1 Institute of Personalized Oncology, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, 119991 Moscow, Russia

2 Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, 141701 Dolgoprudny, Moscow, Russia

3 Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, 117997 Moscow, Russia

4 PathoBiology Group, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), 1200 Brussels, Belgium

Abstract

RNA editing is a crucial post-transcriptional modification that alters the transcriptome and proteome and affects many cellular processes, including splicing, microRNA specificity, stability of RNA molecules, and protein structure. Enzymes from the adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) and apolipoprotein B mRNA editing catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC) protein families mediate RNA editing and can alter a variety of non-coding and coding RNAs, including all regions of mRNA molecules, leading to tumor development and progression. This review provides novel insights into the potential use of RNA editing parameters, such as editing levels, expression of ADAR and APOBEC genes, and specifically edited genes, as biomarkers for cancer progression, distinguishing it from previous studies that focused on isolated aspects of RNA editing mechanisms. The methodological section offers clues to accelerate high-throughput analysis of RNA or DNA sequencing data for the identification of RNA editing events.

Keywords

- RNA editing

- ADAR

- APOBEC

- RNA sequencing

- NGS

- cancer progression

- transposable elements

- Alu editing index

- epigenetics

- epitranscriptomics

In recent years, RNA modifications have emerged as fundamental regulators of gene expression and cellular function, significantly expanding our understanding of the post-transcriptional landscape in molecular biology. These modifications, now recognized as key players in the field of epigenetics, are associated with diverse biological functions, ranging from the transcription and translation regulation, development of organ and tissue systems to immune defense [1]. RNA epigenetics, also known as epitranscriptomics, encompasses a range of RNA modifications that can be categorized into four groups: uridine isomerization to pseudouridine, base modifications (such as methylation and deamination), ribose methylation at the 2′-hydroxyl group, and more complex types of modifications [2, 3]. Currently, over 150 types of natural biochemical RNA modifications have been identified and catalogued across all types of RNAs [4], and this number continues to grow. Among these modifications, RNA nucleoside substitutions, also known as RNA editing, have garnered increasing attention in recent years, despite being discovered over 30 years ago [5].

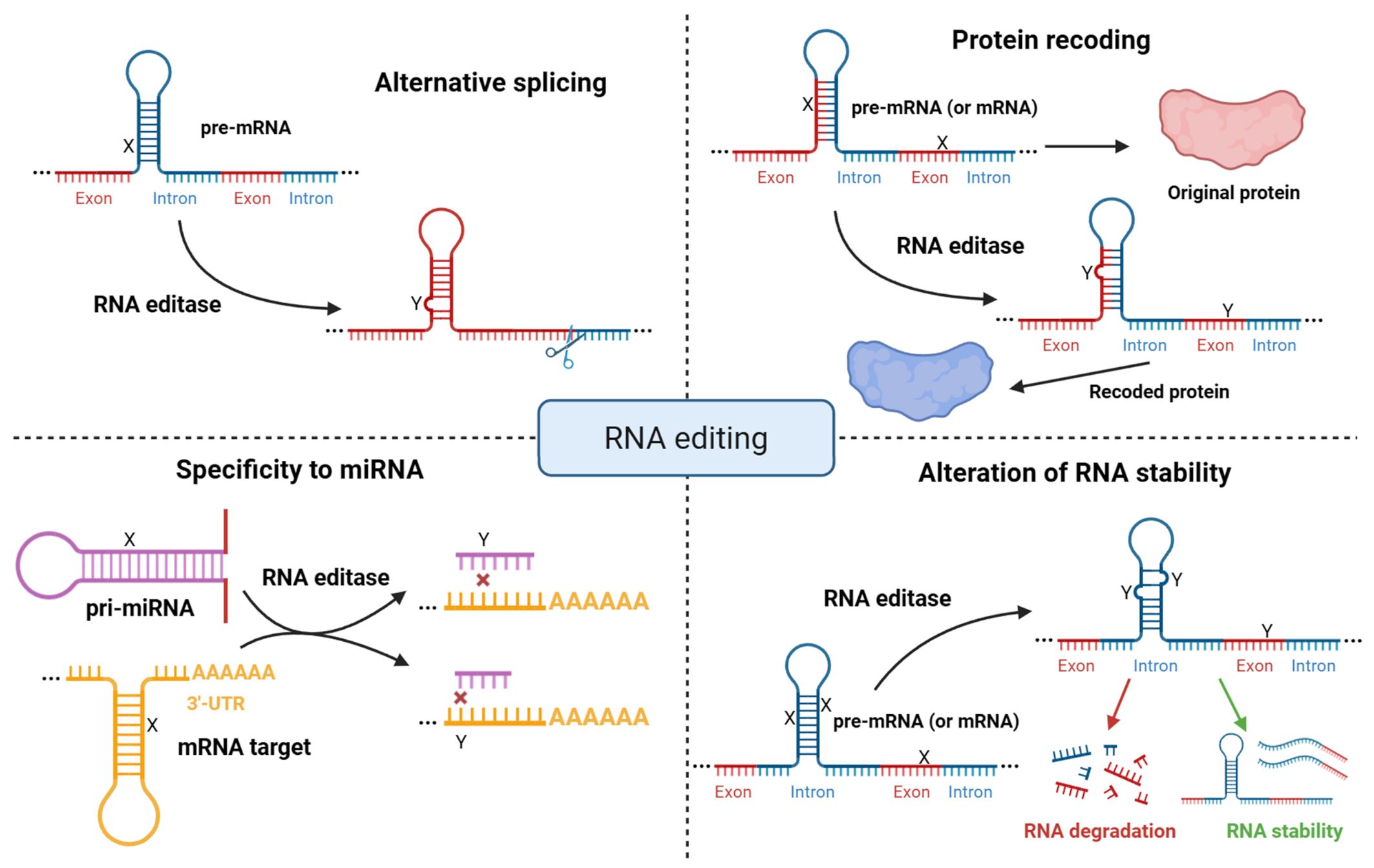

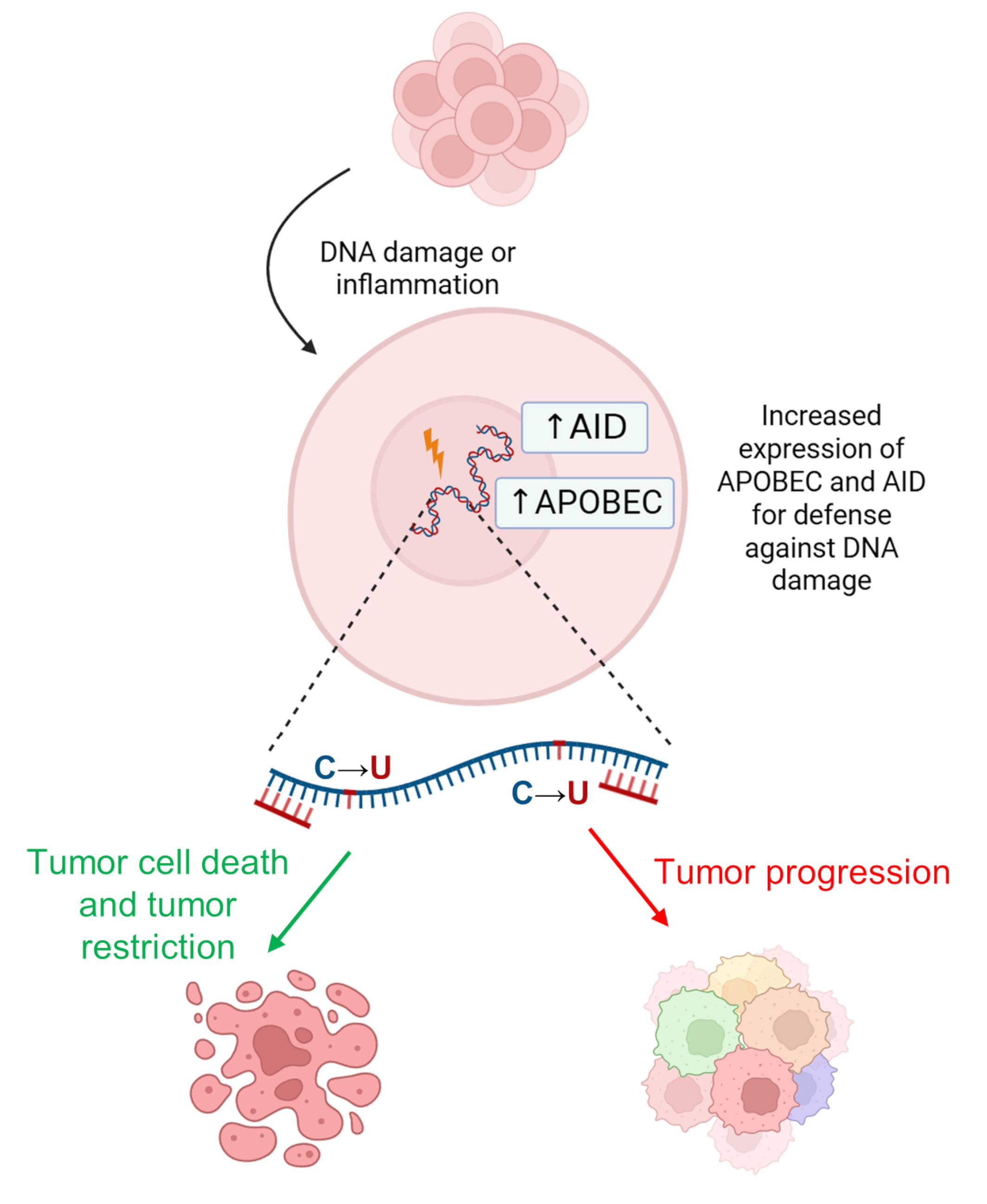

RNA editing is one of the most common forms of post-transcriptional modification of RNA. It alters the amino acid sequence of proteins and also influences pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA stability, and microRNA binding through microRNA or 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR) editing (Fig. 1) [6, 7, 8]. RNA editing occurs in both coding and non-coding sequences, including various types of transposable elements [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Additionally, 3′-UTR editing has been shown to regulate alternative polyadenylation by modifying protein-RNA and RNA-RNA interactions [15].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Molecular functions of RNA editing. Overview of the major impacts of RNA editing, including alterations in the coding regions of mRNA, regulation of alternative splicing, alteration of microRNA binding specificity, and changes in RNA stability. X symbols represent nucleotides before RNA editing, Y symbols represent nucleotides after RNA editing. Created with BioRender.com.

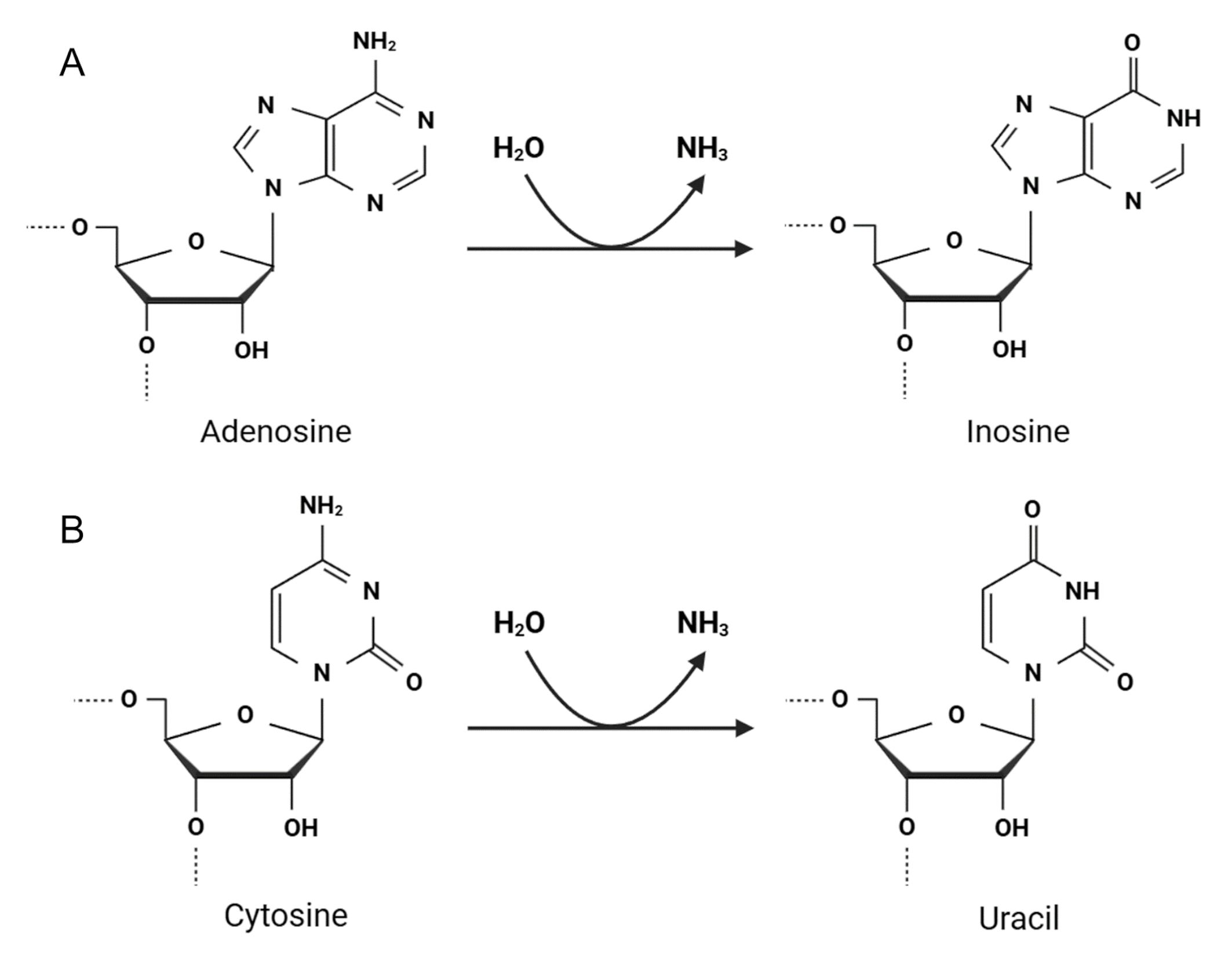

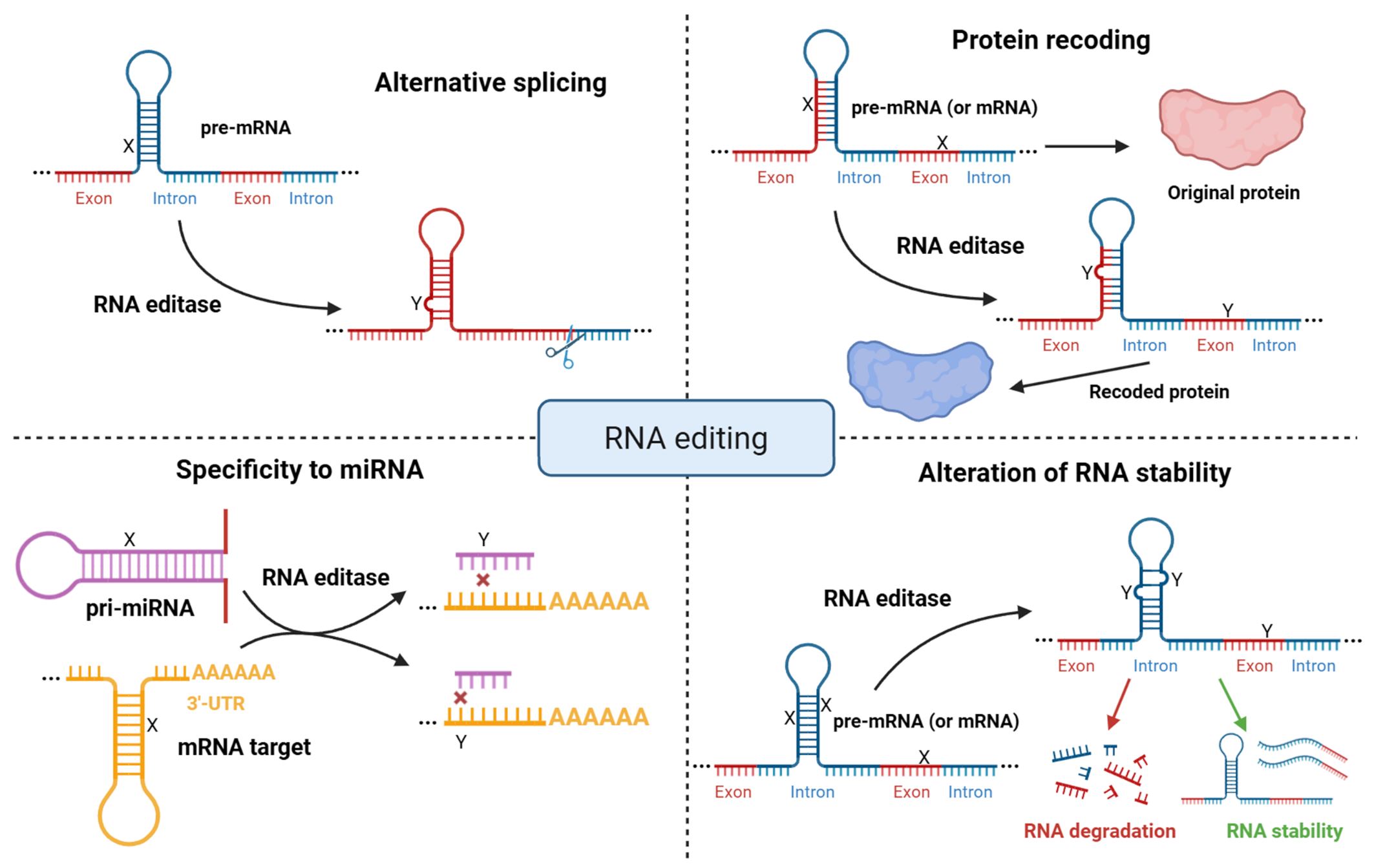

Unlike RNA modifications, such as adenosine and cytosine methylation and uridine pseudouridylation, adenosine and cytosine hydrolytic deamination are directly attributed to RNA editing events in mammals and can be categorized as follows [2, 6, 14, 16]:

-adenosine deaminated to inosine (Fig. 2A), which is recognized as guanosine (A-to-I(G) editing), by adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs) [17, 18], and

-cytosine deaminated to uracil (C-to-U editing) by the apolipoprotein B mRNA editing catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC) protein family (Fig. 2B) [19, 20]. Fig. 2 illustrates how ADAR and APOBEC enzymes catalyze key RNA editing reactions, essential for post-transcriptional regulation. This highlights the molecular precision required for proper RNA function and how errors in these processes can lead to pathological conditions. In healthy cells, ADAR and APOBEC proteins are located in the nucleus and/or cytoplasm, where they modify diverse RNA molecules [10, 21]. However, RNA editing is often associated with various diseases, including cancers.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Two major types of adenosine and cytosine editing by RNA editing enzymes. (A) ADAR proteins catalyze adenosine deamination at C6, resulting in inosine formation (A-to-I reaction). (B) APOBEC proteins mediate C-to-U conversion at C4. ADAR, adenosine deaminase acting on RNA; APOBEC, apolipoprotein B mRNA editing catalytic polypeptide-like. Created with BioRender.com.

ADAR-mediated conversion of adenosine to inosine is the most common RNA editing form from mammals [6, 7, 8, 10]. A-to-I editing occurs in hairpin double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) within mRNA or non-coding RNAs. The dsRNA hairpins in pre-mRNAs that undergo ADAR editing are incompletely paired RNA duplexes, often formed by matching exonic sequences with nearby intronic and regulatory regions, such as UTRs. These structures are recognized by ADAR enzymes via their RNA binding domains [2, 7, 10]. The resulting introns and dsRNA hairpins are then removed through splicing [8]. Since the genetic machinery of the cell recognizes inosine as guanosine, A-to-I editing can lead to nonsynonymous codon changes within transcripts or the generation of new splice sites. Most edited RNA hairpins are situated outside the coding sequence and remain in the mature mRNA as part of the 3′-UTR to regulate the translation of coding regions and an overall mRNA turnover [22]. In addition, ADAR enzymes affect the targeting and maturation of non-coding RNAs: microRNAs and circular RNAs [11, 23, 24].

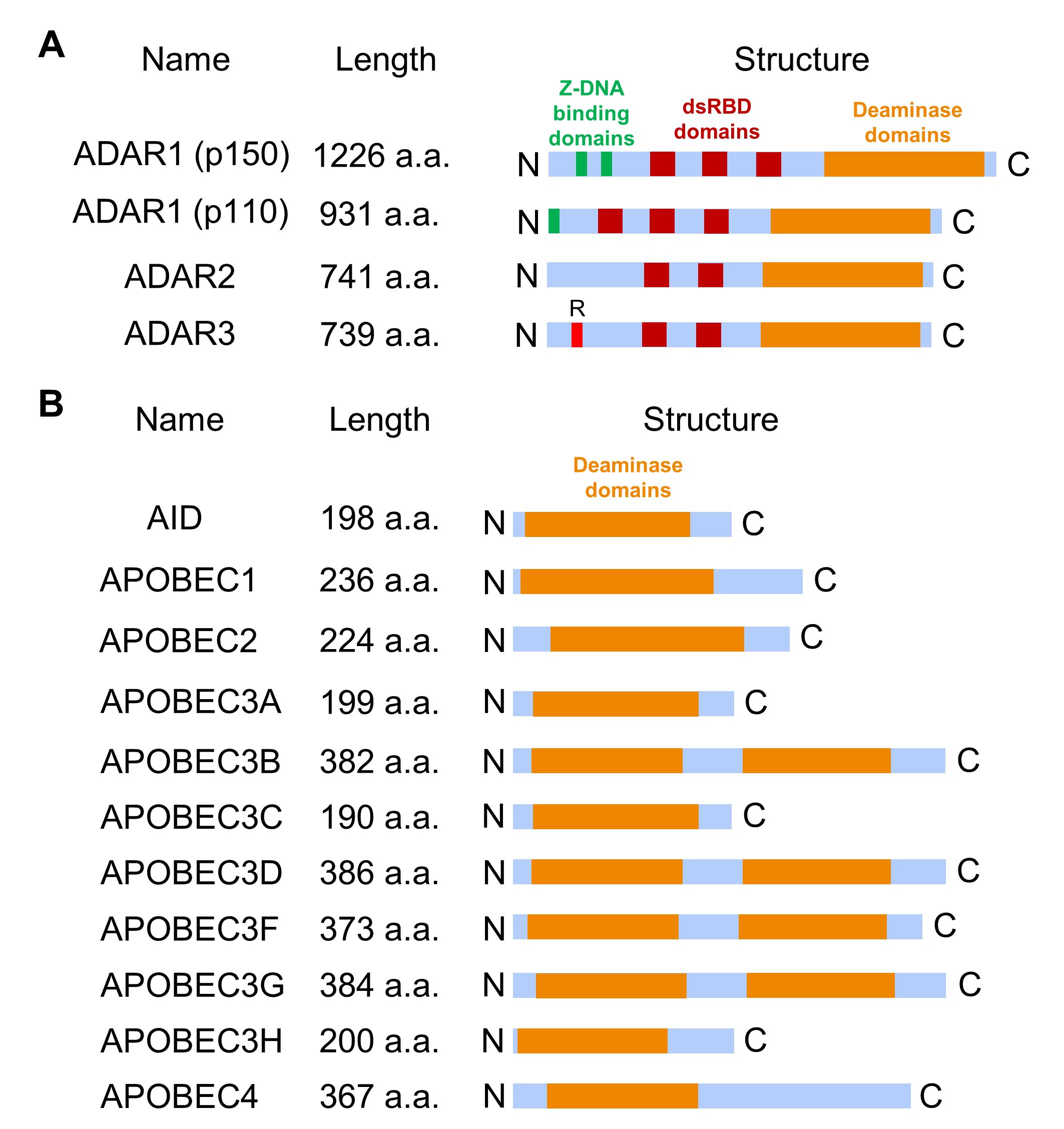

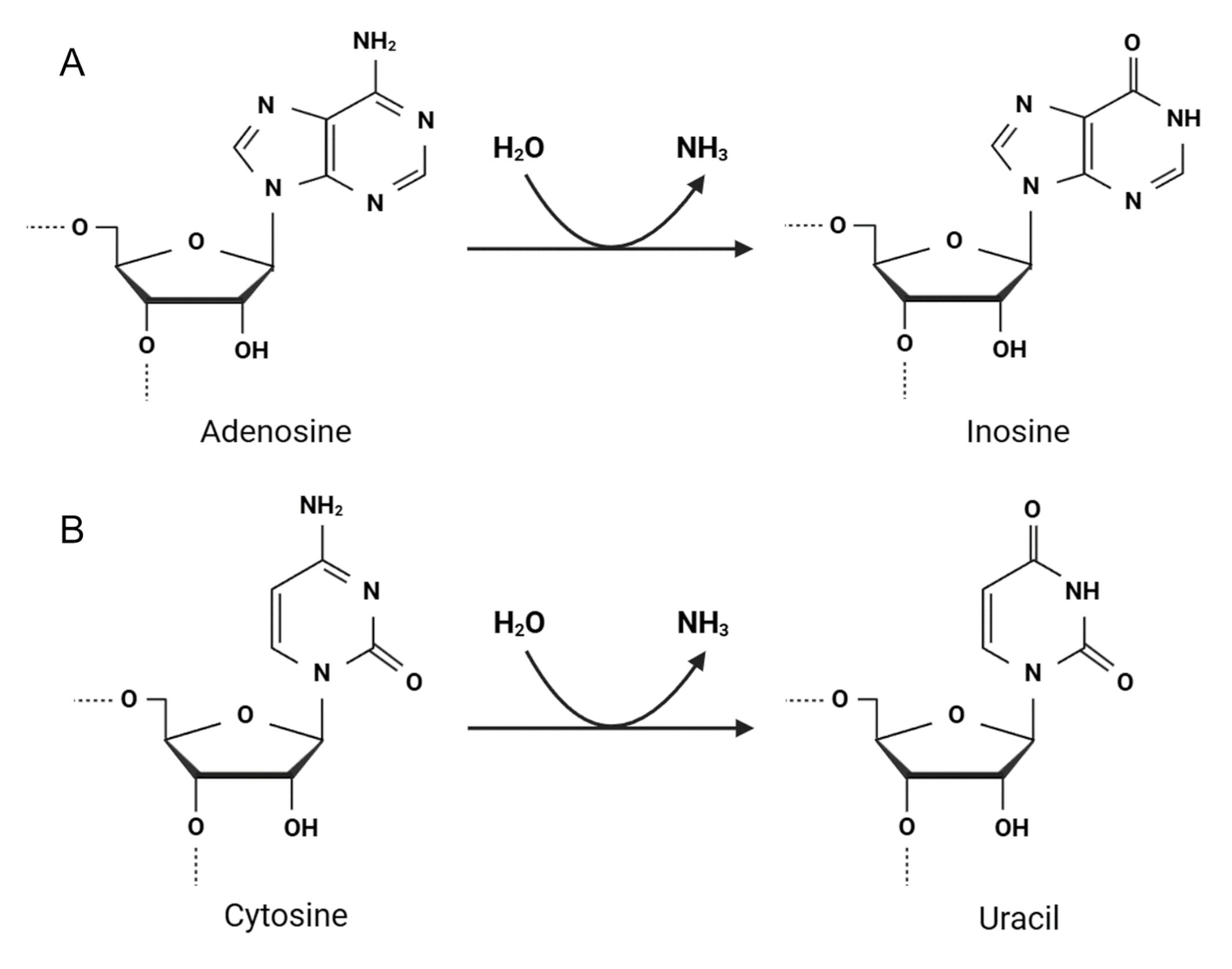

There are three members of the ADAR family, ADAR1 (with two isoforms, ADAR1 p150 and ADAR1 p110), ADAR2 (ADARB1), and ADAR3 (ADARB2), with the following domain structure: a conserved catalytic deaminase domain at the C-terminus, double-stranded RNA binding domains (three in ADAR1 p110 and ADAR1 p150; two in ADAR2 and ADAR3) [25], zigzag DNA (Z-DNA) binding domains in ADAR1 and N-terminal arginine-rich domain (R-domain) for single-stranded RNA binding in ADAR3 (Fig. 3A) [10, 21]. ADAR1 isoforms can be expressed from two alternative promoters: expression of ADAR1 p110 is controlled by a constitutively active promoter, and the ADAR1 p150 is synthesized from an interferon-inducible promoter to regulate interferon signaling and control the innate immune response to exogenous interfering RNAs [26, 27, 28]. In vitro studies demonstrated that ADAR1 and ADAR2 dimerize to edit dsRNA, whereas ADAR3 exists as a monomer [6, 29]. Unlike ADAR1 and ADAR2, ADAR3 lacks deaminase activity and is primarily expressed in the brain [30]. It contains an arginine-rich domain (Fig. 3A) that enables the enzyme to bind to single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) and dsRNA through the corresponding domains [30].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The domain structures of RNA editing proteins. (A) ADAR protein domain structure includes several double-stranded RNA binding domains (dsRBD) that mediate RNA binding specificity and deaminase domain essential for converting adenosine to inosine. Additionally, ADAR1 has a zigzag DNA (Z-DNA) binding domain, while ADAR3 contains a distinctive arginine-rich R-domain. (B) APOBEC family member domain structure contains one (in AID, APOBEC1, APOBEC2, APOBEC3A, APOBEC3C, APOBEC3H, and APOBEC4) or two (in APOBEC3B, APOBEC3D, APOBEC3F, and APOBEC3G) core deaminase domains. AID, activation-induced deaminase.

Another significant type of RNA editing involves the deamination of cytosine to uracil, catalyzed by enzymes from the APOBEC family. To date, eleven APOBEC family genes have been identified, and in mammalian cells, the APOBEC family is divided into several subtypes (Fig. 3B) [6, 21]:

-APOBEC1, which is essential for maintaining cholesterol levels and lipid metabolism;

-APOBEC2, which is essential for cardiac and skeletal muscle development;

-APOBEC3 proteins (a group of seven paralogues: APOBEC3A, APOBEC3B, APOBEC3C, APOBEC3D, APOBEC3F, APOBEC3G, APOBEC3H), which are an important part of the innate immune system [14];

-activation-induced deaminase (AID), which is an important participant in the development of the adaptive immune response;

-APOBEC4, whose function is still unknown.

APOBEC1 is the first identified and most extensively studied member of the APOBEC protein family, whose name comes from its first editing target, and it is required for the maturation of different forms of apolipoprotein B mRNA: ApoB-100 and ApoB-48 [5, 6]. Full-length human APOBEC1 protein consists of 236 amino acid residues, with the 15–187 N-terminal residues forming the deaminase domain, which shares high identity with other APOBEC proteins, and the C-terminal residues 188–236 of the C-terminal domain, which contains a large number of hydrophobic residues for both dimerization and RNA editing [31, 32]. APOBEC proteins have a similar deaminase domain structure, but only APOBEC1, 3A, 3B, and 3G mediate RNA editing of cytosine to uracil.

RNA editing proteins and RNA editing events are widespread, complex and diverse; however, the impact of this phenomenon on organisms is not fully understood. Studying the mechanisms of RNA editing events and their influence on cellular processes may contribute to the identification of novel disease biomarkers and the improvement of personalized therapies. This review discusses the main approaches to study RNA editing events, as well as the available relevant software. The impact of RNA editing on major DNA repair pathways will also be discussed, and the main parameters for the evaluation of RNA editing activity will be analyzed.

ADAR1 acts as a suppressor of interferon signaling and regulates the innate immune response to exogenous interfering RNAs [33]. Its main function is to edit endogenous dsRNAs to suppress their recognition as foreign dsRNAs, which typically activate the RIG-I-like receptor pathway (RLP) and initiate a type I interferon response. In addition, several target transcripts have been identified for ADAR1 proteins that represent different molecular pathways [34, 35, 36]. Changes in the expression and structure of ADAR1 can lead to disease progression. For instance, abnormal expression of ADAR1 leads to the production of interferon (IFN), which may contribute to enhancing the autoimmune response [26, 27, 28]. Furthermore, ADAR1-deficient mice die during embryogenesis for various reasons, including high levels of type I IFN, liver failure, hematopoietic dysfunction, and apoptosis [26]. In humans, mutations in the ADAR1 gene and in its key domains (deaminase, Z-DNA binding and dsRNA binding) play a key role in the onset and development of many types of diseases, such as Aicardi-Goutière syndrome [37]. It is hypothesized that ADAR1 may also be involved in the diversification and clonal evolution of RNA sequences in viral genomes, such as SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus [38], but there is ongoing debate regarding the deamination of viral RNA, and further validation in this area is needed [39]. Notably, a recent study shows that the ADAR1 protein (p110 isoform) plays an important role in resolving R-loops formed in telomeric repeat regions by editing RNA in RNA:DNA hybrids, thereby stabilizing the genome of tumor cells [40].

ADAR2 is especially highly expressed in the central nervous system, where it is

mainly responsible for site-specific editing of adenosines in short hairpin RNA

transcripts [41]. For example, ADAR2 targets the transcript GRIA2, which

encodes the B-subunit of the glutamate receptor. This editing results in the

replacement of glutamine with arginine (Q-to-R) in the AMPA

(

In addition, a DNA repair study has shown that A-to-I RNA editing can influence and alter the repair mechanisms of double-strand DNA breaks, involving numerous RNA-based factors in these processes [48], such as DNA-RNA hybrids, which are often observed near double-strand DNA breaks and represent both pre-existing R-loops and R-loops formed due to breaks in transcribed regions. These hybrids are subject to modification by RNA editing enzymes, particularly ADAR2 [49]. The mismatches introduced by RNA editing weaken the binding affinity between the RNA and the DNA strand, thereby facilitating the unwinding of the structure through the helicase activity of the senataxin (SETX) protein and promoting DNA resection. Consequently, inhibiting the ADAR2 enzyme can render cells hypersensitive to genotoxic agents, enhance genomic instability, and prevent homologous recombination by disrupting DNA resection [49]. On the other hand, R-loops can themselves be the source of double-strand breaks [50], and reducing the accumulation of R-loops or their lifetime may decrease the risk of such breaks.

In mammals, mRNA editing events rarely occur in coding sequences and cause amino acid alterations, and mostly change non-coding regions, such as introns and untranslated regions, especially by ADARs. Moreover, RNA editing is widespread in 3′-UTRs enriched with Alu repeats (repetitive short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), which are considered the main RNA editing targets) because copies of Alu elements can form dsRNA hairpins [22]. Although ADAR1 and ADAR2 share common targets and domain structure, mainly recognizing short and incompletely paired dsRNA, ADAR1 can also indiscriminately edit hairpins resulting from the pairing of inverted copies of Alu transposable elements in pre-mRNA in many human tissues [10, 21]. Notably, A-to-I editing events can either create a new target for microRNAs or simply disrupt complementarity between microRNA and mRNA [51]. In total, over 50,000 editing sites have been identified in 3′-UTRs of mRNAs enriched with Alu elements that serve to recruit ADARs [51]. Like ADARs, APOBEC family proteins, especially APOBEC3, edit mainly non-coding and intronic regions, including Alu sequences [20, 52], but also the other types of transposable elements, such as long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), or endogenous retroviral sequences [14].

Unlike ADAR proteins, APOBEC family enzymes are not only capable of editing RNA. They can also edit single-stranded genomic DNA during transcription, leading to uracil formation in DNA [6]. This event is crucial for innate defense against viruses, as it reduces viral replication [21]. Also, genomic cytosine methylation is known to play an important role in the regulation of gene expression, and whole genome demethylation occurs early in development. APOBEC enzymes may be important for this process. Both APOBEC and methylcytosine dioxygenase are involved in cascades that eliminate the modification of 5-methylcytosine through deamination and oxidation, respectively [53]. AID (encoded by the AICDA gene) and APOBEC proteins convert cytosine with a methyl group to uracil, resulting in DNA mismatches. These mismatches are subsequently processed by error-prone DNA repair mechanisms. In addition, AID is expressed in pluripotent cells and is required to maintain pluripotency in fibroblasts [54, 55].

The AID deaminase from the AID/APOBEC family, which participates in antibody diversification through immunoglobulin recombination, was initially considered an RNA editing enzyme due to the similarity of its structure and deamination activity to APOBEC1. However, AID has been shown to deaminate only single-stranded DNA during transcription at immunoglobulin loci, a process facilitated by the formation of an R-loop [53]. It may result in A:T base pair insertion into the DNA sequence during DNA replication or cause DNA breakage due to base excision.

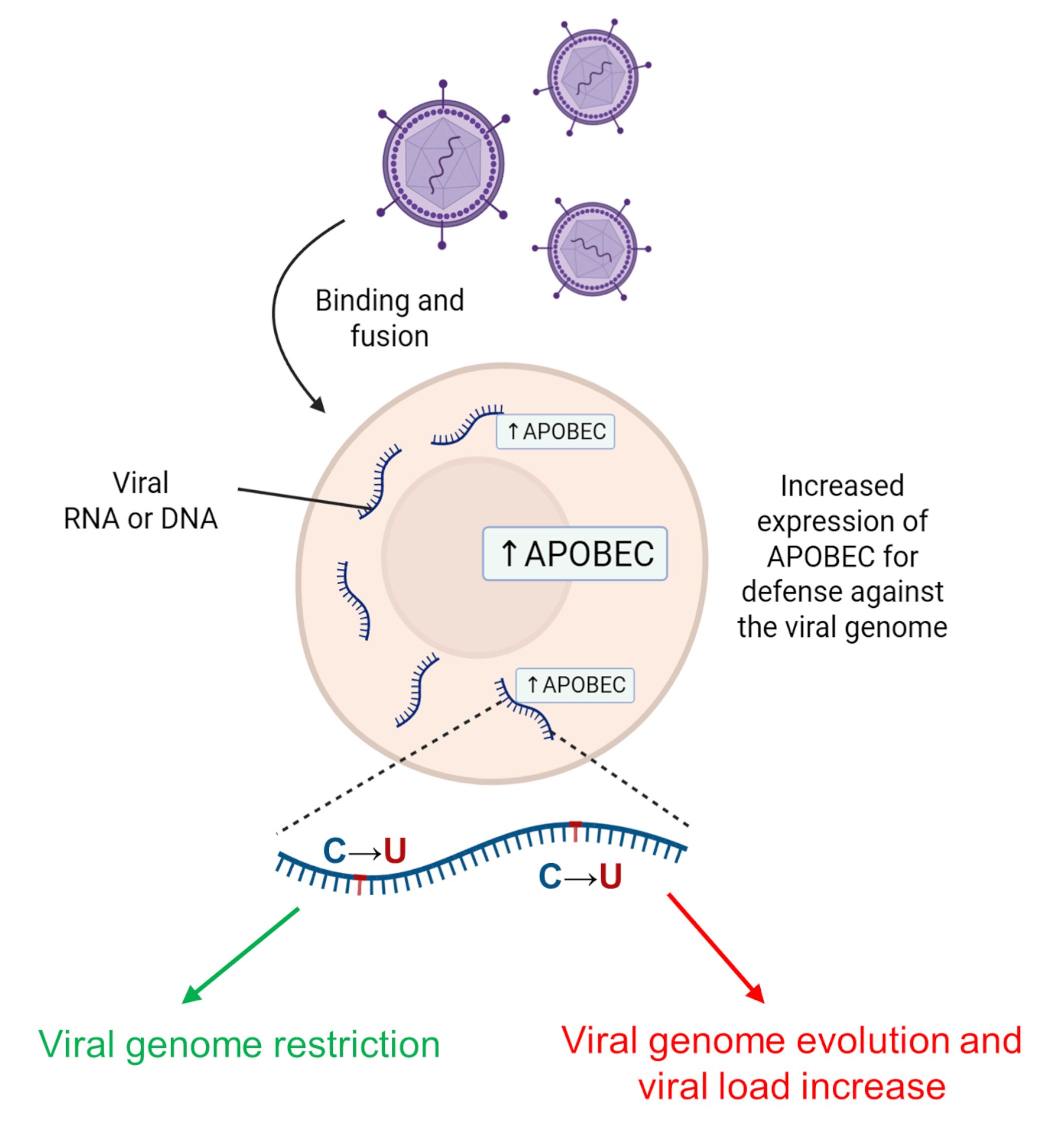

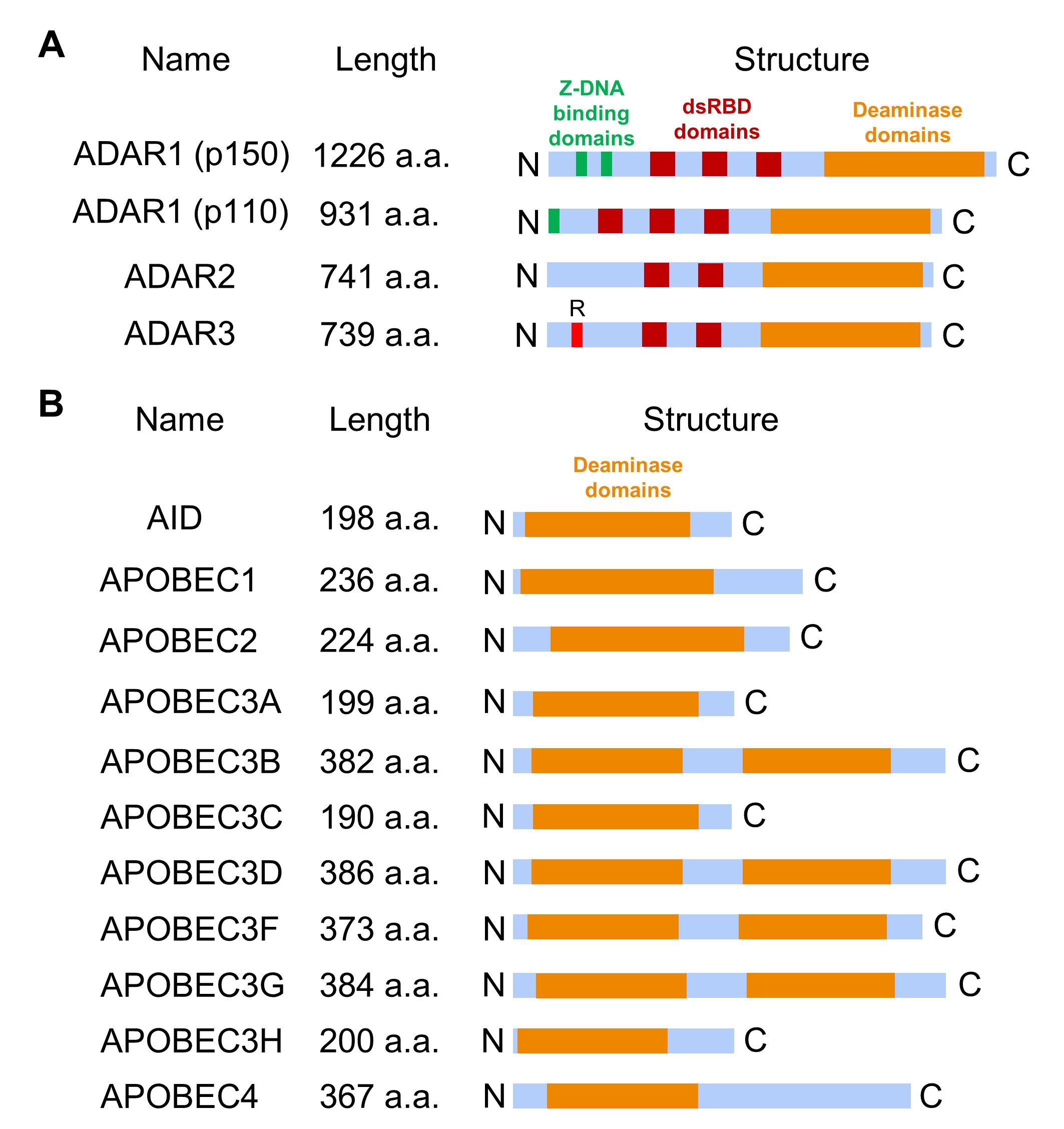

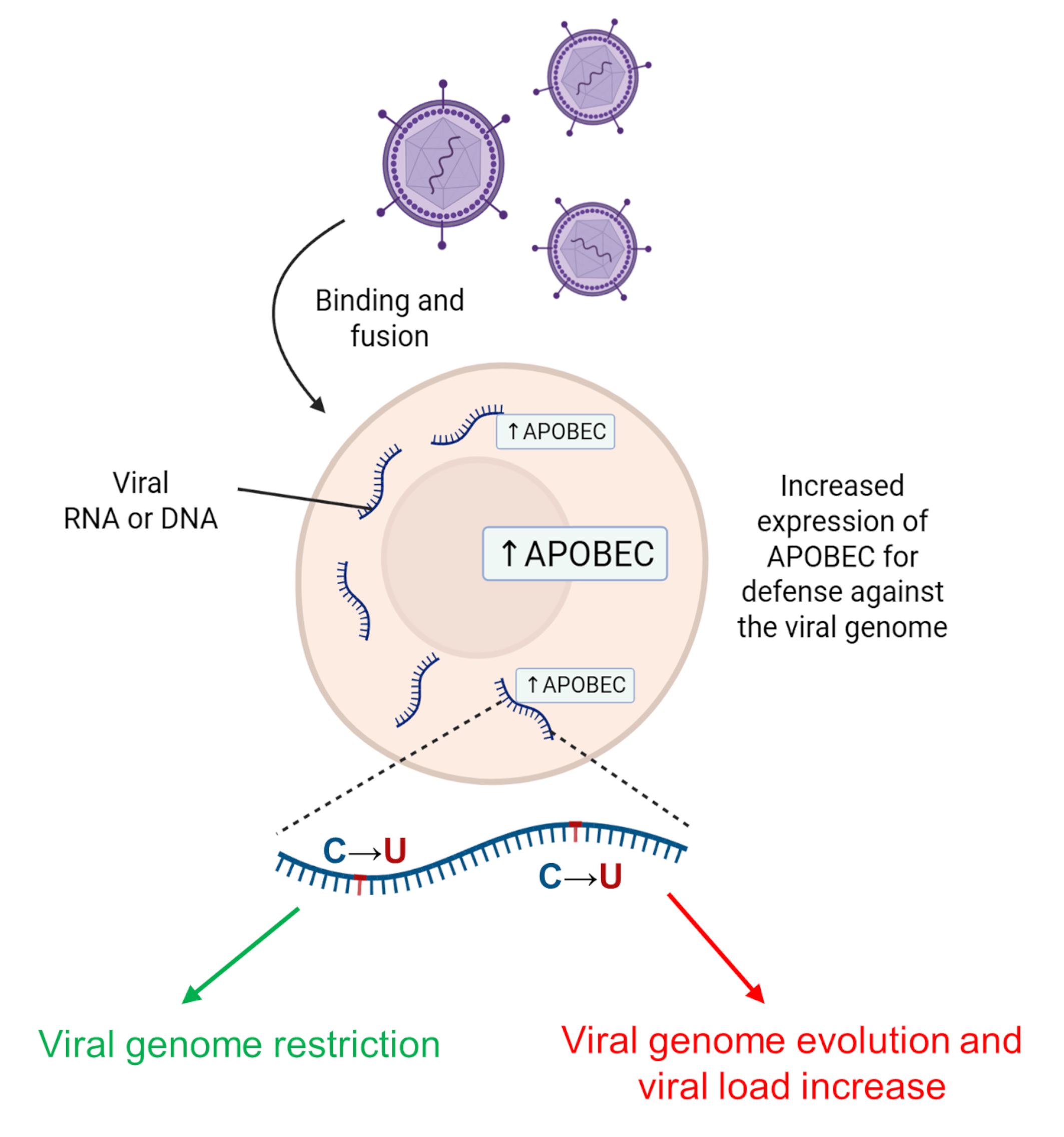

The APOBEC3 subfamily is another group of catalytically active deaminases in the AID/APOBEC family that includes seven different types of APOBEC3 (Table 1, Ref. [2, 20, 41, 43, 45, 46, 47, 53, 56, 57, 58, 59]) expressed in humans [21]. Like APOBEC1 and AID proteins, APOBEC3 proteins are DNA mutators and have key functions in the antiretroviral immune response and the regulation of innate retrotransposon activity. Notably, an increasing number of copies of APOBEC3 family genes may be a major evolutionary driver of a decreased proliferation of transposable elements in the DNA of the human lineage [14]. Most APOBEC3s are located in the cytoplasm, but APOBEC3A and APOBEC3C are nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins, APOBEC3B is predominantly located in the nucleus for defense against viruses [60]. For instance, APOBEC3G is an antiviral agent restricting human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) proliferation that targets reverse transcribed single-stranded cDNA [61]. In response to increased viral load, the action of APOBEC group enzymes can lead to either viral death and decreased viral load or viral evolution. However, the presence of HIV Vif protein (a viral infectivity factor) enhances proteasome-mediated degradation of APOBEC3, thereby promoting viral infectivity [20]. Fig. 4 represents a general scheme of antiretroviral immune response to viral infection. When the viral genome is in the cell as single-stranded RNA or reverse transcribed single-stranded cDNA, the expression level of APOBEC proteins increases, leading to C-to-U editing. This event may lead to either the prevention of viral replication and viral genome restriction or the evolution of the viral genome, which may promote immune escape.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Effect of AID/APOBEC family enzymes in response to viral invasion. In response to increased viral load, the action of APOBEC group enzymes can lead to either viral death with decreased viral load (green arrow) or viral evolution (red arrow). AID, activation-induced deaminase. Created with BioRender.com.

| RNA editing enzyme | RNA editing | DNA editing | Biological function | References |

| ADAR1 | + | - | A suppressor of interferon signaling and a regulator of the innate immune response to exogenous RNA | [56] |

| ADAR2 | + | - | Site-specific editing of adenosines in short hairpin RNA transcripts within the brain | [41] |

| ADAR3 | - | - | Neuronal differentiation regulation. Memory formation. Possible ADAR2 inhibitor | [43, 45, 46, 47] |

| AID | - | + | Immunoglobulin diversification | [2, 20, 53] |

| APOBEC1 | + | + | Regulation of cholesterol metabolism; defense against viruses | [2, 20, 53] |

| APOBEC2 | - | - (only binding) | Involved in musculogenesis | [53, 57, 58] |

| APOBEC3A | + | + | Defense against viruses and retroelements | [2, 20, 53] |

| APOBEC3B | + | + | Defense against viruses and retroelements | [2, 20, 53] |

| APOBEC3C | - | + | Defense against viruses and retroelements | [2, 20, 53] |

| APOBEC3D | - | + | Defense against viruses and retroelements | [2, 20, 53] |

| APOBEC3F | - | + | Defense against viruses and retroelements | [2, 20, 53] |

| APOBEC3G | + | + | Defense against viruses and retroelements | [2, 20, 53] |

| APOBEC3H | ND | + | Defense against viruses and retroelements | [2, 20, 53] |

| APOBEC4 | ND | ND | Unknown function. Predominantly expressed in testes | [59] |

ND, Not Determined.

Given the essential roles these enzymes play in regulating RNA integrity, it is critical to explore how their dysregulation contributes to oncogenesis and whether RNA hyper-/hypo-editing is associated with increased/decreased expression of ADAR and APOBEC genes.

Therefore, while APOBEC enzymes were originally thought to edit only immunoglobulin loci and ApoB transcript, the range of their identified targets has broadened to encompass numerous viruses and transposable elements (Table 1). Their capacity to edit transposable element sequences and genomic DNA may not only drive rapid genome evolution but also contribute to tumor development.

Increasing evidence suggests that RNA editing levels, ADAR and APOBEC expression, and specific edited targets hold potential as prognostic biomarkers for cancer progression in clinical practice, since abnormal RNA editing may lead to the accumulation of cells with multiple altered proteins, thereby contributing to tumor development [21, 62]. In most studies, RNA editing events were analyzed based on available RNA sequencing data from corresponding normal tissues of the same patients [7, 63]. For each tumor type, significant differences in editing activity were found between the corresponding tumor and normal samples: head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, breast cancer, thyroid cancer, and lung adenocarcinoma showed excessive editing, whereas kidney cancers showed low levels of editing sites. However, overall the level of editing was not fundamentally different or characteristic for a significant proportion of tumors [63].

Abnormal expression of ADAR and APOBEC between different tumor types compared to healthy tissue and within cancer types can help identify distinct molecular profiles to better understand cancer progression and guide the development of effective therapeutic strategies. For instance, ADAR-mediated RNA editing plays an important role in oncogenesis, as ADAR is overexpressed in nearly all tumors compared to normal tissues, leading to enhanced A-to-I editing activity, except in chromophobe renal cancers and renal papillary cancers [21]. RNA editing in tumors is high and more frequent in coding transcripts, leading to increased proteome diversity during oncogenesis [64]. Although specific transcripts are markedly predominant in certain cancer types, it is important to consider the overall aberrant RNA editing activity in the transcriptome during oncogenesis. This broader perspective has been shown to be crucial, especially when assessing the prognosis of diseases, such as multiple myeloma [65]. For example, the alpha-3 subunit of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor (GABRA3) activates the protein kinase B pathway (AKT pathway), thus promoting migration, invasion and metastasis of breast tumor cells.

However, the ADAR1 p110 enzyme isoform, responsible for A-to-I editing, reduces GABRA3 expression on the cell surface, thereby inhibiting AKT activation necessary for cell migration and invasion during breast cancer metastasis [66]. In another study, ADAR-mediated A-to-I editing of RHOQ (RhoQ GTPase) transcripts resulted in amino acid substitutions associated with invasiveness. Specifically, editing of adenosine to inosine leads to the replacement of asparagine with serine at amino acid position 136, which causes actin reorganization in the cytoskeleton and increases the potential for invasion in colorectal cancer [67]. Moreover, in hepatocellular carcinoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer, and breast tumors, the overexpression of ADAR1 results in the production of an oncogenic variant of antizyme inhibitor 1 (AZIN1; substitution S367G) [68]. The edited variant of AZIN1 exhibits a higher affinity for antizyme, promoting the translocation of AZIN1 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. It serves as an ornithine decarboxylase analog, blocking the antienzyme-mediated degradation of ornithine decarboxylase and cyclin D1, thereby driving increased cell proliferation, metastatic potential, and tumor initiation.

Moreover, a study have shown that ADAR activity regulates the mRNA of proteins involved in DNA repair and cell cycle regulation [69], highlighting a novel role for ADAR in tumor development and progression. For example, in non-small cell lung cancer and multiple myeloma, increased expression of the ADAR1 gene leads to higher A-to-I RNA editing levels at the K242R site of the Nei-like DNA glycosylase 1 (NEIL1) gene transcript (where lysine is replaced by arginine at position 242), resulting in increased tumor cell proliferation and drug resistance [65, 70]. Normally, NEIL1 functions as a DNA glycosylase that removes oxidized bases to generate single-strand breaks (a DNA repair mechanism known as nucleotide excision repair, NER). In cancers, the edited NEIL1 protein exhibits reduced ability to repair oxidative DNA damage, leading to the accumulation of double-strand breaks. This triggers activation of double-strand break repair mechanisms, thereby promoting increased cell survival. Interestingly, editing at the K242R site has been found to enhance tumor sensitivity to therapeutic agents that induce both single- and double-strand DNA breaks [65].

In addition, according to in vitro and in vivo studies, gastric tumors demonstrate an antagonistic pattern of influence of RNA editing enzymes on tumor development: ADAR1 promotes tumor development through deaminase activity and promiscuous editing of the transcript (acts as an oncogenic agent), whereas ADAR2 suppresses podocalyxin (PODXL) activity by editing codon 241 (replacing histidine with arginine). In its unedited form, PODXL exhibits tumorigenic potential [71]. In glioblastoma, RNA editing of the cell division cycle 14B (CDC14B) protein mediated by ADAR2 activates the S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (Skp2)/cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (p21)/cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (p27) pathway, leading to inhibition of proliferation [72]. In addition to these proteins, numerous editing sites are also located in GLI family zinc finger 1 (GLI1), which is highly expressed in multiple myeloma [73], and in COPI coat complex subunit alpha (COPA), which is involved in oncogenesis in liver cancers [74]. The results regarding the effects of ADAR activity in tumor cells highlight ADARs as novel potential therapeutic target. ADAR inhibitors and screening system based on highly sensitive reporters may be effective in the therapy of tumors with ADAR overexpression, such as breast, lung and liver cancer [75]. Since ADAR1 is a suppressor of interferon signaling, its absence can lead to the induction of interferons and inflammation in tumors that are not amenable to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Thus, it underscores the role of ADAR1 as a promising therapeutic target for cancer immunotherapy [76, 77]. Although no ADAR inhibitors are currently approved as cancer therapeutics, a preliminary study indicates some potential drug candidates, such as 8-azaadenosine and 8-chloroadenosine [78].

Notably, most RNA editing events were observed in the 3′-UTRs of mRNAs enriched with Alu repeats that can affect the specificity to microRNAs, effect of which is found to be suppressed in tumor cells [22]. An example is the editing of the 3′-UTR of mRNA encoding the DNA fragmentation factor alpha (DFFA) subunit, which is a protein that initiates DNA fragmentation during apoptosis. The editing of DFFA mRNA by ADAR in a breast cancer cell line creates a target site for miR-140-3p, resulting in reduced DFFA levels and the inhibition of cellular proliferation [79].

Despite the wide variety of editing targets for ADAR family enzymes, APOBEC enzymes, which are responsible for C-to-U editing, are also clinically relevant. Although little is known about the effects of hypo-editing and hyper-editing by APOBEC proteins, the APOBEC1, APOBEC2 and APOBEC4 gene expressions are predominantly limited to intestinal, muscle, and glandular tissues, respectively. In contrast, APOBEC3 genes are more abundantly expressed in immune system cells. Notably, these proteins were identified as major mutagenesis factors in many human cancer types, including breast cancer [80]. Additionally, patients with structural alterations in the APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B genes have been observed to have an elevated risk of developing breast, ovarian, liver, lung, and head and neck cancers [81, 82, 83].

Given that APOBEC proteins are capable of editing DNA, they often induce mutagenesis in tumors, which can lead to kataegis, large-scale C-to-T clusters, resulting in a predictive signature with prognostic value [84, 85, 86]. For instance, in breast cancer, the overexpression of APOBEC3B has been linked to DNA editing and the inactivation of p53. Additionally, APOBEC3B expression is associated with a poor response to treatment in estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast tumors and contributes to resistance to tamoxifen [87].

APOBEC expression also strongly influences DNA repair pathways and the development of tumors. The study of bladder cancer [88] demonstrated an antagonistic pattern in the effect of APOBEC expression on the formation of mutations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) and rat sarcoma (RAS) oncogene families, mutations in DNA damage response genes, and genes regulating chromatin structure and immune response. In this study, patients with high APOBEC levels showed higher overall survival compared to those with low APOBEC levels. Tumors with high APOBEC expression were more likely to exhibit mutations in DNA damage response genes (TP53, ATR, BRCA2) and genes regulating chromatin structure (ARID1A, MLL3), whereas tumors with low APOBEC expression were more likely to have mutations in FGFR3 and KRAS oncogenes. APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B expression correlated with multiple mutations across different molecular subtypes of bladder tumors. Moreover, APOBEC activity is associated with increased immune signatures, including interferon signaling [88]. Therefore, tumors with elevated APOBEC levels are more likely to exhibit mutations in DNA damage response genes and chromatin regulatory genes.

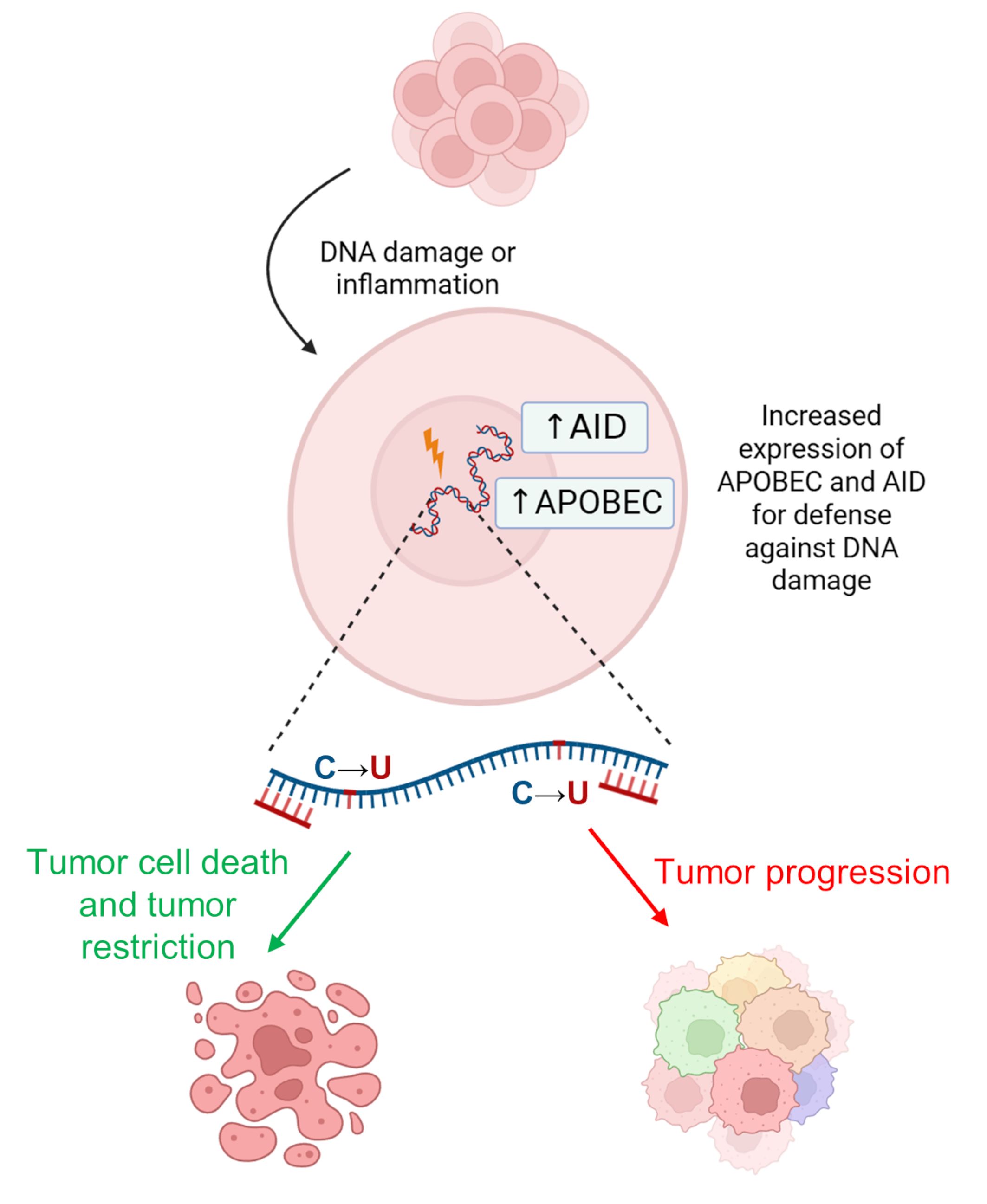

These events associated with the deaminase activity of APOBEC enzymes result in chromosomal instability [89]. In particular, expression of the APOBEC3 genes can be induced by the tumor microenvironment in an attempt to suppress malignant cells through local hypermutations. However, when APOBEC3-mediated mutations do not result in tumor cell death (i.e., cells with non-lethal mutation levels remain alive), the tumor adapts by developing enhanced genetic heterogeneity (Fig. 5). Subsequently, some APOBEC family members (mainly nuclear) have also been shown to cause DNA damage and mutagenesis [20]. Therefore, APOBEC inhibitors are also promising molecules for targeted therapy that are in the early stages of development [90, 91].

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Action of AID/APOBEC enzymes in carcinogenesis. It can lead to either cancer cell death (green arrow) or further cancer progression and increased genetic heterogeneity (red arrow). Created with BioRender.com.

Notably, RNA and DNA editing by APOBEC3A could be interdependent, as mutations in DNA can control RNA editing activity via specific hotspots [92, 93]. Since APOBEC3 proteins can bind to single-stranded RNA, it is possible that additional APOBEC3 family members could fulfill this versatile RNA/DNA targeting role, potentially with an appropriate cofactor yet to be discovered [94]. Thus, polynucleotide deaminases that exhibit versatility in targeting substrates, and their coordinated editing of RNA and DNA, may be key to better understanding oncogenesis. Likewise, there are many known targets for RNA editing enzymes, depending on the individual enzyme (Table 2, Ref. [2, 6, 21, 64, 65, 66, 67, 71, 72, 73, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105]) [2, 6, 21]. Edited targets from this table could also play a significant role in tumor progression and serve as prognostic biomarkers and targets for personalized therapy.

| RNA editing enzyme | Targets and disease | References |

| ADAR1 | AZIN1 (S367G) — Hepatocellular carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer, and breast cancer | [2, 6, 21, 95, 96, 97] |

| BLCAP (YXXQ motif) — Hepatocellular carcinoma and cervical cancer | [2, 6, 21, 98] | |

| GABRA3 (I342M) — Reduces metastatic potential of cancer cells | [2, 6, 21, 66] | |

| CCNI (R75G) — Induces antigen-specific cytotoxicity against tumor cells via CD8+ T cells. Ovarian cancer, melanoma, and breast cancer | [6, 21, 99] | |

| GLI1 (R701G) — Multiple myeloma | [6, 21, 73] | |

| NEIL1 (K242R) — Non-small cell lung cancer and multiple myeloma | [2, 21, 65] | |

| PCA3 (multiple sites) — Prostate cancer | [6, 21] | |

| FLNB (M2269V) — Hepatocellular carcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | [2, 21, 95] | |

| RHOQ (N136S) — Colorectal cancer | [2, 6, 21, 67] | |

| CDK13 (Q103R, K96R) — Hepatocellular carcinoma | [21, 100] | |

| PODXL — Gastric cancer | [2, 6, 21, 71] | |

| EEF1A1 (T104A) — Breast cancer | [64] | |

| IFI30 (T223A) — Breast cancer | [64] | |

| SERPINB6 (E237G) — Breast cancer | [64] | |

| ADAR2 | IGFBP7 (R78G) — Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and breast cancer | [2, 6, 21, 101] |

| CDC14B — Glioblastoma | [2, 6, 21, 72] | |

| COPA (I164V) — Breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and colorectal cancer | [2, 6, 21, 64] | |

| SLC22A3 (N72D) — Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | [2, 6, 21, 102] | |

| PODXL — Gastric cancer | [2, 6, 21, 71] | |

| IFI30 (T223A) — Breast cancer | [64] | |

| COG3 (I635V) — Breast cancer | [64] | |

| FLNB (Q2327R) — Breast cancer | [64] | |

| AID | CDKN2 — Gastric cancer | [2, 103] |

| APOBEC1 | NAT1 — Hepatocellular carcinoma | [6, 104] |

| NF1 (R1306*) — Peripheral nerve sheath tumors | [6, 21, 105] |

AZIN1, antizyme inhibitor 1; BLCAP, bladder cancer associated protein; GABRA3, gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor subunit alpha-3; CCNI, cyclin I; GLI1, GLI family zinc finger 1; NEIL1, Nei-like DNA glycosylase 1; PCA3, prostate cancer antigen 3; FLNB, filamin B; RHOQ, Ras homolog family member Q; CDK13, cyclin-dependent kinase 13; PODXL, podocalyxin; EEF1A1, eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1; IFI30, interferon gamma-inducible protein 30; SERPINB6, serpin family B member 6; IGFBP7, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7; CDC14B, cell division cycle 14B; COPA, COPI coat complex subunit alpha; SLC22A3, solute carrier family 22 member 3; COG3, component of oligomeric Golgi complex 3; CDKN2, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2; NAT1, N-acetyltransferase 1; NF1, neurofibromin 1.

Furthermore, RNA editing enzymes can be used in genome engineering technologies based on their activity in A-to-I(G), as well as C-to-U editing in DNA or mRNA. Gaining a deeper insight into their substrate specificity can aid in the development and optimization of these tools. Meanwhile, many studies have examined the efficiency of engineered CRISPR-based systems, with ADAR-based systems predominantly used for mRNA editing and APOBEC-based systems for DNA editing [20, 106, 107, 108, 109]. These technologies could be beneficial for tumor tissues exhibiting low levels of RNA editing, such as kidney cancers [63]. In general, both ADAR and APOBEC have been shown to promote oncogenesis due to their unique features, which include alteration in their targeting activity, aberrant RNA editing or DNA editing, and complex actions that enhance tumor evolution and adaptation through genomic, transcriptomic, and downstream proteomic heterogeneity [94].

Thus, editing of coding transcripts has important clinical implications in tumor development related to the accumulation of both A-to-I and C-to-U mutations. However, RNA editing events most commonly occur in non-coding RNAs, such as microRNAs.

Editing within the coding region of mRNA can lead to mutations that enhance diversity at both the transcriptomic and proteomic levels. However, editing in the non-coding regions of RNA can influence RNA secondary structure, circular RNA biosynthesis, alternative splicing of mRNA, and particularly the maturation and targeting of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and microRNAs to mRNAs [10, 12, 13]. MicroRNAs are approximately 22-nucleotide small RNAs that play a role in the post-transcriptional regulation of genes and are implicated in various cellular pathways and pathological processes, including tumorigenesis [10]. For example, there are recent studies on ADAR-mediated editing of microRNAs in the brain, which can regulate the microRNA expression and activity depending on the mature or primary precursor form of microRNAs [110, 111, 112]. The dsRNA precursors of pri-miRNAs can undergo A-to-I conversion at different processing steps by editing-dependent and editing-independent mechanisms. For example, recognition of hairpin structures of pri-miRNAs by the Drosha complex can be subject to A-to-I editing, which was first described for pri-miR-142 and other immature pri-miRNAs [10]: pri-miR-33, pri-miR-379, pri-miR-455, etc. It has been analyzed that 10–20% of microRNAs undergo editing at the level of pri-miRNAs. For example, about 20% of pri-miRNAs found in the brain undergo editing [10]. Editing can also occur at the stage of mature microRNA formation from pre-miRNA. A well-known example is ADAR1-mediated editing of pre-miR-151 in the cytoplasm, which results in complete blockage of processing by the enzyme Dicer.

RNA editing can also occur within mature microRNAs during tumorigenesis [51, 113]. Notably, in a study [51], increased microRNA editing was positively correlated with survival. In melanoma, insufficient editing of miR-455-5p promotes tumor cell growth because this microRNA targets cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein (CPEB1), which is a tumor suppressor [114]. ADAR1 can regulate the biogenesis of miR-222 at the transcriptional level and impact melanoma immunoresistance by targeting RAP2A, a member of the RAS protein family [115]. The antitumor activity of ADAR2 has also been identified in glioblastoma. Along with other miRNAs, this enzyme can regulate the abundance of miR-21 and miR-222/-221 precursors and reduce the expression of their mature oncogenic miRNAs [116]. It has also been shown that in prostate cancers, ADAR1 promotes cell proliferation by editing the lncRNA PCA3, which binds the tumor suppressor PRUNE2, thereby reducing the concentration of the latter transcript [117]. In an analysis of the effects of APOBEC family enzymes on non-coding regions of transcripts, it was found that increased expression of APOBEC3G in colorectal cancers promotes their metastasis to the liver by inhibiting miR-29-mediated suppression of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2) [118].

In another study, microRNA editing events showed extensive correlation with key clinical parameters (e.g., cancer subtype, disease stage, and patient survival time) and several molecular factors [113]. In this study, the authors conducted a comprehensive investigation of miR-200b editing, which is a crucial suppressor of tumor progression, and discovered that the extent of miR-200b editing was correlated with patient prognosis, in contrast to the expression levels of wild-type miR-200b. In addition, experimental data showed that edited miR-200b, unlike its wild-type variant, enhanced cell invasion and migration by attenuating the inhibition of the transcription factors zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 and 2 (ZEB1 and ZEB2, respectively). Moreover, the edited form gains the ability to inhibit novel targets, such as the leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR), which is a suppressor of metastasis [113, 119].

It was also shown that ADAR-induced hyper-editing in cancers can impair miR-26a maturation. This event indirectly suppresses the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A), a cell cycle protein that prevents entry into mitosis [69]. Moreover, A-to-I editing of the mouse double minute 2 (MDM2)-regulating microRNA precursor, as well as the MDM2 (negative regulator of a tumor suppressor protein p53) 3′-UTR has been shown to stabilize their transcripts, leading to tumor progression [62, 69].

Another mechanism of transcript stability control was demonstrated in studies of apoptosis. ADAR1 targeting ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and radiation sensitive 51 (RAD51) mRNAs at their 3′-UTRs prevents Staufen1 binding and subsequent degradation. Consequently, this mechanism affects cell survival during apoptosis [120].

The studies described above highlight the importance of microRNA editing in gene regulation and indicate its potential as a biomarker for tumor prognosis and treatment. However, distinguishing RNA editing from DNA mutations, predicting RNA editing sites, and assessing the consequences of these events in coding and non-coding regions are challenging due to their diversity. Thus, the integrated application of DNA and RNA sequencing technologies, along with advanced experimental validation and data analysis techniques, may provide a solution.

As detailed earlier in this review, RNA modifications are of great importance in both normal physiology and pathology, and the impact of RNA editing in this context is becoming increasingly apparent [121]. The first RNA editing event was detected in 1991 when researchers identified a substitution on GluR mRNA using PCR [122]. The genomic DNA sequences encoding the specific channel segment of all subunits contained a glutamine codon, while the mRNAs of GluR subunits featured an arginine codon. By excluding multiple genes and alternative exons as potential sources of the arginine codon, they hypothesized that RNA editing was an active process that modified transcripts of three subunits. Additionally, quantitative PCR (qPCR) can be applied to detect RNA editing events at the quantitative level [123]. While the qPCR method offers the benefits of ease of use and low cost, it is limited to measuring A-to-I RNA editing frequencies at specific sites only. C-to-U and A-to-I(G) editing events are also identified using Sanger sequencing: the editing site shows a double peak that includes both the original and edited bases [124]. However, it is necessary to analyze genomic DNA from the same sample using Sanger sequencing, whereby the absence of a double peak can confirm the RNA editing event.

With modern genome and transcriptome sequencing technologies, bioinformatics tools, and a variety of large-scale datasets containing clinical information on tumors, it has become possible to assess and predict events and the impact of RNA editing on different biological processes and anti-tumor therapies [73].

Experimental methods are continually advancing, with new concepts and associated technologies emerging, including the aforementioned bioinformatics tools for analyzing RNA/DNA editing. Sequencing technologies play a crucial role in detecting and validating RNA modifications, particularly RNA editing. As DNA/RNA sequencing technology has advanced, the abundance of high-throughput sequencing data has facilitated the exploration of RNA editing sites. This is achieved by comparing RNA sequencing data with corresponding DNA sequencing data or using RNA sequencing data alone [7]. Moreover, various experimental techniques directly detect inosine, including the inosine chemical erasing sequencing method (ICE-seq) [125, 126] and specific ligation of inosine-cleaved sequencing (Slic-seq) [127].

In the ICE-seq method, RNA is treated with acrylonitrile to exclude the fragment containing inosine from subsequent sequencing. The processed profile is then compared with the unprocessed profile to pinpoint the precise editing site. The Slic-seq method is based on sequencing only RNA fragments that contain inosine with the endonuclease enzyme against inosine that is active for ssRNA and dsRNA and contribute to analyze editing sites in Alu and non-Alu elements [127]. A similar method includes inosine-specific cleavage by glyoxal modification and RNase T1 treatment [128]. However, these methods exhibit significant drawbacks. Firstly, enzymatic or chemical treatments often result in incomplete effects, with RNase T1 potentially causing RNA degradation. Secondly, different RNA modifications, such as methylations, can directly interfere with reverse transcription, resulting in numerous false-positive results. Thus, the optimal approaches for detecting RNA editing sites involve comparing paired large-scale RNA and DNA sequencing data and identifying site variants detected by RNA but not by DNA sequencing.

Although RNA/DNA comparisons can reliably identify RNA editing events, determining the specific enzyme responsible for an editing event can be challenging. For instance, C-to-U editing may result from deamination by various APOBEC family enzymes, such as APOBEC3A and APOBEC3B, making it difficult to pinpoint exactly the enzyme involved.

RNA editing events and specific enzymes can be identified using CRISPR/Cas gene editing tools, which result in a knockout of the enzyme of interest. This approach allows searching for editing sites at the transcriptome level by comparing them to the same wild type cells. Such comparisons enable the accurate identification of appropriate editing sites from transcriptome data [129].

The strategies described above for studying RNA editing events using genomic and transcriptomic data have several common steps, including pre-processing of sequencing data, mapping, RNA editing calling and annotating the resulting edited sites. Researchers commonly use popular mapping tools, such as STAR [130], HISAT2 [131], BWA [132], and Bowtie [133], when analyzing RNA editing levels. However, RNA editing calling is the most important step. There are various bioinformatic methods and tools for RNA editing event detection depending on the presence of matched RNA and DNA sequencing data and the repertoire of analyzed RNA editing targets.

In the presence of paired genomic and transcriptomic data, the method for

identifying RNA editing sites involves detecting DNA/RNA mismatches in samples

using tools like HaplotypeCaller in GATK [134] and Samtools [135], followed by

single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) removal, considering DNA mutations. It is

crucial to note that both DNA mutations and sequencing errors can result in false

positives, thus biasing the detection of RNA editing sites. In a breast cancer

study, researchers developed a bioinformatics pipeline to assess RNA editing

levels at known APOBEC3-mediated sites using exome and RNA sequencing data from

tumor and adjacent normal tissues [136]. Researchers identified the 411 most

edited targets (440 sites) with an average editing level ranging from 0.6% to

20% in

When only RNA sequencing data are available, numerous bioinformatic tools have been developed for identifying RNA editing, especially for A-to-I editing, which include tools such as REDItools2 [137], GIREMI [138], RNAEditor [139], RED-ML [140], JACUSA2 [141], and other methods [7]. Moreover, in study [142], researchers developed L-GIREMI, an analog of the short-read GIREMI tool applied to PacBio long-read RNA sequencing data that effectively manages read biases and sequencing errors, enabling high-accuracy identification of RNA editing events. Tools mentioned above are based on similar approaches to RNA editing detection involving the following steps: (i) read mapping, (ii) SNP calling (e.g., from the dbSNP database) and filtering, e.g., by read depth, to reduce false positive detection and (iii) RNA editing event annotation. As shown in a comparative study on the efficiency and accuracy of RNA editing detection with these tools [143], despite the advanced machine learning-based tools, such as RED-ML with a logistic regression classifier, REDItools2 (with STAR as the read aligner) based on the distribution of substitutions still remains the optimal choice because of its applicability for detection of both de novo and known RNA editing events. Using these tools, researchers have systematically identified RNA editing sites on a large scale and deposited the obtained information in specialized databases, notably REDIportal and RADAR, which evaluate A-to-I(G) substitutions [144, 145]. There are about 15.6 million editing sites in REDIportal and 2 million in RADAR. Compared to these databases, the MiREDiBase [146] for microRNAs includes about 3,000 editing sites in microRNAs and LNCediting [12] for lncRNAs contains about 200,000 editing sites in lncRNAs. Also, the REDIportal database is needed to filter false positive events according to an empirically observed distribution in RNA editing detection tools [143, 147]. Moreover, REDIportal automatically compares the resulting data with SNP databases (e.g., dbSNP) and stores SNP information. However, comprehensive databases like those mentioned above do not include de novo A-to-I editing sites, which is a reason to further improve bioinformatic and experimental validation methods. Moreover, these databases do not yet exist for the C-to-U editing events. This task is further complicated by the artifact deamination of cytosine residues during formalin fixation in the samples embedded in paraffin blocks [148].

To evaluate C-to-U editing levels and address this knowledge gap, several studies are developing tools to annotate C-to-U events. For instance, in the study [149], researchers developed the RNAsee (RNA site editing evaluation) tool, which combines rules-based and machine learning methods to predict and annotate APOBEC3-mediated RNA editing sites in the human transcriptome. The rule-based methods utilize a stem-identification algorithm to assign a score to cytosines found at the 5′-end of the loop of a stem-loop structure. Scores are calculated based on the stem structure and the presence of specific features, such as the presence of uracil in the loop. The machine learning component involves a random forest model that takes a 50-bit vector as input, representing 15 nucleotides preceding and 10 following a cytosine. A site is classified as an editing site if its probability of being edited exceeds 0.5.

There are different metrics to assess the overall level of RNA editing based on averaging the editing level across all detected sites, which are time- and computationally extensive. Concurrently, studies of RNA editing sites have confirmed that the majority are located in non-coding regions of RNA, and a significant factor contributing to sequencing errors is the presence of RNA modifications, such as methylation [10, 21, 150]. For this reason, it can be useful to identify a set of “housekeeping” genes whose analysis would be sufficient to determine the overall level of RNA editing. Such a metric could involve calculating the average A-to-I RNA editing level across the most edited genes obtained from the REDIportal database. Currently, the top-20 list includes genes UQCRHL, COPA, RPL32, RPL15, FLNB, RPL24, IGFBP7, RPS23, EEF1A1, AZIN1, RPL7A, FTH1, COG3, RPLP1, NEIL1, ZNF358, GIPC1, RPS9, BLCAP, and FLNA [144].

The increased RNA editing activity commonly observed in human cancers results in hyper-edited Alu regions with a high number of repeats. These regions are represented by low-quality reads in RNA sequencing alignments (e.g., STAR [130]), which can severely skew the overall level of RNA editing. A new metric, the Alu editing index (AEI), allows for reliable comparison of the overall level of RNA editing between samples from different studies [8, 151]. The AEI is based on Alu editing of the A-to-I substitution and defined as the weighted ratio of the number of A-to-G mismatches, shown in the reference genome, to the total number of adenosines (A-to-G mismatches + A-to-A matches) in predefined regions, containing Alu repeats (more than 10 million adenosine sites) [150, 151]. The weights for AEI calculation represent the coverage of analyzed sites. The pipeline for Alu editing index analysis also includes SNP calling with dbSNP and calculation of “control indexes” that account for technical noise when evaluating results [151]. Processing hyper-edited reads and analyzing AEI to compare different samples can be crucial for RNA editing studies. Furthermore, several studies suggest that AEI can serve as a prognostic biomarker for patient survival. For instance, a high level of AEI has been associated with unfavorable survival rates in liver, head and neck, and breast cancers [150]. Moreover, ADAR levels did not show significant results in such survival analyses. In another study, tumors exhibiting increased AEI were likely to show increased ADAR expression [152]. Decreased AEI during treatment serves as an indicator of drug effectiveness in reducing editing, whereas an increase suggests the tumor has adapted by upregulating ADAR expression.

Thus, analyzing ADAR and APOBEC expression patterns alongside RNA and DNA variants, as well as the overall level of Alu-based RNA editing between tumor and normal tissues, and within tumor samples alone, offers a promising approach for understanding tumor development and tailoring type-specific therapies. Among the methods available, those based solely on RNA sequencing data and focusing on a limited number of RNA editing sites are probably the most efficient and least computationally and time-consuming. For a comprehensive assessment of the overall RNA editing level and its impact on genome integrity, calculating the Alu editing index is also an effective approach. Moreover, RNA editing levels may significantly correlate with patient survival, enabling the construction of prognostic models based on these parameters and their combinations.

ADAR- and APOBEC-mediated RNA editing is a critical component of genome, transcriptome and proteome diversification and regulation, influencing multiple cellular processes. These enzymes can naturally modify various types of non-coding and coding RNAs, including introns and UTRs, and less frequently protein-coding mRNA exons, potentially contributing to the development and progression of human diseases, such as tumors. Significant efforts have been directed towards developing computational methods alongside advances in sequencing technologies to detect RNA editing events across millions of editing sites.

This review updates information on the biology of RNA editing, possible editing sites, and its impact on the development of various human diseases. Also, the review underscores the necessity for developing precise bioinformatic tools capable of differentiating between RNA editing events and other nucleotide variants. Future research should focus on the integration of RNA editing data into predictive models of cancer progression, thus offering new avenues for therapeutic intervention of this relatively new dimension of gene expression data.

Conceptualization: AM, AB and MS. Data curation: AM. Formal analysis: AB and MS. Supervision: AB and MS. Writing—original draft: AM. Writing—review and editing: AB and MS. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The analysis of RNA editing in cancer by MS was funded by Russian Science Foundation grant 20-75-10071. The analysis of fundamental aspects of RNA editing by AM was carried out with the financial support of a project “Digital technologies for quantitative medicine solutions” FSMG-2021-0006 (Agreement No. 075-03-2024-117 of January 17, 2024).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.