1 Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, School and Operative Unit of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, University of Messina, 98125 Messina, Italy

2 Department of Precision Medicine in Medical, Surgical and Critical Care (Me.Pre.C.C.), University of Palermo, 90127 Palermo, Italy

3 Center of Advanced Science and Technology (CAST), G. D’Annunzio University, 66100 Chieti, Italy

4 Institute of Clinical Immunotherapy and Advanced Biological Treatments, 65121 Pescara, Italy

5 Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Section of Dermatology, University of Messina, 98125 Messina, Italy

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Inter-kingdom communication between human microbiota and mast cells (MCs), as sentinels of innate immunity, is crucial in determining health and disease. This complex signaling hub involves micro-organisms and, more importantly, their metabolic products. Gut microbiota is the host’s largest symbiotic ecosystem and, under physiological conditions, it plays a vital role in mediating MCs tolerogenic priming, thus ensuring immune homeostasis across organs. Conversely, intestinal dysbiosis of various etiologies promotes MC-oriented inflammation along major body axes, including gut-skin, gut-lung, gut-liver, and gut-brain. This review of international scientific literature provides a comprehensive overview of the cross-talk under investigation. This process is a key biological event involved in disease development across clinical fields, with significant prognostic and therapeutic implications for future research.

Keywords

- mast cell

- microbiome

- skin

- gut

- cancer

- dysbiosis

- immunity

Mast cells (MCs) are pivotal components of the immune system. Derived from hematopoietic stem cells, they are strategically located at sites that interface with the environment, such as the respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, and skin. MCs release various mediators, including histamine, cytokines, chemokines, and proteases, upon activation. This diverse repertoire allows MCs to perform a broad spectrum of functions, influencing both physiological processes and pathological conditions, particularly allergic reactions and pathogen defense [1]. Recent research has revealed an interplay between MCs and the microbiome, which consists of microorganisms primarily residing in the gut and on the skin. The microbiome is key to maintaining homeostasis, modulating immune responses, and protecting against pathogens [2]. Alterations in the microbiome, known as dysbiosis, have been linked to several diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), atopic dermatitis (AD), urticaria, allergic asthma, and systemic conditions such as obesity and neurologic syndromes [3, 4]. In physiological contexts, MCs contribute to epithelial integrity and mucosal immunity. These cells are activated by microbial signals through pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and other receptor-mediated mechanisms, which influence the composition and function of the microbiome. For instance, MC-derived mediators can shape the microbial community by affecting the growth and survival of specific microbial species, thereby supporting a balanced microbiome that promotes health [5]. Conversely, in pathological states, MCs can exacerbate dysbiosis and inflammation. Aberrant MC activation may lead to excessive release of inflammatory mediators, disrupting the epithelial barrier and promoting an environment that favors harmful microbial overgrowth. This cycle of inflammation and dysbiosis further worsens pathological conditions. Recognizing the dual role of MCs in health and disease may highlight their potential as therapeutic targets [5].

This article explores the multifaceted crosstalk between MC and the microbiome, shedding light on the role of MCs as contributors to both physiological homeostasis and pathological processes. By analyzing the mechanisms underlying MC-microbiome interactions, we can better understand their impact on human health and disease, thus paving the way for novel therapeutic strategies.

The gut microbiome is not merely a simple digestive organ; rather, it plays a

leading role in metabolism, immune defense, and behavioral functioning. Its

extensive functional involvement is influenced by factors such as stress, life

stages, geography, diet, and medications, even before birth [6]. Breastfeeding

significantly shapes the infant gut microbiota, partly through certain microbes

present in maternal milk. This microbiota is vital for maintaining intestinal

barrier integrity and promoting mucosal immune system development. Recent

experiments on humans and murine models have shown that specific human milk

oligosaccharides, known for their prebiotic functions, can modulate

gastrointestinal gene expression of MCs, supporting their homeostasis. Food

antigens from breast milk also seem to promote immune tolerance to those same

antigens in infants [7, 8]. As the host’s largest symbiotic ecosystem, the gut

microbiota maintains intestinal homeostasis through dynamic two-way crosstalk

with the intestinal mucosal immune system. The commensal microbiome regulates the

maturation of this immune system, which, in turn, controls its physiological

composition and function [9, 10]. Intestinal MCs are closely associated with

nerves and small blood vessels, forming the neuroimmune network’s functional

backbone. In the gut, MCs primarily increase blood flow and motor activity,

providing first-line defense by removing toxins, microbial antigens, and other

harmful agents. MCs also mediate interactions with innate immune cells, such as

innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), to ensure a directed inflammatory response [10, 11].

In this refined signaling hub between the gut microbiota and the innate immune

system, commensal microorganisms are essential for the maturation and function of

ILCs. Specifically, the activation of ILC2s by cytokines derived from the

epithelium, particularly interleukin (IL)-25, is microbiota-dependent. Activated

ILC2s coordinate the type 2 immune response by interacting with other immune

cells, including MCs [10, 12]. The gut microbiota plays a crucial immunoregulatory

role, promoting a tolerogenic mucosal environment. This function is mediated by

short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate,

produced from the fermentation of dietary fibers by commensal microbial species.

SCFAs enhance regulatory T cells (Tregs) activity, Immunoglobulin (Ig)A

production, and suppress T-cell and ILCs activity. Propionate and butyrate

inhibit both IgE- and non-IgE-mediated MC activation. This suppression of MC

degranulation occurs at the epigenetic level. Even more noteworthy is the

systemic immunoregulatory role of SCFAs, as MCs reside in various vascularized

tissues beyond the gut [13, 14]. Iketani et al. [15] recently reported

that certain gut microbiota components can suppress granule formation in MCs

through epigenetic mechanisms. This suppression increases the expression of the

transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein

As an interface with the environment, the skin is a complex ecosystem hosting a diverse array of commensal bacteria, fungi, and viruses. This community shapes the skin microbiome, which coexists in a finely-tuned balance and protects against pathogens. Bacteria are the most prevalent microorganisms in this ecosystem, primarily from three genera: Corynebacteria, Propionibacteria, and Staphylococci. In healthy individuals, the microbiome maintains overall stability, as specific species are occasionally replaced by similar ones. Protection from multiple types of damage is a key function of the skin. Being tissue-resident innate immune cells, mast cells contribute significantly to this defense and the maintenance of skin homeostasis [18]. The interaction between skin immunity and the microbiome is complex; dysbiosis, or microbiome imbalance, can lead to cutaneous autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Such imbalances may arise due to bactericidal products, environmental factors, and host-related factors [2, 19]. In elderly populations, the cutaneous microbiome often acts as a pro-inflammatory trigger. An age-related imbalance between beneficial and harmful microorganisms contributes to a condition known as inflammaging [20]. The complex relationship between the cutaneous microbiome and MCs is exemplified by the microbiome’s ability to stimulate MC maturation. Wang et al. [21], demonstrated this by comparing MC maturation in germ-free (GF) and specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice. They used the expression of the stem cell factor (SCF) receptor, c-kit, as a marker of MC maturity and low c-kit expression as a marker of immaturity. GF mice exhibited fewer mature MCs and lower SCF levels in the skin than SPF mice. However, restoring the microbiota in GF mice through exposure to SPF mice also restored MC maturation. Wang et al. [21] also explored the underlying mechanism and demonstrated that staphylococcal lipoteichoic acid (SLA) increases SCF production in keratinocytes. This increase boosts the number of c-kit-expressing MCs in both GF and SPF mice. When the SCF gene was specifically knocked out in keratinocytes, MC recruitment to the skin was completely suppressed, highlighting the dependence of MC migration on keratinocyte-derived SCF. Thus, the skin microbiome regulates MC homing and maturation by modulating keratinocyte SCF production in response to microbial signals like SLA. While these findings illuminate the relationship between the cutaneous microbiome and MC maturation, further research is needed to identify additional bacteria-derived molecules that may affect this system [21]. When the skin barrier is compromised, the synergistic role of MCs and the microbiome becomes evident. The microbiome alerts the immune system by releasing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) which MCs detect, initiating wound healing [22, 23, 24]. MCs, as cutaneous and mucosal sentinels, interact with bacterial components, some of which penetrate deeper skin layers. In GF murine models lacking a microbiome, the immune system initially responds to wounds via danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from damaged epidermal cells. Without bacteria and PAMPs priming the immune system, the initial wound response is slower because bacteria and PAMPs did not prime the immune system [22]. However, MCs must be tightly regulated to avoid excessive immune activation in response to commensal bacteria. Di Nardo et al. [25] identified a significant interaction between MCs and dermal fibroblasts. Co-culturing these cells was found to induce MC tolerance to commensal bacteria, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8) and Type 2 helper T cells (Th2) cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13) [25]. Finally, bacterial communication within and between species affects MC-mediated inflammation through sophisticated mechanisms of cell-cell communication to share information and regulate gene expression [26]. One key method is quorum sensing, where bacteria release and detect quorum-sensing molecules (QSMs) enabling them to monitor population density and coordinate actions such as biofilm formation, virulence, and gene expression. Gram-negative bacteria typically use acyl-homoserine lactones, while Gram-positive bacteria use self-inducing peptides as QSMs. MCs, interacting with cationic QSMs from Gram-positive bacteria through Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptor member B2 in mice and Mas-related G-protein coupled receptor member X2 in humans, become activated and degranulate, enhancing bacterial clearance [27].

In functional gastroenteric disorders and stress-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction, the interaction between MCs and administered probiotics may play a protective role [28, 29]. In irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), especially the post-infectious subtype, infective gastroenteritis significantly contributes to systemic inflammation and reduced microbiome diversity. Increased activity and density of intestinal MCs, with varying involvement across IBS subtypes, appear to underlie visceral hypersensitivity (VH) symptoms and may influence their severity [30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. Alongside MCs, the intestinal flora contributes to VH pathogenesis by acting as an intermediary in bidirectional signal transduction between the gut and brain, similarly to how MCs interface between the nervous and immune systems [34, 35].

Therapeutic efficacy in reducing VH with probiotics and the MC stabilizer

ketotifen supports the dual pathogenetic role of MCs and the microbiome. Certain

probiotics, such as Bifidobacterium and Bacillus, appear to inhibit IgE-dependent

MC activation and degranulation. They do so by downregulating high-affinity IgE

receptor 1, histamine H4 receptor expression, and a Toll-like receptor

(TLR)2-dependent mechanism in human MCs. Additionally, these probiotics reduce

Clostridium sensu stricto 1 abundance in VH rats, likely involved in MC

crosstalk [35]. In vitro and in vivo findings suggest that

lactobacilli, including Limosilactobacillus fermentum, can modulate MC

degranulation by significantly reducing the degranulation marker

Intestinal MC activation and degranulation are well-known mechanisms that support nociception, mucosal inflammation, and epithelial permeability. Dysbiosis contributes to this process by disrupting endogenous symbionts, such as decreasing Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides while increasing Firmicutes. This imbalance causes immune dyshomeostasis, affecting MCs directly through chemokine release from epithelial cells and indirectly through bile acids, organic acids, amino acids, phenols, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and SCFAs. Increased mucosal bacterial translocation alone also seems to upregulate MC signaling [34, 36]. Even more interesting is the massive autonomous production of histamine by Klebsiella aerogenes, a constituent of the fecal microbiome of IBS patients. The interaction produces histamine autonomously, contributing to VH. Interaction of bacterial histamine with the histamine 4 receptor activates and accumulates MCs, worsening VH symptoms [37]. Diarrhea and abdominal pain, common IBS symptoms, are enhanced by pro-serotonergic crosstalk between the altered microbiota and intestinal MCs. In diarrhea-predominant IBS, fecal lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and trypsin stimulate mucosal MCs to release prostaglandin E2, downregulating serotonin reuptake transporters in intestinal epithelial cells and increasing mucosal serotoninergic levels [38].

Microbiota-MC activating crosstalk occurs through the recognition of specific bacterial products by precise MC receptors. LPS interacts with TLR4, flagellin with TLR5 receptors, and microbial peptidoglycan with TLR2 receptors. Peptidoglycan elicits both MC degranulation and cytokine release, while LPS only triggers cytokine release, highlighting the specificity of MC responses to bacterial components [36]. Beyond bacterial dysbiosis, mycobiome (fungal microbiome) dysbiosis also appears to play a role in developing IBS-related VH. A proposed mechanism involves harmful crosstalk between fungal antigens and MCs, leading to histaminergic degranulation and activation of histamine 1 receptors. This process sensitizes nociceptive transient reporter potential V1-ion channels on afferent sensory neurons, causing abdominal pain [39, 40]. An emerging area of study focuses on the bi-directional interplay between gut microbiota and hepatic MCs along the gut-liver axis, potentially influencing liver disorders. Gut dysbiosis, triggered by factors like alcohol intake, diet, antibiotics, pollution, lifestyle, and epigenetics, can increase intestinal permeability. This permeability allows bacterial compounds such as PAMPs, DAMPs, SCFAs, and bacterial ethanol to enter the portal vein, stimulating hepatic immune responses and involving MCs in various liver diseases.

MCs contribute to chronic inflammation in a broad spectrum of liver diseases,

including alcoholic liver disease (ALD), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

(NAFLD)/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), viral hepatitis, hepatic

fibrogenesis, cholestatic cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In ALD,

tryptase- and chymase-positive MC populations correlate with fibrosis severity.

Inflammation in ALD appears to be sustained by mediators, including nuclear

factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-

| Liver disease | MCs-mediated pathophysiology | Pathways involved |

| ALD | Tryptase- and chymase-positive MCs triggering liver fibrosis | NF- |

| NAFLD/NASH | Hepatic MCs triggering lipid accumulation, microvesicular steatosis, fibrogenesis, angiogenesis, ductal reaction, and biliary senescence | NF- |

| Viral hepatitis (long-term HCV) | Hepatic MCs triggering fibrosis and steatosis in the hepatic portal area | Not reported |

| Hepatic fibrogenesis | Hepatic MCs activation and promotion of oxidative stress by downregulating GSH, GSH-Px, and GR | SCF/c-kit, TGF- |

| Cholestatic cirrhosis | MCs-mediated vascular cell activation, ductal reaction, fibrosis, hyperplasia, and biliary senescence | Not reported |

| HCC | Antitumor immunity suppression, IL-17 stimulation, and angiogenesis promotion, development of lamellipodia, MMP-2 production, and apoptosis suppression | cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway |

Gut dysbiosis-hepatic MC-mediated liver disorders, along with pathophysiological

events and involved pathways. Abbreviations: MCs, mast cells; ALD, alcoholic

liver disease; NAFLD/NASH, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NF-

Despite their scarce presence in the healthy human central nervous system, MCs are key components of the neurovascular unit, influencing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and other brain structures. In the microbiota-gut-brain axis, the crosstalk between gut microbiota and brain MCs-neural cells balances neuroprotection and neurodegeneration, contributing to the onset of disorders such as multiple sclerosis (MS), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease (PD), and epilepsy. Interestingly, these neurological disorders may also relate to age-related changes in the small intestinal microbiome [42]. The pathophysiological mechanism driving the pathogenesis of these neuropathies lies in the harmful crosstalk between the gut microbiota and MCs. This interaction triggers microglial activation, which in turn promotes neuroinflammatory responses that lead to neuronal death and neurotoxicity [43]. The secretion of several MC mediators appears to be differently regulated by the various microbial species, either in a pro-inflammatory sense (thus eliciting neuroinflammation) or in a tolerogenic sense [44]. Microbial regulation of the MC inflammatory response requires an environmental sensor of xenobiotic ligands (both exogenous and endogenous), which is the Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR). The AhR acts as the host-microbe interface and modulates host defense mechanisms, in a protective or non-protective manner. Of the endogenous AhR ligands, some microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites appear to prime MCs for immune tolerance [45]. A significant advance in MS research revealed, ex vivo, a protective role for the microbiome-MC crosstalk, mediated by the microbial postbiotic tryptophan metabolite indole-3-carboxaldehyde. This metabolite likely induces MC tolerance through the AhR and tryptophan hydroxylase 1 pathway, promoting expression of IL-6, IL-10, TGF-beta and 5-hydroxytryptamine, thus controlling and modulating peripheral adaptive immunity [46]. The gut microbiota-brain axis relies heavily on brain-resident and peripheral immune cells. It activates the peripheral immune response, directly impacting neuroinflammation. It also influences brain glial cell activity, essential for neurogenesis, neural growth, synapse homeostasis, neurotransmission, central nervous system immune response, and BBB integrity [47, 48].

In Alzheimer’s disease, peripheral inflammation, alongside neuroinflammation,

primarily targets microglia. Peripheral inflammatory mediators, including

cytokines, chemokines, DAMPs, and PAMPs, trigger early immune responses in the

brain. An altered gut microbiota contributes to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s

by disrupting normal neurogenesis. Dysbiosis, coupled with an altered immune

response and neuroinflammation, impairs adult neurogenesis, causing cognitive

decline in Alzheimer’s disease [48]. Furthermore, gut dysbiosis—marked by

decreased Firmicutes and increased Bifidobacterium and

Proteobacteria—may promote amyloid precursor protein accumulation, a

factor in Alzheimer’s disease progression. Once formed, amyloid

In Huntington’s disease (HD), innate immunity and microglial activation contribute to pathogenesis, even in preclinical stages. Microgliosis is a source of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress-related neurodegeneration and is well-documented in ALS and frontotemporal dementia. Astrogliosis, with reactive astrocytes, also plays a pathogenic role, releasing neurotoxic mediators that damage neurons [48]. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSDs) may also involve harmful interactions between altered gut microbiota and intestinal MCs. This interaction can trigger mucosal inflammation and compromise barrier integrity, allowing pathogens to cross more easily, thereby contributing to NMOSD. In NMOSD, MCs release pro-inflammatory mediators that damage tight junctions and may migrate to the central nervous system, interacting with neurons, glial cells, and endothelial cells to induce further damage [49]. Bidirectional crosstalk between brain MCs and gut microbiota is particularly relevant in post-acute ischemic stroke. Recent in vivo evidence suggests that brain MC activation is the first local inflammatory response subsequently triggering peripheral immune responses and intestinal MCs activation. In aged mice, this activation causes a bacterial phylum shift and changes in beta-diversity, notably reducing Clostridiales and increasing Bacteroidales seven days post-stroke compared to pre-stroke levels. MC-mediated gut dysbiosis also appears to exacerbate stroke outcomes [50]. As a consequence, new therapeutic strategies—both pharmacological and non-pharmacological, such as minimally invasive vagus nerve stimulation—aim to prevent MC histamine release and modulate MC degranulation. These approaches could improve gut dysbiosis, reduce post-stroke intestinal and neuroinflammation, and enhance neurological and functional recovery [51, 52].

The multifactorial pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis (AD) remains complex, involving genes, altered immune responses, and epidermal dysfunction, with the cutaneous and gut microbiome playing a synergistic role [53]. Initially, the “inside-outside” view suggested that gut microbiome alterations, resulting from an underlying immunological abnormality, were the first step in AD pathogenesis. An alternative “outside-inside” theory proposed that permeability barrier defects contributed significantly to disease onset [54, 55]. Skin barrier genetic defects, worsened by cutaneous dysbiosis, have now been identified as the primary pathogenic event in AD [54, 55, 56, 57]. Compared to healthy individuals, AD patients have a higher proportion of Staphylococcus aureus in their skin microbiome. This bacterium stimulates proinflammatory cytokine genes (e.g., IL-4, IL-13, thymic stromal lymphopoietin) and promotes Th1/Th2 immune responses. S. aureus also impairs Treg cell regulatory function, increasing inflammation and reducing microbial diversity. In a mouse model, mutant mice with AD-like symptoms showed increased S. aureus colonization, triggering MC activation and degranulation. Treatments that reduced S. aureus skin load also reduced AD symptoms, highlighting S. aureus as a possible driver of AD and a target for antimicrobial therapy rather than traditional antibiotics [58].

Conversely, certain bacteria, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis may inhibit S. aureus growth, thus potentially reducing AD flares and development [59]. AD has systemic implications, particularly through the gut-skin axis, linking skin inflammation to food allergies. AD-associated skin inflammation promotes sensitization to food allergens via skin exposure before oral exposure, bypassing oral tolerance. This process involves MCs, basophils, dendritic cells, and Th2 cells, leading to gut allergic inflammation. Interestingly, epicutaneous immunotherapy, which delivers allergens through healthy skin, shows promise in inducing food tolerance by possibly stimulating Treg cells [60]. In the context of the gut-skin axis, AD patients often exhibit reduced gut microbial diversity, marked by fewer beneficial bacteria (e.g., Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species) and more harmful bacteria (e.g., Clostridium difficile and Escherichia coli). This imbalance promotes a Th2-skewed, MC-mediated immune response [6, 61]. Gut dysbiosis may hyperactivate MCs, releasing pro-inflammatory mediators including histamine, cytokines, and proteases that drive inflammation. These bacteria also influence short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, which has anti-inflammatory effects and typically protects against AD [62]. Restoring gut microbiome balance through probiotics emerges as a therapeutic strategy for AD, as probiotics interact with gastrointestinal mucosa and gut-associated lymphoid tissue. This approach may reduce MC infiltration, total IgE levels, and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression [63, 64]. While probiotic effectiveness is inconclusive, gut microbiome restoration could modulate the immune system, strengthen the epithelial barrier, and reduce corticosteroid doses required for flare management [65, 66, 67]. Finally, exploring the link between MCs and the cutaneous microbiome may extend the hygiene hypothesis, which suggests that early-life microbial exposure protects against atopic diseases. Traditionally, this theory attributes a protective effect to high bacterial exposure in unhygienic environments, promoting Th1 rather than Th2 responses and reducing allergic sensitization [68]. From this perspective, MCs may play a role in the hygiene hypothesis by promoting protection through inflammation suppression or immune tolerance, along with Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes. Future research in this area may illuminate the effects of lifestyle and environment on inflammatory and atopic disease development [18].

As immune sentinels, MCs play a crucial role in facilitating beneficial communication between the microbiota and the host. Non-pathogenic bacteria, including commensal and probiotic strains, appear to exert immunomodulatory effects by directly and indirectly suppressing MC functions. This suppression primarily occurs through the systemic immunoregulatory action of gut microbial-derived short-chain fatty acids SCFAs [13, 69]. In the gut-lung axis, preliminary evidence highlights butyrate’s immunoregulatory role in allergic asthma, which is achieved through epigenetic modulation of MC activation mechanisms [70]. The “microbiome hypothesis” supports the idea that diet- or antibiotic-induced microbiota perturbations disrupt immunological tolerance, promoting the development and severity of allergic inflammation [69, 71, 72]. Recent studies suggest that Lactobacillus supplementation and long-term intermittent fasting may protect against food allergies by optimizing gut microbiota [73, 74, 75]. More specifically, certain intestinal bacteria, such as Bacteroides acidifaciens type A43, have emerged as key players in anti-allergy immunoregulation. These bacteria suppress the expression of the high-affinity IgE receptor on MC surfaces via extracellular signal-regulated kinase inhibition, thus promoting receptor endocytosis [76]. The relationship between chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), an MC-driven disease, and gut microbiota has also been examined. CSU patients exhibit reduced bacterial diversity and lower SCFA levels. This correlates with higher disease activity and increased opportunistic pathogens such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, which contribute to inflammation and rapid CSU flares. In mouse models, an altered microbiome induces heightened MC-driven inflammation, while beneficial bacteria or SCFAs provide protection. These findings underscore the gut microbiota’s role in CSU and suggest microbiome-targeted therapies as promising treatment options [77].

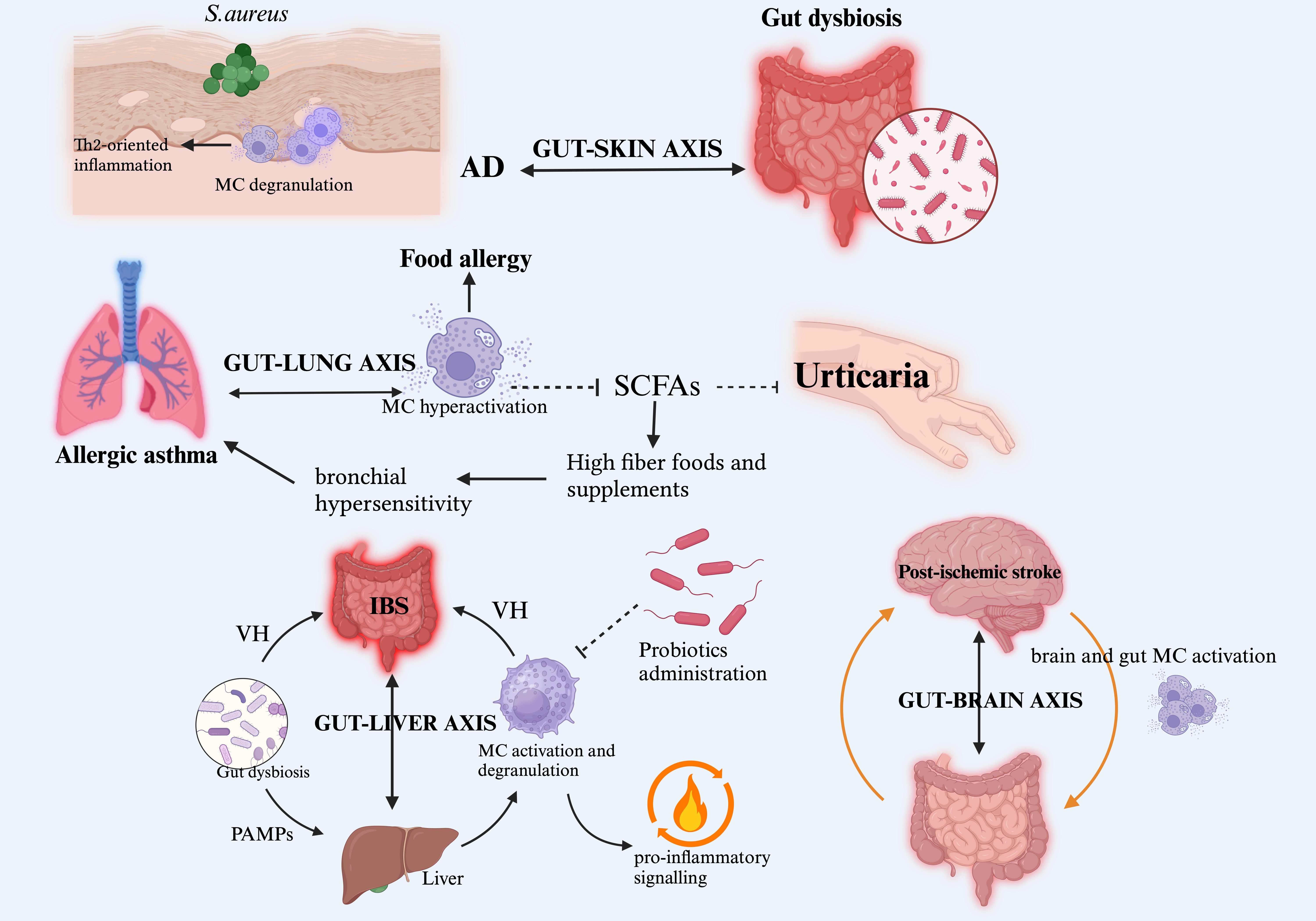

Research has also explored the connection between gut microbiota and antihistamine efficacy in CSU patients. Lachnospiraceae and related taxa are more prevalent in responders than non-responders, indicating a moderate diagnostic value in predicting antihistamine therapy efficacy [78] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The MC-microbiome interplay. This figure illustrates the critical involvement of human microbiome-MC crosstalk in sustaining pathophysiological phenomena and driving disease pathogenesis across diverse clinical settings. Within this complex inter-kingdom communication network, the altered gut microbiota plays a pivotal role, mediating MC activation and targeting inflammatory responses to various organs through functional axes (gut-skin, gut-lung, gut-liver, and gut-brain), delineating the boundary between health and disease. On the tolerogenic side, the immunoregulatory and protective roles of probiotic administration and SCFAs from beneficial bacteria are highlighted. Abbreviations: MC, mast cell; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; VH, visceral hypersensitivity; PAMPs, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; AD, atopic dermatitis; Th2, T helper 2; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids. Created with BioRender.com.

In both humans and companion animals, the commensal microbiota’s pro- or anti-tumor role is well recognized in various cancers [79]. Recent research has focused on specific microbiota-immune system interactions, with preliminary evidence highlighting the significant role of MCs-microbiome crosstalk in oncology. In mouse models of breast cancer, increased MC presence in tumor stromal regions correlates with tumor growth, promoted by antibiotic-induced disturbances in gut microbiota. Antibiotic-induced loss of beneficial gut microbes thus reprograms MC homing and functions in a pro-tumor direction in breast cancer [80]. In hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancer, MCs support breast tissue homeostasis by mediating stromal rearrangement essential for mammary duct formation. However, inflammatory gut dysbiosis, characterized by low biodiversity and inflammation, promotes C-C motif chemokine ligand 2-mediated MC accumulation in non-cancerous breast tissue. This dysbiosis-induced immunological remodulation gives breast tissue-associated MCs a pro-fibrogenic phenotype, promoting fibroblastic activation in adjacent breast tissues and collagen I production, which may lead to early metastatic dissemination of HR+ breast cancer cells [81]. Gut microbiome changes, both qualitative and quantitative, appear to reflect colorectal cancer (CRC) progression stages. The Alistipes genus, notably Alistipes indistinctus, positively associates with MCs. This bacterium may stimulate IL-6 production, which is a key cytokine in promoting MC proliferation and maturation. In the CRC microenvironment, MCs release proangiogenic factors and matrix metalloproteinases, driving neoangiogenesis and tumor invasion [82]. In alcohol-related CRC, stromal tryptase-positive MCs are thought to play a pathogenic role in colon carcinogenesis by promoting a pro-tumorigenic inflammatory environment. This process involves harmful interactions with a gut microbiota altered by alcohol consumption and circadian rhythm disruptions [83]. Interestingly, Huang et al.’s single-center study [84] on the Kirsten ras (KRAS) mutation-associated gut microbiota in CRC found a significant positive correlation between Bifidobacterium spp. and MCs. This correlation suggests that Bifidobacterium may play a protective role in preventing CRC progression by modulating MC activity [84]. In metastatic CRC, the gut microbiota influences the tumor microenvironment via miRNA-targeted epigenetic regulation, promoting activated MC infiltration in tumor metastases. Specifically, has-miR-3943 appears to be the target of most microbial genera, including Porphyromonas and Bifidobacterium spp. [85]. In pancreatic cancer, Zhang et al. [86] highlighted the potential role of the intratumoral microbiome in regulating the tumor immune environment. This regulation includes promoting marked intratumoral MC infiltration [86].

In gastrointestinal tumors, bacterial strain-specific signatures, particularly from Campylobacter species, correlate with high levels of active MCs in metaplastic tissues, contributing to Barrett’s esophagus progression [87]. Interestingly, in certain cancers, the gut microbiome-MC crosstalk may enhance antitumor immunity and therapeutic efficacy. Kaesler et al. [88] demonstrated in vivo that gut-derived LPS can activate MCs within and around melanomas. This activation enables MCs to recruit tumor-infiltrating effector T cells through C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) secretion, enhancing tumor immune control [88]. Chronic systemic inflammation is a key substrate of prostate cancer and is linked to factors such as a high-fat diet, which induces gut dysbiosis. In this pathogenic cascade, an altered gut microbiota interacts indirectly with immune cells, including MCs, which contribute to local inflammation and prostate cancer progression. Unlike its protective role in melanoma, elevated LPS levels from dysbiosis are implicated in the gut-prostate axis, driving prostate cancer progression. This effect occurs by upregulating histidine decarboxylase (Hdc), the gene encoding the enzyme responsible for histamine biosynthesis in prostate tumor-infiltrating MCs, which promotes histaminergic signaling and local inflammatory changes [89, 90].

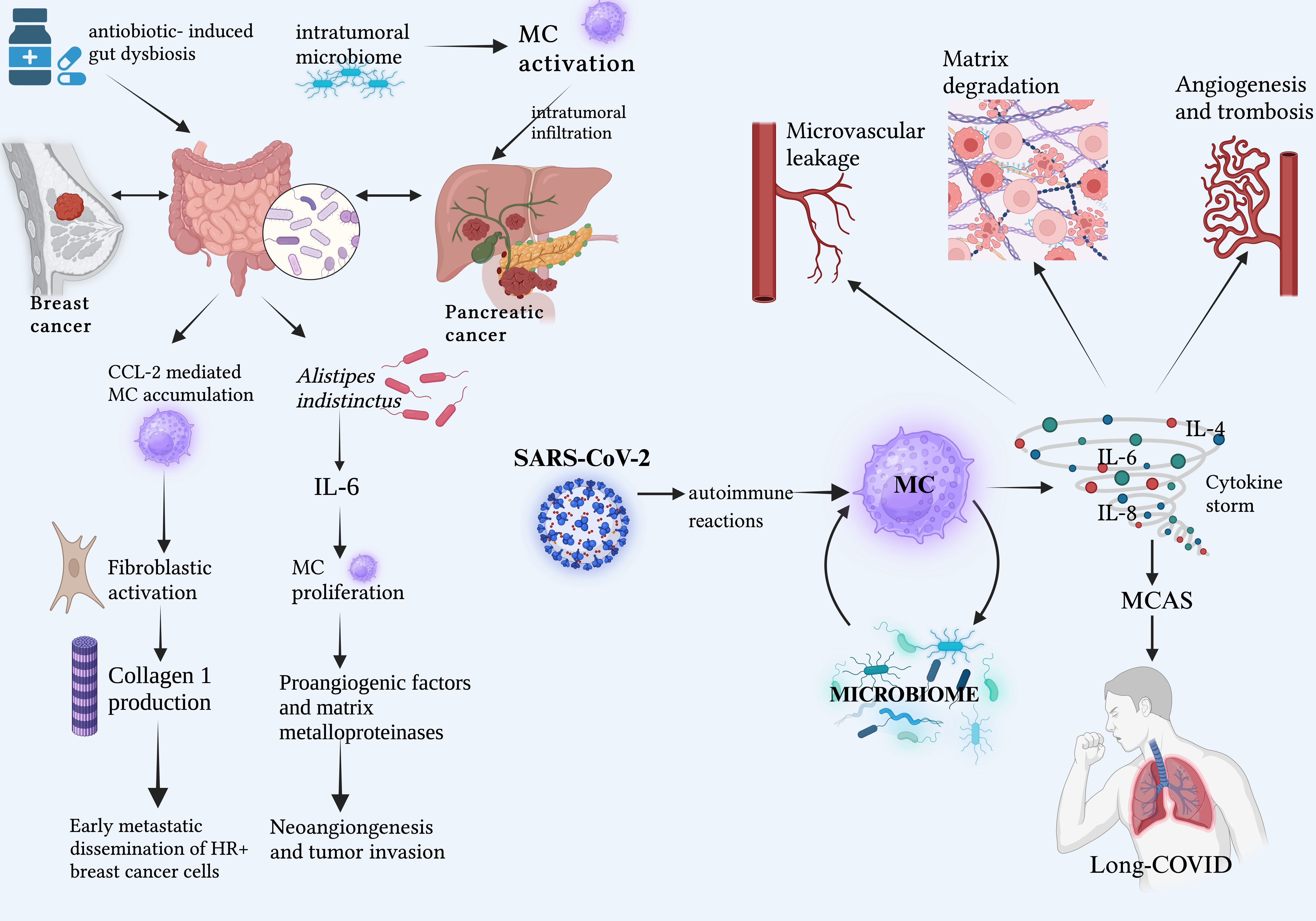

Pandemic threats from several animal-to-human viruses have been common in the last few decades. These include Zika virus, H1N1, Marburg, Monkeypox, Ebola, and betacoronaviruses such as SARS-CoV-1 (2003), MERS-CoV (2012), and SARS-CoV-2 (2019). SARS-CoV-2, in particular, has had an overwhelming global impact [91, 92]. MCs and basophils play critical roles in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Basophils drive the antibody response, while MCs form the first line of defense against SARS-CoV-2, contributing to a hyperinflammatory environment and triggering the cytokine storm. Through histamine release, MCs overexpress IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, and other proinflammatory cytokines, leading to lung hyperinflammation, microvascular leakage, matrix degradation, angiogenesis, and pro-coagulation [93]. Alterations in the host microbiota appear to significantly impact “long-COVID” or “Post-COVID syndrome” (PCS). PCS often progresses in close association with mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS). Specifically, SARS-CoV-2 infection can trigger autoimmune reactions that activate MCs, causing hyperinflammation and MCAS, which, in turn, mediate PCS symptoms [94, 95]. Given these pathophysiological considerations and the potential complexity of interactions between microbiota and dysfunctional MCs in MC activation disease, altered microbiota-MC crosstalk during SARS-CoV-2 infection may contribute to the PCS-MCAS link [96] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Crosstalk between microbiota and MCs in cancers and COVID. Highlights of emerging etiopathogenic scenarios related to the dysfunctional cross-talk between the host microbiota and MCs, which may be a prerequisite for the enhanced growth and spread of specific cancers, as well as the onset of severe inflammatory responses such as “cytokine storm” and long-COVID. Abbreviations: CCL-2, C-C motif chemokine ligand 2; IL, interleukin; MC, mast cells; MCAS, mast cell activation syndrome; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Created with BioRender.com.

Understanding the complex mechanisms of this interaction between the human microbiome and MCs in both physiological and disease-related contexts holds significant clinical potential across various medical fields. In gastroenterology, combining probiotics and MC stabilizers shows promise as a therapeutic strategy for managing functional gastroenteropathies, particularly IBS, by addressing visceral hypersensitivity (VH). Further investigations are needed into microbial histamine production and the signaling mechanisms involved in pro-serotoninergic crosstalk that causes diarrhea and abdominal pain. Additionally, blocking TLR4 signaling in IBS may offer new therapeutic options, as suggested by preliminary research [97, 98]. In hepatology, a deeper understanding of the gut-liver axis could lead to innovative management strategies for liver disorders. The increasing knowledge of epigenetic mechanisms that govern the immunoregulatory function of microbial-derived SCFAs suggests that gut microbiome manipulation as a new multidisciplinary therapeutic frontier. In neurology, the tolerogenic potential of microbial-derived AhR ligands warrants scientific attention, alongside therapies aimed at blocking MC-induced intestinal dysbiosis to improve stroke outcomes.

In dermatology, the intricate crosstalk between cutaneous and gut microbiomes and MCs is essential for balanced immune responses, preventing excessive inflammation and protecting against autoimmune conditions [18]. The gut-skin axis highlights the complex link between AD and systemic conditions, where gut dysbiosis promotes a Th2-skewed immune response, exacerbating AD flares and other Th2-mediated diseases, particularly food allergies, and also emotional disorders [60, 61, 99]. Targeting S. aureus in the AD cutaneous microbiome and balancing gut microbiota with probiotics show therapeutic potential in reducing AD severity and flare-ups. The hygiene hypothesis further suggests that early microbial exposure, modulated through MCs, could lower AD onset by promoting immune tolerance [18, 100, 101].

In allergology, advancing knowledge of microbiota-related MC immunoregulation may support preventive strategies against the atopic march. Investigating the local interactions between MCs and the airway microbiome in asthma, especially given changes in the lung microbiome composition in asthmatics, is also essential [102]. Furthermore, the gut microbiome’s role in modulating drug metabolism could help predict antihistamine therapy efficacy in patients with MC-driven CSU [78].

In light of the increasing prevalence of long-COVID, understanding dysfunctional MC-microbiota interactions may provide new management strategies for PCS-associated MC activation disease [103]. Finally, in oncology, new insights into MC-microbiome crosstalk offer prognostic, preventive, and therapeutic potential. In breast cancer, maintaining a healthy gut microbiome may prevent pro-fibrogenic MC phenotypes and reduce metastatic tumor cell spread [81]. In CRC, gut microbiome composition could serve as predictive markers for disease staging, with prognostic implications [82]. For pancreatic cancer, understanding the intratumoral microbiome’s impact on the tumor immune environment could lead to novel therapeutic approaches for managing this challenging malignancy [86].

Going beyond the classical conception of immune and microbial compartmentalized cell functionality, this overview emphasizes the critical role of human microbiota-MC crosstalk in maintaining the delicate balance between health and disease. In this context of inter-kingdom communication, the emerging insights suggest promising new clinical approaches for managing globally prevalent, chronic diseases. We believe that these findings merit further in-depth investigation by the international scientific community.

Conceptualized and designed the study: MDG and SG; data acquisition and interpretation: VP, FLP, RM, and FB; drafted the manuscript: VP and FLP; revised the manuscript: VP, FLP, MDG, RM, FB and SG; sorted out the figure: VP, FLP; supervised the study: MDG and SG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Given his role as the Guest Editor, Sebastiano Gangemi had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Amedeo Amedei.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.