1 NHC Key Lab of Reproduction Regulation, Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Reproductive Health Drugs and Devices, Shanghai Institute for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Technologies, School of Pharmacy, Fudan University, 200237 Shanghai, China

2 Department of Urology, Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital, Tongji University, 200040 Shanghai, China

Abstract

In contemporary gene therapy research, recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) has emerged as a pivotal delivery vehicle due to its favorable safety profile and capacity for sustained transgene expression. The most commonly utilized rAAV variants are hybrid vectors constructed by packaging the AAV2 genome within the capsid proteins of alternative serotypes (e.g., AAV1, AAV5, AAV8, or AAV9). This chimeric design combines the stable genomic integration and long-term expression characteristics inherent to AAV2 with the distinct tissue tropisms conferred by different capsid serotypes. Consequently, these engineered rAAVs exhibit enhanced organ-targeting specificity, enabling more efficient and selective gene delivery to desired tissues while minimizing off-target effects.

To identify the optimal hybrid vector for germ cell-directed gene delivery in mice, ten distinct chimeric AAV variants were generated by pseudotyping the AAV2 genome with diverse capsid proteins, followed by microinjection into seminiferous tubules via the efferent ducts. Transduction efficiency was comparatively evaluated at 4 weeks post-injection.

We demonstrated that AAV2/9 mediated robust and widespread enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression in the mouse testis. Through immunofluorescence assays, we demonstrated that AAV2/9 demonstrated the capability to express in nearly all testicular cells, with remarkable efficiency and durability.

AAV2/9 demonstrated superior efficacy as a gene delivery vector for murine testicular germ cells without observable adverse effects on testicular development or spermatogenesis. This favorable safety profile, combined with high transduction efficiency establishes AAV2/9 as a promising candidate for therapeutic gene transfer to testicular germ cells. Collectively, our study identifies AAV2/9 as a premier vector for germ cell-directed gene therapy, providing crucial preclinical evidence to inform capsid selection for treating male infertility.

Keywords

- gene therapy

- adeno-associated virus

- capsid proteins

- germ cells

- microinjection

The advent of genome editing technologies has unlocked the potential to directly target and modify genomic sequences across nearly all eukaryotic cells. Genome editing technologies have significantly advanced genetic disease research and driven the development of precise cellular and animal models, with broad applications in fundamental research, biotechnology, and biomedical fields [1, 2, 3]. Currently, in vivo gene-editing delivery technologies include viral vector-based delivery, lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-mediated delivery, and virus-like particle (VLP)-assisted delivery [4]. Notably, the former two have achieved preliminary success in recent clinical trials and hold promise for becoming powerful in vivo gene-editing therapeutic approaches in the future [5, 6, 7, 8]. Owing to its low clinical pathogenicity, diverse tissue tropism, and sustained transgene expression, adeno-associated virus (AAV) has become a key vector in clinical gene therapy. Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV), engineered from the non-pathogenic wild-type AAV for enhanced specificity, has emerged as a valuable tool for treating various diseases [9]. Male infertility stemming from genetic mutations stands out as a critical category of infertility. At present, no clinical methodologies with proven efficacy are available to satisfy this particular medical requirement [10]. Thus, employing AAV-mediated delivery as a therapeutic approach for male testis related diseases may offer a potential solution to restore fertility in males affected by gene mutations. This innovative strategy holds promise for dressing the unmet medical need in treating male infertility. Further research and development in this field could pave the way for effective gene-therapy-based interventions to combat male infertility caused by genetic factors.

As mentioned earlier, AAV was initially identified as a contaminant in cell cultures, and AAV2, the most extensively studied and commonly utilized serotype, was recognized in a similar manner [11]. It is worth noting that the vectorized serotypes offering the most clinical promise have often been those derived from natural sources. A prime example of this is AAV9, which was discovered in human liver tissue [12]. Currently, thirteen different human AAV serotypes (AAV1-13) have been discovered [13]. They are characterized by distinct capsid proteins and show varied tropisms for diverse cell and tissue types [14]. Nevertheless, natural AAV serotypes possess several shortcomings, such as less than optimal transduction efficiency, pre-existing immunity, and insufficient tissue specificity, which impede their therapeutic efficacy. In response to these challenges, substantial endeavors are being directed toward the engineering of novel AAV capsids. Rational design employs structural insights to enhance capsid properties, directed evolution facilitates the unbiased selection of superior variants, and machine learning leverages computational analysis of high-throughput screening results to accelerate discovery and enable predictive algorithms [15]. Collectively, these approaches have led to the development of novel capsids that exhibit enhanced transduction efficiency, reduced immunogenicity, and improved tissue targeting. Currently, fewer than 12 AAV serotypes are employed as vectors in clinical trials, among which AAV2 is the most frequently used. Notably, more updated and effective capsids, including AAV8, AAV9, and AAVrh.10 are being employed in an increasing number of trials [11]. Recombinant adeno-associated viruses (rAAVs) commonly used nowadays are hybrid viral vectors composed by combining the AAV2 genome with capsid proteins from different serotypes, often labeled as rAAV2/N (N represents distinct serotypes). These chimeric vectors retain the stable transgene expression properties of the AAV2 genome while acquiring the tissue — specific tropism of the pseudotyped capsid, thereby exhibiting enhanced organ — targeting capabilities [16]. The selection of an optimal capsid is therefore critical. This screening strategy is designed not only to identify serotypes with high tropism but also to prioritize those compatible with scalable manufacturing. While serotypes like AAV9 exhibit desirable in vivo tropisms, their native genomes can present challenges for high-titer production. The AAV2-based hybrid system, in contrast, benefits from the most refined and efficient production platform available. Consequently, identifying a chimera like AAV2/9 that combines the superior in vivo delivery of a capsid like AAV9 with the production advantages of the AAV2 genome represents an ideal outcome, ensuring that the identified vector is both biologically effective and practically feasible for therapeutic development.

Despite the promising potential of AAV mediated gene delivery for testicular gene therapy, its application is severely hampered by a critical, unmet challenge: the lack of AAV vectors capable of efficient transduction across the blood-testis barrier and, more importantly, into the spermatogenic lineage within the seminiferous tubules. While AAVs can be delivered directly into the testicular interstitium or seminiferous tubules, most naturally occurring serotypes exhibit poor efficiency or undesirable cellular tropism for the intended germ cell targets [17]. Currently, AAV8 is among the most widely utilized serotypes for testicular delivery. However, a significant limitation has emerged from a recent study: AAV8 primarily transduces interstitial cells in the testes [18]. This somatic cell-restricted tropism renders AAV8 suboptimal for therapeutic strategies aimed at correcting genetic defects in male germ cells, which are a leading cause of hereditary infertility.

To date, there has been no systematic, side-by-side evaluation of the transduction efficiency of different AAV serotypes, particularly those derived from the AAV2 genome, specifically for germ cells in testicular tissue. The identification of a serotype with superior germ cell tropism is therefore a pivotal and unresolved prerequisite for advancing AAV-based gene therapies for male infertility.

This study was designed to address this exact gap. We aim to identify the optimal AAV serotype for targeting testicular germ cells by conducting a comprehensive comparison of the gene delivery efficiency of ten distinct AAV2-based hybrid serotypes in mouse testes. Our findings provide a powerful and efficient vector for germ cell-directed gene therapy, offering a precise tool to overcome the current delivery bottleneck.

AAV viral vectors were prepared by OBiO Technology (Shanghai) Corp., Ltd. utilizing their standardized production process. This comprehensive process includes: transfection based on a triple plasmid system, viral packaging in adherent or suspension HEK293 cell culture systems, harvest of crude viral lysate via cell lysis, purification through sequential steps such as affinity chromatography followed by ion exchange chromatography, and final quality control measures including titer determination and sterility testing, resulting in a high-purity AAV vector suspension meeting stringent specifications. The AAV2 genome includes the Cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP) fluorescence signal as a marker.

Mice used in experiments were purchased from Nantong Jingqi Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd. Mice (4-week-old) were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of 2.5%

tribromoethanol (T48402, Sigma Chemical Co.St.Louis, MO, USA) (0.2 mL/10 g body

weight). For each serotype, at least three mice received a unilateral

intratesticular injection. A standardized volume of 20 µL, containing 1.0

Fresh testicular tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (158127, Sigma

Chemical Co.St.Louis, MO, USA) at 4 °C for

Mouse testes were immediately dissected and fixed in Bouin’s solution (HT10132, Sigma Chemical Co.St.Louis, MO, USA) for 24 hours at 4 °C to preserve seminiferous epithelium architecture. Tissues were then washed in 70% ethanol to remove residual picric acid, dehydrated through graded ethanol series (70% to 100%), cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (5 µm thickness) were cut using a rotary microtome (Leica RM2235, Ernst Leitz Corp., Wetzlar, Germany). After deparaffinization and rehydration, sections were stained with hematoxylin (H3136, Sigma Chemical Co.St.Louis, MO, USA) for 8 minutes, rinsed in running tap water, differentiated in 0.5% acid alcohol, and blued in Scott’s tap water substitute. Counterstaining was performed in eosin Y (0.5% aqueous) for 90 seconds. Sections were dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and mounted with Distyrene, Plasticizer and Xylene (DPX) (MM1410, MKBio, Shanghai, China). Histological evaluation mainly focused on the diameter of the seminiferous tubules, the thickness of the germinal epithelium and the morphology of spermatogenic cells under light microscopy (VS200 digital scanning microscope, Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Frozen sections were washed with Phosphate Buffered Saline with Tween 20 (PBST) (P2272 & 93773, Sigma Chemical Co.St.Louis, MO, USA) and PBS. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (10 min, room temperature). After further washing, slides were mounted.

Whole-mount testes were imaged under a stereo fluorescence microscope (Leica M205FA, Ernst Leitz Corp., Wetzlar, Germany). Immunofluorescent sections were imaged using a confocal microscope (A1, Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Whole testes were subjected to mechanical dissociation to obtain a single-cell

suspension. Briefly, intact testes were placed onto a 70 µm nylon mesh cell

strainer. Gentle mechanical disruption was achieved by applying pressure with a

sterile syringe plunger, followed by meticulous trituration across the mesh

surface. The dissociated tissue was then rinsed thoroughly with ice-cold PBS to

facilitate cell passage through the filter. The resulting cell suspension was

collected from the filtrate. To remove residual debris and ensure sample purity,

the harvested cells underwent two sequential washes with PBS via centrifugation

(300

The fluorescence intensity data comparing transduction efficiency across the ten

AAV serotypes were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Statistical significance was defined as p

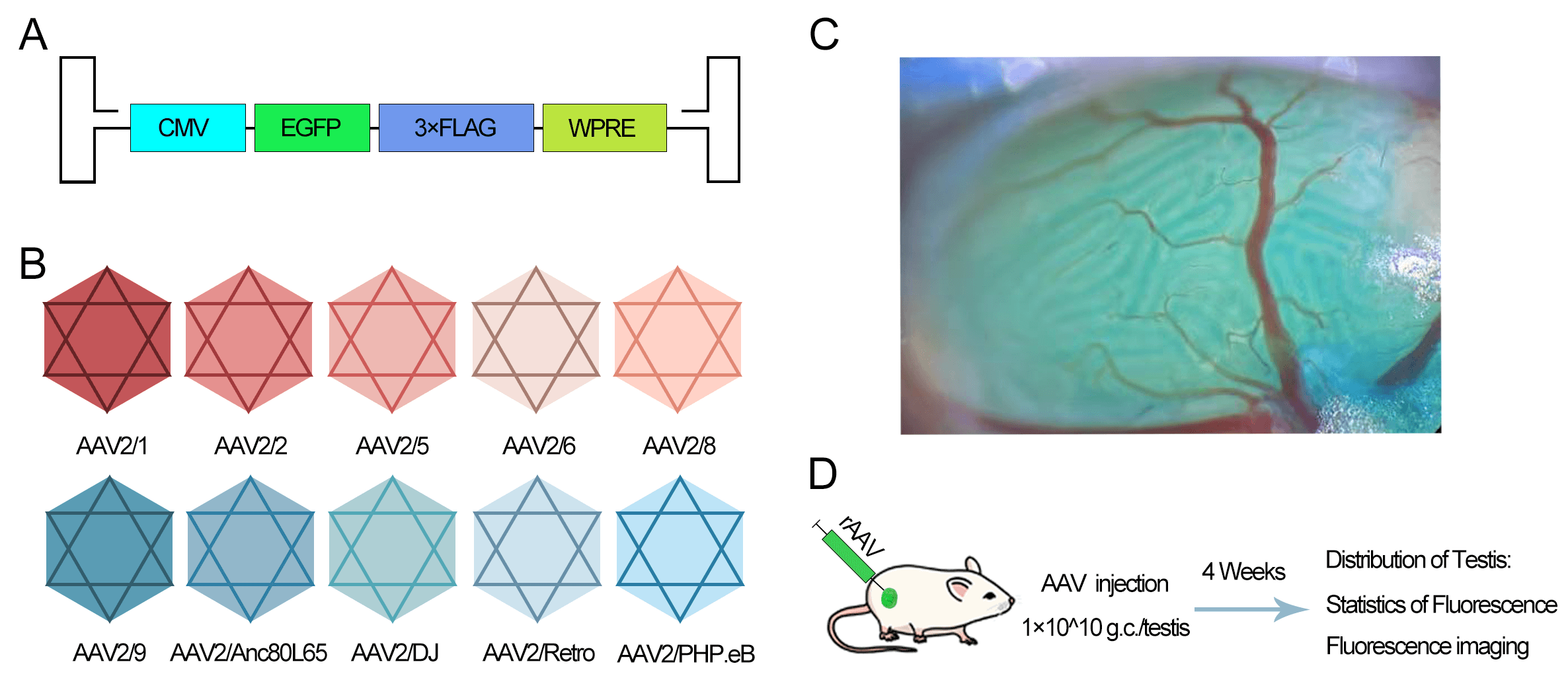

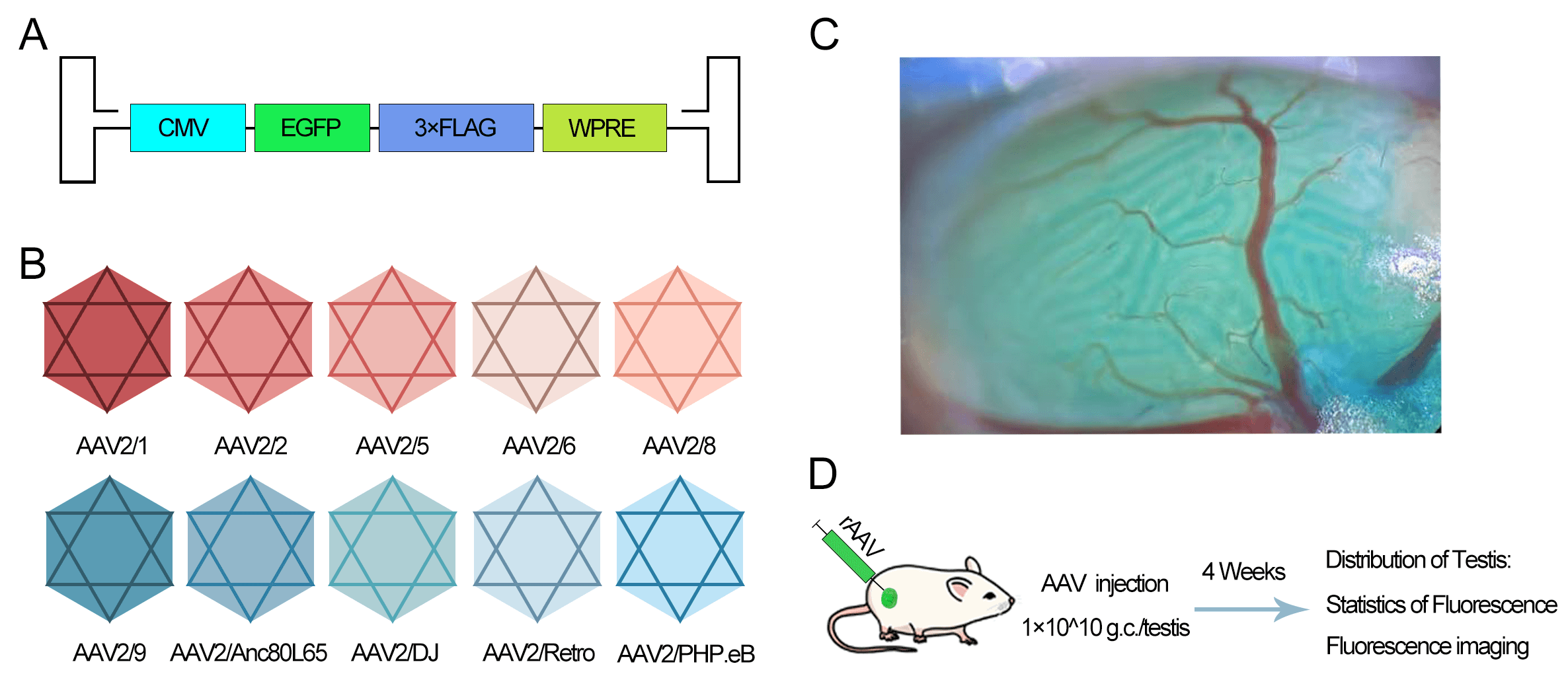

To evaluate the expression efficacy of AAV serotypes, we constructed hybrid

viral vectors by combining the AAV2 genome (containing CMV promoter and EGFP)

with various capsid proteins (AAV2/1, 2/2, 2/5, 2/6, 2/8, 2/9, 2/Anc80L65, 2/DJ,

2/Retro, 2/PHP.eB) (Fig. 1A,B). The vectors were injected into the seminiferous

tubules via the efferent ducts (Fig. 1C). Each testis received 1

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design for evaluating the transduction efficiency

of different adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotypes in the mouse testes. (A)

Schematic of the AAV2 genome construct containing the Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

promoter and Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP) reporter. (B) List of ten

hybrid AAV serotypes generated by pseudotyping the AAV2 genome with various

capsid proteins. (C) Illustration of intratesticular injection via the efferent

duct. The blue dye represents Fast Green used as a tracer. (D) Timeline of the

experiment: unilateral injection into testes of 4-week-old male mice (n

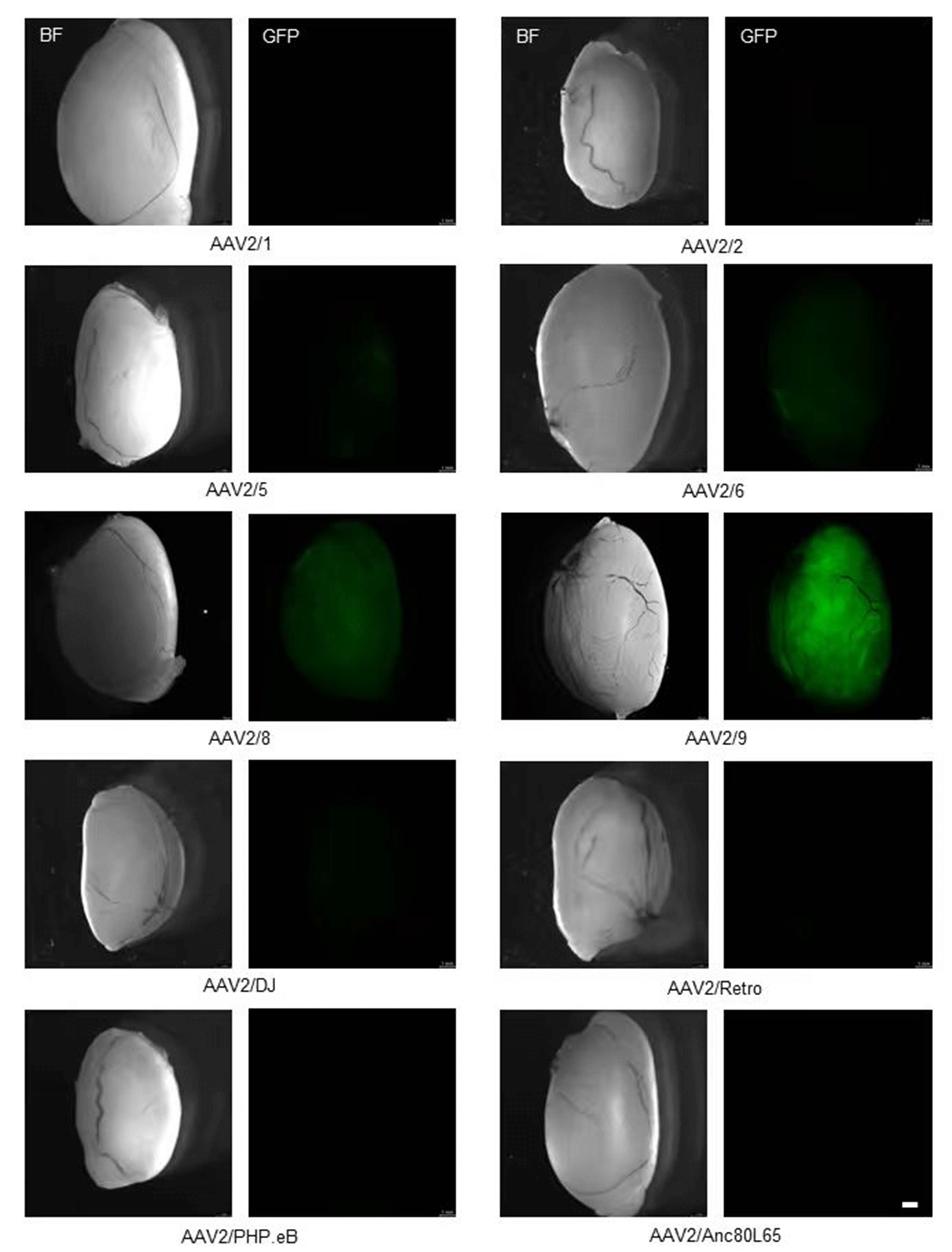

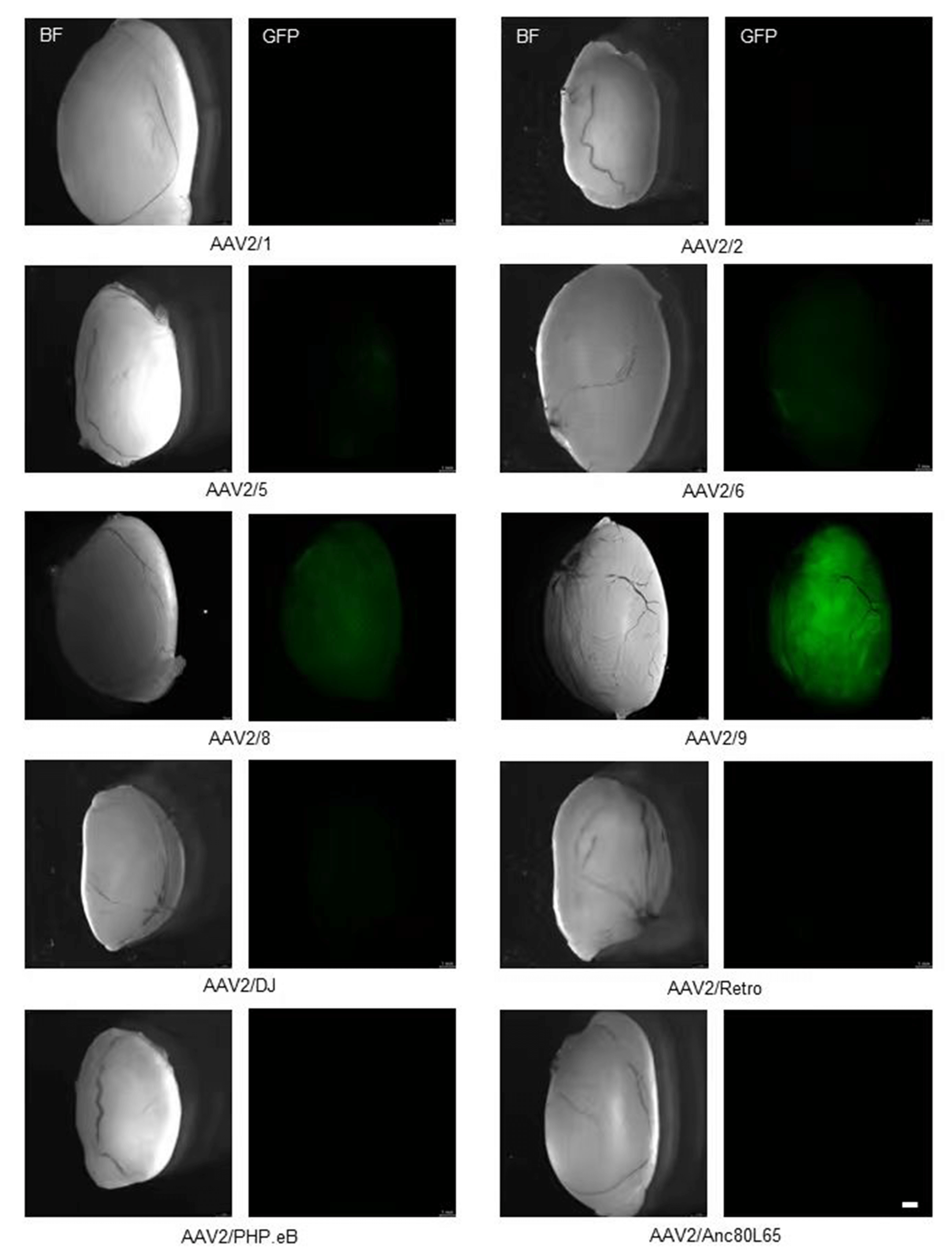

At 4 weeks post-injection, AAV2/9-injected testes exhibited the most intense and widespread green fluorescence throughout the seminiferous tubules. AAV2/8 showed the second-highest intensity. AAV2/5 and AAV2/6 exhibited weak fluorescence, while the other serotypes showed barely detectable EGFP expression (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Transduction efficiency of ten AAV serotypes in testis. Representative stereomicroscopy images showing EGFP expression in testes 4 weeks post-injection. Scale bar: 1 mm.

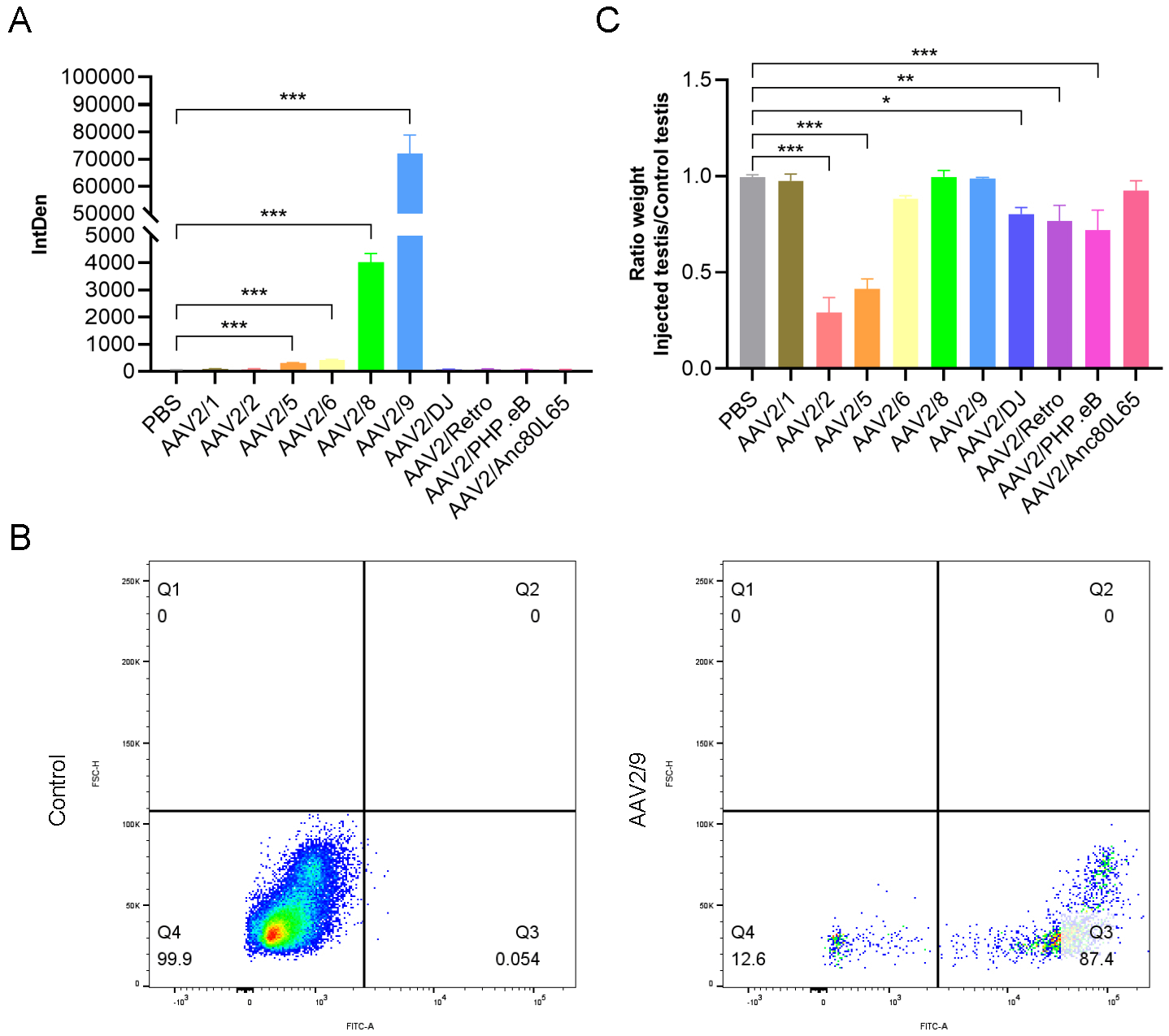

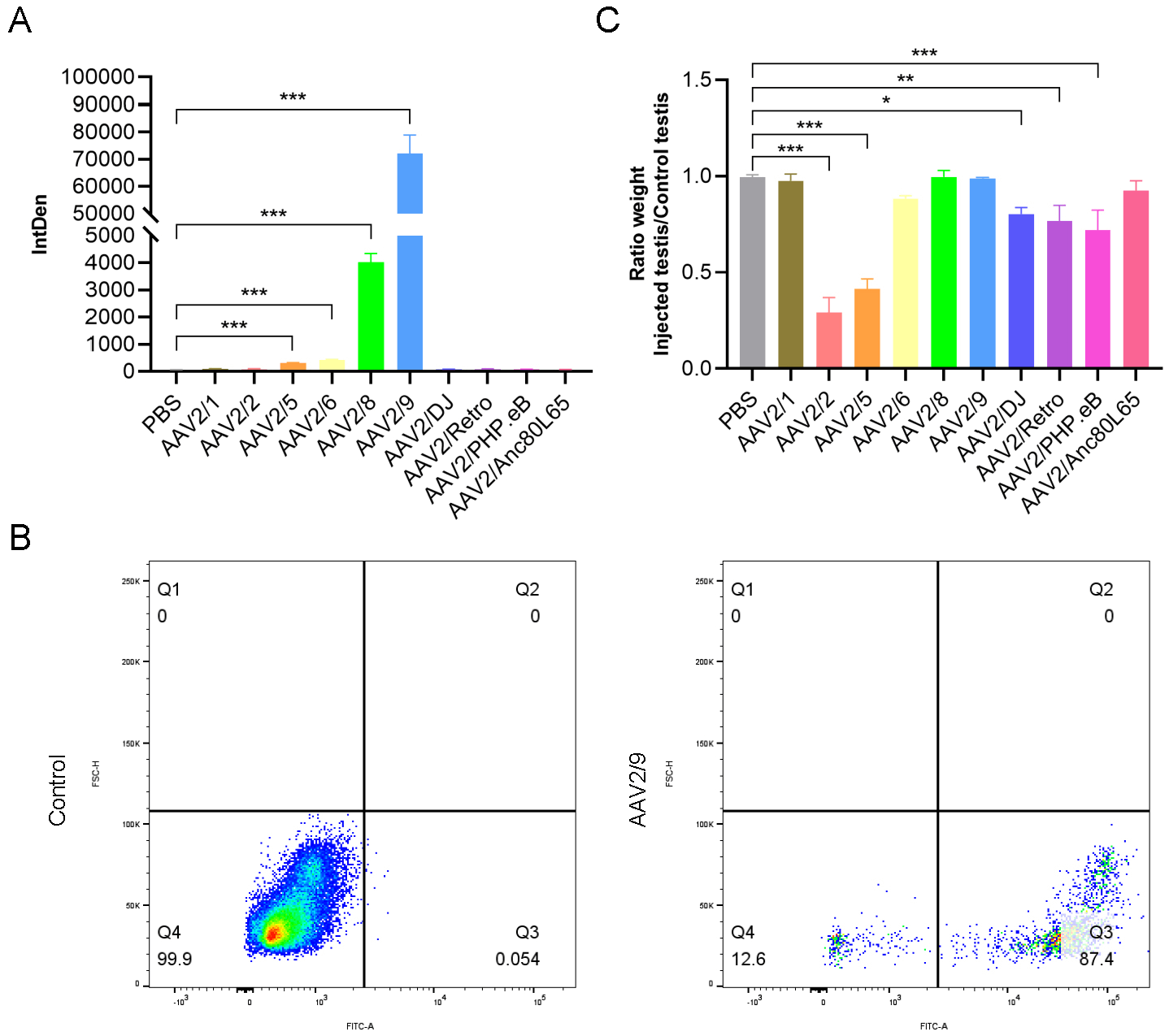

Marked variations in transduction efficiency were observed. AAV2/9 was the most efficient, outperforming all others. AAV2/8 followed, but its fluorescence intensity was approximately 18-fold lower than AAV2/9 (Fig. 3A). Flow cytometry analysis of AAV2/9-transduced testes revealed an overall transduction efficiency of approximately 87% in testicular cells (Fig. 3B). We observed that the injection of different AAV serotypes had varying effects on testicular growth and development. Specifically, AAV2/1, AAV2/8, AAV2/9, and AAV2/Anc80L65 exerted almost no detectable on testicular development. In contrast, AAV2/6, AAV2/DJ, AAV2/Retro, and AAV2/PHP.eB showed minimal effects on testicular growth. Notably, AAV2/2 and AAV2/5 had the most significant adverse effects on testicular development, with the testicular weights being less than half of those of the non-injected testes (Fig. 3C). These findings were quantified by comparing the weights of injected and non-injected testes, providing a clear metric of the differential impacts of each AAV serotype on testicular growth.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Effects of different AAV serotypes on testicular infection and

development. (A) Quantification of fluorescence intensity in testes injected

with different AAV serotypes (n

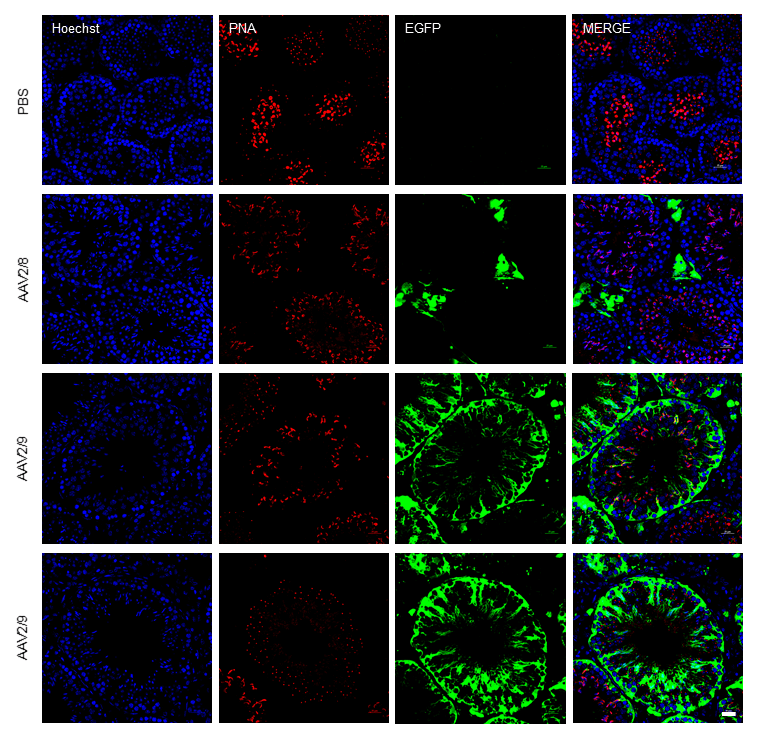

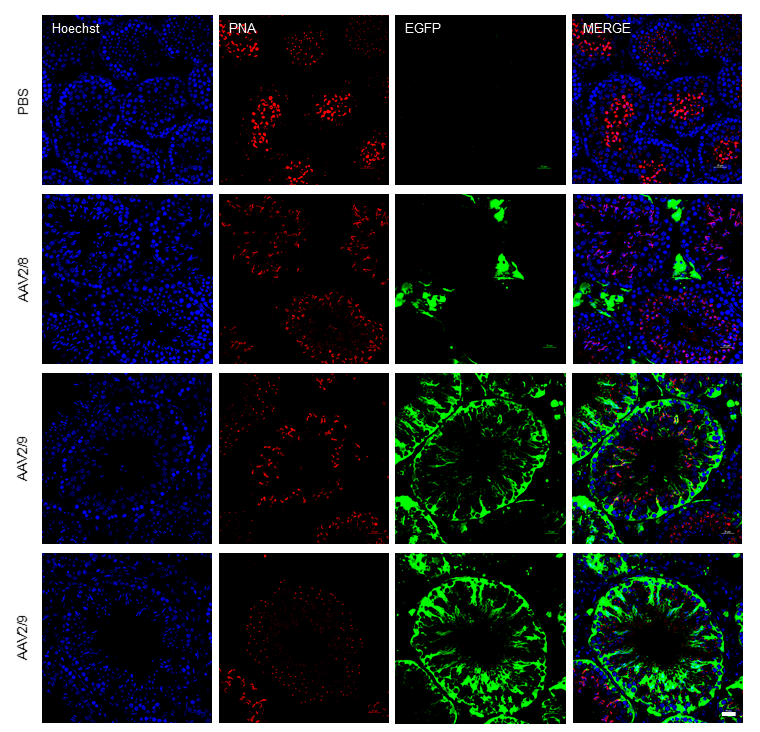

Among the serotypes evaluated, most exhibited limited tropism for testicular tissue. Only AAV2/9 exhibited remarkably high transduction efficiency, producing a strong green fluorescence signal in the testes. We then prepared frozen sections of AAV2/9-infected testes and performed immunofluorescence analysis. Hoechst was used to label cell nuclei, while the green fluorescence signal indicated cells transduced and expressing the AAV2/9 vector. The analysis revealed that the green fluorescence signal was evidently expressed in various testicular cells, including interstitial cells, germ cells, and Sertoli cells. This finding suggests that AAV2/9 has a broad tropism for testicular cells. AAV2/9 possesses capsid proteins that likely exhibit high affinity for receptors uniquely or abundantly expressed on testicular cells. This specific interaction facilitates efficient viral entry into these cells, a critical step for transduction. Other AAV serotypes may lack capsid configurations optimized for these receptors, leading to reduced binding and transduction efficiency. Testicular tissue is an immune-privileged site, characterized by reduced immune surveillance. This environment minimizes immune clearance of the AAV2/9 vector, allowing prolonged viral persistence and increased opportunities for cellular entry. Pre-existing immunity against AAV2/9 or innate immune responses may be less effective here, enhancing AAV2/9’s efficacy compared to serotypes that are more susceptible to immune elimination in non-privileged tissues. The combination of receptor-specific tropism and immune evasion creates a cumulative advantage for AAV2/9. Even if other serotypes bind receptors effectively, they may not benefit from the same immune privilege. Conversely, a serotype with immune evasion advantages in other tissues might lack the receptor specificity required for testicular targeting. These factors may collectively contribute to the superior transduction efficiency of AAV2/9 in the testicular tissue compared to other AAV serotypes. Using Hoechst for nuclear staining and Peanut agglutinin (PNA) for acrosome labeling to compare PBS, AAV2/8 and AAV2/9-EGFP transduction patterns, we observed no green fluorescence expression in the PBS-injected group. AAV2/8 expression was detected exclusively in testicular Leydig cells, consistent with previous findings. In contrast, AAV2/9 transduced both testicular somatic cells (including Leydig cells and Sertoli cells) and all spermatogenic cell types, exhibiting particularly high green fluorescence expression efficiency within the germ cell lineage and the representative images showing two different sectional views of AAV2/9-transduced seminiferous tubules (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

AAV2/9 functional transduction detected by fluorescent imaging. Comparison of immunofluorescence staining showing the expression and distribution of fluorescence in the testis following injection of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), AAV2/8, and AAV2/9. Scale bar: 25 µm. (Blue: Hoechst, Red: PNA, Green: EGFP).

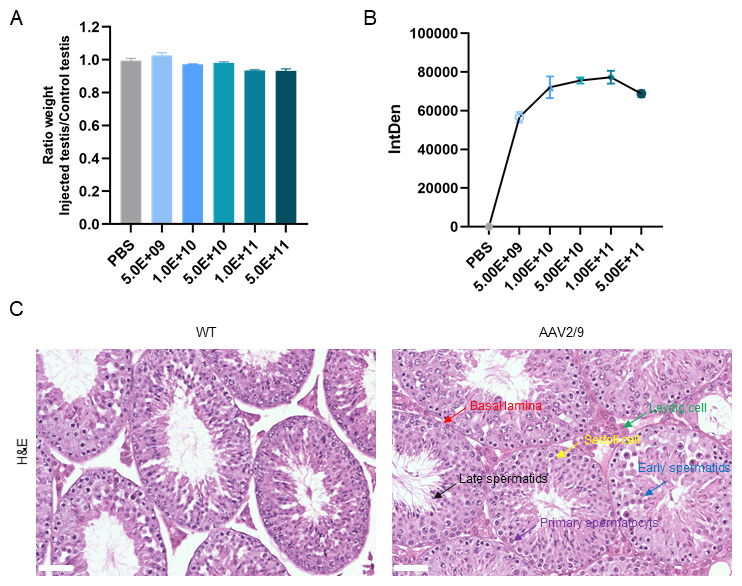

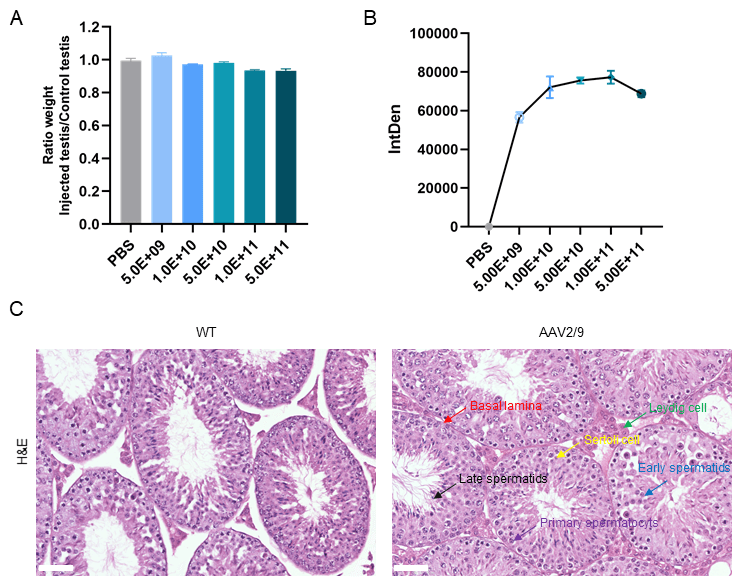

To determine whether varying concentrations of AAV2/9 administration impact

testicular development, we administered graded doses including PBS-only

(control), 5.0

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

AAV2/9 administration did not affect testicular development in

mice. (A) Testicular weight ratio (injected/non-injected) across different

AAV2/9 doses. No significant differences were observed. (B) Dose-dependent

increase in fluorescence intensity, plateauing at

This study provides a systematic comparison of the transfection efficiency of ten AAV-2 based hybrid serotypes in mouse testicular tissue. We report that AAV2/9 mediates superior transduction of germ cells within the seminiferous tubules, outperforming other serotypes, including the commonly used AAV2/8, by a substantial margin (~18-fold higher fluorescence intensity), without adversely affecting testicular development.

An important consideration in interpreting our findings is the age of the mice used. All injections were performed on 4-week-old (adolescent) mice, a development stage characterized by active and expanding spermatogenesis. The high transduction efficiency of AAV2/9 may be influenced by the specific physiological state of the adolescent testis, such as the maturation state of the blood-testis barrier (BTB) and the proliferative activity of spermatogonial populations. Consequently, the efficacy of our approach may vary in neonatal or aged models. Future studies comparing transduction efficiency across different age groups will be essential to determine the optimal window for therapeutic intervention.

The lack of adverse effects on testicular development following AAV2/9 administration suggests that this vector is unlikely to elicit significant immune or inflammatory responses within the testis. This favorable safety profile may be attributed to the non-lytic replication cycle of AAV, which preserves host cell integrity, and is further supported by the immune-privileged status of the testes. The non-lytic nature of AAV2/9 not only prevents cellular destruction but also minimizes potential inflammatory cascades that could disrupt the delicate testicular microenvironment.

The superior performance of the AAV2/9 chimera is likely underpinned by the intrinsic properties of the AAV9 capsid. AAV9 exhibits considerable promise due to its broad tissue penetrance, low immunogenicity, and stable transgene expression. Notably, AAV9 possesses the ability to traverse the BTB. A previous study has shown that AAV9-based vectors can effectively infect the testis [19]. The capacity to overcome the BTB, a formidable barrier restricting the entry of many therapeutics, is a significant advantage, enabling AAV2/9 to directly access intra-tubular cells and enhancing its therapeutic potential for conditions affecting spermatogenesis.

While one study has documented that particular AAV serotypes can influence the development of specific tissues or organs [20], our study also revealed pronounced serotype-dependent effects on testicular safety. While AAV2/9 showed an excellent safety profile, AAV2/2 and AAV2/5 exerted the most significant adverse effects on testicular development. This highlights the critical importance of serotype selection. The toxicity of AAV2/2 may be associated with its reported propensity to elicit stronger immune responses in certain tissues [21], potentially disrupting the testicular milieu. Similarly, AAV2/5 may interact with testicular cells components in a detrimental manner.

The high transduction efficiency and favorable safety profile position AAV2/9 as a highly promising vector for gene therapy targeting the testes. For conditions such as inherited testicular disorders or specific types of male infertility, AAV2/9-mediated gene delivery could offer a viable strategy for restoring function [22]. However, it is essential to conduct further research to optimize vector design, enhance target specificity, and improve the regulation of gene expression [23].

Our work, for instance, demonstrates its utility for delivering transgenes to

the germline, enabling strategies ranging from gene overexpression to

CRISPR/Cas9-based therapeutics. Compared to adenoviral vectors, AAV offers

prolonged transgene expression (

Looking forward, our findings provide a robust foundation for therapeutic development, with future work needing to focus on several interconnected fronts. The strategic use of the AAV2 backbone means the highly efficient AAV2/9 capsid can be readily equipped with germ cell-specific (e.g., Protamine 1 (Prm1)) or spermatogonial stem cell-specific (e.g., DEAD-Box Helicase 4 (Ddx4)) promoters to enhance target specificity and minimize off-target effects, while further capsid engineering could also refine its tropism. Concurrently, the superior tropism of AAV2/9 opens key mechanistic questions, directing future work toward identifying the primary receptor(s) utilized by AAV9 in the testis and profiling the local immune response to fully understand its superior performance. Addressing translational challenges and ensuring long-term efficacy are also critical, as the sustainability of transgene expression requires careful evaluation; our preliminary observations of a gradual decline in EGFP signal over time, consistent with vector dilution during active spermatogenesis, underscore the need to evaluate long-term safety, gene expression stability, and the impact of repeated administration. Furthermore, fundamental differences in spermatogenesis and testicular anatomy between mice and humans, coupled with the high prevalence of pre-existing immunity to AAV9 in the human population, pose significant translational hurdles that necessitate thorough investigation in more human-relevant models.

In conclusion, the findings of this study highlight the exceptional potential of AAV2/9 as a gene therapy vector for testicular applications. However, continued research is necessary to address the identified limitations and to fully realize its therapeutic potential for treating male infertility.

AAV2/9 achieves high-efficiency transduction in mouse testes, which is crucial for gene therapy targeting testicular diseases, especially in germ cells. Its unique capsid structure and receptor-binding properties enable it to effectively enter testicular germ cells. The testes’ immune-privileged environment further enhances AAV2/9 transduction. This makes AAV2/9 a promising gene delivery vector.

Our study also highlights AAV2/9’s safety. It doesn’t adversely affect testicular development, which is vital for its clinical application. This safety profile positions AAV2/9 as a potential platform for treating male reproductive disorders. For example, it can be used for CRISPR-based correction of spermatogenic mutations like azoospermia factor (AZF) microdeletions and for ectopic expression of fertility-associated genes in non-obstructive azoospermia. Additionally, AAV2/9 can be used to deliver gonad-protective agents during oncotherapy.

The experimental conditions may not fully reflect the complex in vivo environment. The specific testicular cell types transduced by AAV2/9 and their respective efficiencies require further delineation. The molecular mechanisms underlying AAV2/9’s high efficiency and lack of developmental impact, as well as potential germline toxicity, warrant further investigation. While our findings robustly establish AAV2/9 as a superior vector in the murine model, several translational limitations must be considered. Fundamental differences in spermatogenesis kinetics, testicular anatomy, and AAV receptor expression profiles between mice and humans could affect efficacy. Furthermore, the high prevalence of pre-existing neutralizing antibodies against AAV9 in humans poses a significant potential barrier not assessed in this study. Future validation in human-relevant models is essential.

In conclusion, our study definitively identifies AAV2/9 as a superior vector for gene delivery to murine testicular germ cells, combining high transduction efficiency with a favorable initial safety profile. These findings provide a robust preclinical foundation for developing gene therapies for male infertility. However, the translational path requires addressing several key limitations. Future work will focus on optimizing this platform through: (1) the use of germ cell-specific promoters (e.g., Prm1, Transition protein-1 (Tnp1)) to enhance target specificity and safety; (2) capsid engineering to further refine tropism towards specific spermatogenic cell populations (e.g., spermatogonial stem cells); and (3) investigating strategies to overcome pre-existing humoral immunity, which is a significant clinical hurdle for AAV therapies. By addressing these challenges, the promising potential of AAV2/9-mediated gene therapy for treating male reproductive disorders can be fully realized.

LNP, lipid nanoparticle; VLP, virus-like particle; AAV, adeno-associated virus; rAAV, recombinant adeno-associated virus; PFA, paraformaldehyde; BTB, blood-testis barrier; AZF, azoospermia factor.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are included in this published article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

BW and RL conceived and designed the experiments. BW and YG performed and experiments, acquired data and contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All animal experiment was carried out in compliance with guidelines by Research Ethics Committee at the tenth people’s hospital of Tongji University. Ethics approval ID: SHDSYY-2024-1984-9, Approval date: 2024-12-28.

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82271640) for its support. The authors gratefully acknowledge the institutional support provided by the School of Pharmacy, Fudan University, and the Medical Science Innovation Platform of Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital. We extend our sincere gratitude to Dr. Guangjin Pu from the Department of Vascular Surgery, Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital, Tongji University, for his invaluable assistance in mouse breeding and the construction of animal models. We are also deeply thankful to Researcher Lingbo Wang from the Institute of Metabolism and Integrative Biology, Fudan University, for his expert guidance on experimental details. Additionally, we extend our appreciation to all colleagues and collaborators who contributed to this research.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project approval number: 82271640).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work, we used DeepSeek to check spelling and grammar. And we take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.