1 Department of Pediatrics, Affiliated Hospital to Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, 130021 Changchun, Jilin, China

2 Department of Pediatrics, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Changchun University of Chinese Medicine, 130117 Changchun, Jilin, China

Abstract

Pediatric asthma is a common respiratory condition in children, characterized by a complex interplay of environmental and genetic factors. Evidence shows that the airways of stimulated asthmatic patients have increased oxidative stress, but the exact mechanisms through which this stress contributes to asthma progression are not fully understood. Oxidative stress originates from inflammatory cells in the airways, producing significant amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). External factors such as cigarette smoke, particulate matter, and atmospheric pollutants also contribute to ROS and RNS levels. The accumulation of these reactive species disrupts the cellular redox balance, leading to heightened oxidative stress, which activates cellular signaling pathways and modulates the release of inflammatory factors, worsening asthma inflammation. Therefore, understanding the sources and impacts of oxidative stress in pediatric asthma is crucial to developing antioxidant-based treatments. This review examines the sources of oxidative stress in children with asthma, the role of oxidative stress in asthma development, and the potential of antioxidants as a therapeutic strategy for pediatric asthma.

Keywords

- pediatric asthma

- oxidative stress

- inflammatory

- antioxidant

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by recurrent coughing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness [1]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [2], nearly 25 million asthma people in the US had asthma in 2021, including 4.6 million children under 18 years old. Studies have shown that many children with clinically well-controlled asthma still exhibit persistent bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Severe asthma in children poses a significant health burden, as it often leads to medication-related side effects and impaired quality of life [3, 4, 5]. Asthma that begins in early life and persists into school age usually continues into adulthood, affecting lung function and increasing the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [6].

The primary pathological features of asthma include airway inflammation, hyperresponsiveness (exaggerated response to exercise, air pollutants, allergens, etc., leading to airway spasms and narrowing), remodeling (thickening of the airway wall and hypertrophy of smooth muscles), and airway obstruction due to excessive mucus secretion. Asthma is diverse and challenging to categorize: It can be classified based on phenotypes (clinical observations) and endotypes (etiological observations) [7]. Research indicates that one phenotype corresponds to multiple endotypes [8]. Common phenotypes include allergen-induced asthma, non-allergic asthma, infection-exacerbated asthma, aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease, and exercise-induced asthma [9].

The incidence of adult-onset asthma is similar to childhood asthma. However, adult-onset asthma tends to be more severe and progressive, whereas childhood asthma is generally milder and often goes into remission [10]. Both types share many common triggers, and evidence suggests that asthma results from the interaction of environmental factors with genetic and atopic predispositions. Most childhood-onset asthma cases exhibit an allergic phenotype, whereas adult-onset asthma is predominantly non-allergic [11]. Asthma during adolescence is more common in males, likely due to relatively poorer lung development in male fetuses. [12]. A study of 3622 asthma cases indicated that the rise in asthma prevalence between 1964 and 1983 was primarily driven by an increased incidence among children aged 1 to 14 years [13]. Clinical and lung function outcomes in adulthood are closely linked to the severity of childhood asthma [14], highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and treatment. Environmental factors, including mode of birth delivery, antibiotic use, exposure to tobacco smoke, and an industrialized lifestyle, significantly contribute to childhood asthma exacerbation [15]. The inflammatory phenotype of asthma differs in adults and children, with neutrophilic inflammation predominating in adults and eosinophil inflammation in children [16]. Research indicates that children with allergic sensitization showed significant lung function impairment, suggesting a crucial relationship between allergic reactions and childhood asthma. [17]. Allergy plays a key role in the early development of childhood asthma and is closely related to allergic inflammation cascade reactions [18].

Oxidative environments leading to redox imbalance are closely related to the asthma pathophysiology of asthma, causing airway constriction, hyper-reactivity, and airway remodeling [19]. Pulmonary cells produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), contributing to oxidative stress. Additionally, reactive substances inhaled from the environment elevate oxidative stress, which disrupts the cellular redox balance, exacerbating inflammation and intensifying asthma symptoms in children. This article reviews the generation of oxidative stress in pediatric asthma and explores how elevated oxidative stress leads to cellular inflammation. Furthermore, it aims to promote research on the relationship between oxidative stress and pediatric asthma progression, facilitating the development of antioxidant treatments.

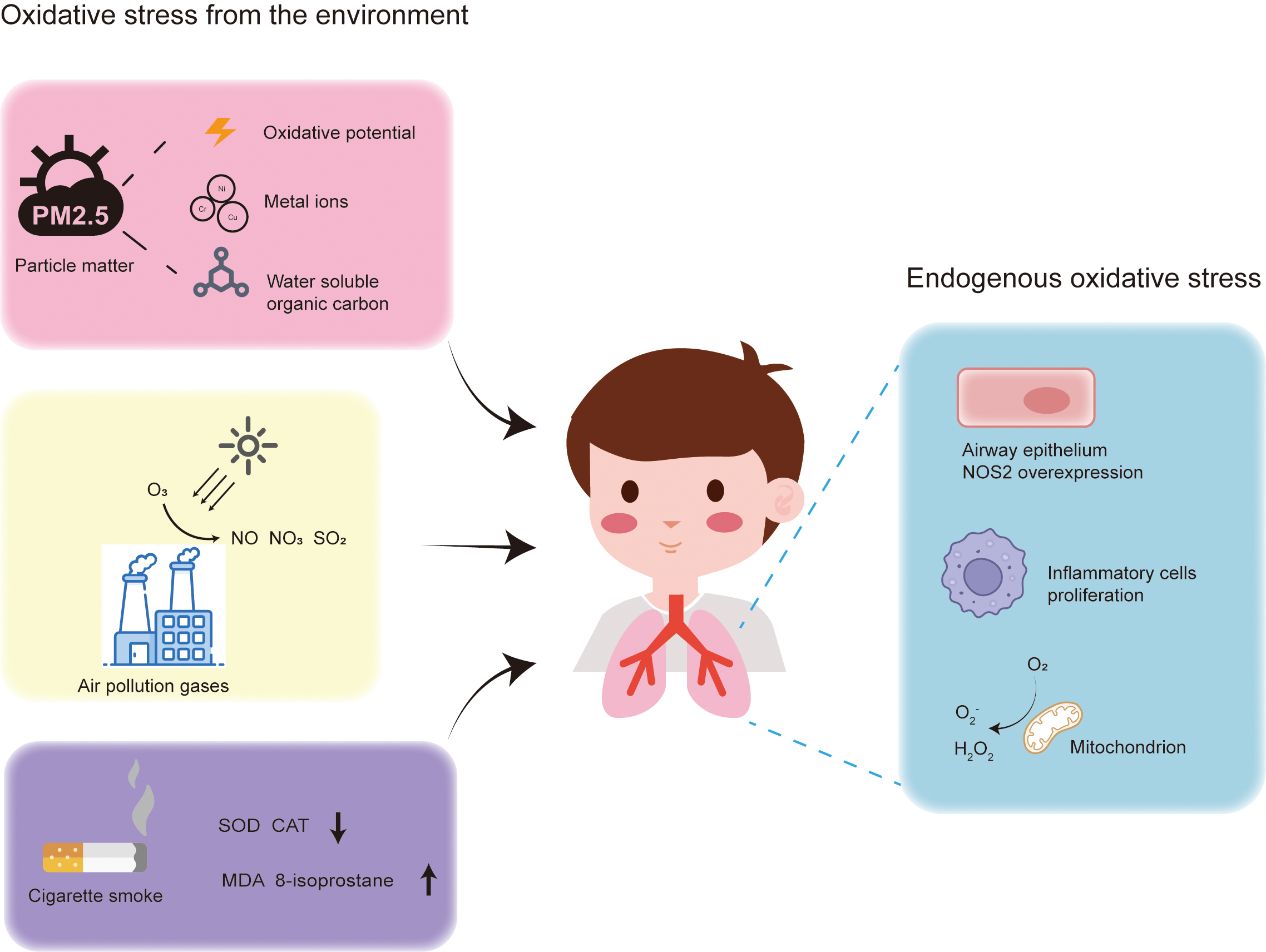

Many studies have demonstrated that elevated oxidative stress levels exacerbate the risk of childhood asthma [20, 21, 22]. Respiratory inflammation is a major source of oxidative stress, with research indicating a significant increase in the number of inflammatory cells and the production of ROS in asthma patients compared to the control [23]. As shown in Fig. 1, oxidative stress can be categorized into endogenous and exogenous, with endogenous oxidative stress resulting from ROS and RNS [24] and exogenous oxidative stress originating from air pollutants, particulate matter, and cigarette smoke [25]. The antioxidant system in lung cells responds to increased oxidative stress to maintain redox balance. However, once this homeostasis is disrupted, excessive oxidative stress can damage biological molecules such as lipids, proteins, and DNA, impairing cellular functions [26]. Elevated oxidative stress also activates intracellular inflammatory pathways, exacerbating the release of proinflammatory cytokines and enhancing the inflammatory response [27].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Sources of oxidative stress in the lungs of asthma patients. Exogenous oxidative stress originates from gaseous pollutants, particulate matter, and cigarette smoke. Endogenous oxidative stress arises from reactive oxygen species produced by mitochondria, overexpression of NOS2, and proliferation of inflammatory cells. NOS2, nitric oxide synthase 2; SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase; MDA, malondialdehyde.

In summary, increased oxidative stress impairs lung cell function and is closely associated with the development of inflammation. Lung function and pulmonary inflammation are critical to the progression of childhood asthma. Therefore, this section focuses on the production of endogenous and exogenous oxidative stress in the lungs and its impact on pediatric asthma.

Oxidative stress arises from an imbalance between the production of ROS and the capacity of the antioxidant system. In the lungs, ROS primarily originate from inflammatory cells such as macrophages, eosinophils, and neutrophils, as well as bronchial epithelial cells, which produce dual oxidase 1 [28]. Additionally, myofibroblasts, influenced by terminal end proteins, generate ROS by increasing the expression of transforming growth factor-beta [29].

ROS includes superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals. Within cells, ROS generation is primarily derived from mitochondria. While mitochondria supply energy through the electron transport chain, they also produce a significant amount of superoxide anion. Mitochondrial superoxide anion production relies on the reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide/ the oxidized form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH/NAD+) and the ubiquinol/ubiquinone (UQH2/UQ) isopotential pools [30]. The former involves flavin-dependent dehydrogenases that oxidize or reduce nicotinamide, generating the superoxide anion. The latter involves enzymes that oxidize mitochondrial coenzyme Q, producing superoxide anion through coenzyme Q oxidation. The mitochondrial-generated superoxide anion is unstable and interacts with NADH oxidoreductase and, to a lesser extent, with hydrogen peroxide, significantly decreasing its activity [31, 32]. To prevent sustained damage, the superoxide anion is catalyzed by superoxide dismutase (SOD) into hydrogen peroxide [33], which is then reduced to hydroxyl radicals in the presence of ferrous ions. Hydroxyl radicals are highly reactive, causing immediate oxidative damage to surrounding proteins or lipids [34]. Eosinophil peroxidase catalyzes the reaction of hydrogen peroxide with chloride, bromide, and thiocyanate to produce hypohalous acids, exacerbating tissue oxidative damage under inflammatory conditions and promoting the onset of asthma [35].

Numerous research findings link the rise in ROS with increased levels of inflammatory cells in asthma patients. For instance, Sanders et al. [36] observed a notable increase in the eosinophil count and superoxide anion production in asthmatic patients exposed to antigens. Subsequent experiments involving density gradient centrifugation confirmed that the heightened production of ROS was primarily attributed to the expanded eosinophil population, suggesting a key role of superoxide anions in airway damage associated with allergic inflammation [36]. Furthermore, 48 hours after antigen stimulation, there was a notable increase in alveolar macrophages, exacerbating superoxide anion production [37]. Asthma severity is directly associated with increased ROS. Hoshino et al. [38] reported a significant increase in inflammatory cells in the airways of asthmatic patients compared to healthy individuals, with these cells releasing a substantial amount of ROS and RNS. In mice asthma models, Human thioredoxin 1 (TRX1), a peptide with reducing properties, significantly attenuates airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammatory cell proliferation, thereby reducing pulmonary inflammation and alleviating airway remodeling [38].

In addition to ROS, RNS also contributes to oxidative stress in the lungs. The primary RNS generated in the lungs is nitric oxide (•NO), produced through the oxidative reaction of L-arginine to L-citrulline, involving NO synthase (NOS) [39]. There are three main types of NOS: Neuronal NOS (NOS1), inducible NOS (NOS2), and endothelial NOS (NOS3) [40]. NOS1 and NOS3 are constitutively expressed in neurons and endothelial cells, respectively, and are activated calcium ions that bind to calmodulin [41]. NOS2 is typically induced under conditions involving cytokines and proinflammatory factors and is also calcium-dependent [42, 43]. NOS2 is expressed in lung epithelial cells of both normal individuals and asthma patients, with higher expression levels in asthma patients. Studies indicate that higher levels of peroxynitrite, a potent oxidant formed by the reaction of free NO radicals and superoxide, are detected in the airway epithelial cells of asthma patients [44, 45], suggesting a curial role for NOS2 in promoting airway epithelial cell damage. All three NOS isoforms are present in the lungs, predominantly in lung epithelial cells, endothelial cells, neurons, eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells [46].

Asthma is closely related to the production of •NO in the airways, with levels of •NO in asthmatic patients exceeding those in healthy individuals [47]. This elevation is attributed to increased transcription of NOS2 in airway epithelial cells and an increase in L-arginine, the substrate for NOS [42]. •NO exists in a dynamic metabolic balance in the airways, with different metabolic products determining its role in asthma. For example, the reaction of •NO with thiols generates S-nitrosothiols, which have bronchodilatory and antibacterial effects, meaning low-dose inhaled •NO gas can be used to treat asthmatic patients [48]. However, •NO can also react with superoxide to generate cytotoxic peroxynitrite and nitrosamines and with nucleotides, proteins, and lipids, disrupting their function [49]. Upon antigen stimulation, the nitrate (NO3-) content in the airways of asthmatic patients significantly increases, suggesting that in the early stages of asthmatic response, •NO exerts a toxic effect, forming nitrate. Subsequently, the S-nitrosothiol levels rise over time, indicating that in the later stages of asthma, •NO may mitigate its toxic effects by generating S-nitrosothiols [50].

Direct exposure of the lungs to the external environment makes them vulnerable to oxidative substances in air pollutants, such as oxidizing gases and particulate matter. Children with incomplete lung development are particularly susceptible to lung damage from the pollutants [51].

One significant gaseous pollutant is ozone, a potent oxidant that exacerbates inflammatory responses [20]. Ozone primarily affects pulmonary tissues, and even trace amounts can worsen the symptoms of pediatric asthma patients [52, 53]. Ozone is a photochemical gaseous pollutant generated from volatile organic compounds in the presence of nitrogen oxides and sunlight [54]. It can react with nitric acid in fossil fuels, producing NO and NO2, which, although less oxidizing than ozone, still induce mild airway inflammation [20]. Ozone can also react with unsaturated fatty acids and cell membranes in airway epithelial cells, producing lipid ozonation products (LOPs). Increasing the LOP concentration activates phosphorylated enzymes in airway epithelial cells, promoting lung inflammation [55].

Research has shown that inhaling ozone damages the lungs [52, 54]. In areas with low ozone concentrations, outdoor exposure and physical activity do not significantly increase the risk of childhood asthma. However, in regions with high ozone concentrations, prolonged outdoor exposure and physical activity significantly exacerbate the likelihood of childhood asthma, suggesting ozone has a role in promoting asthma development [56]. Ozone increases airway hyperresponsiveness and neutrophil count in allergic asthma patients, an effect worsened by allergens such as dust mites, ragweed, and Aspergillus fumigatus (DRA). This exacerbation likely results from DRA disrupting the immune response and antioxidant systems, weakening the immune response and intensifying ozone’s proinflammatory effect. Thus, ozone contributes to lung injury by disrupting the body’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory defense systems [57].

Particle matter (PM) pollution significantly contributes to atmospheric pollution, particularly particles with a diameter of less than 10 micrometers (PM10), which negatively impact health and increase the incidence and mortality of respiratory diseases [58]. The specific components of PM that are detrimental to health are not fully understood, but the health effects are due to various active components [59]. One important characteristic of PM is its oxidative potential, which has received increasing attention. Research by Strak et al. [60] suggests that the oxidative potential of PM2.5 (particles with a diameter less than 2.5 micrometers) is more strongly correlated with health than its mass. Common methods for characterizing the oxidative potential of PM include the macrophage-based method [61], ascorbic acid, dithiothreitol (DTT), and glutathione assays [62]. The DTT method is widely used to characterize the relationship between oxidative stress and PM-induced inflammation [63, 64]. Epidemiological analysis by Bates et al. [65] found that biomass combustion contributed to 45% of the total DTT activity during the study period, and DTT activity showed a significant link with asthma hospitalization compared to PM2.5. The study by Scott Weichenthal et al. [66] also indicated that oxidative stress correlates with lung cancer mortality more strongly than the mass concentration of PM2.5. Notably, different methods of characterizing oxidative stress show varying correlations with lung cancer mortality. Oxidative stress characterized by glutathione activity demonstrated a clear correlation, whereas that characterized by ascorbic acid activity did not [66]. The oxidative stress burden also varies with particle size; smaller PM fractions exhibit stronger ROS activity, possibly due to their higher content of transition metal ions (such as Ni, Cr, Cu) and water-soluble organic compounds involved in redox reactions [67, 68].

Cigarette smoke contains over a thousand chemical compounds, most of which are detrimental to the respiratory system. Studies show that maternal smoking exposes fetuses or newborns to nicotine, which adversely affects lung development and accelerates the genetic aging process. This makes offspring more susceptible to lung diseases and accelerates pulmonary aging [69, 70]. Nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in developing beta cells, increasing intracellular ROS and causing significant mitochondrial protein and beta cell apoptosis in newborns [71]. Research on lactating mice indicates that maternal nicotine exposure reduces the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and catalase (CAT), elevates malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, and induces pulmonary interstitial inflammation [72]. Numerous studies also show a significant increase in oxidative stress after smoking [73, 74, 75]. For example, 8-isoprostane, a lipid peroxidation product, is found to be 2.2 times higher in the breath condensate of smokers compared to non-smokers [76]. Exhaled hydrogen peroxide levels increase significantly half an hour after smoking [77]. Exposure of rat tracheal segments to cigarette smoke results in noticeable epithelial cell damage, which is alleviated by superoxide dismutase. The hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anions levels in tracheal segments significantly correlate with cigarette smoke exposure [78]. Additionally, endothelial cells in smokers show activation of the pentose phosphate pathway and increased cellular glutathione secretion, indicating significant oxidative stress [79].

Exposure to indoor allergens can trigger early allergic reactions in children, leading to the development of childhood asthma [80]. Early-life contact with allergens such as cat and dust mite allergens significantly increases the risk of sensitization by the age of four, with cat allergens particularly linked to persistent wheezing [81]. Study indicates that children aged 5–17 exposed to indoor allergens (e.g., dust mites, cat, and dog allergens) have a higher asthma incidence than the control group; however, the association between dog allergens and asthma is weaker than that of cat allergens [82]. Custovic et al. [83] found a significant association between cat ownership and sensitization to cats in infants, whereas dog ownership was not linked to sensitization to either cats or dogs. This suggests a difference in how allergens from various pets relate to childhood asthma.

Pet-derived allergens, such as the cat allergen Fel d 1, can provoke severe allergic reactions [84]. Fel d 1 significantly enhances the signaling of innate immune receptors Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and TLR2 through interactions with the TLR4 agonist, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [85]. Moreover, TLR4 activation is widely reported to be involved in the production of ROS, which contributes to oxidative stress and inflammation [86, 87].

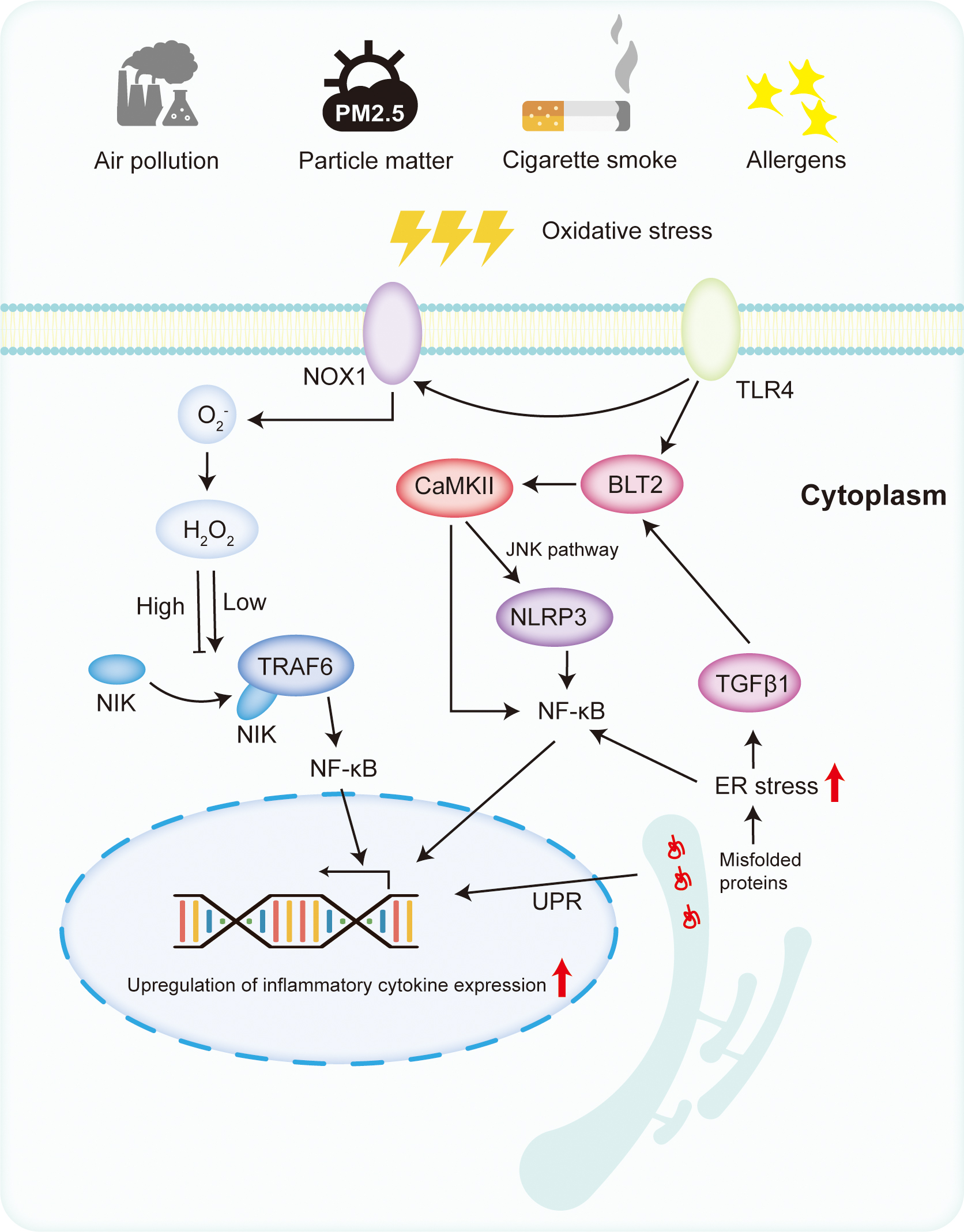

Oxidative stress plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of asthma by promoting inflammation, airway remodeling, and airway hyperresponsiveness. Various environmental cytokines bind to cell membrane receptors, activating downstream signaling pathways that increase ROS and RNS, thereby facilitating inflammation. As shown in Fig. 2, this process involves the activation of transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The mechanism of oxidative stress in pediatric asthma. Under the stimulation of oxidative stress and antigens, TLRs are activated. Activated TLRs can increase the production of ROS by stimulating NOX1. At low concentrations, ROS can activate NF-

Inflammatory mediators play a pivotal role in inflammation by activating inflammatory cells. Structural airway cells, such as epithelial cells, also release inflammatory mediators [88], perpetuating airway inflammation by inducing the expression of downstream genes; NF-

Studies suggest an association between NF-

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are pattern recognition receptors that recognize pathogen-associated and damage-associated molecular patterns, activating immune cells and proinflammatory cytokines [97]. Ten TLR family members (TLR1-10) have been identified in humans, [98] each playing various roles in the development of childhood asthma.

Studies in mice models show that low-dose treatment with TLR agonists increases neutrophils, while high TLR7 and TLR9 doses significantly reduce eosinophil levels. Conversely, TLR2 and TLR4 agonists increase airway eosinophils and release inflammatory cytokines [99]. TLR2 and TLR4 activation are closely related to ROS and RNS [100, 101]. For instance, interleukin 6 (IL-6) expression and airway hyperresponsiveness induced by ozone are suppressed in mice lacking TLR2 or TLR4 genes [87], indicating their role in promoting inflammation.

In the lung epithelium, TLR4-mediated inflammatory responses prevail over TLR2. Allergens activate TLR4 on epithelial cells, catalyzing inflammation [102]. Elevated TLR4 expression is observed in mice exposed to ozone and ozone-sensitive mice [103]. Activated TLR4 stimulates ROS production via the MyD88-B4 receptor 2 (BLT2) pathway and NADPH oxidase 1, activating NF-

The ER serves as critical for protein synthesis and secretion in cells. ER stress occurs when it is overloaded with unfolded proteins, disrupting the redox balance. Using RNA sequencing, researchers discovered that airway epithelial cells influenced by IL-13 exhibit significant ER stress and apoptosis characteristics, mirroring the transcriptional features of nasal airway epithelium in children with high and low type 2 cytokine asthma [109]. Orosomucoid 1-like protein 3 (ORMDL3), a protein targeting the ER, induces ER stress. Subsequently, ORMDL3 overexpression in mice leads to airway remodeling and increased airway hyperreactivity [110]. Children with upregulated ORMDL3 gene expression have a significantly increased risk of asthma [111]. Elevated ER stress markers were found in the ovalbumin and LPS-induced bronchial mice model and in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of asthma patients [112]. Treatment with 4-phenyl butyric acid, a chemical chaperone that alleviates ER stress, significantly downregulated inflammatory cytokines, TLR4 receptors, and NF-

Environmental ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide, exacerbate ER stress and cellular inflammation [113]. Proteins in the ER form disulfide bonds with the help of protein disulfide isomerase and ER oxidoreductase, releasing hydrogen peroxide and increasing oxidative stress [114]. This disrupts the ER’s redox balance, inactivating disulfide isomerase and preventing proper protein folding, leading to ER stress [115, 116], which activates the unfolded protein response, triggering downstream inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and pancreatic ER kinase (PERK) signaling pathways [117]. Inhibitors of inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) could suppress transforming growth factor beta (TGF

Cells respond to excessive oxidative stress by regulating gene expression to counteract the damage. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a key transcription factor in the cellular response to oxidative stress and in maintaining antioxidant defenses [122]. Nrf2 consists of six functional domains, Nrf2 – ECH homology (Neh)1–Neh6. Under normal physiological conditions, the Neh2 domain of Nrf2 binds to Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), retaining Nrf2 in the cytoplasm and promoting its degradation through ubiquitination. When oxidative stress occurs, Keap1 releases Nrf2, which then translocates into the nucleus. In the nucleus, Nrf2 forms heterodimers with Maf proteins via its Neh1 domain and binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs), activating antioxidant genes such as SOD, CAT, and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) [123]. SOD catalyzes the conversion of superoxide anions into hydrogen peroxide, which CAT then converts to water, thus eliminating ROS [124]. HO-1, a phase II detoxifying enzyme, can bind to NADPH and cytochrome P450, regulating various cellular activities, including oxidative stress [125]. HO-1 also interacts with Nrf2, stabilizing and enhancing its antioxidant capacity [126].

Activation of the Nrf2 pathway alleviates airway hyperresponsiveness. Studies have shown that the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway significantly improves PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell damage and reduces ROS generation, thereby inhibiting cell apoptosis; for instance, Shan et al. [127] found that activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway mitigated PM2.5-induced damage in bronchial epithelial cells. Similarly, Ge et al. [128] reported that vitamin D alleviated airway hyperresponsiveness in PM-exposed mice. This improvement was attenuated in HO-1 knockout cell lines, confirming the crucial role of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in asthma development.

Oxidative stress disrupts the redox balance, leading to airway epithelial cell damage, inflammation, and immune dysregulation in pediatric asthma. This highlights the potential of antioxidants in mitigating these effects and improving asthma outcomes. As shown in Table 1 (Ref. [86, 107, 127, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147]), both natural and synthetic antioxidants have been investigated for their therapeutic potential in managing pediatric asthma.

| Type | Antioxidant | Results | References |

| Daily food source | Vitamin C | Supplementation in smoking pregnant women could effectively reduce the incidence of asthma in children | [129] |

| Positive effects only in children with moderate to severe asthma, but it was ineffective in the adult group | [130] | ||

| High-dose vitamin C (130 mg/kg body weight per day) could reduce eosinophilic infiltration in airway inflammation in asthmatic mice | [131] | ||

| Vitamin D | Reducing nitric oxide formation, oxidative forces, eosinophil, neutrophil | [132, 133, 134] | |

| No effect on improvement or progression of asthma symptoms in children | [135] | ||

| No significant association with changes in lung function metrics, asthma control, or asthma-related quality of life in children with asthma | [146] | ||

| Vitamin E | Serum vitamin E concentrations at year 1 were not associated with allergies or asthma by 6 years of age | [137] | |

| Vitamin E supplementation was not associated with childhood asthma | [138] | ||

| Serum vitamin E levels had little or no association with asthma in children aged 4–16 years | [136] | ||

| Pure fruit juice | No associations were found between pure fruit juice, SSBs and fruit consumption and the overall prevalence of asthma from 11 to 20 years | [139] | |

| PUFAs | Intake of long-chain n-3 PUFA was associated with a lower risk of childhood asthma | [107] | |

| Magnesium | Magnesium intake was negatively correlated with the occurrence of childhood asthma | [147] | |

| Intravenous magnesium sulfate can significantly improve respiratory function in children with asthma and reduce hospitalization rates | [140] | ||

| Plant extracts and chemical synthesis | Corticosteroids | Increased plasma selenium concentration and SOD activity | [141, 142, 143] |

| Zingerone | Activated the AMPK/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway | [144] | |

| Isoquinoline alkaloid protopine | Upregulated the TLR4/myd88/NF-κb pathway and NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis | [86] | |

| Salidroside | Alleviated ROS production, decreased the level of MDA, prevented the reduction of CAT, SOD and GSH-Px, and activated Nrf2 pathway | [127] | |

| N-acetylcysteine | Neutralized free radicals, reduced oxidative stress, inhibited inflammatory responses, and suppressed airway hyperresponsiveness | [145] |

SSBs, sugar-sweetened beverages; PUFAs, polyunsaturated fatty acids; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; GSH-Px, Glutathione Peroxidase.

Natural antioxidants, particularly those found in vegetables and fruits, play a role in reducing oxidative stress. Increased vegetable intake is associated with lower airway inflammation rates and asthma in school-aged children [148]. Key food-derived antioxidants include vitamins C, D, and E. Some studies suggest vitamin C can help prevent and manage childhood asthma, although the evidence is inconsistent [129, 130, 131]. While vitamin D supplementation has shown therapeutic benefits in mice models [132, 133, 134], clinical studies in children have not demonstrated significant improvements in lung function, asthma control, or quality of life [132, 135]. Therefore, it is not recommended for treating childhood asthma. Similarly, vitamin E has not shown therapeutic benefits for childhood asthma [136, 137], though maternal supplementation during pregnancy may reduce the incidence of asthma in infants, suggesting a potential preventive effect [138].

Fruits contain antioxidant compounds such as polyphenols. Low levels of pure fruit juice intake are associated with higher asthma incidence in 11-year-olds, but increasing pure fruit juice intake does not improve asthma at any age [139]. Clinical studies have shown that pomegranate extract, rich in polyphenols, can improve asthma symptoms [149]. Dietary intake of n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) is also associated with pediatric asthma risk. Higher plasma levels of very-long-chain n-3 PUFAs, arachidonic acid, and n-3 PUFA

Metal ions such as magnesium and selenium, which are cofactors for antioxidant enzymes, including SOD and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), enhance antioxidant capacity [150, 151, 152]. Lower levels of these ions have been observed in children with asthma [153, 154], suggesting a role in the development of childhood asthma. Intravenous administration of these ions significantly improves more than inhalation [140].

Current asthma treatments often involve corticosteroids to reduce inflammation [155]. Corticosteroids decrease the release of superoxide anions from blood mononuclear cells in asthma patients and can restore the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as Cu and Zn-SOD in the bronchial epithelium [141, 142]. For example, prednisone significantly increases plasma selenium concentrations, providing a positive antioxidant effect in asthma patients [143]. Plant-derived active extracts, such as ginger ketone and salidroside, have shown potential in asthma treatment by activating Nrf2, reducing ROS, and alleviating airway hyperresponsiveness [127, 144]. Isoquinoline alkaloid protopine activates the TLR4 pathway, reducing oxidative stress and inhibiting apoptosis in airway epithelial cells [86].

N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a glutathione precursor, significantly reduces eosinophilic airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in asthmatic mice [156]. Clinical studies have confirmed the therapeutic value of NAC in shortening the duration of cough and asthma symptoms in children [145].

Although there is a strong link between oxidative stress and pediatric asthma, long-term research is needed to better understand and apply antioxidants in clinical treatment. Further investigation into the relationship between asthma and oxidative stress will help promote the clinical application of antioxidants in asthma management.

Childhood asthma is a chronic inflammatory respiratory tract disease arising from the interplay between genetic predispositions and environmental exposures. In pediatric asthma, cells produce a substantial volume of ROS and RNS, leading to an imbalance in redox homeostasis. Environmental air pollutants, particulate matter, and components of cigarette smoke contain oxidative elements that, when inhaled, increase oxidative stress. This heightened oxidative stress facilitates the release of inflammatory cytokines through pathways such as NF-

YH written the preliminary draft and contributed for analysis and making the figures. LJ contributed in conceptualization, and writing the review. MZ and SY contributed to overall supervision, including editing the manuscript and searching for references. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work

Not applicable.

We thank Bullet Edits Limited for the linguistic editing and proofreading of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.