Light scattering is known to decrease because of mitochondrial swelling due to water transport, which accompanies the transport of potassium [13]. Initial rates of potassium transport (V0) were found by monitoring light scattering on a spectrofluorimeter Hitachi F4000 (Japan) at 520 nm excitation/emission wavelengths in 1 cm3 cell starting from the addition of mitochondria at 0.3 mg/mL to standard incubation medium: 150 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM sodium glutamate, 1 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), oligomycin (1 µg/mg protein). Depending on the conditions, MgCl2 (1 mM), ATP (1 mM), glibenclamide (5 µM), and 5-HD (100 µM), were added. Diazoxide was added to the standard incubation medium at the concentrations required. In the presence of Mg2+ EDTA was replaced by EGTA.

The mPTP opening was assessed as cyclosporine A-sensitive swelling of mitochondria by monitoring light scattering of mitochondrial suspensions at 520 nm excitation/emission wavelengths in 1 cm3 cell in the incubation medium: 150 mM KCl, 5 mM sodium succinate (glutamate), 1 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4). CaCl2 was added at 20 µM, cyclosporine A was added at 1 µM, diazoxide was added at 0.5 µM, and glibenclamide and 5-HD were added at 5 and 100 µM respectively. The registration of the mPTP activity was monitored for 3 min starting from the addition of mitochondria at 0.3 mg/mL. The decrease of light scattering of mitochondrial suspensions under our experimental conditions was caused both by mPTP opening and potassium uptake from the K+-based incubation medium. So, mPTP activity was assessed as a cyclosporine-sensitive difference in swelling amplitude found over the time of registration.

Calcium transport was monitored with Ca2+ binding probe chlortetracycline (CTC), which indicated the changes in Ca2+ concentration in the matrix [32]. The increase of CTC fluorescence upon Ca2+ binding in the matrix was monitored at 392/536 excitation/emission wavelengths, bandpass 5 nm, on a spectrofluorimeter Hitachi F4000 in the medium used for the study of the mPTP opening. Mitochondria were added at 1.0 mg/mL; CTC was added at 10 µM, CaCl2 was added at 20 µM, cyclosporine A was added at 1 µM. Additionally to the light scattering assay, CTC was used to assess the mPTP opening. The mPTP activity was estimated as a cyclosporine-sensitive difference in Ca2+ uptake after 3 min registration and expressed in relative units. Using a sucrose-based medium, we ascertained that neither DZ nor the mKATP blockers glibenclamide and 5-HD affected CTC fluorescence per se.

A widely used probe 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH2DA) was applied for monitoring ROS formation. This compound readily penetrates mitochondrial membranes following the concentration gradient and deacetylates in the matrix forming membrane-impermeable non-fluorescent derivative H2DCF (2′,7′-dihydrodichlorofluorescein), which is oxidized by mitochondrial ROS resulting in highly fluorescent end product 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein, dichlorofluorescein (DCF) [33]. Mitochondria in stock suspension (20 mg/mL) were preloaded with 200 µM of DCFH2DA for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark, then washed off the excess probe and stored on ice (4 °C). After adding mitochondria at 1 mg/mL to the incubation medium chosen for the study of the mPTP opening, the increase in DCF fluorescence reflecting ROS formation was monitored on a spectrofluorimeter Hitachi F4000 over 5 min time intervals, with monitoring of mPTP opening in parallel experiments. Quasi-linear segments of the time courses of DCF fluorescence were chosen to estimate the rate of ROS production. As we have shown earlier [34], this coincided with keeping stable rates of the state 4 respiration under steady-state conditions. The rate of the increase in DCF fluorescence was assumed to reflect the rate of ROS formation in mitochondria.

Membrane potential (

All reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Deionized water was used in all experiments for solutions preparations.

The data were expressed as mean

Light scattering (LS) is one of the most direct approaches to assess potassium transport in isolated mitochondria, because of the concomitant water transport, which uptake accompanies K+ uptake via K+ channels, and the efflux occurs together with K+ release via K+/H+ exchanger [13]. So, we studied the effect of DZ and pharmacological mKATP channel modulators on the light scattering of mitochondrial suspensions.

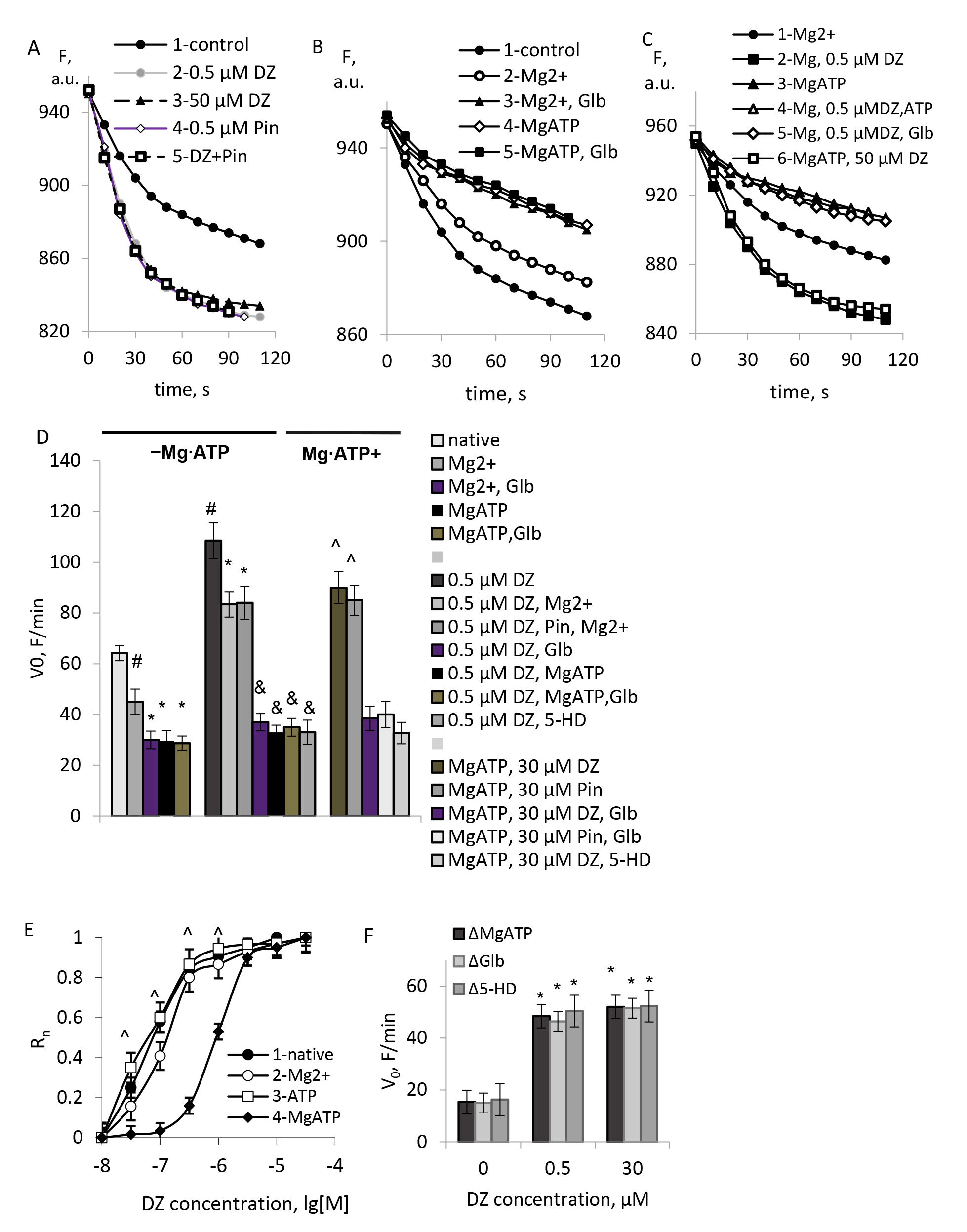

In Fig. 1A–C representative traces of K+ uptake in the presence of different concentrations of DZ and the modulators of the mKATP channels, MgATP, and glibenclamide are shown. As we observed earlier in liver mitochondria, the mKATP channel of brain mitochondria was highly sensitive to sub-micromolar concentrations of DZ (Fig. 1A). An activation of rat brain mitochondria KATP channel by DZ occurred with Ka ~150 nM and reached a plateau at ~0.5 µM (Fig. 1D). ATP-sensitive K+ transport was routinely blocked by ATP in the presence of Mg2+ (Fig. 1B,E), but individually neither Mg2+, nor ATP at 1 mM concentrations affected the sensitivity of mKATP channel to DZ (Fig. 1E, 1–3).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Typical records of the light scattering (LS) of mitochondrial

suspensions in the presence of the mKATP channels modulators. (A–C)

Representative traces of light scattering in the presence of the mKATP channel

modulators. (D) Initial rates of swelling in the presence of the mKATP channels

modulators. (E) Normalized rates of DZ-stimulated swelling of brain mitochondria.

(F) ATP-sensitive component of K+ transport found from the blocking by the

MgATP, glibenclamide (Glb), and 5-HD. M

In agreement with the common knowledge [21, 22, 23], KATP channels’ activity was routinely restored by the high micromolar concentrations of DZ (30 µM) in the presence of 1 mM MgATP (Fig. 1C,E). To confirm the activation of the mKATP channel, we used KATP channel opener pinacidil at the same concentrations. The effects of pinacidil were similar to the impact of DZ (Fig. 1A,D). The mKATP channel activated by the high micromolar concentrations of DZ in the presence of a MgATP was blocked by glibenclamide (5 µM) and selective mKATP channels blocker 5-HD (100 µM). Similar effects were observed with pinacidil (Fig. 1A,E). Besides the above experiments, which ascertained the activity of the mKATP channel in mitochondrial preparations, we observed the native mKATP channel’s high sensitivity to DZ and its activation by this drug at sub-micromolar concentrations in the absence of a MgATP (Fig. 1A,D). Similar to the activation by DZ, the mKATP channel blockage by glibenclamide and 5-HD did not require a MgATP either (Fig. 1B,E).

To prove the identity of an ATP-sensitive K+ transport observed in our experiments with the mKATP channel activity, we used a MgATP for additional blockage of the ATP-sensitive K+ transport. As shown in the experiments, combined blockage of native ATP-sensitive K+ transport by glibenclamide and ATP in the presence of Mg2+ gave the same results as individual blockage of K+ transport either by glibenclamide or MgATP (Fig. 1B,E). Close results were obtained by blocking of an ATP-sensitive K+ transport activated by sub-micromolar concentrations of DZ by glibenclamide in the absence of a MgATP (Fig. 1C,E). These data indicated a lack of any K+ transport activity sensitive to individual mKATP channel blockers (glibenclamide (Glb), 5-hydroxy decanoate (5-HD)), and not sensitive to an MgATP. Worth notion of the equality of the components of native K+ transport sensitive to glibenclamide, 5-HD, and MgATP, K+ transport activated by DZ in the absence of an MgATP, and K+ transport activated by the high concentrations of DZ in the presence of an MgATP (Fig. 1F).

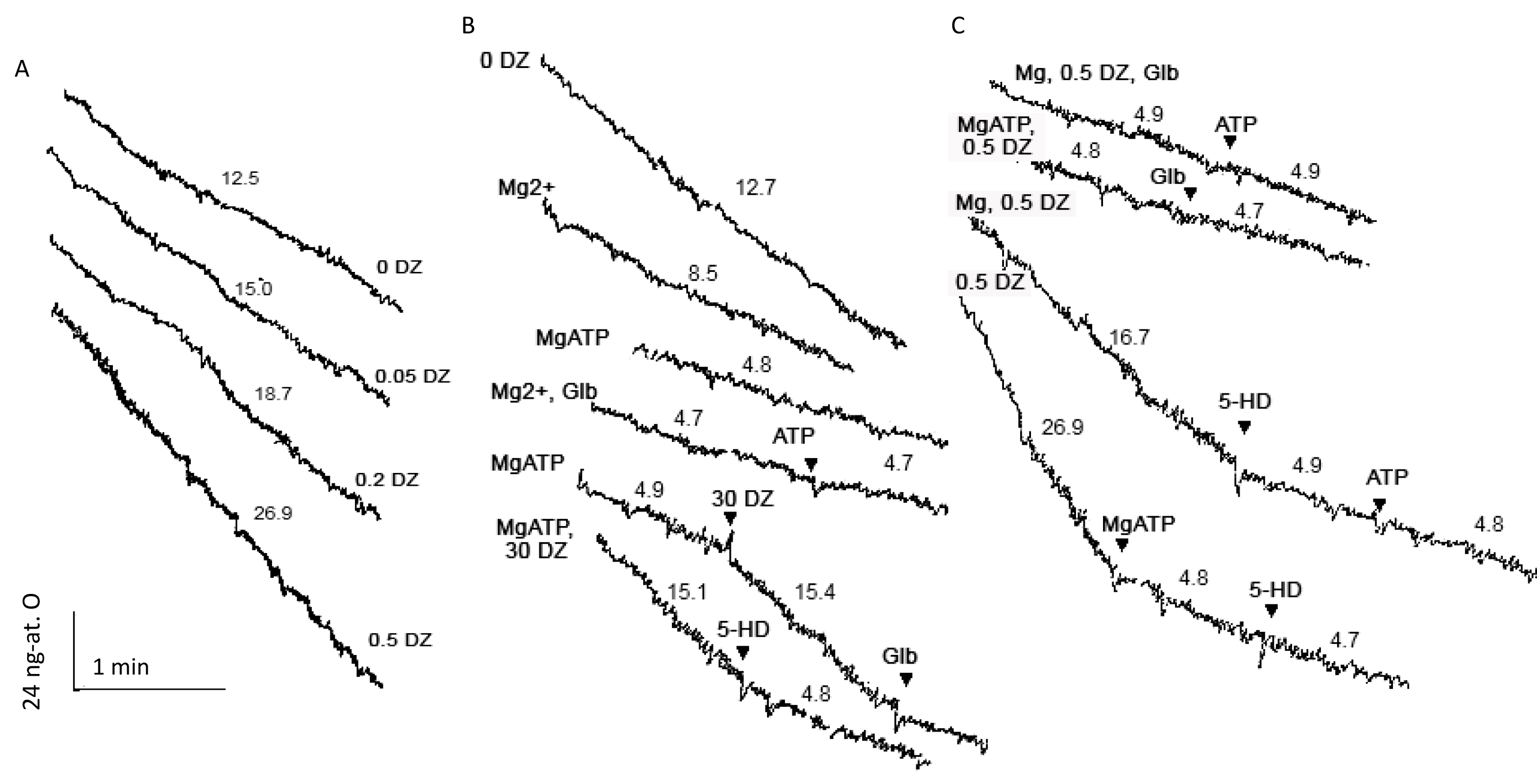

To confirm the results obtained by the light scattering assay, the effects of DZ on the mKATP channel activity were assessed by measuring oxygen consumption in mitochondria. This approach has the advantage of the assessment of the mKATP channels activity ‘in situ’ allowing for the consecutive additions of the mKATP channels modulators to the same suspension of respiring mitochondria in which a constant rate of potassium transport is kept by the K+ cycle [13]. In Fig. 2 typical polarographic records of mitochondrial respiration are shown. DZ increased the state 4 oxygen consumption and the rate of K+ uptake in a concentration-dependent way (Fig. 2A), which resembled liver mitochondria (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Representative polarographic records of glutamate-driven

respiration of brain mitochondria in the presence of the modulators of the mKATP

channel. (A) The effect of DZ on the rate of respiration. (B,C) The effects of

Mg2+, ATP, and pharmacological KATP channel blockers, Glb and 5-HD, on

oxygen consumption under various conditions. The rates of respiration are

indicated on the curves in ng-at. O

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The effects of DZ and the mKATP channel blockers on the oxygen

consumption in brain mitochondria respiring on glutamate. (A) Normalized

dependence of the respiration rates on DZ concentration in brain and liver

mitochondria; on the ordinate axis: normalized oxygen consumption rate. (B) The

rates of respiration in the presence of the mKATP channel modulators. (C) The

effect of DZ on the MgATP-, Glb-, and 5-HD-sensitive parts of state 4

respiration. M

The sensitivity of K+ transport to DZ in native mitochondria without a

MgATP well agreed with our earlier results on liver mitochondria (Fig. 3A) and

the results obtained by light scattering measurements (Fig. 1). To prove an

activation of the mKATP channel by DZ in the absence of a MgATP, we blocked both

native and activated channels by a MgATP, glibenclamide, and 5-HD and compared a

MgATP-sensitive difference in the rate of native and DZ-stimulated respiration.

As we observed, in the absence of a MgATP, DZ increased a MgATP-sensitive part of

respiration at low sub-micromolar concentrations, and full activation of oxygen

consumption was reached at

To prove the identity of the ATP-sensitive K+ transport activated by DZ under different conditions, we blocked K+ transport by a MgATP, glibenclamide, and 5-HD (Fig. 2B,C; Fig. 3B). Similar to light scattering, oxygen consumption too was blocked by glibenclamide and 5-HD in the absence of a MgATP (Fig. 2B,C). In the presence of Mg2+, in native mitochondria, glibenclamide suppressed part of respiration, which was not blocked further by the addition of ATP (Figs. 2B,C). The addition of ATP in the presence of Mg2+ further suppressed respiration because of the blockage of the mKATP channel, and this effect was not increased by the following addition of glibenclamide (Fig. 2B,C). Similar results were obtained with 5-HD. The results of the experiments summarized in Fig. 3B indicated an identity of the parts of respiration blocked by MgATP, glibenclamide, and 5-HD in native mitochondria, which allowed us to ascribe these effects to the same mKATP channel activity. With the same approach, we have shown an activation of an ATP-sensitive K+ transport by sub-micromolar concentrations of DZ in the absence of an MgATP. As before, a glibenclamide-sensitive part of the respiration equaled a MgATP-sensitive one, and a MgATP-sensitive part of respiration related to the mKATP channel activity equaled the rates of respiration blocked by glibenclamide and 5-HD (Fig. 3C).

An estimation of the rate of ATP-sensitive K+ transport from polarographic

data, based on K+:O stoichiometry 10:1 gave ~40

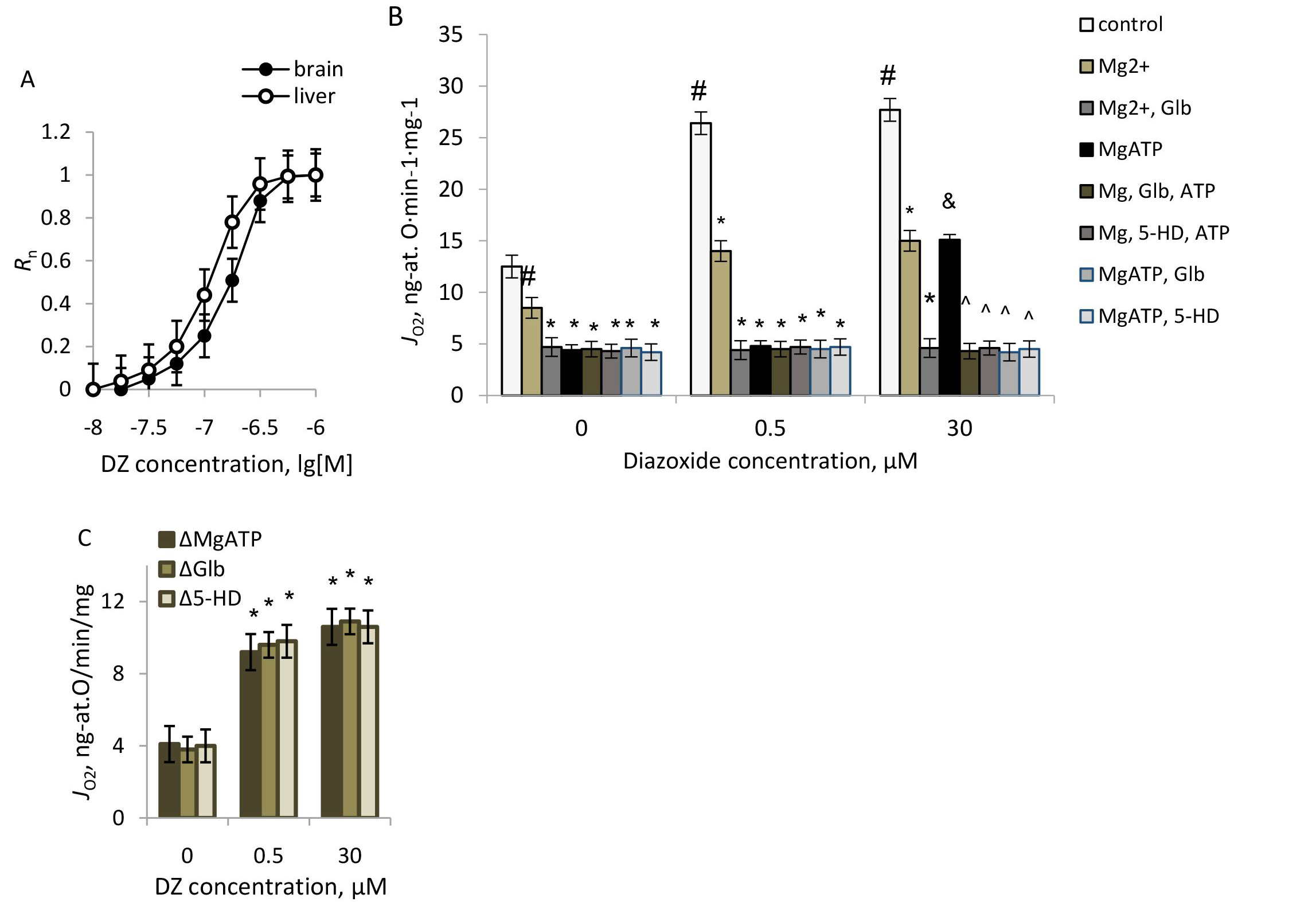

The increase in CTC fluorescence reflects the elevation of Ca2+ concentration in the mitochondrial matrix [32]. As shown in the experiments, Ca2+ accumulation observed with CTC well responded to standard assays of Ca2+ transport: Ca2+ accumulation was followed by Ca2+ efflux after the protonophore CCCP addition at 10-6 M. Using a sucrose-based medium, we ascertained that neither DZ nor the mKATP channel blockers glibenclamide and 5-HD affected CTC fluorescence per se.

Ca2+ uptake was elevated by DZ and blocked by glibenclamide and 5-HD

without a MgATP (Fig. 4). Assuming that Ca2+ uptake followed first-order

kinetics, the rate constants (k) found from semi-logarithmic plots were

(3.2

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The effects of DZ and the mKATP channel blockers on Ca2+

uptake and the membrane potential in rat brain mitochondria. (A) Typical records

of Ca2+ uptake and CCCP-induced Ca2+ efflux. (B–D) The effects of DZ,

Glb, and 5-HD on Ca2+ uptake. (E) The effects of DZ, 5HD, and Glb on the

membrane potential of mitochondria. M

Earlier we have shown that the mKATP channels’ activity contributed to the increase in matrix calcium accumulation in native brain mitochondria [29]. As we observed in this study, the mKATP channel activation by DZ still promoted Ca2+ uptake, independent of the respiratory substrate (Fig. 4B,C). The mKATP channels blockers, glibenclamide, and 5-HD similarly reduced Ca2+ uptake in mitochondria without a MgATP (Fig. 4B,C), contrary to their hyperpolarizing effect in brain mitochondria (Fig. 4E), which proved that the stimulation effect of DZ on Ca2+ uptake resulted from the mKATP channels’ activation.

Ca2+ uptake in mitochondria via the Ca2+ uniporter is known

to be strongly dependent on

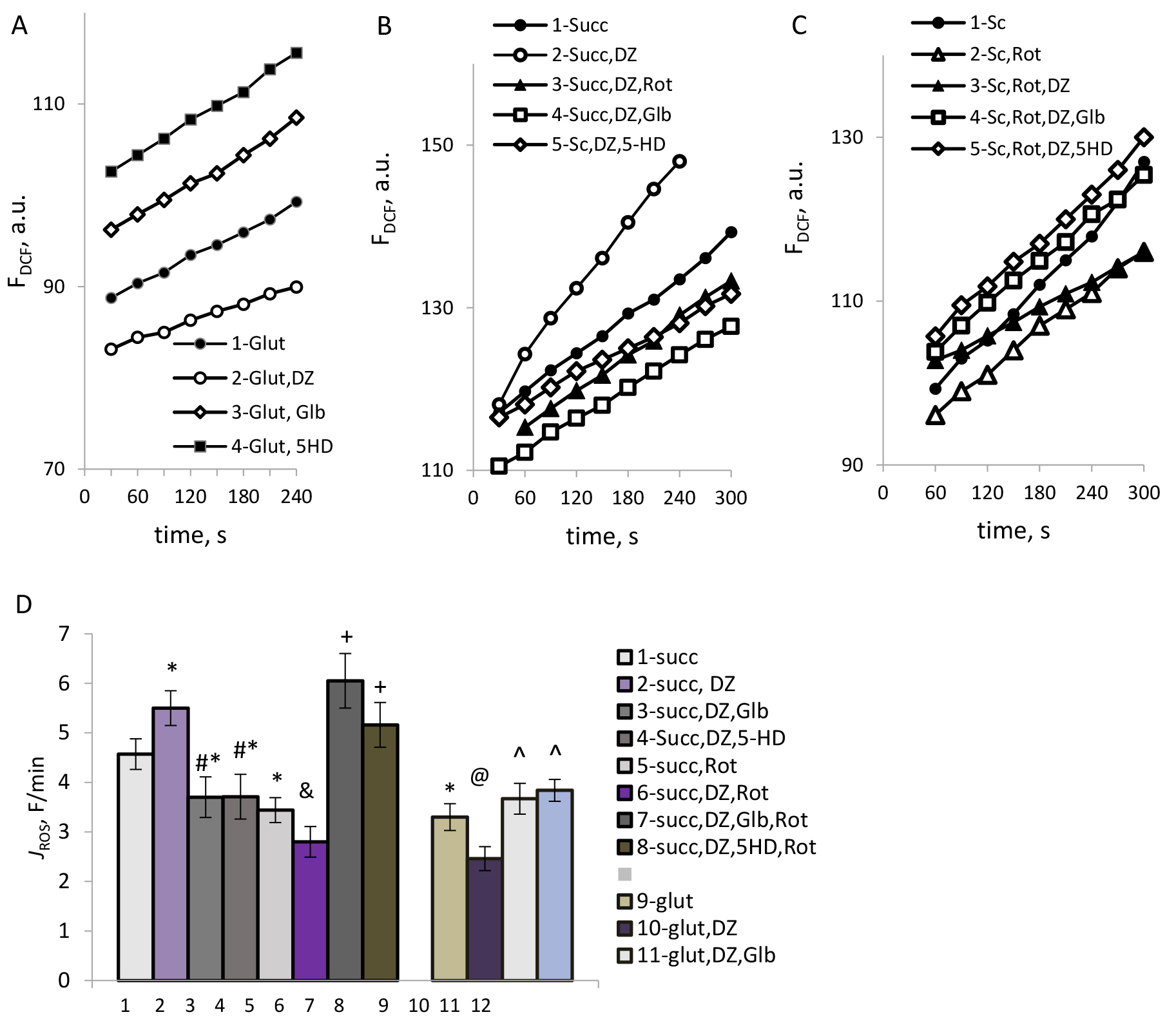

Complex effects of the mKATP channel modulators on ROS production were found, dependent on the respiratory substrate (Fig. 5). So, in mitochondria respiring on glutamate, DZ reduced ROS production (Fig. 5A), which was in line with our earlier data on liver mitochondria [31] and could be explained by the respiratory uncoupling and slight mitochondrial depolarization. Glibenclamide and 5-HD reversed this effect and increased ROS production (Fig. 5A), which correlated with the repolarization of mitochondria resulting from the blockage of the mKATP channel (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The effects of DZ and the mKATP channel blockers on ROS

production in mitochondria. (A–C) Typical time courses of dichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence in

mitochondria respiring on glutamate (A) and succinate (B,C). (D) The rate of ROS

formation, F/min. M

However, with succinate as a respiratory substrate, opposing effects were observed: DZ reliably increased ROS production (Fig. 5B, 1, 2). Diazoxide-stimulated increase in ROS production was suppressed by rotenone (Fig. 5B, 3), which could indicate the involvement of the reverse electron transport in the stimulation effect of DZ on ROS formation. In this case, too, activation of ROS formation by DZ was reversed by glibenclamide and 5-HD (Fig. 5B, 4,5), which indicated the involvement of the mKATP channels’ activity in this effect.

As we have found, after the blocking of reverse electron transport (RET) by rotenone, the mKATP channels opening by DZ reduced ROS production (Fig. 5C, 3), indicating the inhibitory action of DZ on ROS formation by forward electron transport. Similarly to what was observed with glutamate, in this case, blocking the mKATP channels by glibenclamide and 5-HD increased ROS production (Fig. 5C, 3). The results of the study of the impact of the mKATP channel modulation on ROS production under different conditions are summarized in Fig. 5D.

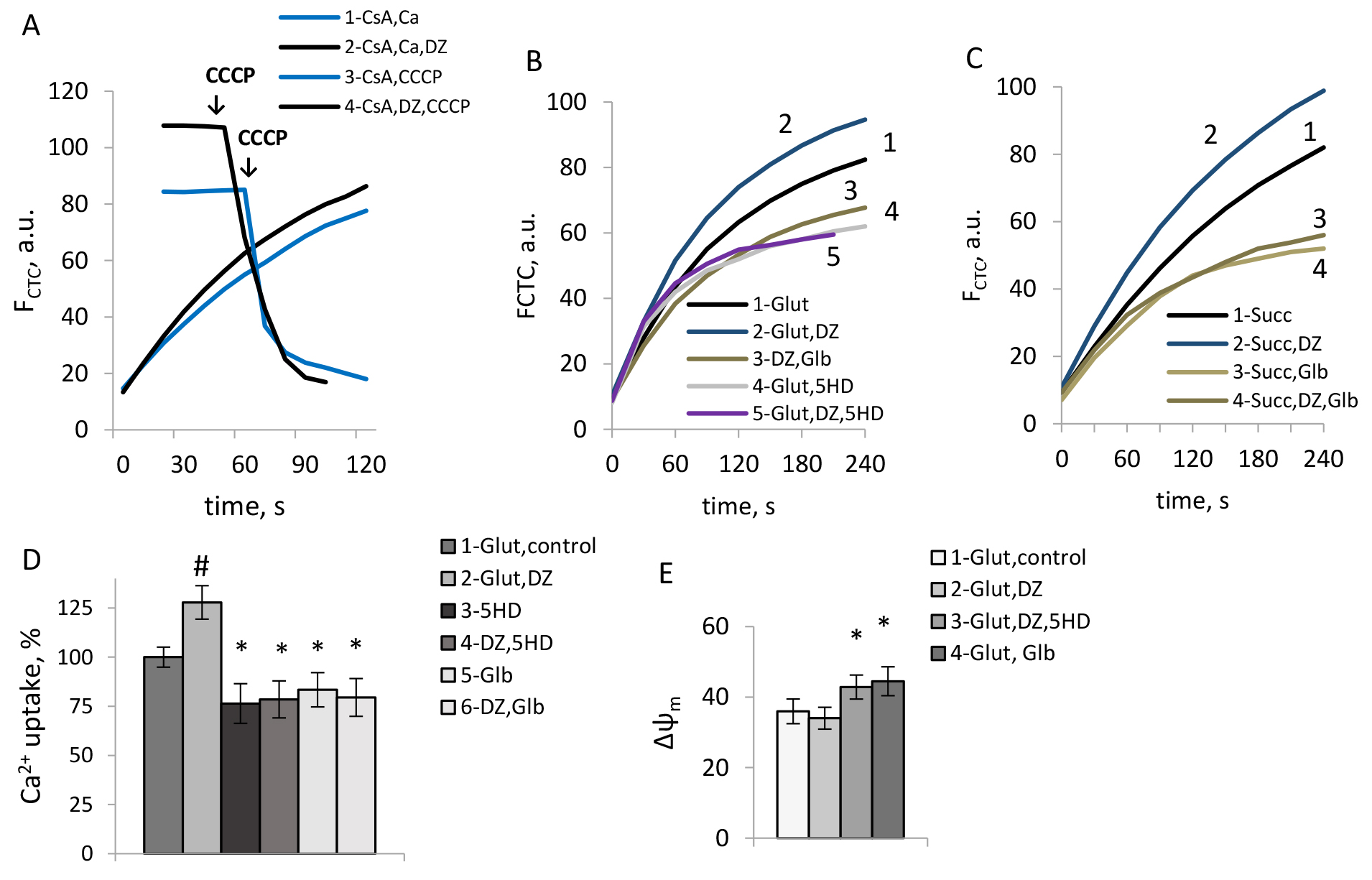

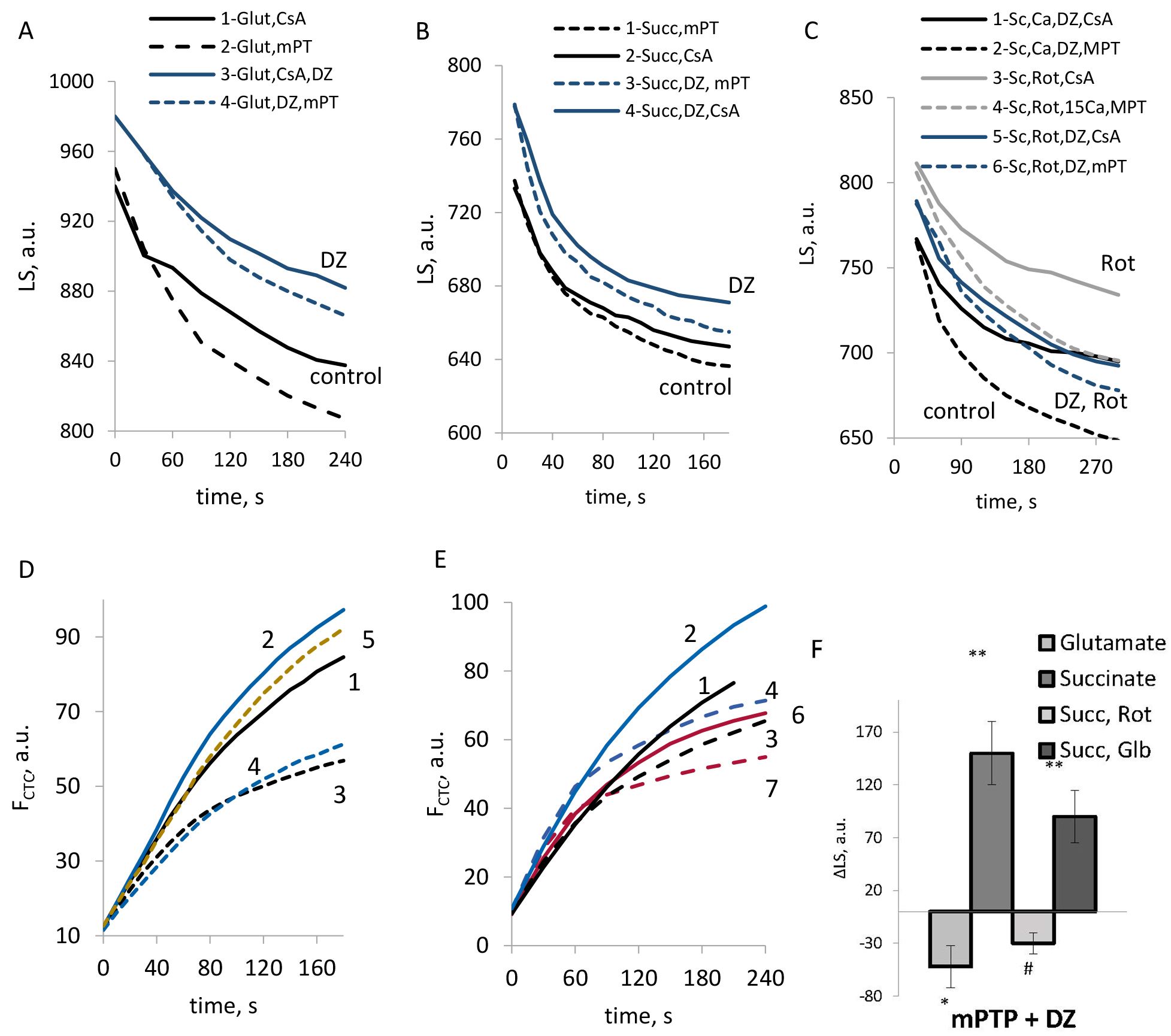

The mPTP opening was assessed by the light scattering as the cyclosporine-sensitive swelling of mitochondria. Representative traces reflecting the effects of DZ on the changes in mitochondrial matrix volume sensitive to cyclosporine A (CsA) under different conditions are shown in Fig. 6A–C. The data on the CsA-sensitive amplitude of mitochondrial swelling are summarized in Fig. 6F.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

The effects of DZ on the mPTP opening in rat brain

mitochondria. (A–C) Typical records of the light scattering in mitochondria

respiring on glutamate (A), succinate (B,C); with the addition of rotenone (C).

(D,E) Typical records of Ca2+ transport in mitochondria respiring on

succinate in the absence (dotted lines) and presence of CsA (solid lines) at the

additions of DZ, rotenone, and Glb; (F) CsA-sensitive swelling amplitude by the light scattering in the presence of DZ. (D,E) The number on the curves corresponds to: 1— succinate, CsA; 2— succinate, CsA, DZ, CsA; 3— succinate;

4— succinate, DZ; 5— succinate, rotenone; 6—

succinate, Glb, CsA; 7— succinate, Glb. (F) M

As we observed, the effect of DZ on the mPTP opening strongly depended on the respiratory substrate used. Independent of the stimulation of Ca2+ uptake by DZ, the regulation of mPTP opening strongly correlated with its impact on ROS production. DZ suppressed the mPTP opening when glutamate was used as a substrate. However, an mPTP opening was promoted by DZ in mitochondria, which respired on succinate. In the presence of rotenone strong mPTP inhibition was observed (Fig. 6C). While it was shown in the literature that rotenone could inhibit the mPTP independently of ROS formation [36], activation of the mKATP channel highly strengthened this effect (Fig. 6C). Obtained results indicated an inhibitory effect of the mKATP channels opening on ROS production under the conditions which allowed only for the forward electron transport in the respiratory chain. Suppression of ROS formation resulted in the mPTP inhibition in mitochondria respiring on glutamate and succinate in the presence of rotenone (Fig. 6A,C). However under the conditions when RET was observed, the mPTP was highly activated by DZ, which correlated with the stimulation of ROS production.

In line with these observations, with succinate as substrate, in the absence of rotenone, glibenclamide reduced the mPTP activity (Fig. 6E,F). Similarly to the effects of DZ, the opposing effect of glibenclamide on the mPTP activity in mitochondria respiring on succinate could be explained mainly by the regulation of ROS production. Thus, we can assume that glibenclamide could inhibit the mPTP opening in those cases when it reduced ROS formation simultaneously with the reduction of Ca2+ uptake, which caused an inhibition of the mPTP opening (Fig. 6E,F).

From the studies on sarcolemmal KATP channels, it was generally known that the sulfonylurea receptor (SUR) subunit, which binds pharmacological modulators of the KATP channels, possesses intrinsic MgATPase activity [37]. The mKATP channels opener diazoxide (DZ) and the blocker glibenclamide are the most studied of the pharmacological modulators of the mKATP channels known to produce their effects via the binding to the SUR subunits in the presence of MgATP. Multiple studies on isolated mitochondria generally assumed that the presence of Mg2+ and ATP was required for the functional effects of the mKATP channel openers and blockers [21, 22, 23]. However, literary data on isolated mitochondria were controversial, and the activation of ATP-sensitive K+ transport by DZ in the absence of MgATP was reported in heart mitochondria [24, 25] and in our previous studies on liver mitochondria [13, 31].

Earlier we have shown that the native liver mKATP channel was activated by DZ on a sub-micromolar scale without an MgATP, which implied that MgATPase activity was not a prerequisite for mKATP channel activation. So, it was interesting to study the pharmacological regulation of brain mitochondria KATP channel and the functional consequences of DZ and the blockers, glibenclamide, and 5-HD, on Ca2+ transport, ROS production, and the mPTP opening. To avoid several known off-target effects of DZ, we used a sub-micromolar concentration of this drug (0.5 µM) capable of fully eliciting ATP-sensitive K+ transport in liver mitochondria [31]. In this work, we have shown that the brain mKATP channel was similarly sensitive to DZ, which activated the mKATP channel on the low sub-micromolar scale, similarly in the absence of a MgATP. Besides, the mKATP channel blockers were also capable of fully blocking the ATP-sensitive K+ transport without a MgATP, which indicated that a MgATPase activity was dispensable for the pharmacological regulation of the mKATP channel.

Based on the present knowledge, mitochondria can possess more than one type of ATP-sensitive K+ conductance [26, 38, 39, 40]. Apart from the channel similar to plasmalemmal KATP channels composed of Kir/SUR subunits [37], renal outer medullary K+ channel (ROMK) channel [38], MitoK [39], and even ATP synthase [40] were proposed as K+ conducting subunits. However, despite the efforts to establish the composition of the mKATP channel, it remains elusive. A critical issue is identifying mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ transport by pharmacological means. From the studies on mitochondrial KATP channels [21, 22, 23], the native mKATP channel is blocked by MgATP, and the activated mKATP channel is blocked by KATP channel blockers (glibenclamide and 5-hydroxy decanoate) in the presence of a MgATP. So, to prove the identity of ATP-sensitive K+ transport with the mKATP channel on a pharmacological level, we developed an approach of combined blocking of ATP-sensitive K+ transport by MgATP and specific blockers of KATP channels glibenclamide and 5-HD. In addition to the light scattering method, we used an oxygen consumption assay, which allowed us to assess the mKATP channels activity ‘in situ’ by sequential adding the mKATP channels modulators to respiring mitochondria. As shown in the experiments, in the presence of a MgATP, no additional blocking of both native and activated ATP-sensitive K+ transport by either glibenclamide or 5-HD was observed. And vice versa, a MgATP could not block ATP-sensitive K+ transport blocked first by glibenclamide or 5-HD (Fig. 2), which proved the pharmacological identity of ATP-sensitive K+ transport studied in our work with the mKATP channel activity.

As we observed, the MgATPase activity was evenly dispensable for the functional effects of pharmacological modulators of the mKATP channel. Thus, DZ increased Ca2+ uptake in brain mitochondria, as opposed to the mKATP channel blockers glibenclamide and 5-hydroxy decanoate (5-HD). This agreed with our earlier study showing that native mKATP channel activity promoted Ca2+ uptake in brain mitochondria, which too was reversed by glibenclamide and 5-HD [29]. While in many works it was shown that the mKATP channel blockers increased Ca2+ uptake in mitochondria, in our works both glibenclamide and 5-HD reduced Ca2+ uptake despite mitochondrial repolarization caused by the blocking of ATP-sensitive K+ transport (Fig. 4E).

Meanwhile, DZ exhibited diversity in regulating ROS production and the mPTP opening. This differed from published works, where either ROS elevation or suppression was shown with consequent mPTP inhibition regardless of substrate. As we have found, the regulation of ROS production was dependent on the respiratory substrate used and the sites of ROS formation in the respiratory chain. Thus, DZ reduced ROS production with glutamate as substrate, but elevated ROS formation in mitochondria respiring on succinate, which effect was suppressed by rotenone. This diverse regulation of ROS formation was reflected in diverse effects on mPTP opening.

An increase in ROS production by DZ was observed in earlier published works [1, 11, 19]. So, in the works of Garlid’s group ROS production was increased in heart mitochondria respiring on Complex I substrate [1, 11], presumably because of conformational impairments in Complex I caused by mitochondrial swelling. However, in our work on liver mitochondria, ROS production on glutamate was suppressed by the mKATP channel opener, which correlated with mitochondrial uncoupling [31]. We can assume that the uncoupling effect of ATP-sensitive K+ transport in our studies on liver and brain mitochondria prevailed over the possible impact of K+ transport on the Complex I functioning, which stimulated ROS production, so that summary effect was the suppression of ROS formation observed in the works of many authors on different substrates [3, 11, 20]. In this work, we observed that DZ stimulated ROS production on succinate. Blocking this effect by rotenone might indicate the involvement of RET in stimulating the effect of DZ. Rotenone reduced ROS production on succinate regardless of the absence or presence of DZ. Interestingly, in the presence of rotenone, the activation of the mKATP channel reduced ROS production on succinate, similar to the effect of DZ on glutamate. So, we can assume that the activation of the mKATP channel suppressed ROS produced by the forward electron transport by the ‘mild uncoupling’ mechanism, i.e. mild depolarization caused by the activation of the K+ cycle.

However, we can assume that under the conditions that allowed both forward and reverse electron transport, the activation of the K+ cycle could stimulate electron transport in both directions, eventually resulting in the elevation of ROS production on succinate in the absence of rotenone. Accordingly, when RET was allowed, glibenclamide and 5-HD similarly reduced ROS production caused by the mKATP channel activation (Fig. 5B,D). On the contrary, when RET was blocked, and the mKATP channel activity reduced ROS production by the ‘mild uncoupling’ mechanism, glibenclamide and 5-HD increased ROS formation (Fig. 5C,D). A phenomenon similar to our observations was found earlier in heart mitochondria [25]. So, regarding ROS formation, we can assume that the mKATP channel’s opening could produce contrary effects on ROS production, depending on whether direct or reverse electron transport is allowed. In the first case, the mild uncoupling stimulated by the K+ cycle suppressed ROS production, as observed by many authors, including our earlier works, in the heart, liver, and brain mitochondria [3, 20, 30, 31]. However, in the last case, it was possible that the elevated rate of respiration following the activation of the K+ cycle could increase the rate of ROS formation.

Earlier it was shown the ability of DZ to modulate Ca2+ transients and promote the mPTP opening in ventricular myocytes [17]. However, in our work, the effects of DZ on the mPTP opening well correlated with the action of DZ not so much on Ca2+ transport, as on ROS production (Fig. 6). Despite the stimulation of Ca2+ transport by DZ (Fig. 4), we observed contrary effects of this mKATP channel opener on the mPTP activity (Fig. 6). Considering the high sensitivity of the mPTP channel to ROS production, we can suppose that under the conditions when DZ promoted ROS formation, i.e. with Complex II substrate in the absence of rotenone, it promoted the mPTP opening as well (Fig. 6B). In cases when ROS production was regulated by the effects of DZ on the forward electron transport (glutamate, succinate in the presence of rotenone), DZ reduced ROS production and inhibited the mPTP activity (Fig. 6C). Strong mPTP inhibition was observed in the presence of rotenone in mitochondria respiring on succinate (Fig. 6C). It is worth mentioning that rotenone was shown to inhibit the mPTP opening per se [36]. However, the activation of the mKATP channel strengthened this effect (Fig. 6C).

Thus, with succinate as a respiratory substrate, DZ promoted both Ca2+ uptake and ROS formation, which correlated with the stimulation of the mPTP opening. These effects were inhibited by glibenclamide, which reduced Ca2+ uptake and ROS production, thereby inhibiting mPTP activity (Fig. 6E). On glutamate, DZ inhibited the mPTP opening, however in this work, we were unable to establish reliable data regarding the effect of glibenclamide on the mPTP opening, possibly, because the mKATP channel blockers reduced Ca2+ uptake, while promoting ROS production, which were opposing effects related to mPTP activity. More experiments are required to find statistically reliable data in this case.

It is worth mentioning the limitations of our study. First, we could not assess the mKATP channel directly on a molecular level. This is critical to any work now, especially considering still existing uncertainties about the molecular composition of the mKATP channel [26, 38, 39, 40]. Furthermore, numerous off-target effects of DZ and other pharmacological modulators of the mKATP channel are known [26, 27, 28]. We largely avoided them in our study using low sub-micromolar concentrations of DZ and rather low concentrations of glibenclamide (5 µM). In many experiments, we ascertained that even ~2–5 µM of glibenclamide was sufficient for essential blockage of the mKATP channel without a MgATP. Besides, it needs a separate study, if there was no interference of an ATP with mKATP channel blockers in the combined blocking of the mKATP channel.

It is worth mentioning too that earlier in the works of Garlids’ group a

complicated mechanism of the mPTP inhibition by the mKATP channels opening

mediated by the activation of the mitochondrial protein kinase

Based on the experiments, we came to the following conclusions. (1) Brain mitochondrial KATP channel was highly susceptible to DZ, similar to liver mitochondria, which indicated common properties of mitochondrial KATP channels. (2) MgATPase activity was dispensable for the pharmacological regulation of the KATP channel in brain mitochondria and its functional consequences; the interaction of the mKATP channel with DZ, glibenclamide, and 5-HD could occur without a MgATP. (3) We hypothesize that a MgATP could screen certain high-affinity sites of the mKATP channel from the interaction with DZ, which allows for the mKATP channel activation by DZ on a sub-micromolar scale. In the presence of a MgATP, a switch to a well-established mechanism of the mKATP channels’ regulation occurs. (4) While Ca2+ uptake was similarly stimulated by DZ independently of the respiratory substrate, the Ca2+-induced mPTP opening was strongly dependent on the regulation of ROS production by the mKATP channel opening, which suppressed free radical formation by forward electron transport, while promoted oxidants production by reverse electron transport blocked by rotenone. Obtained results help explain diversity in the regulation of ROS by diazoxide reported in the literature, and show a high dependence of the mPTP regulation by the mKATP channels openers on mitochondrial energy state and ROS production.

mKATP channel, mitochondrial KATP channel; mPTP, permeability transition pore; DZ, diazoxide; Glb, glibenclamide; 5-HD, 5-hydroxydecanoate; CCCP, carbonylcyanide-m-chlorphenylhydrazone; DCF, dichlorofluorescein;

The experimental data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

OA designed the research study, performed the research, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript. AS provided help in conducting experiments, conducted statistical analysis, revised the draft of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The work has been carried out following ARRIVE principle and Council of Europe Convention on Bioethics (1997) approved by the Ethics Commission on Animal Experiments of A.A. Bogomoletz Institute of Physiology, NAS of Ukraine (protocol N1/23 of 11.01.2023).

We gratefully acknowledge an excellent assistance of Dr. Liudmila Kolchinskaya and Dr. Valentina Nosar in conducting the experiments.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.