1 Department of Geriatric Medicine, First Hospital of Lanzhou University, 730000 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

2 Gansu Provincial Clinical Medical Research Center for Geriatric Diseases, 730000 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

3 Department of Anesthesia and Surgery, First Hospital of Lanzhou University, 730000 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

4 The First Clinical Medical College of Lanzhou University, 730000 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a hereditary disease of the myocardium characterized by asymmetric hypertrophy (mainly the left ventricle) not caused by pressure or volume load. Most cases of HCM are caused by genetic mutations, particularly in the gene encoding cardiac myosin, such as MYH7, TNNT2, and MYBPC3. These mutations are usually inherited autosomal dominantly. Approximately 30–60% of HCM patients have a family history of similar cases among their immediate relatives. This underscores the significance of genetic factors in the development of HCM. Therefore, we summarized the gene mutation mechanisms associated with the onset of HCM and potential treatment directions. We aim to improve patient outcomes by increasing doctors’ awareness of genetic counseling, early diagnosis, and identification of asymptomatic patients. Additionally, we offer valuable insights for future research directions, as well as for early diagnosis and intervention.

Keywords

- cardiomyopathy

- hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- heredity

- genetic mutations

In 2008, European Society of Cardiology launched a classification method for cardiomyopathies, which not only focused on the pathological morphology and dysfunction of different phenotypes of cardiomyopathies, but also made detailed groupings according to whether they are hereditary or not [1]. In recent years, with the vigorous development and widespread application of new medical imaging and molecular biology technologies, people’s understanding of cardiomyopathy has greatly increased. On this basis, the new guidelines divide cardiomyopathy into hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM), non-dilated left ventricular cardiomyopathy (NDLVC) and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC). This new classification prompts clinicians to consider cardiomyopathy as the cause of several clinical manifestations (e.g., arrhythmias, heart failure) [2].

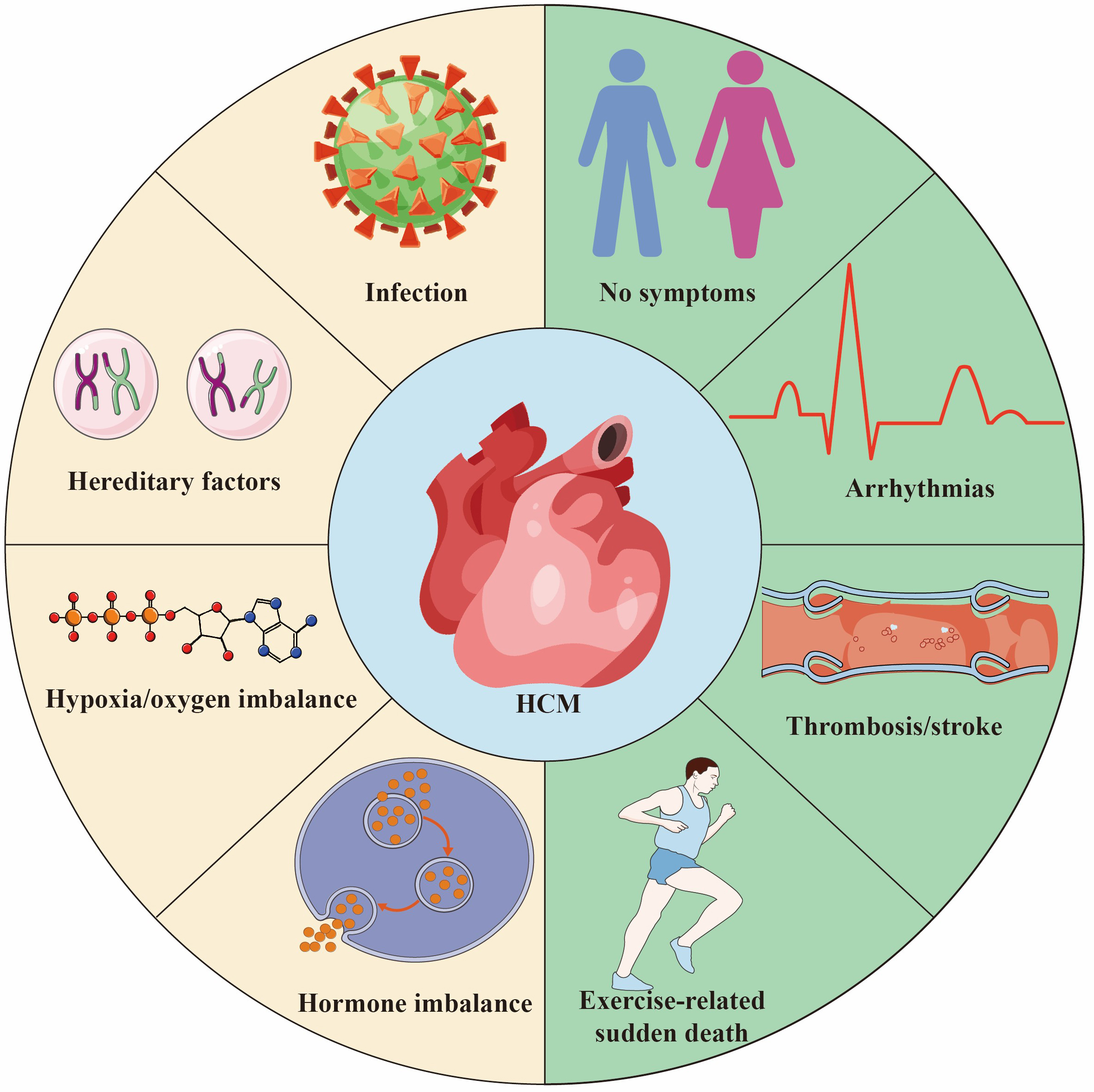

HCM is a potential hereditary heart disease characterized by abnormal thickening of the heart muscle, leading to abnormal heart function [3]. The pathogenic genes of HCM mainly involve genes encoding cardiac myofilament proteins, such as MYH7, MYBPC3, etc. These gene mutations lead to abnormal myocardial contractile function, increase the stress load of myofilaments, and ultimately cause myocardial cell hypertrophy, disordered arrangement and fibrosis, which in turn leads to the occurrence and development of HCM [4, 5]. The common causes and outcomes of HCM are shown in Fig. 1. In the early days, due to insufficient diagnostic technology and limited knowledge about HCM, the early prevalence was estimated to be 1/500 [6]. However, a recent study has shown that HCM may be more common than traditionally expected, affecting approximately 1 in 200 patients [7]. In comparison to the general population, individuals with HCM face significantly elevated risks across multiple fronts. Numerous studies have shown that patients with HCM face a significantly increased risk of adverse events compared with the general population. They have a higher risk of death, with twice the risk of sudden death, 2.5 times more likely to have heart failure, and approximately 6 times higher rates of atrial fibrillation than the age-matched general population [8, 9]. However, a large international cohort study of HCM patients with long-term follow-up found no difference in mortality, progressive heart failure, or sudden death events between those with and without pathogenic genotypes. This study suggests that genetic test results cannot reliably predict the prognosis of HCM patients or guide management decisions. Although their findings differ from most current research, the authors attribute this to demographic differences and variability in clinical outcomes across different eras [10]. Nowadays, with more and more research on its genetic characteristics and pathogenesis, it has attracted the attention of more and more cardiovascular physicians. Although most patients experience a clinically benign course, some develop complications, including heart failure, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden death. In addition, different genetic defects can also lead to different clinical phenotypes, such as asymmetric left ventricular hypertrophy [11]. Nevertheless, there is also evidence of nonfamilial forms of HCM, which also needs to be paid enough attention [12].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a common hereditary heart disease, 30%–60% of the causes are due to genetic factors. Other causes include infection/inflammation, hypoxia/oxygen supply imbalance and endocrine factors. The outcome of HCM varies depending on individual differences and the severity of the disease. Some people are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms throughout their lives and live a normal life. Some patients suffer from thrombosis/stroke secondary to atrial fibrillation. HCM is one of the main causes of sudden death in young athletes. Created by Adobe Illustrator (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

This review aims to explore the current genetic mechanism of HCM and the correlation between HCM genotype and phenotype. It also discusses new directions in molecular diagnosis, genetic counseling, and personalized treatment. It aims to guide clinical diagnosis and treatment, and the direction of future basic research.

HCM stands out as the predominant hereditary heart condition, typically passed down through generations in an autosomal dominant manner. It often exhibits incomplete penetrance and a degree of variability, with around 30%–60% of cases showing familial ties [10, 13]. Presently, there’s a prevailing agreement within the medical community to advocate for targeted genetic testing in individuals suspected of HCM [14]. This approach serves to not only confirm the diagnosis but also shed light on the specific molecular causes, facilitating informed decisions regarding family screening and treatment strategies [15]. We used the STRING 12.0 database (https://cn.string-db.org/) to screen genes closely related to HCM, and through in-depth analysis of relevant literature, selected genes with significant roles in HCM, while also focusing on genes that are relatively less studied but potentially important. We focused on genes that have a clear role in HCM and are likely to provide new insights.

The MYBPC3 encodes the cardiac isoform of myosin-binding protein C (cMBP-C). This gene spans a 3.7 kb DNA sequence and contains 34 coding elements, ultimately forming 35 exons. These exons are transcribed to produce a 3824 bp transcript. cMBP-C, a member of the intracellular immunoglobulin superfamily, is encoded by the MYBPC1 and MYBPC2 in skeletal muscle and by the MYBPC3 in the heart. Its structure includes eight immunoglobulin-like domains (C0, C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C8, C10) and three fibronectin type III domains (C6, C7, C9) [16, 17]. The core function of cMBP-C is to precisely regulate cross-bridge recycling in cardiomyocytes through phosphorylation and interaction with other factors, thereby contributing to the assembly of myocardial heavy chains. This regulation is crucial for ensuring that the heart muscle contracts and relaxes properly. Additionally, cMBP-C modulates the sensitivity of fibrin protein to calcium ions, which in turn affects the contractile performance of the myocardium. This discovery offers a new perspective for understanding the mechanisms underlying myocardial contraction [18].

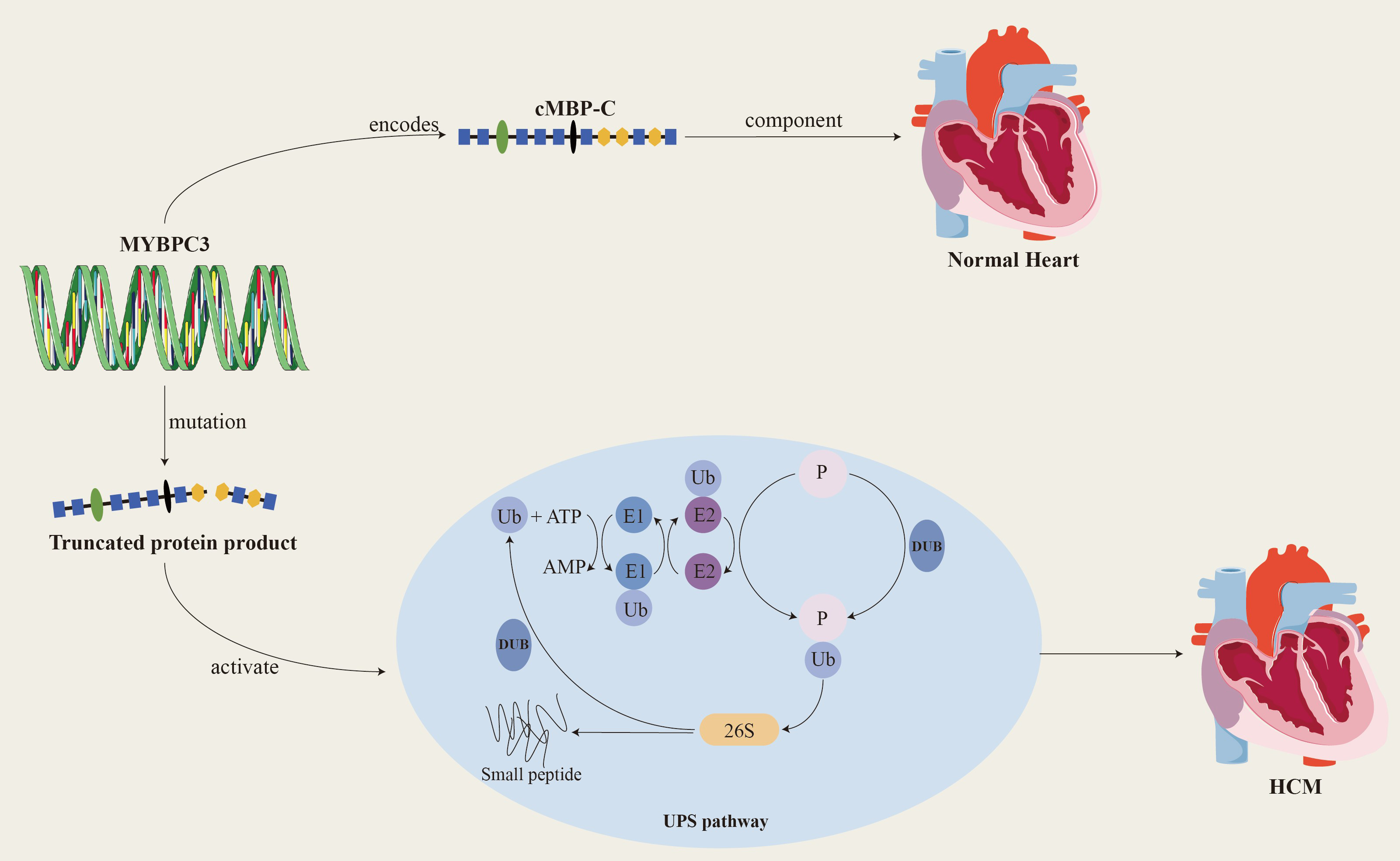

Since the MYBPC3 was recognized by the scientific community as the main causative gene of HCM in 1995, a large number of studies have focused on this gene and its related mutations. To date, more than 600 mutations related to the MYBPC3 have been discovered, and these mutations account for approximately 35% of mutation-positive HCM patients. This finding further solidifies MYBPC3’s status as a major causative gene in HCM [19, 20, 21]. Among the known MYBPC3 mutations, more than 60% are truncating mutations, including nonsense mutations, insertions or deletions, splicing or branch point mutations, and the MYBPC3 is tolerant to missense and LoF mutations (LOUEF: 0.96). Truncating mutations often activate nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) and the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), leading to haplodeficiency of the cMBP-C, the production of toxic peptides, and the COOH-terminal truncation of cMBP-C, which in turn causes myosotrophy (Fig. 2). The deletion of the protein or its binding site causes abnormalities in the structure and function of myosin, ultimately leading to haploid protein deficiency. Haploid gene defects are the predominant manifestation of heterozygous deletion mutations, and most MYBPC3-related HCM mutations are heterozygous [22, 23].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. MYBPC3 encodes cardiac myosin binding protein-C, which is a key structural protein of the myocardium and plays an important role in the relaxation and contraction of the myocardium. When MYBPC3 mutates, it produces a truncated protein product that activates the UPS system and ultimately leads to HCM. cMBP-C, cardiac myosin binding protein-C; Ub, ubiquitin; E1, ubiquitin-activating enzyme; E2, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme; DUB, deubiquitinating enzymes; UPS, ubiquitin-proteasome system; P, phosphonates. Created by Adobe Illustrator (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Clinical phenotypes caused by MYBPC3 mutations often share some common characteristics: disease onset usually occurs after middle age, cardiac hypertrophy is relatively low, and disease progression is slow. Clinically, truncating mutations and double mutations in the MYBPC3 often lead to more severe clinical phenotypes. In addition to changes in cMBP-C composition that can lead to myasthenia gravis and peptide toxicity, its function is also regulated by a variety of post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation, acetylation, citrullination, and oxidation. Compensatory slowing of calcium processing preserves contractile parameters, whereas faster sarcomere dynamics reduce myocardial contractility [24]. At present, at least three phosphorylation sites have been found to be located in the molecular structure of cMBP-C and targeted by protein kinases. These sites begin at Ser282, which acts as a switch to make Ser273 and Ser302 more susceptible to phosphorylation. Currently known protein kinases that can phosphorylate MBP-C include protein kinase A (PKA), Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II, p90 ribosomal S6 kinase, protein kinase D and protein kinase C, etc. [25]. Research shows that MYBPC3 therapy has the potential to restore MBP levels, with the goal of preventing heart failure and reducing mortality in MYBPC3-related cardiomyopathy. Each genetic mutation has its own unique clinical manifestations. For example, men with the MYBPC3 c.2149-1G

The MYH7 is located on chromosome 14q11.2-q13 and contains 40 exons. It encodes the

The severity of HCM is closely related to the proportion of abnormal myosin in cardiomyocytes. Mutations in the MYH7 may cause disease through a dominant-negative “toxic peptide” mechanism, that is, the abnormal myosin produced by the pathogenic mutation will interfere with the normal contractile function of the sarcomere. In addition, MYH7 gene mutations may also increase the sensitivity of myofibrillar cells to Ca2+, leading to increased myocardial energy consumption and ventricular diastolic dysfunction, further exacerbating ventricular hypertrophy [32]. The pathogenicity of MYH7 gene mutations is closely related to its key function in cardiomyocytes. These mutations not only affect the contractile function of cardiomyocytes but may also lead to changes in a complex genetic and epigenetic background. Therefore, an in-depth study of the pathogenic mechanism of MYH7 gene mutations is of great significance for early diagnosis, precise treatment and prognosis judgment of HCM patients. It is exciting to see that significant progress has been made in the current field of gene therapy research. In particular, the combined application of gene therapy or gene editing technology and human-induced pluripotent stemcell-derived cardiomyocyte (hiPSC-CM) has opened up a new way for individualized cultivation of mature cardiomyocytes. This breakthrough technology may bring unprecedented hope for the treatment of HCM patients caused by MYH7 gene mutations.

The traditional concept is that caveolae are a rich place for intracellular signaling molecules and can form complexes to regulate ion channels, vesicle transport and signal transduction. But modern molecular biology techniques have revealed more functions of caveolae, such as maintaining cholesterol homeostasis and regulating signaling [33]. However, the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis remains controversial. Caveolae is a key characteristic protein on the caveolae membrane, which is essential for maintaining the morphology, structure and function of caveolae. It also constitutes a special subset of lipid rafts [34]. As the main component of caveolae, caveolin-3 (CAV3) was first cloned and identified in 1996. It consists of 151 amino acids and contains several independent domains: N-terminal domain (residues 1–53), CSD domain (residue 54–73), transmembrane domain (residues 74–106) and c-terminal domain (residues 107–151) [35]. Most of its mutations are concentrated in the caveolin scaffolding domain, which is involved in self-assembly and interaction with signaling molecules. Therefore, CAV3 plays an important role in cell physiology, including regulating ion channels, vesicle transport, cholesterol and calcium homeostasis, and signal transduction. It serves as a molecular chaperone and scaffold through the scaffolding domain to regulate a variety of signaling molecules.

When the CAV3 mutates, it may lead to varying degrees of lesions in skeletal muscle, myocardium and other tissues through various mechanisms. This type of disease is collectively called caveolin disease. The caveolin-3 protein encoded by the CAV3 gene is a key component of caveolae. It is expressed in cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle and smooth muscle, and interacts with a variety of molecules related to cardiac hypertrophy signals [36]. In cardiomyocytes, a variety of signaling molecules such as

It is worth noting that the distribution of

The GLA is a gene in the human genome and is located on the X chromosome. The coding sequence of the GLA contains 7 exons and 6 introns, with a total length of approximately 13.5 kb. It includes the transcription start site, coding region, and termination site. This gene encodes a protein called

The mature

In cardiac cells, this deposition leads to organelle dysfunction, intracellular metabolism and energy production are affected, and ultimately leads to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia. Deposition of Gb3 leads to the formation of its metabolite lyso-Gb3 [41]. Lyso-Gb3 is a degradation product of Gb3 but also accumulates within cells. The deposition of Gb3 and lyso-Gb3 causes intracellular metabolic abnormalities and lysosomal dysfunction in cardiac cells, leading to hypertrophy, hyperplasia, and fibrosis of cardiac myocytes [42]. Gb3 and Lyso-Gb3 are deposited in various cells of the cardiovascular system, leading to various manifestations including left ventricular hypertrophy, conduction abnormalities, aortic valve and mitral valve insufficiency, etc. [43]. Gb3 is deposited in all types of cells and tissues in the heart, including cardiomyocytes, intramyocardial blood vessels (endothelial and smooth muscle cells), and conductive tissue. In addition to the mechanical effects of deposition, the accumulation of these substances can trigger secondary reactions, damaging cellular endocytosis and autophagy functions, inducing apoptosis, and disrupting mitochondrial energy production. This leads to abnormal energy metabolism and increased oxidative stress, which in turn triggers metabolic changes within cells. These alterations contribute to cellular remodeling and activate pathways that promote cellular hypertrophy. Accumulated Gb3 may also change the expression of ion channels and/or cell membrane transport, thereby changing the electrophysiological properties of cardiomyocytes, leading to an increase in myocardial conduction velocity between the atrium and ventricle, resulting in a shortened PR interval on the patient’s electrocardiogram [44]. Gb3 and Lyso-Gb3 can also serve as antigens to activate natural killer T cells, leading to chronic inflammation and autoimmune reactions, leading to pathological damage and fibrosis of cardiomyocytes, further promoting the occurrence of myocardial thickening, and ultimately leading to HCM.

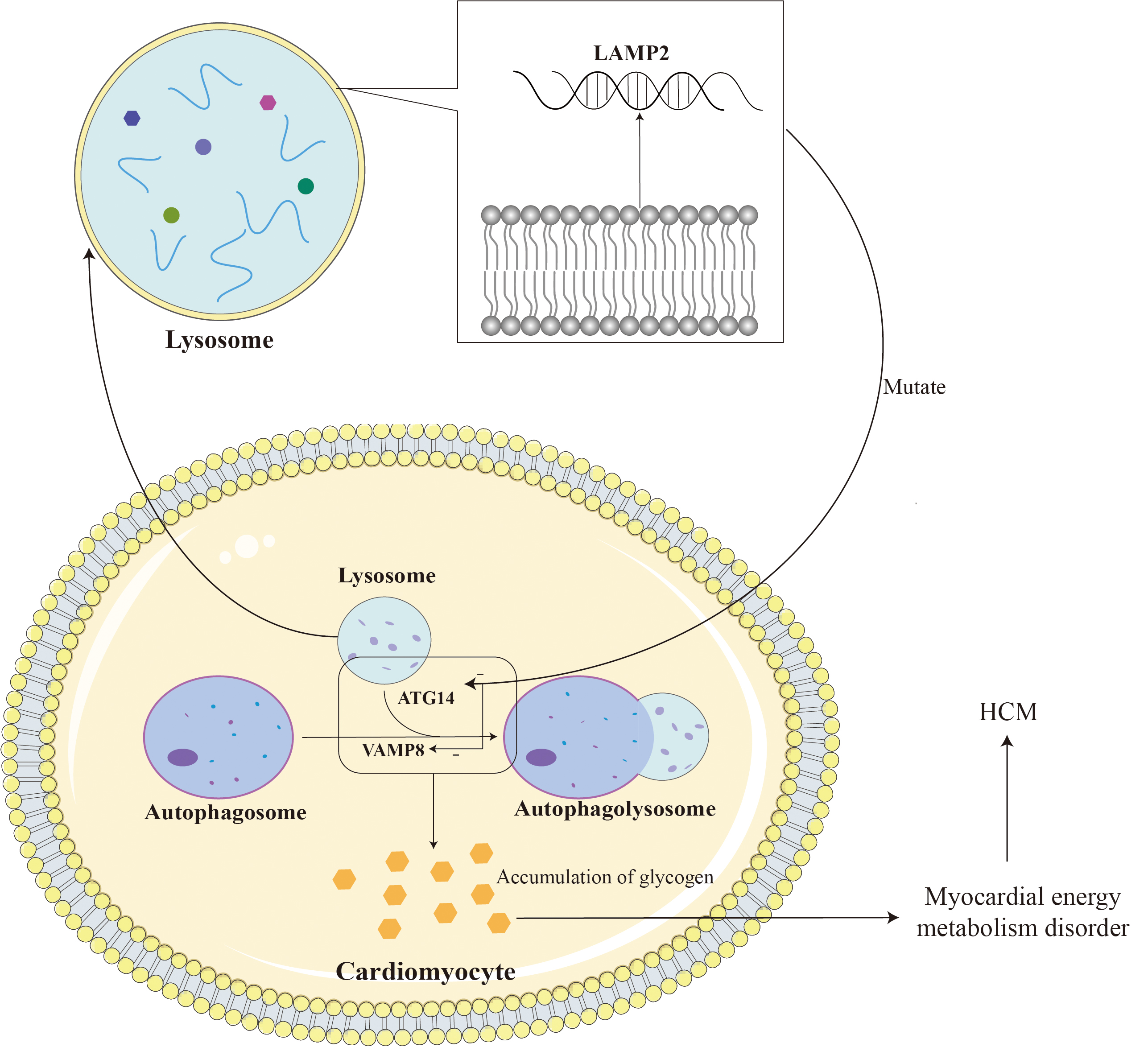

The LAMP2 is a gene encoding lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2). It is located on the X chromosome of the human genome and is also known as a Danon disease-related gene. LAMP2 is one of the main protein components of the lysosomal membrane. There are currently three main subtypes: LAMP2A, LAMP2B and LAMP2C [45]. Its structure includes extracellular domain, transmembrane domain and intracellular domain, which plays an important role in maintaining the structure and function of lysosome. LAMP2 forms a stable structure on the lysosomal membrane and helps maintain lysosome integrity and stability. It participates in regulating the formation, fusion and transport processes of lysosomes, ensuring the normal function of lysosomes within cells [46].

LAMP2 gene mutations can lead to defects in the autophagy function of autophagosomes, disorders in the fusion process of lysosomes and target cells, and loss of organelle motility, ultimately leading to the accumulation of autophagosomes in cardiomyocytes and the storage of glycogen in the cytoplasm [47]. LAMP2B is mainly involved in the biogenesis of lysosomes and macroautophagy, and is indispensable for the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes in cardiomyocytes [48]. LAMP2B is indispensable for autophagosome and lysosome fusion in cardiomyocytes. LAMP2B on the lysosomal membrane interacts with autophagy related gene 14 (ATG14) and vesicle-associated membrane protein 8 (VAMP8) through its C-terminal domain to mediate autophagosome-lysosome fusion, thereby regulating cardiomyocyte function [45]. ATG14 is an important factor in the autophagy process. It binds to the Beclin-1 complex (similar to the PI3K complex) and participates in the formation of autophagosomes and the regulation of the autophagy process. LAMP2B helps regulate the formation of autophagosomes and promotes the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes by binding to ATG14. VAMP8 is a vesicle-associated membrane protein that participates in the process of vesicle trafficking and fusion within cells. During the autophagy process, LAMP2B helps regulate the fusion process between autophagosomes and lysosomes through its interaction with VAMP8, promoting the degradation of the contents in autophagosomes by lysosomes. Loss of LAMP2B leads to autophagy-lysosomal maturation impairment. This dysfunction may cause the autophagic vacuoles within autophagosomes to be unable to effectively fuse with lysosomes, thereby affecting the degradation and clearance of autophagic contents [49]. Due to lysosomal dysfunction, glycogen in autophagosomes cannot be effectively degraded and cleared, resulting in the accumulation of glycogen. This accumulation of glycogen leads to metabolic disorders and energy imbalance within cardiomyocytes. Similarly, lysosomal dysfunction can also lead to the accumulation of other autophagic vacuoles in autophagosomes that cannot be effectively degraded and cleared. The accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and glycogen can lead to metabolic disorders within cardiomyocytes, including disorders of energy metabolism and disorders of waste clearance. This metabolic disorder can lead to intracellular functional abnormalities, including reduced calcium ion processing capabilities, abnormal cell signaling, etc., thereby affecting the structure and function of cardiomyocytes; triggering intracellular stress responses, including inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, etc. These stress reactions will cause the activation of intracellular biochemical pathways and promote the hypertrophy and proliferation of muscle cells; the accumulation of metabolites and waste products will increase the volume of cells and trigger a series of changes in cell signaling pathways, thereby promoting the hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes and hyperplasia. In addition, missing or dysfunctional LAMP2 can lead to obstruction of lysosomal autophagy, which in turn can lead to damage and death of cardiomyocytes, thereby causing fibrosis and granuloma formation during the repair process. These abnormal tissue repair and inflammatory responses may cause cardiac hypertrophy [49, 50, 51]. Fig. 3 shows some of the mechanisms by which LAMP2 mutations cause HCM.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. LAMP2 is located on the lysosomal membrane and assists in the fusion of lysosomes and autophagosomes. The mutation leads to impairment of myocardial autophagy by reducing the fusion of lysosomes and autophagosomes, leading to glycogen accumulation and ultimately HCM. LAMP2, lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2; ATG14, autophagy-related protein 14; VAMP8, vesicle-associated membrane protein 8. Adobe Illustrator (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

In addition, there is increasing recognition that other rare genetic disorders may mimic the phenotypic and clinical features of HCM but are caused by mutations in different genes. Notable among these conditions are Fabry disease (an X-linked a-galactosidase deficiency with glycosphingolipid deposition), PRKAG2 syndrome (caused by mutations in the regulatory subunit of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase), and LAMP2 deficiency (a lysosomal storage disorder, also known as Danon disease) [52, 53, 54, 55].

ACTC1 is responsible for encoding

Most cases of HCM are caused by mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins, with less than 3% of pathogenic variants found in the sarcomeric gene ACTC1 [58]. Currently, 12 different ACTC1 mutations have been found in HCM patients. ACTC1 mutations are divided into three categories according to the position of the amino acid changes in actin: ① mutations that only affect the motor binding site of the myosin molecule are called M-type mutations, ② mutations that only affect the tropomyosin binding site, called T-class mutations, and ③ mutations that affect both myosin and tropomyosin binding sites, are called MT-class mutations [59, 60] (Table 1).

| Gene | Alternative titles | Class | Variant |

| ACTC1 | ACTC, SMOOTH MUSCLE ACTIN, ACTIN, ALPHA | Myosin/M | E99K |

| H88Y | |||

| R95C | |||

| F90Δ | |||

| S271F | |||

| Tropomyosin/T | A230V | ||

| R312C | |||

| Myosin and tropomyosin/MT | P164 | ||

| Y166C | |||

| A295S | |||

| A331P | |||

| M305L |

Symptoms in patients with HCM often include systolic dysfunction and restricted diastole, this may be because mutations in the ACTC1 associated with HCM alter the structure and function of cardiac actin, thereby affecting myocardial function [61]. A study has found that a non-synonymous mutation (p.Gly247Asp or:G247D) in the ACTC1 leads to increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis and sarcomeric disorganization, both of which have deleterious effects on contractile function [62]. Studies have found that sarcomeric protein mutations cause intrinsic abnormalities in myofibrillar structure and function. These abnormalities jointly drive invasive structures at the cellular and extracellular levels by interfering with the excitation-contraction coupling process, cardiomyocyte energy metabolism, cardiomyocyte signaling, and other mechanisms. Remodeling, which in turn impairs myocardial systolic and diastolic function, leads to the common occurrence of progressive left ventricular dysfunction in HCM [63, 64]. The specific mechanism by which ACTC1 mutations cause HCM remains unclear. ACTC1 mutations lead to increased myocardial cell apoptosis and abnormal sarcomeres, resulting in abnormal myocardial systolic and diastolic function, which in turn leads to abnormal cardiac morphology and hemodynamic disorders. This may be a potential mechanism for continued research.

TNNT2 is located on chromosome 1 (1q32), encoding cardiac troponin T2 (TnT). It mainly regulates actin filament function by binding calcium ions and is crucial for human cardiac muscle contraction and relaxation [65]. TnT interacts with the other two troponin subunits, troponin T (TnT) and troponin C (TnC), through the C-terminus to form a stable trimer core, and the N-terminus interacts with actin filaments. Binding at specific sites anchors the troponin complex to the myofilaments and moves as the muscle contracts and relaxes. 2%–5% of HCM patients are caused by pathogenic mutations in this gene, and abnormal N-terminal splicing and TnT point mutations are possible causes. Abnormal splicing of N-terminal exon 5 can affect the interaction between cTnT and tropomyosin, interfere with the calcium sensitivity of myofibrils, thereby affecting cardiac contraction, ultimately leading to cardiac hypertrophy and HCM [66, 67]. More than ten TNNT2 single mutations causing HCM have been found, such as Ile79Asn, Glu244Asp, etc., but the specific mechanism is still not completely clear. Homozygous mutations are very rare and usually have a more severe phenotype than heterozygous mutations in a gene dose-dependent manner [68, 69]. A homozygous mutation K280N (c.804G

| Mutation type | Mechanism |

| K280N | Affects sarcomere dynamics and energetics, leading to impairment of myocardial contractile function [71, 72]. |

| Ile79Asn, Arg92Gln, Glu244Asp, Lys273Glu, Arg278Cys | Maintaining calcium sensitivity of cardiac myofilament proteins under conditions of higher Ca2+ [73, 74, 75, 76]. |

| Lys210del, Arg141Trp | Causes sarcomeric protein mutations and desensitization to Ca2+ [77, 78]. |

| E244D, K247R, D270N, N271I, K273E | Weaken the affinity of troponin to thin filaments, cause abnormal protein folding, destroy the stability of troponin complex, enhance calcium ion sensitivity, and enhance the maximum activity level of ATPase [79, 80]. |

A study has shown that by replacing mutated TnT with wild-type TnT, the rate constants of tension and isometric relaxation generated after maximum Ca2+ activation can be reduced, reducing the tension cost to unmutated control values, suggesting that the direct effect of the mutant protein can be reversed. Therefore, the introduction of normal protein remission may be a potential therapeutic strategy to treat this type of HCM patients [70]. Table 3 summarizes all the gene types, functions and phenotypic characteristics mentioned above.

| Gene type | Gene function | HCM phenotype |

| MYBPC3 | Encodes cMBP-C, which is involved in myofilament assembly and stability, regulation of cardiac contraction and calcium sensitivity. | Myocardial hypertrophy (left ventricle, especially the ventricular septum), arrhythmias, cardiac dysfunction, and decreased exercise tolerance. |

| MYH7 | Encodes | Myocardial hypertrophy (thickening of the left ventricular wall), arrhythmias, heart failure, and familial clustering. |

| LAMP2 | Encodes LAMP2, which is involved in the maintenance of lysosomal function, regulation of autophagy and cell protection. | Myocardial hypertrophy (left ventricular hypertrophy), arrhythmias, premature heart failure, systemic symptoms such as skeletal muscle weakness, liver enlargement and mental retardation, etc., the prognosis is poor. |

| TNNT2 | Encodes cTnT, which is involved in calcium regulation of myocardial contraction, transmission of contractile signals and maintenance of myofilament structure. | Myocardial hypertrophy (thickening of the left ventricular wall, which may be present), left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, arrhythmias, heart failure, and a distinct genetic trait. |

| ACTC1 | Encodes | Myocardial hypertrophy (asymmetric hypertrophy), arrhythmias, heart failure, exercise intolerance, and familial clustering. |

| CAV3 | Encodes Caveolin-3, which is involved in membrane structure regulation and signal transduction, maintaining muscle cell stability and regulating ion channel function. | Myocardial hypertrophy (symmetric or asymmetric thickening of the left ventricle), arrhythmias, decreased exercise tolerance, heart failure, and familial hereditary. |

| GLA | Encodes | Myocardial hypertrophy (left ventricle), arrhythmia, heart failure, decreased exercise tolerance, and other systemic symptoms such as rash, renal impairment, and neuropathy. |

Genetic counseling is a process designed to help individuals and their families understand and cope with the pathophysiological, psychosocial, and familial implications of genetic disorders [81, 82]. It should be performed by health care professionals with specific training, such as clinical/medical geneticists. Genetic counseling includes but is not limited to discussing genetic risks, providing education and clinical assessment, conducting pre- and post-test counseling, identifying variants to be tested, obtaining a three-generation family history, and providing psychosocial support [83, 84]. In general, genetic counseling can improve patients and relatives’ understanding of the disease, increase decision satisfaction and reduce anxiety [85].

The new guidelines provide more scientific conclusions on the importance of genetic counseling [2]. For genetic counseling of children, the first consideration should be whether they have the ability to independently decide to undergo genetic testing and the issue of informed consent. Obtain family history after fully considering the wishes of the child and his or her family. It should be noted that symptoms of HCM may not become apparent until many years later. It is also necessary to consider the impact this may have on the child’s subsequent education, sports activities, etc., and consider the transition from pediatric to adult medical care [86, 87]. The latest guidelines in 2024 indicate that for children with HCM, regardless of symptom status, exercise stress testing is recommended to determine functional capacity and provide prognostic information. Exercise stress testing is particularly useful for evaluating overall exercise tolerance and identifying potential exercise-induced left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. This is especially important in young patients, as children might not be able to clearly articulate their symptoms, making routine exercise stress testing a key diagnostic tool in this population. It is also recommended that for most HCM patients, there is no need to generally restrict strenuous physical activity or competitive sports [13]. The guiding principle remains that any clinical or genetic testing should be conducted in the best interest of the child. Psychosocial outcomes for children who undergo clinical screening and cascade genetic testing do not differ from those in the general population [88]. Genetic counseling and testing are available for at-risk pregnant women or for fathers with a known pathogenic (familial) variant. Chorionic villus sampling is performed transcervically or transabdominally at 10 to 14 weeks of gestation. The rate of fetal loss associated with the procedure is 0.2%. The fetal loss rate is 0.1% when amniotic fluid is collected directly after 15 weeks of pregnancy [89]. The current non-invasive testing method is mainly to isolate cell-free foetal DNA from maternal plasma samples in early pregnancy (around the 9th week), and the risk of miscarriage will not increase. However, it is still under development and not widely used [90]. For the general population, the guidelines recommend that after investigating disease-related genes associated with a specific phenotype, if a pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variant is found in the index patient, cascade genetic testing, including pre-test genetic counseling, should be offered to first-degree at-risk relatives. In the event of the death of a first-degree relative, evaluation of the deceased’s next of kin (i.e., the index patient’s second-degree relatives) should also be considered [91, 92].

Shared decision-making is crucial for delivering the best possible clinical care. It requires a careful conversation between patients, their families, and healthcare teams, where medical professionals outline all available testing and treatment options, explain the associated risks and benefits, and assess the suitability of each option for the patient. This process also ensures that patients communicate their personal preferences and goals, allowing these to guide and inform their treatment plan [13]. The goals of treatment for HCM are to improve symptoms, reduce complications, and prevent sudden death. There is no strict staging of HCM, and there is no specific treatment for non-obstructive HCM. For obstructive HCM, beta-blockers or surgery are required. As people’s understanding of the hereditary nature of HCM becomes better, screening and monitoring of family members is becoming more and more important [93].

MYH7 mutations will affect the activity of myosin ATPase and increase myocardial force production, while MYBPC plays a role in sarcomere organization and may act as a brake on the contraction of myofibrils [94, 95]. Mavacamten (MyoKardia, Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA), an oral small molecule allosteric modulator of cardiac

Sarcomeric mutations in HCM lead to inefficient utilization of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which may lead to energy depletion and impair myocardial energy metabolism when cardiomyocytes face excessive energy demands [99]. Under this condition, fatty acid utilization increases as a compensatory mechanism, similar to the adaptations of cardiomyocytes during ischemia [100]. Perhexiline, used as an anti-angina treatment in Australia and New Zealand, is an oral carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT-1) inhibitor. Inhibiting CPT-1 reduces mitochondrial uptake of fatty acids [101]. Although there are clinical studies showing beneficial changes in cardiometabolism and improved exercise capacity in the experimental group compared with placebo [102, 103], a recent multicenter phase IIb clinical trial (NCT02862600) was terminated due to lack of efficacy and a higher incidence of side effects. Trimetazidine is also a metabolic regulator that can produce reversible inhibition of 3-ketoacyl-coenzyme A. It can be used as a second-line antianginal drug in Europe with fewer side effects, but it has recently been proven to be ineffective in non-hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (NCT01696370) [104].

In recent years, studies of mitochondrial-targeted therapies in HCM have shown that improving the supply of equivalents in the Krebs cycle with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide supplementation or using elamipretide (a cardiolipin peroxidase inhibitor and mitochondrial targeting peptide) improves respiratory chain function to stabilize cardiolipin in the inner mitochondrial membrane, improves the proximity of the mitochondrial respiratory system, reduces electron leakage and oxidative stress, and enhances ATP regeneration [105, 106, 107].

HCM is primarily caused by mutations in genes encoding myocardial proteins. The most commonly mutated genes include MYH7 and MYBPC3. Other related genes are LAMP2, TNNT2, and ACTC1 [108]. Genetic counseling can help family members understand their risk for HCM. Through genetic testing, it can be determined which family members carry these mutated genes, enabling early preventive measures to improve their quality of life. Additionally, understanding the genetic basis of HCM allows doctors to develop individualized treatment plans. For families planning to have children, genetic counseling can provide advice on risks and options to reduce the likelihood of passing the condition to the next generation. Currently, due to the lack of relevant randomized controlled trials, drug treatment is primarily based on clinical experience to improve functional ability and reduce symptoms [109, 110, 111]. For patients with symptomatic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, the goal is to improve symptoms through septal ablation using medications, surgery, or alcohol. Treatment of symptomatic patients without left ventricular outflow tract obstruction focuses on management of arrhythmias, lowering left ventricular diastolic pressure, and treating angina. Patients with progressive left ventricular systolic or diastolic dysfunction who do not respond to medical therapy should be considered for cardiac transplantation early.

JLC, YX, JS, YML, ZKL, LZ, and JGY were responsible for the conception, design, and literature analysis. JLC and YX were responsible for most of the manuscript content writing. JS and YML are responsible for writing part of the manuscript content. ZKL and LZ were responsible for the production of charts and data collection. JGY is responsible for reviewing the content and proposing modifications. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by the Key Research and Development Programme of Gansu Province (No. 20YF8FA079).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.