1 Country Reproductive Medicine Center, The Second Hospital of Lanzhou University, 730030 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

This study investigated necroptosis-related molecular alterations in the endometrium of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) using quantitative proteomic analysis and developed a predictive model for pregnancy outcomes based on these findings.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry was used to identify and quantify endometrial proteins. Differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were screened and subjected to Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses to identify key pathways. Candidate prognostic necroptosis–related proteins were obtained by intersecting DEPs with the necroptosis gene set, followed by univariate Cox and Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression analyses to select those associated with pregnancy outcomes and construct a predictive model.

A total of 611 DEPs were identified (132 upregulated and 479 downregulated). KEGG enrichment revealed significant involvement of the necroptosis pathway. Six necroptosis-related proteins were identified using Cox and LASSO regression analyses and used to construct the predictive model. Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that the low-risk group had significantly better pregnancy outcomes than the high-risk group. The model achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.903 for predicting live birth at 37 weeks, and decision curve analysis demonstrated superior clinical benefit compared to conventional clinical indicators. Furthermore, correlation analysis revealed significant associations between necroptosis-related proteins and classical endometrial receptivity markers, suggesting potential molecular crosstalk.

Proteomic profiling revealed enrichment of the necroptosis pathway in the endometrium of patients with PCOS. The constructed model indicated preliminary predictive potential for pregnancy outcomes, suggesting that necroptosis may contribute to impaired endometrial receptivity.

Keywords

- necroptosis

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- endometrial receptivity

- proteomics

- pregnancy outcome

- predictive model

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common endocrine disorders among women of reproductive age, affecting approximately 10% of the female population [1]. The pathogenesis of PCOS is multifactorial and involves ovulatory dysfunction, hyperandrogenism, and insulin resistance (IR) [2, 3]. Recent evidence suggests that beyond ovarian factors, local metabolic disturbances and inflammatory microenvironmental changes in the endometrium play pivotal roles in implantation failure [4]. During assisted reproductive treatment, women with PCOS often exhibit decreased endometrial receptivity; even when high-quality embryos are obtained, their pregnancy outcomes remain significantly poorer than those in women without PCOS [5, 6, 7]. Hyperandrogenism and IR synergistically disrupt glucose–lipid metabolism, oxidative balance, and immune–inflammatory homeostasis within the endometrium, leading to impaired decidualization, aberrant angiogenesis, and defective embryo implantation [8, 9, 10, 11]. Moreover, recent studies indicate that hyperandrogenism, IR, and obesity are associated with downregulated expression of endometrial receptivity markers and elevated inflammatory cytokines, which may further compromise implantation and gestational success [8]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying endometrial impairment in PCOS remain incompletely understood, necessitating further investigation into the roles of cell death and inflammatory responses in its pathophysiology.

Necroptosis, a form of regulated inflammatory cell death mediated primarily by receptor-interacting protein kinase 1, receptor-interacting protein kinase 3, and mixed lineage kinase domain-like, triggers immune activation and promotes chronic inflammation within the endometrial microenvironment [12, 13, 14]. Increasing evidence indicates that excessive necroptosis contributes to ovarian dysfunction by disrupting granulosa cell survival and steroidogenesis, aggravating follicular atresia and ovulatory failure [15]. In the endometrium, necroptosis-associated signaling amplifies cytokine release and immune cell infiltration, leading to local inflammatory remodeling and impaired receptivity [16]. Furthermore, dysregulated necroptosis interferes with embryo–endometrium communication, resulting in implantation failure and early pregnancy loss [17]. However, its precise role in PCOS-related endometrial dysfunction and pregnancy outcomes remains poorly understood, necessitating further research into the underlying mechanisms.

In this study, we performed proteomic and clinical data analyses on endometrial samples from patients with PCOS to explore the relationship between necroptosis-related proteins and PCOS-associated endometrial dysfunction, as well as their impact on pregnancy outcomes. By constructing a predictive model, we established a necroptosis–pregnancy outcome association framework, providing a theoretical basis for developing targeted strategies to improve reproductive prognosis in patients with PCOS.

This study included women treated at the Reproductive Medicine Center of the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University between May 2024 and May 2025. A total of 36 endometrial samples were collected, including 30 from patients diagnosed with PCOS undergoing in vitro fertilization–embryo transfer and 6 from healthy fertile controls.

Given the exploratory nature of this proteomic study, no a priori power

calculation was performed. A post hoc power analysis based on the observed

average effect size across six key differentially expressed proteins (Cohen’s d =

1.42; n₁ = 30, n₂ = 6;

PCOS was diagnosed according to the Rotterdam criteria, requiring at least two

of the following: (1) oligo- or anovulation; (2) clinical or biochemical

hyperandrogenism; and (3) polycystic ovarian morphology (

All participants underwent endometrial biopsy under hysteroscopy during the midluteal phase. Biopsy samples were rinsed in saline, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80 °C for proteomic analysis.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University (Approval No. 2025A-774). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Baseline clinical data included maternal age, height, weight, and body mass

index (BMI). In addition, age and BMI were further categorized into clinically

relevant subgroups (

Venous blood was collected on the day of endometrial biopsy for biochemical and

hormonal measurements. All biochemical and hormonal data were obtained from the

hospital’s electronic medical record system, with assays performed by the

Department of Clinical Laboratory under standardized procedures. Serum levels of

anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating

hormone (FSH), testosterone (T), and fasting insulin (FINS) were measured using a

chemiluminescence immunoassay on the Cobas 8000 analyzer (E602; Roche

Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Fasting blood glucose (FBG) and lipid

parameters including total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides (TGs) were measured

enzymatically on the Cobas 8000 analyzer (C702; Roche Diagnostics). The

homeostatic model assessment of IR (HOMA-IR) was calculated as follows: HOMA-IR =

[FBG (mmol/L)

Clinical pregnancy was confirmed by both ultrasonography and laboratory testing.

Specific criteria included observation of an intrauterine gestational sac and

fetal cardiac activity via transvaginal ultrasound at

Endometrial tissues were homogenized (FastPrep-24 5G; MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, USA) under liquid nitrogen and lysed in SDT lysis buffer (4% Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 150 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) (ED-8452; Guangzhou Saiguo Biotechnology, Guangzhou, China). Samples were shaken at 6.0 m/s for 60 s, followed by six cycles of intermittent sonication (5 s on, 5 s off). Lysates were heated at 100 °C for 15 min and centrifuged at 14,000 g for 40 min. Supernatants were collected for quantification using the BCA assay (G2026; Wuhan Servicebio, Hubei, China).

Proteins were alkylated with 100 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min in the dark and filtered using 10 kDa ultrafiltration units. After washing with urea-alkylating (UA) buffer and 25 mM NH₄HCO₃, proteins were digested overnight with trypsin (1:50, w/w) at 37 °C. Peptides were desalted using C18 cartridges (567270U; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), vacuum dried, and reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid. The peptide concentration was measured at 280 nm, after which samples were fractionated into 10 fractions using a high pH reversed-phase kit (84868; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and then stored in 0.1% formic acid.

Peptide fractions were analyzed by Shanghai Applied Protein Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) using the Evosep One LC system coupled to a timsTOF Pro mass spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA).

Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) was used to generate a spectral library,

followed by data-independent acquisition (DIA) for quantification. DDA settings

were as follows: precursor scan range 300–1800 m/z; resolution 60,000; automatic

gain control (AGC) target 3

Raw MS data were processed with Spectronaut (version 14.4.200727.47784;

Biognosys AG, Schlieren, Switzerland) using the UniProt human protein database.

Search parameters were as follows: trypsin digestion (maximum of 2 missed

cleavages); one fixed modification (carbamidomethylation); and two variable

modifications (oxidation on methionine residues and acetylation on the protein’s

N-terminus. Precursor and fragment tolerances were 10 ppm and 0.02 Da,

respectively, with a false discovery rate (FDR)

DEPs were identified using the “limma” package (version 3.66.0; Bioconductor,

https://bioconductor.org/packages/limma/) in R (v4.5.1; R Foundation for

Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with thresholds

Necroptosis-related gene sets were retrieved from GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/), KEGG (https://www.kegg.jp/), and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) databases. These genes were intersected with the DEPs to identify necroptosis-related DEPs. Machine learning algorithms were applied using R packages “e1071”, “kernlab”, and “caret” to screen for core necroptosis-associated proteins.

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks were constructed using the STRING database (v11.5, https://string-db.org/) and visualized in Cytoscape. Correlation networks among necroptosis proteins were plotted using “corrplot”, “reshape2”, and “igraph”.

Univariate Cox regression (R package “survival”) was used to identify

necroptosis-related DEPs significantly associated with pregnancy outcomes

(p

Patients were divided into high- and low-risk groups based on the median risk score. Principal component analysis was conducted using “Rtsne” and “ggplot2”. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to compare pregnancy outcomes between groups. Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (“timeROC”) were used to assess predictive accuracy at 6, 28, and 37 weeks of gestation. Decision curve analysis (DCA) (“ggDCA”) compared the net clinical benefit of the NecroSig model with conventional predictors (age, BMI, HOMA-IR, lipids). A nomogram and calibration curve were generated to evaluate consistency between predicted and observed live birth rates.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY,

USA) and R 4.5.1. Normality was tested with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

Continuous variables with non-normal distribution are expressed as the median

(P25, P75) and were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test; categorical

variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. p

The clinical and pregnancy data of the two groups are summarized in Table 1. Women with PCOS showed significant elevations in FINS, HOMA-IR, AMH, LH, LH/FSH ratio, and T levels, along with a marked decrease in endometrial thickness (ET). No significant differences were observed in age, height, weight, BMI, FSH, or gestational duration of live birth between the two groups. In the control group, no adverse pregnancy outcomes were observed. By contrast, among the 30 women with PCOS, 14 experienced adverse pregnancy outcomes including 10 early miscarriages, 3 biochemical pregnancies, and 1 late miscarriage. No cases of preterm delivery or stillbirth were recorded.

| Control group (n = 6) | PCOS group (n = 30) | p | ||

| Age (years) | 26.83 |

25.67 |

0.406 | |

| 33.3 (2/6) | 46.7 (14/30) | |||

| 26–30 years (%) | 50.0 (3/6) | 40.0 (12/30) | ||

| 16.7 (1/6) | 13.3 (4/30) | |||

| Height (cm) | 163.17 |

160.87 |

0.345 | |

| Weight (kg) | 60.42 |

62.27 |

0.688 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.80 |

24.02 |

0.181 | |

| 16.7 (1/6) | 6.7 (2/30) | |||

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 (%) | 66.6 (4/6) | 50.0 (15/30) | ||

| 16.7 (1/6) | 43.3 (13/30) | |||

| AMH (ng/mL) | 1.71 |

9.39 |

||

| LH (IU/L) | 5.19 |

11.99 |

||

| FSH (IU/L) | 5.35 (5.10, 6.57) | 7.28 (6.36, 7.96) | 0.018* | |

| LH/FSH | 0.91 |

1.76 |

||

| T (ng/mL) | 25.74 |

42.53 |

0.039* | |

| FINS (mIU/L) | 7.32 (5.75, 12.18) | 16.00 (9.76, 26.03) | 0.010* | |

| HOMA-IR | 1.73 |

4.55 |

0.041* | |

| ET (mm) | 9.79 |

4.09 |

||

| Gestational duration | ||||

| Live birth time (weeks) | 37.83 |

38.47 |

0.374 | |

| Gestational time at adverse pregnancy (weeks) | - | 7.93 |

- | |

| Rate of adverse pregnancy outcomes (%) | 0 (0/6) | 46.7 (14/30) | ||

| Early miscarriages (%) | - | 71.4 (10/14) | ||

| Late miscarriage (%) | - | 7.1 (1/14) | ||

| Biochemical pregnancies (%) | - | 21.4 (3/14) | ||

Notes: * Statistically significant difference between groups (p

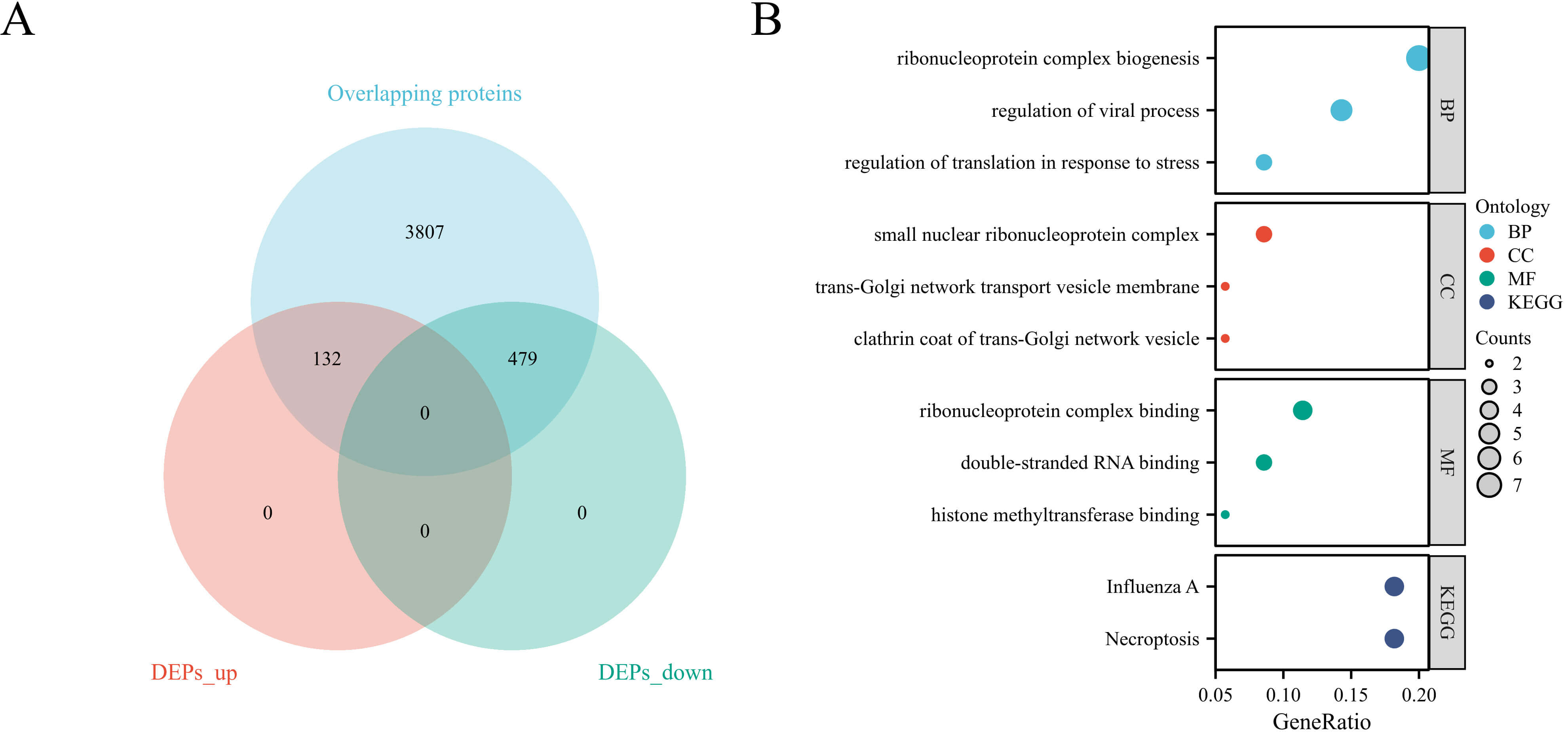

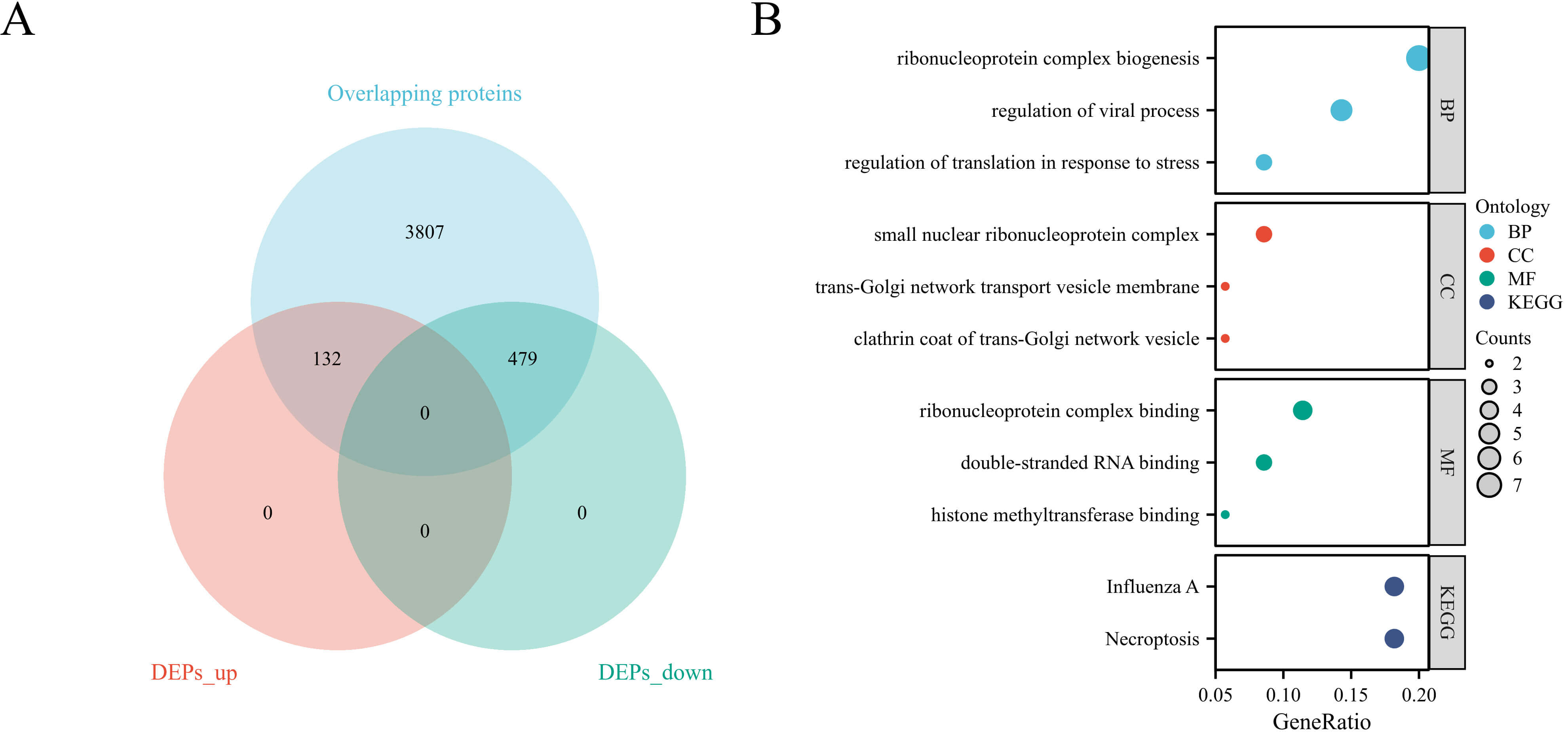

Quantitative proteomic analysis of all endometrial samples was performed to identify PCOS-associated proteins. A total of 4425 proteins were commonly detected in both PCOS and control samples. Among them, 611 proteins were identified as differentially expressed, including 132 upregulated and 479 downregulated proteins in the PCOS group (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Identification and enrichment analysis of differentially expressed proteins. (A) Volcano plot showing DEPs between PCOS and control endometria. (B) Functional enrichment analysis of DEPs. DEPs, differentially expressed proteins; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; BP, Biological Process; CC, Cellular Component; MF, Molecular Function.

To further elucidate the biological functions of the DEPs, GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were performed (Fig. 1B). GO analysis revealed that the DEPs were significantly enriched in biological processes such as ribonucleoprotein complex biogenesis, regulation of viral process, and translational control in response to stress. For the cellular component category, DEPs were mainly associated with the small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex, trans-Golgi network transport vesicle membrane, and clathrin-coated vesicle. Regarding molecular function, enrichment was observed in double-stranded RNA binding, histone methyltransferase binding, and ribonucleoprotein complex binding. KEGG pathway analysis identified influenza A infection and necroptosis as the two most significantly enriched pathways, indicating a potential inflammatory association underlying endometrial dysfunction in PCOS, rather than confirming a direct causal mechanism.

To determine necroptosis-related DEPs associated with PCOS prognosis, 628 necroptosis-related genes were retrieved from public databases (GeneCards, KEGG, and NCBI) and intersected with the PCOS DEPs, yielding 15 overlapping proteins.

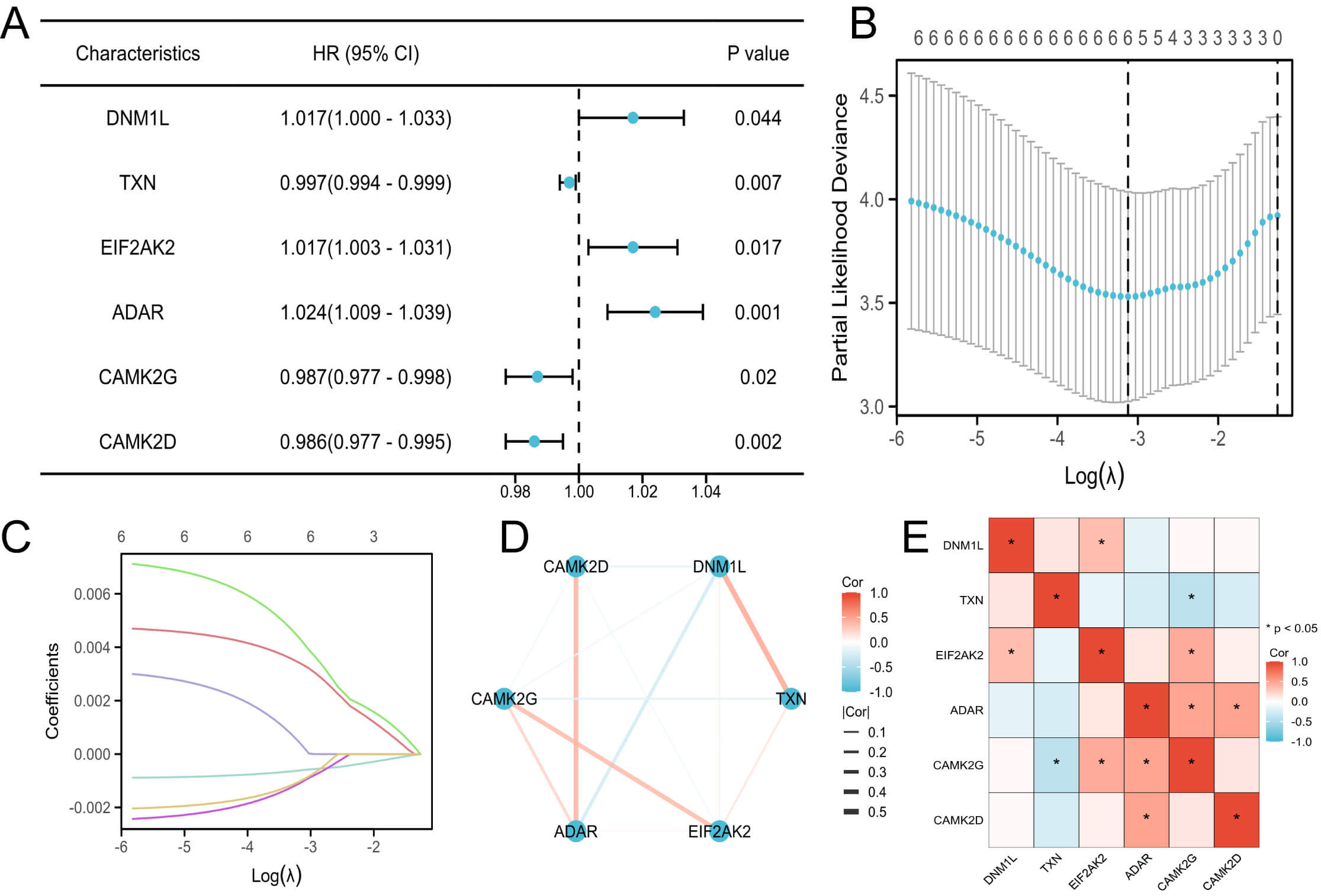

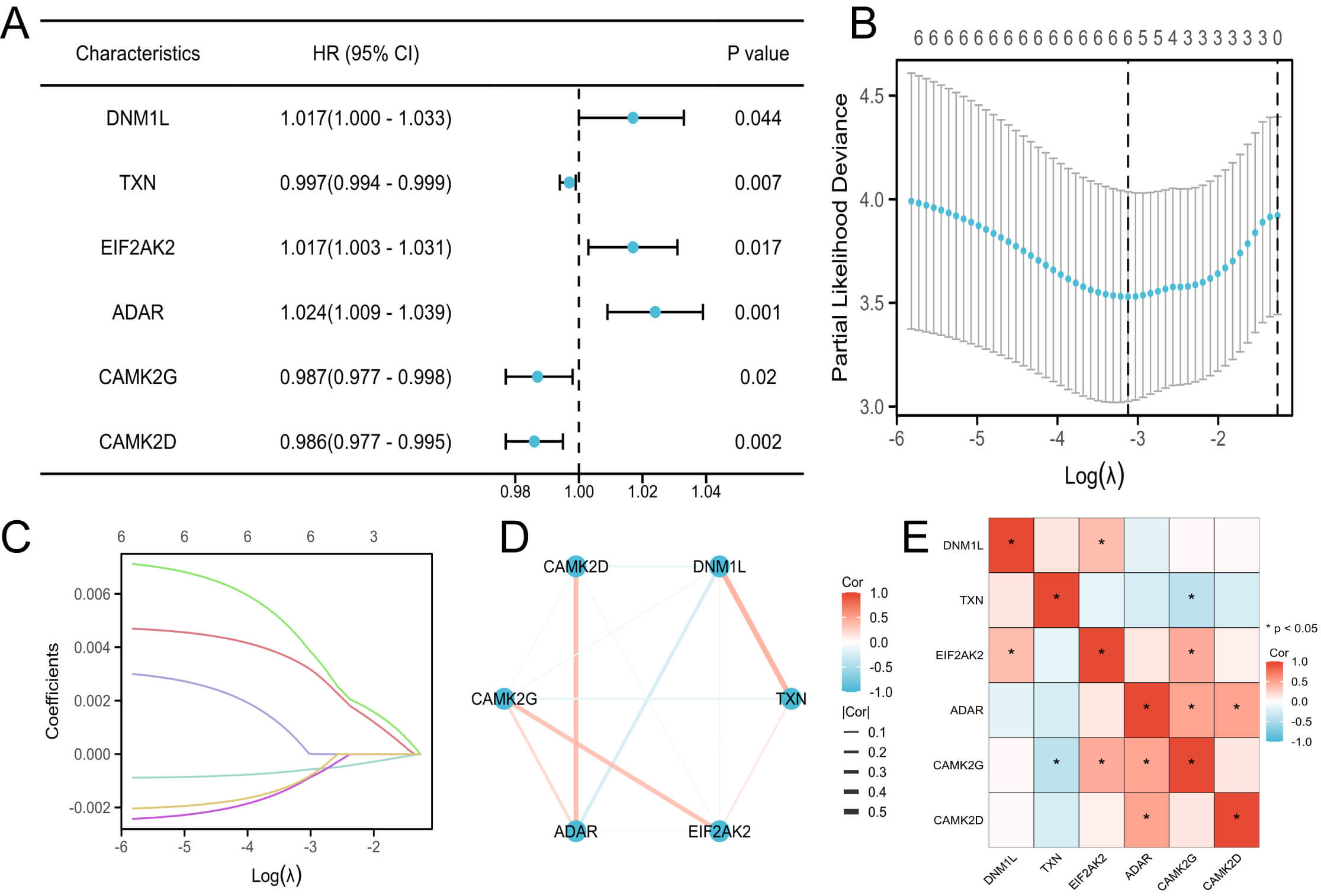

Univariate Cox regression identified several necroptosis-related proteins significantly associated with pregnancy outcomes. Subsequent LASSO regression further reduced the candidates to six prognostically relevant necroptosis-related proteins: dynamin 1 like (DNM1L), thioredoxin (TXN), eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 2 (EIF2AK2), adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR), calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gamma (CAMK2G), and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II delta (CAMK2D) (Fig. 2A–C).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Identification and analysis of prognostic necroptosis-related DEPs. (A) Forest plot of univariate Cox regression for necroptosis-related DEPs. (B) Partial likelihood deviance plot from LASSO regression. (C) LASSO coefficient profiles of the selected proteins. (D) PPI network of prognostic necroptosis-related proteins. (E) Correlation heatmap of the six necroptosis-related DEPs. DNM1L, dynamin 1 like; TXN, thioredoxin; EIF2AK2, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 2; ADAR, adenosine deaminase acting on RNA; CAMK2D, calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II delta; CAMK2G, calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gamma; LASSO, Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator; PPI, protein–protein interaction.

A PPI network constructed using the STRING database illustrated their putative molecular interconnections (Fig. 2D), whereas the correlation heatmap demonstrated their expression relationships (Fig. 2E).

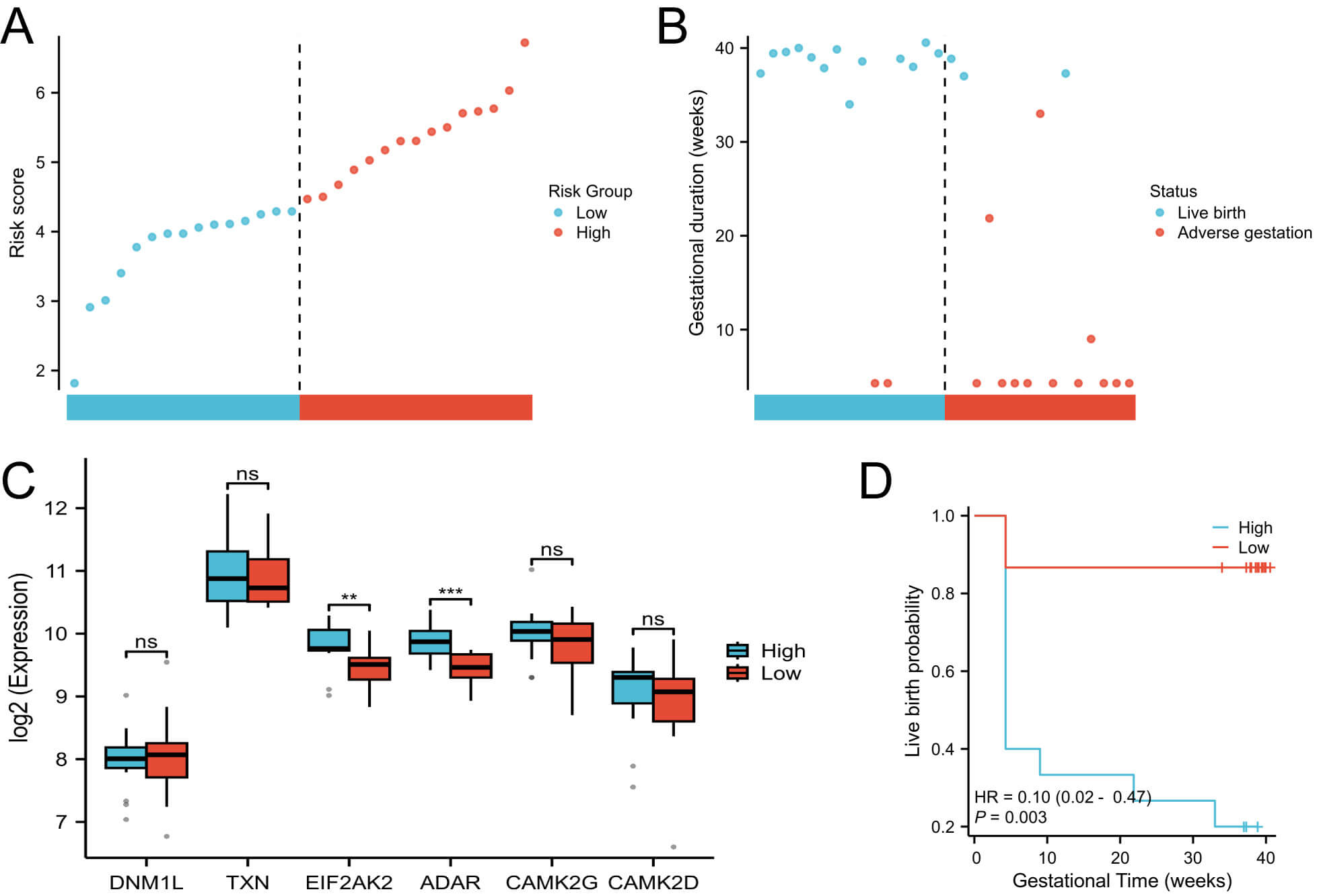

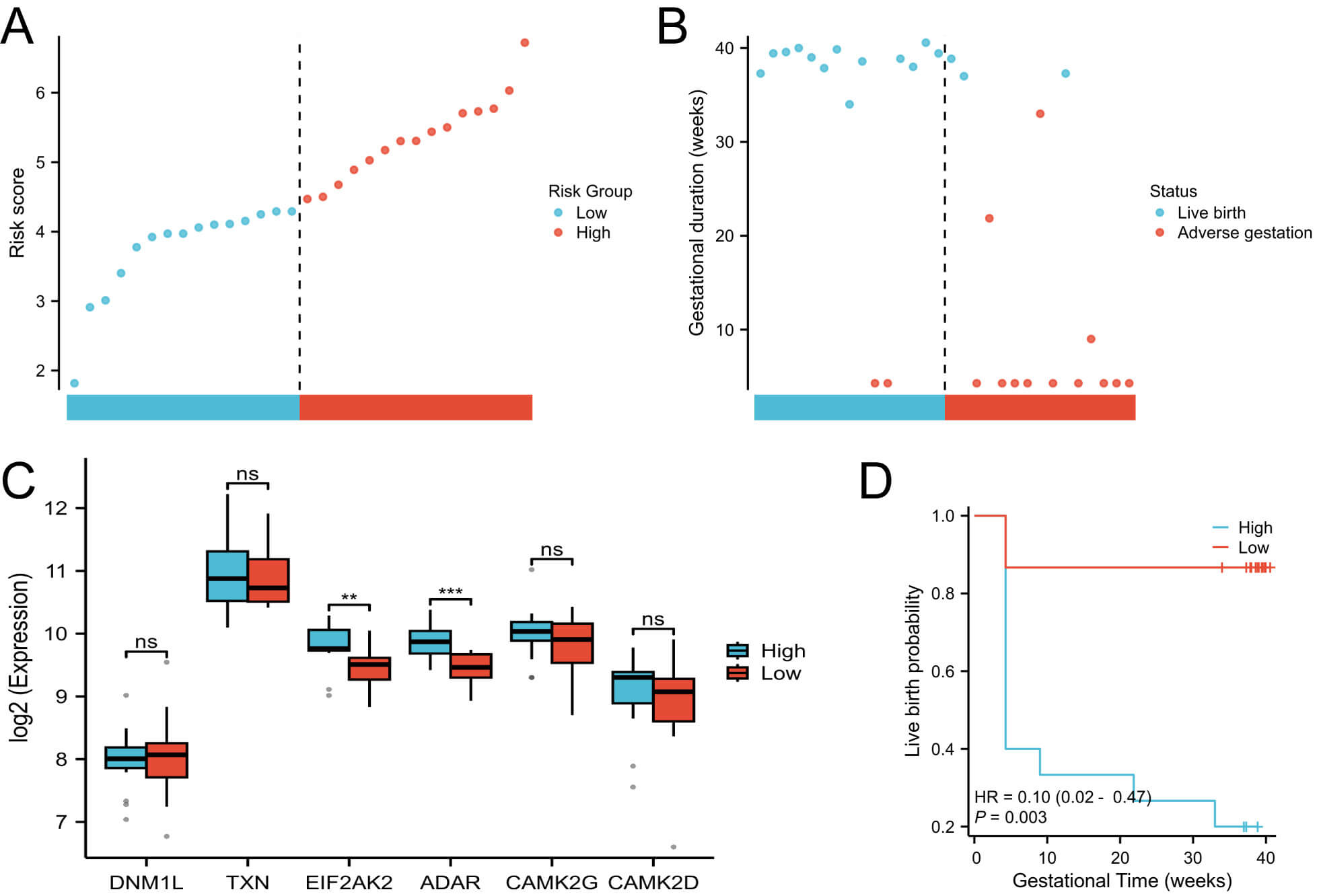

Using the six prognostic necroptosis-related proteins, a necroptosis risk model (NecroSig) was established based on 30 patients with PCOS with pregnancy outcome data. The risk score was calculated as follows:

NecroSig (PCOS) = 0.000280179

Among these, DNM1L, EIF2AK2, and ADAR had positive coefficients, indicating potential risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes; whereas TXN, CAMK2G, and CAMK2D showed negative coefficients, suggesting protective roles. Based on the median NecroSig score, patients with PCOS were stratified into high- and low-risk groups (Fig. 3A). The high-risk group exhibited significantly lower live birth rates than the low-risk group (Fig. 3B). Among the six prognostic proteins, EIF2AK2 and ADAR showed significant expression differences between risk groups (Fig. 3C). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis confirmed that the low-risk group consistently demonstrated superior pregnancy outcomes (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Construction of the NecroSig model. (A) Distribution of risk

scores. (B) Survival status plot showing the relationship between risk score and

pregnancy outcome. (C) Boxplots of protein expression levels between risk groups.

(D) Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing pregnancy outcomes between high- and

low-risk groups. ** p

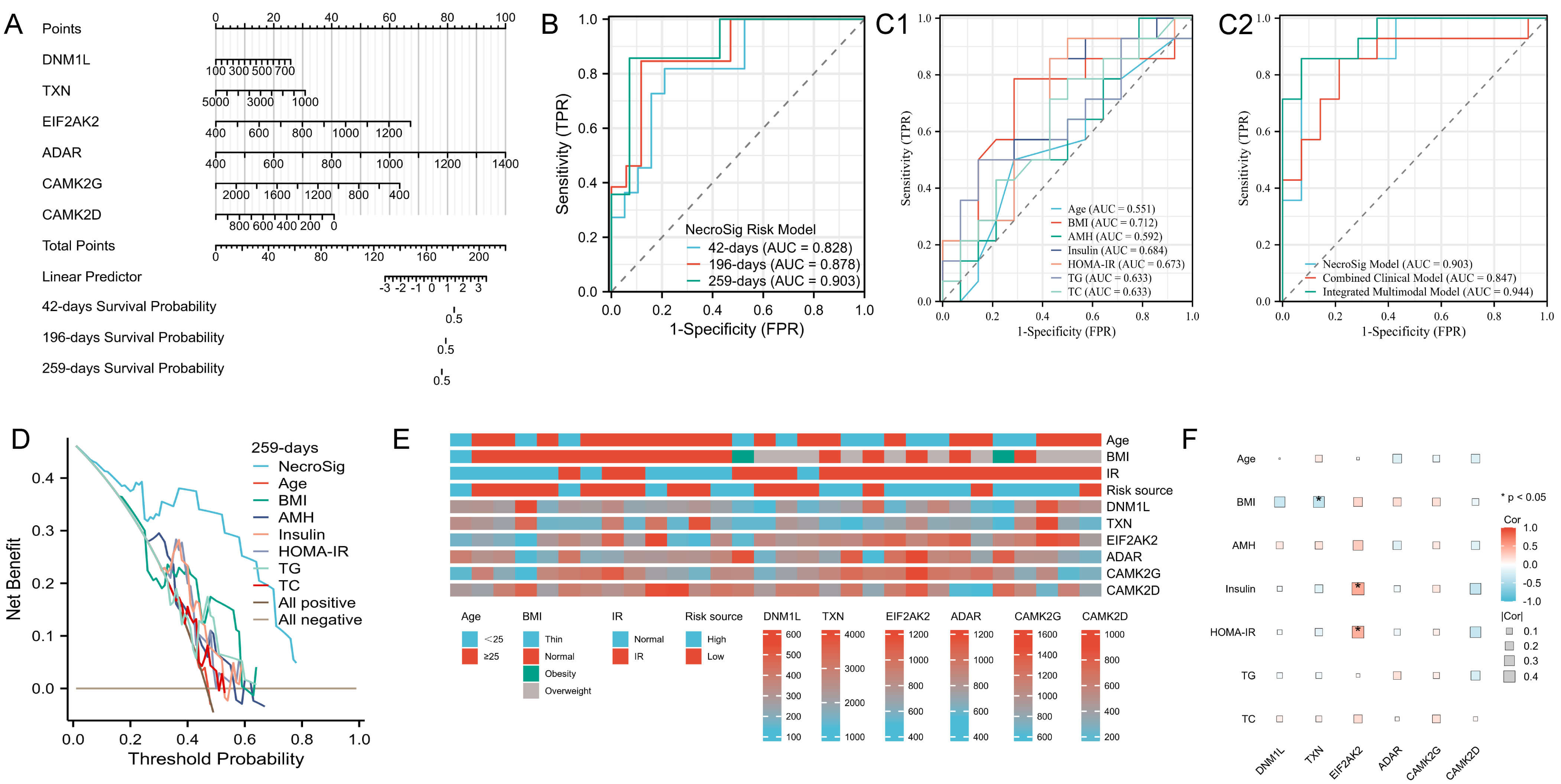

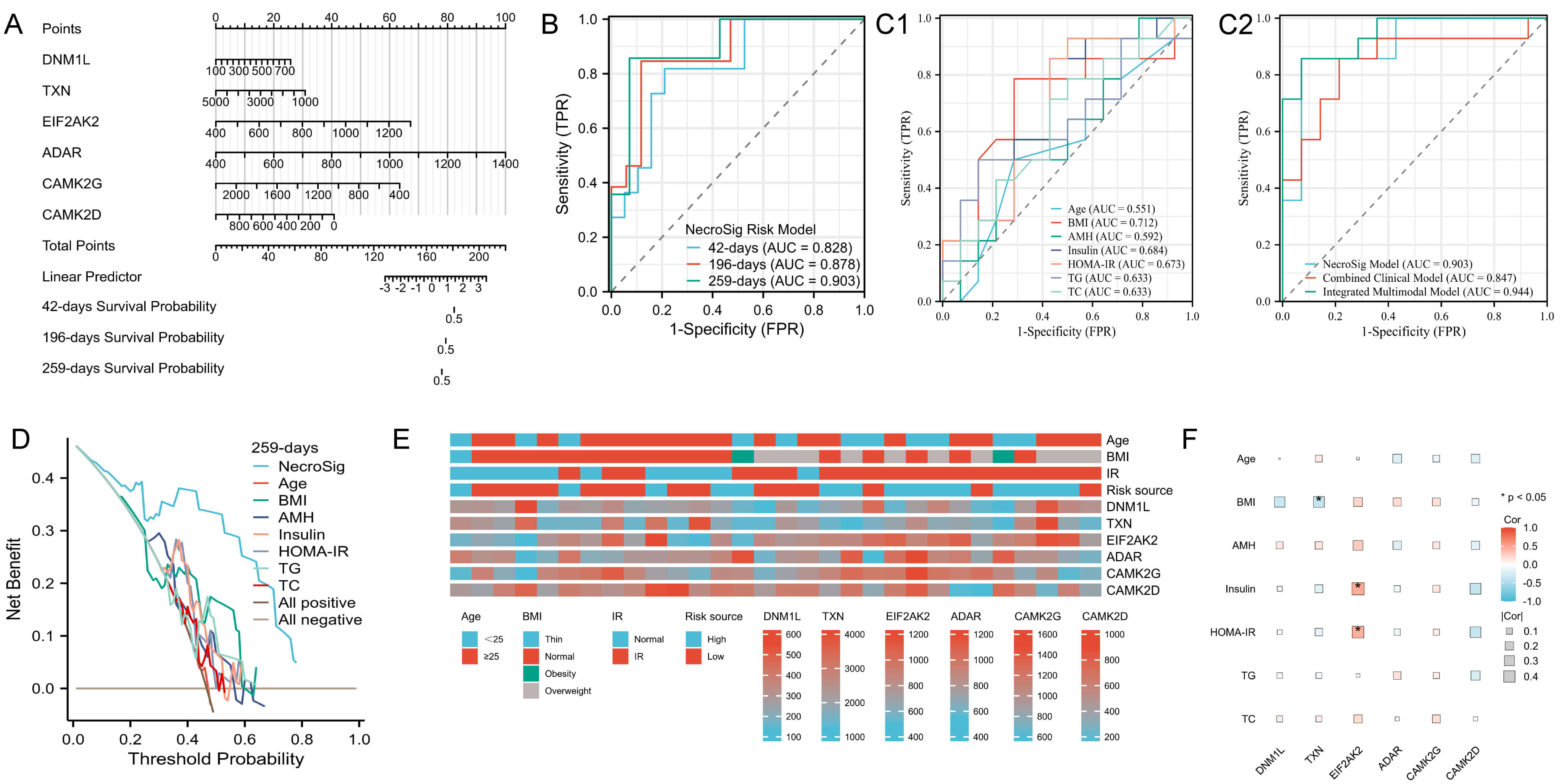

A nomogram integrating the six prognostic proteins was constructed to predict the probability of adverse pregnancy outcomes at 6 weeks (42 days), 28 weeks (196 days), and 37 weeks (259 days) (Fig. 4A). Time-dependent ROC analysis demonstrated strong predictive performance, with area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.828, 0.878, and 0.903 at 6, 28, and 37 weeks, respectively (Fig. 4B). At 37 weeks, the NecroSig model showed higher predictive accuracy than individual clinical parameters such as age (AUC = 0.551), BMI (0.712), AMH (0.592), insulin (0.684), HOMA-IR (0.673), TC (0.633), and TGs (0.633) (Fig. 4C1). A combined clinical model integrating these indicators yielded an AUC of 0.847, still lower than the NecroSig model (AUC = 0.903). When both proteomic and clinical indicators were integrated, the multimodal model demonstrated the highest predictive performance (AUC = 0.944) (Fig. 4C2). The multimodal model showed the highest discriminative ability, highlighting the complementary value of proteomic and clinical markers. DCA further confirmed that the NecroSig model provided greater net clinical benefit compared with conventional indicators (Fig. 4D). Heatmaps revealed distinct clinical feature distributions between high- and low-risk groups (Fig. 4E). Correlation analysis showed significant associations between EIF2AK2 and both fasting insulin and HOMA-IR, whereas TXN was negatively correlated with BMI (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of model performance and correlation with clinical data. (A) Nomogram predicting adverse pregnancy risk at 6, 28, and 37 weeks. (B) Time-dependent ROC curves for live birth prediction. (C1) ROC curves of individual clinical indicators for predicting live birth at 37 weeks. (C2) Comparison between the NecroSig model, the combined clinical model, and the integrated multimodal model. (D) DCA for 37-week outcome prediction. (E) Heatmap showing distribution of clinical features across risk groups. (F) Correlation heatmap between clinical variables and prognostic proteins. AUC, area under the curve; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; DCA, decision curve analysis; FPR, false positive rate; TPR, true positive rate.

Within the PCOS cohort, exploratory correlation analyses were conducted between the six necroptosis-related proteins and classical markers of endometrial receptivity, including homeobox A11 (HOXA11) and integrin subunit beta-1 (ITGB1), ITGB3, and ITGB5 [22]. Three significant associations were identified: DNM1L–ITGB1 (r = 0.38, p = 0.049), CAMK2G–ITGB3 (r = –0.41, p = 0.030), and CAMK2D–HOXA11 (r = –0.57, p = 0.013). These findings support a potential molecular crosstalk between necroptosis and integrin-mediated receptivity pathways (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Tables 1,2).

Impaired endometrial receptivity and ovulatory dysfunction are both central pathological features of infertility associated with PCOS, characterized by abnormal decidualization and failed embryo implantation, which increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes such as miscarriage [5]. However, the mechanisms underlying endometrial dysfunction in PCOS remain incompletely understood, with multiple factors—including hormonal imbalances, IR, cytokine dysregulation, and chronic low-grade inflammation—potentially compromising endometrial receptivity [6]. In this study, quantitative proteomic analyses of the endometrium revealed that PCOS-associated differentially expressed proteins were significantly enriched in the necroptosis pathway, suggesting that necroptosis may play a key role in endometrial dysfunction and adverse pregnancy outcomes in patients with PCOS.

Necroptosis is a programmed cell death modality exhibiting features of both

apoptosis and necrosis, whose excessive activation can trigger inflammatory

responses and tissue damage [23, 24]. We identified six key prognostic proteins

(DNM1L, TXN, EIF2AK2, ADAR, CAMK2G, and CAMK2D). The mitochondrial fission

protein DNM1L can drive excessive mitochondrial division, potentially inhibiting

signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 phosphorylation and

consequently affecting the expression of the endometrial receptivity marker

HOXA10 [25, 26, 27]. Previous study has demonstrated that mitochondrial dysfunction in

mice suppresses HOXA10 expression, impairs endometrial receptivity, and leads to

embryo implantation failure [28]. Moreover, upregulation of ADAR in patients with

PCOS reportedly mediates EIF2AK2 expression, possibly promoting PCOS progression

via the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway [29]. Consistently, our study

identified ADAR and EIF2AK2 as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes in

PCOS, potentially through EIF2AK2-mediated overactivation of autophagy and

subsequent activation of the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome,

which negatively impacts endometrial receptivity [30, 31, 32]. Previous evidence also

indicates that alterations in calcium homeostasis may contribute to implantation

failure. An animal studyi has shown that CaMKII knockdown inhibits transcription

factors nuclear factor of activated T-cells and nuclear factor kappa B, while

reducing prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and PGF2

Additionally, significant correlations observed among DNM1L–ITGB1, CAMK2G–ITGB3, and CAMK2D–HOXA11 further suggest potential regulatory links between necroptosis and endometrial receptivity, indicating that mitochondrial dynamics, calcium signaling, and cell adhesion pathways may cooperatively modulate implantation capacity in PCOS. Notably, integrating clinical indicators with the six-protein NecroSig signature improved the AUC from 0.903 to 0.944, suggesting that a multimodal model combining proteomic and metabolic–hormonal factors may provide more refined risk assessment in PCOS.

Integration of necroptosis-related proteins with clinical metabolic indices provides further insights into the metabolic dysregulation observed in patients with PCOS. EIF2AK2 (also known as PKP), a key mediator of inflammation, IR, and glucose homeostasis in obesity, was positively correlated with insulin levels and the HOMA-IR index, suggesting that EIF2AK2 may exacerbate endometrial metabolic dysfunction by interfering with insulin signaling [35, 36]. IR can induce hyperandrogenism, thereby disrupting glucose metabolism and suppressing endometrial cell proliferation and activity, ultimately impairing endometrial receptivity [37]. Previous study has shown that TXN mitigates macrophage-driven inflammation in adipose tissue and reduces pro-inflammatory gut microbiota, alleviating high-fat diet-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome [38]. This finding supports our observation of a negative correlation between TXN expression and BMI, indicating that obesity-related oxidative stress may deplete protective proteins.

Beyond its mechanistic insights, the present study also holds potential clinical significance. The NecroSig model could serve as a valuable tool for stratifying patients with PCOS based on their predicted pregnancy risk, thereby supporting personalized clinical decision-making. For example, patients classified as high risk could benefit from individualized interventions such as insulin-sensitizing agents (e.g., metformin) or anti-inflammatory therapies aimed at restoring endometrial receptivity. Furthermore, integrating proteomic data with routinely available clinical biomarkers (e.g., AMH, HOMA-IR) may facilitate the development of simplified surrogate models suitable for clinical implementation. However, the high cost, technical complexity, and infrastructure requirements of LC–MS/MS-based proteomic profiling currently limit its use in routine reproductive medicine. Future efforts should focus on translating the proteomic signature into clinically measurable surrogates or immunoassay-based platforms, thereby improving accessibility and promoting real-world application of precision endometrial assessment in PCOS.

Despite the robust predictive performance of the NecroSig model constructed in

this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the single-center

design and the relatively small sample size—particularly the limited number of

control endometrial samples—may restrict the generalizability of our findings.

The small control cohort also reduces statistical power for differential protein

detection and increases sensitivity to individual variability or outliers, which

may elevate the risk of false-positive identifications despite stringent FDR

correction. This limitation mainly reflects the ethical and practical challenges

of obtaining endometrial tissues from healthy fertile women. Although the control

sample was limited, a post hoc power estimation (power

This study identified six necroptosis-related proteins associated with pregnancy outcomes in PCOS and developed a preliminary necroptosis-based prognostic framework (NecroSig). The model demonstrated promising predictive potential within this exploratory cohort, suggesting that necroptosis may be involved in the pathophysiology of PCOS through effects on endometrial receptivity and embryo implantation. These findings provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying PCOS and offer a foundation for future studies aimed at validating and refining individualized risk prediction and therapeutic strategies.

The mass spectrometry proteomics data generated in this study have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the iProX partner repository (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) under the dataset identifier PXD032383. Clinical data derived from patient records cannot be publicly released due to institutional privacy regulations and ethical restrictions. However, these data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with appropriate ethics approval, in accordance with institutional and national guidelines.

KXW and FW jointly designed the study. WHX and XLT collected the data; WHX and CBT performed data analysis and wrote the statistical results section; XLT verified the data, generated the figures, and contributed to writing the results description. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University (Approval No. 2025A-774) for the secondary analysis of previously collected clinical and proteomic data. The original sample collection was conducted under a prior ethics approval by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University (Approval No. 2019A-057), and written informed consent had been obtained from all participants at the time of collection. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

We thank Ejear for their professional manuscript editing service. All Figures in this study were created using Xiantao Academic (https://www.xiantaozi.com).

The research was supported by Cuiying Scientific and Technological Innovation Program of The Second Hospital & Clinical Medical School, Lanzhou University (Grant No. CY2023-MS-B13), Lanzhou Science and Technology Program Project (Grant No. 2023-ZD-82), the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (Grant No. 24JRRA329) and the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province (Grant No. 22JR5RA974).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL47322.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.