1. Introduction

Macrophages (M) are a heterogeneous population of innate immune cells that protect the host against foreign pathogens. M are a highly heterogeneous population of mononuclear white blood cells that phagocytose and modulate the innate immune response [1]. They are effective antigen-presenting cells (APCs), needed to bridge innate and adaptive immunity. M can regulate the immune response via phagocytosis of foreign/damaged material via recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), processing foreign material, and presenting antigens to CD4+ helper T cells via the major histocompatibility complex II (MHC-II) [2] as well as cross-presenting exogenous antigens to CD8+ T cells via MHC-I [3, 4, 5, 6].

M are highly plastic and can differentiate into a wide range of phenotypes depending on the cytokines in the environment, ranging from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive cells [7, 8, 9]. The latter phenotype was originally termed as alternatively activated M2 M [10] as their characteristics were very different from the classically activated M1 cells; however, these M1 and M2 designations are very general and a more specific inducer-based naming was suggested to reflect the specificity and diversity of phenotypes that exist under both general terms [9]. M2 polarization results in an anti-inflammatory condition to restore tissue homeostasis after the infection has been cleared, but can also promote pro-tumorigenic conditions [2].

Specifically, M2 M has since been further classified into M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d subtypes depending on the different stimulus and cell characteristics. For example, interleukin (IL)-4 can induce M differentiation into M2a, while certain toll-like-receptor (TLR) ligands, together with adenosine agonists can induce M2d. These two cell types, while sharing certain markers, can exhibit unique gene expression profiles, characteristic biomarkers, and cellular functions [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. M2d M are also commonly referred to as “tumour-associated macrophages” (TAMs) within the literature [14] as they infiltrate the tumour microenvironment (TME) and are critical in promoting cancer proliferation and metastasis. In general, they are considered immunosuppressive cells as they hinder T-cell activation, which allows for abnormal tumour cell growth [17].

In vitro, M0 M derived from bone marrow can develop into M2d M either via interleukin (IL)-6 mediated differentiation, or TLR activation via PAMP detection in combination with A2A adenosine receptor agonist [14]. Regarding the latter pathway, the concurrent activation with an A2A adenosine receptor agonist 5-(N-ethylcarboxamido) adenosine (NECA) plus lipopolysaccharide (LPS), results in the downregulation of inflammatory cytokines, promoting a switch to an M2d M phenotype [12]. However, these studies were confined only to cells treated for 24 h post differentiation. In our study, we investigated longer time points and compared bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) with spleen-derived M (SpM). The data illustrates that prolonged stimulation with LPS and NECA induces a more anti-inflammatory phenotype compared to short stimulation, via upregulation of arginase and downregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) together with a significant increase in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Macrophage Preparations from Animals

Mice were maintained under sterile conditions and were approved by Queen’s University Animal Care Committee (approval number: 2021-2173) and all experiments were performed following the Canadian Council of Animal Use guidelines. Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Bone marrow was harvested from the tibias and femurs of 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice (JAX laboratories, Canada) and flushed with PBS. Cells were then resuspended in red blood cell lysis buffer (1.66% w/v ammonium chloride; A-661, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA) at room temperature for 5 minutes before being cultured in 6-well plates. RPMI medium supplemented with 20% L929 cell-conditioned media (LCCM), 10% FCS (35-077-CV, VWR, Ontario, Canada) and 50 µg/mL gentamycin (GTA401.10, BioShop, Ontario, Canada), served as a source of macrophage colony stimulating factor (MCSF). The media was replaced on days 3 and 5 after removing non-adherent cells, and bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) were ready to use on day 7. Spleen-derived macrophages (SpM) were cultured for 7 days in MCSF-enriched media as previously reported [18].

To investigate different time points of polarization, we established short (S) and long (L) culture conditions—24 h and 48 h respectively—and investigated the phenotypes of both bone marrow and spleen M. On days 7 and 8 of culture, MCSF media was replaced with RPMI (10% FCS), and the corresponding stimulants were added to wells. Cells without treatment are referred to as unstimulated (UN). To induce an M2a M phenotype, cells were stimulated with rM-IL-4 (20 ng/mL; Shenandoah Biotechnology Inc., Warminster, PA, USA) as published previously and these cells are referred to as IL-4 (S) or IL-4 (L) [15, 19, 20]. To induce an M2d M phenotype, cells were stimulated with a combination of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from E.coli (100 ng/mL; Sigma Aldrich, Canada) and NECA (1 µM; Sigma Aldrich, Canada). NECA was referred to as NECA (S) while LPS is referred to as LPS (S) and LPS (L). M2d phenotype is referred to as LPS + NECA (L+N)(S) and L+N (L).

2.2 Microscopy

The morphology of polarized M derived from bone marrow and spleen was analyzed using light microscopy. Cells were seeded into 6-well culture plates and observed with a light microscope (Leica DM IRE2, Wetzlar, Germany). Images were captured at 20 magnification using a Leica DFC340 digital camera.

2.3 Flow Cytometry Analysis

Fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibodies were used for intracellular staining of specific antigens associated with polarization. Before staining, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% saponin. Cells were stained with either Pacific Blue™ conjugated-Rat IgG1, (1:500, clone RTK2071), and APC conjugated-Rat IgG2a, (1:200, clone RTK2758)(BioLegend, Canada) or stained with BV421-conjugated anti-iNOS (1:200, clone CXNFT) and APC-conjugated anti-Arg1 (1:500, clone A1exF5) antibodies (Invitrogen, Burlington, Canada). Following incubation with the antibodies at 4 °C, cells were washed and acquired using a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Ontario, Canada). Data was analyzed with FlowJo software (BD). To assess M viability following stimulation, cells were stained with Propidium Iodide solution (1:500, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) following the respective polarization timepoints.

2.4 Arginase Assay

The arginase enzyme activity in M was assessed by measuring urea production, as previously published [15, 16, 20, 21]. Briefly, using M lysate supernatants, the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford Reagent (BRA222.500, BioShop, Ontario, Canada) and standardized to 100 µg/mL. Using a Varioskan microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ontario, Canada) to read samples at 550 nm, concentrations of the samples were determined using a urea standard curve (0–25 nM).

2.5 Nitric Oxide Assay

Nitric oxide (NO) production was quantified as nitrite from cell supernatants using the Griess reaction as previously described [22, 23]. A sulfanilamide solution (1% w/v sulfanilamide in 5% w/v phosphoric acid; Sigma Aldrich, Ontario, Canada) was added to each sample for 10 minutes, followed by the addition of NED solution (0.1% w/v N-1-napthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride in water, Sigma Aldrich, Ontario, Canada) for another 10 minutes. Absorbance at 540 nm was measured using a Varioskan microplate reader, and nitrite concentrations were determined by comparison with a sodium nitrite standard curve (0–100 µM; Fisher Scientific, Ontario, Canada).

2.6 Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Bone marrow and spleen cells were seeded at a concentration of 2–4 106/well and stimulated as described above. Following supernatant collection, cytokine secretion was quantified according to manufacturer’s instructions: IL-10 (eBioscience, Ontario, Canada). Using the BioTek ELx800 microplate reader (Winooski, VT, USA), absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

2.7 Gene Transcription Analyses with Quantiative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Using the PuroSPIN™ Total RNA Purification Kit (NK-051-250, Luna Nanotech, Ontario, Canada), total RNA was extracted from cells (1 106). Following reverse transcription, cDNA was mixed with AzuraView GreenFast qPCR Blue Mix LR (Froggabio, Canada) and the following primers obtained from (IDT, Canada): Arginase 1: Forward: 5′-GGAATCTGCATGGGCAACCTGTGT-3′, Reverse: 5′-AGGGTCTACGTCTCGCAAGCCA-3′, Found in inflammatory zone (FIZZ1): Forward: 5′-TGCTGGGATGACTGCTACTG-3′, Reverse: 5′-CTGGGTTCTCCACCTCTTCA-3′, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF): Forward: 5′-GCACTGGACCCTGGCTTTAC-3′, Reverse: 5′-ACCAGGGTCTCAATCGGACG-3′. Samples were run in the Bio-Rad Real-time thermal cycler CFX96 (Bio-Rad, Quebec, Canada) and Cq values were analyzed using the CFX Manager Software Bio-Rad. Using the Delta-Delta Ct method as previously published [24], values were normalized to GAPDH: Forward: 5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′, Reverse: 5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′.

2.8 Statistical Analysis

Prism GraphPad 6 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to analyze and graph all results. Data is expressed as mean SD and significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison’s test (* p 0.05, ** p 0.01, *** p 0.001, **** p 0.0001). All significance shown on bar graphs is compared to the unstimulated (UN) control.

3. Results

3.1 Morphological and Viability Analyses Following Long LPS and NECA Stimulation

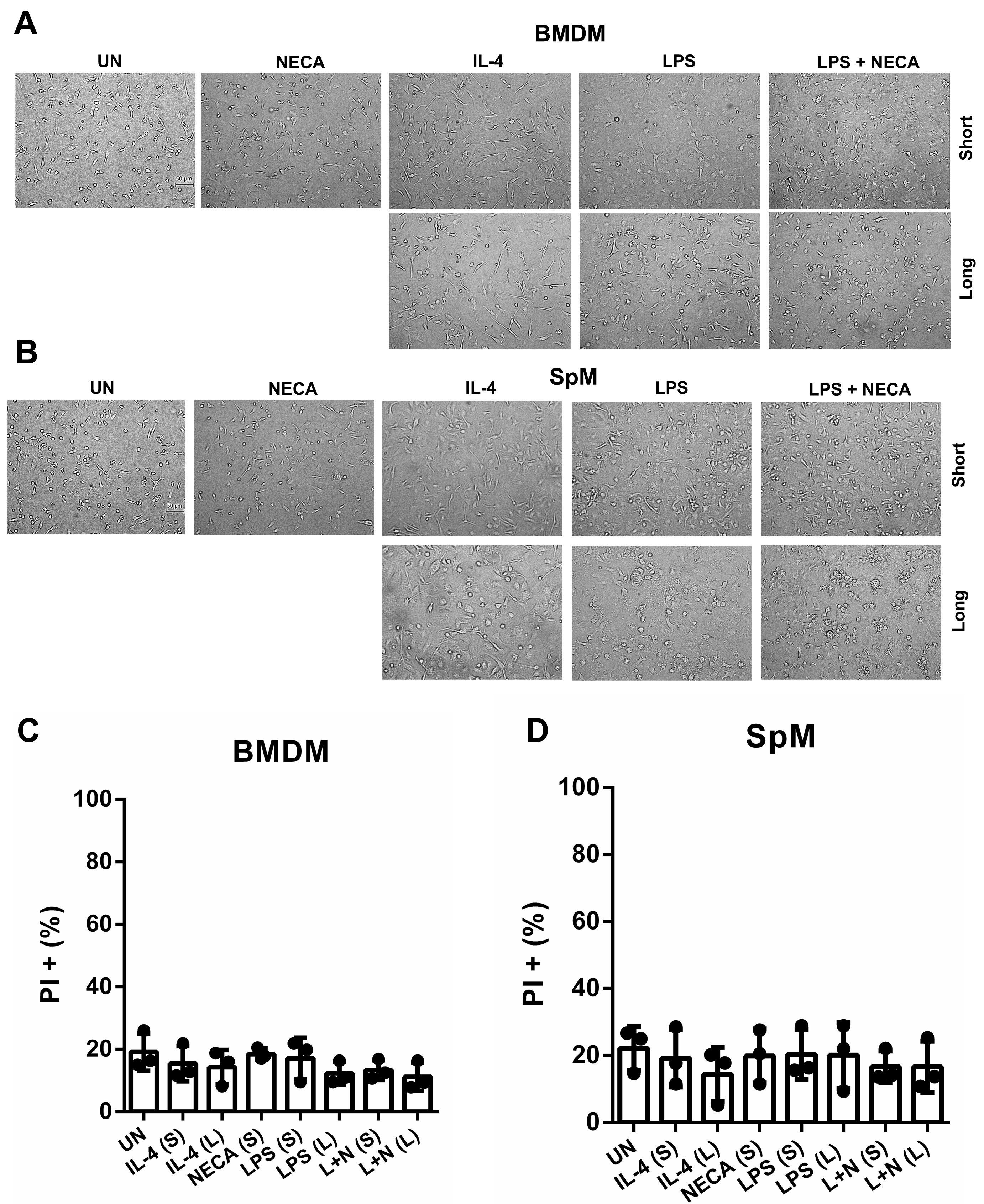

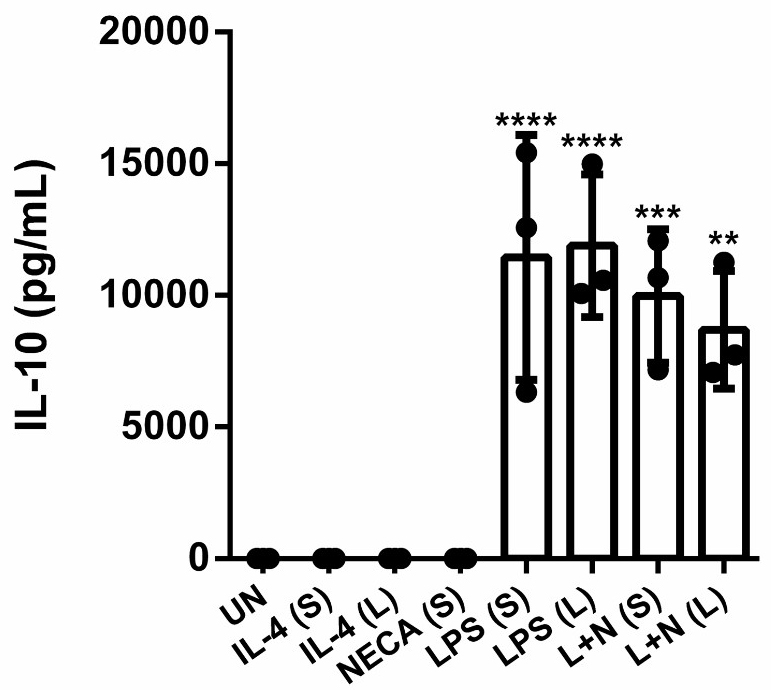

Since we are the first group to study both short and prolonged primary stimulated M2d M, we first wanted to evaluate if the longer polarization into distinct M phenotypes affected viability. As seen in Fig. 1 treatment with IL-4, LPS, and NECA did not reduce cell viability in bone marrow after short and long stimulation (Fig. 1C). Spleen cells were also not affected (Fig. 1D). However, NECA alone did significantly affect cell viability when stimulated for 48 h (data not shown), and therefore we did not utilize this condition in the subsequent experiments as this would affect the experimental read out.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Morphological analyses via microscopy reveal distinct features of M2d and M2a M. Brightfield images taken at 20 of BMDM at (A) and SpM (B) were taken following 24 h and 48 h stimulation. The scale bar = 50 μm, same scale for all sub-graphs. Percentage of PI+ cells in BMDMs (C) and SpM (D) were evaluated using flow cytometry following polarization. Bar graphs show data from 3 independent experiments SD where no significant effect was observed on cell viability. Abbreviations: UN, unstimulated; IL-4, interleukin-4; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NECA, N-ethylcarboxamido adenosine; L, long; S, short; L + N, LPS + NECA; BMDM, bone marrow derived macrophages; SpM, spleen derived macrophages; M, Macrophages.

We also observed the morphology of the cells following stimulation (Fig. 1A,B). NECA did not appear to induce any alterations in cell morphology compared to unstimulated cells in both M subtypes. Stimulation with IL-4 promoted an elongated cellular phenotype, whereas LPS resulted in a more rounded phenotype in both BMDMs and SpM. Co-stimulation with LPS and NECA produced a morphological phenotype closely resembling that induced by LPS alone in both BMDMs and SpMs. These findings provide insights into the distinct morphological characteristics when culturing different subtypes of M2 M in vitro.

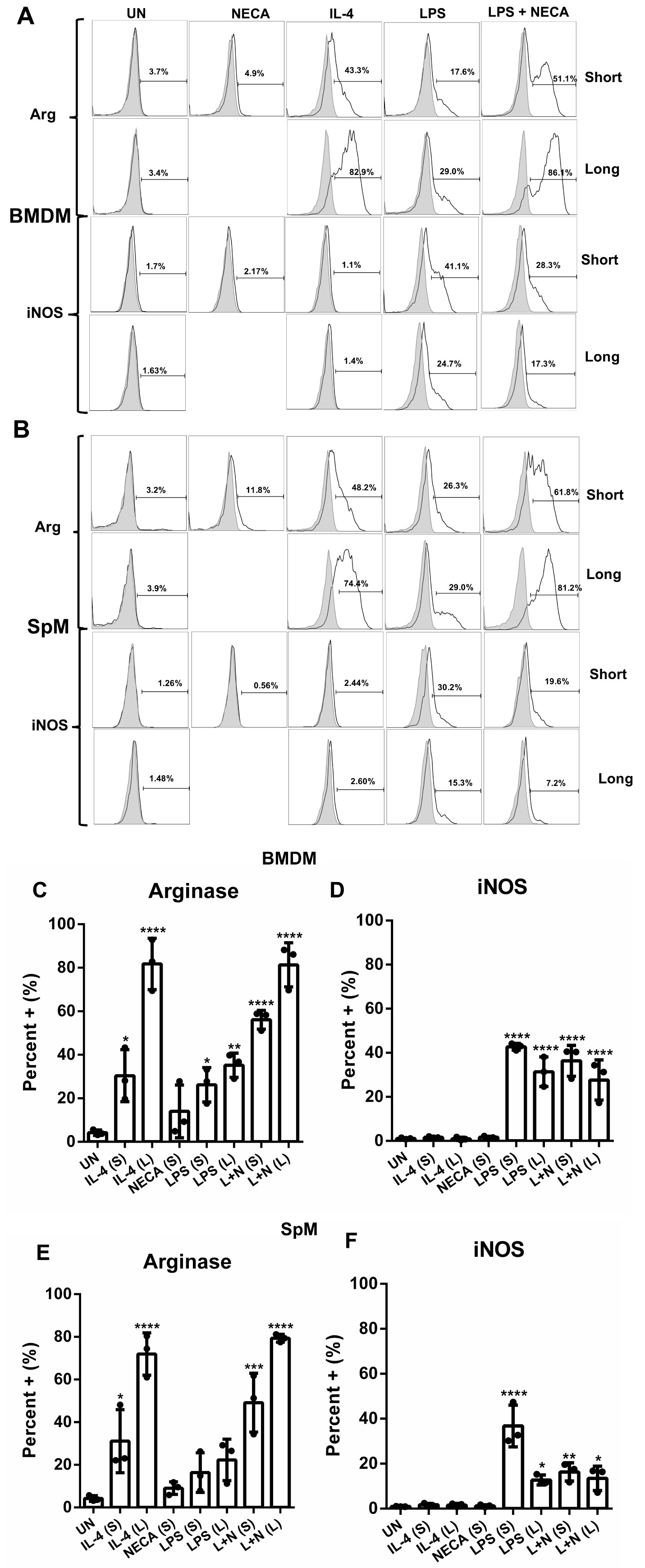

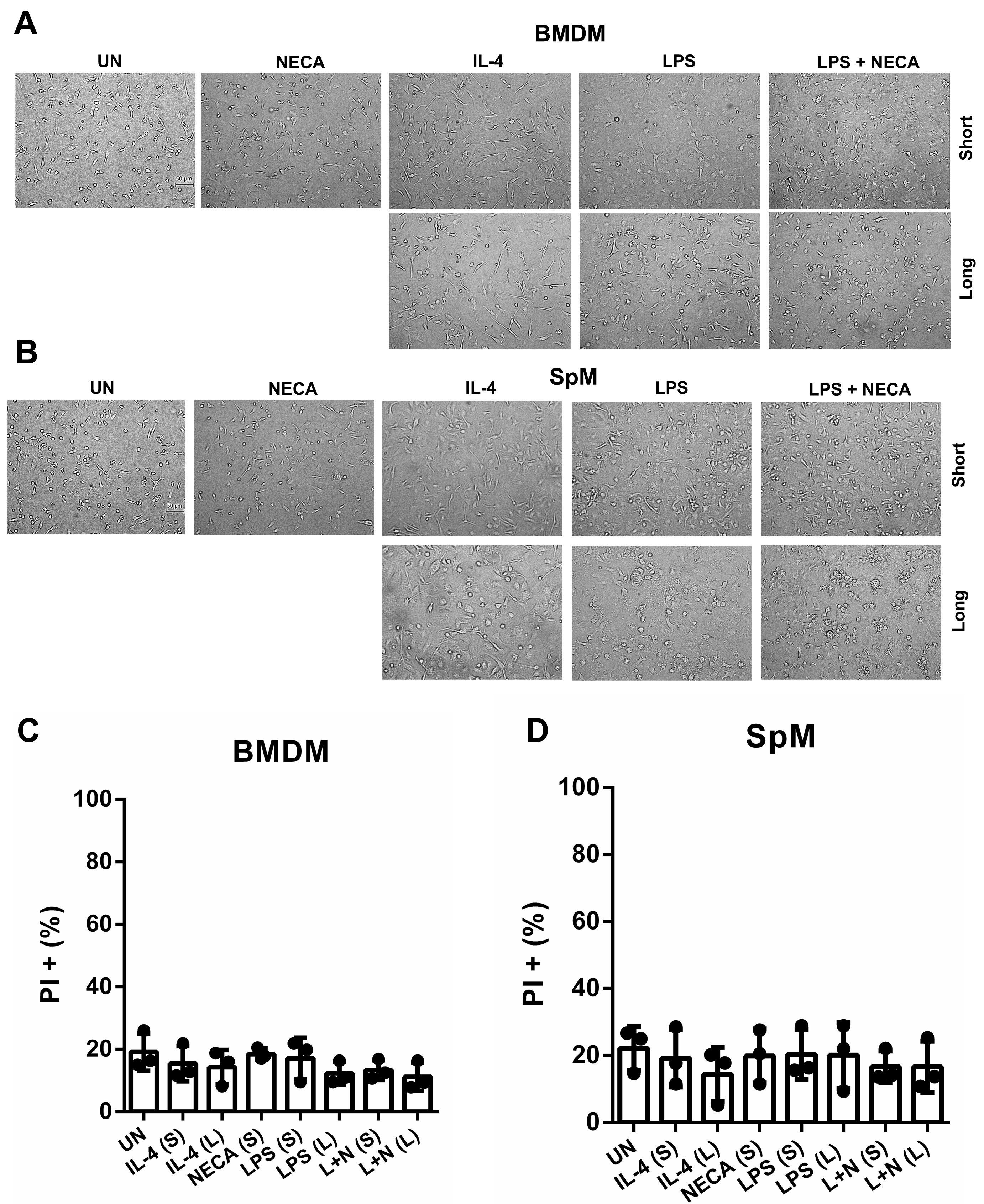

3.2 Prolonged LPS and NECA Stimulation Upregulates Arginase

Next, investigated the intracellular enzyme expression of two distinctive markers of M polarization, Arginase and iNOS. We show one representative experiment using histograms (Fig. 2A,B) and have plotted all of the repeats into bar graphs (Fig. 2C–F). Our data acquired via flow cytometry, revealed a significant upregulation of Arginase in both the short and prolonged M2a and M2d, conditions with notably higher expression in the prolonged phenotype of both M2 subtypes in both BMDMs (Fig. 2A,C) and SpMs (Fig. 2B,E). Short and long stimulation also induced iNOS expression in M2d cells, which was comparable to iNOS expression induced by LPS alone in BMDMs (Fig. 2D), but short stimulation remained lower compared to LPS stimulation alone in SpMs (Fig. 2F). M2a M on the other hand were not able to induce iNOS expression in both BMDMs and SpMs highlighting yet another distinct characteristic between the different M2 subtypes.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Arginase and iNOS enzyme expression in M2d M is upregulated following short and prolonged stimulations. Intracellular staining for Arg and iNOS was performed using flow cytometry. A representative histogram from one experiment is shown from BMDMs (A) and SpMs (B). Bar graphs show the percentage of Arg and iNOS positive cells from three independent experiments in BMDMs (C,D) and SpM (E,F) respectively SD. Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison’s test (* p 0.05, ** p 0.01, *** p 0.001, **** p 0.0001). Abbreviations: UN, unstimulated; IL-4, interleukin-4; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NECA, N-ethylcarboxamido adenosine; L, long; S, short; L + N, LPS + NECA; BMDM, bone marrow derived macrophages; SpM, spleen derived macrophages; Arg, arginase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase.

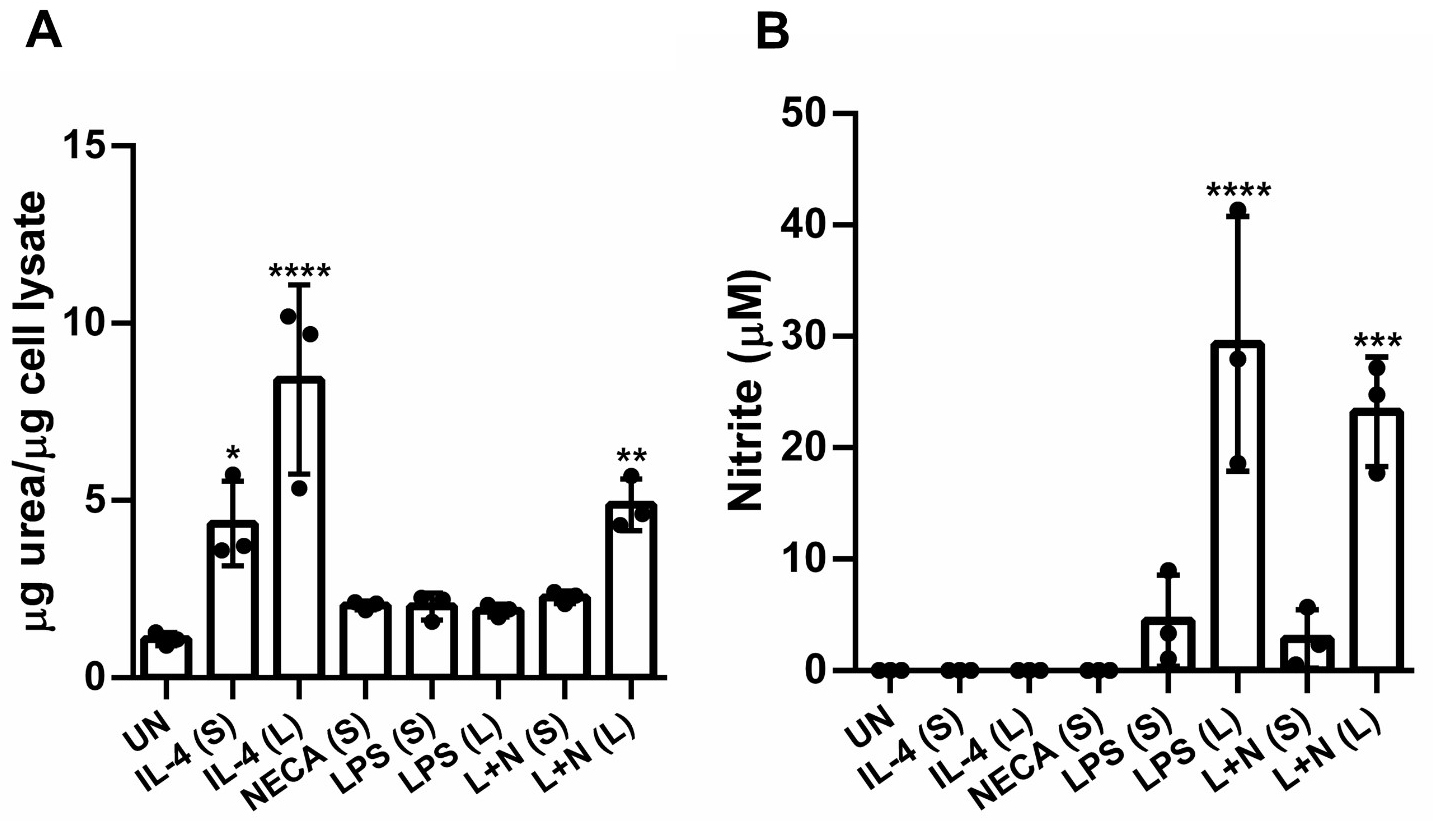

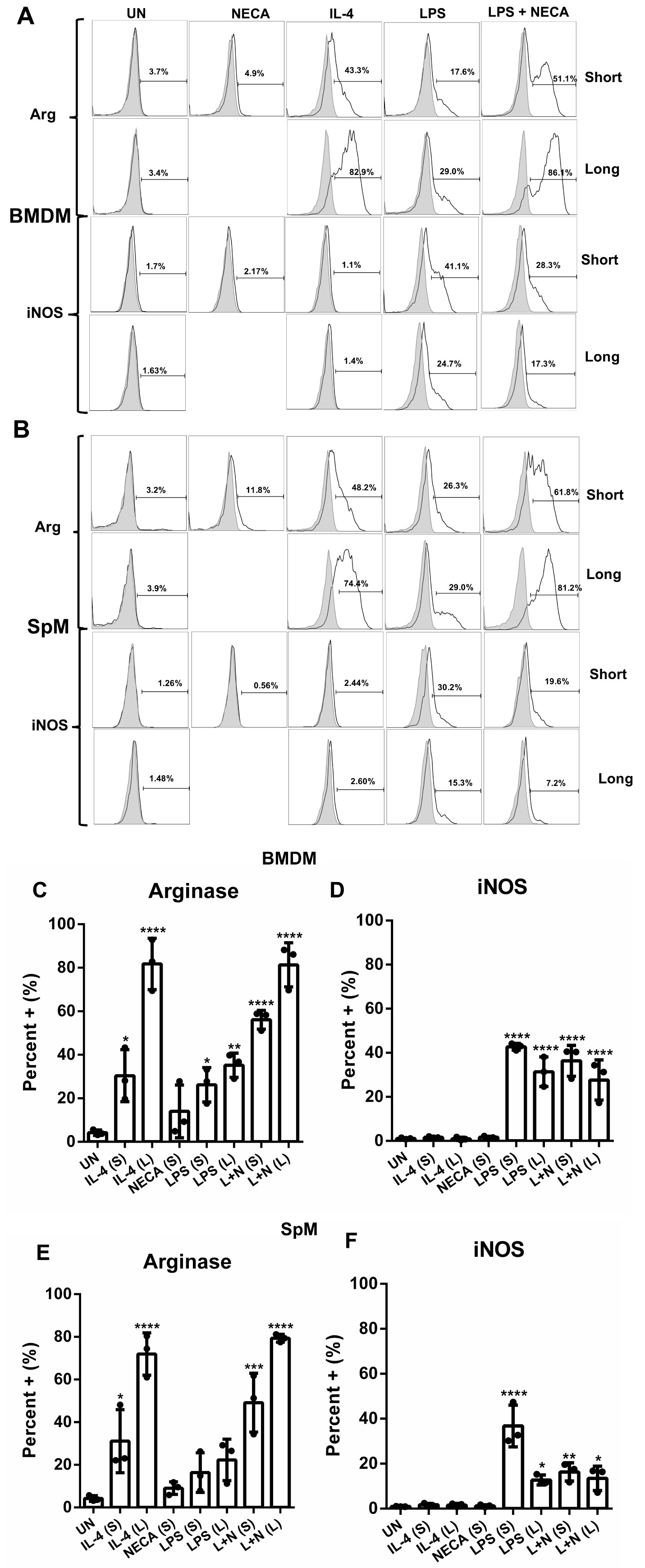

3.3 M2d Cells are Distinct from M2a Cells in Their Urea and Nitrite Production

To further investigate the enzymatic activity of Arginase and iNOS on a functional level, we performed functional protein assays to detect urea and nitrite production respectively in SpM. Our results align with previously published data from our group showing that M2a M induce urea production with prolonged treatment resulting in higher levels (Fig. 3A) [20, 25]. In contrast, short-term M2d stimulation did not significantly induce urea production whereas prolonged stimulation did, although the levels were lower compared to M2a M, further distinguishing the M2 subtypes regarding their urea production.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Prolonged M2d stimulation induces both urea and nitrite production in SpMs. (A) Arginase assay to detect for urea production in stimulated cells. (B) NO assay to detect for nitrite production in the supernatant of stimulated cells. Bar graphs show data from three independent experiments SD. Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison’s test (*p 0.05, ** p 0.01, *** p 0.001, **** p 0.0001). Abbreviations: UN, unstimulated; IL-4, interleukin-4; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NECA, N-ethylcarboxamido adenosine; L, long; S, short; L + N, LPS + NECA.

Regarding nitrite production, prolonged M2d stimulation led to a significant increase in nitrite, but not to the extent observed with prolonged LPS treatment (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, these results did not fully parallel the flow cytometry data obtained when iNOS expression was analyzed using intracellular staining. In the functional assay, nitrite levels increased in the prolonged group despite a lower percentage of iNOS positive cells observed through flow cytometry when compared to the short stimulation. This highlights the importance of employing multiple complementary tests, such as enzymatic assays coupled with functional protein assays, when characterizing M phenotypes. Ultimately, we demonstrate that M2a and M2d M exhibit distinct functional profiles regarding urea and nitrite production with long M2d stimulation capable of significantly upregulating both urea and nitrite production.

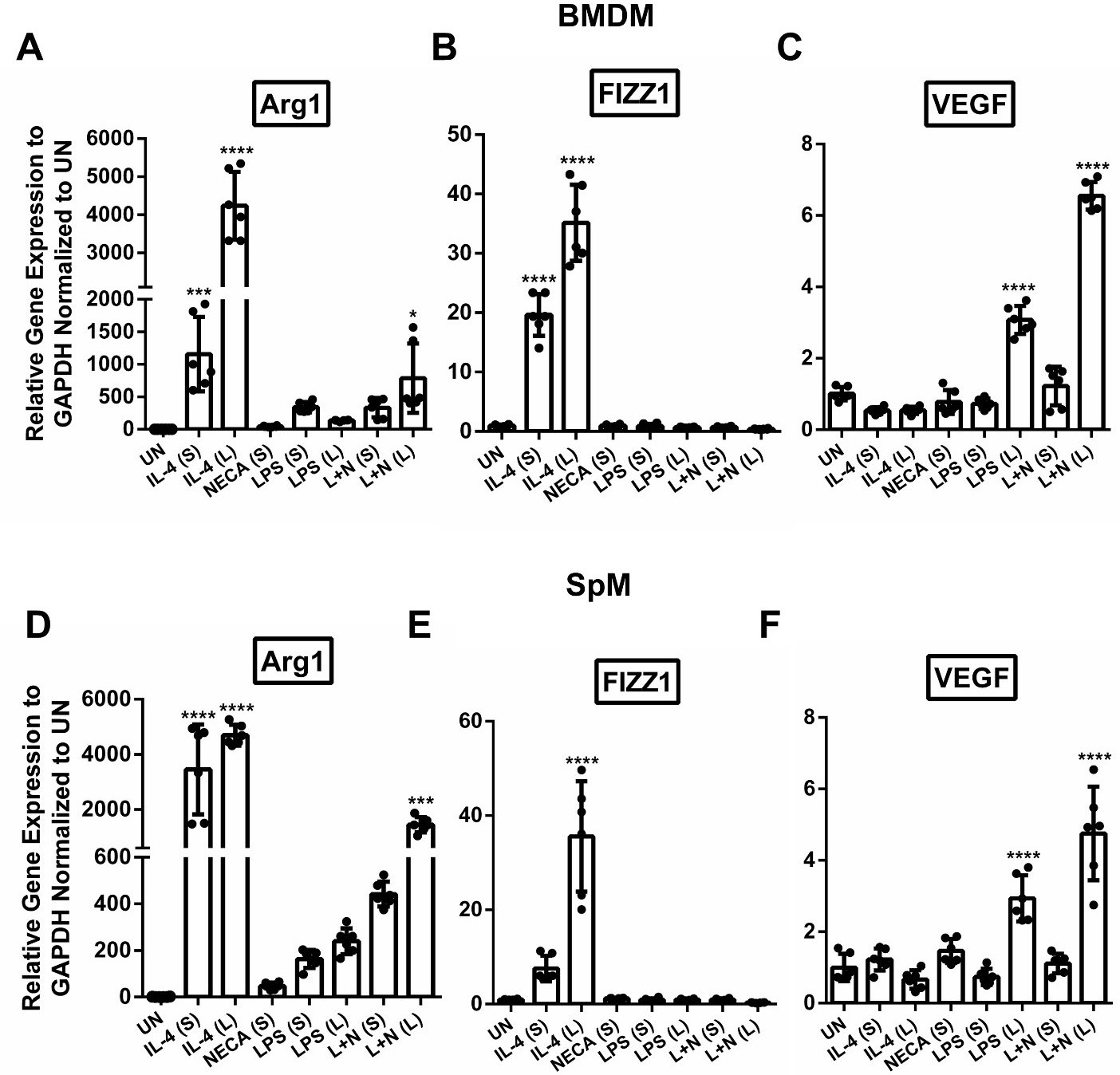

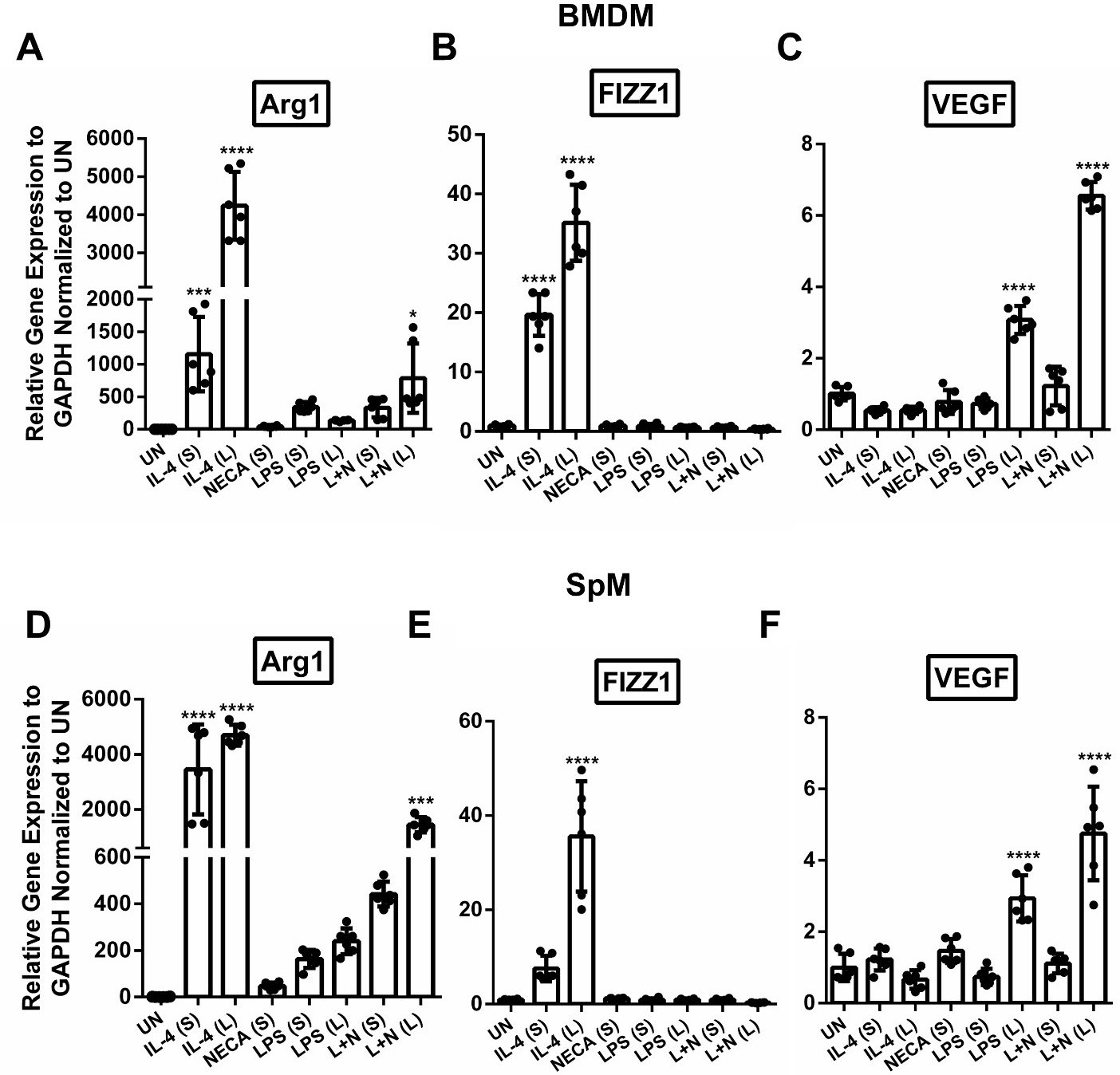

3.4 Prolonged M2d Stimulation Induces both Common and Unique Markers Compared to M2a M

We next wanted to examine gene expression following prolonged LPS and NECA stimulation. We chose to compare genes that are known to be upregulated in M2a M (Arg1 and FIZZ1) to establish how they would compare to M2d M. We also tested for a gene that is known to be upregulated in M2d M (VEGF), to confirm its expression in primary cells and at the same time compare its expression between short and long M2d stimulation. Our results indicate that both M2a and M2d M induce Arg1 expression (paralleling our flow cytometry and functional assay data), but the levels induced by M2d M are much lower compared to M2a M in both BMDMs and SpMs (Fig. 4A,D). While M2a M were able to induce significant FIZZ1 expression, both the short and long M2d M failed to induce FIZZ1 gene expression (Fig. 4B,E). Additionally, the prolonged M2d stimulation significantly induced VEGF gene expression (Fig. 4C,F) compared to short stimulation highlighting a unique characteristic of prolonged stimulation with LPS and NECA that is not observable with short stimulation.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. M2a and M2d M differ in their gene expression profiles. Arg1 gene expression in stimulated BMDMs (A) and SpMs (D). FIZZ1 gene expression in stimulated BMDMs (B) and SpMs (E). VEGF gene expression in stimulated BMDMs (C) and SpMs (F). Bar graphs show one representative experiment from three independent experiments SD showing similar profiles. Six points are plotted which represent three biological repeats each with two technical repeats from one experiment. Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison’s test (*p 0.05, *** p 0.001, **** p 0.0001). Abbreviations: UN, unstimulated; IL-4, interleukin-4; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NECA, N-ethylcarboxamido adenosine; L, long; S, L + N, LPS + NECA short; BMDM, bone marrow derived macrophages; SpM, spleen derived macrophages, Arg1, arginase 1; FIZZ1, found in inflammatory zone 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; GAPDH, Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

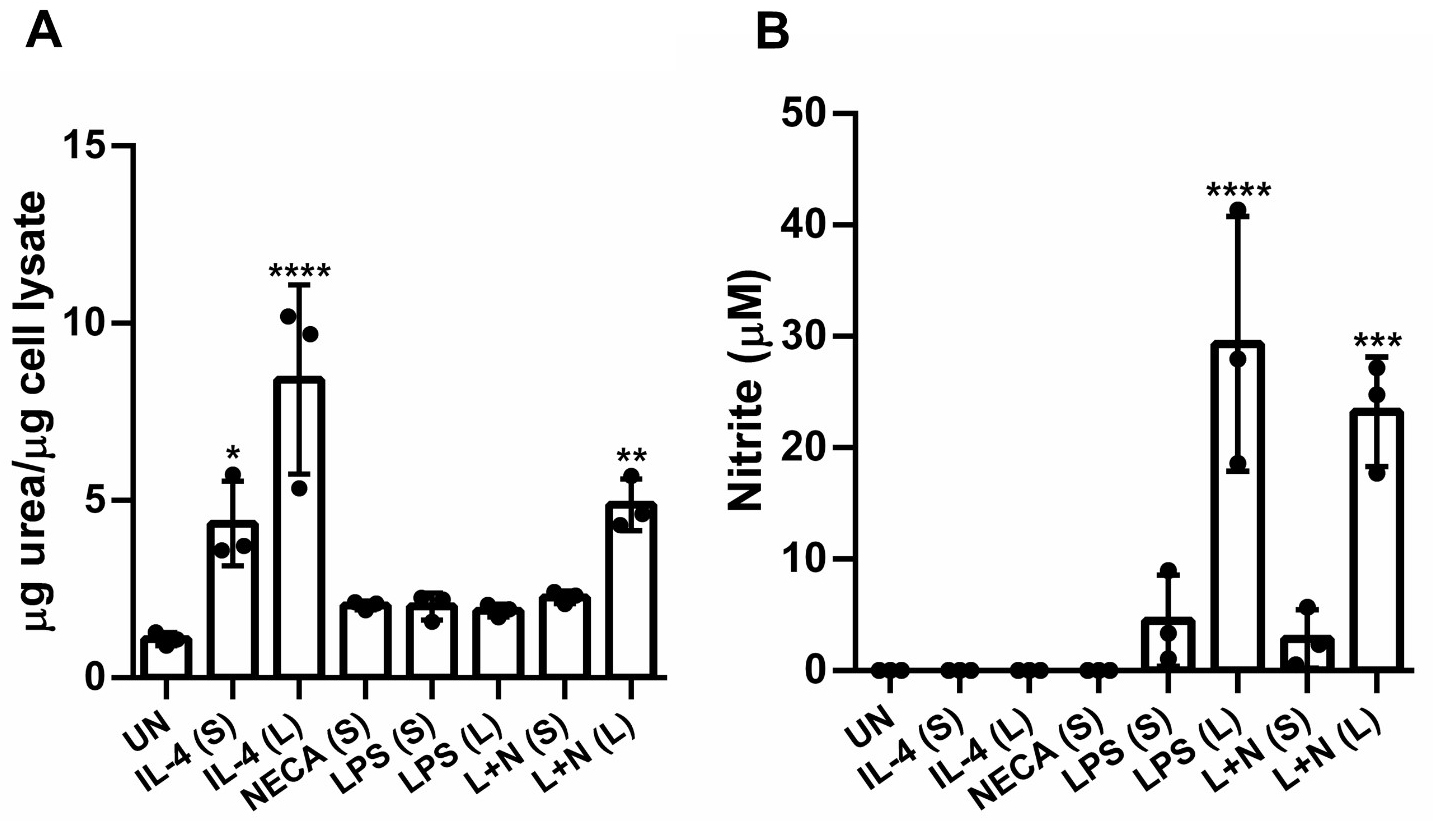

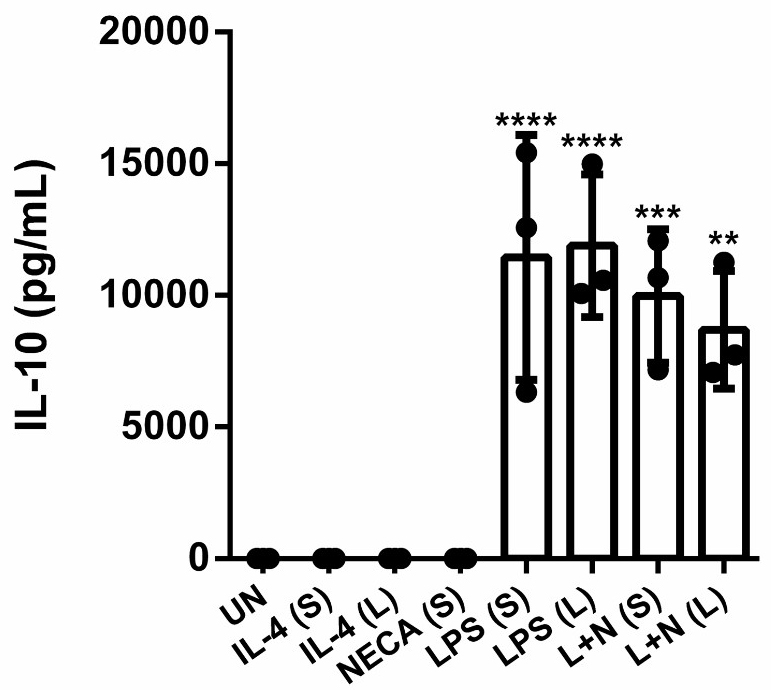

3.5 Prolonged M2d Stimulation Induces IL-10 Production

Finally, we wanted to detect cytokine secretion in BMDMs following LPS and NECA stimulation. We examined the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 as it has been reported before that M2d M secrete IL-10 efficiently [12, 26]. Fig. 5 demonstrates that that both short and prolonged LPS and NECA stimulation can induce IL-10 secretion and that the levels of IL-10 are comparable to cells stimulated with LPS alone for both time points. Stimulation with NECA alone was not sufficient to induce any IL-10 secretion. Furthermore, M2a M failed to induce any IL-10 production, once again highlighting clear differences between the two M2 subtypes that were investigated in our study.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. M2d production of IL-10 is comparable following short and prolonged stimulation with LPS and NECA in BMDMs. ELISA was used to quantify IL-10 production from stimulated BMDMs. Bar graph shows data from three independent experiments SD. Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison’s test (** p 0.01, *** p 0.001, **** p 0.0001). Abbreviations: UN, unstimulated; IL-4, interleukin-4; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NECA, N-ethylcarboxamido adenosine; L, long; S, short; L + N, LPS + NECA; IL-10, interleukin 10; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

4. Discussion

The characteristics of M2d M cultured in vitro remain poorly defined, particularly concerning their functional properties following stimulation with LPS and NECA. Our study aimed to expand the understanding of M2d M providing novel insights into their phenotypic profiles under prolonged stimulated conditions. We present for the first time, distinct phenotypic profiles of primary M2d M derived from different ex vivo isolated tissues following both short- and long-term stimulation with LPS and NECA.

Our data suggests that stimulation with LPS and NECA induces a M phenotype with more pronounced pro-inflammatory characteristics following short stimulation. However, after an additional 24 h of culture, this phenotype shifts, with cells adopting a more anti-inflammatory phenotype aligning with the classical classification of M2d M, which are traditionally characterized as “anti-inflammatory” to distinguish them from other types of pro-inflammatory M1 M [27, 28, 29, 30, 31]. This observation is significant as most studies to date [11, 12, 13, 26] have focused on a single time point (short stimulation), potentially missing the dynamic nature and true characteristics of M2d M when cultured in vitro. Given that adenosine receptor activation suppresses inflammatory responses it stands to reason that an anti-inflammatory response is initiated post LPS stimulation. LPS stimulation is known to induce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and molecules, including ATP [32, 33]. Extracellular ATP, released as a danger signal, is converted by enzymes into adenosine [33, 34, 35]. The adenosine produced can then bind to adenosine receptors (A1, A2A, A2A, A3) on the same cell [35]. Activation of A2A and A2B receptors generally triggers anti-inflammatory responses, effectively acting as a feedback mechanism to limit excessive inflammation [35]. This natural process helps to regulate the immune response by balancing the initial pro-inflammatory effects of LPS with subsequent anti-inflammatory signals mediated by adenosine. Moreover, A2A receptor signaling suppresses the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-, IL-6, and IL-12 that is induced by TLR signaling [11]. Although the adenosine A2B receptor was also found to suppress TNF-, the A2A receptor was found to be the primary receptor that mediates this mechanism in M [36]. Additionally, A2A receptor signalling upregulates the production of IL-10, further promoting an anti-inflammatory phenotype in M [11]. A2A activation also leads to the upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 which activates the VEGF promoter, leading to increased production of VEGF [37, 38]. Therefore, adding NECA into this culture system, is thus responsible for the anti-inflammatory signaling and can be a very useful tool to study the functions of M2d M in vitro and their interactions with other immune cells.

Our current findings help showcase this phenotypic switch from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory. Firstly, the morphology of the cells following short and long LPS and NECA stimulation induced a more rounded shape, similarly to how cells appeared following LPS stimulation alone. LPS treatment, which is associated with a pro-inflammatory phenotype in M, is known to promote a morphology associated with a spindle-like shape and pronounced granularity, while M2a M which are stimulated by IL-4, take on a more elongated shape as previously reported [6, 39, 40, 41]. Further analyses using various quantitative assays to be further discussed revealed that prolonged stimulation actually promotes a more anti-inflammatory M2d phenotype in spite of LPS being present for 48 h along with NECA. These assays provided more definitive insights into the phenotypic profiles of M, highlighting the distinct responses of different subsets of M2 M cultured in vitro.

One of the most well-established methods for distinguishing between M1 versus M2 M involves assessing their metabolic status by detecting and quantifying iNOS and arginase expression and function [42]. Our previous research has demonstrated that M2a M significantly upregulate arginase expression and exhibit increased urea production, a key byproduct of the arginine metabolic pathway following IL-4 stimulation [15, 16, 41]. Notably, this effect is amplified following prolonged IL-4 exposure reflecting a more pronounced M2a phenotype [20, 25]. Given these findings, we sought to determine whether M2d M exhibit a similar or distinct metabolic profile to M2a M by investigating the upregulation of arginase and urea production particularly in response to prolonged treatment. Additionally, we examined the expression of iNOS and nitrite production which are typically induced by LPS stimulation.

Our data revealed that LPS alone can induce both expression of iNOS and arginase enzymes as observed by flow cytometry. Arginase levels continued to rise in the prolonged treated group while iNOS levels decreased over time. This observation is consistent with previous reports indicating that LPS can induce arginase, specifically the arginase I enzyme, which has been shown to have a role in down downregulating nitric oxide production in murine M by decreasing the availability of intracellular arginine for iNOS [43, 44]. When we compared arginase expression in LPS-treated cells to M2d-treated cells, we observed a similar pattern in arginase induction. Within the first 24 h, M2d cells exhibited high detection levels of both arginase and iNOS being detected. However, with prolonged treatment, arginase levels increased further while iNOS levels decreased. Notably the arginase levels in the M2d cells were significantly higher than in cells treated with LPS alone at both time points, suggesting that NECA exerts an additional antagonizing effect to LPS, particularly with extended stimulation.

The functional assays demonstrated that prolonged treatment was capable of inducing urea and nitrite. While urea induction paralleled the increase in arginase enzyme observed through flow cytometry, the nitrite production did not correlate with iNOS expression. Specifically, iNOS levels were reduced in the prolonged treated group compared to short stimulation, however, functional data revealed significantly higher nitrite levels under prolonged treated conditions. This finding contrasts with a previous report using RAW 264.7 cells, where LPS + NECA treatment (48 h) led to lower levels of nitrite compared to short treatment (24 h) [45]. However, it must be considered that, in general, nitrite levels were barely detectable in both cases possibly due the use of a cell line, in contrast to primary cells as we employed within our study. By utilizing primary cells, our data provides a more robust analysis, obtaining higher nitrite production with a much lower concentration of LPS (100 ng/mL) compared to the study which employed a higher concentration of LPS (1 µg/mL) to stimulate the RAW 264.7 cell line. It is also important to point out that the original paper testing LPS with NECA for 24 h only used 100 ng/mL of LPS, a concentration comparable to that utilized in our study [12].

The Greiss assay involves collecting supernatant from cells following stimulation for indicated time points to quantify nitrite. The observed discrepancy between the nitrite concentrations and iNOS expression levels as measured by flow cytometry might be attributed to the distinct characteristics of the two methodologies and their kinetics. Flow cytometry captures a snapshot of iNOS expression at a particular time point, whereas the nitric oxide assay measures the cumulative accumulation of nitrite overtime. Following the peak of iNOS expression, the levels may gradually decline, however, the enzyme can maintain residual activity, thereby sustaining nitric oxide production and subsequent nitrite accumulation that can be sustained over days until the enzyme is degraded [46, 47]. Ultimately, these findings indicate that prolonged M2d stimulated cells can activate both arginase and iNOS, leading to the production of their respective by-products, urea and nitrite. More specifically, a continual increase in arginase, alongside a decrease in iNOS expression, suggests a shift towards a more anti-inflammatory phenotype. This shift reflects distinct functional roles in M subsets particularly between M2a and M2d M. M2a M, induced by IL-4, exhibit high arginase expression, which is critical for tissue repair and resolution of inflammation [48]. Arginase catalyzes the conversion of L-arginine to ornithine, a precursor for collagen synthesis and tissue remodelling, promoting healing and tissue repair [48]. Coupled with low iNOS expression and NO production, this phenotype supports a pro-repair and anti-inflammatory environment. This balance is consistent with the role of M2a M in tissue regeneration and immunoregulation [48]. In M2d M, the upregulation of arginase is similarly prominent but occurs in the context of prolonged LPS and NECA stimulation, concurrent with a temporal decrease of iNOS expression. While arginase activity in M2d M also contributes to L-arginine depletion and immune suppression, its effects are accompanied by the secretion of IL-10 and expression of VEGF (as we report below). This functional shift distinguishes M2d M from M2a M and highlights their role in pathological settings such as chronic inflammation and tumour progression, where immunosuppression and enhanced vascularization are advantageous to the tumour microenvironment [49].

We also investigated known M2a- and M2d-associated genes and proteins using qPCR and ELISA to investigate the differences in expression profiles between M2a and M2d M, as well as compare the effects of short versus prolonged M2d stimulation. A previous study has reported that short M2d stimulation induces Arg1 but not FIZZ1 expression, while IL-4 stimulation can induce both within mouse peritoneal M [12]. Consistent with these findings, our data demonstrated similar expression patterns in other primary M, such as BMDMs and SpMs, where short M2d stimulation induced Arg1 but not FIZZ1 expression. Additionally, we provide novel data that under prolonged M2d stimulation, Arg1, expression persisted whereas FIZZ1 expression remained absent. This supports the notion that FIZZ1 expression is specific to M2a M following IL-4/IL-13 stimulation [50, 51] and that even prolonged LPS and NECA stimulation, which shifts the cells to a more anti-inflammatory phenotype, is insufficient to induce FIZZ1 expression. Short stimulation with LPS and NECA (18 h) has been shown previously to induce VEGF and IL-10 secretion in mouse peritoneal M and RAW264.7 cells [12, 26]. Our findings extend on this by demonstrating that only prolonged stimulation effectively induces VEGF gene expression in both BMDMs and SpMs. This suggests a delayed induction in VEGF gene expression in these primary M becoming apparent only with prolonged treatment as the cells transition to an anti-inflammatory phenotype. The distinct gene expression profiles observed in M2d M including the upregulation of VEGF and lack of FIZZ1, likely reflects the activation of specific signalling pathways in response to LPS and NECA co-stimulation. Specifically, the activation of adenosine receptors (A2A and A2B) by NECA is known to trigger cyclic adenosine 3,5-monophosphate (cAMP)/p-21 activated kinases (PKA) signalling, which can lead to the activation of transcription factors such as cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB). CREB activation has been implicated in VEGF expression under hypoxic and inflammatory conditions which aligns with the upregulation of VEGF observed in our M2d macrophage model [52, 53, 54]. Similarly, prolonged TLR4 stimulation can activate nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-B) and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3, both of which are involved in modulating anti-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic responses [55]. The absence of FIZZ1 expression in M2d macrophages likely reflects the suppression of STAT6-dependent transcription, which is typically induced by IL-4 in M2a macrophages [56]. LPS and NECA co-stimulation likely favour alternative pathways, such as NF-B, and cAMP signalling, which do not promote STAT6 activation, leading to the selective upregulation of VEGF and the lack of FIZZ1 expression.

Regarding IL-10 secretion, our data revealed no significant differences between short and prolonged M2d stimulation in BMDMs, with IL-10 levels being comparable to those observed with LPS stimulation alone. This suggests that addition of NECA does not exert any additional effect on IL-10 secretion in this model but still aligns with previous studies demonstrating that co-stimulation of LPS and NECA induces IL-10 secretion in M [26, 52]. IL-10 is one of the hallmarks of alternatively activated M, yet its regulation differs significantly between M2a and M2d M. In M2a M, the production and secretion of IL-10 appears to be tightly controlled and context-dependent. In our model, polarization with IL-4 was not sufficient enough to induce IL-10 secretion. This suggests that co-stimulatory signals, such as interactions with specific cytokines or immune cells might be required to enhance IL-10 production. Moreover, our group has shown that IL-4 combined with TLR ligands, specifically the TLR 7/8 ligand R848 can synergistically induce IL-10 secretion in both short and prolonged IL-4 stimulated M [20]. This indicates that IL-4 primarily establishes an anti-inflammatory transcriptional landscape in M2a M but does not necessarily translate into active IL-10 production without additional stimuli. The lack of significant IL-10 secretion in M2a M reflects their primarily role in promoting tissue repair and extracellular matrix remodelling rather than immune suppression [57]. In contrast, M2d M, induced by prolonged LPS and NECA stimulation, produce IL-10 more robustly, aligning with their role in creating an immunosuppressive environment [57]. This distinction underscores, the functional specialization of M subsets and highlights how differences in IL-10 secretion contribute to their respective roles in immune regulation and tissue homeostasis.

In the context of the tumour microenvironment, different subtypes of M2 M secrete distinct soluble factors that can differentially influence tumour cell growth and progression. As mentioned above, M2a M are primarily associated with tissue repair and extracellular matrix remodelling through secretion of factors such as Tumour growth factor (TGF) - and chemokine ligand (CCL) 18 [58, 59]. These factors may indirectly facilitate tumour growth by promoting immune evasion and creating a pro-tumorigenic extracellular matrix. In contrast, M2d M produce VEGF, IL-10, and other angiogenic factors [58]. VEGF secretion, in particular, promotes tumour vascularization, which promotes tumour growth and metastasis [60]. Our study demonstrated that prolonged LPS and NECA stimulation significantly upregulated VEGF gene expression, highlighting a potential pro-angiogenic function in these cells that promote a favourable tumour microenvironment. Future investigations should focus on co-culture experiments with tumour cells to directly evaluate the functional effects of M2d-derived factors on tumour cell proliferation and survival.

Finally, it is important to note that in addition to this well-documented protocol using LPS and NECA for M2d M polarization, other methods such as IL-6 and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) stimulation have been reported to induce M2d-like M [61, 62]. These protocols highlight the diversity of M2d M induction strategies, each reflecting unique aspects of M plasticity in different physiological or pathological contexts. While our study employed the LPS + NECA combination due to its relevance in mimicking the adenosine-enriched tumour microenvironment, more importantly, this method offers an opportunity to address an important knowledge gap-that is, the characteristics of M polarized with LPS and NECA remain poorly understood, particularly under prolonged conditions. By utilizing this approach, we aimed to explore how LPS and NECA co-stimulation uniquely influences M phenotype over time. Future investigations comparing these methods could provide additional insights into how distinct stimuli influence M2d M phenotypes and functions.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.  Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.  Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.  Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.  Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.