1 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, 400016 Chongqing, China

Abstract

Sesamin can suppress many cancers, but its effect on nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is unclear. Herein, we set out to pinpoint the possible changes in NPC due to Sesamin.

The biological function of NPC cells exposed to Sesamin/N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC)/3-Methyladenine (3-MA) was detected, followed by evaluation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate staining) and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) (flow cytometry). Proteins pertinent to apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3, cleaved poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1)), cell cycle (Cyclin B1), and autophagy (microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3)-I, LC3-II, Beclin-1, P62) were quantified by Western blot. After the xenografted tumor model in mice was established, the tumor volume and weight were recorded, and Ki-67 and cleaved caspase-3 levels were determined by immunohistochemical analysis.

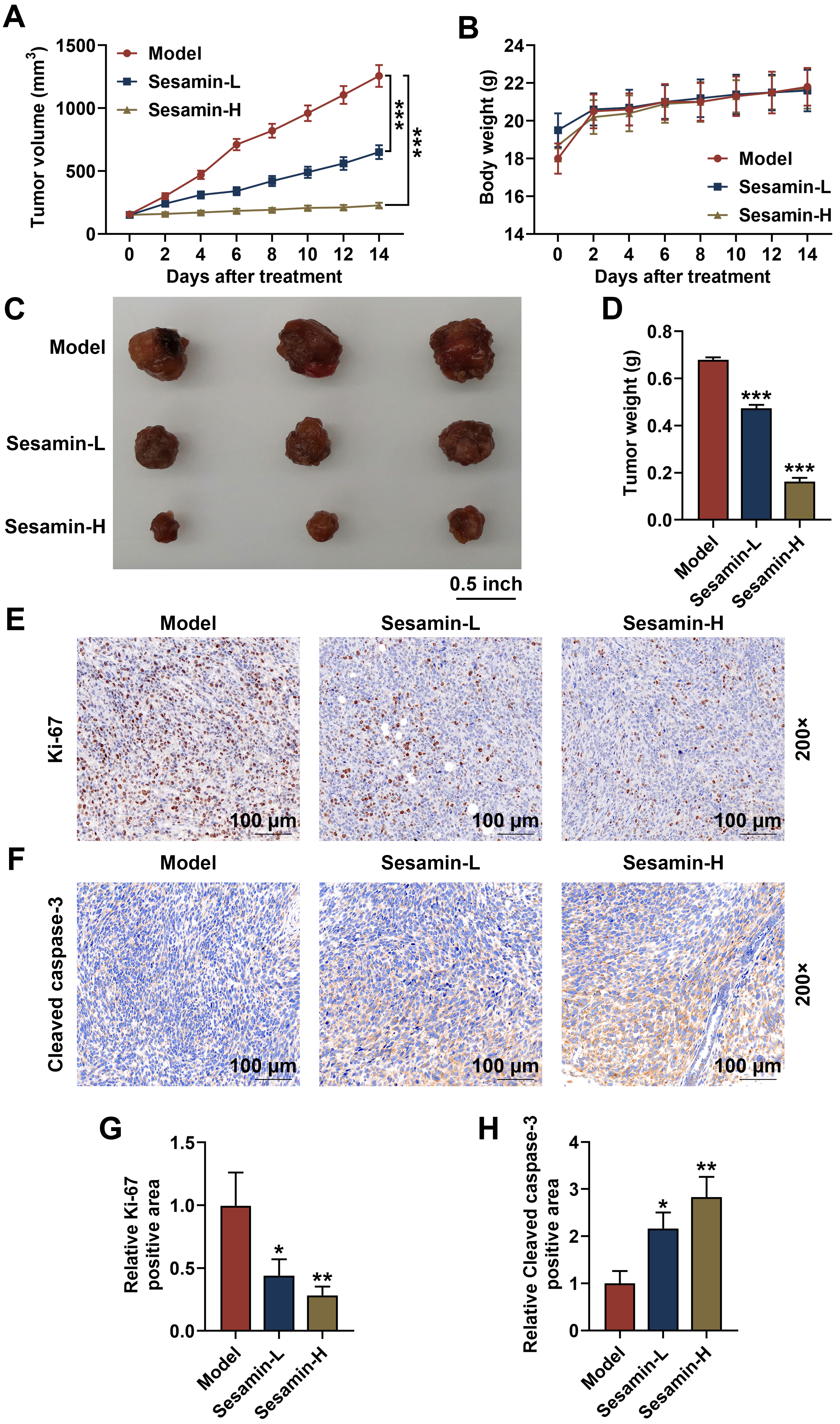

Sesamin inhibited viability, proliferation, cell cycle progression and migration, induced apoptosis, increased ROS production, and decreased MMP in NPC cells. Sesamin elevated cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3, cleaved PARP1/PARP1, and Beclin-1 expressions as well as LC3-II/LC3-I ratio, while diminishing Cyclin B1 and P62 levels. NAC and 3-MA abrogated Sesamin-induced changes as above in NPC cells. Sesamin inhibited the increase of the xenografted tumor volume and weight, down-regulated Ki-67, and up-regulated cleaved caspase-3 in xenografted tumors.

Sesamin exerts anti-tumor activity in NPC, as demonstrated by attenuated tumor proliferation and xenografted tumor volume and weight, as well as induced apoptosis in tumor tissues, consequent upon the promotion of autophagy and reactive oxygen species production.

Keywords

- nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- sesamin

- autophagy

- reactive oxygen species

- xenografted tumors

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), a malignancy occurring on the epithelium of the nasopharyngeal mucosal lining, is the most prevalent type of cancer in the head and neck regions [1, 2]. Although NPC is relatively uncommon compared with other cancers, with only new cases (129,000) representing 0.7% of all cancer diagnoses, advanced NPC is pertinent to 38%–63% of the overall 5-year survival rate [3, 4]. Conventionally, treatment modalities for NPC encompass radiotherapy, chemotherapy, surgery and targeted therapy, and immunotherapy has gained traction as an additional strategy for advanced NPC in recent years [5]. Despite advancements in clinical treatment methods, 19–29% of patients still experience post-radiotherapy relapse and distant metastasis, which adversely affects survival and life quality, primarily due to radiotherapy resistance [6]. Therefore, the pursuit of innovative and effective pharmaceuticals for NPC treatment is of paramount importance.

Of note, increasing evidence has underscored the significance of natural products in combating various cancer types including NPC because these products are valued for multi-channel, multi-point, multi-effect, minimal side effect properties, and so on [7, 8, 9]. For instance, Dihydroartemisinin, Luteolin, and Cruciferae sulforaphane are anti-NPC candidate drugs [9, 10, 11]. Sesamin, a major active ingredient in Sesame, also exists in some other plants, such as Araliaceae, Rutaceae, and Scrophulariaceae [12]. Given the widespread culinary uses of Sesame, many researchers in East Asia have widely studied its active constituents including Sesamin [13], thus revealing plentiful biological activities of Sesamin such as anti-oxidation, anti-inflammation, and anti-lipogenesis [14, 15, 16]. Furthermore, Sesamin has been greatly reported to possess powerful anti-tumor effects [17]. For example, it has been confirmed to repress proliferation and enhance apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer cells by modulating protein kinase B (AKT)/p53 signaling pathway [18], to suppress breast cancer development via inhibiting programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression [19], and to induce the endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis and activating autophagy in cervical cancer cells [15]. However, whether Sesamin has the same anti-cancer effect on NPC has not been investigated as far as we know. Interestingly, studies showed that activating phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT or p53 signaling pathways can enhance the carcinogenicity or radiosensitivity of NPC [20, 21]. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a possible immune-evasion mechanism pertinent to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated NPC [22]. Moreover, autophagy and apoptosis can be promoted in NPC by inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress [23]. Accordingly, we conjectured that Sesamin may also exhibit growth-inhibiting properties in NPC.

Therefore, in the present study, we cultured NPC cell lines and established a xenografted-NPC-tumor mice model. After treatment of the cells and mice with Sesamin, the effects of Sesamin on cell tumorigenicity and tumor growth were further determined through a series of biological testing methods. Through the current research, we attempted to contribute new theoretical insights into Sesamin’s properties and to provide novel treatment approaches for NPC.

Human immortalized nasopharyngeal epithelial cell line NP69 (BFN60870097, BLUEFBIO, Shanghai, China) and human NPC cell lines including C666-1 (BFN608006727, BLUEFBIO, Shanghai, China) and HK-1 (JNO-H0105, Jennio, Guangzhou, China) were cultured (37 ℃, 5% CO2) in Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) (A4192101, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (16140071, Gibco). The cells used in this study were identified via short tandem repeat (STR) and the test results for mycoplasma were negative.

For the treatment of Sesamin alone, NP69, C666-1, and HK-1 cells were directly cultured (24 h) in Sesamin (10, 20, 50, 100, 200 µmol/L) (C20H18O6, Purity: 99.70%, HY-N0121, MedChemExpress, Shanghai, China) and then collected for other experiments.

Then, HK-1 cells were assigned into 6 groups: Control (24-hour culture in DMEM with 10% FBS); N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) (2-hour culture in 5 mM of NAC (S0077, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and then 24-hour culture in DMEM with 10% FBS); 3-Methyladenine (3-MA) (2-hour culture in 3 mM 3-MA (M9281, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and then 24-hour culture in DMEM with 10% FBS); Sesamin (24-hour culture in 50 µmol/L Sesamin); Sesamin+NAC (2-hour culture in 5 mM of NAC and 24-hour culture in 50 µmol/L Sesamin); and Sesamin+3-MA (2-hour culture in 3 mM of 3-MA and 24-hour culture in 50 µmol/L Sesamin).

Methylthiazolyldiphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay kit (M1020, Solarbio,

Beijing, China) was used in the cell viability detection. After 24-hour treatment

with Sesamin (different concentrations), NP69, C666-1, and HK-1 cells were

incubated in a 96-well with the 90 µL fresh FBS-free medium and 10 µL

MTT solution (4 h), followed by a 10-minute reaction with 110 µL formazan

dissolvent. Finally, the absorbance (490 nm) was obtained by employing an Imark

microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Relative cell viability (%) =

(experimental group OD – blank group OD)/(control group OD – blank group OD)

Transwell assay was conducted in this part. Sesamin-treated C666-1 and HK-1

cells (both 1.5

Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) staining was carried out for ROS

detection. Sesamin/NAC/3-MA-treated C666-1 and HK-1 cells were subjected to

washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) thrice, followed by incubation with

DCFH-DA staining buffer (S0033M, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) (30 min, 37 ℃).

2-(4-Amidinophenyl)-6-indolecarbamidine dihydrochloride (DAPI, Blue, C1002,

Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used to stain nuclei for 5 min. The observation

was completed under a STELLARIS 5 laser confocal microscope (

Evaluation and analyses were accomplished via JC-1 staining and flow cytometry, respectively. Sesamin/NAC/3-MA-treated C666-1 and HK-1 cells were subjected to PBS washing (three times), followed by 20-minute incubation with JC-1 staining buffer (C2006, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) (37 ℃). Finally, cell MMP was dissected using a FACSCaliburTM flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lake, NJ, USA).

Colony formation assays were performed. Sesamin/NAC/3-MA-treated C666-1 and HK-1

cells were washed with PBS three times. Then, the cells (1.0

In this part, propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry were carried out. Sesamin/NAC/3-MA-treated C666-1 and HK-1 cells were washed with PBS three times, followed by 1-hour fixation (75% pre-cooling ethanol, M058838, MREDA, Beijing, China), 25-minute color development (PI buffer, ST511, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and cell cycle distribution dissection (a flow cytometer).

Using Annexin-V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry, cell apoptosis was examined. Following PBS washing thrice, Sesamin/NAC/3-MA-treated C666-1 and HK-1 cells were exposed to Annexin-V-FITC (C1062S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and PI (30 min, darkness). Finally, dissection on cell cycle distribution was completed by utilising a flow cytometer.

Post PBS washing thrice, Sesamin/NAC/3-MA-treated C666-1 and HK-1 cells were

exposed to NP-40 (P0013F, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) (15 min) on ice and

centrifuged (20 min, 14,000

Eighteen female BALB/c nude mice (5–6 weeks old and 20

Then, all mice received injection with 100 µL PBS containing 1

After being photographed and weighed, the tumor tissue underwent fixation (24 h,

paraformaldehyde fixative, P885233, MREDA, Beijing, China), transparentization

(xylene, M056094, MREDA, Beijing, China), and

paraffin embedding (M060593, MREDA, Beijing, China). A total of 4 µm tissue

slices were prepared and dewaxed. Then, the slices were placed in an antigen

repair buffer (M052013, MREDA, Beijing, China) and incubated with Ki-67 (1:500,

ab15580, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or cleaved caspase-3 (1:500, #9661, CST, Boston,

MA, USA) antibodies (overnight, 4 ℃), and reacted (1 h) with rabbit antibody

(ab205718, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). After DBA (SFQ004, 4A Biotech, Beijing, China)

and hematoxylin (M1428, MREDA, Beijing, China) stainings, the slices were

transparentized using xylene and sealed with neutral gum (M051989, MREDA,

Beijing, China). Lastly, the tissue image (

Multi-group comparisons were completed by employing one-way ANOVA. All

statistical analyses were implemented using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad

Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), with the final data described using Mean

Fig. 1A exhibited the chemical structure of Sesamin. The means of how Sesamin

influences the viability of normal NP69 cells (Fig. 1B), as well as NPC C666-1

cells (Fig. 1C) and HK-1 cells (Fig. 1D), were determined. The results showed

that 10/20/50 µmol/L Sesamin did not affect NP69 cell viability (Fig. 1B),

while 100/200 µmol/L Sesamin reduced its viability (p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Sesamin reduced viability and proliferation while enhancing

apoptosis of NPC cells. (A) The chemical structure of Sesamin. (B–D) Viability

of NP69 cells (B), C666-1 cells (C), and HK-1 cells (D) after Sesamin treatment

(MTT assay). (E,F) Proliferation of C666-1 cells (E) and HK-1 cells (F) after

Sesamin treatment (colony formation assay). (G,H) Apoptosis of C666-1 cells (G)

and HK-1 cells (H) after Sesamin treatment (flow cytometry). (*p

As depicted in Fig. 2A,B, the migration rates of both NPC cells C666-1 (Fig. 2A)

and HK-1 (Fig. 2B) were diminished by Sesamin (p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Sesamin inhibited the migration and cell cycle progression of

NPC cells. (A,B) Migration of C666-1 cells (A) and HK-1 cells (B) after Sesamin

treatment (transwell assay). Scale bars, 50 µm. (C,D) Cell cycle

distribution of C666-1 cells (C) and HK-1 cells (D) after Sesamin treatment (flow

cytometry). (*p

The quantification of apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP1)- and cell

cycle (Cyclin B1)-related factors was determined (Fig. 3A–H). The results show

that due to Sesamin treatment, cleaved caspase-3/caspase-3 and cleaved

PARP1/PARP1 levels in C666-1 cells (Fig. 3A–C) and HK-1 cells (Fig. 3E–G) were

up-regulated (p

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Sesamin influenced expressions of factors related to

apoptosis/cell cycle/autophagy in NPC cells. (A–H) Expressions of

apoptosis-related (cleaved caspase-3, caspase-3, cleaved PARP1, and PARP1) and

cell cycle-related (Cyclin B1) factors in C666-1 cells (A–D) and HK-1 cells

(E–H) after Sesamin treatment (Western blot assay). (I–P) Expressions of

autophagy-related factors (LC3-I, LC3-II, Beclin-1, and P62) in C666-1 cells

(I–L) and HK-1 cells (M–P) after Sesamin treatment (Western blot assay).

Next, the ROS level in NPC cells after Sesamin induction was evaluated (Fig. 4A,B) and the results exhibited that the ROS level in the C666-1 cells (Fig. 4A)

and the HK-1 cells (Fig. 4B) was remarkably up-regulated by Sesamin (p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Sesamin increased ROS production. (A,B) The ROS level in C666-1

cells (A) and HK-1 cells (B) after Sesamin treatment

(DCFH-DA staining). Scale bars, 100 µm.

(*p

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Sesamin decreased MMP of NPC cells. (A,B) The mitochondrial

membrane potential of C666-1 cells (A) and HK-1 cells (B) after Sesamin treatment

(flow cytometry). (***p

To ascertain whether Sesamin influences NPC cells by regulating ROS production

and autophagy, the scavenger of ROS (NAC) and the inhibitor of autophagy (3-MA)

were used to pre-treat the cells before Sesamin treatment. As depicted in Fig. 6A, the ROS production in HK-1 cells was decreased by 3-MA (p

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Inhibitors of ROS and autophagy neutralized the effect of

Sesamin on ROS production, and MMP of the NPC cells. (A) The ROS level in HK-1

cells after being co-treated with Sesamin and NAC or 3-MA (DCFH-DA staining).

Scale bars, 100 µm. (B) Mitochondrial membrane potential of HK-1 cells

after being co-treated with Sesamin and NAC or Sesamin and 3-MA (flow cytometry).

(*p

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Inhibitors of ROS and autophagy neutralized the effect of

Sesamin on proliferation, and cell cycle progression of the NPC cells. (A)

Proliferation of HK-1 cells after being co-treated with Sesamin and NAC or 3-MA

(colony formation assay). (B) Cell cycle distribution of HK-1 cells after being

co-treated with Sesamin and NAC or 3-MA (flow cytometry). (*p

In addition, HK-1 cell apoptosis was determined (Fig. 8A) and the results showed

that Sesamin-induced changes in apoptosis were counteracted by NAC and 3-MA

(p

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Inhibitors of ROS and autophagy abrogated Sesamin-triggered

changes in the apoptosis and expressions of apoptosis/autophagy-related factors

in NPC cells. (A) HK-1 cell apoptosis after being co-treated with Sesamin and

NAC or 3-MA (flow cytometry). (B–E) The expressions of apoptosis- (cleaved

caspase-3/caspase-3 and cleaved PARP1/PARP1) and cell cycle (Cycle B1)-related

factors in HK-1 cells after being co-treated with Sesamin and NAC or 3-MA

(Western blot assays). (F–I) The expressions of autophagy-related factors

(LC3-I, LC3-II, Beclin-1, and P62) in HK-1 cells after being co-treated with

Sesamin and NAC or 3-MA (Western blot assay).

Finally, to further verify the influence of Sesamin in vivo, the

xenografted tumor mice model was established and treated with Sesamin. As shown

in Fig. 9A, Sesamin treatment significantly inhibited the increases in tumor

volume (p

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Sesamin down-regulated Ki-67 and up-regulated cleaved caspase-3

in NPC tumors, as well as inhibited the growth of NPC in vivo. (A)

Tumor volume subcutaneously growing in nude mice on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12,

or 14, n = 6. (B) The body weight of the mice on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, or

14 when tumor subcutaneously grown in nude mice, n = 6. (C) Pictures of

xenografted tumor subcutaneously grown in nude mice for 14 days, n = 3. (D) Tumor

weight after the tumor subcutaneously grown in nude mice for 14 days, n = 3.

(E,G) Ki-67 expression in the tumor tissues (immunohistochemical analysis). Scale

bars, 100 µm. (F,H) Cleaved caspase-3 expression in the tumor tissues

(immunohistochemical analysis). (*p

The powerful anti-tumor effect of Sesamin has been previously reported [17] in many cancers except NPC. Herein, for the first time, we discovered that Sesamin inhibited the proliferation, migration, and cell cycle progression, while inducing apoptosis of NPC cells, which indicated that Sesamin might have an anti-tumor effect on NPC. Considering that the basis of cancer development is enhanced proliferation and suppressed apoptosis of cancer cells [24], and that proliferation is contingent upon cell cycle distribution of cancer cells [24, 25, 26, 27], we conducted an assessment on cell cycle-associated factors. The S phase is a stage where DNA and histone synthesis occur before cell division [28]. Besides, Cyclin B1, one of the cell cycle regulation factors, starts to be expressed in the S phase [29, 30]. A previous study showed Sesamin stimulated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells [31]. Our results proved that Sesamin diminished Cyclin B1 level, and dampened the cell cycle progression of NPC cells.

Besides, apoptosis is closely associated with DNA damage. PARP, regarded as a DNA damage receptor, can be activated (cleaved PARP) to be involved in the repair of cell injury, especially during stress conditions including cell apoptosis [32, 33]. PARP1 is a substrate of caspase-3 [34]. Once activated (cleaved caspase-3), caspase-3 is the final executor of cell apoptosis [24]. Therefore, cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP levels can affect the apoptosis level in cells. Herein, Sesamin up-regulated cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP in NPC cells. Moreover, apoptosis is mainly mediated by the mitochondrial pathway (Bcl-2 family/caspase 9/caspase 3), which is characterized by the continuous activation of caspase [35]. Apoptosis enhances mitochondrial membrane permeability and attenuates the transmembrane MMP [36]. In the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway, the reduction of MMP promotes the release of cytochrome c (Cyt c) from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm, activating caspase-3 [37]. Furthermore, ROS is essential in tumorigenesis, and ROS accumulation directly causes DNA damage [38, 39, 40]. Therefore, ROS both participates in apoptosis and autophagy. Excessive ROS also induces cell cycle arrest [38]. Interestingly, ROS production was boosted by Sesamin treatment. Given that ROS is generated in mitochondria, which are also the main targets of ROS, ROS production leads to mitochondrial damage manifested by a decrease in cell MMP [41]. In this study, we found that Sesamin reduced the MMP of NPC cells and promoted ROS production in NPC cells.

Although apoptosis and autophagy are both programmed cell death mechanisms, autophagy also can serve as an alternative mechanism for cell death especially when apoptosis is defective [15, 38]. Given the current challenges in cancer treatment and possible cancer resistance to apoptosis, targeting autophagy presents a promising strategy to induce cancer cell death [15]. Sesamin may alleviate asthma airway inflammation by inhibiting mitophagy and mitochondrial apoptosis [42]. Therefore, we hypothesized that Sesamin may impact NPC cells by promoting autophagy. To investigate whether Sesamin can promote autophagy in NPC cells, the autophagy-related factors were evaluated. LC3 is a widely accepted autophagy marker due to its ability to transform into LC3-II during autophagy, and Beclin-1 is the upstream factor essential for autophagosome formation [38]. Herein, LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and Beclin-1 level were both elevated by Sesamin treatment, hinting that Sesamin promoted autophagy in NPC cells.

To further confirm our hypothesis, we co-treated NPC cells with NAC/3-MA alongside Sesamin. To our delight, the data revealed the impacts of Sesamin on the proliferation, cell cycle distribution, apoptosis, ROS production, MMP, and expressions of related factors in NPC cells were weakened by NAC/3-MA, which supported our hypothesis. In addition, in the xenografted tumor mice, we further discovered that Sesamin inhibited the growth of NPC tumors and promoted apoptosis of NPC tumor cells, which further verified the anti-tumor effect of Sesamin on NPC in vivo. However, the ROS level was not measured in animal experiments, which will be performed in the future. Moreover, different NPC cells have different characteristics and may have different sensitivity to Sesamin. Therefore, it is necessary to further explore the basic principle governing different cell sensitivity to Sesamin in the future.

In a word, this research discovers that Sesamin inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of NPC both in vitro and in vivo through stimulating autophagy and ROS production. Our findings provide novel theoretical guidance for the study of Sesamin and may pave the way for innovative therapeutic strategies against NPC.

The analyzed data sets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Substantial contributions to conception and design: DQA. Data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation: XYJ, YCY. Drafting the article or critically revising it for important intellectual content: All authtors. Final approval of the version to be published: All authors. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: All authors.

All experiments involved in animals in this study were ratified by the Committee of Zhejiang Baiyue Biotech Co., Ltd. for Experimental Animals Welfare (No. ZJBYLA-IACUC-20231201). The experimental guidelines we follow for animal experiments are: Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee ethical guidelines.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81970864); the Chongqing Middle and Youth Medical High-end Talent Studio Project (grant no. Yu Wei (2018) No 2) and the Chongqing Talents Project (grant no. Yu Wei (2021)).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.