1 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Medicine in Pilsen, Charles University, 23200 Pilsen, Czech Republic

2 Depratment of Chemistry, CY Cergy Paris Université, CNRS, BioCIS, 95000 Cergy Pontoise, France

3 Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine in Pilsen, Charles University, 23200 Pilsen, Czech Republic

4 Biomedical Center, Faculty of Medicine in Pilsen, Charles University, 23200 Pilsen, Czech Republic

Abstract

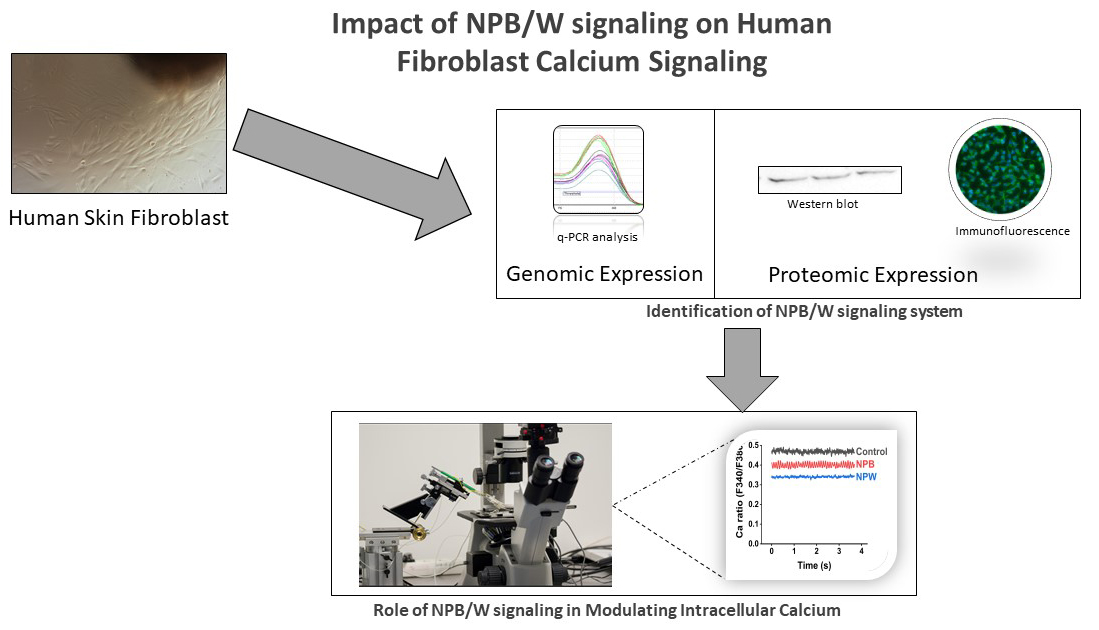

The neuropeptide B/W signalling system (NPB/W) has been identified in multiple body regions and is integral to several physiological processes, including the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis. Recently, it has also been detected in human skin; however, its specific functions in this context remain to be thoroughly investigated. This study aims to identify the expression of neuropeptides B/W receptor 1 (NPBWR1) and neuropeptides B/W receptor 2 (NPBWR2) in human dermal fibroblasts of mesenchymal origin using genomic and proteomic techniques. We will also investigate the role of these receptors in cell proliferation and calcium signalling.

The mRNAs for NPBWR1 and NPBWR2 were detected using quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis and further validated by western blot and immunofluorescence analyses. Additionally, we synthesised ligands for these receptors, specifically hNPB (25–53) and hNPW (33–62), to investigate their effects on cell proliferation and intracellular calcium levels in human fibroblasts.

Our results demonstrated that hNPW (33–62) has anti-proliferative effect on human dermal fibroblasts and concentration of 0.1-μmol/L can significantly decrease intracellular calcium levels (p < 0.05).

This finding suggests a potential role for the NPB/W signalling system in pathologies associated with impaired calcium handling, such as fibrosis. Furthermore, we observed that the proliferation of human fibroblasts was not affected by hNPB (25–53). Our findings could lead to the development of new therapeutic strategies for various skin conditions and improved wound healing.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- NPBWR1

- NPBWR2

- fibroblasts

- calcium signalling

- NPB

- NPW

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent a significant family of cell surface receptors and play a crucial role in detecting signals from the extracellular environment and regulating intercellular communication through various ligands. These receptors are integral to numerous physiological processes, such as inflammation and wound healing [1].

It is noteworthy that many GPCRs were characterised prior to the identification of their respective ligands. This holds true for the GPR7 and GPR8 receptors, which were initially described in the 1990s; their ligands were assigned a decade later [2]. The ligands associated with these receptors are two neuropeptides known as neuropeptide B (NPB) and neuropeptide W (NPW), which collectively form the NPB/W signalling system. In light of these ligands, the International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (IUPHAR) reclassified GPR7 and GPR8 as NPBWR1 and NPBWR2, respectively. It is also of interest to note that NPBWR2 is not expressed in rodent models [3].

The expression and function of the NPB/W signalling system have been investigated across various tissues and organs, including the central nervous system, endocrine glands, gastrointestinal tract, and adipocytes [2, 4, 5]. The findings from these studies indicate a range of functions associated with the NPB/W signalling system as a whole and its individual components.

At the organism level, the NPB/W signalling system is integral to the central regulation of food intake and the maintenance of energy homeostasis. At the cellular level, research has examined its effects on chondrocytes, smooth muscle cells, calvaria osteoblast-like cells, and preadipocytes, revealing diverse influences on cell proliferation and differentiation [4, 6, 7, 8].

Neuropeptides are important signalling molecules synthesised and released by nerve cells and, in certain instances, non-neuronal cells. They are integral to a range of cellular responses, including within the skin. Depending on the presence of receptors specific to the released neuropeptides, different cell types serve as target cells within the skin. In human skin, mRNA expression has been identified for all components of the NPB/W signalling system, including NPB, NPW, and their associated receptors [2]. However, determining the precise sources of NPB and NPW within the skin remains challenging when the analysis is conducted on a homogenised skin sample. Furthermore, identifying the target cells for these neuropeptides is complicated by the diverse array of cell types present in the skin: endothelial cells, keratinocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts.

Dermal fibroblasts are integral to the wound-healing process, facilitating both cell proliferation and the synthesis of extracellular matrix components [9]. As key cellular constituents of the skin, they play a significant role in maintaining homeostasis [10]. Research has identified several GPCRs on the fibroblast surface, enabling these cells to receive and respond to a variety of signals. The activation of GPCRs by specific stimuli can elicit a range of cellular responses, including alterations in gene expression, enhanced cell proliferation, and the secretion of extracellular matrix components. As a result, while fibroblast activation can promote effective wound healing and tissue repair, it may also lead to fibrosis due to excessive fibroblast production [10].

Furthermore, neuropeptide Y (NPY), a neuropeptide with functional similarities to NPB and NPW [2], has been shown to increase the proliferative capacity and migration of fibroblasts in both human and rat models. Additionally, NPY appears to delay the ageing of fibroblasts in these individuals [11, 12]. However, the extent to which the NPB/W signalling system influences the behaviour of human fibroblasts remains to be fully elucidated.

This study’s purpose was to investigate whether human skin fibroblasts express receptors associated with the NPB/W signalling system and examine the effects of NPB and NPW on these cells. The results may enhance our understanding of the potential role this signalling system plays in the physiological processes within the skin.

Fibroblast cells were cultivated from human skin following a 4-mm punch biopsy, using a procedure similar to that developed by Vangipuram et al. in 2013 [13]. A 6-well plate was coated with gelatin (0.1%, G1393, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature (RT) for 60 minutes. After this time, the gelatine solution was removed and replaced with 800 µL of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), which contained high glucose, stable glutamine, and sodium pyruvate (Biowest, Nuaille, France), supplemented with 20% foetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and 100 IU/mL of streptomycin/penicillin (A5955, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA).

The skin biopsy was then dissected into evenly sized small pieces using a scalpel. Three to five pieces of skin biopsy were placed in each well and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Daily monitoring of media evaporation was conducted, and 200 µL of DMEM was added every two days to compensate for evaporation during the first week. After one week, the volume of DMEM was increased to 2 mL. The medium was changed every 2–3 days until the fibroblasts reached confluence.

Once confluent, the plate was trypsinised, and the cells were transferred to two T75 flasks (passage 1). When the fibroblast cells became confluent in the T75 flasks, they were further transferred to three additional T75 flasks (passage 2). Finally, a 10% DMSO stock was prepared for the fibroblast cells at a concentration of 1

RNA was isolated from fibroblast cells utilising RNeasy Micro Kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. To eliminate any contaminating DNA, 1 unit of DNAse per microgram of total RNA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was incorporated into the procedure. The isolated RNA was reverse-transcribed using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 50 minutes at 42 °C. Two micrograms of total RNA were utilised to synthesise single-stranded cDNA. The qPCR analysis was conducted as previously outlined [15].

The primers were specifically designed to amplify target sequences corresponding to the following nucleotides: vimentin (forward: AAGACACTATTGGCCGCCTG (1507–1526), reverse: ATTCACGAAGGTGACGAGCC (1559–1578)), NPBWR1 (forward: TGACCTCGAGCCTTCTTGGA (3674–3693), reverse: CGTATGAAGGGCAACGACCT (3860–3879)), and NPBWR2 (forward: GCCAACGTCTCTCAGGACAA (360–379), reverse: TCACCGTCTTCATCTTGGGC (512–531)).

The qPCR was performed on an iCycler (Bio-Rad, Prague, Czech Republic). The final volume of each assay was 15 µL. Each reaction contained 3.5 µL of diluted cDNA, 7.5 µL of iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Prague, Czech Republic), 0.15 µL of each primer (at a concentration of 20 nmol/L), and 3.7 µL of ultrapure water. All qPCR analyses were executed in duplicate following a strict protocol: an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 10 minutes, succeeded by 45 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 20 seconds, 60 °C for 20 seconds, and 72 °C for 20 seconds). A melting curve was subsequently generated by heating the samples from 65 °C to 95 °C, during which fluorescence was continuously monitored to confirm the specificity of each amplicon. Each pair of primers yielded a single peak in the melting curve and exhibited a single band of the expected size upon agarose gel electrophoresis.

Data quantification was performed using Optical System Software (Bio-Rad, Prague, Czech Republic), and normalisation of NPBWR1 and NPBWR2 was achieved using vimentin.

Fibroblast cells were cultured in a T75 flask until they reached confluence. Upon achieving confluence, the cells were treated with trypsin, and the resulting suspension was centrifuged to separate the pellet. The pellet was then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and solubilised in lysis buffer prior to homogenisation. The lysate was centrifuged at 10,000

A total of 25 µg of protein was loaded onto a 10% SDS-PAGE gel under reducing conditions (2% v/v

After blocking, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with either anti-NPBWR1 (1:500; bs-8618R, Bioss Antibodies Inc, Woburn, MA, USA) or anti-NPBWR2 (1:100; BP2-86659, Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA). Alternatively, it was incubated with anti-

The membrane underwent three washes (10 minutes each) with PBS-Tween (0.1%). The blot was treated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-IgGs (1:4000, A16116, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Frederick, MD, USA) for 45 minutes at RT. The membrane was washed three additional times with PBS-Tween (0.1%). The resulting blots were developed using the Clarity™ Western ECL kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Imaging was conducted using the ChemiDoc MP system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and the data were analysed with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

A glass slide was placed inside a sterile petri dish and 50 µL of a 1

For permeabilisation, the cells were treated with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 minutes at RT. The cells were washed three times with PBS and blocked with 5% normal goat serum in PBS at RT for 1 hour. The cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-NPBWR1 (1:200; bs-8618R, Bioss Antibodies Inc., Woburn, MA, USA), anti-NPBWR2 (1:150; BP2-86659, Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA), or anti-vimentin (1:100; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA).

Afterwards, the samples were washed three times with PBS and incubated for 1 hour at RT with FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgGs (1:300; F9887, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Finally, the cells were submerged in DAPI mounting medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Images were captured at 10

All Fmoc-protected amino acids, Fmoc-Wang resins, N,N′-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC), Ethyl (hydroxyimino)cyanoacetate (Oxyma), and 2-(1H-Benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethylaminium tetrafluoroborate (TBTU) were purchased from Iris Biotech GmbH (Marktredwitz, Germany). Peptide-grade DMF was obtained from Biosolve (Dieuze, France). Triisopropylsilane (TIS), DIPEA, and diethyl ether (Et2O) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Milan, Italy).

Peptides hNPB (25–53) and hNPW (33–62) were synthesised in solid-phase using a microwave-assisted protocol (MW-SPPS) on a Liberty Blue™ automated peptide synthesiser (CEM Corporation, Matthews, NC, USA), following the Fmoc/tBu strategy. The syntheses were performed on preloaded Wang TG resins: Fmoc-Ala-WANG TG and Fmoc-Trp(Boc)-WANG TG (0.25 mmol/g).

Fmoc-deprotections were conducted using a solution of 20% (v/v) piperidine in DMF. Peptide assembly was carried out by repeating the standard MW-SPPS coupling cycle for each amino acid, utilising Fmoc-protected amino acids (5 equivalents, 0.2 M in DMF), OxymaPure® (5 equivalents, 1 M in DMF), and DIC (5 equivalents, 0.5 M in DMF).

Cleavage from the resin and side-chain deprotection was achieved by treatment with a TFA/TIS/water solution (95: 2.5: 2.5 v/v/v, 1 mL/100 mg of resin-bound peptide). The cleavage was carried out for approximately four hours with vigorous shaking at RT. Each resin was filtered off, and the solution was concentrated by flushing with N2. Each peptide was precipitated from cold Et2O, centrifuged, and lyophilized.

Lyophilized crude peptides were purified by a semi-preparative Waters reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) on a Phenomenex Jupiter C18 (10 µm, 250 mm

| Peptide | Sequence | Retention Time (min) | Mass Calculated [M+3H]3+ | Mass Found [M+3H]3+ | HPLC Purity |

| hNPB (25–53) | WYKPAAGHSSYSVGRAAGLLSGLRRSPYA | 1.58 | 1027.50 | 1027.47 | 98% |

| hNPW (33–62) | WYKHVASPRYHTVGRAAGLLMGLRRSPYLW | 1.69 | 1182.07 | 1182.42 | 98% |

Peptides were synthesized in solid-phase using a microwave-assisted protocol on a Liberty Blue™ automated peptide synthesizer following the Fmoc/tBu strategy. Synthetic peptides were purified by RP-HPLC and analyzed by LC-MS analysis. The peptides were obtained with more than 95% purity. The solvent systems used were 0.1% TFA in H2O (A) and 0.1% TFA in CH3CN (B), and the gradient was 10%–90% B in 3 min. hNPB, human neuropeptide B; hNPW, human neuropeptide W.

Characterisation of the peptides was performed using analytical reverse-phase ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry (RP-UPLC ESI-MS). The measurement was performed using a Waters Acquity UPLC connected to a Waters 3100 ESI-SQD mass spectrometer, utilising a Luna Omega PS C18 column (1.6 µm, 2.1

50 µL of 1

This resulted in a total volume of 100 µL per well, corresponding to final peptide concentrations of 0.001 µmol/L, 0.01 µmol/L, 0.1 µmol/L, and 1 µmol/L, respectively. The cells were then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 48 hours.

After 48 hours, 10 µL of the cell proliferation reagent WST-1 (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated again at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for four hours. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy H1, Agilent BioTek, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

A 12-well or 9-well plate was utilised for this experiment. 500 µL of a solution containing 1

Following incubation, the media were removed, and the cells were washed with Ca2⁺-free Tyrode solution. After washing, the cells were treated with 5 µmol/L Fura-2-AM for 30 minutes at 37 °C. The Fura-2-AM solution (F1221, Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Technology, Eugene, OR, USA) was then removed, and the cells were washed with 1 mL of Tyrode solution for 10 minutes at 37 °C. After the final wash, the cells were exposed to 1 mL of 0.1 µmol/L hNPW (33–62) or 0.1 µmol/L hNPB (25–53) in Ca2⁺-free Tyrode solution.

The intracellular calcium levels in the cells were measured using the IonOptix HyperSwitch Myocyte Calcium and Contractility System (IonOptix LLC, Westwood, CA, USA). The Tyrode solution had the following composition (in mmol/L): NaCl 137, KCl 4.5, MgCl₂ 1, CaCl₂ 2, Glucose 10, HEPES 5, with the pH adjusted to 7.4 using NaOH. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Offline analysis was conducted using IonWizard 6.5 software (IonOptix LLC, Westwood, CA, USA).

Data were presented using a box and whisker plot. Moreover, univariate analysis was done by the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U- test for 2 groups by Kruskal-Wallis test for more groups, while mutivariate analysis was done using three way ANOVA models where also an experiment number effect nested in cell line effect was included. Dunnett’s adjustment for a multiple comparison with one control group was used in the ANOVA models. Statistical analyses were conducted with GraphPad Prism 7.02 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA) or SAS 9.4M8 (TS1M8) (producer SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) Statistical significance was set as p

Skin fibroblasts were successfully developed from dissected human skin biopsies. We observed that keratinocytes migrated out of the biopsy tissue within the first week. The outgrowth of keratinocytes was followed by the growth of fibroblast cells within 7 to 10 days. DMEM high-glucose media supplemented with 20% FBS promoted the growth of fibroblasts over keratinocytes. Consequently, the keratinocytes were depleted after two passages. Finally, the fibroblast cells were fully developed in 30 to 40 days, as confirmed by their morphology (shown in Fig. 1). A 10% DMSO stock was prepared, and we designated these stocks as PASSAGE-0 for use in our experiments. All experiments were conducted with cell lines that had not been passaged more than four times after PASSAGE-0 to avoid any mutations [16]. Similar cell lines were also used to prepare hiPSC and astrocytes [17].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Dermal fibroblasts from human skin. Cultivation of dermal fibroblasts was done from skin biopsies. The growth of keratinocytes was observed within 3 days and full confluency of fibroblast was achieved in 33 days (scale bar 50 µm).

10% DMSO stock were prepared. We considered these stocks as PASSAGE-0 and used them for our experiments. All the experiments were done with the cell lines which were not passaged more than 4 times after PASSAGE-0 to avoid any mutations.

RT-qPCR analysis was conducted across nine different cell lines. The presence of mRNA for vimentin was confirmed in all samples, validating the accuracy of all preceding steps. The Cq value of vimentin was used to compare the expression levels of NPBWR1 and NPBWR2 in each sample. mRNA for NPBWR2 was detected in all samples, whereas mRNA for NPBWR1 was present in only 6 out of the 9 samples. Notably, the relative expression of mRNA for NPBWR2 was approximately 32 times higher than that of mRNA for NPBWR1 (as shown in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Detection of mRNAs of neuropeptides B/W receptor (NPBWR1/NPBWR2) by RT-qPCR analysis. Different fibroblast cell lines were used for detection of mRNAs. We have observed the presence of NPBWR1 in 6 out of 9 samples and NPBWR2 in all the samples. (a) Data are presented as

These findings were further confirmed using proteomic approaches, including Western blotting (WB) and immunofluorescence analysis. Commercially available antibodies against vimentin, NPBWR1, and NPBWR2 were employed to detect both receptors in fibroblast cells. Our results indicated that all anti-vimentin-positive cells were also immunoreactive for both anti-NPBWR1 and anti-NPBWR2 antibodies, suggesting the presence of these receptors on the surface of all fibroblasts of mesenchymal origin.

Western blot analysis was performed on ten different cell lines. We observed a single immunogenic band for NPBWR1 at approximately 50 kDa in all ten samples (as shown in Fig. 3a). The expression level of NPBWR1 was about 0.3 times lower compared to

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Identification of NPBWR1/NPBWR2 by western blotting (WB) analysis. Different fibroblast cell lines were used to identify NPBWR1/NPBWR2. (a,c) We have observed the immunogenic band of NPBWR1 in 10 out of 10 samples (lane 1 to 10) at 50 kDa, but the expression of NPBWR1 was ~0.3 times lower than

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Identification of NPBWR1/NPBWR2 by immunofluorescence analysis. Different fibroblast cell lines were used for identification of NPBWR1 (n = 6) and NPBWR2 (n = 5). The cells were incubated with anti-NPBWR1, anti-NPBWR2, vimentin (positive control), and without primary antibodies (negative control). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgGs (green channel) were used to detect the primary antibodies along with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue channel) for nuclear staining (scale bar 50 µm). Images were taken using fluorescence microscope.

These results were further validated by proteomic approach through WB and immunofluorescence analysis.

We have synthesised the ligands of NPBWR1/NPBWR2, specifically hNPB (25–53) and hNPW (33–62), as detailed in Table 1. These synthetic peptides were utilised to investigate the influence of NPBWR1/2 signalling on cell proliferation and intracellular calcium levels. The viability of the treated cells was assessed using the WST-1 assay, and all experiments were conducted across 11 different experiments with 5 cell lines for NPB and 17 different experiments with 11 cell lines for NPW.

Cells were treated with four distinct concentrations of hNPB (25–53) and hNPW (33–62): 0.001 mol/L, 0.01 mol/L, 0.1 mol/L, and 1 mol/L. Overall, as illustrated in Fig. 5, we did not observe any statistically significant effects of hNPB (25–53) (p = 0.7338 Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.4180 ANOVA), while hNPW (33–62) shows a negative proliferative effect (p = 0.0464 Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0248 ANOVA) on cell viability as analyzed by multivariate in three-way ANOVA analysis (Fig. 5) and also by univariate Kruskal-Wallis test. Post hoc power analysis of hNPW (33–62) shows the power of testing as 50.8% with used sample size per groups (n = 17) to detect observed difference of 3.5 as statistically significant.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Impact of hNPB (25–53) and hNPW (33–62) on cell proliferation. The cells were treated with different concentrations of peptide solution 0.001-µmol/L, 0.01-µmol/L, 0.1-µmol/L, 1-µmol/L in DMEM media with 10% FBS and 0.1% streptomycin/penicillin. (a,c) For NPB and NPW respectively. Distribution of % inhibition was analyzed. (b,d) NPB and NPW respectively. We did not observe any statistically significant impact of hNPB (25–53), while hNPW (33–62) shows a negative proliferative effect on human dermal fibroblast (p = 0.0464 Kruskal-Wallis test, p = 0.0248 ANOVA). The data was analyzed by multivariate three-way ANOVA analysis and univariate Kruskal-Wallis test.

Additionally, we conducted an experiment to estimate the intracellular concentration of Ca2⁺ in fibroblasts after treating the cells with 0.1 µmol/L of either hNPB (25–53) or hNPW (33–62). This part of the study involved 7 different experiments with 5 different cell lines and we used a concentration of 0.1 µmol/L for the peptides. Our findings showed that hNPW (33–62) effectively interfered with intracellular calcium signalling, resulting in a decrease in the intracellular Ca2⁺ level in fibroblasts (p = 0.0248 Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.0109 ANOVA for hNPW (33–62) effect).

Conversely, we did not find any significant impact of hNPB (25–53) (p = 0.1517 Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.1618 ANOVA for hNPB (25–53) effect) on intracellular Ca2⁺ concentration, as depicted in Fig. 6. The results were analysed by measuring dual fluorescence intensity at excitation wave lengths of 340 nm and 380 nm.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Impact of hNPB (25–53) and hNPW (33–62) on intracellular Ca2+. The cells were treated with peptide solution consist of 0.1-µmol/L-hNPW (33–62) or 0.1-µmol/L-hNPB (25–53) in Ca2+ free Tyrode solution. We have observed that hNPW (33–62) was able to inhibit the intracellular Ca2+of the fibroblast. The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.0248 Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.0109 ANOVA for hNPW (33–62)) when compared to cells without peptide treatment. However, we did not observe any significant impact of hNPB (25–53) (p = 0.1517 Mann–Whitney U-test, p = 0.1618 ANOVA). (a) Distribution of F340/380 by experiment number. (b) NTy represents “Ca2+ free Tyrode solution without peptides”.

Fibroblasts are a diverse group of cells responsible for producing extracellular matrix. They exhibit transcriptional and functional differences depending on their tissue origin as well as variations within the same tissue [18]. Fibroblasts derived from mesenchymal tissues express the filamentous protein vimentin, while those of epithelial origin express fibroblast-specific protein and fibroblast activation protein [10]. Fibroblasts represent the predominant type of stromal cells in the skin, working with epithelial cells and skin-resident immune cells to constitute the cutaneous structure. These cells serve as vital components of the skin framework, primarily through the production of collagen [19]. However, the role of skin fibroblasts extends beyond structural support; they are integral to various physiological and pathological processes, including wound repair, healing, and the modulation of malignant and immune responses within the skin [19].

The functions of fibroblasts are largely mediated through the release of diverse substances in response to specific environmental signals. Fibroblasts detect these signals via their membrane-bound GPCRs [18], which are critical for numerous physiological functions. To date, over 800 GPCRs have been identified in the human genome. Many GPCRs are found in the cell membrane of fibroblasts, with fibroblasts in different organs containing different combinations of receptors [10].

The objective of this study was to investigate the expression of NPBWR1 and NPBWR2 in human dermal fibroblasts of mesenchymal origin, which were cultivated from human skin biopsies, utilising both genomic and proteomic methodologies. A range of approaches were implemented to accomplish this objective.

Immunocytochemical experiments confirmed that all fibroblasts analysed were of mesenchymal origin, as evidenced by specific immunoreactivity with the anti-vimentin antibody. Furthermore, these experiments established the presence of both receptors, NPBWR1 and NPBWR2, in all fibroblast samples.

Analysis of the genomic data indicated significant quantitative differences in the expression levels of the two receptors. Notably, the mRNA for the NPBWR2 receptor was expressed at levels several times higher than that of the NPBWR1 receptor. The relatively low expression of the NPBWR1 gene may explain the undetectable mRNA levels in some samples, as it is reasonable to assume that the gene copy number in these cases fell below the detection threshold of the employed analysis method.

However, at the protein level, we successfully demonstrated the presence of the NPBWR1 receptor in all tested cell lines. These findings are consistent with those reported by Philippeos et al. [20], who detected very low-level expression of genes for NPB, NPBWR1 and NPBWR2 in some samples of papillary or reticular human skin dermis.

The NPB/W signalling system has been implicated in a variety of important physiological processes. It plays a role in modulating pain transmission, regulating behavioural responses to stress, managing inflammatory neuropathies, and controlling feeding behaviours. Additionally, this system influences the activity of endocrine glands, regulates vascular smooth muscle tone, and contributes to the metabolism of adipocytes. These effects are primarily mediated through the receptors NPBWR1 and NPBWR2 [2]. Subcutaneous adipocytes, similar to the fibroblasts we examined, are derived from mesenchymal cells and express both NPBWR1 and NPBWR2. Prior research has explored the impact of the NPB/W signalling system on the proliferation and differentiation of various cell types. Notably, a study has indicated that NPB influences the proliferation of preadipocytes and facilitates their differentiation into mature adipocytes in porcine models [4]. Additionally, NPB exerts a proliferative effect on brown primary preadipocytes in rats, promoting the differentiation of white preadipocytes into adipocytes [4, 21].

Thus, the NPB/W signalling system exhibits a positive proliferative effect on cultured pig and rat adipocytes, a phenomenon that is mediated by NPBWR1 receptor [4, 21]. Conversely, both NPB and NPW have been identified as inhibitors of the proliferative activity in cultured rat calvarial osteoblast-like cells despite these cells also expressing NPBWR1 [8].

Intriguingly, NPB does not affect the proliferation of rat insulin-producing cells [5]. Similarly, our findings indicate that NPB does not influence the proliferation of human fibroblasts, while NPW shows a negative proliferative effect. Notably, skin fibroblasts display a significantly higher expression of NPBWR2 than NPBWR1, which may account for the observed differences in the effects of the signalling system on fibroblast and adipocyte proliferation.

These varying results across different cell types suggest that the mere presence of NPBWR1 is insufficient to mediate the positive proliferative effects of neuropeptides B and W. It is plausible that an additional cofactor, yet to be identified, is involved in the regulation of this process.

In fibroblasts, calcium signalling plays an essential role in various cellular processes, including proliferation, migration, extracellular matrix formation, and myofibroblast differentiation [22]. Our study demonstrated that intracellular calcium levels were significantly influenced by NPW, while NPB did not elicit a similar effect. This finding corresponds with our observation of a markedly higher expression of NPBWR2 compared to NPBWR1, as NPBWR2 exhibits a greater affinity for NPW [23], whereas NPBWR1 has an increased affinity for NPB [24].

Notably, we found that NPW leads to a decrease in intracellular calcium levels, which contrasts with its reported effects in vascular smooth muscle cells [6] and ventricular cardiomyocytes [25]. It is important to note that both studies mentioned above conducted in muscle cell types and utilised rat cells that exclusively express NPBWR1 [2]. This implicates calcium voltage-gated channels as active participants in those contexts. Consequently, we speculate that the effect of NPW on fibroblasts, which inherently lack calcium voltage-gated channels, may be mediated through an alternative pathway.

The function of NPW in regulating intracellular calcium levels could bear resemblance to neuropeptide Y (NPY), which exhibits differential actions based on the receptor involved. Specifically, NPY interaction with receptor Y1 results in enhanced calcium transients [26], whereas interaction with receptor Y2 leads to diminished calcium levels [27]. Future investigations should explore the potential interaction between NPBWR1 and NPBWR2, given that cross-talk among NPY receptors has been previously documented [28], suggesting a similar phenomenon may occur with NPW receptors.

Moreover, past research indicates that NPBWR2 is coupled with Gi/o proteins [29]. Therefore, we conclude that the NPW-mediated effect on calcium levels in human skin fibroblasts is likely facilitated through the inhibition of adenylate cyclase, resulting in decreased cAMP levels and subsequent reduction in PKA activity. This decreased PKA activity contributes to diminished activation of various calcium channels and reduced phosphorylation of IP3 receptors [30], collectively leading to an overall decrease in intracellular calcium levels.

This finding may explain the observed decrease in intracellular calcium levels after the application of NPW. The lower concentration of intracellular calcium suggests that NPW might act as an intracellular calcium chelator. This is supported by the significant reduction in fibroblast intracellular calcium levels when treated with 0.1 µmol/L of hNPW (33–62). The NPB/W signalling system may become activated under certain pathological conditions, such as fibrosis, where calcium signalling plays a significant role in the disease’s pathophysiology [31]. Research has shown that fibroblasts from patients with cystic fibrosis or cancer exhibit an increase in intracellular calcium concentration, highlighting the importance of calcium regulation in these cells. Moreover, intracellular calcium is essential for the migration of fibroblasts [32]. Variations in intracellular Ca2+ levels furthermore play a crucial role in determining whether cells commit to remaining in the premitotic interphase or transitioning into mitosis. Additionally, these variations can influence cell-to-cell adhesion by remodelling cortical actin and facilitating the recruitment of cadherins and beta-catenin into intercellular junctions [22]. Notably, it has also been observed that increased intracellular Ca2+ can facilitate wound healing [23, 24].

The wound healing process consists of three phases: haemostasis/inflammation, proliferation, and remodelling [33]. Calcium levels play a key role in the healing process, particularly during its initial phases [34]. However, during the final remodelling phase, elevated intracellular calcium may contribute to the excessive formation of scar tissue. A study conducted by Ishise et al. [35] in 2015 found that increased intracellular calcium levels in fibroblasts activate the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B (NF-

The precise sources of natural mediators for the receptors NPB and NPW within the skin remain to be fully elucidated. Current evidence confirms the presence of these mediators in the bloodstream, with NPB also identified in the skin dermis and subcutaneous adipose tissue [4, 20, 39]. Additionally, sensory nerve fibres may represent another potential source of these receptors, as NPB has been detected in neuron bodies within the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) [15], NPW, on the other hand, has not. These findings suggest that NPB and NPW may exert both endocrine and paracrine effects on skin fibroblasts.

In summary, we have successfully demonstrated the expression of the receptors NPBWR1 and NPBWR2 in human mesenchymal fibroblasts through both genomic and proteomic methodologies. However, it is noteworthy that the expression levels for NPBWR1 and NPBWR2 were insufficient for detection via WB analysis. Furthermore, our research indicates that this signalling system is involved in the regulation of intracellular calcium levels; specifically, hNPW (33–62) appears to modulate intracellular calcium signalling and decrease the concentration of Ca2+ within fibroblasts. Additional experiments will be necessary to comprehensively understand the mechanisms at play, especially in in vivo contexts.

In this study, we were not able to detect NPBWR2 in human dermal fibroblast through western blot, while similar antibodies were able to detect NPBWR2 in immunofluorescence analysis. This may relate to antibody specificity or receptor denaturation during western blot. To overcome this problem, one can use different methodology such as complete gel blot or mass spectrometry analysis for further validation of the results.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

SP, MCD designed the research study. SP, MCD, DJ, EP, OM, TC, MJ performed the research. RK provided help and advice. SP, DJ, EP, OM, TC, MJ analyzed the data. MCD, SP wrote the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethical Committee, University Hospital Pilsen and Faculty of Medicine in Pilsen, Charles University, Edvarda Beneše 1128/13, 30599 Pilsen – Czech Republic (email: etickakomise@fnplzen.cz) on 19th June 2019. WRITTEN INFORMED consent was obtained from any adults participating in this study.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments, which have significantly enhanced the quality of this work. I also wish to acknowledge Natalie Bergman (professional english translator, Pilsen, Czech Republic) and Dr. Nancy Linder (professional english translator, Laboratoire BIOCIS, BETIC/Peptlab, CY Cergy Paris Université, France) for their support in reviewing the English language. Special thanks to Ladislav Pecen (Statistician, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Medicine in Pilsen, Charles University, Czech Republic) for his support in analyzing the data.

This research was supported by the Cooperation Program, research area Medical Diagnostics and Basic Medical Sciences.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL26760.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.