1 Research Laboratory “Medical Digital Images Based on the Basic Model”, Department of Bioengineering, Faculty of Bioengineering and Veterinary Medicine, Don State Technical University, 344000 Rostov-on-Don, Russia

2 Wizntech LLC, 344002 Rostov-on-Don, Russia

3 Academy of Biology and Biotechnology, Southern Federal University, 344090 Rostov-on-Don, Russia

Abstract

Cultured meat holds significant potential as a pivotal solution for producing safe, sustainable, and high-quality protein to meet the growing demands of the global population. However, scaling this technology requires innovative bioengineering approaches integrated with software methods to assess the growth of cell cultures. This study aims to develop a technology for 3D printing a hybrid meat product and subsequently design a finely tuned You Only Look Once (YOLO) model for detecting and counting lipoblasts, fibroblasts, and myogenic cells.

Cultures of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MMSCs) and fibroblasts were obtained from the domestic rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus domesticus. Standard protocols were employed to induce adipogenic and myogenic differentiation from MMSCs. Fibroblasts were isolated from skin biopsy samples. The 3D printing process utilized bioinks. The engineering approach involved the development of a unique print head integrated into a 3D printer. Confocal and transmission electron microscopy of the cells within the construct was performed. A dataset of digital images of lipoblasts, myogenic cells, and fibroblasts was created. Four models based on the YOLOv8-seg architecture were trained on annotated images, implemented in the Telegram bot.

Stable cultures of lipoblasts, myogenic cells, and fibroblasts were obtained. 3D-printed tissue constructs composed of rabbit cells, sodium alginate, and sunflower protein were successfully fabricated. A unique print head for a 3D printer was assembled. Confocal microscopy confirmed cell viability within the tissue construct. Ultrastructural analysis revealed dense intercellular contacts and high metabolic activity. The resulting product replicated the organoleptic and structural properties of natural meat. In the IT segment, the single-class model trained on lipoblasts achieved metrics of recall 85%, precision 77%, and mean Average Precision at IoU threshold 0.50 (mAP50) 79%, which improved in the multiclass model to recall 92%, precision 92%, and mAP50 81%. The IT solution was implemented in a Telegram bot capable of detecting and counting different cell types.

A 3D tissue construct was achieved. Detailed microscopic analysis demonstrated cell viability and high metabolic activity within the polymerized alginate hydrogel. The engineered tissue product presents a potential alternative to natural meat. Additionally, the trained neural network models, implemented in a Telegram bot, proved effective in monitoring culture growth and identifying cell types in digital images across three cell cultures. As a result, we developed four YOLOv8 models and demonstrated that the multiclass model outperforms the single-class model. However, all models exhibited reduced accuracy in high-density cultures, where overlapping cells led to undercounting.

Keywords

- cultured meat

- lipoblasts

- myogenic cells

- fibroblasts

- 3D-printing

- YOLOv8-seg

- Telegram

- cell counting

Modern challenges to food security demand innovative approaches to food production. Currently, many countries face an acute shortage of protein-rich meat products. Active research is being conducted on producing artificial meat using in vitro cell cultures [1]. These innovative methods hold the potential to create high-quality meat while addressing ethical concerns [2]. In addition, artificial meat is classified as an environmentally friendly product, with minimized antibiotic content compared to conventionally produced meat [3, 4].

The cultivation of artificial meat involves complex biotechnological processes, such as growing cells in specialized bioreactors, ensuring their viability, and stimulating their growth to form meat-like structures [5]. Mesenchymal stem cells play a pivotal role in this process due to their high proliferative capacity and ability to differentiate into myoblasts and subsequently muscle fibers. However, optimizing cell culture conditions and scaling up production are critical scientific and technological challenges [6].

One of the main issues with cultured meat is its current form, typically ground meat used in processed foods with high fat, salt, and sugar content. This reduces the appeal of such products from a healthy eating perspective, especially given the less pronounced flavor profile of cultured meat [7]. Incorporating plant proteins can enhance the nutritional value of these products. Plant proteins are an affordable nutrient source and can significantly reduce the cost of hybrid meat products by combining cultured meat with plant-based components [8]. Technologies such as 3D printing, widely applied in various fields including tissue engineering, enable the creation of intricate structures with high precision. In the food industry, the integration of 3D bioprinting and food printing opens new opportunities to produce meat products with textures closer to natural meat, reducing sensory differences between cultured ground meat, plant protein, and traditional meat [9, 10, 11]. The production of cultivated meat using this technology is considered a promising solution, enabling the creation of high-quality products with adjustable composition, making them healthier and safer for consumption. Furthermore, 3D bioprinting elevates the production of cultivated meat to a new level by scaling the technology without raising ethical or environmental concerns [12].

The fundamental principle of 3D bioprinting for cultivated meat lies in the preparation of bioinks, which consist of cellular components and additional materials. These bioinks are used in bioprinters to form the structure of meat layer by layer, mimicking muscle fibers, adipose tissue, and connective elements. Typically, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and fibroblasts, obtained from animal donors, are cultured to achieve the required cellular mass for 3D bioprinting. MSCs are differentiated into myoblasts and adipocytes, which are subsequently cultivated in bioreactors and incorporated into the bioinks [13].

Additionally, biocompatible materials such as hydrogels are used to provide the necessary support for cell growth and tissue formation. For instance, sodium alginate is used to stabilize the hydrogel through a polymerization mechanism in the presence of calcium ions. This process enhances the mechanical strength of the construct, creating favorable conditions for long-term cell cultivation and maintaining their functionality [14, 15, 16]. Furthermore, in our study, we utilized sunflower protein concentrate, which underwent preliminary cytotoxicity testing and provided texture and density similar to that of natural meat.

Currently, several companies worldwide are actively advancing this technology. For instance, Aleph Farms has developed the steak printed using a 3D bioprinter, replicating the texture and flavor of traditional meat [17, 18]. In turn, MeaTech 3D is actively developing affordable and environmentally sustainable methods for the mass production of cultured meat, relying on 3D bioprinting technologies [19].

In addition to biotechnological challenges in the development and production of artificial meat, scientific hurdles remain regarding the monitoring of cell survival in cultures. This step is crucial for optimizing cultivation conditions and achieving high-quality outcomes [20, 21, 22]. The implementation of deep learning algorithms for cell identification and counting is particularly relevant [23]. Optimizing these algorithms is a critical task, especially for cell cultures with challenges such as low contrast and unclear boundaries in visualization [24]. There is no doubt that the advancement of these technologies will improve precision and efficiency in the field of tissue engineering.

However, extrapolating these technologies to mass production is associated with several challenges, particularly in assessing the viability of cell cultures. For instance, manual cell counting is often used, a method that is highly labor-intensive in terms of time and the expertise required. The routine nature of repetitive tasks leads to human fatigue and a loss of concentration, resulting in inaccuracies or even gross errors that compromise the reliability of the results. Additionally, physical detachment of cells from growth surfaces is often necessary, which adversely affects their viability. Collectively, these factors contribute to inaccuracies and distortions in data reliability [25, 26].

Existing software packages, such as CellProfiler, are widely used for analyzing biological images. However, their application to the detection and quantification of cells with complex morphologies and indistinct boundaries presents a significant challenge due to pixel-level segmentation and user-defined thresholding [27]. Other semi-automated and fully automated [28] open-source systems have also shown limited performance, failing to significantly improve outcomes in this area. Automated counters work well with high-contrast images, such as blood cells, but their effectiveness decreases substantially when dealing with low-contrast images typical of cultured meat cells [29, 30, 31, 32].

Furthermore, many programs for analyzing biological cell images have complex interfaces with numerous modules, where precise configuration directly correlates with the accuracy of results. Not all users possess the necessary expertise to address these challenges, often reverting to traditional methods or misinterpreting data due to improper processing.

A potential solution to these problems lies in YOLO (You Only Look Once)-based models, which transform detection processes into regression tasks rather than complex step-by-step image analysis. This family of deep learning models processes the entire image in a single pass, predicting object coordinates and classes simultaneously, thus significantly improving efficiency and accuracy while reducing the likelihood of errors [33, 34]. Many YOLO-based models have been applied successfully in medical applications [35, 36], and YOLOv8, with its advanced algorithms, excels in detecting small objects in low-contrast images, such as cells and intricate structures [37, 38].

Earlier versions, such as YOLOv4, primarily targeted general object detection across various imaging conditions [39]. However, their performance was limited for small biological objects with low contrast and complex structures, which are particularly characteristic of cultured meat cells. YOLOv8 overcomes these challenges with advanced boundary prediction algorithms and improved weight management, enabling efficient processing of cell culture images where object density and heterogeneity complicate segmentation. Furthermore, YOLOv8 has been benchmarked against other state-of-the-art methods like faster region-based convolutional neural network (R-CNN), a popular model for object detection. The results demonstrated that YOLOv8 provides superior processing speed and accuracy, particularly for detecting small or overlapping structures [40].

In our previous studies, we accumulated extensive experience in molecular biology and bioengineering [41, 42, 43] and our research team has conducted studies in image analysis using artificial neural networks [44]. We have effectively applied this expertise in the present study. In this comprehensive research project, we developed a novel bioengineering method for producing artificial meat using rabbit lipoblasts, myogenic cells, and fibroblastcells, sodium alginate, and sunflower protein. We successfully utilized 3D bioprinting with bioink composed of hydrogel and donor animal cells, subsequently cultivating the construct in a nutrient medium. This process yielded a structured artificial meat product, which underwent morphological analysis using confocal laser scanning microscopy and transmission electron microscopy.

We also created a proprietary dataset of digital images of lipoblasts, fibroblasts, and myogenic cells. These images were annotated and used to train YOLOv8 models in both single-class and multi-class configurations. The study includes a comparative analysis of the performance metrics of these models, such as precision, recall, and F1 scores, to evaluate their suitability for different use cases. Furthermore, we implemented the YOLOv8-seg model within a user-friendly Telegram bot interface, enabling its use in scientific and industrial applications for assessing the viability of cultured artificial meat cells. This comprehensive study addresses critical challenges in tissue engineering. The findings from this research could facilitate the development of scalable and efficient workflows for monitoring cell cultures in both scientific and industrial contexts.

We used tissues from a donor animal. An adult male rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus domesticus of the Soviet chinchilla breed served as a donor animal. For the isolation of MMSCs, fragments of adipose tissue weighing 2 grams were obtained from the large omentum by laparoscopic biopsy; for the isolation of fibroblasts, biopsy specimens of the abdominal skin were obtained. All cell lines were validated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma.

Rabbit was chosen as a donor in this study because this animal is equally successful in meat farming and as a model animal in scientific research. The use of biopsy allowed the life of the donor animal to be preserved, which is one of the most important principles of the cultured meat concept.

All surgical operations are performed under anesthesia. We used anesthesia for the rabbit following this protocol: intramuscular injection of a mixture of Xyla (0.2 mL/kg, 2% xylazine hydrochloride solution; manufactured by Interchemie Werken “de Adelaar” BV, Venray, Netherlands) and Zoletil (15 mg/kg, a mixture of tiletamine hydrochloride and zolazepam hydrochloride, Virbac, Carros, France). The anesthesia was verified by the absence of response to pain stimuli (paw pinch) and suppression of the corneal reflex.

The animals were kept in standard cages with free access to food and water under standard conditions: 12 light/12 dark cycle, temperature 22–25 °C, air exchange rate of 18 changes per hour. International, national and/or institutional recommendations for the care and use of animals were followed. The studies were carried out in accordance with the requirements of the Council Directive of the European Communities 86/609/EEC on the use of animals for experimental research (November 24, 1986), the “Rules of Laboratory Practice in the Russian Federation” (Order No. 708n of August 23, 2010) and the organization of procedures for working with laboratory animals (GOST 33215–2014) and Protocol No. 2, approved by the Bioethics Commission of the Don State Technical University on February 17, 2020.

MMSCs were isolated from a fragment of adipose tissue of the greater omentum. All stages of cell isolation were performed under sterile conditions in a biological safety box. The cell fraction was obtained according to the protocol proposed by Bunnell et al. [45], which, in brief, included incubation of the biopsy specimen in 0.2% collagenase solution from crab hepatopancreas (Biolot LLC, St. Petersburg, Russia) in DPBS (Biolot LLC, St. Petersburg, Russia) for 60 minutes at 37 °C with constant shaking, filtration of the obtained suspension through a cell sieve and cell sedimentation by centrifugation. The obtained cell mass was introduced into culture vials with DMEM/F12 medium (Biolot LLC, Russia) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biolot LLC, Russia) and 1 ng/mL recombinant basic human fibroblast growth factor (FGF2, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After 48 hours, the medium was changed to remove unattached cells. The resulting cell culture was maintained for five passages. Antibiotics and antimycotics were not used during cell culture hereafter. Cell disaggregation during passages was performed using 0.25% Trypsin-Versen 1:1 solution (Biolot LLC, Russia).

For induction of adipogenic differentiation we used DMEM medium with high glucose content and stable L-glutamine (Biolot Ltd., Russia), 10% fetal bovine serum (Biolot Ltd, Russia) 0.1 µmol dexamethasone (D4902, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 0.45 µmol isobutylmethylxanthine (I5879 Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 170 nmol insulin (I5500 Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 0.2 µmol indomethacin (I7378, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). On the 10th day of culturing, the medium was replaced with complete DMEM medium, which was used in the following steps. As a differentiation control, the MMSC cell culture was cultured in complete DMEM medium without inducers. Lipid droplets detected by microscopy in cell cytoplasm were accepted as a specific marker of differentiation [46].

DMEM medium with high glucose content and stable L-glutamine (Biolot LLC, Russia) was used for induction of myogenic differentiation, 10% fetal bovine serum (Biolot LLC, Russia) 10 mM 5-azacytidine (Sisco Research Laboratories, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India), 50 µmol hydrocortisone (H6909 Sigma-Aldrich, USA) [47]. On the 15th day of culturing, the medium was replaced with complete DMEM medium, which was used in the following steps. As a differentiation control, the MMSC cell culture was cultured in complete DMEM medium without inducers. Cell fusion with the formation of multinucleated myotubes detected by microscopy was taken as a specific marker of differentiation [25].

Fibroblasts were isolated from skin biopsy specimens according to the protocol proposed by Abade dos Santos et al. [48]. All cell isolation steps were performed under sterile conditions in a biosafety box. Tissue fragments were washed five times in DMEM medium with antibiotic and antimycotic solution (200 U/mL penicillin, 200 µg/mL streptomycin, 0.5 µg/mL amphotericin B and 50 µg/mL gentamicin) under vigorous shaking with medium change every 5 minutes to prevent microbial contamination. Tissue fragments were sterilely cut with scissors and placed in trypsin dissociation solution preheated to 37 °C and incubated at 37 °C for 10 minutes, after which the solution was centrifuged at 150 g for 10 minutes. The settled cells were suspended in DMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotic and antimycotic solution: 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, 0.5 µg/mL amphotericin B (Gibco, New York, NY, USA) and 25 µg/mL gentamicin (Biolot LLC, Russia), transferred to culture vials and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 4 hours, after which the vials were washed and a new portion of medium was added. After 2 hours, the washing procedure was repeated and the medium was changed. Subculturing was carried out after reaching 90% cell layer density, and antibiotics and antimycotics were not used in the following passages.

The cell isolation and differentiation protocols used allowed us to obtain stable cell cultures that were subcultured for 25 passages for fibroblasts and lipoblasts and 12 passages for myogenic cells.

In the biotechnology of creating bioinks for 3D printing, a mixture based on sodium alginate and sunflower protein concentrate was used. The dry sunflower protein concentrate (SPC), containing 840 g/kg of protein (Kjeldahl method), employed in this study was supplied by LLC “MEZ YUG RUSI” (Rostov-on-Don, Russia).

All components were sterilized under a UV lamp in a specialized biosafety cabinet for 40 minutes prior to use to prevent potential microbial contamination. Sodium alginate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a concentration of 30 mg/mL was dissolved in Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline (DPBS) on a rotary shaker at room temperature for 1 hour to ensure complete dissolution and homogeneity of the solution. The next step involved incorporating the sunflower protein concentrate, maintaining a protein-to-alginate mass ratio of 3:1 based on the dry weight of the substances. The resulting mixture was thoroughly mixed until a uniform paste-like consistency was achieved. To ensure even distribution of the components, the mixture was allowed to rest at room temperature for 2 hours. After preparing the paste-like hydrogel, 3 mL of the mixture was transferred into a sterile 5-mL syringe, which was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 3 minutes to remove air bubbles, a crucial step for ensuring the quality of the subsequent bioprinting process.

Immediately before printing, the hydrogel was enriched with cells. Fibroblasts,

adipocytes, and myosatellite cells were mixed in a 1:1:1 ratio and pelleted via

centrifugation. The pelleted cells were resuspended in the hydrogel at a

concentration of 2

For 3D bioprinting, we designed and constructed a unique print head equipped

with a hydraulic drive in the form of a peristaltic pump and a stepper motor.

This drive system synchronized the extrusion speed of the material with the

motion of the 3D printer’s actuators and allowed for reverse extrusion at the end

of each layer, improving print quality. The Slic3r software, included in the

Repitier Host 3D printer control package (Hot-world GmbH & Co, Willich, North

Rhine-Westphalia, Germany), was used to prepare the model with the following

parameters: object dimensions – 30

Printing was performed in a laminar flow environment within a biosafety cabinet at room temperature. The material was deposited in 60-mm Petri dishes using air as the medium for structure formation. After printing, the constructs were transferred to a CaCl2 solution (100 mg/mL) and incubated for 10 minutes to crosslink the alginate component. The crosslinked structures were then placed in Petri dishes with DMEM culture medium and incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 72 hours.

Sytox Green Stain (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), a highly sensitive fluorescent indicator for cell nuclei, was used to analyze tissue constructs by confocal laser scanning microscopy. The working solution of the dye was prepared in a 1:1000 dilution based on sterile phosphate buffer (PBS). Fragments of tissue constructs were immersed in the prepared solution and incubated for 20–30 minutes at room temperature under dark conditions, which ensured uniform staining of cell nuclei containing the damaged membrane.

After incubation, the samples were thoroughly washed in several changes of PBS to remove excess dye and minimize background signal. Then the constructs were placed in a medium to prevent signal photobleaching (Abberior, Göttingen, Lower Saxony, Germany), which protects fluorescent molecules from photodegradation during the study. This is especially important for long-term visualization of highly detailed structures. The samples were covered with a cover glass to prevent drying and improve optical properties during microscopy.

The samples were examined using an inverted confocal laser scanning microscope Abberior Facility Line (Abberior Instruments GmbH, Göttingen, Lower Saxony, Germany), which allows for detailed analysis of cellular and tissue structures with high spatial resolution. To visualize the 3D object, the object was scanned along the Z axis with a step of 200 nm with a pixel size of 40 nm. The 3D model was constructed using the ImageJ program (version 1.54j, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Tissue construct fragments were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Aurion, Eugene, OR, USA) to preserve their structure. After that, the samples were washed in PBS to remove excess fixative and subjected to additional post-fixation in 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) in phosphate buffer for 1.5 hours.

To prepare for embedding in epoxy resin, the samples underwent a dehydration stage: they were successively treated with alcohols of increasing concentration, bringing them to absolute ethanol. Then, three stages of propylene oxide treatment were used for intermediate infiltration, after which the samples were embedded in Epon-812-based epoxy resin to create a stable matrix. Semi-thin and ultra-thin sections were prepared using an EM UC 7 ultramicrotome (Leica, Wetzlar, Hesse, Germany) and an Ultra 45° diamond knife (Diatome, Biel/Bienne, Canton of Bern, Switzerland).

Ultra-thin sections were contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate solutions to enhance the detail of intracellular structures. They were then analyzed using a JEM-1011 transmission electron microscope (Jeol, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV, which allowed high-resolution images to be obtained.

Semi-thin and ultra-thin sections were prepared using an EM UC7 ultramicrotome (Leica, Germany) and an Ultra 45° diamond knife (Diatome, Switzerland), ensuring high-precision sectioning with minimal artifacts. Semi-thin sections, 0.5–1 µm thick, were stained with a 1% aqueous solution of methylene blue to enhance contrast and visualize the structural elements of the tissues. After staining, the sections were carefully rinsed with distilled water to remove excess dye and air-dried.

The examination of semi-thin sections was performed using a modern light-optical microscope, Leica DM6000 B (Leica Microsystems, Germany), equipped with a high-precision optical system and a digital camera, enabling high-resolution image documentation. The use of this equipment provided a detailed study of morphological changes in tissues, including the analysis of cellular and extracellular structures.

In this study, we analyzed cells that typically grow as a monolayer within culture flasks. One of the primary challenges of visualizing such cell cultures is their low contrast and reduced natural coloration due to the absence of biological fluids. Unlike fluorescent microscopy, where cell boundaries and intracellular structures are well-defined through the use of various stains, images of cultivated meat cells pose significant difficulties for human operators and software-based methods for analyzing digital images of biological structures, including neural network algorithms.

Cell counting was performed directly in the culture flask, which allowed for

maintaining sterility and avoiding unnecessary manipulations that could

negatively affect cell viability. This approach minimizes the risk of

contamination, saves time, and reduces cell material loss, ensuring more accurate

results. Digital images of monolayer cells in culture flasks were captured using

an inverted optical microscope (Leica DM IRB) equipped with a digital CCD camera

(5 MP) via the ToupView software (version 4.11, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China) at

The resulting dataset included three types of cell cultures: myogenic cells, fibroblasts, and lipoblasts. It represented a heterogeneous collection of digital images characterized by variability in image quality, morphological features, and cell density. The visualized cells exhibited low contrast, indistinct boundaries, and complex shapes, making their identification and annotation highly challenging.

For manual object annotation in the microphotographs, the Make Sense service (online image annotation service, developed by Piotr Skalski, Poland) was utilized in polygonal annotation mode, and annotation files were saved in comma-separated values (CSV) format (Fig. 1a–c). For additional manual counting of images without annotation, the operator employed the ImageJ application [49].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Cell markings on micrographs in the Make Sense service and workflow of automated cell detection using deep learning. (a) Lipoblasts. (b) Myogenic cells. (c) Fibroblasts. (d) Workflow of Automated Cell Detection Using Deep Learning. Scale bar 200 µm. The process begins with an original microscopic image, followed by cell annotation to highlight the structures of interest. The annotated image undergoes preprocessing, dividing it into smaller tiles for improved training efficiency. These preprocessed images are then used for model training, enabling the detection model to recognize cell structures. The final result displays the detected cells, marked in red, with a total cell count indicated in inference route.

The created dataset represents a complex and heterogeneous resource for cell analysis, necessitating the development or adaptation of specialized algorithms for automated processing.

The dataset consisted of 1022 bitmap (BMP) images with a size of 2592 pixels by 1944 pixels, which included 56 images containing segmented annotations for all three cell cultures with different cell densities (Supplementary Fig. 2). The total number of annotated cells reached 17,509.

Manual cell annotation in photographs was performed using the web service Make

Sense. Annotated images were saved in COCO JSON format for subsequent analysis.

To enhance model performance, we implemented a preprocessing strategy aimed at

improving image contrast and expanding the dataset. Initially, all images were

converted to grayscale. Each image was then divided into 25 equal parts using a 5

Subsequently, we enhanced the image contrast using the cv2.createCLAHE function with parameters set to clipLimit = 15.0 and tileGridSize = (8, 8). To further improve accuracy, we trained specific models for each cell culture separately and a multi-class model that was trained on all three cultures. Each dataset was divided into three groups: 975 images for training, 250 for validation, and 125 for testing. Since YOLO internally applies augmentations such as resizing, rotation, and mosaic during training, no manual augmentations were applied to the input images (Fig. 1d).

In this study, the YOLOv8-seg model was refined, specifically its small variant (YOLOv8S-seg). This procedure was carried out to address the task of segmenting and counting cells in images of cultured cells.

The model was trained for 100 epochs, as the validation metrics indicated an optimal point within this range. During training, the patience parameter was set to 50 to control early stopping, and model weights were periodically saved every 20 epochs. These training parameters were selected based on prior studies, which demonstrated that smaller batch sizes could unexpectedly correlate with more effective model training. While this might seem counterintuitive, this effect is particularly evident in autoencoder neural network structures, which are often applied to analyze complex biological data typical of medical research [50]. Due to the large dataset for the first cell culture and limited computational resources, the decision was made to adapt the model architecture to the YOLOv8S-seg variant and reduce the batch size to 4.

During inference, the confidence threshold was initially set at the standard value of 0.5. However, this resulted in suboptimal object detection. To enhance the model’s sensitivity and increase the number of detectable cells, the threshold was lowered to 0.05. Additionally, the standard value for the maximum number of detections per image was increased from 300 to 7000 to improve the model’s accuracy when working with high cell density.

The study utilized a wide range of computational and software resources to implement the most efficient processes for data analysis and machine learning. The primary development tool was Python version 3.10.12 (version 3.10.12, Python Software Foundation, Beaverton, OR, USA), chosen for its versatility and high-level syntax, making it an ideal fit for the study’s objectives. For computer vision tasks, the OpenCV-Python library version 4.10.0 (version 4.10.0, OpenCV.org, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used, offering numerous tools for image processing, object detection, and real-time data analysis. NumPy was employed to support complex computations, enabling operations on multidimensional arrays and matrices with high efficiency.

Data exchange between applications was facilitated by the JSON format. Object detection in images was performed using the Ultralytics YOLOv8.2.87 model, based on the YOLO algorithm, which achieved high accuracy and processing speed.

Deep learning models were trained using the PyTorch library version 2.4.1+121 (version 2.4.1+121, Meta AI, Menlo Park, CA, USA), widely used for designing and optimizing neural network architectures. Compatibility between various machine learning frameworks was ensured through the use of the Open Neural Network Exchange (ONNX) format.

A key role in performing computations was played by the NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA). This high-performance graphics card was selected for its ability to handle complex deep learning and artificial intelligence tasks, delivering exceptional performance.

Statistical analysis was performed using single-factor analysis of variance

(ANOVA) with the posteriori Holm-Bonferroni correction criterion. The normality

and uniformity of the variance were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk and

Brown-Forsyth tests, respectively. If the normality or homogeneity of the

variance was not confirmed, the nonparametric Friedman criterion was used. All

the results of the study were analyzed blindly. The differences were considered

significant at p

In this study, the rabbit was selected as the cell donor. This choice was driven by several significant reasons. Rabbits are commonly used in livestock farming for meat production [51, 52], making them an ideal subject for tissue engineering aimed at creating cultured meat products. Additionally, rabbits are widely utilized as model animals in scientific research [53]. For cell harvesting, a biopsy was employed—a minimally invasive procedure that allows for cell extraction without harming the animal. This method preserved the donor’s life, fully aligning with the ethical and ecological principles of cultured meat production.

Following the biopsy, standardized protocols were implemented for cell isolation and differentiation. These protocols included sequential tissue processing steps, such as enzymatic dissociation, cellular fraction isolation, and cultivation in specialized culture media. These methods enabled the establishment of stable cell cultures with high viability and strong proliferation potential.

The obtained cells were categorized into three main lines: lipoblasts, myogenic cells, and fibroblasts (Fig. 2). Each line possesses unique properties essential for producing various components of cultured meat. Fibroblasts provide structural tissue support [54], adipocytes play a key role in flavor development due to their lipid inclusions [55], and myogenic cells form muscle fibers, the primary component of meat products.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Obtained cell lines for growing artificial meat. (a) Lipoblasts. (b) Myogenic cells. (c) Fibroblasts. Scale bar 200 µm. Figure crafted exclusively for this study.

For each cell line, a series of passages was performed to assess their stability and long-term viability. Fibroblasts and lipoblasts were successfully subcultured for 25 passages without significant reductions in proliferative activity or changes in morphological characteristics, demonstrating their resilience to the cultivation process. Myogenic cells also performed well, maintaining stability for 12 passages (Fig. 2).

To create and test the 3D printed tissue constructs, bioinks were used (Fig. 3a) to ensure the stability of the structure and support normal growth of cell populations. One of the key components was sodium alginate, which stabilized the hydrogel through a polymerization mechanism in the presence of calcium ions. This process enhanced the mechanical strength of the construct, creating conditions for long-term cell culture and maintaining their functionality.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The process of preparing a 3D construct. (a) Prepared bioink consisting of organic substances and cells. (b) 3D bioprinting using a universal head with a hydraulic drive in the form of a peristaltic pump and a stepper motor. (c) Printed 3D construct enriched with beetroot juice.

An important component of the bioink was sunflower protein concentrate, which underwent preliminary cytotoxicity testing. Studies confirmed that it had no adverse effects on cell viability and did not disrupt the 3D printing process. Furthermore, due to its unique rheological properties, the concentrate provided the texture and density characteristic of natural meat. This component also facilitated the uniform distribution of cells within the hydrogel, which was critical for forming a tissue-like structure. A unique hydraulic printhead equipped with a peristaltic pump and stepper motor ensured flawless 3D printing (Fig. 3b).

To achieve a visual resemblance to meat, raw beetroot juice was added to the bioink (Fig. 3c). This gave the bioink a rich reddish hue that persisted until thermal processing. Beetroot juice also enriched the bioink with bioactive compounds, enhancing its nutritional value.

The finished tissue constructs were subjected to frying to evaluate their organoleptic properties. The cooking process was as follows: the samples were pan-fried on both sides in a preheated open skillet at 200 °C using refined, deodorized vegetable oil. The frying time was 4 minutes, and no spices or flavorings were added to preserve the product’s natural taste.

During thermal processing, the Maillard reaction was observed, wherein the initially red product gradually turned a golden-brown hue. This effect created the appearance characteristic of traditionally fried meat, enhancing both the visual and flavor likeness.

Volunteers invited for tasting evaluated the taste, aroma, and texture of the cooked product. They described the texture as firm and juicy, with a taste and aroma reminiscent of natural meat. The crispy crust of the fried product was particularly noted for reinforcing the perception of authenticity. These findings confirm that the developed bioink and 3D printing technology have the potential to create alternative meat products with high organoleptic qualities.

To assess the state of the cell nuclei and possible signs of damage, light and fluorescent images of tissue construct fragments were obtained and analyzed. This approach allowed us to study the cell morphology in detail, as well as to identify key features of their organization and structure.

In semi-thin sections stained with methylene blue, the construct fragments after 72 hours consisted of spindle-shaped cells with elongated processes and moderately stained cytoplasm distributed around the nucleus (Fig. 4a,b). It was observed that the cells were arranged in round structures resembling rosettes, forming clusters in which they were in direct contact with one another. These cell aggregates were characterized by a dense arrangement of cells, indicating interaction between them and potential cooperation in the formation of tissue structures. The cell nuclei were oval or round in shape with fine dispersed chromatin (Fig. 4c). In some fragments of the construct, areas were observed that appeared as externally empty lumens, representing gaps between cells without cellular material. In other regions, these lumens were filled with cytoplasmic protrusions from neighboring cells, indicating active interaction between the cells and their attempt to form contacts. These protrusions may play a role in maintaining the structural integrity of the construct, as well as in facilitating the exchange of substances and signals between the cells.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Light and confocal laser microscopy of a tissue

construct sample. (a) Transverse semi-thin section of a fragment stained with

methylene blue (scale bar 300 µm; magnification

When studying the preparations, the formation of nuclear rounded groups was noted, visually resembling spheroids. Such structures are compact rounded conglomerates formed from several dozen cells. Each group of cells was organized in a circle, with nuclei located in the form of a crown around the central part. This can be seen in Fig. 4d,e, where the cell nuclei have a partially ordered organization.

The cell nuclei were oval, slightly elongated, with clear and distinct contours. Uniform distribution of nucleic acids within the nuclei was observed, indicating their stable state. Confocal microscopy did not reveal any signs of fragmentation of cell nuclei, their destruction, or transformation. No structures characteristic of damaged cells, such as fragmentation of nuclear material or abnormal changes in their shape, were detected. All cell nuclei retained normal morphology (Fig. 4c–e), indicating their normal viability.

The data obtained during confocal microscopy emphasize the stability of cellular structures in the tissue construct. Partial organization of cells in the form of compact spheroids with uniform distribution of nucleic acids in the nuclei and a clear structure is also observed, indicating the absence of their damage and a high degree of preservation of the cellular material. These results confirm the success of the tissue cultivation and preparation methods used, and also demonstrate the prospects for further research in this area.

Ultrastructural analysis revealed the presence of cells in the tissue construct characterized by the morphological features of fibroblasts and lipoblasts, exhibiting various shapes, namely spindle-shaped, elongated, and triangular. These cells possessed thin, branched projections predominantly oriented along the axis of the cell body. Additionally, small, irregularly shaped protrusions were observed in the cytoplasm. The cells demonstrated dense packing, closely adhering to one another, which resulted in the formation of regions with direct membrane contact between cell bodies and projections (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Transmission electron microscopy of cells within the construct.

(a) Fibroblast; (b) lipoblast; (c) nucleus; (d) nucleolus; (e) rough endoplasmic

reticulum; (f) lipid droplets, magnification

Fibroblasts and lipoblasts contained oval nuclei with evenly distributed fine-granular chromatin. In most cells, one or two large nucleoli were clearly visible, indicating the high functional activity of fibroblasts. In some cells, nuclei with a curved shape were also observed, likely associated with invagination and protrusion of the nuclear envelope (Fig. 5).

The cytoplasm of fibroblasts was rich in organelles, indicating their high metabolic activity. Numerous oval and round mitochondria, elements of rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, centrioles, and multivesicular bodies were discernible. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) occupied a significant portion of the cytoplasm, consisting of parallel-packed and curved tubules as well as rounded and elongated cisternae with signs of dilation. The membranes of the RER were studded with ribosomes on the cytoplasm-facing side, indicating intense protein synthesis. Free ribosomes, unattached to membranes, were also found in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5).

In contrast to fibroblasts, lipoblasts contained numerous inclusions in the form of round, osmiophilic lipid droplets of various diameters. Particularly notable was the well-developed ER network and highly active Golgi apparatus, suggesting processes of active protein synthesis, including collagen. The ER spaces were organized into stacks of membrane structures and complex tubules. The ER occupied a significant portion of the cytoplasm, consisting of parallel-packed and curved tubules as well as rounded and elongated cisternae with signs of dilation. The membranes of the RER were studded with ribosomes on the cytoplasm-facing side, indicating intense protein synthesis. Free ribosomes, unattached to membranes, were also found in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5).

The dataset included 1022 high-resolution images of cultured cells from three types: lipoblasts, myogenic cells, and fibroblasts. Manual annotations were performed on a subset of these images using Make Sense, providing segmented labels for 17,509 cells across 56 images. These annotations were converted into YOLOv8-seg-compatible formats and used for training, validation, and testing. Additionally, the images were preprocessed to grayscale and enhanced using Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE).

Preprocessing steps were critical for improving detection accuracy, especially on low-contrast images. Without these steps, both models performed poorly at detecting cells, particularly for fibroblast and myogenic cell cultures, where biological object boundaries were not clearly defined. Segmenting the images into smaller parts significantly enhanced model performance, especially in high-density cultures.

Data augmentation, including built-in methods like rotation and resizing, made the model more robust to morphological heterogeneity of the cells, although additional algorithmic solutions, such as synthetic data generation, were not employed. Implementing more advanced augmentation techniques could potentially improve performance in high-density cultures.

It was shown that the number of lipoblasts (Culture 1) calculated by the

operator and neural network models of single and multiclass type significantly

differ (p

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Graph of cell counting by the operator and neural network models

of mono- and multiclass type for lipocyte culture at different time intervals.

Scale bar 200 µm. Single-factor analysis of variance was

performed. M

Our next step was to evaluate the accuracy of the models in calculating the

number of myogenic cells (Culture 2) at different time intervals compared to the

operator. We have demonstrated that the numbers calculated by the operator and

neural network models of mono- and multiclass type differ significantly

(p

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Graph of cell counting by the operator and neural network models

of mono- and multi-class type for myogenic cell culture at different time

intervals. Scale bar 200 µm. M

Next, we evaluated the accuracy of the models in calculating the number of

fibroblasts (Culture 3) at different time intervals compared to the operator. We

have demonstrated that the numbers calculated by the operator and neural network

models of mono- and multiclass type differ significantly (p

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Graph of cell counting by the operator and neural network models

of mono- and multi-class type for fibroblast culture at different time

intervals. Scale bar 200 µm. M

Our study demonstrated significant differences in the accuracy of lipoblasts, myogenic cells and fibroblasts counting between operator assessments and neural network models of both single-class and multiclass types. While the single-class and multiclass models showed high cell-counting accuracy during the early culture periods (days 1 to 3), both experienced a marked decline in performance by days 5 and 6, particularly due to dense cell accumulation and indistinct boundaries that hindered proper identification. The multiclass model generally outperformed the single-class model, especially for lipoblasts and myogenic cells, showing greater consistency with the operator’s control results. However, discrepancies were noted, especially for myogenic cells counts, where the multiclass model showed underestimation on days 3 and 4. For fibroblasts, both models performed well up to the 3rd day, after which the multiclass model exhibited a negative trend, while the single-class model maintained accuracy longer. These findings suggest that while neural network models show promise in cell counting, especially during early culture periods, their accuracy can be limited by training data and cell density, particularly in later stages of culturing.

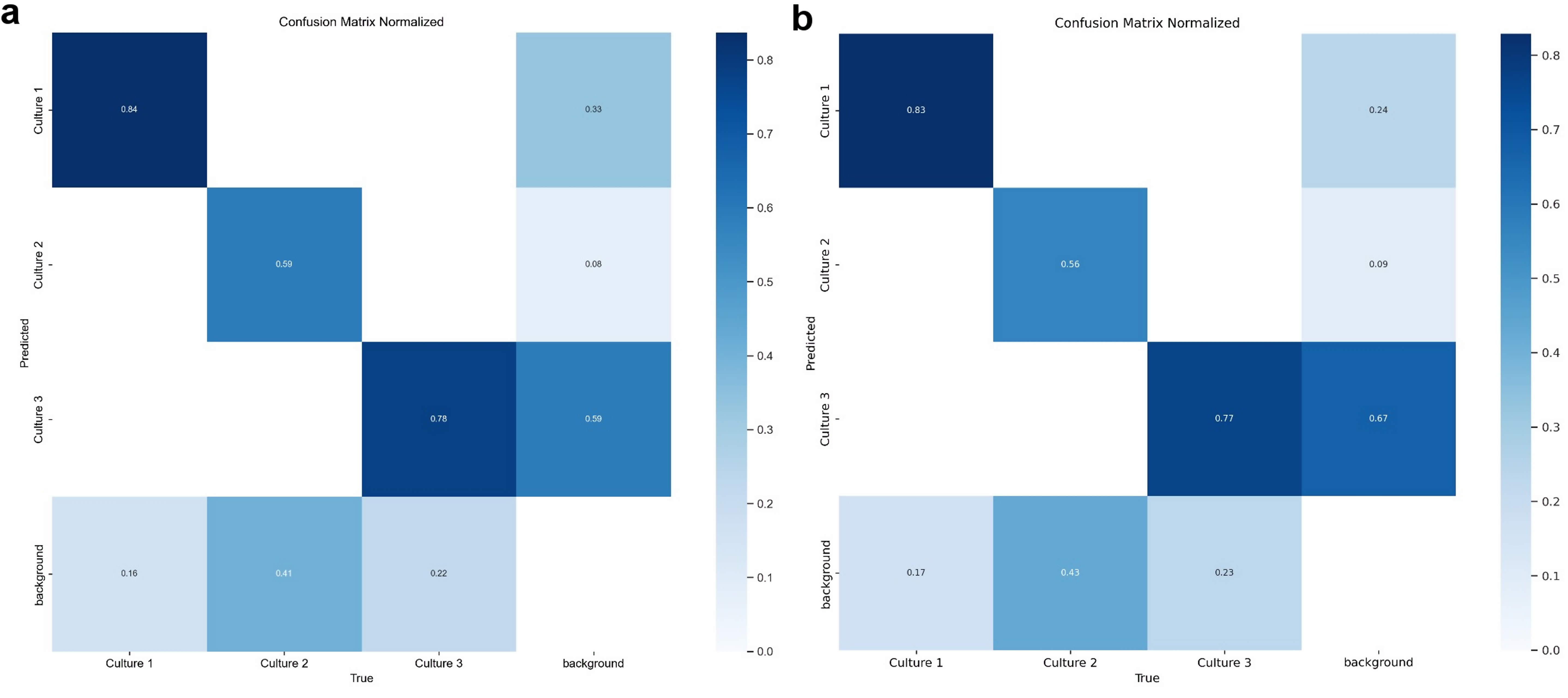

We identified the optimal model, “S,” (Small size) through a rigorous analysis of the confusion matrix, which demonstrated consistently robust performance across all evaluation scenarios. This selection prioritizes an ideal balance between precision and recall, achieving the highest overall efficiency. Additionally, the choice of this model was reinforced by evaluating the mean Average Precision (mAP 0.5) across a range of Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds exceeding 50%, which further confirmed its effectiveness. The IoU is calculated as:

The small (S), medium (M), and large (L) model configurations were thoroughly trained; however, with no significant variations observed in the confusion matrices across these sizes (Fig. 9), the “S” model was deemed optimal due to its faster inference speed and computational efficiency. This model also offers the advantage of accessibility on lower-spec servers, making it more versatile for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Confusion matrix for YOLOv8S (a) and YOLOv8L (b) model trained on 100 epochs for cell culture classification. This matrix illustrates the YOLOv8S model’s performance in distinguishing three cell culture types (Culture 1, Culture 2, and Culture 3) and background. The matrix shows the count of true versus predicted labels, with higher values along the diagonal representing correct classifications. Culture 1 achieved high accuracy, though misclassifications are notable between Culture 1 and Culture 3, as well as Culture 3 and background. The model was trained over 100 epochs to enhance detection accuracy across categories. YOLO, You Only Look Once.

The performance of the YOLOv8S-seg model was evaluated in two configurations: single-class and multiclass models. Single-class models were trained and tested on individual cell cultures, while the multiclass model was trained on three different cultures but limited to recognizing specific cell types.

Performance was assessed for each configuration across three cell cultures. The results are presented in Table 1, which shows the recall, precision, F1 score, and mAP50 metrics for the YOLOv8S-seg model, comparing its performance in single-class and multiclass configurations across biological samples (referred to as “crops”).

| Single-class model | Multiclass model | |||||

| Culture 1 | Culture 2 | Culture 3 | Culture 1 | Culture 2 | Culture 3 | |

| Recall | 0.8500 | 0.5686 | 0.7684 | 0.9187 | 0.5621 | 0.7671 |

| Precision | 0.7733 | 0.7404 | 0.6765 | 0.9169 | 0.6798 | 0.6499 |

| F1 Score | 0.8098 | 0.6433 | 0.7195 | 0.9178 | 0.6154 | 0.7036 |

| mAP 50 | 0.79135 | 0.51382 | 0.68511 | 0.8170 | 0.5820 | 0.7020 |

mAP, mean Average Precision.

For Culture 1, the model demonstrated high performance: recall was 0.8500, meaning 85% of target objects were correctly detected. Precision was 0.7733, indicating that 77% of detected objects were accurate. The F1 score, balancing recall and orecision, was 0.8098, while mAP50 reached 0.79135, reflecting strong object localization capabilities. For Culture 2, the single-class model struggled, achieving a recall of 0.5686, although precision remained acceptable at 0.7404, leading to an F1 score of 0.6433. The mAP50 for Culture 2 was 0.51382, indicating lower localization accuracy. For Culture 3, the model showed satisfactory results: recall was 0.7684, precision was 0.6765, F1 score was 0.7195, and mAP50 was 0.68511, reflecting balanced accuracy in detection and localization.

In the multiclass configuration, the model was trained on all three cultures simultaneously but made predictions for individual cell types. For Culture 1, the multiclass model demonstrated excellent results: recall was 0.9187, precision was 0.9169, F1 score was 0.9178, and mAP50 was 0.8170, showing outstanding performance across all metrics. In Culture 2, the multiclass model achieved comparable results to the single-class model, with recall at 0.5621 and a slight improvement in precision to 0.6798. The F1 score was 0.6154, and mAP50 increased to 0.5820, indicating a modest improvement in localization accuracy. For Culture 3, the model achieved recall of 0.7671, precision of 0.6499, F1 score of 0.7036, and mAP50 of 0.7020, showing consistent performance in both configurations for this culture.

Comparison between single-class (Supplementary Fig. 3) and multiclass models shows that the multiclass configuration outperformed the single-class model in Culture 1, demonstrating significant improvement in all metrics. However, for Culture 2 and Culture 3, the benefits of the multiclass approach were less pronounced, with slight improvements in precision, F1 score, and mAP50. These results indicate that, while the multiclass model shows better generalization, particularly for Culture 1, some cultures may benefit more from specialized single-class models.

The mAP50 metric, used as a simple but effective indicator of model performance, measures the overlap between predicted objects and ground truth annotations. It is particularly useful for comparing models in object detection tasks, where precise overlap is crucial. For each image, mAP50 was calculated to quantify detection accuracy.

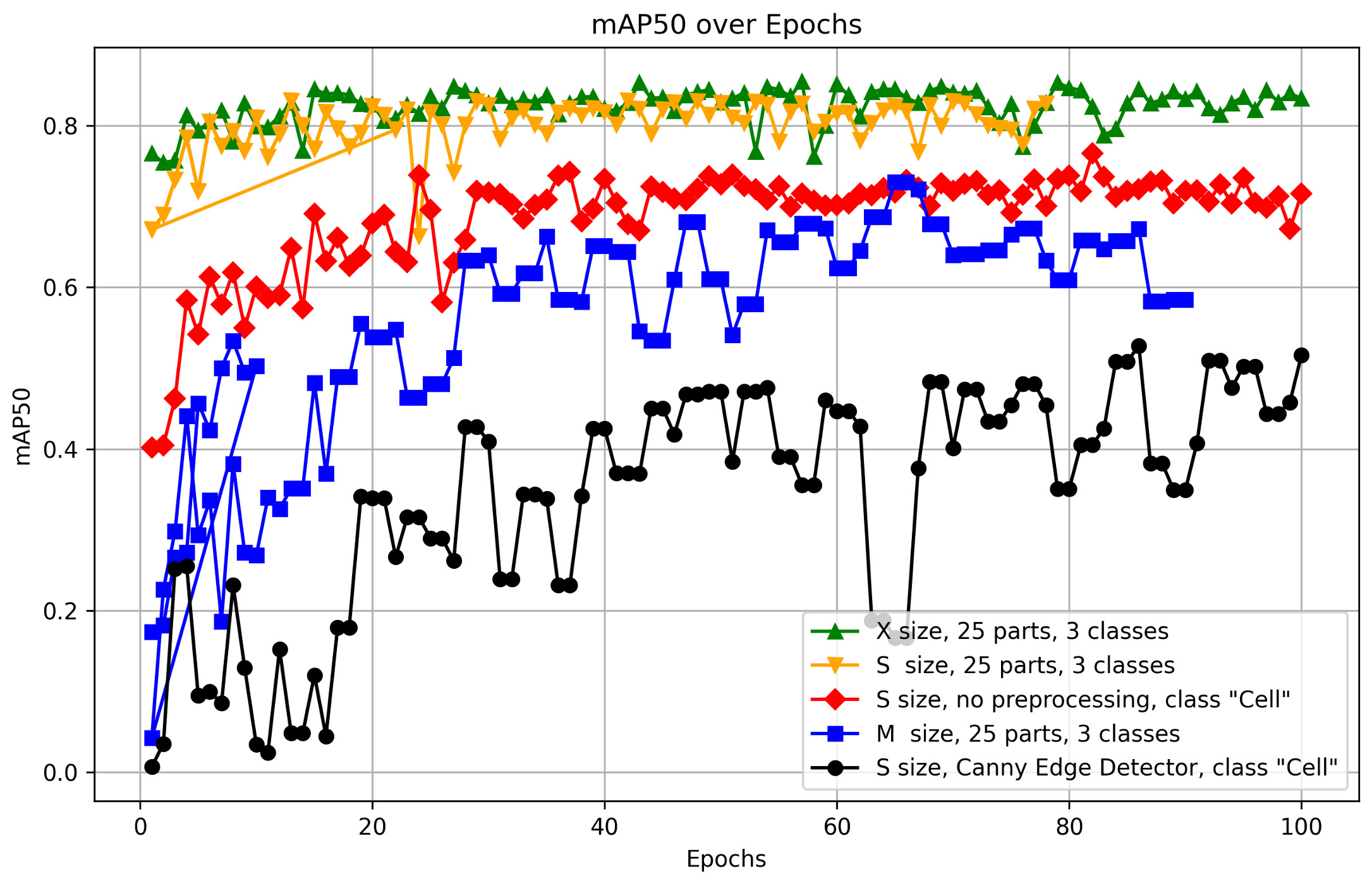

Fig. 10 presents a detailed comparative analysis of the mAP metric for different model sizes and image preprocessing methods. It effectively illustrates how these factors influence model performance.

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Comparison of mAP50 performance across model dimensions and preprocessing techniques. The figure presents a detailed comparative analysis of the mean Average Precision (mAP) metric across different model dimensions and image preprocessing techniques, providing insights into how these factors influence the performance of the YOLOv8S-seg model. The figure was generated using Matplotlib (Python 3.12.4), a Python-based data visualization library. The data used in the plot comes from the CSV files that were automatically generated as a result of the YOLO training process, following the appropriate preprocessing steps.

The key criterion for selecting the optimal preprocessing method and model size was the mAP50 metric. Fig. 10 provides a comparison of various preprocessing options, model sizes, and class counts, enabling the selection of the most suitable model with the best metrics.

It was demonstrated that the optimal number of training epochs for low-contrast images is up to 50. Beyond 50 epochs, a plateau in metrics such as recall and precision is observed, making additional training inefficient. This suggests that a performance limit may have been reached, beyond which further training could lead to overfitting or minimal improvements.

The model shows a noticeable decrease in detection accuracy when working with black and white images. This is likely due to the absence of important visual features, such as color gradients and contrasts, which play a critical role in object recognition. The reduction in available visual information in grayscale limits the model’s ability to accurately localize and identify cellular structures.

Data augmentation plays a crucial role in improving model performance. By increasing the heterogeneity and volume of training data, augmentation significantly enhances the model’s ability to generalize results on images with varying contrasts. This process enables the model to better recognize and localize objects across images of different quality, a characteristic typical of biological microphotographs.

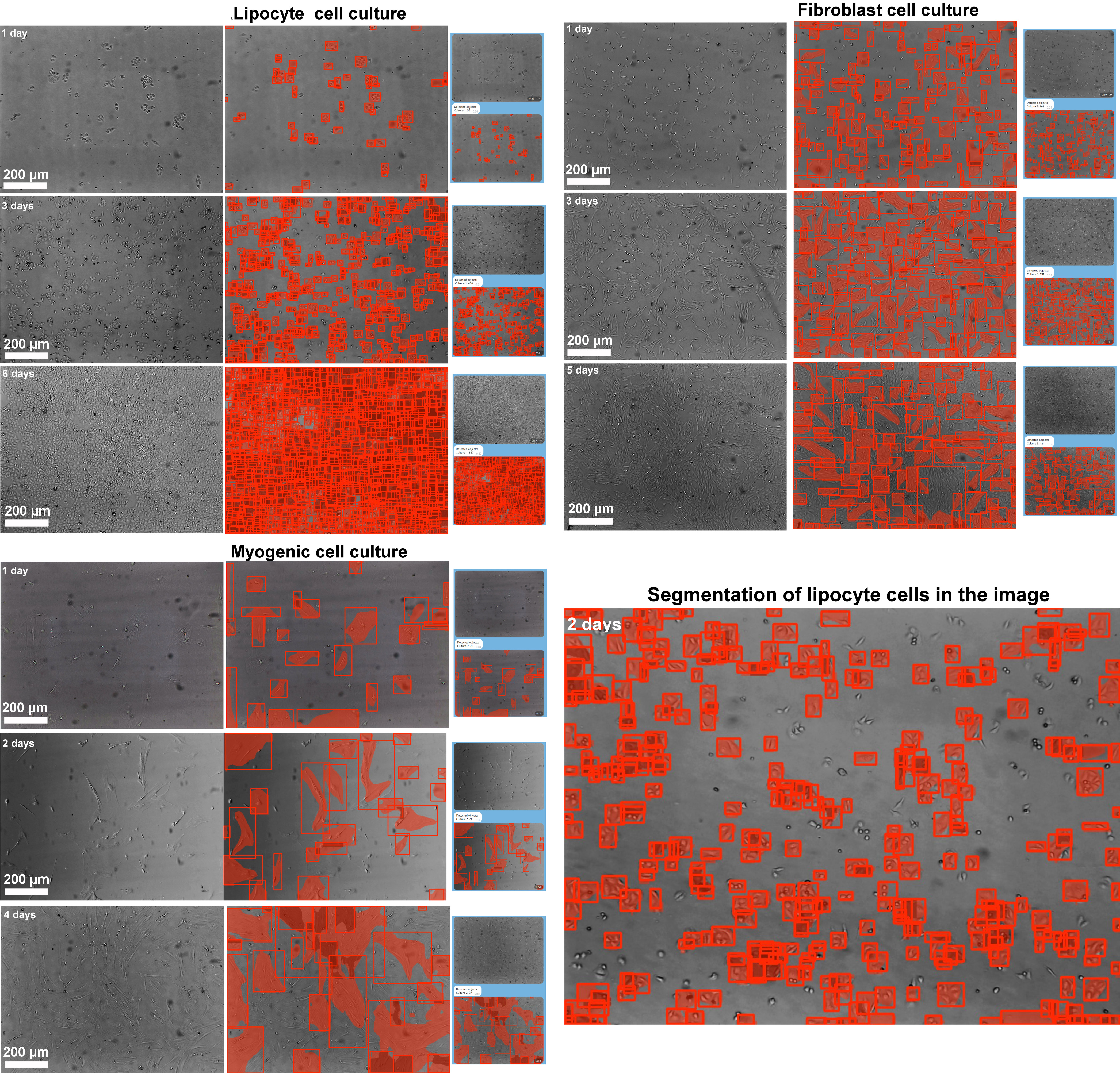

The study utilized YOLO deep learning models to perform automated cell segmentation within an image processing pipeline implemented in a Telegram bot interface. The bot supports four model configurations: a general “Multiclass” model and three specialized models trained on specific cell cultures, designated as “Lipoblasts”, “Myogenic Cells”, and “Fibroblasts”. Each model was designed and optimized for processing various cell types with distinct morphological parameters. ONNX was employed for model compatibility, facilitating integration into the Python-based Telegram bot. The bot’s operation is illustrated in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Segmentation of the image of cells of three cultures in different time intervals of the Telegram bot operating on the basis of the trained YOLO model. Scale bar 200 µm.

Upon receiving an image from a user, the bot divides it into 640

For every segmented image, the YOLO model provides not only spatial segmentation but also classification of detected cells based on predefined model classes. Upon completion of the segmentation process, the bot sums up the detected cells according to their categories, delivering a summary of the cellular composition in each image. For images processed using the “Multiclass” model, the bot filters detection results to focus on a specific cell type as requested by the user. This allows for a quantitative assessment of particular cell populations in heterogeneous samples. After processing, the bot delivers the annotated image and corresponding cell count directly to the Telegram chat, making the analysis process fast and user-friendly.

Currently, many countries face a significant shortage of protein-based foods derived from meat. This issue is gradually expanding geographically due to population growth and the inability of traditional livestock farming to meet increasing demand, threatening global food security systems [56, 57]. One potential solution to this problem lies in the development of high-quality cultured meat products and scaling this technology for industrial purposes [1].

This study presents a comprehensive approach to selecting a model and methodology for obtaining cellular material intended for cultured meat production. The use of rabbits as cell donors proved to be highly effective, providing the necessary cell cultures characteristic of meat. Specifically, we differentiated MMSCs isolated from adipose tissue fragments of the greater omentum into lipoblasts and myogenic cells. Fibroblasts were isolated from skin biopsy samples [48]. Enzymatic tissue dissociation and specialized nutrient media enabled the creation of stable cell cultures with high proliferation potential, a key factor for the scalability of cultured meat technologies. The viability and proliferative activity of cells directly impact the efficiency of the process [58].

The three cell lines obtained in this study are aimed at creating cultured meat capable of replicating the nutritional and sensory qualities of natural meat. For instance, fibroblasts are responsible for forming the tissue framework that provides mechanical strength. In our study, they retained a prolonged ability for subcultivation without losing their morphological and proliferative characteristics [54, 59, 60]. Lipoblasts also demonstrated high viability, contributing essential flavor and textural properties to the cultured meat [61, 62]. Additionally, myogenic cells, which are another necessary component of the product, showed stable growth despite the traditional challenges associated with long-term cultivation. This result is particularly important as muscle fibers are the primary structural component of meat [63].

The next step in our research involved creating bioinks that included the necessary organic substances and cellular components. For example, sodium alginate was used as a hydrogel stabilizer through polymerization in the presence of calcium ions, ensuring the required mechanical strength of the final product [14, 15, 16]. A non-toxic sunflower protein concentrate provided texture and strength resembling natural meat and facilitated the uniform distribution of cells in the hydrogel. Additionally, beetroot juice was added to give the bioink a rich red color.

A custom-designed and constructed print head with a hydraulic drive, integrated into a 3D printer, allowed the bioink to be processed into a volumetric cultured meat product. This is undoubtedly a significant achievement, enabling the transition from ground meat to a final product that matches the organoleptic properties and composition of natural meat.

We also conducted a detailed structural analysis of the product using confocal laser scanning and transmission electron microscopy. The results showed that the cell nuclei had a natural oval shape with evenly distributed nucleic acids. No signs of nuclear damage, such as fragmentation or transformation, were detected. The normal morphology of the cell nuclei indicates the preservation and viability of the cells within the 3D construct [64, 65].

In addition, the formation of rounded nuclear clusters resembling spheroids was observed. These structures represent compact, rounded conglomerates composed of several dozen cells [66, 67]. Each cluster was organized in a circular pattern, with nuclei arranged like a wreath around a central area.

Detailed ultrastructural analysis revealed that the 3D tissue construct contained cells exhibiting characteristic features of fibroblasts and lipoblasts. Thin projections extending along the cell bodies were observed against a background of dense cell clustering, facilitating intercellular contact. The nucleoplasm of fibroblasts and lipoblasts was enclosed within a properly shaped oval nuclear membrane. Nucleoli were present, indicating normal functional potential of the cells [68, 69, 70]. Furthermore, the cytoplasm of fibroblasts was rich in organelles, including mitochondria, ER, RER, lysosomes, centrioles, and multivesicular bodies.

Lipoblasts, in turn, contained numerous rounded, osmiophilic lipid droplets. A developed ER network [71], high Golgi apparatus activity [72], and numerous ribosomes pointed to active protein synthesis processes. Overall, these findings confirm the high viability of the cells within the 3D construct. However, it should be noted that myogenic cells, although included in our study, were not examined in detail due to the absence of distinct differentiation markers that could be reliably visualized using the employed methods. This is likely because myogenic cells have more complex requirements for their microenvironment to successfully form myotubes within a 3D construct. These conditions often involve the addition of growth factors, stimulants, or specialized medium components, which were not incorporated into the current experimental setup.

The final stage of this part of our study involved the preparation and tasting of the product by volunteers. During thermal processing, the Maillard reaction was observed, imparting a characteristic golden-brown color to the product [73]. The organoleptic properties were similar to those of natural meat.

Subsequently, our research focused on developing software for the detection and counting of cells in cultured meat. It is well known that selecting an optimal culture medium is a critical step in the cultivation of cell cultures for this purpose. One tool that can optimize this process is an automated cell counter. However, its widespread adoption is limited by high costs, the need for continuous purchase of consumables, software updates, and various technical complexities.

As a result, manual cell counting using a hemocytometer remains one of the most common methods. This approach has gained widespread recognition for its affordability and versatility. Hemocytometers, such as the widely used Neubauer chamber, enable standard calculations of cell concentration in samples by visualizing cells under a microscope within specially marked grid squares [74]. Despite its accuracy, this method is less applicable in studies involving large datasets due to significant time requirements. For example, a laboratory technician typically spends 15–20 minutes counting cells in a single culture flask, and the number of flasks can reach up to twenty in one workday.

In contrast, our approach using automated counting methods based on machine learning reduces the time required to approximately two minutes for imaging and a few seconds for cell counting within the software environment. Furthermore, manual cell counting necessitates detaching cells from growth vessels, potentially disrupting continuous cell growth and extending production timelines. Automated cell counters address these limitations by eliminating the need for manual detachment and counting, thereby supporting uninterrupted cell proliferation. It has also been demonstrated that traditional manual methods, involving trypsinization to transfer cells into the hemocytometer, negatively impact cell viability [25, 26].

We demonstrated the effectiveness of cell segmentation using the YOLO model implemented in a widely accessible messenger. Traditional software for cell counting often requires specialized expertise in digital image processing of biological structures and substantial computational resources. These factors present significant obstacles to the use of automated image analysis methods for biological objects, including cells. The proposed YOLO-based model, implemented as a Telegram bot, provides researchers with an intuitive platform that overcomes these challenges, enabling cell counting on demand using a smartphone or a computer with Telegram installed.

The YOLO model demonstrated high segmentation accuracy and computational efficiency, highlighting its significant potential for scientific and industrial applications. The accuracy achieved in this study is comparable to that of commercial software, which often requires expensive licenses and significant computational resources. Our software package, integrated into Telegram, provides similar accuracy without the need for specialized equipment.

This study underscores the advantages and limitations of using the YOLOv8-seg model for automated cell counting in cultured meat. One key advantage is the superior generalization ability of the multiclass model, allowing it to recognize and count cells from various cultures with greater accuracy compared to a monoclass configuration [75]. The results suggest that multiclass training enables the model to develop a deeper understanding of patterns characteristic of different cell types, enabling it to perform effectively even when constrained by single-class inference.

Myogenic cells remain a significant challenge for accurate detection. This is likely due to an insufficient training dataset and their complex morphology, characterized by blurred and overlapping cell boundaries. Increasing the number of annotated images for this cell type is expected to enhance the model’s performance. Poor performance on gradient images suggests the need for preprocessing methods or models tailored for low-contrast images. Using strategies such as transfer learning and multimodal learning can improve the adaptability of multiclass models, as demonstrated in other studies. Transfer learning, where the model is pretrained on a broader dataset, establishes a foundation for recognizing general patterns, enhancing its ability to handle complex images such as cultured meat cell cultures [76, 77, 78].

Multimodal learning, designed to teach the model to extract common features across tasks, helps identify subtle and multilayered features critical for recognizing diverse cell types. Combining transfer learning to leverage pretrained visual patterns and multimodal learning to bolster model resilience across various tasks can enable YOLOv8-seg to perform effectively in diverse conditions and with underrepresented cell types. This could significantly improve the accuracy of cell image analysis in cultured meat production.

Data augmentation has proven most effective for improving model performance, particularly with small datasets featuring low-contrast images and complex biological object boundaries. Expanding the diversity of training material allows the model to better adapt to images of varying quality, making cell identification and localization more accurate. However, there are limitations such as built-in augmentation methods in YOLOv8-seg for example, resizing, rotations, and image combinations may not suffice for low-contrast or noisy biological images. Incorporating additional techniques like color balance and contrast adjustments, or employing generative adversarial networks to create synthetic data, could significantly enhance detection results [79, 80].

In YOLO models, the detection head is a critical component for object localization and classification. It generates bounding box coordinates and class probabilities for each detected object. While optimized for fast inference, adding additional detection heads can improve results [80]. However, this focus on speed may compromise accuracy for complex and low-contrast images [81]. For instance, a single detection head may struggle with detecting small objects or distinguishing them precisely. YOLO models perform best in well-lit, high-contrast environments, but declining parameters can reduce accuracy due to a lack of visual markers for detection [38, 82]. Interestingly, contrast enhancement does not always correlate with improved model accuracy [83, 84]. For example, YOLOv5 achieved optimal training results by the 50th epoch, after which a plateau or degradation phase ensued [85].

High-density cell culture analysis also poses a significant challenge. YOLOv8-seg performs effectively with moderate object densities but its efficiency drops sharply in cases of closely packed cells, as observed in our study. Monoclass and multiclass models showed high accuracy during the early stages of cultivation but declined significantly at later stages. This is likely due to insufficient training on high-density cell cultures, overfitting, or blurred biological object boundaries. Alternative methodologies, such as visual transformers (ViT), could provide an effective solution when traditional convolutional neural networks fall short. ViTs can further optimize the accuracy of cell detection and counting in low-contrast and high-density images [86].

Despite its undeniable advantages, the multiclass model of the bot faces difficulties in processing images with overlapping or densely clustered cells. In future studies, we plan to enhance detection algorithms in multiclass environments by integrating advanced postprocessing techniques, such as non-maximum suppression adjustments, to improve confidence in detections on high-density cell images. Also, improving the model’s adaptability could enable the bot to support a broader range of cell types. Interface enhancements may include interactive reporting options, allowing users to customize counting results and analysis parameters.

While our study focused on training the YOLOv8-seg model for cell detection and counting in a two-dimensional culture environment, the proposed approach holds significant potential for adaptation to the analysis of cells in 3D bioprinting scaffolds. However, this adaptation would require the optimization of several processes, including the modification of image processing algorithms to account for the unique characteristics of three-dimensional cultures, such as the spatial orientation of cells, signal heterogeneity, and potential artifacts caused by imaging depth.

An additional challenge would involve calibrating the model for three-dimensional conditions, which necessitates the development of specialized training datasets annotated specifically for cells within 3D structures. This step would enable the algorithm to accommodate complex geometrical shapes and spatial relationships between cells. Furthermore, the adaptation of post-processing techniques, such as segmentation and volumetric cell counting methods, would ensure more accurate analyses of cell distribution and proliferation within bioprinted scaffolds.

Such modifications to the model open new opportunities for its application in advanced tissue engineering tasks, providing precise monitoring of cell behavior in complex three-dimensional systems. This capability is particularly relevant for addressing critical challenges in regenerative medicine and bioprinting.

A 3D tissue construct was successfully developed using an innovative bioengineering approach. Microscopic examination, including confocal and transmission electron microscopy, provided detailed insights into the construct’s cellular composition. These analyses revealed that the cells within the polymerized alginate hydrogel were not only viable but also exhibited robust metabolic activity, indicating their potential for sustained functionality in the construct. The engineered product showed properties similar to natural meat, including structural integrity and organoleptic qualities, making it a promising alternative to conventional meat products.

Moreover, advanced computational methods were employed to enhance cell monitoring and identification processes. Trained neural network models, integrated into a user-friendly Telegram bot, demonstrated high efficiency in detecting and quantifying various cell types such as lipoblasts, fibroblasts, and myogenic cells from digital images. These models, built on state-of-the-art YOLO architecture, provided precise and reliable assessments, significantly contributing to the study’s goal of integrating software-driven analysis with tissue engineering advancements.

The original data presented in the study are openly available. The dataset is presented on Ro-boflow https://app.roboflow.com/cultures/cell-segmentation-ci5n3/browse?queryText=&pageSize=50&startingIndex=0&browseQuery=true, the code link is https://github.com/rosali3/cell_count. The user can access the Telegram bot using https://t.me/cell_counter_dstu_botlink. All data reported in this paper will also be shared by the lead contact upon request.

Writing—original draft preparation, RN; Methodology, RN, SG, SR; Conceptualization, MP, SR; Supervision, SR and MP; Investigation, RN, SR, MP, SG, AL, MK, DS, EK; Visualization, RN, SG, EK, MK, AL, SR; Validation, RN, SR, MP, MK, SG, EK; Data curation, EK; Writing—review & editing, SR. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The studies were carried out in accordance with the requirements of the Council Directive of the European Communities 86/609/EEC on the use of animals for experimental research (November 24, 1986), the “Rules of Laboratory Practice in the Russian Federation” (Order No. 708n of August 23, 2010) and the organization of procedures for working with laboratory animals (GOST 33215–2014) and Protocol No. 2/BVS-DSTU-2020-017, approved by the Bioethics Commission of the Don State Technical University on February 17, 2020.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation No. FZNE-2024-0004.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The collaboration with Wizntech LLC was exclusively scientific in scope, with no influence on the judgments made during data interpretation or manuscript preparation.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL36266.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.