1 Department of Cardiology, The People’s Hospital of Chizhou, 247100 Chizhou, Anhui, China

2 Research and Development Center, Center of Human Microecology Engineering and Technology of Guangdong Province, 510700 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Heart failure (HF) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Although dapagliflozin, a selective sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, has demonstrated significant cardiovascular benefits in large clinical trials, the underlying mechanisms beyond glucose lowering remain incompletely understood. Increasing evidence suggests that gut microbiota and its metabolites may contribute to HF progression through gut–heart axis interactions.

In this study, a total of 135 individuals with HF were recruited, comprising 84 patients treated with dapagliflozin (Y group) and 51 receiving conventional therapy (N group). Gut microbial communities were characterized through 16S rRNA gene sequencing to evaluate compositional structure, diversity metrics, and taxa differences between groups. Untargeted metabolomic profiling of plasma samples was conducted to identify significantly altered metabolites and enriched metabolic pathways. Furthermore, the interrelationships between gut bacterial taxa and circulating metabolites were systematically explored to delineate potential microbiome–metabolome interactions.

Dapagliflozin treatment significantly altered gut microbial composition (p < 0.05, permutational multivariate analysis of variance [PERMANOVA]), characterized by increased Prevotella, Akkermansia, Collinsella, and Fusobacterium, and reduced Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, Subdoligranulum, and Bifidobacterium in the dapagliflozin group, whereas control-enriched taxa included Lachnoclostridium and the Ruminococcus gauvreauii group. Fourteen plasma metabolites were differentially abundant between groups, including higher levels of O-phospho-L-threonine and epiandrosterone in the dapagliflozin group, while salicyluric acid and L- (+)-rhamnose were enriched in the control group. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis indicated alterations in amino acid and one-carbon metabolism, as well as carbohydrate and steroid-related pathways. Correlation analysis revealed that Collinsella was positively associated with fludarabine phosphate (p < 0.05), whereas Akkermansia and Paraprevotella showed negative correlations with maslinic acid and phospho-L-valine, respectively (p < 0.01 to p < 0.001).

Dapagliflozin modulates gut microbiota composition and circulating metabolic signatures in HF patients, supporting a potential gut–heart axis mechanism contributing to its cardioprotective effects.

Keywords

- heart failure

- dapagliflozin

- gastrointestinal microbiome

- metabolomics

- gut–heart axis

Heart failure (HF) is a multifactorial syndrome in which structural or functional defects of the heart impair its pumping capacity and increase intracardiac pressures, triggering progressive hemodynamic alterations and clinical manifestations [1, 2]. With the aging population and the increasing burden of cardiovascular diseases, the global incidence of HF continues to rise, making it a major public health concern. The clinical manifestations of HF are diverse, ranging from asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction to severe congestive symptoms such as dyspnea, fatigue, and fluid retention [3, 4]. HF not only severely impacts patients’ quality of life but is also associated with high mortality, high readmission rates, and a substantial economic healthcare burden.

HF is associated with extremely high morbidity and mortality. One study reported that the 5-year mortality rate after an HF diagnosis can reach 50%, comparable to many malignant tumors [5]. HF patients are frequently hospitalized, with approximately 50% readmitted within six months after discharge, creating a significant healthcare burden [6]. HF also leads to multi-system complications, including worsening renal function (cardiorenal syndrome), liver abnormalities, and cognitive dysfunction [7]. Notably, even subclinical HF (elevated B-type Natriuretic Peptide [BNP] without symptoms) is associated with an increased risk of death, comparable to that of overt HF [5]. Patients with heart failure frequently experience poor quality of life, and approximately 30–40% present with depressive or anxiety disorders, further compounding the disease burden [8].

Heart failure is identified through an integrated clinical and biochemical assessment, with BNP and its N-terminal fragment (NT-proBNP) serving as reliable biomarkers to differentiate cardiac from non-cardiac causes of dyspnea [9]. Echocardiography is the cornerstone for evaluating cardiac structure and function. Emerging techniques such as three-dimensional echocardiography and strain imaging have improved the detection rate of early cardiac dysfunction [10]. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) offers unique advantages in assessing myocardial fibrosis, inflammation, and specific cardiomyopathies [10, 11]. Additionally, artificial intelligence-assisted electrocardiogram (ECG) analysis is beginning to be used for predicting HF risk and treatment response [12].

The gut microbiota has recently emerged as a key regulator in cardiovascular health and disease. As an interface between host and environment, the gut microbiome participates in metabolic homeostasis, immune regulation, and inflammatory responses [13, 14]. Studies show that the structure and function of the gut microbiota are influenced by multiple factors, including host genetics, diet, environment, and developmental stage, while also exhibiting significant stability and plasticity [15, 16]. Particularly during species adaptation to environmental changes (e.g., invasion pressure, high-altitude environments), the vertical transmission and functional synergy of specific core microbiota become key mechanisms [17].

In recent years, the association between the gut microbiota and cardiovascular diseases, particularly HF has become a research hotspot. HF patients often exhibit gut microbiota dysbiosis, characterized by a reduction in beneficial bacteria and an overgrowth of potentially harmful bacteria [18]. This dysbiosis exacerbates HF progression through multiple mechanisms, including abnormalities in metabolites [e.g., trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)], bacterial translocation due to impaired intestinal barrier integrity, and systemic inflammation and immune activation [19]. Furthermore, the gut microbiota is closely linked to HF risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity [20]. Microbiota often exert key effects through metabolites. For instance, choline and carnitine are metabolized by gut microbes into trimethylamine (TMA), which is subsequently oxidized in the liver to TMAO. TMAO can promote atherosclerosis, platelet activation, and myocardial fibrosis, thereby worsening HF [19]. High TMAO levels are significantly associated with poor prognosis in HF patients [21]. SCFAs like butyrate and propionate, produced by microbial fermentation of dietary fiber, possess anti-inflammatory properties and help maintain intestinal barrier function. HF patients show a reduction in SCFA-producing bacteria (e.g., Roseburia, Faecalibacterium), potentially leading to immune dysregulation and myocardial inflammation [19, 22]. The microbiota also regulates bile acid metabolism. Secondary bile acids modulate cardiac energy metabolism and inflammation through the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and G protein-coupled receptor (TGR5), and their imbalance is associated with HF [23].

Dapagliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, was initially developed for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). However, recent studies have demonstrated its significant clinical benefits in HF treatment, regardless of diabetes status [24, 25]. Dapagliflozin (DAPA) has shown notable cardiovascular protective effects in several large randomized controlled trials. In the DAPA-HF trial, dapagliflozin significantly reduced the risk of the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or worsening heart failure (hazard ratio [HR] 0.74) in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [26, 27]. The DELIVER trial further confirmed that dapagliflozin is also effective in patients with heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction (HFmrEF/HFpEF), reducing the risk of the primary endpoint by 18% (HR 0.82) [28]. Moreover, the efficacy of dapagliflozin was consistent across patients of different ages, ethnicities, and baseline renal function statuses [29]. Notably, the reduction in the risk of hospitalization for heart failure with dapagliflozin was particularly significant, a finding validated in both HFrEF and HFpEF patients [28].

Recent research suggests that the benefits of dapagliflozin may extend beyond its glucose-lowering effects and be closely linked to the modulation of the gut microbiota [30]. The gut microbiota interacts with host organs through metabolites, forming bidirectional communication networks such as the “gut-kidney axis” and “gut-heart axis”, which influence disease progression [31]. However, studies investigating the impact of dapagliflozin on HF through the gut microbiota are still lacking.

In summary, numerous clinical studies have confirmed the significant efficacy of dapagliflozin in improving HF outcomes, but its underlying mechanisms have not been fully elucidated. Traditional views have primarily focused on its diuretic, glucose-lowering, and cardiac load-reducing effects. Systematic research on whether it exerts cardioprotective effects by modulating the gut microbiota and host metabolic networks is still lacking. Given the critical role of the gut-heart axis in the pathogenesis and progression of HF, this study integrates 16S rRNA sequencing and untargeted metabolomics technologies to comprehensively analyze the effects of dapagliflozin on the gut microbiota composition, plasma metabolic profile, and microbiota-metabolite interaction patterns in HF patients. The aim is to reveal the potential molecular mechanisms beyond its glucose-lowering effects and provide new theoretical foundations and intervention strategies for the precise treatment of heart failure.

A total of 135 patients with clinically diagnosed HF were enrolled at The People’s Hospital of Chizhou (approved No. 2023-KY-18). This investigation was conducted as a retrospective study, in which clinical characteristics, fecal microbiota, and plasma metabolomic data were obtained once for each participant at the time of enrollment. Patients were divided into two groups: the dapagliflozin group (Y group, n = 84), who received dapagliflozin in addition to standard HF therapy, and the control group (N group, n = 51), who received standard therapy alone. Baseline demographic and clinical data were collected, including age, sex, comorbidities, laboratory parameters, and cardiac function.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) use of antibiotics or probiotics within the previous 4 weeks; (2) acute infection; (3) autoimmune disease; (4) malignancy; (5) gastrointestinal disorders; and (6) other conditions that could interfere with gut microbiota analysis. All participants provided written informed consent. This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of The People’s Hospital of Chizhou.

Fasting venous blood samples were collected in the morning. Routine laboratory tests included hematology, liver and kidney function, lipid profiles, coagulation parameters, thyroid function, and inflammatory biomarkers [C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT)]. All analyses were performed using standard automated clinical platforms.

Fresh stool samples were collected from all participants using sterile collection tubes under standardized conditions. Each sample was immediately sealed, placed on ice, and transferred to the laboratory within 2 hours of collection. Upon arrival, fecal specimens were aliquoted (200 mg per tube) and stored at –80 °C until further processing to preserve microbial DNA integrity.

The V3–V4 hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified

using barcoded primers and Pfu high-fidelity DNA polymerase. Negative controls

were included to monitor contamination. PCR products were purified using magnetic

beads (N411, Vazyme, Nanjing, China), quantified with the

Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (P7589, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), and

used for library preparation with the TruSeq Nano DNA LT Library Prep Kit

(NP-101-1001, Illumina, San Diego, USA). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000

platform with paired-end 2

Raw reads were processed using fastp (v0.20.0, HaploX, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) for adapter trimming,

quality filtering (Q

Alpha diversity was assessed by Chao1, Shannon, Simpson, and Pielou indices.

Beta diversity was evaluated using Jaccard, Bray–Curtis, weighted UniFrac, and

unweighted UniFrac distances, and visualized by principal coordinate analysis

(PCoA), non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS), and principal component

analysis (PCA). Group differences were tested using permutational multivariate

analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) or analysis of similarities (ANOSIM). Functional

prediction was conducted with Tax4Fun2 (https://tax4fun.gobics.de/, v1.1.5), and group differences were

assessed using Kruskal–Wallis tests with Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

Differential taxa were identified using linear discriminant analysis effect size

(LEfSe) with a threshold of linear discriminant analysis (LDA)

Plasma metabolites were extracted by protein precipitation with cold methanol,

centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min, dried under nitrogen, and reconstituted in

50% methanol. Quality control (QC) samples, prepared by pooling equal aliquots

of all study samples, were inserted regularly throughout the analytical sequence

to evaluate instrument stability. Peaks with a detection rate

Raw Liquid Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (LC–MS) data were imported into the Compound Discoverer 3.2 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) for peak extraction, retention time alignment, and normalization. Metabolite annotation was performed by matching accurate mass, isotope ratio, and MS/MS fragmentation patterns against multiple publicly available databases, including the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) (https://hmdb.ca), MassBank, and Metabolite Mass Spectral Database (METLIN) (https://metlin.scripps.edu/auth-login.html). The use of multiple databases enhanced both coverage and reliability of identification. HMDB provides comprehensive reference spectra for endogenous metabolites and detailed biological pathway information, offering high confidence for compounds of physiological relevance. MassBank contains high-quality, manually curated spectra and ensures accurate structural matching for small biomolecules. METLIN, the largest MS/MS spectral repository, includes a broad range of xenobiotics and derivatives, making it particularly useful for exploratory or untargeted metabolomic profiling.

Each database has inherent advantages and limitations: HMDB and MassBank yield

higher identification specificity for endogenous metabolites but may have limited

compound coverage, while METLIN achieves broader coverage but contains partially

redundant entries and fewer biologically contextual annotations. To maximize

confidence, only features with mass tolerance

Pathway enrichment and functional categorization of identified metabolites were subsequently performed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database, allowing integration of metabolomic alterations with key biological processes.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk,

USA), GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA), and R (version

4.2.2). Continuous variables were first tested for normality using the

Shapiro–Wilk test. Variables conforming to a normal distribution are presented

as mean

The Kruskal–Wallis test was employed to compare

For global metabolomic pattern recognition, partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was applied to identify metabolites that contribute most strongly to the separation between groups. This supervised multivariate method maximizes covariance between predictors (metabolite features) and group labels, making it well suited for high-dimensional datasets with multicollinearity. Model reliability was evaluated using R2 and Q2 statistics and cross-validation.

Differential microbial taxa were determined using the LEfSe method, which

integrates non-parametric statistical testing with LDA effect size estimation to

highlight taxa that are both statistically significant and biologically

meaningful. Differential metabolites were identified with variable importance in

projection (VIP)

Correlations between gut microbiota and metabolites were assessed by Spearman’s rank correlation, a non-parametric approach that does not assume linearity and remains appropriate for compositional microbiome data. Network and heatmap visualizations were constructed using Cytoscape and the “pheatmap” R package to illustrate key microbe–metabolite associations.

These analytical choices collectively ensured robust handling of non-normally distributed, high-dimensional, and interdependent omics datasets, while minimizing model bias and overfitting.

A total of 135 patients with heart failure were enrolled and categorized by

dapagliflozin exposure: the Dapagliflozin group (Y group, n = 84), receiving

dapagliflozin on top of standard therapy, and the control group (N group, n =

51), receiving standard therapy alone (shown in Table 1). Baseline demographics

(sex and age) did not differ between groups. Several laboratory indices were

higher in the Dapagliflozin group, including neutrophil percentage (p =

0.018), platelet count (p = 0.043), cholesterol (p = 0.021),

low-density lipoprotein (p = 0.008), and apolipoprotein B (p =

0.010). No between-group differences were observed for CRP or PCT, routine blood

counts, hepatic/renal function, coagulation markers, thyroid function, or urine

protein positivity. Most continuous variables were non-normally distributed

according to the Shapiro–Wilk test and are therefore presented as median (IQR).

Normally distributed variables are expressed as mean

| Variable | Control (N = 51) | Dapagliflozin (Y = 84) | p value |

| Sex (male/female) | 30/21 | 51/33 | – |

| Age (years) | 76 (70–83) | 74 (66–81) | 0.061 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.85 (0.70–3.95) | 1.60 (0.65–3.20) | 0.88 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 0.05 (0.03–0.15) | 0.04 (0.02–0.10) | 0.79 |

| Red blood cells ( |

3.90 (3.55–4.35) | 4.10 (3.80–4.45) | 0.08 |

| White blood cells ( |

5.20 (4.30–6.30) | 5.80 (4.90–7.00) | 0.09 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 66.0 (59.5–73.5) | 70.0 (62.0–78.5) | 0.018 * |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 116 (103–129) | 124 (110–138) | 0.19 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 37 |

38 |

0.24 |

| Platelets ( |

149 (120–178) | 168 (137–202) | 0.043 * |

| ALT (U/L) | 19 (12–34) | 18 (11–31) | 0.25 |

| AST (U/L) | 22 (15–33) | 21 (14–29) | 0.27 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/L) | 12.1 (9.4–16.8) | 11.3 (8.8–15.7) | 0.31 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 7.4 (5.9–8.8) | 7.3 (5.6–8.6) | 0.34 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 97 (70–126) | 100 (78–122) | 0.57 |

| Uric acid (µmol/L) | 425 (312–530) | 416 (308–518) | 0.95 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 5.0 |

5.0 |

0.93 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.4 (2.9–3.9) | 3.7 (3.1–4.2) | 0.021 * |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 0.80 (0.50–1.10) | 0.97 (0.64–1.19) | 0.18 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.19 |

1.15 |

0.90 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.6 (1.1–2.0) | 2.0 (1.5–2.3) | 0.008 * |

| Apolipoprotein A1 (g/L) | 1.24 |

1.22 |

0.87 |

| Apolipoprotein B (g/L) | 0.61 (0.49–0.72) | 0.68 (0.52–0.81) | 0.010 * |

| Total bile acid (µmol/L) | 4.4 (2.2–6.02) | 4.15 (2.18–8.15) | 0.72 |

| 33 (18–62) | 29 (17–55) | 0.80 | |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.78 |

2.82 |

0.47 |

| PT (s) | 12.3 |

12.5 |

0.73 |

| APTT (s) | 28.7 |

28.2 |

0.52 |

| Thrombin Time TT (s) | 18.3 |

18.2 |

0.35 |

| INR | 1.06 |

1.08 |

0.53 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 0.45 (0.20–0.85) | 0.50 (0.25–0.91) | 0.78 |

| TSH (mU/L) | 1.79 (1.03–2.92) | 2.03 (1.18–3.60) | 0.46 |

| FT3 (pmol/L) | 2.3 |

2.4 |

0.64 |

| FT4 (pmol/L) | 1.03 |

1.07 |

0.30 |

| Urine protein (neg/pos) | 36/12 (a) | 62/16 (a) | 0.56 |

*Significant difference between groups (p

CRP, C-reactive protein; PCT, procalcitonin; ALT, Alanine Aminotransferase; AST,

Aspartate Aminotransferase; HDL-C, High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; LDL-C,

Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol;

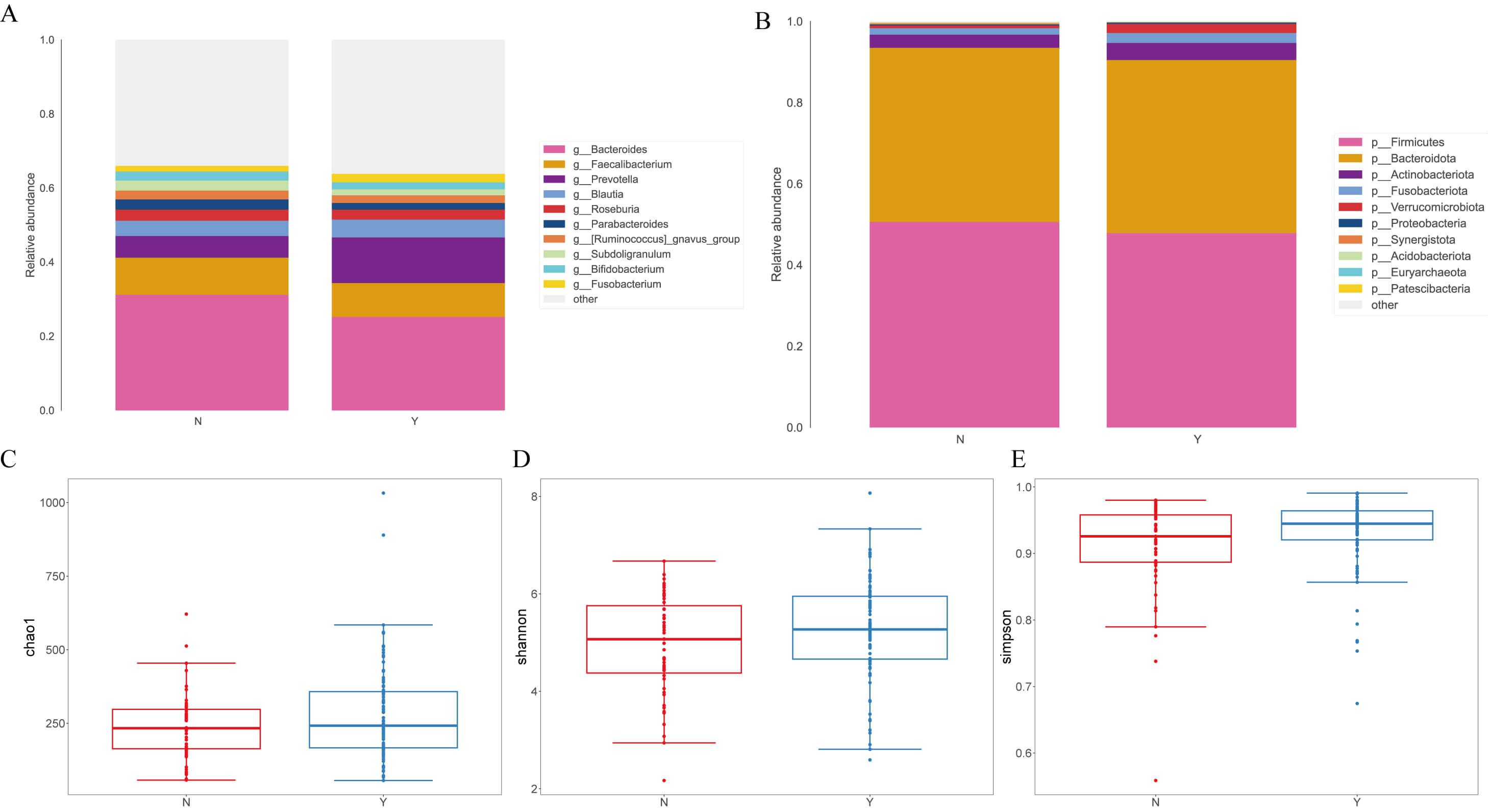

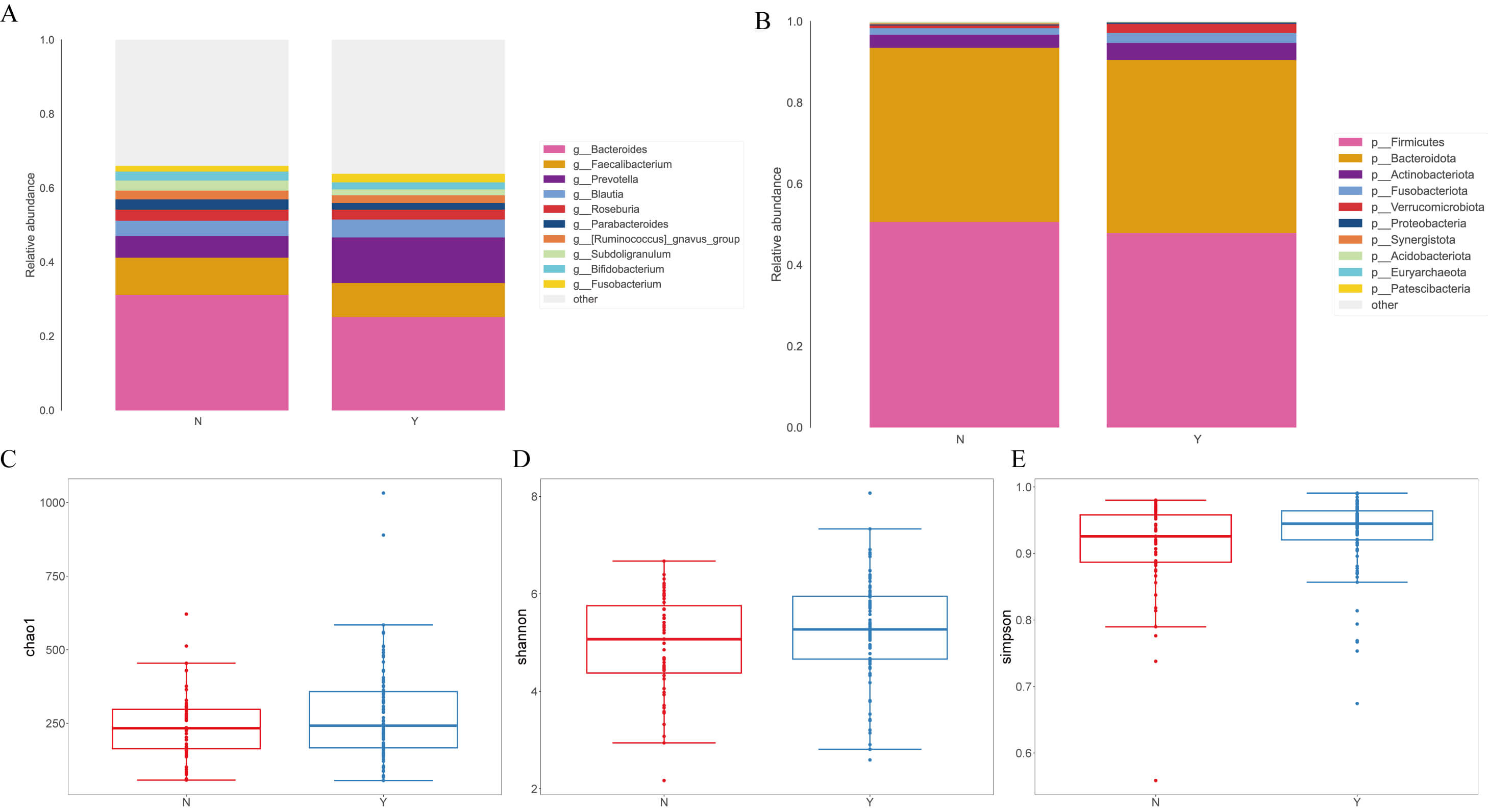

At the genus level (Fig. 1A), g__Prevotella was increased in the Dapagliflozin group (12.30% vs. 5.84% in Controls), whereas g__Bacteroides was reduced (25.21% vs. 31.20%). Decreases were also noted for g__Parabacteroides (1.79% vs. 2.78%), g__Subdoligranulum (1.63% vs. 2.70%), and g__Bifidobacterium (1.87% vs. 2.43%), while g__Fusobacterium increased (2.32% vs. 1.53%). At the phylum level (Fig. 1B), p__Firmicutes and p__Bacteroidota dominated in both groups. The Dapagliflozin group showed a modest decrease in p__Firmicutes (47.90% vs. 50.62%) with a similar proportion of p__Bacteroidota (42.59% vs. 42.90%). Minor phyla shifted, with higher p__Verrucomicrobiota (2.25% vs. 0.64%), p__Actinobacteriota (4.22% vs. 3.24%), and p__Fusobacteriota (2.45% vs. 1.60%) in the Dapagliflozin group.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of fecal microbial species classification and alpha and

beta diversity indices in heart failure (HF) patients treated with

dapagliflozin. (A) Relative abundance of fecal microbiota at the genus level in

the two groups. (B) Distribution of microbial composition at the phylum level.

(C) Comparison of

Alpha-diversity did not differ between groups across Chao1 (Mann–Whitney U = 2347.5, p = 0.291; t = 1.696, p = 0.092) (Fig. 1C), Shannon (U = 2443.0, p = 0.135; t = 1.659, p = 0.100) (Fig. 1D), and Simpson (U = 2528.0, p = 0.060; t = 1.653, p = 0.102) indices (Fig. 1E).

For beta-diversity, at the phylum level the two groups were nearly indistinguishable; at the genus level, Bray–Curtis remained similar, whereas the Jaccard metric indicated greater within-group dispersion in Controls, suggesting more heterogeneity in low-abundance or presence/absence genera. Fig. 1 shows the overall taxonomic profiles and diversity metrics.

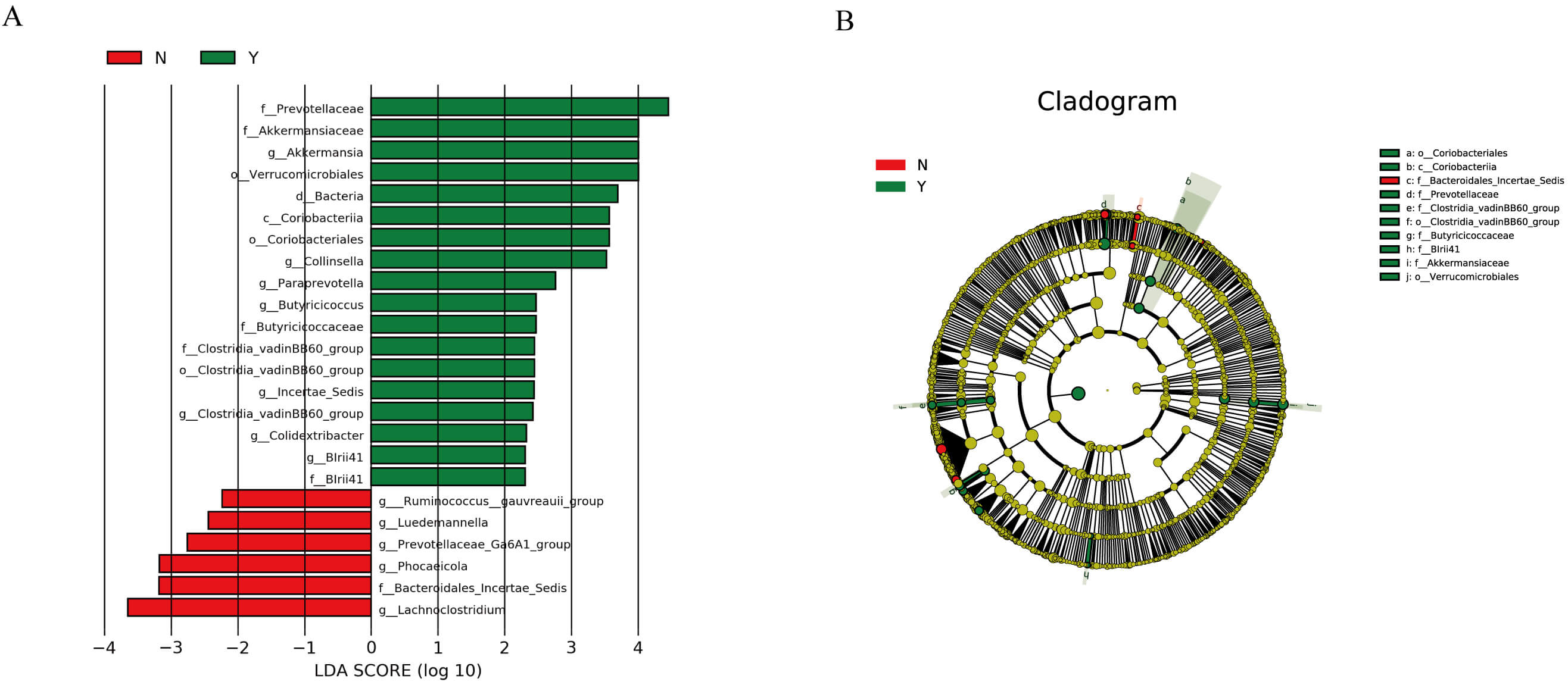

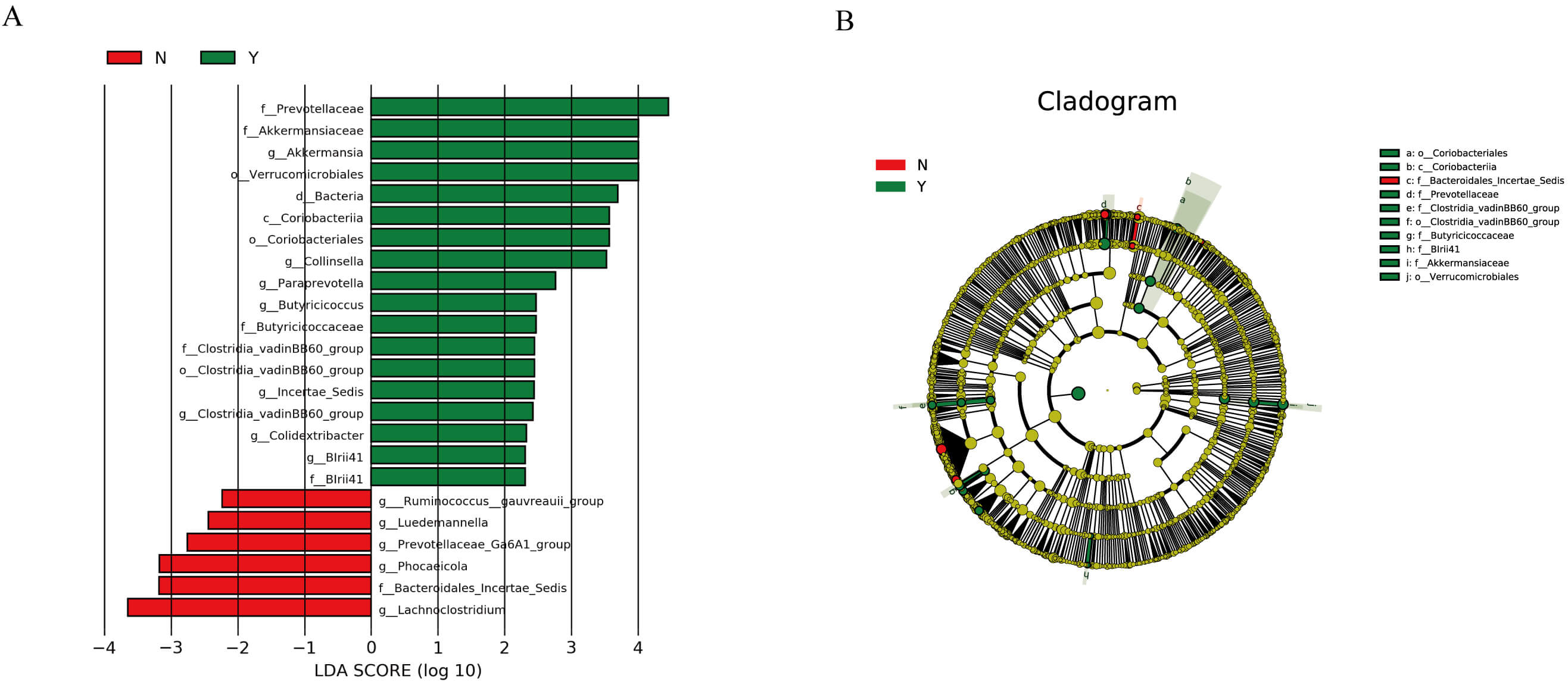

LEfSe identified taxa differentiating the two groups (LDA

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

LEfSe analysis results of the effect of dapagliflozin on the gut

microbiota structure in HF patients. (A) Linear discriminant analysis (LDA)

scores showing taxa that significantly discriminate between the two groups (LDA

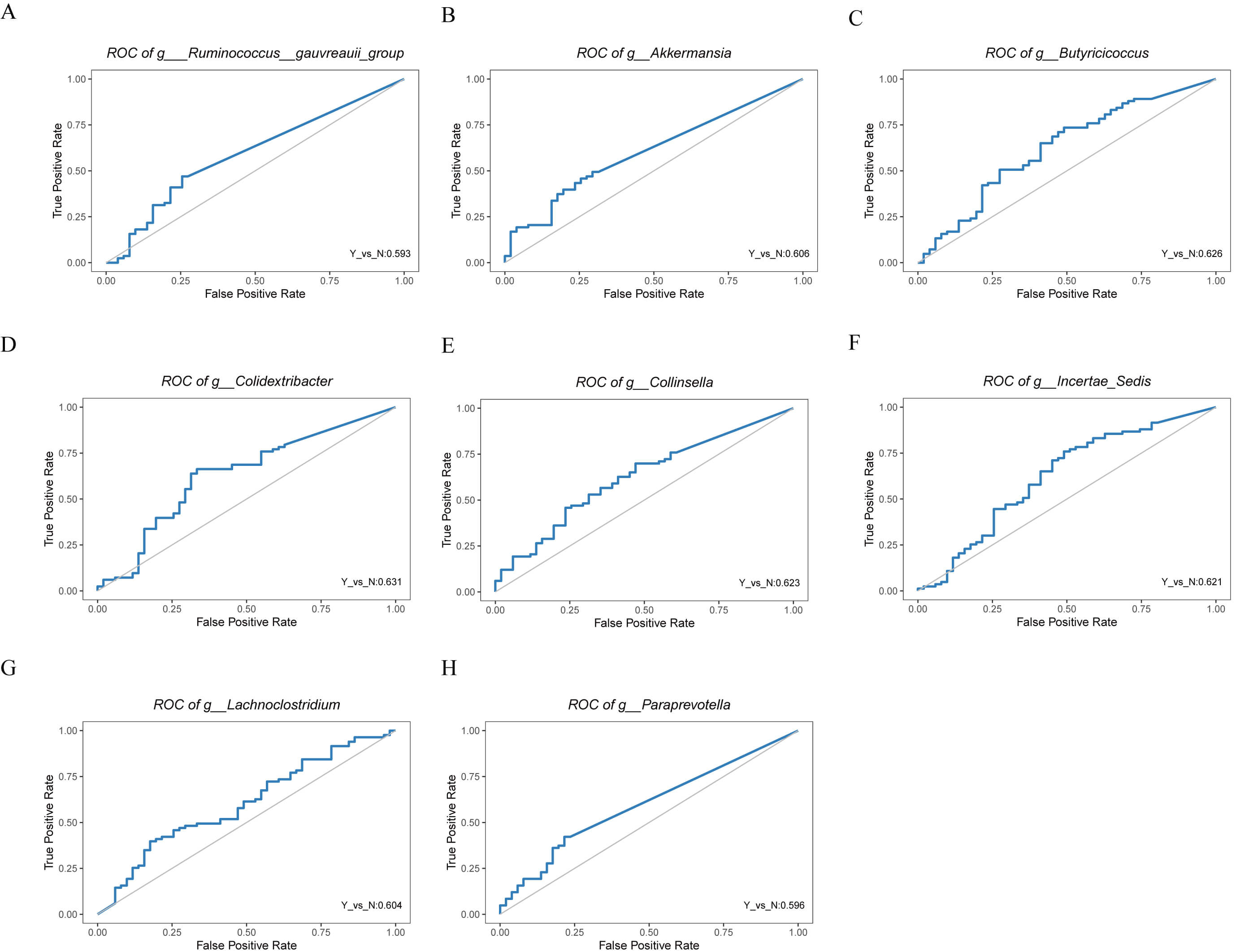

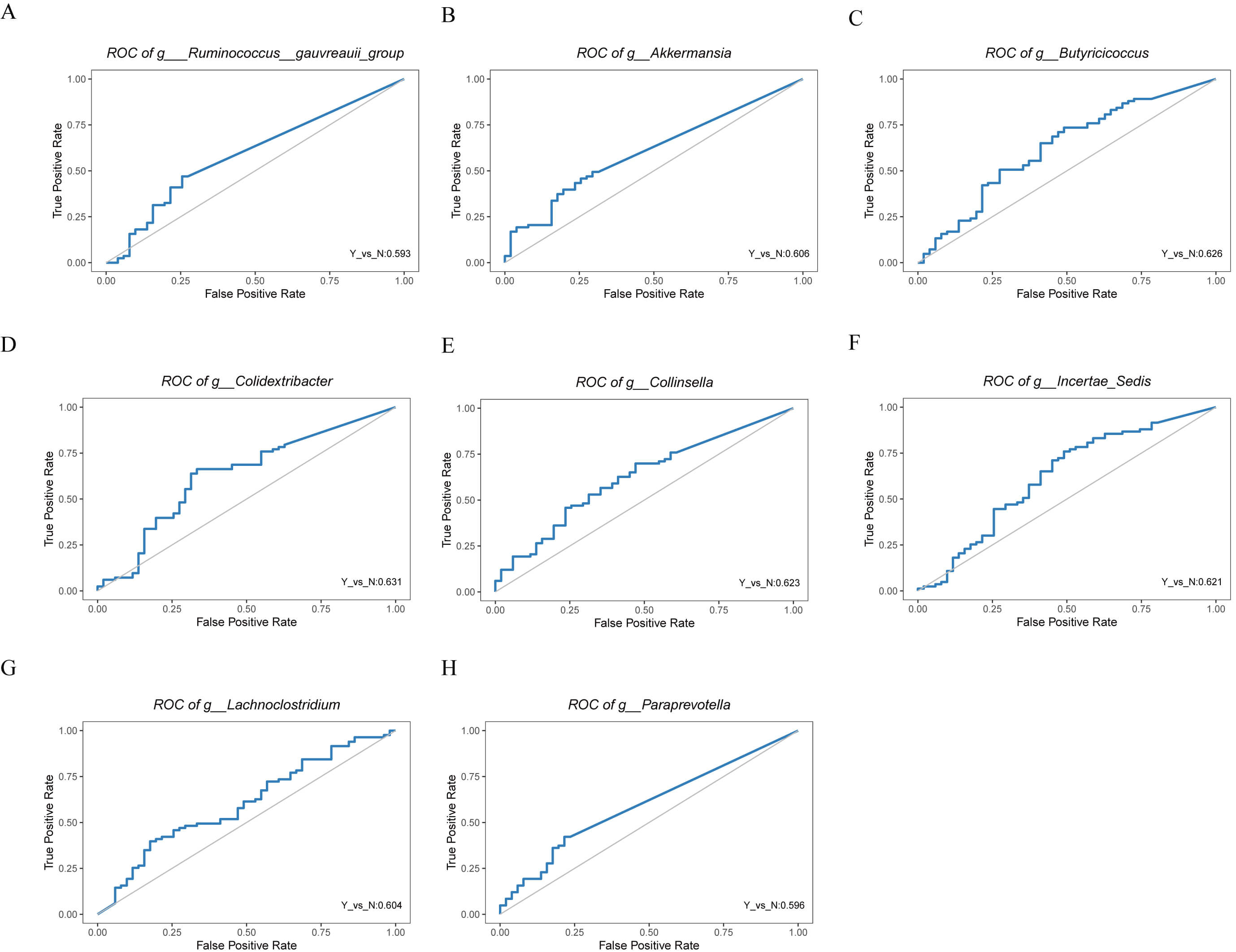

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of differential genera identified by LEfSe analysis in HF patients with or without dapagliflozin treatment. (A) ROC curve for Ruminococcus gauvreauii group. (B) ROC curve for Akkermansia. (C) ROC curve for Butyricicoccus. (D) ROC curve for Colidextribacter. (E) ROC curve for Collinsella. (F) ROC curve for Incertae Sedis. (G) ROC curve for Lachnoclostridium. (H) ROC curve for Paraprevotella.

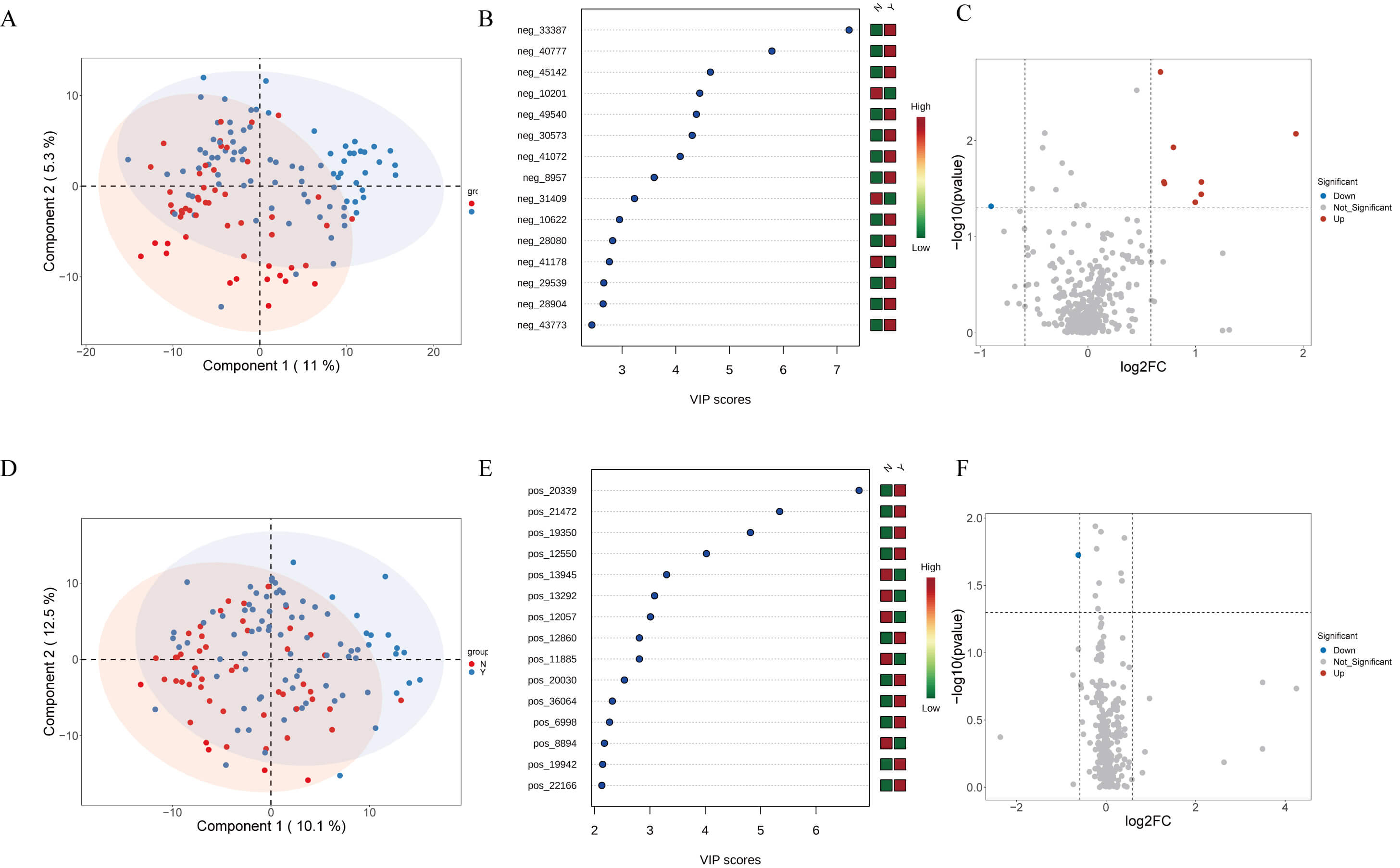

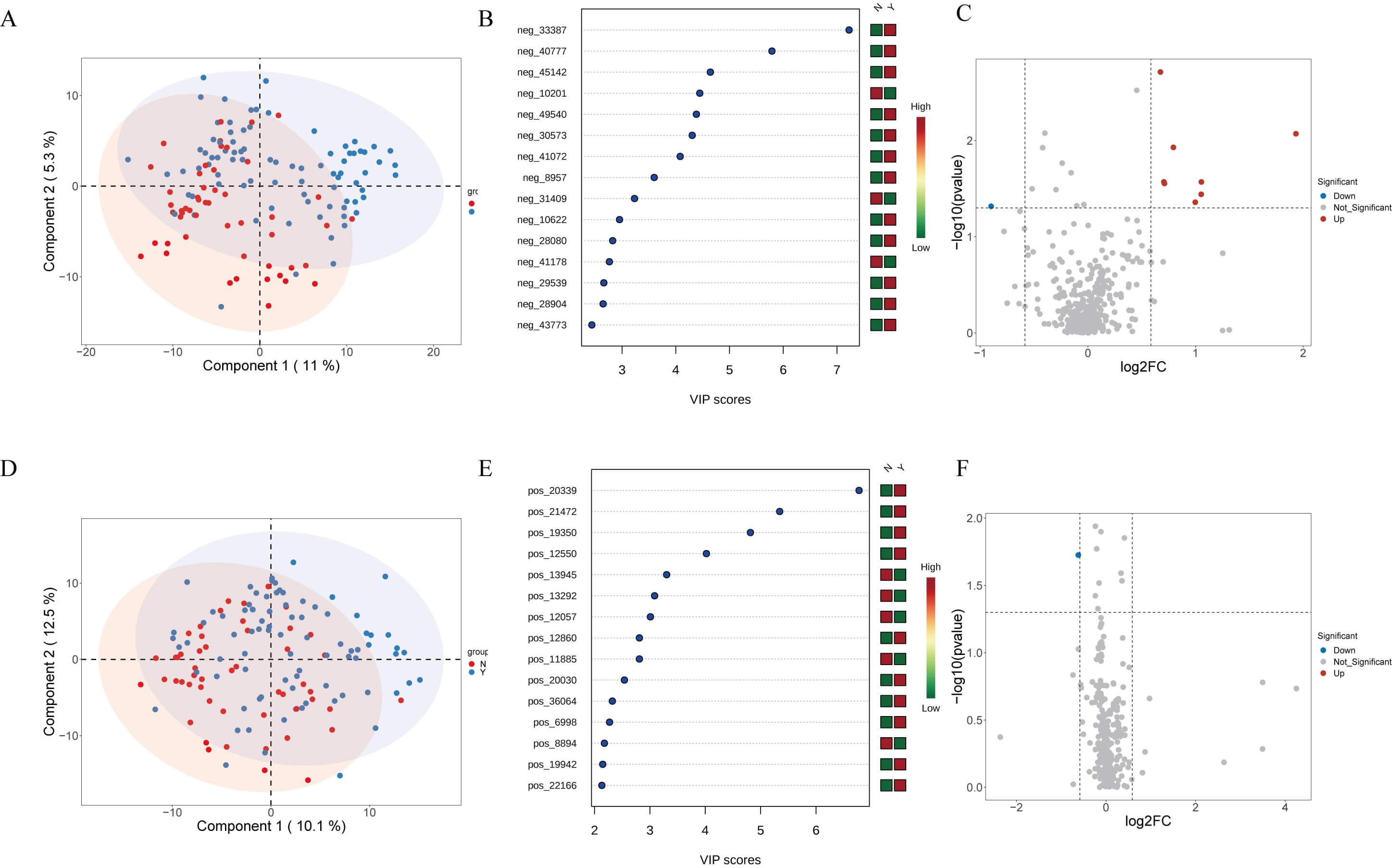

Non-targeted metabolomics distinguished Y and N groups to some extent in both

positive and negative ion modes by PCA (Fig. 4A,D). Forest plots highlighted

multiple differentially abundant metabolites (VIP

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Plasma metabolomics profiling of HF patients treated with or without dapagliflozin. (A) Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) score plot of anionic metabolites showing separation between groups. (B) Forest plot illustrating variable importance in projection (VIP) scores of key differential anionic metabolites. (C) Volcano plot displaying upregulated and downregulated anionic metabolites between groups. (D) PLS-DA score plot of cationic metabolites showing group clustering. (E) Forest plot illustrating VIP scores of differential cationic metabolites. (F) Volcano plot displaying upregulated and downregulated cationic metabolites between groups.

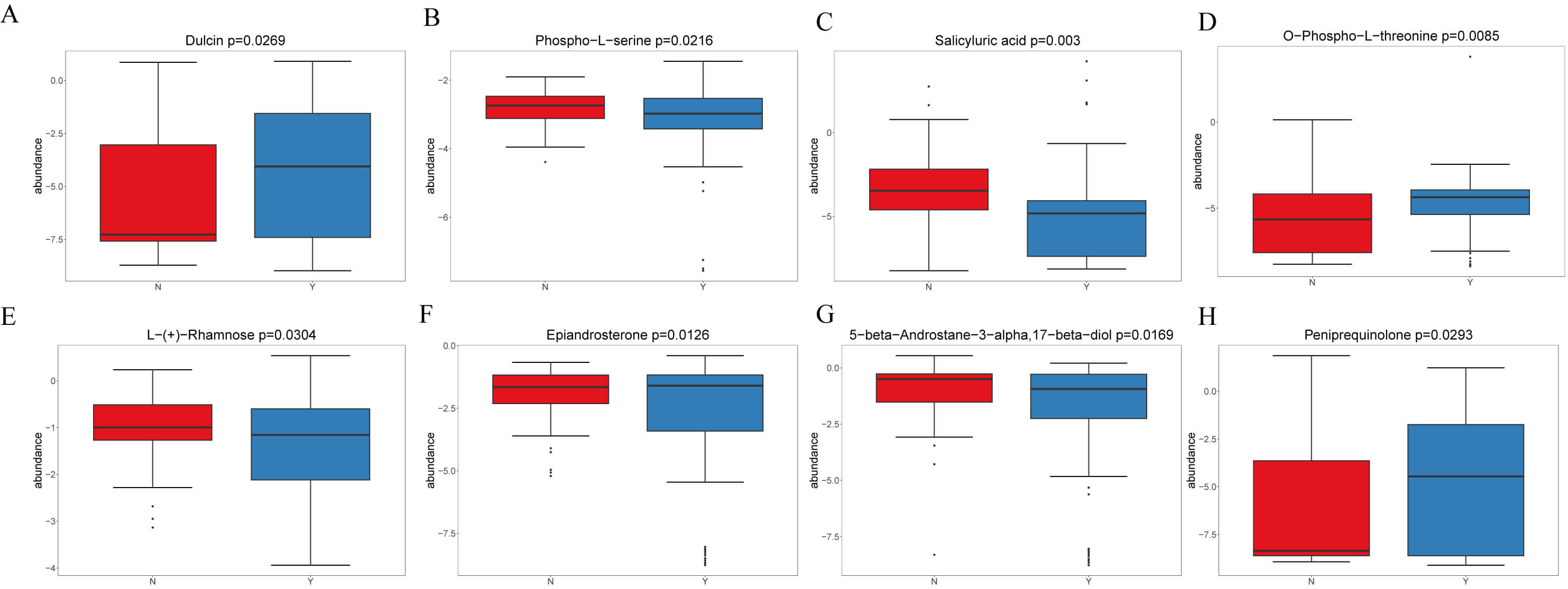

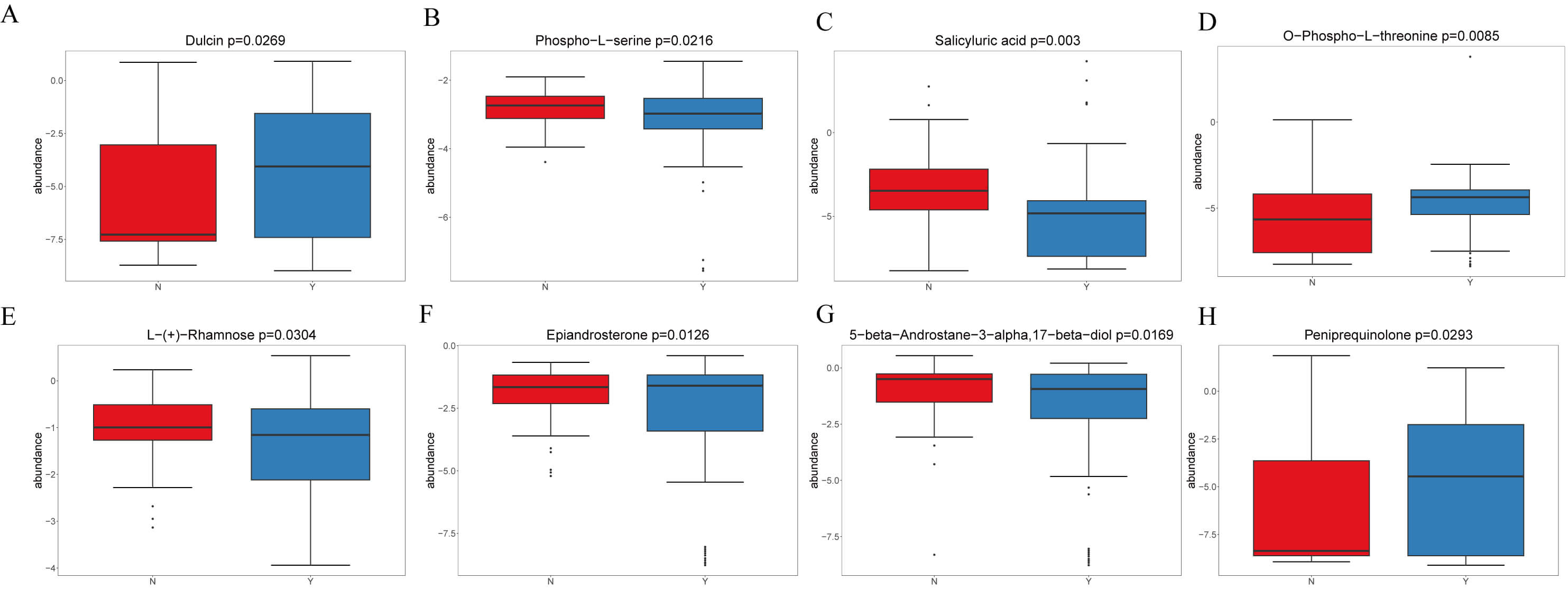

In negative mode, four representative metabolites were emphasized (Fig. 5A–D): Dulcin increased in Y (VIP = 3.60, logFC = 1.05, p = 0.027); Phospho-L-serine was enriched in N (VIP = 1.01, logFC = –0.16, p = 0.022); Salicyluric acid increased in N (VIP = 4.45, logFC = 0.45, p = 0.003); and O-Phospho-L-threonine increased in Y (VIP = 2.95, logFC = 1.93, p = 0.009).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Representative differential plasma metabolites between HF patients treated with or without dapagliflozin. (A) Dulcin levels were significantly elevated in the dapagliflozin group compared with controls. (B) Phospho-L-serine was enriched in the control group. (C) Salicyluric acid was enriched in the control group (N). (D) O-Phospho-L-threonine was markedly increased in the dapagliflozin group. (E) L- (+)-Rhamnose was elevated in the control group (N). (F) Epiandrosterone levels were higher in the dapagliflozin group. (G) 5-beta-Androstane was enriched in the control group. (H) Peniprequinotone showed increased levels in the dapagliflozin group.

In positive mode, four representatives were highlighted (Fig. 5E,F): L-(+)-Rhamnose increased in N; Epiandrosterone increased in Y; 5-beta-Androstane (Fig. 5G) was higher in N; and Peniprequinotone (Fig. 5H) increased in Y. Collectively, dapagliflozin was associated with shifts in carbohydrate, amino acid, steroid hormone, and microbiota-related metabolites, with Y showing increases in metabolites such as Salicyluric acid, O-Phospho-L-threonine, and L-Rhamnose, whereas N showed enrichment of Phospho-L-serine and 5-beta-Androstane. Figs. 4,5 illustrate these findings.

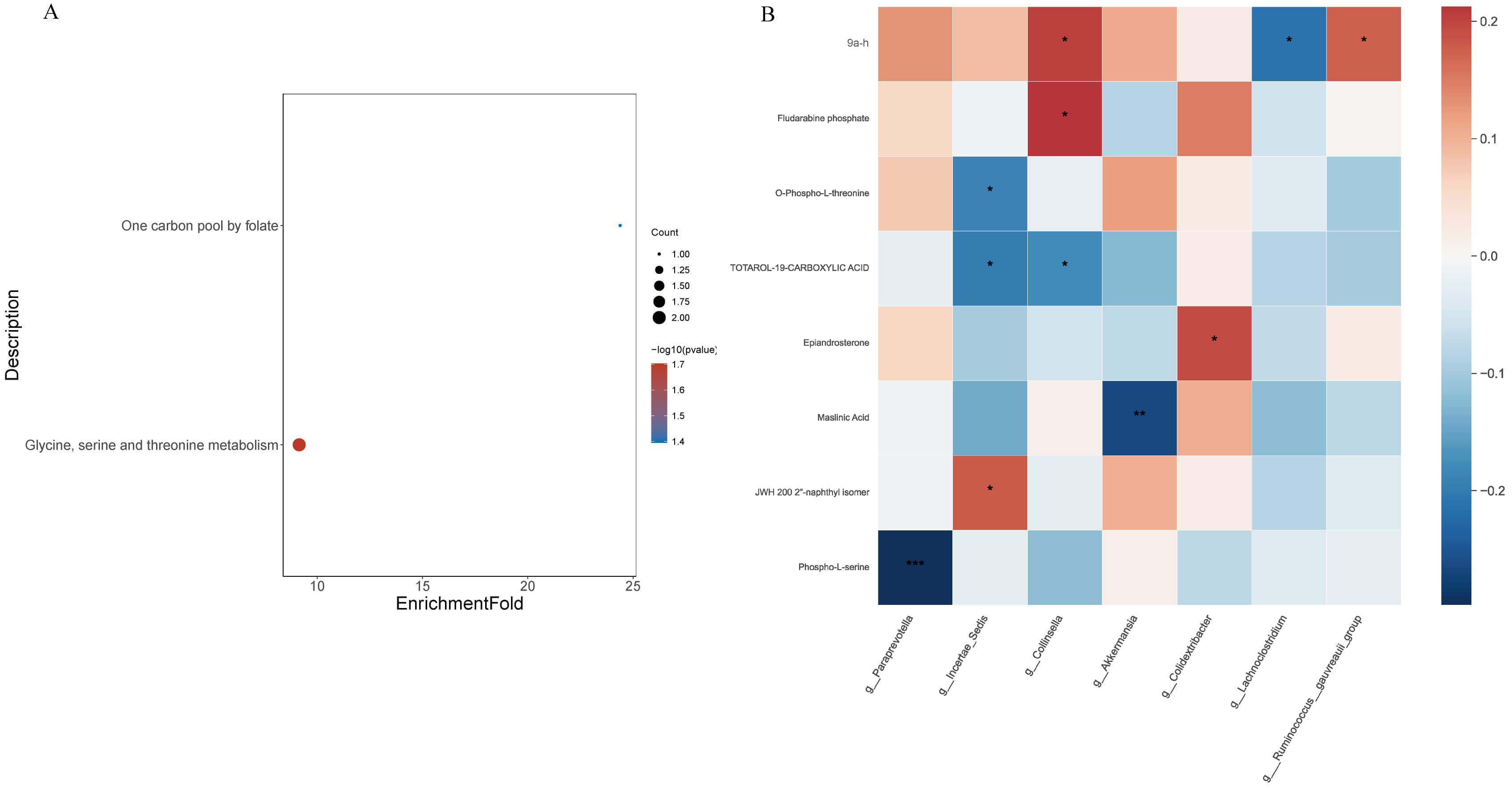

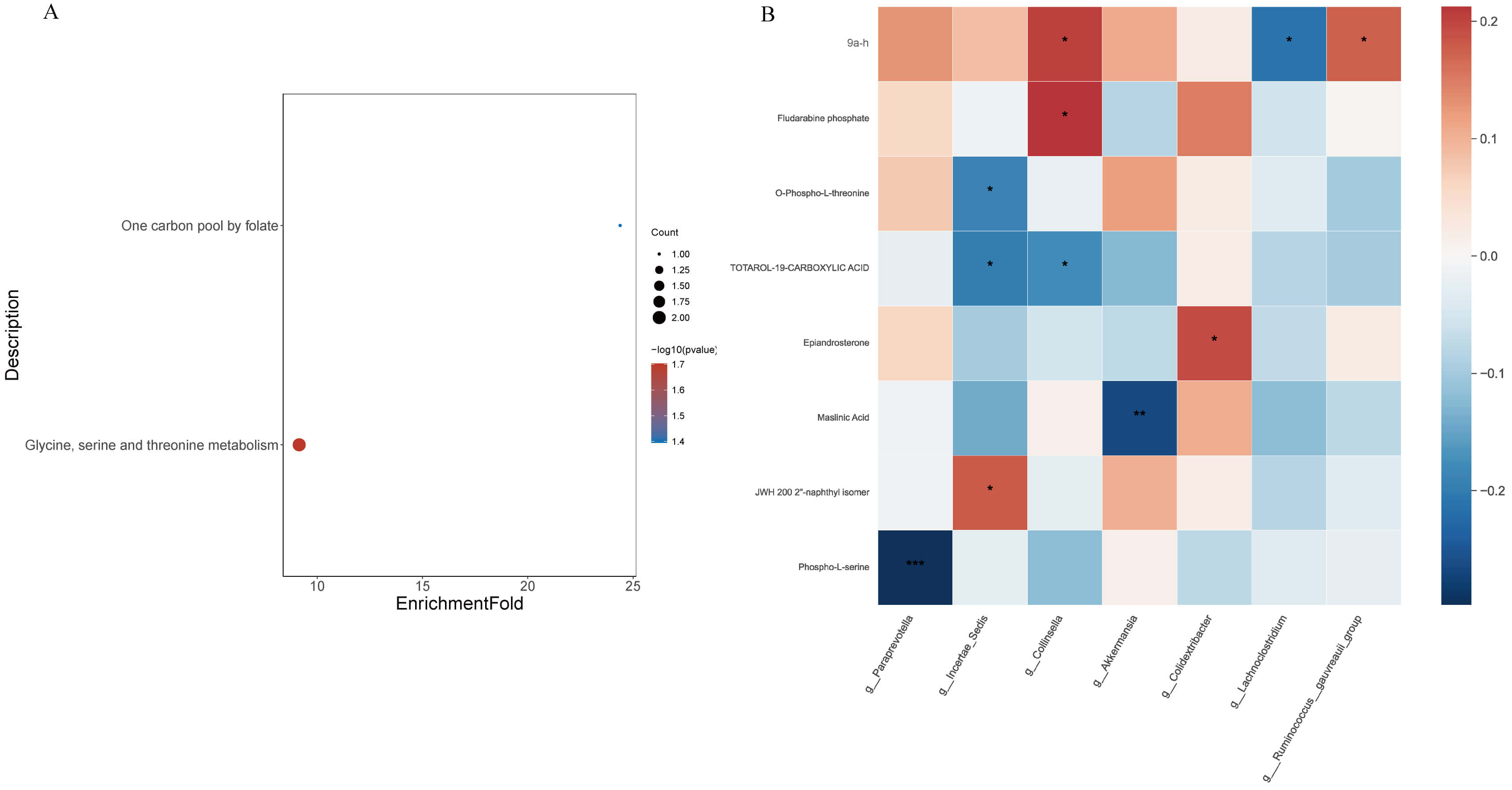

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differential metabolites (Fig. 6A) revealed two major enriched pathways: glycine, serine and threonine metabolism (ko00260; p = 0.019) and one-carbon pool by folate (ko00670; p = 0.040). Representative metabolites involved in these pathways included O-phospho-L-threonine, phospho-L-serine, and tetrahydrofolic acid, suggesting that dapagliflozin modulates amino-acid and one-carbon metabolic fluxes associated with energy homeostasis and redox balance.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Functional annotation of differential metabolites and

correlation with gut microbiota in HF patients treated with or without

dapagliflozin. (A) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway

enrichment analysis of significantly altered metabolites, highlighting amino acid

metabolism, one-carbon metabolism, and steroid degradation pathways (p

The correlation heatmap (Fig. 6B) revealed several significant associations

between gut microbial genera and plasma metabolites (

Collectively, these results indicate that dapagliflozin promotes a coordinated remodeling of gut–metabolite interactions, favoring amino-acid/one-carbon pathways and suppressing dysmetabolic signatures associated with heart-failure pathophysiology.

Based on clinical samples, this study systematically analyzed the effects of dapagliflozin on the gut microbiota composition, plasma metabolic profile, and microbiota-metabolite correlations in patients with HF. The results demonstrated that dapagliflozin not only improved patients’ clinical biochemical parameters but also remodeled the gut microbial ecosystem by promoting the enrichment of specific beneficial bacteria (e.g., Akkermansia, Butyricicoccus), which was accompanied by significant alterations in the plasma metabolite profile. These findings suggest that dapagliflozin may exert cardioprotective effects beyond glucose-lowering in HF management through the “gut-heart axis” mechanism.

Gut microbiota dysbiosis has been recognized as a significant contributing factor in HF, with mechanisms involving inflammatory activation, abnormal energy metabolism, and impaired intestinal barrier function [32]. This study found that after dapagliflozin intervention, the phylum Verrucomicrobiota was significantly enriched, particularly the probiotic Akkermansia. Previous studies have indicated that this bacterium enhances intestinal barrier integrity by degrading the mucus layer and can produce anti-inflammatory mediators, thereby mitigating systemic inflammatory responses [33]. Concurrently, the increase in butyrate-producing bacteria such as Butyricicoccus suggests that dapagliflozin may enhance the production of SCFAs, which helps maintain immune homeostasis and myocardial energy metabolism [33]. In contrast, the bacteria enriched in control group patients (e.g., Phocaeicola, Lachnoclostridium) are often associated with amino acid fermentation and a pro-inflammatory environment, indicating that dapagliflozin induces a beneficial directional modulation at the microbiota level [34].

Metabolomics results revealed a significant distinction in the plasma metabolic profiles between the dapagliflozin group and the control group, involving multiple pathways such as amino acid, nucleotide, and steroid metabolism. Notably, the anti-inflammatory metabolite salicyluric acid and the energy metabolism-related metabolite O-phospho-L-threonine were significantly elevated in the dapagliflozin group, suggesting that the drug may improve HF status by enhancing anti-inflammatory and energy metabolism pathways. Meanwhile, metabolites enriched in the control group (N-group) patients, such as phospho-L-serine and 5-beta-androstane, are closely associated with disordered amino acid metabolism and imbalanced steroid metabolism, which aligns with the clinical characteristics of energy metabolism dysfunction and hormonal abnormalities in HF patients.

KEGG enrichment analysis further revealed that dapagliflozin intervention primarily affected pathways including amino acid metabolism, one-carbon metabolism, and steroid degradation. These pathways play crucial roles in maintaining myocardial energy supply and regulating cardiac remodeling [35, 36], suggesting that dapagliflozin may improve metabolic homeostasis in HF patients through metabolic reprogramming.

Microbiota-metabolite correlation analysis indicated that Akkermansia was significantly correlated with various key metabolites, suggesting it might be a key node mediating the “gut-heart axis” effects of dapagliflozin. For instance, Akkermansia showed a negative correlation with the anti-inflammatory metabolite salicyluric acid but a positive correlation with Dulcin, a metabolite related to artificial sweeteners. This implies that this bacterium may indirectly influence the metabolic status of HF patients by regulating carbohydrate and energy metabolites. This “microbiota-metabolite-host” interaction model provides a new perspective for explaining the multifaceted protective effects of dapagliflozin.

Our data point to a convergent mechanism whereby dapagliflozin is associated with (i) selective enrichment of barrier-supporting/SCFA-linked taxa (Akkermansia, Butyricicoccus) and (ii) circulating metabolite signatures indicative of improved amino-acid/one-carbon flux and steroid catabolism. Akkermansia can fortify the mucus layer and attenuate endotoxin leakage, thereby dampening systemic inflammation and neurohormonal activation—central drivers of HF progression—while butyrate-associated pathways favor immune homeostasis and mitochondrial efficiency in peripheral tissues. The parallel rise in O-phospho-L-threonine and salicyluric acid may reflect activation of threonine–glycine–serine and folate-dependent one-carbon cycles, which support nucleotide synthesis, redox balance, and cardiomyocyte energy metabolism. In contrast, control-enriched phospho-L-serine and 5-beta-androstane are compatible with amino-acid stress and maladaptive steroid signaling, both linked to adverse remodeling. Notably, L-rhamnose and epiandrosterone increases in the dapagliflozin group further suggest shifts in microbial carbohydrate use and steroid turnover, consistent with the KEGG enrichment in carbon and steroid pathways. Taken together, these microbe–metabolite constellations provide a systems-level rationale for how SGLT2 inhibition could intersect the gut–heart axis by reducing inflammatory tone, stabilizing gut barrier function, and re-aligning myocardial substrate utilization, all of which are pertinent to HF pathogenesis. While these associations cannot establish causality, the directional coherence—beneficial taxa tracking with anti-inflammatory/energy-supportive metabolites and unfavorable taxa aligning with dysmetabolic markers—strengthens the biological plausibility of a gut-mediated component to dapagliflozin’s cardiometabolic profile. Future work integrating fluxomics, targeted SCFA/bile-acid panels, and interventional microbiome designs [e.g., diet, pre/probiotics, or Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)] could test these mechanistic links prospectively. Clinically, dapagliflozin has been proven in several large-scale randomized controlled trials to significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and rehospitalization in HF patients [37]. This study further supplements its potential microecological and metabolomic mechanisms, providing clinical evidence for a multidimensional “drug-microbiota-metabolism-host” regulatory framework. However, this study has several limitations. First, the limited sample size and single-center design may affect the generalizability of the results. Second, the cross-sectional design necessitates that causal relationships be further validated through longitudinal follow-up and animal experiments. Additionally, the dynamic changes in microbiota and metabolic pathways under long-term dapagliflozin intervention require more in-depth investigation.

Our findings are consistent with emerging evidence that SGLT2 inhibitors exert broad cardiometabolic effects beyond glucose lowering [38, 39]. For example, Albulushi et al. [40] directly compared Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with HFpEF and diabetes, demonstrating that SGLT2 inhibitors confer significant benefits on both metabolic remodeling and myocardial function. This aligns with our observation that dapagliflozin is associated with favorable shifts in gut microbiota and metabolomic profiles, suggesting that part of its cardioprotective action may involve systemic metabolic reprogramming. Incorporating such evidence strengthens the rationale that dapagliflozin could influence HF outcomes through multiple, interlinked pathways.

The concept of “precision therapy” in HF remains largely theoretical, but our findings provide preliminary clues for translation. Identification of specific microbial signatures, such as the enrichment of Akkermansia and Butyricicoccus, raises the possibility of using these taxa as non-invasive biomarkers for monitoring therapeutic response. Similarly, metabolite shifts—including elevations in salicyluric acid and O-phospho-L-threonine—may serve as surrogate indicators of anti-inflammatory or energy metabolic pathways activated by dapagliflozin. In the future, integration of microbiome and metabolomic profiling could contribute to risk stratification, early intervention strategies, and personalization of SGLT2 inhibitor therapy. Although immediate bedside application is limited, these mechanistic insights build a rationale for microbiota-targeted adjuncts (e.g., probiotics, dietary fiber supplementation) that might synergize with pharmacological treatment in HF management.

Clinically, these findings hold meaningful therapeutic implications for the management of HF. By demonstrating that dapagliflozin reshapes both the gut microbiota and the circulating metabolome, this study provides biological evidence that its cardiovascular benefits may partly derive from modulation of the gut–heart axis. Such remodeling could translate into improved myocardial energy efficiency, reduced systemic inflammation, and enhanced neurohormonal stability—pathophysiological targets that are inadequately addressed by conventional therapies.

Importantly, these microbe–metabolite signatures may serve as accessible biomarkers for patient stratification and treatment monitoring. For example, the enrichment of Akkermansia and Butyricicoccus or elevations in metabolites such as salicyluric acid and O-phospho-L-threonine may indicate a favorable biological response to dapagliflozin. Incorporating these indicators with established clinical parameters (e.g., NT-proBNP, renal function, and inflammatory indices) could enable an integrated “gut–metabolic” profiling system to guide therapy decisions.

From a precision-treatment perspective, this work suggests a feasible translational framework: (1) baseline microbiome–metabolome profiling to define each patient’s gut–metabolic phenotype; (2) SGLT2 inhibitor initiation according to guideline-directed medical therapy; (3) adjunctive interventions tailored to the microbial pattern—such as prebiotic or probiotic supplementation for SCFA deficiency or Akkermansia depletion; and (4) longitudinal assessment of microbial and metabolomic dynamics to optimize drug efficacy and minimize adverse events. In the future, combining dapagliflozin with microbiota-targeted approaches may constitute a new direction for individualized, multi-pathway modulation of HF pathophysiology.

While direct causal verification remains to be established, these findings open a clinically relevant avenue toward precision medicine, linking pharmacologic SGLT2 inhibition with microecological homeostasis and systemic metabolic remodeling. Prospective validation in multicenter, multi-omics trials will be essential to translate these mechanistic insights into therapeutic algorithms applicable to daily clinical practice.

Although our study provides novel insights into the gut–heart axis under dapagliflozin treatment, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, this was a single-center study conducted in a defined regional population. Differences in diet, lifestyle, and comorbidities across geographic and ethnic groups may influence both gut microbial composition and metabolic profiles, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings. Second, the sample size was modest, which may reduce statistical power for detecting subtle associations and increase the risk of type II errors. Therefore, while the observed microbial and metabolomic alterations are informative, they should be interpreted with caution. Future multi-center studies with larger, more diverse cohorts are needed to validate whether the patterns identified here are broadly representative of the wider heart failure population. Beyond validation, future work should also address the long-term and mechanistic dimensions of dapagliflozin’s gut–metabolic effects. Longitudinal studies incorporating serial sampling are warranted to determine whether the observed microbiome and metabolomic remodeling is sustained over months or years, and how these temporal changes correlate with cardiac function and clinical outcomes. Integrating time-resolved microbiome–metabolome data with echocardiographic and biochemical indicators could reveal predictive signatures of therapeutic response or resistance.

In parallel, translating these multi-omics insights into practice will require developing feasible, standardized panels of microbial taxa and circulating metabolites for clinical use. These signatures could support personalized risk stratification, guide adjunctive nutritional or microbiota-targeted interventions, and refine precision treatment algorithms for HF. Multi-center interventional trials combining dapagliflozin with microbiota-modulating strategies—such as pre/probiotic supplementation or dietary optimization—represent promising avenues to confirm causality and optimize therapeutic benefit.

Another limitation is that baseline differences in certain laboratory parameters—such as inflammatory markers and lipid profiles—were observed between groups. These disparities may act as potential confounders influencing gut microbiota composition and metabolomic signatures. We did not perform statistical adjustment for these variables due to the modest sample size, and therefore residual confounding cannot be excluded. Future studies with larger cohorts and stratified or multivariable analyses will be required to disentangle drug effects from baseline clinical differences. As a cross-sectional study, our analysis captures associations between dapagliflozin exposure and gut–metabolite profiles at a single time point, without establishing temporal or causal relationships. Future longitudinal and interventional studies are needed to verify these associations.

Future research could focus on the following directions: (1) Integrating metagenomics and metabolomics to delineate a comprehensive “gut-heart axis” network under dapagliflozin intervention; (2) Utilizing FMT and germ-free animal models to validate the role of key microbiota (e.g., Akkermansia) in HF; (3) Exploring combined intervention strategies, such as probiotic or dietary fiber supplementation, to determine if synergistic effects with dapagliflozin exist, thereby providing precise microecological strategies for HF treatment.

Based on integrated 16S rRNA sequencing and untargeted metabolomics, this study demonstrates that dapagliflozin significantly modulates the gut microbiota composition and plasma metabolomic profile in patients with heart failure. Dapagliflozin promoted the enrichment of beneficial genera such as Akkermansia and Butyricicoccus, while reducing potentially harmful taxa. Concurrent shifts in plasma metabolites involved key pathways including amino acid metabolism, one-carbon metabolism, and steroid degradation. Correlation analyses further revealed significant microbiota-metabolite interactions, supporting the possibility that dapagliflozin contributes to cardioprotective benefits partly via gut–heart axis modulation These findings provide novel mechanistic insights into the pleiotropic benefits of dapagliflozin beyond glucose-lowering and support the potential of microbiota-targeted strategies in the precision treatment of heart failure.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ZF and XDX conceived and designed the research. YZ and YL performed the experiments. QQL, QLZ, WJZ, CM and ZZ analyzed the results and data. YZ and YL wrote, ZF and XDX revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of The People’s Hospital of Chizhou City (approved No. 2023-KY-18). We certify that the study was performed in accordance with the 1964 declaration of HELSINKI and later amendments. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

We thank Zhao Zhang and Kangdi Zheng (Center of Human Microecology Engineering and Technology of Guangdong Province, Guangdong Longsee Biomedical Corporation, Guangzhou, China) for statistical consultation and technical support provided by the Longseek high-throughput zebrafish screening platform for drug and probiotic evaluation. Also, we acknowledge Dr. Shihao Huang from Hainan University for language polishing.

This study was supported by 2023 Chizhou City major science and technology special project and Anhui Provincial Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2022e07020058).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used Deepseek-R1 in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.