1 Imperial College Ophthalmic Research Group (ICORG) Unit, Imperial College, NW15QH London, UK

2 Department of Neurosciences, Reproductive Sciences and Dentistry, University of Naples Federico II, 80131 Napoli, Italy

3 Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Enna “Kore”, Piazza dell’Università, 94100 Enna, Italy

4 Mediterranean Foundation “G.B. Morgagni”, 95125 Catania, Italy

5 Department of Optometry, University of Benin, 300238 Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria

6 Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital of Udine, 33100 Udine, Italy

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

The term inherited retinal dystrophies (IRDs) refers to a diverse range of conditions characterized by retinal dysfunction, and mostly deterioration, leading to a gradual decay of the visual function and eventually to total vision loss. IRDs have a global impact on about 1 in every 3000 to 4000 individuals. However, the prevalence statistics might differ significantly depending on the exact type of dystrophy and the demographic being examined. The cellular pathophysiology and genetic foundation of IRDs have been extensively studied, however, knowledge regarding associated refractive errors remain limited. This review aims to clarify the cellular and molecular processes that underlie refractive errors in IRDs. We did a thorough search of the current literature (Pubmed, accession Feb 2024), selecting works describing phenotypic differences among genes-related to IRDs, particularly in relation to refractive errors. First, we summarize the wide range of IRDs and their genetic causes, describing the genes and biological pathways connected to the etiology of the disease. We then explore the complex relationship between refractive errors and retinal dysfunction, including how the impairment of the vision-related mechanisms in the retina can affect ocular biometry and optical characteristics. New data about the involvement of aberrant signaling pathways, photoreceptor degeneration, and dysfunctional retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in the development of refractive errors in IRDs have been examined. We also discuss the therapeutic implications of refractive defects in individuals with IRD, including possible approaches to treating visual impairments. In addition, we address the value of using cutting-edge imaging methods and animal models to examine refractive errors linked to IRDs and suggest future lines of inquiry for identifying new targets for treatment. In summary, this study presents an integrated understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying refractive errors in IRDs. It illuminates the intricacies of ocular phenotypes in these conditions and offers a tool for understanding mechanisms underlying isolated refractive errors, besides the IRD-related forms.

Keywords

- myopia

- hyperopia

- eye development

- genotype-phenotype correlation

- neurotransmitter signaling

- axial length modulation

Refractive errors (hyperopia and myopia) are important causes of visual impairment across the globe [1], and particularly myopia prevalence is steadily increasing, due to a combination of genetic factors and lifestyle, with an estimated prevalence in 2050 of 49.8% of the world population [2].

Inherited Retinal Dystrophies (IRDs) are a diverse set of hereditary illnesses that involve the gradual deterioration of the retina, often resulting in significant visual impairment. Although IRDs and refractive errors have different pathogenesis and genetic origins, a considerable proportion of IRD patients also experience refractive errors, including as myopia or hyperopia [3]. This frequent co-occurrence raises important inquiries regarding the underlying causes for this overlap and implies that shared molecular pathways may be implicated in both illnesses. The correlation between IRDs and refractive errors is not coincidental, but rather indicative of common biological systems that regulate both retinal health and ocular growth. Genes that are responsible for retinal signaling, eye morphogenesis, and extracellular matrix organization are not only important for the development of retinal dystrophies, but also have significant influence on defining axial length and refractive outcomes. By prioritizing these common routes, we can acquire more profound understanding of how changes in retinal function impact ocular structure, resulting in refractive errors [4].

Comprehending the shared mechanisms that cause inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) and refractive errors is not only academically important but also has practical implications. Studying these pathways can improve our understanding of myopia, a disorder that has become widespread worldwide. The knowledge acquired from the research of IRDs has the potential to be applied in order to improve the management methods for myopia. This is especially true in the identification of early biomarkers for risk and the development of specific therapeutic approaches.

Hence, the objective of this study is to investigate the molecular interactions between inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) and refractive defects, with a specific focus on the significance of these discoveries for wider clinical use. By focusing our inquiry on the main objective of comprehending the development of refractive errors, specifically in relation to myopia, we want to enhance the effectiveness of preventative and treatment approaches for these prevalent visual impairments.

IRDs are a heterogeneous group of genetic conditions characterized by progressive degeneration of the retina, which tend to lead to varying degrees of visual impairment and eventually to total vision loss. These conditions are primarily caused by gene mutations, disrupting the normal function and maintenance of the choroid-retinal pigment epithelium-photoreceptors complex. IRDs include a variety of disorders such as rod-cone dystrophies/retinitis pigmentosa (RCD/RP), cone-rod dystrophies (CRD), Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), and macular dystrophies, each with distinct clinical features and genetic profiles [5].

The epidemiology of IRDs is complex due to their genetic heterogeneity and variable prevalence across different populations. In general terms, IRDs affect approximately 1 in 3000 to 4000 individuals globally, although specific prevalence rates can vary widely based on the type of dystrophy and the cohort of patients considered. For example, retinitis pigmentosa is relatively more common, while conditions like LCA and CRDs are rarer [6]. The incidence of IRDs is influenced by factors such as genetic background and consanguinity rates within populations, with certain genetic variants being more prevalent in specific regions or ethnic groups. Understanding the epidemiology of IRDs is crucial for developing effective screening, diagnostic, and therapeutic strategies tailored to diverse populations [7].

Phenotipic classification of IRDs can vary in different scientific settings, as it can be based on several criteria, including the clinical presentation, the main type of photoreceptor cells affected, the electrophysiologic features or the pattern of inheritance. Traditionally some forms are defined with the name of the original describer, but the substantial advances in the molecular characterization, are leading to a more gene-related definition. The combination of a uniquely high genetic, phenotypic and allelic variability [8, 9], makes the classification particularly complex, but still fundamental for proper diagnosis, patient management, and the possible use of personalized target therapies [10, 11]. IRDs can present as isolated conditions or in conjunction with impairments in other organs, as part of a syndromic spectrum.

Electrodiagnostic testing (EDT), coupled with the patient’s reported symptoms and the clinical presentation, are usually the key for a precise definition of the primarily affected photoreceptor cells forms [18].

The spectrum of syndromic conditions that include a form of IRD is extremely wide. Most prevalent syndromic forms are:

All patterns of inheritance can be identified in IRDs, autosomal recessive (AR), autosomal dominant (AD), X-linked (XL), digenic and mitochondrial [22]. The precise definition of a pedigree is crucial for the correct phenotype-genotype correlation that necessarily follows the results of molecular genetic testing. A deep phenotyping of patient’s family members is always recommended, beyond the self-reporting status [7].

IRDs are a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders, with over 280 genes implicated in their pathogenesis [8, 9]. These genes are responsible for various cellular processes crucial for the survival and proper function of retinal cells, including phototransduction, ciliary function, the visual cycle, and cellular metabolism [5]. The prevalence of different genes underlying IRDs can have wide margins of variation among different populations. This is particularly evident in populations with high consanguinity levels, where genes otherwise relatively rare, can be significantly prevalent [23].

Pathogenic gene variants causing dysfunctions in phototransduction and in the visual cycle are common causes of IRDs. Phototransduction is the biochemical process where photoreceptor cells convert light into electrical signals. Key genes in this pathway include RHO which encodes rhodopsin, and PDE6B, which encodes a subunit of phosphodiesterase [22]. Rhodopsin (RHO) (OMIM #180380) is the mostly involved gene in autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa, but can also be related to CSNB and retinitis punctata albescens and has also been described as pathogenic with a recessive mode of transmission [9].

The visual cycle involves the regeneration of visual pigments essential for photoreceptor function. Mutations in the RPE65 gene, which is crucial for all-trans-retinyl ester to 11-cis-retinal conversion, cause conditions like LCA or severe early-onset retinal dystrophies (SEORDs) [15, 22].

The proper functioning of cilia, which are hair-like structures on the surface of photoreceptor cells, is vital for their survival and function. Genes such as CEP290 and USH2A are involved in ciliary function, and their mutations can cause several IRDs, which include RP, LCA, and Usher syndrome. Ciliopathies are a significant subgroup of IRDs, characterized by defects in ciliary proteins leading to photoreceptor degeneration [24]. USH2A gene (OMIM #608400) encodes Usherin, a transmembrane protein expressed in various tissues including the retina and the inner ear, with a crucial role in photoreceptor survival and cochlear development. It is inherited in a recessive manner, and is the gene that is most frequently related to both autosomal recessive RP and Usher syndrome [9].

Pathogenic variants in genes responsible for the structural integrity and metabolism of photoreceptors also contribute to IRDs. For instance, variants in the ABCA4 gene (OMIM #601691) that is involved in the transport of retinaldehyde, cause Stargardt disease [9]. ABCA4 is critical for the removal of toxic byproducts of the visual cycle from photoreceptor cells [25]. ABCA4 has a recessive mode of transmission, with a spectrum of possible phenotypes generated by the combination of variants of different pathogenicity. It is characterized by a particularly high prevalence of carrier individuals that underlies the significant prevalence of ABCA4-related IRDs [26].

Advancements in next-generation sequencing (NGS) have significantly enhanced the diagnosis of genetic mutations associated with IRDs. NGS technologies, such as whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and whole-exome sequencing (WES), have enhanced the diagnostic yield by enabling comprehensive screening of known and novel IRD genes [27, 28, 29]. Particularly WGS is a precious tool for the identification of novel genes, such as the recently related to IRDs UBAP1L [30, 31].

The clinical manifestation of inherited retinal dystrophies (IRDs) can vary significantly among individuals, even those sharing a common pedigree, therefore with identical primary genetic variants. This variability is often due to the influence of phenotype modifiers, secondary factors that can modulate the severity, progression, and specific characteristics of the disease.

Non-genetic factors such as diet, exposure to light, and overall health can modify the phenotype of IRDs. Protective measures, such as wearing sunglasses to reduce light exposure and managing oxidative stress through diet and lifestyle, can influence disease progression and severity. These environmental factors can interact with genetic predispositions to modulate the clinical presentation of IRDs [28].

Modifier genes are distinct from the primary causative genes and can influence the disease phenotype. For example, in retinitis pigmentosa (RP), variations in the retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR-IP1L) gene have been shown to modify the severity of retinal degeneration in patients with mutations in the RPGR gene. Similarly, allelic variations in CERKL have been implicated in modulating disease progression in RP [32, 33].

Interactions between different genes can significantly influence the phenotype of IRDs. For instance, the presence of additional gene mutations involved in the same biological pathway can exacerbate or ameliorate the disease phenotype. In Usher syndrome, which involves both retinal degeneration and hearing loss, interactions between PDZD7 and other ciliary genes can modify the severity of the symptoms [34]. In the same way, additional variants in Bardet-Biedl Syndrome, can modulate the phenotypic expression [24].

The genetic background of an individual, including ethnic-specific variations, can serve as a phenotype modifier. Certain populations may carry specific genetic variants that can either mitigate or worsen the effects of primary IRD-causing mutations. For example, studies have shown that the frequency and impact of modifier alleles can vary significantly among different ethnic groups, affecting the clinical outcome of diseases like Stargardt disease and retinitis pigmentosa [27, 35].

Epigenetic modifications, like histone modifications and DNA methylation, can also act as phenotype modifiers in IRDs. These changes can modify the gene expression without variations in the DNA sequence, potentially affecting the severity and onset of retinal diseases. Studies have shown that environmental factors, like light exposure and oxidative stress, can induce epigenetic changes that impact disease severity and progression in IRDs [35, 36].

Understanding the role of phenotype modifiers in IRDs is crucial for developing personalized treatment strategies. By identifying and studying these modifiers, researchers can better predict disease outcomes and tailor interventions to individual patients, potentially improving their quality of life and clinical prognosis.

The therapy for inherited retinal dystrophies (IRDs) has seen significant advancements in recent years, driven by a deeper knowledge of the genetic and molecular mechanisms responsible for these disorders. Current therapeutic strategies include gene therapy, pharmacological interventions, cell-based therapies, and innovative technologies such as optogenetics and retinal implants [37].

Gene therapy aims to correct or compensate for the defective genes causing IRDs. One of the most notable successes in this field is the approval of voretigene neparvovec (Luxturna), which is a gene therapy considered for patients with RPE65-related IRDs, such as severe early onset retinal dystrophies (SEORD), certain forms of Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), and retinitis pigmentosa [38]. This therapeutic strategy provides a functional copy of the RPE65 gene that is transported into the cells of the retina via an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector, resulting in improved vision and slowing disease progression.

Stem cell therapy shows promising options for replacing damaged or lost retinal cells. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) can differentiate into retinal cells and be transplanted into the retina to restore vision. Clinical trials are currently underway to evaluate the efficacy and safety of these treatment options in ophthalmological disorders like retinitis pigmentosa and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [37].

Optogenetics is based on the use of light-sensitive proteins to restore light sensitivity to retinal cells that have lost their photoreceptors. By introducing genes encoding these proteins into ganglion cells of the retina or other surviving retinal cells, it is possible to bypass damaged photoreceptors and partially restore vision. This approach is still in the experimental stages but has shown promise in preclinical studies [39].

Retinal implants, also known as bionic eyes, are electronic devices designed to restore vision by directly stimulating the retinal neurons. The Argus II retinal prosthesis is an example of such an implant, which has been approved for use in patients with severe retinitis pigmentosa. These devices can provide functional vision, enabling patients to perceive light and shapes, and improve their quality of life [40].

The advent of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) technology has opened new avenues for the precise correction of genetic mutations causing IRDs. This gene-editing tool can be used to directly repair or knock out defective genes in retinal cells. Although still in the early stages of development, CRISPR-based therapies have shown potential in preclinical models and hold promise for future clinical applications [37].

In addition to these high-tech approaches, nutritional and lifestyle interventions can also play a role in managing IRDs. Diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and other nutrients that enhance retinal health may help slow disease progression and protect retinal cells from oxidative stress [33].

In order to have a clear vision, images in the space need to focus on the retina. Such focusing depends on a balance between the refractive power of the optical media, mainly the lens and the cornea, and the axial length of the eye. Refractive errors happen when such balance is defective, determinating a defocus of images on the retina and essentially are myopia, hyperopia and astigmatism. Myopia and hyperopia are considered in this review, in relation to their association with specific genes causing IRDs.

Myopia, commonly referred to as short-sightedness or near-sightedness, is an ocular disorder where pictures are focused in front of the retina rather than on it. This results in blurry vision while attempting to view objects at a distance [41].

Regarding its nature, it can be categorized into three groups: mild myopia (0 to –1.5 D), moderate myopia (–1.5 to –6 D), and high myopia (more than –6 D). In addition to the option of correcting refraction with spectacles or contact lenses, individuals with extreme myopia have a heightened susceptibility to sight-threatening disorders such as retinal detachment, macular degeneration, and glaucoma [42]. Hyperopia is the opposite defect, where the axial length of the eye is smaller, and images focus behind the retina. At birth the majority of babies are hyperopic, and physiologically, the eye progressively grows towards the optimal size in a process called “emmetropization”. High hyperopia is characterised by a cycloplegic sphere refraction

A study performed in 2013 by Bourne et al. [44], estimated that in 2010, the uncorrected refractive error was responsible of 20.9% of blindness Worldwide, and 36% in South Asia and 52.9% of moderate to severe visual impairment Wordwide reaching 65.4% in South Asia.

The development of myopia is influenced by an intricate interaction of genetic and environmental variables [45]. Multiple research conducted over the years have shown evidence for a genetic factor in the development of myopia. This is demonstrated by the higher occurrence of myopia in persons with a family history of the condition, especially among offspring of myopic parents and those with affected near relatives [46, 47]. Furthermore, research has demonstrated a stronger association between the development of myopia in identical twins compared to non-identical twins, providing additional evidence for the genetic underpinnings of this condition [48, 49].

Genetic linkage studies have identified 28 loci connected to myopia (MYP1-MYP28), mostly showing autosomal dominant inheritance [8, 19]. However, successful replication of findings from linkage analyses has been rare [50]. Based on their known biological functions, researchers have studied many candidate genes for their potential roles in myopia development. These genes are fundamental in various processes, such as ocular growth regulation and extracellular matrix composition [51, 52, 53, 54], but, although having shown potential in candidate gene studies, many have lacked validation from subsequent research. Notably, the PAX6 gene, which is a fundamental regulator of eye development, has been linked to both high and extreme and myopia in a meta-analysis that combined data from several candidate gene studies. This suggests that this gene may be involved in the development of myopia [55].

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been employed to overcome the limitations of candidate gene studies. GWAS have revolutionized our knowledge of the genetic architecture of complex traits like myopia. This approach does not rely on prior hypotheses about the genes involved, making it a powerful tool for discovering new genetic factors [56]. These studies involve scanning the entire genome for single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that occur more frequently in individuals with a specific trait compared to those without [57, 58, 59].

By analyzing genetic variants across the entire genome, GWAS have identified numerous loci linked with myopia across diverse populations, advancing the understanding of myopia genetics. The 23andMe and Consortium for Refractive Error and Myopia (CREAM) studies have both made significant contributions.

The CREAM consortium performed comprehensive genome-wide meta-analyses on a sample of 37,382 individuals of European and Asian ancestry. This investigation revealed the presence of eight previously unknown loci that are linked to refractive error. The loci encompass genes associated with neurotransmission (GRIA4), ion channels (KCNQ5), retinoic acid metabolism (RDH5), extracellular matrix remodeling (LAMA2, BMP2), and eye formation (SIX6, PRSS56). The findings also confirmed earlier connections with genes such as GJD2 and RASGRF1 [57].

23andMe, a leading direct-to-consumer genetic testing company, has provided substantial data through its extensive customer base. Their research revealed associations with myopia and the PRSS56 gene, associated with small eye size, the LAMA2 gene, a component of the extracellular matrix, and genes involved in 11-cis-retinal regeneration (RGR and RDH5). Additionally, they identified associations with genes involved in retinal ganglion cell growth and guidance (ZIC2, SFRP1) and genes implicated in neuronal signaling and development [58].

Tedja et al. [59] reported a meta-analysis that included data from both 23andMe and CREAM and increased the study sample to over 160,000 individuals. The investigation revealed several genetic loci linked with refractive error and myopia. This study highlighted new loci involved in light-induced signaling pathways, extracellular matrix composition, and neuronal development. Specifically, study key findings included associations with genes such as GJD2, RASGRF1, and ZMAT4 [59].

Despite the significant progress in identifying genetic factors associated with myopia, there is still much work to validate these findings and understand their functional implications. Future research should focus on replicating these genetic associations in diverse populations and exploring the biological mechanisms through which these genes influence myopia development. Interestingly, some of the genes identified as players in the development of isolated myopia, such as RDH5 and RGR, are also linked to the development of IRDs.

Myopization is the process by which the eye undergoes changes that lead to the progression and development of myopia. Intricate molecular pathways govern the progression and development of myopia but despite extensive research, the precise mechanisms underlying myopia’s development remain unclear and several molecular pathways have been proposed to explain it [60].

One of the key molecular mechanisms proposed concerns the role of neurotransmitters in the retina, specifically dopamine. Study has shown that dopamine is involved in regulating eye growth and reduced dopamine levels have been associated with increased eye elongation and myopia [61]. Furthermore, light exposure triggers signal transduction pathways in the retina, affecting dopamine release, which suggest that environmental related factors such as outdoor activity can modulate myopization through retinal dopamine pathways [62, 63].

Various growth factors, like transforming growth factor beta (TGF-

Moreover, recent reports suggest that hypoxia in the sclera may play a crucial role in the development of myopia. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1

Hyperopia is significantly influenced by genetic factors, particularly in the context of inherited retinal dystrophies. Research has pinpointed several genetic loci associated with hyperopia through genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Notably, genes such as LAMA2, which is involved in extracellular matrix formation, and RDH5, related to retinoid metabolism, have been implicated in hyperopia [58, 69]. Inherited retinal dystrophies studies have revealed that mutations in these and other genes can disrupt normal eye development and function, leading to refractive errors like hyperopia. For instance, mutations in the PAX6 gene, known for its role in eye development, have been linked to various ocular conditions including hyperopia [70, 71]. Additionally, studies have shown that hyperopia can be a presenting feature in conditions like retinitis pigmentosa, further underscoring the genetic underpinnings of this refractive error [70, 71]. Understanding these genetic influences is crucial for developing targeted therapies and improving diagnostic accuracy for individuals with hyperopia related to inherited retinal dystrophies.

For the literature evaluation, studies were chosen according to certain essential criteria: (1) The significance of the molecular mechanisms that connect inherited retinal dystrophies (IRDs) with refractive errors. (2) The publication date should be within the last 10 years to include the most recent findings. (3) The studies should present substantial experimental or clinical data that support the relationship between retinal function and ocular axial length. Only scholarly papers that have undergone a rigorous evaluation process by experts in the field, as well as studies that analyze and combine data from multiple sources, were taken into account to ensure the reliability and excellence of the material.

The selected methodology for this study, which mostly entails the examination of pre-existing literature and genetic data, possesses specific constraints. An important constraint is the dependence on previously published studies, which may not comprehensively encompass emerging or unpublished data. Furthermore, although genetic correlations can be determined, establishing causality is difficult due to the intricate interplay between genes and the environment, as well as the multifaceted nature of both inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) and refractive errors. Additional empirical verification and extended longitudinal investigations are necessary to confirm the results and delve into the underlying causal mechanisms in more detail.

Insufficient comprehension of the relationship between IRDs and refractive errors is prevalent in current research, as these two conditions are generally studied independently without considering their possible links. Refractive errors in individuals with inherited retinal diseases (IRDs) are common. There has been limited research conducted on the specific processes that could potentially connect retinal degeneration with aberrant ocular growth. A thorough analysis is required to integrate these characteristics and reveal common molecular pathways.

Although there is evidence linking genetic mutations and retinal dysfunction to ocular growth, the precise molecular mechanisms that elucidate the common association between IRDs and refractive errors are yet inadequately comprehended. The current body of research is insufficient in providing precise information on the role of alterations in retinal signaling, neurotransmitter pathways, and extracellular matrix interactions in the development of retinal disease and refractive aberrations.

Current research frequently concentrates on retinal degeneration or refractive error separately. There is a notable lack of knowledge on the interactions across pathways relevant to retinal function and development, including those involving dopamine signaling, extracellular matrix remodeling, and gene expression. These interactions have an impact on the course of inherited retinal diseases (IRD) and refractive errors. By addressing this gap, we could uncover new and valuable insights about the interconnectedness of these conditions.

The existing literature does not adequately investigate how a more comprehensive understanding of the shared processes between IRDs and refractive errors could influence treatment approaches. An opportunity exists to enhance therapy methods by focusing on common biological pathways, perhaps leading to improved results for individuals with both illnesses.

Retinal function in the normal eye is crucial for regulating eye growth during development via intricate molecular signaling networks. Retinal signaling disruption, observed in inherited retinal diseases (IRDs), can result in atypical eye growth and the development of myopia.

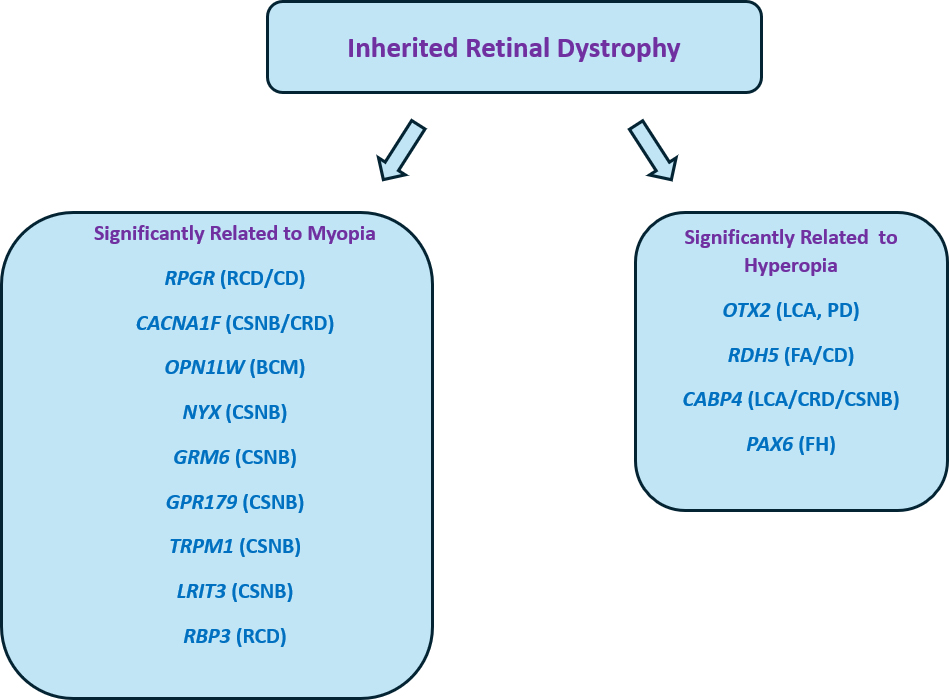

The signaling pathway using retinoic acid (RA): Retinoic acid, which is generated from vitamin A, plays a vital role in the formation and growth of the eyes. RA signaling is believed to play a role in controlling the length of the eye’s axis. Disruptions in the genes involved in RA metabolism, such as RDH5 (11-cis retinol dehydrogenase), can interfere with the normal growth of the eye, causing it to elongate excessively. In individuals with inherited retinal diseases (IRDs), the disturbed process of visual cycle and atypical amounts of retinoic acid (RA) can serve as indicators for the sclera to undergo remodeling, which in turn promotes the advancement of myopia. Some particular genes display a significant association with refractive errors (myopia or hyperopia). The underlying mechanism could be related to the specific roles of causing genes, such as eye morphogenesis, visual perception, retinal signaling or extracellular matrix organization [3, 13] (Fig. 1). Several reports have shown that changes in retinal function can contribute to changes in the axial length of the eye itself through complex molecular interactions. Several biochemical signals such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and retinoic acid appear to be crucial during embryonic eye development because they regulate axial length [72, 73, 74]. Furthermore, activation of specific signalling pathways, such as the Wnt/

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Main genes displaying phenotypes with typical refractive error. RCD, rod-cone dystrophy; CD, cone dystrophy; CSNB, congenital stationary night blindness; BCM: blue cone monocromacy; LCA: leber congenital amaurosis; FA: fundus albipunctatus; PD: pattern dystrophy; FH: foveal hypoplasia; CRD, cone-rod dystrophies.

A clear overview of the main genetic components potentially linking IRDs and refractive errors, emphasizing the shared molecular mechanisms can be found in Table 1 (Ref. [3, 8, 9, 47, 57, 58, 59, 69, 72]).

| Gene | Associated condition(s) | Function | Molecular pathway | References |

| PAX6 | Aniridia (Myopia/Hyperopia) | Transcription factor involved in eye development | Wnt/ | [9, 47] |

| RPGR | Leucine-rich repeat, immunoglobulin-like and transmembrane domains | GTPase regulator | [8, 9] | |

| CACNA1F | CSNB (Myopia) | Retina-specific expression with synaptic localization of protein | Signaling cascade | [8, 9] |

| NYX | Complete CSNB (Myopia) | Cell adhesion and axon guidance | Disruption of developing retinal interconnections involving the ON-bipolar cells | [8, 9] |

| TRPM1 | Complete CSNB | Mediates transient Ca+ flux in retinal ON bipolar cells | Signaling cascade initiation | [3, 8] |

| GPR179 | Complete CSNB (Myopia) | G protein-coupled receptor expressed in retinal bipolar cells | Signaling cascade | |

| RBP3 | Recessive Retinitis Pigmentosa (Myopia) | Binds and transports retinoids in the interphotoreceptor matrix between the RPE and photoreceptors | Retinoid metabolism | [9] |

| RDH5 | Recessive fundus albipunctatus, recessive cone dystrophy (Hyperopia) | RPE microsomal enzyme involved in converting 11-cis retinol to 11-cis retinal | Retinoid metabolism | [8, 58, 69] |

| SIX6 | Glaucoma (Myopia) | Regulates eye development and retinal ganglion cell survival | Axial length regulation, Neurotransmitter signaling | [9, 57] |

| GJD2 | Night blindness (Myopia) | Encodes connexin 36, involved in gap junctions in retina | Dopamine signaling, Gap junction communication | [9, 59] |

| OPN1LW | Blue cone monocromacy, macular dystrophy (Myopia) | Long-wave sensitive opsin | Phototransduction, Opsin signaling | [9] |

| VEGF | Retinal dystrophies (Myopia) | Vascular endothelial growth factor, involved in angiogenesis | Regulation of ocular blood supply, Axial length modulation | [72] |

| RAX2 | Retinal dystrophies (Hyperopia) | Essential for retinal development | Eye morphogenesis, Axial length control | [8, 9] |

| SOX2 | Microphthalmia (Hyperopia/Myopia) | Regulates stem cell maintenance and differentiation | Neurogenesis, Axial length regulation | [9] |

| OTX2 | Dominant LCA and pituitary dysfunction, recessive microphthalmia, dominant pattern dystrophy | Transcription factor and involved in retinal and ocular development | Eye morphogenesis, Axial length control | [8, 9] |

IRDs, inherited retinal diseases; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

It is vital to recognize the constraints of this work. Although the genetic links between inherited retinal dystrophies (IRDs) and refractive errors have been investigated, the intricate nature of these disorders means that not all elements that contribute to them have been completely understood. The study largely emphasizes established genetic pathways and molecular interactions, but it does not thoroughly address environmental impacts and gene-environment interactions, which could potentially have a significant impact on the progression of diseases. Moreover, the diversity of IRDs and the variation in how refractive errors are presented in different groups may introduce variability that restricts the applicability of the results. Possible alternative explanations for the observed connections could involve undiscovered genetic variations or epigenetic factors that were not considered in our analysis. These factors could possibly independently contribute to the development of refractive defects, separate from the mechanisms already mentioned. Additional study that includes a wider variety of parameters is necessary in order to gain a complete understanding of the intricate relationship between IRDs and refractive errors.

Understanding the various factors that contribute to myopic development and progression is of fundamental importance for public health, patient health, and the economic and social impact that this disease has globally. From an epidemiological perspective in urbanised regions, particularly in East Asia, myopia is steadily increasing [84, 85]. Environmental and genetic factors undoubtedly contribute to this, with research into genetic markers and inheritance patterns being a key point in patient management [86]. Several studies have identified the SOX2, OTX2 and RAX genes as possibly responsible for axial length, whose mutations are correlated with alterations in eyeball length [86, 87, 88, 89]. Other important genes are SIX6, PAX6, ZFHX1B, as well as multiple gene variants as analysed by genome-wide association studies (GWAS). These genes would exert their action both through the regulation of neurotransmitters and through the phenomena of cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis [87, 88, 89]. A very important impact is certainly also given by lifestyle, e.g., prolonged use of near vision, intensive use of electronic devices or prolonged reading and lack of free time outdoors (it would appear that sunlight through mechanisms involving dopamine is protective against myopia progression) certainly have a fundamental importance in the development and progression of myopia [88, 89, 90, 91, 92]. Some reports suggest a potential role also of physical activity in reducing myopia progression, although studies in this sense are still promising but inconclusive [91, 92, 93]. The correlation between defocus and myopia is also relevant. Specifically, it would appear that positive peripheral defocus (where the image is hypermetropically blurred) could partially slow down the progression of myopia, while negative peripheral defocus (where the image is myopically blurred) could promote its progression [94]. Another relevant factor is the correlation between pollution and myopia, as several studies have shown that high levels of air pollution are correlated with an increase in myopic prevalence. In this sense, PM2.5 and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) would seem to be involved, which through phenomena related to oxidative stress and inflammation, vasoconstriction of ocular blood vessels and neurochemical dysregulation, would be involved in myopia progression [95]. Finally, the correlation between retinal function and myopia should be noted. Pathologies leading to dysfunction of the retina, bipolar cells or photoreceptors lead to dysfunctional ocular growth. This is due to visual feedback phenomena that are inextricably linked to axial length [96]. Therefore, the more we know and study the factors linked in the development of myopia, the more we will be able to identify high-risk patients early on and use preventive options to slow myopic progression. Pending further developments, it is of paramount importance to develop public policies that increase general awareness and incentivise healthy behaviours aimed at reducing myopic progression [97].

Myopia, or nearsightedness, has become a prevalent condition globally, necessitating an urgent need for effective interventions. Emerging research has highlighted several potential treatments aimed at controlling the progression and onset of myopia. Numerous studies have shown the potential role of inflammation in myopic progression, in particular certain cytokines (tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-

Novel techniques that can offer innovative information on the patterns of gene expression can help us better understand the intricate connections between retinal dystrophies and refractive errors. Integrating the results from various studies would strengthen our comprehension of the common molecular mechanisms and maybe offer a more all-encompassing perspective on how these mechanisms contribute to the development and advancement of these illnesses. Future research should include examining these transcriptome datasets to verify and extend the mechanisms highlighted in our paper [106, 107]

This study primarily investigates the correlation between specific gene mutations and refractive errors. It is worth mentioning that the intensity of refractive errors, such as myopia, can greatly differ among patients who possess particular genes like OPN1LW, which is linked to blue cone monochromacy (BCM). For example, certain patients with BCM may have severe nearsightedness, while others may show more moderate or even mild manifestations of the condition [5]. The presence of heterogeneity in the population indicates that other genetic and environmental factors likely contribute to the varying degrees of myopia in these patients. Additional investigation is required to gain a deeper comprehension of these relationships and to ascertain any regular trends in the intensity of refractive errors among patients with particular gene alterations.

Mechanisms underlying the process of eye elongation are complex and still largely poorly understood. The fact that inherited retinal dystrophies caused by specific genes display peculiar and significant refractive errors, could lead to the clarification of the cross-talk between the retina and the scleral structures. While some genes have well defined developmental or structural roles, others probably act through neurotransmitters signaling. The study suggests that it would be beneficial to create specific screening procedures for persons with inherited retinal dystrophies who are more likely to acquire refractive defects. Gaining knowledge about the shared biological pathways in both illnesses might also inform tailored treatment strategies, including timely administration of pharmacological drugs or gene therapies that target these pathways. Moreover, the knowledge acquired from investigating the common mechanisms between inherited retinal diseases and refractive errors could contribute to the development of more comprehensive public health approaches to tackle the progression of myopia in the overall population. This could potentially result in the creation of novel preventive measures or treatment choices that are guided by genetic and molecular research.

FD and MZ designed the research study. FD, CG, AA, GG, MM, MC, FV, ED, MFC and MZ performed the research. FD, CG, MM, and MZ analyzed the data. FD, CG, AA, GG, MM, MC, FV, ED wrote the manuscript. MFC revised and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Francesco Cappellani, Dr. Carlo Musumeci and Dr. Massimiliano Cocuzza for their constructive contribution in discussing the relevant aspects of the subject of this review.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.