1 Department of Urology, The Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University, 116023 Dalian, Liaoning, China

2 Department of General Surgery, The Affiliated Zhongshan Hospital of Dalian University, 116001 Dalian, Liaoning, China

Abstract

Cysteine and Glycine Rich Protein 1 (CSRP1) is a member of the cysteine-rich protein family, characterized by a unique double-zinc finger motif. It plays an important role in development and cellular differentiation. Aberrant expression of CSRP1 has been reported in several malignancies, including prostate cancer and acute myeloid leukemia. However, its function in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) remains unexplored. In this study, we investigated the role of CSRP1 in RCC for the first time.

CSRP1 and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression levels were determined using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The effects of CSRP1 overexpression on cellular proliferation, migration, and apoptosis were assessed in vitro through CCK-8, wound healing, and flow cytometry assays. To evaluate the role of CSRP1 in immunotherapy, Balb/c mice were treated with anti-PD-L1 antibody, and tumor growth was monitored.

In vitro, overexpression of CSRP1 significantly inhibited proliferation and migration of A498 cells while enhancing their sensitivity to sunitinib treatment. Mechanistically, CSRP1 overexpression downregulated PD-L1 expression in RCC cells. In BALB/c mice inoculated with Renca cells, CSRP1 overexpression led to reduced tumor growth and improved response to anti-PD-L1 therapy.

CSRP1 may play a role in regulating cell viability, migration, drug resistance, and possibly innate immunity in RCC. These findings suggest that CSRP1 could increase the efficacy of targeted drugs and immunotherapy in combination treatment strategies for RCC.

Keywords

- renal cell carcinoma

- cysteine and glycine-rich protein 1

- cell survival

- immunotherapy

- Lin-11 Is1-1 Mec-3 domain proteins

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) ranks as the second deadliest urological malignancy [1]. Clear cell RCC is the most prevalent histological subtype, comprising approximately 80–90% of all cases. The prognosis for RCC patients remains poor, with 5-year survival rates lingering between 5% and 12% [2]. As such, metastatic RCC management has been dominated by treatment with anti-angiogenic agents, such as the multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib [3]. While 70% of patients experience substantial benefit from sunitinib, a considerable proportion exhibit primary or acquired resistance, leading to eventual disease progression [3]. Thus, there is an urgent need to identify novel therapeutic targets and strategies to improve outcomes for patients with suboptimal response to existing therapies.

The cysteine- and glycine-rich protein (CSRP) family belongs to the Lin-11 Is1-1 Mec-3 (LIM) domain superfamily, which is evolutionarily conserved across vertebrates and invertebrates. The LIM domain mediates diverse cellular functions such as gene regulation and cytoskeletal organization [4]. Vertebrates express three CSRP members: CSRP1, CSRP2, and CSRP3/MLP [5, 6]. Recently, CSRP1 has garnered increasing attention for its potential role in cancer, particularly in urogenital malignancies. It has been implicated in adrenocortical carcinoma [7], prostate cancer [8, 9], bladder cancer [10], and kidney papillary cell carcinoma [11]. But most existing evidence relies on bioinformatic predictions, and systematic functional studies are lacking. The specific function of CSRP1 in RCC remains largely unexplored, representing a critical knowledge gap that warrants further investigation.

Therefore, we aimed to elucidate the functional role of CSRP1 in RCC through in vitro experiments and preclinical mouse tumor models.

A498 (#HTB-44) and Renca (#CRL-2947) cell lines were obtained from the

American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were

maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; #11995065; Invitrogen,

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; #10270106; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA),

100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (Penicillin-Streptomycin

Solution; Catalog #: 15140122; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham,

MA, USA). Cultures were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere

containing 5% CO2. For CSRP1 overexpression, 3

Successful overexpression of CSRP1 was verified by qRT-PCR. As directed by the manufacturer, RNA was extracted from cells using the RNA isoPlus® Reagent Kit (#9109; Takara, Shiga, Japan). RNA was converted to cDNA using the PrimeScript® RT Reagent Pack (#RR037A; Takara, Shiga, Japan). The SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ Unit (#RR420A; Takara, Shiga, Japan) was used to amplify the cDNA in accordance with the 7500 Continuous PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The following were the cycling conditions: GAPDH was used as the loading control for the target genes during forty cycles of 95 °C for 30 s and 60 °C for 34 s in the comparative Ct technique of data analysis. The initial sequences were listed in Table 1.

| Human GAPDH | Forward: 5′-GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA-3′ | |

| Human CSRP1 | Forward: 5′-TGCCGAAGAGGTTCAGTGC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-AGCAGGACTTGCAGTAAATCTC-3′ | |

| Human PD-L1 | Forward: 5′-CCTACTGGCATTTGCTGAACGCAT-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-CAATAGACAATTAGTGCAGCCAGGTC-3′ | |

| Mouse GAPDH | Forward: 5′-GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-TTTGCACTGGTACGTGTTGAT-3′ | |

| Mouse CSRP1 | Forward: 5′-AGCTTCCATAAATCCTGCTTCC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-ACTTCTTGCCGTAACATGACTTG-3′ | |

| Mouse PD-L1 | Forward: 5′-TGCTGCATAATCAGCTACGG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-GCTGGTCACATTGAGAAGCA-3′ |

After a 24-hour incubation for attachment, cells seeded in six-well plates (1

A wound healing assay was performed to evaluate the migratory ability of the

cell lines. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1

96 well plates were utilized to seed cells (2

The animal experiments in this study were conducted in strict compliance with

the ARRIVE guidelines, the UK. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and its

associated guidelines, and the EU Directive 2010/63/EU. All procedures were

reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Dalian Medical University

(Permit Number: AEE24139). Male BALB/c nude mice (4–6 weeks old, weighing 20

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Group differences were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Survival data were analyzed by Kaplan–Meier method, and differences between groups were compared using the log-rank test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

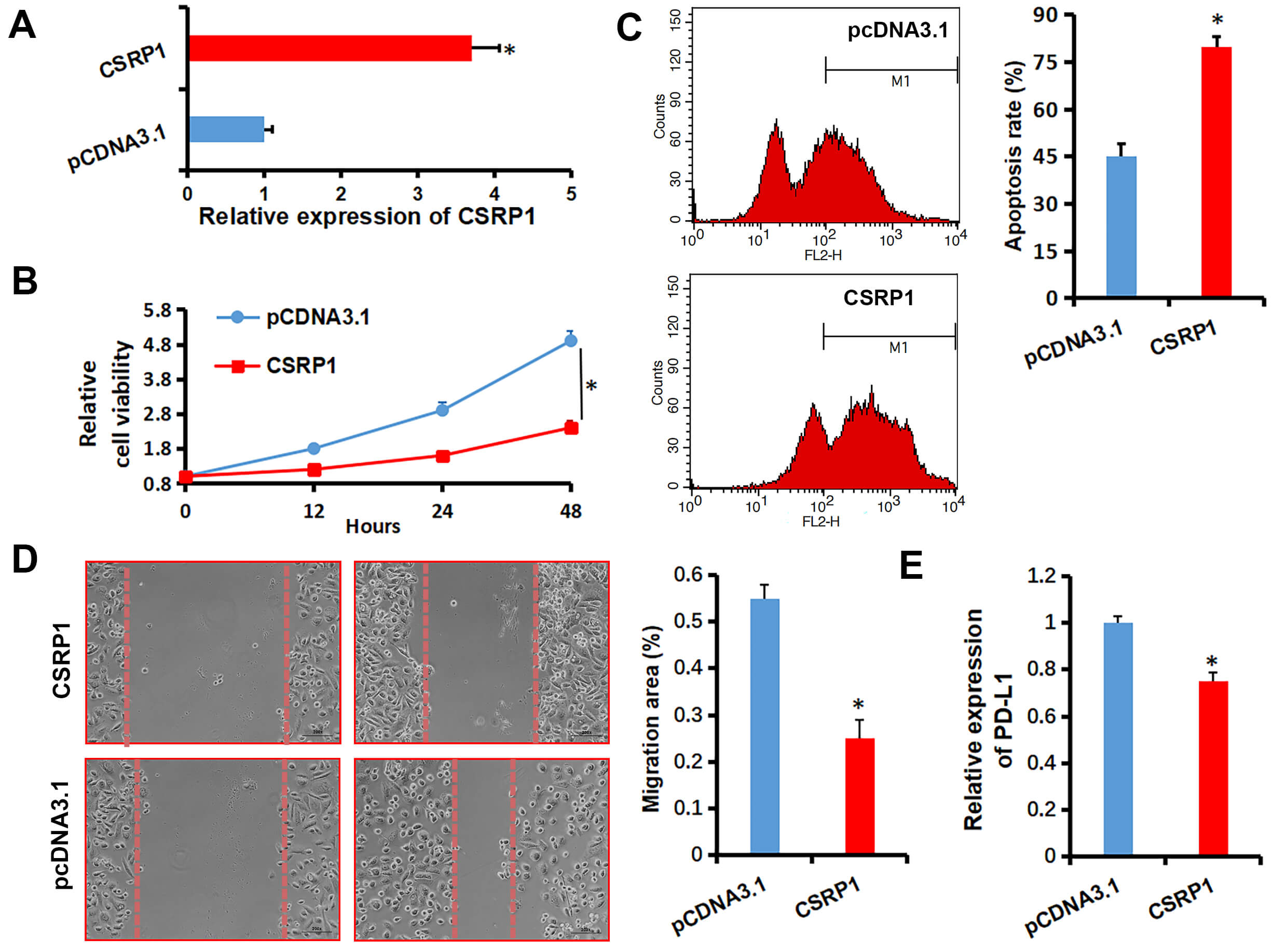

To investigate the biological role of CSRP1 in RCC, we established CSRP1-overexpressing A498 cells (A498-CSRP1; Fig. 1A). Elevated CSRP1 expression significantly suppressed the viability of A498 cells (Fig. 1B). Apoptosis analysis further revealed that CSRP1 overexpression markedly increased the sensitivity of A498 cells to sunitinib (10 µM) treatment (Fig. 1C). Additionally, CSRP1 upregulation considerably attenuated the migratory capacity of A498 cells (Fig. 1D). Given the critical role of PD-L1 in immunotherapy, we assessed its expression and found that CSRP1 overexpression significantly reduced PD-L1 mRNA levels in A498 cells (Fig. 1E). Collectively, these findings suggest that CSRP1 may function as a tumor suppressor in RCC.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Effects of CSRP1 overexpression on malignant phenotypes

of RCC cells. (A) qRT-PCR analysis confirming stable overexpression of

CSRP1 in A498 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1-CSRP1. (B) Cell

viability assessed by CCK-8 assay in CSRP1-overexpressing A498 cells.

(C) Apoptosis analysis by flow cytometry in A498 cells treated with 10 µM

sunitinib. (D) Migratory capacity evaluated by wound healing assay in

CSRP1-overexpressing A498 cells (Scale bar: 50 µm).

(E) qRT-PCR examination for PD-L1 expression in A498 cells. All data are

presented as mean

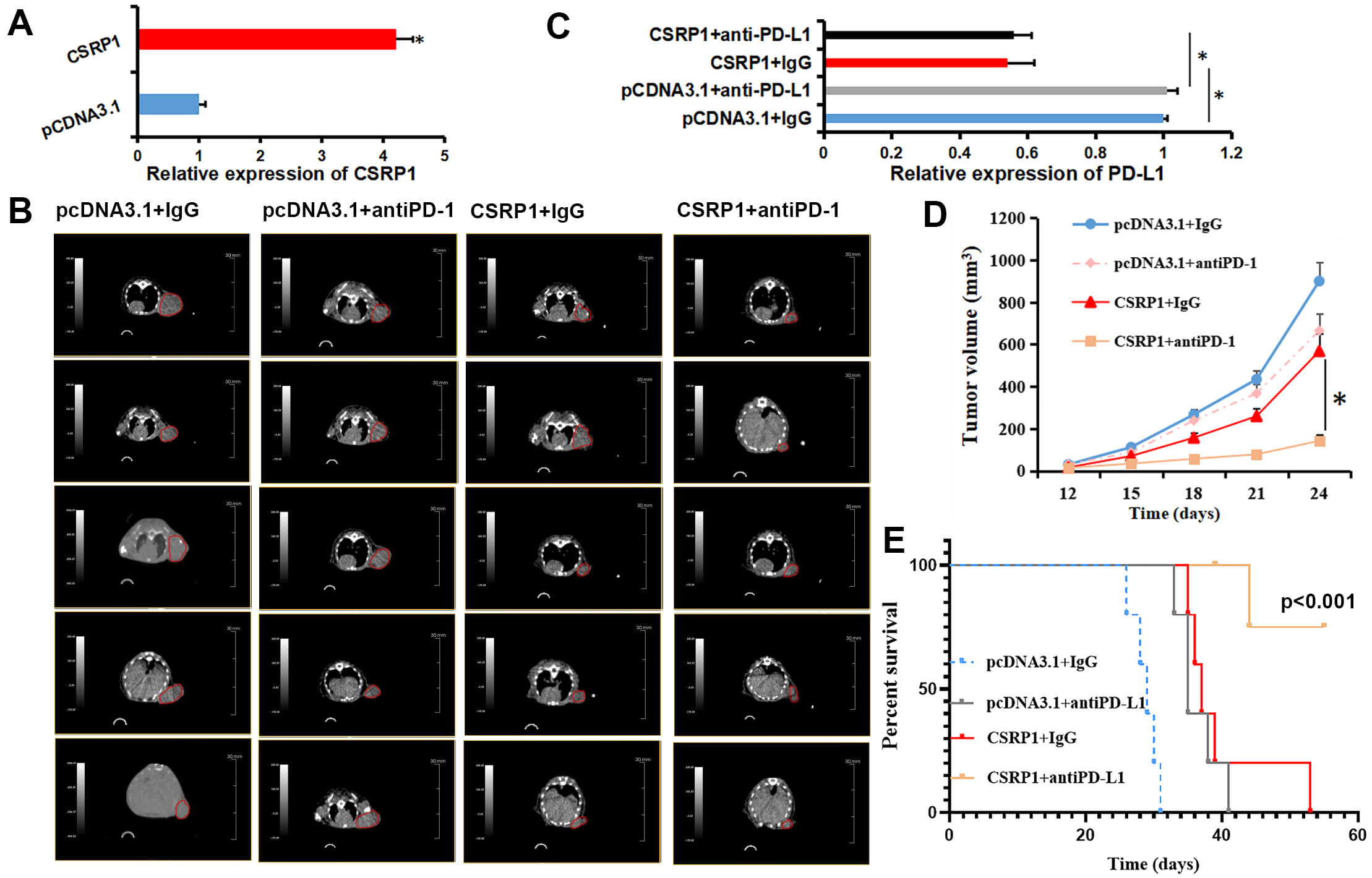

To further evaluate the impact of CSRP1 on tumor growth and response to immunotherapy, we employed Renca cells, a murine renal carcinoma cell line, with stable CSRP1 overexpression (Fig. 2A). Mice were divided into four treatment groups: pcDNA3.1 + IgG, pcDNA3.1 + anti-PD-L1, CSRP1 + IgG, and CSRP1 + anti-PD-L1 (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the in vitro findings, qRT-PCR analysis of the harvested tumor tissues revealed a significant decrease in PD-L1 mRNA levels in the CSRP1-overexpressing groups (Fig. 2C). Results revealed that CSRP1 overexpression significantly suppressed tumor growth and potentiated the anti-tumor effect of anti-PD-L1 treatment in vivo. Specifically, the CSRP1 + IgG group exhibited a markedly slower tumor growth rate compared to the pcDNA3.1 + IgG group. Similarly, tumor growth in the pcDNA3.1 + anti-PD-L1 group was reduced relative to the pcDNA3.1 + IgG controls. Most notably, the combination of CSRP1 overexpression and anti-PD-L1 treatment (CSRP1 + anti-PD-L1) led to the strongest inhibition of tumor growth (Fig. 2D). Consistent with these findings, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis indicated a significant prolongation of survival in mice overexpressing CSRP1 (Fig. 2E). 4 of 5 mice in the CSRP1 + anti-PD-L1 group survived until the end of the study, whereas all animals in the other groups reached the predefined survival endpoints. Together, these results demonstrate that CSRP1 not only inhibits tumor formation and growth in RCC but also enhances the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

CSRP1 overexpression inhibits tumor growth and

enhances anti-PD-L1 therapy response in a murine RCC model. (A) qRT-PCR

validation of stable CSRP1 overexpression in Renca cells.

(B) Representative CT images of tumors in the four treatment groups (n = 5). The red circles denote the subcutaneous tumors that were monitored for the study. (C)

qRT-PCR examination for PD-L1 expression in the four treatment groups.

(D) Tumor growth curves across experimental groups. (E) Kaplan–Meier survival

analysis based on endpoint-free survival (log-rank test, p

The present study underscores the tumor-suppressive function of CSRP1 in RCC. Cysteine-rich proteins (CRPs), a key subclass within the LIM domain protein family, play vital roles in diverse physiological and pathological contexts. Among them, CSRP1 has emerged as a potential prognostic biomarker in multiple cancers. Reduced expression of CSRP1 has been linked to dysregulated cell growth and differentiation, thereby facilitating tumorigenesis [12]. For instance, Demirkol Canli [13] reported that CSRP1 expression correlates with a mesenchymal stroma-rich molecular subtype and poor prognosis in colon cancer. Similarly, several studies have implicated CSRP1 in the progression of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Han et al. [14] demonstrated that METTL3 stabilizes CSRP1 mRNA through m6A modification, thereby delaying its degradation. Qin et al. [15] associated high CSRP1 expression with activation of pathways such as p53, complement, inflammatory response, NOTCH, IL6-JAK-STAT3, and IL2-STAT5 signaling, suggesting its involvement in AML pathogenesis.

Conversely, Lin et al. [16] reported that CSRP1 enhances cisplatin-induced apoptosis and chemosensitivity via mitochondrial pathways in neuroblastoma. In gastric cancer, CSRP1 was identified as a potential target of Celecoxib [17]. Our previous work revealed that low CSRP1 expression promotes the progression of hormone-sensitive prostate cancer, a finding supported by clinical cohort analysis [18]. CSRP1 has also been identified among an eight-gene signature predictive of overall survival in kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma [11]. However, most existing evidence remains bioinformatic, with limited functional validation. To address this gap, we performed systematic in vitro functional assays—including proliferation, apoptosis, and migration experiments—which collectively demonstrated that elevated CSRP1 expression suppresses proliferation, promotes apoptosis, and impedes migration in RCC cells.

Notably, multiple studies have associated high CSRP1 expression with increased immune infiltration, suggesting a role in modulating antitumor immunity. For example, Wang et al. [19] revealed that astrocytic PD-L1/PD-1 signaling regulates maturation and morphogenesis via the MEK/ERK pathway through CSRP1. Qin et al. [15], using the GeneMANIA database, identified ILK, MYL9, MYLK, and REL as key CSRP1-interacting proteins. Based on literature review, we hypothesize that CSRP1 may participate in inflammatory regulation. For instance, ILK upregulation promotes ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression, potentially amplifying inflammatory responses [20]. MYL9 facilitates the recruitment of activated T cells to inflamed or tumor tissues [21], while MYLK is implicated in immune and inflammatory pathways [22]. REL can activate NOTCH signaling via Jagged1, influencing B-cell function [23]. To corroborate these findings under more physiologically relevant conditions, we employed syngeneic mouse models, which confirmed that CSRP1 overexpression restrains tumor growth and synergizes with anti-PD-L1 therapy. Crucially, our study provides a plausible mechanism for this synergy: the downregulation of PD-L1 by CSRP1. We demonstrated that CSRP1 overexpression reduces PD-L1 levels in both cultured RCC cells and murine tumor tissues. This reduction in the primary ligand for PD-1 likely leads to a diminished PD-1/PD-L1-mediated immunosuppressive signal, thereby “priming” the tumor microenvironment for a more effective response when the pathway is therapeutically blocked by anti-PD-L1 antibodies.

The clinical gain anticipated from our findings is twofold. First, CSRP1 expression could serve as a novel predictive biomarker to stratify RCC patients for therapy. Our data indicate that tumors with high CSRP1 levels are not only inherently less aggressive but also more susceptible to anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy. This suggests that assessing CSRP1 status in patient tumors could help identify individuals most likely to derive significant benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors, thereby personalizing treatment approaches and avoiding ineffective therapies in non-responders. Second, and more prospectively, our work nominates CSRP1 as a compelling therapeutic target itself. The development of strategies to reactivate or mimic CSRP1 function could represent a new avenue for RCC treatment. Such an approach would aim to restore this natural tumor-suppressive mechanism, simultaneously impairing cancer cell viability and sensitizing the tumor microenvironment to immunotherapy, creating a synergistic anti-tumor effect.

Despite these significant observations, our study has limitations. Although we demonstrated that CSRP1 overexpression reduces cell viability and enhances immunotherapy response, the precise molecular mechanisms remain unexplored. Further investigations are warranted to elucidate the signaling pathways and immune-modulatory mechanisms through which CSRP1 exerts its antitumor effects in RCC.

CSRP1 may play a critical role in regulating cell viability, migration, drug resistance, and innate immune responses in RCC. Targeting CSRP1 could therefore represent a promising therapeutic strategy for RCC treatment. However, further high-quality clinical evidence is needed to validate its translational potential.

The data analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

YH: Methodology, Software, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft. Supervision, Validation. YK: Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft. Supervision, Validation. DZ: Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Supervision, Validation. YY: Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Validation. BY: Methodology, Software, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The animal experiments in this study were conducted in strict compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines, the UK. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and its associated guidelines, and the EU Directive 2010/63/EU. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Dalian Medical University (Permit Number: AEE24139).

Not applicable.

This study was supported by the “1+X” Research Project of the Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University (CYQH2024016) to YH; the Dalian Medical Science Research Program Project (2312015) to YH; Dalian Municipal Guidance Plan Initiative for the Life and Health Sector (2024ZDJH01PT113) to YH; Liaoning Provincial Department of Education Key Research Project (JYTZD2023020) to DZ; Liaoning Provincial Department of Education Basic Scientific Research Project (LJ212510161015) to BY.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.