1 Genetics and Epigenetics Research Group, Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, University of Otago, 6021 Wellington, New Zealand

2 Mātai Hāora - Centre for Redox Biology and Medicine, Department of Pathology and Biomedical Science, University of Otago, 8011 Christchurch, New Zealand

Abstract

The genomic landscape of cancer cells is complex and heterogeneous, with aberrant DNA methylation being a common observation. Growing evidence indicates that oxidants produced from immune cells may interact with epigenetic processes, and this may represent a mechanism for the initiation of altered epigenetic patterns observed in both precancerous and cancerous cells. Around 20% of cancers are linked to chronic inflammatory conditions, yet the precise mechanisms connecting inflammation with cancer progression remain unclear. During chronic inflammation, immune cells release oxidants in response to stimuli, which, in high concentrations, can cause cytotoxic effects. Oxidants are known to damage DNA and proteins and disrupt normal signalling pathways, potentially initiating a sequence of events that drives carcinogenesis. While research on the impact of immune cell-derived oxidants on DNA methylation remains limited, this mechanism may represent a crucial link between chronic inflammation and cancer development. This review examines current evidence on inflammation-associated DNA methylation changes in cancers related to chronic inflammation.

Keywords

- inflammation

- cancer

- epigenetics

- DNA methylation

- oxidative stress

The link between chronic inflammation and cancer is well established, however, the molecular mechanisms connecting these processes remain unclear. Disruptions in the integrity or expression of tumour suppressor genes and proto-oncogenes significantly contribute to cancer initiation and progression [1]. Although mutational events in cancer are well-researched, the role of epigenetic modifications in disease onset and development is less understood and remains an active area of investigation. In cancers associated with chronic inflammation, common epigenetic alterations include hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters and global hypomethylation of oncogenes [2]. During inflammation, immune cells release oxidants in response to pathogens or irritants and prolonged exposure to these oxidants in chronic inflammation can damage surrounding cells. However, the subtler impacts of oxidants, particularly on epigenetic processes, are less understood. This review examines the evidence for a mechanistic link between oxidants and altered DNA methylation patterns in the context of chronic inflammation and cancer.

Epigenetics is the study of heritable gene expression changes that occur without altering the underlying DNA sequence [3]. DNA methylation, the most extensively studied epigenetic modification, involves the addition of a methyl group to the 5th carbon of the pyrimidine ring in cytosine-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, resulting in the modified base 5-methylcytosine [4]. DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) facilitate this process by binding to CpG sites and catalysing the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) [5]. Typically, methylated DNA leads to gene silencing by blocking transcriptional proteins, including RNA polymerase, from binding [6]. Additionally, methylated DNA can recruit methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins that direct the assembly of transcriptional complexes, such as histone deacetylases and chromatin remodeling proteins, leading to condensed, inactive chromatin [7, 8].

DNA methylation patterns are largely established during embryonic development and remain stable throughout the cell’s life, with approximately 60–80% of methylated CpG sites found within gene bodies in humans [9]. However, a subset of CpG regions display dynamic methylation levels and are influenced by factors including age [10], diet [11, 12], smoking [13], exercise [14], drug use [15], and alcohol consumption [16]. One of the most dynamic regions are CpG dense regions known as ‘CpG islands’. CpG islands are genomic features tightly associated with gene promoters and generally exist in an unmethylated state, which allows for open chromatin that is accessible for transcription [17].

DNA demethylation is crucial for maintaining biological functions, including gene regulation, cell differentiation and genomic stability [18, 19, 20]. This process is mediated by distinct DNMT enzymes, each with specific biological functions. DNMT1 maintains methylation patterns during cell division by recognising hemimethylated DNA and adding methyl groups to the nascent strand, ensuring faithful inheritance of methylation patterns across cell divisions [21]. DNMT3a and DNMT3b catalyses de novo methylation adding new methylation groups during cell division [22], while DNMT2 methylates transfer RNA, impacting protein translation [23].

Demethylation can be passive or active. Passive demethylation occurs when DNMT1

fails to methylate a nascent daughter strand, or if SAM synthesis pathways are

disrupted [24]. Active demethylation is mediated by the ten-eleven translocation

(TET) protein family (TET1, TET2, TET3), which oxidises 5-methylcytosine to

5-hydroxymethyl cytosine (5-hmC) using molecular oxygen, iron (Fe(II)), and

Cancer fundamentally arises from cumulative genetic changes that enable abnormal cell behavior. These changes, summarized in the “hallmarks of cancer”, include sustaining proliferative signals, evading growth suppressors, resisting cell death, achieving replicative immortality, accessing blood supply, activating invasion and metastasis, reprogramming metabolism, avoiding immune detection, genome instability and mutation and tumour-promoting inflammation [28].

Chronic inflammation is characterised by prolonged immune cell activation and release of inflammatory molecules that persist after the initial threat has subsided [29]. Chronic inflammation can arise from factors such as persistent infections [30], autoimmune disorders [31], long-term exposure to irritants [32]and unresolved acute inflammation. In these conditions, immune regulation fails, and the mechanisms that would typically resolve the inflammatory response fail. This continuous immune activity harms surrounding tissues due to the sustained presence of cytotoxic molecules [33, 34].

The interplay between inflammation and cancer is complex and context-dependent [35, 36]. While acute inflammation can recruit cytotoxic T cells that target abnormal cells and may counteract cancer, chronic inflammation in established tumors often promotes progression. Continuous signalling within the tumor microenvironment exacerbates growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis [37, 38]. Inflammation can also be triggered by toll-like receptor (TLR) activation by microbial components, with varying effects. For example, TLR4 can promote intestinal tumors, while TLR2 appears protective in colitis-associated cancer [39, 40, 41].

Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins-6 and 8 (IL-6 and IL-8), tumour

necrosis factor alpha (TNF-

Under non-inflammatory conditions, reactive oxygen species (ROS) play an important role in modulating cell signalling pathways and in the regulation of homeostasis [45]. However, immune cells release a range of oxidants during the immune response, whereby they can exert cytotoxic effects [46]. Oxidative stress arises when the generation of oxidants surpasses the cell’s antioxidant defences [47]. Prolonged exposure to oxidative stress can damage DNA, alter the function of lipids and proteins, and activate transcription factors that up-regulate or down-regulate key molecular pathways [48]. Oxidants can directly react with DNA bases, forming adducts that cause mutations and base pair mismatches [49]. They can also induce double stranded breaks and cross-links that alter DNA structure and function, ultimately leading to genomic instability, mutations and chromosomal aberrations [50].

Oxidative stress is implicated in several disease states including every stage of carcinogenesis [51]. Cancer cells exhibit abnormal redox homeostasis, and maintaining high levels of oxidants along with immune infiltration that supports tumour cell proliferation [52]. While oxidative stress is damaging to normal cells, cancer cells adapt by upregulating antioxidant defences, enabling them to thrive under increased oxidative conditions [51].

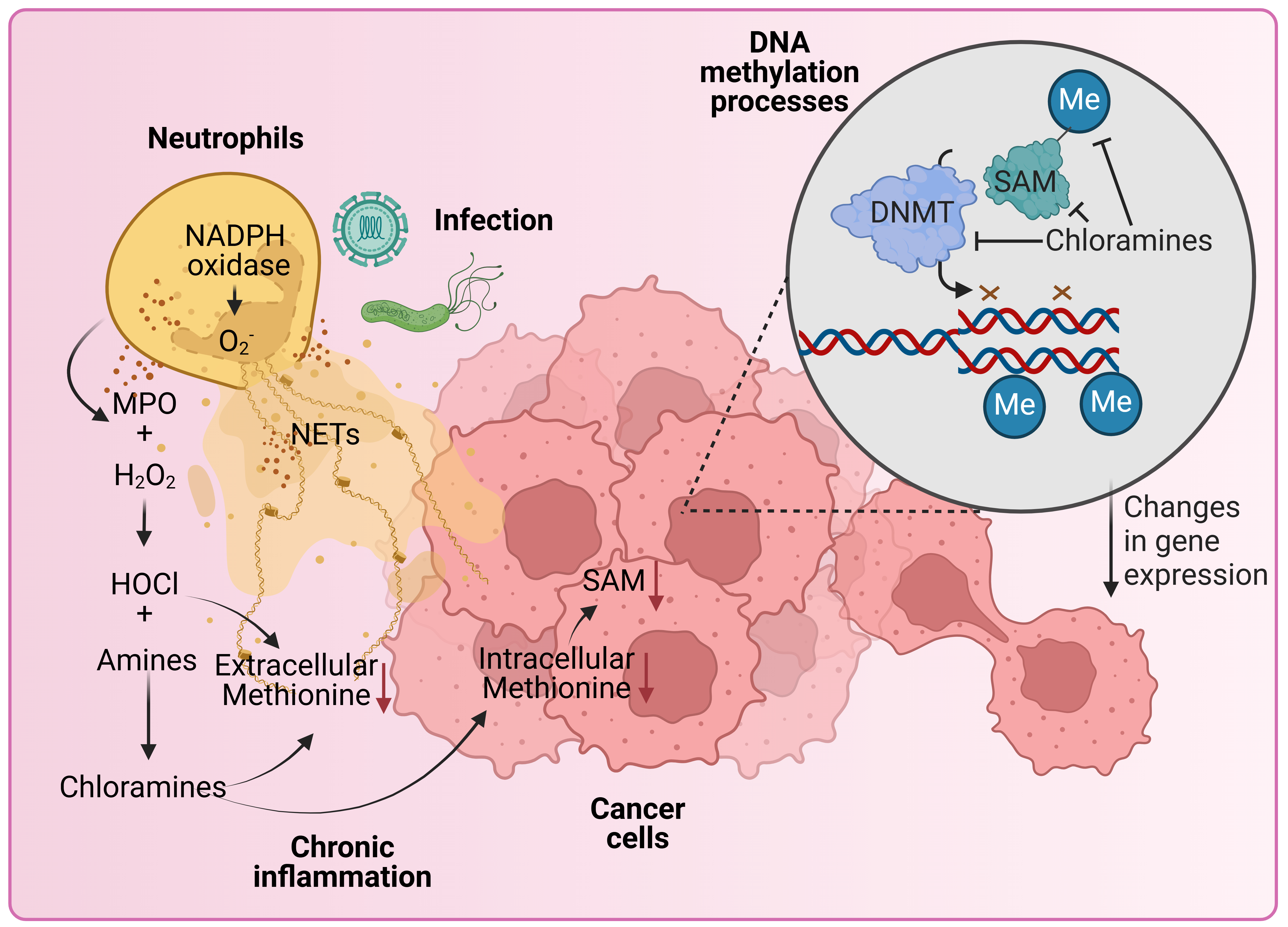

Neutrophils, the most abundant immune cell, are a major source of ROS during the immune response. The production of superoxide (O2–) occurs inside the neutrophil phagosome through the action of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAPDH) oxidase 2 (NOX2) as part of a process known as the respiratory burst (Fig. 1) [53]. O2– spontaneously dismutates to form hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), that can further react with intracellular chloride ions to form hypochlorous acid (HOCl) [54] via the neutrophil enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO). HOCl readily reacts with amines to yield chloramines, which have a greater diffusion rate and are longer-lived compared to other oxidants [55, 56]. Under certain conditions, neutrophils can form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), that are mesh-like structures containing DNA, histones and peptides capable of trapping and degrading pathogens [57]. Oxidants derived from NOX2 are involved in the signalling cascade leading to the NET formation and the release of oxidants into the extracellular environment, where they contribute to immune defence and can influence the surrounding tissue microenvironment [58].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Hypothetical model where neutrophil-derived oxidants participate in the regulation of epigenetic processes in cancer. Neutrophils are our most abundant white blood cell and can make up a large proportion of tumour infiltrate. Once stimulated, neutrophils assemble the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase and make superoxide (O2–), which spontaneously dismutates into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). H2O2 is used by the heme enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO) to make hypochlorous acid (HOCl). This process can be invigorated by the presence of secondary stimuli such as bacteria. Depending on the stimuli, neutrophils may also extrude neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) that contain MPO. MPO attached to NETs is active and can convert H2O2 from other sources, such as tumours, into HOCl. HOCl is a short-lived oxidant that can deplete methionine and reacts with amines to form chloramines. Amine groups are found on many physiologically important amino acids and can be derived from dietary sources. Chloramines are long-lived, some are cell permeable and are effective at depleting methionine, an essential component for the formation of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). SAM is the major methyl donor for the maintenance of epigenetic marks on DNA and histones. When methionine and SAM are depleted, DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are unable to maintain the fidelity of methylation on nascent strand DNA during replication. Failure to maintain DNA methylation as the cell divides can have consequences for gene expression and subsequent cell function. This could lead to the acquisition of tumour survival traits and more invasive phenotypes. Figure created with biorender.com.

Oxidants can disrupt epigenetic regulation [56], with consequences for genomic stability and cancer development. Global DNA hypomethylation, particularly of oncogenes [59], is linked to increased mutation rates, genomic instability, and activation of carcinogenic pathways, while hypermethylation in CpG islands of tumor suppressor promoters is associated with gene silencing and impaired cell cycle control [60].

Oxidative damage can alter DNA bases, producing lesions such as 8-hydroxyl-2-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG), 8-hydroxyguanine (8-oxoG), and O6-methylguanine, which are common in cancer and can interfere with DNA methylation patterns during DNA synthesis [61, 62]. For example, an in vitro study demonstrated that 8-oxoG can physically block DNMT1 from transferring methyl groups to neighbouring CpG sites. O6-methylguanine, further contributes to DNA hypomethylation by inhibiting DNMT binding and pairing incorrectly with thymine [63, 64].

Oxidant-induced hypomethylation may also result from DNMT1 inhibition. For example, glycine chloramine (GlyCl), produce through the reaction of HOCl with glycine [65, 66], can oxidize the DNMT1 active site and deplete the SAM precursor methionine, leading to a global decrease in DNA methylation and subsequent differential gene expression [65]. In studies with GlyCl-treated tissue cell lines, hypomethylation was enriched in cancer and inflammation-associated genes and concentrated at chromosomal ends, suggesting effects on chromosome stability and telomere length, both of which are common in cancer [66, 67] (Fig. 1). Significant genome-wide DNA methylation changes were also observed when T-lymphoma cells were exposed to sublethal levels of H2O2, which persisted after several rounds of cell division. This implies that oxidative stress can contribute to epigenetic heterogeneity often observed in the tumour microenvironment, which could have implications for long-term changes in gene expression [68]. Similarly, the reaction of HOCl with cytosine can result in the formation of 5-chlorocytosine, which mimics 5-methylcytosine and misguides methylation-sensitive proteins, leading to inappropriate methylation [69]. This results in the inappropriate methylation of habitually unmethylated CpG sites [70] and has been linked to promoter hypermethylation and gene silencing, such as observed in the hamster hprt gene [71].

Blocking the reduction of Fe(III) to Fe(II) through the exposure to H2O2 may reduce TET activity, and consequently 5-hmC [72], which has been observed in cells exposed to H2O2 over several days [72]. The conversion of 5-mC to 5-hmC by acetylated TET enzymes may normally protect against oxidative stress induced hypermethylation [73]. However, recent evidence suggests that oxidative stress may also alter TET enzyme function and thereby dysregulate DNA demethylation processes. In this instance, exposure to NaAsO2 (arsenic containing compound) was found to induce oxidative stress and inhibit the activity of TET enzymes and subsequent demethylation processes in lung cells [74]. 5-hmC quantification by dot-blot and cell imaging has revealed that global 5-hmC levels are lower in some inflammation-associated cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma and skin cancer, when compared with adjacent healthy tissues [75]. Corresponding TET gene expression in these tumours is also decreased, suggesting these epigenetic patterns are likely TET-mediated [75].

In this section, we explore aberrant DNA methylation patterns in cancers with strong associations with chronic inflammation. Although many other cancers are linked to chronic inflammation (summarised in Table 1, Ref. [76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115]), we have focused on those with both well-documented connections to sustained inflammatory states and significant epigenetic modifications, highlighting the critical role of inflammation in driving epigenetic changes during tumorigenesis.

| Inflammatory condition | Associated malignancy |

| Chronic pancreatitis | Pancreatic carcinoma [76, 77, 78] |

| Chronic gastritis | Gastric carcinoma [79, 80, 81] |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and chronic ulcerative colitis) | Colorectal carcinoma [82, 83, 84] |

| Chronic/recurrent urinary tract infection and cystitis | Bladder carcinoma [85, 86] |

| Gingivitis and periodontal disease | Oral squamous cell carcinoma [87, 88] |

| Chronic bronchitis | Lung carcinoma [89, 90] |

| Barrett’s oesophagus | Oesophageal carcinoma [91, 92, 93] |

| Skin inflammation | Melanoma [94, 95, 96] |

| Mononucleosis (glandular fever) | B-cell non-Hodgkins lymphoma and Burkitt’s lymphoma [97, 98, 99] |

| Hepatitis | Hepatocellular carcinoma [100, 101] |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | Ovarian carcinoma [102, 103] |

| Chronic cholecystitis | Gall bladder cancer [104, 105] |

| Cholangitis | Cholangiocarcinoma [106, 107] |

| Endometriosis | Ovarian carcinoma [108, 109] and endometrial carcinoma [110, 111] |

| Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | Thyroid cancer [112, 113] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Multiple myeloma [114, 115] |

Hepatitis C infection and hepatocellular carcinoma are strongly linked, and it

is possible that alterations in epigenetic patterns might predispose this common

form of liver cancer [116]. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a single-stranded RNA

virus that replicates in hepatocytes. Infection induces a CD8 + T cell response,

but in many cases the response is not successful in clearing the virus, resulting

in chronic inflammation [117]. Additionally, HCV proteins induce activation and

further increase oxidant levels and inflammatory responses, including

NF-

It has been observed that oxidant exposure can mediate the bidirectional regulation of several genes that code for enzymes related to de novo methylation in hepatocellular carcinoma. In particular, one study demonstrated the effect of H2O2 on DNA methylation levels in the promoter of E-cadherin [6], a tumour suppressor gene responsible for maintaining epithelial integrity and tissue architecture [121]. Loss of E-cadherin expression may be a key driver of metastasis due to the depletion of cellular adhesion mechanisms [122]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, H2O2exposure up-regulated the expression of the transcription factor ‘Snail’, which recruited key enzymes involved in closed chromatin-associated epigenetic modification to E-cadherin: Histone deacetylase 1, DNMT1 and methyl CpG binding protein 2 [123, 124]. This was correlated with E-cadherin silencing and inactivation of its function as a tumour suppressor [6]. It has also been observed that H2O2 exposure can increase levels of 8-oxo-dG in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines, causing hypermethylation of 11 specific tumour suppressor genes involved in human hepatocarcinogenesis [125]. Furthermore, increased levels of 8-oxo-dG were strongly correlated with the presence of repressive histone markers and an overall state of condensed chromatin [125].

H. pylori infection is strongly associated with the development of gastric cancer [126]. Chronic gastritis, caused by persistent inflammation due to H. pylori infection, can lead to alterations in the gastric mucosa, setting the stage for intestinal metaplasia and subsequent neoplastic transformation [127, 128]. The mucosa in H. pylori induced gastritis has increased levels of neutrophils, macrophages and inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and interleukins [129], accompanied by the release of oxidants that are known to cause genomic and epigenomic instability in gastric epithelia [126]. In H. pylori-infected Mongolian gerbils, hypermethylation was observed in gastric mucosae from infected animals, which correlated with the duration of infection [130]. H. pylori eradication led to a decrease in DNA methylation levels at specific genes, however, hypermethylation levels persisted even after H. pylori eradication [131].

Demethylation agents such as 5-Aza-2-deoxycytidine have been shown to reduce methylation induced by gastritis and prevent gastric cancer in gerbils [130]. Interestingly, gastritis-induced hypermethylation was inhibited upon treatment with an immunosuppressive agent, suggesting that H. pylori-induced inflammation was an important factor in the induction of aberrant DNA methylation [132, 133]. In a complementary study, it was shown that H. pylori infected macrophages co-incubated with gastric epithelial cells were able to yield a significant amount of nitric oxide, which induced methylation at the RUNX3 gene through a presumably, unknown mechanism. These findings were supported by similar methylation changes following lipopolysaccharide exposure and the inhibition of nitric, which blocked these effects [134].

In human studies, individuals infected with H. pylori show significantly higher methylation levels across various genes in the gastric mucosa compared to uninfected individuals with gastric cancer [135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140]. Cell pathways likely to be affected in H. pylori-induced hypermethylation are cell adhesion genes (CDH1, VEZT, Cx32) [135, 136, 137], cell cycle regulators (CDKN2A) [138], DNA mismatch repair genes (MHL1) [139], and inflammation genes (TFF2, COX-2) [138, 140]. These epigenetic changes contribute to the disruption of normal cellular functions, promoting a microenvironment conducive to carcinogenesis.

The gastrointestinal tract hosts a complex community of microorganisms and is exposed to various chemical agents through diet. Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are characterised by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and are highly associated with an increased risk of colitis-associated colorectal cancer (CAC) [141]. Like sporadic colorectal cancer, CAC develops due to genetic and epigenetic changes accumulated in dysplasia-associated lesions of the mucosa [142]. One study using a mouse model of colitis found that it led to an increase in intestinal tumours, reflective of how chronic inflammation in human IBD can promote cancer development [143]. Mice with inflammatory bowel disease exhibit oxidant-induced accumulation of 8-oxo-dG in colon epithelial cells, suggesting oxidants are abundant in the intestinal inflammatory environment [144]. In support of this, MPO and calprotectin have shown promise as faecal biomarkers of IBD, indicating that MPO is abundantly present and implies that other MPO-derived oxidants may be present in the IBD microenvironment [145, 146]. It has been shown that the methylation profile of tumours in CAC vs sporadic colorectal cancer (CRC) differ, which suggests that inflammation may play a key role in DNA methylation patterning [142]. Additionally, many genes have been shown to be differentially methylated in IBD patients compared to control patients [147]. IBD is further associated with serrated polyps in the bowel, which can develop into serrated polyposis syndrome (SPS), a condition characterised by multiple serrated lesions in the colon that are at a high risk for becoming cancerous. In a study that performed methylome analysis on SPS samples vs normal mucosa, it was found that the gene promoters HLA-F, SLFN12, HLA-DMA and RARRES3 were hypermethylated [148]. It was concluded that HLA-F hypermethylation is a novel biomarker candidate for SPS, and from a clinical viewpoint may be useful for identifying IBD patients that are more likely to develop the condition [148].

The role of oxidative stress in colorectal cancer progression has been illustrated in studies using human colorectal cancer cell lines and colitis models. Treatment of a human colorectal cancer cell line with H2O2 led to the upregulation of DNMT1 [149]. This increased the binding of DNMT1 to HDAC and presumably increased methylation in the promoter of the tumour suppressor gene, RUNX3, a gene that is commonly silenced across multiple different cancers [149]. This effect was reversed by treatment with the oxidant scavenger, N-acetylcysteine, suggesting that oxidants silenced RUNX3 expression via an epigenetic mechanism that may be associated with the progression of colorectal cancer [149]. Furthermore, oxidative stress induced by H2O2 in a mouse colitis model caused recruitment of DNMT1 to damaged chromatin, and also delocalised proteins involved in a repressive polycomb complex (DNMT1, histone deacetylase (sirtuin-1), and histone methyltransferase) from a non-CpG-rich region to CpG island-containing promoters carrying 8-oxo-dG [149]. These findings suggest that the oxidative stress induced by H2O2 could cause relocalisation of a silencing complex to oxidative damaged areas of tumour suppressor genes, and explain a mechanism for aberrant DNA methylation correlated with DNA damage and transcriptional silencing [150].

Skin cancer has one of the most well-established relationships with

environmental exposures, with ultraviolet (UV) radiation accounting for

approximately 75% of melanomas and 90% of non-melanoma skin cancers [151].

Epidemiological and experimental evidence indicate that chronic inflammation is a

key process in skin cells upon UV exposure, with key inflammatory mediators such

as NF-

DNA methylation changes in response to UVB radiation in mouse skin epidermis have been observed, including changes in the expression of genes that are known to be involved in skin carcinogenesis [153]. For instance, melanoma patients often display hypermethylation of promoters in several tumour suppressor genes including p16, E-cadherin, APC and TNF [154]. Conversely, DNA hypomethylation is thought to be related to melanoma pathogenesis, as the melanoma antigen gene is associated with decreased levels of methylation [155].

During the response to oxidative damage, hypermethylation occurs at genes linked to an increased risk of melanoma. Elevated oxidant levels in melanocytes have been associated with upregulation of DNMT1 and DNMT3b, leading to widespread promoter hypermethylation, thereby suggesting a connection between oxidative stress and changes in DNA methylation within melanoma [156]. Further studies have shown that carcinogenic processes in melanoma are greatly decreased by substances that have oxidant inhibiting qualities, such as genistein [157] and curcumin [158]. Genistein, in particular, has been shown to regulate DNA methylation pathways and affect tumour-related gene expression [159]. Additionally, melanocyte deadhesion, a key process in melanogenesis, results in both an increase in superoxide anion levels and DNMT1 production, leading to hypermethylation across multiple gene promoters [160]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that UVA induces the production of oxidants that cause DNA damage, including 8-OHdG [161], making it plausible that such oxidative damage would lead to alterations in the methylation profiles of exposed skin cells.

The high incidence of inflammation-associated cancers highlights the importance of understanding the molecular mechanisms that drive carcinogenesis. Although links between inflammation and cancer are established, the specific role of oxidants in altering DNA methylation patterns has received limited attention. Consequently, our understanding of the molecular processes linking oxidative stress and inflammation-related cancer remains incomplete, leaving unanswered questions about whether the DNA methylation changes induced by oxidants are causal or merely correlative. Aberrant DNA methylation patterns could act as primary drivers of carcinogenesis or represent secondary changes resulting from other cellular processes. Regardless, characterising these changes will aid in the development of biomarkers for disease development and progression. Due to their reversible nature, epigenetic factors also offer promising targets for precision therapies, potentially improving clinical outcomes.

Future research should prioritise identifying mechanisms behind oxidant-induced DNA methylation changes and exploring therapeutic strategies to counteract them. This focus will enhance both prevention and treatment outcomes for inflammation-associated malignancies. While many studies have examined the effect of oxidative stress, DNA methylation and inflammation as separate factors in cancer pathology, few have integrated them into a cohesive molecular pathway. Investigating this interplay could reveal novel insights and therapeutic opportunities in the field of cancer research.

OD, ARS, AJS and DK made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work. OD wrote the original draft, and all authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Additionally, ARS, AJS and DK provided funding and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Funding was provided from the Canterbury Medical Research Foundation and the Wellington Research Foundation: Research for Life.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.