1 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29634, USA

2 Université Paris Cité, CNRS UMR 8038 CiTCoM, Inserm, U1268 MCTR Paris, France

Abstract

Most human diseases have genetic components, frequently single nucleotide variants (SNVs), which alter the wild type characteristics of macromolecules and their interactions. A straightforward approach for correcting such SNVs-related alterations is to seek small molecules, potential drugs, that can eliminate disease-causing effects. Certain disorders are caused by altered protein-protein interactions, for example, Snyder-Robinson syndrome, the therapy for which focuses on the development of small molecules that restore the wild type homodimerization of spermine synthase. Other disorders originate from altered protein-nucleic acid interactions, as in the case of cancer; in these cases, the elimination of disease-causing effects requires small molecules that eliminate the effect of mutation and restore wild type p53-DNA affinity. Overall, especially for complex diseases, pathogenic mutations frequently alter macromolecular interactions. This effect can be direct, i.e., the alteration of wild type affinity and specificity, or indirect via alterations in the concentration of the binding partners. Here, we outline progress made in methods and strategies to computationally identify small molecules capable of altering macromolecular interactions in a desired manner, reducing or increasing the binding affinity, and eliminating the disease-causing effect. When applicable, we provide examples of the outlined general strategy. Successful cases are presented at the end of the work.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- macromolecular interactions

- protein-protein binding

- protein-DNA binding

- mutations

- small molecules

- drugs

Macromolecular interactions, i.e., interactions involving proteins, DNA, or RNA, are crucial in various biological processes, serving as the molecular foundation for all essential cellular functions [1, 2, 3]. Among these interactions, receptor-ligand interactions are vital for cell signaling, enabling communication between cells and their environment. Indeed, ligands bind to their corresponding receptors with high specificity, triggering a cascade of cellular responses [4]. Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are another example of macromolecular interactions involving two or more proteins forming a protein complex [5]. Protein complexes orchestrate various cellular activities by forming intricate networks that regulate pathways and processes [6]. It is estimated that a single protein can participate in dozens, possibly hundreds, of different interactions [7]. This has prompted the creation of many databases and tools for analyzing PPIs [8, 9, 10]. A subclass of PPIs involves membrane proteins that reside in cellular membranes and facilitate communications between the internal and external environments of the cell. These proteins mediate processes such as transport and signal transduction and are also frequently involved in interactions with other proteins or ligands [11, 12]. Similarly, proteins interact with DNA and RNA to participate in the transcription and translation of genetic information, ultimately shaping the traits of an organism. Protein-nucleic acid interactions are also involved in the formation of large macromolecular complexes such as ribosomes and histones/nucleosomes [13, 14, 15]. Examples of transient protein-nucleic acid interactions include DNA transcription factors and transport, translation, splicing and, in the case of RNA, silencing [16, 17]. All the processes mentioned above are vital for the wild type function of the cell, and thus, understanding and manipulating these macromolecular interactions holds immense importance for drug discovery. For these reasons, many pharmaceutical developments target specific macromolecular interactions to modulate cellular functions. Here, we briefly mention a few examples of targeting such interactions which are altered by mutations.

Genetic disorders, i.e., diseases originating fully or partially from mutations of an individual’s DNA, are also frequently associated with alterations of wild type macromolecular interactions [18, 19, 20]. In some cases, the mutation affects only one PPI (monogenic disorders), whereas in the case of complex disorders, mutations typically affect numerous PPIs. PPIs and, in particular, homodimerization, i.e., the interaction involving two identical monomers, is frequently seen as a key factor influencing the functionality of various proteins. However, mutations in the homodimer complex can lead to unregulated homodimerization, which in turn leads to pathogenicity. Indeed, in the case of Snyder-Robinson syndrome, it has been shown that most disease-inducing mutations lead to reduced homodimerization and loss of function [21, 22]. A particular example, the mutation F58L, located at the homodimer interface, is shown in Fig. 1A. This mutation was investigated computationally and experimentally, and it was demonstrated that it reduced homodimer affinity while having little effect on the stability of individual monomers [21]. In such cases, one can target mutations computationally to identify the small molecules required to restore the wild type homodimer affinity. In case of complex diseases, one should consider the effect of numerous mutations to understand PPIs at a cellular level and their association with disease [6]. Because of the complexity of interaction networks involving numerous macromolecules, interpreting the effects of genetic variants requires information from different levels, including structural information [23]. Perturbed PPIs may lead to aggregation, which is the main mechanism for many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [24]. Of particular interest are mutations causing cancer since this is a complex disease influenced by many factors. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that cancer mutations frequently affect PPIs and are clustered within interaction hubs [25, 26]. Due to the complexity of cancer causality, researchers have developed so-called “mutational signatures”, i.e., sets of mutations that are associated with high cancer predisposition and provide insights into the causes of specific cancers [27]. One such example includes mutations in the p53 family members, i.e., p53, p63, and p73, which are common in many cancers, including head and neck tumors [28, 29]. The study has shown that the mutations and the association between p53 members lead to cancers and diseases; consequently, p53 family cancers are a potential target for diagnostic and therapeutic approaches [30].

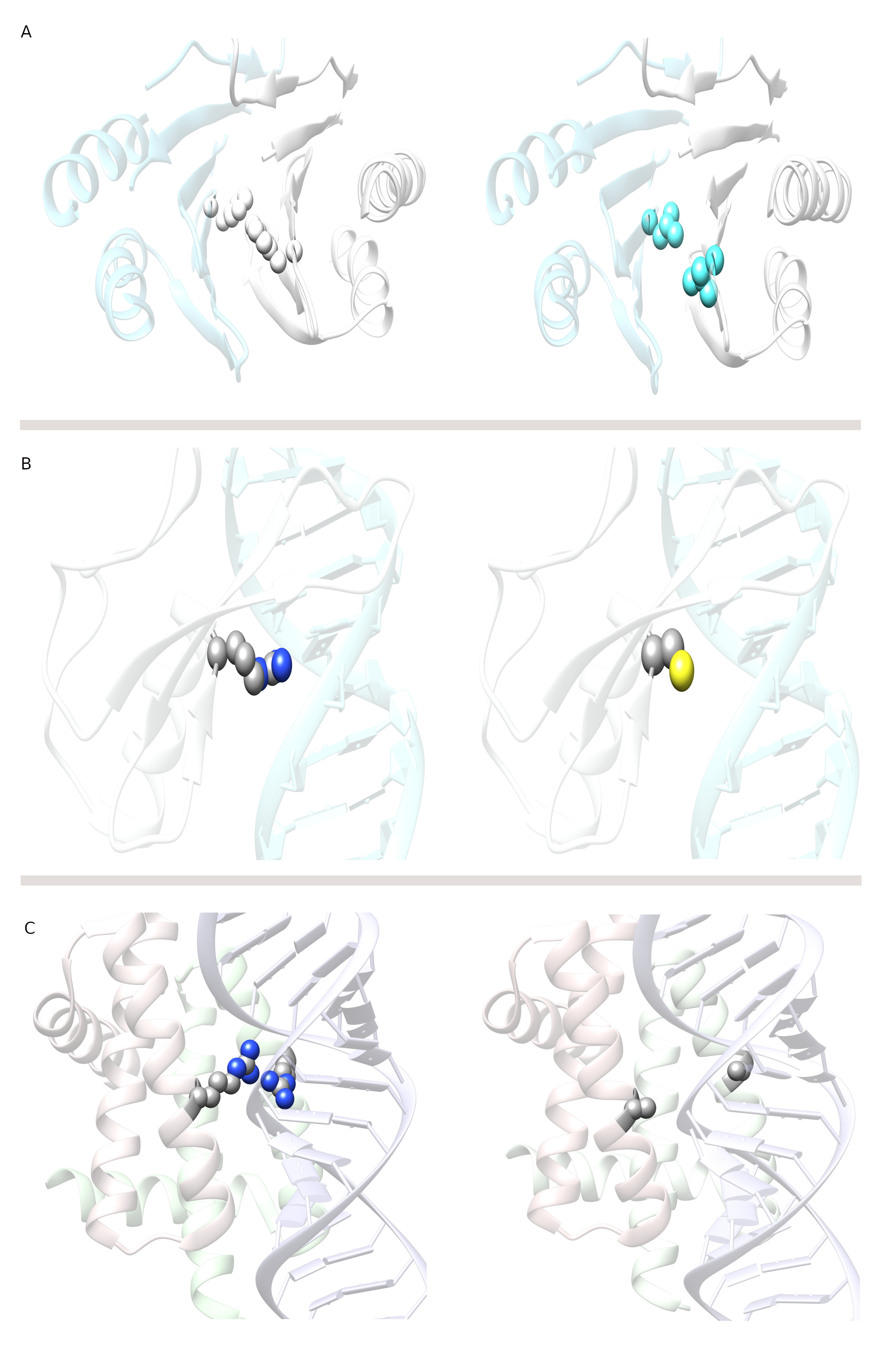

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Mutations at the interface alter wild type macromolecular interactions. (A) Altered protein-protein (spermine synthase homodimer) interaction. The left side shows a wild type spermine synthase, and the right side shows a mutant spermine synthase. The mutation at the homodimer interface is F58L (shown in spherical representation), which has been shown to cause Snyder-Robinson syndrome by altering homodimerization. (B) Altered protein-DNA (MeCp2-DNA) interaction. The left side shows a wild type MeCp2-DNA complex, and the right side shows a mutant MeCp2-DNA. The mutation at the MeCp2-DNA interface is R133C (shown in spherical representation), which has been shown to cause Rett syndrome by altering MeCp2-DNA binding. (C) Altered protein-dsRNA (NS1-RNA) interaction. On the left side, a wild type NS1-dsRNA complex is shown, and on the right, mutant NS1-dsRNA. The mutation at the NS1-dsRNA interface is R38A (shown in spherical representation), which has been shown to alter NS1-dsRNA binding in the virus. Such mutation reveals how the virus can be targeted by searching for small molecules that can mimic the effect of such mutations and inhibit viral immune evasion.

Genetic disorders are also associated with perturbed protein-nucleic acid interactions, and of particular interest are perturbed protein-DNA interactions resulting in an elevated risk of cancer [31]. A prominent example is p52 protein and its corresponding mutations, which lead to different cancers [32, 33]. Another example of a disease caused by altered protein-DNA interactions is Rett syndrome, a neurological disorder caused by mutations in methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCp2) [34]. It has been shown computationally and experimentally that the most frequent mutations causing Rett syndrome reduce MeCp2-DNA affinity while having little effect on MeCp2 stability [35, 36]. Fig. 1B shows a particular example of R133C mutation, which reduces MeCp2-DNA binding affinity with minimal effect on MeCp2 stability [35]. The list of examples of altered protein-DNA interactions leading to diseases is very long, mostly because protein-DNA interactions are involved in transcription, which is a key component of cellular function. Consequently, it is unsurprising that many diseases are associated with transcriptional disorders; however, developing drugs capable of modulating protein-DNA interactions remains challenging [37, 38, 39]. Altered protein-RNA interactions are also among the leading causes of a range of diseases [40]. A particular example is metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transport 1 (MALAT1), a highly abundant nuclear long noncoding RNA that is overexpressed in several human cancers [41]. A single point mutation is assumed to disrupt the triple helix stability of MALTA1, suggesting a pivotal role of this structure in enabling MALAT1 accumulation [42, 43]. Sometimes, altered macromolecular interactions in viruses can be targeted for antiviral drug discovery. For example, influenza A viruses are major human pathogens with the potential to cause periodic pandemics. The NS1 protein of the influenza A virus (NS1A) is responsible for protecting the virus from the host’s immune defenses. The RNA-binding domain (RBD) of NS1A forms a homodimer to recognize double-stranded RNA (dsRNA); however, mutations in this domain may affect the dsRNA binding affinity. One such mutation is R38A, as shown in Fig. 1C, which eliminates the dsRNA binding ability by avoiding the unique Arg38-Arg38 pair that is crucial for dsRNA binding [44]. Hence, such a positive pocket in the RNA-binding domain of the influenza virus can be targeted computationally to identify small molecules capable of binding to this pocket to induce the disruption of the Arg38 pair.

Although our primary focus is on altered macromolecular interactions due to mutation, it is important to note that both overexpression and underexpression of the corresponding protein can sometimes lead to disease. An example of this phenomenon is calpain, a heterocomplex comprising two proteins. Both overexpression and underexpression of calpain have been associated with several neuropathological conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, cerebellar ataxia, and different cancers [45, 46, 47]. Another example involves the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) gene. Amplification of the HER2 gene and overexpression of the HER2 protein has been linked to several types of cancer, including breast, colon, gastric, esophageal, and endometrial [48]. On the other hand, underexpressed proteins, such as PIK3R1, are linked to breast cancer [49]. The underexpression of different tumor suppressors is also a leading cause of many cancers [50, 51]. For example, Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is a critical tumor suppressor, and its inhibition promotes various malignant characteristics of human cancer cells. One such cancerous inhibitor of PP2A is CIP2A, which supports the activity of several critical cancer drivers (Akt, MYC, E2F1) and promotes malignancy in most cancer types via PP2A inhibition [52]. All of the above-mentioned cases involving genetic disorders, cancers, and other diseases indicate that mutation-altered macromolecular interactions have pathogenic effects and indicate the necessity of the development of computational strategies to identify drugs capable of eliminating the effect of mutations on macromolecular interactions. Next, we will outline the computational methods and strategies involved in such a process.

The above-mentioned alterations of macromolecular interactions caused by missense mutations can be targeted by small molecules or peptides to restore wild type interactions. However, it should be clarified that the first step to achieve this requires the identification of a consensus outcome for all mutations affecting particular macromolecular interactions. Returning to the Rett syndrome case, it has been shown that all pathogenic mutations occurring at the protein-DNA interface reduce binding affinity when compared to the wild type protein [35]. Thus, it is necessary to develop a small molecule or peptide that enhances the binding affinity of the mutants to the affinity of the wild type protein. However, identifying such a universal small molecule requires targeting an interfacial patch that does not include any of the mutation sites, thereby making it mutant-independent. Such an approach would result in the development of an enhancer that restores the wild type affinity for all known mutants. On the other side of the spectrum are mutations that either increase the affinity of the mutants or indirectly facilitate the macromolecular interactions of overexpressed partners. To eliminate such effects, one should develop small molecules that reduce either interactions or the overexpression of the partners. Similarly, as above, this should be done in the context of the effects of mutations and the locations of the mutation sites. Below, we briefly outline the details of computational approaches for designing small molecules for use as inhibitors and enhancers.

Recent work has summarized the current state-of-the-art in designing inhibitors without specifically considering that the altered macromolecular interactions are caused by mutations [53]. Small interfaces have been shown to be more effectively inhibited than interactions involving large interfacial areas. It should be mentioned that the inhibition of macromolecular interactions differs from the inhibition of the active site of an enzyme. In the former case, one knows the location of the active site and needs to develop a small molecule capable of binding there with the desired affinity. In the case of inhibiting interactions, especially those altered by mutation, the investigator should first determine the best binding site. Since the binding interfaces of the partners are of similar size, one can target both interfaces and identify small molecules that have a high affinity to binding to both partners, and for which the binding sites are aligned across the interface. Such a scenario will represent an inhibitor that sterically hinders the binding since the presence of the small molecule, especially at the core of the interface, will introduce van der Waals (vdW) overlaps with binding partners. However, such interfaces are typically much larger than the size of small molecules, and macromolecules can reduce the vdW overlaps by adopting conformational changes (this will be discussed later). We illustrate this concept for a particular heterocomplex, calpains, which consist of large and small domains (L-S domains) (Fig. 2).

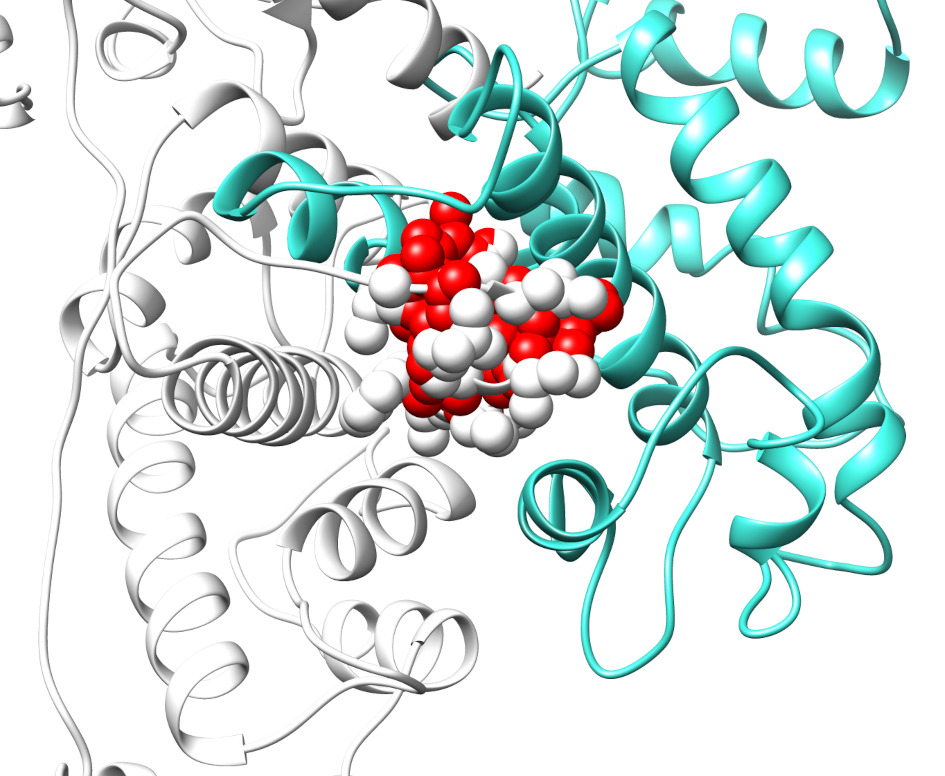

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

van der Waals clashes at the interface of calpain large and small (L-S) domains due to the presence of the small molecule. L and S domains in calpain are represented in white and cyan, respectively. The red-colored spheres represent atoms of the small molecule, which exhibit van der Waals (vdW) overlaps with the atoms (white) in the L domain. The vdW clashes are expected to alter the associations of the S- and L-domains of the calpain.

An alternative scenario for developing inhibitors involves considering small molecules with a high affinity to one of the partners but repulsive interactions toward the other partner. In such a case, the small molecule is expected to bind tightly at the interface of one of the partners while pushing away the other partner, thereby reducing the affinity. The main challenge for this scenario centers on how to determine that a given small molecule has a repulsive interaction with one of the partners. One can explore general biophysical considerations such as charge-charge interactions or hydrophobic versus hydrophilic properties; however, in many cases, this will not provide satisfactory results. Perhaps the most applicable approach will involve protein-DNA/RNA interactions. Since DNA/RNA molecules are highly negatively charged, one would expect that any small molecule with a negative net charge should be repelled by DNA/RNA.

To computationally design macromolecular interaction enhancers, the protocols outlined above can be applied even when the objective is different. To identify a small molecule serving as molecular glue, researchers should seek small molecule candidates that have a strong affinity to both partners and are relatively small. Thus, the binding of the small molecule should have little to no vdW overlaps with any of the partners. The optimal solution may involve a small molecule capable of binding at the periphery of the macromolecular interface. This is an important distinction compared with inhibitors and opens the possibility for small soluble molecules since binding at the periphery does not involve a large desolvation penalty. Here, we will illustrate this concept with a particular case mentioned above, namely Rett syndrome involving altered MeCp2-DNA interactions [35]. Since the mutation sites predominantly affecting MeCp2-DNA binding are located at the protein-DNA interface, the best strategy is to target the interface periphery with small molecules and thus potentially eliminate the effects of all mutations. In silico screening against Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs has resulted in several promising hits, one of which is shown in Fig. 3 (left panel). One can appreciate that the small molecule makes several hydrogen bonds with both MeCp2 and DNA, presumably stabilizing the mutant MeCp2-DNA complex and restoring its wild type binding affinity (Fig. 3, right panel).

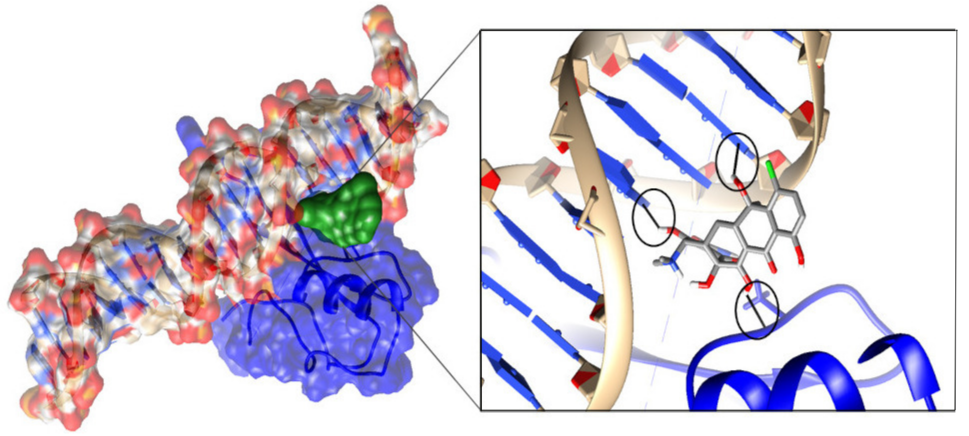

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

MeCp2 (blue) bound to cognate DNA (ball and stick presentation), showing molecular surfaces. The small molecule bound at the periphery is shown in green (left panel). Zoom view of the interactions between the small molecule and MeCp2 and DNA (right panel). Hydrogen bonds are circled in black. The hydrogen bonds formed between the small molecule and MeCp2 and DNA are expected to restore the wild type binding affinity of the MeCp2-DNA complex.

It should be noted that the enhancement or stabilization of PPIs, including

dimers or oligomers, can lead to either activation or inhibition of biological

mechanisms [54, 55]. Targeting areas at or near the interfaces of two or multiple

proteins by small molecules to stabilize their interactions can benefit from a

significantly higher specificity [56, 57, 58]. Enhancing PPIs can be more promising

than inhibiting because, as opposed to the large number of PPIs targeted by

inhibitors, the binding pockets formed by the association of two or several

partners shows a more favorable drug profile [56, 59]. Currently, most of PPI

stabilizers are so-called orthosteric modulators of PPIs, as in the case of Rett

syndrome illustrated above, since they bind close to the PPI interface. Other

examples are ebselen-based molecules that stabilize the superoxide dismutase 1

(SOD1) dimer interface, stabilizers of 14-3-3 PPIs, among others [54, 60, 61].

There are, however, other possibilities to stabilize multimers via allosteric

mechanisms, including the case of taxol allosterically modulating the interdimer

interface of the complex of the

Molecular docking is a common method in computational drug design, especially when the 3D structure of the protein target is known. Its main purpose is to understand and predict how small molecules will recognize and bind to a target, both in terms of structure (finding possible binding modes) and energy (predicting binding strength). This process involves two main steps: predicting how a small molecule (ligand) fits and orients itself within the protein’s binding site and evaluating the quality of this fit using a scoring function. Ideally, the method should replicate the experimental binding mode and rank it highest among all possible fits. Additionally, it aims to score active molecules higher than inactive ones.

While docking is often used as a stand-alone method in drug design, it is increasingly combined with other computational methods, including artificial intelligence (AI), to obtain better results [66, 67]. Since the 2000s, machine learning (ML) approaches based on nonlinear modeling algorithms, such as k-nearest neighbors, support vector machines (SVM), random forest (RF), and artificial neural network (ANN), have been frequently used for drug discovery [68]. Several studies have combined docking and ML to identify new hit molecules [69, 70, 71, 72]. For example, a recent study exploited ML for virtual screening of an ensemble of protein conformations (EnOpt method) to effectively rank and prioritize the best candidates [73]. During the last decade, advanced AI approaches, such as deep learning (DL), have enabled the implementation of more innovative and efficient modeling methods using large and heterogeneous datasets of small molecules and drugs [74, 75]. DL utilizes an ANN with more than two hidden layers that can characterize structures in higher-dimensional data representations. In deep neural network (DNN), each neuron receives input signals from its connected neurons, which are then multiplied by their respective weights and summed up. A recent example of this approach is a new protocol combining generative molecular AI and physics-based absolute binding free energy molecular dynamics simulations, which have been proposed as a means for discovering new ligands for different target proteins [76]. Several studies have reported the use of docking for inhibitor discovery [77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83]. For example, two proteasome inhibitors, carfilzomib, and bortezomib, a boronic acid-based small molecule, were successfully identified using structure-based virtual screening and used to treat refractory multiple myeloma [77]. Similarly, a highly promising novel drug-like inhibitor of lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (LCK) was recently identified using integrated DL and docking methodologies [78]. Another example involves the use of molecular docking and ML-based virtual screening to find the inhibitors for Tankyrase enzymes (TNKS) [79]. Similarly, molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were used to study the theoretical interaction mechanism between Janus kinase 3 (JAK3) kinase and its inhibitors [80]. Another investigation reported a series of reversible non-covalent Monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) inhibitors identified via virtual screening [81]. Similarly, a flexible-receptor docking protocol was used to identify the possible inhibitors for Pim-1 Kinase [82]. The progress made to identify new small molecules targeting acetylcholinesterase in Alzheimer’s disease is reviewed here [83]. Most of the above-mentioned studies were carried out using tools for in silico docking; the most frequently used are listed in Table 1 (Ref. [84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98]).

| Docking tools | Scoring function | Search algorithm | Type | URLa | Reference |

| AutoDock Vina | Force-Field Based | MC/BGFS (Monte Carlo/Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno algorithm) | Academic | https://github.com/ccsb-scripps/AutoDock-Vina | [84, 85] |

| AutoDock4 | Force-Field Based | Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm | Academic | https://github.com/ccsb-scripps/AutoDock4 | [86] |

| Dock | Force-Field Based | Matching Algorithm | Academic | https://dock.compbio.ucsf.edu/ | [87] |

| GLIDE | Empirical | Hybrid (Exhaustive Sampling Method) | Commercial | https://www.schrodinger.com/platform/products/glide/ | [88] |

| FlexX | Empirical | Fragmentation Sampling Method | Commercial | https://biosolveit.de/download/?product=flexx | [89] |

| GOLD | Empirical | Genetic Algorithm | Commercial | https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/solutions/software/gold/ | [90] |

| SwissDock | Force-Field Based | Evolutionary Optimization | Academic | https://www.swissdock.ch/ | [91] |

| rDock | Empirical | Hybrid (Genetic Algorithm optimization followed by Monte Carlo and Simplex Minimization) | Academic | https://rdock.github.io/ | [92] |

| PLANTS | Empirical | ACO (Ant Colony Optimization Method) | Academic | Currently Not Accessible | [93] |

| MedusaDock | Force-Field Based | GPU Based Parallel Genetic Search Algorithm | Academic | https://bitbucket.org/dokhlab/medusadock-web/src/master/ | [94] |

| HADDOCK | Empirical | Hybrid (Chemical Shift Perturbation and NMR results) | Academic | https://www.bonvinlab.org/software/#haddock | [95] |

| Surflex | Empirical | Shape Matching | Commercial | https://www.biopharmics.com | [96] |

| ROSETTALIGAND | Force-Field Based | Monte Carlo Minimization | Academic | https://meilerlab.org/rosetta-ligand/ | [97] |

| Gnina | Convolutional Neural Networks | MC/BGFS (Monte Carlo/Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno algorithm) | Academic | https://github.com/gnina/gnina | [98] |

a Source code URL if available or download link/webserver from its developers.

The interaction energy of docking software is largely evaluated by scoring functions, which present major challenges in the docking-scoring methodology [99, 100, 101, 102]. Scoring functions are trained and benchmarked in most cases involving proteins and small molecules, where the binding site is a priori known, and the binding site is typically quite druggable. Furthermore, their applicability for in silico screening involving DNA or RNA molecules is questionable despite recent developments in tools to study RNA-protein complexes and multiple ligand docking methods [103, 104]. Leclerc and Cedergren were among the first to model RNA ligands using a 3D-SAR-based approach coupled with molecular dynamics (MD) calculations to optimize small molecule poses [104, 105]. The site identification by ligand competitive saturation (SILCS) computational approach was recently extended to target RNA, termed SILCS-RNA, and was applied to seven RNA systems for which small molecule-RNA interaction data were available [104]. The issues with the scoring function and other points deserving attention will be discussed in the “challenges” section below.

Modulating macromolecular interactions with small molecules is difficult. Challenges facing such approaches include limitations inherent to docking tools and scoring functions, available experimental data, the typical flatness of the interface, and large interfacial areas.

Molecular docking is a valuable tool for structure-based drug discovery. One of the most critical components of a docking application is the scoring function. Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) relies on traditional scoring functions, which often fail to distinguish between binders and non-binders. Therefore, an effective scoring function must be both rapid and accurate when scoring and ranking the numerous docking poses generated during simulations. It should efficiently screen small molecule libraries, select the correct binding poses, and identify active molecules. A good scoring function should also ensure strong binding between a small molecule and its native receptor while exhibiting weak binding to off-target proteins. However, the scoring functions used in most docking tools are based on force fields, statistics, or empirical methods and are mainly trained on datasets obtained on high-quality protein-ligand (small molecule) complex structures. These complex structures have been determined experimentally, and the datasets do not include docking poses. Consequently, when ranking docking poses, traditional scoring functions often select false positives (poses that are far from the native pose) because they are unable to distinguish them from true native poses. Traditional scoring functions also typically rely on overly simplified linear energy combinations; as such, they cannot effectively learn from unusual cases or large-scale decoy datasets. In some cases, ML classifications can reduce false positives [101]. Therefore, to overcome the limitations of current docking-scoring approaches, the integration of AI, such as ML and DL, can be highly valuable in improving the success rate of scoring when targeting macromolecular interactions, in particular PPIs [67, 74, 102, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111]. Due to the particular physicochemical properties of small-molecule inhibitors of PPIs discussed above, focused scoring functions for targeting PPIs have been developed using ML techniques [112]. The integration of ligand entropy and solvation considerations in empirical ML-based scoring functions has been shown to improve the performance of the scoring functions for the screening of PPIs [113]. Similarly, classical scoring functions for docking are also unable to exploit large volumes of structural and interaction data [99]. These traditional docking tools face challenges when designing covalent small molecules because the formation, breaking, and rearrangements of covalent bonds involve quantum mechanical (QM) phenomena. These processes typically cannot be accurately represented by the force fields or empirical approaches used for non-covalent protein-ligand interactions [114]. Although QM contributions are increasingly integrated into docking applications, fully implementing QM methods remains impractical for routine use due to the computational demands imposed by the size and complexity of molecular systems and the vast number of configurations of molecules involved [114]. However, faster and simpler modeling approaches are available that can often address the need for QM calculations in covalent docking. In many cases, a full QM treatment of the docking process may not be necessary, offering practical alternatives for designing covalent small molecules.

Another challenge in docking is sampling the conformational space. Docking aims to identify the best binding pose between a protein and a small molecule and is more accurate if both are flexible. Typically, identifying a small molecule involves screening across millions of molecules and carrying out flexible protein and flexible small molecule docking. This requires an extensive conformational search, making the process computationally intensive. In such cases, one aims to carry out rigid protein and flexible small molecule docking, which only requires a conformational search for the small molecule, not the receptor, and making it computationally more efficient than the previous approach. However, this approach also has limitations; for example, it does not account for the flexibility of the protein, which is crucial for accurate protein-small molecule interactions. The optimal binding conformation of a small molecule depends on both its internal structure and its interactions with the binding site of the protein.

In traditional protein targeting, the objective is to bind potential small molecules to locations in macromolecules capable of modifying their activity. A protein typically has a key binding site for a specific substrate but may also have other allosteric sites. Identifying these sites is essential and is usually performed experimentally to obtain the structure of the protein-small molecule complex. If known binding small molecules exist, they can serve as a reference for defining the docking cavity. However, defining the cavity poses a challenge: if it only includes residues close to a known binder, the software’s performance may be overestimated when redocking the known binder. Conversely, a very large cavity increases the search space for the algorithm. On the other hand, when the bound small molecule is absent from the crystal structure, the identification of the active site in proteins becomes critical. One approach to mitigate this challenge is blind docking, which involves defining a single site or a docking box around the receptor protein. The docking program then explores all sites within the docking box to identify the best site for the small molecule. However, blind docking predicts the bound conformations with no a priori knowledge; as such, it requires extensive conformational searches and is computationally challenging, as outlined above. Additionally, defining a large docking box can lead to errors in the scoring function calculation. This occurs because the docking box is represented as a grid, with the scoring function calculated at each grid point. For larger proteins, a larger docking box is needed, which in turn may require larger spacing between the grid points. This increased spacing results in less accurate docking scores. A large docking box may introduce more potential binding sites, many of which may not be relevant. This increases the chance of identifying false positives where the predicted binding poses are not biologically meaningful. To overcome these limitations, one can define several patches around the protein structure instead of a single large docking box. This involves setting up multiple smaller docking boxes around the target protein and merging the results obtained from these patches to identify the optimal binding pose.

However, applying the same approach to modulate macromolecular interactions in which wild type characteristics are altered by mutations is even more complicated. The additional challenges derive from the lack of prior knowledge of the location of the binding site; indeed, very few experientially determined structures exist for macromolecular complexes with a small molecule at or near the binding interface. Furthermore, identifying a putative binding site located away from all known missense mutations is challenging because it implies additional restriction of plausible good binding pockets. In addition, if one seeks to design binding enhancers, binding site(s) should be identified for both partners and should be geometrically complementary.

Docking relies on the availability of the 3D structure of the target protein and macromolecular complex, but not all proteins have had their structures experimentally determined, including the 3D structures of their mutants. In such cases, the first step in drug development should be modeling the 3D structures of unbound and bound partners. Progress made in 3D structure prediction, for example using AlphaFold 1, 2, and 3, makes this step straightforward [115, 116]. However, it is quite unlikely that modeling tools will be able to correctly capture the effects of a single mutation on the 3D structure of both unbound and bound partners.

Structural water molecules bound to proteins are commonly observed in crystallographic structures, posing a challenge for drug discovery. In approximately 65% of protein-small molecule complexes resolved using crystallography, at least one water molecule plays a role in protein-small molecule recognition [117]. These labile water molecules can stabilize the complex through hydrogen bonding between the small molecule and the protein, or may be displaced due to small molecule binding. They contribute significantly to the entropic and enthalpic changes of the binding, where the loss of entropy from transferring water molecules from the bulk solvent to the binding site is balanced by the enthalpic contribution of additional hydrogen bonds. Available docking software may or may not be able to account for these active water molecules. Several studies have shown that the inclusion of active water molecules in docking simulations can improve the accuracy of determination of small molecule docking poses while enhancing small molecule enrichment. However, during virtual screening, they are typically neglected due to the computational costs associated with modeling these water molecules [118, 119].

Available experimental data for small molecules bound to macromolecular complexes serve two roles: (a) as a benchmarking set to assess the performance of empirical and first principle docking methods; and (b) as a training set for ML and adjustable empirical methods. In this regard, significant challenges remain to further improve the prediction of drug candidates, in particular, data availability for macromolecular interactions [68]. For many targets, the available experimental data lack either quantity or quality. One may expect a rapid increase in high-quality data because of initiatives such as the Library of Integrated Network-Based Cellular Signatures (LINCS) developed by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). Innovative high-throughput (HTP) experimental technologies, such as the CRISPR knockout method, which tracks genetic modifications due to protein-small molecule interactions, and the cost-effective HTP reduced-representation expression profiling method, L1000, can efficiently provide large quantities of new data [120]. A unique chemical library dedicated to the inhibition of PPIs has also been created and is accessible for in silicoand experimental screening [121]. Several databases have been developed containing information for small-molecule modulators of PPIs. The Timbal database automatically extracts relevant data from ChEMBL following the identification of PPI targets [122]. 2P2Idb is a hand-curated structural database dedicated to PPIs with known small-molecule orthosteric modulators containing more than 270 protein-inhibitor complexes corresponding to 242 unique small-molecule inhibitors derived from the Protein Data Bank [123]. Pharmacological data available in the iPPI-DB database have been retrieved from more than 2000 peer-reviewed publications and patents [124].

In the best-case scenario, computational findings should be validated experimentally. This includes validation that the small molecule binds to the target, binds at the predicted position, and adopts the predicted pose. While this can be done experimentally for a limited number of small molecule candidates, it is not feasible to perform such operations for hundreds or thousands of candidates, especially regarding binding position and pose. Carrying out thousands of X-ray or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments for a particular target is not expected to be of high priority for any experimental lab. This is a crucial limitation for optimizing drug candidates because one can further optimize small molecules based on their experimentally determined binding mode. Other experimental validations, such as the effect of small molecules on macromolecular binding, can be done on a large scale; however, this process does not reveal the cause of the observed effect.

Traditional strategies for small-molecule drug discovery focus mostly on targeting enzymes, ion channels, and/or receptors (G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) or nuclear receptors) due to the fact that their deep binding sites easily accommodate small molecules [125]. Similarly, one can target defective PPIs with small molecules, particularly using orally bioavailable molecules (the most convenient and safest for patients) [126]. Targeting modulation of PPIs using small molecules was challenging for a very long time due to their relatively flat and large surfaces [127]. Although PPIs are diverse in terms of binding affinity and duration (i.e., permanent or transient interaction), and their interface areas (1500–3000 Å2) are much larger than those of the protein-small molecule contact area (300–1000 Å2), they are flexible and contain aromatic residues [128, 129, 130]. The large surface area of macromolecules is usually buried on each side of the interface, and small molecules do not cover the entire protein-binding surface; thus, a subset of the interface that contributes to high-affinity binding may still be active (contributing to the binding and not influenced by the presence of the small molecule) [131, 132, 133, 134].

Most recently reported success stories have involved the development of small molecules capable of modulating the macromolecular interactions of wild type proteins via HTP experimental screening [55, 58, 135, 136]. Much less progress was made in modulating mutant macromolecular interactions [137]. One of the reasons for this is that at the current state of drug development, researchers are unwilling to invest the required time and resources to develop a drug for a particular mutation causing genetic disorders unless the mutation has a very high frequency (i.e., it is seen in many patients).

As discussed above, computational approaches are very useful for the prediction of small-molecule drug candidates targeting macromolecular interactions. Although the development of small molecules capable of disrupting PPIs is generally considered outside the remit of mainstream drug discovery, recent developments have achieved this. Below, we outline several successes in identifying small molecules via computational approaches that modulate macromolecular interactions. In the examples presented, the disease can be due to mutations present in pathways related to the target of interest and not necessarily on the targeted protein. Virtual screening of large databases occasionally identifies small molecules that inhibit and even recruit protein-protein complexes. For example, small molecules that affect the equilibrium between tubulin and microtubules are effective anticancer drugs [138]. By performing molecular docking-based virtual screening combined with an in vitro tubulin polymerization inhibition assay, two novel and potent tubulin inhibitors targeting the colchicine binding site in tubulin were identified [139]. These molecules displayed potent antiproliferative activity with IC50 values in the nM range. In another study, molecular dynamic simulations combined with binding free energy calculations were performed on seven tubulin models to understand the mechanism of action of three natural drugs: plinabulin, docetaxel, and vinblastine [140]. The results obtained indicated that the drugs disrupted microtubule polymerization by altering its conformation and the binding free energy of the neighboring tubulin subunits. Another important anticancer target is neuropilin-1 (NRP-1), among the most important co-receptors of vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A); the binding of VEGF-A to NRP-1 plays a critical role in angiogenesis and tumor progression. Promising small drug-like molecules disrupting the binding of VEGF-A to NRP-1 were found by performing structure-based virtual screening on the VEGF-A binding pocket of NRP-1 [141]. Four molecules with a common chlorobenzyloxy alkyloxy halogenobenzyl amine scaffold inhibited the binding of biotinylated VEGF-A to recombinant NRP-1 with a Ki of approximately 10 µM, which can serve as a base for the further development of new NRP-1 inhibitors [141]. Similarly, to target the programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) pathway in anticancer immunotherapy, small-molecule inhibitors capable of blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 axis have been identified using molecular docking methods and screening the ChEMBL. The small molecule used was a bifunctional inhibitor of PD-1/PD-L1, which inhibited the PD-1/PD-L1 interactions and promoted the dimerization, internalization, and degradation of PD-L1 [142].

In addition to cancer, successful examples of small molecules inhibiting macromolecular interactions have been reported for other diseases identified by in silico approaches. Structure-based virtual screening was employed to discover a potent inhibitor of the Grb14-Insulin receptor interactions that can play a role in the treatment of Diabetes mellitus type 2 [143]. Successful in silico screening strategies were also employed for the stabilization of native PPIs via small molecules with a molecular glue mode of action. A list of some successful glues has been reviewed [144]. Recently, small-molecule stabilizers of the complex formed by carbohydrate-response element-binding protein (ChREBP regulating transcription of glucose-responsive genes) and 14-3-3 protein were identified via virtual screening that engaged a composite interface pocket formed by both protein partners. Structure-based optimization and X-ray crystallography revealed a distinct difference in the binding modes of weak, general, and specific potent stabilizers of the ChREBP/14-3-3 complex. A structure-guided stabilizer optimization was performed on selected stabilizers, which resulted in up to 26-fold enhancement of the 14-3-3/ChREBP interaction [145]. This study demonstrated the potential of rational design for the development of selective PPI stabilizers starting from weak PPI inhibitors.

To the best of our knowledge, relatively few computational investigations have focused directly on the mutant protein. For example, a study was carried out to restore the enzymatic activity of the malfunctioning spermine synthase (SMS) mutant G56S. The purpose of this study was to stabilize the dimer by binding a small molecule at the mutant homo-dimer interface. Computational and experimental analyses was carried out, leading to the identification of five stabilizers with distinctive chemical scaffolds. These chemical scaffolds are drug-like and can serve as starting points for the development of lead molecules to further address the disease-causing effects linked to Snyder-Robinson syndrome [146].

Toxic gain-of-function (not loss-of-function) of SOD1 mutants causes motor neuron degeneration. PPI inhibitors of mutant SOD1 can be used as novel therapeutics for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Docking-based virtual screening of approximately 32,000 small molecules was performed on the N-terminal binding site of SOD1 interacting with tubulin combined with an assay system for interaction inhibition between mutant SOD1 and tubulin to identify mutant SOD1 PPI inhibitors [147]. Consequently, five of the six assay-executable small molecules among the top-ranked small molecules during docking simulations were found to inhibit the mutant SOD1-tubulin interaction in vitro. Binding mode analysis predicted that certain of these inhibitors might bind the tubulin binding site of G85R SOD1.

For anticancer candidates, a combined ML and docking-based screening was employed to identify small molecules inhibiting the PPI site of the chaperone DNAJA1 and mutant p53. The hit small molecules (GY1-22) were validated in vitro and in vivo, which may lead to an effective treatment for preventing carcinogenesis [148]. Likewise, increased activity of lysine methyltransferase NSD2 carrying activating mutations is associated with multiple myeloma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The first antagonists that block the PPI between the N-terminal proline-tryptophan-tryptophan-proline domain (PWWP) domain of nuclear receptor-binding SET domain-containing 2 (NSD2) and the H3K36me2 histone and abrogate H3K36me2 binding to the PWWP1 domain in cells were identified by virtual screening and experimental validation (showing a Kd of 3.4 µM) [149].

It is important to note that altering the binding of mutant macromolecules with small molecules will have a therapeutic effect only if this alteration results in the restoration of the wild type function. Many macromolecular complexes are formed to activate the corresponding reaction by inducing conformational change. For example, calpain protease requires catalytic and regulatory subunits to bind first then, on calcium binding, conformational changes are induced, which reorient the catalytic triad residues into an active state [150, 151]. Similarly, protein kinase-like CaMKII on phosphorylation induces conformational changes in the phosphorylated protein that alter its activity or ability to interact with other molecules [152]. Likewise, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a dimeric membrane protein that is activated by changes in the conformation of the transmembrane (TM) domain caused by changes in the interactions of the TM helices of the membrane lipid bilayer [153]. Similarly, the p53-DNA complex, which undergoes conformation changes on mutations, is associated with different forms of human cancer [154]. Thus, if one intends to enhance mutant activity, the small molecule should induce conformational change similarly to that induced by the wild type and should not necessarily influence the binding. Similarly, if one wants to reduce the functionality of the mutant, the small molecule should not allow for wild type conformation to occur. Thus, the overall therapeutic effect does not necessarily involve complete restoration of the wild type binding affinity. This is one of the main ideas developed in this review, i.e., drug efficacy is evaluated by the ability of the drug to restore functionality associated with the corresponding macromolecular interaction(s), not necessarily by restoring the wild type binding.

We have not discussed mutations that influence the pH and salt dependence of

binding despite that this factor is very important for many diseases, especially

cancer, since cancer tissue has a different pH from normal tissue. The available

data to address this issue is very scarce, and little work has been done in this

direction. We simply outline several prominent contributions in this field,

mostly from Barber’s lab. Typically, cancer cells have a higher pH than normal

cells; this was identified by Barber and coworkers to enable metastatic

progression [155, 156]. They analyzed 29 cancers and identified six amino acid

mutation signatures, including four signatures that were dominated by either

arginine to histidine (Arg

Overall, altered macromolecular interactions are frequently found to be the major component causing pathogenicity. Therefore, it is crucial to further enhance our ability to modulate defective interactions with small molecules and potential drugs. This holds more promise than using small molecules to stabilize individual mutation-destabilized macromolecules because once the macromolecules are unstable, they are quickly degraded by proteases, and small molecules may not be able to prevent the degradation process. Furthermore, as mentioned above, in many cases, the therapeutic effect may be achievable without complete restoration of the wild type affinity, which relaxes the objectives of in silico drug discovery.

It should also be mentioned that the review does exclude an important component of drug discovery, namely the validation of the suggested small molecules that modulate macromolecular interactions. Depending on the computational resources available, researchers typically select the top N small molecules (N in the range of hundreds or more) and subject these small molecules and their corresponding macromolecular complexes to further analysis. Typical analyses include energy calculations with either molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann (Generalized Born) surface area (MMPB(GB)SA) or quantum mechanics (QM) methods to estimate the effect of small molecules on the binding free energy. Furthermore, one typically applies molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate whether the small molecule remains bound at the predicted position, either at the binding interface or at its periphery, and thus to verify the effects of the small molecule on the binding.

This review outlined the importance of modulating macromolecular interactions with small molecules as promising therapeutic solutions for genetic disorders caused by altered macromolecular interactions. This is particularly promising for complex diseases where mutations affect the macromolecular interactions but not completely abolishing them, thus the small molecules effect could be modest while still capable of restoring wild type binding. At the same time, it is pointed out that the modulation of macromolecular interactions with small molecules is a challenge because of the plasticity of macromolecular interfaces and the large interfacial area, however, in some cases this could be beneficial allowing small molecules to be accommodated deeply into the interface and to serve as enhancers. Having in mind that disease-causing mutations in some cases reduce binding affinity or result in under-expression of the partners, while in other cases may increase the binding affinity or cause overexpression of the partners, it is equally important to design small molecules that serve as inhibitors or enhancers. The success stories presented in the manuscript indicate that despite the challenges, this is an accomplishable goal.

PP carried out the investigation, collected data, and wrote the paper; MM and EA carried out the investigation, wrote the paper, and supervised the research. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Clemson Palmetto Cluster is acknowledged.

The work of P.P. and E.A. was supported by a grant from NIH, grant number R35GM151964.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.