1 Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Research Centre of Medical Genetics, 115478 Moscow, Russia

2 Department of Public Health, National Research Institute of Public Health n.a. N.А. Semashko, 105064 Moscow, Russia

3 Research Department, N. A. Alexeev Clinical Psychiatric Hospital №1, 115447 Moscow, Russia

Abstract

A number of association studies have linked ribosomal DNA gene copy number (rDNA CN) to aging and pathology. Data from these studies are contradictory and depend on the quantitative method.

The hybridization technique was used for rDNA quantification in human cells. We determined the rDNA CN from healthy controls (HCs) and patients with schizophrenia (SZ) or cystic fibrosis (CF) (total number of subjects N = 1124). For the first time, rDNA CN was quantified in 105 long livers (90–101 years old). In addition, we conducted a joint analysis of the data obtained in this work and previously published by our group (total, N = 3264).

We found increased rDNA CN in the SZ group (534 ± 108, N = 1489) and CF group (567 ± 100, N = 322) and reduced rDNA CN in patients with mild cognitive impairment (330 ± 60, N = 93) compared with the HC group (422 ± 104, N = 1360). For the SZ, CF, and HC groups, there was a decreased range of rDNA CN variation in older age subgroups compared to child subgroups. For 311 patients with SZ or CF, rDNA CN was determined two or three times, with an interval of months to several years. Only 1.2% of patients demonstrated a decrease in rDNA CN over time. We did not find significant rDNA CN variation in eight different organs of the same patient or in cells of the same fibroblast population.

The results suggest that rDNA CN is a relatively stable quantitative genetic trait statistically associated with some diseases, which however, can change in rare cases under conditions of chronic oxidative stress. We believe that age- and disease-related differences between the groups in mean rDNA CN and its variance are caused by the biased elimination of carriers of marginal (predominantly low) rDNA CN values.

Keywords

- rDNA

- ribosomal gene

- copy number variation

- cystic fibrosis

- schizophrenia

- dosage effect

Copy number variants (CNVs) are structural genomic repetitive elements (repeats) ranging in size from a thousand to several million base pairs per copy [1, 2]. Repetitive elements comprise more than 70% of the human genome. Some of the repeats are clustered into tandem arrays. Tandem repeats are organized in a head-to-tail orientation and are characterized by a pronounced quantitative polymorphism. The tandem repeats play a principle role in the functioning of the nuclear chromatin through its regulation and spatial organization. CNVs of the tandem repeats have been implicated in many diseases [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9].

Ribosomal repeats (ribosomal genes, ribosomal DNA [rDNA]) are a special type of tandem repeat. Ribosomal genes encode the ribosomal RNA (rRNA) species that form the backbone of the ribosome. The human genome includes hundreds of rDNA copies (Fig. 1A), which are arranged in tandem arrays on five acrocentric chromosome pairs 13, 14, 15, 21, and 22. Each rDNA unit codes for a 47S pre-rRNA that is processed into the 18S rRNA (for the small ribosomal subunit) and the 5.8S and 28S rRNAs (for the large ribosomal subunit). During interphase, the ribosomal repeats form the structure of the nucleolus, where rDNA transcription and the initial stages of ribosome biogenesis occur. The biogenesis of ribosomes determines the ability of a cell to successfully proliferate, perform its functions, and respond to genotoxic stress. Dysregulation of rRNA biogenesis has been implicated in a series of human pathologies [10]. One of the factors that cause rRNA biogenesis is the copy number (CN) of the ribosomal genes [11, 12].

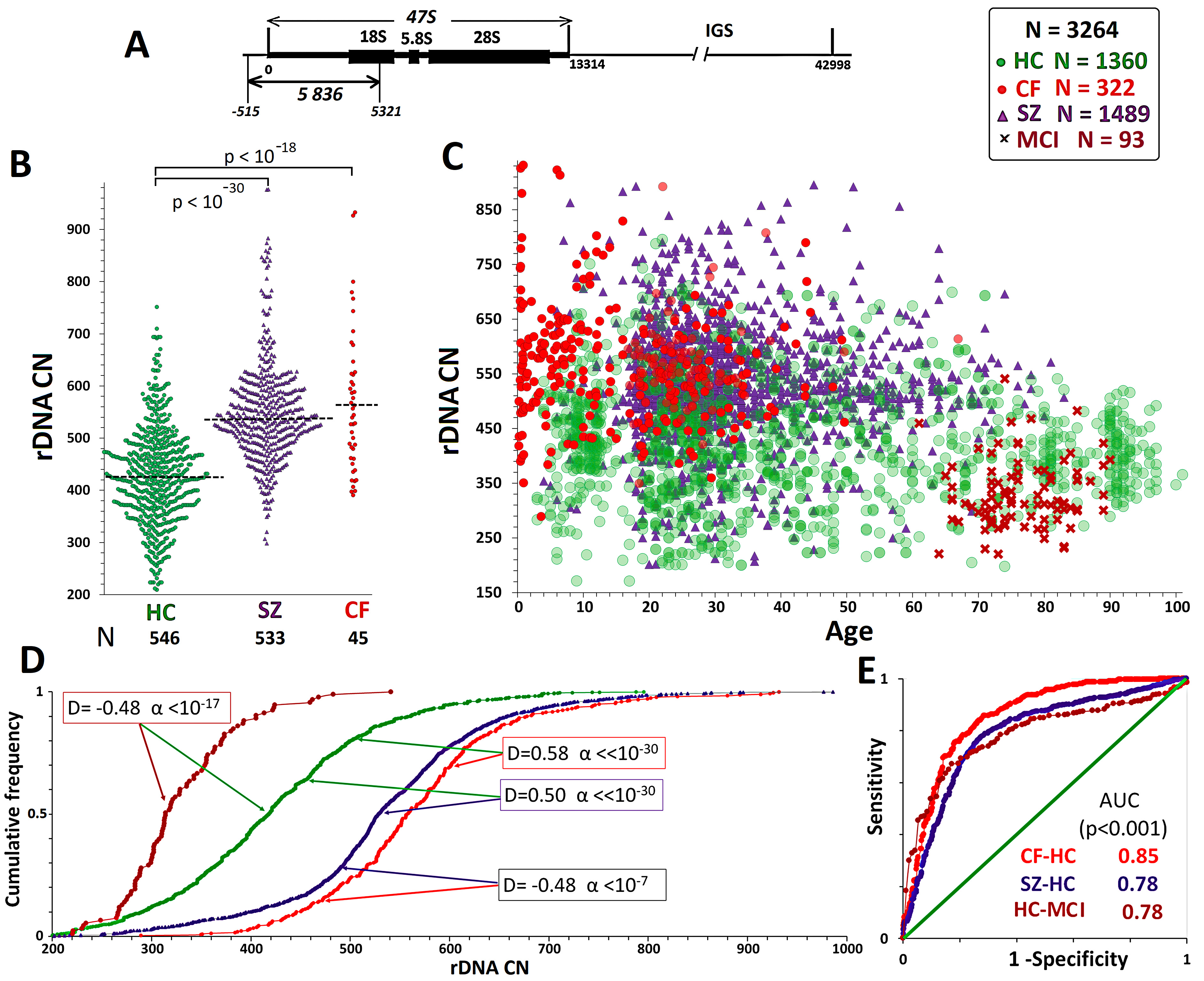

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Quantification of rDNA copy number in a general sample that includes all the groups studied. (А) Organization of ribosomal repeats. One copy of the repeat includes three rRNA genes and three transcribed spacers (transcribed region of rDNA) and a non-transcribed intergenic spacer. Probe p(ETS-18S) (fragment of rDNA from –515 to 5321 relative to the transcription initiation point, HSU 13369, GeneBank) was used for human rDNA detection. (B) rDNA CN in the НC, SZ, and CF groups, which were analyzed in this study. (C) Distribution of rDNA CN by age in the analyzed groups. The study findings (1124 DNA samples) are combined with the data previously reported by our group. (D) Comparison of rDNA CN distributions in various groups. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov (D and

The nucleolus consists of three rDNA fractions, which are distinguished by the transcription activity, methylation level, and the presence of nucleosomal organization. The fractions of active and poised (potentially active) repeats are euchromatic, hypomethylated at CpG sites, and marked with histone modifications typical for transcriptionally active genes. The rDNA CN of the active rDNA copies is estimated to be 30% to 50% of the total rDNA copies in the cell [13, 14, 15]. A part of inactive rDNA copies in the nucleolus is assumed to be methylated at CpG sites within the rDNA promotor region and able to reactivate under certain conditions. About 10% of human blood cell DNA samples contain inactive hypermethylated rDNA copies. These copies are unable to reactivate and are located in the peripheral regions of the nucleolus. They constitute heterochromatin that encompasses the nucleolus. There is a positive correlation between the total rDNA CN in the genome and the number of active or methylated copies [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27].

The rDNA function is not limited to ribosome biogenesis. The rRNA gene arrays constitute a center from which the stability of the whole genome is regulated and the cell’s lifespan is controlled [28, 29, 30]. The rDNA contributes to global chromatin regulation. The rDNA arrays have thousands of contacts in the folded genome, with rDNA-associated regions and genes dispersed across all chromosomes [31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36].

The available literature suggests that the variability of rDNA is an important aspect of normal cell physiology and phenotypic variation [16, 17, 37, 38, 39]. Neurodegenerative disorders, psychiatric diseases, and cancer are associated with changes in rDNA CN. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease are accompanied by an increase in rDNA CN in the brain [40, 41]. On the other hand, a decrease in rDNA CN in the blood leukocytes of patients with MCI has been observed [42]. Studies that had used experimental methods found an increase in rDNA CN in the blood leukocytes and brain of patients with schizophrenia (SZ) [43, 44, 45, 46]. A very recent analysis of the blood transcriptomes of SZ patients vs. healthy controls showed that the genes most influential in clustering to distinguish between SZ and controls were enriched in pathways related to the ribosome biogenesis system [47], thus indirectly corroborating the upregulated ribosome biogenesis in SZ, which may be underpinned by the elevated rDNA CN in the patients. However, a study using a bioinformatics approach did not identify differences in rDNA CN in the genomes of healthy individuals and patients with SZ [18]. A large number of rDNA copies are contained in the blood leukocytes of patients at high risk of lung cancer [48]. It has been shown that rDNA CN is unstable in human cancers [49, 50]. Recently, rDNA was shown to be positively correlated with neutrophil levels in the blood, a marker often linked to renal dysfunction, and negatively correlated with body weight [16, 17].

A number of association studies have linked rDNA CN with aging. Johnson and Strehler [51] were the first to discover aging-related loss of rDNA in neurons. Age-dependent loss of rDNA was found in beagle dog brain tissues; mouse brain, spleen, and kidney tissues; human myocardium and cerebral cortex; and human adipose tissue [52, 53, 54, 55]. Cytogenetic studies [56, 57] showed a decrease in the number of silver-stained nucleolus organizer regions per cell, that is, a decrease in the number of transcriptionally active rDNA clusters, with aging, which may be explained by either a deletion of rDNA repeats, or a full repression of the transcription from an rDNA array or several arrays. By contrast, a several-fold increase in rDNA CN has been found in the liver [58] and bone marrow cells [59] of old mice compared to young ones. However, some studies have not shown a correlation of changes in genomic rDNA content with aging. Rather, several reports have documented that rDNA CN is largely stable during normal aging [41, 60, 61, 62].

The conflicting data among studies regarding rDNA CNVs in health, disease, and aging seem to result from the complicacy of rDNA quantification [33, 43, 44, 45, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67]. Quantitative rDNA analysis using genome sequencing results is critically dependent on the technical details of library preparation. For the same cell lines, data on rDNA content obtained from the analysis of several libraries in different centers differ [33]. rDNA is a very poor template for Taq polymerase. This is due to an anomalously high GC pair content, unequal methylation of different copies, tandem nature of the repeats, increased rDNA damage, and the presence of proteins tightly bound to rDNA, in DNA samples [43, 63]. To adjust for the contribution of the aforementioned factors to rDNA quantification, we developed a variation of the hybridization technique using long non-radioactively labeled DNA probes (non-radioactive quantitative hybridization [NQH] technique). This method does not depend on the level of oxidation and fragmentation of the DNA template [43]. With this approach, we revealed pronounced variation in the distribution of healthy subject DNA samples in different age groups (16–91 years old) by rDNA CN values [64]. We also found increased rDNA CN in patients with SZ [43, 44, 45, 65] and cystic fibrosis (CF) [66, 67].

SZ is a multifactorial disease with a heritable component of 70–80% [68]. CF is a monogenic disease caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene on chromosome 7 [69, 70]. An association between the pathology and high levels of oxidative stress and DNA damage in primary and cultured cells of the patients has been reported for both SZ [45, 71, 72, 73, 74] and CF [75, 76, 77]. The elevated rDNA CN in the genomes of these completely different patient groups is intriguing and requires additional experimental corroboration and a greater understanding. There are no data in the literature on changes in rDNA CN in the same individuals over the course of their life. In addition, data on the possible heterogeneity of cells of different organs of one organism or cells of one cell population according to the rDNA CN parameter for humans are extremely scarce. In the present study, the following four groups were assessed. (1) We additionally quantified rDNA in 1124 DNA samples. Batches of DNA samples from different groups (healthy control (HC), SZ, and CF) were isolated from blood and analyzed within the same experiment to directly confirm the difference in rDNA CN in the genomes of controls and patients. (2) For the first time, rDNA CN was identified in the DNA isolated from the leukocytes of 105 long livers (90–101 years old). (3) For the first time, we monitored the changes in rDNA CN in leukocytes over several years in diseases that are accompanied by chronic oxidative stress (SZ and CF). (4) The variation in rDNA CN in eight different organs of the same patient and in the cells of the same fibroblast population was studied for the first time.

Finally, we conducted total comparative analysis of rDNA content in the genomes of the four groups for the entire sample of cases and HCs, whose DNA samples were assayed both previously and in the present study (N = 3264).

The CF group consisted of 322 patients with CF aged 0.21 to 66.7 years, who had been registered in the ‘Register of Cystic Fibrosis Patients in the Russian Federation’ database (https://mukoviscidoz.org/doc/registr/_Registre_2022.pdf). CF was diagnosed according to European Cystic Fibrosis Society best practice guidelines [78]. The age subgroups did not significantly differ by sweat test results or sex. We found that the proportion of patients with a ‘mild’ genotype increased with age, from 2.6% in the subgroup under 10 years old to 75% in the group of patients older than 31. With increasing patient age, there was also an increase in the number of patients infected with Pseudomonas аaeruginosa (р

The tested cohort included 1489 inhabitants of Moscow city and the Moscow region (Table 1). The data for 956 patients were previously published [44]. Within the framework of the present study, the DNA samples of 533 patients were analyzed. The patients were hospitalized in N.A. Alexeev Clinical Psychiatric Hospital #1 because of SZ aggravation. Patients with SZ included those with long-term antipsychotic therapy for a chronic disease and first-episode drug-naïve cases. The patients were assessed using the structured Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. According to International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) criteria, paranoid SZ (F20.00 or F20.01) was diagnosed. The diagnoses were validated according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) criteria. Quetiapine, risperidone, paliperidone, haloperidol, chlorpromazine, clozapine, olanzapine, and ziprasidone were the standard antipsychotics administered for the treatment of acute episodes.

| Index | HC | SZ | CF | MCI | ||

| N | 1360 | 1489 | 322 | 93 | ||

| Sex (men) | 62% | 59% | 49% | 29% | ||

| Age | Mean | 40 | 32 | 18 | 76.6 | |

| Range | 3–101 | 5–83 | 0.2–67 | 61–90 | ||

| Median | 32 | 29 | 19 | 76 | ||

| rDNA copy number | All | Mean | 422 | 534 | 567 | 330 |

| Range | 171–796 | 202–986 | 289–932 | 220–541 | ||

| Median | 418 | 528 | 556 | 314 | ||

| CV | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.18 | ||

| Group 0–16 y.o. | N | 277 | 44 | 142 | ||

| Mean | 438 | 565 | 587 | |||

| Range | 171–751 | 303–986 | 289–932 | |||

| Median | 434 | 519 | 585 | |||

| CV | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.20 | |||

| Group 17–40 y.o. | N | 530 | 1130 | 169 | ||

| Mean | 422 | 534 | 547 | |||

| Range | 171–796 | 202–977 | 350–892 | |||

| Median | 414 | 531 | 547 | |||

| CV | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.14 | |||

| Group 41–72 y.o. | N | 340 | 304 | 12 | 28 | |

| Mean | 423 | 527 | 604 | 319 | ||

| Range | 205–699 | 229–896 | 461–790 | 221–460 | ||

| Median | 421 | 522 | 609 | 310 | ||

| CV | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.17 | ||

| Group 73–89 y.o. | N | 118 | 11 | 65 | ||

| Mean | 396 | 531 | 336 | |||

| Range | 198–541 | 371–696 | 220–321 | |||

| Median | 392 | 528 | 319 | |||

| CV | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.19 | |||

| Group 90–101 y.o. | N | 105 | ||||

| Mean | 402 | |||||

| Range | 289–519 | |||||

| Median | 401 | |||||

| CV | 0.14 | |||||

CV, coefficient of variation; CF, cystic fibrosis; HC, healthy control; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; rDNA, ribosomal DNA; SZ, schizophrenia; y.o., year old; CN, copy number.

The group of children with very early SZ onset was recruited using the clinical psychopathologic approach from the Child Psychiatry Department of the Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Mental Health Research Center” (Moscow Russia). The group was described in detail in our previous publication [79]. DNA samples isolated from various tissues of a patient with SZ (male, 54 years old, chronic form of paranoid SZ) were obtained from a SZ DNA sample collection from the Molecular Biology Laboratory of the Research Centre for Medical Genetics (RCMG; Moscow, Russia).

The group of patients with MCI comprised 93 participants aged 61–91 years. All patients participated in the Rehabilitation Program “Memory Clinic” developed at N.A. Alekseev Psychiatric Hospital #1. The results of the program [80] and data obtained for this patient group [42] have been published.

DNA samples from HCs were obtained from the Molecular Biology Laboratory of the RCMG. This cohort included mentally healthy subjects aged 3–91 years (N = 1260), who were not affected by any genetic pathology, cognitive impairment, or mental illness. Blood samples of long livers (91–101 years old, N = 105) were obtained from the inhabitants of the Moscow Nursing Home for War Veterans.

DNA isolation from blood cells and the NQH technique were performed as previously described [43]. Isolated leukocytes were used for most of the tests. A small amount of DNA samples from patients with SZ (~15%) were isolated from whole blood. Briefly, DNA was isolated after cell lysis via extraction with organic solvents (2% sodium lauryl sarcosylate (L9150, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 0.04 M EDTA (E8008, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)) and subsequently treated with 150 µg/mL RNAase A (45 min, 37 °C; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 200 µg/mL proteinase K (24 h, 37 °C; Promega Co., Madison, WI, USA). Proteinase K treatment is critically important for maximum effectiveness of rDNA isolation [65]. The lysate samples were extracted with an equal volume of phenol (77608 Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA)/chloroform (Chimmed, Moscow, Russia)/isoamyl alcohol (Chimmed, Moscow, Russia) (25:24:1), phenol and chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (24:1). DNA was precipitated after adding 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (GRM2966, NeoFroxx Gmbh, Einhausen, Germany) (pH 5.2) and 2.5 volume of ice-cold ethanol. Only freshly distilled solvents were applied for extraction, and 8-hydroxyquinoline (252565, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to stabilize the phenol. Finally, the DNA was centrifuged at 10,000 g at 4 °C for 15 min, washed with 70% ethanol (v/v), dried and dissolved in water. The efficiency of NQH is mostly determined by the accuracy of DNA quantification. We conducted quantification by obtaining a crude estimation of the initial DNA amount by ultraviolet spectroscopy, and performing final DNA quantification fluorimetrically using the PicoGreen dsDNA Quantification Reagent (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, USA). DNA solutions with the same concentration (20 ng/µL) were prepared for the NQH method.

For human rRNA detection, the p(ETS-18S) probe was used, which was a 5.8 kb long rDNA fragment that encompassed a region from position –515 to position 5321 with reference to the transcription initiation point (HSU 13369; GenBank accession No. U13369). It was cloned into EcoRI site of pBR322 vector (https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/pbr322) and biotinylated using a nick translation kit (Biotin NT Labeling Kit; Jena Bioscience GmbH, Jena, Germany). The membrane (ExtraC) was wetted using a solution of 10

HSF-61 human skin fibroblasts (HSFs) were suspended and seeded into wells (N = 40) at a density of 10–20 cells per well, and cultured for 3 weeks with regular replenishment of the culture medium. Then DNA was isolated from the 32 wells and quantified. We further estimated the rDNA abundance in the samples from each well using NQH.

All cell lines were validated by short tandem repeat profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma.

The relative standard error for NQH was a mere 5

In this study, rDNA was quantified in 1124 DNA samples (Fig. 1B) isolated from the blood leukocytes of HCs (N = 546, including 105 long livers

Table 1 and Fig. 1 show that the rDNA CN in the four groups was in the order of: CF group

We divided the НС group into five age subgroups:

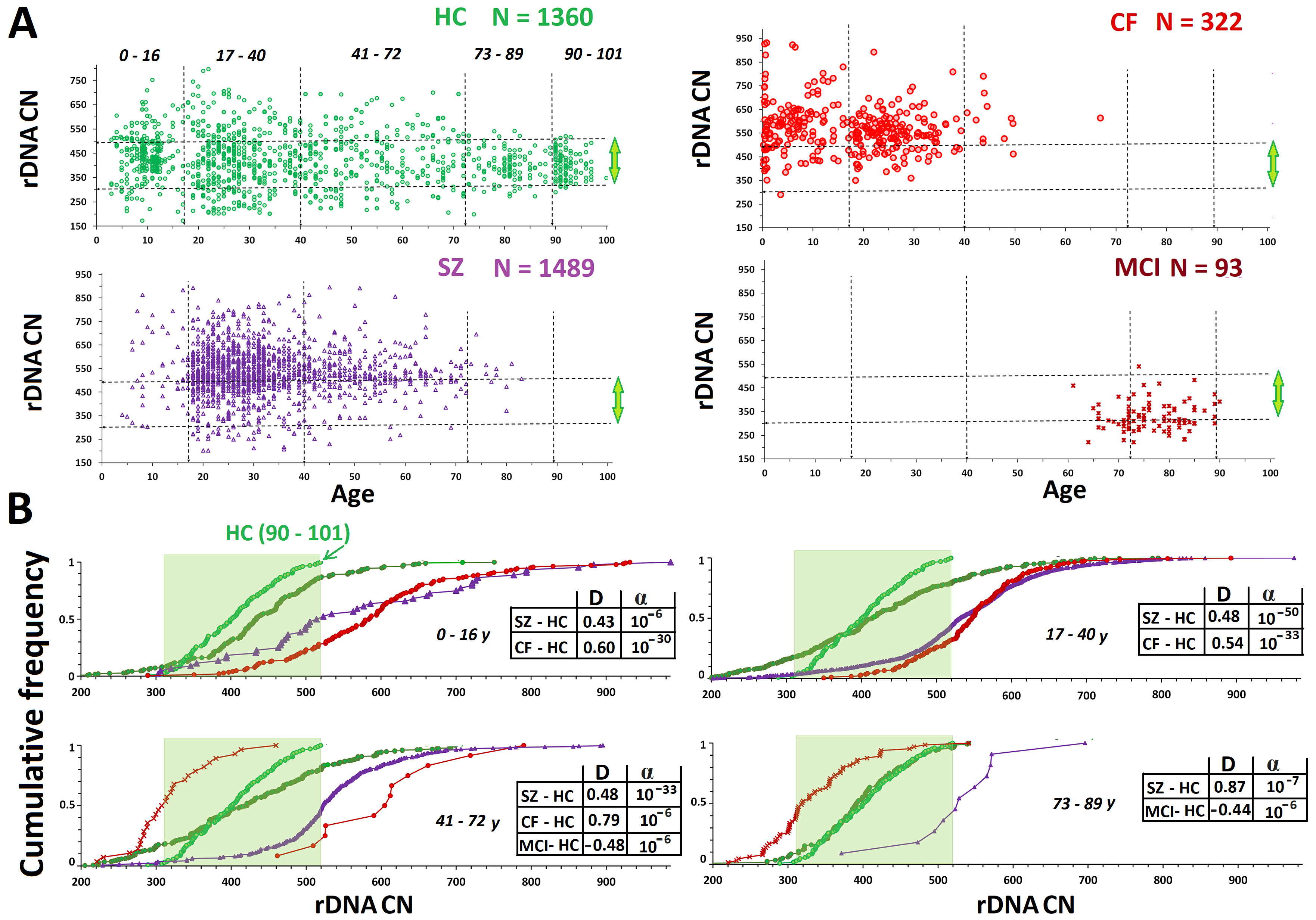

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Analysis of rDNA copy number variants (CNVs) in the HC, CF, SZ, and MCI groups. (A) Analysis by age of rDNA CN in the HC, CF, SZ, and MCI groups. The vertical dotted lines divide the five age subgroups. The horizontal lines divide the subgroups with high (

The CF group (N = 45) had significantly higher rDNA CNs than the НС group (Fig. 1В). This finding corroborates our previous findings [66, 67]. In the CF group (N = 322, aged 0.21–66.9 years), only one DNA sample with rDNA CN less than 300 was found (289 copies in a patient aged 3 years) (Fig. 2A). Genomes with rDNA CN less than 350 copies were seldom found among CF patients; 60–90% of DNA samples in the different age subgroups harbored 500+ rDNA copies (Fig. 2В). There was no association between rDNA CN and the patient’s sex. The maximum range and maximum CVs were observed for the younger CF subgroup (0.21–16 years old) (Table 1). The maximum rDNA abundance (880–932 copies) was found in DNA samples from patients under 7 years old (Fig. 2). The 0.21- to 16-year-old CF subgroup had higher rDNA CNs than the 17- to 40-year-old CF subgroup (p

Expansion of the SZ cohort by an additional 533 participants did not change the results previously reported [43, 44, 45]. The patients harbored more rDNA copies than the HCs (Figs. 1,2 and Table 1). In the SZ group, similar to the НС and CF groups, the range and CVs of rDNA CN decreased with age. The mean rDNA CNs did not differ between the older and younger SZ subgroups. Maximum rDNA CNs (890–986) were found in the younger SZ subgroup (5–16 years old). The rDNA CNs were the same between the two sex subgroups.

For comparison, Figs. 1,2 present published data for the MCI group (61–91 years old) [42]. The group of elderly patients with MCI had lower rDNA CN than the other three groups. The genomes of 35% of patients harbored less than 300 rDNA copies, whereas only one patient harbored more than 500 rDNA copies. In the control age-matched HC subgroup (61–91 years old), merely 7% of genomes harbored less than 300 rDNA copies. The rDNA CN of the MCI group did not depend on the patient’s sex.

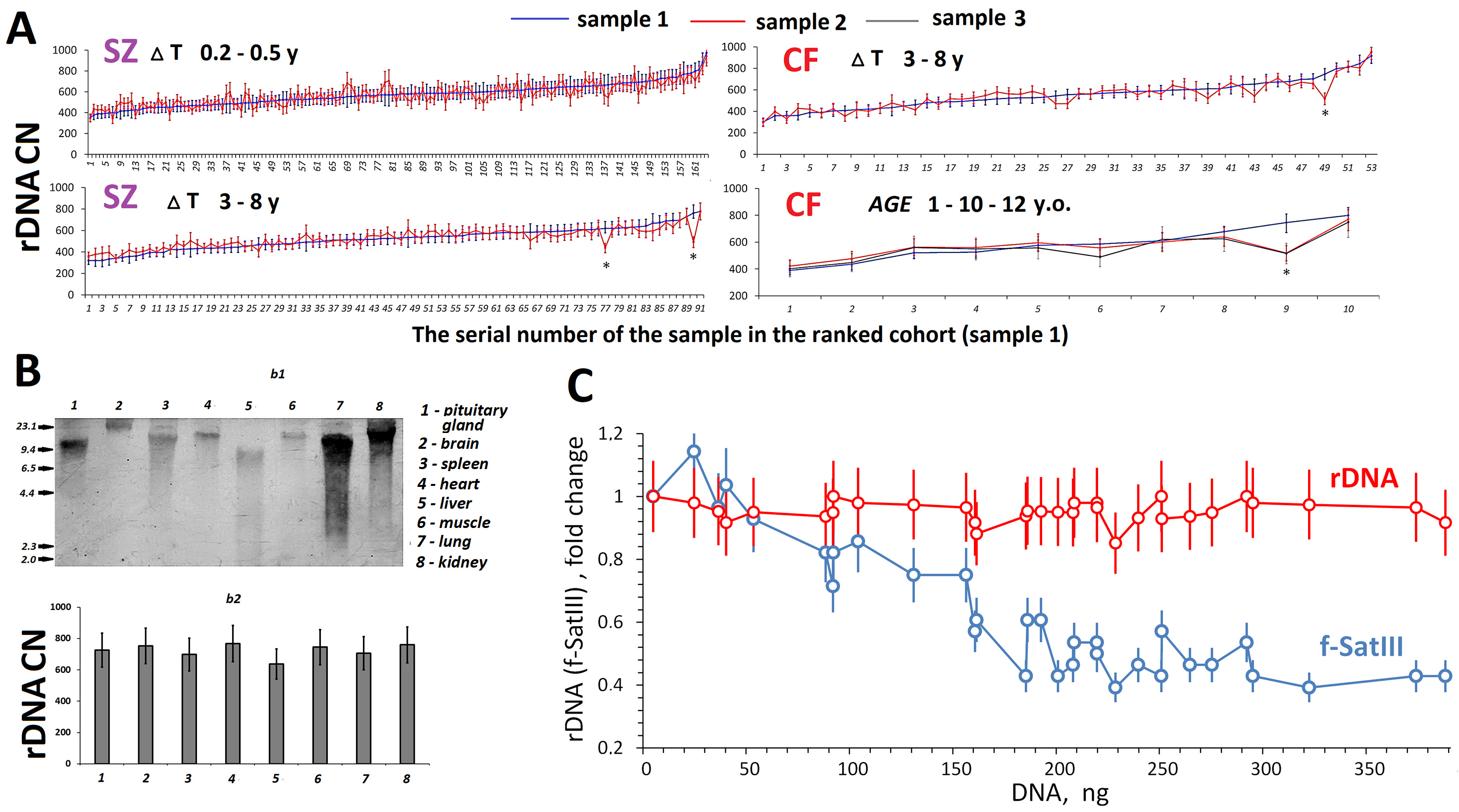

Fig. 3A shows data on the rDNA contents in DNA samples isolated from the blood leukocytes of the same SZ and CF patients, but at different times. The samples were stored at –70 °C and the DNA samples from the same individual were assayed simultaneously. For 255 patients with SZ and 63 patients with CF, blood was sampled two or three times, with an interval of several months (before and after treatment) to several years. Of the 311 DNA sample pairs obtained from patients with SZ or CF, as few as four pairs (1.3%) demonstrated a decrease in rDNA content over time compared to the baseline content in the first sample. No rDNA amplification was revealed in all of the cases.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Time dynamics of rDNA copy numbers (CN) in leukocytes and variation of rDNA CN in different cells from one subject or cell culture. (A) Changes in rDNA CN in DNA samples isolated from blood cells of the same subjects at various time intervals (

Fig. 3B shows rDNA abundance (4 h after death) in different organs of the same 54-year-old patients with SZ. DNA was isolated from pituitary, brain, spleen, heart, liver, muscle, lung, and kidney cells. To measure the degree of rDNA damage, the isolated samples were assayed using blot hybridization with a biotinylated DNA probe (Fig. 3B,b1). The most fragmented rDNA was found in DNA samples isolated from the hypophysis and liver; the longest fragments did not exceed 9 kilobase pairs. The rDNA content was measured using NQH in the eight DNA samples and appeared the same (720

To estimate the rDNA CNVs within the human skin fibroblast (HSF-61) strain, we conducted a cloning experiment. Fig. 3C [81] shows the dependence of rDNA CN on the amount of cellular DNA (the number of cells). The rDNA CN was the same for all DNA samples (N = 32), taking into account the standard error of the method. For comparison, data for f-SatIII repeat (blue) obtained for this HSF-61 strain are plotted in the figure. We previously found that the lower the proliferative activity of cells in the well, the higher the f-SatIII content [81]. The current study showed that the HSF-61 population is heterogeneous by f-SatIII content, but not by rDNA abundance.

This study generalizes rDNA CN data for 3264 individuals. The data were obtained for a decade using a modified NQH technique developed in our laboratory for the quantification of highly repetitive tandem repeats in human DNA samples of different origin and quality. Hori and colleagues [82] were the first to perform rDNA quantification in human DNA samples using a direct method of sequencing long DNA fragments (Oxford Nanopore Technology, Oxford, UK). The rDNA CN in a cohort of healthy controls varied from 250 to 700 (mean 430

The fact that cases carried more rDNA copies than any HC was most pronounced for CF monogenic disease (Fig. 2A). Increased rDNA CN in the DNA of patients with SZ was described for the first time by our group in 2003 on a small sample. Expansion of the SZ cohort from 42 patients [65] up to 179 [43], 956 [44], and 1489 (current study) did not change the result, as a significant fraction of patients with SZ harbor many (above the normal average) rDNA copies in the genome. This finding was recently corroborated by a Japanese team, who determined the relative rDNA content (with quantitative PCR) in the genomes of brain and blood cells of Asian patients with SZ [46].

In the case of a monogenic disease with a known pathogenesis that does not affect the process of protein translation, such as CF, any idea that predisposition is caused by an increased rDNA CN should be excluded. The rDNA CN cannot be causative for the pathogenesis. Thus, analyses of our data and the data of other groups suggest only one hypothesis: provided that a genetic pathology exists in the embryo genomes, embryos with a large rDNA CN have better chances of survival. We suggest that a very large rDNA CN (

In three groups with a wide age range and large number of DNA samples (CF, SZ, and НСs), we observed the same dynamics of rDNA CN changes with aging. The maximum variation of the parameter occurred in young/middle aged subgroups. For НС, this age was 3–72 years, whereas it was under 17 years old for the CF and SZ groups (Fig. 1). For the CF, SZ, and НС groups, we established a decrease in the range (from minimum to maximum) and coefficient of variation in the older subgroups. This effect was most pronounced in the НС group, apparently, due to the widest age range available (3–101 years). It was previously shown that the relative amount of active rDNA copies in lymphocytes change according to the same pattern as total rDNA CN, namely, in the oldest age group, the range and CV are decreased [86]. There are two possible explanations for this phenomena. (1) With aging, the cells undergo genomic rearrangements, which result in either loss or amplification of rDNA copies. Such events take place during carcinogenesis. Cancer cells in the tumor often differ from the ambient normal cells by altered rDNA CN [38, 48, 49, 50]. The rDNA CN alterations are observed in various brain areas of patients with dementia [41]. (2) Healthy subjects with low (

Studying replicative senescence of HSFs, we revealed that the genomes of cells during final passages lost only hypermethylated copies of rDNA, which comprise, according to our estimates, no more than 10% of human DNA samples [64]. These copies are transcriptionally inactive and their replication is complicated. The ionizing radiation-induced stress did not lead to changes in rDNA CN in cultured stem cells [87]. HSF cloning data (Fig. 3C) corroborated the same rDNA content in every cell of the cell pool. Quantification of rDNA in various areas of brain of a patient with SZ also showed the same content, whereas considerable changes in the contents of other tandem repeats (telomere and satellite III) were observed between the areas [44, 88]. The rDNA abundance did not differ in the cells of different organs of a SZ patient (Fig. 3B). Within the framework of the present study, we analyzed changes in rDNA CN in 311 DNA samples obtained from the same subjects, but at different times (Fig. 3A). A decrease in rDNA CN, which was beyond the experimental error, was observed in as few as four DNA samples (1%). Perhaps the time interval between blood sampling from the same subjects (12-year maximum) was not long enough. Further studies are warranted with longer time intervals.

We did not register rDNA amplification in any of the cases. rDNA CN decreases down to 500 in the long liver subgroup can be partially explained by hypermethylated copy loss during the subject’s lifetime (in approximately 10% of the genomes). However, the elimination of DNA samples with a low rDNA CN (

Thus, the study corroborated our previous data [90] that rDNA CN is a stable individual trait in ontogenesis.

We believe that within one human organism or one cell population, rDNA CN is a fairly stable genetic trait statistically associated with some diseases and overall life expectancy, which however, can change in rare cases under conditions of chronic oxidative stress. We believe that the observed age- and disease-related differences between the studied groups in mean rDNA CN and its variance are caused by biased elimination of carriers of marginal (predominantly, low) rDNA CN values. Further research is needed to better understand the relationships of rDNA with normal cellular physiology and phenotypic variation.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

NNV, EIK, LNP, GPK, RAZ and SVK designed the research study. NNV, ESE, YLM, SAK, TPV and NVZ formed the patient dataset. ESE conducted laboratory tests. NNV, ESE and SVK analyzed the data. NNV and LNP wrote the draft manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The investigation was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Studies on the SZ and HC groups were approved by the Independent Interdisciplinary Ethics Committee on Ethical Review for Clinical Studies (51 Leningradsky Prospekt, Moscow, 125468, Russia, 8 (915) 346-30-30); Protocol #4 dated March 15, 2019 for the scientific minimally interventional study ‘Molecular and neurophysiological markers of endogenous human psychoses’). The study design for the CF group was approved by the ethics committee of the Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution “Research Centre for Medical Genetics” (Protocol No. 6/4 dated 15.11.2016). The study design for the MCI group was approved by the Independent Interdisciplinary Ethics Committee on Ethical Review for Clinical Studies (Protocol #4 dated 15 March 2019). All participants or parents/legal guardians of participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study after the procedures had been completely explained.

We would like to express gratitude to Roman V. Veiko (RCMG) for the development of “Imager 6.0” software. We also thank all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation in the framework of State assignment FGFF-2022-0007.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.