1 Institute of Biochemistry and Physiology of Plants and Microorganisms, Saratov Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IBPPM RAS), 410049 Saratov, Russia

Abstract

Phages have exerted severe evolutionary pressure on prokaryotes over billions of years, resulting in major rearrangements. Without every enzyme involved in the phage–bacterium interaction being examined; bacteriophages cannot be used in practical applications. Numerous studies conducted in the past few years have uncovered a huge variety of bacterial antiphage defense systems; nevertheless, the mechanisms of most of these systems are not fully understood. Understanding the interactions between bacteriophage and bacterial proteins is important for efficient host cell infection. Phage proteins involved in these bacteriophage–host interactions often arise immediately after infection. Here, we review the main groups of phage enzymes involved in the first stage of viral infection and responsible for the degradation of the bacterial membrane. These include polysaccharide depolymerases (endosialidases, endorhamnosidases, alginate lyases, and hyaluronate lyases), and peptidoglycan hydrolases (ectolysins and endolysins). Host target proteins are inhibited, activated, or functionally redirected by the phage protein. These interactions determine the phage infection of bacteria. Proteins of interest are holins, endolysins, and spanins, which are responsible for the release of progeny during the phage lytic cycle. This review describes the main bacterial and phage enzymes involved in phage infection and analyzes the therapeutic potential of bacteriophage-derived proteins.

Keywords

- bacterial protein

- phages

- phage protein

- infection

More than half a century of use of bacteriophages as convenient research objects has led to numerous discoveries in the fields of molecular and structural biology, physiology, and evolution of microorganisms and viruses. It has also led to the development of physicochemical methods for studying microobjects. Bacteriophages are widespread in nature and are important in controlling the size of microbial populations and in the transfer of bacterial genes, acting as vector “systems” [1]. Bacteriophages can act as mobile genetic elements that introduce new genes into the bacterial genome through transduction. Bacteriophages are capable of infecting about 1024 bacteria in 1 sec [2, 3], which indicates the continuous transfer of genetic material between bacterial cells in the same ecological niche. Properties such as a high level of specialization, the ability to reproduce rapidly in a suitable host, and resistance to various environmental influences help bacteriophages maintain a dynamic balance among a wide variety of bacteria in any ecosystem. In the absence of a suitable host, many phages retain their infectious potential for decades unless they are destroyed by aggressive chemical agents or extreme environmental conditions [4]. The estimated size of the global phage population is more than 1030 phage particles [5].

Because most phages destroy the infected cell at the end of the lytic cycle, viral infection frequently has a negative effect on bacterial cells. Phage attachment occurs when the genetic material is injected into the cytoplasm by the phage, where nucleic acids replicate, transcriptionally transcribe, and translate to generate new viral proteins and progeny phages. The many stages of the infection cycle have been taken into consideration in the evolution of bacterial defense mechanisms. Utilizing multiple antiphage systems, bacteria usually target mobile genomic components that are shared across the pangenome. The “panimmune system” that results from this array of antiphage systems is reliant on the ability of antiphage genes to operate in various host cells, to have potential addiction modules, and to be encoded in a single gene or operon [6].

Different types of bacteria encode antiphage defense systems that differ in their mechanism of action. The most common systems of this type are those that target phage nucleic acids and degrade them. Restriction modification (RM) systems cleave bacteriophage DNA upon recognition of specific motifs in the nucleic acid sequence. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated nucleases (Cas) (CRISPR-Cas) systems operate by recognizing and interacting with regions of phage genetic material through adaptive immune memory. This memory is achieved by acquiring short sequences of viral DNA that are incorporated into the bacterial genome (“spacers”). These sequences are transcribed and modified, and through the CRISPR-Cas mechanism, they interact with the viral nucleic acid, preventing infection and assembly of phage particles. Type III CRISPR-Cas systems, in addition to cleaving the phage nucleic acid, can generate cyclic oligoadenylate (cOA) signaling molecules, which activate effectors that kill the infected cell or lead to cell division arrest. Prokaryotic argonaut proteins (pAgo) are also involved in the cleavage of phage DNA or RNA to limit the spread of the virus [7]. This work summarizes information regarding the main systems protecting bacteria against phage infection, examines data on viral protective mechanisms aimed at overcoming bacterial “immunity”, and evaluates the therapeutic potential of bacteriophage-derived proteins.

Bacterial viruses range in size from about 20 to 200 nm and are hundreds or thousands of times smaller than microbial cells. A typical phage particle (virion) consists of a head and a tail [4]. The length of the tail is in most cases 2–4 times the diameter of the head. The head contains genetic material – single- or double-stranded nucleic acid, surrounded by a protein or lipoprotein shell (the capsid), which preserves the genome outside the cell [4]. The nucleic acid and capsid together form the nucleocapsid.

Bacteriophages are classified as either DNA- or RNA-containing on the basis of the type of nucleic acid they carry, as per the International Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses [8]. The families Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, Podoviridae, Lipothrixviridae, Plasmaviridae, Corticoviridae, Fuselloviridae, Tectiviridae, Microviridae, Inoviridae Plectovirus, and Inoviridae Inovirus are groups of DNA-containing bacteriophages based on their morphological traits. The two families of RNA viruses are Leviviridae and Cystoviridae.

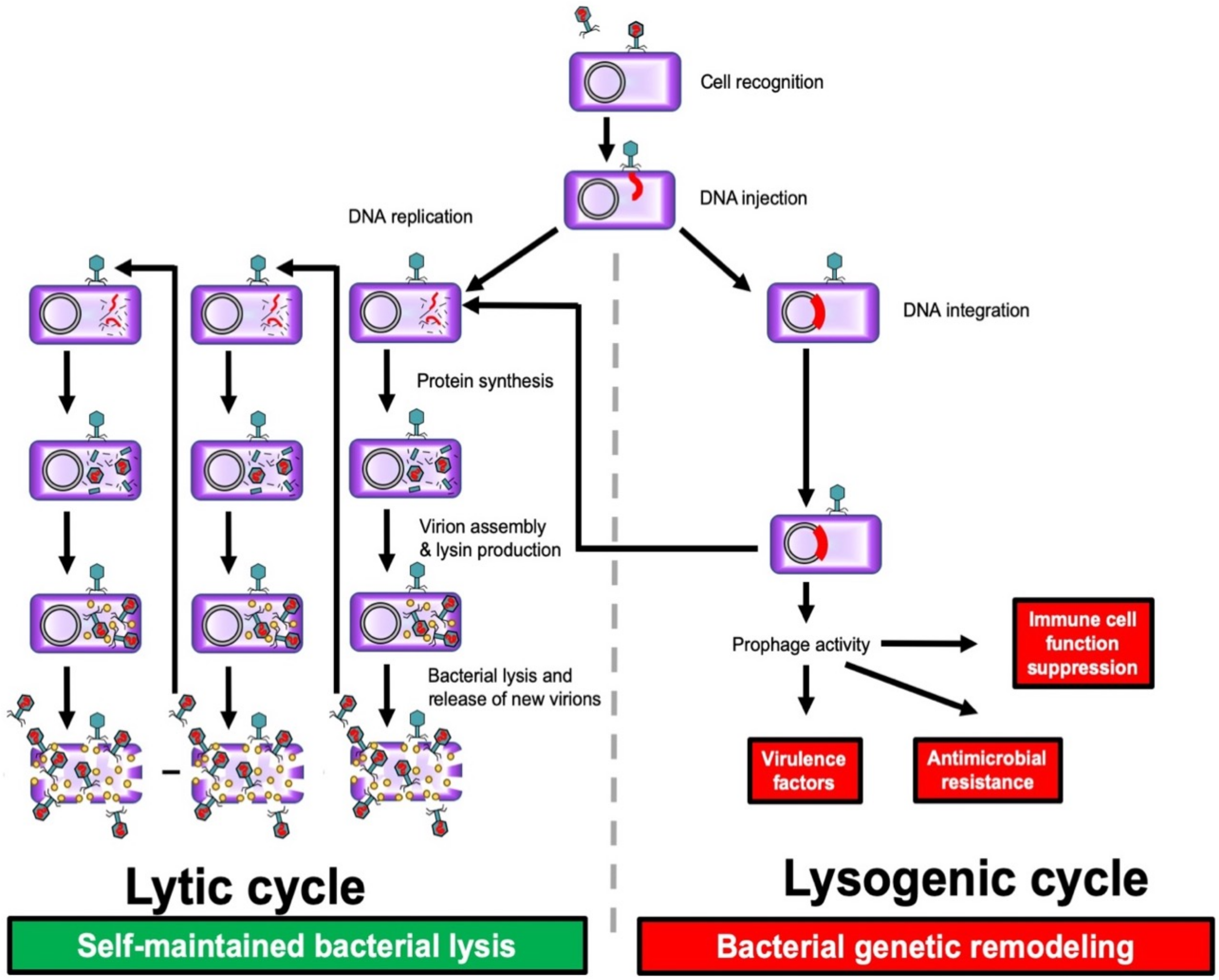

The two most prevalent genera are Sapexavirus, with 25 phages, and Efquatrovirus, with 39 phages [9]. There have been nearly three times fewer isolates characterized with myoviral (long contractile tail) and podoviral (short tail) morphology [9]. Additionally, there are differences in the morphology, chemical makeup, and mode of action of bacteriophages. Temperate and pathogenic phages can be differentiated on the basis of the type of interaction they have with bacterial cells [10, 11, 12]. Temperate phages can cause bacteria to become lysogenic, whereas virulent phages cause the lytic destruction of cells. The following phases can be identified in the infection of microbial cells by a pathogenic phage: (1) Phage particles adhere to microbial cell surfaces; (2) Phage genetic material is introduced into the microbial cell; (3) Phage particles form inside the bacterial cell; (4) Phage particles are released from the cell upon lysis (Fig. 1, Ref. [12]).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Lysogenic and lytic phage cycles. Bacteria (purple); bacteriophage (green); phage DNA (red); lysin (yellow). Reproduced with permission from Ferry et al., [12] Viruses; published by MDPI, 2021.

In contrast to the lytic cycle, phages do not instantly destroy their host cell during the lysogenic cycle, also known as lysogeny, in which they integrate their chromosomes into the bacterial genome and remain latent as prophages [11].

Many phages can switch from the lytic cycle to the lysogenic cycle and back. If DNA damage occurs in the host bacterium, prophages can initiate a lytic cycle of development. Temperate phages carry the risk of altering the phenotype of target bacteria, and are an important tool for bacteria to acquire virulence factors and the complex regulatory mechanisms that control their expression [13].

Obligate lytic phages multiply exponentially within the bacterial cell. At the final stage of reproduction, most tailed phages produce lytic factors, for example, peptidoglycan hydrolase, to ensure exit from the cell and distribution of descendant phages after lysis [4]. Phages are highly specific with respect to their host range, and only in rare cases are they able to infect bacteria of different species or genera (polyvalent phages).

Bacteriophages have the unique ability to recognize certain specific molecules present on the surface of bacteria. The interaction between phages and the corresponding bacteria depends on a number of factors such as phage morphology, bacterial surface composition and structure [14, 15], and the existence of F-pili in bacteria [16, 17].

Bacteriophages attach to the surface of bacterial cells through specialized chemicals called lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) and also through fimbriae, flagella, and several types of proteins [18]. To get to the cell surface receptor, bacteriophages that infect encapsulated bacteria must break through the capsular barrier. These phages mimic the enzyme-substrate reaction by binding to capsular polysaccharides and breaking down the cell wall. A wide variety of molecules can function as receptors owing to the varied structural makeup of the surface of bacterial cells. Teichoic and lipoteichoic acids, which are components of the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria, may be involved in recognition. LPSs, outer membrane proteins (such as porins), pili, and flagella are examples of target molecules in Gram-negative bacteria [19].

Phage tails are essential to infection. Tail attachment sites and bacterial surface elements interact specifically in the phage tail and its receptor binding proteins (RBPs) to influence host cell recognition [19]. With the aid of tail fibrils, phages possessing a contractile sheath adsorb on the bacterial cell surface. The sheath of the tail contracts, and the spike is inserted into the cell when the phage enzyme ATPase is activated.

Adsorption of phages to the host cell consists of interactions between phage-binding proteins and the corresponding receptors on the surface of the cell membrane [20]. The infection of Escherichia coli bacteria containing F-pili by the temperate phage M13 has been described in detail [21, 22, 23, 24]. The interaction of temperate phages with microbial cells begins with the adsorption of the phage on the surface. Infection of E. coli cells by the temperate bacteriophages M13, fd, and f1 begins with the interaction of the minor phage capsid protein gene 3 protein (g3p) with bacterial F-pili, which are the primary receptor of the phage, and subsequently with the integral membrane protein TolA, which ensures the penetration of single-stranded circular phage DNA into the cytoplasm [21]. Further changes in the host cell are associated with various damage to intracellular structures caused by the release of viral DNA into the cytoplasm of E. coli, while the capsid protein (g8p) is integrated into the inner cytoplasmic membrane. In the cytoplasm, phage DNA is converted by cellular enzymes into a double-stranded structure called the replicative form (RF). The RF replicates according to the usual semiconservative mechanism for circular double-stranded DNA and serves as a template for transcription. As a result, among other phage proteins, a gene II product is formed, a kinase that introduces a break in the (+) RF chain [21].

The phage tail contains the enzyme lysozyme, which aids in “piercing” the bacterial cell wall. The phage DNA enters the cell through the tail spike’s chamber and enters the cytoplasm when the cell wall has been damaged. The phage’s appendage and capsid stay outside the cell, serving as its remaining structural components. Up to 200 more phage particles can build up in the bacterial cell following the production of phage components and their self-assembly. The bacteria are lysed, the cell wall is damaged, and phage progeny are released into the environment by the action of phage lysozyme and intracellular osmotic pressure.

Phage bacteriolysis can happen either at the adsorption stage, when many phage particles bind to a single bacterial cell (lysis from the outside), or at the end, when the cell wall is destroyed by the endolysin–holin–spanin system or the lysis system of a single protein (lysis from the inside) [25, 26, 27]. The bacteriophage creates a number of proteins during the infection cycle that are crucial to its reproduction and the release of progeny phages from the infected bacterium, which results in cell death. A single lytic cycle takes roughly 30 to 40 min starting from the time the phages bind to the cell and ending when they leave. Until every bacterium susceptible to a particular phage is lysed, the bacteriophagy process runs through multiple rounds.

The phage viral particle, in particular the tail apparatus, is equipped with a set of enzymes necessary for the phage to pass through protective barriers that block access to cellular receptors, as well as for the destruction of the polymer components of the bacterial surface. Most of these enzymes belong to the broad group of proteins that (i) break down polysaccharides and are known as polysaccharide depolymerases; (ii) cleave peptidoglycans of the cell wall and are known as peptidoglycan hydrolases [28, 29, 30, 31].

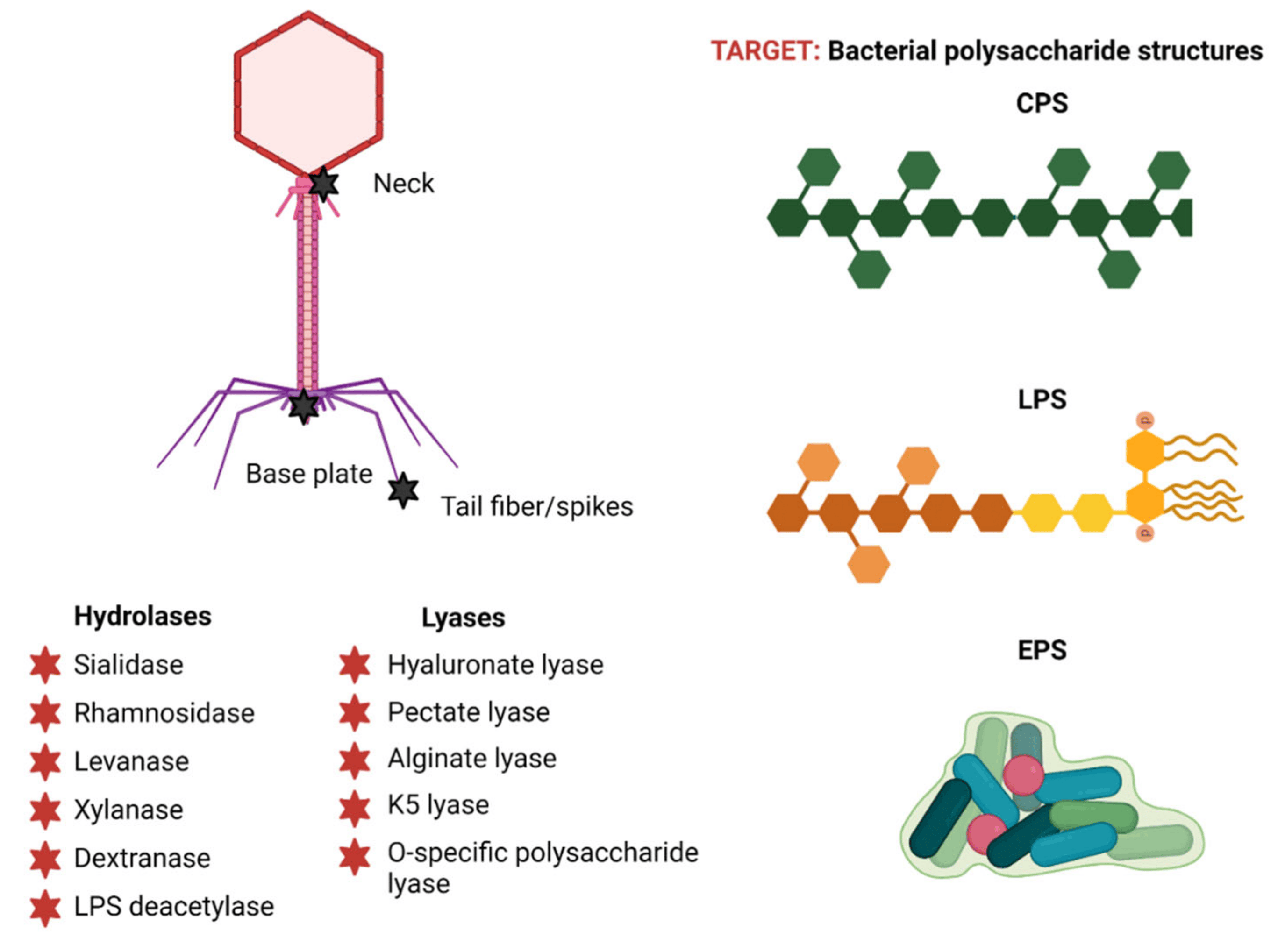

Depolymerases break down extracellular polysaccharides (EPSs), which include polysaccharides that comprise the biofilm capsule or matrix of bacterial communities. They also break down structural elements of the cell wall, such as peptidoglycan glycan moieties, or lipopolysaccharides (Fig. 2, Ref. [31]). Approximately 160 potential depolymerases that are implicated in the infection of 24 bacterial taxa have been found so far in 143 sequenced phages. Polysaccharide depolymerases target and break down structures crucial to cell survival and virulence; hence, they may be useful in combating harmful bacterial diseases [30, 32, 33].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Phage polysaccharide depolymerases: structure and classification. Reproduced with permission from Danis-Wlodarczyk et al., [31] Antibiotics; published by MDPI, 2021. EPSs, exopolysaccharides; LPSs, lipopolysaccharides; CPSs, capsular polysaccharides.

In the event of cell lysis as a result of phage infection, depolymerases can be released as free enzymes. This process occurs either due to the production of an excess of proteins during infection, which are ultimately not included in virions during assembly, or due to the inclusion of an alternative variant of their translation, which is accompanied by the formation of both soluble and virion-associated forms. Such unincorporated forms of depolymerases can diffuse freely, degrading bacterial polysaccharides at some distance from the development of the primary phage infection [31, 34].

Bacteria frequently make capsules or outer protective biopolymer layers on their surface. Most of these capsules contain carbohydrates. The capsular carbohydrate-containing substance in pathogenic bacteria can be a strong virulence factor that interferes with the ability of host immune cells to recognize pathogens and inhibits phagocytosis [35]. Additionally, by hiding phage attachment receptors, capsules can shield bacteria from phage infection. Bacteriophages, on the other hand, have mastered the utilization of polysaccharide shells as receptors to start an infection. These phages typically carry many copies of one or more tail spin types, each of which interacts and compromises the integrity of capsules made of a certain material [36, 37, 38]. These tail spikes enable virions to pass through the capsule layer and directly reach secondary receptors in the cell wall, which start subsequent stages of viral DNA penetration into the bacterium. Processive depolymerase activity is the reason for this, as it consists of sequential cleavage of polymer bonds without dissociation of the virus [30].

The LPS O-specific chain in Gram-negative bacteria is an important receptor that bacteriophage virion depolymerases identify and hydrolyze. The tail spines of Podoviridae include the best-characterized LPS-hydrolyzing receptor-binding proteins. When phages come into contact with an outer membrane protein (Omp) or another secondary receptor in the outer membrane, they can pass through the LPS layer thanks to their tail spikes. This opens the viral particle and allows DNA to be injected into the target cell [30, 39]. Certain bacterial strains, particularly those that have evolved, lack O-polysaccharide, which prevents some bacteriophages from recognizing and infecting O-antigen cells. In vitro experiments have shown that highly purified LPSs, when incubated with virions having this type of tail spike, can stimulate the release of phage DNA [40, 41].

Bacteriophages can also encode EPS depolymerases, which facilitate the easy penetration of phages through the biofilm matrix and infection of bacteria sensitive to them [30, 42, 43]. In addition, these depolymerases can be successfully used as therapeutic agents aimed at combating infections associated with bacterial biofilms, because the structural basis of the biofilm matrix can be, among other things, EPS. Depolymerases effectively cleave EPS chains, disrupting the integrity of biofilms and making them more susceptible to treatment with antimicrobial drugs [31, 44].

Owing to their extensive substrate specificity, polysaccharide depolymerases fall into two classes on the basis of how they function: hydrolases and lyases (Fig. 3). Six families of hydrolases are known to catalyze the hydrolysis of glycosidic linkages [31, 32]:

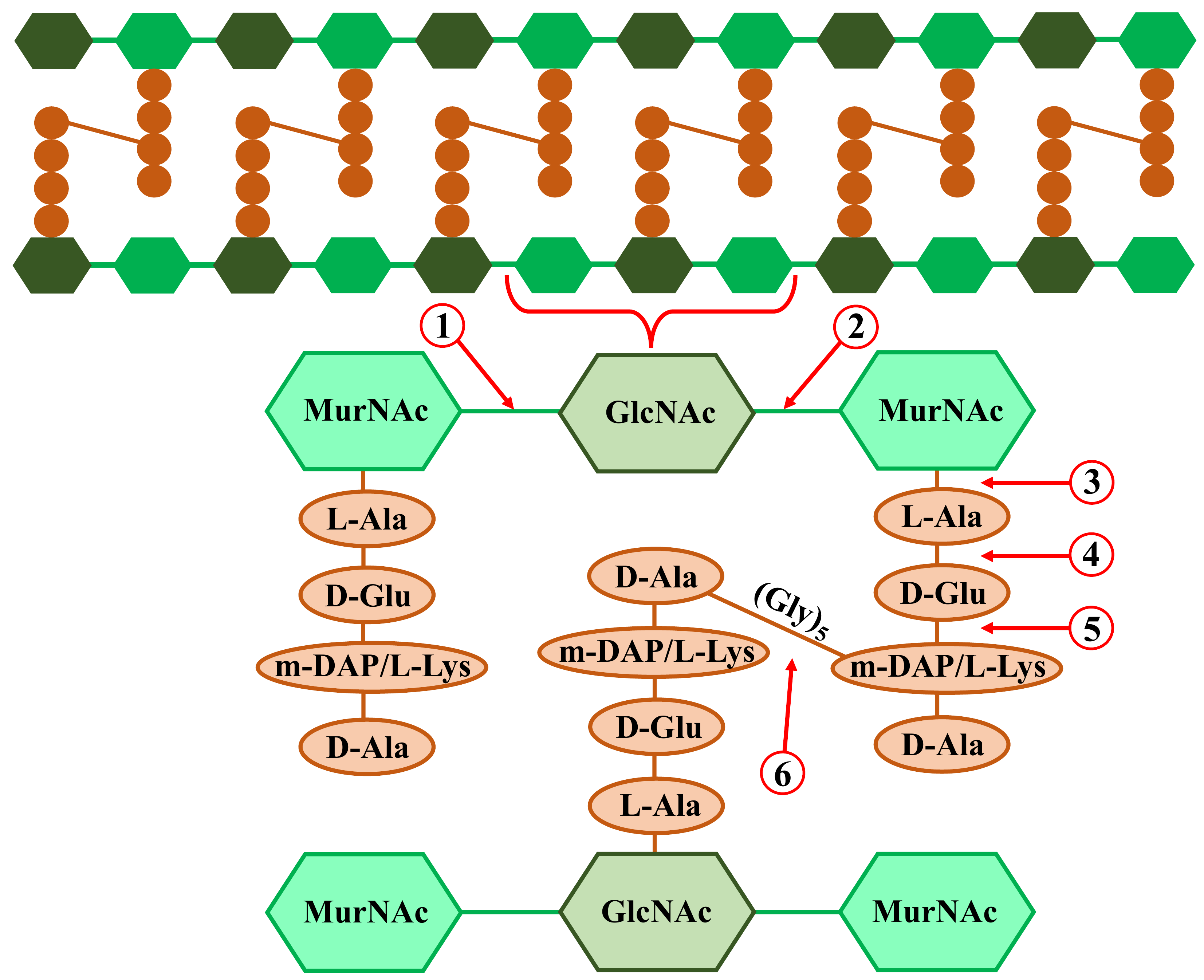

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Bacterial peptidoglycan structure and possible phage peptidoglycan hydrolase (endolysin or ectolysin) cleavage sites. Including: (1) N-acetyl-

1. Sialidases: they hydrolyze

2. Rhamnosidases: they break down the

3. Xylanases: break

4. Levanases: cleave

5. Dextranases: break down the

6. Deacetylases: deacetylating the O-antigen of LPS [50].

Five families of lyase enzymes are involved in the

1. Hyaluronate lyases: they hydrolyze the

2. Pectate lyase: it breaks down the EPS in bacterial biofilms by hydrolyzing the

3. Alginate lyases are encoded by some phages of the bacterial genera Azobacter and Pseudomonas, and they cleave the

4. K5-lyases: they break the

5. O-specific polysaccharide lyase: it degrades the LPS O-specific antigen [54].

Subsequently, we will examine in greater detail the most prevalent members of the hydrolase and lyase groups categorized as polysaccharide depolymerases.

3.1.1.1 Endosialidases

Endo-N-acetylneuraminidases, often known as endosialidases or endoNs, are glycosyl hydrolases (EC 3.2.1.129). These enzymes are part of the enzymatic equipment found in the tail spike of bacteriophages, which use a K1 type capsule apparatus to infect harmful bacteria (such as E. coli) [28, 55]. Endosialidases specifically recognize and hydrolyze internal

Pathogens can efficiently elude the immune system’s defense response, because polysialic acid can mimic the structure of polysaccharides in the host organism. It is known that endosialidases are carried by about 30 K1-specific phages [57, 58]. At least five distinct DNA-containing phages (K1A, K1E, K1F, 63D, and K1-5), belonging to the families Podoviridae, Myoviridae, and Siphoviridae, have had their endosilyase genes cloned and expressed [28, 59]. Additionally, a vast array of genes producing endosilyases is present in temperate phages [60, 61]. Endosiliases have a special ability to break down the bacterial capsule material, which can be used to lessen the virulence of harmful diseases. In this instance, the use of endosiliasis medications to treat a variety of systemic diseases brought on by encapsulated bacteria will be successful, because the method involves breaking down the capsular polysaccharide rather than directly lysing the bacteria. The primary virulence factor of these pathogens, the K-antigen, is lost, which makes the modified phenotype of bacterial cells more susceptible to standard antimicrobial medications and host immune system components such as complement protein function or macrophage phagocytosis [28, 62].

3.1.1.2 Endorhamnosidases

Enzymes of the glycoside hydrolase 90 family, known as endorhamnosidases (EC 3.2.1.), are responsible for identifying and depolymerizing the repetitive carbohydrate units of the LPS O-antigen. Alginate lyases break down the

3.1.1.3 Alginate Lyases

The depolymerization of alginate, a linear copolymer of 1,4-linked

3.1.1.4 Hyaluronate Lyases

Enzymes called hyaluronate lyases (HyaLs, EC 4.2.2.1) hydrolyze hyaluronic acid or hyaluronan. A linear heteropolysaccharide made up of repeated disaccharide units connected by

Most of the time, these enzymes are oligomeric, with the C-terminal domain housing the active core [51, 69]. The pathogenic hemolytic group A streptococci Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus equi were reported to be infected by phages containing hyaluronate lyase [70, 71, 72]. The majority of hyaluronate lyase-encoding genes are located in prophages that are incorporated into bacterial chromosomes. These enzymes primarily break down the bacterial hyaluronic acid layer locally and decrease the capsule’s viscosity to allow access to the corresponding hidden receptors. The phage particle then attaches itself to these receptors and becomes recognized, leading to infection of the encapsulated cell. Phage hyaluronate lyases can exist in free, soluble, and virion-associated forms [28].

Ectolysins and endolysins are the two categories of phage peptidoglycan hydrolases, also known as lysins [73]. At the start of infection cycles, phages use ectolysins, also known as virion-associated peptidoglycan hydrolases (VAPGHs), to locally break down bacterial peptidoglycan. This allows the virus to insert its genome into the cell [74]. At the conclusion of the phage lytic infection cycle, endolysins are in charge of destroying the cell wall during phage lysis from the inside. Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria undergo different processes of endolysin-mediated cell rupture [75, 76].

Phage peptidoglycan hydrolases are capable of selectively affecting certain types of bacteria without causing harm to commensal microflora [31, 77]. They are effective at destroying bacteria, including those with multidrug resistance [78, 79]. Phage peptidoglycan hydrolases have been used to combat bacteria such as Bacillus anthracis, Clostridium spp., Enterococcus faecium, Klebsiella pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and S. pneumoniae [78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85]. Such enzymes can also be used to eradicate bacterial biofilms [86, 87] and to eliminate persister cells to eliminate the possibility of pathogen spread [88, 89]. As part of combination therapy for infectious diseases, along with various antimicrobial drugs, it is possible to use phage peptidoglycan hydrolases in combination with other enzymes of various origins [90, 91].

Because the peptidoglycan layer is encircled by an outer barrier with a complex composition in Gram-negative bacteria, unmodified peptidoglycan hydrolases have trouble reaching their substrate targets, in contrast to polysaccharide depolymerases [92]. In this regard, attempts have been made to use various lysins against Gram-negative pathogens in combination with chemical (EDTA, citric acid, malic acid, carvacrol, silver nanoparticles) or physical (high hydrostatic pressure) methods to destabilize the outer membrane [31, 93, 94]. Thanks to the achievements of modern synthetic biology and bioengineering, it has become possible to make conjugates of peptidoglycan hydrolases with peptides responsible for the permeability of hybrid molecules through the outer membrane [92]. In recent years, lysins have been identified as having a wide range of activities against various bacteria and a natural ability to penetrate the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria [31, 92, 95, 96, 97]. It is assumed that the mechanism of action of these lysins is associated with self-stimulated uptake of the C-terminal amphipathic helix, which interacts with the outer membrane, whereas the N-terminal enzymatic domain hydrolyzes peptidoglycan. It is possible that the C-terminal amphipathic helix, similar to phage spanin, destroys the outer bacterial membrane from the inside [92].

Phage peptidoglycan hydrolases are variable in terms of structure, catalytic activity, enzymatic reaction kinetics, and so on, despite the conservative nature of their roles. The structural variations between the cell walls of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria are linked to this diversity [31]. Because of this, enzymes that function against Gram-negative bacteria possess an enzymatically active domain (EAD) and a globular tertiary structure. On the other hand, the modular structure of enzymes unique to Gram-positive bacteria is made up of a C-terminal domain (CBD), a flexible interdomain linker region, and an N-terminal EAD [98, 99]. Teichoic acids, peptides, and carbohydrates are just a few of the epitopes on the surface of bacterial cell walls that CBDs attach to non-covalently to trigger the start of the EAD’s enzymatic activity [31, 100]. EAD lysins are classified into three types on the basis of the particular bonds within the peptidoglycan structure that they influence through their diverse catalytic actions (Fig. 3) [31]:

1. N-acetylglucosamines (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acids (MurNAc) are linked by

2. Amidases, also known as N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidases, break the amide bonds that bind amino acid L-alanine to pieces of carbohydrate chains;

3. Endopeptidases: break the bonds separating the amino acids in the peptidoglycan side-barrel peptide. These include D-Ala-m-DAP endopeptidase, D-alanyl-glycyl endopeptidase (CHAP), c-D-glutamyl-m-diaminopimelic acid peptidase (DAP), L-alanoyl-D-glutamate endopeptidase (VANY), and so on.

Regarding how the molecule’s three-dimensional structure is organized, there are certain peptidoglycan hydrolase exceptions. For instance, mycobacteriophages generate two types of lysin that contain EAD: lysin A (peptidoglycan hydrolase) and lysin B (mycolylarabinogalactan esterase) [101]. Ectolysins and endolysins are the two categories of peptidoglycan hydrolases that will be discussed below.

3.1.2.1 Ectolysins virion-associated peptidoglycan hydrolases (VAPGHs)

The structural elements of phage particles, called ectolysins, enable the local hydrolysis of peptidoglycan in the cell wall, enabling the phage tail to enter the cytoplasm and transfer viral DNA. VAPGHs are found in phages that infect both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and they resemble endolysins in terms of structure and organizational characteristics [29, 30]. This class of enzymes consists of big, multifunctional proteins that are frequently found in virions as oligomers. VAPGHs, which are elements of the nucleocapsid structure, may be crucial for the stability, infectivity, and morphogenesis of phage virus particles [102, 103]. Specifically, ectolysins could be unique tail protein domains or components like the central fiber, the puncture “device” at the tip of the phage tail, the tape measure protein (TMP), or protrusions. Furthermore, internal capsid proteins that are released when the virus opens may also be these enzymes [30, 33]. The contractile tail of bacteriophage T4, which is exclusive to E. coli, carries VAPGH. The bacterial cell’s surface receptors connect to the inner tail tube, causing it to contract. This allows the gp5 protein with mural activity located at the tip of the inner tail tube to pierce the cell membrane [104]. Phages with lengthy, noncontractile tails, such those in the Siphoviridae family (coliphage T5 and mycobacteriophage TM4), eject during entry and insert an inner tail tube made of the TMP roulette protein, which has peptidoglycan cleaving domains, into the cell wall [30, 105, 106, 107].

After irreversible adsorption to cellular receptors, coliphage T7, a member of the family Podoviridae, releases the proteins that make up the inner core of the capsid to form an extended tail tube enclosing the cell wall. One of the core proteins of this bacteriophage, namely gp16, has peptidoglycan-degrading activity [108].

Ectolysins are responsible for the local cleavage of peptidoglycans, which allows the phage tail to pass through the cell wall and fuse with the cell membrane. This process occurs regardless of where ectolysins are located in the virion structure or how they interact with the cell wall. When phages infect bacteria in physiological settings that encourage greater peptidoglycan cross-linking and ultimately result in cell wall thickening, VAPGHs may give them a competitive edge. Glycosidase or endopeptidase activities are typically present in the catalytic domains of VAPGH, which cleave the peptidoglycan layer; endopeptidase activities are primarily present in bacteriophages that exclusively infect Gram-positive bacteria [30, 109].

3.1.2.2 Endolysins

Endolysins are enzymes produced late in the life cycle of a lytic phage. These enzymes accumulate in the cytoplasm of the host bacterium until they pass through the holes formed by holins in the plasma membrane. Then they cleave peptidoglycan bonds in the cell wall, causing cell rupture and the release of daughter phages [110]. The biological activity of endolysins is quite high: they are capable of destroying a target cell within a few seconds after direct contact [29, 111]. The effect of endolysins is most effective against Gram-positive bacteria owing to the structural features of the cell wall [112]. Endolysins obtained from phages that infect Gram-positive bacteria have a characteristic domain structure and are divided into five groups depending on their enzymatic activity: (i) N-acetylmuramidase (breaking down carbohydrates), (ii) endo-

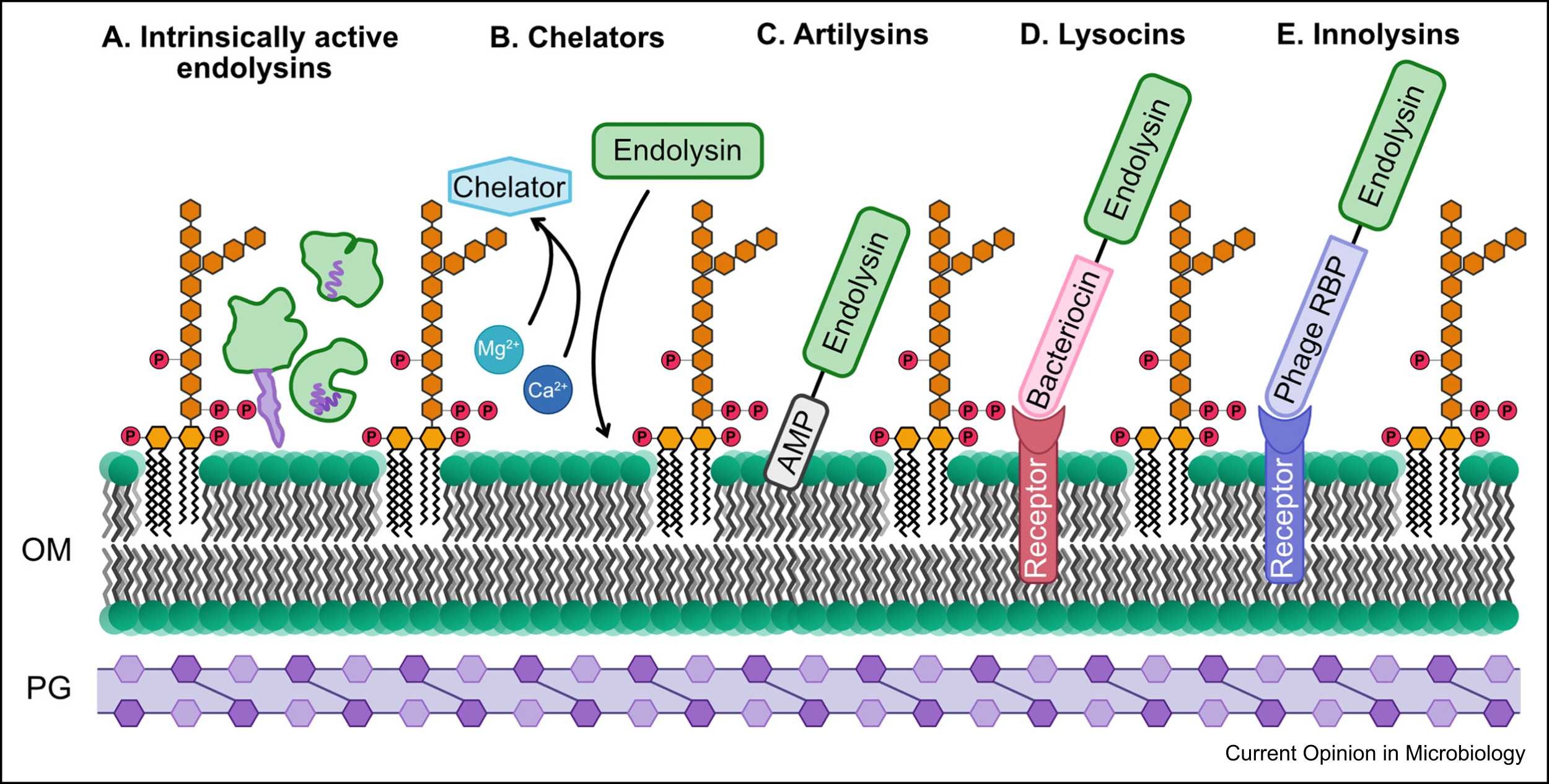

Gram-negative bacteria are infected by bacteriophages, which primarily produce globular proteins with no domains that interact with the cell wall (Fig. 4, Ref. [75]) [29]. Endolysins possessing inherent antibacterial action have been found to possess several unique characteristics, including signal–anchor–release (SAR) domains, N- or C-terminal polycationic tails, and a C-terminal amphipathic helix. The outer membrane is destabilized by molecules such as chelators (e.g., EDTA or organic acids), which provide endolysins access to the peptidoglycan [75]. The bacteriolytic range of action is extended beyond species specificity through the synthesis of chimeric enzymes (chimeolysins) by substituting or appending heterologous binding domains to the original structure of endolysins [29, 75, 82]. Moreover, effective hybrid enzymes that enhance the characteristics of endolysins when fused to a peptide or protein domain of non-endolysin origin (artilysins) have been designed to target Gram-negative bacteria. As a result, the phage T4 lysozyme was produced, conjugated with the pesticin toxin, and directed towards the FyuA protein, which is the primary virulence factor for Yersinia and Escherichia [115]. The N-terminus of endolysin was combined with an antimicrobial peptide that could penetrate the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria through a self-propelled uptake pathway to create a hybrid molecule that was effective against P. aeruginosa persister cells and multidrug-resistant strains [88]. By binding surface receptors with phage receptor-binding proteins (RBPs), innolysins help to destabilize the outer membrane, which causes endolysin permeabilization and peptidoglycan breakdown [75].

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Endolysins and possible mechanisms for increasing their activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Reproduced with permission from Sisson et al. [75], Current Opinion in Microbiology; published by Elsevier, 2024. AMP, antimicrobial resistance; OM, outer membrane; PG, peptidoglycan; RBP, receptor-binding protein.

Endolysins with a modular structure, which are specific for Gram-negative bacteria, are less common, yet they have greater efficiency and specificity than globular ones [116, 117]. Such enzymes are potential candidates for practical use in the fight against multidrug-resistant bacteria, whereas domain replacement will allow the creation of new enzymes with greater affinity for various pathogens. In addition, various native or chemically modified endolysins exhibit synergism with some antibiotics, which, in the future, will make it possible to reduce the required doses of antimicrobials to reduce their cytotoxicity [75, 118].

Different tactics are used by bacteriophages to expel daughter phage particles from infected bacterial cells. The first tactic is either gradually killing the bacteria or blossoming (gemmation) of the phage without destroying the host cell. A bacterial lipoprotein membrane covers the daughter phage particles during gemmation, but the type of cell membrane determines how the virions are released [28]. Members of the non-encapsulated phage family Plasmaviridae infect bacteria of the class Mollicutes, which lack a structurally formed cell wall, which allows the phages to separate from infected cells by budding. Acholeplasma phages L2 (MV-L2) and L172 use gemmation to release virions without causing fatal damage to the bacteria [28, 119]. In turn, phages L3, SpV3 and ai, living in the bacteria Acholeplasma laidlawii, Spiroplasma mirum, and Spiroplasma citri, respectively, use a mechanism similar to gemmation; however, unlike typical budding, it ends with a slow death of the host. In this instance, external membrane vesicles enclose one or more daughter virions as mature viruses build up in infected cells and are continuously discharged over several hours. The integrity of the host cell membrane is destroyed when a large number of phages are released in a short amount of time. Ultimately, unencapsulated virions are released when vesicles carrying viral particles are destroyed [28, 119].

Extrusion is the second type of daughter phage release that preserves the viability of bacterial cells. This process is characteristic of filamentous DNA-containing bacteriophages. These viruses develop intracellular DNA-binding proteins that attach to every copy of the replicating single-stranded phage DNA. Structural phage proteins are localized in the membrane of the infected bacterium, forming a channel through which the virus nucleic acid is displaced and a mature virion is formed [28, 120].

The third tactic, common for small-genome DNA and RNA viruses, is based on blocking of peptidoglycan production. These phages encode low-molecular-weight hydrophobic proteins, whose mode of action is comparable to that of antibiotics that inhibit the formation of murein, hence inducing host cell lysis. When E. coli bacteria are infected with the DNA virus phi X174, this process is used to release daughter virions. The phospho-MurNAc-pentapeptide translocase (MraY) enzyme, involved in peptidoglycan production, is inhibited by protein E, which is encoded by these phages [121]. The RNA-containing coliphages Q

Out of all the strategies that have been described, the fourth one is the most common. It involves employing lytic enzymes to quickly break down the host cell and release progeny virions. Mature phages must pass through multiple obstacles to exit the cell, which include the peptidoglycan layer, the inner cell membrane, and, in the case of Gram-negative bacteria, an extra outer cell membrane. Two other kinds of enzymes that bacteriophages can encode are called holins and endolysins, and they break down peptidoglycan and the inner membrane, respectively. It is also feasible for highly specialized phages that are particular to strains of Gram-negative bacteria to synthesize the spanin protein, which facilitates the entry of viruses through the outer membrane [28, 30].

Phage holin proteins regulate the ability of peptidoglycan hydrolases to enter the murein layer, thereby determining the duration of bacterial lysis. These proteins have a variety of structures and characteristics, but they all have one or more hydrophobic transmembrane domains (TMDs) and a positively charged, hydrophilic C-terminal region [123, 124, 125]. Holins fall into one of three classes based on the quantity of TMDs they have: Class I holins have three TMDs: the HolSMP protein, which is encoded by the SMP phage from S. suis, and the S protein, which is encoded by the

Holins can form large channels required for the passage of endolysins and local hydrolysis of peptidoglycans, or small pores involved in the activation of endolysins and depolymerization of the cell membrane, when they accumulate in the inner membrane until a certain critical concentration is reached [129, 130, 131]. Bacterial cell lysis systems can be classified into two main kinds on the basis of the type of holins and endolysins used: the canonical holing–endolysin system and the pinholin–SAR/SP endolysin system [28, 30].

Spanin proteins are characterized in bacteriophages

The periplasmic breadth is occupied by the i-spanin/o-spanin complex, which is the active complex of Rz and Rz1 that physically joins the inner and outer membranes. This combination is a negative regulator of spanin activity because a coating of peptidoglycan immobilizes its polypeptide chains [110, 134]. When endolysins break down peptidoglycan, the spanin complex undergoes conformational changes and lateral oligomerization, which destabilizes the outer membrane [133, 135]. Another form of spanin is the solitary protein monomer known as u-spanin, which functions independently. Certain phages that infect E. coli have been found to harbor functional homologues of the Rz/Rz1 complex, such as spanin gp11 [133, 136].

The lytic phage’s technique for releasing the viral progeny determines whether the bacteria undergo lysis or stay alive, although at varying rates. Holins, endolysins, and spanins are examples of enzymes that lyse bacteria cells and can be used as novel and promising pharmaceuticals to treat infectious disorders, especially those linked to multidrug resistance [137, 138].

Because of the frequent attacks by viruses (phages), bacteria have developed a variety of intricate active defense mechanisms that collectively constitute the prokaryotic “immune system” [139]. To fight off phage infection, bacteria have also evolved sophisticated antiphage signaling systems. Microbial genomes contain clusters of antiphage defense systems, which are frequently represented by multigene operons encoding proteins that can impede virion synthesis through a variety of ways. It has been proposed that genes of unknown function found in these genomic “defense islands” may also be engaged in antiphage defense mechanisms, which would group defense systems against phage infection [140, 141]. It is important to note that bacteria have a far more varied immune arsenal against bacteriophages than previously believed. Because of their adaptive advantages, individual microbes so frequently encode many defense systems, some of which are acquired by horizontal gene transfer [139]. One strain can access the encoded immune defense mechanisms of closely related strains by horizontal gene transfer, although one strain cannot contain all potential defense systems against phage invasion. Therefore, an efficient antiphage “immune system” is not just one that is encoded by a single bacterium’s genome, but rather a pangenome that consists of the entirety of all immunological mechanisms that the microorganism has access to for later use and horizontal transfer [142].

The primary antiphage defense mechanisms are as follows:

- restriction–modification (RM) systems, which target specific sequences of the invading phage [143];

- CRISPR-Cas, which provides acquired immunity by remembering previous phage attacks [144];

- abortive infection (Abi) systems, which cause cell death or metabolic arrest during infection [145];

- additional systems such as bacteriophage exclusion system (BREX) [146], prokaryotic argonauts (pAgos) [147], and the disarmament system, whose mechanism of action is still being investigated [148].

Different defense systems are encoded by different bacteria. About 40% of all sequenced bacterial genomes contain CRISPR-Cas systems [149, 150], RM systems are present in roughly 75% of prokaryotic genomes [151], and pAgos and BREX are expressed in roughly 10% of the bacteria that have been investigated [146, 147].

Unlike the CRISPR/Cas system, which requires prior exposure, most antiphage defense mechanisms protect against a broad variety of bacteriophages and are a type of “innate immunity”. CRISPR/Cas and restriction modification systems are the most well-studied antiphage systems; yet, numerous other antiphage genes and systems are presently the subject of ongoing research [139, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156].

The RM system is an enzymatic system of bacteria that destroys foreign DNA that has entered the cell. Its main function is to protect cells from foreign genetic material, bacteriophages, and plasmids. In most cases, RM systems contain two components: one that recognizes a specific sequence in the bacterial genome and modifies it (by methylation at adenine or cytosine bases) and another that recognizes unmodified motifs in the viral DNA and cleaves the nucleic acid.

The components of the RM system are characterized by two types of activity: methyltransferase (methylase) and endonuclease. Both individual proteins and one protein that combines both functions can be responsible for each of them. The RM system is specific to certain nucleotide sequences in DNA, called restriction sites. If certain nucleotides in a sequence are not methylated, a restriction endonuclease introduces a double-strand break into the DNA, and the biological role of the DNA molecule is disrupted. When only one of the DNA strands is methylated, cleavage does not occur; instead, methyltransferase adds methyl groups to the nucleotides of the second strand. This specificity of the RM system allows bacteria to selectively cleave foreign DNA without affecting their own. Normally, all DNA in a bacterial cell is either fully methylated or fully methylated on only one strand (immediately after replication). In contrast, foreign DNA is unmethylated and undergoes hydrolysis [7].

RM systems restrict the spread of mobile genetic elements among prokaryotes [157] and are classified into four categories (I–IV) [158, 159, 160, 161], with each type having a distinct target recognition process.

Because RM systems are so common and are thought of as the rudimentary immune systems of bacteria, their success as a defense mechanism against viral genome invasion is demonstrated by their variety and widespread representation in the prokaryotic kingdom. Recent studies [160, 161, 162, 163] have revealed their involvement in a number of biological functions that go beyond host defense, including pathogenicity and even regulating the rate at which bacteria evolve. The emergence of new adaptation mechanisms in prokaryotes is facilitated by RM systems, which raises the relative fitness of microorganisms within a population. As a result, new research has shown that RM systems are movable and can carry a variety of mobile genetic components. RM systems have an important role in plasmid transfer and influence plasmids over the course of the prokaryotes’ lengthy evolutionary history [162]. RM systems can be placed into an operon’s intergenic region or into a genome that has long or variable target duplication. The bacterial genome undergoes several rearrangements upon the introduction of RM systems, including amplification and inversion. Because of their mobility, the biological significance of RM systems is expanded beyond their protective role and suggests that they are involved in a variety of epigenetic events, such as those that promote prokaryotic evolution [163].

The CRISPR/Cas system of protection against viral infection is a form of adaptive “immunity” of prokaryotes and is a series of palindromic repeats, between which are short stretches of viral DNA (the so-called spacers), which serve as a template for the synthesis of guide RNA, which “tells” Cas restriction enzymes, which part of the genome needs to be cut out. Cas genes (“CRISPR-associated”) are an important part of this system. CRISPR loci typically consist of several non-contiguous direct repeats separated by regions of variable sequences called spacers and are often adjacent to cas genes. The entire system is designed to recognize a foreign nucleotide sequence and attach to it. After this, nuclease scissors (endonucleases included in Cas, or other means, e.g., RNases) are used, which cut the viral nucleic acid, as a result of which the virus is neutralized. In a bacterium that has survived a viral attack, new palindromic segments with viral spacers are added to the beginning of the CRISPR Gene cassette. Thus, a piece of DNA from the defeated enemy is inserted into the bacterial genome and will be passed on to the bacterium’s descendants. This is how “acquired immunity” is organized in bacteria, as well as archaea. It is constantly updated as bacterial cells encounter viral infections. On the basis of S. thermophilus, the existence of “acquired immunity” of prokaryotes by the CRISPR system was first proven and its mechanism was described [164]. Immune memory is achieved by acquiring short sequences of viral DNA incorporated into the bacterial genome (spacers). These sequences are transcribed, processed, and loaded into the CRISPR-Cas machinery, through which they interact with the viral DNA or RNA and prevent further infection. Type III CRISPR-Cas systems can also generate cyclic oligoadenylate (cOA) signaling molecules that promote lysis of the infected cell or cause it to stop dividing.

Although the biological roles of CRISPR loci have been proven, in silico spacer analyses have shown sequence homology with foreign elements, such as plasmids and bacteriophages [144].

Prokaryotes have been shown to have distinct CRISPR systems, which are categorized into a number of classes, kinds, and subtypes according to the distinctions in the functioning Cas elements and the target DNA or RNA recognition mechanism [165].

The study of cas genes made it possible to reconstruct the possible evolution of CRISPR systems, as described in [166].

It is very difficult for viruses to defeat CRISPR protection in a bacterial population, because different bacterial cells carry a different set of spacers. Therefore, even if a phage changes the sequences in one or two target regions (“protospacers”) and copes with one or two CRISPR RNAs or crRNAs, it cannot simultaneously change the entire set of “protospacer” regions. New spacers acquired from a different bacterium are thought to have the potential to trigger an autoimmune response in the CRISPR system. As a result, a formula for the likelihood of an autoimmune spacer appearing was developed [167], and it was found that this likelihood is relatively large (roughly 0.1%).

Two systems have been developed for Cas proteins: Specific High-Sensitivity Enzymatic ReporterUnLOCKing (SHERLOCK) for Cas13a, which has collateral RNase activity [168] and DNA endonuclease-targeted CRISPR trans reporter (DETECTR) for Cas12a, which nonspecifically cleaves DNA during complex formation with a guide and a target [169].

In prokaryotes, the CRISPR immunity molecular defense mechanism developed during evolution. These CRISPR molecular tools have absolutely great promise for use in microbiology and medicine, but they undoubtedly need more development before they can be used in clinical settings.

Abi systems, which induce programmed cell death, stop the spread of phage within the bacterial community. Before the phage can effectively finish its replication cycle, an infected cell experiences controlled death or quiescence owing to unsuccessful infection mechanisms. Abi preserves the local microbial community, which would otherwise vanish after multiple infection cycles, by stopping the flow of fresh virus particles into the environment [170]. The phenotype seen during phage infection and the defense system have been shown to have a complex interaction. The Abi phenotype needs to be viewed as a particular set of defense mechanisms and a characteristic of how particular phages and bacteria interact in particular situations [171].

Originally, the term “Abi” was used to refer to any instance of phage loss that occurred during infection [7]. Initially, this system was investigated in the model organisms Lactococcus lactis and E. coli along with their phages, but the general relevance and biological significance of this system to bacterial immunity were not well understood. Subsequently, Abi systems were described phenomenologically as particular genetic pathways that eliminate phages but do not stop infected bacteria from dying [170, 172]. By using this concept, both RM systems and, more recently, canonical clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) systems have been distinguished from these systems.

Infection interruption systems, which constitute the primary defense against phages, work by eradicating the cell as soon as it detects a phage infection. By eliminating the cell before the phage progeny reach maturity, these systems shield the bacterial community from harm and stop the phage from proliferating to nearby cells. In the usual form of Abi, signaling molecules are produced by systems that identify phage infection and trigger a cell-killing effector. Among these signaling systems are Thoeris, Pycsar, and CBASS.

Cyclic oligonucleotides are produced as a signaling molecule in CBASS systems by members of the CD-NTase family of enzymes, whereas cyclic UMP (cUMP) or cyclic CMP (cCMP) are produced in Pycsar systems. An isomer of cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR), a signaling molecule, is produced by thueris systems. When the effector module of CRISPR-Cas type III recognizes phage nucleic acids, it produces the signaling molecule CoA, which in turn activates the Abi response. Reverse transcriptase, effector proteins, and hybrid DNA–RNA (msDNA) are used by retrons systems to safeguard biological constituents. Retrons are activated when phage proteins inhibit these biological components, which results in cell death [7].

An instance of Abi that safeguards a whole population by causing individual infected cells to die is the sirtuin proteins, also known as silent information regulator 2 (SIR2), which are connected to prokaryotic defense mechanisms. Therefore, upon phage infection, the B. subtilis DSR2 protein, which has the N-terminal SIR2 domain, is activated, “sensing” the presence of the bacteriophage SPR tail proteins. This results in the depletion of NAD+ and the death of the bacteriophage-infected cell [173].

The toxin–antitoxin (TA) system, which consists of tiny loci that offer antiphage defense and are present in bacteria and archaea, is particularly noteworthy. There are numerous newly discovered TA systems that exhibit antiphage action. TA systems are believed to facilitate Abi, where the phage is eliminated and the bacterial population is safeguarded as a result of the host cell dying in response to the infection. This occurs because TA systems are naturally poisonous. The remarkable intricacy of phage–host interactions has been elucidated by the molecular processes through which phages activate TA systems, further supporting the notion that TA systems do not always perform traditional Abi [173].

Dy et al. [174] showed that AbiE systems are encoded by bicistronic operons and function through a non-interacting (type IV) bacteriostatic mechanism of TA. They also applied a new method of screening Abi systems as a tool for identifying and characterizing antiphage systems acting on the TA principle. The antitoxin AbiEi (transcription regulator) negatively autoregulates the abiE operon. The N-terminal region of AbiEi is necessary for the transcriptional repression of abiE, and the C-terminal portion of the protein is bifunctional and necessary for both transcriptional repression and toxin neutralization. A suspected nucleotidyl transferase (NTase) and member of the DNA polymerase

Fineran et al. [175] described ToxIN, a highly efficient two-gene Abi system from the phytopathogen Erwinia carotovora subspecies atroseptica. As a TA pair, the ToxIN Abi system inhibits bacterial growth while the tandemly repeated ToxI RNA antitoxin balances out the toxicity. With ramifications for the dynamics of phage–bacterial interactions, this is the first demonstration of an Abi system operating in a distinct bacterial species and of a novel mechanistic class of TA systems.

Phage infection activates a number of TA mechanisms, which cause cell death or growth arrest. In addition to the PrrC toxin, which is produced when phage proteins inhibit restriction enzymes, there are other Abi systems that stop cell growth through targeting tRNAs, creating membrane pores, phosphorylating cellular proteins, inducing premature cell lysis, and other mechanisms [7].

Numerous defense systems with a wide variety of mechanisms that are prevalent in bacterial genomes are the expression of the Abi approach. Phages, on the other hand, have evolved similarly varied defenses against bacterial Abi. The state of the art regarding bacterial defense through cell suicide has been summed up [176].

Some bacterial antiviral mechanisms directly inhibit phage DNA and RNA synthesis. Defense mechanisms create tiny compounds that “poison” the production of phage nucleic acids by acting through chemical defenses. Prokaryotic viperins (pVips) generate many kinds of RNA chain terminator molecules. It is likely that anthracyclines prevent phage infection by intercalating into the DNA of the phage and stopping DNA replication. In addition, some aminoglycoside antibiotics have recently been shown to inhibit viral replication through as yet unknown processes. An additional protective mechanism that causes inhibition of DNA replication is achieved through protective enzymes that deplete deoxynucleotides, such as dCTP deaminase and dGTPase. They are triggered upon infection and destroy one of the DNA nucleotides, which disrupts the phage’s ability to replicate its genome [7].

To stop the virus from spreading, prokaryotic argonauts (pAgo) also participate in the cleavage of phage DNA and RNA by nucleic acids [7]. In the cells of almost all prokaryotes, argonaut proteins are involved in the regulation of gene expression, the mobility of mobile genetic material, and viral defense. An endonuclease called argonaut protein cuts target RNA that is complementary to guide RNA [177]. The proteins in this family were initially identified as crucial components in the growth of Arabidopsis thaliana. The name of the whole protein family was derived from the appearance of an Arabidopsis thaliana protein mutant that resembled an Argonaut mollusk [178].

Argonaut proteins, which are far more diverse than eukaryotic proteins in the structure of the primary domains, the presence of extra domains, and related proteins encoded in the same operon, are found in around 10% of bacterial genera and 30% of archaeal genera [179]. The first detailed classification and bioinformatics characteristics of Argonaut prokaryotes were described in [180].

Prokaryotic argonauts can be divided into two large groups:

- long argonauts (long), in which there are four domains characteristic of eukaryotic argonauts;

- short argonauts (short), in which the N-terminal and PAZ domains are absent.

Most of the prokaryotic argonauts belong to inactive proteins that lack the catalytic tetrad of amino acids in the P-element induced wimpy testis (PIWI) domain: these are all short argonauts, long argonauts of group B (longB) and a small part of long argonauts of group A (longA). All catalytically active argonauts belong to the longA group, one of the evolutionary branches of which includes all eukaryotic proteins [177, 180].

The first bacterial argonauts to be studied in detail were proteins from the bacteria Rhodobacter sphaeroides (RsAgo) [181] and Thermus thermophilus (TtAgo) [147]. RsAgo belongs to the longB group and does not exhibit catalytic activity; however, it has an affinity for foreign DNA and promotes the degradation of plasmids [181]. TtAgo belongs to the longA group of long active argonauts. Like most active bacterial argonauts, it binds short DNA guides and cleaves target DNA, thereby reducing the transformation efficiency of T. thermophilus [147].

Most research has been focused on long active argonauts and to date, several dozen catalytically active bacterial argonauts have been biochemically characterized in detail, the data on which have been described in detail [178, 182].

Unique minor groups of active bacterial argonauts have been discovered that, with the help of guide RNA, cut target DNA and vice versa [183, 184], while most of the studied active argonauts have preferences for guide DNA and target DNA.

Depending on the argonauts and the strains studied, DNA guides originate uniformly from all regions of the genome [147, 185], or originate from certain regions of the genome: replication termination sites, as well as sites of double-strand breaks and regions of homology with plasmid DNA [186, 187]. An important discovery was the discovery of the participation of prokaryotic argonauts in protecting cells from bacteriophages, which is likely their main function in bacterial cells [186].

Along with Cas proteins, argonauts are used widely in molecular biology, because with the help of certain guides they can be directed to a specific target. In particular, argonauts can be used to detect nucleic acids, including short RNAs, to determine the structure of RNA, RNA modifications, rare mutations in DNA for cloning sequences, introducing modifications into bacterial genomes, etc. [182, 188, 189, 190].

Compared with research on active argonauts, less research has been done on inactive argonauts. One operon in long inactive argonauts has partner proteins that fall into multiple categories: nucleases, proteins containing SIR2 domains, transmembrane domain-containing proteins, and proteins with unknown activities [177].

Bacteria can continue to defend themselves against bacteriophages because of the diversity of pAgos. It is still unknown what the full-length, catalytically inactive argonauts longB pAgos do or how they do it. For dormant argonauts to operate, a protein partner must be present [191]. A unique RNA that is directed towards the target DNA activates the longB pAgo nuclease system (BPAN), which recognizes and degrades it in vitro. When an invasive plasmid is detected in vivo, this mechanism facilitates the degradation of genomic DNA, leading to the death of infected cells and the depletion of the invader from the cell population. The BPAN system provides bacterial immunoprotection through Abi infection. A similar defense strategy is used by other longB pAgos equipped with distinct associated proteins.

Middle (MID) and PIWI are the two domains that comprise short argonauts. Usually, a partner protein with an effector domain and an analog of piwi-argonaute-zwille (PAZ) – APAZ domain is encoded in one operon alongside them. The formation of a complex with the argonaut protein requires APAZ, which is structurally similar to the N-terminal region of long argonauts but not identical to the PAZ domain of long argonauts [177, 180].

Among the short argonauts, the most studied protein is from the bacteria Geobacter sulfurreducens, which is encoded in the same operon with the SIR2 protein that binds NAD+. It was shown that these proteins are synthesized by one complex, called SPARSA, and their expression in the heterologous system of E. coli bacteria protects bacterial cells from viral infection of two of the six tested bacteriophages of different families, and also leads to cell death in the presence of certain plasmids. When the guide-target duplex binds, the SIR2 domain is activated, which leads to NAD+ depletion and cell death. This mechanism of NAD+ depletion in bacterial cells was shown in vitro [192].

Researchers have looked into the mode of action of the short argonaut of the bacterium Novosphingopyxis baekryungensis (NbaAgo) (called short prokaryotic argonaute and DNase/RNase-APAZ (SPARDA)) [193], which functions in complex with the PD-(D/E)XK family nuclease. NbaAgo combines with the encoded effector nuclease to produce a heterodimeric complex of SPARDA. It was shown that SPARDA’s nuclease activity is released upon RNA-guided identification of target DNA, resulting in indiscriminate collateral cleavage of both DNA and RNA. When plasmid transformation or phage infection occurs, SPARDA is activated and causes cell death, which shields the bacterial community from “invaders”. Through Abi, the expression of SPARDA in E. coli shields them from some bacteriophages and plasmids.

Highly sensitive identification of particular DNA targets is made possible by SPARDA’s off-target action. By using a distinct range of nuclease activity, SPARDA broadens the array of prokaryotic immune systems that can cause cellular death, opening up new avenues for biotechnology [193]. Argonaut proteins are potentially useful for genome editing and have already found use in biotechnology for targeted cleavage and nucleic acid detection [182].

Thus, the studies [182, 183, 184, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193] of argonauts and associated partner proteins is a relevant direction both for understanding the diversity of bacterial defense systems and the evolution of RNA interference mechanisms, and for creating new molecular biological tools.

Principles for using bacteriophages to treat bacterial illnesses in humans (phage therapy) were developed possible with the discovery of bacteriophages. The high specificity of phages, which allows them to contact and infect only particular bacteria while sparing other bacteria or other organisms’ cell lines, is a benefit of phage therapy. As an alternative to antibiotics, bacteriophages can be used to fight illnesses and eradicate harmful bacteria.

The use of bacteriophages that cause bacterial lysis as an alternative treatment for infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens is gaining increasing attention for phage therapy. The high specificity of bacteriophages to bacterial hosts requires the availability of a wide variety of characterized bacteriophages with different infectious spectrums to increase the efficiency of phage cocktail use. In modern medical scenarios, various mixtures of species-specific bacteriophages in phage cocktails with antibiotics, endolysins and depolymerases are used to increase the effectiveness of treatment. In particular, study have been published on the development of phage therapy to combat pathogens of the ESKAPE group (which includes six nosocomial pathogens that exhibit multidrug resistance and virulence: Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) and the use of bacteriophages in medical practice [194].

The use of phage therapy to treat enterococcal infections has shown promising results. Thus, experiments in vivo on a model of Enterococcus faecalis infection during infection of the great wax moth Galleria mellonella showed that the introduction of the vB_EfaH_163 bacteriophage into larvae infected with the E. faecalis VRE-13 strain made it possible to increase their survival by 20% relative to the infected group (with the introduction of a pathogen suspension with a concentration of 106 colony-forming unit/ml (CFU/mL)), which was not injected with the bacteriophage preparation [195]. In the group that was administered the cocktail prophylactically (i.e., before infection with E. faecium), survival was 6.5 times higher than in larvae that were injected with VREfm alone [196]. In addition, when using bacteriophages, sensitization of Enterococcus bacteria to antibiotics has been shown, which significantly increases the effectiveness of combination antimicrobial therapy [197].

Under natural conditions of development of phage infection, the activity of bacteriolytic enzymes is limited by the need to maintain the viability of the host cell during the delivery of viral DNA (in the case of virion-associated lysins), as well as to prevent premature lysis of the bacterium before the end of the viral replication cycle (for endolysins). On the other hand, the peptidoglycan-degrading activity of an exogenous preparation of pure enzymes frequently causes the fast osmotic lysis and death of bacterial cells upon their addition. These characteristics make phage lytic enzymes ideal antibacterial medications, which served as the inspiration for the early 21st-century concept of “enzybiotics” [198]. Their advantages include great specificity, nearly total absence of mechanisms for bacterial resistance to build resistance to them, and very high activity linked to their direct method of action, which results in the instantaneous death of the target cell [199].

For more than 20 years, endolysins from bacteriophages of Gram-positive bacteria have been intensely studied in vitro, as well as in animal infection models, in which they show promising results [200]. Endolysins from bacteriophages of Gram-negative bacteria were initially overlooked by scientists owing to the outer membrane that prevents the enzyme from reaching the peptidoglycan, but over the past 10 years there has been a rapid development of methods and techniques that allow the use of these enzymes as antibacterial agents [112]. Virion-associated lysins also received little attention during the early stages of enzybiotic development, but in recent years their popularity has increased owing to the advantages they have over endolysins [33]. In particular, they have a much higher specific bacteriolytic activity towards living bacteria.

Cases of successful use of phage therapy, for example, against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteria causing abdominal infections have been described [201]. There is evidence of the effective use of phage therapy (“Piobacteriophage”, Eliava) for intractable enterococcal infections of the musculoskeletal system [202], as well as for infections that occur as a complication after hip replacement (“Intestifag”, Eliava) [203]. In addition, phage preparations are used in the treatment of a number of staphylococcal infections [204] and diseases caused by E. coli bacteria [205].

An important direction for the treatment of infections is the use not of bacteriophages themselves, but of their enzymes. For example, a drug (“Exebacase”) based on phage peptidoglycan-degrading enzymes, intended for the treatment of chronic skin infections caused by methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus, is in stage III clinical trials. Additionally, three drugs for the treatment of staphylococcal infections of the skin and respiratory tract (“Staphefekt SA.100”, “SAL200” and “P128”) are undergoing stage II clinical trials. At the same time, “Staphefekt SA.100” is already commercially available in some European countries. In addition, more than 30 phage peptidoglycan-degrading enzymes are currently undergoing preclinical testing, based on which it is planned to develop dosage forms to combat pathogens such as S. aureus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. pneumoniae and B. anthracis [206].

Phage preparations and their enzymes can be successfully used in medicine for phage therapy, but they are also very promising for other industries. In contrast to medical applications, the use of phage enzymes in the food industry and agriculture has long received little attention. This fact is due to the high cost of recombinant enzymes, often unsuitable environmental conditions for their effective operation (pH, ionic strength, presence of inactivating proteases), as well as the difficulty of enzyme access to target bacteria owing to the characteristics of many food and agricultural products [207]. However, over the past 10 years, preparations based on phage enzymes have found widespread use as biosafe and taste-free antimicrobial additives for milk, meat, cheese, and vegetables, where they are effective in the fight against microorganisms such as S. aureus and Listeria monocytogenes [208].

Over billions of years, prokaryotes have been subjected to intense evolutionary pressure from phages, which has led to significant genomic rearrangements. These modifications have led to the development of effective phage defense mechanisms by bacteria. Some mechanisms, the CRISPR-Cas and RM systems, specifically target the nucleic acids of phages. Other bacterial defense mechanisms, such as argonaut proteins and genetic systems that cause cell death or growth arrest prior to the phage replication cycle, have been documented in phage-host interactions. One such mechanism is Abi. Phages will undoubtedly be used more widely in a variety of medical specialties as a result of more in-depth research into the mechanics behind the interaction between bacterial cells and phages.

Preparations of phage enzymes have not yet found widespread use in industrial agriculture as biological control agents (largely owing to their high cost), however, in the near future, optimization of production will make them a promising source of biocontrol agents, at least for processing inoculation material.

Without examining every enzyme involved in the interaction between phages and bacteria and evaluating it, bacteriophages cannot be used in practical applications. Numerous studies [170, 171, 172, 173, 182, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193] conducted in the past few years have uncovered a huge variety of bacterial antiphage defense systems; nevertheless, the mechanisms of these systems are not fully understood yet. Understanding the interactions between bacteriophage proteins and bacterial proteins is important for efficient infection of the host cell. Future studies are expected to shed more light on the mechanism of action of all new prokaryotic antiphage systems.

OIG – Conceptualization and Design, Project Administration, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing. SSE – Formal Analysis, Software, Resources, Visualization, Writing–original draft. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 24-24-00309).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.