1 Institute of Biostructures and Bioimaging, National Research Council, 80131 Naples, Italy

2 Department of Environmental, Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, 81100 Caserta, Italy

3 Department of Pathogen Biology and Immunology, University of Wrocław, 51-148 Wrocław, Poland

Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae is one of the most critical Gram-negative bacteria according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Due to the ability of this bacterium to evade antibiotics, phage therapy is becoming a promising tool. However, the use of isolated proteins rather than entire phages could reduce several risks associated with phage replication. Thus, understanding the protein composition and structural organization of bacteriophages is crucial for unlocking their biology and holds great potential for medicine and biotechnology.

In this study, artificial intelligence with AlphaFold 3.0 (AF3) and bioinformatic analysis were used to model the hitherto unknown structure of the Klebsiella phage KP32 (KP32), a complex and selective phage that targets K. pneumoniae strains with the K3 and K21/KL163 capsular serotypes.

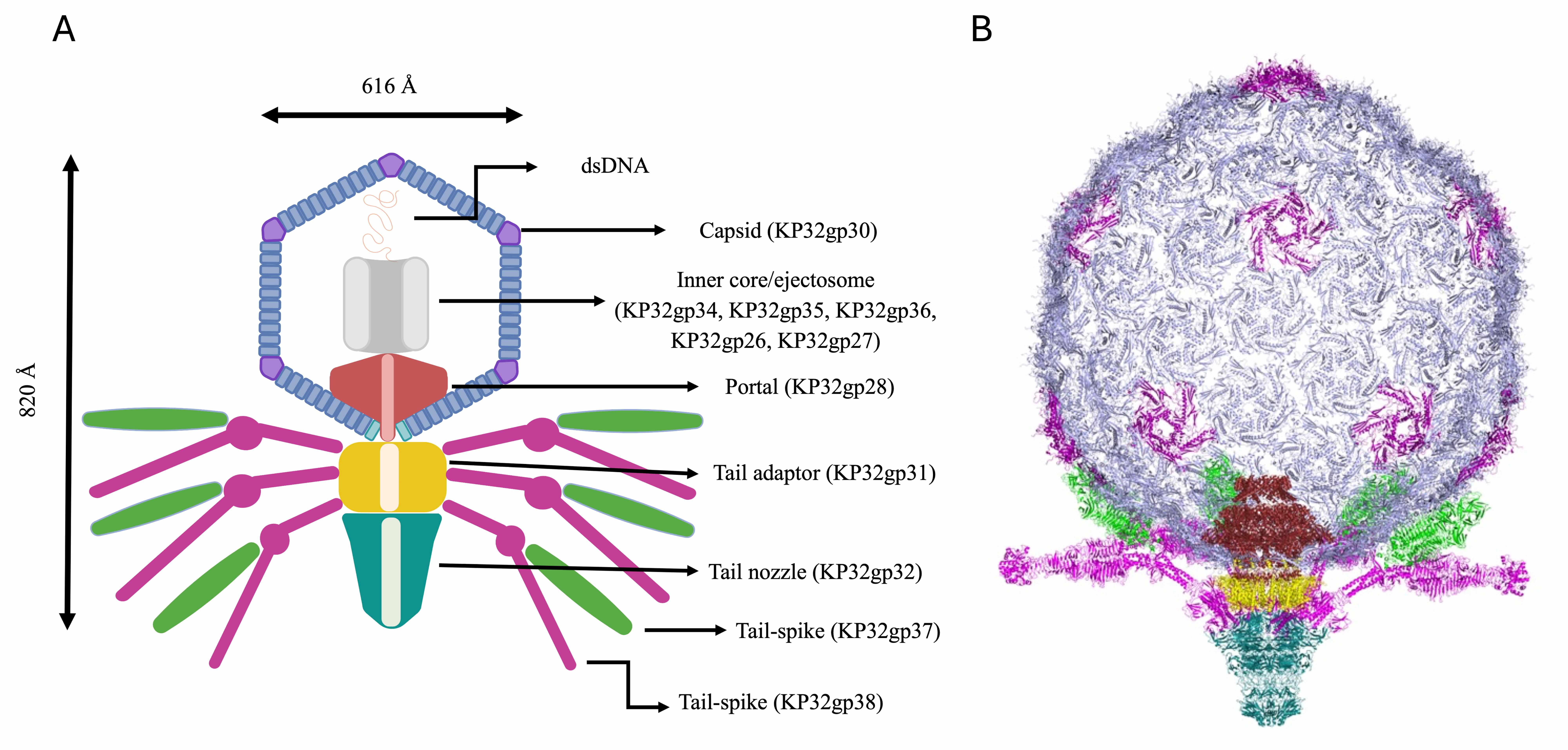

By combining AF3 with sequence and structure analysis, we reconstructed the entire phage KP32. This complex phage is composed of over 500 protein chains, of which 415 compose its capsid and 104 its core-portal-tail complex, a platform that allows the phage to adhere to K. pneumoniae, hydrolyze its capsular sugars and finally inject its genetic code into the bacterium.

Phage therapy is a potentially promising tool for controlling antimicrobial resistance (AMR). However, one limitation arises from the limited knowledge of their nature and mechanisms of action, as only a few phages have been structurally characterized. The reconstruction of entire phages is currently a viable strategy for elucidating their mechanistic properties, knowledge that will enhance their potential applications as therapeutic alternatives.

Keywords

- Klebsiella pneumoniae

- artificial intelligence

- protein structure

- bacteriophage

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in gram-negative bacteria is one of the most urgent threats to global health [1, 2]. Among the most critical gram-negative bacteria according to the World Health Organization (WHO) is Klebsiella pneumoniae, which has evolved sophisticated mechanisms to evade antibiotics, making infections harder to treat and control [3, 4]. Bacteriophages, or phages, are viruses that infect bacteria, and their ability to hijack bacterial machineries hinges on a diverse arsenal of specialized proteins. Phage therapy is emerging as a powerful tool to combat drug-resistant gram-negative bacteria [5, 6, 7], although it involves several scientific and clinical concerns that researchers and regulators are actively working on to address [8].

Phage proteins offer several advantages over using the whole bacteriophages, especially in therapeutic and biotechnological applications. They allow for more precise, safer, and customisable approaches to targeting bacteria. Proteins such as endolysins and depolymerases can directly degrade bacterial cell walls or capsules without requiring full phage replication [9, 10, 11]. While the whole phage may carry and transfer unwanted genes (e.g., antibiotic resistance or virulence factors), the isolated proteins eliminate this risk. Additionally, proteins are easier to standardize, purify, and regulate than the entire viral entity.

Most commonly, phages exhibit a head-tail morphology, resembling a microscopic lunar lander designed to land on bacterial surfaces. At the core of a phage is the capsid, a protein shell that houses its genetic material, either DNA or RNA. This head is often icosahedral in shape, providing both strength and efficiency in packaging the viral genome. Extending from the capsid is the tail, a complex apparatus used to recognize, attach to, and penetrate bacterial cells. Understanding phage structures is key to unlocking their potential in medicine, biotechnology, and ecology.

The T7 bacteriophage, which infects Escherichia coli, is structurally well characterized and has served as a model system for understanding phage biology. Indeed, its relatively simple genome (~40 kb) and well-defined infection cycle make it ideal for genetic and structural studies [12]. The tail machinery and DNA ejection process have been visualized in detail, revealing conformational changes upon receptor binding [13]. Recent cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures of bacteriophage T7 have provided deep insights into its architecture and infection mechanisms (Protein Databank (PDB) codes 6YSZ, 3J7V, 2XVR, 9JYZ, 9JZ0, 9JYY, 7EY6, 7EY7, 7EY8, 7EY9, 7EYB, 7BOU, 7BOX, 7BOY, 7BOZ, 7BP0) [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18]. In particular, it has been reported that the capsid of the bacteriophage T7, which protects its double-stranded (ds) DNA, is formed by the gene product 10 (T7gp10) and presents an icosahedral assembly. A phage portal complex is located in a single pentameric vertex of the capsid and acts as an initiator of capsid assembly. Moreover, a cylinder-shaped core structure formed by the ejection proteins (core proteins) T7gp14, T7gp15, and T7gp16 is present on top of the portal within the capsid shell. It has been suggested that the core proteins form a trans-envelope channel for genome delivery into infected cells [13]. Specifically, T7gp16 exerts lytic transglycosylase (LTase) activity, which is required for penetration into the bacterial peptidoglycan layer [13]. Finally, a tail consisting of an adaptor formed by the protein T7gp11 and a nozzle composed of the protein T7gp12 protrude from the capsid and load six subunits of the trimeric tail fiber T7gp17 [13]. These tail fibers allow bacterial receptor recognition and adsorption [13].

The bacteriophage KP32 has several characteristics that make it a strong

candidate model phage, especially for studying K. pneumoniae infections

and phage-borne depolymerases. Indeed, its genetic and enzymatic components are

well characterized, making it suitable for molecular studies. The phage KP32 is a

dsDNA bacteriophage belonging to the Autotranscriptaviridae family,

specifically the Przondovirus genus. Like other members of this group,

it uses DNA as its genetic material to infect K. pneumoniae. The phage

KP32 targets K. pneumoniae strains with the capsular serotypes K3 and

K21/KL163 because of its two capsule depolymerases, KP32gp37 and KP32gp38 [19].

The depolymerases form trimeric

The atomic-level structure of bacteriophages that target K. pneumoniae is a growing area of research, especially with the rise of multidrug-resistant strains. Full atomic-resolution structures (such as those from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM) are still unavailable and limited to phage tail depolymerases (PDB codes 6TKU, 9QRM, 7LZJ, 8BKE, 7W1C, 7W1D, 7W1E) [9, 10, 21, 22, 23] and to the capsid and the tail complex of the Klebsiella phage Kp9 (7Y23, 7Y1C), which are still unpublished. AlphaFold3 (AF3) is a major leap forward in biomolecular structure prediction, building on the success of AlphaFold2 but expanding its scope [24]. By combining AF3 with bioinformatic analysis, we provide a full reconstruction of the phage KP32 against K. pneumoniae. This giant machine has a maximum size of more than 800 Å and is composed of over 500 protein chains organized in different compartments. 415 chains compose the phage capsid, adopting an icosahedral symmetry. At one unique vertex of the icosahedral capsid, a portal-tail complex acts as a gateway for DNA packaging and release [13]. Finally, 36 chains compose the phage tails and are organized in multiple copies of a complex formed by two depolymerases (KP32gp37 and KP32gp38) with different capsular specificities [19]. Knowing a bacteriophage structure empowers us to harness, redesign, and implement these microscopic warriors in medicine, research, and beyond.

Sequence alignment to identify phage KP32 protein constituents was performed using BlastP (National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), Bethesda, MD, USA) [25]. We found that phage KP32 proteins share high sequence similarity with proteins of the E. coli T7 phage, whose composition and structure have been described [12]. The structure alignment was performed using DALI (Distance-matrix ALIgnment, http://ekhidna2.biocenter.helsinki.fi/dali) [26].

The three-dimensional structure models of seven proteins composing phage KP32

were obtained using AF3 modeling server (https://www.alphafoldserver.com) and the

most up-to-date database available (as of February 3, 2025). The server produced

five ranked models for each protein [27]. One phage protein, the tail spike

depolymerase KP32gp38, is available from the PDB (PDB codes 6TKU, 9QRM) [10, 23].

The confidence of the models was evaluated on the basis of the predicted local

distance difference test (pLDDT), a per-residue measure of model confidence.

pLDDT is scaled between 0 and 100, with higher scores reflecting greater

confidence in the structural model (very low: pLDDT

Given the low value of ipTM (0.5) for the AF3 prediction of the heptameric assembly of KP32gp30 and the failed attempts to model both the entire inner core of KP32 and the single proteins that constitute it (KP32gp34, KP32gp35, KP32gp36) using AF3, we additionally model them via homology modeling and the software SWISS-MODEL (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB) and Biozentrum, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland) [32]. A template search with BLAST [33] and HHblits [34] was performed against the SWISS-MODEL template library (SMTL, last update: 2025-07-02, last included PDB release: 2025-06-27). The target sequence was searched with BLAST against the primary amino acid sequence contained in the SMTL. An initial HHblits profile was built using the procedure outlined in Steinegger et al. [34], followed by iterations of HHblits against Uniclust30 [35]. The obtained profile was searched against all the profiles of the SMTL. For each identified template, the quality was predicted from features of the target-template alignment. The templates with the highest quality were selected for model building. Models were built on the basis of target–template alignment using ProMod3 (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB) and Biozentrum, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland) and geometry normalization [36]. The global and per-residue model quality was assessed using the Qualitative Model Energy Analysis (QMEAN) scoring function combined with a distance constraint (DisCo) score, which assesses the agreement of pairwise distances in the model and an ensemble of constraints derived from experimentally determined homologous protein structures [37]. The quaternary structure annotation of the template is used to model the target sequence in its oligomeric form. The method proposed by Bertoni et al. [38] is based on a supervised machine learning algorithm, support vector machines (SVMs), which combines interface conservation, structural clustering, and other template features to provide a quaternary structure quality estimate (QSQE). The QSQE score is a number between 0 and 1, reflecting the expected accuracy of the interchain contacts for a model built on the basis of a given alignment and template. This complements the Global Model Quality Estimation (GMQE) score, which estimates the accuracy of the tertiary structure of the resulting model.

By analyzing the phage KP32 genome, we identified a major capsid protein, constituting the phage capsid shell, the major head protein KP32gp30 (YP_003347548.1). A search in the PDB using the BlastP tool revealed that this protein has high sequence identity (79.5%) with the major capsid protein from phage T7, whose structure is reported in the PDB (PDB code 2XVR [16]). Phage T7 is a well-studied lytic virus that infects E. coli, making it a powerful model in molecular biology and a potential tool in biotechnology and phage therapy. Starting from this observation, we searched for all proteins composing phage KP32 on the basis of sequence identity with their homologs in phage T7. Overall, we identified ten protein components of phage KP32 that are homologous to T7 phage proteins, with sequence identities higher than 45% (Table 1, Ref. [10, 13, 16, 17, 23]). We have previously shown that the phage KP32 has the ability to carry on its phage portal two types of depolymerases, KP32gp37 and KP32gp38, with different serotype specificities [19]. The second KP32 protein with depolymerase activity, KP32gp38, has no homologs in phage T7.

| Protein | Accession code | Homolog sequence in T7 phage, PDB code | Sequence identity (%) | RMSD (Å) | Structure |

| Major head protein (KP32gp30) | YP_003347548.1 | Major capsidprotein (T7gp10A), 2XVR [16] | 79.5 | 3.9 | AF3 |

| Head-tail adaptor (KP32gp28) | YP_003347546.1 | Portal protein (T7gp8), 7EY6 [13] | 78.8 | 3.0 | AF3 |

| Tail protein (Kp32gp37) | YP_003347555.1 | Tail fiber protein (T7gp17), 9JYZ [17] | 45.1 | 0.9 | AF3 |

| Tail protein (Kp32gp31) | YP_003347549.1 | Tail tubular protein (T7gp11), 9JYZ [17] | 62.2 | 0.8 | AF3 |

| Tail protein (Kp32gp32) | YP_003347550.1 | Tail tubular protein (T7gp12), 9JYZ [17] | 61.5 | 0.6 | AF3 |

| Tail spike protein (Kp32gp38) | YP_003347556.1 | None | * | * | X-ray (PDB codes 6TKU, 9QRM) [10, 23] |

| Internal virion protein B (KP32gp34) | YP_003347552.1 | Internal virion protein (T7gp14), 9JYY [17] | 59.0 | ** | SWISS-MODEL |

| Internal virion protein C (KP32gp35) | YP_003347553.1 | Internal virion protein (T7gp15), 9JYY [17] | 65.2 | ** | SWISS-MODEL |

| Internal virion protein D (KP32gp36) | YP_003347554.1 | Internal virion protein (T7gp16), 9JYY [17] | 66.7 | ** | SWISS-MODEL |

| Host range and adsorption protein (KP32gp27) | YP_003347545.1 | Host range and adsorption protein (T7gp7.3), 9JYZ [17] | 51.3 | 3.0 | AF3 |

| DUF5476 domain-containing protein (KP32gp26) | YP_003347544.1 | DUF5476 family protein (T7gp6.7), 9YJZ [17] | 47.7 | 6.3 | AF3 |

* No homolog in the T7 phage; ** homologs in the T7 phage were used as templates. PDB, Protein Databank; AF3, AlphaFold 3.0; KP32, Klebsiella Phage; RMSD, Root-Mean-Square Deviation.

Once we had identified all phage KP32 components, we modeled their 3D structures using AF3 and with the oligomeric state observed for the phage T7. As its name suggests, this phage presents a capsid with T7 symmetry, with icosahedral symmetry in its capsid structure [14, 15].

Most protein structures were modeled with high confidence (pLDDT values

| Protein | Functional assembly/role | Reliability scores* | Assembly | Number of copies in KP32 phage | |

| pLDDT/ipTM | QMEANDisCo | ||||

| KP32gp30 | Capsid | 83.6/0.5 | 0.63 | 60 heptamers/60 hexamers and 11 pentamers | 415 |

| KP32gp26 | Inner core | 65.8 | - | Inner core heterocomplex | 12 |

| KP32gp27 | Inner core | 68.0 | - | Inner core heterocomplex | 6 |

| KP32gp34 | Inner core/ejectosome | - | 0.72 | Inner core heterocomplex | 8 |

| KP32gp35 | Inner core/ejectosome | - | Inner core heterocomplex | 8 | |

| KP32gp36 | Inner core/ejectosome | - | Inner core heterocomplex | 4 | |

| KP32gp28 | Portal | 77.2/0.7 | - | 1 dodecamer | 12 |

| KP32gp31 | Tail adaptor | 78.8/0.7 | - | 1 dodecamer | 12 |

| KP32gp32 | Tail nozzle | 83.6/0.8 | - | 1 hexamer | 6 |

| KP32gp37 | Tail-spike | 80.5/0.6 | - | 6 trimers | 18 |

| KP32gp38 | Tail-spike | ** | ** | 6 trimers | 18 |

* Reliability scores refer to the adopted prediction software; ** X-ray structure available (PDB code 6TKU). pLDDT, predicted local distance difference test; QMEANDisCo, qualitative model energy analysis scoring function combined with a distance constraint.

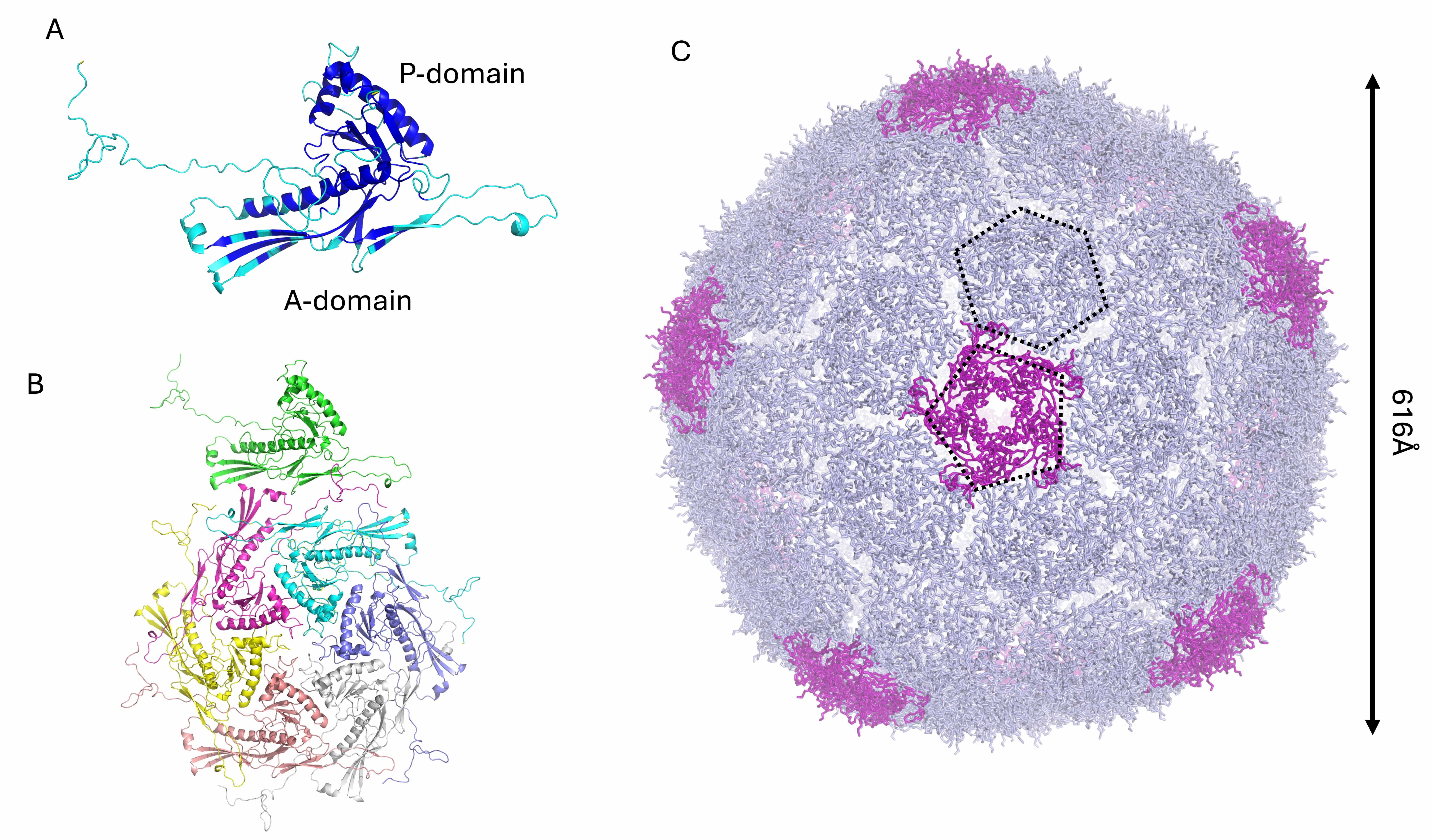

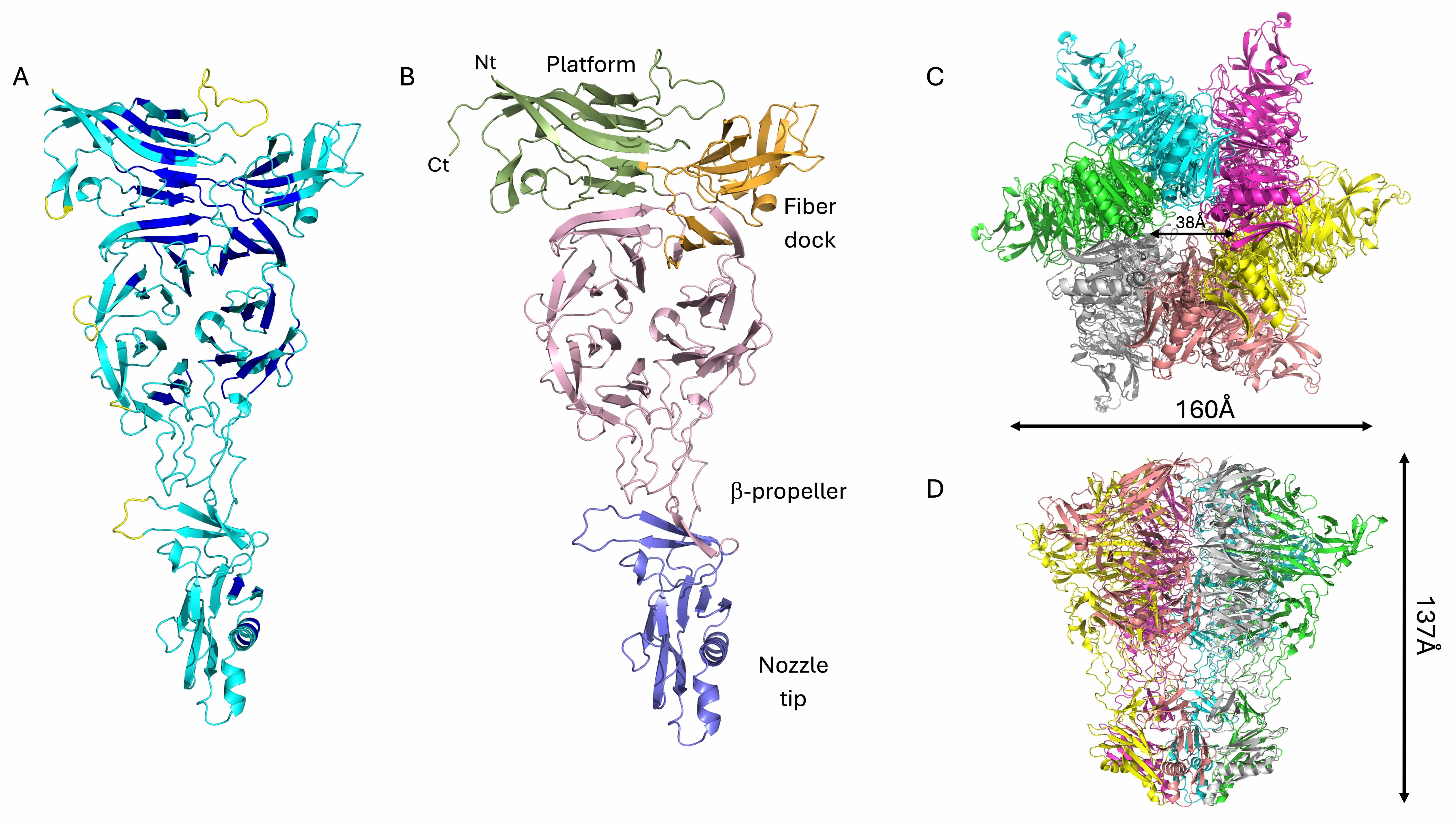

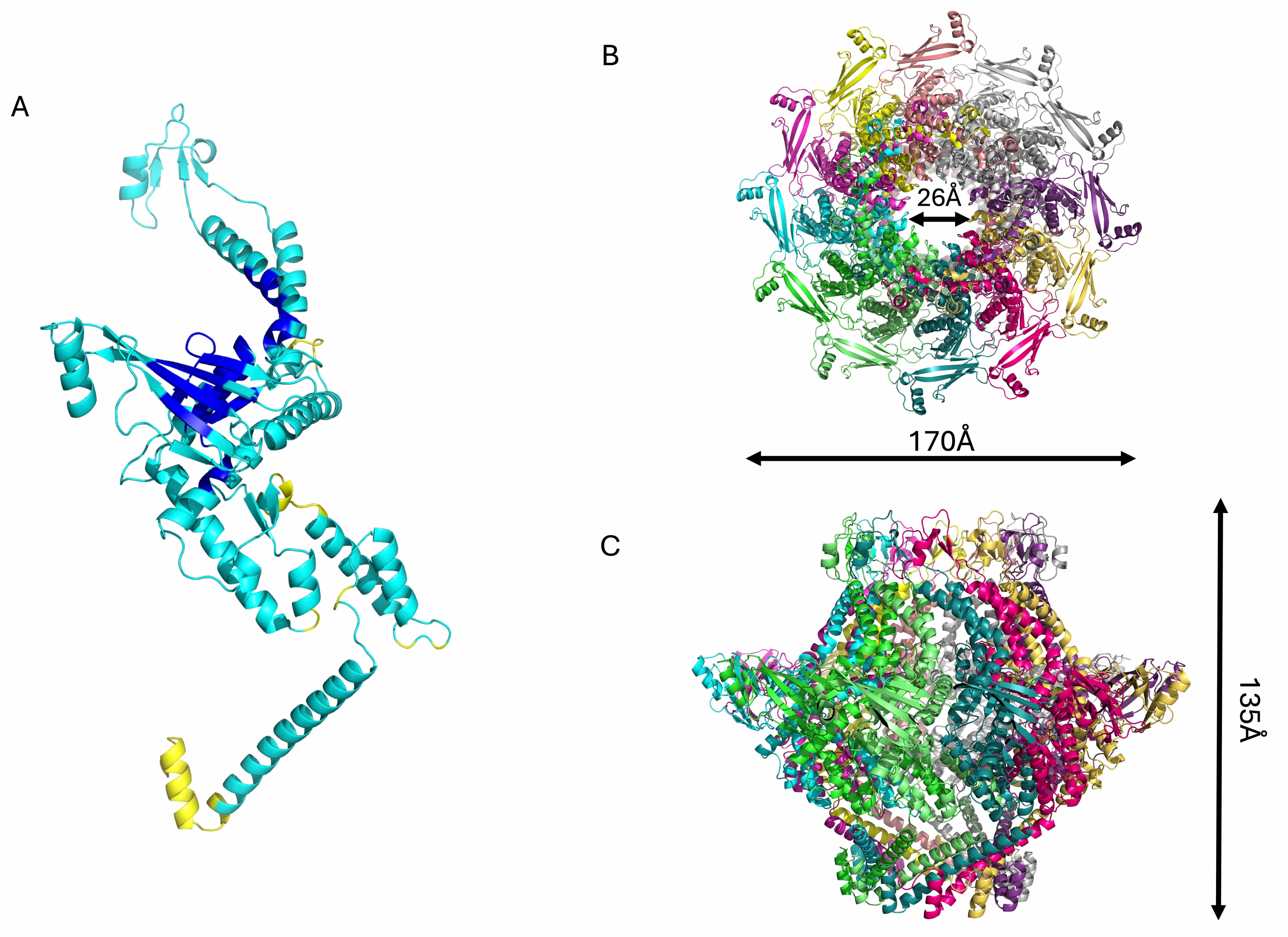

The KP32gp30 mature capsid protein was modeled as a heptamer, analogous to the

T7 phage. The KP32gp30 mature capsid promoter has an alpha‒beta fold (Fig. 1A).

Like T7gp10, KP32gp30 is composed of an A-domain, which is predominantly composed

of

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Structural model of the phage KP32 capsid. Cartoon

representations of (A) the KP32gp30 capsid monomer colored according to the AF3

confidence intervals: dark blue, very high (pLDDT

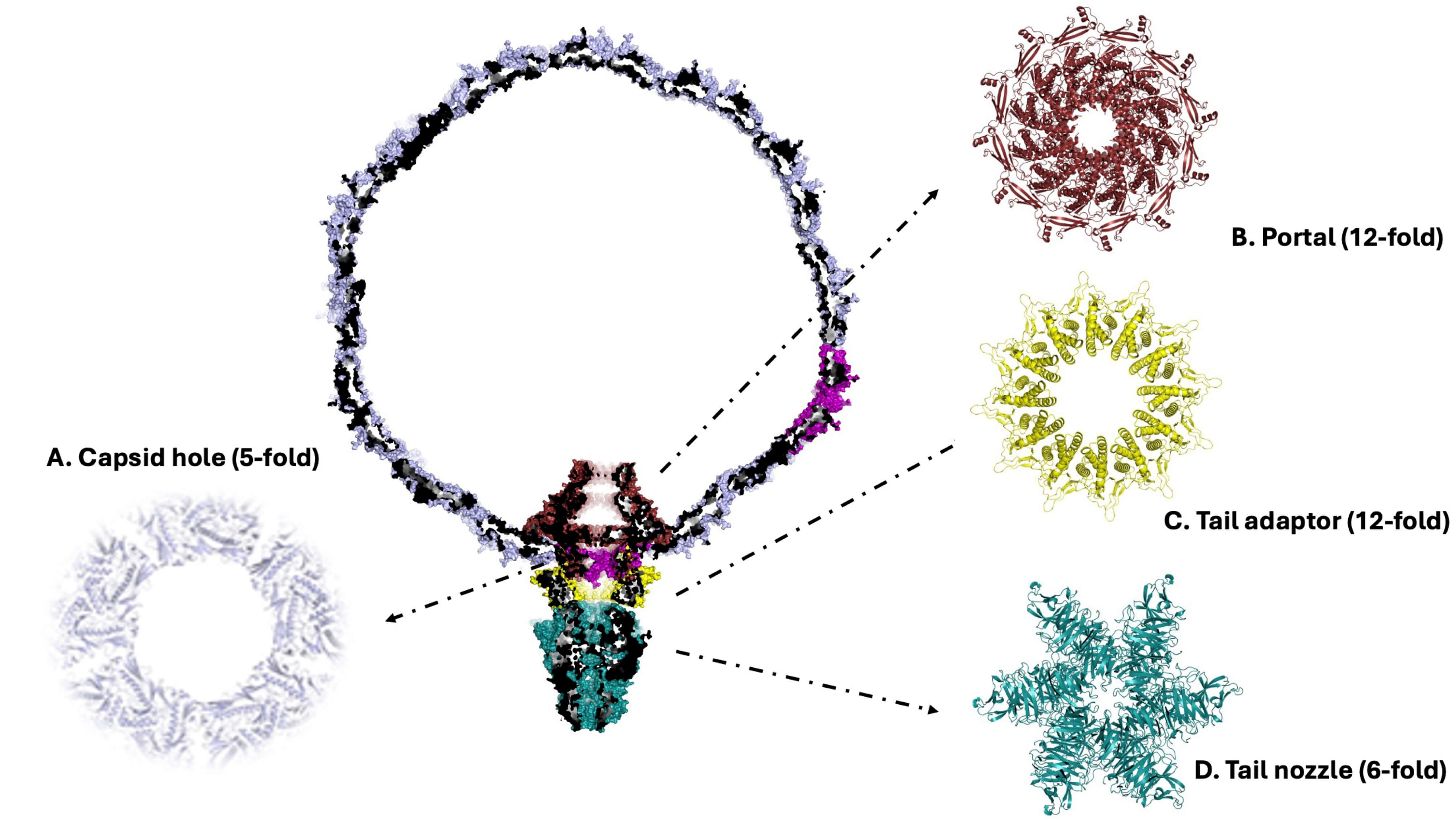

After full reconstruction, the phage KP32 capsid is composed of 60 KP32gp30 heptameric assemblies, with a total of 420 chains (Fig. 1C). This reconstruction of a phage T7 icosahedral capsid exposes 60 hexameric and 12 pentameric faces (Fig. 1C). Pentamers constitute the vertices of the icosahedron, which provide curvature and close the shell. The resulting capsid shell has a diameter of 616 Å (Fig. 1B). To build the mature phage, one pentameric vertex was removed to make room for the portal for genetic code entry and exit [41, 42, 43].

In addition to the capsid shell of phage KP32, an additional 104 protein chains

constitute the phage portal-tail complex, with a total of over 500 protein chains

(Table 2). As previously mentioned, the missing pentamer at one vertex of the

phage KP32 capsid is replaced by the portal complex formed by the protein

KP32gp28, which shares 78.8% sequence identity with gp8 of the phage T7, whose

structure has been solved using cryo-EM (PDB code 7EY6) (Table 2). A reliable

structural model of the KP32gp28 portal dodecamer was obtained using AF3

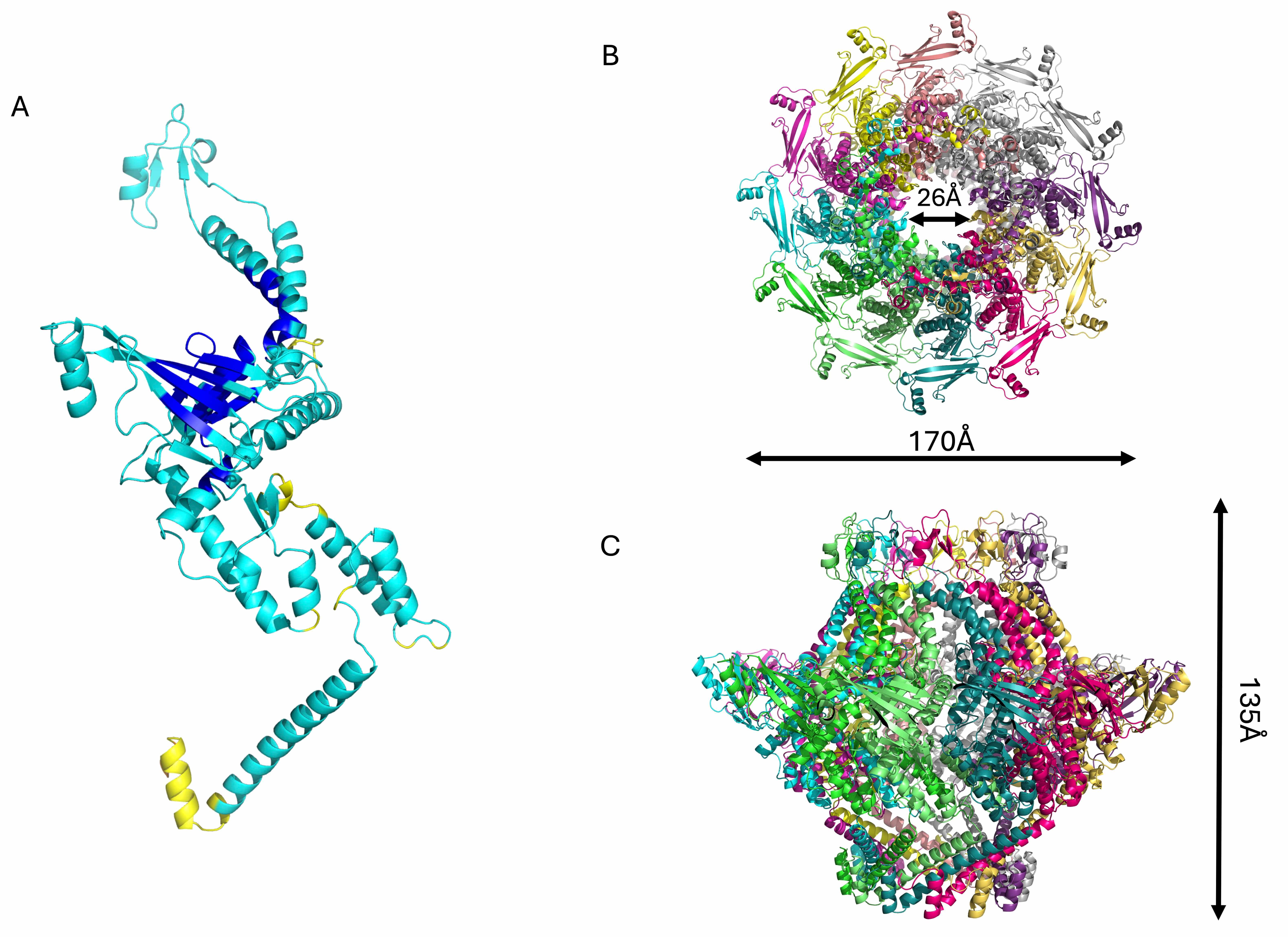

(pLDDT/ipTM: 77.2/0.7, Table 2, Fig. 2). The KP32gp28 monomer folds into an

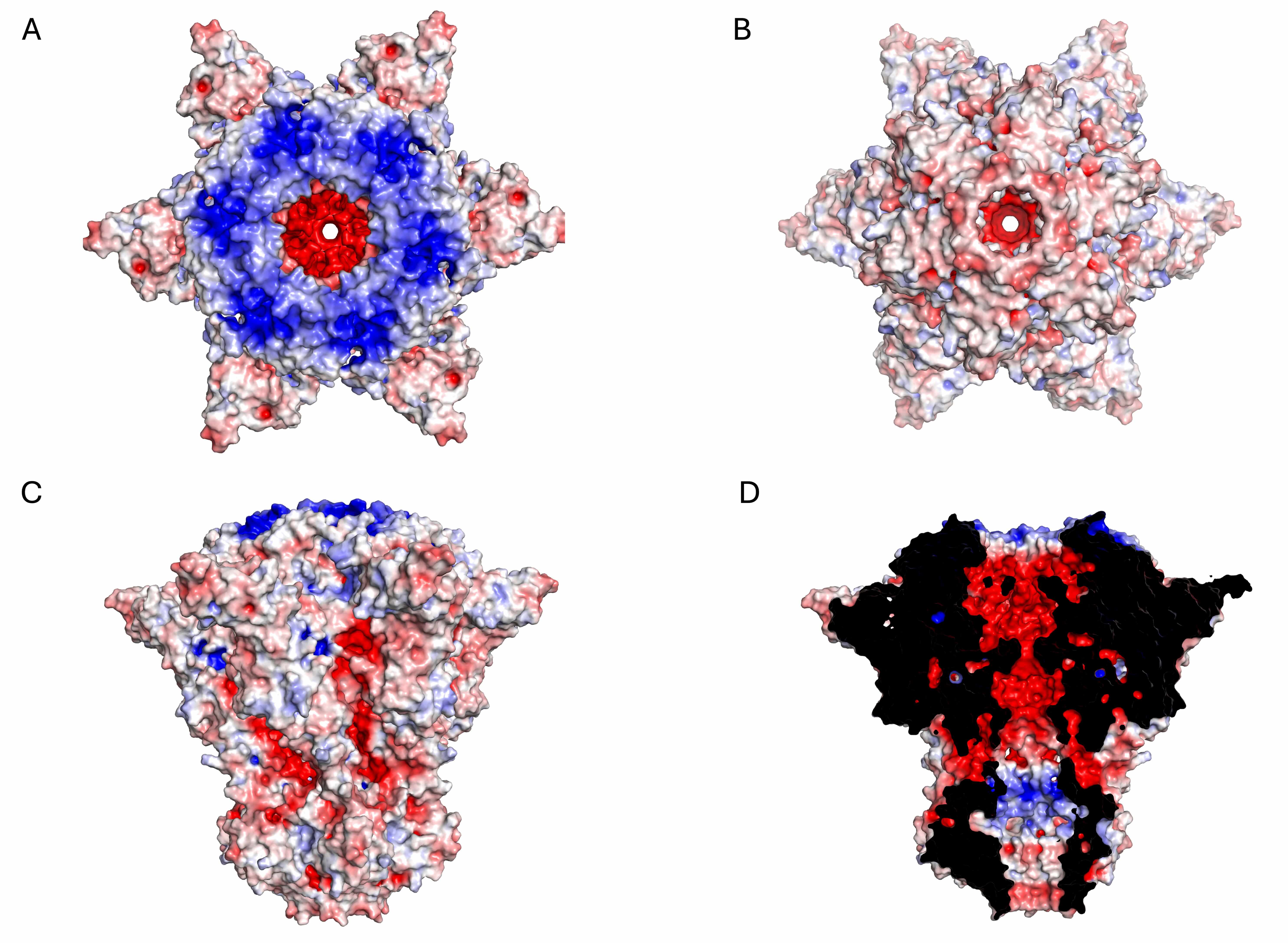

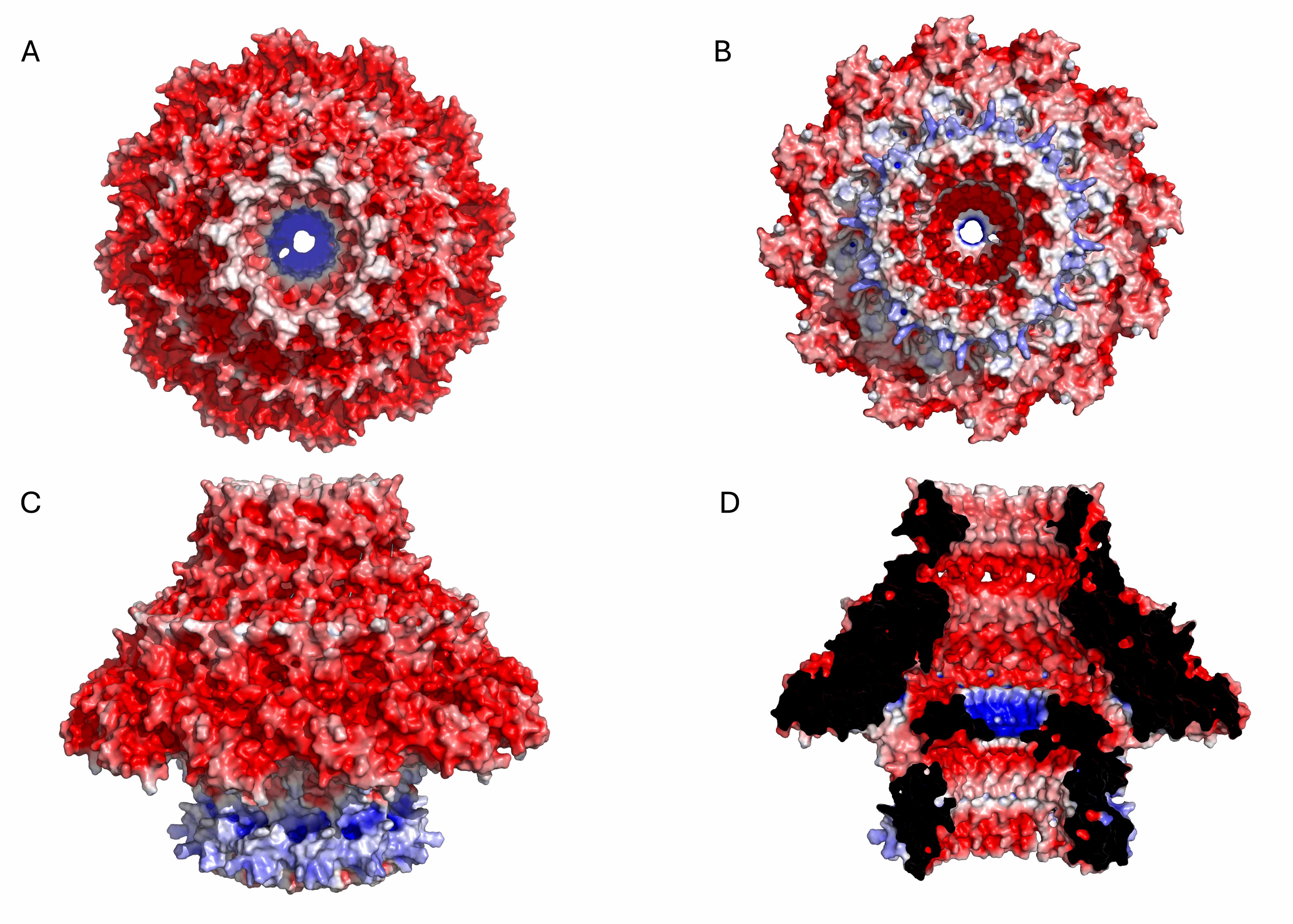

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Structural model of the phage KP32 adaptor. Cartoon

representations of (A) the KP32gp28 portal monomer, colored according to the AF3

confidence intervals (dark blue, high (pLDDT

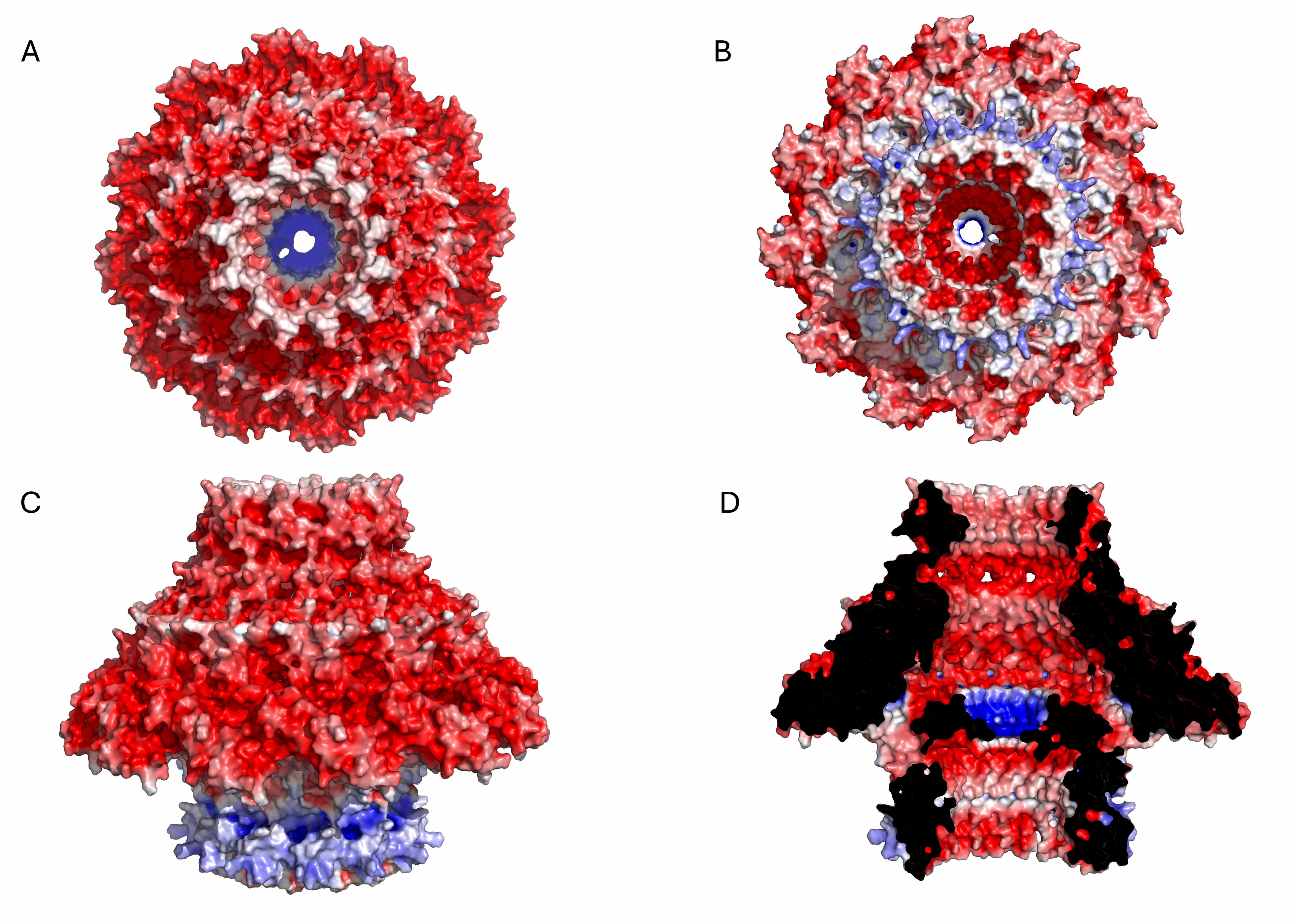

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Electrostatic potential surface of the KP32gp28 portal dodecameric assembly. (A) Top view, (B) bottom view, (C) side view, and (D) inner section. The red- and blue-colored surfaces represent negative and positive electrostatic potentials, respectively.

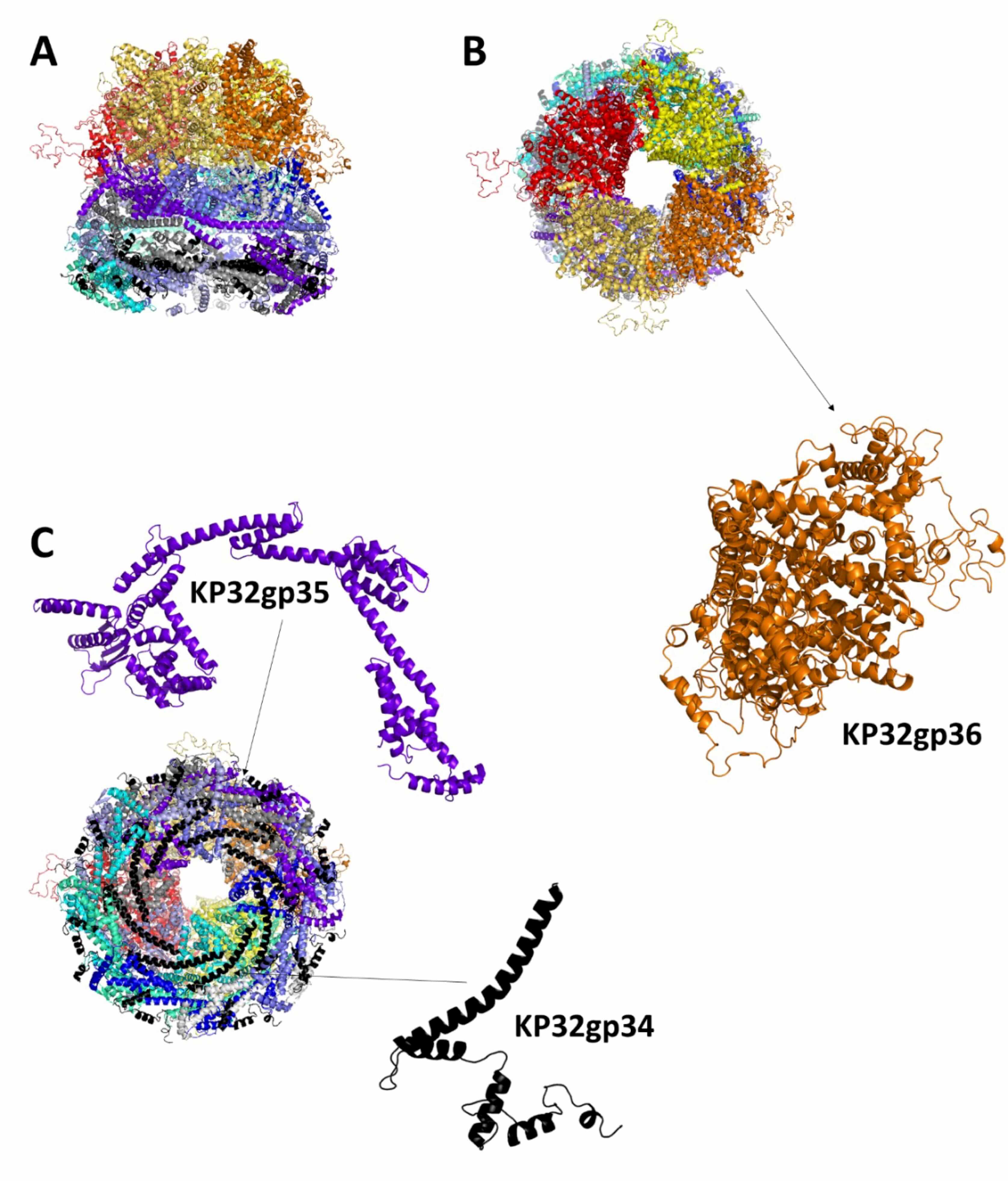

Compared with phage T7, phage KP32 also possesses a similar inner core

structure, which is expected to form a large cylindrical assembly located inside

the capsid, right beneath the portal protein at one of the icosahedral vertices

of the phage head. Indeed, the T7gp14, T7gp15, and T7gp16 ejection proteins are

homologous to KP32gp34, KP32gp35 and KP32gp36, with sequence identities of 59%,

65.2% and 66.7%, respectively (Table 1). Additionally, the inner core proteins

T7gp6.7 and T7gp7.3 have homologous sequences in KP32, sharing 47.7% and 51.3%

with KP32gp26 and KP32gp27, respectively. Analogous to the T7 phage structure,

the inner core of KP32 is expected to be composed of eight copies of KP32gp34,

eight copies of KP32gp35, four copies of KP32gp36, 12 copies of KP32gp26 and 6

copies of KP32gp27, accounting for 15,154 amino acid residues overall [17]. An

attempt to model the entire inner core of KP32 using AF3 failed. Given the large

size of the inner core, we attempted to model smaller oligomers using AF3.

However, these models did not produce reliable models (pLDDT

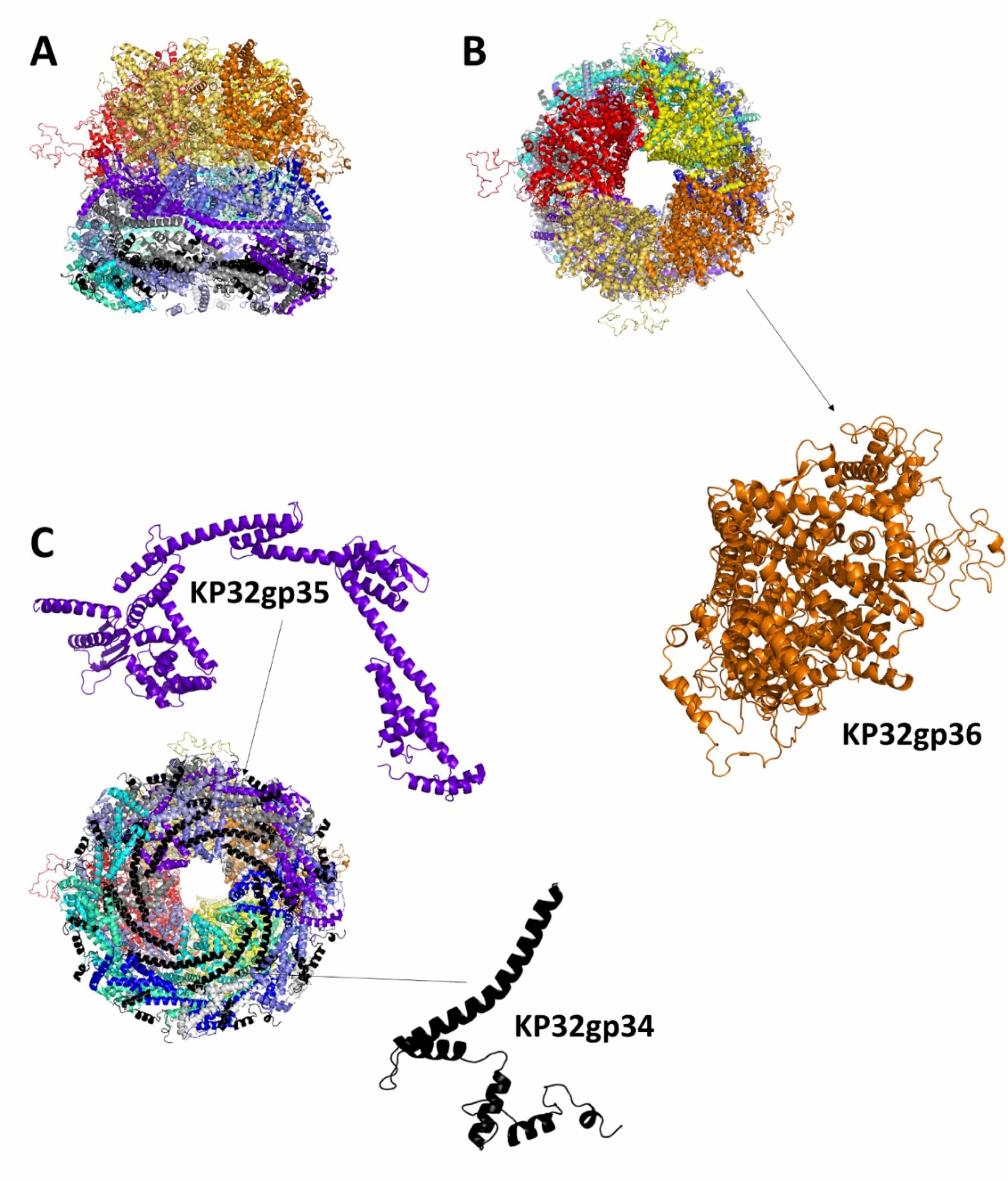

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Structural model of the phage KP32 inner core KP32gp34-KP32gp35-KP32gp36 complex in the mature KP32 phage. Cartoon representations of the complex: (A) side, (B) top and (C) bottom views. The insets show details of the protein monomers composing the complex.

Notably, the described structure of the KP32 inner core refers to the mature form of the phage before infection. Indeed, cryo-electron microscopy of the T7 phage revealed the transient nature of the inner core, which changed conformation after infection. These characteristics are likely shared by the KP32 phage [44, 45, 46].

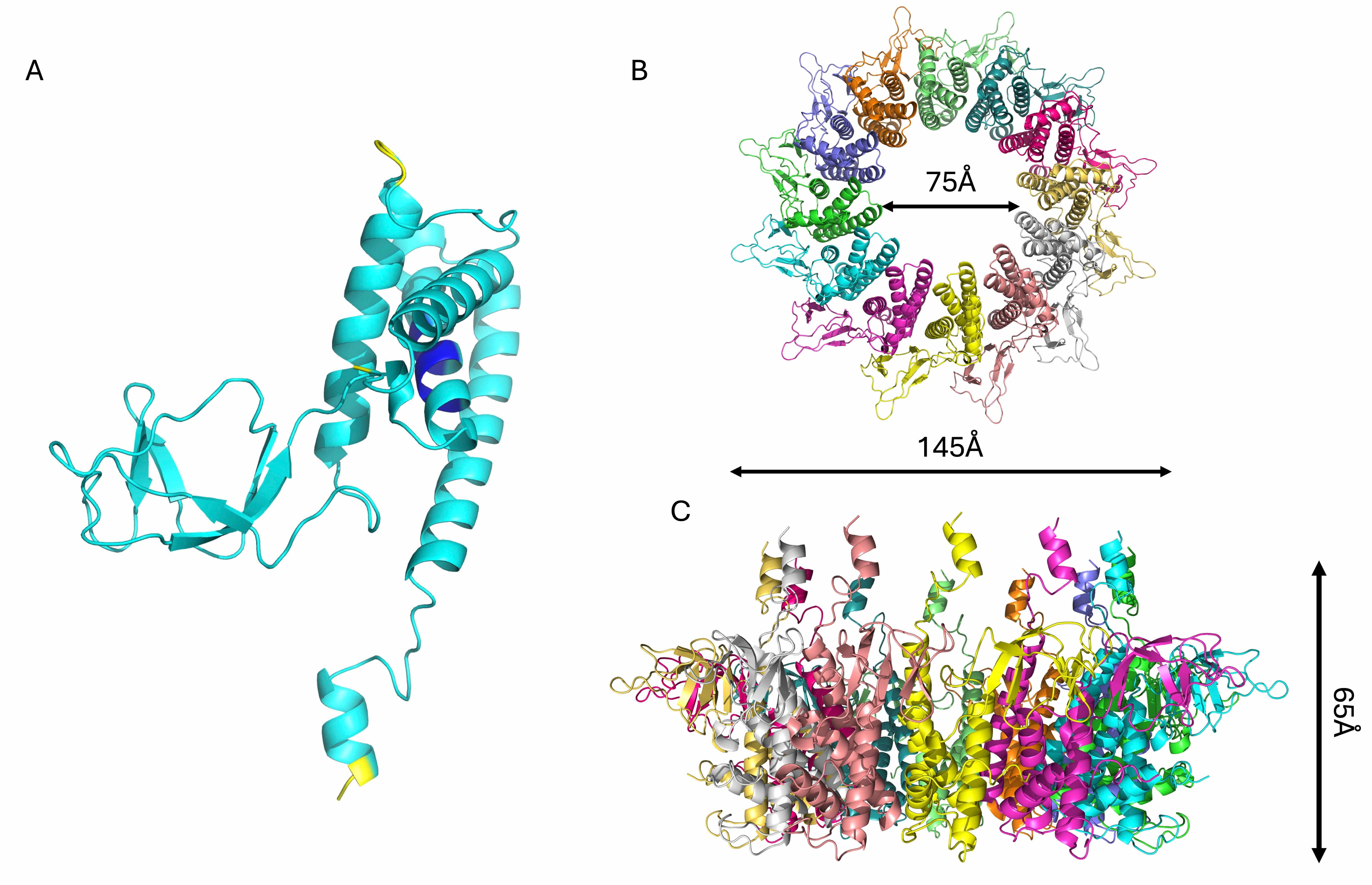

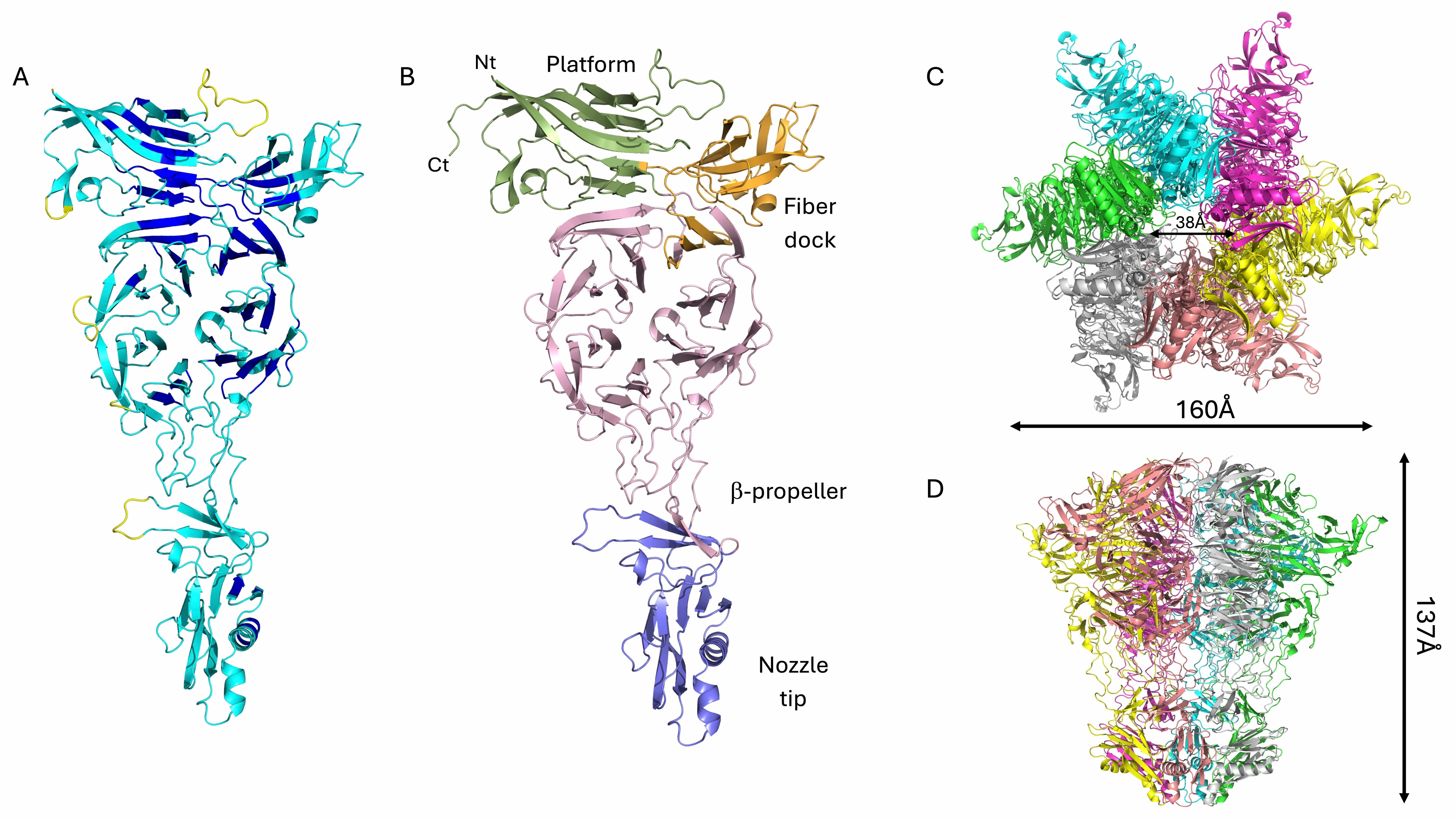

The structures of all the components of the phage KP32 portal–tail complex were

modeled with high confidence (Table 2). The tail is formed by the hexameric

assembly of the protein KP32gp32 (nozzle) and the dodecameric assembly of the

protein KP32gp31 (adaptor) (Fig. 5). KP32gp32 is the tail nozzle protein, forming

the final conduit through which the viral DNA exits during infection. The

structure of the KP32gp32 monomer is composed of a large central

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Structural model of the KP32gp32 nozzle protein. Cartoon

representations of a KP32gp32 monomer, displayed (A) colored according to the AF3

confidence intervals (dark blue, very high (pLDDT

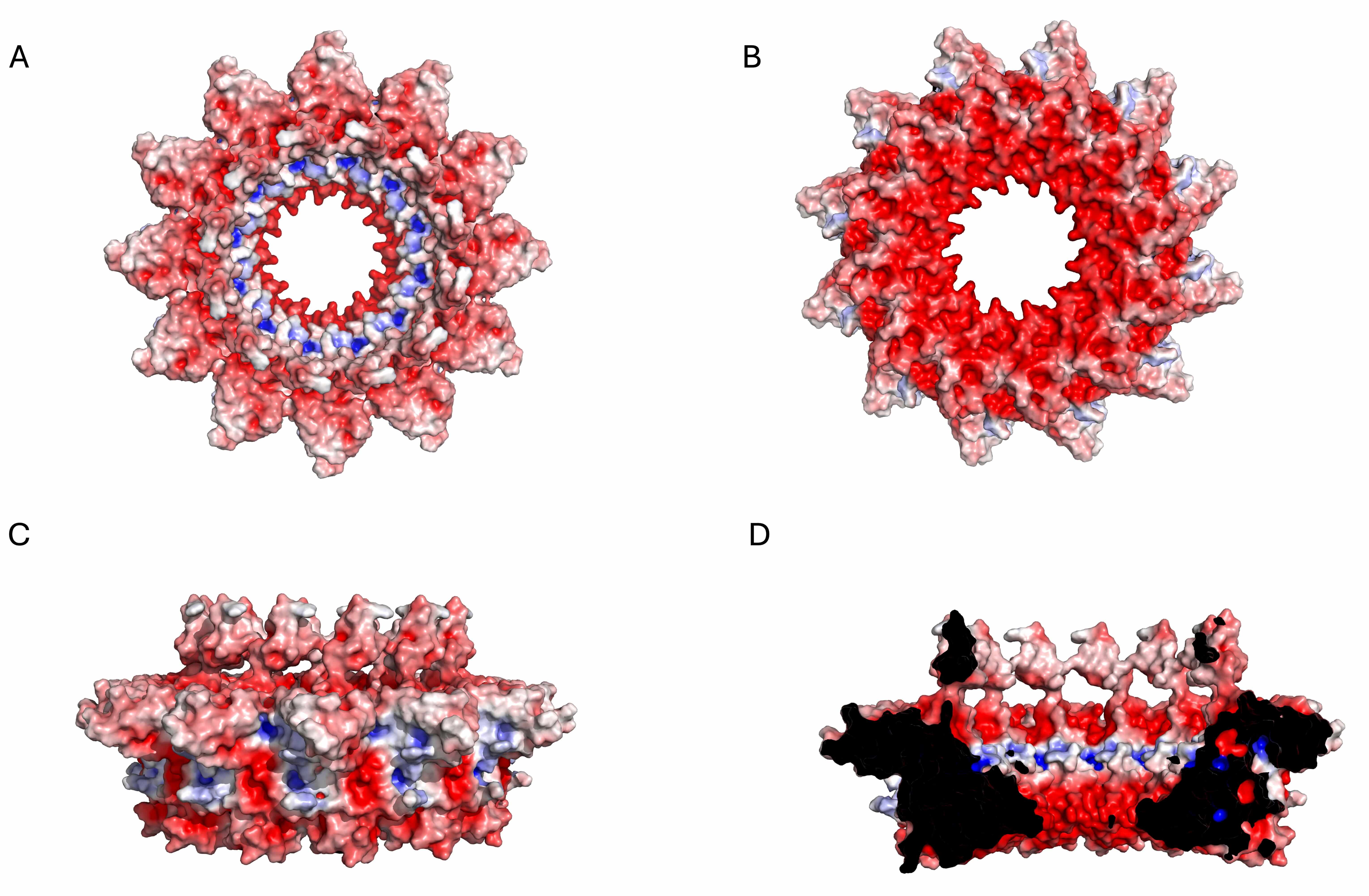

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Electrostatic potential surface of the KP32gp32 nozzle hexameric assembly. (A) Top view, (B) bottom view, (C) side view, and (D) inner section. The red- and blue-colored surfaces represent negative and positive electrostatic potentials, respectively.

Another important element of phage KP32 is the KP32gp31 adaptor, which we have

modeled with good confidence (Table 2). KP32gp31 is homologous (62.2% sequence

identity) to the T7gp11 protein, a key structural component of the tail

apparatus, acting as a gatekeeper and adaptor between the portal protein

(KP32gp28) and the tail nozzle (KP32gp32). The KP32gp31 adaptor assembles into a

dodecameric toroidal ring and acts as a structural bridge between the portal

KP32gp28 proteins and the KP32gp32 nozzle proteins. It is formed by a core

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Structural model of the KP32gp31 adaptor protein. Cartoon

representations of (A) the KP32gp31 monomer, colored according to the AF3

confidence intervals (dark blue, very high (pLDDT

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Electrostatic potential surface of the KP32gp32 adaptor dodecameric assembly. (A) Top view, (B) bottom view, (C) side view, and (D) inner section. The red- and blue-colored surfaces represent negative and positive electrostatic potentials, respectively.

Tail spike depolymerases of the KP32 bacteriophage are specialized enzymatic proteins located at the distal end of the phage’s tail structure [10, 47, 48, 49]. By enzymatically cleaving the glycosidic bonds within the capsule, they degrade the protective polysaccharide layer surrounding the bacterial cell, thereby facilitating phage adsorption and genome injection. Like other depolymerases, they play crucial roles in host recognition and infection [10, 47]. KP32 encodes two structurally related but functionally distinct tail-spike depolymerases, KP32gp37 and KP32gp38, each of which form a stable homotrimer [10, 19, 23]. We have previously shown that the KP32gp37 and KP32gp38 depolymerases exhibit remarkable specificity toward the K3 and K21 capsular serotypes, respectively [10, 19]. The crystal structure of the KP32gp38 depolymerase was determined in its unliganded form [10] and in complex with its degradation product, a pyruvated pentasaccharide, bound to its interchain catalytic site [23]. This depolymerase is formed by an N-terminal region, with a key role in the interaction with KP32gp37 [10, 23], a catalytic domain and two oligosaccharide binding domains (Fig. 9A). Compared with KP32gp38, KP32gp37 presents a more complex and elongated structure. Unlike KP32gp38, KP32gp37 includes an extra helical domain at its C-terminus (Fig. 9B) that displays a strong structural resemblance (DALI Z score = 12.8) to the intramolecular chaperone domain of the phage T5 L-shaped tail fiber, which undergoes autocleavage [23]. Additionally, it includes an extended N-terminal region formed by three coiled coil regions and two rings of lectin domains (Fig. 9B). The structure of the complex between the two depolymerases, modeled using AF3 [23], shows the sole involvement of the N-terminal helices of KP32gp38 in the binding of KP32gp37, in full agreement with our previous calorimetric studies [10].

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Structural models of phage KP32 depolymerases. Cartoon representations of (A) the KP32gp38 crystal structure, (B) the KP32gp37 AF3 model and (C) the complex between KP32gp37 and KP32gp38 computed with AF3.

The N-terminal 150 residues of KP32gp37 have a strong sequence and structural similarity to the N-terminal region of the tail fiber gp17 from the mature E. coli phage T7 (PDB code 7EY9, Dali Z = 16.0; PDB code 8DSP, Dali Z = 18.8) (sequence identity 45%) [13]. Analogous to T7, we propose that the KP32 portal directly engages KP32gp37 through interactions with its N-terminal adaptor. In turn, KP32gp37 engages the KP32gp38 depolymerase through interactions with its N-terminus (Fig. 9) [23].

The entire phage KP32 was reconstructed on the basis of the AI-modeled structures of its components and the available structural information on the E. coli phage T7 [12, 13, 15, 18, 44]. A scheme of the organization of the entire phage KP32 virion is reported in Fig. 10A. From inside the icosahedral capsid of phage KP32 toward its tail, a vertex pentamer consisting of five KP32gp30 chains is replaced by the phage portal, formed by a dodecameric assembly of KP32gp28 proteins. This crown-like portal domain faces five KP32gp30 hexamers at the inner side of the capsid, adjacent to the missing pentamer (Fig. 10B). The portal connects to the phage tail through a tail adaptor made by a dodecameric assembly of KP32gp31 proteins. A tail tubular protein, KP32gp32, then stacks below KP32gp31 and extends the DNA translocation channel; there, KP32gp32 acts as the central nozzle that seals the DNA channel until infection begins (Fig. 10A). As previously mentioned, the tapered internal cylinder sitting on top of the portal and made by the ejection proteins KP32gp34, KP32gp35 and KP32gp36 could not be reliably modeled by AF3, likely due to both size limits and the different conformational states of these proteins depending on the functional state. Indeed, the homologous proteins in the T7 phage form a transient tunnel that spans the bacterial envelope from the outer membrane to the cytoplasm, allowing the phage genome to pass through without being degraded or exposed [46].

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

The phage KP32 virion structure. (A) Simplified sketch showing the position of each phage KP32 protein in the phage structure. (B) A 3D model of the entire phage KP32 virion, excluding the inner core/ejectosome.

In addition to being a gate for the KP32 genome, the nozzle is also the attachment site of the capsular depolymerases via noncovalent interactions and structural complementarity. Indeed, due to the sequence and structural similarity of the N-terminal 150 residues of the KP32gp37 tail spike depolymerase with the N-terminal region of the tail fiber gp17 from the mature E. coli phage T7 (PDB code 7EY9), we could model the interaction of KP32gp37 with the KP32gp32 central nozzle (Fig. 10). In turn, the KP32gp38 depolymerase does not directly interact with the KP32 central nozzle, but it hijacks KP32gp37 through its N-terminal region. Consistently, we have shown that a truncated form of KP32gp38, deprived of its N-terminal 29 amino acids, is unable to bind KP32gp37 [10]. In this branched model, the KP32 portal carries twelve depolymerase molecules on a single virion, which are arranged in six branches. This arrangement allows the depolymerases to extend outward, enabling them to bind and degrade the CPS on the bacterial surface (Fig. 10).

The ability to model complex phage structures opens immense possibilities, from decoding phage infection mechanisms to engineering novel phages for therapeutic use against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. By illuminating previously elusive structural insights, AF3 helps transform phage research from trial-and-error experimentation into predictive science. The groundbreaking ability of AF3 to model large biomolecular structures such as bacteriophages represents a profound leap forward in computational biology. Indeed, phage structures help identify novel antibacterial proteins and enzymes that can be repurposed into therapeutics, thus serving as alternatives to traditional antibiotics.

The Klebsiella phage KP32 is a compelling model for studying phage biology and engineering, especially because of its sophisticated receptor-binding proteins and depolymerase activity. Indeed, it presents peculiar features that offer insights into serotype-specific phage targeting. This phage presents a dual depolymerase system that targets distinct capsular serotypes (K3 and K21/KL163) of K. pneumoniae. We have previously shown that these depolymerases constitute promising antivirulence strategies [23]. By stripping the protective capsule from K. pneumoniae, bacteria are sensitized to immune responses and antibiotics, offering a nonlethal way to disarm pathogens. We have shown here that phage KP32 presents high sequence and structural similarity to the E. coli phage T7. On the basis of these similarities, we can predict the functions of specific phage-composing proteins (Table 3). Almost all protein components of KP32 could be structurally predicted using AF3, including the full capsid and the portal-tail complex, thus demonstrating the high level of performance of this tool. The sole KP32 component that could not be predicted is the inner core/ejectosome, for which homology modeling was needed. This inner core is expected to be highly dynamic, as observed for the T7 phage. Indeed, upon infection, the T7 phage ejects the three inner core proteins T7gp14, T7gp15, and T7gp16, which reassemble into a trans-envelope conduit spanning the bacterial outer membrane, the periplasm, and the inner membrane [44, 45]. T7gp14 forms a pore in the outer membrane, whereas T7gp15 undergoes a dramatic conformational change from the eightfold-symmetric core in the capsid to a sixfold-symmetric tubular structure forming a 210 Å-long channel [46].

| Structure assembly | Notes | |

| Capsid | Composed of 11 pentamers and 60 hexamers of the major capsid protein (KP32gp30). It forms a 20-faced icosahedron with a diameter of ~55 nm | One of the 12 capsid vertices is replaced by a 12-fold symmetric portal complex (KP32gp28), which serves as the entry/exit point for DNA |

| Inner core | Composed of a 4-fold KP32gp36 ring, an 8-fold KP32gp35 ring, and a putative eightfold KP32gp34 ring | KP32gp34 anchors to the tail nozzle. Similar to the T7 phage, these proteins likely undergo remarkable conformational changes to form the trans-envelope channel |

| Portal | Made of 12 copies of KP32gp28, forming a 12-fold symmetric ring of diameter 17 nm and height ~13 nm | It connects the capsid to the tail. On top of the portal, the ejectosome proteins facilitates DNA ejection |

| Tail | Formed by a hexameric assembly of KP32gp32 (nozzle) and a dodecameric assembly of KP32gp31 (adaptor). Overall, the nozzle-adaptor complex presents a diameter of ~16 nm and height of ~20 nm | 12 tail spike depolymerases (6 KP32gp37 and 6 KP32gp38) are arranged around the KP32 nozzle base. The branched depolymerase system is anchored to the nozzle through KP32gp37 |

An elegant choreography of proteins is indeed needed to allow the delivery of the phage KP32 ~40 kb genome with precision and speed (Table 3). The infection event likely starts with the tail fibers binding the host CPS. This event is expected to trigger a conformational change in the hexameric assembly of the KP32gp32 tail nozzle, opening the DNA channel and allowing the inner core proteins KP32gp34, KP32gp35 and KP32gp36 to be released and assemble into a tube-like structure that penetrates the bacterial envelope, enabling the phage genome to enter the cytoplasm.

A fascinating and essential feature in the assembly of phages such as KP32 and T7 is symmetry mismatch (Fig. 10). Like other tailed phages, KP32 presents a 12-fold symmetric portal protein embedded at a unique vertex of the icosahedral capsid, which itself has 5-fold symmetry at each vertex (Fig. 11A,B) [13, 18]. This mismatch, 5-fold vs 12-fold, is a structural asymmetry at the portal vertex. Another symmetry mismatch, between the 12-fold tail adaptor and the 6-fold tail nozzle, creates a nonaligned interface between these two components (Fig. 11C,D). In phage T7 infection, the T7gp7.3 protein, which is homologous to KP32gp27, promotes the assembly of the nozzle into the adaptor [17]. Symmetry mismatch has important functional implications for large and dynamic structures and is present in the holes of phages [50]. Indeed, it facilitates rotational flexibility, which is thought to help the motor translocate the DNA efficiently into the capsid. As such, it acts as a mechanical gate, regulating the transition from a stable virion to an active ejection state and helps ensure that the DNA is not prematurely released and is ejected only upon proper host recognition. Upon receptor engagement, KP32gp32 undergoes conformational changes that open the channel and initiate genome release. In essence, symmetry mismatch is a clever biological strategy that enables complex viral machinery to operate with precision and adaptability.

Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Symmetry mismatches in the phage KP32 structure. Cartoon representation of the modeled phage KP32, deprived of the tail spikes for clarity. The insets (A–D) show top views of each KP32 component, with an indication of its symmetric arrangement.

The advent of AlphaFold has revolutionized structural biology by enabling high-accuracy predictions of protein 3D structures directly from amino acid sequences. For bacteriophages such as Klebsiella phage KP32, which are increasingly studied for their therapeutic potential against multidrug-resistant bacteria, AlphaFold has offered a powerful tool to decode the architecture of poorly annotated or novel proteins. Complementing sequence information with recent literature data on homologous bacteriophages has helped to bridge the gap between sequence data and biological insight, offering a more complete picture of the phage KP32 molecular machinery. Although computational models offer novel functional hypotheses on complex macromolecular assembly, they may lack accuracy in the case of high flexibility and conformational heterogeneity, as well as for large systems, where high-performance computational sources are needed. As a general approach, computational studies should be included in a more integrated approach, where computations support experimental studies. In this specific case, experimental methods such as cryo-electron microscopy or X-ray crystallography remain essential to confirm, refine, and contextualize AlphaFold models, ensuring that structural hypotheses translate into biologically meaningful insights.

All data and protocols are available from the corresponding authors.

VN and RB conceived the work and wrote the original draft. VN and FS performed the computational analyses. MP and GB analysed the data. ZDK contributed to data interpretation. VN, RB, ZDK, FS, MP and GB revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to thank Maurizio Amendola and Massimiliano Mazzocchi for their technical support.

This work was supported by the project INF-ACT “One Health Basic and Translational Research Actions addressing Unmet Needs on Emerging Infectious Diseases PE00000007”, PNRR Mission 4, EU “NextGen-erationEU”- D.D. MUR Prot.n. 0001554 of 11/10/2022, CUP B53C20040570005, by the National Science Centre, Poland (grant UMO-2017/26/M/NZ1/00233) and by the project TENET - “Targeting bacterial cell ENvelope to reverse rEsisTance in emerging pathogens”, 202288EJ8B, funded by Next Generation EU, Mission 4, CUP B53D2301595 0006.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.