1 Department of Geriatrics, Aerospace Center Hospital, Peking University Aerospace School of Clinical Medicine, 100049 Beijing, China

2 Department of Neurology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, 430000 Wuhan, Hubei, China

3 Department of Neurology, The Affiliated Hospital of Chifeng University, 024005 Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, China

4 Chifeng University Health Science Center, 024000 Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, China

5 Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Aerospace Center Hospital, Peking University Aerospace School of Clinical Medicine, 100049 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

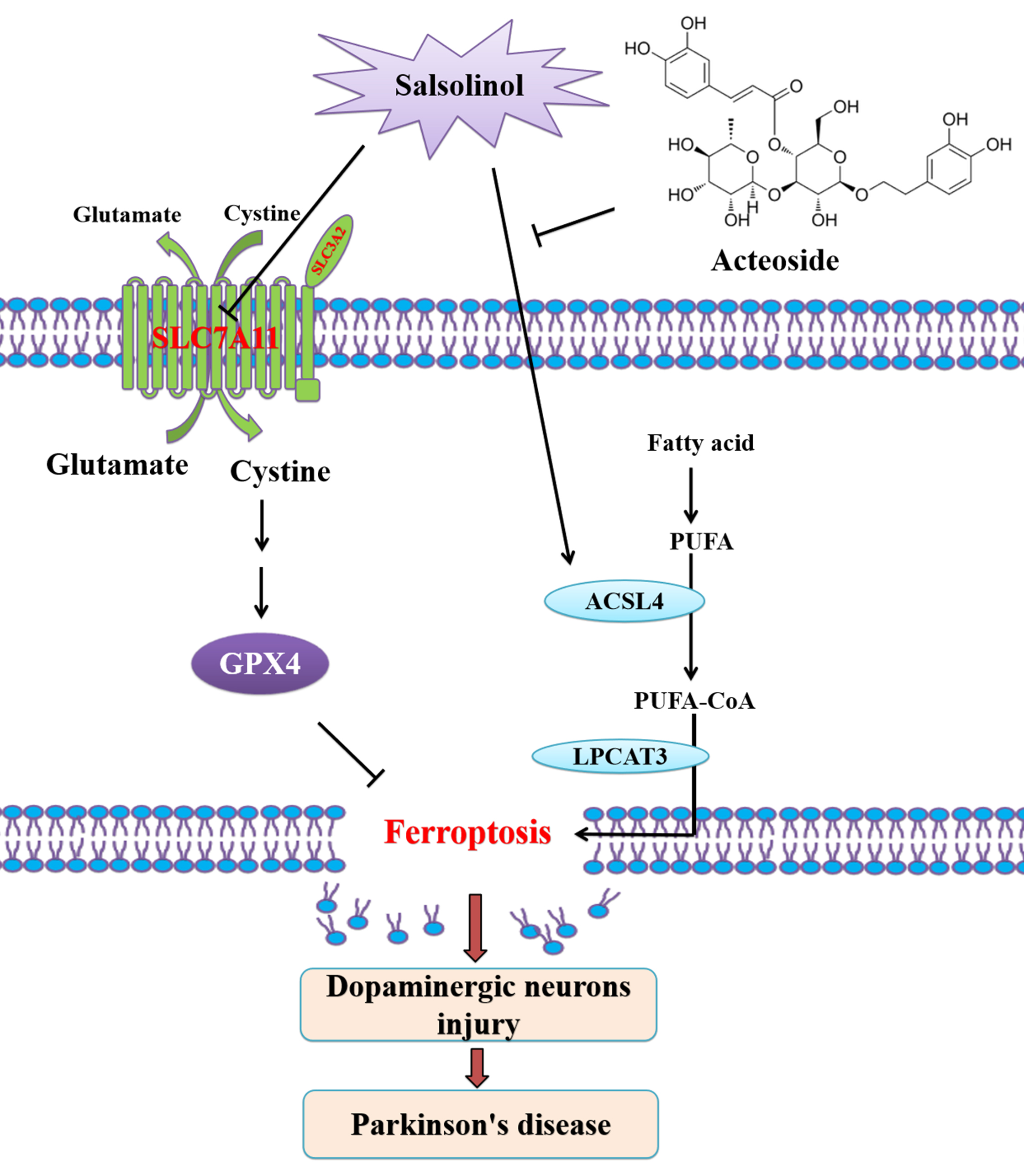

Salsolinol (SAL) is a dopamine metabolite and endogenous neurotoxin that exerts neurotoxicity to dopaminergic neurons and is involved in the genesis of Parkinson’s disease (PD). However, the machinery underlying SAL-induced neurotoxicity in PD is still being elucidated.

In the present study, we first used RNA-seq and KEGG analysis to examine differentially expressed genes in SAL-challenged SH-SY5Y cells. PD animal models were established and treated with acteoside. Cell viability assays, lipid peroxidation assessments (malondialdehyde [MDA] and 4-Hydroxynonenal [4-HNE]), immunoblot, and transmission electron microscopy were used to confirm acteoside-mediated inhibition of ferroptosis and its neuroprotective effect on dopaminergic (DA) neurons.

We found that ferroptosis-related pathway was enriched by SAL. SAL inducing ferroptosis through upregulating long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase family member 4 (ACSL4) in SH-SY5Y cells, which neurotoxic effect was reversed by ferroptosis inhibitors ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) and deferoxamine (DFO). Acteoside, a phenylethanoid glycoside of plant origin with a neuroprotective effect, attenuates SAL-induced neurotoxicity by inhibiting ferroptosis in in vitro and in vivo PD models through downregulating ACSL4.

The present study revealed a novel molecular mechanism underlying SAL-induced neurotoxicity via induction of ferroptosis in PD, and uncovered a new pharmacological effect against PD through inhibiting ferroptosis. This study highlights SAL-induced neurotoxicity via ferroptosis as a potential therapeutic target in PD.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- Parkinson’s disease

- salsolinol

- ferroptosis

- acteoside

- neuroprotection

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by dopaminergic neuronal loss in the substantia nigra pars compacta and intracellular inclusions called Lewy bodies (LB) [1, 2]. The interplay among aging, genetic susceptibility and environmental factors contribute to pathogensis of PD [3]. Salsolinol (SAL), an endogenous dopamine metabolite with structural similarity to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) with selective toxicity to nigral dopaminergic neurons, is considered being both an endogenous and an environmental compound to induce PD [4, 5]. Salsolinol is toxic to dopaminergic (DA) neurons in vitro and in vivo [4, 6, 7]. Several studies have been shown that SAL damages DA cells by inducing oxidative stress-dependent apoptosis [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Our previous study revealed that SAL induces PD through activating nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) dependent pyroptosis [15]. However, the machinery underlying SAL induces neurotoxicity in PD are still being elucidated.

Early studies suggested that SAL-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in the involvement of DNA damage and cytotoxicity [16, 17]. SAL and iron involve in redox cycling leading to the formation of ROS, and iron facilitates SAL-mediated oxidative damage-dependant neuronal cell death, which was attenuated by the iron-specific chelator deferoxamine (DFO) [18]. SAL induced neurotoxicity, enhanced ROS and decreased Low level of glutathione (GSH) levels in SH-SY5Y cells [19]. GSH can boost neurotoxicity in SAL-induced SH-SY5Y cells [20]. These studies strongly suggest that a novel regulated cell death (RCD), i.e., ferroptosis maybe contribute to SAL-induced neurotoxicity. Ferroptosis is a new form of RCD triggered by the toxic lipid peroxides on cellular membranes through inhibiting the antioxidant defense system and ensued accumulating iron-dependent ROS, which react with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) to damage the integrity of cell membranes [21, 22, 23, 24]. Mounting evidences supports ferroptosis as a critical player in the genesis of PD [25, 26, 27, 28]. A knowledge of the role of ferroptosis in SAL-induced neurotoxicity will not only provide insights into the genesis of PD but also may also prove vital in the development of an effective therapy.

Emerging evidence has shown that pharmacologically inhibiting ferroptosis to ameliorate dopaminergic neurons injury is a promising therapeutic target for PD treatment [24, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38]. Acteoside, a phenylpropanoid glycoside has been demonstrated various pharmacological activities, including neuroprotection [39]. It has been shown that acteoside exerts neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s disease from our previous study [40]. Acteoside also exerts neuroprotection against neurotoxicity in PD induced by rotenone [41] and 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) [42]. These observations were corroborated by our previous study which reported that acteoside inhibits NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis in PD [15]. It is tempting to speculate that whether acteoside inhibits SAL-induced neurotoxicity through inhibiting ferroptosis.

In the present study, we first used RNA-seq and KEGG analysis to examine differentially expressed genes in SAL-treated SH-SY5Y cells. We found that ferroptosis-related pathway was enriched by SAL. SAL induces ferroptosis through upregulating long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase family member 4 (ACSL4) in SH-SY5Y cells. The ferroptosis inhibitors DFO and ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) reversed neurotoxic effect of SAL. SAL inducing ferroptosis through upregulating ACSL4 in mice. Acteoside attenuates SAL-induced neurotoxicity by inhibiting ferroptosis in vitro through downregulating ACSL4. The present study revealed a novel molecular mechanism underlying SAL-induced neurotoxicity via induction of ferroptosis, and uncovered a new pharmacological effect of acteoside against SAL-induced neurotoxicity through inhibiting ferroptosis. This study highlights targeting ferroptosis as a potential therapeutic target in SAL-induced PD.

Cell Counting Kit-8 kit was purchased from Wanleibio (WLA074, Wanleibio, Shenyang, China). Acteoside (61276-17-3) and SAL (27740-96-1) were obtained from Winherb Medical Technology Inc (Shanghai, China). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium supplement was obtained from Gibco Invitrogen Corporation (#12800-017, OH, USA). ACSL4 antibody is from Abclonal (1:2000, A6826, Abclonal, Wuhan, China). Solute carrier family 7a member 11(SLC7A11) antibody is from Affinity (1:500, DF12509, Affinity, West Bridgford, UK). Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) antibody is from Abclonal (1:500, A1933, abclonal). 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) antibody is from Novus (1:100, MAB3249, Novus, Cambridge, UK). Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibody (1:500, WL01820), alpha-synuclein (

SH-SY5Y cells obtained from the ATCC were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin at 37 °C and 5% CO2 [15, 43]. All cell lines were validated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma. Both acteoside and SAL were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and stored at –20 °C. To induce cell injury, SH-SY5Y cells were incubated with indicated dose SAL for indicated times. To study the neuroprotective effects of acteoside, SH-SY5Y cells were pre-incubated with indicated dose of acteoside for 2 h, followed by treatment with 300 µM SAL for another 24 h.

Cell viability was tested using CCK-8 kits following the methods of manufacturer instructions. Briefly, cells under the logarithmic growth phase were seeded into a cell culture plate at 1

Animal welfare and experimental procedures were performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health, the United States) and the related ethical regulations of Aerospace Center Hospital (2023-023). Male C57BL/6J mice (2 months old, 18–22 g) were purchased from HUAFUKANG Company (Beijing, China). The mice were allowed to acclimatize to the laboratory environment for at least 1 week before the experiment. The mice were randomly divided into two groups (n = 15/group), i.e., control and SAL treatment groups as described in our previous study [15]. Briefly, Control group mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) administered PBS (vehicle) for nine consecutive days. All mice were killed using 100% CO2 narcosis for western blotting and transmission electron microscopy.

According to the kit instructions, the intracellular ROS kit (WLA131; Wanleibio, China), MDA kit (WLA048; Wanleibio, China), GSH kit (WLA105; Wanleibio, China), and 4-HNE kit (EU0187; Wuhan Fine, China) were used to measure the levels of ROS, MDA, GSH, and 4-HNE, respectively. The content of iron was measured using corresponding kits (E-BC-K881-M, Elabscience, Wuhan, China) following the methods of manufacturer instructions.

The differentially expressed proteins were tested using Western blotting, as described previously [15, 40].

The Harvested SH-SY5Y cells and mouse brains were successively fixed by paraformaldehyde and 1% osmium tetroxide at 4 °C. After dehydration by ethanol and acetone, SH-SY5Y cells and mouse brains were embedded by Epon 816 and cut into 100 nm-thick sections using an ultramicrotome (CM1860, Leica, Germany). After lead citrate staining, TEM (H-7650, Hitachi, Japan) was used to capture the images [44].

All data in present study were presented as the mean

To uncover the machinery underlying SAL-induced neurotoxicity, we first performed an RNA-seq analysis. Total RNAs were isolated and sequenced in SAL-treated SH-SY5Y cells or control cells. SAL challenge causes a total of 2826 genes (710 upregulated and 2116 downregulated) were differentially expressed (

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Salsolinol (SAL) induced ferroptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. (A) 1208 downregulated genes (green) and 719 up-regulated genes (red) was revealed by heatmap using RNA-Seq data in control and SAL-treated cells. (B) SAL-regulated genes were analysed by KEGG enrichment. SH-SY5Y was induced in the present or absent of 300 µM SAL for 24 h. (C) Volcano plot showed the differentially expressed genes. SAL (1–300 µM) treated SH-SY5Y cells for 24 h, then cell viability by CCK-8 (D), the levels of GSH (E), ROS production (F), intercellular iron (G), MDA (H), 4-HNE (I) detected by different kits and corresponding statistical results. (J) Western blotting of 4-HNE expression in SH-SY5Y as described in (D–I). The expression levels of (K) TH and

To further confirm that the SAL indeed mediates neurotoxicity through inducing ferroptosis in SH-SY5Y cells, we used the ferroptosis inhibitor deferoxamine (DFO) and ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) in SAL-induced cells. DFO and Fer-1 reversed SAL-induced ferroptosis and neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. The rescued phenotypes included attenuated loss of cell variability (Fig. 2A), increased TH and down-regulated

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Ferroptosis inhibitor reversed SAL induced ferroptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y cells were preincubated withferroptosis inhibitors deferoxamine (DFO) and ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) for 2 h and further incubated for 24 h after the addition of SAL (300 µM). (A) Then cell viability detected by CCK-8 assay. (B) The expression levels of TH and

We then tested whether SAL induces ferroptosis in the substantia nigra (SN) in mice. SAL causes loss of DA neurons in SN, evidenced by induced loss of TH-positive neurons and upregulated

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. SAL induced ferroptosis in Parkinson’s disease (PD) mice model. (A) Western blotting of TH and

Previous studies have revealed that acteoside, an antioxidative phenylethanoid glycoside confer neuroprotion in PD [41, 42]. Our previous study has revealed that acteoside exerts neuroprotective effect in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [40] and in PD [15]. However, whether acteoside alleviates SAL-induced neurotoxicity through inhibiting ferroptosis in PD is lack. The present study tested the neuroprotective effects of acteoside against SAL-induced ferroptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. We found that acteoside pre-treatment inhibits SAL-induced loss of cell viability (Fig. 4A). Meanwhile, acteoside rescued SAL-induced ferroptosis phenotypes including increased GSH level (Fig. 4B), decreased concentrations of ROS (Fig. 4C) and iron (Fig. 4D), decreased content of MDA (Fig. 4E) and 4-HNE (Fig. 4F,G) in SH-SY5Y cells. In accordance with these changes, acteoside decreased the expression of ACSL4 (Fig. 4H). This observation was corroborated by TEM analysis (Fig. 4I). In summary, these results suggest that attenuates SAL-induced neurotoxicity through inhibiting ferroptosis via downregulating ACSL4 in SH-SY5Y cells.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Acteoside reversed SAL-induced ferroptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y were incubated acteoside (1–30 µM) for 2 h, followed by incubation with 300 µM SAL for another 24 h. (A) Cell viability was tested by CCK8 assay. The levels of GSH (B), ROS production (C), intercellular iron (D), MDA (E), 4-HNE (F) detected by different kits and corresponding statistical results. (G) Western blotting of 4-HNE expression in SH-SY5Y cells as described in (A–F). (H) The expression levels of ACSL4 were determined by Western blot. (I) Representative electron microscopy image of SH-SY5Y cells as indicated groups (The scale bar = 1 µM). ***p

SAL is an endogenous DA metabolite functioning as a neurotoxin to induce DA neuronal injury and is involved in the genesis of PD [14]. Mounting evidences have shown that SAL induces apoptosis [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] and pyroptosis [15] in DA neuron. Despite these progresses, more mechanistic insight into the role of SAL in PD are not well uncovered. The present study aims to determine whether SAL induces ferroptosis in vitro and in vivo, and meanwhile delineate whether acteoside mediates neuroprotection against SAL-induced neurotoxicity through inhibiting ferroptosis. We demonstrated for the first time that induction of ferroptosis by SAL contributes to the pathogenesis of PD in vitro and in vivo. Also we revealed that acteoside alleviated SAL-induced dopaminergic neurons injury through inhibiting ferroptosis via downregulating ACSL4 in SH-SY5Y cells and mice.

In recent years, evidence have shown that ferroptosis as a distinct form of RCD, characterized by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation (LPO) [24, 45]. Several pathological features of PD include dyshomeostasis of iron, oxidative stress, LPO, and GSH depletion are all related to ferroptosis [24, 46]. Since term ferroptosis that is characterized by iron dysregulation, LPO, and GSH depletion was coined in 2012, scientists have begun to revisit the contributions and role of the aforementioned pathological signatures of PD to the disease genesis. A ferroptosis hypothesis is emerging in PD, which states that ferroptosis plays a vital role in the genesis of PD [24]. The direct role of ferroptosis contributes to the development of PD was confirmed in vitro and in vivo model [47, 48].

The neurotoxins, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) [49], rotenone [50], MPTP [51], and 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) [52] cause PD through inducing ferroptosis in vitro and in vivo PD models. Salsolinol, a DA metabolite with structural similarity to MPTP functions as a neurotoxin that induces DA neuronal injury has been shown to involve in PD pathogenesis [4, 5, 6, 7]. SAL promotes production of ROS [16, 53], decreased GSH levels and cell viability in SH-SY5Y cells [19]. Decreased GSH boosts SAL-induced toxic effect in SH-SY5Y cells [20] and iron facilitates SAL-mediated neuronal cell death, which were attenuated by the iron-specific chelator DFO [18]. These studies strongly suggest that ferroptosis maybe contribute to SAL-induced neurotoxicity. These earlier studies prompted us to postulate that salsolinol maybe induce ferroptosis to cause PD. Indeed, our present study revealed that SAL enriched ferroptosis-related pathway, which was validated by SAL-induced in vitro and in vivo models (Figs. 1,2,3).

The polyunsaturated fatty acid-containing phospholipids (PUFA-PLs) are the substrates for LPO during ferroptosis [24]. ACSL4 cooperates with lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) to generate the lipid drivers of ferroptosis [24]. ACSL4 mediates the ligation of the free adrenic acid (ADA) and arachidonic acid (AA) the two long-chain PUFAs to CoA, respectively generating ADA-CoA and AA-CoA (i.e., PUFA-CoAs). Then, these PUFA-CoAs are re-esterified and incorporated into PLs by LPCAT3 to produce PUFA-PLs, which include AA -phosphatidylethanolamine [PE] and ADA-PE). SAL induces ferroptosis through upregulating ACSL4 in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1), which neurotoxic effect was reversed by ferroptosis inhibitors DFO and Fer-1 (Figs. 2,3). These results indicated that SAL induces ferroptosis through upregulating ACSL4. A mounting study has demonstrated that pharmacologically inhibiting ferroptosis by bioactive small-molecule compounds could be as a therapeutic regimen for PD [24]. Inhibition of ACSL4 activity may form a promising strategy for early intervention of PD [48]. Our present study showed that acteoside downregulated ACSL4 in SAL-induced SH-SY5Y cells and mice, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis to attenuate neurotoxicity in PD (Fig. 4). The strengths of present study is that we for the first provided the evidence that SAL induces ferroptosis by activating ACSL4 in SH-SY5Y cells and mice, and acteoside inhibits SAL-induced ferroptosis by suppressing ACSL4. However, there are some limitations of the present study, i.e., SAL maybe induces ferroptosis in PD by inhibiting other ferroptosis inhibirs (such solute carrier family 7a member 11/glutathione peroxidase 4 [SLC7A11/GPX4]) or activating other ferroptosis inducers (such as iron pathway), which remains an open conundrum for future investigate on. Our ongoing studies are centering on how other pathways and mechanisms that may mediate SAL-induced ferroptosis.

Taken together, the present results indicate that SAL induces ferroptosis through upregulating ACSL4. Acteoside attenuates SAL-induced neurotoxicity by inhibiting ferroptosis through downregulating ACSL4 in SH-SY5Y cells and mice. The present study revealed a novel molecular mechanism underlying SAL-induced neurotoxicity via induction of ferroptosis in PD, and uncovered a new pharmacological effect of acteoside protecting against PD through inhibiting ferroptosis. This study highlights SAL-induced neurotoxicity via ferroptosis as a promising therapeutic target in PD.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

YW, SW, QL and HW conceived of and designed the study. SW, HW and YW performed experiments and analyzed data. HW, HS and QL provided administrative support. YW, SW and HW wrote the manuscript. HW, SW, QL, HS and YW analysed and interpreted the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The research received approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of Aerospace Center Hospital (2023-023).

We would like to express my gratitude to all those who helped me during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This work was supported in part by the Science Foundation of AMHT (2021YK05 and 2024YK05), The scientific research fund of aerospace center hospital (YN202305), Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (IMAR) (2022MS08046), Science Foundation of Universities of IMAR (NJZY23028), and Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Key Laboratory of human genetic diseases (YC202305, YC202304), Master’s Student Science Innovation Project of IMAR (S20231204Z) and Foundation of Inner Mongolia Minzu University (NMGSS2128).

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Dr. Hongquan Wang is the Guest Editor and Editorial Board member of the journal. Dr. Yumin Wang is the Guest Editor member of the journal. Hongquan Wang and Yumin Wang had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Xudong Huang.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.