1 Department of Pharmacy, Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province, 310012 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Abstract

It is known that the transformation of liver cancer-mediated fibroblasts into cancer-related fibroblasts (CAFs) is beneficial to the development of liver cancer. However, the specific mechanism is still unclear.

Human hepatocarcinoma (HepG2) cells were treated with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) of platelet-derived growth factor-D (shPDGF-D) vector, and the exosomes secreted by the cells were separated using ultracentrifugation and identified by using nanoparticle tracking analysis, transmission electron microscope, and western blot analysis. Exosomes were co-cultured with mouse primary fibroblasts, and then the activity, proliferation, cell cycle, migration, epithelial-mesenchymal transition- (EMT-) and CAF marker-related protein expression levels of fibroblasts were determined by cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8), immunofluorescence, flow cytometry, wound healing, real-time reverse transcription-PCR, and western blotting assays, respectively. Co-cultured fibroblasts were mixed with HepG2 cells and injected subcutaneously into mice to construct animal models. The size and weight of xenograft tumor and the expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition- (EMT-), angiogenesis- and CAFs marker-related proteins were detected.

The exosomes inhibited the proliferation, migration, EMT, and induced cell cycle arrest, as well as decreased the expression of α-SMA, FAP, MMP-9, and VEGF in fibroblasts. In vivo, sh-PDGF-D inhibited tumor growth, reduced the expressions of CD31, vimentin, α-SMA, FAP, MMP9, and VEGF, and promoted the expression of E-cadherin.

Exosomes derived from HepG2 cells transfected with shPDGF-D prevent normal fibroblasts from transforming into CAFs, thus inhibiting angiogenesis and EMT of liver cancer.

Keywords

- liver cancer

- exosomes

- cancer-associated fibroblasts

- platelet-derived growth factor-D

Liver cancer is one of the common tumors with the highest mortality at present [1]. The metastasis contributes to poor prognosis of patients with liver cancer, suggesting that early intervention for liver cancer metastasis is particularly important. It is found that the tumor microenvironment (TME) provides a good internal environment for the occurrence, development, and metastasis of liver cancer [2]. Fibroblasts are the classical supporting cell types, which were activated in response to the process of neoplasia. In the TME, the definition of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) can be simply viewed as fibroblasts that are located within a tumor [3]. The CAFs in TME can boost the invasion and metastasis of liver cancer cells by secreting cytokines and reconstructing the tumor microenvironment [4]. Although there are many sources of CAFs, including activated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, etc., CAFs can be identified by specific markers, such as

Exosomes are small vesicles secreted by cells with a diameter of 30–100 nm and wrapped by double lipid membranes [5]. They can regulate cell behavior by transmitting genetic information or functional proteins, so they are important mediators of communication between cells, such as tumor cells and CAFs [6]. CAFs are the main mesenchymal cells in TME and an important source of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), growth factors, chemokines, etc. [7]. It is found that stromal cells can receive exosomes from cancer cells, help cells to excrete cytotoxic drugs to induce drug resistance, regulate endothelial cell characteristics to promote angiogenesis and regulate epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to promote invasion and metastasis, thus creating a microenvironment to promote tumor growth [8]. It has been proven that tumor-derived exosomes can induce CAF activation and foster lung metastasis of liver cancer [9].

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-D belongs to the PDGFs family, which is overexpressed in multifarious cancers and participates in a series of cellular events, including proliferation, migration, invasion, blood vessel growth, etc. [10]. In addition, PDGF-D can also promote the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts [11]. Of note, Massimiliano Cadamuro et al. [12] found that cholangiocarcinoma cells secrete PDGF-D to recruit liver myofibroblasts to promote tumor lymphangiogenesis in cholangiocarcinoma. This suggests that PDGF-D may play a certain role in mediating the transformation of normal fibroblasts into CAFs.

Therefore, in the current study, we sought to explore the role and mechanism of exosomes secreted by HepG2 cells transfected with PDGF-D specific short hairpin RNA (shPDGF-D) on the transformation of normal fibroblasts to CAFs.

Human liver cancer cell line HepG2 (HB-8065, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM (11965092, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, 10091, Thermo Fisher, USA), 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin Solution (15140-122, Thermo Fisher, USA) in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C, and validated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination using MycoSensor PCR assay kit (Agilent, Hangzhou, China).

Human shPDGF-D (NM_025208.5, target sequence: 5′-ATCAAGAACGAACCAAATTAA-3′) lentiviral vector and its negative control (NC, target sequence: 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTCC-3′) were purchased from VectorBuilder (Guangzhou, China). In short, the vector was transfected into 293T cells with Lipofectamine™ 3000 (L3000150, Thermo Fisher, USA), and the transfection efficiency was assessed using a fluorescence microscope (BX53, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) 24 hours after transfection. The cell supernatant was collected and filtered, and the filtered virus was then infected with HepG2 cells. After 48 hours, the expression of PDGF-D was detected by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and Western blotting.

Briefly, total RNA was extracted by Trizol reagent (B511311, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). Next, the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan) was used to synthesize the cDNA of each sample. The expression of PDGF-D,

| Genes | Oligonucleotide sequences (5′ |

| PDGF-D | Forward 5′-GAGCAATCACCTCACAGACTTG-3′ |

| Reverse 5′-TTCCAGTTGACAGTTCCGCA-3′ | |

| Forward 5′-GGCATCCACGAAACCA-3′ | |

| Reverse 5′-TTCCTGACCACTAGAGGGGG-3′ | |

| FAP | Forward 5′-GATTCATGGGCCTCCCAACA-3′ |

| Reverse 5′-CTAACCTCCTGAGCCCTCCT-3′ | |

| GAPDH | Forward 5′-GGCAAATTCAACGGCACAGT-3′ |

| Reverse 5′-TGAAGTCGCAGGAGACAACC-3′ |

PDGF-D: platelet-derived growth factor-D; α-SMA: alpha -smooth muscle actin; FAP: fibroblast activation protein; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Total protein was extracted using RIPA Lysis Solution (P0013K, Beyotime, China). The extracted protein has gone through the process of electrophoresis. After incubating with the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, the membrane was washed with TBST buffer and incubated with the secondary antibody for 2 hours at room temperature. The protein bands were visualized by ECL Western Blotting Substrate (PE0010, Solarbio, Beiijng, China) and quantified using the Image J software (1.52v, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), with GAPDH serving as the internal control. The primary and secondary antibodies were as follows: PDGF-D (DF12690, 1:1000, Affinity, West Bridgford, UK); CD63 (1:1000, ab217345, Abcam, Fremont, CA, USA); CD81 (1:1000, ab109201, Abcam); CD9 (1:1000, ab92726, Abcam);

The separation of exosomes is described previously by sequential centrifugation [13]. In short, the HepG2 cells were cultured in a DMEM medium containing 10% exosomal-free FBS. After 48 hours, the supernatants from cells were centrifuged at 300 g for 10 minutes to discard cells, and then the supernatant was centrifuged at 16,500 g for 20 minutes to remove cell debris. The supernatant was filtrated using a 0.22 µm syringe filter and then centrifuged at 120,000 g (Beckman Type 90 Ti) for 70 minutes to precipitate exosomes. Finally, the exosome pellet was resuspended in PBS or lysis buffer before further analysis. In order to verify the exosomes, a nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA, ZetaView PMX 120) was carried out to estimate the size distribution and nanoparticle concentration of the exosomes, the morphology of the exosomes was observed by using a transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEM-1400, JEOL, Akishima, Japan), and the specific markers of the exosomes (CD63, CD81 and CD9) were detected by western blot.

BALB/C mice (20–30 g) were acquired from Vital River (Beijing, China) and kept in a constant temperature (21

All animal experiments were permitted by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of Hangzhou Eyong Pharmaceutical Research and Development Center (Approval number: EYOUNG-20201030-02) and in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Laboratory Animal Care and Use Guidelines.

The fibroblasts were placed in a 6-well plate at a density of 1

Fibroblasts (2

The proliferating fibroblasts were determined by the EdU Kit (C0075, Beyotime, China). In short, the prepared EdU working solution was added to the above-mentioned 6-well plate for 48 hours of co-cultivation and incubated for 2 hours, then the culture solution was removed and 1 mL of fixing solution was added for fixation for 15 minutes. Then, after removing the fixing solution, cells were reacted with the permeating solution for 15 minutes and with a click reaction solution for 30 minutes. Then Hoechst 33342 solution was added to stain the nucleus. Finally, the results were observed under a fluorescence microscope (BX63, Olympus, Japan).

To detect the expression of E-cadherin, vimentin,

Cell Cycle Kit (C1052, Beyotime, China) was used to detect the cell cycle. In short, the co-cultured cells were collected and centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 minutes. After removing the supernatant, the cells were resuspended with PBS (E607008, Sangon, China) and transferred to the centrifuge tube. Precooled 70% ethanol was added and incubated at 4 °C for 30 minutes. After washing, the configured propidium iodide (PI) staining solution was added and incubated in the dark for 30 minutes. Finally, the cell cycle was detected by flow cytometry.

A long scrape was created by a pipette, and PBS was used to remove detached cells on the surface. Afterward, the cells were incubated with DMEM in the incubator for 24 hours. The wounds were photographed at 0 and 48 hours by a microscope (BX53M, Olympus, Japan).

BALB/C nude mice (20–30 g) were also purchased from Vital River, and housed in a constant temperature (21

Statistical analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The results were expressed by mean

To evaluate the effect of PDGF-D, we transfected HepG2 cells with shPDGF-D, and the transfection efficiency was shown in Fig. 1A,B (p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Identification of exosomes in HepG2 cells with silencing of PDGF-D. (A,B) Relative expression of PDGF-D in HepG2 cells transfected with specific shRNAs against PDGF-D. Data are represented as mean

The exosomes of HepG2 cells with PDGF-D knockdown were co-cultured with mouse primary cultured fibroblasts, and the effects of exosomes derived from HepG2 cells on the biological behavior of fibroblasts were evaluated through a series of functional experiments. Compared with the Exos-NC shRNA group, exosomes derived from HepG2 cells transfected with shPDGF-D inhibited the cell viability and proliferation of fibroblasts (Fig. 2A,B, p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Knockdown of PDGF-D in HepG2-derived exosomes inhibited the proliferation of fibroblasts. (A) Fibroblasts were incubated with exosomes in HepG2 cells with silencing of PDGF-D for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, respectively. Cell viability was analyzed by cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. (B) EdU assays of Fibroblasts incubated with exosomes in HepG2 cells with silencing of PDGF-D were performed to evaluate cell proliferative ability. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Cell cycle distributions of fibroblasts in PDGF-D knockdown HepG2-derived exosomes were presented by flow cytometry. Results are represented as mean

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Knockdown of PDGF-D in HepG2-derived exosomes inhibited the migration of fibroblasts. (A) Wound healing assays were performed in fibroblasts treated with exosomes in HepG2 cells with silencing of PDGF-D. Scale bar, 200 μm. (B) Immunofluorescent analysis for E-cadherin and Vimentin was detected in fibroblasts. Nuclei were stained blue (DAPI), and E-cadherin and Vimentin were stained red, Data are shown as mean

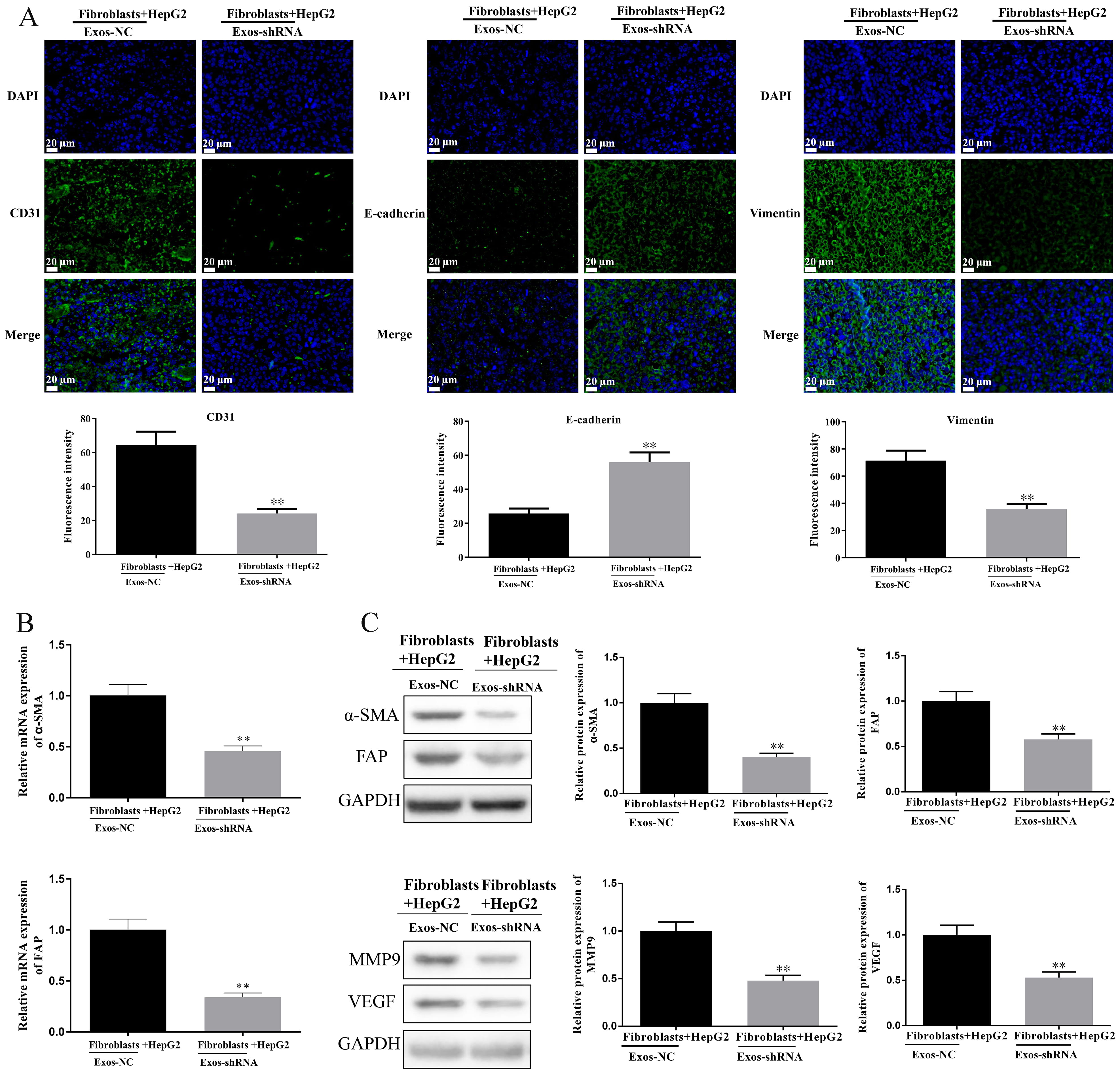

The conversion of fibroblasts to CAFs is related to the EMT process, and activated fibroblasts have the ability to promote invasion and angiogenesis. Therefore, we evaluated the expression levels of EMT-related proteins, CAF markers, MMP-9, and VEGF. As shown in Fig. 3B, exosomes secreted by HepG2 cells transfected with shPDGF-D could significantly increase the expression of E-cadherin in fibroblasts (p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Knockdown of PDGF-D in HepG2-derived exosomes regulates

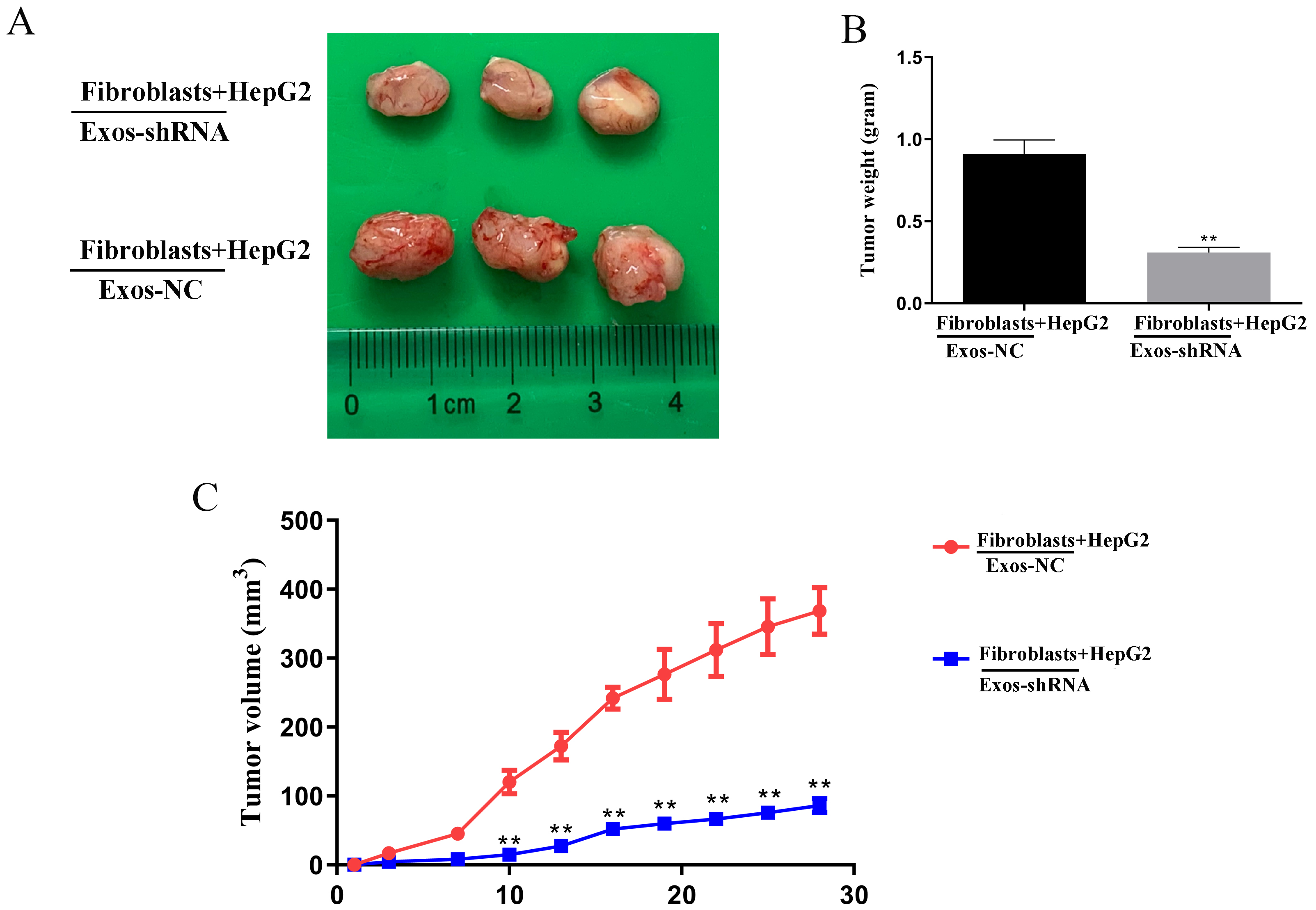

To further verify our conclusions, we carried out in vivo experiments. The results showed that compared with the Exos-NC group, the tumor size and volume of mice injected with HepG2 cells and fibroblasts (co-cultured with exosomes secreted by HepG2 cells transfected with shPDGF-D) were significantly reduced (Fig. 5A–C, p

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Knockdown of PDGF-D in HepG2-derived exosomes suppresses the growth of Liver cancer tumor in vivo. (A) Representation images of tumor tissues of nude mice. Compared with the vector group, the (B) tumor weight and (C) volume significantly reduced in Knockdown of PDGF-D in HepG2-derived exosomes-treated fibroblasts and HepG2 cells in nude mice. Data are shown as mean

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Knockdown of PDGF-D in HepG2-derived exosomes regulates CD31, E-cadherin, Vimentin,

CAFs are mainly derived from activated normal fibroblasts and exhibit invasion and migration ability. Studies have shown that the activation process of normal fibroblasts mediated by tumor cells is closely related to exosomes [15]. Exosomes derived from tumor cells can not only reprogram normal fibroblasts into CAFs by transmitting miRNA but also induce normal fibroblasts to transform into CAFs by transmitting protein [16]. Ringuette et al. [17] found that the exosomes derived from bladder cancer cells carry transforming growth factor beta (TGF-

PDGF-D can stimulate angiogenesis and extracellular matrix deposition, which is closely related to the development of cancer. It has been proved that PDGF-D has crosstalk with multiple signaling pathways such as cell survival and growth, EMT, invasion, angiogenesis, etc. [20]. Borkham-Kamphorst et al. [21] found that PDGF-D can activate hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts, thereby promoting liver fibrosis. It is worth noting that both hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts are sources of CAFs, and there has been evidence that PDGF-D enables hepatic myofibroblasts to promote tumor lymphangiogenesis in cholangiocarcinoma, which means blocking PDGF-D may be a way to hinder the cancer-promoting effect of CAFs [12]. Consistent with the previous studies, we found that exosomes shPDGF-D regulated the viability, proliferation, migration, and cell cycle of fibroblasts, thereby hindering the activation of fibroblasts.

Common downstream effectors of PDGF-D include EMT-associated proteins (E-cadherin, vimentin), MMP-9 and VEGF, etc. [20], and the activation of fibroblasts is also related to the occurrence of EMT [22]. The acquisition of invasiveness by liver cancer cells through the process of EMT is a key driver of the malignant progression of hepatocellular carcinoma [4, 23]. EMT down-regulates the expression of the epithelial marker, E-cadherin, and up-regulates the expression of the mesenchymal epithelial marker, Vimentin, which results in the acquisition of a mesenchymal phenotype by the epithelial cells and confers on the hepatocellular carcinoma cells the ability to detach from the primary tumor site and metastasize to a distant location [23]. Therefore, the phenotype of hepatocellular carcinoma cells as epithelial or mesenchymal can be determined by the levels of E-cadherin and Vimentin, which can help to understand the degree of EMT of tumor cells. Additionally, MMP-9 is an important factor for cancer cell invasion. It has been found that down-regulation of PDGF-D in renal cell carcinoma cells and gastric cancer cells reduces the invasion and angiogenesis of cancer cells by inhibiting the expression of MMP-9 in cancer cells [24, 25]. VEGF regulates the process of angiogenesis, and it has been shown that down-regulation of PDGF-D inhibits the expression of VEGF in gastric cancer cells and thus affects the development of gastric cancer [25]. In addition, Fan et al. [26] reported that exosomes derived from lung cancer cells increased the expression of VEGF and MMP-9, thereby promoting the transformation of fibroblasts to CAFs. These evidences showed that PDGF-D can promote the transformation of fibroblasts into CAFs by regulating the expression of E-cadherin, vimentin, MMP9 and VEGF, which is consistent with our research results. Moreover, the decrease of

Tumor cells stimulate fibroblasts to transform into CAFs by secreting exosomes, while CAFs secrete cytokines like MMP and TGF-

Studies have shown that cardiotrophin-like cytokine factor 1 (CLCF1), which is derived from CAFs in liver cancer, causes cancer cells to secrete more chemokine ligand 6 (CXCL6) and TGF-

In summary, our research proves that exosomes derived from HepG2 cells transfected with shPDGF-2 prevent normal fibroblasts from transforming into CAFs, thus inhibiting angiogenesis and EMT of liver cancer.

The data set used and analyzed in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

JCX contributed the design of the study. YYW and LSYY contributed to perform in vitro and in vivo experiments and write article. YYW and HYZ contributed to analyze experiment data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The manuscript was approved by the Committee on Experimental Animals of Hangzhou Eyong Pharmaceutical Research and Development Center (Approval number: EYOUNG-20201030-02) and was in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Laboratory Animal Care and Use Guidelines.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.