1 Department of Neurosurgery, Third Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, Shanxi Bethune Hospital, Shanxi Academy of Medical Sciences, Tongji Shanxi Hospital, 030032 Taiyuan, Shanxi, China

2 Department of Neurosurgery, Chongqing General Hospital, 400799 Chongqing, China

3 Department of Neurosurgery, Shanxi Bethune Hospital, Shanxi Academy of Medical Sciences, Tongji Shanxi Hospital, Third Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, 030032 Taiyuan, Shanxi, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), a severe cerebrovascular disorder, is principally instigated by the rupture of an aneurysm. Early brain injury (EBI), which gives rise to neuronal demise, microcirculation impairments, disruption of the blood-brain barrier, cerebral edema, and the activation of oxidative cascades, has been established as the predominant cause of mortality among patients with SAH. These pathophysiological processes hinge on the activation of inflammasomes, specifically the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3)and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) inflammasomes. These inflammasomes assume a crucial role in downstream intracellular signaling pathways and hold particular significance within the nervous system. The activation of inflammasomes can be modulated, either by independently regulating these two entities or by influencing their engagement at specific target loci within the pathway, thereby attenuating EBI subsequent to SAH. Although certain clinical instances lend credence to this perspective, more in-depth investigations are essential to ascertain the optimal treatment regimen, encompassing dosage, timing, administration route, and frequency. Consequently, targeting the ensuing early brain injury following SAH represents a potentially efficacious therapeutic approach.

Keywords

- subarachnoid hemorrhage

- early brain injury

- inflammasome

- NLRP3

Spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), a grave cerebrovascular afflication, is induced by the rupture of brain aneurysms and is typified by the abrupt emergence of intense headache, modified states of consciousness, and neurological impaorments. The incidence of spontaneous SAH is conspicuous, and its concomitant mortality and disability rates are a matter of significant apprehension. As per prevalent statistical data, the mortality rate spans from 25% to 50% [1]. In the initial phases subsequent to SAH, localized hemorrhage and disrupted cerebral perfusion can precipitate acute impairment within the central nervous system (CNS), thereby triggering a sequential series of pathophysiological alterations [2]. Early brain injury (EBI) designates the acute damage to the CNS transpiring within 72 hours post-SAH and constitutes a principal determinant in the augmented mortality rates and the manifestation of delayed neurological deficits [3]. Consequently, interventional modalities directed at alleviating EBI have emerged as a core area of research, with the aim of augmenting the prognoses of patients with SAH.

In recent times, inflammasomes, especially the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, have captured substantial attention from investigators. Research has established that inflammasomes play a substantial role in EBI following SAH, and their activation is intimately correlated with the aggravation of neuroinflammation. Precisely, in monocytes isolated from SAH patients, the expression levels of NLRP3 and active caspase-1 were markedly enhanced. The application of the inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 can efficaciously impede NLRP3 inflammasome overactivation and the consequent release of inflammatory factors, thereby ameliorating neuroinflammation [4]. Thus, probing the potential of inflammasomes as a therapeutic target may offer novel perspectives for early intervention following SAH.

Accordingly, this review zeroes in on the pertinent pathways implicated in the activation and modulation of inflammasomes, as well as nascent pharmacological strategies targeting these inflammasomes that exhibit clinical translational potential, thereby furnishing a theoretical underpinning for the evolution of novel therapeutic regimens, particularly interventions aimed at early inflammatory responses.

Extensive research has pinpointed two prominent complications related to SAH: delayed cerebral vasospasm (either accompanied by or without delayed ischemic neurological deficits) and aneurysm rebleeding. Both of these complications are pivotal elements that contribute to the deterioration of the prognosis for SAH. Delayed cerebral vasospasm, regarded as a type of secondary brain injury, typically manifests and assumes critical role in the aftermath of SAH. In contrast, rebleeding tends to occur within 72 hours following the initial rupture of the aneurysm [5].

Nevertheless, recent investigations have demonstrated that endeavors aimed at preventing delayed cerebral vasospasm have demonstrated proven to be ineffective in enhancing patient outcomes [6]. As a result, researchers have shifted their focus towards addressing EBI. The initial trauma ensuing from the rupture of aneurysms gives rise to rapid neuronal death, dysfunction within the microcirculation system, disruption of the protective blood-brain barrier (BBB), swelling of brain tissue, the initiation of oxidative reactions, and the activation of inflammatory responses. These processes subsequently trigger downstream pathways that are instrumental in the development of EBI [7].

Neuronal cell death within EBI encompasses diverse mechanisms, namely apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and autophagy [8]. Subsequent to SAH, neurons experience apoptosis through both endogenous and exogenous pathways.

The endogenous pathways are instigated by the activation of caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways, also recognized as the mitochondrial pathway. In this particular process, the release of cytochrome C from mitochondria into the cytoplasm activates caspase-9, which ultimately results in the activation of caspase-3 and consequently leads to neuronal apoptosis. The release of cytochrome C is modulated by the anti-apoptotic protein family Bcl-2 [9]. Moreover, aside from the pathways mentioned above, the intrinsic pathways also incorporate caspase-independent mechanisms such as the Apoptosis-Inducing Factor (AIF) pathway [10]. Mitochondrial damage disrupts the equilibrium between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant systems, giving rise to oxidative stress and eventually culminating in cellular death [11].

Apoptosis in extrinsic cells is initiated via cell membrane receptors, for instance, Fas, which belongs to the tumor necrosis factor receptor family. The activation of exogenous apoptotic pathways following SAH entails the upregulation of Fas by forkhead-box transcription factors, which then leads to the activation of caspase-8 or caspase-10. Once activated, Fas receptors bind with Fas-associated with death domain protein (FADD) to form the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC), which subsequently combines with pro-caspase-8 for activation. The active caspase-8 triggers the activation of caspase-3 or Bid/Bax, resulting in the release of cytochrome C and ultimately triggering neuronal apoptosis. In addition to inducing apoptosis through the activation of death receptors, Uncoordinated-5 homolog B receptor (UNC5B) and deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC) can also promote the dephosphorylation of caspase-9 or Death Associated Protein Kinase 1 (DAPK1), thereby initiating extrinsic apoptosis [12, 13].

Necroptosis represents an inflammatory modality of cell death that hinges on the expression of receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP-1), receptor-interacting protein 3 (RIP-3), and the pseudokinase domain of mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) [14]. The activation pathways of necroptosis are mediated by death receptors, among which tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNFR1) [15]. TNFR1 binds to its ligands to form survival complex I, which is composed of the receptor-interacting RIP-1, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated death domain protein (TRADD), and several ubiquitin E3 ligases [9]. During cylindromatosis, RIP-1 undergoes deubiquitinated [16], which prompts the formation of complexes IIa and IIb. Complex IIa activates caspase-8 and induce apoptosis. In the event that caspase-8 is inhibited, complex IIb is generated, thereby leading to the phosphorylation of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK-1) and the subsequent activation of receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK-3). Subsequently, RIPK-3 phosphorylates MLKL, which then disrupts cell membranes and culminates in necrotic apoptosis [17].

Pyroptosis serves as critical category of programmed necrosis, characterized by a significant inflammatory response that ensues upon infection with specific pathogens, such as Shigella flexneri [18]. The onset of pyroptosis entails the involvement of inflammasomes, which are cytoplasmic protein complexes typically composed of sensor proteins (for instance, the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein (NLRP) series or Absent in Melanoma 2 (AIM2)). These sensor proteins are responsible for detecting pathogen-associated molecular patterns.

The formation of inflammasome complexes prompts the recruitment of apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain (ASC). This recruitment, in turn, instigates the cleavage of procaspase-1, thereby activating caspase-1 [17]. Once activated, caspase-1 proceeds to cleave the precursor forms of Interleukin-1

Moreover, the activation of caspase-1 activation can also trigger the cleavage of gasdermin D (GSDMD). This cleavage leads to the creation of pores that are capable of directly penetrating the plasma membrane as well as other potential membranes. These pores then facilitate the flow of ions, ultimately culminating cellular lysis and death [19, 20].

Ferroptosis represents a specific form of cellular death that is instigated by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation. This process leads to a decline in the activity of Glutathione Peroxidase 4 (GPX4). As a consequence of this reduction, the antioxidant capacity within cells is diminished, and lipid ROS accumulate, ultimately culminating in cell death [21].

Concurrently, compounds such as RSL3 and FIN are capable of directly suppressing the enzymatic activity of GPX4. This suppression, in turn, gives rise to the intracellular accumulation of lipid peroxides and induces ferroptosis [22].

Furthermore, unbound ferric iron (Fe3+) receptor 1 interacts with engulfed cells and then undergoes a reduction from Fe3+ to ferrous iron (Fe2+), which is facilitated by STEAP3. In delicate cells, Fe2+ participates in three principal pathways: it can be stored in ferritin, transported out of the cells via the transmembrane protein ferroportin, or contribute to the production of lipoid ROS through the Fenton reaction. Ultimately, these processes trigger ferroptosis [23, 24, 25].

Autophagy, functioning as a cellular repair mechanism, entails the degradation of cytoplasmic components or entities by lysosomes with the aim of maintaining intracellular stability [26]. Lee et al. [27] have documented a substantial upregulation of neuronal autophagy in the early phases following SAH, which was found to be correlated with an augmented incidence of neuronal death.

Three principal autophagy pathways have been identified and characterized: macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) [28, 29]. In the context of macroautophagy, cellular materials are transported to the lysosomes for degradation through the formation of double-membrane autophagosomes [30]. Microautophagy, on the other hand, is initiated by signaling molecules that directly fuses with lysosomes [31]. During CMA, specific amino acid sequences prompt the substrate protein to bind to lysosome-associated membrane protein 2A (LAMP-2A), thereby resulting in its transportation to the site of lysosomal degradation [32].

During the occurrence of secondary brain injury subsequent to SAH, a significant alteration in the levels of key molecules is observed. Specifically, the level of nitric oxide (NO) undergoes a substantial reduced, whereas the concentration of Ca2+ experiences a marked increase [6, 33]. This imbalance has the potential to act as a mediator in the development of acute microvascular spasms [33, 34].

NO, an effective vasodilator, is synthesized through the catalysis of L-arginine by three isoforms, namely neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) [35]. NO triggers the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase, which is then followed by the subsequent activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. This activation cascade ultimately leads to the relaxation of smooth muscle [36].

Conversely, elevated levels of Ca2+ activate the intricate chain of myosin, thereby inducing constriction and spasms within the cerebral blood vessels [37]. After SAH, the release of hemoglobin consumes a considerable amount of NO, resulting in a rapid decline in its levels [38, 39]. Moreover, the downregulation or inhibition of eNOS and nNOS further curtails NO production in the post-SAH period [40]. The study has also noted that the levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous inhibitor of eNOS, increase significantly during cerebral vasospasm [41]. Additionally, when vasospasm occurs following SAH, iNOS becomes excessively activated, which leads to the impairment of the function of cerebral vascular smooth muscle cells and triggers vasoconstriction [42]. Consequently, therapeutic strategies that target NO may possess the potential to reverse SAH-related vasospasm.

The BBB is primarily constituted by tight junctions that are formed through the collective contribution of pericytes, brain microvascular endothelial cells, and astrocytic end feet, which are together referred to as the neurovascular units [43]. In the aftermath of SAH, the integrity of the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) is undermined via diverse mechanisms. These mechanisms encompass endothelial cell apoptosis as well as the disruption of tight junctions [44].

Oxidative stress, iron overload, oxyhemoglobin, and other factors are capable of inducing endothelial cell apoptosis within 24 hours of the onset of SAH [44, 45]. Furthermore, the activation of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) can initiate an inflammatory cascade that eventually leads to damage to the BBB [46, 47].

Substances traverse the BBB mainly through two routes: the paracellular route (via tight junctions) and the transcellular route (endocytosis mediated by caveolin-1 and clathrin-coated pits) [48]. Tight junction proteins, including occludin, zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), and claudin-5, undergo phosphorylation. This phosphorylation process governs their interaction, redistribution, and localization. It has been observed that the levels of caveolin-1 and claudin-5 remain relatively consistent following SAH. However, occludin and ZO-1 exhibit decreased expression during the initial phase [49]. Such findings suggest that the alterations in BBB integrity subsequent to SAH might be ascribed to the disruption of the paracellular pathway.

Following the occurrence of brain edema in the context of SAH, its progression exhibits a characteristic pattern. Specifically, the edema gradually increases within the initial 24 hours, experiences a rapid escalation after three days, reaches its primary peak on the 4th or 5th day, and then demonstrates a slower yet persistent growth until the 9th to 14th day, after which diminishes gradually [50].

Cerebral edema has traditionally been classified as either cytotoxic or vasogenic edema based on its pathophysiological features [51]. However, further research has indicated that cerebral edema could be more appropriately characterized as a process involving continuous cytotoxic, ionic, and vasogenic edema [52].

The primary mechanisms underlying cytotoxic edema during EBI are centered around functional disturbances in several key elements, namely the sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter 1 (NKCC1), aquaporin 4 (AQP4), and sulfonylurea receptor 1-regulated ATP sensitive nonselective cation channel (NCCa-ATP) levels. These functional disturbances disrupt the balance between extracellular sodium and water levels, thereby giving rise to cellular swelling. Intravascular sodium efflux prompts fluid extravasation while maintaining the integrity of the BBB, resulting in the accumulation of extracellular fluid, which is commonly referred to as ionic edema [53].

Consequently, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels increase in patients following brain injury, and excessive matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity contributes to the hyperpermeability of the BBB [54]. Furthermore, it has been observed that the activation of endothelin B receptor (ETB-R) triggers a transformation in astrocytes into reactive astrocytes. This transformation leads to the release of various factors associated with vascular permeability, such as MMP9 and VEGF-A, ultimately contributing to vasogenic edema [53].

Following SAH, mitochondrial function becomes impaired, and excessive free radicals are generated [55]. This impairment leads to an increase in the permeability of the mitochondrial membrane, resulting in the release of proteins, including cytochrome C, and accelerating the death of neuronal cells. Subsequently, a caspase- and Bax-mediated cascade of cellular apoptosis is triggered [11].

Moreover, damaged mitochondria are capable of generating ROS, which serve as potent activators of NLRP3 inflammasomes and other mediators of EBI. This activation initiates numerous detrimental pathways [56]. Additionally, the release of hemoglobin decomposition products induces free radical generation through the oxidative effects of oxyhemoglobin and free iron during SAH [57], thereby exerting a significant impact on oxidative cascades.

The levels of inflammasomes are substantially upregulated and reach their peak within 24 hours following SAH, which coincides with a marked increase in the expression of inflammatory cytokines. The early activation of inflammasomes can exert a profound influence on EBI, potentially due to the pronounced pro-inflammatory properties exhibited by these complexes in the post-SAH period. This mechanism plays a crucial role in preserving the integrity of tight junction, thereby alleviating cerebral edema, promoting microthrombosis, mitigating oxidative stress, delaying cerebral vasospasm, and enhancing functional recovery.

Inflammasomes are cytoplasmic multiprotein complexes that consist of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC) serving as an adapter protein, and caspase-1 acting as an effector protein. These complexes constitute essential elements within the innate immune system and are tasked with the identification of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [58].

Inflammatory complexes can be categorized into three principal types based on distinct PRRs. These include different subgroups of NLRs, inflammasomes activated by AIM2, and interferon-inducible protein16 (IFI16) [59, 60]. The NLR family is an important component of the innate immune response, which responds to cellular stress and injury signals. Proteins within the NLR family are composed of a central nucleotide-binding domain that forms part of the larger nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase (NACHT) domain, along with a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain. The NLR family can be further divided into multiple subtypes in accordance with the different N-terminal structures, such as the NLRP group. The NLR protein family encompasses 14 members, which are distinguished by the presence of a pyrin domain in the N-terminal region [61].

One of the most comprehensively investigated inflammasome subgroups is the NLRP3 inflammasome, which is composed of NLRP3, pro-caspase-1, and ASC. The crucial role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in EBI following SAH has been convincingly established in previous studies [62, 63]. Hence, delving into the specific mechanisms of the NLRP3 inflammasome holds significant importance for both understanding and treating the related diseases.

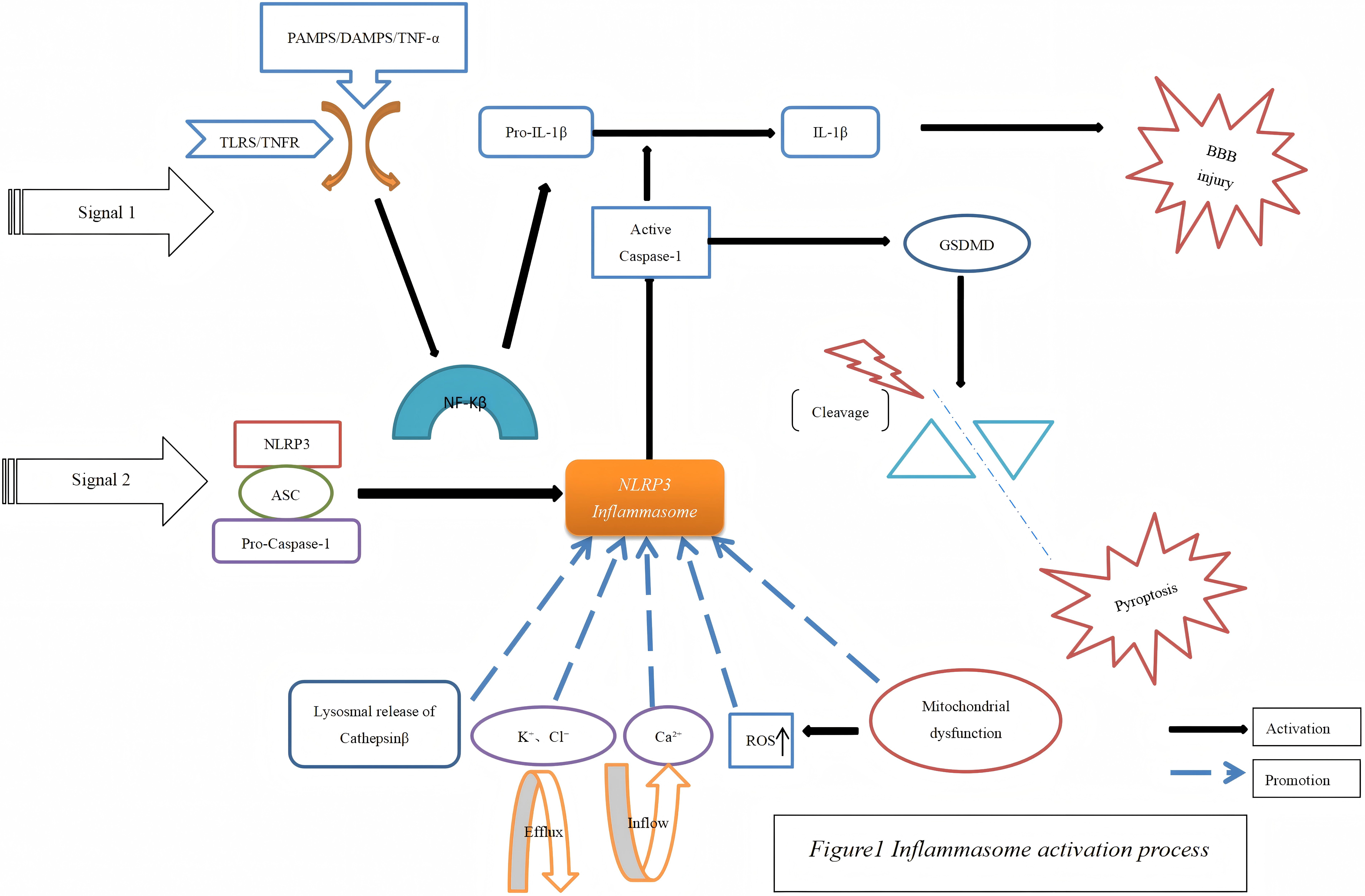

The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome occurs in two fundamental steps: the initial priming and the subsequent activation. During the priming phase, nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-

In the activation phase, activated NLRs initiate the sequential recruitment of ASC and pro-caspase-1, leading to their assembly into larger multiprotein complexes. These complexes then trigger the activation of pro-caspase-1 and facilitate the maturation process of both pro-IL-1

Moreover, the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is significantly influenced by the efflux of ions such as calcium, sodium, and chloride ions in conjunction with mitochondrial dysfunction [19, 20]. The activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome promotes inflammatory cell infiltration and the release of inflammatory cytokine. IL-1

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Inflammasome activation process. PAMPs, pathogen-associated molecular patterns; DAMPs, damage-associated molecular patterns; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin; BBB, blood-brain barrier; TLRS, toll-like receptors; TNFR, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1; GSDMD, gasdermin D; NF-

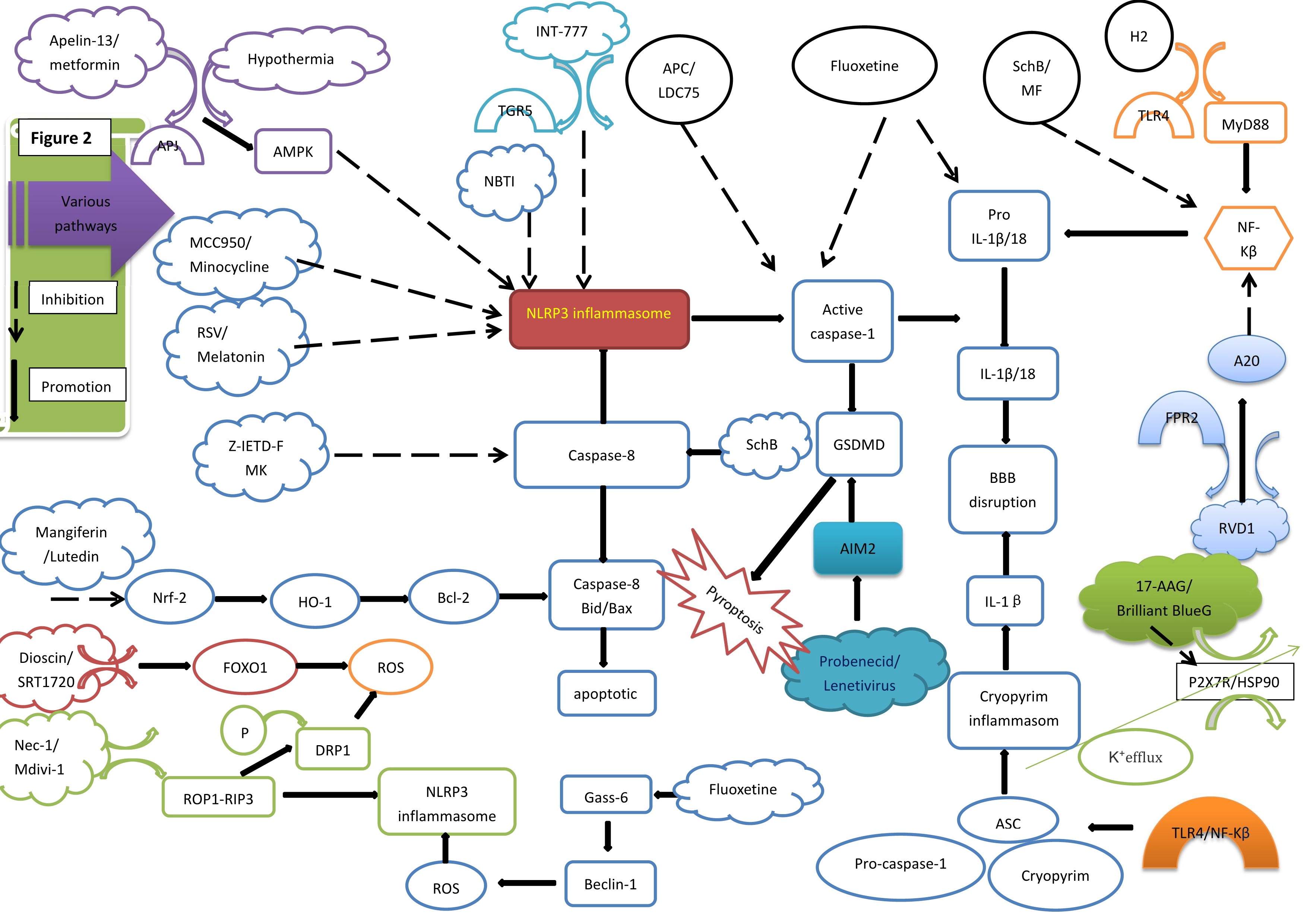

In recent years, a growing body of research has centered on the inflammasome and its affiliated pathways as prospective targets for the treatment of EBI following SAH. For example, both direct and indirect interventions aimed at the NLRP3 inflammasome, along with the regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome through signaling pathways such as NF-

Likewise, targeted interventions directed at the AIM2 inflammasome have been shown to specifically impede the progression of EBI after SAH (Table 1, Ref. [2, 3, 62, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91]).

| Model | Intervene | Signaling pathways | Molecular mechanisms | Other mechanisms | References |

| Rats/Mice | MCC950 | NLRP3 | Reduce ROS, NLRP3, IL-1 | Reduce cerebral edema, microthrombosis, cerebral vasospasm, apoptosis; | [66] |

| Maintain tight junction | |||||

| Rats | Minocycline | NLRP3 | Reduce, NLRP3, IL-1 | Reduce cerebral edema and apoptosis | [67] |

| Rats/Mice | Resveratrol/Melatonin | NLRP3 | Reduce, NLRP3, IL-1 | Reduce cerebral edema and apoptosis | [68, 69, 70] |

| Rats | Fluoxetine | NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1 | Reduce cerebral edema | [71] |

| Rats | Sch B | NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3, ASC, IL-1 | Reduce cerebral edema, apoptosis | [72] |

| Rats | ROS | NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1 | Reduce apoptosis and pyroptosis | [73, 74] |

| LDC7559 | |||||

| Rats | Sch B | TLR4/NF-κB NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3, ASC, IL-1 | Reduce cerebral edema, apoptosis | [72, 75] |

| Rats | H2 | TLR4/NF-κB NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1 | Reduce cerebral edema, apoptosis, oxidation, cerebral vasospasm | [90, 91] |

| Rats | Apelin-13 | AMPK/NLRP3 | Reduce TXNIP and NLRP3; | Reduce cerebral edema, apoptosis, oxidation | [62] |

| Enhance caspase-1, Bip, IL-1 | |||||

| Mice | Metformin | AMPK/NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1 | Reduce cerebral edema, apoptosis | [76] |

| Enhance AMPK phosphorylation | |||||

| Rats | Hypothermia | AMPK/NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1 | Reduce cerebral edema, pyroptosis | [77] |

| Enhance AMPK phosphorylation | |||||

| Rats | Luteolin | Nrf2/NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1 | Reduce apoptosis, pyroptosis, oxidation | [78] |

| Rats | Mangiferin | Nrf2/NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3/ASC, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1 | Reduce apoptosis, oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation reaction | [79] |

| Rats | INT-777 | TGR5/cAMP/PKA | Reduce NLRP3, IL-1 | Reduce apoptosis, oxidation, cerebral edema | [3] |

| NLRP3 | |||||

| Rats/Mice | SRT1720/Dioscin | SIRT1/NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3, IL-1 | Reduce oxidation, cerebral edema, pyroptosis, apoptosis | [2, 80] |

| Rats | Nec-1/Mdivi-1 | RIP1/RIP3/DRP1 | Reduce DRP1 phosphorylation and activation; | Reduce cerebral edema | [81] |

| NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3and cleaved caspase-1 | ||||

| Rats/Mice | MerTK/Fiuoxetine | NLRP3/ASC | Reduce NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1 | Enhance autophagy flux; | [82, 83] |

| Gas6 | Enhance Beclin1 | Reduce apoptosis, cerebral edema | |||

| Rats | ResolvinD1 | FPR2/A20 | Reduce NF-κB, NLRP3, IL-18, TNF- | Reduce BBB disruption and apoptosis | [84] |

| NLRP3 | Enhance IL-10 and A20 | ||||

| Rats | Brilliant | P2X7R/NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1 | Reduce cerebral edema | [85] |

| blue G | |||||

| Rats | ENT1 | ENT1/NLRP3/Bcl2 | Reduce NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1 | Anti-apoptosis | [86] |

| Mice | 17-AAG | HSP90/P2X7/NLRP3 | Reduce NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-1 | Reduce cerebral edema | [87] |

| Rats | Probenecid | P2X7R/AIM2/ASC | Reduce AIM, ROS, IL-1 | Enhance ATP release; | [89] |

| Reduce cerebral edema | |||||

| Mice | Lentivirus | AIM2/caspase-1/GSDMD | Reduce AIM2, caspase-1, caspase-3 | Reduce apoptosis and pyroptosis | [88] |

NLRP3, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3; IL, interleukin; Sch B, schisandrin B; ROS, reactive oxygen species; APC, Activated protein C; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase-recruitment domain; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; NF-

The NLRP3 inflammasome is of crucial significance in the progression of EBI after SAH. MCC950, as a selective inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome, impedes the ASC polymerization triggered by NLRP3. The inhibition curtails the formation of the inflammasome and consequently reduces the release of inflammatory cytokines. As a result, it safeguards the BBB and alleviates neurological dysfunction following SAH [66].

In contrast, minocycline suppresses the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, effectively diminishing the formation of the multi-protein complex consisting of ASC and pro-caspase-1. This, in turn, leads to a reduction in downstream caspase-1 activation. Consequently, minocycline can decrease the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1

A prior study demonstrated that fluoxetine can reduce the expression levels of NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1

The TLR4-mediated MyD88-IKK-NF-

The phosphorylation of TAK1 and TAB2 induces the release of this complex from the cell membrane. The active TAK1 further leads to the phosphorylation of I

The study has demonstrated that schisandrin B can inhibit the phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of p65.Thus, interfering with the activation of the NF-

AMPK serves as a crucial endogenous defense molecule, possessing the capacity to modulate cell apoptosis, pyroptosis, neuroinflammation, as well as mitochondrial dysfunction. The Apelin receptor (APJ), which is a G protein-coupled receptor, is the target through which Apelin-13 exerts its protective effect on the nervous system by activating AMPK.

Upon activation of AMPK, it leads to the phosphorylation and degradation of thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP). This, in turn, inhibits excessive endoplasmic reticulum stress and reduces the levels of NLRP3. Consequently, the levels of active Bip, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1

The administration of metformin following SAH can enhance neuronal protection and suppress the expression of NLRP3, cleaved caspase-1, IL-1

Nrf2 constitutes an important endogenous component that participates in maintaining cellular homeostasis. In the context of SAH, oxidative damage is initiated, which disrupts the endogenous antioxidant system. Subsequently, the Nrf2 protein undergoes translocation to the cell nucleus. Once in the nucleus, it binds to the antioxidant response element, thereby facilitating the transcriptional activation of crucial antioxidant genes such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and superoxide dismutase (SOD). This activation serves to counteract oxidative stress [93].

Luteolin (LUT) markedly enhances the localization of Nrf2 to the cell nucleus while significantly reducing the content of ROS following SAH-induced damage. Consequently, it provides protection against the damage caused by SAH. Moreover, an increased expression of Nrf2 inhibits the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway, thereby exerting an influence on subsequent events [78].

Methyl anthocyanidin (MF) exerts neuroprotective effects on early brain injury following SAH. Specifically, it leads to a reduction in the expression of NLRP3, ASC, and cleaved caspase-1, as well as the activation of NF-

Caspase-8, which is an aspartate-specific cysteine protease falling within the caspase family, plays a crucial role in the extrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway. Recent investigations have illustrated that caspase-8 assumes a pivotal position in linking the TLR4 and inflammasome signaling pathways during the production of IL-1

The administration of Z-IETD-FMK, a caspase-8 inhibitor, can significantly enhance neuroprotective effects and improve long-term neurological outcomes. This is because it effectively reduces the expression levels of NLRP3, caspase-1, and IL-1

TGR5 is a bile acid receptor positioned on the cell membrane and is expressed in astrocytes, neurons, and microglia. After SAH, the levels of the endogenous TGR5 receptor, phosphorylated protein kinase A (p-PKA), and NLRP3-ASC protein all increase. INT-777 treatment has the ability to upregulate the protein levels of TGR5, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), and p-PKA, while simultaneously downregulating the protein levels of NLRP3-ASC, IL-1

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Various pathways and NLRP3 inflammasome. AMPK, amp-activated protein kinase; RSV, Resveratrol; Nrf2, nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2; HO-1, Heme Oxygenase-1; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma-2; ROS, reactive oxygen species; P, phosphorylation; DRP1, dynamin-related protein 1; Nec-1/Mdivi-1, Necrostatin-1/mitochondrial division inhibitor; TGR5, trans-membrane G protein-coupled receptor-5; NLRP3, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3; APC, Activated protein C; SchB, Schisandrin B; AIM2, Absent in melanoma 2; IL, interleukin; GSDMD, gasdermin D; BBB, blood-brain barrier; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain; H2, hydrogen gas; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; NF-

SIRT1 belongs to the SIRTUIN family and functions as a histone deacetylase. It alleviates neurological damage by regulating oxidative stress and inflammation pathways that are mediated by forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1). As a transcription factor, FOXO1 plays a vital role in maintaining intracellular ROS stability. Overexpression of FOXO1 can enhance hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) clearance and increase oxidative stress resistance. Conversely, a reduction in FOXO1 exacerbates excessive ROS production and oxidative damage. SIRT1, acting as an upstream regulator of FOXO1, can be deacetylated by SRT1720 drugs. This deacetylation enhances FOXO1 binding to DNA and inhibits excessive ROS production, subsequently suppressing the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome after SAH [2]. The study has demonstrated that dioscin, an effective activator of SIRT1, can also significantly impede the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, the cleavage of caspase-1, and the subsequent inflammatory responses following SAH [80].

The RIP family encompasses serine-threonine protein kinases, including RIP1-4, and DRP1 is involved in regulating mitochondrial division. After SAH, activated astrocytes express RIP1, RIP3, and DRP1. Active RIP1 and RIP3 combine to form stable RIP1-RIP3 complexes, which then activate inflammasomes and trigger programmed cell death. Treatment with Nec-1 can reduce the expression of RIP1 and RIP3, inhibit the phosphorylation of DRP1, effectively alleviating mitochondrial damage, decreasing ROS production, downregulating NLRP3 inflammasome expression, and relieving the cerebral edema and neurological dysfunction induced by SAH. Moreover, Mdivi-1 treatment inhibits the expression of DRP1, mitigates mitochondrial damage and ROS production, suppresses the NLRP3 inflammasome, and improves cerebral edema and neurological dysfunction within 24 hours of SAH [81].

MerTK is a TAM protein expressed in macrophages. It binds to the endogenous ligand Gas-6 to suppress inflammatory responses. The mRNA levels of NLRP3 and caspase-1 are not significantly affected by the activation or inhibition of MerTK, suggesting that MerTK may inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome assembly by facilitating its degradation rather than through transcriptional repression in response to SAH-induced neuroinflammation. Gas-6 can further upregulate the expression of the autophagy marker Beclin-1, clear damaged mitochondria to prevent the release of mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) into the cytosol, and ultimately limit inflammasome assembly, thereby negatively regulating inflammasome activation [82]. This, in turn, promotes neural recovery and exerts protective effects. Fluoxetine treatment can also upregulate the expression of the autophagy marker Beclin-1, reduce NLRP3 expression, and trigger the cleavage caspase-1 to facilitate early brain injury recovery after SAH [83].

In the context of SAH, there is a reduction in the endogenous expression of resolvin D1 (RvD1), while the levels of zinc finger protein A20 and NLRP3 increase. This situation leads to the aggravation of neuroinflammation, disruption of the BBB, and the occurrence of cerebral edema. RvD1 is a lipid mediator derived from docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and exhibits significant anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects.

Its mechanism of action involves binding to the endogenous receptor formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2) and upregulating the expression of zinc finger protein A20. A20 can further inhibit the activation of NF-

The cytotoxic events induced following SAH can result in the accumulation of extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which has the potential to activate the P2X7R/cryopyrin inflammasome axis and trigger the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1

Firstly, the upregulation of TLR4/NF-

Following SAH, the expression of equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1) is upregulated. At the same time, the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated, and the levels of Bcl-2 are decreased. The intervention with the inhibitor NBTI can lower the expression of NLRP3 and BAX, thereby reducing the levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1

Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) is an important factor in the activation of P2X7R and participates in several pathological processes induced by SAH. For instance, SAH injury causes the upregulation of HSP90, which then activates P2X7R, stimulating the assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome and resulting in the production mature IL-1

AIM2 is composed of an N-terminal pyrin domain (PYD) and a C-terminal HIN-200 domain. The HIN domain has the ability to recognize abnormal dsDNA, which encompasses various types such as bacterial and viral DNA derived from pathogens and hosts, self-DNA originating from the cellular cytoplasm, damaged DNA within the nucleus, and self-DNA released via exosomes [96]. When DNA binds to it, theAIM2 PYD domain dissociates from the HIN domain, thus initiating downstream signaling. In the absence of the ligand (dsDNA), the HIN-200 domain interacts with the PYD domain to exert self-inhibition and prevent the assembly of the inflammasome [97].

The AIM2 inflammasome, which differs from the NLRP family, is predominantly expressed in neurons. The HIN-200 protein family incorporates ASC and caspase-1 proteins. Once activation, AIM2 recruits ASC to facilitate the cleavage of pro-caspase-1, which then triggers the assembly of an ASC-dependent inflammasome. This process ultimately leads to neuronal pyroptosis through the maturation of IL-1

Microglia, which serve as innate immune cells within the CNS, undergo rapid activation in response to SAH. Once activated, microglia can display two distinct phenotypes, namely the M1 and M2 phenotypes, each with different functions.

The M1 phenotype is characterized by inducing the synthesis of pro-inflammatory agents, facilitating the generation of ROS, and triggering the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [100]. In contrast, the M2 phenotype exerts anti-inflammatory effects through the release of anti-inflammatory regulators.

Over time, M1 microglia tend to become dominant in the injury area and intensify brain damage by exacerbating the inflammatory response. When stimulated by various signals, including ROS, the activated NLRP3 inflammasome initiates the activation of caspase-1. Caspase-1 then mediates the proteolytic cleavage of pro-inflammatory cytokines into their active forms, thereby amplifying the innate immune response. Moreover, activated caspase-1 can also induce pyroptosis, which further aggravates neuronal death [2].

Interventions that are targeted at blocking or inhibiting the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and restoring the balance of microglial polarization may potentially improve EBI following SAH.

Inflammasome activation is frequently observed in patients experiencing EBI after SAH. Early intervention during this stage is of crucial importance as it can significantly influence patient prognosis. Inflammasomes have been shown to be involved in multiple aspects related to EBI following SAH, such as neuronal cell death, microcirculatory dysfunction, disruption of the BBB, brain edema, and the neuroinflammatory responses. By implementing pharmacological interventions that target either the components of inflammasomes or their upstream regulators to reduce inflammasome expression, it is possible to impact the expression of various pro-inflammatory factors. This, in turn, can lead to the amelioration of EBI and improvement in the outcomes of patients after SAH.

Moreover, considering the diverse effects on ROS production, brain edema formation, apoptosis, pyroptosis, oxidative stress response, and autophagy that have been witnessed in different targets subsequent to BBB damage caused by SAH, it has become clear that drugs targeting these factors possess the potential to mitigate changes associated with EBI in SAH patients. Consequently, regulating inflammasome activity through drug intervention is essential for the treatment of EBI after SAH.

However, several significant challenges exist when it comes to targeting inflammasomes for therapeutic applications. One primary concern is the potential for off-target effects. Many drugs developed to target the NLRP3 inflammasome may not only act on NLRP3 but also interfere with other vital immune pathways, resulting in unintended side effects. These off-target effects can undermine the therapeutic efficacy and even give rise to new health problems.

Regulatory challenges also pose a substantial obstacle for inflammasome-targeted therapies. Given that inflammasomes play a critical role in a wide range of physiological and pathological processes, developing targeted therapies demands extensive clinical trials to guarantee their safety and effectiveness. Nevertheless, the current regulatory framework may lack the necessary flexibility to quickly adapt to emerging therapeutic approaches. This leads to a prolonged approval process and delays patients’ access to novel treatments.

The complexity and diversity of inflammasomes further complicate the development of targeted therapies. Additionally, the lack of patient-specific biomarkers restricts the application of targeted inflammasome therapies. The absence of reliable biomarkers for assessing inflammasome activity makes it difficult for clinicians to formulate treatment plans.

In summary, while targeted inflammasome therapies offer considerable clinical potential, numerous challenges remain, including off-target effects, regulatory barriers, the complexity of inflammasomes, and the lack of appropriate biomarkers. Only through continuous research and innovation can advancements be made in this field, with the ultimate goal of providing safer and more effective treatment options for patients.

XZ, CX, ZYL, DYZ, BHW, JW, and XMD contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by XZ and CX and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

We would like to thank all those who helped us during the preparation of this manuscript and all the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Initiation Fund for Talent Introduction of Shanxi Bethune Hospital, Shanxi Province, China (No. 2021RC006).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.