1 Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2005, Australia

2 Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia

3 Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD 4058, Australia

Abstract

The microbiota-gut-brain axis has been proposed as a potential modulator of mood disorders such as major depression. Complex bidirectional biochemical activities in this axis have been posited to participate in adverse mood disorders. Environmental and genetic factors have dominated recent discussions on depression. The prescription of antibiotics, antidepressants, adverse negative DNA methylation reactions and a dysbiotic gut microbiome have been cited as causal for the development and progression of depression. While research continues to investigate the microbiome-gut-brain axis, this review will explore the state of persistence of gut bacteria that underpins bacterial dormancy, possibly due to adverse environmental conditions and/or pharmaceutical prescriptions. Bacterial dormancy persistence in the intestinal microbial cohort could affect the role of bacterial epigenomes and DNA methylations. DNA methylations are highly motif driven exerting significant control on bacterial phenotypes that can disrupt bacterial metabolism and neurotransmitter formation in the gut, outcomes that can support adverse mood dispositions.

Keywords

- intestinal microbiome

- bacteria

- epigenetics

- gut-brain axis

- mood disorders

- depression

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) depression affects an estimated 5% of adults globally, which is around 1 in 20 people [1, 2]. As of 2019, major depressive disorder (MDD) was among the most common and complex mental conditions with a global incidence of approximately 280 million people that had been diagnosed with MDD [1]. Current prescribed antidepressant medications are intended to increase the level of serotonin with serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors, dopamine (e.g., sertraline), noradrenaline (e.g., desipramine), or a combination of these neurotransmitters with the use of serotonin-noradrenaline specific reuptake inhibitors or inhibit monoamine oxidase enzymes that degrade these neurotransmitters (e.g., monoamine oxidase inhibitors) [3, 4]. Neurotransmitters participate in complex biochemical reactions that regulate mood, cognition, motivation, intellectual function and executive functioning comprising necessary aspects of social societal functioning [5]. The disruptions that can occur to neurotransmitters including that of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and the glutamatergic systems can progress MDD [6].

Notwithstanding this large body of research and large epidemiological genome association studies have reported a low to moderate heritability relationship to depression [7]. Moreover, only small genetic variant effects have been identified in large genome-wide association studies of depression [8, 9]. Together these studies necessitate an alternative research approach that posits mechanisms for depression that are beyond the genetic framework in order to identify biological pathways for depression that have strong environmental drivers [8, 9]. Currently there is extensive consensus for the participation of the microbiota-gut-brain axis interacting in health as well as in disease conditions of mood disorders [2, 10, 11, 12]. However, the mechanisms by which microorganisms shape aspects of brain functioning such as memory and social behaviour, and how they might contribute to conditions such as depression and neurodegenerative disease, are often controversial and not well understood [13].

Standing as potential moderators of the gut-brain axis are antibiotics. A recent systematic review has investigated the role of different classes of antibiotics and the effects imparted on the intestinal microbiota. They report profound effects on the intestinal cohort of bacteria [14]. In particular, amoxicillin/clavulanate, ciprofloxacin, minocycline, clindamycin, paromomycin and clarithromycin plus metronidazole were associated with decreased bacterial diversity [14]. It is generally agreed that bacterial persistence has evolved as a potent survival strategy that bacteria employ to overcome adverse environmental conditions as so happens with the administration of bactericidal antibiotics [15]. It has been reported that bacterial persister cells are metabolically repressed, a protective mechanism that these cells express from killing by most classes of bactericidal antibiotics [15]. Given that intestinal bacteria can produce high concentrations of neurotransmitters especially serotonin of which the latter has been posited to be mostly present in plasma [16], it is plausible that persister bacteria following antibiotic administration, or through reverse epigenetic signalling could effectively reduce the circulating levels of plasma neurotransmitters such as serotonin, with metabolic effects consistent with adverse mood dispositions. This review will investigate bacterial persistence and epigenetics and what function it may have in mood disorders.

Research investigations have accumulated data over the past two- or more decades that implicates the intestinal microbiota as a significant influential participant in brain activity, behavior and neuropsychiatric disorders [17]. The mechanism operating involves a bidirectional pathway loop through neural and humoral pathways from the gut to the central nervous system and back to the gut [18, 19, 20]. Several animal studies suggest that the gut microbiota might have a significant impact on the neurobiological features of depression [21, 22, 23, 24]. For example, human fecal microbiota transplantation from either stressed or obese participants to microbiota-deficient rats showed significant alteration of anxiety [25]. Similarly, Kelly and colleagues [25] showed that transferring gut microbiota from depressed human patients to germ free rats induced behavioral and physiological features characteristic of depression in the recipient animals. These findings suggest that the gut microbiota may be involved in causal pathways leading to depression.

One important measure of gut microbiota activity is diversity. Alpha-diversity is defined as the observed richness (i.e., number of taxa) or evenness of the relative abundances of those taxa in an average fecal sample collected from the gut [26]. Whereas beta-diversity purports to quantify the relative variability that is present in the bacterial composition of the communities (i.e., of the identity of the taxa observed) from fecal samples obtained from the gut [26]. Decreased alpha and beta-diversity are well accepted as a strong indicators of an unhealthy gut microbiome [27], linked to different chronic conditions such as obesity and type 2 diabetes [27].

Liu and colleagues [28] report that preclinical and clinical studies support the notion that adverse gut-brain interactions that are present in depressive disorders emanate from gut dysbiosis. Clinical studies have been recently summarized by Xiong and colleagues 2023 [29]. Mechanistically the studies presented by Xiong et al. [29] show a trend that demonstrates that changes that reflect a reduced abundance that can occur in the gut microbiota in important commensal species such as those from Faecalibacterium spp., Butyricicoccus, Ruminococcaceae, Agathobacter, Coprococcus, and Roseburia can disrupt the balance of the gut microbiota progressing dysbiosis. Concurrently it has also been reported that gut commensal dysbiotic disruption adversely affects the production of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as a decrease in butyrate production an important molecule that benefits hematological (e.g., reducing proinflammatory activity in the gut) and non hematological structures in the gut (e.g., improving intestinal cell tight junction permeability) [30]. Concomitantly gut dysbiosis is exacerbated with the increased abundance of pathobiont species from Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Coriobacteria and Fusobacteria [29].

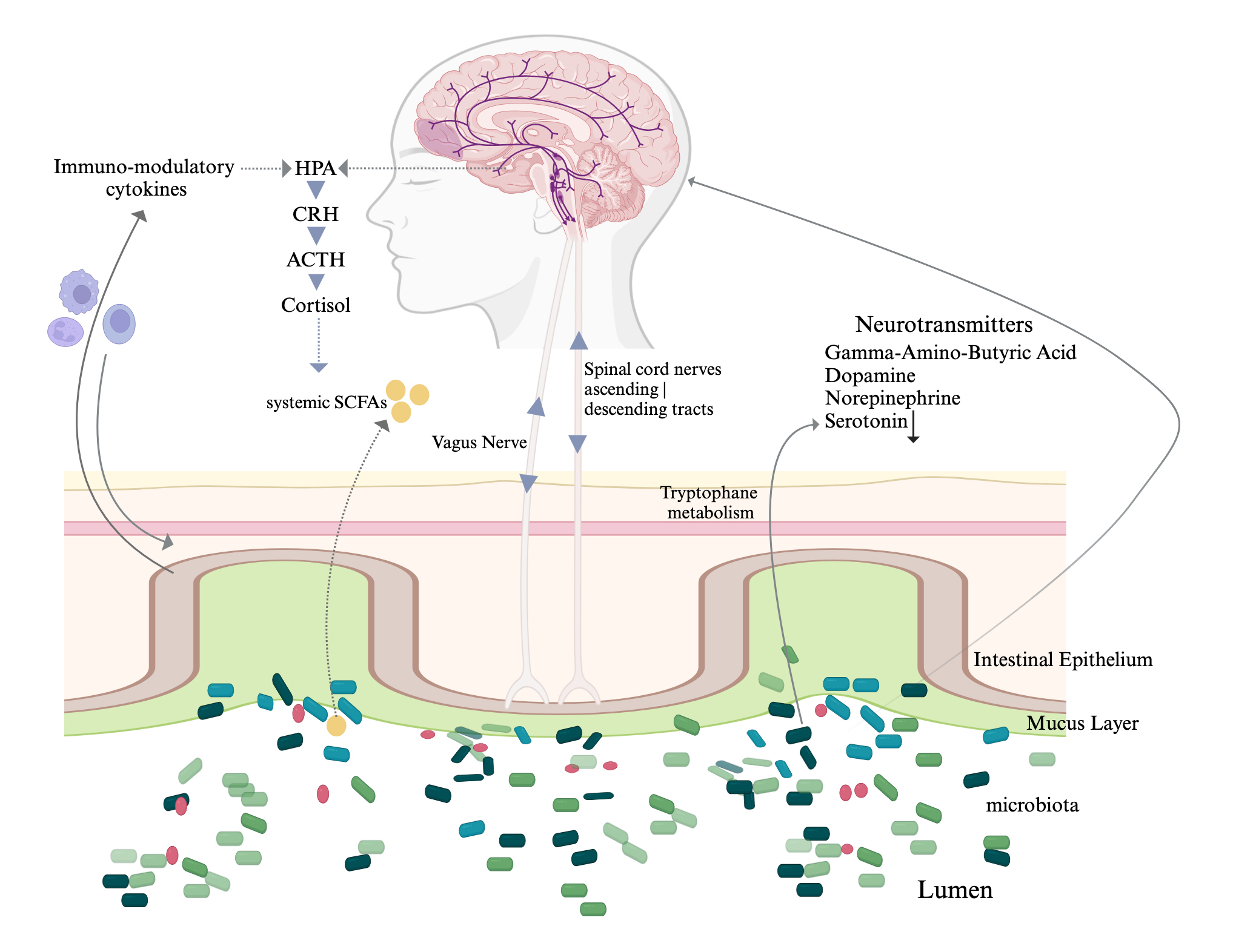

The mechanisms by which microorganisms shape aspects of brain functioning such as memory and social behaviour, and how they might contribute to conditions such as depression and neurodegenerative disease, are still in debate. Aside, there is a complexity of bidirectional interconnections that support the ideas posited, relevant to the multiple biochemical components that underpin the microbiota-gut-brain axis (Fig. 1, Ref. [31, 32]). The underlying mechanism of mental illness pathogenesis has a complex profile and includes the interplay of various key factors related to genetic, epigenetic, and the host immune system, and exogenous environmental factors. Current knowledge of the molecular events that underlie depression, still in part supports the monoamine hypothesis of depression. The molecular events that trigger depression that supports observations that pivot towards the complexity that is the monoamine hypothesis of depression [33, 34]; fits to a gut link of neurotransmitter combination complexity (e.g., serotonin, norepinephrine, and/or dopamine depletion) in the central nervous system neurotransmitters emanating from the gut microbiota. Hence any environmental distress that affects a complex combination of levels of brain serotonin, dopamine, or norepinephrine signalling pathways may induce or exacerbate symptoms of depression [35].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Diagrammatic representation of the interconnections in the

microbiota-gut-brain axis with neurotransmitters that are elaborated in the gut

by the intestinal microbiota. The vago-vagal reflex loop is composed of vagal

nerve afferents and efferents of the vagal nerve. Vagal nerve afferent fibers

cannot access directly the intestinal microbiota but rather can sense various

intestinal mechanical and chemical signals in the gut that can lead to different

behaviours and effects [31, 32]. We note that

Notwithstanding, a recent study reported the depletion of butyrate producers in the gut (i.e., Coprococcus and Dialister) in individuals diagnosed with depression [36]. It is reported from clinical studies that butyrate producing intestinal bacteria such as Clostridium butyricum [37], Faecalibacterium [38] and Coprococcus [39] have been consistently associated with higher quality of life indicators [39].

In a recent gut-wide association study [40] fecal microbiome diversity and composition was associated with depressive symptoms. This study investigated samples from 1054 participants from the Rotterdam Study cohort and validated the data in the Amsterdam HELIUS cohort in 1539 participants [40]. In addition, a parallel study that investigated the association of the intestinal microbiome with depressive symptoms in the multiethnic HELIUS cohort (study limited by major confounders in the ethnic groups studied) identified genera/species belonging to the families Christensencellaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Ruminococcaceae as being consistently associated with depressive symptoms across the six major ethnic groups studied. The most consistent associations were reported for the genera Eggerthella, Coprococcus, Subdoligranulum, Mitsuokella, Paraprevotella, Sutterella and family Prevotellaceae [41]. In a follow-up study to the Dutch participants of the HELIUS cohort, the Rotterdam study that methodologically controlled for lifestyle factors and medication use, reported an association of thirteen microbial taxa, that included genera Eggerthella, Subdoligranulum, Coprococcus, Sellimonas, Lachnoclostridium, Hungatella, Ruminococcaceae (UCG002, UCG003 and UCG005), Lachnospiraceae UCG001, Eubacterium ventriosum and the Ruminococcus gauvreauii group, and the family Ruminococcaceae presented with depressive symptoms [40]. Although contentious there is agreement that these bacteria are known to be involved in the synthesis of key neurotransmitters such as glutamate, butyrate, serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) which may involve complex combinations of neurotransmitters that may be mechanistically linked to depression [40]. Consistent with this study it has been reported that more than 90% to 95% of the body’s serotonin is synthesized in the gut [16, 42]. Various bacteria such as Streptococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., Escherichia spp., Lactobacillus plantarum, Klebsiella pneumonia, and Morganella morganii have the ability to produce serotonin [42]. Research shows that changes in the gut bacterial cohort and associated metabolites can encourage stress related responses as well as social behaviour in patients diagnosed with depression. Bacterial metabolites can alter the tone of immune cells and neurogenesis in the brain facilitated by epigenetic changes [42]. Such research provides a viable alternative narrative to the genetic model for understanding the pathways affecting key neurotransmitters implicated in the onset and maintenance of depression.

Moreover, a large health study has reported the link that exists between the intestinal microbiome and depression [10]. Qin and colleagues (2022) [10] reported two bacteria that were causal for hospital acquired infections namely, Morganella and Klebsiella, also appeared to play a causal role in the progression to depression. Moreover, Morganella, was significantly increased in a microbial survey of 181 participants in the study, who later were diagnosed to have developed depression [10]. In a recent murine models of dysbiosis of the gut microbiome was reported to possibly have a causal role in the development of depressive-like behaviors, in a pathway that is mediated through the host’s metabolism [43, 44]. In addition, there is recent evidence that there are unique gut microbial profiles for individuals diagnosed with MDD presenting with and without anxious distress [45, 46]. Moreover, there is evidence through randomised controlled trials that the ingestion of probiotics can significantly reduce depressive symptoms in adults with MDD [46, 47]. As such, these studies illustrate examples of a range of emerging studies identifying specific gut bacteria implicated in the pathogenesis of depression in humans.

It has been reported that more than 90% of the serotonin produced is synthesized in the intestines [6, 48]. Bacterial species from Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Escherichia as well as Lactobacillus plantarum, Klebsiella pneumonia, and Morganella morganii have been reported to produce serotonin [48, 49]. It has been advanced that decreased abundance of particular bacteria in the intestinal microbiome could vary the biosynthesis, release, and reuptake of neurotransmitters [50, 51]. Dysbiotic changes that result in a disturbance in the intestinal microbiota could adversely influence the biochemistry that is operating between the central nervous system (CNS) and the enteric nervous system that could lead to emotional distress [50, 52]. The reciprocal two-way interactions between the CNS and the intestines emphasizes how the intestinal microbiome and neurotransmitters participate in emotional distress dispositions [53]. A study of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients versus healthy controls showed significantly decreased plasma levels of serotonin and norepinephrine in the IBS group with emotional distress versus healthy controls [50]. Negative associations have been reported with microbiota Shannon and Simpson indices relative to alpha diversity in the gut microbiota and norepinephrine levels [50]. Additionally, plasma serotonin levels were positively associated with the abundance of Proteobacteria. When interpreting association levels of norepinephrine the hormone correlated positively with the phylum Bacteroidetes and negatively with the phylum Firmicutes. The importance of this study is the observation that there was adverse modulation of the intestinal microbiome in those diagnosed with an intestinal disease (i.e., in patients diagnosed with IBS) who were emotionally distressed compared to healthy controls. Furthermore, the data that correlated plasma neurotransmitter levels and the intestinal microbiome indicated that the gut microbiome may significantly impact neurotransmitter regulation [50]. Further, the research consensus supports the contention that there are other neurotransmitters such as dopamine and norepinephrine that are elaborated by bacteria. Neurotransmitters can be elaborated by bacterial groups that include members from the Lactobacillus, Serratia, Bacillus, Morganella and Klebsiella genera [54]. Moreover, reports demonstrate that the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine can stimulate the growth of E. coli O157:H7 [55, 56, 57].

Epigenetic changes occur as genetic modifications that influence gene activity from DNA methylations, histone modifications, and microRNA producing heritable phenotypic changes without altering the DNA sequence [58]. Epigenetic mechanisms have been reported to operate in different settings namely in neurotransmission signalling [59], cancer and cancer virus metabolism [60, 61], metabolism in trained immunity [62] and bacterial metabolism [63]. It has been hypothesized that epigenetic processes are driven by environmental and genetic factors, and that these factors are directly implicated in the development and progression of depression [64]. Epigenetic processes have an integral role in normal biological pathways as for example with cellular differentiation. However epigenetic changes have also been directly implicated in disease states [64]. Major depressive disorder is significantly influenced by environmental and genetic factors of which epigenetic mechanisms may be a contributing factor [64]. A recent review further summarizes the regulatory function that the intestinal microbiome has on the CNS through neuronal, chemical and immune pathways, proving the bidirectional communication between the intestines and the brain [65]. This bidirectional crosstalk is believed to be linked to the etiology of depression. Further to this, it is now evident that an additional mechanism that contributes to depression is the control of the epigenetic machinery of the host by the intestinal microbiota [66]. Epigenetic regulation data has reported that these outcomes are critical in facilitating key gene expressions linked with neurotransmitter biochemical pathways, comprising neurotransmitter receptor and transporter genes [66]. It is plausible then that as the gut microbiota exerts control over the host epigenetic machinery in depression, gut dysbiosis could cause negative epigenetic modifications through influencing mechanisms like histone acetylation, DNA methylation and non-coding RNA mediated gene inhibition [66], that in turn could significantly affect the levels of neurotransmitters produced in the gut.

The diversity and abundance of the intestinal microbiota is posited as a key factor in serotonin and dopamine production. These neurotransmitters have significant roles in delaying or accelerating depression through the biochemical regulation of tryptophan availability and, subsequently, through the synthesis of serotonin in the intestines and brain cells [67, 68]. The gut microbiota hence assumes greater importance in this process when intestinal microbiome–derived metabolites (e.g., butyrate) enhance the expression of the enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase 1 with increased activity where the protein catalyzes the conversion of tryptophan to produce serotonin [48, 69]. The bidirectional flow of biochemical interactions is evidenced from the production of serotonin in the gut that influences brain functions through stimulation of the vagus nerve [67]. Also, the report concludes that the levels of serotonin found in blood affect the permeability of the blood-brain-barrier [67]. It has also been documented that enteric produced butyrate embraces similar effects as epigenetic drugs (e.g., sodium valproate) promoting the production of neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine, noradrenaline, and other related neurotransmitters), this through augmenting the transcription of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene which is the enzyme involved in the synthesis of serotonin [70].

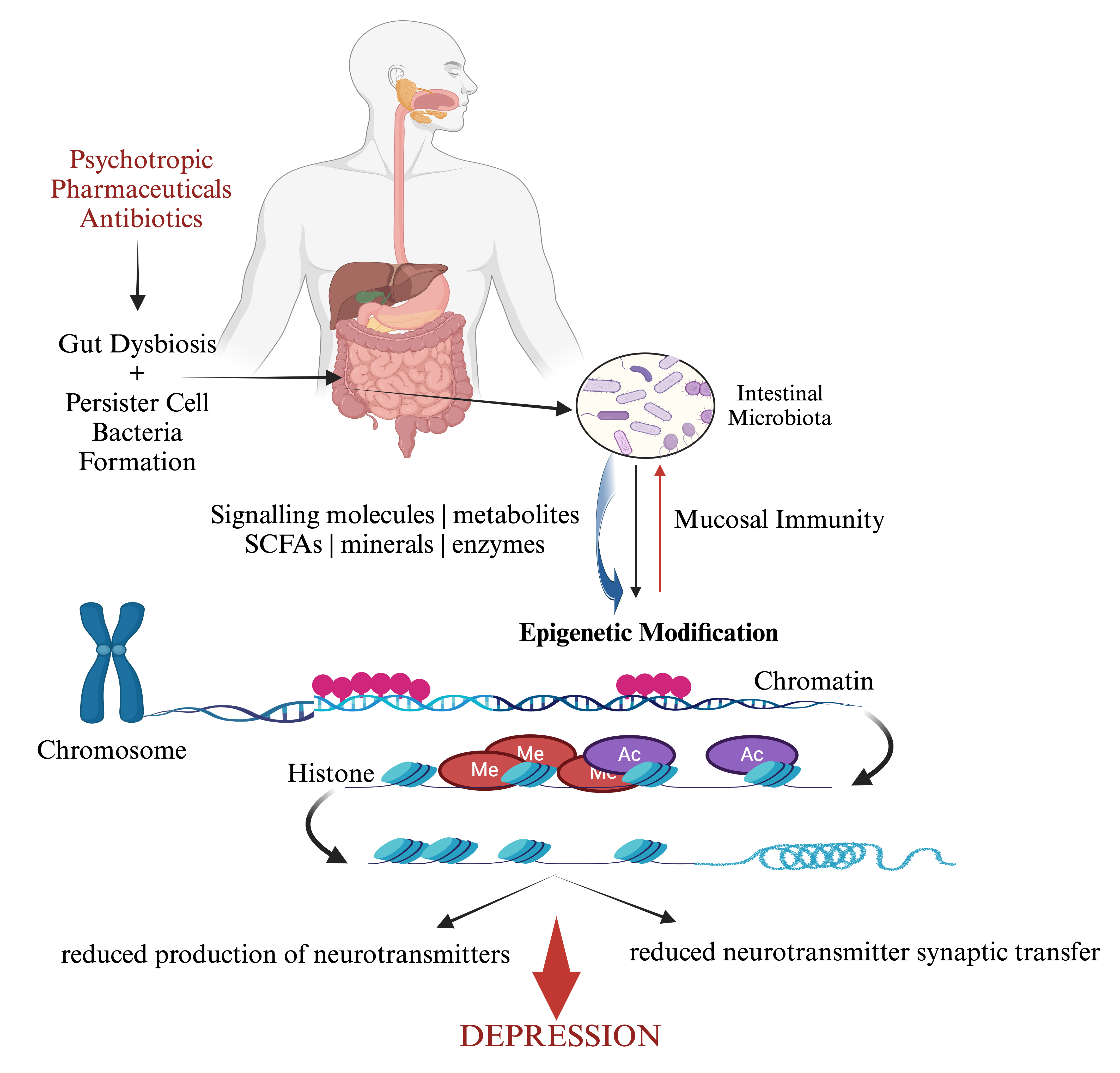

The epigenetic changes that ensue due to endogenous or exogenous environmental triggers could influence depression, especially if there are host genetic links with the gut microbiome (Fig. 2) [71, 72]. Typically, the gene that encodes an essential membrane protein sodium-dependent serotonin transporter and solute carrier family 6 member 4 (i.e., SLC6A4) is documented to transport the serotonin from synaptic spaces into presynaptic neurons [73]. Contentious studies have reported the association between SLC6A4 DNA methylation and depression [73, 74, 75, 76]. It is known that depressive disorders have also been linked to DNA methylation in the 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor (5-HTR) family, with an overall impression that various investigators have posited that a link exists between SLC6A4 methylation and depression [66]. This progresses the impression that intestinal dysbiosis could be causal for epigenetic modifications [65]. A consequence of epigenetic actions in the gut microbiota during stressful environment triggers, is that cellular DNA methylation status modulates global gene expression patterns to assist in promoting bacterial dormancy [77]. Bacterial dormancy is the mechanism by which bacteria survive adverse environmental conditions. Bacteria can progress to a dormancy state to become spores that allows biological processes to be put on hold. As such these biologically inert cells allow bacteria to wait out periods of adverse environmental effects as so happens with the presence of antibiotics in the gut microbiota.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Psychotropic pharmaceuticals and antibiotics progress adverse interactions with the intestinal microbiota that influence epigenetic changes that give rise to an elevated risk for depression. Equally epigenetic changes can also affect mucosal immunity prompting homeostasis effects in the gut. Created with BioRender and further edited by the authors.

The administration of antibiotics has resulted in the emergence of numerous

reports linking depression with the prescription and use of antibiotics [47, 78, 79].

Moreover, recent reviews have demonstrated and further confirmed that depression

is triggered from a disrupted intestinal microbiome [28, 80] that consequently

could be further exacerbated from frequent antibiotic exposure [81]. An early

review has advanced the depressogenic effects of prescribed medications [82].

Several medications, (e.g., barbiturates, vigabatrin, topiramate, flunarizine,

corticosteroids, mefloquine, efavirenz, and interferon-

Also present in the gut are the antimicrobial effects that psychotropic pharmaceuticals can impart on the gut microbiome. A recent study reported on the reduction of virulence by bacterial pathogens through a mechanism that increased sensitivity to antibiotics [85]. This was shown by the effect of loxapine, a drug that is known to suppress antibiotic-resistant intracellular pathogens [86]. This biochemical mechanism employed the inhibition of the bacterial efflux pump activity. Additional similar mechanistic murine model study reported on how phenothiazines and tricyclic antidepressants can disrupt and render a curative effect to bacteria that carry a susceptibility plasmid that is sensitive to antibiotics [87]. Moreover, fluoxetine and thioridazine have been shown to reduce biofilm formation from the activity of the uropathogens Proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa that are present in the intestines [88]. These results confirm that pharmaceutical drug suppression of bacterial growth activity in the intestines is not always favorable. Antipsychotic pharmaceuticals have been shown to alter gut bacteria short chain fatty acid production that can exacerbate the common side effects of treatment failure for depression by affecting the alpha diversity of the gut microbiome [89].

Studies also note that the long-term exposure to psychotropic pharmaceuticals, that possess antimicrobial effects that mirror antibiotic treatments, have been posited to promote the development of antibiotic resistance [90, 91]. For example, sertraline and duloxetine have been shown to enhance antibiotic resistance by altering the tone cellular redox potentials skewed towards pro-inflammatory activity, the expression of efflux pumps, conjugative plasmid transfer, and the genesis of persister cell formation [92].

Persister bacteria are a sub-population of bacteria defined as dormant variants of regular cells that form stochastically in microbial populations and are highly tolerant to pharmaceutical drugs and escape a lethal dose effect from antibiotics [93] and develop due to metabolic inactivity. Moreover, persister bacteria demonstrate slower killing characteristics in response to a stress [94]. Gut bacteria can become physiologically dormant when lethal stress factors ensue. Bacterial dormancy is characterized by a significant growth rate reduction and metabolic activity, triggering a state of deep ‘sleep’, labelled as persistence [95]. It has been reported that persistence is likely a universal resting state of all bacteria [96]. With relevance to antibiotic resistance, the extraordinary ability of bacteria to switch between an active and an inactive state is seen as the main cause of antibiotic treatment failure and the relapse of bacterial infections and resistance to host immunity [97]. Furthermore, the prescription of antidepressants has been reported to induce mutations and enhance the degree of persistence bacteria toward multiple antibiotics [92]. Recently it was reported that intestinal microbial communities that are frequently exposed to antidepressants could negatively interact with antibiotics leading to resistance [98]. Lu and colleagues [98] aimed to investigate resistance and showed that antidepressants can accelerate the dissemination of antibiotic resistance by increasing the rate of the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes.

The production of neuroactive metabolites, such as neurotransmitters or their precursors, by the gut microbiota can affect the concentrations of related neurotransmitters, their precursors, or both, in the brain [99, 100]. This suggests that the neurotransmitter synthesis pathway in the intestines may be directly or indirectly affecting the neuronal activities and cognitive functions of the brain [101, 102]. A related mechanism that can affect the production of gut derived neurotransmitters is the reduction of bacterial metabolites. Intestinal microbial-derived metabolites (e.g., butyrate) can act as signalling molecules to induce the synthesis and release of neurotransmitters by enteroendocrine cells [48]. Hence, changes in signalling metabolites reflects an altered composition of the intestinal microbiota correlated with depression [50]. Prescribed antidepressants can augment the spread of antibiotic resistance that could further enhance persister bacteria in the gut [103]. As such, we posit that treatment resistance to antibiotics and antidepressant medications may, at least in part, be due to the increase in the dormancy of gut bacteria that are involved in reduced neurotransmitter synthesis pathways that could then promote and maintain depressive symptoms.

With relevance to depression and mood dispositions, the formation of persister cells establishes phenotypic heterogeneity within a bacterial population. This has been hypothesized to be of importance as it will increase the probability of adapting to environmental changes [104]. Moreover, the presence of persister cells in the intestines can result in the recalcitrance of persister bacteria that leads to non-response to antidepressant medications [104]. This finding has important implications given that the burden of treatment resistant depression has an exponential increase. That is, that the longer it persists, the higher the risk of impaired occupational and social functioning, losses in quality of life, somatic morbidity and suicidality [105]. In a recent 4-week, placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial of the antibiotic minocycline (200 mg/day) added to antidepressant treatment, the study showed evidence of efficacy of an add-on treatment for patients diagnosed with treatment resistant major depression [106]. Consistent with this result was the correlation to a study that showed that an antibiotic (i.e., minocycline) can control persister cells by leveraging dormancy associated reduction of drug efflux [107].

Could prescribing probiotics and other functional molecules rescue the gut from the adverse effects of persistence bacteria and improve the efficacy of antidepressant medications [108]? A recent review has reported that multi-strain probiotics and magnesium orotate treatment could be beneficial in patients diagnosed with both digestive and psychiatric symptoms [109]. This is important given that bacterial persisters are thought to underlie chronic infections and can lead to an increase in antibiotic-resistance as well as antidepressant generated mutants in progeny cells. We note though that probiotics may be useful in interfering with persister cell resuscitations. This was demonstrated and clarified how antidepressants at clinically relevant concentrations, induced resistance to multiple antibiotics [92]. This effect was confirmed in another study that showed that following short periods of exposure to antidepressants, a probiotic exploratory clinical study (i.e., E.coli Nissle, E. coli MG1655 [a K-12 strain]) reported beneficial effects in inhibiting the persister bacterial phenotype resuscitating bacterial cells following antibiotic treatment [110].

A perspective view that accepts and lists the intestinal microbiome as a central complicit participant that influences the nervous system, it does so through continuous direct and indirect signalling mechanisms that encompass chemical transmitters, neuronal pathways, and the immune system [85, 111]. At the time of this review no studies were found that examined persister bacteria in the microbiome and their innate antibiotic resistance in relation to treatment resistant depression (TRD). Although, following the existing research into the gut microbiome, inflammation, antibiotic use, and depression, we argue that the relationship between persister bacteria in the microbiome and the role of antibiotic resistance as a causal factor in progressing TRD through a number of mechanisms. Firstly, the intestinal microbiota contains a diversity of bacteria and persister cells that are present as a sub-population, plausibly forming a reservoir of antibiotic tolerant cells with capabilities of evading host immunity, most likely through their concentration in biofilms [104, 112]. Michaelis et al. [85] in their recent review posit how xenobiotics, psychotropic drugs can affect the physiology of the gut microbiome with effects that alter the biochemical tone of signalling along the gut-microbiome-brain axis [85].

While persister bacterial cells are largely thought to be dormant they still have low levels of metabolic activity and may interact with other bacteria in detrimental ways. Firstly, the prevalence of persister bacteria affects microbiome diversity through the loss of competition for colonisation space and nutrients. Secondly, there is reduced signalling between microbiome populations and the down regulation of the function of neighbouring bacteria through activating stress responses and altering gene expression, the production of microbial metabolites, neurotransmitters, and immune modulating molecules. Thirdly, persister bacteria may also increase antibiotic resistance through horizontal gene transfer or other shared resistance mechanisms increase the pool of bacteria in the microbiome with similar molecular dynamics [104, 112]. The relationship with TRD and persister bacteria antibiotic resistance may be even more complex as antidepressants can confer similar epigenetic changes by modifying chromatin structure and promote resistance via horizontally conjugative gene transferor between cells as well as the expression of genes involved in antibiotic resistance and persistence, parallel with those demonstrated by persister cells [43, 44, 112, 113]. Most investigation has been on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which can affect bacterial growth, metabolism, and gene expression which interact with bacterial serotonin receptors or other molecular targets [98, 103]. Antidepressants have also shown properties that modulate bacterial stress responses, biofilm formation, and virulence factor expression in various bacterial species which also potentially increase antibiotic resistance and TRD mechanisms [98, 103, 112].

It is plausible that as colonies of persister bacteria develop, the ensuing gut microbiome and neurotransmitter production becomes impaired to the point where there may be greater resistance to standard treatments for depression for the host. This mechanism might be mediated by the impact of antibiotic resistance, which can be shared with neighbouring bacteria as well as other negative down regulation effects. This is likely complicated using antidepressant medication in TRD which might modify bacterial metabolism in a way that mimics persister bacteria activities. This might help explain why poly-pharmacy is often required for TRD rather than traditional monotherapy and why the uniquely effective antibiotic-broad spectrum anti-inflammatory drug minocycline, and other anti-inflammatory medications, and probiotics to varying degrees have proved useful in cases of TRD [105, 106].

Depression remains a complex and multifaceted disorder with mechanisms that extend beyond the traditional monoamine hypothesis. The role of the gut microbiome, and the impact of persister bacterial populations on inflammation and neurotransmitter production, presents a compelling framework for understanding TRD. Existing evidence suggests that dysbiosis, gut-derived neuroinflammation, and epigenetic modifications driven by persistent bacterial populations may contribute to both the onset and maintenance of depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the interplay between antidepressants, antibiotic resistance, and microbiome composition appears to play a critical role in shaping treatment outcomes. While emerging studies indicate that microbiome-targeted interventions, such as probiotics and prebiotics, may hold therapeutic potential, further investigation is required to determine their efficacy in TRD [114]. Given the clinical relevance of these mechanisms, future research should prioritize exploring adjunctive therapies that aim to restore microbial balance, mitigate bacterial persistence, and enhance the gut-brain axis function.

Future clinical research should prioritise identifying bacterial markers linked to TRD, assessing antibiotic exposure in depressive pathophysiology, and clarifying gut microbiota interactions with psychotropic medications to develop more effective, personalised treatments. Addressing mood disorders may also require targeting gut microbiota imbalances, particularly those linked to pro-inflammatory activity and increased intestinal permeability.

Emerging evidence suggests that low-grade systemic inflammation plays a key role in altering brain activity and behaviour. A pilot open-label RCT found that prebiotic fibre improved gut inflammation, mood, stress, and anxiety. However, probiotic studies have yielded mixed results [115, 116, 117]. An eight-week double-blind RCT with Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 showed no significant improvements in depression, inflammation markers, or intestinal permeability. In contrast, another RCT with Bifidobacterium breve BB05 showed promise in alleviating psychosomatic diarrhoea and mental health symptoms. Similarly, a 2023 RCT in healthy young adults found that a multi-strain probiotic improved mood, anxiety, and depression scores over six weeks, alongside increased serotonin levels [117]. A 2024 meta-analysis also suggested that Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium longum may have a stronger impact on reducing depressive symptoms [118].

Further research is needed to refine microbiome-based interventions and integrate them with existing treatments. While the potential for probiotics in mental health is promising, robust RCTs are essential to establish their clinical efficacy. The potential for microbiome-based interventions to complement existing pharmacological and psychotherapeutic approaches is promising, but robust, controlled trials are necessary to validate their clinical application.

The work was conceptualized by LV with original draft. MB and ES collected and added references. Writing, review and editing – LV, MB, and ES. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.