1 Department of Dermatology, Huashan Hospital Fudan University, Shanghai Institute of Dermatology, 200040 Shanghai, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells are crucial in inflammatory skin diseases, but their diverse functions and lack of a standardized classification system across diseases have limited deeper insights into their roles.

We merged single-cell transcriptomic data from 40 skin samples to create a comprehensive atlas of NK cells across various skin diseases, identifying nine distinct NK cell subsets with unique functions.

Our analysis revealed a conserved Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AHR)+ NK cell subset that is broadly present across multiple skin diseases. Notably, the Granzyme B (GZMB)+ NK cell subset may be associated with the pathogenesis of psoriasis (PSO) and appears to undergo a differentiation trajectory toward IL13+ NK cells in the pseudotime analysis. This finding suggests a potential role for these cells in mediating paradoxical cutaneous inflammation. Our analysis identified NK cells expressing GZMB in a variety of skin diseases. Notably, the NK cell subpopulation expressing GZMB appears to be associated with the pathogenesis of PSO and ultimately exhibits the expression of IL13 in pseudotime analysis, suggesting that it may play a role in regulating contradictory skin inflammation.

This study offers a comprehensive overview of skin NK cells, identifies pathogenic subsets that may drive skin disease progression, and provides novel insights for future targeted therapies.

Keywords

- natural killer cells

- psoriasis

- atopic dermatitis

- GZMB

- IL13

NK cells, initially identified as large granular lymphocytes with innate

cytotoxicity, were noted for their ability to directly lyse tumor cells and later

recognized as a distinct lymphocyte lineage [1]. As key components of the innate

immune system, NK cells mediate cytotoxicity against pathogen-infected host cells

through the release of granzymes and perforin [2]. In addition, NK cells possess

antitumor capabilities, exhibiting innate cytotoxicity against both primary and

metastatic tumor cells, thereby suppressing tumor proliferation, migration, and

distant dissemination [3, 4]. Notably, NK cells also possess potent immunoregulatory

functions. By secreting cytokines such as interferon-

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has divided NK cells into three major subsets: CD56dim NK cells, CD56bright NK cells, and HCMV-driven adaptive NK cells. CD56dim NK cells are characterized by high expression of fibroblast growth factor binding protein 2 (FGFBP2), granzyme B (GZMB), spondin 2 (SPON2), and Fc fragment of IgG, low affinity IIIa (FCGR3A); CD56bright NK cells exhibit elevated levels of Coactosin-like protein 1 (COTL1), CD44, X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (XCL1), lymphotoxin-beta (LTB), and granzyme K (GZMK); while adaptive NK cells are defined by high expression of killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily C member 2 (KLRC2), cluster of differentiation 3 epsilon (CD3E), and Zinc finger and BTB domain-containing protein 38 (ZBTB38) [9, 10]. Recent studies have revealed that GZMB is significantly upregulated in inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis (PSO) and vitiligo [11, 12]. In addition, NK cells exhibit cytotoxic effects against melanoma cells and may hold unique therapeutic potential in the treatment of melanoma [13]. In contrast, the initiation and progression of melanoma may be more dependent on the HPK1 factor [14]. However, the specific functional roles and heterogeneity of distinct NK cell subsets across various skin diseases remain to be systematically elucidated.

To conduct a comprehensive analysis of the phenotypic characteristics and pathogenic mechanisms of natural killer cells, this study aggregated and meticulously examined publicly available single-cell RNA sequencing data that encompassed a variety of inflammatory conditions (such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and lupus) and cutaneous malignancies (such as melanoma). The study meticulously delineated the molecular profiles of disease-specific NK cell phenotypes in inflammatory skin diseases and skin tumors, underscored the pronounced heterogeneity of NK cells in skin lesions, and unearthed potential therapeutic targets for subsequent clinical interventions.

This study involved 815 patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, diagnosed by certified dermatologists. Blood samples were collected from peripheral veins, and serum was extracted for further analysis. All participants had no history of autoimmune or systemic inflammatory conditions. Prior to participation, written informed consent was secured from each individual. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki principles and received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University under protocol number 2020-1202.

Researchers collected single-cell transcriptomic datasets encompassing six common skin conditions from public databases. They individually analyzed nine single-cell RNA sequencing datasets, which covered a variety of skin diseases. To avoid altered gene expression from tissue dissociation and ensure data comparability, single-cell datasets generated via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) were excluded.

During data processing, to ensure consistency, the research team excluded cells with a library size of less than 500, fewer than 200 detected genes, or a mitochondrial gene expression percentage exceeding 10%. They also utilized the DoubletFinder tool (https://github.com/chris-mcginnis-ucsf/DoubletFinder) to identify and remove potential doublets. Additionally, the research team converted Ensembl gene IDs to corresponding gene symbols using annotations from Biomart via the org.Hs.eg.db package (https://bioconductor.org/packages/org.Hs.eg.db/).

After initial quality control, the researchers independently processed the raw data for each skin condition. They adopted the standard workflow of Seurat (version 5.1.0, Satija Lab, New York, USA), utilizing a series of functions including NormalizeData, RunHarmony, RunUMAP, FindVariableFeatures, ScaleData, RunPCA, FindNeighbors, and FindClusters, with a clustering resolution of 0.5. To accurately identify NK cells and exclude the interference of other immune cell subpopulations, researchers defined cells co-expressing PTPRC (CD45), KLRB1 (CD161), and IL7R (CD127) as ILCs and cells co-expressing KLRD1 (CD94) as NK cells [15]. To further ensure the accuracy of identification, they also employed the automated annotation tool SingleR (https://bioconductor.org/packages/SingleR/) for independent validation. Through this process, the researchers identified NK cells and retained them for subsequent reintegration analysis.

Prior to dataset reintegration, only genes shared across all skin conditions were retained to ensure comparability. Harmony (v1.2.0) (https://github.com/immunogenomics/harmony) was applied to correct for batch effects among different donors. Based on parameters described in the previously mentioned Seurat workflow, subclusters consisting of fewer than 1000 cells and located distantly from main clusters were identified as potential doublets and removed. The remaining cells were designated as the final NK cell population.

The Harmony function was applied to the sorted NK cells for batch correction, and a clustering resolution of 0.5 was set in the FindClusters function. To annotate each subset, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the Wilcox algorithm via the FindAllMarkers function.

Enrichment analyses for Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes

and Genomes (KEGG) were carried out using the enrichGO and enrichKEGG R packages,

with a threshold of adjusted p-value

To infer cellular developmental trajectories, pseudotime ordering and trajectory construction were performed using the core algorithms of Monocle2. Visualization was conducted with the R package Slingshot (v2.12.0, https://bioconductor.org/packages/Slingshot/).

Visualization of the single-cell datasets was conducted in the R environment using several key packages, including ggplot2, scRNAtoolVis, pheatmap, ComplexHeatmap, and ggvenn.

The tissue sections were first treated with eco-friendly dewaxing solutions I, II, and III (G1128, Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei, China) for 10 minutes each. They were then dehydrated in three changes of absolute ethanol (100092183, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent, Shanghai, China), spending 5 minutes in each, before being rinsed with distilled water. Antigen retrieval was conducted by heating the slides in retrieval buffer for 30 minutes, ensuring minimal buffer evaporation and avoiding tissue dryness. After heating, the slides were cooled naturally to room temperature. Finally, the sections were washed in PBS (G0002, Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei, China) (pH 7.4) on a shaking platform, with three 5-minute cycles.

After gently removing excess liquid, a hydrophobic barrier was drawn around the tissue using a PAP pen. Blocking was performed for 30 minutes with bovine serum albumin (BSA): for goat-derived primary antibodies, 10% donkey serum was used; for all other sources, 3% BSA was applied. Slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C in a humidified chamber with the following primary antibodies (dilution ratio: 1:500): IL13 (ABS120028, Absin, Shanghai, China), GZMB (GB15092, Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei, China), and NCAM1 (GB12041, Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei, China). The next day, slides were washed in PBS (pH 7.4) on a shaker three times, 5 minutes each.

Following this, the sections were incubated with the following secondary

antibodies (dilution ratio: 1:300) in the dark at room temperature for 50 minutes: CY3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (GB21303, Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei, China) and CY3-conjugated goat

anti-mouse IgG (GB21301, Servicebio, Wuhan, Hubei, China). After incubation, the slides

were washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4), for 5 minutes each. Nuclear staining

was performed using DAPI, which was applied and allowed to incubate under the

same dark conditions for 10 minutes, after which another series of PBS washes (3

This kit utilizes a double-antibody sandwich assay. An anti-Human IL18 antibody (A1010A0118, Biotnt, Shanghai, China) coats the enzyme-linked immunosorbent plate. Human IL18 in standards and samples binds to this monoclonal antibody. Biotinylated anti-Human IL18 is added to form a plate-bound immune complex. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin attaches to biotin. After adding the substrate solution, a blue color forms. The reaction stops upon adding a termination solution. The Human IL18 concentration correlates directly with the OD value at 450 nm. A standard curve allows determination of Human IL18 levels in samples. The experiment used 80 human peripheral blood samples.

Introduce 100 µL of relevant standards and samples to the wells,

seal, mix well, and incubate at 37 °C for 60 minutes. Thoroughly rinse

the plate four times with 1

The single-cell datasets used in this study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus and the Genome Sequence Archive (Table 1, Ref. [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24]). The disease data we selected were all collected before any treatment was administered. The code used for bioinformatics analysis can be found at https://github.com/issac0124/1/issues.

| Transcriptomic dataset | Accession numbers |

| Healthy | GSE180885 [15], PRJCA006797 [16] |

| Psoriasis | GSE228421 [17], GSE221648 [18], GSE230842 [19] |

| Atopic dermatitis | GSE180885 [15], GSE269981 [20] |

| Lupus | GSE179633 [21], GSE224198 [22] |

| Vitiligo | GSE203262 [23], PRJCA006797 [16] |

| Melanoma | GSE277165 [24] |

Statistical analyses were performed using the “stats” package in R software (version 3.6.2, R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) and GraphPad Prism (version 8.0, GraphPad Software, LLC, La Jolla, CA, USA). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

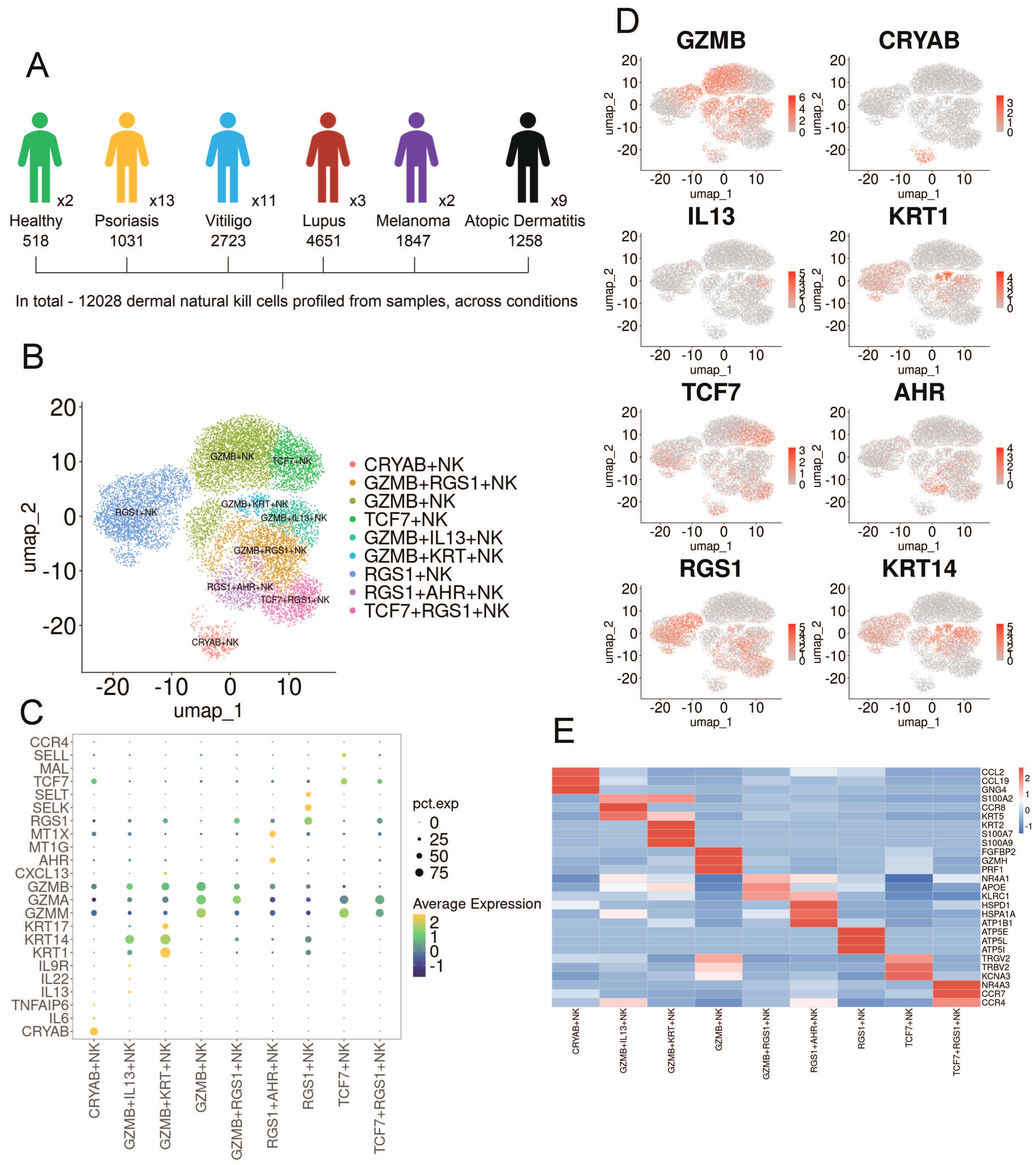

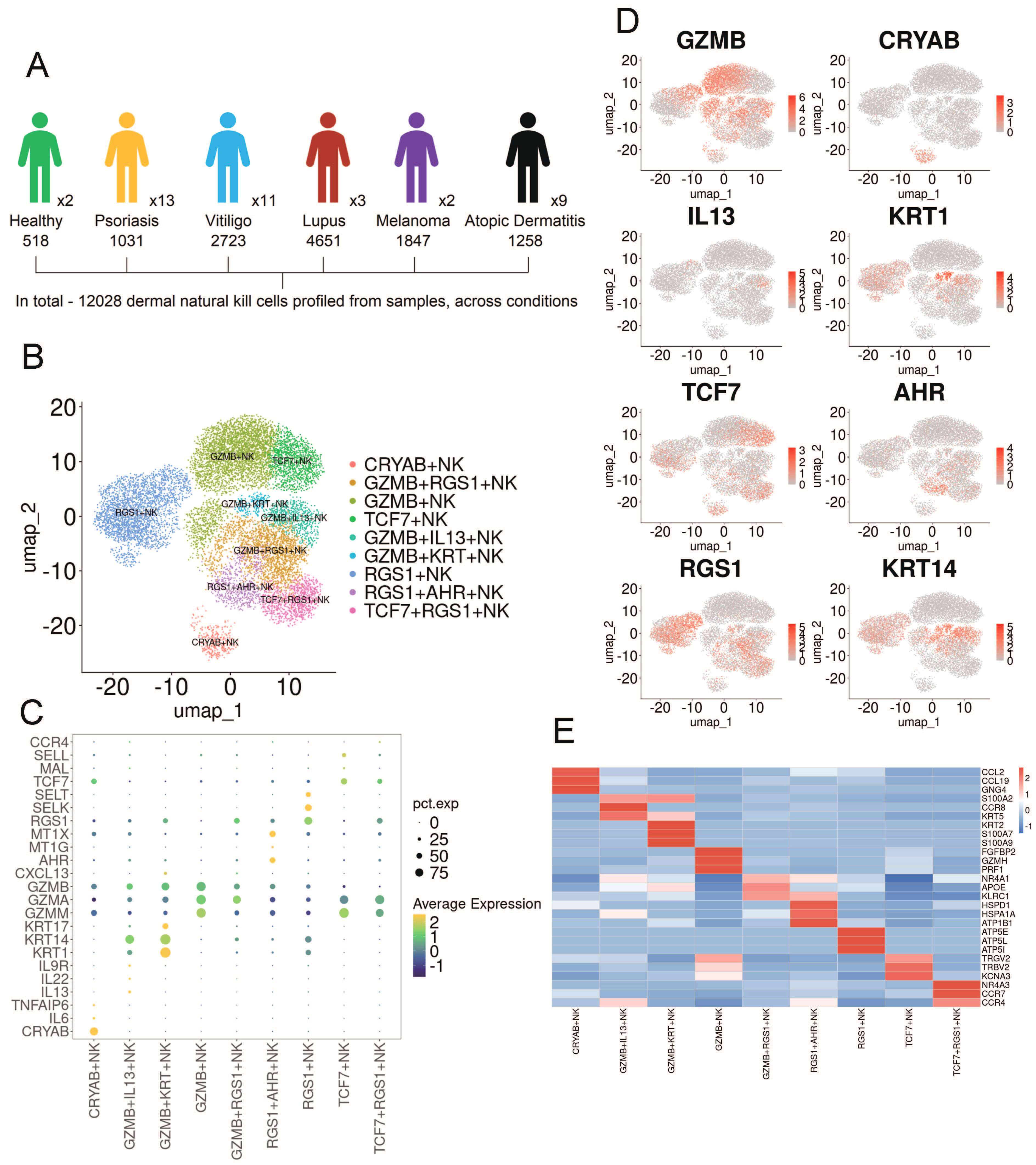

To investigate the heterogeneity of skin-resident natural killer cells, we collected publicly available single-cell transcriptomic datasets comprising 40 skin samples across six skin conditions, including healthy skin [16] (n = 2), psoriasis [17, 18, 19] (n = 13), atopic dermatitis [15, 20] (n = 9), lupus [21, 22] (n = 3), melanoma [24] (n = 2), and vitiligo [16, 23] (n = 11). A total of 12,028 NK cells were identified from the 40 integrated samples for subsequent analysis (Fig. 1A). Subclustering analysis revealed that NK cells from healthy individuals and patients with various skin diseases were grouped into nine distinct subsets, all exhibiting high expression of NK cell lineage–associated genes (Fig. 1B,C). Based on the analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), these subsets were identified and annotated using established canonical markers, including GZMB+, GZMB+ IL13+, GZMB+ Regulator of G-protein signaling 1 (RGS1)+, GZMB+ Keratin (KRT)+, RGS1+AHR+, Transcription factor 7 (TCF7)+, TCF7+RGS1+, RGS1+ and Crystallin Alpha B (CRYAB)+ NK cells (Fig. 1D,E).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq) analysis reveals the heterogeneity of NK cells in human skin diseases. (A) Schematic workflow of single-cell RNA sequencing analysis. (B) UMAP embedding shows nine NK cell clusters derived from 12,028 cells across six skin conditions. (C) Dot plot displaying the expression of NK cell–related genes and lineage-specific markers in the skin. (D) Density plot illustrating representative markers for each NK cell subset. (E) Heatmap depicting distinct marker genes for each NK cell cluster. NK, natural killer; UMAP, Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection.

We next examined the distribution of these NK cell subsets in various skin diseases. Their abundance, visualized through 2D embeddings and bar plots, varied significantly across conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1). Notably, GZMB+ NK cells were present in PSO and also exhibited a certain level of expression in AD, which is consistent with previous reports [25]. GZMB+IL13+ NK cells were predominantly found in AD. In melanoma, all NK cells expressed RGS1, which is a marker associated with the prognosis of melanoma [26, 27]. High expression of RGS1 indicates a poor prognosis for melanoma [28]. TCF7+ NK cells are primarily expressed in lupus. Previous studies have identified TCF7 as a susceptibility locus for lupus [29]. Furthermore, RGS1+ NK cells were found to be unique to vitiligo. These results collectively highlight the dynamic and diverse phenotypic changes of NK cells in the progression of various skin disorders.

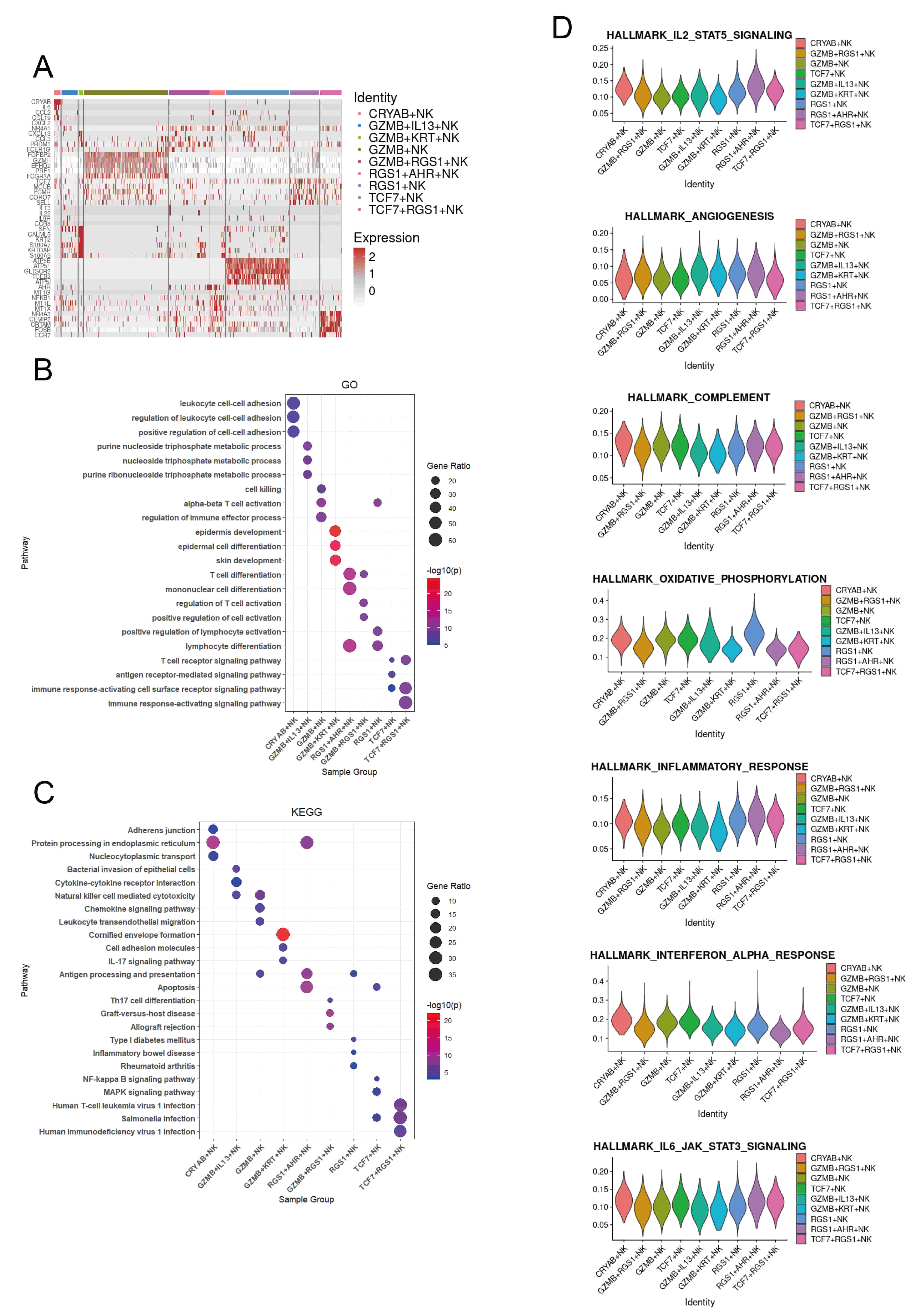

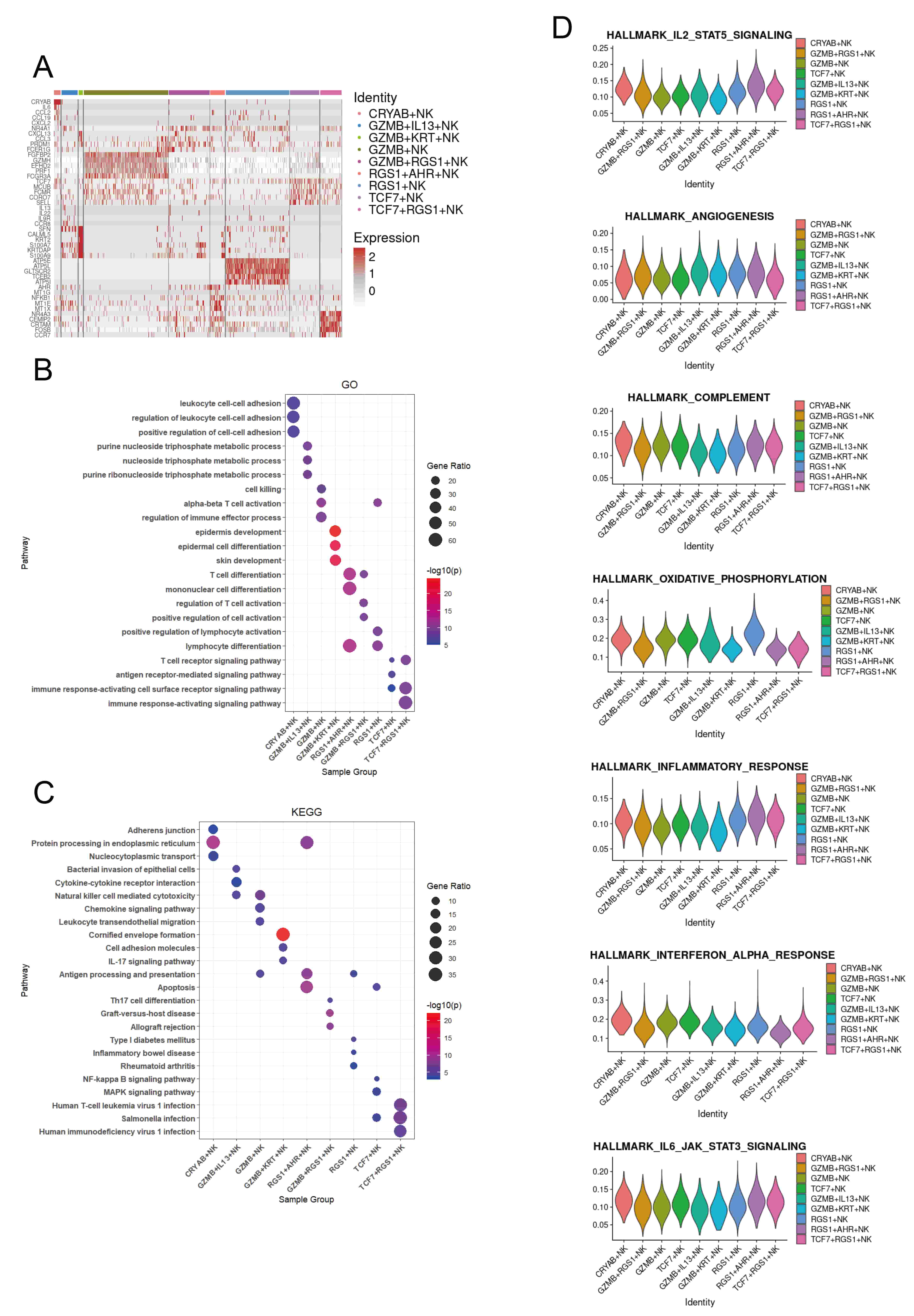

To assess the functional characteristics of different NK cell subsets, we identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for each subset (Fig. 2A). CRYAB+, GZMB+, GZMB+RGS1+, GZMB+IL13+, TCF7+RGS1+, and TCF7+ NK cells show upregulation of genes related to immune response, including immune cell chemotaxis (CCL2, CCL19, CXCL2, CXCL13, CCL3, CCR8, SELL, CCR7), lymphocyte development, differentiation, and activation (TCF7, PRDM1, NR4A1, FCER1G, FCMR), and cytotoxicity (FGFBP2, GZMH, PRF1, FCGR3A, CRTAM, EFHD2). GZMB+IL13+ NK cells also express a variety of cytokines (IL13, IL22), which are associated with the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. GZMB+KRT+ NK cells express genes associated with epidermal cells (CALML5, KRT2, S100A7, KRTDAP). RGS1+ and RGS1+AHR+ NK cells are associated with stress and metabolism (MT1G, MT1E, MT1X, ATP5E, ATP5L, ATP5I) (Fig. 2A,B). These findings suggest that CRYAB+, GZMB+, GZMB+RGS1+, GZMB+IL13+, TCF7+RGS1+, and TCF7+ NK cells may exhibit pro-inflammatory properties, thereby promoting skin inflammation. In addition, the GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of the selected DEGs indicated that GZMB+KRT+ NK cells are associated with the IL17 signaling pathway, while GZMB+RGS1+ NK cells are related to Th17 cell differentiation, which are respectively immune and differentiation pathways related to the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Meanwhile, GZMB+IL13+ NK cells are associated with the pathway of Bacterial invasion of epithelial cells, which may be related to the impaired skin barrier in atopic dermatitis. CRYAB+ NK cells are associated with cell-to-cell junctions, while RGS1+AHR+ NK cells are related to antigen processing and presentation. RGS1+ is associated with various autoimmune diseases, TCF7+ is mainly related to multiple signaling pathways, while TCF7+RGS1+ is primarily associated with various pathogen infections. In addition, GZMB+ NK cells are associated with chemotaxis, which may be related to the inflammatory response in the skin of psoriasis (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Transcriptional programs of the NK cell subsets in the human skin NK cell atlas. (A) Key genes for each NK cell subset across six skin conditions. (B) Top Gene Ontology (GO) pathways enriched in the top 100 upregulated genes in each subset, based on average log2 fold change versus other skin NK cell subsets. (C) Top Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways enriched in the top 100 upregulated genes in each subset. (D) Violin plots showing AUCell scores for subset-specific gene sets in each NK cell cluster.

To confirm the immune roles of NK cells, we evaluated their cytokine response profiles using area under the curve (AUC) analysis (Fig. 2D). Our results indicate that RGS1+ NK cells exhibit elevated oxidative phosphorylation activity, while GZMB+ and TCF7+ NK cells are associated with the complement system (Fig. 2D).

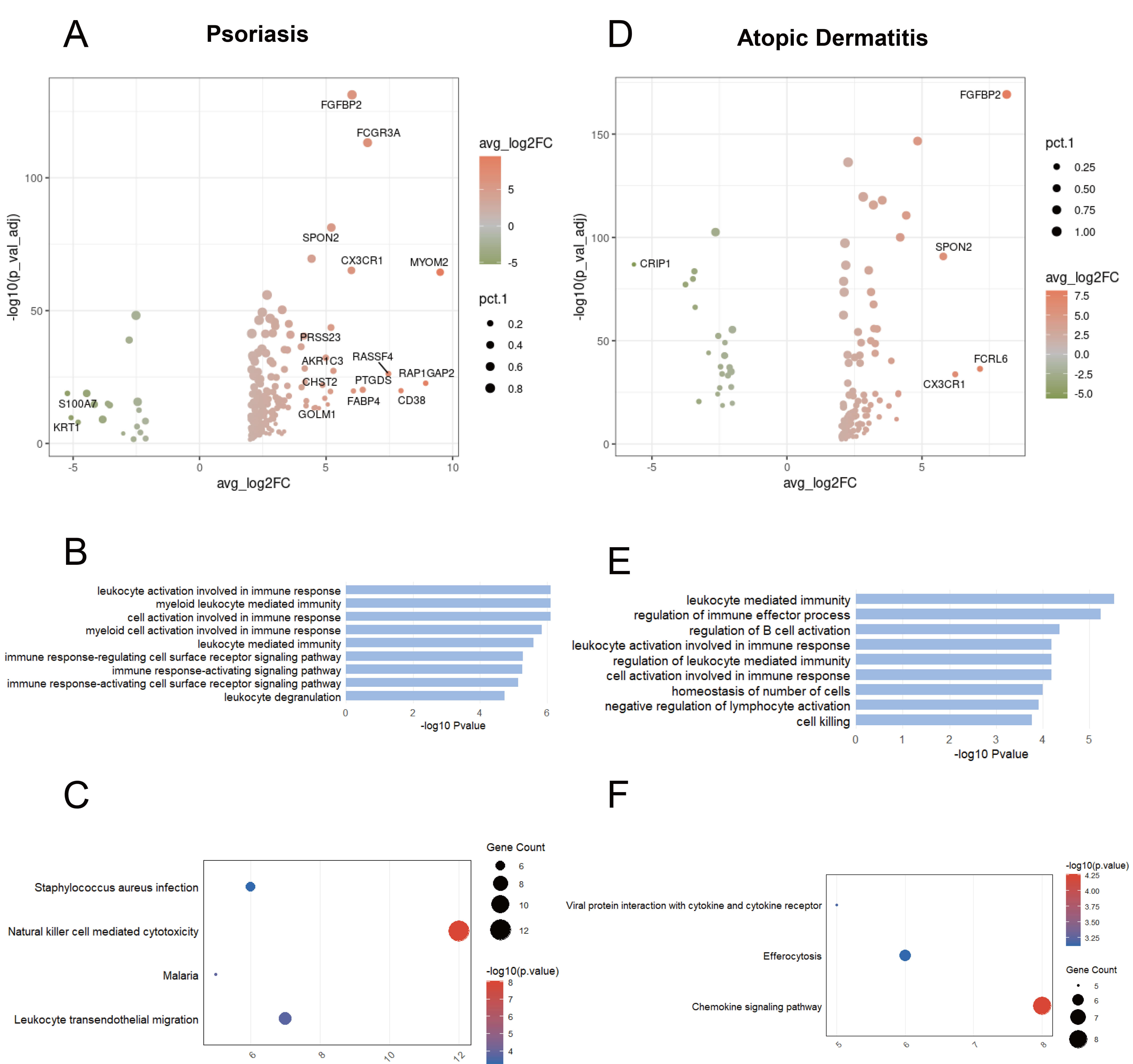

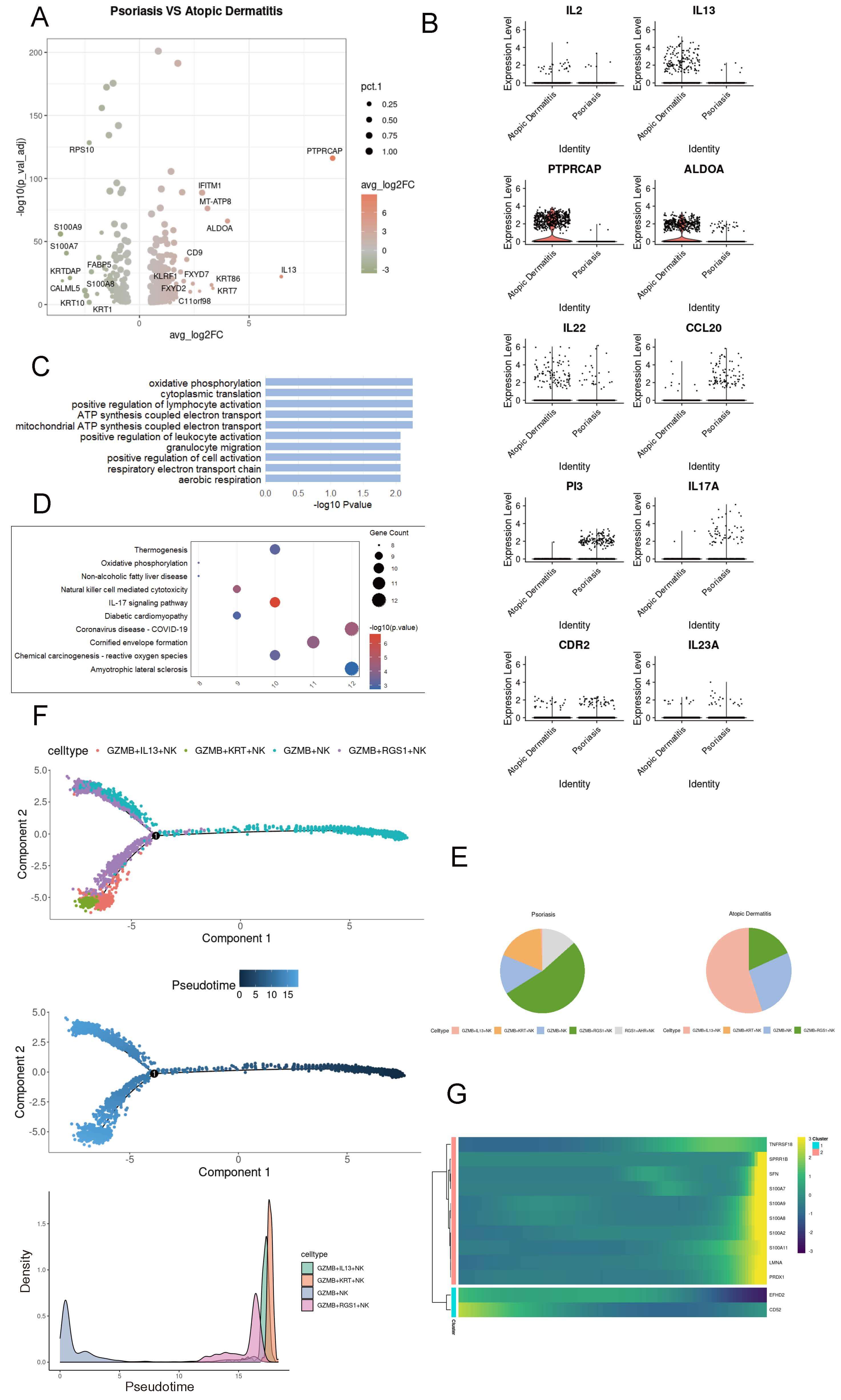

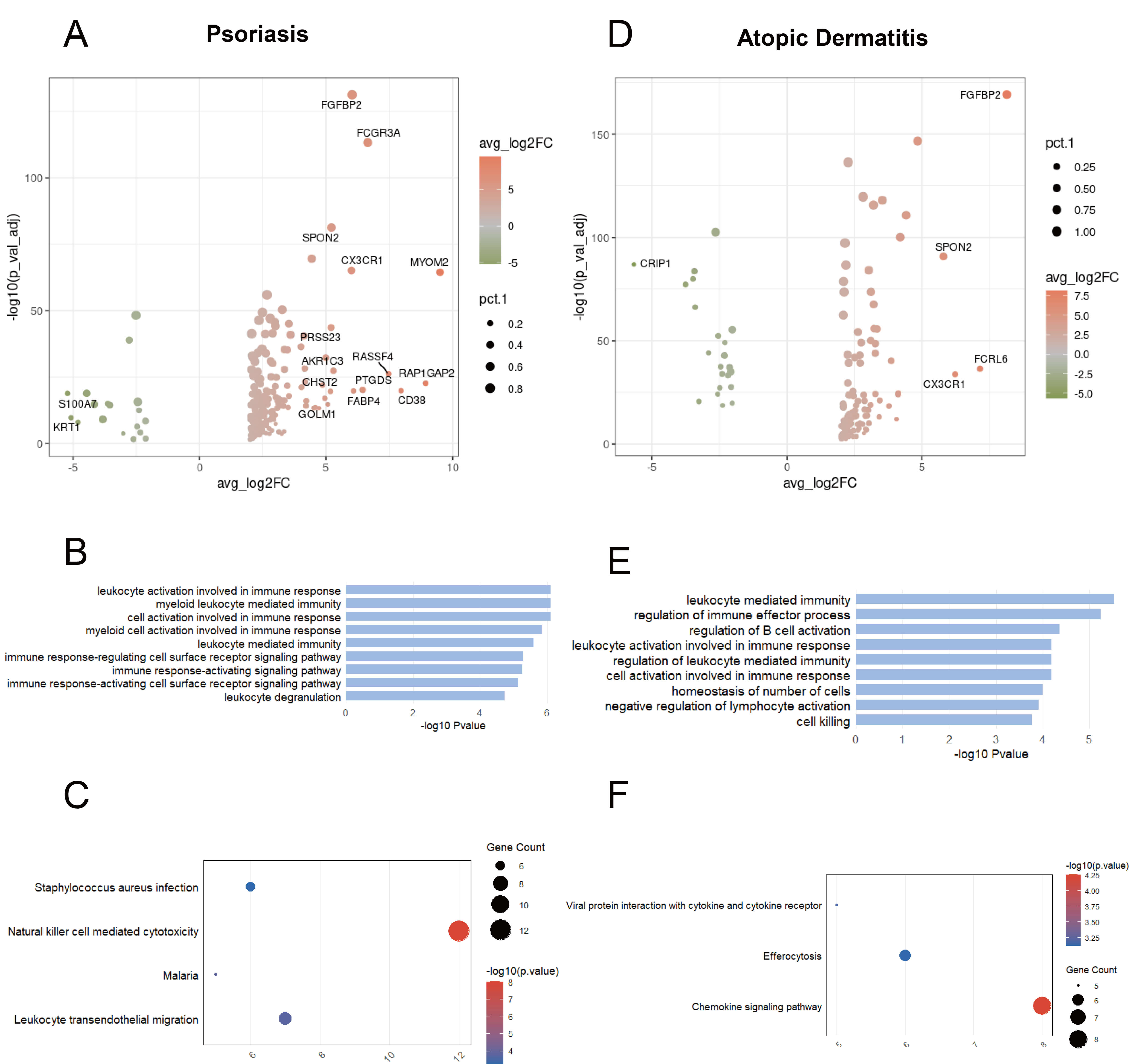

We further examined whether these cells adopt distinct transcriptional programs to promote inflammation in each disease. In psoriasis, GZMB+ NK cells show upregulation of genes associated with lymphocyte migration (e.g., CX3CR1, SPON2, CHST2) (Fig. 3A). The GO-enriched pathways are associated with the activation and effector functions of immune cells (Fig. 3B). KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that in psoriasis, GZMB+ NK cells retained the NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity signature and were involved in the infection process of pathogens and the migration of leukocytes across the endothelium (Fig. 3C). In atopic dermatitis, GZMB+ NK cells express genes associated with cell metabolism (e.g., AKR1C3, ODC1, GCLM) and cell proliferation and differentiation (e.g., ZEB2, LYAR) (Fig. 3D). The GO-enriched pathways are associated with immune response, negative regulation of lymphocyte activation, and cell killing (Fig. 3E). KEGG enrichment analysis indicated involvement in the Chemokine signaling pathway, Viral protein interaction with cytokine and cytokine receptor, and Efferocytosis (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Transcriptional changes of GZMB+ NK cells shared between psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. (A) Volcano plot showing DEGs between GZMB+ NK cells and other cells in psoriasis. (B) Bar chart showing GO-enriched pathways of DEGs between GZMB+ and other cells in psoriasis. (C) Dot plot showing KEGG pathways of DEGs between GZMB+ and other cells in psoriasis. (D) Volcano plot illustrating DEGs between GZMB+ NK cells and other cells in atopic dermatitis. (E) Bar chart showing GO-enriched pathways of DEGs between GZMB+ and other cells in atopic dermatitis. (F) Dot plot showing KEGG pathways of DEGs between GZMB+ and other cells in atopic dermatitis.

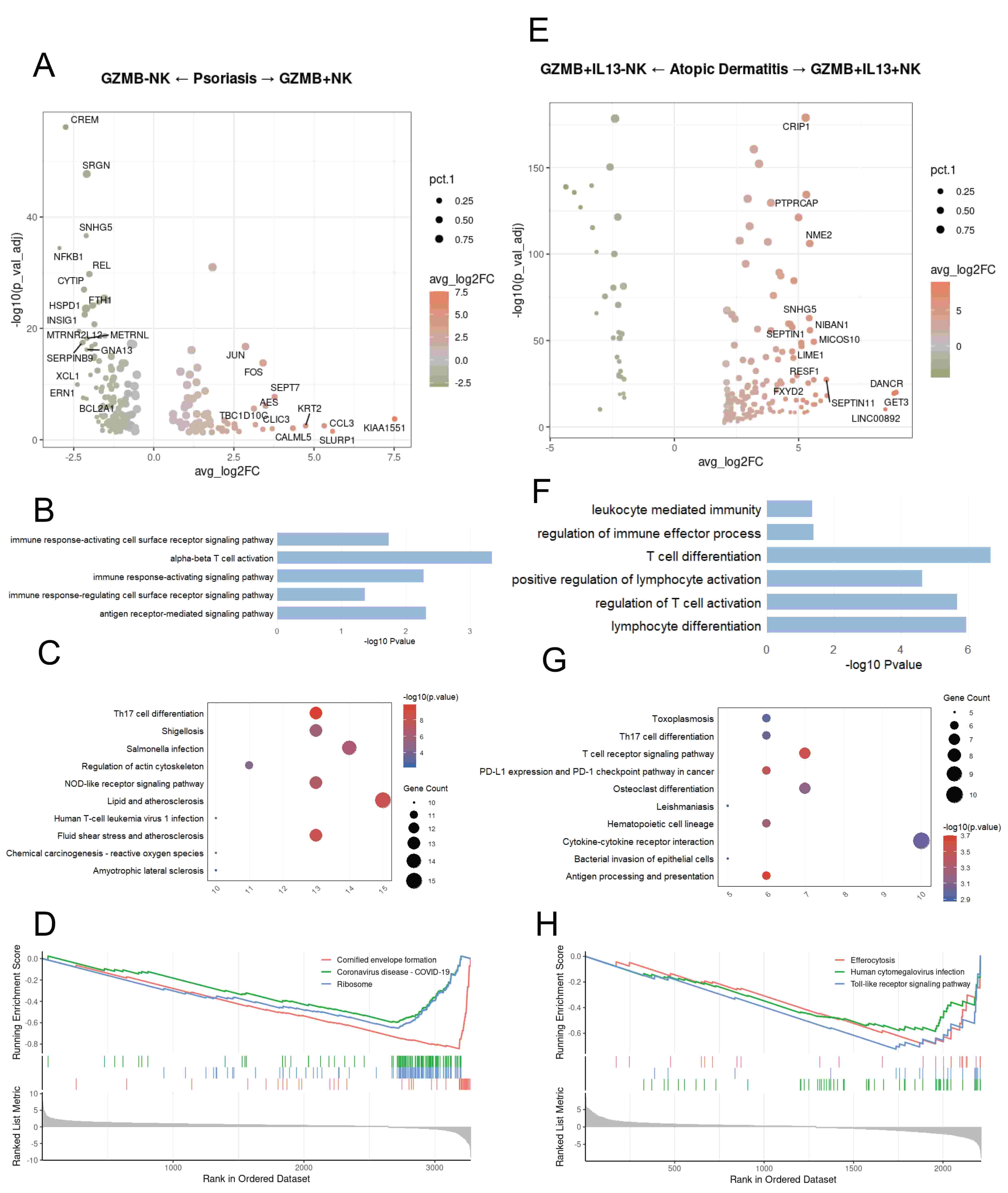

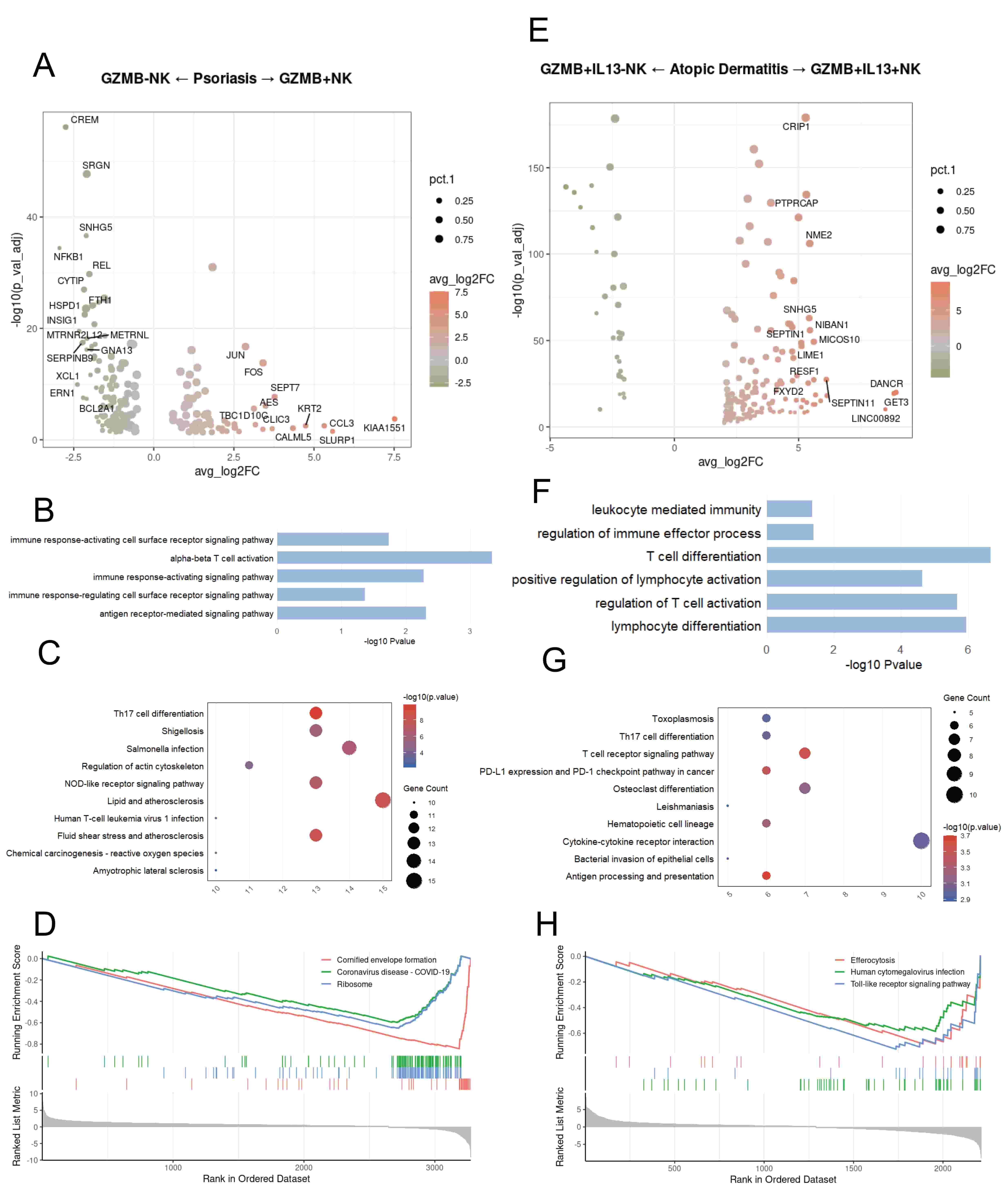

In psoriasis, NK cells expressing GZMB show upregulation of genes associated with cell motility (e.g., pFN1, CFL1) and chemotaxis (e.g., CCL3, CCL4, CCL5) (Fig. 4A). GO enrichment analysis revealed pathways involved in various immune signaling and immune activation (Fig. 4B). KEGG analysis based on the selected DEGs showed that in psoriasis, NK cells expressing GZMB are functionally enriched in Th17 cell differentiation and Lipid and atherosclerosis (Fig. 4C). GSEA enrichment analysis revealed that in psoriasis, NK cells not expressing GZMB show upregulation of the Cornified envelope formation, Coronavirus disease-COVID-19, and Ribosome pathways (Fig. 4D). GZMB+IL13+ NK cells show upregulation of genes associated with cell metabolism (e.g., ALDOA, EEF1G) and mitochondrial-related functions (e.g., MICOS10, MICOS13) (Fig. 4E). In atopic dermatitis, GZMB+IL13+ NK cells are associated with GO pathways related to T-cell activation and lymphocyte differentiation (Fig. 4F). KEGG analysis based on the selected DEGs showed that in atopic dermatitis, IL13+ NK cells are functionally enriched in the Bacterial invasion of epithelial cells pathway and various receptor pathways (Fig. 4G). Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) revealed that in atopic dermatitis, GZMB+IL13– NK cells are enriched in the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, Human cytomegalovirus infection, and Efferocytosis pathways (Fig. 4H).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Disease-related functional differences of Granzyme B (GZMB)+ NK cells between psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. (A) Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between psoriasis NK cells expressing GZMB and those not expressing GZMB. (B) Bar chart showing GO-enriched pathways of DEGs between NK cells expressing GZMB and those not expressing GZMB in psoriasis. (C) Dot plot showing KEGG pathways of DEGs between NK cells expressing GZMB and those not expressing GZMB in psoriasis. (D) GSEA enrichment plot showing representative pathways enriched in psoriasis NK cells expressing GZMB and those not expressing GZMB. (E) Volcano plot illustrating DEGs between GZMB+IL13+ NK and GZMB+IL13– NK cells in atopic dermatitis. (F) Bar chart showing GO-enriched pathways of DEGs between GZMB+IL13+ NK and GZMB+IL13– NK cells in atopic dermatitis. (G) Dot plot showing KEGG pathways of DEGs between GZMB+IL13+ NK and GZMB+IL13– NK cells in atopic dermatitis. (H) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) enrichment plot showing representative pathways enriched in GZMB+IL13+ NK and GZMB+IL13– NK cells in atopic dermatitis.

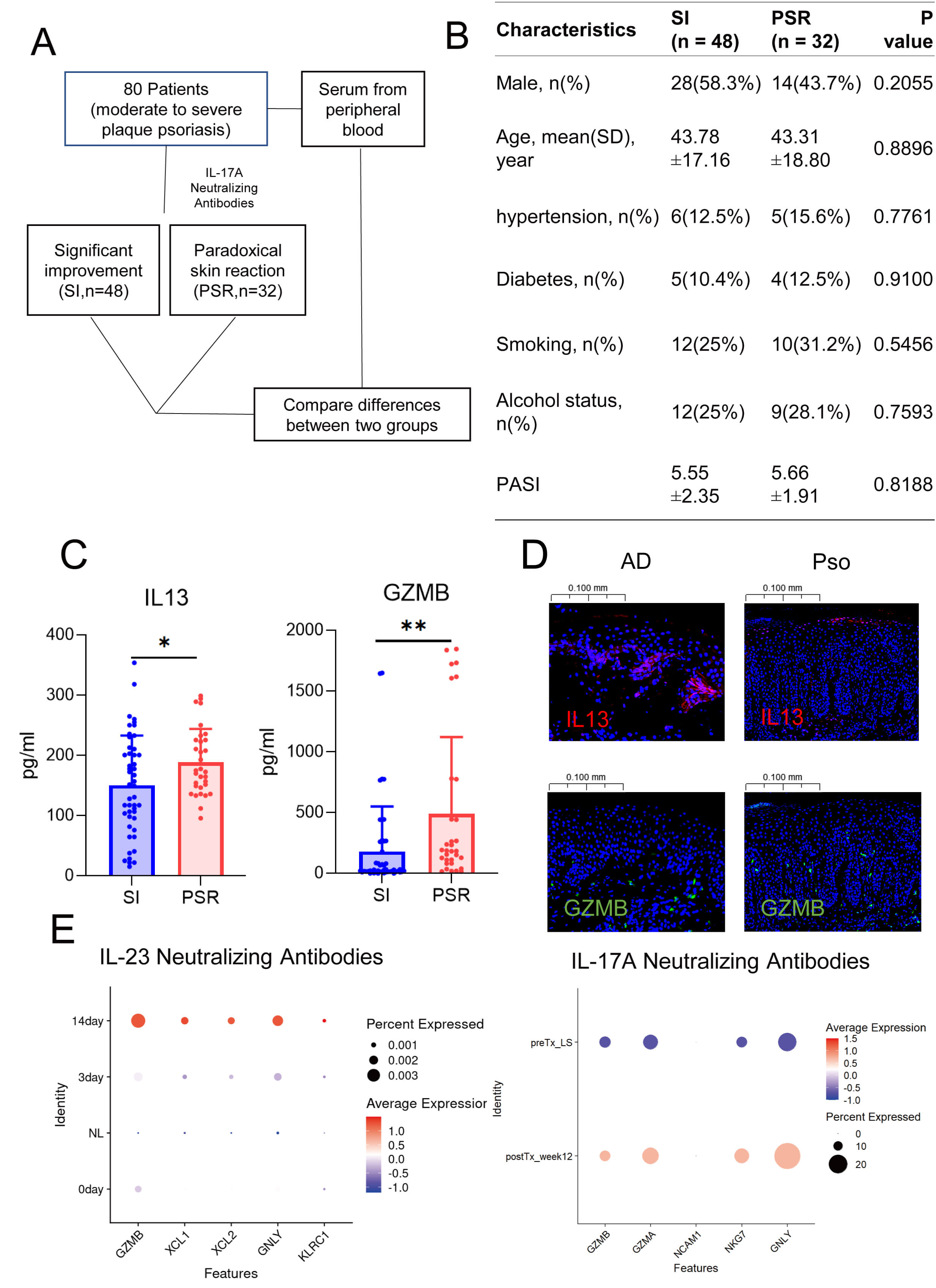

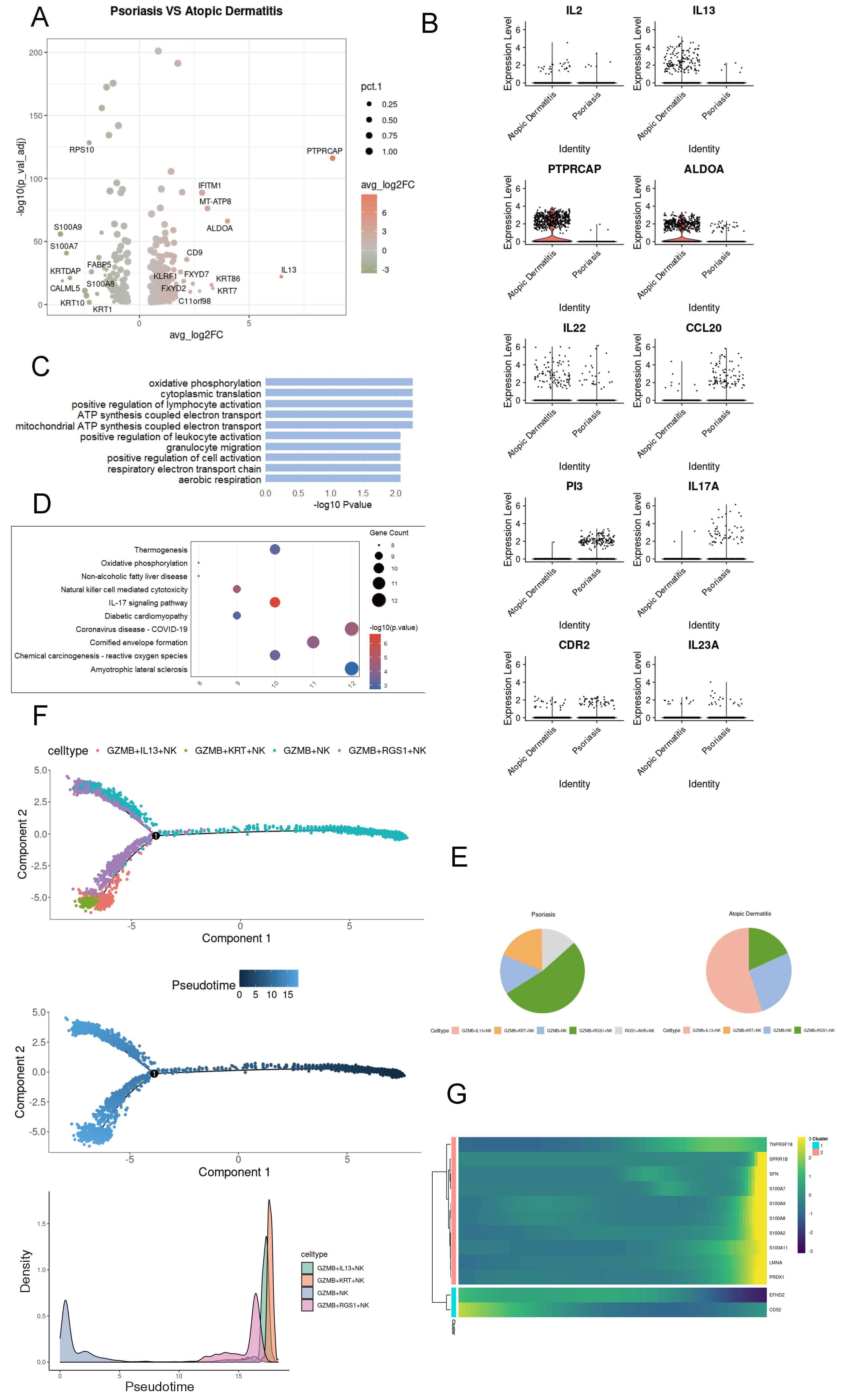

Psoriasis and atopic dermatitis exhibit high complexity; in atopic dermatitis, cytokines such as IL13, IL2, and IL22 are significantly elevated (Fig. 5A,B). Psoriasis is mainly enriched in pathways related to cell metabolism (Fig. 5C). In addition, KEGG analysis based on the selected DEGs showed that psoriasis is associated with the IL17 signaling pathway (Fig. 5D). Among the changes in the proportions of NK cell subpopulations in the two diseases, the most significant differences were observed in GZMB+ NK cells and GZMB+IL13+ NK cells (Fig. 5E). Pseudotime analysis indicated that the GZMB+ NK cell population could exhibit the expression of RGS1 during the differentiation process, but ultimately would show the expression of IL13 (Fig. 5F). During the simulated differentiation process, genes associated with the inflammatory response in atopic dermatitis (such as the S100 protein family) and genes related to immune regulation (TNFRSF18) were upregulated, which may contribute to the development of paradoxical reactions during psoriasis treatment (Fig. 5G). Taken together, GZMB+ NK cells in psoriasis patients may gradually differentiate to express the cytokine IL13, thereby promoting the development of paradoxical reactions.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Dynamic transcriptional features of GZMB+ NK cells in psoriasis. (A) Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in NK cells between psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. (B) Heatmap illustrating gene expression profiles of NK cells in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. (C) Bar plot showing Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment pathways of NK cell DEGs in psoriasis. (D) Dot plot presenting KEGG enrichment pathways of NK cell DEGs in psoriasis. (E) Pie chart illustrating the proportion of NK cell subsets in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. (F) Pseudotime trajectory analysis of NK cells across six skin conditions using Monocle2; lines represent inferred cellular trajectories. (G) Heatmap showing dynamic changes in gene expression during the differentiation of GZMB+ NK cells.

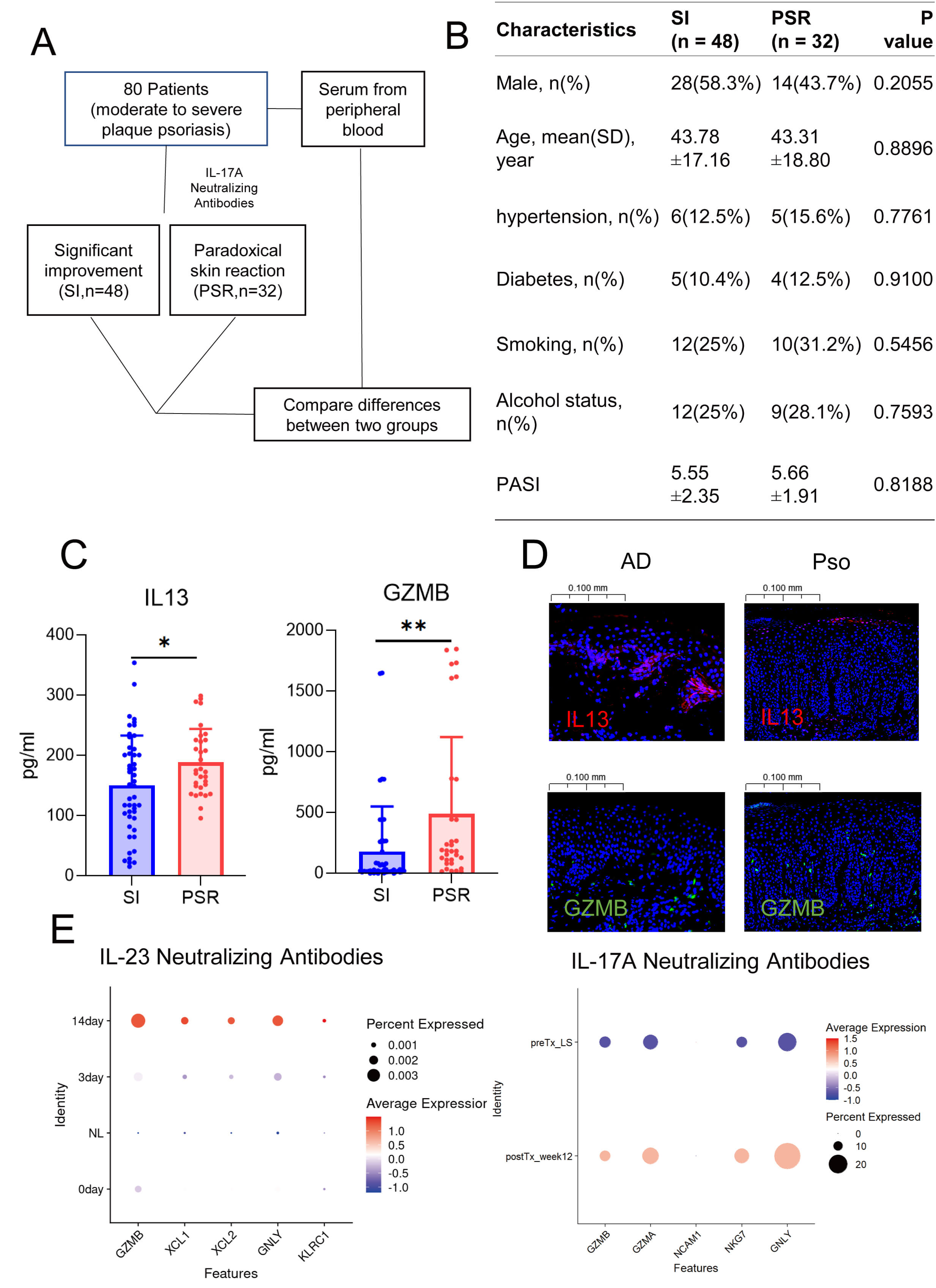

To verify our hypothesis, we conducted a retrospective study on samples from patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis who were treated with IL17A inhibitors. We identified 48 patients whose symptoms improved significantly and 32 who experienced paradoxical reactions (Fig. 6A,B). Our findings revealed substantially higher levels of GZMB and IL13 in the peripheral blood of patients with paradoxical reactions than in the control group (Fig. 6C). Immunofluorescence studies also validated the increased expression of GZMB in psoriasis and IL13 in atopic dermatitis (AD) (Fig. 6D). Moreover, both GZMB and IL13 signals were detected in the dermis and at the dermoepidermal junction in both conditions, implying a possible transformation between the two NK cell phenotypes. By analyzing the public single-cell transcriptomic data of psoriasis patients treated with biologics, such as IL17 and IL23 inhibitors, we observed an upregulation of GZMB expression post-treatment [17, 30] (Fig. 6E), which is consistent with our finding from the analysis of public databases that the proportion of GZMB is higher in atopic dermatitis than in psoriasis. In short, as psoriasis evolves into paradoxical reactions, GZMB+ NK cells might begin to express IL13, thereby playing a role in the development of these reactions.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Characteristics of natural killer cells in patients with

paradoxical reactions. (A) Schematic diagram illustrating the workflow of

clinical sample collection. (B) Baseline characteristics of patients with

significant remission versus those who developed paradoxical reactions. (C) ELISA

results showing the differential levels of GZMB and IL13 in

patients with remission and those with paradoxical reactions. The blue axis is significant improvement (SI), and the red axis is paradoxical skin reaction (PSR). (D) Dot plots

displaying changes in NK cell gene expression following treatment with IL23

inhibitors and IL17 inhibitors in patients with paradoxical reactions. (E)

Immunofluorescence staining showing the abundance of GZMB+ and IL13+

cells in lesional tissues of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. *, p

This study aimed to identify shared transcriptional features among inflammatory skin diseases to elucidate skin NK cell classification. By using canonical markers, we successfully identified nine NK cell subgroups, which can aid future exploration of the role of NK cells in skin diseases. It is worth noting that NK cells with different markers may exhibit diverse pathogenic effects across various diseases. Other studies have also shown that there are multiple NK cell subgroups in the skin under different pathological conditions and that these subgroups undergo dynamic changes [31]. Future research should further refine the classification of skin NK cells and delve into their pathogenic mechanisms in various skin diseases.

Granzyme B (GzmB), a serine protease, cleaves structural proteins including intercellular connections, basement membranes, and cell surface receptors [11]. In healthy skin, GzmB is scarce or absent; however, its levels are significantly elevated in blistering diseases [32], atopic dermatitis, psoriasis [33], systemic sclerosis, and vitiligo [11]. A study by Fenix et al. [34] demonstrated that in resolved psoriasis, CD49+ Trm cells exhibited significantly increased production of GzmB. Based on this, the authors speculated that GzmB may be associated with psoriasis relapse. GzmB promotes the development of AD by impairing epithelial barrier function through the cleavage of E-cadherin and filaggrin (FLG) [35].

IL13 signaling via STAT6 impairs skin barrier integrity by suppressing both filaggrin expression and antimicrobial peptide (AMP) production, both critical for defense and microbial homeostasis [36]. Atopic dermatitis (AD) is traditionally defined by a type 2 immune response, notably through IL4 signaling [37]. However, emerging evidence identifies IL13 as the dominant inflammatory cytokine in AD [38, 39, 40]. Therapeutic agents targeting IL13 and IL4 (e.g., Dupilumab) or specifically IL13 (e.g., Tralokinumab) have demonstrated notable efficacy in moderate-to-severe AD, improving skin lesions, pruritus, psychological symptoms, and quality of life [41, 42, 43]. In this study, we built a single-cell atlas of NK cells in human inflammatory skin diseases and identified GZMB+ NK cells as key players in PSO, where they correlate with Th17 cell differentiation. Additionally, we found that IL13+ NK cells played a significant role in AD, with their function linked to multiple receptor pathways.

In recent years, the use of biologics has become increasingly widespread. Some

patients receiving biologic therapy develop so-called “paradoxical reactions”,

referring to the emergence of new immune-mediated diseases after initiating

treatment. There have been reports of patients developing eczematous lesions

during IL17 inhibitor therapy for psoriasis. [44, 45]. However, the underlying

mechanisms of paradoxical reactions remain unclear. Current studies suggest that

they may be associated with shifts in T cell polarization—PSO is primarily

driven by Th1 and Th17 cells, whereas AD is driven by Th2 cells. When IL17A

inhibitors suppress Th17 cells, this may lead to a repolarization toward Th2

cells, potentially triggering paradoxical reactions [46, 47]. In this study, we

treated patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis using IL17A inhibitors

and selected 48 patients who showed significant symptom relief, along with 32

patients who developed paradoxical reactions. Pre-treatment serum ELISA results

showed that patients who developed paradoxical reactions had significantly

elevated levels of GZMB and IL13 compared to the control group.

Immunofluorescence revealed that both GZMB and IL13 were

present at the dermoepidermal junction in psoriasis and AD, providing spatial

support for potential phenotypic transition between the two. Pseudotime analysis

further suggested that GZMB+ NK cells may differentiate into

GZMB+IL13+ NK cells. In our study, we also found that the expression of

GZMB was upregulated following biologic treatment, which is consistent

with our analysis of public databases showing that the proportion of cells

expressing GZMB is higher in atopic dermatitis than in psoriasis. In

conclusion, after biologic treatment, GZMB+ NK cells may differentiate into

IL13+ NK cells, which may contribute to the development of paradoxical

reactions. However, other study suggests that the expression of TNF,

IFN-

A reduced number of NK cells in the blood is a notable feature of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD). An NK cell enhancer—interleukin-15 (IL15) superagonist—has been identified; IL15 is a crucial cytokine that plays a key role in the proliferation, activation, and survival of NK cells. In AD mouse models, IL15 superagonists significantly improved AD-like symptoms, including reduced skin thickness, diminished erythema, and decreased scaling [50]. Therefore, monitoring and regulating NK cells may serve as a valuable biomarker for predicting and managing paradoxical reactions in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

Our comprehensive single-cell atlas characterizes cutaneous NK cell heterogeneity, providing a resource for future research. Moreover, we found that the proportion of GZMB expression was higher in atopic dermatitis than in psoriasis, while the expression proportion of IL13 was significantly higher than that in psoriasis. Meanwhile, we also found that GZMB+NK cells may be able to differentiate into GZMB+IL13+NK cells, which may contribute to the development of paradoxical reactions. Our findings reveal the pathogenic roles of cutaneous NK cells and offer new strategies for the treatment of paradoxical reactions in the future.

Of course, the original study also has certain limitations. First, due to the complexity of cells, the limitations of single-cell sequencing, and the potential loss of NK cells during the grinding and single-cell sequencing processes, we are unable to comprehensively analyze all NK cells in the skin. Second, in inferring the differentiation of GZMB+NK cells into IL13-producing NK cells, we have only provided indirect evidence from immunofluorescence and serum samples, which to some extent affects the translational value of the article.

This study used single-cell RNA sequencing to classify 9 types of NK cells and discussed their potential roles in various skin diseases. Through pseudotime trajectory analysis, it was revealed that GZMB+NK cells may be able to differentiate into GZMB+IL13+NK cells. Given that psoriasis is associated with the cytokine GZMB and atopic dermatitis with both GZMB and IL13, these findings provide clues to the possible pathogenesis of paradoxical skin diseases.

The single-cell datasets used in this study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and the Genome Sequence Archive (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/). The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conceptualization, JS, CD and JD; Data curation, JS, YW and CD; Analysis data, JS, YW, LL, XZ and CD; Funding acquisition, JD; Investigation, XL and JZ; Supervision, JD; Writing—original draft, JS. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All patients or their guardians provided written informed consent prior to involvement. The study protocol adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki principles and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Huashan Hospital, Fudan University (approval number 2020-1202).

We thank all those who helped in the writing of this manuscript and acknowledge all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC2508103), the Clinical Research Plan of SHDC (grant numbers: SHDC2020CR6022 and SHDC22022302).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Artificial intelligence and AI-assisted technologies were employed during the writing of this study solely for the purposes of language refinement and enhancing the readability of the manuscript. These tools did not replace any essential research tasks. Their use was conducted under human supervision and control, and the authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited the output to ensure accuracy and integrity.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL47056.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.