1 Herbal Medicine Resources Research Center, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, 58245 Naju-si, Republic of Korea

2 IU Eye Clinic, Ophthalmology Practice, 05606 Seoul, Republic of Korea

3 Mediverse Co., Ltd., 06616 Seoul, Republic of Korea

4 Central R&D Center, B&Tech Co., Ltd., 58205 Naju, Republic of Korea

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Ultraviolet B (UVB) irradiation is a major environmental factor causing corneal epithelial cell apoptosis, leading to ocular surface damage and vision impairment.

This study aimed to investigate whether the standardized extract of Peucedanum japonicum Thunb. (SBP) protects corneal cells from UVB-induced apoptosis and explore its mitochondrial regulatory mechanisms.

Corneal epithelial cells were exposed to UVB irradiation, with or without treatment with SBP extract or its fractions. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase activity, mitochondrial membrane potential, and mitochondrial morphology were assessed, and apoptosis-related proteins were analyzed using a cytokine antibody array kit. In vivo mouse models were also used to evaluate corneal damage following UVB exposure.

The SBP extract, particularly the n-butanol (n-BuOH) fraction, significantly attenuated UVB-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and reduced apoptosis. Treatment restored mitochondrial membrane potential and improved corneal morphology in UVB-exposed mice. Chlorogenic acid, a major active compound, exhibited similar protective effects. The n-BuOH fraction demonstrated protective effects comparable to those of chlorogenic acid.

SBP protects corneal cells from UVB-induced apoptosis through mitochondrial stabilization, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic agent for ocular surface disorders.

Keywords

- peucedanum japonicum

- apoptosis

- corneal diseases

- ultraviolet rays

- mitochondria

Ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation is among the most harmful environmental eye stressors [1, 2]. Cornea is the most anterior and directly exposed tissue and acts as the primary barrier against ultraviolet light; nonetheless, it is also highly vulnerable to phototoxic damage [1]. Repeated or acute UVB exposure results in excessive reactive oxygen species production, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptotic pathway activation in corneal epithelial cells, potentially leading to the loss of epithelial cells, corneal opacity, and impaired vision [1]. Clinically, UV-induced keratitis and progressive ocular surface disorders are significant public health concerns, especially in populations with high sunlight exposure or occupational risks [2]. Nevertheless, effective therapeutic strategies for preventing or attenuating UVB-induced corneal apoptosis remain limited.

Previous approaches have largely focused on antioxidant supplementation or topical formulations using well-known compounds, such as vitamin C, vitamin E, or plant-derived flavonoids [3]. Although these agents exhibit some efficacy, their clinical utility is often restricted by their instability, limited bioavailability, and insufficient potency to counteract severe oxidative stress [3]. Therefore, identifying natural compounds with potent antioxidant activity, reliable safety, and strong cellular protective effects is warranted in ophthalmic research.

Peucedanum japonicum Thunb. (SBP) is a medicinal herb widely used in East Asian herbal pharmacology [4]. Historically, it has been used for its antipyretic, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory properties [5]. Phytochemical analyses revealed that SBP contains coumarins, chromones, and phenolic acids that exhibit strong antioxidant capacities and free radical scavenging properties [4, 6]. Recent pharmacological studies have suggested that SBP extract protects against inflammation-induced tissue injury, regulates immune responses, and modulates oxidative stress in different experimental models [5, 6]. Our previous reports demonstrated that it protected ocular tissues from urban particulate matter (UPM)-mediated oxidative stress and mitigated delayed wound healing following blue light irradiation [7, 8]. These studies establish SBP as a potential therapeutic agent for environmentally induced ocular surface damage.

However, its role in preventing UVB-induced corneal epithelial apoptosis, which is mechanistically distinct from UPM- or blue light-mediated oxidative injury, has not yet been systematically addressed. Because mitochondrial dysfunction is a central driver of UVB-induced apoptosis, we assessed whether SBP fractions, particularly the n-butanol (n-BuOH) fraction, could stabilize mitochondrial membrane potential, preserve mitochondrial morphology, and suppress apoptotic signaling in corneal epithelial cells. Additionally, chlorogenic acid, previously identified as a major bioactive component of SBP, was tested in vivo as a reference compound to validate its protective effects.

Dried roots of SBP were provided by B&Tech Co., Ltd. (Naju, Republic of Korea), and a voucher specimen (No. KIOM-SBP or B&T-PJE) was deposited in the herbarium of Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (Daejeon, Republic of Korea). The phytochemical profile of this SBP extract, including all fractions, was previously analyzed and standardized using HPLC in our earlier publication [7, 8]. The same source material was used here.

Human corneal epithelial cells were obtained from Dr. Sunoh Kim, Central R&D Center, B&Tech Co., Ltd., 58205 Naju, Republic of Korea and kept in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The cells were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with SBP or its fraction for 24 h; otherwise, they were pretreated with SBP or its fraction for 1 h, subsequently stimulated with 150 mJ/cm2 UVB for an additional 23 h. All the human corneal epithelial cells used in this study were validated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and tested negative for mycoplasma contamination to ensure authenticity and quality.

Nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide (NADH) dehydrogenase activity was assessed using cell counting kit-8 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) following the instructions of the manufacturer. For cytokine profiling, apoptosis-related proteins were analyzed using a multiplex cytokine antibody array kit according to the protocol of the supplier. Quantitative analyses were completed within 1 month of treatment.

Corneal epithelial cells were cultured on coverslips in 24-well plates and

treated with the indicated concentrations of SBP extract under UVB exposure. For

mitochondrial morphology analysis, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde,

rinsed with PBS, and stained with MitoTracker (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Waltham, MA, USA) for 15 min at room temperature. For the

Male C57BL/6 mice (8-week-old, 23–25 g; Doo Yeol Biotech, Seoul, Korea) were housed under controlled temperature (20–23 °C) and light cycles (12-h light–dark) with free access to food and water. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KIOM: #25-010) and performed in accordance with established guidelines. The mice were randomly divided into six groups (n = 5/group): control, UVB, UVB + SBP 100 mg/kg, UVB + SBP 200 mg/kg, UVB + n-BuOH fraction 50 mg/kg, and UVB + chlorogenic acid 10 mg/kg. The SBP, n-BuOH fractions, and chlorogenic acid were administered orally once daily for 14 consecutive days. On day 15, mice were subjected to a single UVB exposure (375–400 mJ/cm2 for 15 min) using TL20W/12RS UVB lamps (Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands) equipped with ultraviolet C cut filters. The difference in UVB irradiation doses between the in vitro (150 mJ/cm2) and in vivo (375–400 mJ/cm2) settings reflects the distinct physical properties of each model. The in vivo cornea is a multi-layered and curved tissue covered by the tear film, which scatters and partially reflects UVB light; therefore, a higher dose is required to achieve comparable physiological stress. UVB intensity was calibrated before each experiment using a UV radiometer (E202850, Analytik Jena, Upland, CA, USA) to ensure uniform exposure. The irradiation distance was maintained at 20 cm, and radiation uniformity across the exposure field was verified prior to each experiment. To minimize animal suffering, all procedures involving UVB irradiation and tissue collection were performed under anesthesia. Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of Alfaxan (alfaxalone, Dechra Veterinary Products, North Kansas City, MO, USA) and Rompun (xylazine, Bayer Animal Health, Shawnee Mission, KS, USA) at a 3:1 ratio (alfaxalone 30 mg/kg + xylazine 10 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) prior to UVB exposure and before tissue collection. For euthanasia, mice received a terminal overdose (alfaxalone 60 mg/kg + xylazine 20 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) of the same anesthetic mixture followed by cervical dislocation to ensure death, as approved in the institutional protocol. Corneal damage was assessed by fluorescein staining on day 2 after UVB exposure. Following euthanasia, ocular tissues were collected for histological analyses, including hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assays, as previously described (Supplementary Method).

All statistical parameters were calculated using the GraphPad Prism software

(version 5.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are expressed as the

mean

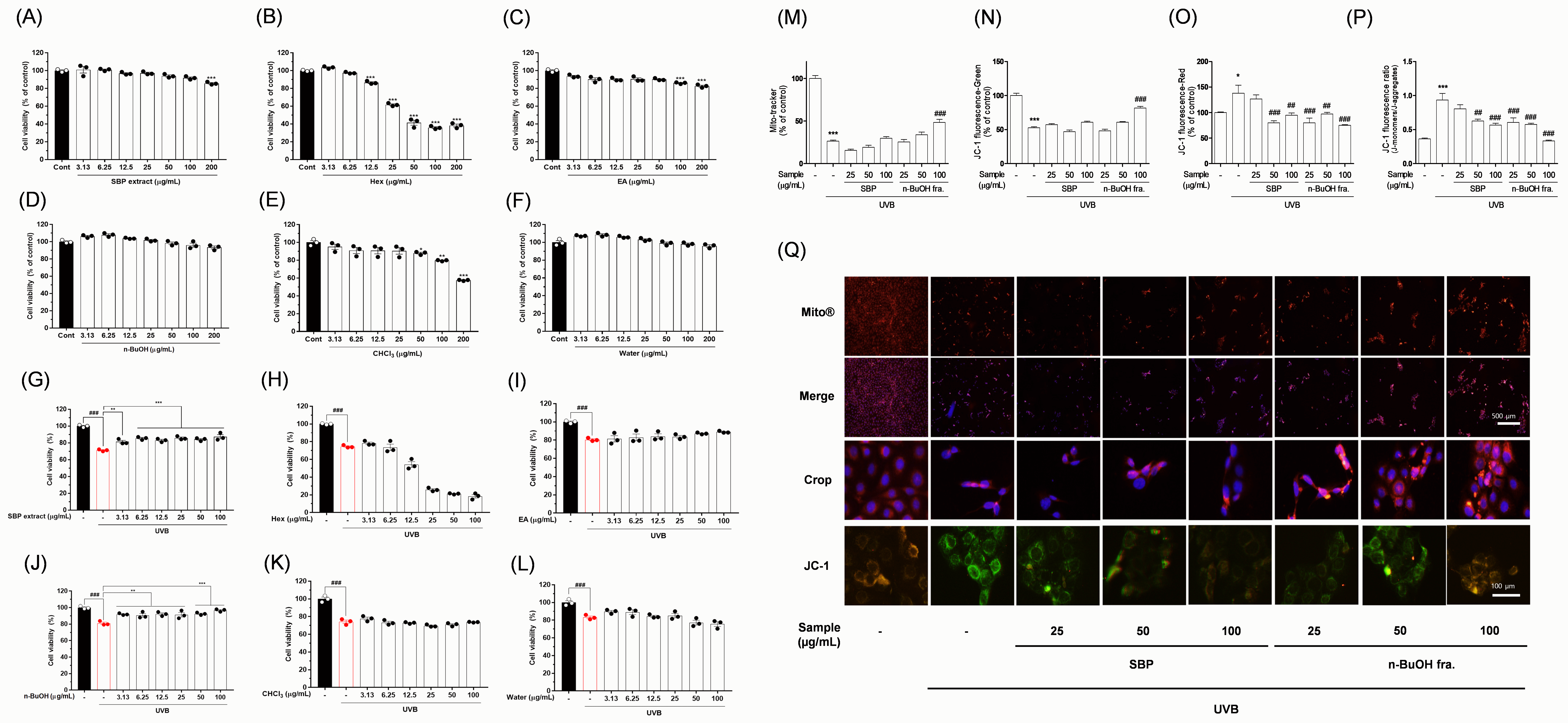

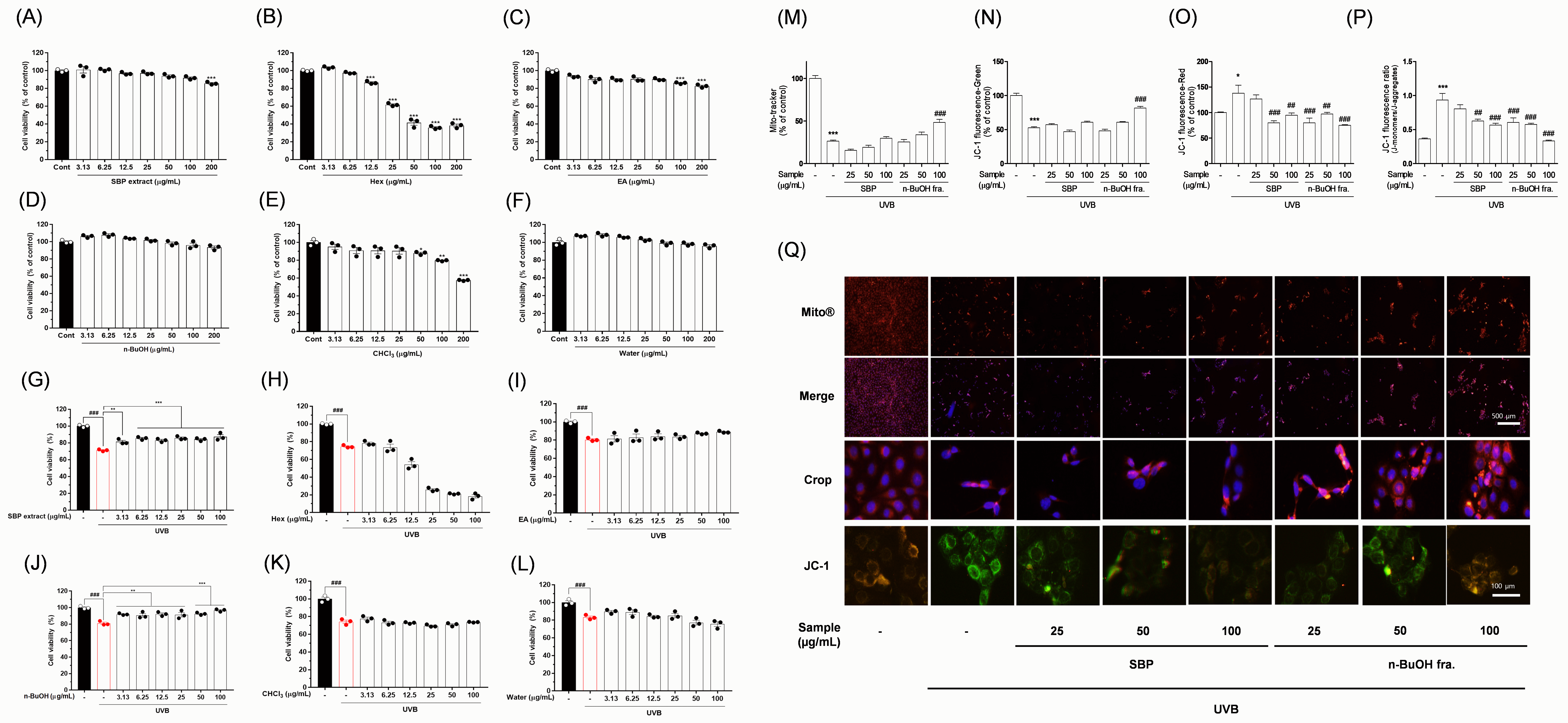

This study demonstrated the anti-apoptotic effect of SBP extract on corneal

epithelial cells, thereby identifying a novel natural substance capable of

protecting the eye from UV-induced damage [1]. These findings provide an

important basis for the development of new therapeutic agents to maintain ocular

health. By elucidating apoptosis through mitochondrial damage as the major

mechanism, this research reinforces the scientific validity of using SBP as a

protective agent. When corneal epithelial cells were exposed to UVB irradiation,

cell viability markedly decreased, accompanied by the loss of mitochondrial

membrane potential and morphological abnormalities characteristic of apoptosis

[1, 2]. Moreover, JC-1 staining revealed a pronounced shift from red to green

fluorescence in the UVB group, indicating mitochondrial depolarization [9]. To

exclude cytotoxicity and identify the bioactive fractions, we screened SBP

fractions using an NADH dehydrogenase activity assay. The n-BuOH fraction

demonstrated no mitotoxicity, displaying clear protective effects against

UVB-induced damage (Fig. 1A–L). Given that the MTT assay primarily reflects

mitochondrial activity, SBP may act through mitochondrial regulation. Subsequent

analyses with JC-1 and MitoTracker confirmed this hypothesis [10]. SBP treatment

restored the red/green fluorescence ratio in a dose-dependent manner, with the

n-BuOH fraction exhibiting the most potent protective effect (Fig. 1M–Q).

Furthermore, morphological imaging with MitoTracker revealed that the

mitochondria in UVB-exposed cells were fragmented and punctate, reflecting

oxidative stress and apoptotic signaling initiation. Conversely, SBP-treated

cells maintained elongated tubular mitochondria, indicating mitochondrial

integrity preservation (Fig. 1M–Q). Overall, SBP may prevent mitochondrial

dysfunction, which is a central trigger of apoptosis. To further strengthen our

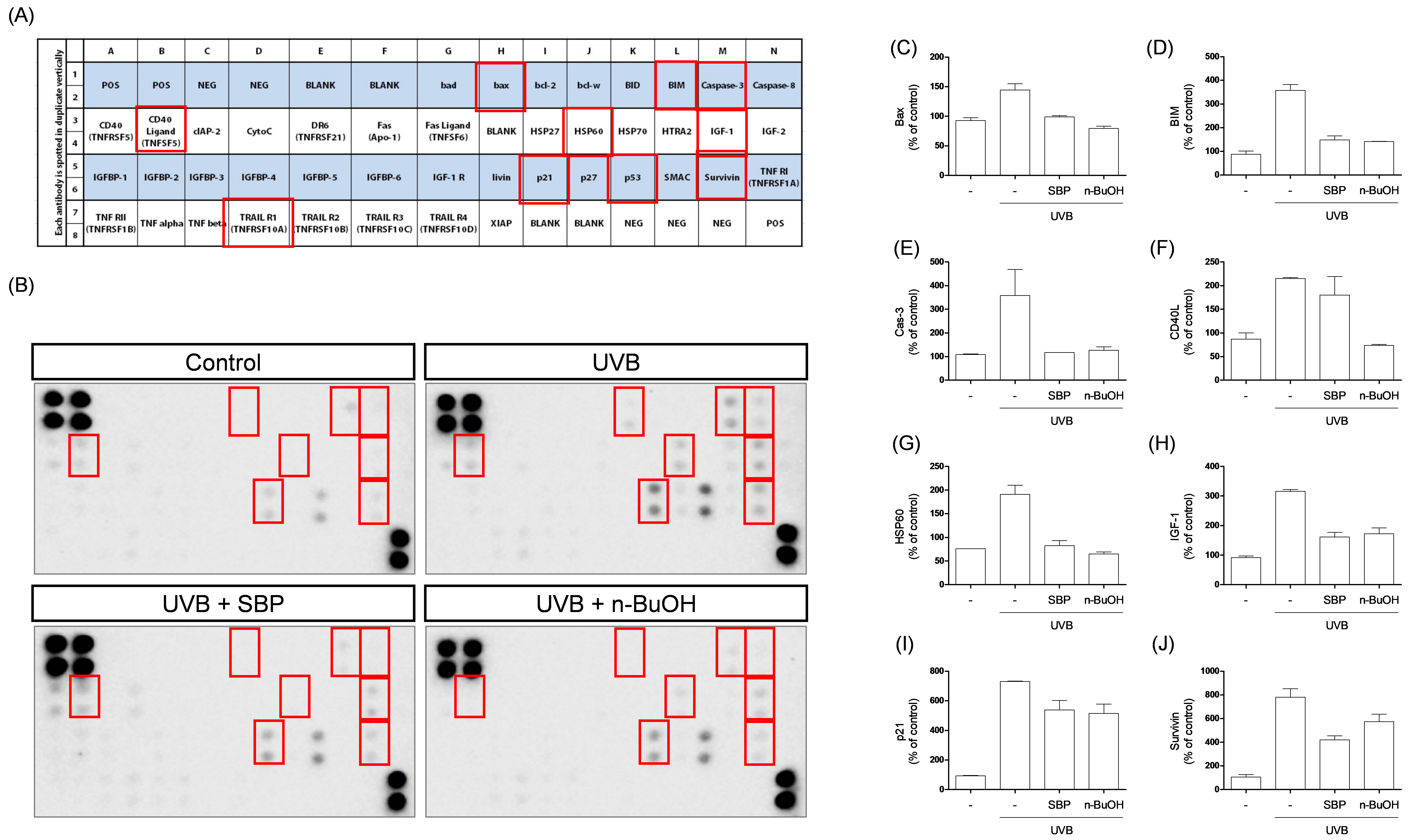

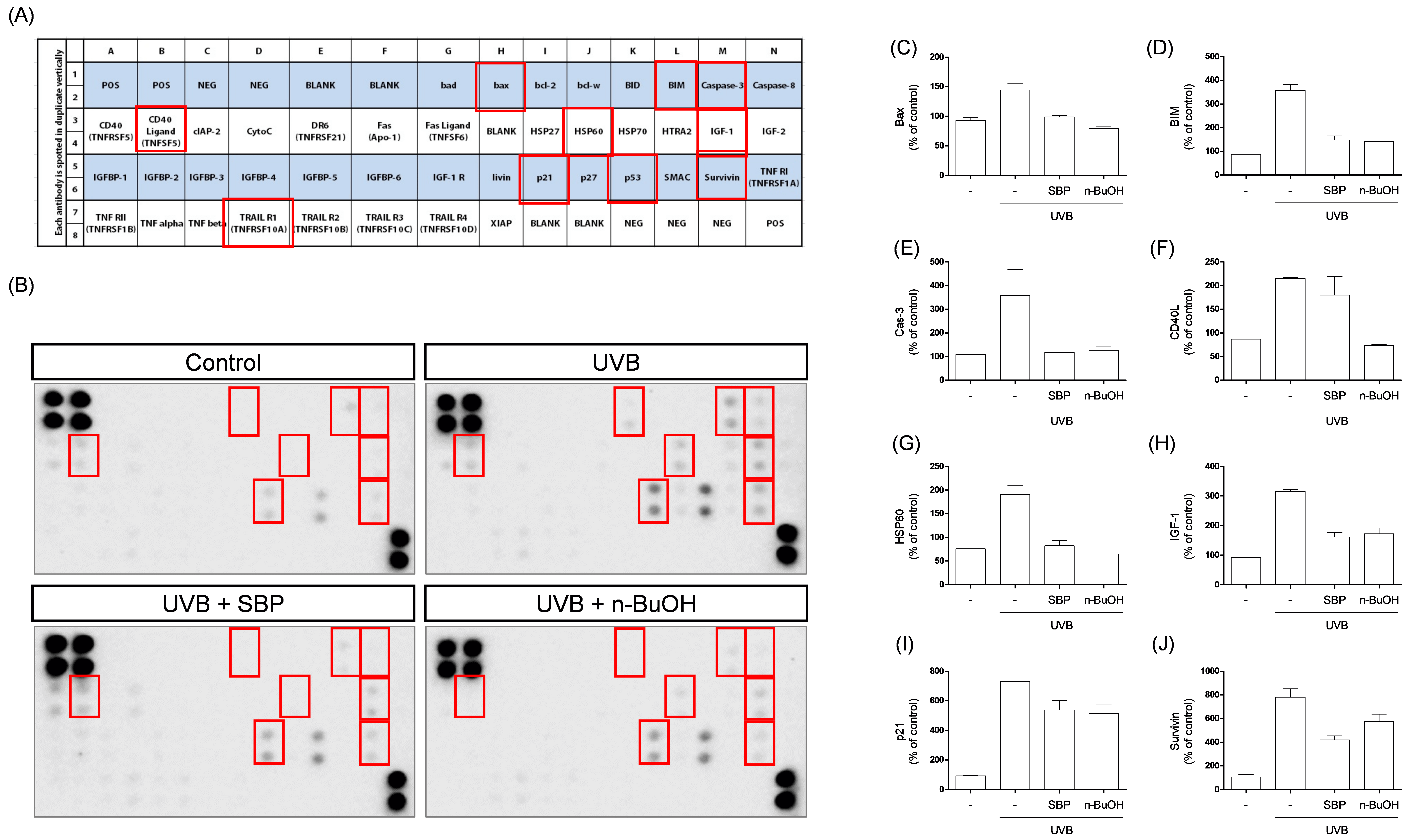

mechanistic insights, an apoptotic protein array was performed. UVB irradiation

increased the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins, including Bcl-2–associated X

protein (Bax), Bcl-2–interacting mediator of cell death (Bim), Cysteine-aspartic

protease-3 (Caspase-3), CD40 ligand (CD40L), Heat shock protein 60 (HSP60),

Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A

(p21), while the anti-apoptotic protein Survivin was dysregulated (Fig. 2). In

particular, the upregulation of Bax and Bim promotes mitochondrial outer membrane

permeabilization, leading to cytochrome c release and subsequent activation of

Caspase-9 and Caspase-3, a hallmark of the intrinsic (mitochondria-mediated)

apoptotic pathway [11]. Additional factors such as CD40L, HSP60, IGF-1, and p21

further reflect stress-induced apoptotic signaling and cross-talk with

mitochondrial processes [12]. Dysregulation of Survivin, an inhibitor of

apoptosis, further amplifies this pro-apoptotic cascade [12]. Importantly, SBP

treatment reversed or attenuated these molecular alterations, restoring the

balance between pro- and anti-apoptotic signaling and thereby counteracting

UVB-induced mitochondrial apoptosis (Fig. 2). Thus, SBP may protect against

UVB-induced corneal apoptosis by maintaining mitochondrial potential and

influencing the expression of key regulators of the intrinsic apoptotic cascade.

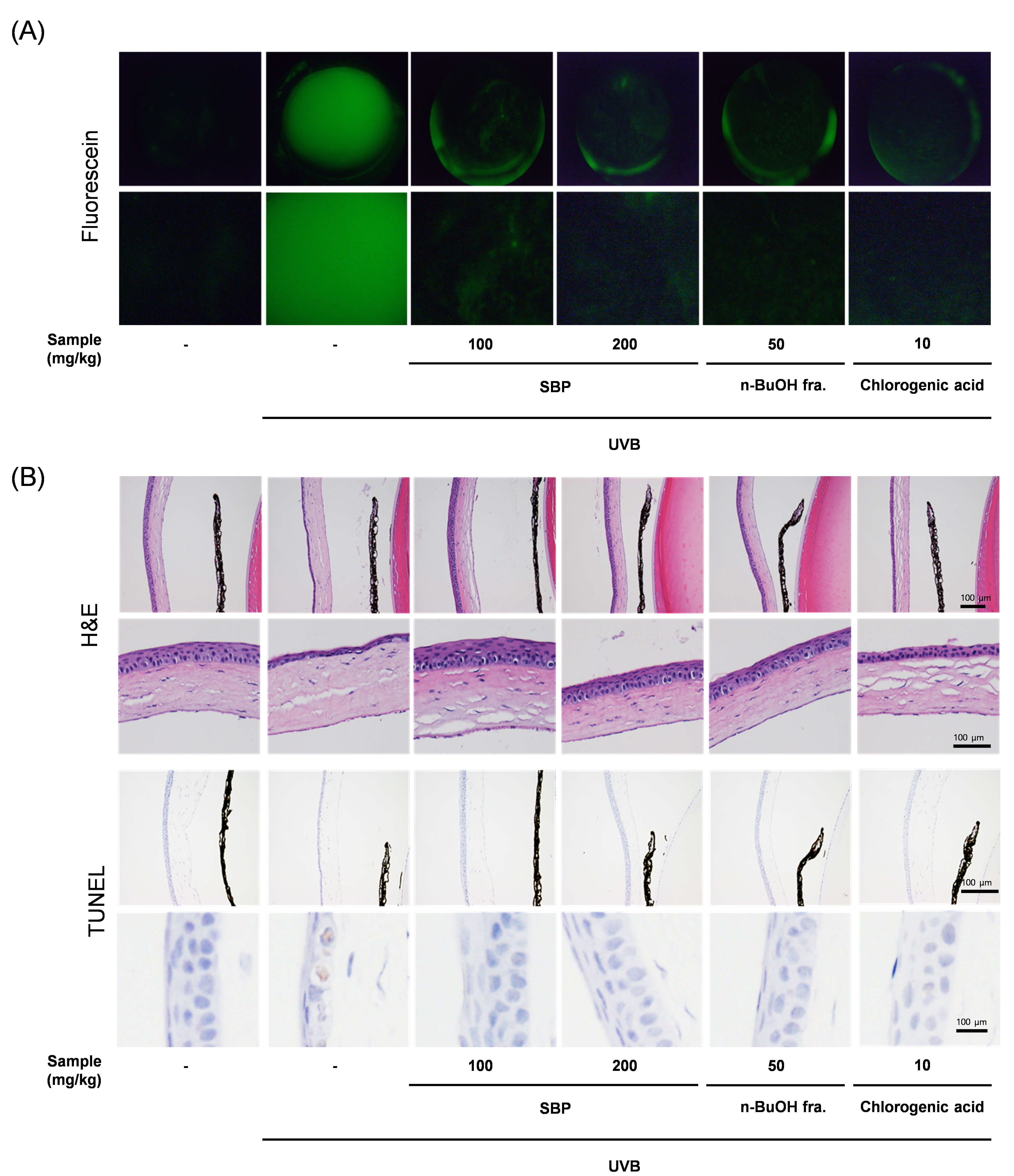

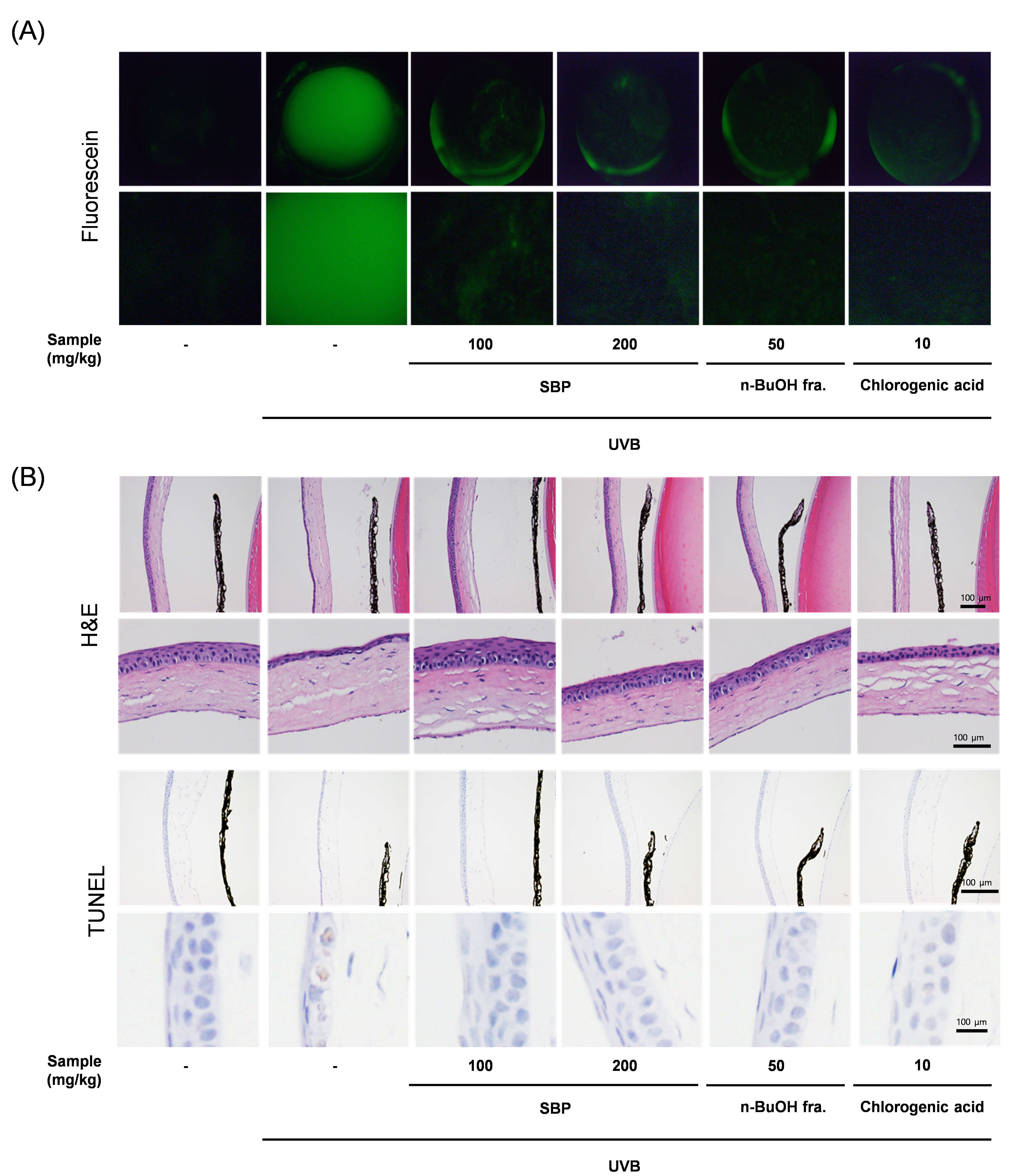

These protective effects were validated in vivo. Fluorescein staining of

the corneal surfaces revealed that UVB exposure induced severe epithelial damage,

characterized by diffuse punctate staining, whereas SBP-treated mice demonstrated

markedly reduced fluorescein uptake, indicating preservation of corneal barrier

integrity (Fig. 3A). This reduction in staining suggests that SBP protected

epithelial tight junctions and maintained barrier function against UVB-induced

disruption (Fig. 3A). Given that fluorescein staining is a clinical indicator of

ocular surface health, these findings further highlight the translational

potential of SBP in preventing UVB-related ocular surface disorders [13].

Histological examination of the corneal tissues from UVB-irradiated mice revealed

epithelium thinning, disorganization of the cell layers, and stromal swelling.

Contrastingly, the SBP-treated corneas retained their epithelial structures and

displayed reduced tissue damage, particularly in the n-BuOH group. Although the

present study did not include a drug-only (without UVB) control group, previous

in vitro and in vivo data have confirmed that SBP and its n-BuOH

fraction are non-toxic to normal cells and tissues [7]. Future studies must

include such drug-only groups to further evaluate the ocular safety and baseline

effects of SBP under physiological conditions. The TUNEL assay provided

additional evidence that numerous TUNEL-positive nuclei were observed in the

UVB-exposed corneal epithelium; nonetheless, these apoptotic signals were

significantly reduced in the SBP-treated groups (Fig. 3B). Quantitative HPLC

analysis from our previous study [7] revealed that it contained high levels of

chlorogenic acid (2.30

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Protective effects of SBP extract and its solvent

fractions against UVB-induced mito-toxicity in corneal epithelial cells. Cell

viability after treatment with (A,G) SBP extract at the indicated

concentrations, with or without UVB irradiation; (B,H) hexane fraction; (C,I) ethyl acetate fraction; (D,J) n-BuOH fraction; (E,K) chloroform

fraction; (F,L) water fraction. (M) Quantitative analysis of mitochondrial

morphology and fluorescence intensity. (N–P) Ratio of red to green fluorescence

indicating mitochondrial membrane potential (

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Effects of SBP extract and its n-BuOH fraction on

UVB-induced apoptosis-related protein expression in corneal epithelial cells.

(A) Layout of the apoptosis antibody array showing the positions of 43

apoptosis-related proteins, with red boxes marking protein spots that exhibited notable expression changes among the groups. (B) Representative protein array blots from each

group: control, UVB, UVB + SBP, and UVB + n-BuOH fraction. Red boxes indicate

protein spots that showed detectable and significant expression changes between

groups. Quantification of (C) Bax expression levels. (D) Bim expression levels.

(E) Caspase-3 expression levels. (F) CD40L expression levels. (G) HSP60

expression levels. (H) IGF-1 expression levels. (I) p21 expression levels. (J)

Survivin expression levels. UVB exposure markedly increased pro-apoptotic protein

expression, which was attenuated by SBP extract and its n-BuOH fraction. SBP and

n-BuOH treatments reduced UVB-induced upregulation of Bax, Bim, Caspase-3, CD40L,

HSP60, IGF-1, and p21, while partially restoring Survivin levels. Data are

presented as mean

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Protective effects of SBP extract and its n-BuOH fraction against UVB-induced corneal damage in mice. (A) Representative fluorescein staining images of corneal surfaces. UVB exposure induced severe epithelial damage and punctate keratopathy, which were markedly reduced by SBP extract and n-BuOH fraction treatment. Due to the curved nature of the corneal surface and the imaging method used (fluorescence photography), exact spatial calibration was not feasible. Therefore, scale bars were not included. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of corneal tissues. UVB irradiation caused epithelial thinning, disorganization, and stromal edema, whereas SBP-treated groups exhibited preserved epithelial structure and reduced tissue injury. Scale bar = 100 µm. TUNEL assay of corneal sections. Numerous TUNEL-positive nuclei were detected in the UVB group, indicating extensive apoptotic cell death. SBP extract and the n-BuOH fraction significantly decreased the number of TUNEL-positive cells, demonstrating their anti-apoptotic effects in vivo. UVB, ultraviolet B; SBP, Peucedanum japonicum Thunb; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling.

In summary, this study demonstrated that the SBP extract exerts significant protective effects against UVB-induced corneal epithelial apoptosis, with the n-BuOH fraction showing the strongest efficacy both in vitro and in vivo. This observed protection appeared to be closely linked to mitochondrial function preservation, suggesting that the active constituents within the n-BuOH fraction may enhance mitochondrial activity and prevent depolarization-induced apoptotic signaling. Based on previous phytochemical analyses and supporting evidence from earlier studies, chlorogenic acid has emerged as a plausible candidate that contributes to this effect. Our previous HPLC profiling confirmed that the n-BuOH fraction contained the highest concentrations of chlorogenic acid and its related derivatives, including neochlorogenic and cryptochlorogenic acids [7]. However, this fraction also contains minor coumarin- and flavonoid-type compounds, which possess antioxidant and anti-apoptotic activities. Therefore, synergistic interactions among multiple constituents may collectively contribute to the overall protective effects of SBP against UVB-induced corneal injury. Nevertheless, further investigations are warranted to confirm whether chlorogenic acid is the major bioactive compound or whether synergistic interactions among multiple n-BuOH fraction components are responsible. Future studies should focus on isolating the active constituents, clarifying mitochondria-related molecular pathways in greater detail, and assessing the long-term safety and clinical applicability in preclinical models. Furthermore, evaluating the ocular bioavailability and tissue distribution of SBP-derived compounds particularly chlorogenic acid and its derivatives will be essential for future translational development. Pharmacokinetic and corneal penetration studies are planned to determine the absorption, distribution, and retention of these compounds within ocular tissues. One limitation of this study is that only male mice were used in the in vivo experiments to minimize hormonal variability. However, sex-related physiological differences may affect oxidative stress responses and drug efficacy. Therefore, future studies should include both male and female mice of matching age and weight to comprehensively evaluate potential sex-dependent variations and enhance the translational relevance of our findings.

SBP extract, particularly its n-BuOH fraction, effectively protected corneal epithelial cells against UVB-induced apoptosis by preserving mitochondrial function and modulating apoptosis-related proteins. Both in vitro and in vivo evidence support its potential as a safe natural candidate for preventing or treating UV-related ocular surface disorders. Therefore, SBP is a promising therapeutic target for ophthalmic development. Further studies are warranted to isolate the active compounds and evaluate their long-term efficacy.

NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; n-BuOH, n-butanol; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; SBP, Peucedanum japonicum Thunb.; SD, standard deviation; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling; UVB, ultraviolet B;

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conceptualization, HL, YY, GP, SK; methodology, GP, HL; formal analysis, GP, HL; investigation, GP, SK; data curation, GP, HL; writing—original draft preparation, HL, GP; writing—review and editing, HL, YY, GP, SK; visualization, HL, GP, SK; supervision, GP, SK. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The Institutional Animal Care Committee of the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KIOM) approved the experimental protocols KIOM: #25-010, which were performed according to the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee at KIOM.

We sincerely thank the Open Innovation Business Incubation Center at Inha University Hospital for their technical and research support.

This work was supported by the Jeollanam-do R&D program operated by Jeonnam Technopark (KIOM management No. ERN2411030) for the project titled, “Functional eye health food made from Peucedanum japonicum Thunb. extract to improve visual acuity deterioration caused by phototoxicity.” and the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KSN2511030) through the Development of Innovative Technologies for the Future Value of Herbal Medicine Resources project.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Young-Sik Yoo is an employee of Mediverse Co., Ltd. Sunoh Kim is an employee of the Central R&D Center of B&Tech Co., Ltd. The authors declare that these affiliations did not influence the study design, data interpretation, or manuscript preparation.

During preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT [5.0 version, OpenAI] for language editing and grammar checking. After using this tool, the authors carefully reviewed and revised the text and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/FBL46498.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.